Abstract

The concept of love of life, which refers to a positive attitude towards one's own life, care for it and attachment to it, has recently captured the attention of researchers in the field of positive psychology. Despite its growing importance, there is a lack of research investigating the underlying mechanisms through which love of life impacts the flourishing and well-being of individuals. For the first time, the present study examined the mediating roles of optimism and hope in the association between love of life and flourishing in Turkish youth. The study comprised 374 young adults, aged between 18 and 24 years (55.3% female; Mean age = 20.94; SD = 1.78 years), who participated in an online survey assessing their levels of love of life, optimism, hope, and flourishing. Results from the mediation analysis revealed that love of life significantly predicted optimism, hope, and flourishing. Furthermore, optimism and hope had significant predictive effects on flourishing. Importantly, optimism and hope played a partial mediating role in explaining the positive influence of the love of life on individuals' flourishing. The findings suggest a positive association between love of life and heightened levels of optimism and hope. These psychological attributes, in turn, emerge as crucial factors contributing to increased flourishing. These results hold significant implications for the development of interventions focused on understanding how to foster the love of life and flourish through the cultivation of psychological strengths.

Keywords: Love of life, Optimism, Hope, Flourishing, Turkish youth

Introduction

In the constantly evolving field of modern psychology, the rise of positive psychology is an important development that focuses on promoting well-being and flourishing. The concept of love of life, which has become more popular in recent years, is fundamental to this area of study [1]. Love of life has been largely researched in Middle Eastern countries for the last two decades [2–4]. It is currently being studied among different populations in various cultural contexts, such as Turkey, the United States, and India [5–7]. The global spread and growing interest in this concept in contemporary literature suggest that the study of the love of life is not only novel but also of significant scientific value, warranting further exploration to understand its unique contribution to the field of positive psychology. While various studies have explored the correlates, predictors, and consequences of the love of life, the underlying mechanisms driving this relationship remain unclear. This study aims to investigate the mechanisms linking love of life to flourishing by examining factors (namely optimism and hope) that can explain this association.

The love of life, a psychological concept described by Abdel-Khalek (2007), includes a wide range of emotions and attitudes towards existence. It includes a deep appreciation and enjoyable connection to life, as well as optimistic feelings about its potential outcomes. The concept of love of life is multifaceted and includes three theoretically and empirically distinct yet related domains positive attitudes towards life, meaningfulness of life, and happy consequences [1]. According to Abdel-Khalek (2007), there exists a spectrum of love of life, ranging from extreme hatred to loving of life [8]. This suggests that individuals with high scores on this spectrum acknowledge the meaning and value of life. Studies have shown that the love of life is linked to various psychological characteristics, including extroversion, finding meaning in life, optimism, social support, self-esteem, life satisfaction, religious beliefs, subjective well-being, and hope [1, 5, 6, 9–13]. On the other hand, it demonstrates negative relationships with characteristics such as psychoticism and neuroticism [14]. It is worth mentioning that there is a significant relationship between higher scores on the love of life scale and improved self-reported physical wellness and happiness, as well as reduced levels of anxiety and depression [15, 16]. However, the notion of love of life remains separate from these positive factors. According to Abdel-Khalek (2007), although the love of life is like other well-being constructions like happiness, optimism, and hope, it has a distinct relationship with these other well-being constructs, which represents a complicated interaction rather than a simple overlap [1]. This distinction provides a starting point for examining how the love of life impacts and shapes other elements of well-being, like flourishing.

Another important concept of this study is flourishing which has gained significant interest around contemporary psychology. Flourishing is closely related to well-being. The literature highlights various dimensions of well-being, encompassing subjective, psychological, social, emotional, and spiritual aspects. flourishing includes important elements within a cohesive framework [17]. This concept is typically defined as living within an optimal range of an individual's functioning which includes the fulfilment of meaningful life, effectiveness, self-worth, and intimacy, along with psychological resources like flow and engagement in daily activities [17–21]. Seligman (2011) expands on this definition, explaining flourishing as an array of positive emotions, engagement, positive relationships, meaning, and accomplishment [22]. Flourishing extends beyond mere pleasure or well-being, including a diverse array of positive psychological elements and providing a comprehensive outlook on the experience of feeling content and happy [23].

The research field of flourishing is constantly evolving, with ongoing studies exploring how it is linked to various psychological constructs. Various factors that contribute to flourishing have been examined in empirical research [24]. These factors encompass a wide range, from positive emotions like hope and optimism to individual characteristics such as personality traits [25–27]. Additionally, other factors that have been identified include resilience, life satisfaction, affect balance, the feeling of belongingness and social support, and self-compassion and mindfulness [28–30]. Contemporary studies have started to investigate the beneficial effects of love of life on well-being dimensions such as life satisfaction and subjective well-being [5, 28]. However, the relationship between love of life and flourishing, a key component of well-being, has been less examined. Dafdar et al. (2021) showed that there is a strong positive relationship between love of life and psychological well-being, which is considered one of the ingredients of flourishing, in patients admitted to the psychiatry outpatient clinic, this relationship has not been examined in the normal population. Moreover, while the study by Dafdar et al. (2021) acknowledged the strong association between flourishing and love of life, it did not investigate the potential mediators of this relationship [9]. Thus, following the suggestions of Dafdar et al. (2021), exploring the association between flourishing and love of life in the general population, while assessing the potential roles of hope and optimism as mediators, offers an important chance to enhance our understanding of these interactions.

Mediator Role of optimism and hope

Optimism could be defined as a broad belief to anticipate positive outcomes concerning upcoming circumstances. More precisely, individuals with an optimistic mindset possess a favourable perspective, maintain an expectation of the occurrence of positive events in the future, and exhibit a strong motivation to put forth effort even when confronted with challenges [31]. Optimistic people prioritize the good parts of life and believe that they can overcome difficulties and still have goals even in terrible circumstances [32]. Multiple studies have confirmed the significant association between optimism and various aspects of well-being, including subjective well-being, psychological well-being, physical well-being, meaning in life, flourish, love of life, self-esteem, hope, coping, self-efficacy, social support, mental health, and goal attainment [33–39]. Moreover, a recent study found a strong association between flourishing and optimism. These findings indicate that those with a higher level of optimism are more likely to experience flourishing [40]. Another study revealed that optimism and personality traits were strong indicators of flourishing. According to these findings, optimism would be a significant predictor of flourishing, even when considering other personality traits. This suggests that optimism plays a unique and important role in promoting flourishing, regardless of individual personality differences [24].

Hope, a significant psychological concept, is often defined as the ability to produce strategies to reach goals even when faced with challenges. It acts as a driving force for motivation and perseverance [41]. Throughout time, hope has been recognized as a key factor in determining physical wellness and overall well-being [42, 43]. The impact of this extends to different areas, such as adaptive coping skills and life satisfaction [44, 45]. In addition, past research has indicated a correlation between hope and love of life [11]. Furthermore, a positive association was observed between increased levels of hope and higher levels of flourishing, while simultaneously showing a negative relationship with fear of happiness [39, 46, 47]. In addition, research has shown that hope is linked to reduced anxiety, depression, and negative affect, while also being associated with increased subjective and psychological well-being [48–50]. Besides, recent studies suggest that hope plays a crucial role in predicting flourishing, even more so than resilience [51]. A separate study found a relationship between elevated hope levels and flourishing. This study found further evidence supporting the association between hope and flourishing with feelings as well [52]. Greater levels of hope and flourishing were found to be associated with an increase in positive feelings, while lower levels of hope and flourishing have been attributed to a growth in negative emotions. The findings align with previous studies that indicate an association between hope, flourishing, and life satisfaction [21, 41, 53, 54].

This extensive examination of literature indicates that hope and optimism are closely linked to both a love of life and flourishing among youths. Their potential as mediators may stem from the positive emotions associated with achieving goals, which are present in all of these constructs. The importance of achieving goals, especially during the later stages of adolescence, is highlighted by Erikson's theory of developmental tasks [55]. In his study, Erikson (1968) suggested that the successful completion of these tasks can bring about a sense of fulfilment and meaning in the lives of young individuals. Conversely, failure to do so may lead to feelings of frustration and potential challenges in their social interactions [56]. Within this framework, the presence of optimism and hope which also have an important motivational value can greatly enhance the satisfaction of life that comes with reaching one's goals, particularly during the developmental phase of university students. This indicates their potential as mediators in the relation between the love of life and flourishing, a reason for deeper examination in the present research.

Present study

Despite its growing importance, there is a lack of research investigating the underlying mechanisms through which love of life impacts the flourishing of individuals. For the first time, the present study examined the mediating roles of optimism and hope in the association between love of life and flourishing in Turkish youth. This study provides a significant contribution to the field by addressing a critical gap in the literature. Firstly, understanding the mediating roles of optimism and hope would present deeper insights into the psychological processes that link love of life to flourishing. This could help researchers and practitioners develop more targeted interventions to enhance well-being among youth. Secondly, focusing on Turkish youth adds a cultural dimension to the existing body of knowledge. It might allow for the investigation of how the love of life is linked to flourishing within the cultural context of Türkiye through positive psychological constructs (i.e., optimism and hope), thereby enriching the global understanding of these relationships. Based on the research aim, three central hypotheses were formulated to guide the study:

-

(i)

Love of life will exhibit positive associations with optimism, hope, and flourishing. This hypothesis is related to the notion that a strong affection for life may contribute to a positive outlook, increased hopefulness, and greater flourishing in life.

-

(ii)

Optimism and hope will demonstrate positive associations with flourishing. This hypothesis is grounded in the belief that individuals with optimistic perspectives and high levels of hope are more likely to experience a higher degree of flourishing in various life domains.

-

(iii)

Optimism and hope will act as mediators in the relationship between love of life and flourishing. This hypothesis is derived from the idea that the positive effects of love of life on flourishing may be partially explained by the roles of optimism and hope.

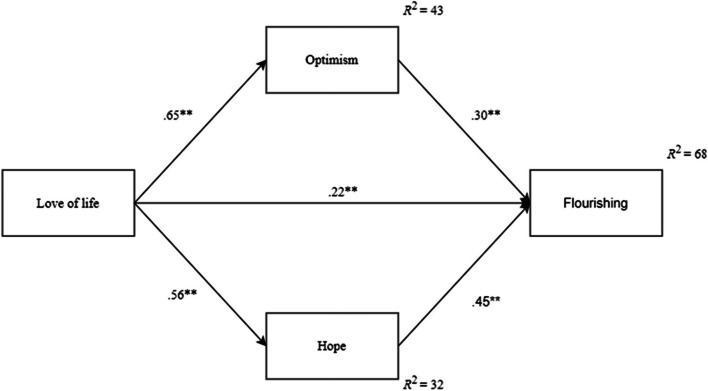

The conceptual framework illustrating these hypotheses is presented in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

The proposed structural model

Methods

Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study between December 2023 and February 2024. The study population consisted of university students who enrolled in higher education institutions across Ankara, the capital of Turkey, where students typically performed above the national average in university entrance exams. Inclusion criteria for the study are as follows: undergraduate students who enrolled in a university, aged between 18 and 24 years, and who have voluntarily agreed to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria include individuals who do not meet the inclusion criteria and those who, after being informed about the study's purpose, decline to participate. Recognizing that results derived from a small sample size may not be generalizable, Green's (1991) criteria for determining the number of participants have been applied. These criteria recommend the use of at least 200 participants for any regression-based analysis, irrespective of the number of predictor variables in the model. The study included 374 undergraduate students (44.7% male; 55.3% female) with ages ranging from 18 to 24 years (M = 20.94; SD = 1.78). Participants' perceived socio-economic status (SES) was distributed as follows: medium SES (68.2%), low SES (15.0%), high SES (12.3%), very low SES (3.7%), and very high SES (0.8%).

Measures

The Love of Life Scale was used to assess individuals' overall positive attitude toward and enjoyment of life. Comprising three factors—a positive attitude toward life (8 items), happy consequences of love of life (4 items), and meaningfulness of life (4 items)—the scale uses a 5-point Likert-type response format ranging from 1 (no) to 5 (very much) [1, 8]. An example item is “Life is full of pleasure.” Yıldırım and Özaslan (2022) conducted the Turkish validation of the LLS, supporting its one-factor structure [5]. Higher scores on the scale indicate a positive attitude, happiness, and meaningfulness in life. In our study, the Cronbach's alpha for the LLS was 0.94.

The Life Orientation Test was used to assess individuals' dispositional optimism. The LOT consists of 10 items, including 4 positively-worded items, 4 negatively-worded items, and 2 filler items. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. A higher score on the scale indicates a greater level of optimism [57]. An example item is “I'm always optimistic about my future.” Aydin and Tezer (1991) adapted to Turkish [58]. In this study, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the scale is .74.

The Dispositional Hope Scale is a self-reported measurement tool developed to assess one’s level of dispositional hope. The DHS consists of 12 items and two dimensions, namely agency and pathways. Each dimension includes four items, and the remaining four items are filler items. The items are rated on an eight-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (definitely false) to 8 (definitely true). A sample item is “I meet the goals that I set for myself.” Higher scores indicate greater hope. In this study, the total scores of two dimensions were calculated [59]. The Turkish version of DHS was found to be reliable and valid [60]. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha of DHS was .88 for overall hope.

The Flourishing Scale was used to measure the flourishing levels of participants. The FS includes 8 items rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A sample item includes “I lead a purposeful and meaningful life.” Higher scores on the scale signify a higher level of flourishing across critical areas of human functioning [17]. The Turkish adaptation of the scale demonstrated adequate psychometric properties [61]. In this study, the reliability statistic for the scale was α = .89.

Procedure

We encouraged participants to complete an online survey using Google Forms, which we distributed over social networking sites like WhatsApp. The study employed an online snowball method for recruiting volunteers. We granted each participant their informed permission (online) to participate in this research after providing information about the objectives and methodologies of the current study. We informed participants of their rights throughout their involvement, and their participation was entirely voluntary. We securely managed and kept all participant information anonymous to ensure confidentiality. Our study adhered to ethical standards, which are in accordance with the principles of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments.

Data analysis

Skewness and kurtosis statistics were reported to assess the distribution of the variables, adhering to the conventional criteria of skewness and kurtosis < |1|, which indicates a "very good" normal distribution [62]. There are no issues regarding multicollinearity among the variables. The relationships between the variables were examined using Pearson correlation in this study. To investigate the proposed hypothetical mediation model, we applied the PROCESS macro with model 4. The results from the mediation analysis were reported using various statistics such as standardized and unstandardized regression coefficients and squared multiple correlations. Furthermore, a bootstrapping technique with 5,000 bootstrap samples was conducted to calculate the indirect effect, accompanied by 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were carried out using SPSS version 26 for Windows.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

The findings, including descriptive statistics, normality test results, internal reliability estimates, and bivariate correlations for the analyzed variables, are presented in Table 1. Skewness values (ranging from -0.66 to -0.24) and kurtosis values (ranging from -0.43 to 0.47) fell within the “very good” range for a normal distribution. The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients revealed that love of life had significant positive correlations with optimism, hope, and flourishing. Optimism exhibited significant positive correlations with hope and flourishing. Additionally, a significant positive relationship was observed between hope and flourishing.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations

| Variable | Mean | SD | Skew | Kurt | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Love of life | 50.01 | 12.96 | -0.28 | -0.43 | .94 | — | .65** | .56** | .66** |

| 2. Optimism | 31.52 | 6.54 | -0.23 | -0.24 | .74 | — | .60** | .71** | |

| 3. Hope | 45.91 | 10.35 | -0.65 | 0.42 | .88 | — | .75** | ||

| 4. Flourishing | 38.56 | 10.18 | -0.55 | -0.21 | .89 | — |

**p < 0.01

The mediation analysis

The mediation analysis results are reported in Tables 2 and 3, and illustrated in Fig. 1. Love of life exhibited a significant positive predictive impact on both optimism (β = 0.65, p < 0.001) and hope (β = 0.56, p < 0.001). Love of life accounted for 42% of the variance in optimism and 31% in hope. Furthermore, love of life (β = 0.22, p < 0.001), optimism (β = 0.30, p < 0.001), and hope (β = 0.45, p < 0.001) revelated significant predictive effects on flourishing. Taken together, these variables explained 69% of the variance in flourishing. Importantly, the indirect effect of love of life on flourishing was statistically significant through both optimism (effect = 0.15, 95% CI [0.10, 0.21]) and hope (effect = 0.20, 95% CI [0.15, 0.24]). These findings suggest that optimism and hope played a partial mediating role in the relationship between love of life and flourishing.

Table 2.

Unstandardized coefficients for the mediation model

| Consequent | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 (Optimism) | |||||

| Antecedent | Coeff | SE | t | p | |

| X (Love of life) | a1 | .33 | .02 | 16.55 | < .001 |

| Constant | iM1 | 15.09 | 1.03 | 14.71 | < .001 |

|

R2 = .42 F = 273.75; p < .001 |

|||||

| M2 (Hope) | |||||

| X (Love of life) | a2 | .45 | .03 | 12.95 | < .001 |

| Constant | iM2 | 23.63 | 1.78 | 13.30 | < .001 |

|

R2 = .31 F = 167.78; p < .001 |

|||||

| Y (Flourishing) | |||||

| X (Love of life) | c' | .17 | .03 | 5.52 | < .001 |

| M1 (Optimism) | b1 | .45 | .06 | 7.18 | < .001 |

| M2 (Hope) | b2 | .44 | .04 | 11.90 | < .001 |

| Constant | by | -4.48 | 1.56 | -3.06 | < .001 |

|

R2 = .69 F = 273.60; p < .001 |

|||||

SE Standard error, Coeff Unstandardized coefficient, X Independent variable, M Mediator variable, Y Dependent variable

Table 3.

Standardized indirect effects

| Path | Effect | SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | .35 | .03 | .29 | .41 |

| Love of life– > Optimism– > Flourishing | .15 | .03 | .10 | .21 |

| Love of life– > Hope– > Flourishing | .20 | .02 | .15 | .24 |

Number of bootstrap samples for percentile bootstrap confidence intervals: 10,000

Discussion

The present study explored the cross-sectional associations between the love of life, optimism, hope, and flourishing in a Turkish youth sample. Although the associations between optimism, hope, and flourishing are well-documented, there exists a research gap regarding the underlying mechanisms through which love of life influences flourishing. To address this gap, our study used the PROCESS macro to simultaneously investigate the potential mediating roles of optimism and hope [63]. The analysis results typically supported all hypotheses outlined in this study, and these findings are thoroughly discussed below.

The first hypothesis of this study centres on the role of love of life in contributing to optimism, hope, and flourishing among Turkish youth. Similar to our findings, various studies involving both clinical and non-clinical samples have identified a positive relationship between love of life and attributes such as optimism, hope, life satisfaction, and well-being [2, 3, 5, 9]. The concept of love of life, essentially an affective evaluation of one's existence, emerges as a fundamental factor in cultivating optimistic and hopeful perspectives [1]. Importantly, our analysis revealed that love of life had significantly predicted the variance in the levels of optimism and hope, suggesting that an appreciation and deep affection for life may be crucial in enhancing these positive psychological constructs. The strong association we observed between love of life and flourishing not only underscores the value of fostering a positive outlook on life for improving flourishing and psychological functioning but also highlights its specific relevance in youth development [64]. Within youths, cultivating a love of life could act as a protective factor against mental health problems [7]. The significant association between the love of life and positive psychological constructs like optimism, hope, and flourishing reinforces the findings of prior research that emphasizes the importance of positive life orientation in the promotion of well-being and flourishing [3, 5, 9, 65]. However, it is imperative to note that while our study indicated a significant association between the variables, it does not establish causation. Other contributory factors to optimism, hope, and flourishing may exist beyond the love of life [66]. This finding underscores the need for longitudinal studies to further investigate the causal relationships between these constructs. Such future research could provide evidence about how fostering the love of life in youth can enhance their levels of optimism, hope, and flourishing, thereby contributing to more effective strategies in positive psychology and youth development.

In this study, supporting our second hypothesis, we identified statistically significant impacts of hope and optimism on flourishing among Turkish youth. This finding highlights the beneficial roles of hope and optimism in nurturing flourishing, which includes positive relationships, feelings of competence, and a sense of purpose in life, which is consistent with previous studies [17, 18, 67, 68]. A plausible explanation for this relationship is that hope and optimism act as promotive factors, enhancing flourishing and well-being even in challenging conditions, especially in youths. Indeed, individuals who possess a higher level of hope tend to employ more effective coping mechanisms when faced with challenging life situations [46]. Furthermore, the positive association between hope and flourishing is reported by evidence indicating that higher levels of hope are often accompanied by increased positive emotions, which are integral to a sense of flourishing [52]. Hope is the driving force behind individuals' motivation to set and pursue goals, enabling them to devise effective plans for success. Particularly in youth, having a clear purpose, strong motivation, and effective plans may contribute to cultivating more widespread positive expectations about the future which in turn can greatly enhance flourishing [22, 69]. The relation between optimism and flourishing can be explained by the concept of optimism. Optimism includes keeping positive expectations in life, which subsequently fosters individuals to engage in acting even when faced with difficult circumstances [32]. Research indicated that individuals with higher levels of dispositional hope and optimism exhibit greater resilience and are better equipped to cope with stressful situations, thereby promoting well-being and psychological health [67]. However, it is crucial to recognize that these findings may be influenced by external variables such as socioeconomic status and educational opportunities [46, 70]. Consequently, the emerging relationship between hope, optimism, and flourishing in Turkish youth can be interpreted as a reflection of these constructs' roles in fostering resilience and enhancing positive psychological health. This interpretation is in line with the broader literature on positive psychology, which highlights the significance of hope and optimism in the promotion of flourishing and well-being [18, 24, 39, 47, 52]. Thus, our findings strengthen the imperative of integrating these positive psychological constructs into interventions and educational programs aimed at youth development.

Our final hypothesis asserts the mediating roles of optimism and hope in the relationship between love of life and flourishing among young adults. Our findings revealed that while the love of life has a direct influence on flourishing, this effect is partially transmitted to flourishing through heightened levels of optimism and hope. As in this study, all three variables were shown to predict flourish in previous studies [2, 24, 47, 51], but the role of optimism and hope in the effect of love of life on flourish was investigated for the first time in this study. This finding suggests that the associations among these constructs do not only operate directly from one variable to another but interact dynamically to enhance flourishing. Namely, individuals who scored high on love of love had higher optimism and hope resulting in higher levels of flourishing and vice versa. Furthermore, the study posits that love of life may act as a factor through hope and optimism towards flourishing, particularly in younger populations who are at a formative stage in developing worldviews and life attitudes [68]. This notion is supported by the finding that while the love of life is a critical ingredient of flourishing, its impact is partly mediated by other positive psychological constructs like optimism and hope [28, 46, 71]. This mediation effect not only highlights the psychological processes contributing to flourishing but also emphasizes the need for an effective approach to promoting mental well-being among young individuals [72–75]. Overall, this study provides evidence that cultivating optimism and hope, alongside fostering a love of life, might play an important role in enhancing flourishing among Turkish youth. These findings contribute significantly to the field of positive psychology and underscore the importance of developing these positive psychological constructs in younger populations.

Implications

There are also several strengths in the present study. In particular, the use of the youth adds to the existing literature on love of life and flourishing by providing evidence to support the mediating effect of optimism and hope on the association between love of life and flourishing within the specific cultural context of Turkish youth. Mental health professionals treating individuals may find it beneficial to consider incorporating love-of-life therapy for those whose low levels of optimism and hope hinder their flourishing and well-being. Individuals struggling to regulate low levels of optimism and hope are prone to experiencing challenges in flourishing and may be susceptible to mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and stress. Prioritizing interventions that aim to enhance optimism and hope in therapy for clients facing difficulties in these areas may lead to an improvement in flourishing, contributing to the restoration of psychological health and functioning.

Limitations

This study has certain limitations. Firstly, it is important to note that the correlation between optimism and hope with flourishing appears to be relatively high. This may be attributed to a specific item “I am optimistic about my future” on the Flourishing Scale, which assesses optimism about the future. Considering the conceptual similarities between optimism and hope, the correlation between these three variables might have been influenced by the inclusion of this item in the Flourishing Scale. Secondly, participants were selected through a convenience sampling method. Future research can address this limitation by using more different sampling methods such as random sampling to enhance the generalizability of findings to a broader population. Thirdly, the study employed a cross-sectional design to assess the influence of the love of life on flourishing through optimism and hope in Turkish youths. Additionally, the reliance on self-report measures, while valuable, may introduce response biases and may not fully capture the subjective experiences of individuals [76]. Causal inferences are challenging in such a design. For a better understanding of the relationship between love of life and flourishing, future research should incorporate longitudinal or experimental studies to establish causal relationships. Fourthly, our sample consisted of participants from a specific group of enrolled undergraduate college students in Turkey, potentially possessing higher levels of education and intelligence compared to the general population. This characteristic may have impacted the obtained results. To improve the generalizability of findings, future research could consider multi-centre studies exploring diverse participant demographics and settings for a more representative and varied sample. Finally, another limitation of our study is the directionality of the relationships examined. Although we defined love of life as the independent variable and flourishing as the dependent variable, it is plausible that the reverse could also be true. Future research should explore the possibility of positioning flourishing as the independent variable, with the love of life as the dependent variable, and investigate the roles of other positive psychological constructs as mediating factors. This approach could help to further elucidate the bidirectional nature of these positive psychological constructs.

Conclusions

In summary, our findings reinforce the vital role of positive emotional states and attitudes, such as love of life, optimism, and hope, in the process of flourishing. The mediating role of optimism and hope in this dynamic further emphasizes the multifaceted nature of well-being and the necessity of a holistic approach to nurturing mental health in young individuals. As we continue to unravel the complexities of these relationships, it becomes increasingly clear that fostering a positive outlook on life is not just beneficial but essential for the psychological development and flourishing of youth. This study contributes to the growing body of knowledge in positive psychology, offering valuable insights for researchers, educators, and mental health professionals dedicated to supporting the well-being and resilience of younger generations

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all our participants who voluntarily contributed to this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Ağri İbrahim Çeçen University (protocol code 223 and 08.09.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, M.Y. and A.Ö.; methodology, M.Y. and A.Ö.; software, M.Y.; validation, IAA, A.R., F.C., and LS.; formal analysis, M.Y.; investigation, M.Y. and A.Ö.; resources, M.Y., A.Ö., and M.H.A.; data curation, M.Y. and A.Ö.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Y., A.Ö., M.H.A.; Reviewing-editing, M.Y., A.Ö., M.H.A, IAA, A.R., F.C., and LS.; visualisation, M.Y., A.Ö.,.; supervision, M.Y., A.Ö..; project administration, M.Y., A.Ö..; funding acquisition, M.Y., A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abdel-Khalek AM. Love of life as a new construct in the well-being domain. Soc Behav Personal Int J. 2007;35:125–34. 10.2224/sbp.2007.35.1.125. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dadfar M, Abdel-Khalek AM, Lester D. Love of life and its association with well-being in Iranian psychiatric outpatients. Nurs Open. 2020;7:1861–6. 10.1002/nop2.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alfalah AA, Alganem SA. The impact of construal level on happiness, hope, optimism, life satisfaction, and love of life: A longitudinal and experimental study. Aust J Psychol. 2020;72:359–67. 10.1111/ajpy.12297. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdel-Khalek, A. M.; Lester, D.; Dadfar, M.; Atef Vahid, M. K.; El Nayal, M. A.; Alhuwailah, A.; Zine El Abiddine, F.; Singh, A. P.; Turan, Y. An examination of culture and gender differences on the Love of Life Scale (LLS) and its psychometric properties. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2023, 26, 591–599. 10.1080/13674676.2022.2034772.

- 5.Yıldırım, M.; Özaslan, A. Love of Life Scale: Psychometric Analysis of a Turkish Adaptation and Exploration of Its Relationship with Well-Being and Personality. Gazi Medical Journal. 2022, 33, 158–162. 10.12996/gmj.2022.36.

- 6.Abdel-Khalek AM, Singh AP. Love of life, happiness, and religiosity in Indian college students. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2019;22:769–78. 10.1080/13674676.2019.1644303. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross LT, Owensby A, Kolak AM. Family Predictability and Psychological Wellness: Do Personal Predictability Beliefs Matter? J Child Fam Stud. 2023;32:3299–311. 10.1007/s10826-022-02383-1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdel-Khalek AM. Love of life and death distress: Two separate factors. Omega. 2007;55:267–78. 10.2190/OM.55.4.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dadfar M, Gunn JF III, Lester D, Abdel-Khalek AM. Love of Life Model: role of psychological well-being, depression, somatic health, and spiritual health. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2021;24:142–50. 10.1080/13674676.2020.1825360. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdel-Khalek, A. M.; Alhuwailah, A. H. The Big-Five Personality Factors as Predictors of Love of Life and Self-Esteem Among A Sample of Female Undergraduates in Kuwait University. Journal of Educational & Psychological Sciences. 2021, 22. 10.12785/jeps/210301. [DOI]

- 11.Vahid MKA, Dadfar M, Abdel-Khalek AM, Lester D. Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of the Love of Life Scale. Psychol Rep. 2016;119:505–15. 10.1177/0033294116665180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdel-Khalek AM. The relationships between subjective well-being, health, and religiosity among young adults from Qatar. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2013;16:306–18. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdel-Khalek AM. Subjective well-being and religiosity in Egyptian college students. Psychol Rep. 2011;108:54–8. 10.2466/07.17.PR0.108.1.54-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdel-Khalek AM. Love of life and its association with personality dimensions in college students. In: Sarracino F, editor. The Happiness Compass. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc; 2013. p. 53–65.

- 15.Abdel-Khalek AM, Lester D. Love of life in Kuwaiti and American college students. Psychol Rep. 2011;108:94–94. 10.2466/07.17.PR0.108.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdel-Khalek AM, Lester D. Constructions of religiosity, subjective well-being, anxiety, and depression in two cultures: Kuwait and USA. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2012;58:138–45. 10.1177/0020764010387545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi D-W, Oishi S, Biswas-Diener R. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. 2010;97:143–56. 10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fredrickson BL, Losada MF. Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. Am Psychol. 2005;60:678–86. 10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yildirim M, Belen H. The role of resilience in the relationships between externality of happiness and subjective well-being and flourishing: A structural equation model approach. Journal of Positive Psychology and Wellbeing. 2019;3:62–76. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keyes CL. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(2):207–22. [PubMed]

- 21.Keyes CLM. Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. Am Psychol. 2007;62:95–108. 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seligman ME. Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2011. ISBN 978--4391–9077–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willen SS, Williamson AF, Walsh CC, Hyman M, Tootle W. Rethinking flourishing: Critical insights and qualitative perspectives from the US Midwest. SSM Ment Health. 2022;2: 100057. 10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yildirim M. Optimism as a predictor of flourishing over and above the big five among youth. In: International Academic Studies Conference, Turkey, 20 May. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keyes CL, Kendler KS, Myers JM, Martin CC. The genetic overlap and distinctiveness of flourishing and the big five personality traits. J Happiness Stud. 2015;16:655–68. 10.1007/s10902-014-9527-2. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson C, Chang EV. Optimism and flourishing. In: Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived. American Psychological Association. 2003. p. 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banares, R. J.; Distor, J. M.; Llenares, I. I. Hope, Gratitude, and Optimism may contribute to Student Flourishing during COVID-19 Pandemic. In 2nd International Conference in Information and Computing Research (iCORE), 10–11 Dec. 2022; pp 247–251. 10.1109/iCORE58172.2022.00061.

- 28.Yildirim M. Mediating role of resilience in the relationships between fear of happiness and affect balance, satisfaction with life, and flourishing. Eur J Psychol. 2019;15:183–98. 10.5964/ejop.v15i2.1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yildirim, M.; Aziz, I. A.; Nucera, G.; Ferrari, G.; Chirico, F. Self-compassion mediates the relationship between mindfulness and flourishing. J Health Soc Sci. 2022, 7, 89–98. 10.19204/2022/SLFC6.

- 30.Yıldırım, M.; Aziz, I. A.; Vostanis, P.; Hassan, M. N. Associations among resilience, hope, social support, feeling belongingness, satisfaction with life, and flourishing among Syrian minority refugees. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2022, 1–16. Advance online publication. 10.1080/15332640.2022.2078918. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychol. 1985;4:219–47. 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schueller SM, Seligman ME. Optimism and pessimism. Dobson KS, Dozois DJA, editors. In Risk Factors in Depression. Elsevier; 2008. p 171–94.

- 33.Bouchard LC, Carver CS, Mens MG, Scheier MF. Optimism, health, and well-being. Positive psychology: Established and emerging issues. In: Positive Psychology. Routledge; 2017. p. 112–30.

- 34.Arslan G, Yıldırım M. Coronavirus stress, meaningful living, optimism, and depressive symptoms: a study of moderated mediation model. Aust J Psychol. 2021;73:113–24. 10.1080/00049530.2021.1882273. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dupuis E, Foster T. Understanding holistic wellness from a midlife perspective: a factor analytic study. Journal of Positive Psychology and Wellbeing. 2020;4:105–16. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duy B, Yıldız MA. The mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between optimism and subjective well-being. Curr Psychol. 2019;38:1456–63. 10.1007/s12144-017-9698-1. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jose PE, Lim BT, Kim S, Bryant FB. Does Savoring Mediate the Relationships between Explanatory Style and Mood Outcomes? Journal of Positive Psychology and Wellbeing. 2018;2:149–67. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reyes ME, Dillague SGO, Fuentes MIA, Malicsi CAR, Manalo DCF, Melgarejo JMT, Cayubit R. Self-esteem and optimism as predictors of resilience among selected Filipino active duty military personnel in military camps. J Posit School Psychol. 2020;4:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kardas F, Zekeriya C, Eskisu M, Gelibolu S. Gratitude, hope, optimism and life satisfaction as predictors of psychological well-being. Eurasian J Educ Res. 2019;19:81–100. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma R, Mohan J. Exploring the concept of Flourishing in relation to Optimism and Resilience. In: Hope, Efficacy, Resilience, Optimism Towards Holistic Living Virtual Conference, 14th – 15th May 2021. 2021. p. pp:229-234. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Snyder CR. Handbook of hope: Theory, measures, and applications. Academic press; 2000.

- 42.Genç E, Arslan G. Optimism and dispositional hope to promote college students’ subjective well-being in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Posit School Psychol. 2021;5:87–96. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Umucu E, Chan F, Phillips B, Tansey T, Berven N, Hoyt W. Evaluating Optimism, Hope, Resilience, Coping Flexibility, Secure Attachment, and PERMA as a Well-Being Model for College Life Adjustment of Student Veterans: A Hierarchical Regression Analysis. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2024;67:94–110. 10.1177/00343552221127032. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kennedy P, Lude P, Elfström M, Smithson E. Appraisals, coping and adjustment pre and post SCI rehabilitation: a 2-year follow-up study. Spinal cord. 2012;50:112–8. 10.1038/sc.2011.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krause JS, Edles PA. Injury perceptions, hope for recovery, and psychological status after spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2014;59(2):176. 10.1037/a0035778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belen H, Yildirim M, Belen FS. Influence of fear of happiness on flourishing: Mediator roles of hope agency and hope pathways. Aust J Psychol. 2020;72:165–73. 10.1111/ajpy.12279. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flores-Lucas V, Martínez-Sinovas R, López-Benítez R, Guse T. Hope and Flourishing: A Cross-Cultural Examination Between Spanish and South African Samples. In: Krafft AM, Guse T, Slezackova A, editors. Hope across cultures. Cross-Cultural Advancements in Positive Psychology. Cham: Springer; 2023. p. pp: 295-326. 10.1007/978-3-031-24412-4_8. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martins AR, Crespo C, Salvador Á, Santos S, Carona C, Canavarro MC. Does hope matter? Associations among self-reported hope, anxiety, and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with cancer. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2018;25:93–103. 10.1007/s10880-018-9547-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taysi E, Curun F, Orcan F. Hope, Anger, and Depression as Mediators for Forgiveness and Social Behavior in Turkish Children. J Psychol. 2015;149:378–93. 10.1080/00223980.2014.881313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yalçın İ, Malkoç A. The relationship between meaning in life and subjective well-being: Forgiveness and hope as mediators. J Happiness Stud. 2015;16:915–29. 10.1007/s10902-014-9540-5. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Munoz RT, Hanks H, Hellman CM. Hope and resilience as distinct contributors to psychological flourishing among childhood trauma survivors. Traumatology. 2020;26:177–84. 10.1037/trm0000224. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khodarahimi S. Hope and flourishing in an Iranian adults sample: Their contributions to the positive and negative emotions. Appl Res Qual Life. 2013;8:361–72. 10.1007/s11482-012-9192-8. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Diener, E.; Chan, M. Y. Happy people live longer: Subjective well‐being contributes to health and longevity. Appl. Psychol.-Health Well Being. 2011, 3, 1–43. 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01045.x.

- 54.Gallagher MW, Lopez SJ. Positive expectancies and mental health: Identifying the unique contributions of hope and optimism. J Posit Psychol. 2009;4:548–56. 10.1080/17439760903157166. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krok D, Telka E. Optimism mediates the relationships between meaning in life and subjective and psychological well-being among late adolescents. Curr Issues Pers Psychol. 2019;7:32–42. 10.5114/cipp.2018.79960. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Erickson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:1063–78. 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aydin G, Tezer E. The relationship of optimism to health complaints and academic performance. Psikoloji Dergisi. 1991;7:2–9. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, Holleran SA, Irving LM, Sigmon ST, Yoshinobu L, Gibb J, Langelle C, Harney P. The will and the ways: development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60:570–85. 10.1037//0022-3514.60.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tarhan S, Bacanlı H. Adaptation of dispositional hope scale into Turkish: Validity and reliability study. The Journal of Happiness & Well-Being. 2015;3:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Telef B. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the psychological well-being. In: 11th National Congress of Counseling and Guidance. 2011. p. pp 3-5. [Google Scholar]

- 62.West SG, Finch JF, Curran PJ. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Sage Publications, Inc; 1995. p. 56–75.

- 63.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press; 2013.

- 64.Arslan G, Genç E, Yıldırım M, Tanhan A, Allen K-A. Psychological maltreatment, meaning in life, emotions, and psychological health in young adults: A multi-mediation approach. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2022;132: 106296. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106296. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alganem SA, Alfalah AA. Religious Attitudes and their Relationships with Happiness, Hope, Optimism, Life satisfaction, and Love of Life among Kuwait University Students. Journal of Educational & Psychological Sciences. 2018;19:109–39. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kovich MK, Simpson VL, Foli KJ, Hass Z, Phillips RG. Application of the PERMA Model of Well-being in Undergraduate Students. Int Journal of Com WB. 2023;6(1):1–20. 10.1007/s42413-022-00184-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yıldırım M, Arslan G. Exploring the associations between resilience, dispositional hope, preventive behaviours, subjective well-being, and psychological health among adults during early stage of COVID-19. Curr Psychol. 2022;4:5712–22. 10.1007/s12144-020-01177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Finch J, Farrell LJ, Waters AM. Searching for the HERO in youth: Does psychological capital (PsyCap) predict mental health symptoms and subjective wellbeing in Australian school-aged children and adolescents? Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2020;51:1025–36. 10.1007/s10578-020-01023-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Umucu E, Grenawalt TA, Reyes A, Tansey T, Brooks J, Lee B, Gleason C, Chan F. Flourishing in student veterans with and without service-connected disability: Psychometric validation of the flourishing scale and exploration of its relationships with personality and disability. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2019;63:3–12. 10.1177/0034355218808061. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cervantes RC, Koutantos E, Cristo M, Gonzalez-Guarda R, Fuentes D, Gutierrez N. Optimism and the American Dream: Latino Perspectives on Opportunities and Challenges Toward Reaching Personal and Family Goals. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2021;43:135–54. 10.1177/07399863211036561. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wider W, Taib NM, Khadri MWABA, Yip FY, Lajuma S, Punniamoorthy PAL. The unique role of hope and optimism in the relationship between environmental quality and life satisfaction during COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:7661. 10.3390/ijerph19137661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Di Corrado D, Muzii B, Magnano P, Coco M, La Paglia R, Maldonato NM. The Moderated Mediating Effect of Hope, Self-Efficacy and Resilience in the Relationship between Post-Traumatic Growth and Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare. 2022;10:1091. 10.3390/healthcare10061091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Di Fabio A, Palazzeschi L, Bucci O, Guazzini A, Burgassi C, Pesce E. Personality Traits and Positive Resources of Workers for Sustainable Development: Is Emotional Intelligence a Mediator for Optimism and Hope? Sustainability. 2018;10:3422. 10.3390/su10103422. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Casu G, Hlebec V, Boccaletti L, Bolko I, Manattini A, Hanson E. Promoting Mental Health and Well-Being among Adolescent Young Carers in Europe: A Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2045. 10.3390/ijerph18042045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brolin R, Hanson E, Magnusson L, Lewis F, Parkhouse T, Hlebec V, Santini S, Hoefman R, Leu A, Becker S. Adolescent Young Carers Who Provide Help and Support to Friends. Healthcare. 2023;11:2876. 10.3390/healthcare11212876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lucas R. Reevaluating the strengths and weaknesses of self-report measures of subjective well-being. In: Diener E, Oishi S, Tay L, editors. Handbook of well-being. Salt Lake City, UT: DEF Publishers; 2018. p. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.