Abstract

1. Aims: In this review, we highlight the identification and analysis of molecules orchestrating dopamine (DA) signaling in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, focusing on recent characterizations of DA transporters and receptors.

2. Methods: We illustrate the isolation and characterization of molecules important for C. elegans DA synthesis, packaging, reuptake and signaling and examine how mutations in these proteins are being exploited through in vitro and in vivo paradigms to yield novel insights of protein structure, DA signaling pathways and DA-supported behaviors.

3. Results: DA signaling in the worm, as in man, arises by synaptic and nonsynaptic release from a small number of cells that exert modulatory control over a larger network underlying C. elegans behavior.

4. Conclusions: The C. elegans model system offers unique opportunities to elucidate ill-defined pathways that support DA release, inactivation, and signaling in addition to clarifying mechanisms of DA-mediated behavioral plasticity. Further use of the model offers prospects for the identification of novel genes and proteins whose study may yield benefits for DA-supported neural disorders in man.

Key Words: dopamine, receptor, transporter, C. elegans, nematode; behavior

Initially propelled by the elucidation of pathways for catecholamine metabolism and inactivation by Axelrod and coworkers during the “Golden Age of Psychopharmacology,” studies of dopamine (DA) function and dysfunction have now reached a level of maturity suitable for the infusion of new approaches that can add luster to an already impressive legacy (Axelrod, 1971). The following review charts the development of the powerful model Caenorhabditis elegans in terms of DA biology, with a focus on the elucidation of C. elegans DA transporters and receptors. Traditionally a genetic model well-suited to the use of chemical mutagen-based screens for the study of neural development and behavior (Brenner, 1974), the completion of the nematode genome sequencing project provided pathways for mammalian biologists to more readily access the paradigms of C. elegans research (Consortium Ces, 1998). An analysis of over 1800 mammalian genes revealed that 44% of the genes surveyed contained orhologs in C. elegans, with a mean amino acid identity of ∼49%. (Hodgkin, 2001). The identification of nematode orthologs to proteins supporting DA signaling has provided for traditional biochemistry and pharmacology studies, but also given rise to novel forward and reverse genetics using nematode behavior (Suo et al., 2003; Chase et al., 2004; Sanyal et al., 2004; Nass et al., 2005). With recent advent of cell culture methods for C. elegans (Christensen et al., 2002), opportunities to fuse powerful electrophysiological and pharmacological techniques with the facile transgenic methodologies of the nematode become amenable. Among the first to exploit these methods have been DA biologists (Carvelli et al., 2004; Nass et al., 2005). Following a brief review of the anatomy of DA neurons in C. elegans, we trace recent efforts to identify and characterize C. elegans DA receptors and transporters in vitro and in vivo and the new opportunities afforded for catecholamine research by this unique model system.

C. elegans DA NEUROANATOMY

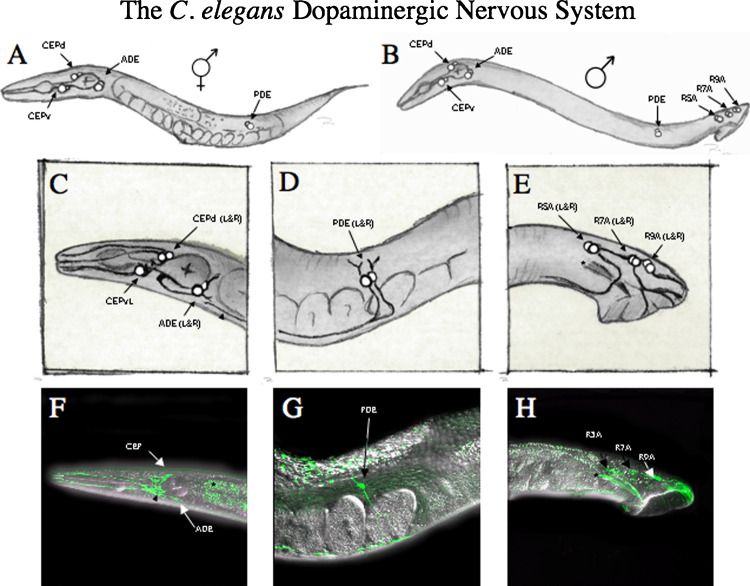

The C. elegans hermaphrodite, the principally propagated form of the organism, is comprised of 959 somatic cells, including 302 neurons. Remarkably, all neuronal connections have been determined by serial EM reconstruction (Ward et al., 1975; White et al., 1986; Hall and Russell, 1991). At these synapses, nematodes rely on many of the same neurotransmitters used in mammals including DA, 5HT, acetylcholine, glutamate and GABA (Rand et al., 1998; Koushika and Nonet, 2000). DA was originally detected in C. elegans by its characteristic formaldehyde-induced fluorescence (FIF), revealing eight DA neurons in the hermaphrodite with an additional set of six DA neurons specific to male worms (Sulston et al., 1975). Sulston originally described the DA neurons in both the hermaphrodite and male, describing “bilateral symmetrical pairs and processes.” The most anterior of these cell pairings is the left and right ventral cephalic neurons (CEPvL and R, Fig. 1A–C). These neurons reside in the isthmus between the anterior pharangeal bulb and the posterior bulb or the “grinder,” just anterior to the largest collection of ganglia in the worm known as the nerve ring (NR). These neurons send long “dendritic-like” projections up to the nose of the animal, and have been identified as important in dictating basal slowing in response to bacterial lawn (Sawin et al., 2000). The ventral CEP group also sends “axonal-like” projections into the NR where they make synaptic connections with multiple partners including reciprocal connections between CEPvL to CEPvR (Fig. 1). The next dopaminergic pairing lies just posterior to the NR on the dorsal aspect of the animal and is part of the cephalic neuron grouping (CEPdL and CEPdR). These neurons are just anterior to the posterior bulb and send long “dendritic” projections up to the nose and short “axonal” projections into the nerve ring. All four of the CEP “dendritic” projections terminate in the nose where they are surrounded by both sheath and socket cells (CEPsh and CEPso), which envelope the sensilum ending (Ward et al., 1975). The CEP neurons as a group synapse on several neurons in the NR including the RIP neurons that are part of the pharangeal nervous system (Riddle, 1997) and neurons that are important for navigation in C. elegans (Gray et al., 2005), including the interneurons RIA and RIB and the head and neck motor neurons RIV, SIA, SIB, and SMB.

Fig. 1.

Anatomy of dopaminergic neurons in C. elegans. (A–E) Cartoon representations of dopaminergic cell bodies and dendritic/axonal projections in both the hermaphrodite and male. (A) DA neuronal cell bodies in the hermaphrodite are illustrated as white spheres in their respective locations throughout the nematode body. The CEP cell bodies both dorsal (CEPd) and ventral (CEPv) reside in the isthmus between the pharangeal and terminal muscle bulbs used for feeding. The ADE neurons lie both posterior and ventral to the terminal bulb as depicted. The final DA neuronal pair in the hermaphrodite are the PDE cell bodies which lie halfway between the vulva and tail in the ventral aspect of the nematode body. (B) Male neuroanatomy of DA neurons includes the CEP, ADE, and PDE cell groups with an additional six cell bodies in the male tail used for mating. These neurons line the dorsal ridge of the tail and are divided into three sets called R5A, 57A, and R9A, respectively. (C) High resolution illustrations of the DA neuron anatomy in the head. CEP (both dorsal and ventral) send small “axonal-like” projections into the nerve ring with long “dendritic-like” projections up to the nose which terminate in sensilar endings. The ADE neurons send “dendritic-like” projections to the lateral walls (both left and right) which terminate in sensilar endings. The ADE “axonal” projections move along the ventral aspect of the body anteriorly where they form a large ventral ganglion. PDE projection termination is noted (arrowhead) along the ventral aspect of the body, just posterior to the ADE cell bodies. (D) High resolution illustration of the DA neuron anatomy of the mid-body. PDE neurons send small “dendritic” projections to the lateral aspect of the muscle walls (both left and right) where they terminate in sensilar endings. The PDE sends a long “axonal” projection which begins ventrally, and then moves both anteriorly, and posteriorly (not shown) along the ventral nerve cord. (E) High resolution illustration of the male DA neuron anatomy in the tail. R5A, R7A, and R9A cell bodies send long projections along the dorsal ridge of the tail and into sensory rays of the tail. Autofluorescence from the mail spicule is seen in H and is noted in the illustration (asterisk). (F–H) Fluorescently labeled DA neurons in an intact living nematode. 3D reconstruction of confocal images used to visualize DA neurons in vivo. Image stacks were taken at 0.5 μm using two-channel imaging for both green fluorescent protein (GFP) and differential interference contrast (DIC) conditions. 3D reconstruction was done using Zeiss LSM 510 software. DA neurons and projections in the head of the nematode using cytosolic GFP expressed using the DAT-1 promoter in vivo. Note long CEP projections into the nose of the animal and extensive elaboration of signal in the nerve ring (NR, arrowhead). A small amount of autofluorescence can be seen in the gut (asterisk). PDE projections in the mid-body of the nematode in vivo. Only one of the two PDEs is visible in this image but both the apical “dendrite” and ventral “axonal” projections can be seen. Note that the predominance of the GFP signal is elaborated along the ventral nerve cord, projecting up to the head. Male DA neuroanatomy in vivo. R5A, R7A, and R9A cell bodies can be visualized along the dorsal ridge of the male tail, sending projections down into the tail sensory rays. Spicule autofluorescence can be seen just below R5A cell body (asterisk). Connectivity of the DA head neurons was documented by White et al. (1986) and is annotated in wormbase (www.wormbase.org). DA neurons make extensive connections which are noted below. Each neuron listed receives input from one of the six DA head neurons. The specific neuron is noted using superscripted numbering system, with a key noted below the list. DA wiring: DA neurons synapse on: ADEL2R1, ADAL1R2, ADLL5, ALA2, ALMR1,2, ASGR6, AVAL1,2R1,2, AVDL1R2, AVEL1,4,6R2,3,5,6, AVJR1,2, AVKL1,2R2, AVL1, BDUL1R4, CEPdL1R2, CEPvR6, FLPL1,2R2, IL1L1,3R4, IL2L1, IL1dL3R4, IL1vL5R6, IL2vR6, OLLL5, OLL1,3R2,4,6, OLQdL3R4, OLQvL5R6, PVR2,6, RIAL1, RIBL3,5R4,6, RICL3,4,5,6R3,4,5,6, RIFL1R2, RIGL1,2R1,2, RIH1,2, RIPL3,5R4,6, RIS3,4, RIVL1,6R1,2, RMDL1R2, RMDdL2,4,5R6, RMDvL3R4, RMGL1,3, RMFL4,6, RMHL1,2,4,5,6R3,4,5, RMGR4,6, SAAvR2, SDQR2, SIAdL4 R1,3, SIAvL5R2,6, SIBdR1, SMBdR1,3,4, URAdL3R4, URAvL5R6, URBL1,3,5R4, URXL3, URYdL3R4, URYvL5. Mu_bod4, 1ADEL, 2ADER,3CEPDL, 4CEPDR, 5CEPVR, 6CEPVL.

The third pair of neurons in the head of the worm is known as the anterior deirid neurons (ADEL and ADER) and are located both ventrally and posterior to the posterior bulb (Fig. 1). ADE “dendrites” terminate in the anterior deirid located bilaterally on both sides of the worm head. These dendritc projections terminate in a sensory organ known as a sensillum, which is embedded in the cuticle and made up of the ADE dendritic projection and a sheath and socket cell. The ADEs send their “axonal” projections along the ventral aspect of the terminal bulb where they come together into what Sulston originally described as a “ventral ganglion” which lies just posterior to the NR. Synaptic connections from the ADEs can be traced to several neurons in the NR including ALM, AVA, and AVD neurons (Chalfie et al., 1985) involved in touch response.

The final pair of DA neurons in the hermaphrodite reside in the dorsal aspect of the worm, halfway between the vulva and the tail. This pair known as the posterior deirid neurons (PDEs) send “dendritic” projections that terminate in the posterior deirid and make up a sensilla similar to the sensillar ending noted for the ADE neurons. Again, the PDE ending is supported by both a sheath and a socket cell and embedded in the cuticle. The PDE “axonal” projections project ventrally from the PDE cell body, and run both anteriorally and posteriorally along the ventral nerve cord. Little is known about the synaptic connections made by the PDE neurons.

The male tail contains three extra sets of DA containing neurons required for mating (Loer and Kenyon, 1993; Liu and Sternberg, 1995). With serial EM reconstruction done only in hermaphrodites, no specific synaptic connections are mapped for these neurons.

C. elegans DA SUPPORTED BEHAVIORS

The effects of DA in the nematode have primarily been elucidated through analysis of animals where DA has either been reduced to inhibit DA signaling, or augmented to enhance DA signaling. Reduction of DA can be achieved via laser ablation of DA specific neurons, whereas DA enhancement can be achieved via the exogenous application of DA. These studies have indicated a role for DA in a wide array of nematode behaviors including egg-laying, defecation, basal motor activity, sensation/response to food sources, and habitutation to touch. Below, we review these behaviors as a context for understanding the physiological impact of DA signaling proteins and as a discussion of paradigms that show promise for further dissection of DA-linked genes.

Egg-Laying

Following the elucidation of egg-laying deficits arising from deficits in response to exogenous and endogenous 5-HT (Trent et al., 1983; Desai and Horvitz, 1989), Schafer and Kenyon described the effects of exogenous DA on both egg laying and movement (Desai et al., 1988; Schafer and Kenyon, 1995). These effects display adaptation where, initially, animals exposed to high concentrations of DA (3 mM) decrease egg-laying frequency and are rapidly paralyzed. Both egg-laying and movement return to normal over the course of several hours despite continued DA exposure. Increasing DA concentrations, once normal activity had returns, has no effect, indicating that both of these behaviors adapt in the presence of DA (Schafer and Kenyon, 1995). Adaptation to DA requires prolonged exposure (at least 3 h) and is reversed in a similar time course. A forward genetic screen for mutants that failed to adapt to DA identified unc-2 as a gene important for modulating this plasticity. The unc-2 protein is a voltage gated Ca++ channel required for proper movement in C. elegans (Brenner, 1974; Schafer and Kenyon, 1995). A novel allele of unc-2 was identified in this screen, suggesting that DA-induced activation of UNC-2 is required for this DA adaptation. Cloning of the unc-2 gene revealed homology to mammalian voltage gated Ca2+ channels. Mosaic expression of unc-2 coupled with in situ hybridization studies indicated that adaptation to DA is only rescued when unc-2 is expressed in the VC and HSN neurons (Schafer and Kenyon, 1995). Recently, expression of the human migraine associated Ca2+ channel CACNA1A was found to be sufficient to rescue 5HT defects seen in unc-2 animals but no DA behaviors were tested (Estevez et al., 2004). Interestingly, Olson et al. have established that D2 DA receptors regulate voltage-gated calcium channels in mammalian striatal medium spiny neurons via a macromolecular signaling network involving the proteins Shank and Homer (Olson et al., 2005). Further manipulation of adaptation supported by C. elegans Ca++ channels may allow for a richer examination of these interactions in vivo as well as provide for the elucidation of additional effectors that lie downstream of DA-regulated calcium signaling and which likely have mammalian homologues.

Soon after Schafer and Kenyon reported their findings on DA and 5HT dependent adaptation, Weinshenker et al. re-examined 5HT effects on egg laying behavior and uncovered a 5HT independent pathway involving DA. In their proposed model for 5HT-induced egg laying, the hermaphrodite specific neuron (HSN) releases 5HT, which acts directly on egg laying muscles to induce their contraction. However, the egg laying defective (egl) mutant egl-2(n693) lays eggs in response to the 5HT transporter inhibitor imipramine but not 5HT itself (Trent et al., 1983). In an attempt to elucidate 5HT's role in egg laying in light of this result, Weinshenker et al. used an egl mutant that lacked the HSN neuron ((egl-1 (n478) and (n986)) and tested various compounds including imipramine and the D2 antagonists chlorpromazine on egg-laying. In their study, both imipramine and chlorpromazine induced egg-laying in the egl-1 background, implying that the effects of these compounds were not dependent on HSN release of 5HT. Further studies revealed that egl-2 encoded an imipramine-sensitive potassium channel (Weinshenker et al., 1999), clarifying why the serotonergic HSN neuron was not required for imipramine reinstatement of egg laying in egl-2 mutants. However, they fail to explain the actions of D2 antagonists, leaving open a role for DA in the egg laying circuit (Weinshenker et al., 1995). We will return to this topic following a review of DA receptors.

Defecation

Application of exogenous DA decreases enteric muscle contractions in wild type worms resulting in slowed defecation (Weinshenker et al., 1995). The egl-2 (n693) mutant that originally was found to exhibit egg-laying defects also inhibits enteric muscle contractions (EMCs). This mutant is a gain of function mutation that displays enhanced potassium current at low voltages and is expressed in C. elegans enteric muscles (Weinshenker et al., 1999). This suggests that DA normally enhances potassium channel activation and would explain why D2 antagonists such as chlopromazine, haloperidol, butaclamol, droperidol, and pimozide reinitiate defecation (Weinshenker et al., 1995). Since UNC-2 expression is also found in GABAergic DVB neurons, which work with AVL to control enteric muscle contractions (McIntire et al., 1993), it is not yet clear whether DA regulation occurs at the level of the AVL or on the enteric musculature itself. Regardless, DA modulation of potassium channels is also a critical facet in mammals of DA-mediated cortical plasticity (Dong et al., 2005) and thus further evaluation of the components supporting DA regulation of EGL-2 in defecation circuits in the worm may shed light on pathways critical to higher brain function in man.

Movement

Exogenous DA causes rapid and reversible paralysis in C. elegans. This behavior displays adaptation or desensitization involving the activity of the voltage gated Ca++ channel UNC-2 (Schafer and Kenyon, 1995). Unc-2 mutants displayed a leftward shift in paralysis induced by DA indicating a greater sensitivity to DA induced paralysis compared to wild type worms. Although this shift in DA potency was slight, the ability of unc-2 mutants to adapt to DA was severely compromised to the point where the majority of unc-2 animals display no spontaneous movement with prolonged DA exposure, whereas wild type animals regain movement after 3–4 h in DA. Expression of unc-2 was noted in both the VC and HSN neurons (Schafer and Kenyon, 1995). This expression profile was extended to most motor neurons in the ventral nerve cord and the nerve ring motor neuron SDQR (Mathews et al., 2003). Expression was also seen in the head and tail region including in olfactory sensory cells AWC and the GABAergic tail neuron DVB.

As often happens, progress in one area (DA signaling) leads to insights in another (channel biology). Cloning of various unc-2 alleles revealed that mutations sufficient to alter adaptation to DA reside in various locations in the UNC-2 protein, likely resulting in a loss of function of this channel (Schafer and Kenyon, 1995). Indeed, insertion of identified unc-2 mutations into the rat voltage gated Ca++ channel alpha 1A subunit (the most homologous to UNC-2) and electrophysiological experiments revealed that mutations caused a variety of current defects from total loss of Ca++ induced current (e55 mutation), to rapid inactivation (ra612) or reduction of pre-pulse potential (Mathews et al., 2003). These studies underscore the opportunities available in combining forward genetic studies of model organisms with studies of mammalian channel orthologs (Weinshenker et al., 1999; Wei et al., 2005). Importantly, mammalian calcium channels are targets of DA modulation (Neve et al., 2004), and thus lessons learned in the effort to explore DA modulation of motor activity are likely to be relevant for the wide variety of actions of DA in the mammalian CNS.

Basal Slowing Response

Besides its use for studies of the control of basal motor activity, the nematode model exhibits fine-tuning of motor plasticity that engages signaling pathways responsive to DA. C. elegans slow in the response to a bacterial lawn (Sawin et al., 2000). This response is mediated by either DA or 5HT depending on the dietary history of the animal. DA dictates basal slowing response in well-fed animals. Under these conditions, the TH mutant cat-2(e1112) shows no basal slowing response, indicating that this behavior is DA mediated (Sawin et al., 2000; Chase et al., 2004). Exogenous DA restores basal slowing response in cat-2(e1112) mutants as well as in the cat-4(e1141);bas-1(ad446) double mutant (an animal which lacks catecholamines altogether), indicating that a lack of endogenous DA is responsible for this behavior. Laser ablation of DA neurons has led to the identification of neurons that likely account for DA-mediated motor slowing in response to food (Sawin et al., 2000), specifically implicating actions of CEP neurons. Interestingly, double ablation of both the CEP and ADE neuronal cell groups restored the basal slowing response, suggesting more complex control of this behavior than initially recognized. Basal slowing was found to be a mechanosensory phenomenon as Sephadex G-200 beads could substitute for bacteria to elicit this response. Moreover, elimination of DA, using either the cat-2(e1112) mutant or by cellular ablation of all DA neurons in hermaphrodites, removed basal slowing in response to Sephadex beads (Sawin et al., 2000). Importantly, these studies reveal a role of DA in short-term motor plasticity, reminiscent of actions the amine plays in fine tuning the output of the motor program in vertebrates. Although the circuits that subserve motor output in man are far more complex, lessons gathered regarding the neuromodulatory actions of DA in the C. elegans motor program can shed light on neuromodulatory integration just as studies of the modulation of the Aplysia gill reflex by 5HT have provided lessons relevant for learning and memory in man (Kandel and Schwartz, 1982).

Area Restricted Search

An additional form of motor plasticity with DA support in the nematode is area restricted search (ARS) for food (Hills et al., 2004). Search behavior is displayed by organisms when food is encountered and is typified by an increase in turning behavior (Bell, 1991). This behavior is thought to arise from an organism's need to conserve energy in the search for food, with search area increasing over time once the local food source has been exhausted. This change from a focal to a more global search area results from a decrease in turns after food depletion. If initially exposed to a bacterial lawn, nematodes that are subsequently moved to a plate with no bacteria display a high number of acute-angled turns (<50°) in search of food. After 30 min without food, the number of these high angled turns is reduced, indicating that the worms are extending their search area (Hills et al., 2004), an activity that can be quantified using an ARS index (ARSI) determined by the number of turns observed in the first period divided by the number of turns observed in the last or test period. In contrast to the motor slowing response previously described, Hills et al. observed that changes in the ARSI were only seen in response to food and not in response to other sensory stimuli (Hills et al., 2004). Genetic ablation of all DA neurons resulted in an inability to change ARS after 30 min on plates lacking food, indicating that either synaptic DA action or humoral DA provided from one or more of these sources is required for ARS. Ablation of either the CEP or ADE neurons alone had no effect on adaptation, whereas PDE ablation resulted in a reduction in habituation, suggesting that PDE signaling is required for learning to expand ARS and decrease turning behavior. Interestingly, ablation of both the ADE and PDE neurons results in a hyperturning phenotype that still habituats after 30 min off food, suggesting that multiple DA neurons coordinate to modulate ARS. Here, an intact CEP neuron may mediate hyperactive turning, an activity that is potentially opposed by ADE output. Because habituation is still seen in this experiment, DA release in the nerve ring by CEP may be sufficient for ARS. However, ADE inputs into the nerve ring are not sufficient to mediate ARS in the PDE/CEP double ablation implying that CEP-specific innervations are required. When both CEP and PDE neurons are ablated, habituation off of food is completely lost, implying that these two neurons work synergistically to mediate this behavior. One complication in this analysis is that there appears to be two distinct behaviors assayed in this experiment. The first is head turning frequency, the second is ARS. Head turning frequency is increased by CEP neurons and appears to be inhibited by both ADE and PDE neurons. PDE neurons seem to be required for ARS because in the ADE/CEP double mutant ARS still occurs while in the genetic triple mutant habituation is lost while hyperturning is retained.

Interestingly, exogenous DA increases the number of high angle turns, implying that DA is sufficient to activate ARS. Endogenous DA was also shown to be required for ARS because cat-2 (tyrosine hydroxylase, see below) mutants that contain little endogenous DA do not show increased frequency of head turning. Another interesting result of this research is the fact that movement through Escherichia coli itself is required to reinstate ARS (Hills et al., 2004), although it is not clear whether this activity engages food-source responsive circuits releasing endogenous DA or reflects an independent effect. Interestingly, animals that are allowed to feed display reduced ARSI scores, indicating habituation. Habituation is a common feature of the mammalian DA reward pathway and is thought to drive reinstatement of drug use (Gerdeman et al., 2003). As such, future investigations of DA support for habituation of the ARS pathway may provide useful clues to plasticities underlying drug abuse.

Another form of habituation that appears to involve DA is habitutation to nose tap during which, after a series of nose taps, worms will learn that the mechanical stimulation is non-threatening and will stop reversing (Rankin, 1991; Rankin and Broster, 1992; Rose and Rankin, 2001). Touch response requires five sensory neurons (ALMs, PLMs, and AVM) along with eight interneurons (AVAs, AVBs, AVDs, and PVCs) (Chalfie et al., 1985). The tap withdrawal response requires three additional neurons (PVDs and the DVA interneuron) (Wicks and Rankin, 1995). Mutants that cannot produce DA via tyrosine hydroxylase (cat-2, see below) are defective in normal habituation to non-generalized tap response but this response can be rescued with exogenous DA (Sanyal et al., 2004). Thus DA may play a more general role in habituation of motor responses, whether elicited by food, mates, or threatening stimuli. Although Sanyal et al. note that the CEP and PDE neurons do not synapse directly on neurons mediating the touch habituation response (Sanyal et al., 2004), this still leaves inputs from the ADE neurons which make direct synaptic connections on ALM, AVA, and AVD (Fig. 1) neurons (White et al., 1986) which are utilized in both touch (Chalfie et al., 1985) and tap habituation (Rose and Rankin, 2001). Work by Chase et al. underscores the likely long range, non-synaptic actions of DA in the nematode (Chase et al., 2004), similar to the proposed role of DA in “volume transmission” in the mammalian CNS (Rice, 2000). Thus, although evidence of humoral signaling exists in the C. elegans literature (Chase et al., 2004), ADE inputs to these circuits need to be explored further.

C. elegans DA BIOSYNTHESIS AND STORAGE

Soon after the identification of nematode DA neurons, worm biologists implemented forward genetics to search for genes required for the production and storage of DA. Screening for mutations that produce a loss of FIF led to the identification of six independent catecholamine mutants (cat-1 through cat-6) (Sulston et al., 1975). Cloning of several of these genes identified key proteins known to participate in either DA synthesis or storage. DA synthesis in mammalian neurons begins with the conversion of the amino acid tyrosine to 1-dihydroxypheny-l-alanine (l-DOPA), the immediate DA precursor, by the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), a process that requires the co-enzyme tetrahydrobiopterin (THB). THB is regulated by GTPcyclohydrolase (GTPCH) activity and loss of GTPCH results in down regulation of THB, resulting in decreased DA synthesis (Kapatos et al., 1999). Finally, an efficient, and more widely expressed aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) converts l-DOPA to DA. Cytosolic DA is then rapidly packaged into synaptic vesicles by a vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT) where DA is stored until secreted following neuronal depolarization. Intraneuronal metabolism occurs chiefly through the actions of mitochondrial monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzymes, although, as will be noted below, DA reuptake is thought to play a more critical role in synaptic DA inactivation.

The first DA-related mutant identified (cat-1) displays a loss of punctate DA accumulation normally characteristic of DA nerve terminals (Sulston et al., 1975) and is considered likely to participate in the behavior or physiology of DA storage vesicles. This suspicion was validated in 1999 when Duerr and colleagues cloned the full length cat-1 gene and identified it as a VMAT homolog (Duerr et al., 1999). CAT-1 protein was found to localize to DA and 5HT neurons (Table I) and to be 47% identical to human VMAT1 and 49% identical to human VMAT2. Importantly, CAT-1 supports time-dependent and saturable uptake of both [3H]DA and [3H]5HT in permeablized CV-1 cells, consistent with its role as a VMAT (Duerr et al., 1999). Original studies performed by Sulston et al. used the mammalian VMAT substrate reserpine to deplete these vesicles of catecholamines and eliminate FIF indicating that mammalian VMATs and CAT-1 share similar pharmacology (Sulston et al., 1975).

Table I.

Dopamine Synthesis and Transport Proteins

| BAS-1 | ||

| Mammalian homolog | Aromatic aminoacid decarboxylase | Loer and Kenyon (1993) |

| Substrate | L-Dopa, 5-THP | Loer and Kenyon (1993) |

| Antagonist | ? | |

| Cellular expression | Dopamine and serotonin neurons | Hare and Loer (2004) |

| Mutant phenotype | Defective basal slowing response | Sawin et al. (2000) |

| Defective male tail turning (mating) | Loer and Kenyon (1993) | |

| CAT-1 | ||

| Mammalian homolog | Vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT) | Duerr et al. (1999) |

| Substrate | DA, Tyr > 5HT > NE > Oct >> Histamine | Duerr et al. (1999) |

| Antagonist | Reserpine | Sulston et al. (1975) |

| Cellular expression | Dopamine neurons (ADE, CEP, PDE) | Duerr et al. (1999) |

| Serotonin neurons (NSM, HSN, VC4, VC5, ADF, RIH, AIM) | Duerr et al. (1999) | |

| Unidentifed amine (RIC, CAN) | Duerr et al. (1999) | |

| Male neurons | Duerr et al. (1999) | |

| Mutant phenotype | Defective basal slowing response | Duerr et al. (1999) |

| Reduced egg laying | Duerr et al. (1999) | |

| Decreased mating efficiency | Duerr et al. (1999) | |

| Decreased pharangeal pumping | Duerr et al. (1999) | |

| Defective male tail turning (mating) | Loer and Kenyon (1993) | |

| CAT-2 | ||

| Mammalian homolog | Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) | Lints and Emmons (1999) |

| Substrate | Tyrosine | |

| Antagonist | ? | |

| Cellular expression | DA neurons (CEPs, ADEs, PDEs) | Lints and Emmons (1999) |

| Male tail DA neurons (R5A, R7A, R9A) | ||

| Mutant phenotype | Dopamine deficient | Sulston et al. (1975) |

| Defective basal slowing response | Sawin at al. 2000 | |

| ↑ Tap habituation | Sanyal et al. (2004) | |

| Defective area restricted search | Hills et al. (2004) | |

| Defective slowing in Sephadex beads | Sawin et al. (2000) | |

| DAT-1 | ||

| Mammalian homolog | Dopamine transporter | Jayanthi et al. (1998) |

| Substrate | DA > NE, Epi > 5HT | |

| Antagonist | Imipramine, desipramine, nisoxetine, mazindol, GBR 12909, nomifensine, cocaine | Jayanthi et al. (1998) |

| Amphetamine a | Nass et al. (2002) | |

| Imipramine | Jayanthi et al. (1998) | |

| Cellular expression | DA neurons (CEP, ADE, PDE) | Nass et al. (2002) |

| R5A, R7A, R9A in male tail | ||

| Mutant phenotype | ? | |

aData implied from in vivo function studies.

In situ, indirect immunofluorescence studies using antibodies directed against CAT-1 sequence revealed punctate nerve ring fluorescence reminiscent of combined DA and 5HT FIF. in vivo, genomic cat-1 sequences (RM#424L) rescue the DA and 5HT-like FIF deficits of cat-1 mutants (Duerr et al., 1999). The availability of antibodies specific for CAT-1 allowed for important insights into how VMAT proteins are localized to synapses. Although VMATs are located on synaptic vesicles, the trafficking determinants of VMAT had not been defined. Unc-104 is a kinesin motor protein that is known to traffic synaptic vesicles from the cell body to nerve terminals (Hall and Hedgecock, 1991). Loss of function of this protein leads to synaptic vesicle retention in the cell body and a decrease in synaptic signaling, supporting an uncoordinated (unc) phenotype. When CAT-1 protein was visualized in unc-104 (e1264) mutant animals using immunofluorescnece approaches, CAT-1 vesicles were found to accumulate in the cell body, consistent with VMAT employing machinery that traffics synaptic vesicle proteins to the synapse.

Cat-2 has been identified as a tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) homolog, with CAT-2 protein displaying 50% amino acid identity with both Drosophila and rat tyrosine hydroxylase (Lints and Emmons, 1999). GFP promoter fusions using cat-2 promoter sequences demonstrate that CAT-2 is expressed in all dopaminergic neurons of the nematode (Lints and Emmons, 1999). In addition, cat-2 mutants display markedly reduced DA levels (9% compared to WT) as assessed by HPLC (Sanyal et al., 2004) (Table I).

Cat-4 has features of a GTP cyclohydrolase enzyme suitable for production of the TH cofactor THB. While cat-4 has yet to be cloned and its mechanism of action has yet to be defined, predicted amino acid alignments reveal an 83.9% homology with the human splice isoform GCH-1 of GTP-cyclohydrolase (Wormbase, www.wormbase.org).

An aromatic AADC homolog (bas-1) has been identified and is required for 5-HT supported male mating behaviors but as yet has not been implicated in DA-mediated behaviors (Loer and Kenyon, 1993) (Table I). Recently, Hare and Loer mapped the bas-1 (C05D2.4) gene and revealed that bas-1 indeed codes for an aromatic AADC homologue that is sufficient to rescue bas-1 mutant lines for 5-HT immunoreactivity (Hare and Loer, 2004). Although the gene encoded by C05D2.4 (bas-1) rescues serotonin immunoreactivity, other potential homologs which could retain some AADC activity exist in C. elegans and a small amount of 5-HT persists in bas-1 mutant lines (Weinshenker et al., 1995). Two isoforms of bas-1 were identified, bas-1a, which displayed a 41% identity to human dopa-decarboxylase (HsDDC), and bas-1b which included a 27 bp micro-exon inserted between predicted exons 2 and 3. Although more limited information is available concerning a role for bas-1 in DA synthesis, expression of GFP reporter constructs using the bas-1 promoter region reveals DA neuron expression as would be predicted for an aromatic AADC homolog.

Despite the presence of DA catabolites (DOPAC, 3-methoxytyramine, and homovalic acid) in whole worm extracts (Wintle and Van Tol, 2001), proteins important in the catabolism of DA have not been positively identified, although several monoamine oxidase (MAO) and catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) homologues exist in the genome (Wintle and Van Tol, 2001).

THE C. elegans DA TRANSPORTER

In mammalian systems, DA signaling is primarily terminated by presynaptic reuptake mediated by the DA transporter (DAT), with a contribution of DAT to presynaptic DA levels also evident (Gainetdinov et al., 2002). Studies using DAT KO mice (Giros et al., 1996) demonstrate that, after evoked DA release, extracellular DA levels remain elevated in the absence of DAT protein. The C. elegans DAT (dat-1;T23G5.5, originally termed CeDAT-1) was identified by searching C. elegans genomic sequences for genes homologous to mammalian SLC6 family members, including cocaine-sensitive DA, NE and 5HT transporters (Jayanthi et al., 1998), specifically targeting sequences bearing a highly conserved TM1 aspartate residue thought to interact with biogenic amine substrates. The identified DAT-1 protein bears 43% amino acid identity with mammalian DA transporters with the bulk of conservation localized to the transmembrane domains (TM).

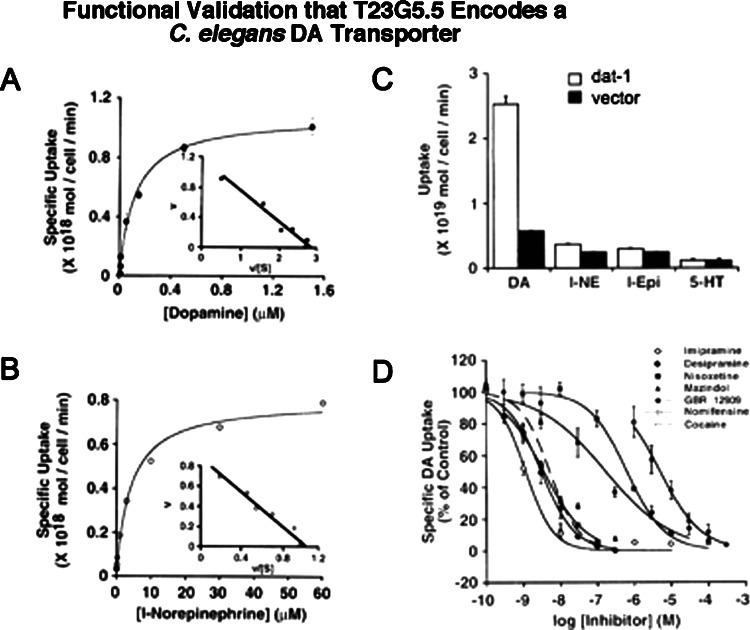

Full length cDNA encoding the product of the dat-1 gene, when transfected into HeLa cells, supports transport of several different monoamines including DA, NE, Epi and 5HT but at distinctly different rates (Fig. 2C). DAT-1 preferentially transports DA over other biogenic amines, with norepinephrine displaying reduced but detectable uptake (DA>>NE>Epi>5HT). Given the absence of NE biosynthetic pathways in C. elegans, DAT-1 activity in the nematode is primarily responsible for the inactivation of released DA. Transport kinetics for both DA and NE was tested where DAT-1 displayed saturable uptake kinetics with a K m of 1.2 μm for DA and 4.1 μm for NE. When transporter specific antagonists were tested for inhibition of [3H]DA uptake (Fig. 2D), the most potent DAT-1 inhibitors were the tricyclic antidepressants imipramine and desipramine, compounds that in studies of mammalian transporters, target 5HT and NE transporters (SERT and NET, respectively). The mammalian NET inhibitor nisoxetine and the mixed DAT/NET antagonist mazindol also displays significant inhibition of DA uptake (Table I). These studies established DAT-1 as a bona fide DA transporter but illustrate that pharmacological sensitivities are often distinct in comparing vertebrate and invertebrate orthologs.

Fig. 2.

Functional validation that T23G5.5 Encodes a C. elegans DA Transporter. (A–B). Saturation kinetics of3H-DA (A) and3H-NE (B) uptake by DAT-1 in transiently transfected cells. Specific uptake was defined by subtraction of uptake activity obtained in vector-transfected cells assayed in parallel. Note the difference in axes values; ordinate legends reflect multiplication of data values by 1018 in order to obtain integer values on the y-axis. Insets, Eadie-Hofstee plots of saturation data (axis units, cell/min/liter×1024) (figure adapted from Jayanthi et al., 1998). (A) Specific uptake of3H-DA by DAT-1. K M: 1.2 μM; V max: 1.08 pmol/106 cells/min. (B) Specific uptake of3H-NE by DAT-1. K M: 4.1 μM; Vmax: 0.79 pmol/106 cells/min. (C) Substrate selectivity of DAT-1 uptake activity in DAT-1- or vector-transfected cells. All [3H]-labeled substrates were assayed at a saturating concentration of 20 nM. Values represent mean±standard deviation of three separate transfections. Ordinate legends reflect multiplication of data values by 1019 in order to obtain integer values on the y-axis. (D) Inhibition of dat-1 mediated3H-DA uptake by monoamine transporter antagonists. Points±standard deviation acquired from three separate competition experiments; nonlinear curve fits obtained using Kaleidagraph software (Synergy Software, Reading, PA).

To gain insight into the expression pattern of DAT-1 in vivo, Nass and coworkers (Nass et al., 2002) drove synthesis of cytosolic green fluorescent protein (GFP) using a 700 bp DNA segment located immediately upstream of the dat-1 transcription initiation site, resulting in fluorescence in all known DA neurons in the worm (Nass et al., 2002). in vivo function of DAT was established through accumulation of the DA neurotoxin 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) (Nass et al., 2002). 6-OHDA treatments of animals wildtype for the dat-1 allele expressing GFP in their DA neurons revealed loss of all DA head neurons with resistance observed in the midline PDE neurons. DA neuron degeneration can be blocked by incubation of worms in DAT-1 transport antagonists such as imipramine. Importantly, neuronal susceptibility to 6-OHDA can be both blocked in DAT-1 deficient lines, and transferred by expression of DAT-1 in cells that typically do not express the transporter (Nass et al., 2002). Features of this DA neuron degeneration, with its similarity to apoptotic versus necrotic cell death, offer insights into the pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease (Nass and Blakely, 2003). In this regard, readily detectible DA neuron degeneration has also afforded adoption of the nematode model for studies of human alpha-synuclein mutants (Lakso et al., 2003) as well as the neuroprotective actions of torsin proteins (Cao et al., 2005).

The dependence of 6-OHDA-induced degeneration of DA neurons on functional DAT-1 has permitted a forward genetic screen for suppressors that have the capacity to elucidate key features of DAT, its regulatory machinery, or facets of toxin-induced cell death. Indeed, Nass and coworkers (Nass et al., 2005) used this assay to identify three novel ethyl methane sulfonate- (EMS)-generated mutant alleles of dat-1 (Fig. 3A). Two of the alleles identified resulted from point mutations in residues conserved across all known members of the SLC6 transporter gene family, suggesting a critical role for these residues in transporter structure and/or function. The third allele identified arises from a splicing defect altering the DAT-1 C-terminus by substituting an ectopic 15 amino acid sequence for the entire C-terminus. Each of these mutations resulted in a complete resistance to the effects of 6-OHDA in vivo. A fourth mutant was identified that also conferred complete resistance to 6-OHDA but which does not map to the dat-1 locus and remains unidentified. Translational GFP-fusions to the DAT-1 mutants were produced for in vitro and in vivo expression to examine how these changes in DAT-1 protein lead to loss of function. The DAT-1 splicing mutant dat-1(vt4) was found to be extremely defective for protein expression in transfected cells and demonstrated only weak expression in vivo , whereas the two point mutants displayed interesting trafficking and surface expression patterns, discussed below.

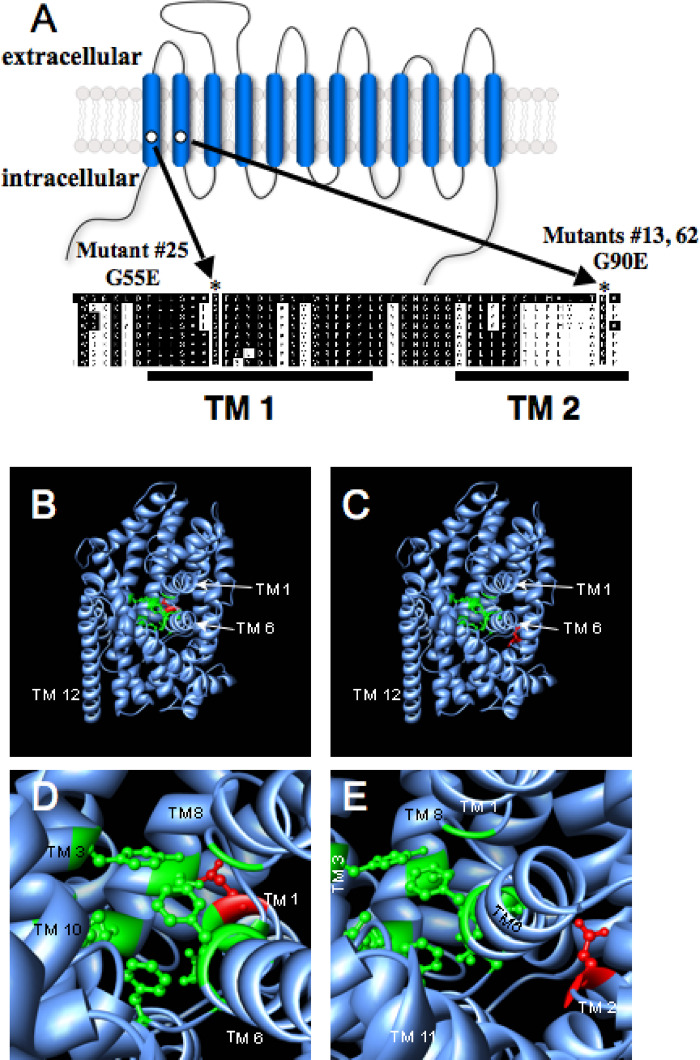

Fig. 3.

Structure modeling of DAT-1 mutations. (A) Schematic of DAT-1 membrane topology. The two mutations, G55E and G90E, occur at positions entirely conserved across eight species variants of dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine transporters as well as most other SLC6 family members including LeuTAa. (B–E) Side view of LeuTAa crystal structure (PDB accession number 2A65.Q9 (Yamashita et al., 2005). Proposed ligand-binding residues (Yamashita et al., 2005) highlighted in green; DAT-1 mutations highlighted in red with glutamate side chain substituted for that of glycine. Amino acid substitutions introduced and images generated using UCSF Chimera software(Pettersen et al., 2004) (http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera). (B) LeuTAa protein with the binding pocket (green) and the G55E mutation (red) highlighted. (C) LeuTAa protein with the binding pocket and the G90E mutation highlighted. (D) Higher magnification of the proposed LeuTAa binding pocket with the G55E mutation highlighted in red. (E) Higher magnification of the proposed LeuTAa binding pocket with the G90E mutation highlighted in red.

The dat-1(vt2) allele, located in TM1, changes a conserved glycine residue to a glutamate (G55E) (Fig. 3). Biochemical experiments using an N-terminal, HA tagged version of this mutant in COS-7 cells revealed reduced expression of full-length transporter that fails to reach wildtype levels on the plasma membrane and which induces no detectable [3H]DA uptake. After expression of an N-terminal GFP tagged version of the G55E DAT-1 mutant in vivo, an overall reduction of GFP signal was observed, with no detectable difference in overall localization (Nass et al., 2005). Loss of DA uptake activity in the face of relatively normal patterns of trafficking suggests that the G55 residue is likely to play an important role in the structural organization of DAT-1 protein and transporter surface insertion/stability but may also indicate actions of this residue in the DA transport process. The other dat-1 point mutation recovered in this screen, dat-1(vt3), induces a conversion of a conserved glycine at position 90 in TM2 to a glutamate (G90E, Fig. 3). Expression of an HA tagged version of this mutant in COS-7 cells revealed transporter accumulation in an immature form, and low but detectable mature glycosylated transporter at the cell surface. Interesingly, uptake of DA by this mutant was either just above or equivalent to that achieved with non-transfected cells, suggesting a significant impact on the DA transport process. in vivo expression of a GFP-tagged G90E mutant results in intracellular accumulation of GFP signal with no elaboration of signal into the nerve ring (Nass et al., 2005).

The recent publication of a high-resolution structure of a DAT-1 homolog, a leucine transporter (LeuTAa) from Aquifex aeolicus (Yamashita et al., 2005), adds new dimensions to interpreting the physical impact of DAT-1 mutations. Mapping of the DAT-1 Gly55 and Gly90 residues onto the LeuTAa structure (in which these glycines are conserved) demonstrates that G55E mutation lies in close proximity to the proposed substrate binding site, potentially engaging residues in TMs 1, 3, 6, and 8 (Yamashita et al., 2005). The substitution of a large, acidic side chain in this area likely results in a deformation of the ligand binding pocket, potentially changing the rotation or helix packing of TM1 that may serve a dual role in transporter assembly and function. In addition to the introduction of bulk at this site, the introduction of a charged side chain, and a new hydrogen bonding partner, in the bottom of the ligand binding pocket may disrupt the favorable binding orientation of DA or its co-transported ions, thereby reducing transport efficiency.

The TM2 mutation, G90E, introduces change in a region of the protein distal to the substrate binding site. However, the addition of increased bulk as well as the introduction of a charged side chain in a protein region likely isolated from the aqueous permeation pathway may significantly impact the helix packing of TM2 with its TM1 and 6 neighbors that support substrate interactions. Review of the LeuTAa structure suggest that the G90E mutation may impact the structure specifically of TM6, a helix proposed to participate in ligand binding as well as the gating mechanism of transport (Yamashita et al., 2005). Given that the G90E mutant reported by Nass et al. 2005 exhibits a reduction in transport V max but no change in DA K m, it seems likely that alterations in helix packing of TMs 1, 2, and 6 induces significant adverse changes linked to the translocation of DA rather than compromising DA recognition. Like the G55E mutant, the decreased efficiency of helix packing of TMs 1, 2 and 6 may also induce global protein misfolding, resulting in trapping of immature DAT in the ER (Nass et al., 2005).

Mammalian DAT proteins exhibit multiple conductance states (Mortensen and Amara, 2003). Use of genetic/transgenic studies of DAT-1 in the nematode have been undertaken and have elucidated novel mechanisms that are relevant in terms of mammalian ion channel biology. Recently, Carvelli et al.took advantage of nematode primary cell culture techniques and obtained recordings from DA neurons isolated from various transgenic lines to monitor DAT-1 channel activity triggered by DA (Carvelli et al., 2004). Lines expressing wild type DAT-1 displayed DA-triggered inward currents like that reported for mammalian transporters featuring chloride ion dependence in the context of a lack of inward leak currents (Kilty et al., 1991; Ingram et al., 2002). Interestingly, lines over expressing an N-terminal GFP:DAT-1 fusion in a wild type DAT-1 background increased the probability of detection of single channel events without changing channel amplitude compared to wild type lines alone, suggesting that N-terminal GFP tagging does not disrupt channel conductance per se but may affect channel gating. The current generated by individual DAT-1 channels was also sufficient to generate a macroscopic depolarizing current in whole cell recordings, indicating that the transporter may participate in DA neuron excitability in vivo. These studies lay the groundwork for genetic dissection of DAT-1 mediated currents and the role of DA neuron physiology in the nematode.

C. elegans DA RECEPTORS

In mammalian systems, DA acts on five distinct G-protein coupled receptors (D1-5) that fall into two separate categories, being either D1-like or D2-like based on signaling specificities. These two classifications were originally assigned based on the receptor's effect on cyclic AMP levels (Spano et al., 1978). These two distinct classes are still recognized, the D1-like receptors positively coupling to adenylate cyclase (AC) increasing cAMP levels, and D2-like receptors inhibiting AC and cAMP formation, although additional second messengers and effector pathways are also recognized (Neve et al., 2004). Four DA receptors have been identified in C. elegans, specified as dop-1, dop-2, dop-3, and dop-4. Each receptor was originally identified by homology searches and has been subjected to both in vitro and in vivo analyses as noted below.

Dop-1 DA Receptors (F15A8.5)

Suo et al. initially identified a D1-like DA receptor using comparison of mammalian DA receptor amino acid sequences to a translation of published C. elegans genome. The gene that displayed the highest homology, F15A8.5, was found to preferentially bind DA over other biogenic amines when expressed in COS-7 cells (Suo et al., 2002). RT-PCR studies revealed that the dop-1 gene encodes three distinct splice variants CeDOP1-L, CeDOP-1M, and CeDOP-1S. Differences in these three variants arise from alternative splicing of a 58 amino acid sequence within the receptor's third intracellular loop, which in mammalian G-protein coupled receptors has been shown to be important for G-protein coupling (Luttrell et al., 1993). The longest of these isoforms, CeDOP-1L, retains this 58 amino acid insertion that also contains consensus phosphorylation sites for both PKC and PKA. CeDOP-1M lacks this sequence, but maintains PKC and casein kinase consensus sequence in the third intracellular loop. The CeDOP-1S isoform is almost identical to CeDOP-1M except for a deletion of three amino acids in the intracellular C-terminus which codes for another PKC consensus phosphorylation site (SSR). Four splice variants have been predicted by gene models including the three isoforms identified by Suo et al. and have subsequently been named dop-1a–d, according to worm nomenclature procedures (Horvitz et al., 1979; Hodgkin, 1995). The splice variant dop-1d has yet to be identified experimentally. Dop-1b was characterized pharmacologically in the initial report and displayed preferential displacement of [125I]Iodo-LSD by DA (DA > NE > 5HT > Tyr = OA). Because there is no evidence of (nor)epinephrine in C. elegans (Horvitz et al., 1982; Sanyal et al., 2004), DA, 5HT, Tyr and OA profiles are the most physiologically relevant in considering potential endogenous agonists of these receptors in vivo.

In 2004, Sanyal et al. reported the cloning of a D1-like receptor using both in silico methods and mammalian D2 receptor sequences, followed by validation of expression and function using RT-PCR and GTPγS binding, respectively (Sanyal et al., 2004). These investigators again identified sequence encoded by the F15A8.5 gene as positive for DA mediated GTPγS binding in COS-7 cells. Only two isoforms of dop-1 were identified in this study (short and long splice variants), corresponding to the CeDop-1L and CeDop-1M transcripts described by Suo et al. Both isoforms stimulated an increase in cAMP production upon DA stimulation, verifying their role as bona fide D1-like receptors. Interestingly, co-expression of dop-1 with the C. elegans GTPγS isoform (gsa-1) in conjunction with the G-protein coupled inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channel (Kir3.2) resulted in a robust activation of a large potassium current (Sanyal et al., 2004). GIRK activation in mammalian systems typically results from activation of Goα via D2 receptors (Missale et al., 1998), indicating that C. elegans DA receptors might signal differently than mammalian DA receptors.

Mammalian D1 receptor agonist and antagonists were assayed for functional coupling in culture on the DOP-1a isoform with mixed results (Table II). The mammalian D1 receptor specific antagonist SCH23390 worked only as an agonist on DOP-1 at high (1 μM) concentrations. The D2 antagonists (+)−butaclamol and haloperidol, the mixed D1/D2 antagonist cis-flupenthixol, and octopamine displayed inverse agonist activity by decreasing the amount of basal cAMP activation (Sanyal et al., 2004). 5HT did not significantly activate DOP-1a (in terms of GTPγS binding). Once again, although signaling pathways appear to overlap comparing mammalian and worm receptors, their pharmacologies are distinct and remain useful for receptor classification.

Table II.

Caenorhabditis elegans Dopamine System Protein Characterization

| D1-like receptors | ||

|---|---|---|

| DOP-1 | ||

| Gene products | Dop-1a (L) | Suo et al. (2002) |

| Dop-1b (M) | Suo et al. (2002) | |

| Dop-1c (S) | Suo et al. (2002) | |

| Dop-1d a | Wormbase | |

| G-protein | Gs (gsa-1) | Sanyal et al. (2004) |

| Gq (egl-30) | Chase et al. (2004) | |

| Second messenger | (↑) cAMP formation | Sanyal et al. (2004) |

| Effector | (↑) GIRK current | Sanyal et al. (2004) |

| Agonist | DA > NE > 5HT | Suo et al. (2002) |

| SKF38390, SCH23390 | Sanyal et al. (2004) | |

| Inverse agonist | Butaclamol | Sanyal et al. (2004) |

| Holoperidol | Sanyal et al. (2004) | |

| Flupenthixol | Sanyal et al. (2004) | |

| Cellular expression | PLM neurons | Sanyal et al. (2004) |

| PHC neurons | Sanyal et al. (2004) | |

| ALM neuron | Sanyal et al. (2004) | |

| RIM, AUA, and RIB | Sanyal et al. (2004) | |

| Cholinergic cells in ventral nerve cord | Chase et al. (2004) | |

| Mutant phenotype | ↑ Tap habituation | Sanyal et al. (2004) |

| DOP-4 | ||

| Gene products | dop-4 only | Sugiura et al. (2005) |

| G-protein | ? | |

| Second messenger | (↑) cAMP formation | Sugiura et al. (2005) |

| Effectors | ? | |

| Agonist | DA | Sugiura et al. (2005) |

| Antagonists | ? | |

| Cellular expression | Pharyngeal neurons (I1, I2) | Sugiura et al. (2005) |

| ASG, AVL, CAN, and PQR neurons | Sugiura et al. (2005) | |

| Vulva, intestine, rectal glands and epithelia, ray eight neurons (male tail) | Sugiura et al. (2005) | |

| Mutant phenotype | ? | |

| D2-like receptors | ||

| DOP-2 | ||

| Gene products | dop-2a (L) | Suo et al. (2003) |

| dop-2b (S) | Suo et al. (2003) | |

| G-protein | ? | |

| Second Messenger | (↓) cAMP formation | Suo et al. (2003) |

| Effector | ? | |

| Agonist (binding) | DA > 5HT > Tyr > NE > Oct | Suo et al. (2003) |

| Antagonist (binding) | Butaclamol, clozapine, CH23390, haloperidol, spiperone, chlorpromazine, sulpiride | Suo et al. (2003) |

| Antagonists (signaling) | Butaclamol | Suo et al. (2003) |

| Cellular expression | Dopamine neurons (ADEs, CEPs, and PDEs) | Suo et al. (2003) |

| Neurons in the male tail | Suo et al. (2003) | |

| Mutant phenotype | ? | |

| DOP-3 | ||

| Gene products | dop-3aa | Wormbase |

| dop-3b | Chase et al. (2004) | |

| dop-3c | Sugiura et al. (2005) | |

| dop-3d | Sugiura et al. (2005) | |

| G-protein | Go (goa-1) | Chase et al. (2004) |

| Second messenger | (↓) cAMP formation | Sugiura et al. (2005) |

| Effectors | DAG kinase (dgk-1)b | Chase et al. (2004) |

| RGS protein (eat-16) b | Chase et al. (2004) | |

| Agonist | DA >> Tyr > Oct | Sugiura et al. (2005) |

| Antagonists | ? | |

| Cellular expression | PVD Neuron | Chase et al. (2004) |

| GABA neurons in ventral nerve cord | Chase et al. (2004) | |

| Unidentified head neurons | Chase et al. (2004) | |

| Unidentified tail neurons | Chase et al. (2004) | |

| Body-wall muscle | Chase et al. (2004) | |

| Mutant phenotype | Defective basal slowing response | Chase et al. (2004) |

| ↓ DA induced paralysis | Chase et al. (2004) | |

aAs listed by homology modeling in wormbase (www.wormbase.org).

bData implied from in vivo function studies.

DA D1 receptors have been implicated in habituation to nose tap response (Rankin, 1991; Rankin and Broster, 1992; Rose and Rankin, 2001). Because dop-1 was found to be expressed in ALM and PLM neurons, tap habituation was tested in dop-1(ev748) mutants and habituation to non-localized tap response was tested (Sanyal et al., 2004). Dop-1 knockout animals were found to habituate faster to this response than wild type animals implying that dop-1 is important for maintenance of the avoidance response. Expression of dop-1 in sensory neurons using the mec-7 promoter rescued tap habituation in dop-1(ev748) animals indicating that DA signaling via DOP-1 in touch neurons is the critical determinant of nose touch habitutaion. Because ADE neurons synapse directly on a subset of these touch neurons (White et al., 1986) (ALM, AVA, and AVD) and ADE specific function was not tested in this study, it is difficult to determine whether ADE specific inputs or humoral DA reinstates this habituation.

Dop-2 DA Receptor (K09G1.4)

The C. elegans dop-2 receptor was originally identified by Suo et al. (2003) by homology searches using the mammalian D2 receptor as a template. RT-PCR studies revealed two dop-2 gene products that differ by 135 amino acids in the third intracellular loop (CeDop2L and CeDop2S). These isoforms are the only two predicted splice variants for this gene in C. elegans and will be referred to as dop-2a (CeDop-2S) and dop-2b (CeDop2L) according to worm nomenclature (Horvitz et al., 1979; Hodgkin, 1995). Importantly, alternative splicing of the D2 receptor at this location is also noted for mammalian isoforms (Dal Toso et al., 1989; Giros et al., 1989; Monsma et al., 1989).

Pharmacologically, DOP-2 preferentially binds DA over other biogenic amines. Both the dop-2a and dop-2b isoforms were expressed in COS-7 cells and biogenic amines were assayed for their ability to displace [125I]iodo-LSD. LSD displays high nM affinity for both isoforms (K D=6.6±0.6 nM for DOP-2b and 6.5±2.1 nM for DOP-2a) with DA displacing [125I]iodo-LDS with the highest potency (K i=2.98±.021 μM for DOP-2a and 2.24±.019 μM for DOP-2b). Displacement of [125I]iodo-LSD for other biogenic amines tested followed the same pattern for both isoforms with a rank order of potency for displacement that followed 5HT > tyramine > NE > octopamine (Table II). Antagonist profiles of [125I]iodo-LSD displacement for the two isoforms are almost indistinguishable with butaclamol showing the highest potency (∼35 nM for either DOP-2a or DOP-2b). To examine functional coupling to cAMP production, each of the two C. elegans dop-2 isoforms were transfected into CHO cells in combination with a commercially available vector (pCRE-Luc, Clontech) that displays increased luciferase activity in response to increase in cAMP levels. Addition of forskolin stimulated an increase in luciferase activity that could then be inhibited by DA (0.1 μM). Both DOP-2a and DOP-2b isoforms decreased this forskolin-induced activation in CHO cells; the EC50 value for AC inhibition was reported to be ∼74 nM for both DOP-2a and b, well below the K i calculated for DA at these receptors and well within a physiological range. This inhibition by DA was reversed by the addition of 10 μM butaclamol, consistent with binding inhibition studies (Suo et al., 2003).

Little is known of the behavioral contributions of dop-2. Exogenous DA increased the number of high angle turns. The mammalian D2 antagonist raclopride blocked this reinstatement of ARS, implying that DA is sufficient to activate this behavior. While raclopride is a specific D2 agonist in mammals, it is difficult to know what effect it may have on C. elegans receptors given the mixed pharmacology demonstrated by the cloned DOP receptors in response to mammalian antagonists (Suo et al., 2004). Future studies using dop-2 mutants may help clarify in vivo roles.

Dop-3 DA Receptor (T14E8.3)

A novel D2-like receptor was identified by Chase and colleagues based on sequence similarity to human D2 receptors (Chase et al., 2004). Initially, several potential genes with high homology to the human D2 receptor were identified. To narrow their search, TM domains from the human DA, 5HT, and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, along with the already identified DOP-1 and DOP-2 protein sequences, were aligned and compared to BLAST-based alignments of uncharacterized nematode homologs. Three genes clustered with both the human and C. elegans DA receptors (T14E8.3, C24A8.1, and C02D4.2) with T14E8.3 displaying the highest homology to the known C. elegans D2 receptor dop-2. T14E8.3 was therefore targeted for investigation and subsequently renamed dop-3. Isolation of the full-length clone using RT-PCR revealed that DOP-3 protein is most similar to human D2 receptors with 51% identity in putative transmembrane spanning domains and 38% identity overall. Alignment with the human D1 and D2 receptors reveals a large third intracellular loop and a small C-terminal tail, consistent with D2-like receptors. Four isoforms for dop-3 are predicted for the T14E8.3 locus (DOP-3a–d, see Table II). Comparison of the predicted amino acid sequences for each of these variants reveals that the isoform identified by Chase et al. most resembles DOP-3b. No splice variants were reported in this original publication however recent work reveals at least one more splice isoform is coded for by C. elegans.

Shortly after Chase et al. published their findings on dop-3b, Suguira and collegues reported two novel dop-3 splice variants, one which encoded a 590 amino acid receptor and another that encoded a truncated DOP-3 receptor (DOP-3nf) which lacked the sixth and seventh transmembrane domains normally predicted for the full length DOP-3 receptor (Sugiura et al., 2005). The first of these receptors coded for sequence predicted for dop-3c and is 18 amino acids shorter than the receptor reported by Chase and collegues. The second truncated isoform coded for a 245 amino acid receptor that corresponds to the length of the prediced dop-3d isoform.

To determine whether either of these proteins encoded a bona fide DA receptor, the individual isoforms were transfected into CHO cells in conjunction with a cAMP responsive luciferase reporter gene. The ability of different biogenic amines to reduce forskolin activated luciferase activity was tested on cells expressing the full-length DOP-3c isoform. DA displayed the most potent attenuation of forskolin induced luciferase expression, with an EC50 value of 5.57±0.13 μM. Tyramine and octopamine also decreased luciferase expression but at much higher concentrations. When DA was tested on cells expressing the truncated DOP-3d receptor isoform, no DA dependent inhibition of luciferase expression was reported indicating that this product may not function via adenlyate cyclase and cAMP pathways. Instead co-transfection of DOP-3d with DOP-3c reduced the EC50 value for dopamine, indicating that DOP-3d may act to blunt signaling by coupling to DOP-3c.

The intrinsic pharmacology of DOP-3b has not been characterized. Instead elegant genetic experiments have been conducted on knockout strains to determine the effects of dop-3 on DA-mediated behavior as discussed in more detail below. These behavioral experiments revealed that dop-1 and dop-3 expressed by cholinergic neurons work antagonistically to mediate DA-induced paralysis, utilizing different G-proteins to mediate their effects. Genetic dissection of DA signaling indicates that the DOP-3 pathway includes activation of the Goα protein GOA-1, the RGS protein EAT-16 (with its beta subunit gpb-2) and a diacylglycerol kinase (DGK-1). In these studies, Chase et al. isolated a dop-3 mutant line that displays reduced paralysis in response to exogenous DA (Chase et al., 2004). Expression of dop-3 was observed in both cholinergic and GABAergic cell bodies and paralysis in response to DA was rescued when dop-3 was expressed in cholinergic neurons using the acr-2 promoter (Chase et al., 2004). Screening for mutants with reduced paralysis in response to DA yielded four additional mutants including novel alleles of goa-1, dgk-1, eat-16, and gpb-2. Importantly, all of these genes function as downstream effectors of Goα and have been shown to negatively modulate Gqα responses in C. elegans (Hajdu-Cronin et al., 1999; Miller et al., 1999). These studies reinforce recent diversification of DA signaling pathways beyond simply modulation of cyclic nucleotides (Beaulieu et al., 2005).

To examine potential DA receptor interactions in the worm, dop-1 and dop-3 double mutants were generated. The dop-1;dop-3 double mutants paralyzed in DA, suggesting that the dop-1 knockout should be hypersensitive to DA in terms of slowing, a trend that was noted by Chase et al. (2004). Expression of dop-1 using acr-2 in the dop-3;dop-1 double mutant partially restored dop-3 resistance to paralysis, indicating that these receptors likely work antagonistically in cholinergic neurons to mediate DA effects. The fact, however, that the double mutant was still responsive to DA paralysis suggests that there is most likely another DA receptor in this pathway that acts via GOA-1 that has yet to be identified (Jorgensen, 2004). Regardless, these studies were the first to demonstrate DA signaling in C. elegans modulating behavior mediated by two antagonistic DA receptors via differential G-protein coupling, underscoring further similarities to mammalian actions of DA. With respect to other DA-supported behaviors, dop-3 but not dop-1 or dop-2 receptor knockouts alter basal slowing response in vivo suggesting that basal slowing mechanisms may engage signaling pathways similar to those engaged for modulation of basal motor activity (Chase et al., 2004). Chase et al. also remind us that actions of DA in the motor slowing circuit may arise from humoral actions of DA rather than from direct synaptic contacts (Chase et al., 2004).

Dop-4 DA Receptors (C52B11.3)

A novel D1 like DA receptor (dop-4) was cloned by Sugiura et al. using sequence homology to human DA receptors (Sugiura et al., 2005). RT-PCR using a C52B11.3 specific anti-sense primer coupled with splice leader sequence 1 (SL1) sense primer amplified a single transcript of 1.7 bp. HEK293 cells co-expressing this dop-4 cDNA with a cAMP responsive luciferase reporter construct was tested for alterations in luciferase levels in response to several biogenic amines. Only DA produced a significant increase in luciferase expression, indicating that this receptor acts to increase cAMP levels specifically upon DA stimulation. The increase in cAMP levels is consistent with D1-like activity, making DOP-4 the second D1-like dopamine receptor identified in C. elegans (Table II). Although this receptor was originally identified using homology searches to mammalian DA receptors, it clusters most with invertebrate DA receptors and may represent an invertebrate specific DA receptor. More pharmacology on this receptor should be pursued to determine differences and similarities between DOP-4 and mammalian D1-like receptors in terms of G-protein coupling and down stream effectors before this conclusion is solidified.

The expression of dop-4 was determined by fusing a 6.1 kb promoter sequence including sequence up to the middle of exon 2 with GFP. Fluorescence was noted in several pharangeal neurons (I1 and I2), and head neurons including ASG, AVL, CAN, and PQR. There was also reporter expression in vulva, intestine, rectal glands, and rectal epithelial cells. Expression was also seen in neurons projecting into ray 8 in the male tail. This expression profile suggests that this receptor may play a role in the regulation of pharyngeal pumping, chemosensation, defecation, oxygen sensing and male mating behavior (Sugiura et al., 2005).

Still More C. elegans DA Receptors?

Studies of receptor involvement in egg-laying behaviors noted above also suggests a role of as yet uncharacterized DA receptors. The D2 antagonists chlorpromazine, butaclamol, and haloperidol increase egg laying in wild type and egl-1 mutants but not in animals lacking DA and 5HT (cat-4(e1141)), implying that DA antagonism at a D2 like receptor may play a role in activation of egg laying behavior (Weinshenker et al., 1995). This DA receptor would have to reside in vulval muscle and effect potassium conductance through EGL-2. Although DOP-2 is inhibited by chlorpromazine, it is unlikely that the DOP-2 receptor mediates dopamine dependent inhibition of egg-laying since evidence indicates it is not expressed in any of the neurons that mediate egg-laying responses, nor is it found in muscle (Suo et al., 2003). Haloperidol acts as an inverse agonist on DOP-1 (chlorpromazine was not tested), however, dop-1 does not appear to be expression in muscle cells (Chase et al., 2004; Sanyal et al., 2004). As dop-3 is expressed in muscle, this receptor becomes an interesting candidate; however, dop-3 does not appear to be expressed in vulval muscle cells and no constitutive egg-laying was noted in the dop-3 mutants identified by Chase (D. Chase, personal communication). These findings suggest the existence of an unidentified DA and chlorpromazine/haloperidol-sensitive receptor that is linked to the egg-laying circuit.

The past 50 years of discoveries in catecholamine science has provided a rich literature, which to this day, provides a platform for novel catecholamine research. As new technologies and models such as the C. elegans system described here, are explored answers to old questions give rise to yet more possibilities. Catecholamine biologists now have an impressive tool kit, enhanced by the utilization of powerful genetic models that, in the coming years, will reveal novel partners and pathways supporting DA signaling and stimulate our thinking about DA disorders and therapies in man.

REFERENCES

- Axelrod, J. (1971). Noradrenaline: Fate and control of its biosynthesis. Science173:598–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu, J. M., Sotnikova, T. D., Marion, S., Lefkowitz, R. J., Gainetdinov, R. R., and Caron, M. G. (2005). An Akt/beta-arrestin 2/PP2A signaling complex mediates dopaminergic neurotransmission and behavior. Cell122:261–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, W. J. (1991). Searching Behavior : The Behavioral Ecology of Finding Resources, 1st edn. Chapman and Hall, London, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, S. (1974). The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics77:71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S., Gelwix, C. C., Caldwell, K. A., and Caldwell, G. A. (2005). Torsin-mediated protection from cellular stress in the dopaminergic neurons of Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 25:3801–3812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvelli, L., McDonald, P. W., Blakely, R. D., and Defelice, L. J. (2004). Dopamine transporters depolarize neurons by a channel mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA101:16046–16051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie, M., Sulston, J. E., White, J. G., Southgate, E., Thomson, J. N., and Brenner, S. (1985). The neural circuit for touch sensitivity in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 5:956–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase, D. L., Pepper, J. S., and Koelle, M. R. (2004). Mechanism of extrasynaptic dopamine signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Neurosci. 7:1096–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, M., Estevez, A., Yin, X., Fox, R., Morrison, R., McDonnell, M., Gleason, C., Miller, D. M., IIIrd, and Strange, K. (2002). A primary culture system for functional analysis of C. elegans neurons and muscle cells. Neuron. 33:503–514. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Consortium Ces (1998). Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: A platform for investigating biology. Science282:2012–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Toso, R., Sommer, B., Ewert, M., Herb, A., Pritchett, D. B., Bach, A., Shivers, B. D., and Seeburg, P. H. (1989). The dopamine D2 receptor: two molecular forms generated by alternative splicing. Embo. J. 8:4025–4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai, C., and Horvitz, H. R. (1989). Caenorhabditis elegans mutants defective in the functioning of the motor neurons responsible for egg laying. Genetics121:703–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai, C., Garriga, G., McIntire, S. L., and Horvitz, H. R. (1988). A genetic pathway for the development of the Caenorhabditis elegans HSN motor neurons. Nature336:638–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y., Nasif, F. J., Tsui, J. J., Ju, W. Y., Cooper, D. C., Hu, X. T., Malenka, R. C., and White, F. J. (2005). Cocaine-induced plasticity of intrinsic membrane properties in prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons: adaptations in potassium currents. J. Neurosci. 25:936–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerr, J. S., Frisby, D. L., Gaskin, J., Duke, A., Asermely, K., Huddleston, D., Eiden, L. E., and Rand, J. B. (1999). The cat-1 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans encodes a vesicular monoamine transporter required for specific monoamine-dependent behaviors. J. Neurosci. 19:72–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estevez, M., Estevez, A. O., Cowie, R. H., and Gardner, K. L. (2004). The voltage-gated calcium channel UNC-2 is involved in stress-mediated regulation of tryptophan hydroxylase. J. Neurochem. 88:102–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainetdinov, R. R., Sotnikova, T. D., and Caron, M. G. (2002). Monoamine transporter pharmacology and mutant mice. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 23:367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdeman, G. L., Partridge, J. G., Lupica, C. R., and Lovinger, D. M. (2003). It could be habit forming: drugs of abuse and striatal synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 26:184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giros, B., Jaber, M., Jones, S. R., Wightman, R. M., and Caron, M. G. (1996). Hyperlocomotion and indifference to cocaine and amphetamine in mice lacking the dopamine transporter. Nature379:606–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giros, B., Sokoloff, P., Martres, M. P., Riou, J. F., Emorine, L. J., and Schwartz, J. C. (1989). Alternative splicing directs the expression of two D2 dopamine receptor isoforms. Nature342:923–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J. M., Hill, J. J., and Bargmann, C. I. (2005). A circuit for navigation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA102:3184–3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajdu-Cronin, Y.M., Chen, W. J., Patikoglou, G., Koelle, M. R., and Sternberg, P. W. (1999). Antagonism between G(o)alpha and G(q)alpha in Caenorhabditis elegans: the RGS protein EAT-16 is necessary for G(o)alpha signaling and regulates G(q)alpha activity. Genes. Dev. 13:1780–1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D. H., and Hedgecock, E. M. (1991). Kinesin-related gene unc-104 is required for axonal transport of synaptic vesicles in C. elegans. Cell65:837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D. H., and Russell, R. L. (1991). The posterior nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: serial reconstruction of identified neurons and complete pattern of synaptic interactions. J Neurosci. 11:1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare, E. E., and Loer, C. M. (2004). Function and evolution of the serotonin-synthetic bas-1 gene and other aromatic amino acid decarboxylase genes in Caenorhabditis. BMC Evol. Biol. 4:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hills, T., Brockie, P. J., and Maricq, A. V. (2004). Dopamine and glutamate control area-restricted search behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 24:1217–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin, J. (1995). Genetic nomenclature guide. Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Genet.: 24–25. [PubMed]

- Hodgkin, J. (2001). What does a worm want with 20,000 genes?. Genome. Biol. 2:COMMENT2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Horvitz, H. R., Brenner, S., Hodgkin, J., and Herman, R. K. (1979). A uniform genetic nomenclature for the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 175:129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz, H. R., Chalfie, M., Trent, C., Sulston, J. E., and Evans, P. D. (1982). Serotonin and octopamine in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science216:1012–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, S. L., Prasad, B. M., and Amara, S. G. (2002). Dopamine transporter-mediated conductances increase excitability of midbrain dopamine neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 5:971–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi, L. D., Apparsundaram, S., Malone, M. D., Ward, E., Miller, D. M., Eppler, M., and Blakely, R. D. (1998). The Caenorhabditis elegans gene T23G5.5 encodes an antidepressant- and cocaine-sensitive dopamine transporter. Mol. Pharmacol. 54:601–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, E. M. (2004). Dopamine: should I stay or should I go now? Nat. Neurosci. 7:1019–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel, E. R., and Schwartz, J. H. (1982). Molecular biology of learning: modulation of transmitter release. Science218:433–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapatos, G., Hirayama, K., Shimoji, M., and Milstien, S. (1999). GTP cyclohydrolase I feedback regulatory protein is expressed in serotonin neurons and regulates tetrahydrobiopterin biosynthesis. J. Neurochem. 72:669–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilty, J. E., Lorang, D., and Amara, S. G. (1991). Cloning and expression of a cocaine-sensitive rat dopamine transporter. Science254:578–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koushika, S. P., and Nonet, M. L. (2000). Sorting and transport in C. elegans: aA model system with a sequenced genome. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12:517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]