Abstract

Objectives

Sleep characteristics such as duration, continuity, and irregularity are associated with the risk of hypertension. This study aimed to investigate the association between sleep timing (including bedtime, wake-up time, and sleep midpoint) and the prevalence of hypertension.

Methods

Participants were selected from the Sleep Heart Health Study (n = 5504). Bedtime and wake-up times were assessed using sleep habit questionnaires. The sleep midpoint was calculated as the halfway point between the bedtime and wake-up time. Restricted cubic splines and logistic regression analyses were performed to explore the association between sleep timing and hypertension.

Results

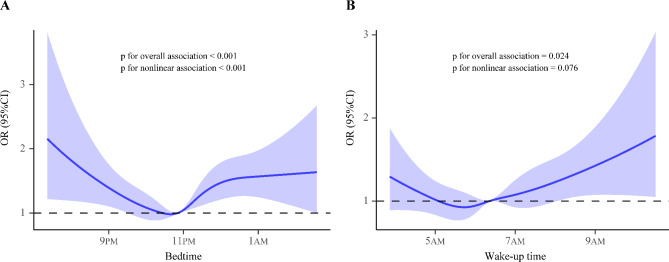

A significant nonlinear association was observed between bedtime (Poverall<0.001; Pnonlinear<0.001), wake-up time (Poverall=0.024; Pnonlinear=0.076), sleep midpoint (Poverall=0.002; Pnonlinear=0.005), and the prevalence of hypertension after adjusting for potential confounders. Multivariable logistic regression showed that both late (> 12:00AM and 23:01PM to 12:00AM) and early (≤ 22:00PM) bedtimes were associated with an increased risk of hypertension compared to bedtimes between 22:01PM and 23:00PM. In addition, individuals with late (> 7:00AM) and early (≤ 5:00AM) wake-up times had a higher prevalence of hypertension than those with wake-up times ranging between 5:01AM and 6:00AM. Delaying the sleep midpoint (> 3:00AM) was also associated with an increased risk of hypertension. Furthermore, no significant interaction effect was found in the subgroup analyses stratified by age, sex, or apnea-hypopnea index.

Conclusions

Our findings identified a nonlinear association between sleep timing and hypertension. Individuals with both early and late sleep timing had a high prevalence of hypertension.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12888-024-06174-4.

Keywords: Bedtime, Wake-up time, Sleep midpoint, Hypertension, Sleep heart health study

Introduction

Hypertension is a common condition worldwide characterized by increased blood pressure (BP) [1]. The main causes of hypertension include eating patterns, smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, kidney disease, and medication use [2]. About 1.28 billion adults between the ages of 30–79 have hypertension worldwide. Approximately 21% of patients with hypertension have their BP under control [3]. The prevention and management of hypertension are of great significance for improving quality of life and reducing the social burden [4].

An increasing number of observational studies have demonstrated the close association between sleep and hypertension [5]. Sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea and sleep fragmentation are associated with the prevalence of hypertension [6, 7]. In addition, individuals with short sleep durations have an increased risk of hypertension [8]. Bedtime and wake-up times are important parameters for sleep timing, which determined the sleep duration of the population. Sleep midpoint, halfway point of the bedtime and wake-up times, was found to be associated with BP [9]. Previous studies showed that bedtime influenced nocturnal blood pressure in adolescents and adults [10, 11]. In addition, a U-shaped relationship was observed between bedtime and hypertension based on histogram, but non-linear analysis was not performed in these studies.

This study aimed to investigate the association between sleep timing, including bedtime, wake-up time, and sleep midpoint, and the prevalence of hypertension in middle-aged and older populations. Moreover, we suggest covariates such as age, sex and sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) may be confounders in the association between sleep timings and hypertension. Therefore, we performed subgroup analysis stratified by age, sex and SDB in the present study.

Methods

Study population

All individuals enrolled in this study were part of the Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS). The SHHS was a multicenter, community-based study, and subjects were recruited from nine existing epidemiological studies (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00005275). In the SHHS, each participant underwent an overnight polysomnography and completed a sleep habit questionnaire. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each site. Details of the study design and quality control procedures have been previously reported [12, 13]. Supplementary Figure S1 shows a flowchart of the participant selection. In the present study, individuals were excluded if they had (1) missing data on bedtime and wake-up time (n = 168) or (2) were shift workers (n = 132). Finally, 5504 participants were included in the analysis.

Sleep timing

Sleep timing was based on sleep habit question “What time do you usually fall asleep and wake-up on weekdays and weekend (hour, minute, AM or PM)?” Bedtime and wake-up time used for the main analysis were defined as the average of weekday and weekend. The sleep midpoint was calculated as the halfway point between the bedtime and wake-up time. Shift workers were defined as having bedtime between 4:00AM and 6:00PM or wake-up time between 12:00PM and 4:00AM. Sleep timing including bedtime, wake-up time and sleep midpoint were further grouped according to previous studies and important time points such as midnight (12:00AM) [14–17]. Bedtime was divided into four groups: ≤10:00PM, 10:01PM–11:00AM, 11:01PM–12:00AM and > 12:00AM. Wake-up times were categorized as ≤5:00AM, 5:01AM–6:00AM, 6:01AM–7:00AM and > 7:00AM. The sleep midpoint was further divided into ≤2:00AM, 2:01AM–3:00AM, 3:01AM–4:00AM and > 4:00AM.

Hypertension

In the SHHS, systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) were measured in a seated position after resting for 5 min. The observer recorded the BP using a Littman stethoscope. The average of two measurements was used to describe blood pressure. Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg, or receiving antihypertensive treatment (mainly included angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, Beta-blockers, calcium-channel blocker, diuretic and vasodilators).

Covariates

Information on age, sex, race, smoking status, coffee use, alcohol consumption, body mass index (BMI), diabetes presence, total cholesterol levels, and triglyceride levels were collected at baseline. Sleep duration was calculated as the period between bedtime and wake-up time. The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was defined as all episodes of apnea and hypopnea per hour of sleep accompanied by at least 4% oxygen desaturation. AHI was classified as no SDB (AHI<5 events/h), mild SDB (AHI ≥ 5 to <15 events/h), moderate SDB (AHI ≥ 15 to <30 events/h), and severe SDB (AHI ≥ 30 events/h).

Statistical analyses

The baseline characteristics of participants with and without hypertension were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and number (percentage) for categorical variables. The nonlinear association between sleep times (bedtime, wake-up time, and sleep midpoint) and hypertension was analyzed using a restricted cubic spline logistic regression model. The model was adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking status, coffee use, alcohol consumption, BMI, diabetes presence, AHI, total cholesterol level, triglyceride level, and sleep duration. Based on the results of restricted cubic spline analysis, we selected the sleep timing category group corresponding to the lowest odds ratio (OR) of hypertension as reference. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate the cross-sectional association between the different sleep timing categories and the prevalence of hypertension. We further examined this association in individuals with and without SDB. We also conducted subgroup analyses stratified by age (≥ 60 vs. <60 years), sex (men vs. women), and AHI level (≥ 15 vs. <15 events/h). Furthermore, we also explored the relationship between sleep timing on weekday and weekend and the prevalence of hypertension. SPSS software (version 24.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R software (version 3.6.3; R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) were used for the data analyses.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 1 shows the 5504 participant characteristics (mean age with 63.2 ± 11.2 years; 2882 women [52.4%]). Individuals with hypertension were older and had higher BMI, total cholesterol, and triglyceride levels than controls. In addition, hypertensive patients were more likely to be men and have SDB. Sleep timing, including bedtime, wake-up time, and sleep midpoint, was generally delayed in patients with hypertension.

Table 1.

The characteristics in participants with and without hypertension

| Variables | Total (n = 5504) |

Hypertension (n = 2778) |

Control (n = 2726) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.2 ± 11.2 | 66.5 ± 10.6 | 59.8 ± 10.8 | < 0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.037 | |||

| Men | 2622 (47.6) | 1362 (49.0) | 1260 (46.2) | ― |

| Women | 2882 (52.4) | 1416 (51.0) | 1466 (53.8) | ― |

| Race, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| White | 4691 (85.2) | 2363 (85.1) | 2328 (85.4) | ― |

| Black | 454 (8.3) | 287 (10.3) | 167 (6.1) | ― |

| Other | 359 (6.5) | 128 (4.6) | 231 (8.5) | ― |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.1 ± 5.1 | 28.8 ± 5.4 | 27.5 ± 4.6 | < 0.001 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Current smoker | 513 (9.4) | 201 (7.3) | 312 (11.5) | ― |

| Former smoker | 2381 (43.5) | 1242 (45.0) | 1139 (42.1) | ― |

| Never smoker | 2575 (47.1) | 1319 (47.7) | 1256 (46.4) | ― |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| At least 1 drink per day | 2316 (45.4) | 1109 (42.9) | 1207 (48.0) | ― |

| None | 2786 (54.6) | 1478 (57.1) | 1308 (52.0) | ― |

| Coffee use, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| At least 1 drink per day | 3306 (60.4) | 1565 (56.7) | 1741 (64.2) | ― |

| None | 2164 (39.6) | 1195 (43.3) | 969 (35.8) | ― |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 380 (6.9) | 293 (10.5) | 87 (3.2) | < 0.001 |

| AHI, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| ≥30.0, events/hour | 404 (7.4) | 270 (9.7) | 134 (4.9) | ― |

| 15.0-29.9, events/hour | 756 (13.7) | 445 (16.0) | 311 (11.4) | ― |

| 5.0-14.9, events/hour | 1659 (30.1) | 897 (32.3) | 762 (28.0) | ― |

| <5.0, events/hour | 2685 (48.8) | 1166 (42.0) | 1519 (55.7) | ― |

| Sleep timing | ||||

| Bedtime, PM | 11.1 ± 1.1 | 11.1 ± 1.1 | 11.0 ± 1.0 | 0.004 |

| Wake-up time, AM | 6.5 ± 1.1 | 6.6 ± 1.1 | 6.5 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 |

| Sleep midpoint, AM | 2.8 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | < 0.001 |

| Sleep duration, n (%) | 7.5 ± 1.1 | 7.5 ± 1.2 | 7.5 ± 1.0 | 0.050 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 207.5 ± 38.7 | 209.2 ± 38.6 | 205.7 ± 38.7 | 0.001 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dl | 150.1 ± 100.5 | 159.6 ± 97.0 | 140.2 ± 103.1 | < 0.001 |

AHI, apnea hypopnea index; Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%)

The P values represent the difference between 2 groups

Sleep timing and hypertension

In the restricted cubic spline analysis, we found a nonlinear association between bedtime and the prevalence of hypertension (Poverall<0.001; Pnonlinear<0.001) after adjusting for potential confounders. Both late and early bedtimes increased the prevalence of hypertension (Fig. 1A). A similar association was found between the sleep midpoint and hypertension (Poverall=0.002; Pnonlinear=0.005) (Fig. 2). There was a nonlinear association between wake-up time and hypertension (Poverall=0.024; Pnonlinear=0.076). Only a delayed wake-up time showed an obvious upward trend in the prevalence of hypertension (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are shown for the nonlinear association between bedtimes, wake-up times, and hypertension risk. The analyses were adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking status, coffee use, alcohol consumption, body mass index, diabetes presence, apnea hypopnea index, total cholesterol level, triglyceride level, and sleep duration. (A) Bedtime and hypertension; (B) Wake-up time and hypertension

Fig. 2.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are shown for the nonlinear association between sleep midpoints and hypertension risk. The analyses were adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking status, coffee use, alcohol consumption, body mass index, diabetes presence, apnea hypopnea index, total cholesterol level, triglyceride level, and sleep duration

The association between different sleep time categories and hypertension was further explored (Table 2). Multivariate logistic regression showed that individuals with bedtimes > 12:00AM (OR 1.52, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.23–1.89; P < 0.001), 23:01PM to 12:00AM (OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.09–1.48; P = 0.002) and ≤ 22:00PM (OR 1.24, 95% CI 1.03–1.49; P = 0.024) had higher prevalence of hypertension than those with bedtimes between 22:01PM and 23:00PM (reference). Moreover, wake-up times > 7:00AM (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.08–1.55; P = 0.006) and ≤ 5:00AM (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.00–1.63; P = 0.049) were associated with an increased risk of hypertension compared with a wake-up time between 5:01AM and 6:00AM (reference group). Compared with 2:01AM to 3:00AM, sleep midpoints > 4:00AM and 3:01AM to 4:00AM were associated with a 39% (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.10–1.76; P = 0.006) and 22% (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.06–1.42; P = 0.008) increase in hypertension prevalence.

Table 2.

ORs and 95% CIs for sleep timing (bedtime, wake-up time, sleep midpoint) associated with prevalence of hypertension

| No. of subjects, n | Events, n (%) | Univariate Models | Age and sex adjusted | Multivariable adjusteda | Multivariable adjustedb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep timing | OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | ||

| Bedtime | ||||||||||

| > 12:00AM | 678 | 387 (57.1) |

1.57 (1.32–1.87) |

< 0.001 |

1.51 (1.26–1.81) |

< 0.001 |

1.41 (1.15–1.73) |

0.001 |

1.52 (1.23–1.89) |

< 0.001 |

| 23:01PM-12:00AM | 1820 | 941 (51.7) |

1.26 (1.11–1.44) |

< 0.001 |

1.23 (1.08–1.40) |

0.002 |

1.23 (1.06–1.43) |

0.006 |

1.27 (1.09–1.48) |

0.002 |

| 22:01PM-23:00PM | 1997 | 916 (45.9) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≤ 22:00PM | 1009 | 534 (52.9) |

1.33 (1.14–1.54) |

< 0.001 |

1.26 (1.08–1.48) |

0.003 |

1.31 (1.10–1.57) |

0.003 |

1.24 (1.03–1.49) |

0.024 |

| Wake-up time | ||||||||||

| > 7:00AM | 1421 | 791 (55.7) |

1.44 (1.24–1.66) |

< 0.001 |

1.32 (1.14–1.54) |

< 0.001 |

1.34 (1.13–1.58) |

0.001 |

1.29 (1.08–1.55) |

0.006 |

| 6:01AM-7:00AM | 2022 | 989 (48.9) |

1.10 (0.96–1.25) |

0.175 |

1.06 (0.92–1.21) |

0.426 |

1.09 (0.93–1.27) |

0.283 |

1.07 (0.92–1.26) |

0.373 |

| 5:01AM-6:00AM | 1555 | 725 (46.6) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≤ 5:00AM | 506 | 273 (54.0) |

1.34 (1.10–1.64) |

0.004 |

1.26 (1.02–1.55) |

0.029 |

1.25 (0.99–1.59) |

0.066 |

1.28 (1.00-1.63) |

0.049 |

| Sleep midpoint | ||||||||||

| > 4:00AM | 462 | 277 (60.0) |

1.71 (1.40–2.09) |

< 0.001 |

1.56 (1.26–1.92) |

< 0.001 |

1.40 (1.11–1.77) |

0.005 |

1.39 (1.10–1.76) |

0.006 |

| 3:01AM-4:00AM | 1546 | 835 (54.0) |

1.34 (1.18–1.52) |

< 0.001 |

1.28 (1.12–1.46) |

< 0.001 |

1.23 (1.06–1.43) |

0.006 |

1.22 (1.06–1.42) |

0.008 |

| 2:01AM-3:00AM | 2389 | 1116 (46.7) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≤ 2:00AM | 1107 | 550 (49.7) |

1.13 (0.98–1.30) |

0.102 |

1.13 (0.98–1.32) |

0.096 |

1.10 (0.93–1.30) |

0.276 |

1.09 (0.92–1.29) |

0.312 |

AHI, apnea hypopnea index; BMI, body mass index; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio

a adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking status, coffee use, alcohol use, BMI, diabetes, AHI, total cholesterol, triglyceride

b adjusted for a + sleep duration

Subgroup analyses

The relationship between sleep timing and hypertension was tested in participants with and without SDB. A bedtime between 23:01PM and 12:00AM was associated with a higher prevalence of hypertension in both the SDB and control groups. There were no significant interactions between bedtime (Pinteraction=0.928), wake-up time (Pinteraction=0.713), sleep midpoint (Pinteraction=0.619), and SDB (Supplementary Table S1). In addition, we performed subgroup analyses stratified by age (≥ 60 vs. <60 years), sex (men vs. women), and AHI level (≥ 15 vs. <15 events/h). No interaction effects were found in these analyses (Supplementary Tables S2-S4).

Sleep timing on weekday and weekend and hypertension

To provide more information about the relationship between sleep timing and hypertension, we also explored the association between sleep timing and hypertension separately for weekdays and weekends. Our results showed that sleep timing on both weekday and weekend were associated with high prevalence of hypertension (Supplementary Tables S5-S6).

Discussion

In this community-based study, we established a nonlinear association between bedtime and hypertension. Both early and late bedtimes were associated with an increased prevalence of hypertension. A similar association was observed for wake-up time and sleep midpoint. This association was even more pronounced for delayed sleep times, especially in patients with a bedtime > 12:00AM, wake-up time > 7:00AM, and sleep midpoint > 4:00AM.

Reasonable sleep timing is an important aspect of a healthy sleep pattern [18]. Observational studies have shown that late sleepers tend to consume more calories, gain more weight, and exhibit impaired glucose tolerance [19–22]. Bedtime was also associated with nocturnal BP. Jansen et al. found that adolescents with weekday bedtimes between ≥ 12:00AM and < 9AM had a higher risk of elevated BP [11]. In adults, a U-shaped relationship was observed between bedtime and SBP, with the lowest SBP occurring with a bedtime of 12:00AM [10]. In addition, Abbott et al. showed that delaying the midpoint of sleep is associated with SBP and DBP [9]. In the present study, we used a restricted cubic spline to investigate whether there was a nonlinear association between sleep timing and hypertension. Our results demonstrated that both early and late sleep times (including bedtime, wake-up time, and sleep midpoint) were associated with a high prevalence of hypertension. Bedtimes between 10:01PM–11:00PM, wake-up times from 5:01AM to 6:00AM and sleep midpoints from 2:01AM to 3:00AM were the nadir for the hypertension risk. Our findings support the importance of appropriate sleep timing for reducing the prevalence of hypertension.

SDB is a common sleep disorder that leads to snoring and oxygen desaturation [23]. Individuals with normal sleep patterns had an AHI of less than 5 events per hour [24]. In addition, an AHI of 15 events per hour is an important node in clinical research [25, 26]. Previous studies showed a strong association between SDB and hypertension [6, 27]. In this study, we did not find significant differences in the subgroup analysis stratified by SDB (yes vs. no) or AHI level (≥ 15 vs. <15 events/h). The association between sleep timing and hypertension may not be affected by the AHI.

Several mechanisms may explain the association between sleep timing and hypertension. A growing body of evidence has shown that circadian rhythm including BP and sleep-wake cycle are strongly influenced by the molecular circadian clock [28]. Early or late bedtime may affect sleep-wake cycle and lead to circadian dysregulation, which could further affect circadian BP rhythms [29, 30]. Individuals with delayed sleep timing tended to experience shorter sleep duration and more light exposure, which may influence the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems [31, 32]. In addition, reduced parasympathetic activity and imbalanced sympathetic nervous system could contribute to the prevalence of hypertension [33, 34].

The main strength of this study was the analysis of nonlinear associations between sleep timing and the prevalence of hypertension. The nonlinear association was adjusted for multiple covariates such as SDB and sleep duration. This study has some limitations. First, it had a cross-sectional design and could not provide a causal association between sleep timing and hypertension. Second, information on bedtime and wake-up time was acquired using a sleep habit questionnaire. Therefore, measurement and recall biases may exist. Third, bedtime, wake-up time and sleep midpoint are closely related to each other. Our findings can only suggest that individuals with suitable sleep timing may have a lowest hypertension risk. But it is difficult to judge which of the three sleep timing parameters (bedtime, wake-up time or sleep midpoint) is more strongly associated with hypertension. Finally, the results were based on middle-aged and older populations and cannot be extended to all ages.

Conclusion

Our study supports the nonlinear association between bedtime, wake-up time, sleep midpoint, and hypertension. Individuals with both late and early sleep times have an increased risk of hypertension. These findings indicate that adopting proper bedtimes and wake-up times may be effective in reducing the prevalence of hypertension.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the Brigham and Women’s Hospital for sharing the Datasets of Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS). The Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS) was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute cooperative agreements U01HL53916 (University of California, Davis), U01HL53931 (New York University), U01HL53934 (University of Minnesota), U01HL53937 and U01HL64360 (Johns Hopkins University), U01HL53938 (University of Arizona), U01HL53940 (University of Washington), U01HL53941 (Boston University), and U01HL63463 (Case Western Reserve University). The National Sleep Research Resource was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R24 HL114473, 75N92019R002). SHHS is particularly grateful to the members of these cohorts who agreed to participate in SHHS as well. SHHS further recognizes all the investigators and staff who have contributed to its success.

Author contributions

B.Y. and S.Z. raised the idea for the study. S.Z., J.Z., S.W., W.W., Y.W., and B.Y. contributed to the study design, writing and review of the report. B.Y. acquired the data in SHHS and participated in further data analysis B.Y. handled supervision in our study. All authors approved the final version of the report.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi (No. 2021JQ-395).

Data availability

The data using in this study was obtained from SHHS datasets (10.25822/ghy8-ks59).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of each participating institution (Boston University, Case Western Reserve University, Johns Hopkins University, Missouri Breaks Research Inc., New York University Medical Center, University of Arizona, University of California at Davis, University of Minnesota-Clinical and Translational Science Institute, and the University of Washington). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA, et al. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115 mm hg, 1990–2015. JAMA. 2017;317:165–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oparil S, Acelajado MC, Bakris GL, et al. Hypertension. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension. 2019.

- 4.Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and control of hypertension: Jacc health promotion series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1278–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palagini L, Bruno RM, Gemignani A, Baglioni C, Ghiadoni L, Riemann D. Sleep loss and hypertension: a systematic review. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:2409–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas DC, Foster GL, Nieto FJ, et al. Age-dependent associations between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension: importance of discriminating between systolic/diastolic hypertension and isolated systolic hypertension in the sleep heart health study. Circulation. 2005;111:614–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao J, Wang W, Wei S, Yang L, Wu Y, Yan B. Fragmented sleep and the prevalence of hypertension in middle-aged and older individuals. Nat Sci Sleep. 2021;13:2273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L, Hu Y, Wang X, Yang S, Chen W, Zeng Z. The association between sleep duration and hypertension: a meta and study sequential analysis. J Hum Hypertens. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Abbott SM, Weng J, Reid KJ, et al. Sleep timing, stability, and bp in the sueno ancillary study of the hispanic community health study/study of latinos. Chest. 2019;155:60–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su Y, Li C, Long Y, He L, Ding N. Association between bedtime at night and systolic blood pressure in adults in nhanes. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:734791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jansen EC, Dunietz GL, Matos-Moreno A, Solano M, Lazcano-Ponce E, Sanchez-Zamorano LM. Bedtimes and blood pressure: a prospective cohort study of Mexican adolescents. Am J Hypertens. 2020;33:269–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quan SF, Howard BV, Iber C, et al. The sleep heart health study: design, rationale, and methods. Sleep. 1997;20:1077–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang GQ, Cui L, Mueller R, et al. The national sleep research resource: towards a sleep data commons. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2018;25:1351–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C, Hu B, Rangarajan S, et al. Association of bedtime with mortality and major cardiovascular events: an analysis of 112,198 individuals from 21 countries in the pure study. Sleep Med. 2021;80:265–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li B, Fan Y, Zhao B, et al. Later bedtime is associated with angina pectoris in middle-aged and older adults: results from the sleep heart health study. Sleep Med. 2021;79:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Gu Y, Zheng L et al. Association between bedtime and the prevalence of newly diagnosed non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. Liver International: Official J Int Association Study Liver. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Sasaki N, Fujiwara S, Yamashita H, et al. Association between obesity and self-reported sleep duration variability, sleep timing, and age in the Japanese population. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2018;12:187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaput JP, Dutil C, Featherstone R, et al. Sleep timing, sleep consistency, and health in adults: a systematic review. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2020;45:S232–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snell EK, Adam EK, Duncan GJ. Sleep and the body mass index and overweight status of children and adolescents. Child Dev. 2007;78:309–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baron KG, Reid KJ, Kern AS, Zee PC. Role of sleep timing in caloric intake and bmi. Obesity. 2011;19:1374–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM, Newman AB, et al. Association of sleep time with diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:863–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan B, Fan Y, Zhao B, et al. Association between late bedtime and diabetes mellitus: a large community-based study. J Clin Sleep Medicine: JCSM : Official Publication Am Acad Sleep Med. 2019;15:1621–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeineddine S, Rowley JA, Chowdhuri S. Oxygen therapy in sleep-disordered breathing. Chest. 2021;160:701–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chami HA, Resnick HE, Quan SF, Gottlieb DJ. Association of incident cardiovascular disease with progression of sleep-disordered breathing. Circulation. 2011;123:1280–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azarbarzin A, Sands SA, Younes M, et al. The sleep apnea-specific pulse-rate response predicts cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:1546–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roca GQ, Redline S, Claggett B, et al. Sex-specific association of sleep apnea severity with subclinical myocardial injury, ventricular hypertrophy, and heart failure risk in a community-dwelling cohort: the atherosclerosis risk in communities-sleep heart health study. Circulation. 2015;132:1329–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep heart health study. JAMA. 2000;283:1829–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costello HM, Gumz ML. Circadian rhythm, clock genes, and hypertension: recent advances in hypertension. Hypertension. 2021;78:1185–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheer FA, Hilton MF, Mantzoros CS, Shea SA. Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4453–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smolensky MH, Hermida RC, Castriotta RJ, Portaluppi F. Role of sleep-wake cycle on blood pressure circadian rhythms and hypertension. Sleep Med. 2007;8:668–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenlund IM, Carter JR. Sympathetic neural responses to sleep disorders and insufficiencies. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2022;322:H337–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fink AM, Bronas UG, Calik MW. Autonomic regulation during sleep and wakefulness: a review with implications for defining the pathophysiology of neurological disorders. Clin Auton Res. 2018;28:509–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherwood A, Routledge FS, Wohlgemuth WK, Hinderliter AL, Kuhn CM, Blumenthal JA. Blood pressure dipping: ethnicity, sleep quality, and sympathetic nervous system activity. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:982–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirooka Y. Sympathetic activation in hypertension: importance of the central nervous system. Am J Hypertens. 2020;33:914–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data using in this study was obtained from SHHS datasets (10.25822/ghy8-ks59).