Abstract

Background

The risk for heart failure (HF) is increased among cancer survivors, but predicting individual HF risk is difficult. Polygenic risk scores (PRS) for HF prediction summarize the combined effects of multiple genetic variants specific to the individual.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to compare clinical HF prediction models with PRS in both cancer and noncancer populations.

Methods

Cancer and HF diagnoses were identified using International Classification of Diseases-10th Revision codes. HF risk was calculated using the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) HF score (ARIC-HF). The PRS for HF (PRS-HF) was calculated according to the Global Biobank Meta-analysis Initiative. The predictive performance of the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF was compared using the area under the curve (AUC) in both cancer and noncancer populations.

Results

After excluding 2,644 participants with HF prior to consent, 440,813 participants without cancer (mean age 57 years, 53% women) and 43,720 cancer survivors (mean age 60 years, 65% women) were identified at baseline. Both the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF were significant predictors of incident HF after adjustment for chronic kidney disease, overall health rating, and total cholesterol. The PRS-HF performed poorly in predicting HF among cancer (AUC: 0.552; 95% CI: 0.539-0.564) and noncancer (AUC: 0.561; 95% CI: 0.556-0.566) populations. However, the ARIC-HF predicted incident HF in the noncancer population (AUC: 0.804; 95% CI: 0.800-0.808) and provided acceptable performance among cancer survivors (AUC: 0.748; 95% CI: 0.737-0.758).

Conclusions

The prediction of HF on the basis of conventional risk factors using the ARIC-HF score is superior compared to the PRS, in cancer survivors, and especially among the noncancer population.

Key Words: cancer, heart failure, polygenic, prognosis

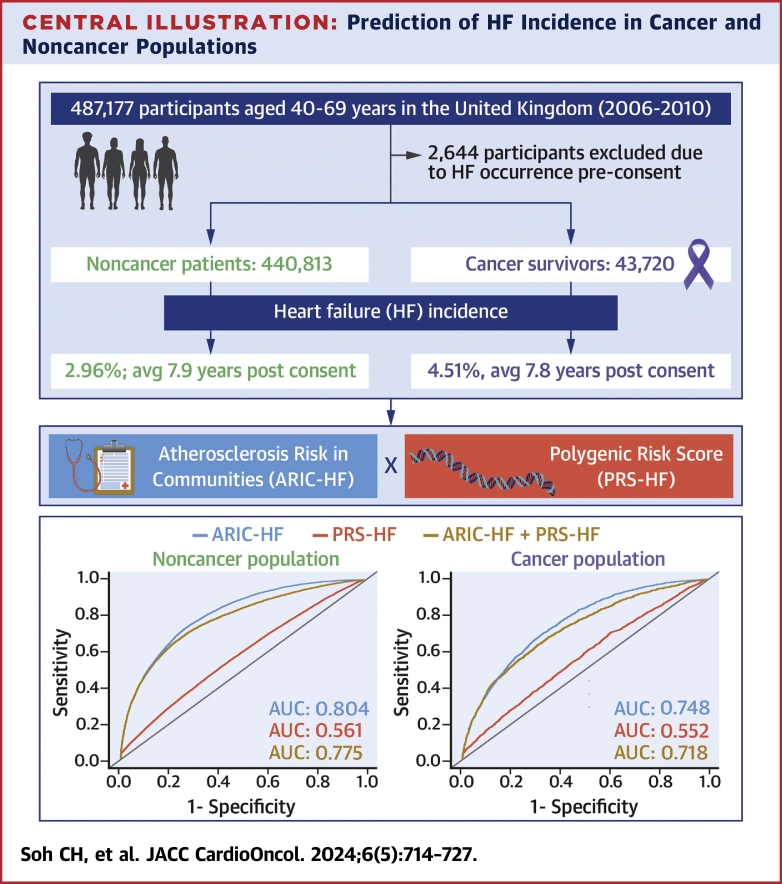

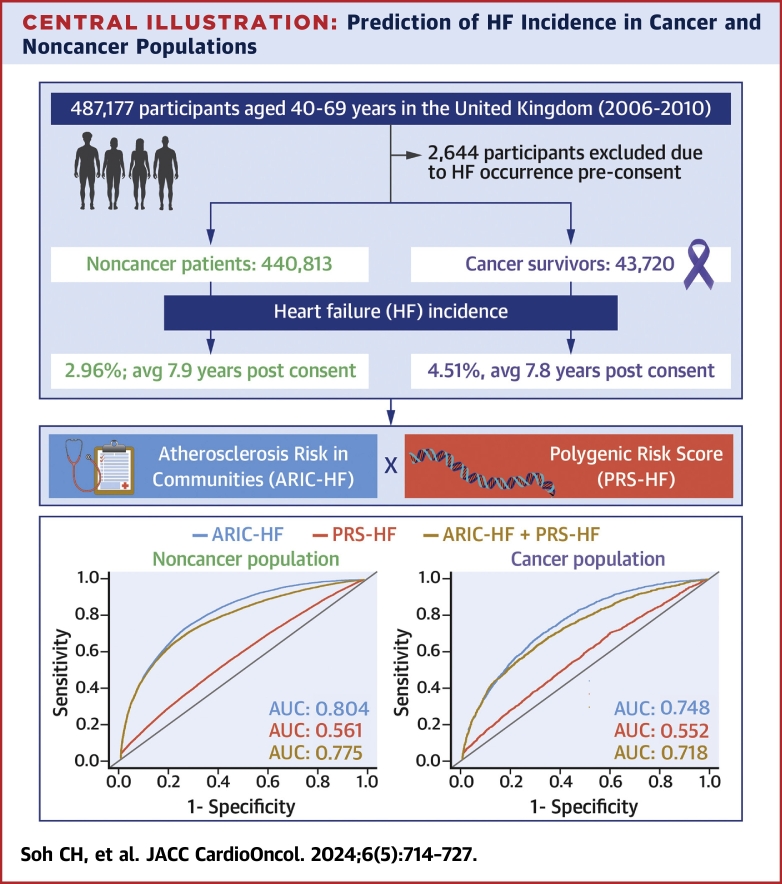

Central Illustration

The risk for heart failure (HF) is increased among cancer survivors. As HF is a leading cause of hospitalization and has a high mortality rate,1 earlier recognition of survivors at risk for HF would be of value. Echocardiography is widely used for the assessment of left ventricular function during chemotherapy, but assessment of pretest risk would be desirable to target the use of this test among survivors. A variety of clinical risk scores have been developed in patients with HF risk factors. The ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities) HF score (ARIC-HF)2 includes conventional HF risk factors, such as age, sex, race, blood pressure, medications, and medical history. However, despite demonstrating high predictive accuracy in a community setting, it is unknown if the ARIC-HF remains a strong HF prognostic tool in the cancer population, because of unmeasured contributions from inflammation,3 hormonal changes,4 or other side effects from cancer treatments.5

HF risk is influenced by many single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are directly associated with HF,6 as well as other causative factors, including HF risk factors. Given that genome-wide association studies have been carried out for HF, the resultant SNP effects can be used to compute the polygenic risk score for HF (PRS-HF).7 This approach could be uniquely suited to HF in survivors, as increasing numbers of at-risk patients with cancer undergo genetic testing. However, data on the performance of the PRS-HF in a cancer population are lacking. Demonstrating the predictive accuracy for HF incidence could not only promote the use of either prognostic tool in both research and clinical settings but also provide a better understanding of the polygenic contribution to HF in cancer survivors. Accordingly, we sought to compare the PRS-HF and ARIC-HF models, as well as the incremental value of the PRS-HF in addition to the ARIC-HF for predicting HF among cancer and noncancer populations.

Methods

Study design and setting

The UK Biobank is a large population-based, prospective cohort study with roughly 500,000 participants 35 years or older, recruited from 2006 to 2010.8 Participants underwent a baseline assessment visit after providing consent. The visit included obtaining information on participants’ health and lifestyles, hearing, and cognitive function, which was collected through a touchscreen questionnaire and a brief verbal interview. A range of physical measurements were also performed, comprising blood pressure, arterial stiffness, eye measurements, body composition, handgrip strength, ultrasound bone densitometry, spirometry, and a fitness test with electrocardiography. Blood, urine, and saliva samples were also collected. This study used version 3.4 of the UK Biobank database.

Ethical approval

The present analysis was conducted under application ID 55469 for analysis of the UK Biobank data, approved by the North West–Haydock Research Ethics Committee (16/NW/0274). The study followed the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was provided by all participants.

Cancer diagnosis

Participants were stratified into cancer and noncancer populations on the basis of documentation of cancer diagnoses (field ID 40006) using International Classification of Diseases-10th Revision (ICD-10) codes.9 Cancer types were determined from codes C00 to C97 and D00 to D48. Dates of diagnoses were also captured during ICD-10 code documentation. A 2 × 2 contingency table demonstrating the differences between self-reported (field ID 134, field ID 2453) and ICD-10-coded cancer diagnoses is reported in Supplemental Table 1. As the focus of this study was to examine the prediction of HF at the time point of baseline evaluation in the UK Biobank, only baseline clinical characteristics were used. The noncancer population included participants who had cancer diagnosed after baseline (Supplemental Table 2 demonstrates the characteristics of the UK Biobank participants stratified according to their cancer status after providing consent). A post hoc analysis merging participants with cancer diagnoses prior to and after UK Biobank consent was also performed.

The ARIC-HF

The ARIC-HF2 is calculated on the basis of a multivariable model including various HF risk factors and is presented as the probability of HF incidence in the next 10 years. The ARIC-HF was calculated for all participants. Clinical characteristics included in the calculation were age (UK Biobank field ID 33), race (field ID 21000), sex (field ID 31), heart rate (field ID 102), systolic blood pressure (field ID 4080), blood pressure–lowering medication (field IDs 6177 and 6153), diabetes (field IDs 2443 and 41202), coronary heart disease (field ID 41202), smoking status (field ID 20116), and body mass index (field ID 21001).

Other clinical characteristics

Other clinical characteristics, such as alcohol consumption (field ID 20117), diastolic blood pressure (field ID 4079), cholesterol level (field IDs 30690, 30760, and 30790), International Physical Activity Questionnaire activity level (field ID 22032), and a self-reported overall health rating (field ID 2178), were included in this analysis. Diagnoses of comorbidities such as hypercholesterolemia, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and obesity were computed on the basis of ICD-10 codes.

The PRS-HF

A precalculated multiancestry PRS-HF model developed using a training sample size of 919,746 individuals with no sample overlapping with the UK Biobank7 was implemented in this study. This PRS-HF was sourced from SNP effects or weights generated by the Global Biobank Meta-analysis Initiative.7 Briefly, 910,146 HapMap3 SNPs were used to train the weights for HF data using a Bayesian approach (PRS-CS-auto).10 This polygenic risk score (PRS) model was trained on 919,746 individuals, 65.3% of whom had European ancestry, 28% East Asian ancestry, 2.7% African ancestry, and 4% other ancestries. These training samples have no overlap with the UK Biobank data. Then, plink was used to compute the PRS-HF in the UK Biobank with SNPs satisfying minor allele frequency >0.01 and default plink settings.11 This resulted in 3,652 ambiguous SNPs’ being removed and therefore 906,494 (99.6%) of input SNPs’ remaining in the analysis. The SNP weights were generated from the multiancestry genome-wide association studies, and details can be found in the open database for Polygenic Score catalogue12 (ID PGS001790).

HF incidence

Similar to cancer diagnoses, HF incidence was determined on the basis of a documentation of diagnosis using ICD-10 code I50. Date of HF diagnosis was also documented, and the duration from consent date to date of HF diagnosis was calculated. Participants who had histories of HF at baseline were excluded from this study.

Statistical analysis

Participants’ baseline characteristics are reported using descriptive statistics. All continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD, while categorical variables are reported as count (percentage). To compare participants’ baseline characteristics between the cancer and noncancer populations as determined at baseline, Student’s t-tests were performed on continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. The cumulative incidence plots for HF incidence were generated for cancer and noncancer populations.

To evaluate the risk factors associated with HF incidence, Fine and Gray competing risk regression models13 were performed for cancer and noncancer populations, with death as a competing risk. The univariable competing risk regression model for each characteristic was reported with the effect size of subdistribution HR (sHR) and the 95% CI. Key risk factors were then selected using a stepwise backward regression approach, with only variables with P values of <0.05 retained in the model, to generate the multivariable regression model for HF incidence. The goodness-of-fit test procedures were performed to check for model assumptions: 1) cause-specific proportionality of sHR; 2) linear functional forms of individual covariates; and 3) the link function. In addition, multicollinearity was evaluated using variance inflation factors for the multivariable regression model. Variables were removed from the multivariable model if their variance inflation factors were higher than 10.

The performance of the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF in predicting HF incidence was evaluated using the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC). The receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the ARIC-HF, the PRS-HF, and a model combining both risk scores were generated for cancer and noncancer populations. The ARIC-HF and PRS-HF were combined using a weighted sum with the weight based on the logarithm of their sHRs. The continuous net reclassification improvement was also assessed to evaluate the overall improvement on the combination of the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF. The predictive performance of these models was also analyzed in a White-only population (on the basis of self-reported ethnic background [field ID 21000]) because PRS has been reported as best performed in the White population.14 The ROC curves for PRS, adjusted for multiple HF risk factors, were also shown, along with the AUC and 95% CI on the basis of the bootstrap approach. Post hoc analyses of sex and cancer types were performed to account for their confounding effects on the performance of the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF. A post hoc analysis excluding participants with any discrepancies between self-report and ICD-10-based cancer diagnoses was also performed to eliminate any potential over- or underestimation on the effect sizes of the independent variables.

P values of <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were conducted in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Participants with missing data were excluded from the analyses. A sensitivity analysis including all participants, with their missing data imputed via multiple imputation by chain equations (number of imputations = 5, number of iterations = 10), was also performed to identify the impact of excluding participants with missing data. The pooled estimates were calculated according to Rubin’s rule.

Results

Participant characteristics

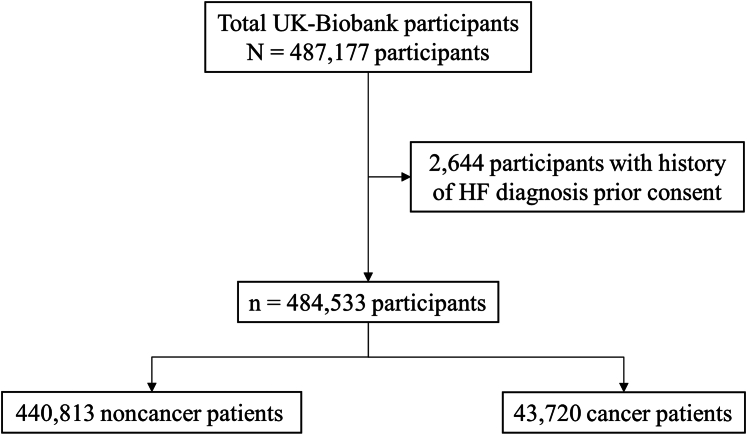

Of the total 487,177 participants, 2,644 participants had HF diagnoses prior to consenting for the UK Biobank study and therefore were excluded from this analysis (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the remaining participants from the UK Biobank, stratified by cancer or noncancer population at baseline. The participants without cancer (n = 440,813) were generally younger compared with the cancer population at baseline. The prevalence of comorbidities, including diabetes, coronary heart disease, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease, were also higher within the cancer survivors (n = 43,720). The ARIC-HF was also higher among the cancer population, with the mean ARIC-HF for cancer and noncancer populations being 1.36% and 1.12%, respectively. The cancer diagnoses of the cancer survivors, along with the prevalence of HF incidence in each cancer type, are provided in Table 2. The main cancer diagnoses were melanoma and other skin cancers (18.7%), breast cancer (16.9%), and benign neoplasms (11.7%).

Figure 1.

Study Flowchart

The UK Biobank comprises a total of 487,177 participants. After excluding 2,644 participants with histories of heart failure (HF) before consenting to the UK Biobank study, 484,533 participants were included in the analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Participants From the UK Biobank

| Data Available (n) | Noncancer Population (n = 440,813) |

Cancer Survivors (n = 43,720) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| Age, y | 484,533 | 56.72 ± 8.11 | 60.03 ± 7.33 | <0.001 |

| Female | 484,533 | 234,967 (53.30) | 28,516 (65.22) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | 484,014 | <0.001 | ||

| White | 414,121 (93.94) | 42,497 (97.2) | ||

| Asian | 9,062 (2.06) | 282 (0.65) | ||

| Black | 7,264 (1.65) | 347 (0.79) | ||

| Chinese | 1,437 (0.33) | 62 (0.14) | ||

| Mixed | 2,654 (0.60) | 172 (0.39) | ||

| Other | 4,141 (0.94) | 200 (0.46) | ||

| Alcohol consumption | 484,014 | <0.001 | ||

| Never | 19,493 (4.42) | 1,840 (4.21) | ||

| Previous | 15,476 (3.51) | 1,770 (4.05) | ||

| Current | 404,698 (91.81) | 40,033 (91.57) | ||

| Smoking status | 484,017 | <0.001 | ||

| Never | 242,286 (54.96) | 22,095 (50.54) | ||

| Previous | 149,841 (33.99) | 16,986 (38.85) | ||

| Current | 46,440 (10.54) | 4,403 (10.07) | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 482,599 | 27.42 ± 4.78 | 27.27 ± 4.80 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 461,791 | 5.69 ± 1.14 | 5.75 ± 1.18 | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 422,699 | 1.45 ± 0.38 | 1.49 ± 0.39 | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 460,928 | 3.56 ± 0.87 | 3.58 ± 0.89 | <0.001 |

| Blood pressure | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 457,546 | 137.72 ± 18.58 | 139.12 ± 19.17 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 457,551 | 82.28 ± 10.14 | 81.83 ± 10.06 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 457,551 | 69.25 ± 11.22 | 70.27 ± 11.45 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 484,533 | 22,432 (5.09) | 2,399 (5.49) | <0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 484,533 | 21,190 (4.81) | 2,188 (5.00) | 0.068 |

| Hypertension | 484,533 | 2,273 (0.52) | 288 (0.66) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 484,533 | 95 (0.02) | 9 (0.02) | 0.99 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 484,533 | 1,394 (0.32) | 235 (0.54) | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 484,533 | 821 (0.18) | 60 (0.14) | 0.025 |

| Medications | ||||

| Insulin | 484,533 | 4,719 (1.07) | 482 (1.10) | 0.55 |

| Blood pressure medication | 484,533 | 88,971 (20.18) | 10,623 (24.30) | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol-lowering medication | 484,533 | 74,398 (16.88) | 8,490 (19.42) | <0.001 |

| IPAQ activity group | 391,163 | <0.001 | ||

| Low | 66,953 (15.19) | 6,745 (15.43) | ||

| Moderate | 145,073 (32.91) | 14,341 (32.80) | ||

| High | 144,526 (32.79) | 13,525 (30.94) | ||

| Overall health rating | 481,619 | <0.001 | ||

| Excellent | 74,382 (16.87) | 5,308 (12.14) | ||

| Good | 255,845 (58.04) | 24,283 (55.54) | ||

| Fair | 89,779 (20.37) | 10,964 (25.08) | ||

| Poor | 18,218 (4.13) | 2,840 (6.50) | ||

| PRS-HF | 484,533 | −0.01 ± 0.10 | −0.01 ± 0.10 | 0.082 |

| ARIC-HF 10-y risk, % | 455,360 | 1.12 ± 2.03 | 1.36 ± 2.17 | <0.001 |

| Follow-up | ||||

| Heart failure incidence | 484,533 | 13,059 (2.96) | 1,970 (4.51) | <0.001 |

| Days since consent | 2,887 ± 1,259 | 2,833 ± 1,267 | 0.075 | |

| Death | 484,533 | 29,155 (6.61) | 6,271 (14.34) | <0.001 |

| Days since consent | 2,986 ± 1,243 | 2,606 ± 1,364 | <0.001 |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%).

ARIC-HF = Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities heart failure score; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; IPAQ = International Physical Activity Questionnaire; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; PRS-HF = polygenic risk score for heart failure.

Table 2.

Cancer Diagnoses of the UK Biobank Cancer Survivors

| Total (n = 43,720) |

HF Incidence | |

|---|---|---|

| Malignant neoplasms of lip, oral cavity, and pharynx | 562 (1.29) | 28 (4.98) |

| Malignant neoplasms of digestive organs | 3,541 (8.10) | 213 (6.02) |

| Malignant neoplasms of respiratory and intrathoracic organs | 1,157 (2.65) | 86 (7.43) |

| Malignant neoplasms of bone and articular cartilage | 82 (0.19) | 4 (4.88) |

| Melanoma and other malignant neoplasms of skin | 8,158 (18.66) | 406 (4.98) |

| Malignant neoplasms of mesothelial and soft tissue | 339 (0.78) | 19 (5.60) |

| Malignant neoplasms of breast | 7,377 (16.87) | 275 (3.73) |

| Malignant neoplasms of female genital organs | 1,636 (3.74) | 62 (3.79) |

| Malignant neoplasms of male genital organs | 3,203 (7.33) | 203 (6.34) |

| Malignant neoplasms of urinary tract | 1,853 (4.24) | 155 (8.36) |

| Malignant neoplasms of eye, brain, and other parts of central nervous system | 299 (0.68) | 11 (3.68) |

| Malignant neoplasms of thyroid and other endocrine glands | 298 (0.68) | 16 (2.37) |

| Malignant neoplasms of ill-defined, secondary and unspecified sites | 2,848 (6.51) | 155 (5.44) |

| Malignant neoplasms, stated or presumed to be primary, of lymphoid, hematopoietic, and related tissue | 1,953 (4.47) | 213 (10.9) |

| Malignant neoplasms of independent (primary) multiple sites | 379 (0.87) | 22 (5.80) |

| In situ neoplasms | 3,163 (7.23) | 136 (4.30) |

| Benign neoplasms | 5,131 (11.74) | 340 (6.63) |

| Neoplasms of uncertain or unknown behavior | 1,895 (4.33) | 132 (6.97) |

Values are n (%). Cancer diagnoses were classified according to International Classification of Diseases-10th Revision code.

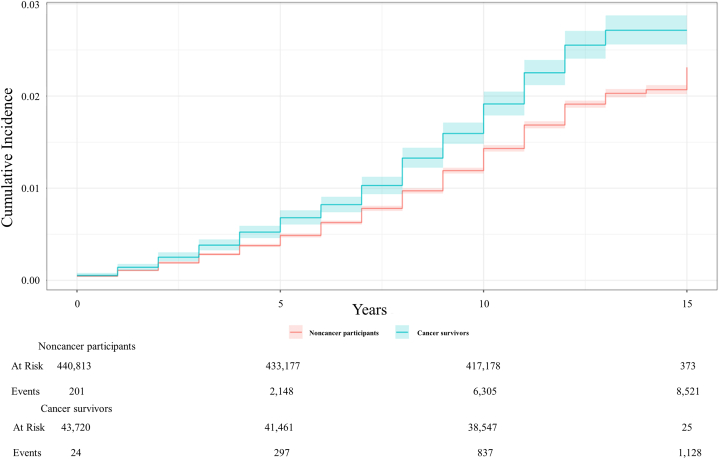

HF incidence

The raw HF incidence rates for the cancer and noncancer populations were 4.51% and 2.96%, respectively (Table 1). There was also a total of 70,553 participants diagnosed with cancer after providing consent (Supplemental Table 2). After merging all participants with cancer diagnoses, the overall HF incidence rates for both the noncancer (n = 370,260) and cancer (n = 114,273) populations were 2.62% and 3.75%, respectively. Figure 2 demonstrates the cumulative incidence plot of HF for the cancer and noncancer populations in the competing risk model. From baseline to 15 years postconsent, the proportion of HF occurrence in the cancer population was greater than in the noncancer population at all times.

Figure 2.

Cumulative Incidence of Heart Failure in a Competing Risk Model

Death was set as a competing risk in both the cancer and noncancer populations. The cumulative incidence of heart failure was consistently higher among cancer survivors compared with the noncancer population in the UK Biobank study.

Risk factors for HF

The univariable competing risk regression on HF occurrence showed that age, sex, and comorbidities including diabetes, coronary heart disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, chronic kidney disease, and obesity were significantly associated with HF (Table 3). Specifically, cancer was shown to have a significant association with increased risk for HF incidence (sHR: 1.53; 95% CI: 1.46-1.61). Increased systolic blood pressure was shown to be associated with increased risk for HF incidence in the cancer population (sHR: 1.26; 95% CI: 1.19-1.33) and the noncancer population (sHR: 1.36; 95% CI: 1.34-1.39), while increased cholesterol level was protective against HF incidence in the cancer population (sHR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.69-0.79) and the noncancer population (sHR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.69-0.73). In addition, International Physical Activity Questionnaire activity group and smoking were also associated with HF incidence in both the cancer and noncancer populations. Each 1-point increase in the ARIC-HF was shown to be significantly associated with increased risk for HF among both the cancer (sHR: 1.26; 95% CI: 1.23-1.29) and noncancer (sHR: 1.24; 95% CI: 1.21-1.27) populations. Higher PRS-HF was also associated with greater risk for HF in both the cancer and noncancer populations.

Table 3.

Univariable Competing Risk Regression on Heart Failure Occurrence in the UK Biobank Participants

| Heart Failure Incidence (Univariable) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noncancer Population (n = 420,268) |

Cancer Survivors (n = 41,523) |

|||

| sHR (95% CI) | P Value | sHR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| ARIC-HF, per 1-point increase | 1.24 (1.21-1.27) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.23-1.29) | <0.001 |

| Polygenic risk score, per unit increase | 1.24 (1.21-1.26) | <0.001 | 1.20 (1.13-1.27) | <0.001 |

| Age, per 1-y increase | 2.22 (2.16-2.28) | <0.001 | 1.85 (1.71-2.02) | <0.001 |

| Male | 1.94 (1.86-2.03) | <0.001 | 1.70 (1.51-1.90) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 3.17 (2.98-3.37) | <0.001 | 2.46 (2.06-2.94) | <0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 8.70 (8.30-9.11) | <0.001 | 6.16 (5.37-7.06) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 3.65 (3.12-4.28) | <0.001 | 3.98 (2.74-5.77) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 4.91 (2.47-9.77) | <0.001 | − | − |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5.39 (4.56-6.38) | <0.001 | 4.18 (2.78-6.26) | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 3.13 (2.36-4.15) | <0.001 | 3.28 (1.40-7.66) | 0.006 |

| IPAQ activity group | ||||

| Low | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| Moderate | 0.78 (0.73-0.83) | <0.001 | 0.84 (0.71-1.00) | 0.053 |

| High | 0.76 (0.72-0.81) | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.64-0.91) | 0.003 |

| Overall health rating | ||||

| Poor | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| Fair | 0.57 (0.53-0.61) | <0.001 | 0.66 (0.55-0.80) | <0.001 |

| Good | 0.28 (0.26-0.30) | <0.001 | 0.37 (0.31-0.44) | <0.001 |

| Excellent | 0.16 (0.14-0.17) | <0.001 | 0.24 (0.18-0.32) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, per 1 mm Hg increase | 1.36 (1.34-1.39) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.19-1.33) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, per 1 mm Hg increase | 1.08 (1.05-1.10) | <0.001 | 1.08 (1.01-1.15) | 0.017 |

| Heart rate, per 1 beats/min increase | 1.07 (1.04-1.10) | <0.001 | 1.09 (1.03-1.16) | 0.006 |

| Total cholesterol, per 1 mmol/L increase | 0.71 (0.69-0.73) | <0.001 | 0.74 (0.69-0.79) | <0.001 |

| HDL, per 1 mmol/L increase | 0.69 (0.67-0.71) | <0.001 | 0.77 (0.72-0.83) | <0.001 |

| LDL, per 1 mmol/L increase | 0.74 (0.72-0.76) | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.71-0.82) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, per 1 kg/m2 increase | 1.49 (1.46-1.51) | <0.001 | 1.41 (1.35-1.48) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| Previous | 1.58 (1.51-1.66) | <0.001 | 1.40 (1.23-1.58) | <0.001 |

| Current | 1.58 (1.47-1.69) | <0.001 | 1.57 (1.30-1.89) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| Never | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| Previous | 1.29 (1.13-1.46) | <0.001 | 1.25 (0.87-1.80) | 0.22 |

| Current | 0.77 (0.70-0.85) | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.65-1.12) | 0.25 |

Death was identified as a competing risk in the cancer and noncancer populations.

sHR = subdistribution HR; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Table 4 describes the independent association of HF incidence, identified by multivariable competing risk regression. The multivariable model included the ARIC-HF, the PRS-HF, chronic kidney disease, total cholesterol level, and the participant’s overall health rating. Chronic kidney disease was shown to be a strong risk factor for HF incidence in the cancer population (adjusted sHR: 2.50; 95% CI: 1.57-3.97) and the noncancer population (adjusted sHR: 2.48; 95% CI: 1.99-3.09). Greater ARIC-HF and PRS-HF were both shown to be associated with increased risk for HF incidence in both the cancer and noncancer populations. Participants’ overall health ratings were also shown to be associated with HF incidence: the better the participants felt about their own health, the lower their risk for HF incidence. Higher cholesterol level was also shown to be associated with HF incidence, with the cancer population showing an sHR of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.81-0.92) and the noncancer population showing an sHR of 0.83 (95% CI: 0.81-0.85). After merging the participants with cancer diagnoses before and after providing UK Biobank consent, the sHRs for the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF were 1.19 (95% CI: 1.16-1.22) and 1.16 (95% CI: 1.11-1.21), respectively, among the cancer population (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 4.

Multivariable Competing Risk Regression on Heart Failure Incidence in the UK Biobank Participants

| Heart Failure Incidence (Multivariable Model) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noncancer Population (n = 420,268) |

Cancer Survivors (n = 41,523) |

|||

| sHR (95% CI) | P Value | sHR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| ARIC-HF, per 1-point increase | 1.19 (1.17-1.22) | <0.001 | 1.21 (1.18-1.24) | <0.001 |

| Polygenic risk score, per unit increase | 1.17 (1.14-1.20) | <0.001 | 1.14 (1.07-1.21) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2.48 (1.99-3.09) | <0.001 | 2.50 (1.57-3.97) | <0.001 |

| Overall health rating | ||||

| Poor | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| Fair | 0.71 (0.64-0.79) | <0.001 | 0.77 (0.63-0.94) | 0.012 |

| Good | 0.42 (0.38-0.46) | <0.001 | 0.49 (0.40-0.60) | <0.001 |

| Excellent | 0.25 (0.22-0.28) | <0.001 | 0.34 (0.25-0.46) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, per 1 mmol/L increase | 0.83 (0.81-0.85) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.81-0.92) | <0.001 |

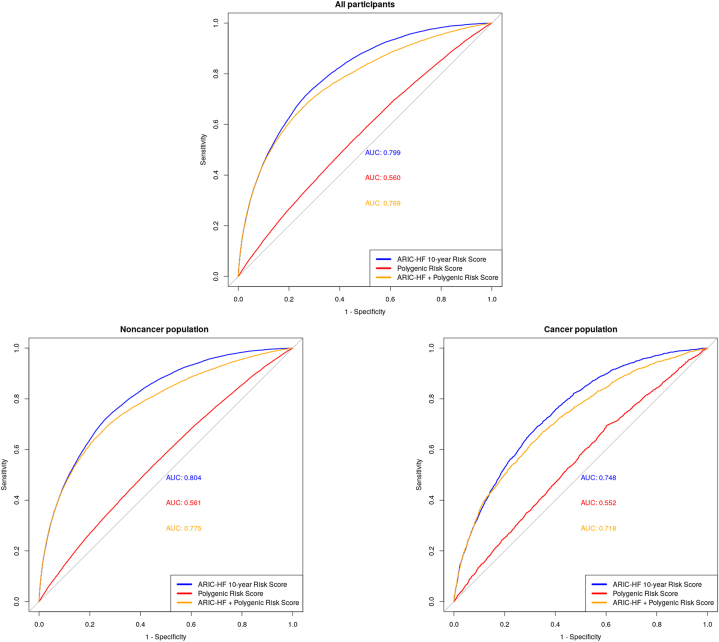

The accuracy of the PRS-HF and ARIC-HF in predicting HF

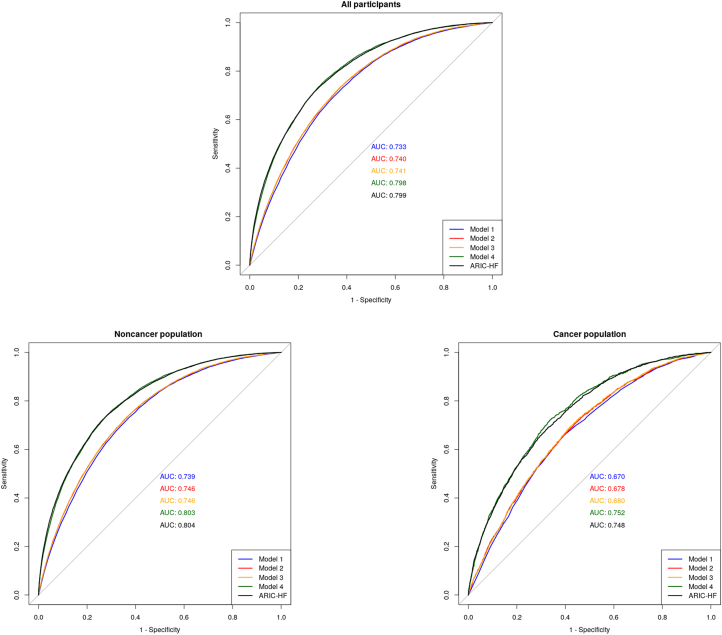

To compare the performance of the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF in predicting HF, Figure 3 demonstrates the ROC curve of each of the prognostic tools in all participants, as well as stratifying by cancer and noncancer populations. In all participants, the ARIC-HF was better in predicting incident HF (AUC: 0.799; 95% CI: 0.795-0.802) than the PRS-HF (AUC: 0.560; 95% CI: 0.555-0.564). Looking at the noncancer population specifically, the ARIC-HF showed excellent discriminatory performance, with an AUC of 0.804 (95% CI: 0.800-0.808), whereas the PRS-HF remained poor (AUC: 0.561; 95% CI: 0.556-0.566). The performance of both the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF dropped slightly within the cancer population, with AUCs of 0.748 (95% CI: 0.737-0.758) and 0.552 (95% CI: 0.539-0.564), respectively. In the post hoc analysis merging the participants with cancer diagnoses before and after providing UK Biobank consent, the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF showed AUCs of 0.735 (95% CI: 0.727-0.742) and 0.552 (95% CI 0.544-0.561), respectively, among the cancer population (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 3.

Unadjusted Receiver-Operating Characteristic Curve in Predicting HF

The area under the unadjusted receiver-operating characteristics curve for the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities-Heart Failure (ARIC-HF) score was higher than for the polygenic risk score for heart failure (HF) in predicting HF incidence in both the cancer and noncancer populations. AUC = area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve.

Combining the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF did not improve the overall predictive performance for HF incidence. The AUCs of the combined risk scores were 0.718 (95% CI: 0.706-0.730) and 0.775 (95% CI: 0.770-0.779) in cancer and noncancer populations, respectively. Similar findings were shown in the continuous net reclassification improvement plot between a standard model (ARIC-HF) and the combined model (ARIC-HF plus PRS-HF), as demonstrated in Supplemental Figure 2. A heat map was constructed to demonstrate the discriminative performance of the ARIC-HF, the PRS-HF, and the combined score by identifying the prevalence of HF incidence in each quartile (Supplemental Table 4).

Models comprising the PRS-HF and multiple HF risk factors were constructed, and their corresponding predictive performance is demonstrated in Figure 4. A baseline model comprising age and sex showed an AUC of 0.733 (95% CI: 0.729-0.737) among all participants, and the integration of the PRS-HF resulted in an improvement in predictive performance (AUC: 0.740; 95% CI: 0.736-0.744). A model comprising age, sex, ethnicity, vital signs, body mass index, cholesterol level, smoking status, diabetes, fitness level, blood pressure medications, chronic kidney disease, and the PRS-HF (AUC: 0.798; 95% CI: 0.794-0.803) performed similarly to an unadjusted ARIC-HF model (AUC: 0.799; 95% CI: 0.795-0.802). The final model including the PRS-HF performed best among the noncancer population, with an AUC of 0.803 (95% CI: 0.799-0.807), compared with an AUC of 0.752 (95% CI: 0.740-0.765) among the cancer population.

Figure 4.

Receiver-Operating Characteristic Curves for Adjusted PRS-HF Models in Predicting HF

Model 1 included age and sex. Model 2 included age, sex, and the polygenic risk score for HF (PRS-HF). Model 3 included age, sex, the PRS-HF, and systolic blood pressure. Model 4 included age, sex, the PRS-HF, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, chronic kidney disease, smoking status, total cholesterol level, blood pressure medication, ethnicity, body mass index, diabetes, and International Physical Activity Questionnaire activity group. The PRS-HF, adjusted for multiple HF risk factors, had a similar predictive performance as the unadjusted ARIC-HF in the prediction of HF incidence among all participants. Abbreviations as in Figure 3.

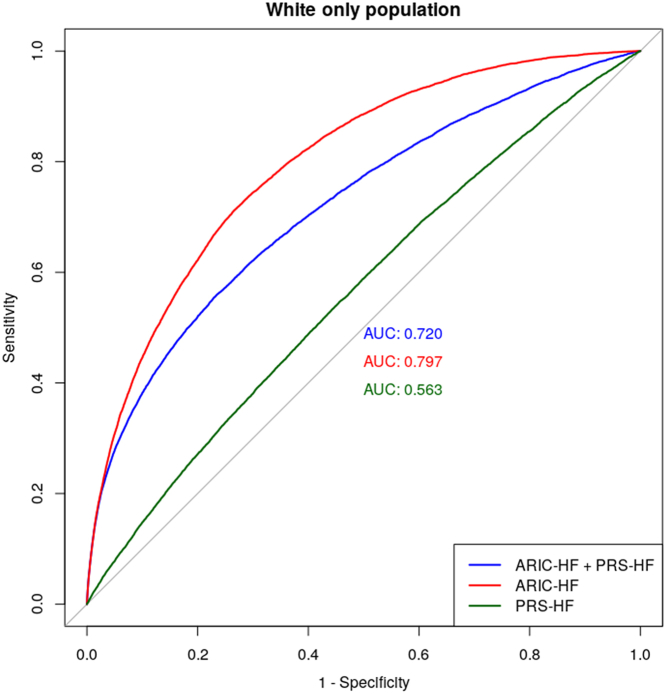

The predictive performance of the PRS-HF and ARIC-HF in a White-only population is shown in Figure 5, with AUCs of 0.563 and 0.797, respectively. Similar to the analysis in the total population, combining both the PRS-HF and ARIC-HF resulted in worse performance, with an AUC of 0.720 in predicting HF incidence. Supplemental Table 5 demonstrates the post hoc analysis that was performed to evaluate the model performance within cancers with the highest HF prevalence: hematological (10.9%), urinary tract (8.4%), and respiratory (7.4%). The PRS-HF was shown to perform best in HF prediction among participants with respiratory malignancies (AUC: 0.580; 95% CI: 0.515-0.645) and worst among those with hematological malignancies (AUC: 0.535; 95% CI: 0.494-0.576). Additionally, a post hoc analysis showed that the performance of the ARIC-HF (AUC: 0.718; 95% CI: 0.702-0.733) and the PRS-HF (AUC: 0.550; 95% CI: 0.533-0.567) remained similar after excluding participants with skin cancer, in situ neoplasms, and benign neoplasms (Supplemental Table 6). Stratifying on the basis of participants’ sex, the performance in HF prediction was not significantly different, with the AUCs of the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF being 0.796 and 0.563, respectively, among women and 0.782 and 0.557, respectively, among men (Supplemental Table 7).

Figure 5.

The Predictive Performance of the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF in the White Only Population

In the White-only population, the ARIC-HF remained superior to the PRS-HF in HF prediction, and the combination of the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF did not result in greater predictive performance. Abbreviations as in Figures 3 and 4.

After excluding participants with any discrepancies between self-report and ICD-10-based cancer diagnoses (Supplemental Table 1), the AUCs for the ARIC-HF, the PRS-HF, and the combination of both were 0.771 (95% CI: 0.759-0.781), 0.533 (95% CI: 0.528-0.538), and 0.746 (95% CI: 0.714-0.778), respectively, among the cancer population (Supplemental Table 8). A sensitivity analysis including all participants via multiple imputation by chain equation showed that the pooled estimates of AUC for the ARIC-HF, the PRS-HF, and the combination of both were 0.783, 0.569, and 0.736, respectively, for cancer populations (Supplemental Table 9). For noncancer populations, the AUCs were 0.811, 0.576, and 0.768, respectively.

Discussion

The results of this study confirm that cancer survivors are at increased risk for incident HF. The PRS-HF was not useful in predicting HF: it underperformed compared with the ARIC-HF and did not provide incremental value to the ARIC-HF in either cancer or noncancer populations. Although adjustment for chronic kidney disease slightly improved both models, the PRS-HF remained a poor predictor of incident HF. Overall, our study demonstrates that the ARIC-HF is a useful predictor of HF incidence, especially among noncancer populations (Central Illustration).

Central Illustration.

Prediction of HF Incidence in Cancer and Noncancer Populations

The UK Biobank comprises a total of 487,177 participants recruited between 2006 and 2010 throughout the United Kingdom, and to date, the participants are still being followed. Our study identifies that the heart failure (HF) incidence is greater among cancer survivors and that clinical factors, assessed using the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities-HF score (ARIC-HF), performed better in predicting HF incidence than genetic factors in the polygenic risk score for HF (PRS-HF). AUC = area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve; avg = average.

Although natriuretic peptides and/or echocardiography have value in predicting HF, an initial clinical assessment of HF risk would be a useful means of controlling the costs of these investigations in population-based strategies for preventing incident HF.15 Several HF risk prediction tools have been developed using traditional risk factors and have been applied in both clinical and research settings to assist clinicians in communicating HF risk to patients and initiating further investigations and eventual cardioprotective treatment.16, 17, 18 These results confirm that the ARIC-HF—which has the attraction of simplicity, as it is based on clinical rather than laboratory variables—is useful in a community setting among the noncancer population. Previous studies have shown that the addition of N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) improves model performance,19,20 although in our study, the discriminatory performance of the ARIC-HF was high, even in the absence of NT-proBNP results. However, in the prediction of incident HF among cancer survivors, conventional HF risk factors (including the ARIC-HF) seem insufficient. Standard scores do not account for a potential association of HF with cancer and potentially cardiotoxic therapies (including radio- and chemotherapy),21 which have a lasting impact despite the highest incidence of treatment-associated dysfunction during the first year after the completion of chemotherapy.22 A HF prediction score specific to cancer survivors may be of value.

Genotyping is feasible (obtained from saliva or blood), relatively inexpensive, needs to be done only once in a lifetime, and is increasingly used for selecting therapy in patients with cancer.23 PRS have been developed to assess genetic risk for a wide range of diseases,24 and they provide a level of predictive information that is clinically actionable, including with close monitoring and prophylactic measures.25 Integrating PRS into a risk prediction model should improve the accuracy of the model and provide patients with a more comprehensive risk assessment.26 The use of PRS for cardiovascular disease risk assessment was initially validated by Hippisley-Cox et al.26 In their work, a PRS was incorporated into the QRISK algorithm, ultimately improving the overall accuracy in predicting the risk for developing cardiovascular diseases. However, our study of HF risk showed that the ARIC-HF itself showed strong discriminatory performance, with an AUC of >0.80, but the integration of the PRS reduced its performance, implying that the PRS-HF is not a strong predictor of HF. This may be because cardiovascular disease has an important polygenic contribution, but HF risk is strongly influenced by environmental stimuli, for example, lifestyle, diet, and exercise.27 Previous work in this respect is inconsistent. A previous study investigating the performance of the PRS for coronary artery disease also showed that the PRS did not outperform risk prediction on the basis of a combination of clinical risk factors.28 The findings call into question whether specific prognostic value might be provided, as well as limitations, in the application of PRS in predicting HF occurrence.

The performance of PRS may not be transferable among different ethnicities, as reported in previous studies.29,30 This is due mainly to potential gene-environment interactions, the population structure from which the PRS was developed from and other genetic factors, such as linkage disequilibrium, risk variants, and allele frequencies. As such, we conducted a White-only analysis to evaluate if the PRS-HF would perform better than the entire population. The findings showed that the PRS remained a poor predictor of HF incidence. Hence, in the context of the prediction of HF incidence, genetic factors might not play a crucial role in HF prognosis, independent of patients’ ethnicity.

Although the combination of the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF did not demonstrate an improvement of the predictive performance for HF incidence, our final multivariable model comprising the PRS-HF along with multiple HF risk factors resulted in predictive accuracy that is significantly better than that obtained with the combination of the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF. This finding suggests that although the PRS-HF should not be integrated as an HF screening tool by itself, it could be useful if evaluated along with other clinical risk factors, such as age, sex, blood pressure, and comorbidities. The associations between conventional risk factors, including age, sex, comorbidities, blood pressure, smoking, and alcohol consumption, and HF incidence were significant, as expected. However, an increase in total cholesterol level was shown to be protective against HF incidence. This may be influenced by the protective effect from increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level (unadjusted sHR: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.67-0.71), and we lack information on non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level. Hyperlipidemia is associated with statin use, which is protective. Alternatively, it may be a false-positive association arising from multiple comparisons. As for the combination of the ARIC-HF and PRS-HF, the reduction in overall predictive accuracy shows that the PRS-HF introduces more ambiguity to the model of the ARIC-HF alone, which is also supported by the heat map (Supplemental Table 3).

Study limitations

Importantly, our study lacks key data on biomarkers, such as NT-proBNP and ST.2 These biomarkers are frequently assessed in the context of evaluating patients’ cardiac function in clinical setting and could improve the overall prognosis of HF incidence.

Second, the PRS-HF includes only common SNPs, which could potentially limit its overall prognostic value given the exclusion of certain rare SNPs that was found to be associated with HF occurrence. In addition, there may be a potential underestimation of disease frequency, including HF diagnoses, as this is captured via ICD-10 codes. Additionally, chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia, diagnosed in the primary care setting may not be captured. Finally, details of cancer therapy were not available for this study. Treatments such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy may be cardiotoxic. For instance, anthracyclines remain the most common chemotherapeutic agent to cause cancer treatment–related cardiomyopathy.31 Thoracic radiotherapy, which is a common treatment for patients with breast, lung, and esophageal cancer and lymphoma, may contribute to HF.32 Hence, missing such information would certainly limit the prognostic performance of HF scores. Nonetheless, the main effects of therapy are more likely to be early than late. Future studies should look into developing cancer-specific HF risk prediction that takes cancer survivors’ treatment histories into account.

Conclusions

The ARIC-HF demonstrates acceptable discriminative performance in HF prediction among noncancer population. The limitations of the PRS-HF in predicting incident HF (including failure to enhance the overall predictive performance of the ARIC-HF) warrant further investigation. In addition, neither the ARIC-HF nor the PRS-HF is strongly predictive of incident HF in cancer survivors. There is a need for a cancer-specific HF risk model to screen for survivors at risk for incident HF.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE AND PATIENT CARE: Our study demonstrates that within both cancer and noncancer populations, the genetic factors contributing to HF occurrence are not as important compared with clinical factors, emphasizing the importance of implementing the ARIC-HF as an HF screening tool in clinical settings.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: Future research should investigate the development of cancer-specific HF risk screening tools to improve HF prognosis among cancer survivors and allow the initiation of cardioprotective treatment.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

Dr Marwick is supported by an investigator grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council (2008129). All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For supplemental tables and figures, please see the online version of this paper.

Appendix

References

- 1.Henkel D.M., Redfield M.M., Weston S.A., Gerber Y., Roger V.L. Death in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2008;1(2):91–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.107.743146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal S.K., Chambless L.E., Ballantyne C.M., et al. Prediction of incident heart failure in general practice. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(4):422–429. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.964841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeFilippis A.P., Young R., Carrubba C.J., et al. An analysis of calibration and discrimination among multiple cardiovascular risk scores in a modern multiethnic cohort. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):266–275. doi: 10.7326/M14-1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pérez-López F.R., Larrad-Mur L., Kallen A., Chedraui P., Taylor H.S. Gender differences in cardiovascular disease: hormonal and biochemical influences. Reprod Sci. 2010;17(6):511–531. doi: 10.1177/1933719110367829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexandre J., Cautela J., Ederhy S., et al. Cardiovascular toxicity related to cancer treatment: a pragmatic approach to the American and European cardio-oncology guidelines. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(18) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi S.W., Mak T.S.-H., O’Reilly P.F. Tutorial: a guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nature Protoc. 2020;15(9):2759–2772. doi: 10.1038/s41596-020-0353-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y., Namba S., Lopera E., et al. Global biobank analyses provide lessons for developing polygenic risk scores across diverse cohorts. Cell Genom. 2023;3(1) doi: 10.1016/j.xgen.2022.100241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sudlow C., Gallacher J., Allen N., et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tzitzivacos D. International Classification of Diseases 10th Edition (ICD-10) CME SA J CPD. 2007;25(1):8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ge T., Chen C.-Y., Ni Y., Feng Y.-C.A., Smoller J.W. Polygenic prediction via Bayesian regression and continuous shrinkage priors. Nature Commun. 2019;10(1):1776. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09718-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang C.C., Chow C.C., Tellier L.C., Vattikuti S., Purcell S.M., Lee J.J. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4:7. doi: 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert S.A., Gil L., Jupp S., et al. The Polygenic Score Catalog as an open database for reproducibility and systematic evaluation. Nature Genet. 2021;53(4):420–425. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00783-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dignam J.J., Zhang Q., Kocherginsky M. The use and interpretation of competing risks regression models. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(8):2301–2308. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassanin E., Maj C., Klinkhammer H., Krawitz P., May P., Bobbili D.R. Assessing the performance of European-derived cardiometabolic polygenic risk scores in South-Asians and their interplay with family history. BMC Med Genom. 2023;16(1):164. doi: 10.1186/s12920-023-01598-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segar M.W., Jaeger B.C., Patel K.V., et al. Development and validation of machine learning–based race-specific models to predict 10-year risk of heart failure: a multicohort analysis. Circulation. 2021;143(24):2370–2383. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.053134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan Sadiya S., Ning H., Shah Sanjiv J., et al. 10-Year risk equations for incident heart failure in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(19):2388–2397. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler J., Kalogeropoulos A., Georgiopoulou V., et al. Incident heart failure prediction in the elderly. Circ Heart Fail. 2008;1(2):125–133. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.768457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tiwaskar SA, Gosavi R, Dubey R, et al. Comparison of prediction models for heart failure risk: a clinical perspective. Presented at: 2018 Fourth International Conference on Computing Communication Control and Automation (ICCUBEA); August 16-18, 2018.

- 19.Harjit C., David A.B., Colin O.W., et al. Heart failure risk prediction in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Heart. 2015;101(1):58. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nambi V., Liu X., Chambless L.E., et al. Troponin T and N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide: a biomarker approach to predict heart failure risk—the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Clin Chem. 2013;59(12):1802–1810. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.203638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finet J.E. Management of heart failure in cancer patients and cancer survivors. Heart Fail Clin. 2017;13(2):253–288. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cardinale D., Colombo A., Bacchiani G., et al. Early detection of anthracycline cardiotoxicity and improvement with heart failure therapy. Circulation. 2015;131(22):1981–1988. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wray N.R., Lin T., Austin J., et al. From basic science to clinical application of polygenic risk scores: a primer. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(1):101–109. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loh M., Chambers J.C. Polygenic risk scores for complex diseases: where are we now? Singapore Med J. 2023;64(1):88–89. doi: 10.4103/singaporemedj.SMJ-2021-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khera A.V., Chaffin M., Aragam K.G., et al. Genome-wide polygenic scores for common diseases identify individuals with risk equivalent to monogenic mutations. Nat Genet. 2018;50(9):1219–1224. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0183-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hippisley-Cox J., Coupland C., Brindle P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hajar R. Genetics in cardiovascular disease. Heart Views. 2020;21(1):55–56. doi: 10.4103/HEARTVIEWS.HEARTVIEWS_140_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inouye M., Abraham G., Nelson C.P., et al. Genomic risk prediction of coronary artery disease in 480,000 adults: implications for primary prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(16):1883–1893. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Privé F., Aschard H., Carmi S., et al. Portability of 245 polygenic scores when derived from the UK Biobank and applied to 9 ancestry groups from the same cohort. Am J Hum Genet. 2022;109(1):12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y., Willer C., Sanna S., Abecasis G. Genotype imputation. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:387–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Araujo-Gutierrez R., Ibarra-Cortez S.H., Estep J.D., et al. Incidence and outcomes of cancer treatment-related cardiomyopathy among referrals for advanced heart failure. Cardiooncology. 2018;4:3. doi: 10.1186/s40959-018-0029-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ritter A., Quartermaine C., Pierre-Charles J., et al. Cardiotoxicity of anti-cancer radiation therapy: a focus on heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2023;20:44–55. doi: 10.1007/s11897-023-00587-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.