Abstract

Background

Veterans of the 1990–1991 Gulf War have experienced excess health problems, most prominently the multisymptom condition Gulf War illness (GWI). The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Cooperative Studies Program #2006 “Genomics of Gulf War Illness in Veterans” project was established to address important questions concerning pathobiological and genetic aspects of GWI. The current study evaluated patterns of chronic ill health/GWI in the VA Million Veteran Program (MVP) Gulf War veteran cohort in relation to wartime exposures and key features of deployment, 27–30 years after Gulf War service.

Methods

MVP participants who served in the 1990–1991 Gulf War completed the MVP Gulf War Era Survey in 2018–2020. Survey responses provided detailed information on veterans’ health, Gulf War exposures, and deployment time periods and locations. Analyses determined associations of three defined GWI/ill health outcomes with Gulf War deployment characteristics and exposures.

Results

The final cohort included 14,103 veterans; demographic and military characteristics of the sample were similar to the full population of U.S. 1990–1991 Gulf War veterans. Overall, a substantial number of veterans experienced chronic ill health, as indicated by three defined outcomes: 49% reported their health as fair or poor, 31% met Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria for severe GWI, and 20% had been diagnosed with GWI by a healthcare provider. Health outcomes varied consistently with veterans’ demographic and military characteristics, and with exposures during deployment. All outcomes were most prevalent among youngest veterans (< 50 years), Army and Marine Corps veterans, enlisted personnel (vs. officers), veterans located in Iraq and/or Kuwait for at least 7 days, and veterans who remained in theater from January/February 1991 through the summer of 1991. In multivariable models, GWI/ill health was most strongly associated with three exposures: chemical/biological warfare agents, taking pyridostigmine bromide pills, and use of skin pesticides.

Conclusions

Results from this large cohort indicate that GWI/chronic ill health continues to affect a large proportion of Gulf War veterans in patterns associated with 1990-1991 Gulf War deployment and exposures. Findings establish a foundation for comprehensive evaluation of genetic factors and deployment exposures in relation to GWI risk and pathobiology.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12940-024-01118-7.

Keywords: Persian Gulf War, Gulf War illness, Military exposures, Million Veteran Program

Background

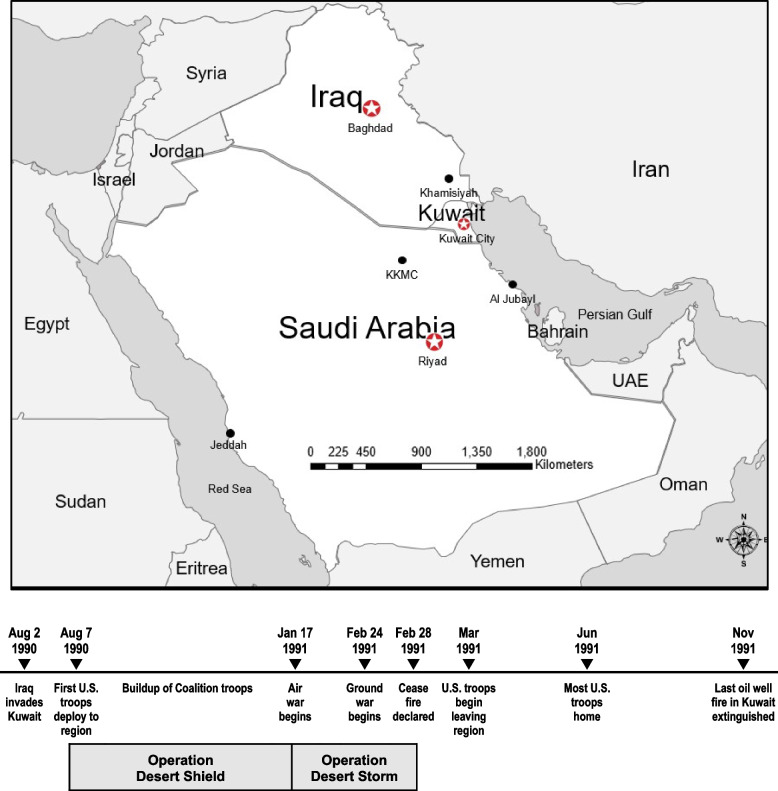

The complex health problems associated with military service in the 1990–1991 Gulf War have presented a prolonged and difficult challenge for affected veterans. On August 2, 1990, the Iraqi Army invaded the small neighboring country of Kuwait, triggering a rapid international response led by U.S military forces in partnership with 38 Coalition countries [1]. The initial U.S. military response, codenamed Operation Desert Shield, began on August 7, 1990, and involved an extended buildup of troops in the region over the next five months. The active combat period, codenamed Operation Desert Storm, began January 17, 1991, with a massive air campaign, followed by initiation of the ground assault February 24, 1991. After just four days of ground combat, a cease fire was declared in conjunction with the surrender of Iraqi forces, providing an end to active hostilities, the liberation of Kuwait, and a decisive victory for the U.S. and its Allies. The timeline and geographical areas associated with U.S. troop deployment to the Gulf War are shown in Fig. 1. Although the war was successful and relatively brief, reports soon emerged of unexplained health problems affecting U.S. and Coalition troops during deployment and in the months and years after their return from theater [2–6]. These problems included a complex of symptoms not explained by established medical or psychiatric diagnoses. This condition, now known as Gulf War illness (GWI), continues to affect a substantial number of veterans who served in the 1990–1991 Gulf War, decades after their deployment [7–10].

Fig. 1.

1990–1991 Gulf War theater of operations and timeline

Gulf War illness is characterized by a profile of multiple chronic symptoms, consistently documented across different Gulf War veteran (GWV) populations [11, 12]. The symptoms occur in multiple health domains and biological systems and typically include some combination of persistent pain, fatigue, and cognitive difficulties, often in conjunction with gastrointestinal problems, respiratory symptoms, and skin abnormalities [11–15]. Prevalence estimates for GWI vary with the case definition applied, with large GWV population studies and GWI expert panel reports generally concluding that about one third of the nearly 700,000 U.S. veterans who served in the Gulf War developed GWI [16–19].

Possible GWI causes and contributing factors have been extensively investigated in the decades since veterans returned from Gulf War deployment. In addition to the expected physical and psychological stressors of war, Gulf War military personnel encountered a variable mix of potentially hazardous chemical exposures. A number of exposures were unique to the 1990–1991 Gulf War or widely encountered by military personnel for the first time in that conflict—heavy smoke from over 600 oil well fires that burned across Kuwait throughout much of 1991 [20], depleted uranium munitions [21, 22], low-level exposure to nerve agents [23], and use of pyridostigmine bromide (PB) pills as a prophylactic measure against deadly effects of nerve agent exposure [24, 25]. Epidemiologic and clinical studies have most consistently identified a limited number of deployment exposures as the most prominent risk factors for GWI. These include (1) use of PB, taken by approximately 50% of troops [11, 19, 26], (2) extensive use of different types and combinations of pesticides and insect repellants [19, 27, 28] and, less consistently, (3) low-level exposure to nerve agents during deployment [19, 29–31].

In addition to the chronic symptoms reported by veterans, dozens of studies have characterized a range of objectively-measured biological alterations among GWVs that significantly differ between groups of GWI cases and healthy GWV controls [17, 18, 32]. The largest number of studies have identified significant changes in brain structure and function [33–37], neurocognitive decrements [38–42], and alterations in immune and inflammatory measures [43–46]. Several investigations have also identified genetic factors potentially associated with GWI [47], suggesting that some veterans may have been at greater genetic risk [48–50] for GWI and/or been more vulnerable to adverse effects of particular exposures [31, 51, 52]. But despite considerable progress in understanding key aspects of GWI, important questions and challenges remain. These include a pressing need for effective GWI treatments, a more detailed understanding of pathobiological mechanisms, including genetic factors, associated with GWI, and improved tools for GWI case ascertainment and clinical diagnosis [17, 18, 32, 53].

Multiple GWI case definitions have been proposed in the years since veterans’ health problems were initially reported [11, 12]. Although a consensus GWI case definition has not been established, two GWI case definitions were recommended for research purposes in a 2014 report from the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine [NAM]) [12]. These include the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria for chronic multisymptom illness [13], and the Kansas criteria for GWI [14]. Results of recent studies, however, have raised concerns that these widely-used GWI case definitions, both developed in the late 1990s, no longer adequately define the current profile of the GWI symptom complex [7, 8, 54]. Decades after the war, GWV studies consistently report that the number and severity of veterans’ symptoms and comorbid diagnosed conditions have continued to increase as veterans have aged [10, 55–57].

The present study was developed to characterize key features of Gulf War deployment, including exposures, in a large contemporary sample of GWVs, and to assess their association with chronic ill health. The study builds on the large cohort and rich data resources of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Million Veteran Program (MVP), a major nationwide initiative to determine genetic associations of conditions affecting U.S. veterans. MVP launched in 2011 and reached an important milestone of enrolling the first one million veterans in 2023 [58]. VA Cooperative Studies Program #2006 (CSP #2006) “Genomics of Gulf War Illness in Veterans” is a multipart project within MVP that focuses on 1990–1991 Gulf War era MVP participants. It includes both GWVs (i.e., veterans who deployed to the Gulf War theater in 1990–1991), and Gulf War era (GW-era) veterans who were in the military during that period but did not serve in the Gulf War [59].

The current study provides an assessment of the health and deployment experiences of deployed GWVs in the CSP #2006 cohort. The study’s primary objectives are to: (1) characterize patterns and variability in veteran-reported deployment profiles and exposures during the Gulf War, (2) evaluate associations of key features of Gulf War deployment and exposures with veterans’ health status, including GWI, nearly 30 years after the war, and (3) establish a foundation for additional studies to investigate interaction between genetic factors and exposures potentially associated with GWI risk and pathobiology.

Methods

Study design and sample

Participants for this large cohort study were drawn from veterans in the full MVP study cohort who had served during the 1990–1991 Gulf War era. Details of MVP subject enrollment and data collection have previously been reported [60]. The MVP CSP #2006 project utilized an additional veteran recruitment and data collection effort, as previously described [59, 61]. Briefly, the eligible CSP #2006 recruitment sample included 109,976 GWVs and GW-era veterans enrolled in MVP who were confirmed by U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) records to have served in the military between August 1,1990, and July 31,1991, and had consented to be contacted for future studies. All veterans in the recruitment sample were contacted by mail between June 2018 and March 2019. Veterans were provided project information and invited to complete the detailed “MVP 1990–1991 Gulf War Era Survey”. As previously reported, a total of 45,270 veterans completed and returned surveys, reflecting an overall response rate of 41.2% [61]. This included 45,169 surveys available for possible inclusion in the CSP #2006 analytic dataset as of August 2020. The final CSP #2006 analytic sample included a total of 40,778 veterans, after excluding surveys returned by a total of 4,391 veterans in the following groups: (1) 4,092 veterans who skipped the entire survey section that asked about symptom occurrence and severity, (2) 299 veterans for whom it could not be ascertained if they had deployed to the Persian Gulf region during the 1990–1991 Gulf War era. Nearly all excluded respondents (n = 4,283, 97.5%) were initially classified as nondeployed or undetermined for the recruitment sample, based on available data from the Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense Identity Repository (VADIR). Only 108 veterans initially classified as deployed GWVs were excluded from the final CSP #2006 sample.

The cohort of 14,103 GWVs evaluated for the current study included all veterans in the final CSP #2006 analytic sample whose survey responses indicated they had “deployed at any time to the Persian Gulf Region during the 1990–1991 Gulf War Era.” Missing or ambiguous responses to this survey question were supplemented with deployment data from VADIR, where available.

Questionnaires for the current study were returned by veterans from July 2018 through August 2020. The survey response rate among deployed GWVs (44.4%) was modestly higher than for the full CSP#2006 recruitment sample [61]. To assess the representativeness of the GWV study sample and expected generalizability of study results, demographic, military, and health characteristics of VADIR-identified deployed GWV survey respondents (n = 10,623) in the initial recruitment sample were compared to those of deployed nonrespondents (n = 13,348). These comparisons utilized demographic and military data obtained for the initial recruitment sample as well as health data for the subset of veterans (n = 14,691) who had previously completed the MVP Baseline Survey in connection with MVP enrollment. In addition, demographic and military characteristics of the final GWV study cohort were compared to the full population of U.S. 1990–1991 GWVs [62].

Data collection: Gulf war era survey questionnaire and supplemental data

The survey questionnaire asked veterans who reported they had deployed to the 1990–1991 Gulf War to provide detailed information on their Gulf War military service, including their branch of service at the time of the Gulf War as well as the month and year they first arrived in theater and when they left the region. The questionnaire included a map that delineated and labeled specific countries and regions in the Gulf War theater and asked veterans to identify areas where they had been located during deployment. Veterans were also asked to report on eight specific Gulf War experiences and exposures potentially encountered during deployment.

The questionnaire also included a range of demographic and health-related questions. This included detailed questions about veterans’ race and Hispanic ethnicity, for which they were asked to indicate all categories that applied to them. Health questions provided detailed information on veterans’ symptoms and medical history. Veterans were asked to report if they had experienced a persistent or recurring problem with 34 health symptoms included in various GWI case definitions. For each symptom reported, veterans were asked to rate the problem as mild, moderate, or severe. Additionally, veterans were asked to report if they had previously been diagnosed by a physician or other healthcare provider with a broad range of medical and mental health conditions. They were specifically asked if they had ever been told by a healthcare provider that they had GWI and if they themselves felt they had GWI. The questionnaire also asked veterans to rate their general health (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor) and included the veterans’ version of the RAND Short Form 12 (VR-12), a standardized index of general health and quality of life developed for veteran populations [63, 64].

Additional data from VADIR were used to identify veterans’ military rank during the Gulf War and to provide supplemental data to replace missing values for military branch, deployment, and demographic variables. Questionnaire and supplemental data were assembled in the analytic dataset to provide assessment of veterans’ demographic characteristics,1990–1991 military and deployment characteristics, and deployment experiences/exposures in relation to their health at the time they completed the survey in 2018–2020.

Analytic variables: Health outcomes

To provide a full perspective of GWI and potentially offset identified limitations in widely-used GWI case definitions, chronic ill health and GWI were evaluated using three distinct outcomes classified using questionnaire data: (1) The first outcome utilizes veterans’ own assessments of their general state of health, self-reported as Fair or Poor (SR-Fair/Poor) vs. Good, Very Good, or Excellent Health. (2) The second outcome designates if veterans met pre-established CDC criteria for severe GWI (CDC-GWI), coded as yes vs. no. A large majority of veterans in the cohort met the general CDC criteria for GWI [13]. The study therefore focused on the more severely ill subset of veterans who met CDC criteria for severe GWI, which recent studies have shown is more strongly associated with Gulf War service than the general CDC criteria [7, 8]. As defined by Fukuda et al., CDC criteria for severe GWI include 10 symptoms and require that veterans report one or more symptoms as severe in at least two of three defined symptom domains: fatigue domain (fatigue symptom), musculoskeletal domain (pain in muscles, pain in joints, joint stiffness), and mood-cognition domain (difficulty sleeping, difficulty concentrating or remembering, trouble finding words, feeling moody, feeling anxious, feeling depressed). (3) The third health outcome indicates if veterans reported that a doctor or other healthcare provider had ever told them they have GWI (Dx-GWI), coded as yes vs. no.

Analytic variables: Deployment characteristics

Deployment characteristics of interest included veteran-reported locations and specific time periods in theater. Veterans were asked to indicate if they had ever been located in each area identified on the questionnaire map (e.g., Iraq, Kuwait, Bahrain, Eastern Saudi Arabia, Central Saudi Arabia, Northern Saudi Arabia, Western Saudi Arabia, at sea in the Persian Gulf). Those who indicated “Yes” for a given area were then asked to estimate the duration of time they spent in that location by indicating if they had been there 1–6 days, 7–30 days, or 31 days or longer. Veterans typically reported being in multiple locations for different periods of time, for example, conducting operations for an extended period in a particular location or passing through multiple locations briefly while moving from one region to another.

For analytic purposes, three mutually exclusive subgroups were defined to evaluate deployment exposures and health outcomes in relation to veterans’ location(s) during Gulf War deployment. (1) The first defined location subgroup represented veterans who had been forward deployed, that is, veterans who reported they had been in Iraq and/or Kuwait, where nearly all battles of the war had occurred, for 7 days or longer. (2) The second location subgroup represented veterans who had served primarily at sea during deployment. This included all veterans who had not been in Iraq/Kuwait for 7 days or longer, but reported being at sea and/or serving on board ship for 7 days or longer. (3) The third location subgroup represented veterans who served primarily on land in support areas, and included all veterans who had not been in Iraq/Kuwait or served on board ship for at least 7 days.

Similarly, mutually exclusive deployment time periods were defined based on the month/year veterans reported arriving in theater and the month/year they departed the region. A key element in defining time period subgroups was whether the veteran had been present in theater during January–February 1991, the period of active hostilities, in relation to the months spent in theater before and after that period. Four mutually exclusive time period subgroups were defined and evaluated in relation to health outcomes and exposures: (1) veterans present in the region only during Operation Desert Shield (i.e., departed before January 1991); (2) veterans present during Operation Desert Storm (January–February 1991) who left the region between March 1991 and May 1991; (3) veterans present during Operation Desert Storm (January–February 1991) who left the region between June 1991 and August 1991; (4) Veterans who first arrived in the region after Operation Desert Storm (i.e., March 1991 or after).

Analytic variables: Deployment experiences and exposures

Veterans were asked to report (No/Yes/Not Sure) if, during Gulf War deployment, they had eight specific experiences (directly involved in ground combat, worked with prisoners of war) and exposures (close proximity to smoke from oil well fires, exposed to chemical or biological warfare agents, took pyridostigmine bromide pills, used pesticide cream or liquids on the skin, wore uniforms treated with pesticides, used insect baits/no-pest strips in living area). Those who indicated “Yes” to a specific item were then asked to estimate the duration of the experience/exposure. Deployment experiences/exposures were evaluated first as binary variables (i.e., “Yes” responses (any duration) to a given exposure vs. no exposure). A second exposure variable was used to evaluate exposure duration (1–6 days, 7–30 days, 31 + days) compared to veterans who reported no exposure. To provide context and a general indication of representativeness of veteran-reported exposures, the frequencies at which veterans reported individual exposures were compared with veterans’ responses to similar exposure questions in the large, population-based VA National Survey of Gulf War Veterans conducted in 1995 [65].

Missing values

If veterans did not provide a response to a given question or provided contradictory responses (e.g., marked both “Yes” and “No” to an exposure question), responses were coded as missing and not included in analyses. In specific instances where veterans reported “No” or “Not Sure” to a given location or exposure question, but also provided a duration period for that location or exposure, the initial “No” or “Not Sure” response was retained, but the duration response was not included in analyses.

Statistical analyses

Initial descriptive analyses summarized the frequencies of demographic, military, deployment, and health characteristics of all GWVs in the study cohort. Additional analyses evaluated the three primary health outcomes of interest in relation to veterans’ demographic, military, and deployment characteristics. The large sample size provided sufficient power to identify very small group differences as statistically significant. This included, in some assessments, small differences in health measures with little clinical importance and small differences in deployment characteristics with minimal relevance for determining risk. To emphasize group differences that were more meaningful and avoid pitfalls related to significance testing in large samples [66], final analytic results utilized an alpha level of 0.01 to identify associations of p < 0.01 as statistically significant. Descriptive assessments of population characteristics primarily involved categorical variables. Bivariate associations of demographic, military, and deployment characteristics with primary health outcomes (SR-Fair/Poor, CDC-GWI, Dx-GWI) were assessed by determining prevalence odds ratios (ORs) and 99% confidence intervals (C.I.) compared to a reference group within each category. Proportions of veterans who reported each queried deployment experience/exposure were compared across military and deployment subgroups using chi-square tests.

Associations of veteran-reported experiences and exposures during deployment with health outcomes were determined as follows. Initial analyses assessed bivariate (unadjusted) associations of health outcomes with each individual exposure. Multivariable logistic regression models were then used to determine the independent association of each experience/exposure with health outcomes, while controlling for demographic and military covariates and for potential confounding by other significant exposures. A backward elimination process was applied that sequentially eliminated individual variables that were least strongly associated with the health outcome (indicated by the prevalence OR) and no longer significant (evaluated at p > 0.05 to retain potentially informative covariates during model development) when assessed with other variables in the model. Deployment experiences/exposures were evaluated as categorical variables in the logistic models to allow comparison of outcomes among veterans who reported they did not have a given exposure to veterans who reported they had been exposed and also to veterans who were not sure, adjusted for covariates. Initial multivariable models evaluated all “Yes” responses to a given exposure as a single “exposed” group, compared to veterans who reported no exposure. Additional models evaluated health outcomes in relation to (1) exposure duration (1–6 days, 7–30 days, 31 + days), and (2) “Not Sure” exposure responses, compared to veterans who reported no exposure.

Final logistic models identified the association of health outcomes with each queried experience/exposure, controlling for sex, age, race, and enlisted vs. officer rank, as well as other significant deployment experiences/exposures (oil well fire smoke, involved in ground combat, took pyridostigmine bromide (PB) pills, use of skin pesticides, use of insect baits/no-pest strips). Due to validity concerns and limitations associated with the “exposure to chemical or biological warfare agents” variable (e.g., two exposures combined into a single question, > 50% “Not Sure” responses) this variable was not included as a covariate in models that evaluated independent effects of other exposures. The Cochrane Armitage trend test was used to determine if significant ordered differences occurred in the association of health outcomes with increasing duration of exposure. Interactions between effects of pesticide exposures were assessed using the Breslow-Day test for homogeneity of odds ratios [67] in bivariate analyses, and by evaluation of interaction terms in multivariable logistic models. All analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide, version 8.3 [68].

Results

The final study cohort included a total of 14,103 veterans who served in the 1990–1991 Gulf War. The majority (89%) were male although nearly 11% of participants were women, higher than the proportion of women (7%) among all U.S. Gulf War veterans (Supplemental Table 1, Additional file 1). Veterans in the cohort were also somewhat older in 1991 (lower % were < 25 years, higher % were 35–44 years) and included a higher proportion of officers, but were otherwise similar to the full population of U.S. military personnel who served in the Gulf War [62]. Evaluation of VADIR-identified GWVs in the recruitment sample (Supplemental Table 2, Additional file 2) indicated that survey respondents were generally similar to nonrespondents in relation to sex, military service branch and component, and current health characteristics (number of health conditions reported, number of hospitalizations in the prior year). However, similar to the full CSP#2006 recruitment sample [61], deployed GWV respondents were older than deployed nonrespondents (34% vs. 18% were ≥ 35 years of age in 1991) and included higher proportions of White/Caucasian veterans (67% vs. 53%) and military officers (14% vs. 5%) than non-respondents.

Table 1.

Demographic, military, and health characteristics of 1990–1991 Gulf War veterans in the MVP CSP #2006 cohort (n = 14,103)

| na | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| 45–49 | 1830 | (13.0%) |

| 50–59 | 6198 | (44.0%) |

| 60–69 | 4646 | (32.9%) |

| 70 + | 1429 | (10.1%) |

| Mean age (± SD) | 59.1 (± 7.8) | |

| Median age (range) | 58.2 (45.1–92.6) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 12,573 | (89.1%) |

| Female | 1530 | (10.9%) |

| Race | ||

| White/Caucasian | 9365 | (66.4%) |

| Black/African American | 3165 | (22.5%) |

| Asian | 268 | (1.9%) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 161 | (1.1%) |

| Other/multiple responses | 1136 | (8.1%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 1377 | (9.8%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 12,720 | (90.2%) |

| Highest education level | ||

| High school graduate or GED | 1730 | (12.3%) |

| Some college | 4240 | (30.1%) |

| Associate degree | 2318 | (16.4%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 2974 | (21.1%) |

| Master’s degree or higher | 2831 | (20.1%) |

| Military Characteristics | ||

| Military branch in 1990–1991 | ||

| Army | 7475 | (53.0%) |

| Navy | 3123 | (22.1%) |

| Air Force | 2047 | (14.5%) |

| Marine Corps | 1417 | (10.1%) |

| Coast Guard | 41 | (0.3%) |

| Rank in August 1990 | ||

| Enlisted | 11,477 | (82.2%) |

| Warrant Officer | 391 | (2.8%) |

| Officer | 2090 | (15.0%) |

| Component in August 1990 | ||

| Active | 10,704 | (75.9%) |

| Reserves | 2461 | (17.4%) |

| National Guard | 938 | (6.7%) |

| General Health Characteristics | ||

| Self-reported general health | ||

| Excellent | 525 | (3.7%) |

| Very good | 2036 | (14.5%) |

| Good | 4621 | (32.9%) |

| Fair | 5042 | (35.9%) |

| Poor | 1829 | (13.0%) |

| Health/Quality of Life VR-12 Measures | ||

| Physical Component Summary Score (PCS-12): Mean (± SD) | 36.1 (± 11.5) | |

| Mental Component Summary Score (MCS-12): Mean (± SD) | 41.8 (± 14.1) | |

| Gulf War Illness (GWI) measures | ||

| CDC-GWI: Veteran meets CDC criteria for severe GWIb | ||

| Yes | 3852 | (30.7%) |

| No | 8705 | (69.3%) |

| Dx-GWI: Veteran told by healthcare provider that he/she has GWI | ||

| Yes | 2769 | (20.2%) |

| No | 10,965 | (79.8%) |

| Veteran feels he/she has GWI | ||

| Yes | 7887 | (59.4%) |

| No | 5390 | (40.6%) |

| Year of GWI onset:c median (range) | 1993 (1990–2019) | |

Abbreviations: MVP CSP #2006 = VA Million Veteran Program Cooperative Studies Program #2006; SD Standard deviation, GED General Education Development (High School Equivalence) Certificate, VR-12 Veterans RAND 12 Item Health Survey68, CDC U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, GWI Gulf War illness

aFor some characteristics, strata do not sum to 14,103 due to missing values. Missing values for demographic characteristics: Race n = 8; Ethnicity n = 6; Education n = 10 (no missing values for Age, Sex); military characteristics: Rank n = 145 (no missing values for Military Branch, Component); health characteristics: Self-reported general health n = 50; VR-12 n = 46; CDC-GWI n = 1546; Dx-GWI n = 369; Veteran feels he/she has GWI n = 826

bDefined according to CDC criteria for severe chronic multisymptom illness in Gulf War veterans13

cYear of GWI onset reported by veterans who felt they had GWI

Table 2.

Chronic ill health in 1990–1991 Gulf War veterans: VR-12 summary measures and concurrence of outcomes

| Chronic Ill Health/Gulf War Illness Health Outcomes | VR-12 PCS (mean) | VR-12 MCS (mean) | % who report General Health as Fair/Poor | % who meet CDC Criteria for Severe GWI a | % told by healthcare provider they have GWI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veterans who self-reported their General Health as Fair or Poor (SR-Fair/Poor; n = 6871) | 29.0 | 35.3 | – | 49% | 30% |

| Veterans who met CDC Criteria for Severe GWIa (CDC-GWI; n = 3852) | 28.2 | 30.8 | 78% | – | 36% |

| Veterans who were told they have GWI by Healthcare Provider (Dx-GWI; n = 2769) | 30.6 | 34.6 | 71% | 55% | – |

| All Veterans (n = 14,103) | 36.1 | 41.8 | 49% | 31% | 20% |

Abbreviations: VR-12 Veterans RAND 12 Item Health Survey69, PCS Physical Component Summary Score, MCS Mental Component Summary Score, CDC U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, GWI Gulf War Illness

a Severe GWI defined according to CDC criteria for severe chronic multisymptom illness13

Overall, the frequency of missing data was generally low: 0–1% for demographic and military characteristics, < 3% for two of the three primary health outcomes, 5–7% for locations in theater and most individual exposures. However, two variables were missing data for more than 10% of participants: the CDC-GWI outcome was not determined for 11% of the sample, due to missing or ambiguous responses for any of the multiple survey items required to define CDC-GWI. Similarly, 16% of respondents lacked complete response data for the multiple variables required to define the time periods they were in theater.

Demographic, military, and health characteristics of the study sample are detailed in Table 1. As shown, the large majority of veterans (77%) were between 50 and 69 years of age at the time of data collection, with a mean age of 59 years. Over half the study cohort (53%) had served in the Army during the war, and 82% were in the enlisted ranks.

Overall, GWVs in the cohort reported a considerable degree of ill health (Table 1). Nearly half (49%) characterized their general health as fair or poor (SR-Fair/Poor). The mean VR-12 Physical Component Summary (PCS) score was 36.1, more than one standard deviation (10 points) below the general population mean of 50 [63, 69], indicating significantly reduced physical health status. Veterans’ mean VR-12 Mental Component Summary (MCS) score of 41.8 was also below the population mean, but to a lesser degree than the PCS. Most veterans in the cohort (88%) met the general CDC criteria for chronic multisymptom illness/GWI [13] and 31% met CDC criteria for severe GWI (CDC-GWI). Fewer veterans (20%) had been told by a healthcare provider they had GWI (Dx-GWI), although 59% of veterans in the sample felt they had GWI at the time of the survey. Among veterans who felt they had GWI, the median year of illness onset reported was 1993. Overall, 64% reported illness onset within 5 years of the Gulf War (1996 or before), and 6% reported illness onset more than 20 years after the Gulf War (2012 or later) (not shown in table).

Additional descriptive assessments determined mean VR-12 PCS and MCS scores associated with the three primary health outcomes of interest, and the extent of overlap among the three outcomes. As shown in Table 2, veterans with each of the three outcomes had similar, markedly reduced PCS scores (mean VR-12 PCS scores 28.2–30.6) that were approximately two standard deviations below the general population mean of 50. Veterans with CDC-GWI, on average, had worse MCS scores (mean VR-12 MCS = 30.8) than veterans with the other two outcomes (mean MCS = 34.6 and 35.3). The three defined health outcomes appeared to capture somewhat different groups of ill veterans. The greatest agreement occurred between SR-Fair/Poor and both GWI outcomes. Among 3,852 veterans with CDC-GWI, 78% reported their health as fair or poor. And among 2,789 veterans with Dx-GWI, 71% reported their health as fair or poor. There was less agreement between the two GWI outcomes assessed. Among veterans with CDC-GWI, only 36% had Dx-GWI. Conversely, among veterans with Dx-GWI, just 55% had CDC-GWI.

The association of chronic ill health with veterans’ demographic, military, and deployment characteristics is detailed in Table 3. Patterns of association were largely consistent across the three defined health outcomes. In contrast to most chronic conditions and health status indicators, the highest prevalence of all three outcomes occurred in the youngest veterans (< 50 years of age at the time of the study) in the cohort, with progressively lower prevalence in older age groups. For example, 38% of GWVs 45–49 years of age met severe GWI criteria, but only 19% of GWVs over age 70 met severe GWI criteria (OR = 0.39, p < 0.0001). The prevalence of illness also differed by veterans’ race. All outcomes occurred at highest frequencies among veterans who self-identified as Black/African American and “Other” or multiple races. Generally, the lowest prevalence of ill health occurred among veterans who self-identified as White/Caucasian, although a lower proportion of Asian (13%) than Caucasian (18%) veterans had been diagnosed with GWI by a healthcare provider. In addition, a higher proportion of female (36%) than male (30%) veterans had CDC-GWI (OR = 1.29, p < 0.0001), although the other two outcomes did not differ by sex.

Table 3.

Association of demographic, military, and deployment characteristics with chronic ill health in 1990–1991 Gulf War veterans

| All Veterans |

Veteran Self-Reports General Health as Fair/Poor (SR-Fair/Poor) |

Veteran Meets CDC Criteria for Severe GWIa (CDC-GWI) |

Veteran Told by Healthcare Provider that he/she has GWI (Dx-GWI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nb | Prev. | OR (99% C.I.) | Prev. | OR (99% C.I.) | Prev. | OR (99% C.I.) | |

| Demographic Characteristics | |||||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 12573 | 49 % | 1.0 (ref) | 30 % | 1.0 (ref) | 20 % | 1.0 (ref) |

| Female | 1530 | 48 % | 0.95 (0.82, 1.09) | 36 % | 1.29 (1.11, 1.51)** | 21 % | 1.05 (0.88, 1.25) |

| Age at time of study (years) | |||||||

| 45-49 | 1830 | 53 % | 1.0 (ref) | 38 % | 1.0 (ref) | 25 % | 1.0 (ref) |

| 50-59 | 6198 | 51 % | 0.91 (0.79, 1.05) | 34 % | 0.87 (0.75, 1.01) | 20 % | 0.78 (0.66, 0.92)** |

| 60-69 | 4646 | 47 % | 0.77 (0.69, 0.86)** | 26 % | 0.59 (0.50, 0.69)** | 19 % | 0.72 (0.61, 0.86)** |

| 70 + | 1429 | 41 % | 0.62 (0.51, 0.74)** | 19 % | 0.39 (0.31, 0.49)** | 17 % | 0.64 (0.51, 0.80)** |

| Race | |||||||

| White/Caucasian | 9365 | 43 % | 1.0 (ref) | 26 % | 1.0 (ref) | 18 % | 1.0 (ref) |

| Black/African American | 3165 | 61 % | 2.01 (1.81, 2.24)** | 41 % | 1.99 (1.77, 2.24)** | 26 % | 1.68 (1.48, 1.90)** |

| Native American/Alaskan Native | 161 | 55 % | 1.61 (1.07, 2.43)* | 40 % | 1.85 (1.19, 2.89)* | 21 % | 1.21 (0.73, 2.03) |

| Asian | 268 | 56 % | 1.67 (1.21, 2.30)** | 27 % | 1.03 (0.70, 1.50) | 13 % | 0.73 (0.46, 1.18) |

| Other/Multiple | 1136 | 58 % | 1.80 (1.53, 2.13)** | 39 % | 1.83 (1.54, 2.19)** | 27 % | 1.73 (1.43, 2.09)** |

| Military Characteristics | |||||||

| Military Rank in 1990-1991 | |||||||

| Officer | 2090 | 26 % | 1.0 (ref) | 15 % | 1.0 (ref) | 12 % | 1.0 (ref) |

| Warrant Officer | 391 | 41 % | 2.00 (1.49, 2.68)** | 20 % | 1.44 (0.98, 2.10) | 17 % | 1.44 (0.97, 2.12) |

| Enlisted | 11477 | 53 % | 3.32 (2.89, 3.81)** | 34 % | 2.89 (2.43, 3.44)** | 22 % | 1.97 (1.64, 2.37)** |

| Military Branch in 1990-1991 | |||||||

| Air Force | 2047 | 37 % | 1.0 (ref) | 21 % | 1.0 (ref) | 13 % | 1.0 (ref) |

| Navy | 3123 | 44 % | 1.34 (1.15, 1.55)** | 26 % | 1.28 (1.06, 1.54)* | 12 % | 0.89 (0.71, 1.12) |

| Marines | 1417 | 47 % | 1.52 (1.27, 1.82)** | 32 % | 1.78 (1.44, 2.20)** | 22 % | 1.92 (1.51, 2.43)** |

| Army | 7475 | 55 % | 2.06 (1.80, 2.35)** | 35 % | 2.02 (1.72, 2.37)** | 25 % | 2.29 (1.90, 2.75)** |

| Military Component in 1990-1991 | |||||||

| Active | 10704 | 48 % | 1.0 (ref) | 30 % | 1.0 (ref) | 19 % | 1.0 (ref) |

| Reserves/National Guard | 3399 | 51 % | 1.11 (0.99, 1.23) | 32 % | 1.05 (0.93, 1.18) | 24 % | 1.40 (1.24, 1.59)** |

| Deployment Characteristics | |||||||

| Location in Theater | |||||||

| At Sea 7 days or longer | 1993 | 41 % | 1.0 (ref) | 24 % | 1.0 (ref) | 9 % | 1.0 (ref) |

| In Iraq or Kuwait 7 days or longer | 6023 | 55 % | 1.74 (1.52, 1.99)** | 38 % | 1.97 (1.68, 2.32)** | 27 % | 3.69 (2.97, 4.58)** |

| Other land locations (not Iraq/Kuwait) | 5131 | 43 % | 1.09 (0.95, 1.25) | 24 % | 1.03 (0.87, 1.22) | 17 % | 2.06 (1.65, 2.58)** |

| Time Period in Theater | |||||||

| Left the region before Jan 1991 | 474 | 43 | 1.0 (ref) | 25 % | 1.0 (ref) | 11 % | 1.0 (ref) |

| Present Jan-Feb, left Mar-May 1991 | 7831 | 49 % | 1.27 (1.00, 1.63) | 30 % | 1.29 (0.96, 1.74) | 21 % | 2.19 (1.49, 3.22)** |

| Present Jan-Feb, left Jun-Aug 1991 | 2193 | 55 % | 1.62 (1.25, 2.11)** | 37 % | 1.74 (1.28, 2.38)** | 28 % | 3.15 (2.11, 4.69)** |

| First arrived in/after March 1991 | 947 | 46 % | 1.12 (0.84, 1.50) | 27 % | 1.12 (0.79, 1.59) | 14 % | 1.26 (0.80, 1.98) |

| All Veterans | 14103 | 49 % | 31 % | 20 % | |||

Abbreviations: GWI Gulf War Illness, Prev Prevalence, OR Prevalence Odds Ratio, 99% C.I 99% Confidence Interval, (ref) = reference group

aU.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria for severe chronic multisymptom illness13; *OR significant, p < 0.01; ** p < 0.0001

bFor some characteristics, strata do not sum to 14,103 due to missing values; Missing values for demographic characteristics: Race n = 8 (no missing values for Age, Sex); military characteristics: Rank n = 145 (no missing values for Military Branch, Component); deployment characteristics: Location in Theater n = 956; Time Period in Theater n = 2,279

Health outcomes varied significantly in relation to veterans’ military rank and branch of service during Gulf War deployment (Table 3). All outcomes affected a significantly greater proportion of veterans who served in the enlisted ranks compared to officers, and were most prevalent among Army and Marine veterans, compared to Air Force and Navy veterans. Veterans who were in the Reserve Component (includes Reserves and National Guard) during the Gulf War had similar rates of SR-Fair/Poor and CDC-GWI as Active Component veterans. However, a somewhat higher proportion of Reserve Component veterans (24%) had been told by a healthcare provider they had GWI (Dx-GWI), compared to Active Component veterans (19%, p < 0.0001).

Health outcomes also differed significantly with general features of Gulf War deployment. Among the 13,147 veterans who provided full location and duration information, just under half (n = 6,023, 46%) reported they had been in Iraq and/or Kuwait for at least seven days during deployment. The greatest burden of chronic ill health, for all defined outcomes, occurred among veterans in this group. Being in Iraq/Kuwait for at least seven days was most strongly associated with Dx-GWI (OR = 3.69, p < 0.0001). Conversely, all outcomes occurred at significantly lower rates among veterans who had served in other land locations or primarily at sea during Gulf War deployment.

The burden of ill health also varied significantly in relation to the specific time periods veterans served in theater. As shown in Table 3, all health outcomes occurred least frequently among veterans who were present only during Desert Shield (i.e., departed the region before January 1991) or first arrived in theater after the ground war had ended (March 1991 or later). Health outcomes occurred at higher frequencies among veterans who were present in theater during January and February 1991, the period of active hostilities (air and ground wars), with the highest rates among military personnel who were present in January–February 1991 and remained in theater through the summer months (June–August 1991).

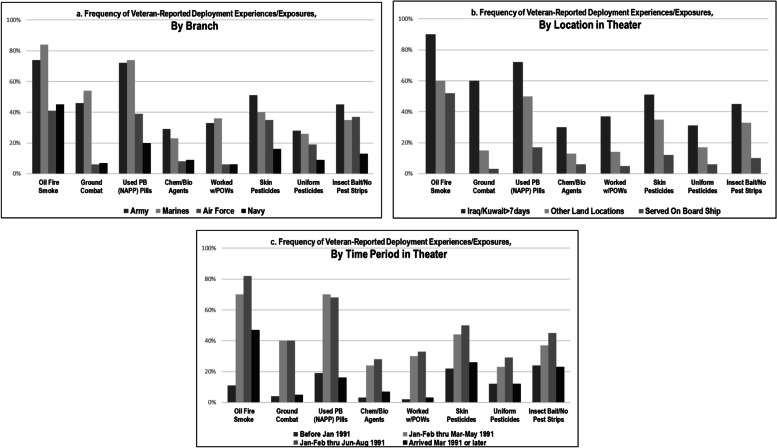

The frequency of individual deployment experiences/exposures reported by GWVs ranged from 21% who indicated they had been exposed to chemical or biological warfare agents, to 64% who reported being in close proximity to smoke from oil well fires. Overall, veterans reported Gulf War experiences and exposures in consistent patterns relative to their military and deployment characteristics (Fig. 2; details provided in Supplemental Table 3, Additional file 3). Specifically, most experiences/exposures queried were reported by substantially more Army and Marine Corps veterans than Air Force and Navy veterans. The only exceptions were that Air Force veterans reported use of two types of pesticides (skin pesticides and insect baits) at about the same frequencies as Marine Corps veterans. In addition, all experiences/exposures were reported at highest frequency by veterans who had been in Iraq and/or Kuwait for seven days or longer, intermediate frequency by veterans in other land areas, and lowest frequency by veterans who served primarily at sea during the war.

Fig. 2.

Frequency of exposures reported by 1990-1991 Gulf War veterans: variability by branch of service, location in theater, time period in theater. Note: Frequency values for all subgroups are provided in Supplemental Table 3 (Additional file 3)

Veteran-reported deployment experiences/exposures also varied in consistent patterns with the time periods they served in theater. Nearly all exposures were reported at highest frequencies by veterans who were present in theater during January–February 1991, and by significantly fewer veterans who departed the region during Operation Desert Shield (i.e., before January 1991), or first arrived during or after March 1991, after the period of active hostilities had ended. A notable exception is that veterans who arrived in March 1991 or later reported an intermediate frequency of exposure to oil well fire smoke (50%) compared to a much higher frequency reported by veterans who were present during January/February 1991 (68%-82%) and a much lower frequency (17%) reported by veterans who departed theater before January 1991.

There was considerable uncertainty about several exposures, as detailed in Supplemental Table 3 (Additional file 3). Over half of veteran respondents (54%) reported they were not sure if they had been exposed to chemical or biological agents, and over a third (34%) were not sure if they had worn pesticide-treated uniforms. In contrast, very few veterans responded “Not Sure” when asked if they had been directly involved in ground combat (3%) or worked with prisoners of war (2%).

Consistent with previous studies [11], there was significant correlation among veteran-reported exposures (Spearman correlation p < 0.0001 between all exposure pairs; Supplemental Table 4, Additional file 4). Although collinearity was not indicated, identified correlations underscored the potential for confounding effects among exposures in relation to health outcomes. The most consistent pattern of correlations occurred among the three pesticide exposures queried (using pesticides on the skin, wearing uniforms treated with pesticides, using insect baits/no-pest strips in living area), for which correlation coefficients ranged from 0.54 to 0.64.

Five of the eight Gulf War experiences/exposures queried for the current study had previously been evaluated using similar questions for the large, population-based VA National Survey of Gulf War era Veterans conducted in 1995 (see Supplemental Table 5, Additional file 5) [65]. Frequencies of exposures reported by veterans for the current study were generally consistent with those reported by veterans surveyed in 1995, although the proportion who reported exposure to chemical/biological warfare agents in the current study (21%) was about twice the proportion (10%) who reported exposure to nerve gas in 1995.

The association of health outcomes with individual exposures and exposure duration during the Gulf War are detailed in Table 4. In initial bivariate (unadjusted) analyses (not shown), each health outcome appeared to be significantly associated with all veteran-reported exposures (p < 0.0001). After adjusting for concurrent exposures and demographic and military covariates in multivariable models, six of the eight queried experiences/exposures were significantly associated with all health outcomes. For five of the six significant exposures, the magnitude of association was greatest (OR point estimates ranged from 1.35 to 5.77) in relation to Dx-GWI and lowest (OR point estimates ranged from 1.16 to 2.74) in relation to SR-Fair/Poor.

Table 4.

Association of deployment experiences and exposures with chronic ill health in 1990-1991 Gulf War veterans

|

Veteran Self-Reports General Health as Fair/Poor (SR-Fair/Poor) |

Veteran Meets CDC Criteria for Severe GWIa (CDC-GWI) |

Veteran Told by Healthcare Provider that he/she has GWI (Dx-GWI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Veterans | Exposed vs Not Exposed |

Exposed vs Not Exposed |

Exposed vs Not Exposed |

||||

| Exposureb / Duration | n | Prev. | ORadjc (99% C.I.) | Prev. | ORadjc (99% C.I.) | Prev. | ORadjc (99% C.I.) |

| Close Proximity to Smoke from Oil Well Fires | |||||||

| No | 3046 | 33% | 1.0 (ref) | 17% | 1.0 (ref) | 7% | 1.0 (ref) |

| Yes | 8599 | 54% | 1.55 (1.35, 1.77)** | 36% | 1.55 (1.31, 1.83)** | 26% | 2.14 (1.72, 2.65)** |

| 1-6 days | 1421 | 48% | 1.35 (1.11, 1.65)* | 27% | 1.19 (0.93, 1.52) | 19% | 1.52 (1.14, 2.03)* |

| 7-30 days | 2882 | 52% | 1.47 (1.24, 1.74)** | 33% | 1.32 (1.07, 1.63)* | 24% | 1.70 (1.32, 2.19)** |

| 31+ days | 3807 | 58% | 1.78 (1.52, 2.09)** | 42% | 1.97 (1.63, 2.38)** | 31% | 2.62 (2.08, 3.31)** |

| (Not sure: n=1740) | 50% | 1.49 (1.25, 1.77)* | 26% | 1.21 (0.97, 1.50) | 15% | 1.59 (1.21, 2.08)** | |

| Directly Involved in Ground Combat | |||||||

| No | 8550 | 43% | 1.0 (ref) | 24% | 1.0 (ref) | 14% | 1.0 (ref) |

| Yes | 4195 | 59% | 1.29 (1.14, 1.46)** | 42% | 1.51 (1.32, 1.72)** | 32% | 1.58 (1.37, 1.82)** |

| 1-6 days | 1878 | 56% | 1.24 (1.06, 1.45)* | 37% | 1.26 (1.06, 1.50)* | 28% | 1.32 (1.10, 1.58)** |

| 7-30 days | 1278 | 59% | 1.30 (1.09, 1.56)* | 44% | 1.62 (1.34, 1.97)** | 35% | 1.77 (1.45, 2.15)** |

| 31+ days | 812 | 66% | 1.54 (1.23, 1.93)** | 53% | 2.02 (1.60, 2.55)** | 36% | 1.71 (1.35, 2.17)** |

| (Not sure: n=402) | 62% | 1.38 (1.03, 1.85)* | 43% | 1.47 (1.07, 2.01)* | 32% | 1.72 (1.25, 2.36)** | |

| Took Pyridostigmine Bromide Pills | |||||||

| No | 3241 | 33% | 1.0 (ref) | 17% | 1.0 (ref) | 7% | 1.0 (ref) |

| Yes | 7581 | 55% | 1.41 (1.22, 1.62)** | 37% | 1.35 (1.14, 1.61)** | 28% | 2.55 (2.04, 3.19)** |

| 1-6 days | 1664 | 51% | 1.38 (1.14, 1.67)* | 31% | 1.17 (0.93, 1.47) | 24% | 2.13 (1.62, 2.80)** |

| 7-30 days | 2140 | 55% | 1.50 (1.24, 1.81)** | 37% | 1.41 (1.13, 1.76)** | 28% | 2.49 (1.91, 3.25)** |

| 31+ days | 2856 | 58% | 1.59 (1.33, 1.91)** | 42% | 1.58 (1.28, 1.94)** | 31% | 2.56 (1.98, 3.31)** |

| (Not sure: n=2624) | 49% | 1.35 (1.15, 1.58)** | 28% | 1.23 (1.01, 1.50)* | 15% | 1.73 (1.34, 2.23)** | |

| Exposed to Chemical/Biological Warfare Agents | |||||||

| No | 3400 | 30% | 1.0 (ref) | 15% | 1.0 (ref) | 5% | 1.0 (ref) |

| Yes | 2773 | 67% | 2.74 (2.30, 3.28)** | 51% | 3.29 (2.68, 4.05)** | 44% | 5.77 (4.45, 7.48)** |

| 1-6 days | 1020 | 62% | 2.37 (1.89, 2.97)** | 45% | 2.79 (2.16, 3.61)** | 37% | 4.51 (3.33, 6.09)** |

| 7-30 days | 749 | 63% | 2.50 (1.93, 3.23)** | 50% | 3.09 (2.33, 4.09)** | 47% | 6.27 (4.57, 8.62)** |

| 31+ days | 768 | 75% | 3.93 (2.98, 5.18)** | 63% | 4.94 (3.71, 6.57)** | 51% | 6.84 (4.97, 9.42)** |

| (Not sure: n=7204) | 51% | 1.66 (1.45, 1.91)** | 30% | 1.71 (1.43, 2.05)** | 19% | 2.27 (1.78, 2.90)** | |

| Used Pesticide Cream or Liquid on Your Skin | |||||||

| No | 5585 | 38% | 1.0 (ref) | 20% | 1.0 (ref) | 11% | 1.0 (ref) |

| Yes | 5376 | 58% | 1.58 (1.39, 1.80)** | 41% | 1.80 (1.55, 2.09)** | 30% | 1.77 (1.50, 2.08)** |

| 1-6 days | 388 | 55% | 1.56 (1.15, 2.10)* | 29% | 1.16 (0.82, 1.65) | 28% | 1.63 (1.14, 2.31)* |

| 7-30 days | 1237 | 55% | 1.53 (1.26, 1.85)** | 38% | 1.67 (1.35, 2.08)** | 28% | 1.64 (1.30, 2.07)** |

| 31+ days | 3272 | 61% | 1.75 (1.50, 2.03)** | 45% | 2.13 (1.80, 2.52)** | 31% | 1.76 (1.47, 2.12)** |

| (Not sure: n=2389) | 54% | 1.29 (1.11, 1.50)* | 33% | 1.43 (1.20, 1.71)* | 21% | 1.32 (1.08, 1.61)* | |

| Wore a Uniform Treated with Pesticides | |||||||

| No | 5812 | 40% | 1.0 (ref) | 22% | 1.0 (ref) | 13% | 1.0 (ref) |

| Yes | 3006 | 57% | 1.12 (0.95, 1.30) | 42% | 1.21 (1.02, 1.45)* | 30% | 1.19 (0.99, 1.44) |

| 1-6 days | 162 | 51% | 1.01 (0.64, 1.60) | 42% | 1.27 (0.77, 2.10) | 26% | 1.19 (0.71, 2.00) |

| 7-30 days | 463 | 56% | 1.18 (0.88, 1.57) | 39% | 1.21 (0.89, 1.65) | 30% | 1.29 (0.94, 1.78) |

| 31+ days | 2112 | 58% | 1.16 (0.97, 1.38) | 43% | 1.27 (1.05, 1.54)* | 31% | 1.16 (0.95, 1.43) |

| (Not sure: n=4499) | 55% | 1.11 (0.97, 1.27) | 35% | 1.14 (0.97, 1.33) | 24% | 1.10 (0.93, 1.31) | |

| Used Insect Baits/No Pest Strips in Your Living Area | |||||||

| No | 5,629 | 40% | 1.0 (ref) | 23% | 1.0 (ref) | 13% | 1.0 (ref) |

| Yes | 4,839 | 56% | 1.16 (1.02, 1.31)* | 40% | 1.26 (1.09, 1.46)** | 29% | 1.35 (1.15, 1.58)** |

| 1-6 days | 113 | 54% | 1.30 (0.76, 2.23) | 36% | 1.36 (0.76, 2.41) | 22% | 1.07 (0.56, 2.02) |

| 7-30 days | 619 | 53% | 1.02 (0.79, 1.31) | 37% | 1.10 (0.83, 1.45) | 28% | 1.23 (0.92, 1.65) |

| 31+ days | 3,647 | 57% | 1.18 (1.03, 1.36)* | 41% | 1.31 (1.12, 1.53)** | 29% | 1.34 (1.13, 1.58)** |

| (Not sure: n=2905) | 53% | 1.15 (0.99, 1.32) | 31% | 1.01 (0.86, 1.19) | 20% | 1.11 (0.93, 1.34) | |

| Worked with Prisoners of War | |||||||

| No | 9768 | 46% | 1.0 (ref) | 27% | 1.0 (ref) | 17% | 1.0 (ref) |

| Yes | 3169 | 56% | 1.02 (0.90, 1.17) | 40% | 1.11 (0.97, 1.28) | 30% | 1.15 (0.99, 1.33) |

| 1-6 days | 1361 | 57% | 1.07 (0.90, 1.28) | 39% | 1.11 (0.91, 1.34) | 28% | 1.06 (0.87, 1.29) |

| 7-30 days | 944 | 54% | 0.93 (0.76, 1.14) | 40% | 1.13 (0.90, 1.40) | 31% | 1.12 (0.90, 1.40) |

| 31+ days | 664 | 58% | 1.13 (0.89, 1.73) | 42% | 1.21 (0.94, 1.56) | 33% | 1.36 (1.05, 1.75)* |

| (Not sure: n=330) | 62% | 1.23 (0.89, 1.72) | 43% | 1.32 (0.93, 1.88) | 32% | 1.54 (1.08, 2.19)* | |

Abbreviations: GWI Gulf War illness, Prev Prevalence, OR adj Adjusted prevalence odds ratio, 99% C.I. 99% confidence interval, (ref) reference group

aGWI defined according to U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria for severe chronic multisymptom illness13

bMissing values for deployment experiences/exposures: Oil Fire Smoke n=718; Ground Combat n=956; Took PB Pills n=657; Exposed to Chem/Bio Agents n=726; Used Skin Pesticides n=753; Wore Uniform w/Pesticides n=786; Used Insect Baits/strips n=730; Worked w/POWs n=836

cLogistic regression models adjusted for other significant experiences/exposures in theater (oil fire smoke, serving in combat, taking pyridostigmine bromide pills, using pesticides on skin, using fly baits/no-pest strips in living area), military rank (Enlisted vs. Officers), sex, age, race

*Adjusted prevalence OR significant, p<0.01; **Adjusted prevalence OR significant, p<0.0001

Veteran-reported exposure to chemical/biological warfare agents was most strongly associated with all health outcomes (OR point estimates ranged from 2.74 to 5.77, all p < 0.0001) in multivariable models. The next strongest associations were identified for taking PB pills in relation to Dx-GWI (OR = 2.55, p < 0.0001) and use of skin pesticides for both CDC-GWI (OR = 1.80, p < 0.0001) and SR-Fair/Poor (OR = 1.58, p < 0.0001). Additional deployment experiences/exposures identified as significant risk factors, in descending order, included close proximity to smoke from oil well fires (ORs = 1.55–2.14), direct participation in ground combat (ORs = 1.29–1.58), and use of insect baits/no-pest strips in living areas (ORs = 1.16–1.35). For all outcomes, duration-response effects were evident for five of the six significant deployment experiences/exposures (oil well fires, ground combat, PB pills, chemical/biological agents, skin pesticides), with greater illness prevalence and higher ORs associated with longer-duration exposures (Cochran-Armitage trend test p < 0.0001 for each exposure).

Associations of “Not Sure” exposure responses with health outcomes were also assessed (Table 4). In nearly all cases, prevalence and OR estimates for health outcomes among veterans who indicated they were “Not Sure” regarding a particular exposure were intermediate between those for “Yes” (exposed) and “No” (not exposed) responses. This is consistent with expectation, assuming some veterans who reported “Not Sure” to a given exposure may have been exposed, and others were not.

Due to the clear pattern of correlation among the three queried pesticide exposures, exploratory analyses evaluated effects of individual and combinations of pesticides in relation to CDC-GWI. As detailed in Supplemental Table 6 (Additional file 6), use of skin pesticides was most strongly associated with CDC-GWI, individually and in combination with other pesticides, compared to the other two pesticide types. Neither stratified bivariate analyses nor logistic regression models identified significant interactive effects in relation to any pesticide combination. As shown, adjusted models suggested additive effects of using skin pesticides with uniform pesticides and/or insect baits, with the greatest pesticide-associated risk among veterans who reported using all three types of pesticides (OR = 2.48, p < 0.0001).

Discussion

More than three decades after the 1990–1991 Gulf War, important questions remain about the health of military veterans who served in that conflict. The current study utilized survey data collected in 2018–2020 from the nationwide cohort of GWV participants in VA’s Million Veteran Program (MVP) to evaluate measures of chronic ill health in relation to Gulf War exposures and other characteristics of deployment. The final cohort (n = 14,103) represents the largest sample of U.S. GWVs studied to date and was similar to the overall population of U.S. GWVs. Study results confirm a continuing burden of chronic ill health, including GWI, in a substantial proportion of GWVs that is associated with specific aspects of their 1990–1991 Gulf War service.

Forty-nine percent of GWVs in this large cohort reported their general health as fair or poor (SR-Fair/Poor), 31% met CDC criteria for severe GWI (CDC-GWI), and 20% had been diagnosed with GWI (Dx-GWI) by a healthcare provider. Despite differences in how the three outcomes were ascertained, these measures of chronic ill health among GWVs were associated with consistent patterns of demographic, military, and deployment characteristics. All occurred at highest frequencies among the youngest GWVs in the cohort and were less prevalent in older age groups. Several recent studies have also reported higher rates of GWI in younger veterans [8, 9, 56], although earlier GWV studies did not identify consistent age-related differences [11].

Health outcomes also occurred in consistent patterns in relation to veterans’ military and deployment characteristics. All were identified at highest rates among veterans who served in the Army and Marine Corps, and among enlisted personnel compared to officers. Similar associations of GWI with military branch and rank have been reported by previous GWV studies [11]. Veterans who served in the Reserve Component had similar rates of both SR-Fair/Poor and CDC-GWI as Active Component veterans, although more Reserve veterans (24% vs. 19%) had been diagnosed with GWI by a healthcare provider (Dx-GWI). Early reports on the health of GWVs suggested that Reserve/National Guard GWVs were disproportionately affected by Gulf War-related illnesses, compared to Active Component GWVs [62, 70]. Identified differences were based largely on the profile of veterans enrolled in VA and DOD Gulf War Registry programs, however, and were not generally supported by subsequent GWV general population studies [8, 9, 14, 71].

The current study also identified clear patterns of GWI/ill health in relation to veterans’ deployment locations and time periods of service during the 1990–1991 Gulf War. Highest illness rates were consistently identified among GWVs who served for at least 7 days in Iraq and Kuwait, where nearly all battles had taken place, and among veterans who were in theater during the period of active hostilities (January–February 1991) and remained through the summer months of 1991.

Core questions related to GWI etiology have focused on identifying specific experiences or exposures during the Gulf War that may have caused or contributed to GWI. In the current study, six of the eight individual deployment experiences and exposures queried were significantly, independently, and consistently associated with the three defined GWI/ill health outcomes. Veteran-reported exposure to chemical/biological warfare agents was associated with the highest OR estimates, followed by use of PB pills and use of skin pesticides. Overall, these findings are consistent with earlier GWV studies [11, 19] in identifying deployment exposures with potential neurotoxicant effects as the greatest risk factors for GWI.

Previous studies of GWVs have most consistently identified extended use of PB pills and pesticides as significant risk factors for GWI, after adjusting for effects of concurrent exposures [11, 19]. The 1990–1991 Gulf War is the only conflict in which PB pills were widely issued and ordered for use by U.S. military personnel in theater. Multiple government-sponsored reports have characterized the extent of PB use as well as the types and patterns of pesticide use [11, 24, 26, 72, 73]. At least 64 pesticide products are known to have been used during the Gulf War, including 15 identified by DOD as “pesticides of potential concern” [72]. Military-issued pesticides and repellants included multiple organophosphate, carbamate, and pyrethroid compounds as well as a high concentrate (75%) N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) skin product that is no longer used by the military [26, 72–74].

Some previous GWV population studies have also reported significant associations between GWI and chemical weapons exposures during deployment. Multiple chemical agent releases and possible troop exposures in the Gulf War theater have been identified [23, 75–77]. The most extensively documented and analyzed event occurred in connection with demolition operations at a large weapons depot near Khamisiyah, Iraq, in early March 1991. Department of Defense models indicate that about 100,000 U.S. troops were located in plume areas downwind from the Khamisiyah demolitions and were potentially exposed to low levels of the nerve agents sarin and cyclosarin [23]. Determining if individual GWVs were exposed to chemical weapons, however, has been a substantial challenge, with GWV studies using several approaches that have yielded differing results. When chemical weapons exposure has been estimated based on proximity to the Khamisiyah event or plume models, studies have generally identified no, or relatively low-level associations with GWI [78–81]. Moderate-level, significant associations are more typically identified by studies in relation to specific experiences evaluated as proxies for possible chemical weapons exposures, such as hearing chemical alarms or donning mission-oriented protective posture (MOPP) gear [31, 81, 82]. The largest magnitude risk estimates have been reported by studies that simply ask veterans if they were or believe they were exposed to chemical weapons during Gulf War deployment [28–30]. The elevated association of GWI/chronic illness with chemical/biological warfare agents identified by the current study (ORs ranged from 2.74–5.77, p < 0.0001) falls into the latter category. This finding should be interpreted in that context, considering the method of exposure ascertainment and identified variable limitations.

In addition to the neurotoxicant exposures consistently associated with GWI in previous studies, a limited number of studies have reported additional GWI risk factors, including exposure to oil well fires [28, 83], deployment-related vaccines [5, 83, 84], and head injuries during deployment [27, 85]. The current study did not ask veterans about all experiences and possible hazardous exposures that might have occurred during Gulf War deployment. Notably, however, the deployment locations and time periods associated with the largest number of reported exposures in this cohort were also those associated with the highest illness frequencies 27–30 years after the war.

Genetic studies may provide additional insights concerning effects of Gulf War exposures [47]. A number of candidate gene studies have previously reported gene-exposure interactions in relation to GWI risk. This includes findings that GWI risk in relation to possible nerve agent exposure was significantly elevated among GWVs with a specific genetic variant of the paraoxonase 1 enzyme (PON1192R) [31], and preliminary indications of interactions between PB use and a single nucleotide polymorphism of the PON1 gene [52] and slow-acting genetic variants of the butyrylcholinesterase enzyme [51, 86]. Although these findings require further corroboration, they suggest a potentially complex scenario involving variability of health effects resulting from one or more Gulf War exposures in relation to one or more gene variants. This underscores the importance of a careful and comprehensive evaluation of gene-exposure interactions potentially linked to GWI in a large, representative GWV population. Studies to address this core objective of the MVP CSP #2006 project are underway. Clarification of genetic factors associated with GWI can contribute essential insights concerning the etiology and pathobiology of GWI, identify subgroups of importance, and potentially support improved GWI diagnosis and clinical care.

Beyond providing an updated assessment of GWI/ill health in GWVs and associations with features of Gulf War deployment, the current study provides useful insights concerning other research issues related to the health of GWVs. In the last decade, multiple studies have raised questions about the accuracy of the two most widely used GWI case definitions, both developed in the late 1990s, for defining the current GWI symptom profile. Such concerns arise from consistent documentation of increased frequency and severity of both symptoms and diagnosed health conditions among GWVs and comparison veteran cohorts over time, and substantially reduced specificity of both the CDC and Kansas GWI criteria in relation to Gulf War service [7, 8, 54, 57].

To address and potentially compensate for limitations related to established GWI case criteria, we evaluated three indicators of chronic ill health in the MVP GWV cohort. The defined health outcomes were both general and specific in nature. That is, they were defined by veterans’ own assessments of their general level of health (SR-Fair/Poor), by the presence/absence of 10 common symptoms included in CDC criteria for severe GWI (CDC-GWI), and by veterans’ reports of being diagnosed by their healthcare providers with GWI (Dx-GWI). Despite differences in how the three outcomes were determined, identified risk factors for chronic ill health were highly consistent across all outcomes. This indicates that the identified associations are robust, despite uncertain precision in ascertaining who does/does not have GWI. It also raises the expectation that GWI risk factors, biological alterations, and genetic associations can be identified more definitively if evaluated using a current, more precise GWI case definition, refined to optimize metrics of sensitivity and specificity.

An essential aspect of population health research is to determine whether health conditions occur randomly in a given population, or if identified associations and patterns indicate a greater likelihood that the condition can be attributed to specific causes and contributing factors. A basic, but important contribution of the current study is the demonstration that GWI and indicators of chronic ill health do not occur randomly among GWVs. Study findings indicate that GWI/ill health is associated with a clear pattern of deployment characteristics and specific exposures, identifiable nearly 30 years after the war, and is not a general, nonspecific result of warzone deployment or effects of aging.

There are several important strengths of the current study. They include the size and nationwide representation of the MVP GWV cohort, providing the largest research sample of U.S. Gulf War veterans evaluated for any study to date. Although not originally developed as a population-based sample, cohort characteristics are similar to the full GWV population, providing confidence in the generalizability of research results. The timing of data collection for the current study is also an important strength, providing an essential, updated characterization of the health of GWVs 27–30 years after their Gulf War service. In addition, three indicators of GWI/chronic ill health were evaluated to offset potential limitations of particular case definitions currently in use. Another strength is our assessment of Gulf War deployment locations and time periods, which produced useful insights not typically provided by GWV studies. For veterans asked about wartime experiences many years after deployment, these characteristics of time and place were potentially less affected by differential or inaccurate recall than might be expected for particular exposures. The consistency of study findings across health outcomes regarding associations of GWI/ill health with specific risk factors and Gulf War deployment characteristics supports the validity and robust nature of our findings.

Limitations that may affect study results and interpretation relate primarily to the potential for information bias resulting from use of self-reported health and exposure data. This is less a concern for health outcomes for the current study, which primarily utilized measures identified by veterans’ symptoms and standardized health index values—both of which, by definition, rely on patient self-report. Limitations related to self-reported exposures are a greater potential concern for the study and may have led to over- or underestimates of the associations of health outcomes with risk factors. This problem is common across all GWV health studies, due to very limited documentation of exposures during the Gulf War [11, 16]. Such limitations can currently be assessed, to some extent, by evaluating the consistency of findings across studies and across populations. Further progress in identifying effects of specific exposures in individual veterans will likely depend on advances in identification of epigenetic or other biomarkers of Gulf War exposures.

A related concern, also common in GWV studies, is the proportion of veterans who were unsure whether or not they had certain exposures during the Gulf War, most prominently in relation to chemical/biological warfare agents (54%), pesticide-treated uniforms (34%), and PB pills (20%). In many cases, ‘Not Sure” was likely the most accurate response. For example, some veterans are known to have been exposed to chemical warfare agents, but usually at very low levels that did not cause symptoms. So veterans would commonly not know if they had been exposed. The large number of “Not Sure” responses resulted in a reduced number of veterans for whom effects of exposures could be directly evaluated (i.e., veterans who reported they were or were not exposed). Still, as indicated above, our analytic results were consistent with those expected in the absence of pronounced systematic bias introduced by “Not Sure” responses, for example, that could occur if veterans differentially reported “Not Sure” in relation to their health status.

Limitations associated with missing data can also be a concern for large population surveys. Although this was a relatively minor issue for the current study overall, one of the primary health outcomes of interest, CDC-GWI, was not ascertained for 11% of the sample. This reduced the sample size for evaluating prevalence and risk factors for CDC-GWI. However, the overall similarity of identified associations of deployment factors across the three primary health outcomes evaluated by the study lessens concerns about biased results due to the reduced number of veterans for whom CDC-GWI was determined.

Factors related to sample selection and survey response rates represent an additional possible limitation. In order to achieve project objectives, the study sample was drawn from a large national VA cohort assembled to address genetic questions related to veterans’ health. The survey response rate for GWVs in the current study was 44%, lower than the 50–80% response rates reported by earlier GWV population studies [14, 65, 87], but comparable to or higher than response rates achieved by later GWV studies [88, 89]. Still, the demographic and military profiles of study participants in the current cohort were generally similar to veterans in the target sample who did not participate, and to the full population of U.S. GWVs. Notable exceptions were that the study cohort included lower proportions of younger veterans and enlisted personnel compared to nonparticipants and the general GWV population. To the extent these differences introduced selection bias into study results, we would expect a possible downward bias in relation to prevalence estimates for the health outcomes reported here. However, the sampling method and response rate do not appear to have introduced substantial bias in relation to overall study results. The most prominent factors associated with GWI/ill health identified by the current study (age, enlisted ranks, Army and Marine Corps service, neurotoxicant exposures) parallel those most consistently identified by previous GWV studies.

Conclusions

The current study evaluated data collected in 2018–2020 from over 14,000 veterans of the 1990–1991 Gulf War to provide an updated assessment of veterans’ health in relation to their Gulf War service. Results indicate a continued high burden of GWI/ill health in this cohort that occurs in consistent patterns associated with veterans’ deployment characteristics and exposures, nearly 30 years after the Gulf War. Military and demographic similarities of this cohort to the full population of U.S. GWVs provide confidence that study results have a high degree of generalizability to all Gulf War veterans. Findings also demonstrate the value of the MVP GWV cohort as an important resource for future studies to address priority questions regarding the health of GWVs. This includes studies to determine the role of deployment exposures and genetic factors in GWI and biological mechanisms associated with veterans’ persistent symptoms.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1. Comparison of Demographic and Military Characteristics of Gulf War Veterans in the CSP #2006 Cohort with All U.S. Gulf War Veterans.

Additional file 2: Supplemental Table 2. Comparison of Demographic, Military, and Health Characteristics of CSP #2006 Survey Respondents vs. Non-Respondents Among Deployed Gulf War Veterans.

Additional file 3: Supplemental Table 3. Frequency of Veteran-Reported Deployment Experiences/Exposures in Gulf War Miliary and Deployment Subgroups.

Additional file 4: Supplemental Table 4. Correlation Among Veteran-Reported Experiences/Exposures During the 1990-1991 Gulf War.

Additional file 5: Supplemental Table 5. Comparison of 1990-1991 Gulf War Exposures Reported by Gulf War Veterans in the CSP #2006 Cohort and the VA 1995 National Health Survey of U.S. Gulf War Veterans.

Additional file 6:Supplemental Table 6. Association of Severe Gulf War Illness with Use of Individual and Combined Pesticides During Gulf War Deployment.

Additional file 7: Appendix A: VA Million Veteran Program: Core Acknowledgement for Publications.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the 1990-1991 Gulf War veterans who participated in the MVP Gulf War Era Survey project. We are also grateful for the assistance of Rene LaFleur and the support of the team at the West Haven VA Cooperative Studies Program Epidemiology Center, especially John Concato (former Director), Alysia Maffucci, Elani Streja, and Krishnan Radhakrishnan, as well as CSP #2006 Executive Committee Members Erin Dursa, Nancy Klimas, Kim Sullivan, and Hongyu Zhao. We acknowledge the support of MVP leadership, especially Suma Muralidhar, and the help of Nicole Usher at MVP. We also acknowledge the support of Grant Huang, Director of VA Cooperative Studies Program, and of Karen Block, Gulf War Illness Program Director, VA Office of Research and Development. Finally, we acknowledge the lasting contributions of Dawn Provenzale, former Director of the Cooperative Studies Program Epidemiology Center-Durham and former Co-Chair of CSP #2006. (Please see Appendix A (Additional file 7) for full MVP acknowledgements.)

Abbreviations

- CDC

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CDC-GWI

Meets CDC-defined criteria for severe Gulf War illness [13]

- CI

Confidence interval

- CSP #2006

VA Cooperative Studies Program #2006

- DEET

N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (insect repellant)

- DOD

U.S. Department of Defense

- Dx-GWI

Veteran was told by healthcare provider that he/she has Gulf War illness

- GWI

Gulf War illness

- GWV

Gulf War veteran

- KKMC

King Khalid Military City, in northeastern Saudi Arabia

- MOPP

Mission-oriented protective posture gear (worn as protection against potential exposure to hazardous agents)

- MVP

VA Million Veteran Program

- OR

Prevalence odds ratio

- PON-1

Paraoxonase-1, an enzyme that hydrolyzes organophosphate and other toxicants

- PB

Pyridostigmine bromide (used as prophylaxis against effects of nerve gas attack)

- SR-Fair/Poor

Self-reported general state of health reported as Fair or Poor

- U.S.

United States of America

- VA

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

- VADIR

Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense Identity Repository

- VR-12

Veterans RAND 12 Item Health Survey

- VR-12 PCS

Veterans RAND 12 Item Health Survey: Physical Component Summary score

- VR-12 MCS

Veterans RAND 12 Item Health Survey: Mental Component Summary score

Authors’ contributions

LS, ERH, KMH, RQ, STA, JK, and LMD were primary contributors to study conceptualization, design, analytic approach, and development of the original manuscript draft. Data curation: JK, RQ; formal data analysis: LS, JK, RQ; interpretation of analytic results: LS, ERH, KMH, RQ, STA, JK, LHD, DAH, MA; supervision: DAH, ERH, MA; writing (review, editing, interpretation): LS, ERH, KMH, RQ, STA, LMD, JK, DAH, MA, RP, EJG, JMG. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by VA Cooperative Studies Program #2006 and the VA Million Veteran Program (MVP Core Project 029). Drew Helmer’s salary was supported by VA Health Services Research & Development CIN 13–413. This publication does not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs or the United States Government.

Data availability

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate