Abstract

Background

The impact of mode of delivery in chorioamnionitis on neonatal outcomes is unclear. This retrospective cohort study compares the rate of early onset neonatal sepsis between vaginal delivery and cesarean section.

Methods

Singleton pregnancies at greater than 24 + 0 weeks gestation with live birth and clinically-diagnosed chorioamnionitis from January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2021 were included. Cases with multiple gestations, terminations or histological chorioamnionitis alone were excluded. Rates of early onset neonatal sepsis, select secondary neonatal outcomes and a composite outcome of maternal infectious morbidity were compared using propensity score weighting. Subgroup analysis was done by indication for cesarean section.

Results

After chart review, 378 cases were included with 197 delivering vaginally and 181 delivering via cesarean section. The groups differed on age, parity, hypertension, renal disease, gestational age, corticosteroid use, magnesium sulfate use, presence of meconium and percentage meeting Gibbs criteria before propensity score weighting. Rate of early onset neonatal sepsis was greater in the cesarean section group (13.8% versus 3.1%, adjusted risk difference 8.3% [3.5–13.1], p < 0.001). Secondary neonatal outcomes were similar between groups. When compared by indication, the rate of early onset neonatal sepsis was greater in the cesarean section for abnormal fetal surveillance group compared to vaginal delivery but not in the cesarean section for other reasons group. Adjusted rates of secondary neonatal outcomes did not differ between groups. The rate of maternal infectious morbidity was greater with cesarean section. (13.8% versus 1.5% [adjusted risk difference 13.0% [7.1–18.9], p < 0.0001). No other difference in maternal secondary outcomes was identified.

Conclusions

The rate of early onset neonatal sepsis was highest in the cesarean section group, particularly in those with abnormal fetal surveillance. Fetuses affected by or vulnerable to sepsis likely have a greater need for cesarean section.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12884-024-06877-2.

Keywords: Chorioamnionitis, Vaginal delivery, Cesarean delivery, Early onset neonatal sepsis

Background

Chorioamnionitis is an ascending infection of the uterine contents including any of the placenta, membranes, amniotic fluid, fetus or decidua [1]. It affects approximately 3.9% of pregnancies worldwide and up to 15% of preterm deliveries [2, 3], and has been linked to both maternal and neonatal adverse outcomes. For neonates, chorioamnionitis increases the risk of short-term adverse outcomes including low Apgar score, need for mechanical ventilation, seizures and infections including sepsis, particularly in the preterm neonate [4–7]. In the obstetrical patient, it is one of the leading causes of sepsis during pregnancy and is associated with infectious morbidity postpartum [8]. The current gold standard for diagnosis of chorioamnionitis is histological evidence of inflammation of the chorion and amnion. However, in practice, chorioamnionitis is diagnosed clinically. Gibbs criteria, which include maternal fever with at least one additional sign of infection such as maternal tachycardia, fetal tachycardia, uterine tenderness, foul smelling amniotic fluid or maternal leukocytosis, are considered sufficient for a clinical diagnosis of chorioamnionitis [1, 9, 10]. Diagnosis necessitates treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics as well as prompt delivery [11]. However, chorioamnionitis is not an indication for cesarean section [1]. Still, the impact of cesarean section compared to vaginal delivery on neonatal outcomes is unclear.

One small cohort study of infants born at 24–34 weeks gestational age compared vaginal delivery to cesarean section in chorioamnionitis [12]. No difference in neonatal sepsis, survival, respiratory distress syndrome or necrotizing enterocolitis was found between the two groups [12]. Likewise, no difference in periventricular leukomalacia, grade 3–4 intraventricular hemorrhage or seizure was identified between the groups [12]. However, the sample size was small and no adjustment for potential confounders was done. Other studies have examined the impact of duration of diagnosed chorioamnionitis as a surrogate for comparing delivery method. It is thought that if longer duration of chorioamnionitis does not adversely impact outcomes, then there is no reason to expedite delivery by cesarean section rather than continue labour. Several studies have reported no difference in adverse outcomes as the duration of chorioamnionitis increased [4, 13–15], although one study did report a greater rate of the composite neonatal adverse outcome as the length of the second stage of labour increased [15]. One other cohort study of term cesarean sections reported an increase in the risk of low Apgar score and the need for mechanical ventilation with a greater duration of chorioamnionitis [5]. Overall, there is a paucity of information available about the risk of neonatal infection after cesarean section compared to vaginal delivery.

The main question of interest to the obstetrician is if a cesarean section at the time of diagnosis of chorioamnionitis would decrease the risk of infection for the fetus, but given the evidence to date, a randomized controlled trial to answer this question would be unethical. Therefore, this retrospective cohort study accomplished through chart review assessed neonatal and maternal outcomes in chorioamnionitis with the primary aim of comparing the rate of early-onset neonatal sepsis after cesarean section or vaginal delivery. A secondary analysis was done to compare outcomes by indication for cesarean section (abnormal fetal surveillance versus other reasons), with the aim of elucidating if cesarean section carried benefit in cases where there was not an abnormal fetal heart rate suggestive of infection or fetal compromise.

Methods

This project adhered to national guidelines for ethical research and local research ethics board approval was obtained from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (REB#13988-C). The study population consisted of patients with clinically-diagnosed chorioamnionitis and their neonates from January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2021 at McMaster University Medical Centre. Singleton pregnancies with a gestational age greater than 24 weeks resulting in a live birth were included. Multiple gestations and terminations of pregnancy were excluded.

Cases were identified through the local Canadian Neonatal Network (CNN) database, Better Outcomes Registry and Network (BORN) and through the Hamilton Health Sciences Department of Decision Services. The local CNN data recorded either clinically-diagnosed or histological chorioamnionitis in the pregnancy for all infants admitted to the level three Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at McMaster University Medical Centre. BORN records characteristics and delivery parameters for all delivering patients in Ontario and was queried for diagnosis of clinical chorioamnionitis during pregnancy and delivery. Finally, the Department of Decision Services at McMaster University Medical Centre provided a list of charts with a recorded diagnosis of chorioamnionitis or with a history of receiving typical antibiotics for treatment of chorioamnionitis (ceftriaxone/metronidazole or ampicillin/tobramycin based on local practice) during the antenatal, intrapartum or postpartum periods. All patients who had a recorded diagnosis of clinical chorioamnionitis in their chart as determined by the obstetrical care team or who received treatment for clinically-diagnosed chorioamnionitis were included. At our centre, chorioamnionitis is diagnosed with a one time maternal temperature over 39 degrees Celsius or two measured temperatures between 38.0 and 38.9 degrees Celsius with an additional sign of chorioamnionitis (maternal tachycardia, fetal tachycardia, leukocytosis, malodorous fluid, uterine tenderness). Cases with histological chorioamnionitis alone were excluded after chart review. Maternal and neonatal characteristics, details of the delivery and clinical signs of chorioamnionitis as well as maternal and neonatal outcomes were recorded.

The primary neonatal outcome was early onset neonatal sepsis as determined by the neonatology care team. Sepsis occurring before 48 h of life was considered early onset. Cases were included if they were culture-confirmed or if the infant received a full course of antibiotics for a recorded diagnosis of culture-negative sepsis. Secondary outcomes included a five minute Apgar score less than 7, need for respiratory support during neonatal resuscitation, NICU admission, respiratory distress syndrome, need for respiratory support in the NICU, neonatal seizures or neonatal death. The primary maternal outcome was a composite of infectious complications including surgical site or perineal infection, pelvic abscess, endometritis, sepsis or septic pelvic thrombophlebitis. Secondary outcomes were maternal death, postpartum hemorrhage, need for blood transfusion, admission to a monitored setting (Intensive Care Unit (ICU) or step-down unit) or hysterectomy. Length of stay after delivery was also assessed.

Statistical analysis

Vaginal delivery and cesarean section were compared. Planned subgroup analysis was done for preterm pregnancies (36 + 6 and less) and term pregnancies (37 + 0 and greater) as well as the population of patients with clinical chorioamnionitis who were later confirmed to have histological chorioamnionitis. A second pre-planned comparison between vaginal delivery, cesarean section for an abnormal fetal surveillance and cesarean section for other reasons (dystocia, malpresentation, previous cesarean section, contraindication to vaginal delivery, maternal request or other) was also completed to assess if the rate of early-onset neonatal sepsis differed when cesarean section was completed in cases where fetal compromise was not suspected. The duration of antibiotic treatment prior to delivery was also examined as a proxy for the duration between diagnosis of chorioamnionitis and delivery as antibiotics are typically started when chorioamnionitis is diagnosed. This duration was also compared between the groups in cases of early onset neonatal sepsis.

Data are reported as number of events with percentage for categorical data and as mean with standard deviation for quantitative data. Baseline characteristics not included in the propensity score were compared with Fisher’s exact test for categorical data and t-test for continuous data. Non-normally distributed data was log-transformed for analysis. With multiple group comparisons, chi-squared test and ANOVA were used respectively. Here, a p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For comparison of the groups, propensity score weighting was used. Covariates included in the propensity score were: age, parity, use of artificial reproductive technologies, lack of prenatal care, maternal tobacco exposure, maternal alcohol exposure, maternal marijuana exposure, maternal diabetes, maternal hypertension, maternal cardiovascular disease, maternal renal disease, maternal neurological disease, maternal rheumatological disease, maternal immunosuppression, Group B Streptococcus (GBS) status, gestational age at delivery, birth weight, neonatal sex, neonatal congenital anomaly, use of antenatal corticosteroids, administration of antenatal magnesium sulfate, if there had been a previous cesarean section, presence of meconium, if Gibbs criteria for chorioamnionitis were met and if antibiotic treatment for chorioamnionitis was initiated prior to delivery. Logistic regression was used to calculate propensity scores for the mode of delivery and the overlap weights method was used to balance the groups. Baseline characteristics included in the propensity score were compared using the standardized mean difference with a value greater than 0.1 taken to be a significant difference. For comparison of outcomes, risk differences with 95% confidence intervals were reported. Logistic regression was also used to assess if duration of antibiotic treatment was associated with early onset neonatal sepsis. Missing data were input as “no” for categorical variables and outcomes. All data were analyzed using the statistical program “R” and the “PSweights” package [16].

Results

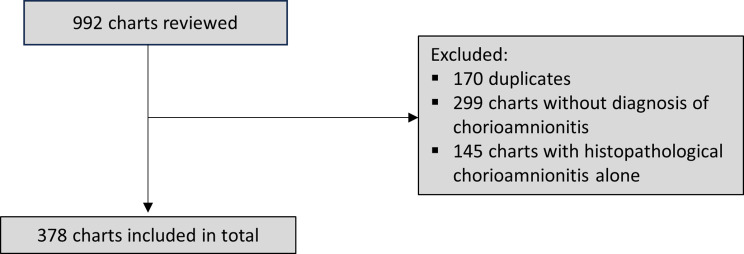

During the pre-determined time period, 992 possible cases were identified (277 from the CNN database, 60 from BORN, and 655 from Decision Services). Of these cases, 170 were duplicates, 299 did not have a diagnosis of chorioamnionitis, and 145 had only histological chorioamnionitis. These charts were excluded, leaving 378 total cases for inclusion in the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Cases were identified from the local Canadian Neonatal Network database, the Better Outcomes Registry and Network and through chart review. Duplicates and cases that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, leaving 378 cases

Baseline characteristics were compared between patients who delivered vaginally and those who delivered by cesarean section (Table 1). The groups differed by age, parity, maternal hypertension, maternal renal disease, gestational age, corticosteroid administration, magnesium sulfate administration, presence of meconium and by number of patients meeting Gibbs criteria at baseline. These differences were balanced after propensity score weighting. Type of labour, type of rupture of membranes and fetal presentation also differed between groups as expected, with no labour, rupture at cesarean section and non-cephalic presentations only present in the cesarean section group (data not shown).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics before and after weighting using propensity scores

| Unweighted | Propensity score weighted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Characteristics |

Vaginal Delivery (n = 197) |

Cesarean Delivery (n = 181) |

Standardized mean difference |

Vaginal Delivery (n = 171 effective sample size) |

Cesarean Delivery (n = 158 effective sample size) |

Standardized mean difference |

| Maternal Characteristics | ||||||

| Age (years) | 30.2 ± 5.22 | 31.4 ± 5.32 | 0.227 | 30.7 ± 5.16 | 30.7 ± 5.44 | 0 |

| Parity | ||||||

| 0 | 157 (79.7%) | 140 (77.4%) | 0.057 | 80.1% | 80.1% | 0 |

| 1 | 24 (12.2%) | 32 (17.7%) | 0.154 | 14.5% | 14.5% | 0 |

| 2 | 8 (4.1%) | 5 (2.8%) | 0.071 | 2.9% | 2.9% | 0 |

| > 3 | 8 (4.1%) | 4 (2.2%) | 0.106 | 2.5% | 2.5% | 0 |

| Artificial Reproductive Technology | 17 (8.6%) | 13 (7.2%) | 0.054 | 8.5% | 8.5% | 0 |

| No prenatal care | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.006 | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0 |

| Tobacco exposure | 15 (7.6%) | 14 (7.7%) | 0.005 | 6.7% | 6.7% | 0 |

| Alcohol exposure | 3 (1.5%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0.037 | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0 |

| Marijuana exposure | 6 (3.0%) | 5 (2.8%) | 0.017 | 2.6% | 2.6% | 0 |

| Maternal diabetes* | 30 (15.2%) | 33 (18.2%) | 0.080 | 15.5% | 15.5% | 0 |

| Hypertension** | 10 (5.1%) | 18 (9.9%) | 0.185 | 7.0% | 7.0% | 0 |

| Maternal cardiovascular disease | 4 (2.0%) | 3 (1.7%) | 0.028 | 1.8% | 1.8% | 0 |

| Maternal renal disease | 6 (3.05%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0.136 | 1.8% | 1.8% | 0 |

| Maternal neurological disease | 16 (8.1%) | 12 (6.6%) | 0.057 | 7.0% | 7.0% | 0 |

| Maternal rheumatological disease | 3 (1.5%) | 5 (2.8%) | 0.085 | 2.0% | 2.0% | 0 |

| Maternal immunosuppression | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.006 | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0 |

| GBS status | ||||||

| Negative | 147 (74.6%) | 136 (75.1%) | 0.012 | 76.2% | 76.2% | 0 |

| Positive | 47 (23.9%) | 37 (20.4%) | 0.082 | 21.6% | 21.6% | 0 |

| Not done | 3 (1.5%) | 8 (4.4%) | 0.171 | 2.2% | 2.2% | 0 |

| Neonatal Characteristics | ||||||

| Gestational age (weeks) | 38.2 ± 3.71 | 37.8 ± 4.07 | 0.106 | 38.2 ± 3.95 | 38.2 ± 3.71 | 0 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3145 ± 794 | 3138 ± 914 | 0.009 | 3180 ± 837 | 3180 ± 829 | 0 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 103 (52.3%) | 99 (54.7%) | 0.048 | 54.9% | 54.9% | 0 |

| Female | 94 (47.7%) | 82 (45.3%) | 0.048 | 45.1% | 45.1% | 0 |

| Congenital anomaly | ||||||

| None | 176 (89.3%) | 166 (91.7%) | 0.081 | 89.8% | 89.8% | 0 |

| Minor | 16 (8.1%) | 10 (5.5%) | 0.103 | 7.1% | 7.1% | 0 |

| Major | 5 (2.5%) | 5 (2.8%) | 0.014 | 3.1% | 3.1% | 0 |

| Corticosteroids | ||||||

| Complete course | 23 (11.7%) | 29 (16.0%) | 0.126 | 12.5% | 12.5% | 0 |

| Incomplete course | 2 (1.0%) | 4 (2.2%) | 0.095 | 1.6% | 1.6% | 0 |

| Not received | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0.067 | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0 |

| Not indicated | 171 (86.8%) | 146 (80.7%) | 0.166 | 85.4% | 85.4% | 0 |

| Magnesium sulfate | ||||||

| Received | 19 (9.6%) | 30 (16.6%) | 0.107 | 12.0% | 12.0% | 0 |

| Not received | 5 (2.5%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0.206 | 1.2% | 1.2% | 0 |

| Not indicated | 173 (87.8%) | 149 (82.3%) | 0.154 | 86.9% | 86.9% | 0 |

| Labour Characteristics | ||||||

| Previous cesarean section | 10 (5.1%) | 10 (5.5%) | 0.020 | 4.3% | 4.3% | 0 |

| Rupture of membranes# | ||||||

| PPROM | 27 (13.7%) | 38 (21.0%) | 0.193 | -- | -- | -- |

| Term PROM | 45 (22.8%) | 38 (21.0%) | 0.045 | |||

| Spontaneous ROM | 34 (17.3%) | 23 (12.7%) | 0.189 | |||

| Amniotomy | 85 (43.1%) | 74 (40.9%) | 0.046 | |||

| At cesarean section | 0 | 7 (3.9%) | 0.283 | |||

| Meconium | 51 (25.9%) | 59 (32.6%) | 0.147 | 29.8% | 29.8% | 0 |

| Chorioamnionitis Characteristics | ||||||

| Histological findings# | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||

| Histopathological chorioamnionitis | 70 (35.6%) | 100 (55.2%) | ||||

| No evidence | 15 (7.6%) | 22 (12.2%) | ||||

| Placenta not sent to pathology | 112 (56.9%) | 59 (32.6%) | ||||

| Meeting Gibbs Criteria | 88 (44.7%) | 52 (28.7%) | 0.334 | 36.3% | 36.3% | 0 |

| Antibiotics for chorioamnionitis before delivery | 130 (66.0%) | 120 (66.3%) | 0.007 | 67.8% | 67.8% | 0 |

| Duration of antibiotics before delivery (hr)## | 1.90 ± 3.16 | 2.32 ± 5.05 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

Group B Streptococcus (GBS), preterm prelabour rupture of membranes (PPROM), prelabour rupture of membranes (PROM), rupture of membranes (ROM)

# Statistically significant difference between groups by Fisher’s Exact test

## No statistically significant difference between groups by t- test after removal of 3 outliers with values > 100 h and log-transformation of the data

* included gestational diabetes and pre-pregnancy diabetes

** included pre-pregnancy hypertension, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia and superimposed preeclampsia

Comparison of neonatal outcomes between vaginal delivery and cesarean section revealed a higher rate of early onset neonatal sepsis in the cesarean section group (8.3% [3.5–13.1] adjusted risk difference, p < 0.001) (Table 2). Secondary neonatal outcomes were not different between groups after propensity score weighting (Table 2). In the subset of patients who had later histological confirmation of chorioamnionitis, the greater rate of early onset neonatal sepsis in the cesarean section group was preserved with a rate of 7.1% in the vaginal delivery group and a rate of 23% in the cesarean section group (16.5% [5.2–27.9] adjusted risk difference, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Comparison of neonatal outcomes between vaginal delivery and cesarean section using propensity score weighting

| Outcomes | Vaginal Delivery (n = 197) n (%) |

Cesarean Section (n = 181) n (%) |

Unweighted risk difference (%, 95% CI) |

Weighted risk difference (%, 95% CI) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early onset neonatal sepsis | 6 (3.1%) | 25 (13.8%) | 10.7% [5.2–16.3] | 8.3% [3.5–13.1] | < 0.001 |

| Apgar < 7 at 5 min | 18 (9.1%) | 27 (14.9%) | 5.8% [-0.8-12.3] | 3.3% [-2.5-9.0] | 0.268 |

| Need for neonatal resuscitation | 63 (32.0%) | 69 (38.1%) | 6.1% [-3.5-15.8] | -2.4% [-10.5-5.7] | 0.565 |

| NICU admission | 65 (33.0%) | 73 (40.3%) | 7.3% [-2.4-17.0] | 1.9% [-6.2-9.9] | 0.649 |

| Respiratory distress syndrome | 27 (13.7%) | 37 (20.4%) | 6.7% [-0.9-14.3] | 1.3% [-2.9-5.5] | 0.540 |

| Respiratory support in NICU | 39 (19.8%) | 56 (30.9%) | 11.1% [2.4–19.9] | 5.4% [-0.6-11.3] | 0.077 |

| Neonatal seizures | 2 (1.0%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0.09% [-2.0-2.2] | -0.2% [-1.1-0.8] | 0.742 |

| Neonatal death | 2 (1.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.6% [-1.2-2.4] | -0.7% [-2.3-1.0] | 0.437 |

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)

The duration of antibiotic treatment before delivery did not differ between the vaginal delivery and cesarean section groups (1.90 h ± 3.16 in the vaginal delivery group versus 2.32 ± 5.05 in the cesarean section group, p = 0.390). Duration of antibiotic treatment prior to delivery also did not differ between cases with early onset neonatal sepsis in the vaginal delivery group and in the cesarean section group (2.87 h ± 1.87 in vaginal delivery, versus 2.35 h ± 5.42 in cesarean section, p = 0.092). The duration of antibiotic treatment prior to delivery was not associated with risk of early onset neonatal sepsis (p = 0.630).

Subgroup analysis of preterm and term pregnancies found similar results. Baseline characteristics in these subgroups were balanced after propensity score weighting (Table S1; Table S2). In the preterm group, rate of early onset neonatal sepsis was greater in the cesarean section group (52.4% [41.1–63.7] adjusted risk difference, p < 0.00001). In the term group, the unadjusted risk difference for early onset neonatal sepsis was greater in the cesarean section group but significance disappeared with propensity score weighting (4.1% [-0.5–8.6] adjusted risk difference, p = 0.079).

A planned comparison between vaginal delivery, cesarean section for abnormal fetal surveillance and cesarean section for other reasons was completed. Propensity score weighting was used but differences between the groups remained in baseline characteristics, specifically in parity, marijuana exposure, GBS status, neonatal sex, and neonatal congenital anomalies (Table S3). This analysis revealed a greater rate of early onset neonatal sepsis in the cesarean section for abnormal fetal surveillance group compared to vaginal delivery (13.4% [4.4–22.4 adjusted risk difference, p < 0.01; Table 3). No secondary neonatal outcomes were different between the vaginal delivery and cesarean section for abnormal fetal surveillance groups after propensity score weighting (Table 3). Comparison of the cesarean section for other reasons and vaginal delivery groups did not show a significant difference in the rate of early onset neonatal sepsis (2.8% [-4.1–9.6] adjusted risk difference, p = 0.430; Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of neonatal outcomes between vaginal delivery, cesarean section for abnormal fetal surveillance, and cesarean section for an indication other than abnormal fetal surveillance using propensity score weighting

| Outcomes | Vaginal Delivery (Reference group) n = 197 |

Cesarean Section for Abnormal Fetal Surveillance n = 96 |

Unweighted risk difference | Risk difference (relative to vaginal delivery) | p value | Cesarean Section for Other Reason n = 85 |

Unweighted risk difference | Risk difference (relative to vaginal delivery) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early onset neonatal sepsis | 6 (3.1%) | 17 (17.7%) | 14.7% [6.7–22.7] | 13.4% [4.4–22.4] | < 0.01 | 8 (9.4%) | 6.4% [-0.3-13.0] | 2.8% [-4.1-9.6] | 0.430 |

| Apgar < 7 at 5 min | 18 (9.1%) | 19 (19.8%) | 10.7% [1.7–19.6] | 3.8% [-4.9-12.5] | 0.390 | 8 (9.4%) | 0.3% [-7.1-7.7] | -0.3% [-9.0-8.3] | 0.938 |

| Need for neonatal resuscitation | 63 (32.0%) | 41 (42.7%) | 10.7% [-1.1-22.6] | 0.6% [-13.0-14.2] | 0.929 | 28 (32.9%) | 1.0% [-11.0-12.9] | -6.3% [-19.8-7.2] | 0.361 |

| NICU admission | 65 (33.0%) | 44 (45.8%) | 12.8% [0.9–24.8] | 5.6% [-8.1-19.3] | 0.424 | 29 (34.1%) | 1.1% [-10.9-13.2] | -6.7% [-20.0-6.5] | 0.318 |

| Respiratory distress syndrome | 27 (13.7%) | 24 (25.0%) | 11.3% [1.4–21.2] | 4.0% [-6.5-14.5] | 0.457 | 13 (15.3%) | 1.6% [-7.4-10.6] | 0.6% [-10.2-11.4] | 0.913 |

| Respiratory support in NICU | 39 (19.8%) | 35 (36.5%) | 16.7% [5.5–27.8] | 10.0% [-2.4-22.4] | 0.114 | 21 (24.7%) | 4.9% [-5.8-15.6] | 0.06% [-11.6-11.8] | 0.992 |

| Neonatal seizures | 2 (1.0%) | 2 (2.1%) | 1.1% [-2.1-4.2] | 0.4% [-0.7-1.4] | 0.467 | 0 (0%) | -1.0% [-2.4-0.4] | -0.2% [-0.7-0.2] | 0.318 |

| Neonatal death | 2 (1.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0.03% [-2.4-2.5] | -0.4% [-2.2-1.5] | 0.687 | 0 (0%) | -1.0% [-2.4-0.4] | -1.0% [-2.4-0.4] | 0.161 |

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)

Comparison of maternal outcomes between the vaginal delivery and cesarean section groups found a significantly greater rate of infectious morbidity in the cesarean section group (13.0% [7.1–18.9% adjusted risk difference, p < 0.0001; Table 4). Otherwise, there was no significant difference in rates of postpartum hemorrhage, need for blood transfusion, need for admission to a monitored setting or hysterectomy (Table 4). There were no cases of maternal death in the cohort. Duration of hospital stay after delivery was significantly greater in the cesarean section group (1.6 days ± 0.92 in the vaginal delivery group versus 2.3 days ± 0.93 in the cesarean section group, p < 0.00001).

Table 4.

Maternal outcomes by mode of delivery with weighting by propensity scoring

| Outcomes | Vaginal Delivery (n = 197) (n, %) |

Cesarean Section (n = 181) (n, %) |

Unweighted risk difference | Weighted risk difference | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite outcome of infectious morbidity | 3 (1.5%) | 25 (13.8%) | 12.3% [7.0-17.6] | 13.0% [7.1–18.9] | < 0.0001 |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 27 (13.7%) | 17 (9.4%) | -4.3% [-10.7-2.1] | -3.5% [-9.9-2.9] | 0.288 |

| Blood transfusion | 5 (2.5%) | 7 (3.9%) | 1.3% [-2.2-4.9] | 1.1% [-2.9-5.1] | 0.5970 |

| Monitored setting admission | 6 (3.1%) | 11 (6.1%) | 3.0% [-1.2-7.3] | 3.3% [-1.4-7.9] | 0.170 |

| Hysterectomy | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.04% [-1.4-1.5] | 0.7% [-0.6-1.9] | 0.286 |

Discussion

This single-centre retrospective cohort study compared neonatal and maternal outcomes in clinically-diagnosed chorioamnionitis by mode of delivery and found a higher rate of early onset neonatal sepsis in the cesarean section group. This difference was preserved in the preterm, although not in the term subgroup. When the rate of early onset neonatal sepsis was examined by the indication for cesarean section, the greater rate remained present compared to vaginal delivery only when there was abnormal fetal surveillance. The group that underwent cesarean section for reasons other than abnormal fetal surveillance, most commonly dystocia, did not have a rate of early onset neonatal sepsis different from the vaginal delivery group. As cesarean section in and of itself is unlikely to directly cause infection in a neonate, we suggest that the fetuses vulnerable to infection or already infected demonstrate abnormal fetal heart rates requiring delivery by cesarean section. In particular, the rate of early onset neonatal sepsis was highest in the preterm population undergoing cesarean section, reflecting the increased vulnerability of this group.

Our composite maternal outcome included surgical site or perineal infection, pelvic abscess, endometritis, sepsis or septic pelvic thrombophlebitis, all of which have been demonstrated to be increased with cesarean section, and moreover, increased in the context of chorioamnionitis [17–20]. As expected, in our study, maternal infectious morbidity was greater in the cesarean section group. Duration of stay was also significantly greater in the cesarean section group as post-operative patients typically have a two day stay versus one day post vaginal delivery. The mean duration of stay post-delivery reflected the expected length of stay after vaginal delivery and cesarean section respectively, suggesting chorioamnionitis did not significantly increase length of stay regardless of mode of delivery.

Multiple other studies have demonstrated no increase in adverse neonatal outcomes with increasing duration of chorioamnionitis [4, 13–15, 21, 22]. Our study replicated these results, showing no significant difference in duration of antibiotics between the two groups, even if restricted to cases of early onset neonatal sepsis. Duration of antibiotic treatment was also not significantly associated with early onset neonatal sepsis. Although it was not possible to assess duration of fever before antibiotics, it is standard practice at our institution to start antibiotics when chorioamnionitis is diagnosed, typically after two fevers greater than 38oC with an additional clinical sign of chorioamnionitis. We would not expect the duration of fever before initiation of antibiotics to differ significantly between the groups. Strengths of the study include a priori definition of outcomes, the ability to review maternal and neonatal charts in detail and a thorough identification of cases using multiple methods. The identified number of cases is close to the anticipated number based on risk of chorioamnionitis and annual deliveries at the site suggesting the majority were identified and included. The rate of cesarean section was high at 47.9% but this is in keeping with the increased risk for cesarean section either due to abnormal fetal heart rate or dystocia in chorioamnionitis. In 2016 and 2019, similar rates of cesarean section in chorioamnionitis were reported in the United States [20, 23]. The rate of early onset neonatal sepsis in our cohort is also in keeping with the rates reported in the literature. In total, 8.2% of neonates in our cohort developed early onset sepsis. Previous work has documented the incidence of early onset neonatal sepsis in chorioamnionitis at 7–10% overall [24]. Although this is a single-centre study and practice patterns may differ at other sites, national guidelines exist that recommend cesarean section only for obstetrical indications in chorioamnionitis. The decisions regarding mode of delivery in chorioamnionitis are likely similar at other centres. Finally, the broad definition of clinical chorioamnionitis with exclusion of cases of histological chorioamnionitis alone preserves generalizability of the results to the typical heterogeneous clinical population.

Limitations of the study include possible missed diagnoses of early onset neonatal sepsis based on differences in practice patterns between neonatology teams over time. Inclusion of culture-negative early onset sepsis cases may also have led to inclusion of cases that would not have met diagnostic criteria at other centres as this diagnosis was at the discretion of the treating neonatologist. However, other objective secondary outcomes including neonatal mortality, admission to the NICU and need for respiratory support were included. Any undiagnosed early onset neonatal sepsis did not lead to mortality or other morbidity that would have been reflected in the secondary outcomes. When considering maternal outcomes, two potential confounders, BMI and education, were not included in the analysis due to a high rate of missing data for these characteristics in the patient charts. Maternal outcomes occurring after discharge could also have been missed if the patient presented to care elsewhere. However, patients can present to care at our Labour and Delivery triage up to 6 weeks postpartum, providing a reasonable follow-up period. Finally, as this study includes only observational data, it cannot be fully excluded that the vaginal delivery and cesarean section groups differ despite the use of propensity score weighting. More severe or earlier-onset chorioamnionitis could lead to abnormal fetal heart rates or dystocia requiring cesarean section, and our chart review did not allow direct assessment of fetal heart rate tracings.

Overall, our study supports the current clinical guidelines for management of chorioamnionitis which recommend cesarean section for obstetrical indications only in chorioamnionitis, as opting for cesarean section imposes additional maternal risk with no decrease in fetal risk for early onset neonatal sepsis. Although it cannot be fully excluded that cesarean section at the time of diagnosis of chorioamnionitis could decrease neonatal morbidity, there is no evidence for fetal benefit in this study or in previous work [4]. Given that diagnosis of chorioamnionitis includes signs of fetal distress including tachycardia, it is likely that any fetal infection has already occurred at the time of diagnosis of chorioamnionitis. Furthermore, the mean time to delivery in both the vaginal delivery and the cesarean section groups in our study was short and likely not clinically significant with respect to the risk of infection in the neonates. Future directions for research include improving accurate diagnosis of chorioamnionitis for both clinical and research purposes. Improved culture techniques or biomarkers may be helpful targets for improvements in care. Identification of risk factors for eventual cesarean section should also be prioritized.

Conclusions

In our study, there was no fetal benefit to cesarean section as the rate of early-onset neonatal sepsis was highest in the cesarean section group, but there was an increase in maternal infectious morbidity. Altogether, our results support the recommendation to pursue vaginal delivery in chorioamnionitis with cesarean section reserved for obstetrical indications.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BORN

Better Outcomes Registry and Network

- CNN

Canadian Neonatal Network

- GBS

Group B Streptococcus

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

- NICU

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

Author contributions

VRK and MM designed the study with assistance from JT. VRK and IL acquired the data. Data analysis was completed by VRK. The manuscript was drafted by VRK and MM and was reviewed and approved by IL and JT.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the PSI Foundation awarded to VRK. The funder had no role in conducting the study or preparing this report.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analysed for this study is not publicly available as ethics approval was not obtained for the data to be shared, even in anonymized format.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This project adhered to national guidelines for ethical research and local approval was obtained from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board. REB#13988-C. Approval Date: November 3, 2021. Informed consent was waived by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board due to the nature of the retrospective chart review design.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.ACOG. Committee Opinion 712: Intrapartum Management of Intraamniotic Infection. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):e95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodd SL, Montoya A, Barreix M, Pi L, Calvert C, Rehman AM et al. Incidence of maternal peripartum infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2019;16(12):e1002984. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Soraisham AS, Singhal N, McMillan DD, Sauve RS, Lee SK. A multicenter study on the clinical outcome of chorioamnionitis in preterm infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(4):372.e1-372.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venkatesh KK, Jackson W, Hughes BL, Laughon MM, Thorp JM, Stamilio DM. Association of chorioamnionitis and its duration with neonatal morbidity and mortality. J Perinatol. 2019;39(5):673–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rouse DJ, Landon M, Leveno KJ, Leindecker S, Varner MW, Caritis SN, et al. The maternal-fetal medicine units cesarean registry: Chorioamnionitis at term and its duration - relationship to outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):211–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsey PS, Lieman JM, Brumfield CG, Carlo W. Chorioamnionitis increases neonatal morbidity in pregnancies complicated by preterm premature rupture of membranes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Mosby Inc.; 2005. pp. 1162–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Neufeld MD, Frigon C, Graham AS, Mueller BA. Maternal infection and risk of cerebral palsy in term and preterm infants. J Perinatol. 2005;25(2):108–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Pundir J, Coomarasamy A. Bacterial sepsis in pregnancy. Obstet Evidence-based Algorithms. 2016;(64):87–9.

- 9.Ona S, Easter SR, Prabhu M, Wilkie G, Tuomala RE, Riley LE et al. Diagnostic validity of the proposed Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Criteria for intrauterine inflammation or infection. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(1):33–9. https://journals.lww.com/00006250-201901000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Sung JH, Choi SJ, Oh SY, Roh CR, Kim JH. Revisiting the diagnostic criteria of clinical chorioamnionitis in preterm birth. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;124(5):775–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puopolo KM, Draper D, Wi S, Newman TB, Zupancic J, Lieberman E et al. Estimating the probability of neonatal early-onset infection on the basis of maternal risk factors. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Grisaru-Granovsky S, Schimmel MS, Granovsky R, Diamant YZ, Samueloff A. Cesarean section is not protective against adverse neurological outcome in survivors of preterm delivery due to overt chorioamnionitis. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2003;13(5):323–7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12916683/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Ashwal E, Salman L, Tzur Y, Aviram A, Ben-Mayor Bashi T, Yogev Y et al. Intrapartum fever and the risk for perinatal complications–the effect of fever duration and positive cultures. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2018;31(11):1418–25. 10.1080/14767058.2017.1317740 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Locatelli A, Vergani P, Ghidini A, Assi F, Bonardi C, Pezzullo JC, et al. Duration of labor and risk of cerebral white-matter damage in very preterm infants who are delivered with intrauterine infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3):928–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levin G, Rottenstreich A, Tsur A, Shai D, Cahan T, Yoeli R et al. Determinants of adverse neonatal outcome in vaginal deliveries complicated by suspected intraamniotic infection. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;302(6):1345–52. 10.1007/s00404-020-05717-w [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Li F, Morgan KL, Zaslavsky AM. Balancing covariates via Propensity score weighting. J Am Stat Assoc. 2018;113(521):390–400. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdelraheim AR, Gomaa K, Ibrahim EM, Mohammed MM, Khalifa EM, Youssef AM, et al. Intra-abdominal infection (IAI) following cesarean section: a retrospective study in a tertiary referral hospital in Egypt. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dotters-Katz SK, Feldman C, Puechl A, Grotegut CA, Heine RP. Risk factors for post-operative wound infection in the setting of chorioamnionitis and cesarean delivery. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2016;29(10):1541–5. 10.3109/14767058.2015.1058773 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Kayiga H, Lester F, Amuge PM, Byamugisha J, Autry AM. Impact of mode of delivery on pregnancy outcomes in women with premature rupture of membranes after 28 weeks of gestation in a low-resource setting: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):1–13. 10.1371/journal.pone.0190388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Venkatesh KK, Glover AV, Vladutiu CJ, Stamilio DM. Association of chorioamnionitis and its duration with adverse maternal outcomes by mode of delivery: a cohort study. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;126(6):719–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dexter SC, Malee MP, Pinar H, Hogan JW, Carpenter MW, Vohr BR. Influence of chorioamnionitis on developmental outcome in very low birth weight infants. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(2):267–73. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10432141/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC, Hankins GDV, Connor KD. Term maternal and neonatal complications of acute chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66(1):59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bommarito KM, Gross GA, Willers DM, Fraser VJ, Olsen MA. The Effect of Clinical Chorioamnionitis on Cesarean Delivery in the United States. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(5):1879–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Botet F, Figueras J, Carbonell-Estrany X, Arca G. Effect of maternal clinical chorioamnionitis on neonatal morbidity in very-low birthweight infants: a case-control study. J Perinat Med. 2010;38(3):269–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated and analysed for this study is not publicly available as ethics approval was not obtained for the data to be shared, even in anonymized format.