Abstract

Blood pumps have been increasingly used in mechanically assisted circulation for ventricular assistance and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support or during cardiopulmonary bypass for cardiac surgery. However, there have always been common complications such as thrombosis, hemolysis, bleeding, and infection associated with current blood pumps in patients. The development of more biocompatible blood pumps still prevails during the past decades. As one of those newly developed pumps, the Breethe pump is a novel extracorporeal centrifugal blood pump with a hybrid magnetic and mechanical bearing with attempt to reduce device-induced blood trauma. To characterize the hydrodynamic and hemolytic performances of this novel pump and demonstrate its superior biocompatibility, we use a combined computational and experimental approach to compare the Breethe pump with the CentriMag and Rotaflow pumps in terms of flow features and hemolysis under an operating condition relevant to ECMO support (flow: 5 L/min, pressure head: ~350 mmHg). The computational results showed that the Breethe pump has a smaller area-averaged wall shear stress (WSS), a smaller volume with a scalar shear stress (SSS) level greater than 100 Pa and a lower device-generated hemolysis index compared to the CentriMag and Rotaflow pumps. The comparison of the calculated residence times among the three pumps indicated that the Breethe pump might have better washout. The experimental data from the in vitro hemolysis testing demonstrated that the Breethe pump has the lowest normalized hemolysis index (NIH) than the CentriMag and Rotaflow pumps. It can be concluded based on both the computational and experimental data that the Breethe pump is a viable pump for clinical use and it has better biocompatibility compared to the clinically accepted pumps.

Keywords: Computational fluid dynamics, centrifugal blood pumps, flow dynamics, hemolysis, shear stress

Introduction

Blood pumps have gained increasing attention in mechanically assisted circulation for ventricular assistance for cardiac failure or for respiratory or cardiopulmonary ECMO support or during cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) for cardiac surgery.1,2 Over the past several decades, a wide variety of mechanical blood pumps have been invented and evolved, including roller pumps, pulsatile displacement pumps, centrifugal flow pumps, and axial flow pumps.3 Among them, the roller pumps were once the most commonly used in ECMO4 but over the past years there has been a shift from the use of roller pumps to centrifugal pumps.5 However, with the increasing use of centrifugal blood pumps in ECMO circuits, some common complications such as thrombosis, hemolysis, bleeding, and infection are also reported to be associated with current centrifugal pumps used in ECMO patients.6 For example, the two commercialized blood pumps, CentriMag (Abbott, Chicago, IL, USA) and Rotaflow (Getinge, Gothenburg, Sweden) pumps, have been widely used in ECMO treatment while case reports with the CentriMag and RotaFlow pumps have described common postoperative complications including mediastinal bleeding requiring reoperation and the need for tracheostomy due to respiratory failure7,8; one report described 2 months of support using the RotaFlow in an infant with a dilated cardiomyopathy.9 From a pump design point of view, the CentriMag pump, when compared to the Rotaflow pump, has greater clearances between rotating and stationary parts which leads to lower shear stress.10 Therefore, there is always demand for the development of more optimal centrifugal blood pumps with better biocompatibility.

In order to develop a more biocompatible blood pump, an initial pump profile design is usually set up first followed by computational fluid dynamics (CFD) iterations for the pump optimization.11 During the optimization process, a bunch of simulation cases of the pumps with different number of impeller blades, leading/trailing edge angles/heights, volute sizes, cut-water angles, etc. are run and the trade-off between the required pressure head and the blood hemolysis level is considered to obtain the most optimal pump.12 The CFD simulation also reveals the blood flow field within the pump and help identify and minimize the unfavorable flow features such as vortex formation, flow recirculation, and stagnation points13 as those features will increase the blood residence time leading to a bad washout of the pump and are the potential causes of thrombus formation. Based on these design principles and considerations, a novel extracorporeal centrifugal blood pump (Breethe pump) has been developed with an attempt of reduced device-induced blood trauma and improved biocompatibility. However, the hydrodynamic and hemolytic performances of this novel pump have not been thoroughly studied in comparison with other centrifugal blood pumps and its superior biocompatibility needs to be verified. Therefore, in this study, we employed the combined computational and experimental method to investigate the flow feature and blood damage potentials of the Breethe pump and compare the numerical and experimental results with the CentriMag and Rotaflow pumps in terms of blood flow structure, shear stress levels, flow washout, and hemolysis index. The goal of this paper is to demonstrate the good biocompatibility of the Breethe pump and its viability for future clinical use.

Numerical and experimental methods

Pump descriptions

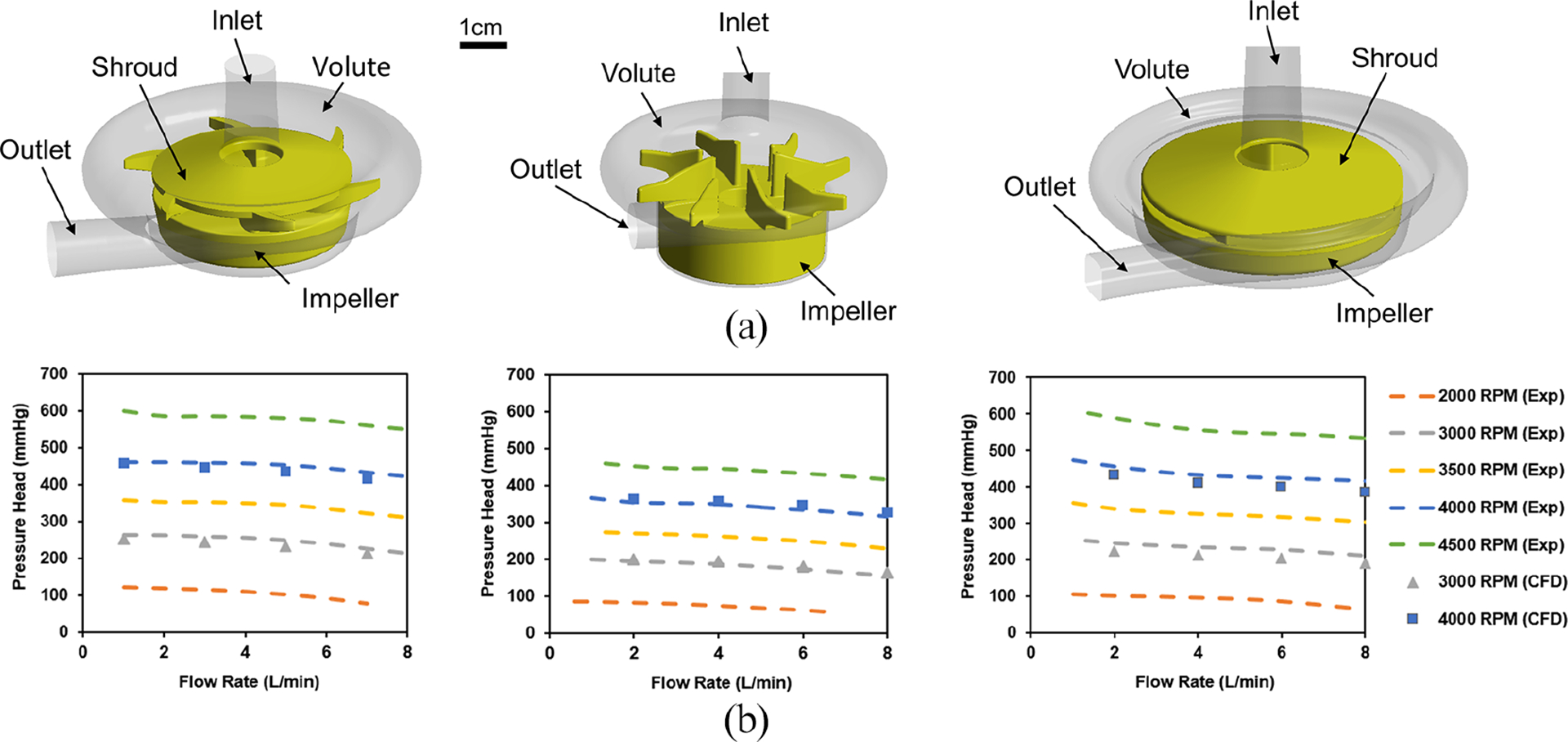

The Breethe pump (Breethe, Inc., Baltimore, MD) is a newly developed centrifugal pump featuring a single ball- and-cup hybrid magnetic/blood immersed bearing-supported impeller driven by a magnetically coupled motor drive (Figure 1(a)). A shrouded impeller with extended blades from the impeller hub and shroud is used. The primary flow path is from the inlet to the tangential outlet through the impeller blade passage between the hub and the shroud of the impeller. A U-shaped secondary flow path exists in the gap between the rotating impeller hub and the stationary pump housing (this type of flow path is also existing in the CentriMag and Rotaflow pumps14) and merges with the primary flow path through the central opening in the impeller. Permanent magnets are enclosed inside the impeller and coupled with the driving magnets which are fixed on an external pancake motor. The arrangement of the magnets enhances the stability of the rotary impeller and reduces the heat generated from the friction of the bearing. The Breethe pump weighs 49 g with a priming volume of 32 mL. The operational rotating speed of the Breethe pump is between 1000 and 5000 rpm, and the flow rate up to 10 L/min. Both the CentriMag and Rotaflow pumps have a similar primary flow path from the axial inlet to the tangential outlet (Figure 1(a)) and a secondary flow in the gap between the rotating impeller and the pump housing. The impeller of the CentriMag and Rotatflow pumps also has a central opening for the secondary flow path to merge with the primary flow path. The CentriMag pump has an open impeller with extended blades while the Rotaflow pump has a shrouded impeller. The CentriMag pump weighs 67.3 g with a priming volume of 31 mL. It can provide high blood flow rate up to 9.9 L/min with a typical rotating speed up to 5500 rpm. The Rotaflow pump weighs 61.3 g with a priming volume of 32 mL. It can provide high blood flow rate up to 9.9 L/min with a typical rotating speed between 0 and 5000 rpm. In addition, the CenrtiMag blood pump employs a bearingless impeller technology and it does not contain seals or bearings that are considered to be the potential cause of the thrombus formation.15 The Rotaflow pump is a shrouded impeller pump that employs a magnetically stabilized impeller on a monopivot and features a peg-top, one-point, sapphire bearing which were designed to lower friction.16

Figure 1.

(a) 3D CAD drawings of Breethe (left), CentriMag (middle), and Rotaflow (right) pumps and (b) measured versus CFD predicted pressure head of the Breethe (left), CentriMag (middle), and Rotaflow (right) pumps at different blood rates and rotational speeds.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis

The geometries of the three pumps were obtained from computer aided drawing (CAD) files or constructed by measuring the actual device components and create models through reverse engineering procedure. Both structured and unstructured mesh were used in the flow domain. The details of the meshing procedure can be found in previous publications.17 Numerical simulations of flow inside the three pumps were conducted by using the commercial CFD package (Fluent 19.2, ANSYS, Inc, Canosburg, PA). The flow field was obtained by numerically solving the flow fluid governing equations using the unstructured-mesh finite-volume-based commercial CFD solver FLUENT 19.2 (ANSYS Inc, Canonsburg, PA). Constant mass flow rate and 0 pressure boundary conditions were specified at the pump inlets and outlets, respectively. The walls of the three pumps were assumed to be rigid and no-slip. Blood was considered as an incompressible Newtonian fluid with the density of 1050 kg/m3 and viscosity of 0.0035 kg/m∙s. The Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure Linked Equations (SIMPLE) pressure-velocity coupling scheme with second order accuracy was used to solve all fluid governing equations. The Menter’s Shear Stress Transport (SST) k–ω model was used. Based on the suggested normal operating condition of the blood pumps,18 the volumetric flow rate of 5 L/min was prescribed as the inlet boundary condition and the pump pressure head was controlled at around 350 mmHg for numerical comparisons. The corresponding rotating speeds of the Breethe, CentriMag, and Rotaflow pumps were set as 3600, 4000, and 3600 rpm, respectively. The rotation of the pump impeller was modeled by using the sliding mesh approach. A mesh sensitivity analysis was conducted to ensure that the simulation results were independent of further mesh refinement. More details of the mesh sensitivity process can be found elsewhere.17 The final number of elements determined for Breethe, CentriMag, and Rotaflow pumps were 11.4, 7.3, and 9.4 million, respectively. After the simulations converge, shear stress fields, residential time fields, and hemolysis indices can be calculated form the solved flow fields.

Modeling of shear stress, residence time, and hemolysis

To assess the potential damaging effect of the high shear stress inside the blood pumps, a viscous scalar shear stress was calculated based on the CFD solved flow fields.19 The residence time physically represents the length of time that blood has been in the pumps since it enters the inlet (in seconds) and it was calculated by using the Eulerian scalar transport equation.20 The pump with large residence time indicates bad washout. Hemolysis potentials of the pumps are estimated by using the hemolysis index (HI) (the percentage change in plasma-free hemoglobin (PFH) relative to the total hemoglobin).20

In vitro hemolysis testing

A circulatory flow loop21 with ovine blood was constructed to evaluate the hemolytic performance of the three blood pumps. The tests were conducted following the protocol for assessment of hemolysis in continuous flow blood as suggested by the American Society of Testing and Materials (ASTM F1841–19).22 All the hemolysis tests were carried out with the flow rate of 5.0 ± 0.2 L/min and the pump pressure head of 350 ± 20 mmHg. The blood reservoir was immersed in a water bath to maintain the constant blood temperature of 37°C ± 1°C. The volumetric flow rates were measured by an ultrasonic flow probe (model 9PXL, Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY) and the Transonic T410 flow meter (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY). The pump inlet and outlet pressures were measured by a calibrated piezoelectric pressure transducer (model 1502B01EZ5V20GPSI, PCB Piezotronics, Inc., Depew, NY).

Fresh ovine blood was collected from a local slaughter-house. Heparin with the concentration of 10 U/1 mL blood was added to prevent the blood from coagulation. The collected blood was filtered with a blood transfusion filter (PALL Biomedical, Fajardo, Puerto Rico) and Baytril solution (Bayer Corporation, Leverkusen, Germany) was added as an antibiotic (final concentration: 100 mg/mL). The filtered blood was then conditioned using phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) to achieve a hematocrit level of 30% ± 2%. The total plasma protein was adjusted to be above 5.0 g/dL. The blood pH level was maintained at 7.4 ± 0.1 throughout the 6-h experiment by adding bicarbonate solution.

Each mock circulation loop was filled with 0.5 L processed blood. Baseline (prior to the circulation) and hourly samples after circulation initiation were collected from the loop. The plasma of the collected blood samples was collected for the PFH measurement. The details of blood sample process and PFH measurement can be found in our previous publication.21 The normalized index of hemolysis (NIH) was calculated based on the equation provided by ASTM F1841–19.22

Results

Hydrodynamic performance

A set of rotating speeds and flow rates for the Breethe, CentriMag, and Rotaflow pumps were used for simulations. The CFD models were assessed by comparing the numerical prediction of pressure head of each pump with experimental measurement. The simulated and experimentally measured pressure versus flow curves (HQ curves) of the three pumps are shown in Figure1(b). The pressure heads (ΔP) generated by the three blood pumps under four flow rates at two rotational speeds were simulated. The numerically obtained ΔP values of the three blood pumps agree well with the experimentally measured data. The relative error for each case is less than 10%. This indicated that the established CFD model can be used for further simulation and comparison.

Flow features

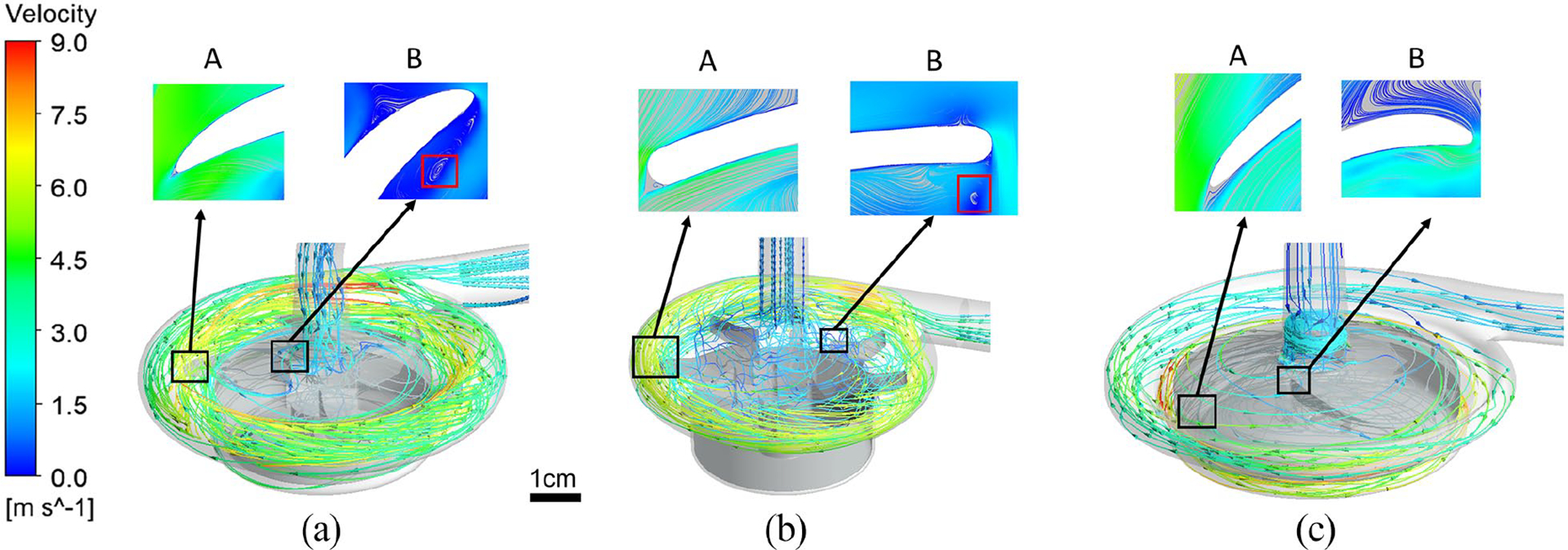

All three centrifugal pumps have overall similar flow patterns, but different detailed features. Three flow paths exist in the pump chamber. Blood enter from the inlet to the central hole of the pump impeller. Under the action of centrifugal forces, the blood is accelerated when moving radially along the impeller blade and reached the maximum velocity to enter the peripheral volute and then exit at the outlet. The primary flow path lies from the axial inlet to the tangential outlet through the impeller blade passage between the impeller shroud and impeller hub. As expected, a secondary flow path exists in the gap between the rotating impeller hub and the pump housing and merges with the primary flow path in the central opening of the impeller. Another secondary flow path exits in the flow domain between the top housing wall and the shroud surface for the Breethe and Rotaflow pump or between the top housing wall and the axial tip of the impeller blades for the CentriMag pump. In all the three pumps a small areas of flow separations were noted at the trailing edge tips of the impeller blades (Figure 2(a)–(c), marker A). For the Breethe and CentriMag pumps, recirculation flows were observed at the leading edges of their impeller blades (Figure 2(a) and (b), marker B).

Figure 2.

Streamlines for the (a) Breethe, (b) CentriMag, and (c) Rotaflow blood pumps under the condition of 350 mmHg pressure head and 5 L/min flow rate.

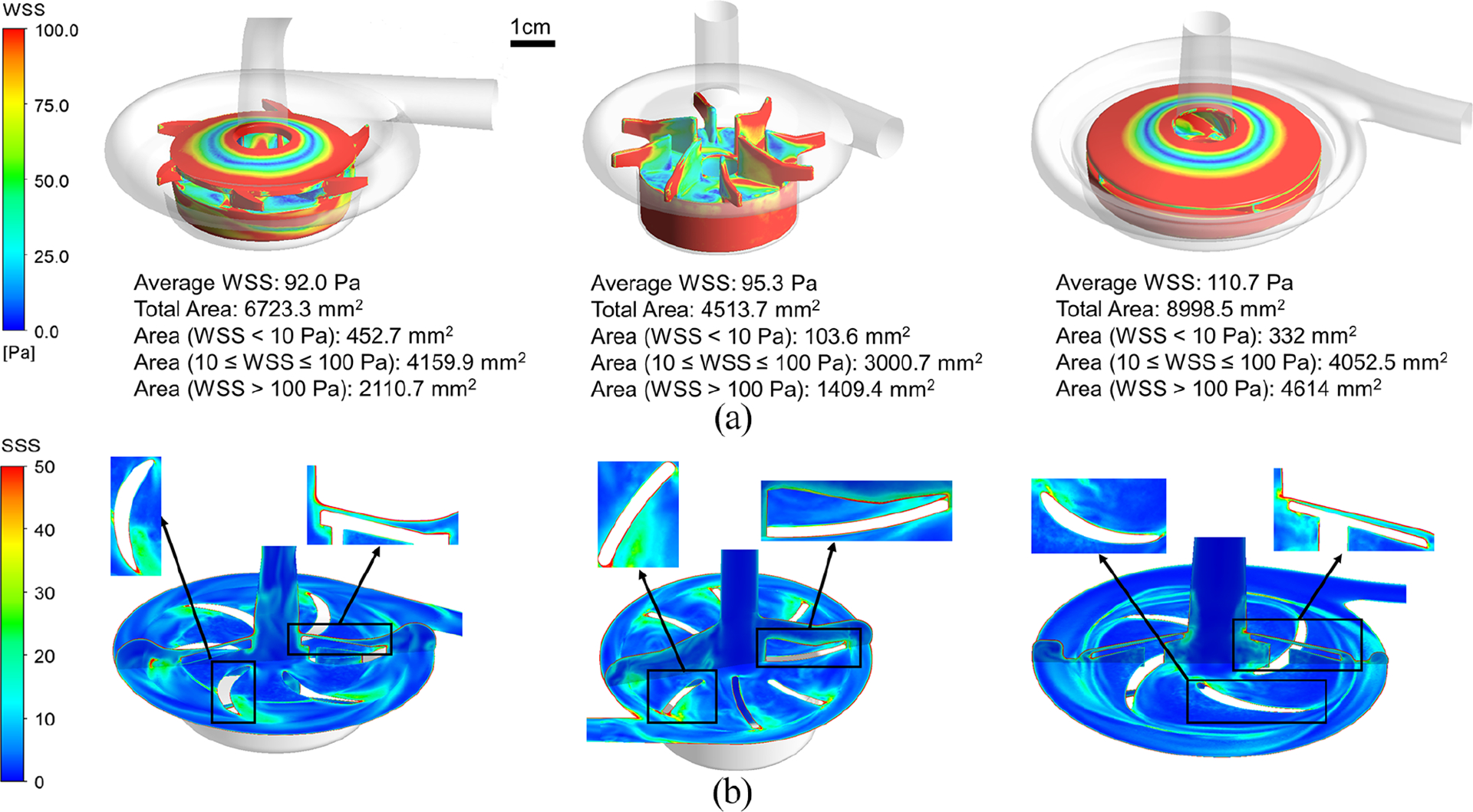

The wall shear stress (WSS) distributions on the impeller surfaces of the three blood pumps are shown in Figure3(a). The WSS level was classified into three levels based on suggested impacts on blood cells and proteins that (1) WSS < 10 Pa, which is considered as the physiological shear stress (PSS); (2)10 Pa ⩽ WSS ⩽ 100 Pa, which may cause high-molecular-weight (HMW) VWF (von Willebrand factor) degeneration and platelet activation; (3) WSS > 100 Pa, which represents the non-physiological shear stress (NPSS) that has been demonstrated to induce damage on blood components including blood cells and proteins.19 Recent studies have also reported that NPSS could induce paradoxical effect. In one hand, NPSS could induce remarkable platelet activation even with very short exposure time. The excessive activation of platelets can promote further recruitment of additional platelets to adhesion and aggregation at the site of vascular injury. Although platelet activation is one critical step for hemostasis, overactivated platelets in bloodstream may cause disorders of hemostasis leading to the increased risk of thrombosis. However, on the other hand, NPSS can also induce the loss of platelet receptors and high molecular weight multimers (HMWMs) of von Willebrand factor (vWF) impairing physiological hemostasis, and increase the potential for bleeding.23 As shown in Figure 3(a), the NPSS (colored in red) are observed at the outer blade tip surfaces of the three pumps. For the Breethe and Rotaflow pumps with a shrouded impeller, NPSS are also observed on their shroud surfaces. Quantitatively, the Breethe pump had a relatively smaller area-averaged average WSS (92 Pa) compared with the CentriMag (95.3 Pa) and Rotaflow (110.7 Pa) pumps. More specifically, the Breethe, CentriMag, and Rotaflow pump impellers had areas of 452.7, 103.6, and 332 mm2 with WSS under 10 Pa, respectively. For WSS between 10 and 100 Pa, the areas of Breethe, CentriMag, and Rotaflow pump impellers were 4159.9, 3000.7, and 4052.5 mm2, respectively. For WSS larger than 100 Pa, the corresponding areas of the three pumps were 2110.7, 1409.4, and 4614 mm2.

Figure 3.

Stress distribution comparison of: (a) the wall shear stress and (b) the scalar shear stress between the Breethe (left), CentriMag (middle), and Rotaflow (right) pumps under the condition of 350 mmHg pressure head and 5 L/min flow rate.

Shear stress field and residence time

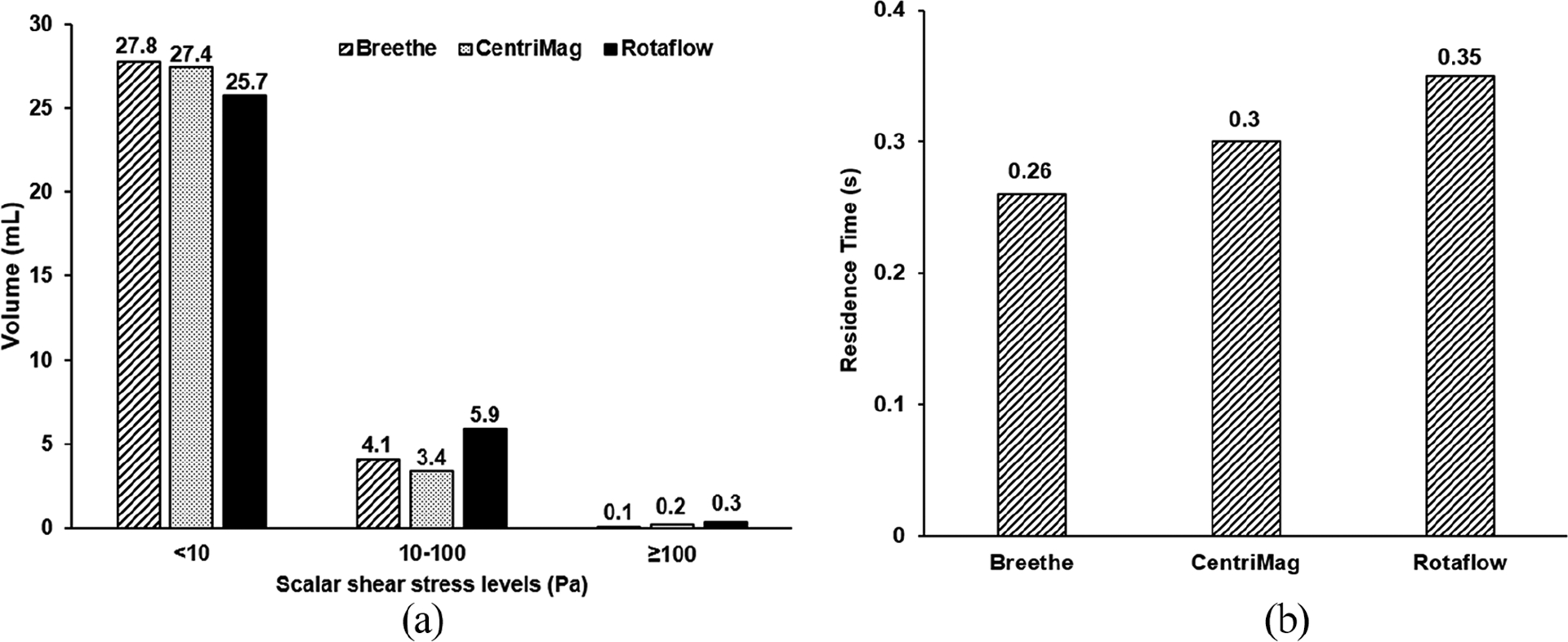

The scalar shear stress (SSS) distributions on a vertical midplane and a horizontal plane across the impeller blades of the three pumps are presented in Figure 3(b). High SSS appeared at the trailing edge of the impeller blades and the primary and secondary narrow flow channels. The volumes of the blood exposed to different levels of SSS are shown in Figure 4(a).The majority of the blood volumes in all three pumps experienced the SSS less than 10 Pa. The Breethe pump has the smallest volume of 0.1 mL with SSS greater than 100 Pa (NPSS) while the CentriMag pump has the lowest volume of 3.4 mL with SSS between 10 and 100 Pa. The volume-averaged SSS for the Breethe, CentriMag, and Rotaflow pumps were 9.6, 9.3, and 12.6 Pa.

Figure 4.

Comparison of: (a) scalar shear stress and (b) residence time between the Breethe, CentriMag and Rotaflow pumps under the condition of 350 mmHg pressure head and 5 L/min flow rate.

The velocity-weighted average residence times defined as the difference between the flow times measured at the outlets and inlets of the Breethe, CentriMag, and Rotaflow pumps under the tested operating condition (pressure head of 350 mmHg and flow rate of 5 L/min) were 0.26, 0.3, and 0.35 s, respectively. The residence time histograms of the three pumps are given in Figure 4(b). Considering the three pumps had almost the same priming volumes, the Breethe pump might have better washout among the three pumps while the difference is not significant.

Hemolysis analysis

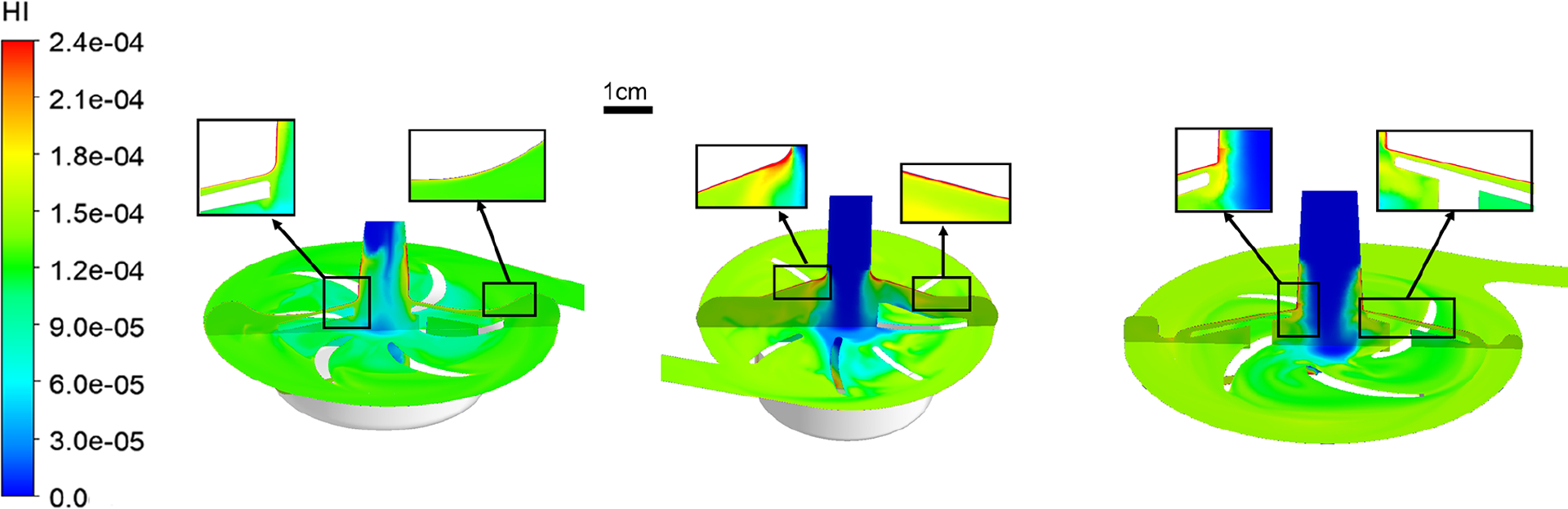

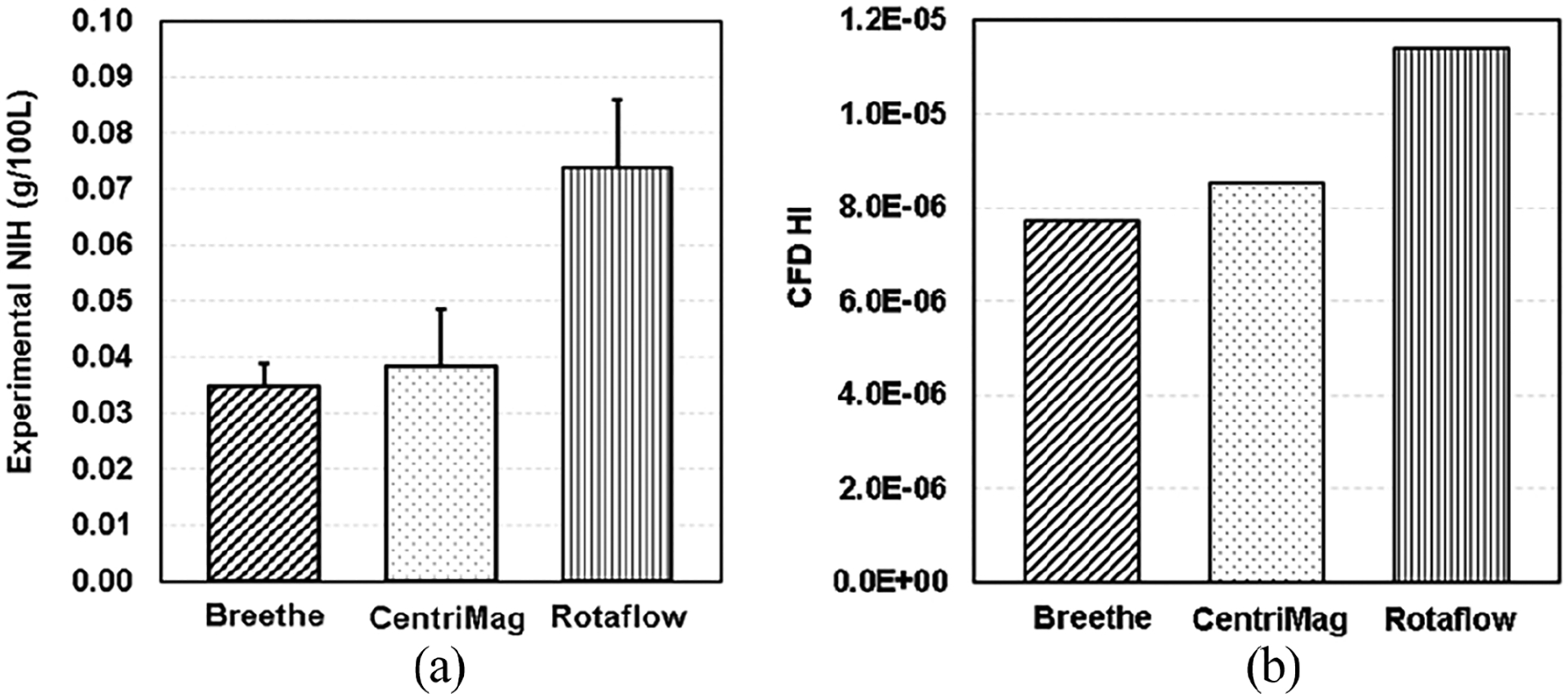

The calculated hemolysis index (HI) distributions on the mid and meridian planes of the three blood pumps are presented in Figure 5. It was observed that there are high HI existing at the inlet or upper housing surfaces of the three pumps due to the high SSS in these regions (Figure 3(b)). Overall, the Breethe pump generates relatively lower HI compared with the CentriMag and Rotaflow pumps. The HI levels at the outlet of the three pumps are shown in Figure 6(b). The Breethe pump generates a relatively low hemolysis index compared with those generated by the CentriMag and Rotaflow pumps (7.73 × 10−6 vs 8.55 × 10−6 and 1.14 × 10−5). These computationally predicted HI levels are consistent with the experimentally measured NIH values for the three pumps as shown in Figure 6(a). The NIH generated by the Breethe pump was lowest among the three pumps (0.0347 ± 0.0041 g/100 L vs 0.0385 ± 0.0101 g/100 L and 0.0739 ± 0.0041 g/100 L).

Figure 5.

Hemolysis index (HI) contours of the Breethe (left), CentriMag (middle), and Rotaflow (right) pumps with the condition of 350 mmHg pressure head and 5 L/min flow rate.

Figure 6.

(a) Experimental NIH (g/100 L) and (b) CFD predicted HI of the Breethe, CentriMag, and Rotaflow pumps with the condition of 350 mmHg pressure head and 5 L/min flow rate.

Discussion

The flow dynamics of the newly developed centrifugal Breethe pump operated under a clinically relevant operating condition for ECMO support (pressure head of 350 mmHg and flow rate of 5 L/min) was computationally analyzed with two clinically used pumps (CentriMag and Rotaflow). The flow features (velocity field, wall and bulk scalar shear stress distributions) and device-induced hemolysis within the three pumps were assessed. The computationally predicted area-averaged WSS of the Breethe pump was relatively smaller than those of the CentriMag and Rotaflow under the same operating condition. This could be attributed to the unique impeller design (Figure 1(a)) of the Breethe pump. Compared with the CentriMag, the Breethe pump has a shorter impeller hub, and larger gap between the housing wall and the impeller hub. The blade height of the Rotaflow pump is smaller than that of the Breethe pump, resulting a narrow gap between its shroud inner surface and the top surface of the impeller hub, which could result in higher shear wall stress (Figure 3(a)). The computationally predicted scalar shear stress distributions indicated that the overall bulk SSS in the Breethe pump was almost the same as the CentriMag pump and was lower than the Rotaflow pump.

Consistent with the shear stress assessment, the level of HI produced by the Breethe pump was lower compared with the CentriMag and Rotaflow pumps. The numerically calculated HI is dependent on both exposure time and SSS. The three pumps have almost similar priming volume and exposure time and were evaluated under the same operating condition. It is therefore anticipated that the structural design of the Breethe pump with lower WSS and overall SSS should help lower the hemolysis level. This computationally prediction was confirmed by our experimentally measured NIH values for three pumps.

Although the computationally predicted HI using the CFD approach were not directly converted to corresponding experimental values for CFD model validation since our previous study20 showed that both the Eulerian scalar transport and Lagrangian models failed to reproduce the experimental results, it is still useful to use those methods to give relative comparisons of hemolysis in different blood pumps and combine the numerical results with experimental ones to rank devices. The experimental and computational data about the CentriMag and Rotaflow pumps have also been reported by other researchers. For example, Sobieski et al.24 also conducted hemolysis tests but their experimental results showed that the Rotaflow pump had a lower NIH compared to the CentriMag pump. This contradicting result could be attributed to that: (1) they conducted their tests only twice (n = 2) for each pump and the results were of less statistical significance when compared to ours (n > 6); (2) they used bovine blood instead of ovine blood in their case and it was reported from our previous study25 that there is the differences in sensitivity (to shear stress and exposure time) of RBCs of different animal species; (3) the operational conditions of the two pumps in their study were different (CentriMag: 3425 rpm, 4.2 L/min; Rotaflow: 3000 rpm, 4.17 L/min); (4) there was a lack of simulation results in their study to show the blood features of the two pumps and thus support the experimental data.

Conclusion

Combined CFD-based computational and experimental investigations were conducted to characterize the hemodynamic and hemolytic performance of the newly developed Breethe centrifugal blood pump and two commercially available pumps (CentriMag and Rotaflow) under the clinically relevant operating condition. The comparison results demonstrated that the Breethe pump has relatively smaller average WSS and volume with SSS greater than 100 Pa compared to the CentriMag and Rotaflow pumps. The simulated residence time results showed that the Breethe pump might have better washout among the three pumps. The large gap (between the impeller shroud and the impeller body) design of the Breethe pump also result in a smaller shear stress distributed on the impeller surface when it is compared with the Rotaflow pump. In addition, both the experimental data and simulation results suggested that the Breethe pump has a better hemolytic performance than the CentriMag and Rotaflow pumps and it may be a viable pump for clinical use.

It should also be noted that centrifugal blood pumps inevitably generate heat especially when they are driven at high rotational speeds. Depending on the pump head and motor configurations, the heat may originate from the motor by conduction, hydraulic energy loss, and mechanical friction between the shaft and seal or in the bearing system. The blood temperature change induced by the heat generation may affect the blood neutralization in terms of its pH level and thus alters the oxygen and carbon dioxide solubilities in blood, which consequently affects the gas exchange performance of oxygenators used in ECMO circuits. In our study, considering that the three pumps employ either single-contact pivot bearing or bearingless support and non-contact magnetic coupling drive, the pump heat generation has been neglected but further comparative study of the three pumps in terms of heat generation and its effect on blood neutralization is still necessary.

There are some limitations of current study. First, the hemolysis model used in current CFD simulations is a simple power-law model which numerical predictions failed to be directly compared with experimental data. More sophisticated and physically-based models are required to provide better predictions. Second, because all the three pumps were developed to be paired with oxygenators and used in ECMO circuits, the current in vitro experiments can be extended to include oxygenators and thus the interaction effect between pump and oxygenator can be investigated. This pump-oxygenator loop study will be considered in the future works. Third, in addition to hemolysis, platelet activation that is thought to be related to thrombus formation can also be induced by the high shear stress produced by the rotational pump impeller. However, this device-induced platelet activation is not measured in the in vitro experiments. For future experimental study, platelet activation tests can be included for a better comparison of pumps.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The work reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (Award Numbers: R01HL118372 and R01HL141817).

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Z.J.W. and B.P.G. disclose ownership interest in Breethe, Inc. J. Z., B.P. G, and Z.J.W. disclose intellectual property for ECMO systems and the blood pumps.

References

- 1.Kirklin JK, Pagani FD, Kormos RL, et al. Eighth annual INTERMACS report: special focus on framing the impact of adverse events. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017; 36: 1080–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simmonds MJ, Watanabe N, Nandakumar D, et al. Chapter 19. Blood-device interaction. In: Gregory SD, Stevens MC and Fraser JF (eds) Mechanical circulatory and respiratory support. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier, 2018, pp.597–626. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang TQ, Hsu SY, Dahiya A, et al. Numerical modeling of pulsatile blood flow through a mini-oxygenator in artificial lungs. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2021; 208: 106241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawson S, Ellis C, Butler K, et al. Neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation devices, techniques and team roles: 2011 survey results of the United States’ Extracorporeal Life Support Organization centers. J Extra Corpor Technol 2011; 43(4): 236–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Datt B, Nguyen MB, Plancher G, et al. The impact of roller pump vs. centrifugal pump on homologous blood transfusion in pediatric cardiac surgery. J Extra Corpor Technol 2017; 49(1): 36–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sniderman J, Monagle P, Annich GM, et al. Hematologic concerns in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2020; 4: 455–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joshi A, Mehta V, Hasan J, et al. Outcome of centriMag extracorporeal mechanical circulatory support use in critical cardiogenic shock (INTERMACS 1) patients. J Heart Lung Transplant 2021; 40(4): S410. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khani-Hanjani A, Loor G, Chamogeorgakis T, et al. Case series using the ROTAFLOW system as a temporary right ventricular assist device after HeartMate II implantation. ASAIO J 2013; 59(4): 456–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inoue T, Nishimura T, Murakami A, et al. Left ventricular assist device support with a centrifugal pump for 2 months in a 5-kg child. J Artif Organs 2011; 14(3): 253–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan CH, Pieper IL, Hambly R, et al. The CentriMag centrifugal blood pump as a benchmark for in vitro testing of hemocompatibility in implantable ventricular assist devices. Artif Organs 2015; 39(2): 93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu P, Huo J, Dai W, et al. On the optimization of a centrifugal maglev blood pump through design variations. Front Physiol 2021; 12: 699891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghadimi B, Nejat A, Nourbakhsh SA, et al. Shape optimization of a centrifugal blood pump by coupling CFD with metamodel-assisted genetic algorithm. J Artif Organs 2019; 22: 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Good BC and Manning KB. Computational modeling of the Food and Drug Administration’s benchmark centrifugal blood pump. Artif Organs 2020; 44: E263–E276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Gellman B, Koert A, et al. Computational and experimental evaluation of the fluid dynamics and hemocompatibility of the CentriMag blood pump. Artif Organs 2006; 30(3): 168–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ignat T, Desai A, Hoschtitzky A, et al. Cardiohelp system use in school age children and adolescents at a center with interfacility mobile extracorporeal membrane oxygenation capability. Int J Artif Organs. Epub ahead of print 2 February 2021. DOI: 10.1177/0391398821990659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guan Y, Su X, McCoach R, et al. Mechanical performance comparison between RotaFlow and CentriMag centrifugal blood pumps in an adult ECLS model. Perfusion 2010; 25: 71–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J, Zhang P, Fraser KH, et al. Comparison and experimental validation of fluid dynamic numerical models for a clinical ventricular assist device. Artif Organs 2013; 37: 380–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ASTM F1830–19. Standard practice for collection and preparation of blood for dynamic in vitro evaluation of hemolysis in blood pumps. 2019. American Society for Testing and Materials, West Conshohocken, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Z, Jena SK, Giridharan GA, et al. Shear stress and blood trauma under constant and pulse-modulated speed CF-VAD operations: CFD analysis of the HVAD. Med Biol Eng Comput 2019; 57: 807–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taskin ME, Fraser KH, Zhang T, et al. Evaluation of Eulerian and Lagrangian models for hemolysis estimation. ASAIO J 2012; 58: 363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berk Z, Zhang J, Chen Z, et al. , Evaluation of in vitro hemolysis and platelet activation of a newly developed maglev LVAD and two clinically used LVADs with human blood. Artif Organs 2019; 43(9): 870–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ASTM F1841–19. Standard practice for assessment of hemolysis in continuous flow blood pumps. 2019. American Society for Testing and Materials, West Conshohocken, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Z, Mondal NK, Ding J, et al. Paradoxical effect of non-physiological shear stress on platelets and von Willebrand factor. Artif Organs 2016; 40(7): 659–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sobieski MA, Giridharan GA, Ising M, et al. Blood trauma testing of CentriMag and RotaFlow centrifugal flow devices: a pilot study. Artif Organs 2012; 36(8): 677–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding J, Niu S, Chen Z, et al. Shear-induced hemolysis: species differences. Artif Organs 2015, 39(9):795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]