Abstract

Background

In 2024 in the United States there is an attack on diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives within education. Politics notwithstanding, medical school curricula that are current and structured to train the next generation of physicians to adhere to our profession’s highest values of fairness, humanity, and scientific excellence are of utmost importance to health care quality and innovation worldwide. Whereas the number of anti-racism, diversity, equity, and inclusion (ARDEI) curricular innovations have increased, there is a dearth of published longitudinal health equity curriculum models. In this article, we describe our school’s curricular mapping process toward the longitudinal integration of ARDEI learning objectives across 4 years and ultimately creation of an ARDEI medical education program objective (MEPO) domain.

Methods

Medical students and curricular faculty leaders developed 10 anti-racism learning objectives to create an ARDEI MEPO domain encompassing three ARDEI learning objectives.

Results

A pilot survey indicates that medical students who have experienced this curriculum are aware of the longitudinal nature of the ARDEI curriculum and endorse its effectiveness.

Conclusions

A longitudinal health equity and justice curriculum with well-defined anti-racist objectives that is (a) based within a supportive learning environment, (b) bolstered by trusted, structured avenues for student feedback and (c) amended with iterative revisions is a promising model to ensure that medical students are equipped to effectively address health inequities and deliver the highest quality of care for all patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-024-06235-y.

Keywords: Health equity, Anti-racism, Curricular mapping, Curriculum, Undergraduate medical education

Background

In 2024 in the United States (US) there is an attack on anti-racist, diversity, equity, and inclusion (ARDEI) initiatives in education [1]. Long-overdue curricular adjustments that are urgently needed to increase scientific accuracy, promote learning environment inclusion, and decrease systematic disenfranchisement of marginalized people in health education have been misrepresented as elements of a political ‘woke’ agenda [2]. Politics notwithstanding, health inequities are all too real, as evidenced by decades of scholarship documenting health disparities fueled by structural inequities that disproportionately harm historically marginalized populations. Fortunately, ARDEI curricular innovations being implemented at many medical schools hold promise for a more equitable, rigorous, and inclusive future for healthcare locally and globally [3].

Within ARDEI curricula, stepwise learning and repetitive practice opportunities are needed to provide learners with the knowledge and skills required to understand and change current drivers of health inequities [4–7]. Curricular roadmaps and innovations are increasingly available; however, published models of longitudinal curricula that scaffold skills across the 4 years of medical school are few. This article aims to fill this gap by outlining our school’s 4-year curricular mapping process toward the integration of ARDEI learning objectives and ultimately creation of an ARDEI medical education program objective (MEPO) domain.

Methods

During the 2020 US uprising for Black lives and concurrent increased awareness of national and global COVID-19 health inequities, our school set out to develop a comprehensive longitudinal ARDEI curriculum, spearheaded by students and bolstered by recommendations from our school’s Anti-Racism Task Force report [8]. The goal of this innovative curricular mapping was to discern ARDEI gaps in our program, engage faculty, and identify opportunities for sustainable curriculum development.

Building on existing US educational frameworks for structural and cultural competence, including the Association of American Medical College’s (AAMC) Tool for Assessing Cultural Competence Training (TACCT) [9], and Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) [10] and American College of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) DEI competencies [11], the team’s curricular goals were several. First, we recognized the need to build the curriculum upon a groundwork of psychological safety within our learning environment, which is a central tenet of learning in a competency-based medical education (CBME) framework [12, 13]. A second major goal related to deconstructing the racial essentialism that taints science and medicine both historically and in the present. Third, we focused on bolstering student skills toward active engagement in clinical and structural change toward enhancement of excellence and equity in healthcare and scientific discovery.

Setting & participants

In Spring 2020, faculty and administrative leaders at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons (VP&S,) a four-year, urban medical school in the Northeastern US, made a number of commitments to anti-racism [8, 14]. One was creation of a faculty leadership position, Director of Equity and Justice (E&J) (author HC), within curricular affairs and linked to annual funding for five medical student E&J fellows. Additionally, faculty-student partnerships launched several urgently needed curricular enhancements to add critical content and strengthen learning environment psychological safety related to anti-racism discussions. To do so, we crafted student and faculty learning opportunities and structures to bolster growth mindset, student-faculty partnerships, and civil discourse regarding difficult topics such as systemic racism. These efforts included curricular initiatives to center skills that promote belongingness for all, particularly those underrepresented in medicine, as these are essential to wellness, high-functioning diverse teams, and are key to fostering cutting-edge scientific innovation [15].

Concomitantly, over 100 faculty leaders participated in longitudinal educational opportunities; also, individual bias-reduction consultation for educators was and continues to be widely utilized (> 50 consultations in academic year 2022–2023). Soon after these urgent initiatives were in place, the curricular mapping process began.

Identifying conceptual frameworks

Curricular mapping began using a backward design framework [16], with development of 10 ARDEI learning objectives. Several conceptual frameworks guided learning objective development, including the seminal schema published in 2020 by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Group on Diversity and Inclusion (GDI) and Group on Faculty Affairs (GFA) [6] who recommended a pedagogy of anti-racism learning conceptualized as a pyramid with foundational awareness at the base of the pyramid, knowledge in the middle, and action-oriented leadership at the apex. We modeled our curriculum after this pyramid and added the concepts of both psychological safety and brave spaces [12] as the grounding on which the pyramid must be built. (Scholars conceptualize brave spaces of learning as those that merge psychological safety with encouragement for students to engage with ideas and skills that may be uncomfortable, with the understanding that discomfort may precipitate learning [17, 18].) The AAMC draft (later finalized) DEI competencies offered invaluable additional core conceptual support to our curriculum mapping journey [19]. These AAMC guidelines cover 3 domains – Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion – and catalog demonstrable competencies for medical professionals at each stage of training: beginning residency, entering practice, and faculty educator. Similarly useful in structuring our curriculum from awareness and knowledge to action-oriented skills was the 2021 anti-racism framework developed by Camara Jones: See, Name, Understand, and Act [20].

Building learning objectives

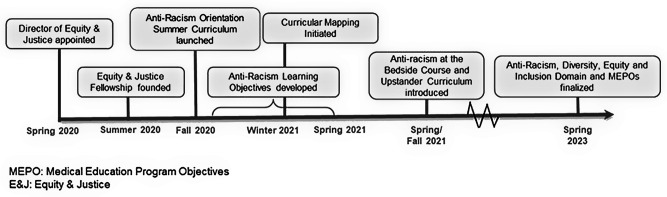

The equity and justice team used the domains of the AAMC DEI competencies and the developmental progression of the AAMC GDI/GFA framework as a starting point. These were complemented by relevant aspects of benchmarks from the TACCT, LCME, and ACGME and edited to eliminate redundancy and emphasize institutional priorities, to generate 10 draft ARDEI learning objectives in Fall of 2020. See Fig. 1 for key contributors to the ARDEI MEPO domain.

Fig. 1.

Anti-racism, diversity, equity, and inclusion MEPO domain: guiding frameworks and policies

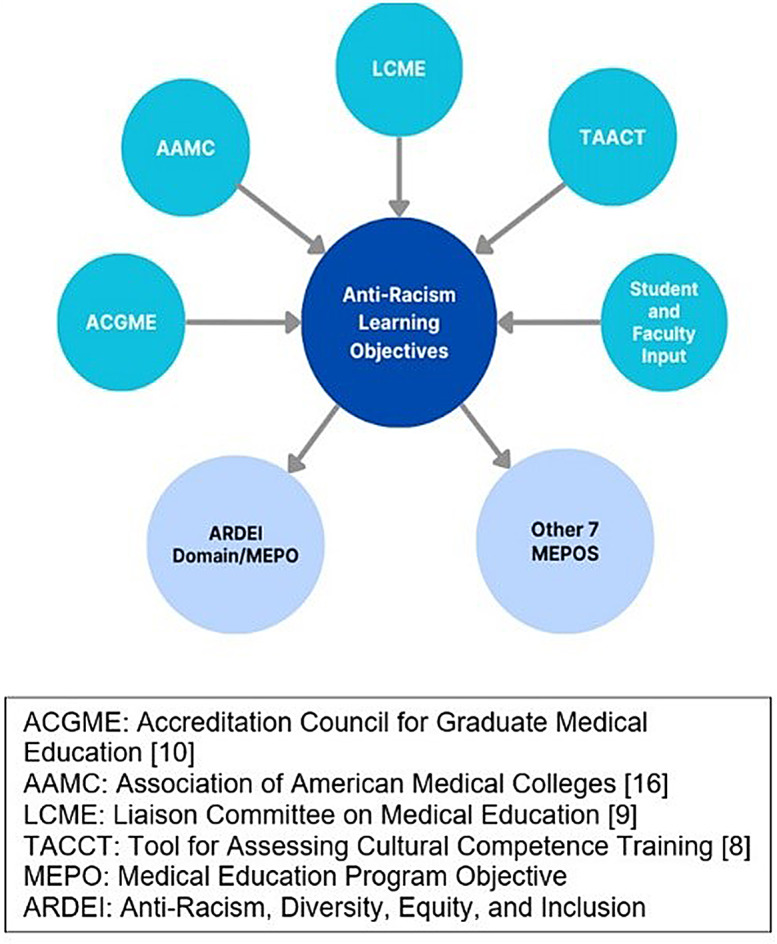

Subsequent months were spent iteratively meeting with education leaders, including course and clerkship directors and finally our central curriculum committee, to gain perspectives, buy-in, and simultaneously map curricular activities. In fall 2022, during our school’s curricular revision process, the 10 ARDEI learning objectives provided a basis for development of the school’s new MEPOs, described below. The school’s central curriculum committee formally adopted the new MEPOs in spring 2023. See Fig. 2 for ARDEI MEPO domain creation timeline.

Fig. 2.

Timeline of anti-racism, diversity, equity, and inclusion MEPO domain development

Mapping the curriculum

Following iterative development of 10 ARDEI learning objectives by students and faculty educators, the E&J medical student fellows and director mapped the learning objectives to the curriculum, meeting with course and clerkship directors, reviewing preclinical and/or clinical course outlines, lecture objectives, seminar foci, and assessment tools. The review included analysis of 445 pre-clinical lectures, > 24 courses, 6 core clerkships, electives, and sub-internships. See supplemental materials 2 for VP&S Four-Year Equity and Justice Curriculum Activities Mapped by Learning Objective.

Fortifying the curriculum

To strengthen curricular longitudinality and address urgent content gaps, we added several foundational sessions. See supplemental materials 3 for curricular specifics.

Pre-matriculation summer reading curriculum

We first initiated an anti-racism pre-matriculation summer reading curriculum, including diverse texts designed to cover a broad topic range including a history of racism in medicine, racial essentialism, structural competency, health disparities, and implicit bias. These readings are debriefed longitudinally throughout the first year, within courses such as genetics, cardiology, and the longitudinal sociobehavioral medicine course.

This pre-matriculation curriculum not only introduced students to many foundational topics, but also laid the groundwork for community conversations about racism. As previously mentioned, psychological safety is a bedrock for CBME and it cannot be overemphasized with reference to anti-racism related topics. Thus, we launched our anti-racism curriculum with a seminar-style discussion based on the Courageous Conversations® framework [21], which is designed to foster skills to assist in discussion of difficult topics. To anchor the conversation, we utilized James Baldwin’s “A Letter to My Nephew” [22] for its strong themes of history, systemic racism, and humanity. To facilitate and deepen this conversation, we chose a narrative medicine framework for its power to foster narrative humility, multi-perspectives, and radical listening [23]. This session was bolstered by 6 h of faculty development for seminar faculty facilitators, designed in partnership with Columbia University Teachers College faculty. Encouraged by students to obtain expert co-facilitators, we additionally engaged graduate students from our Teachers College, social work, and public health schools who were experienced anti-racism facilitators.

Upstander Curriculum

To further support learning environment belongingness, recognizing that chronic racism creates stress that can impair learning as well as academic and team performance [12, 24], we launched a longitudinal upstander-skills curriculum. As an upstander is someone who intervenes on behalf of others [25], this curriculum offers students the opportunity to practice an advocacy intervention that may feel uncomfortable within a climate of non-judgement and support. Taught at three time points across four years, each session includes preparatory reading and interactive lecture, followed by small-group simulation during which students use sample cases to practice and discuss published strategies to utilize brave spaces for speaking and acting in support of others experiencing bias [26, 27].

Multi-course anchoring and assessment

Finally, we developed longitudinal, multi-course opportunities for anchoring and scaffolding knowledge and strengthening assessment. One significant curricular addition is an Anti-Racism at the Bedside session [28], which links pre-clinical content to concrete clinical tools. This two-hour workshop, designed for second-year students on the cusp of entering their hospital rotations, includes a number of exercises designed to mitigate bias, including practicing history-taking utilizing the structural vulnerability assessment [29]; utilizing the Visualdx.com skin of color diagnostic resource [30]; and practicing note-writing to minimize stigma [31]. To bolster assessment, we integrated multiple choice and short answer questions, and essays within our organ and disease-based pre-clinical courses. Additionally, we partnered with primary care clerkship faculty to develop an essay evaluation rubric for structural competency. Because mapping demonstrated a strong curricular foundation in structural competency, students and faculty felt comfortable with a graded assignment for this topic.

Developing an anti-racism program objective domain

In fall 2022, our medical school began an expansive curriculum re-imagining. This process was parallel to the ARDEI curriculum development and deeply informed by the work described above. As a first step to the curriculum re-imagining, the school revised its overall medical education program objectives (MEPOs). In addition to incorporating the six ACGME core competencies to develop our MEPO domains, we created a novel ARDEI MEPO domain based upon the 10 ARDEI learning objectives. The novel ARDEI education program objective domain consists of three competencies: (1) Recognize personal biases and their impact on those around them and on patient care, and apply strategies to mitigate the effects of these biases; (2) Demonstrate skills necessary to serve as an ally to others and to promote agency in others when there is historical injustice; (3) Articulate structural and historical inequities and apply strategies to mitigate systems of oppression in order to achieve equitable health care and learning environments. Several of the original 10 ARDEI learning objectives were also mapped to additional MEPOs domains that include the core ACGME/American Board of Medical Specialties competencies: inquiry and anti-racism, diversity, equity and inclusion. One example is the learning about racial essentialism (e.g., use of race in medical algorithms) which is addressed in the medical knowledge domain. Similarly, understanding the value of diverse teams is covered under the systems-based practice domain.

Results

Our approach to program evaluation has been continually evolving, and initial reviews and impact through various means of evaluation show promise. In February 2024, all students were invited to participate in an anonymous electronic pilot survey developed for this study assessing (a) longitudinality of ARDEI MEPOs and (b) curricular effectiveness in addressing ARDEI MEPOs. See supplemental materials 1 for the study survey. This pilot evaluation was classified as a quality improvement project under The Columbia University Human Research Protection Office guidelines and thus was exempt from IRB review.

One hundred and four of approximately 560 students responded to the survey (19% response rate.) A diversity of years of training were represented (28% fourth-year, 16% third-year, 15% second-year, 27% first-year, and 13% extended-year students [e.g., additional research year, MD/PhD, etc.]). Whereas demographics were not collected, respondents indicated 52% involvement in student-run free clinics and 61% affinity group membership [32].

Exposure to the MEPOs in the ARDEI domain in multiple learning sessions was prevalent. Additionally, participants rated reflection and knowledge objectives to be more effectively covered than skills application objectives. On a four-point Likert scale, from very effective to very ineffective, 83% selected “very effective” or “somewhat effective” for MEPO “Recognize personal biases and their impact on those around you and on patient care”; whereas 59% reported the curriculum was “very effective” or “somewhat effective” in meeting the MEPO “Apply strategies to mitigate systems of oppression in order to achieve equitable health care and learning environments.” Reassuringly, the MEPO addressing critical psychological safety, brave space, and belonging skills, “Demonstrate skills necessary to serve as an ally to others and to promote agency in others when there is historical injustice,” was strongly rated: 82% selected “very effective” or “somewhat effective.”

In open-ended responses, several students commented on curricular longitudinality, noting content was sometimes repetitive and anti-racist curriculum was most robust during pre-clinical years but tapered off during third and fourth years. Responses also highlighted a need to deepen anti-racism and health disparities content on the nuanced racialization of different groups of people of color. We plan to address this feedback in the upcoming academic year and hold focus groups to expand our understanding of students’ curricular experiences.

Discussion

Preparing medical students for their role in addressing policies and practices in medicine that perpetuate systems of oppression is critical to achieving health equity. Through a close collaboration between students and faculty, we created mechanisms for rapid-cycle curricular innovations. We developed a novel anti-racism MEPO domain with longitudinal learning objectives that contributes to the growing corpus of anti-racism undergraduate medical education – providing a blueprint for creating content that is integrated across a curriculum.

This process was launched within the urgency of societal events in 2020; calls for rapid action led to initial short-term curricular additions. First, we focused on filling important content gaps for faculty and students and bolstering psychological safety to increase belongingness and a growth mindset within our learning community. We then transitioned to a backward design model, mapping opportunities to scaffold reflective, critical thinking and building opportunities for iterative knowledge and skill development.

It is important to note that foundational anti-bias work had previously been spearheaded by students in 2017, who launched anti-bias curriculum (ABC) faculty guidelines and an associated anonymous feedback portal to strengthen student-faculty partnership [33]. Three years later, in 2020, a survey of faculty revealed suboptimal use of the ABC and missed opportunities to decrease bias and combat racial essentialism in teaching materials. As a structural reminder, we launched a “disclosure slide” for faculty to display at the start of their teaching. On the slide, entitled “A Statement of Partnership and Humility,” faculty acknowledge that they have read the ABC and attempted to follow the ABC guidelines. Additionally, on the slide faculty invite direct or anonymous student feedback by posting their email and the link to our school’s anonymous bias feedback portal [34]. The slide is designed to strengthen and model a growth mindset/life-long learning perspective and is now used for all pre-clinical and an increasing proportion of clinical lectures.

Mapping our current curriculum to the newly developed ARDEI learning objectives and ARDEI-focused MEPO domain has enabled us to identify implementation barriers. A primary challenge of developing and implementing our longitudinal ARDEI curriculum, supported by student survey comments, is in situating and implementing anti-racism curricular content during the clerkship phase of the curriculum. This is our primary target currently; initiatives include development of an integrated, longitudinal OSCE-fortified, skill-based curriculum to scaffold student competency across required hospital clerkships.

Additionally, we have identified a need to develop, validate, and utilize robust assessments to demonstrate that learners are meeting the ARDEI learning objectives and MEPOs, i.e., that our longitudinal, supportive curriculum results in enhanced clinical behaviors and skills. We acknowledge that current evaluation data is preliminary, using limited survey data without validity evidence, and is limited to Kirkpatrick outcome levels 1 (satisfaction) and level 2 (knowledge). We are currently expanding on longitudinal assessment data to strengthen evidence of curricular effectiveness, particularly at the higher levels of behavioral change (Kirkpatrick level 3) which are an essential component of our ARDEI competencies.

Additional next steps include continued content, evaluation, and faculty development. Curricular mapping requires iteration and is key to remaining relevant within changing societal contexts. In Fall 2024, we broadened our focus from anti-black racism, adding required content about forced sterilization to highlight medicine’s complicity in promoting oppression, including antisemitism and eugenics impacting Jewish, Asian, and Hispanic populations and people with disabilities [35]. Additional ongoing content expansion plans include carceral care, climate justice, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex health. Notably, our curricular mapping process has become a blueprint for our school’s development of additional societal curricular themes as required by LCME guidelines. We will be conducting a formal evaluation of our ARDEI MEPOs and overall health equity and justice curriculum to continue to identify areas for improvement.

Finally, although our mapping was spearheaded by students, we recognize the need for and have launched a systemic, faculty-driven process in the form of an annual course director continuous quality improvement survey to document ARDEI learning and assessment plans and to solicit suggestions for faculty development. To reinforce faculty development, we are currently surveying our faculty to target follow-up development offerings.

Conclusion

Educating the next generation of healthcare providers to address and reverse unjust health disparities is not a matter of politics; rather excellence in science and medical education depends upon sequential, coordinated learning and practice of ARDEI knowledge and skills across the years of medical school. This article outlines a commitment to an ARDEI MEPO domain is both innovative in its scope and breadth. While many of the activities in the curriculum reflect widely used educational practices, the integration of structural competency and anti-racism throughout the four-year curriculum sets it apart. This approach is woven into the care of our diverse patient population and the community of Upper Manhattan, New York, NY, USA, reflecting a novel strategy to address the needs of both local and global communities that our graduates may serve.

The processes and preliminary outcomes of developing our longitudinal curriculum in equity and justice demonstrate a path forward, toward comprehensive, stepwise ARDEI learning and competency development that can be implemented by other schools. Central to implementation is early, sustained partnership between students and faculty, to foster the psychological safety essential to building engaging, trusted MEPOs for faculty and students. Extant, comprehensive AAMC DEI competencies offer an authoritative, leading-edge roadmap for MEPO development, from which backward design and iterative curricular mapping can foster longitudinal curriculum development. Our pre-matriculation reading curriculum provided a low-budget, high-content knowledge foundation, and our utilization of experts from education, public health, social work, community leaders, and the humanities, suggests a multidisciplinary strategy for content and faculty development that will support institution-specific curricular models. A longitudinal health equity and justice curriculum with well-defined anti-racist objectives that is (a) based within a supportive learning environment, (b) bolstered by trusted, structured avenues for student feedback and (c) amended with iterative revisions is a promising model to ensure that medical students are equipped to effectively address health inequities and deliver the highest quality of care for all patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge former equity and justice fellows: Keyanna Jackson, Spencer Dunleavy, Veronica Kane, Gabrielle Wimer, Emily McNeill, and Grace Pipes for their invaluable contributions to this curricular mapping process. We are grateful to Aubrie Swan-Sein for her help with evaluation guidance. We also wish to thank foundations of clinical medicine faculty leaders, Michael Devlin, Delphine Taylor, Prantik Saha, Daniel Neghassi, Steven Canfield, and Beth Barron for their devotion to advancing this work.

Abbreviations

- AAMC

Association of American Medical Colleges

- ACGME

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

- ARDEI

Anti-racism diversity, equity, and inclusion (ARDEI)

- CBME

Competency-based medical education

- LCME

Liaison Committee on Medical Education

- TACCT

Tool for Assessing Cultural Competence Training

- MEPO

Medical Education Program Objective

Biographies

Hailey Broughton-Jones

Is a master’s in public health graduate.

Jean-Marie Alves-Bradford

Is Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons (VP&S) Associate Dean for Student Affairs, Suppport & Services..

Jonathan Amiel

Is Director of the Office of Professionalism and Inclusion in the Learning Environment at NewYork-Presbyterian.

Omid Cohensedgh

Were all VP&S medical student justice and equity fellows at the time of this manuscript writing.

Jeremiah Douchee

Was former VP&S medical student justice and equity fellow at the time of this manuscript writing.

Jennifer Egbebike

Were all VP&S medical student justice and equity fellows at the time of this manuscript writing.

Harrison Fillmore

Were all VP&S medical student justice and equity fellows at the time of this manuscript writing.

Chloe Harris

Were all VP&S medical student justice and equity fellows at the time of this manuscript writing.

Rosa Lee

Is VP&S Senior Associate Dean for Curricular Affairs.

Monica L. Lypson

Is VP&S Vice Dean for Education.

Hetty Cunningham

Is VP&S Director for Equity and Justice in Curricular Affairs.

Author contributions

H.B.J. participated is study design, and led drafting and completing the manuscript. JM.AB. co-led curriculum and study design and edited the manuscript. J.A. co-led curriculum design, and participated in drafting and editing the manuscript. O.C. participated in study concept and design; and acquisition and interpretations of data. J.D. participated in curricular mapping, study concept and design and prepared supplemental materials. J.E. participated in curricular mapping, study concept and design and prepared supplemental materials. H.F. participated in curricular mapping, study concept and design and manuscript revision. C.H. participated in study concept and design, acquisition, interpretation of data, and manuscript revision. R.L. was lead MEPO creator and participated in manuscript revision. M.L.L. co-led curriculum design and MEPO creation, and drafted portions of the manuscript. H.C. mentored all aspects of the project, including curriculum design and mapping, study design, manuscript writing, editing, and submission. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This pilot evaluation was classified as quality improvement by the Vice Dean for Education at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons (VP&S) and the VP&S Educational Advisory Group pursuant to The Columbia University Human Research Protections Office and Institutional Review Boards guidelines established by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office for Human Research Protections (https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/faq/qualityimprovement-/index.html); thus informed consent was deemed unnecessary.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Insight Into Diversity and Potomac Publishing. The war on DEI. Published online 2024. https://www.insightintodiversity.com/the-war-on-dei/ Accessed 6 June 2024.

- 2.Bleakley A. Embracing the collective through medical education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2020;25(5):1177–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fatahi G, Racic M, Roche-Miranda MI, Patterson DG, Phelan S, Riedy CA, et al. The current state of antiracism curricula in undergraduate and graduate medical education: a qualitative study of US academic health centers. Ann Fam Med. 2023;21(Suppl 2):S14–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DallaPiazza M, Ayyala MS, Soto-Greene ML. Empowering future physicians to advocate for health equity: a blueprint for a longitudinal thread in undergraduate medical education. Med Teach. 2020;42(7):806–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Association of American Medical Colleges, Medical Education Senior Leaders. Creating Action to Eliminate Racism in Medical Education: Medical Education Senior Leaders Rapid Action Team to Combat Racism in Medical Education. Published online January 2021 https://www.aamc.org/media/63076/download?attachment. Accessed 25 May 2024.

- 6.Sotto-Santiago S, Poll-Hunter N, Trice T, Buenconsejo-Lum L, Golden S, Howell J, et al. A framework for developing antiracist medical educators and practitioner-scholars. Acad Med. 2022;97(1):41–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Racic M, Roche-Miranda MI, Fatahi G. Twelve tips for implementing and teaching anti-racism curriculum in medical education. Med Teach. 2023;45(8):816–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. Action plan for antiracism in medical education: Recommendations from the Vagelos College of Physicians & Surgeons Anti-Racism Task Force. Published online Summer 2021. https://www.vagelos.columbia.edu/file/40405/download?token=V-5Gow8W. Accessed 3 May 2024.

- 9.Lie D, Broker J, Crandall S, Elliott D, Henderson P, Kodjo C et al. Revised Curriculum Tool for assessing Cultural Competency Training (TACCT) in Health professions Education. MedEdPORTAL. 2009;5(3185).

- 10.Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and Structure of a Medical School: Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the MD Degree. Published online March 2024. https://lcme.org/publications/ Accessed 26 February 2024.

- 11.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. New ACGME Equity MattersTM Initiative Aims to Increase Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion within Graduate Medical Education and Promote Health Equity. Published July 28, 2021. https://www.acgme.org/initiatives/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/ACGME-Equity-Matters/#:~:text=ACGME%20Equity%20Matters%20drives%20positive,to%20improved%20patient%20care%20outcomes. Accessed 1 May 2024.

- 12.Edmondson A. Wicked-problem solvers. Harv Bus Rev. 2016;94(6):52–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lomis KD, Mejicano GC, Caverzagie KJ, Monrad SU, Pusic M, Hauer KE. The critical role of infrastructure and organizational culture in implementing competency-based education and individualized pathways in undergraduate medical education. Med Teach. 2021;43(sup2):S7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bollinger L. June. Columbia’s commitment to antiracism. Columbia University Office of the President. Published July 21, 2020. https://president.columbia.edu/news/columbias-commitment-antiracism Accessed 5 2024.

- 15.Yang Y, Tian TY, Woodruff TK, Jones BF, Uzzi B. Gender-diverse teams produce more novel and higher-impact scientific ideas. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2022;119(36). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Wiggins G, McTighe J. Understanding by design. 2nd ed. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development; 2005.

- 17.Wasserman JA, Browne BJ. On triggering and being triggered: civil society and building brave spaces in medical education. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33(5):561–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arao B, Clemens K. From safe spaces to brave spaces: a new way to frame dialogue around diversity and social justice. In The art of effective facilitation 2023 Jul 3 (pp. 135–50). Routledge.

- 19.Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity, equity, and inclusion competencies across the learning continuum. AAMC New and Emerging areas in Medicine Series. Washington, DC: AAMC; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones CPJ. Toward the Science and Practice of Anti-racism: launching a National Campaign against Racism. Ethn Dis. 2018;28(Suppl 1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Singleton G. Courageous conversations about race: a field guide for achieving equity in schools and beyond. 3rd ed. Corwin; 2021.

- 22.Baldwin J. A Letter to My Nephew. Progress Mag. Published online December 1, 1962. https://progressive.org/magazine/letter-nephew/. Accessed 5 June 2024.

- 23.Charon R, Hermann N, Devlin MJ. Close reading and creative writing in clinical education: teaching attention, representation, and affiliation. Acad Med. 2016;91(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Kim JY, Botto E. Examining the impact of exclusionary behaviors on team dynamics. Appl Clin Trials. 2023;24.

- 25.Oxford University Press. 2024. https://premium-oxforddictionaries-com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/definition/english/upstander?q=Upstander. Accessed October 10, 2024.

- 26.Acholonu RG, Cook TE, Roswell RO, Greene RE. Interrupting microaggressions in Health Care settings: a guide for Teaching Medical Students. MedEdPortal. 2020;16:10969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandoval RS, Afolabi T, Said J, Dunleavy S, Chatterjee A, Olveczky D. Building a Toolkit for medical and Dental students: addressing microaggressions and discrimination on the wards. MedEdPortal. 2020;16:10893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarleton C, Tong W, McNeill E, Owda A, Barron B, Cunningham H. Preparing medical students for anti-racism at the bedside: teaching skills to mitigate racism and bias in clinical encounters. MedEdPORTAL.2023;19(11333). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Bourgois P, Holmes SM, Sue K, Quesada J. Structural vulnerability: operationalizing the Concept to address Health disparities in Clinical Care. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):299–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldsmith LA, editor. VisualDx. Rochester, NY: 2021. URL: https://www.visualdx.com/. Accessed October 4, 2024.

- 31.Goddu P, O’Conor A, Lanzkron KJ et al. S,. Do Words Matter? Stigmatizing Language and the Transmission of Bias in the Medical Record [published correction appears in J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(1):164]. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):685–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, Clubs, Organizations, Published. 2024. https://www.vagelos.columbia.edu/education/student-resources/office-student-affairs/vp-s-club/clubs-and-organizations. Accessed 10 September 2024.

- 33.Benoit LJ, Sein AS, Quiah SC, Amiel J, Gowda D. Toward a bias-free and inclusive medical curriculum: development and implementation of student-initiated guidelines and monitoring mechanisms at one institution. Acad Med. 2020;95(12S):s145–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benoit LJ, Alves-Bradford JM, Amiel J, Gordon RJ, Lypson ML, Pohl DJ et al. Statement of Partnership and Humility: a structural intervention to Improve Equity and Justice in Medical Education. Acad Med. 2023:10–1097. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Kluchin R. How should a physician respond to discovering her patient has been forcibly sterilized? AMA J Ethics. 2021;23(1):18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.