Abstract

There are increasing concerns regarding the rapid expansion of polystyrene nanoplastics (PS-NPs), which could impact human health. Previous studies have shown that nanoplastics can be transferred from mothers to offspring through the placenta and breast milk, resulting in cognitive deficits in offspring. However, the neurotoxic effects of maternal exposure on offspring and its mechanisms remain unclear. In this study, PS-NPs (50 nm) were gavaged to female rats throughout gestation and lactation to establish an offspring exposure model to study the neurotoxicity and behavioral changes caused by PS-NPs on offspring. Neonatal rat hippocampal neuronal cells were used to investigate the pathways through which NPs induce neurodevelopmental toxicity in offspring rats, using iron inhibitors, autophagy inhibitors, reactive oxygen species (ROS) scroungers, P53 inhibitors, and NCOA4 inhibitors. We found that low PS-NPs dosages can cause ferroptosis in the hippocampus of the offspring, resulting in a decline in the cognitive, learning, and memory abilities of the offspring. PS-NPs induced NOCA4-mediated ferritinophagy and promoted ferroptosis by inciting ROS production to activate P53-mediated ferritinophagy. Furthermore, the levels of the antioxidant factors glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) and glutathione (GSH), responsible for ferroptosis, were reduced. In summary, this study revealed that consumption of PS-NPs during gestation and lactation can cause ferroptosis and damage the hippocampus of offspring. Our results can serve as a basis for further research into the neurodevelopmental effects of nanoplastics in offspring.

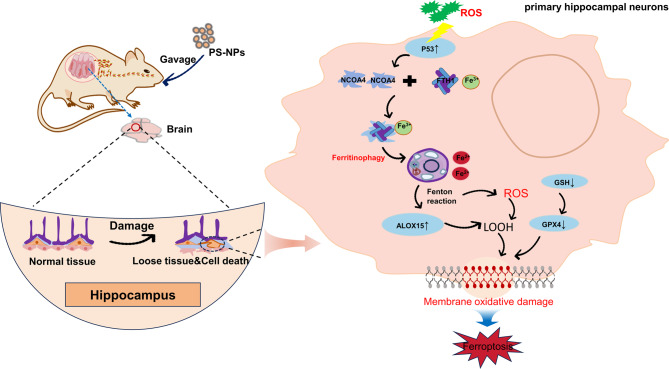

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12951-024-02911-9.

Keywords: Polystyrene nanoplastics, Neurotoxicity, Ferritinophagy, Ferroptosis, Maternal exposure

Introduction

Physical and chemical degradation of plastics in the environment can produce microplastics (< 5 mm) or even nanoplastics (< 1 μm) [1]. Nanoplastics are generated from the degradation of microplastics, and because a single microplastic can be degraded into billions of nanoplastic particles, there are more nanoplastics than microplastics, which explains their current standing as an emerging environmental pollutant [2–4]. Epidemiological studies have found microplastics and nanoplastics in human placenta, blood, and breast milk, indicating a high risk of exposure to nanoplastics and a potential health risk [5–8]. Furthermore, nanoplastics can potentially and irreversibly impact infant development and mental health, even causing developmental delays [9].

Previous studies have suggested that nanoplastics can affect offspring health by accumulating in fish or amphibian spineless creatures and being given to the next generation, causing oxidative damage and metabolism disruption [10, 13]. PS-NPs are the predominant nanoplastics in the natural environment and are used to produce materials such as polystyrene foam, food holders, or cup covers. They enter the human body via ingestion and inhalation [7, 11, 12]. Ding et al. found that PS-NPs decrease acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity and alter P450 metabolizing enzymes in the brain of tilapia [13]. PS-NPs can also cause neurotoxicity by downregulating the expression of nervous system regulators in zebrafish [14]. Furthermore, oral ingestion of PS-NPs during gestation and lactation leads to abnormal neuronal cell function and cognitive deficits in mice offspring [15]. However, there are no in-depth toxicological studies on the mechanisms underlying the neurodevelopmental effects of PS-NPs.

Ferroptosis is a novel mode of programed cell death characterized by the massive accumulation of iron-dependent reactive oxygen species (ROS) [16–18]. Ferroptosis is significantly counteracted by lipid repair systems such as glutathione (GSH) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX4) and is dependent on a series of positively reactive enzymatic reactions [19]. Ferroptosis might be associated with the development, maturation, and aging of the nervous system [20]. Ferritinophagy is a process in which nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4) regulates iron homeostasis by targeting ferritin and promoting its autophagic degradation [21]. Ferritinophagy can contribute to lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress by delivering iron through ferritin degradation and recycling. In neurodegenerative disorders, iron accumulation promotes dopaminergic nerve cell death [22, 23]. The tumor suppressor P53 is a stress-induced transcription factor that regulates cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and senescence [24]. The previous study found that P53 may be involved in both autophagy and ferroptosis [25, 26]. However, the relationship between P53 activation, ferritinophagy, and ferroptosis remains unclear.

Shin et al. found that exposure to PS-NPs induced downregulation of brain developmental genes in offspring, resulting in anxiety, depression, and social behavioral abnormalities [27]. To investigate the underlying mechanism, the present study established a model of PS-NPs exposure during gestation and lactation in female rats to study the relationship between neural damage in offspring and P53 activation mediating ferritinophagy and ferroptosis. Our study provides new insights into the toxicity assessment of nanoplastics.

Methods and materials

Characterization of PS-NPs

PS-NPs were purchased from Beijing Zhongkeleiming Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). PS-NPs morphology was characterized using TEM (FEI Tecnai G2 F30 S -TWIN, USA) and scanning electron microscopy (S-4800, HITACHI). Features were extracted from the TEM images using ImageJ software. Hydrodynamic diameters and zeta potentials were measured in ultrapure water using a Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). The surface groups of PS-NPs were characterized by RTIR spectroscopy (Nicolet6700 FT-IR spectrometer, Nicolet, USA) [28].

Animal models

Healthy pregnant Sprague Dawley (SD)rats (0.5 days after the establishment of vaginal plugs) were purchased from SiPeiFu (Beijing) Biotechnology Co., Ltd. All experimental procedures were approved by the Laboratory Animal Welfare Ethics Committee of the Institute of Environmental and Operational Medicine Academy of Military Sciences (approval number: IACUU of AMMS-04-2022-015). Pregnant rats were sorted according to body weight and randomly divided into two groups (n = 5). Females and males are kept separately at weaning. 6–8 pups per litter were housed in a specific pathogen free animal house with an ambient temperature of 23ºC ± 2ºC, a photoperiod of 12 h light/12 h dark, relative humidity of 40–60%, and a diet meeting laboratory standard. The particle size of the PS-NPs used for our experiments was 50 nm, and the concentration selected for experiments was the minimum dose that would cause effects in the offspring, as previously reported [29]. The PS-NPs group was exposed to PS-NPs (2.5 mg/kg/day) by gavage beginning from the first day of rat gestation until weaning on the 21st day after birth(n = 45); the control group received ultrapure water(n = 45). Brain tissue samples were extracted from 36 offspring rats after the 43rd day of exposure and stored in liquid nitrogen for biochemical analysis (postnatal day 21). The remaining offspring rats were fed normally until puberty (postnatal day 45) when they were subjected to behavioral tests (Fig. 1A).

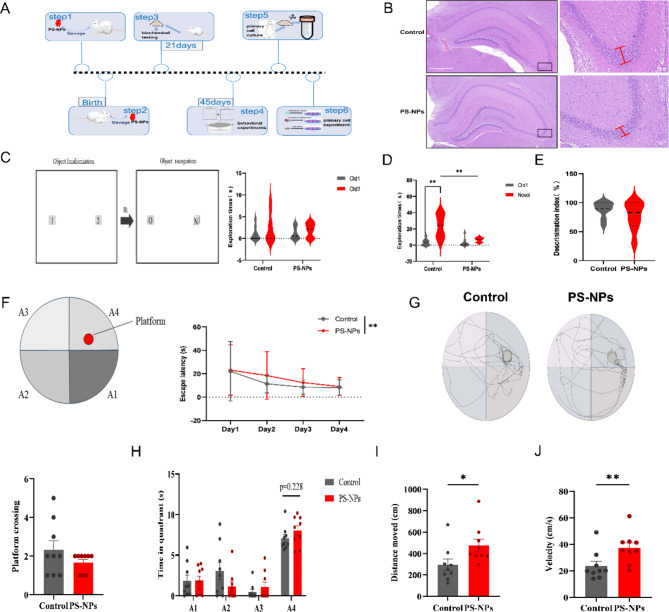

Fig. 1.

Effects of PS-NPs exposure during gestation and lactation on offspring neurodevelopment. (A) Experimental design of this study. (B) H&E staining of hippocampal tissues in offspring rats. Scale bars: 100 μm. (C) Mean total time spent sniffing two similar objects over a 5 min period in a novel object recognition experiment in offspring rats. (D) Mean total time spent exploring novel and familiar objects over a 5 min period. (E) Recognition index, time in contact with novel object/total time in contact with two objects × 100%. (F) Escape latency of offspring rats during the experimental phase of Morris water maze. (G) Trajectories and number of times the offspring mouse traversed the platform. (H) Exploration time in each area during the Morris water maze spatial exploration. (I) Total distance traveled by offspring rats during the probe trial. (J) Speed of offspring rats during the probe trial. n = 9 offspring/group. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

Histopathologic analysis of the hippocampus

After exposure to PS-NPs during gestation and lactation until one day after weaning, the hippocampal region of the brain was removed from the offspring and euthanized by decapitation. The hippocampal tissues of each group were separated, fixed, cut into 4 μm-thick paraffin sections, and stained with H&E. Subsequently, the number and distribution of nerve cells were observed and histopathologically evaluated. High-resolution images were obtained by panoramic scanning.

Novel object recognition test

First, put the rat in the transparent plastic box (60 cm x 40 cm x 22 cm) and move freely for 10 min to get used to the device. Place two similar items (Old 1 and Old 2) in the chest in that order. Give the rat five minutes to explore within the box. After 1 h, replace one of the objects with a new object of similar size but a different shape, and let the rat explore for 5 min. The recognition index (RI) = time of contacting a new object/total time contacting two objects×100%, and the rats’ trajectories were recorded throughout the experiment using the animal behavior video analysis software (SuperMaze, Xinruan, Shanghai).

Morris water maze test

The Morris water maze pool was divided into four quadrants, with 1.5 m diameter stations hidden 2 cm underwater. The experiment was divided into two phases: first, training phase (1 ~ 4 days), followed by probe trial (1 day), to a total of five days. Every rat participated in four trials every day, and the total distance traveled was recorded for each experiment. The rats were placed into the water from each area in front of the pool wall in turn and were allowed to find the platform freely. If the rat did not find the platform within 90 s, the training was ended by manually guiding the rat to the platform and staying there for 15 s, with an interval of 15 min between each training session. On day 5, the platform was removed, and the rat was allowed to explore for 60 s. The time spent in the target quadrant and the number of times the rat traversed the platform, etc., were recorded. Rats’ swimming trajectories were analyzed using the SuperMaze animal behavior video analysis system. (xinruan, shanghai).

Transmission electron microscopy

The brain samples of offspring rats 21 days after birth were fixed with glutaraldehyde, washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in fixative B for 2 h, washed three times with PBS, dehydrated in acetone series, and embedded in resin. Tissue sections were cut into 5 mm-thick sections by cryosectioning (Leica, Berlin) and stained with hydrogen peroxide acetate and lead citrate. The sections were analyzed by TEM (Nikon AIR, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell culture and PS-NPs treatment

Infant rats were cleaned with 75% alcohol, and the skull was dissected to remove the whole brain tissue, which was immersed in a Petri dish containing a precooled PBS solution. The left and right hemispheres were isolated, the hippocampal tissue was carefully excised, and adherent brain tissue and blood vessels were removed; subsequently, the stripped hippocampal tissue was moved to another clean precooled petri dish containing PBS solution and washed gently before being transferred to 2 mL of PBS containing 2% Penicillin–Streptomycin solution (HyClone). The hippocampal tissues were immediately sliced to 1 mm3 using ophthalmic scissors, and trypsin (HyClone) digestion was performed for 10–15 min. The digestion was terminated with an equal amount of serum-containing DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco) and mixed by repeated pipetting until a single-cell suspension. After centrifugation (Lu Xiangyi) at 1000 rotations/min for 5 min, the precipitate was resuspended in inoculation medium (DMEM/F12 containing 10% serum). The cell density was adjusted in an atmosphere in which cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 (Thermo). Cells were replaced to complete half-volume culture on day 2, and the solution was changed every 2 days; after 8 days, the cells were used for experiments.

To evaluate the toxic effects of NPs on the brain hippocampus, primary hippocampal neurons were treated with 0–100 µg/mL of PS-NPs for 72 h. Following the determination of the ideal PS-NP concentration, eight groups of primary hippocampal neurons were randomly assigned to receive PS-NPs in addition to treatments such as the ferroptosis inhibitor (Fer-1), P53 inhibitor (PFT-α), NCOA4 inhibitor (NCOA4-9a), autophagy inhibitor (3-MA), and reactive oxygen scavenger (NAC) were used for specific experiments (Fig. 1A).

Detection of neuron cell death

The offspring rat hippocampal tissue was converted into a single-cell suspension and filtered, and the supernatant was discarded and resuspended in PBS (Solarbio). Primary hippocampal neuronal cells were placed in 6-well plates and incubated for 24 h before exposure to PS-NPs at concentrations of 0–100 µg/mL for 72 h. Cell death in animal tissues and primary cells was assessed using a FITC-labeled recombinant human Annexin V apoptosis test kit (Beyotime) and flow cytometry (Agilent) (BD).

Iron content measurement

Offspring rats hippocampal tissue samples and primary hippocampal neuronal cells were collected, and iron content was determined using iron content assay kits (animal tissue homogenates: Elabscience, cells: Solarbio). The ferrous and total ferrous ions were assayed according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot

Hippocampal tissue homogenates and primary hippocampal neuronal cells were lysed using RIPA lysis solution containing protease inhibitors (Solarbio), and protein extracts were immunoblotted using a specific primary antibody, with anti-mouse (ZB-2305, Affinity) and anti-rabbit secondary antisera (ZB-2301, Affinity), and analyzed using a fully automated chemiluminescent image analysis system for in vivo imaging (Tanon, Shanghai), and Gelpro32 software. The antibodies used for western blotting are shown in Supplemetary Table 1.

Glutathione and lipid peroxidation assay

Intracellular glutathione levels were measured using a Glutathione Assay Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Offspring hippocampal tissues and primary hippocampal cells were used to detect ROS in the hippocampus using a ROS test kit (Nanjing Jiancheng) (Beyotime) and a flow cytometer (NovoCyte 2000, Agilent) (BD FACSCalibur, BD). Primary hippocampal neuronal cells were seeded in confocal dishes and exposed to 25 µg/mL PS-NPs and inhibitors for 72 h. Subsequently, cells were stained with a DCFH-DA probe (Beyotime) and were detected using flow cytometry (BD). Primary hippocampal neuronal cells were used to measure the MDA levels using an MDA test kit (Beyotime).

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

The quality and quantity of total RNA were determined using a Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo), RNA was converted to cRNA using a RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo), and the q-PCR reaction was performed using a Real-Time PCR Instrumentation System (ABI). The relative expression of the target genes was calculated using the 2 − ΔΔCt method. The specific primers are shown in Supplemetary Table 2.

Immunofluorescence assay

Offspring rats’ primary hippocampal cells were extracted, seeded in culture dishes, and exposed to 25 µg/mL PS-NPs, 25 µg/mL PS-NPs + 3-MA, 25 µg/mL PS-NPs + NCOA-1a, and 25 µg/mL PS-NPs + PFT-α for 72 h. Intracellular autophagy proteins and FTH1 were measured using LC3II (Bioss) and FTH1 (Abcam) probes in a working solution incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope (OLYMPUS BX51TRF), and the fluorescence intensity was analyzed using ImageJ software (IPP6.0).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 25 and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (means ± SD). Comparisons between two groups were performed using the unpaired t-test or the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test. Comparisons between multiple groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s or Tamhane’s multiple comparisons, and *p < 0.05 or ** p < 0.01 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Characterization of PS-NPs

The average primary diameter and shape of PS-NPs as analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy was 48.21 ± 0.026 nm, and almost all particles were spherical (Supplementary Fig. 1A-B). Furthermore, the zeta-potential (− 15.9 ± 6.63 MV) indicated that the PS-NPs were slightly negatively charged to facilitate their suspension in ultrapure water (Supplementary Fig. 1 C). Using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to examine the structure of PS-NPs, we observed peaks at 2,922.88, 2850.71, and 1,452.17 cm − 1 corresponding to antisymmetric and symmetric telescoping vibrations and symmetric bending vibrations of methylene (CH2). The stretching vibration of the unsaturated hydrocarbon group on the benzene ring (= CH) peaks at 3,025.93 cm − 1, whereas those at 1,493.04 and 1,601.53 cm − 1 are due to the vibration of the benzene ring backbone (C = C). Finally, the peaks at 698.14 and 756.31 cm − 1 are caused by unsaturated hydrocarbon groups (= C-H) during the out-of-plane variable-angle vibrations of the benzene ring (Supplementary Fig. 1D).

PS-NPs cause damage to the hippocampus of offspring rats

To understand the damage caused by PS-NPs on the hippocampal tissues of offspring rats, Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was used to detect histopathological changes in the hippocampus of offspring rats. We observed neuronal apoptosis, and the hippocampal CA3 area in the PS-NP-exposed group was tightly aligned and disorganized as well as partial neuronal loss, as shown in Fig. 1B. This suggests that nanoplastics are a risk factor for hippocampal damage.

PS-NPs cause behavioral abnormalities in offspring rats

In this study, we performed behavioral experiments in offspring rats at 45 days after birth to investigate the effects of gestational and lactational exposure to PS-NPs on the neurodevelopment of offspring. The results of the new object recognition experiment (Fig. 1 C) did not show significant differences in the time spent exploring the same object during the familiarization period, and rats did not have a preference for the same objects. During the test period, the control group explored the novel object for a significantly longer time than the old; furthermore, there was no significant difference in the time dedicated to the new and old objects in the PS-NPs group (Fig. 1D). In addition, the recognition index indicated no difference in the exploration of old and new objects in the PS-NPs group (Fig. 1E), indicating cognitive decline in offspring rats.

The Morris water maze revealed spatial learning and memory deficits in PS-NPs-exposed offspring rats. During the training phase, the escape latency swam by the PS-NPs group significantly increased (Fig. 1F). On the fifth day of the space exploration experiment, there was a decreasing trend in the number of times the mice in the PS-NPs group traversed the platform and an increase in the time spent marching in the quadrant where the platform was located; however, the difference was not significant (Fig. 1G–H). In addition, mice in the PS-NPs group were significantly more distant and faster than those in the control (Fig. 1I–J).

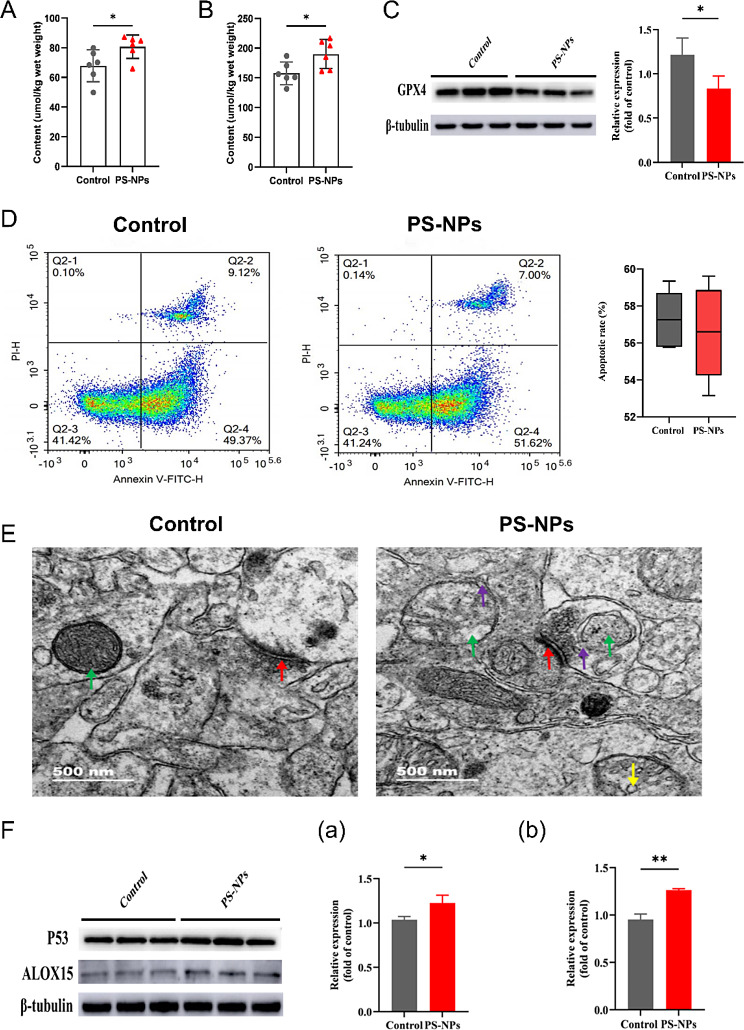

PS-NPs induce ferroptosis in hippocampal regions of offspring rats

Our results showed that PS-NPs induced ferroptosis in the hippocampal tissues of offspring. There was a significant increase in the ferrous and total ferrous ion contents in the PS-NPs-treated group (Fig. 2A–B), along with a significant decrease in the protein expression of GPX4, a marker of ferroptosis (Fig. 2 C). However, apoptosis was not observed (Fig. 2D). TEM analysis revealed that PS-NPs exposure caused mitochondrial defects in hippocampal tissue. We observed partial mitochondrial edema, cristae fracture or disappearance, reduced matrix electron density, and vacuolization, as well as partial rupture of the outer mitochondrial membrane and partial formation of tubular vesicular cristae (Fig. 2E). Western blotting revealed significantly increased expression of the hippocampal tissue ferroptosis-related pathway proteins P53 and ALOX15 (Fig. 2F), indicating that the PS-NPs-related ferroptosis in hippocampal tissues was associated with this pathway.

Fig. 2.

PS-NPs induced ferroptosis in the hippocampal tissues of offspring rats (A) Ferrous ion levels. (B) Total iron ion levels. (C) Expression of GPX4 protein. (D) Degree of apoptosis. (E) Transmission electron microscopy analysis of mitochondria in the hippocampal tissue of offspring rats. Green arrows: number of synaptic vesicles; red arrows: synaptic gap. Green arrows: mitochondrial outer membrane; purple arrows: mitochondrial cristae; red arrows: synaptic gap; yellow arrows: number of synaptic vesicles. Scale bars:500 nm. (F) Expression of ferroptosis-related pathway proteins. (a) P53, (b) ALOX15. Except for n (A-B, D) = 6 offspring, the remaining n = 3 offspring/ group. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

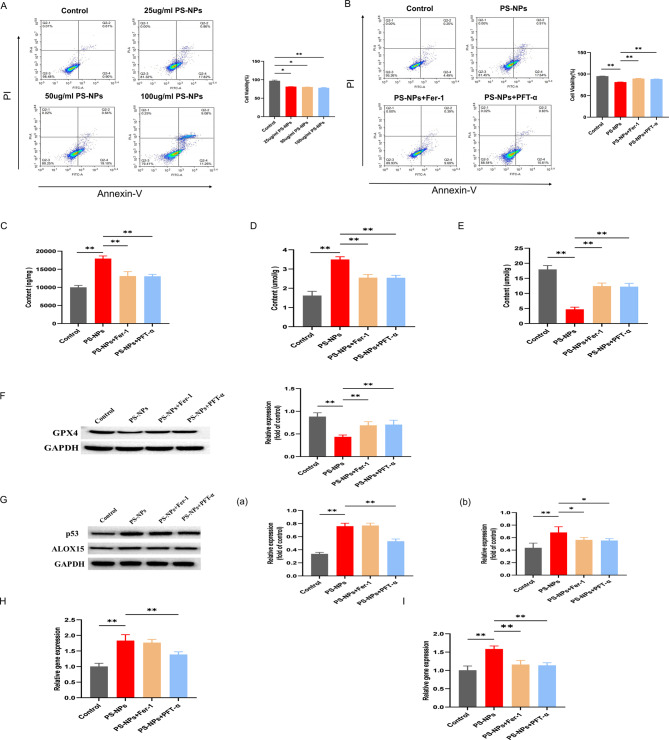

Subsequently, we used primary hippocampal neuronal cells to explore and validate the potential molecular mechanisms underlying ferroptosis in the hippocampal tissues of offspring rats caused by PS-NPs exposure. As shown in Fig. 3A, primary hippocampal neuronal cells died in a dose-dependent manner. The lowest reactive concentration corresponding to that used in the animal experiment was selected for subsequent experiments. In primary hippocampal neuronal cells, the degree of cell death, iron content, and malondialdehyde (MDA) content were significantly higher in the PS-NPs-exposed group (25 µg/mL, 72 h) than in the control group (Fig. 3B–D), whereas GSH and GPX4 levels were significantly lower than in the control group (Fig. 3E-F). In addition, the ferroptosis pathway proteins P53 and ALOX15 were significantly overexpressed, as confirmed by RT-qPCR (Fig. 3G–I). The addition of Fer-1 significantly attenuated PS-NPs-induced neuronal cell death in the primary hippocampus and significantly reduced iron and MDA content (Fig. 3B–D), whereas those of GSH and GPX4 were restored (Fig. 3E–F), indicating that the hippocampal damage induced by exposure to PS-NPs in offspring rats is caused by ferroptosis. The addition of Fer-1 decreased P53 expression and transcript levels in the exposed group, but the differences were not significant (Fig. 3G–H). ALOX15 expression and transcript levels were significantly decreased (Fig. 3G, I). This indicates that ferroptosis caused by exposure to PS-NPs is closely related to P53 and ALOX15, which is consistent with our animal data (Fig. 2F). To clarify the role of P53 in the development of ferroptosis in the nervous system, the addition of the P53 inhibitor, PFT-α, significantly reduced cell death (Fig. 3B), whereas P53 and ALOX15 significantly decreased transcript levels (Fig. 5G–I); other indexes were consistent with the results of Fer-1 (Fig. 3 C–F).

Fig. 3.

PS-NPs induce ferroptosis in primary hippocampal cells. (A) Degree of primary hippocampal cell death at different PS-NPs concentrations. (B) Degree of primary hippocampal cell death after the addition of a ferroptosis inhibitor and P53 inhibitor. (C) Total iron ion levels. (D) MDA levels. (E) GSH levels. (F) Expression of GPX4. (G) Expression of ferroptosis-related pathway proteins: (a) P53, (b) ALOX15. (H) P53 expression analyzed by RT-qPCR. (I) ALOX15 expression analyzed by RT-qPCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

PS-NPs promote ferroptosis via P53-mediated ferritinophagy

Next, we aimed to clarify the mechanism by which exposure to PS-NPs during gestation and lactation causes ferroptosis in the hippocampal region of offspring in rats. Previous experiments showed that together with the significantly higher levels of P53 and ALOX15 ferroptosis-related pathway proteins in the PS-NPs group, the levels of autophagy-associated factors Parkin, Pink1, NCOA4, and LC3II all significantly increased (Fig. 4A). This indicated that PS-NPs induced autophagy in hippocampal tissues. Validation of primary hippocampal neuronal cells revealed significantly higher NCOA4 and LC3II levels in the PS-NPs group than in the control group and high expression of the NCOA4 transcript (Fig. 4B–C). After the addition of the ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1, the protein levels of NCOA4 and LC3II decreased, as did the NCOA4 transcript levels but not significantly. In contrast, the P35 inhibitor PFT-α caused a significant decrease in NCOA4 and LC3II levels and significantly decreased the expression of the NCOA4 transcript (Fig. 4B-C). Thus, both animal and cell studies indicate that P53 induces NCOA4-mediated autophagy.

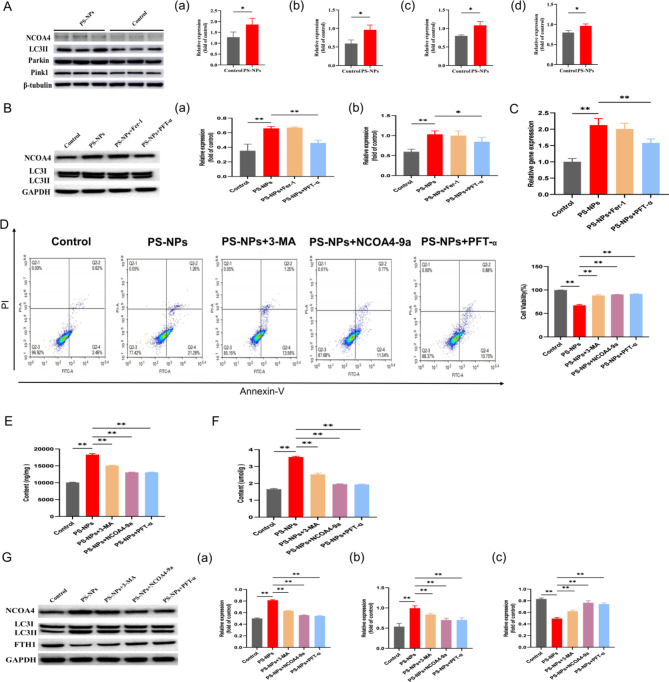

Fig. 4.

PS-NPs induce P53-mediated ferritinophagy to promote ferroptosis. (A) Expression of autophagy-related proteins in hippocampal tissues of offspring rats: (a) NCOA4, (b) LC3II, (c) Parkin, (d) Pink1. (B) Autophagy protein expression in primary hippocampal cells: (a) LC3II, (b) NCOA4. (C) NCOA4 expression analyzed by RT-qPCR. (D) Degree of death of primary hippocampal cells with different inhibitors. (E) Total iron ion content. (F) MDA content. (G) Expression of autophagy-related proteins in primary hippocampal cells: (a) NCOA4, (b) LC3II, (c) FTH1. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

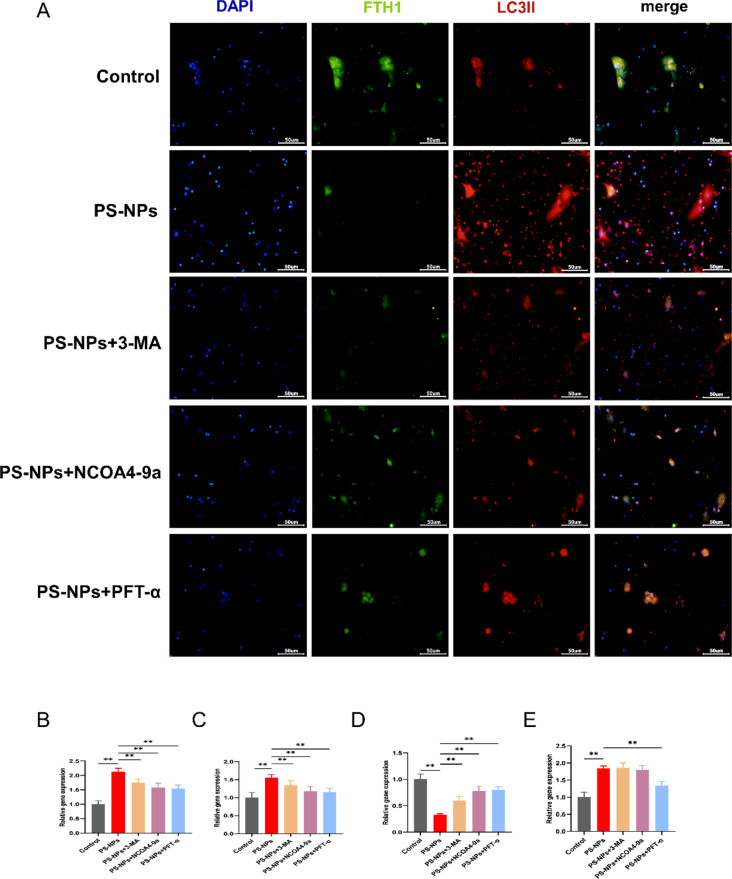

To further determine the relationship between autophagy and ferroptosis induced by PS-NPs, we inhibited PS-NPs-induced cell death in a cell model using 3-MA, NCOA4-9a, and PFT-α (Fig. 4D). Compared with the PS-NPs-exposed group, the ferric ion and MDA content were significantly decreased by all inhibitors (Fig. 4E-F). Western blotting revealed a significant increase in NCOA4 and LC3II protein content and a significant decrease in ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1) content in the PS-NP-exposed group (Fig. 4G). FTH1 is an important component of transferrin that can bind to NCOA4 to release large amounts of iron via ferritinophagy; thus, its reduction indicates that PS-NPs induce ferritinophagy resulting in high iron release. Immunofluorescence colocalization revealed FTH1 colocalized with LC3II in hippocampal neurons; in the inhibitor group, LC3II and NCOA4 decreased significantly, and FTH1 increased significantly (Figs. 4G and 5A). RT-qPCR indicated that the expression of NCOA4, ALOX15, and FTH1 was significantly reduced in the inhibitor group (Fig. 5B-D), whereas that of P53 was significantly decreased only in the PFT-α group (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

(A) Colocalization of FTH1 and LC3II in primary hippocampal cells. FTH1 (green), LC3II (red). Scale bars: 50 μm. (B) NCOA4 expression analyzed by RT-qPCR. (C) ALXO15 expression analyzed by RT-qPCR. (D) FTH1 expression analyzed by RT-qPCR. (E) P53 expression analyzed by RT-qPCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

Scavenging ROS antagonizes PS-NPs-induced ferritinophagy and ferroptosis

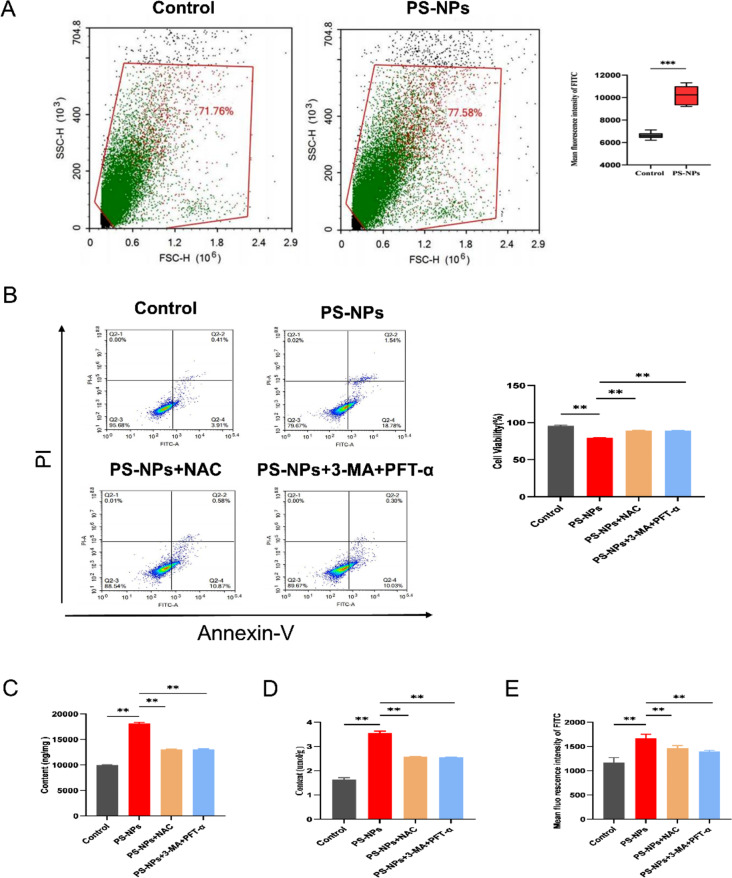

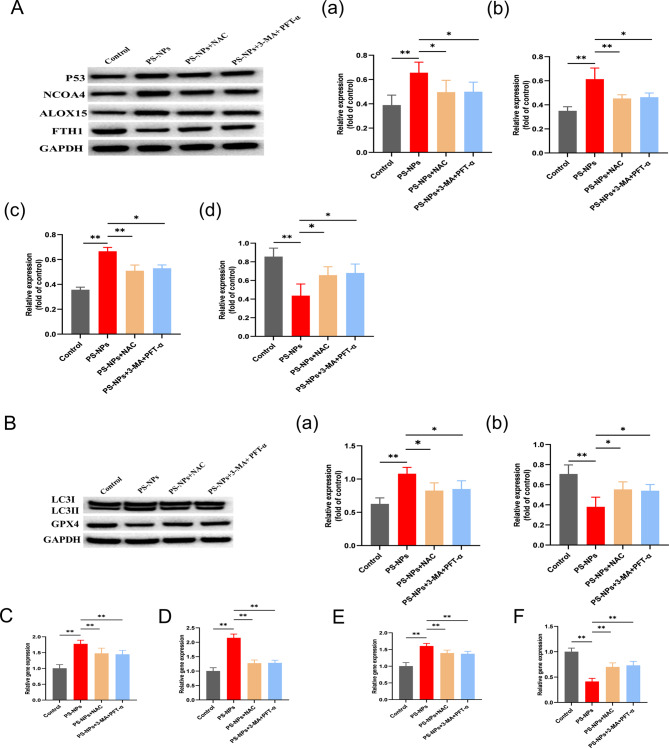

We found significantly elevated ROS levels in the hippocampal tissues of offspring rats (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, research conducted in cell cultures with ROS inhibitors (NAC), autophagy and P53 inhibitors (3-MA + PFT-α) revealed a significant decrease in cellular ferroptosis in the NAC and 3-MA + PFT-α groups (Fig. 6B), as well as significant decreases in the ferric ion concentration and MDA content (Fig. 6 C–D). Flow cytometry revealed a significant decrease in cellular ROS (Fig. 6E). Western blotting and RT-qPCR showed that P53, NCOA4, and ALOX15 expression was significantly decreased and that FTH1 expression was significantly increased in cells supplemented with inhibitors compared with the PS-NPs alone group (Fig. 7A, C-F). In addition, the GPX4 protein content was restored in the inhibitor group, whereas the autophagy protein LC3II was significantly reduced (Fig. 7B). These results indicate that ROS is an upstream factor of P53. Furthermore, blocking ROS production attenuated hippocampal neuron death induced by exposure to PS-NPs, indicating that PS-NPs induce NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy by activating P53 through ROS production, which promotes the massive expression of ALOX15 leading to lipid peroxidation and promoting cellular ferroptosis.

Fig. 6.

Scavenging ROS antagonizes PS-NPs-induced ferritinophagy and ferroptosis. (A) ROS content in hippocampal tissues of offspring rats as detected by flow cytometry. n = 6 offspring/group (B) Cell death after the addition of ROS scavengers and autophagy and P53 inhibitors. (C) Total iron ion content of primary hippocampal cells from offspring rats. (D) MDA content of primary hippocampal cells. (E) ROS content of primary hippocampal cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

Fig. 7.

(A) Expression of ferritinophagy and ferroptosis-related proteins: (a) P53, (b) NCOA4, (c) ALOX15, (d) FTH1. (B) Expression of autophagy-associated proteins and antagonist proteins of ferroptosis: (a) LC3II, (b) GPX4. (C) P53 expression analyzed by RT-qPCR. (D) NCOA4 expression analyzed by RT-qPCR. (E) ALOX15 expression analyzed by RT-qPCR. (F) FTH1 expression analyzed by RT-qPCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

Discussion

Neurodevelopmental disorders caused by environmental pollutants are an important public health concern. PS-NPs can cross the blood–brain barrier and cause neurotoxicity and brain developmental abnormalities after entering the human body [15, 30]. Notably, new evidence indicates that ferroptosis is crucial in nanoplastic-induced neurodevelopmental disorders, but the underlying mechanisms have not yet been elucidated [31]. In this study, we mimicked the nanoplastic environment to which pregnant women are exposed in their daily lives i.e., through gestational and lactational exposure in SD rats and found that i) PS-NPs induced hippocampal tissue damage and neurodevelopmental disorders in the brain of offspring; (ii) exposure to PS-NPs induced ferroptosis and ferritinophagy in the hippocampal region of the offspring; and iii) PS-NPs induced ROS generation in brain tissues to activate P53 to regulate NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy, promoting massive lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Treatment with Fer-1, PFT-α, and NCOA4-9a not only confirmed that PS-NPs produced ferroptosis but also showed how P53, autophagy, and ferroptosis are related in all three. The antioxidants Fer-1 and PFT-α successfully corrected the iron overload that PS-NPs induced, while 3-MA and NCOA4-9a decreased the release of iron ions. Similarly, after treatment with NAC, cell death was slowed down, and iron ion content and lipid peroxidation were reduced. The above results could explain that PS-NPs induced a large accumulation of ROS to activate the occurrence of P53-mediated ferritinophagy, and a large increase in iron ions produced a Fenton reaction leading to lipid peroxidation, which in turn promoted the occurrence of ferroptosis [32, 33]. It is thus clear that ferroptosis is one of the most important ways in which PS-NPs induce hippocampal tissue damage in offspring rats, which have previously focused on oxidative stress and apoptosis, which is similar to the mechanism of nanoplastic-induced lung injury [34, 35]. The present study provides new insights into childhood developmental disorders induced by physical environment-associated PS-NPs via ferroptosis.

Consistent with previous studies reporting that humans ingest 0.1–5 g of micronized plastics per week, we exposed pregnant rats to 2.5 mg/kg/day of PS-NPs [36]. Ragusa et al. discovered particulate polystyrene in the placenta and breast milk, and a study of acute exposure of SD rat lungs to polystyrene nanorods demonstrated NP transfer to the placenta and fetal tissues, and plastic NPs were observed in the fetal brain [37]. Another study found that adults and children in the US ingest between 81,000 and 123,000 MPs of micronized plastics per year, with 5,800 microplastics (MPs)/year from tap water, beer, and sea salt [38, 39]. In this work (2.5 mg/kg/day by gavage, 25 µg/mL exposure), lower PS-NPs converted from environmental concentrations were used to assess neurodevelopmental toxicity in offspring rats. In this study, we revealed the early neurodevelopmental and adverse effects of PS-NPs exposure during gestation and lactation in offspring, such as cognitive memory deficits in offspring.

Ferroptosis, an iron-regulated form of nonapoptotic cell death discovered in recent years, is involved in neurological diseases [40]. Yin et al. found that polystyrene plastic particles promote the onset of cerebellar autophagy, lipid peroxidation of unsaturated fatty acids, ferroptosis, and cerebellar tissue damage [41]. In addition, we found that PS-NPs can cause ferroptosis and nerve damage in mammalian hippocampal tissues. Thus, ferroptosis is important for the induction of neurodevelopmental toxicity in offspring.

Ferritinophagy is crucial in neuronal damage activated by polystyrene nanoplastics [41]. NCOA4, a selective receptor mediating ferritinophagy, regulates ferroptosis and has been studied in cancer, infections, and neurodegenerative and other diseases [42]. p53 is an important component of stress signaling and adaptation and can be activated by various stressors, such as oxidative stress, metabolic stress, and DNA damage. P53 can activate autophagy, leading to neuronal death and the induction of neurodegenerative diseases [25, 43]. However, P53 appears to mediate other cellular functions, such as ferroptosis [26]. In this study, we found that PS-NPs activated P53 by generating large amounts of ROS, inducing NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy, leading to iron overload in the Fenton reaction, and activated ALOX15 to generate lipid peroxidation, which ultimately led to ferroptosis in offspring hippocampal tissues. GPX4 is an important regulator of ferroptosis onset, and it catalyzes the reduction of lipid peroxidation thus inhibiting ferroptosis [44]. GSH is a substrate for GPX4 synthesis necessary for GPX4 functioning [45]. The results of this study showed that PS-NPs induced the production of large amounts of ROS, MDA, and LC3II; activated P53, NOCA4, and ALOX15; and decreased GPX4, GSH, and FTH1 levels in treated rat offspring. Similar to Wu’s results, the addition of Fer-1 and PFT-α reversed these results [46].

Furthermore, we identified a mechanism by which exposure to PS-NPs activates ferroptosis by ROS-activated P53 leading to the onset of ferritinophagy, which generates a Fenton reaction leading to redox toxicity production characterized by a marked decrease in GPX4 expression, inhibition of GSH synthesis, and elevated levels of lipid peroxidation. These findings emphasize the importance of this mechanism in the neurodevelopmental effects of PS-NPs in offspring. Studies on the mechanisms of toxicity during the early stages of neurodevelopment in offspring are essential to prevent and treat these ill effects. Overall, our study provides new therapeutic targets for the prevention of neurodevelopmental disorders in children caused by environmental factors. We also recognize the limitations of this study. On the one hand, we did not classify the offspring as male or female, so it is unknown as to whether sex specificity exists. On the other hand, for the detection of memory impairment in offspring, only the Morris water maze experiment was performed.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to all the people who have ever helped me with this paper.

Author contributions

Bencheng Lin and Lei Tian contributed to the design and supervision of this study. Jiang Chen designed the experiments, carried out all the experiments, analyzed the original data, and wrote the original draft. Licheng Yan, Yaping Zhang, Xuan Liu, Yizhe Wei, Yiming Zhao, Kang Li, Yue Shi, Huanliang Liu, and Wenqing Lai analyzed the partial data and made the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study and its included experimental procedures were approved by the Laboratory Animal Welfare Ethics Committee of the Institute of Environmental and Operational Medicine Academy of Military Sciences (approval number: IACUU of AMMS-04-2022-015). All animal housing and experiments were conducted in strict accordance with the institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from the participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Lei Tian, Email: tjtianlei@126.com.

Bencheng Lin, Email: linbencheng123@126.com.

References

- 1.Issac MN, Kandasubramanian B. Effect of microplastics in water and aquatic systems. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28:19544–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halle AT, Jeanneau L, Martignac M, Jardé E, Pedrono B, Brach L, Gigault J. Nanoplastic in the north atlantic subtropical gyre. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51:13689–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Facciolà A, Visalli G, Ciarello MP, Di Pietro A. Newly emerging airborne pollutants: current knowledge of health impact of micro and nanoplastics. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang S, Zhang T, Ge Y, Cheng Y, Yin L, Pu Y, Chen Z, Liang G. Ferritinophagy mediated by oxidative stress-driven mitochondrial damage is involved in the polystyrene nanoparticles-induced ferroptosis of lung injury. ACS Nano. 2023;12:acsnano.3c07255. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Ragusa A, Svelato A, Santacroce C, Catalano P, Notarstefano V, Carnevali O, Papa F, Rongioletti MCA, Baiocco F, Draghi S, D’Amore E, Rinaldo D, Matta M, Giorgini E. Plasticenta: first evidence of microplastics in human placenta. Environ Int. 2021;146:106274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leslie HA, van Velzen MJM, Brandsma SH, Vethaak AD, Garcia-Vallejo JJ, Lamoree MH. Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood. Environ Int. 2022;163:107199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ragusa A, Notarstefano V, Svelato A, Belloni A, Gioacchini G, Blondeel C, Zucchelli E, De Luca C, D’Avin S, Gulotta A, Carnevali O. Giorgini. Raman Microspectroscopy Detection and Characterisation of Microplastics in Human Breastmilk. Polymers. 2022;14:2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Weng H, Liu S, Li F, Xu K, Wen S, Chen X, Li C, Nie Y, Liao B, Wu J, Kantawong F, Xie X, Yu F, Li G. Embryonic exposure of polystyrene nanoplastics affects cardiac development. Sci Total Environ. 2024;906:167406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trentacosta CJ, Davis-Kean P, Mitchell C, Hyde L. Dolinoy. Environmental contaminants and Child Development. Child Dev Perspect. 2016;10:228–33. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou R, Lu G, Yan Z, Jiang R, Bao X, Lu P. A review of the influences of microplastics on toxicity and transgenerational effects of pharmaceutical and personal care products in aquatic environment. Sci Total Environ. 2020;732:139222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang J, Bu W, Hu W, Zhao Z, Liu L, Luo C, Wang R, Fan S, Yu S, Wu Q, Wang X, Zhao X. Ferroptosis is involved in sex-specific small intestinal toxicity in the offspring of adult mice exposed to polystyrene nanoplastics during pregnancy. ACS Nano. 2023;17:2440–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kik K, Bukowska B, Sicińska P. Polystyrene nanoparticles: sources, occurrence in the environment, distribution in tissues, accumulation and toxicity to various organisms. Environ Pollut. 2020;262:114297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding J, Zhang S, Razanajatovo RM, Zou H, Zhu W. Accumulation, tissue distribution, and biochemical effects of polystyrene microplastics in the freshwater fish red tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus). Environ Pollut. 2018;238:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Che Q, Gundlach M, Yang S, Jiang J, Velki M, Yin D, Hollert H. Quantitative investigation of the mechanisms of microplastics and nanoplastics toward zebrafish larvae locomotor activity. Sci Total Environ. 2017;584–5, 1022–1031. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Jeong B, Baek JY, Koo J, Park S, Ryu Y-K, Kim K-S, Zhang S, Chung C, Dogan R, Choi H-S, Um D, Kim T-K, Lee WS, Jeong J, Shin W-H, Lee J-R, Kim N-S, Lee DY. Maternal exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics causes brain abnormalities in progeny. J Hazard Mater. 2022;426:127815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao JY, Dixon SJ. Mechanisms of ferroptosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:2195–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, Yu C, Kang R, Tang D. Iron metabolism in ferroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biology. 2020;8:590226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS, Morrison III B, Stockwell BR. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149:1060–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stockwell BR, Angeli JPF, Bayir H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascon S, Hatzios SK, Kagan VE, Noel K, Jiang X, Linkermann A, Murphy ME, Overholtzer M, Oyagi A, Pagnussat GC, Park J, Ran Q, Rosenfeld CS, Salnikow K, Tang D, Torti FM, Torti SV, Toyokuni S, Woerpel KA, Zhang DD. Ferroptosis: a regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 2017;171:273–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou Y, Lin W, Rao T, Zheng J, Zhang T, Zhang M, Lin Z. Ferroptosis and its potential role in the nervous system diseases. J Inflamm Res Volume. 2022;15:1555–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mancias JD, Wang X, Gygi SP, Harper JW, Kimmelman AC. Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature. 2014;509:105–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee S, Hwang N, Seok BG, Lee S, Lee S-J, Chung SW. Autophagy mediates an amplification loop during ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Jenner P, Dexter DT, Sian J, Schapira AHV. Marsden. Oxidative stress as a cause of nigral cell death in Parkinson’s disease and incidental lewy body disease. Ann Neurol. 1992;32:S82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine AJ, Oren M. The first 30 years of P53: growing ever more complex. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:749–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X-D, Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhang X, Han R, Wu J-C, Liang Z-Q, Gu Z-L, Han F, Fukunaga K, Qin Z-H. P53 mediates mitochondria dysfunction-triggered autophagy activation and cell death in rat striatum. Autophagy. 2009;5:339–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, Wang S-J, Su T, Hibshoosh H, Baer R, Gu W. Ferroptosis as a P53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 2015;520:57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin HS, Lee SH, Moon HJ, So YH, Lee HR, Lee E-H, Jung E-M. Exposure to polystyrene particles causes anxiety-, depression-like behavior and abnormal social behavior in mice. J Hazard Mater. 2023;454:131465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Errázuriz León R, Araya Salcedo VA, Novoa San Miguel FJ, Llanquinao Tardio CRA, Tobar Briceño AA, Cherubini Fouilloux SF, de Matos Barbosa M, Barros CASaldías, Waldman WR, Espinosa-Bustos C, Hornos Carneiro MF. Photoaged polystyrene nanoplastics exposure results in reproductive toxicity due to oxidative damage in caenorhabditis elegans. Environ Pollut. 2024;348:123816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ya-ping Z, Lei T, Xiao-qian X, Ya-ting W, Peng L, Zhu-ge X. Effects of nanopolystyrene nanoplastic exposure on the development and neurotoxicity of fetal rats during gestation. Chin J Appl Physiol. 2022;38:760–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X, Zhao Y, Dou J, Hou Q, Cheng J, Jiang X. Bioeffects of inhaled nanoplastics on neurons and alteration of animal behaviors through deposition in the brain. Nano Lett. 2022;22:1091–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Z, Bi Y, Li K, Song Z, Pan C, Zhang S, Lan X, Foulkes NS, Zhao H. Nickel oxide nanoparticles induce developmental neurotoxicity in zebrafish by triggering both apoptosis and ferroptosis. Environ Science: Nano. 2023;10:640–55. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie Y, Hou W, Song X, Yu Y, Huang J, Sun X, Kang R, Tang D. Ferroptosis: process and function. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23(3):369–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Tang M. PM2.5 induces ferroptosis in human endothelial cells through iron overload and redox imbalance. Environ Pollut. 2019;254(Pt A):112937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Q, Cao Y, Li H, Liu H, Liu Y, Bi L, Zhao H, Jin L, Peng R. Sodium nitroprusside alleviates nanoplastics-induced developmental toxicity by suppressing apoptosis, ferroptosis and inflammation. J Environ Manage. 2023;345:118702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang S, Zhang T, Ge Y, Cheng Y, Yin L, Pu Y, Chen Z, Liang G. Ferritinophagy mediated by oxidative stress-driven mitochondrial damage is involved in the polystyrene nanoparticles-induced ferroptosis of lung injury[J]. ACS Nano. 2023;acsnano.3c07255. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Senathirajah K, Attwood S, Bhagwat G, Carbery M, Wilson S, Palanisami T. Estimation of the mass of microplastics ingested – a pivotal first step towards human health risk assessment. J Hazard Mater. 2021;404:124004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fournier SB, D’Errico JN, Adler DS, Kollontzi S, Goedken MJ, Fabris L, Yurkow EJ, Stapleton PA. Nanopolystyrene translocation and fetal deposition after acute lung exposure during late-stage pregnancy. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2020;17:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox KD, Covernton GA, Davies HL, Dower JF, Juanes F, Dudas SE. Human consumption of microplastics. Environ Sci Technol. 2019;53:7068–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kosuth M, Mason SA, Wattenberg EV. Anthropogenic contamination of tap water, beer, and sea salt. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0194970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiland A, Wang Y, Wu W, Lan X, Han X, Li Q, Wang J. Ferroptosis and its role in diverse brain diseases. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56:4880–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yin K, Wang D, Zhao H, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Li B, Xing M. Polystyrene microplastics up-regulates liver glutamine and glutamate synthesis and promotes autophagy-dependent ferroptosis and apoptosis in the cerebellum through the liver-brain axis. Environ Pollut. 2022;307:119449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santana-Codina N, Mancias J. The role of NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy in health and disease. Pharmaceuticals. 2018;11:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White E. Autophagy and p53. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Med. 2016;6:a026120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, Cheah JH, Clemons PA, Shamji AF, Clish CB, Brown LM, Girotti AW, Cornish VW, Schreiber SL, Stockwell BR. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156:317–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song X, Long D. Nrf2 and ferroptosis: a New Research Direction for neurodegenerative diseases. Front NeuroSci. 2020;14:267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu Y, Wang J, Zhao T, Sun M, Xu M, Che S, Pan Z, Wu C, Shen L. Polystyrenenanoplastics lead to ferroptosis in the lungs. J Adv Res. 2024;56:31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.