Abstract

1. Nucleosides potentially participate in the neuronal functions of the brain. However, their distribution and changes in their concentrations in the human brain is not known. For better understanding of nucleoside functions, changes of nucleoside concentrations by age and a complete map of nucleoside levels in the human brain are actual requirements.

2. We used post mortem human brain samples in the experiments and applied a recently modified HPLC method for the measurement of nucleosides. To estimate concentrations and patterns of nucleosides in alive human brain we used a recently developed reverse extrapolation method and multivariate statistical analyses.

3. We analyzed four nucleosides and three nucleobases in human cerebellar, cerebral cortices and in white matter in young and old adults. Average concentrations of the 308 samples investigated (mean±SEM) were the following (pmol/mg wet tissue weight): adenosine 10.3±0.6, inosine 69.5±1.7, guanosine 13.5±0.4, uridine 52.4±1.2, uracil 8.4±0.3, hypoxanthine 108.6±2.0 and xanthine 54.8±1.3. We also demonstrated that concentrations of inosine and adenosine in the cerebral cortex and guanosine in the cerebral white matter are age-dependent.

4. Using multivariate statistical analyses and degradation coefficients, we present an uneven regional distribution of nucleosides in the human brain. The methods presented here allow to creation of a nucleoside map of the human brain by measuring the concentration of nucleosides in microdissected tissue samples. Our data support a functional role for nucleosides in the brain.

KEY WORDS: concentration of nucleosides, human brain areas

INTRODUCTION

Nucleosides and nucleoside derivatives have multiple roles in living organisms such as being building blocks of the genetic code, playing a central role in the metabolism, and transmitting information from one neuron to the other. In addition, nucleoside derivatives are widely used drugs as immunosuppressants (Major et al., 1981; Yu et al., 1981), anti-tumor agents (Macdonald, 1991; Hansen, 2002; Herrström et al., 2001), and anti-viral agents (Rachlis and Fanning, 1993; Borst et al., 2004). These drugs induce neurological symptoms in clinical applications (Dessi et al., 1995; Bialkowska et al., 2000; Ono-Yagi et al., 2000). In physiological conditions, adenosine modulates sleep, suppresses seizures and regulates cognition and memory (Radulovacki et al., 1984; Williams, 1990; Chen et al., 2000; Hauber and Bareiss, 2001).

Nucleoside metabolic pathways form a complex, interlinked network (Carrera et al., 1994; Brosh et al., 1996; Barsotti and Ipata, 2004). The closely related structures of nucleoside compounds results in different alternative conversion routes (Zimmermann, 1992; Brosh et al., 1996). The activity of nucleoside metabolising enzymes and adenosine-receptor density show regional differences as well as significant changes in the brain by aging (Brosh et al., 1990; Fuchs, 1991; Xu et al., 2005). The salvage of nucleosides is particularly important in the aging process because the high de novo nucleoside synthesis in neonates is continuously declining during the life (Allsop and Watts, 1983). There is no data on such changes in the brain so age-dependent changes in nucleoside concentrations in human are important questions. Furthermore, measuring the concentrations of nucleoside compounds in autopsies collected from diseased human brains might have diagnostic values. As a next step to address these issues, we investigated the distribution of nucleosides and nucleobases in human brain and correlated their concentrations with aging. To obtain data on age-dependent alterations in nucleoside concentrations, we measured their distribution in the cortex and white matter, then we compared nucleoside levels in brains of old and young subjects. Our study revealed an uneven distribution of nucleosides in the human brain and we also demonstrated differences in nucleoside concentrations between brains of young and old subjects. To attain our objectives we developed and validated a mathematical method for the analysis of neurochemical differences in human brain samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Standards for peak identification (uracil, hypoxanthine, xanthine, uridine, inosine, guanosine, adenosine) and other chemicals, reagents, standards, etc. were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and Merck Co. (Darmstadt, Germany) in 99% purity, analytical or HPLC grade.

HPLC Technique

A recently modified HPLC method for analysis of nucleosides from brain samples was applied (Dobolyi et al., 1998). Briefly, using diode array detector with a cooled column system allows better selectivity than the conventional HPLC methods. This method has been proved to be sensitive and selective enough for the measurement of uracil, hypoxanthine, xanthine, uridine, inosine, guanosine, adenosine, thymidine and deoxynucleosides in milligrams of brain tissue. Nucleosides were measured by HP 1100 series gradient chromatograph with diode array detector. The separation was performed on a HP Hypersil ODS C18, 2.1 mm×200 mm analytical column and a 2.1 mm×20 mm guard column. The flow rate was 300 μl/min. Eluent A was 0.02 M formiate buffer containing 0.55% (v/v) acetonitrile, pH 4.45 and eluent B was 0.02 M formiate buffer containing 40% (v/v) acetonitrile, pH 4.45. The gradient profile was the following: 0% B at 0–10 min, 10% B at 22 min, and 100% B at 30 min. The column temperature was 10°C. The injection volume was 10 μl. The diode array detector was adjusted so that it measured at 254 nm (reference wave 360 nm) and 280 nm (reference wave 450 nm). Chromatograms were evaluated by using the automatic integrator function of the HP Chemstation software. Some peaks, which were under the limit of the automatic integration, were measured manually.

Sample Preparation of Human Brain Samples for Chromatography

Human brain samples were collected in agreement with the Ethical Rules for Using Human Tissues for Medical Research in Hungary (HM 34/1999).

Brains from sudden death and traffic accident victims were investigated. Brains were removed from the skull within 2 h after death in the Department of Forensic Medicine, Faculty of Medicine of the Semmelweis University. Then, the brains were frozen and sliced at 1–1.5 mm thick coronal sections. Brain areas were microdissected by punch technique (Palkovits, 1973). Four areas were selected from cerebellum and eight from cerebrum including white matter and cortical areas. In total, 308 brain samples from 39 middle-aged subjects (59.1±1.9 years) were analyzed in the mapping study. In the aging study, we processed 20 tissue samples from five old (84±1.9 years) and five young (40.4±2.5 years) persons.

Our sample preparation method was adapted for measuring of nucleoside content of brain samples (Kovács et al., 2005). Briefly, about 1 mg from each microdissected tissue pellets were placed into 200 μl Beckman Airfuge tubes, which contained 20 μl of chromatographic eluent A. The tissue samples were homogenized with a motorized Teflon potter for 10 s. The homogenized samples were treated with 1000 W microwave beam for 10 s. The samples were then centrifuged at 10.000×g for 20 s. 10 μl out of the 60 μl supernatants were injected into the chromatograph. The concentrations were calculated to 1 mg wet tissue weight (w.w.).

Estimating the Nucleoside Content of the Post Mortem Samples by Back-Extrapolation

In order to determine the concentrations of nucleosides in the living state of the human brain we used a recently developed reverse extrapolation method (Kovács et al., 2005). It is based on a sequence of neurosurgically obtained human cerebral cortical samples with 30 s to 24 h post mortem delay. Briefly, the ratios of concentrations obtained at 30 s and at 2, 4, 6 and 24 h post mortem, respectively, were calculated and called as degradation or back-extrapolation coefficients. These ratios, applied to data from post mortem human tissues, were used in the present study to estimate the nucleoside concentrations in the living human brain tissue.

Classification of the Nucleoside Patterns

Varying anatomical and functional properties of the structures are likely to result in an uneven nucleoside distribution among brain structures. On the other hand, a nearly even nucleoside distribution is also possible because of the general uniformity of metabolic processes. To reveal the physiological nucleoside pattern and its interrelation with the large brain regions we applied statistical classification methods. Individual nucleoside concentrations did not show significant differences between anatomical structures while the whole nucleoside pattern, composed of the seven reliably detectable nucleosides, did. Therefore, we used the seven nucleoside concentrations of a sample together as a nucleoside vector in multivariate statistical analyses to “learn” the pattern of the nucleoside distribution in the brain.

To recognize the existence of region-specific nucleoside distributions in the brain we applied statistical classification methods. To avoid pursuing possibly irrelevant hypotheses on the data we performed an unsupervised machine learning procedure (cluster analysis) for the exploration of the nucleoside pattern classes. Unsupervised learning requires neither the pre-identification of the cluster membership nor the number of the clusters since all the necessary information is devised from the data by this powerful procedure (Sharma, 1996). This is why the composition of the emergent classes (clusters) is deeply rooted in the biological kinship of the member samples. The output of the applied amalgamation procedure is a hierarchical cluster structure yielding classes (clusters) of brain sample ensembles, which may correspond to well-defined brain structures.

The exploratory phase of the classification was followed by the verification of the cluster structure. Classification functions were developed by the aid of a hypothesis testing procedure, which was discriminant function analysis in the present instance. The classification (discriminant) functions allow the labeling (classification) of newly measured samples posteriorly, based only on their nucleoside concentration vector without knowing their brain location.

Mathematical details of the computations are discussed elsewhere (Mardia et al., 1979; Sharma, 1996; Hair et al., 1998) since it would exceed the frame of the present paper. A preprocessing procedure we did with the measured data is standardization. We used data with zero mean and standard deviation of unity for cluster and discriminant analyses. It was necessary because the nucleoside concentrations spun two orders of magnitude (e.g. the mean value of uracil was 8.4 while the mean of hypoxanthine was 108.6 pmol/mg w.w.).

RESULTS

Concentrations of Nucleosides in Human Brains

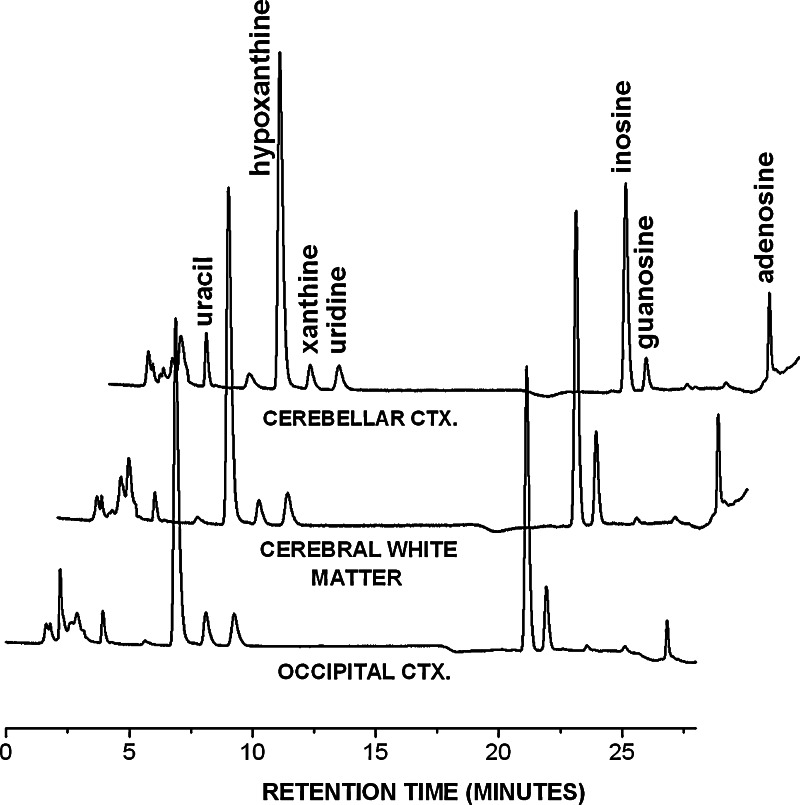

Four nucleosides (uridine, inosine, guanosine and adenosine) and three nucleobases (uracil, hypoxanthine, xanthine) were detectable in all human cerebellar, cerebral and white matter samples (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Chromatograms of representative samples from the cerebellar cortex (CEREBELLAR CTX.), cerebral white matter and occipital cortical areas (CEREBRAL WHITE MATTER, OCCIPITAL CTX) are shown. The UV absorbance values are normalised to 1 mg w.w. sample. Concentrations of several other nucleosides, like deoxyuridine, deoxyadenosine etc. were detectable in some but not all samples, therefore they were excluded from further statistical analysis. CTX: cortex.

At first, the average concentrations of the 308 samples (regardless to their anatomical locations) were calculated (mean±SEM). The average levels expressed in pmol/mg wet tissue weight (w.w.) were the following: uracil 8.4±0.3, hypoxanthine 108.6±2.0, xanthine 54.8±1.3, uridine 52.4±1.2, inosine 69.5±1.7, guanosine 13.5±0.4 and adenosine 10.3±0.6. To estimate the concentrations of nucleosides for the living state of human brains, back-extrapolation coefficients were used as described previously (Kovács et al., 2005). The coefficients as well as the post mortem and estimated physiological levels of nucleosides are shown on Table I.

Table I.

Measured (Post Mortem) and Estimated (Living State of Human Brain) Nucleoside Concentrations in the Human Brain Tissues

| Concentration (pmol/mg w.w.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleosides and | Back-extrapolation | ||

| their metabolites | coefficients | Post mortem | Living state of human brain |

| Uracil | 0.97 | 8.4 | 8.2 |

| Hypoxanthine | 0.56 | 108.6 | 60.8 |

| Xanthine | 0.68 | 54.8 | 37.3 |

| Uridine | 0.70 | 52.4 | 36.7 |

| Inosine | 1.21 | 69.5 | 84.1 |

| Guanosine | 1.09 | 13.5 | 14.7 |

| Adenosine | 0.89 | 10.3 | 9.2 |

Note. w.w.: wet weight.

Distribution Patterns of Nucleosides

The cluster hierarchy obtained by the statistical classification procedure (Fig. 2) shows three well distinguishable groups of samples when choosing the linkage distance cut-point equal to 2. (Picking the cut-point in amalgamation clustering is somewhat a matter of subjective interpretation. Subjectivity can, however, be diminished by the use of clustering techniques, such as screen diagram, and totally eliminated by statistical postprocessings such as discriminant function analysis). The biological identification of the clusters can serve as the ultimate verification of the uneven (non-random) nucleoside distribution. The three main clusters can, indeed, be identified as the cerebellum, the cerebral cortex and the white matter (of the cerebellum as well as of the cerebrum). Thus, we can conclude that while among these brain regions the nucleoside patterns are similar, between the regions there are characteristic dissimilarities considering the seven nucleosides together as a nucleoside vector. The discriminant analysis proved that all three clusters are significantly different (p < 0.001). It also opens the door to a visual interpretation of the similarity/dissimilarity of the cluster members by placing the samples in the three-dimensional (3D) discriminant function space (Fig. 2B). The proximity of the brain samples in this 3D space corresponds to the similarity of their nucleoside concentrations: long distances represent dissimilarity while short distances represent close similarity, so densely packed areas represent the clusters.

Fig. 2.

(A) The hierarchical cluster structure. Clusters: I: cerebellum, II: white matter, III: cerebral cortex; c: cortex, flocc.-nod l.: flocculo-nodular lobe, w: white matter, somatom. c.: somatomotor cortex, somatos. c.: somatosensory cortex. (B) The scatterplot of the brain samples in the three-dimensional discriminant function space. The clusters are the same as in (A). CTX: cortex.

Age-Dependence of Brain Nucleosides

The effect of the age of the subject on nucleoside and nucleobase concentrations was investigated in frontal cortical and pooled white matter samples. In the frontal cortex, inosine and adenosine levels were significantly higher in old (84±1.9 years) than in young (40.4±2.5 years) whereas the hypoxanthine level was lower in old than in young (Table II). In the white matter, the guanosine level was significantly lower in old than in young, whereas other nucleoside and nucleobase concentrations did not change.

Table II.

Estimated Concentrations of Nucleosides and Nucleobases in Cerebral Cortex and White Matter of Old and Young Alive Human Brain

| Concentrations of nucleosides and their metabolites (pmol/mg w.w.) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ura | Hyp | Xn | Urd | Ino | Guo | Ado | |

| Frontal c | |||||||

| Old | 6.4±0.7 | 59.2±2.5 | 41.1±3.0 | 45.2±1.7 | 111.3±5.0 | 18.7±0.9 | 11.0±2.8 |

| Young | 6.7±0.7 | 74.6±3.4 | 42.6±2.4 | 48.6±2.0 | 82.9±4.2 | 21.6±1.3 | 3.1±0.7 |

| Old/young | 0.96 | 0.79** | 0.97 | 0.93 | 1.34** | 0.87 | 3.55** |

| White m | |||||||

| Old | 9.7±1.3 | 58.1±5.4 | 36.6±2.9 | 30.5±2.2 | 78.1±7.2 | 8.7±0.3 | 12.0±2.0 |

| Young | 11.1±0.9 | 59.2±2.4 | 35.1±1.4 | 31.5±3.1 | 67.4±4.8 | 11.0±0.5 | 11.1±1.0 |

| Old/young | 0.87 | 0.98 | 1.04 | 0.97 | 1.16 | 0.79** | 1.08 |

| Old | |||||||

| Cortex | 6.4±0.7 | 59.2±2.5 | 41.1±3.0 | 45.2±1.7 | 111.3±5.1 | 18.7±0.9 | 11.0±2.8 |

| White m | 9.7±1.3 | 58.1±5.4 | 36.6±2.9 | 30.5±2.2 | 78.1±7.2 | 8.7±0.3 | 12.0±2.0 |

| Cortex/white m | 0.66* | 1.02 | 1.12 | 1.48** | 1.43** | 2.15** | 0.92 |

| Young | |||||||

| Cortex | 6.7±0.7 | 74.6±3.4 | 42.6±2.4 | 48.6±2.0 | 82.9±4.2 | 21.6±1.3 | 3.1±0.7 |

| White m | 11.1±0.9 | 59.2±2.4 | 35.1±1.4 | 31.5±3.1 | 67.4±4.8 | 11.0±0.5 | 11.1±1.0 |

| Cortex/white m | 0.60** | 1.26** | 1.21* | 1.54** | 1.23* | 1.96** | 0.28** |

Note. Frontal c.: frontal cortex; white m.: white matter; Ura: uracil, Hyp: hypoxanthine, Xn: xanthine, Urd: uridine, Ino: inosine, Guo: guanosine, Ado: adenosine. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005 level of significance.

In agreement with the result of the cluster analysis, the concentrations of several nucleosides and nucleobases differed between the frontal cortex, and the white matter. In the old group, the levels of uridine, inosine, and guanosine were higher in the frontal cortex than in the white matter, whereas uracil concentration was higher in the white matter than in the cortex. In the young group, the levels of hypoxanthine, xanthine, uridine, inosine, and guanosine were higher in the frontal cortex than in the white matter, whereas uracil and adenosine concentrations were higher in the white matter than in the cortex.

DISCUSSION

Methodological Considerations

The nucleoside concentrations shown in the Table I are average values of all tissue samples regardless of their anatomical locations, which explain their high variability. The high variability might be caused by different factors such as age, sex, activity of brain before death, smoking, drugs, etc. To decrease the variability we selected as homogeneous brain tissue samples as possible which had similar features (age, sex, cause of death, etc.).

On the basis of nucleoside back-extrapolation coefficients, we estimated the concentrations of nucleosides in the living state of the human brain. Our method reported previously (Kovács et al., 2005) allows the application of human brain bank materials for estimating the in vivo nucleoside levels using back-extrapolation coefficients and the comparison of nucleoside concentrations obtained at various times after death.

We revealed an uneven, sample origin-dependent nucleoside distribution in the human brain. We have found differences between the young and the old as well as between the cerebral cortex, the cerebellum and the white matter (irrespective of its location). All these findings were possible to be disclosed by using our elaborate statistical methodology based alone on multivariate statistical procedures.

In summary, an effective statistical classification methodology was presented to explore significant differences in neurochemical patterns. Furthermore, powerful discriminating functions were developed for the later identification of unclassified brain samples. This methodology can be applied to solve similar problems of feature extraction, machine learning and pattern identification having other complex biological data.

Uneven Regional Distribution of Nucleosides and Their Metabolites in the Human Cerebrum and Cerebellum

An uneven regional pattern of nucleoside concentrations is a major outcome of this study. A complexity of structural, functional and biochemical differences might be the reasons of regional differences. Anatomical correlates of regional differences in nucleoside levels in the brain might be related to different glia/neuron ratio in the tissue samples. The nucleoside metabolism is different in neurons and glial cells due to the different distribution (Phillips and Newsholme, 1979; Nagata et al., 1984; Norstrand et al., 1984; Berger et al., 1985; Ceballos et al., 1994) and activity (Meghji et al., 1989; Ceballos et al., 1994; Parkinson et al., 2002) of purine metabolic enzymes. The degradation of adenosine is faster in glia than in neuron (Ceballos et al., 1994). The glia/neuron ratio is low in the cortex and high in the white matter, which could cause different distribution of nucleosides. Furthermore, the glia/neuron ratio is also different in the cerebral cortex versus cerebellum (Ghandour et al., 1980; O’Kusky and Colonnier, 1982; Leuba and Garey, 1989), and the differences may be large even in different cerebral cortical areas (Diamond et al., 1985; Leuba and Garey, 1989). It has to be noted that the density of brain capillaries could also modify the concentration of nucleosides in different brain areas by effecting hypoxia-induced changes in the brain (Feng et al., 1988; Borowsky and Collins, 1989).

Age-Dependence of Brain Nucleoside Concentrations

We revealed age-dependence in hypoxanthine, inosine and adenosine levels in the cerebral cortex and guanosine concentrations in cerebral white matter (Table II). One explanation of age related changes in nucleoside and nucleobase concentrations could be the altered metabolism of nucleosides in aging brain. Our findings support changes in the nucleoside metabolism during aging (Suleiman and Spector, 1982; Eells and Spector, 1983; Fuchs, 1991). 5′-nucleotidase activity increases but the activity of adenosine-deaminase decreases by age (Fuchs, 1991; Pazzagli et al., 1995) and adenosine kinase is saturated in elderly people (Arch and Newsholme, 1978). Consequently, cortical adenosine content increases in old subjects. High concentration of inosine coincides with increased activity of 5′-nucleotidase (Fuchs, 1991) in the old brain. The low level of hypoxanthine in the aged cortex correlates with increased hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HGPRT) activity catalyzing nucleoside salvage (Zoref-Shani et al., 1995). The salvage of nucleosides is particularly important in aging brain (Allsop and Watts, 1983) because de novo nucleoside synthesis is declining during the lifespan (Allsop and Watts, 1983). Increased HGPRT (Zoref-Shani et al., 1995) and guanase (Zoref-Shani et al., 1995; Ciccarelli et al., 2001) activities have been observed during aging. Our data suggest that it results in significantly lower guanosine level in the old than in the young white matter. The significantly lower nucleoside levels in the old and young white matter compared to the cortex may be a correlation with higher glial nucleoside metabolism (Ceballos et al., 1994).

In conclusion, we present an uneven regional distribution of nucleosides in the human brain using multivariate statistical analyses. We demonstrated that the concentrations of inosine and adenosine in the cerebral cortex and that of guanosine in cerebral white matter are age-dependent. Our findings support the idea that the nucleoside microenvironment in the brain could be an important factor in aging process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was supported by MEDICHEM II., DNTTK RET Grant, and OTKA 044711 for G. Juhász and Neurobiology Research Group and OTKA T034496 for M. Palkovits and Bolyai Grant of HAS for K.A. Kékesi. A part of the study was supported by Scientific Foundation of BDF and NYRFT (NYD-18-1308-02/0C) for Zs. Kovács.

REFERENCES

- Allsop, J., and Watts, R. W. E. (1983). Purine de novo synthesis in liver and developing rat brain, and the effect of some inhibitors of purine nucleotide interconversion. Enzyme30:172–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arch, J. R. S., and Newsholme, E. A. (1978). Activities and some properties of 5′-nucleotidase, adenosine kinase and adenosine deaminase in tissues vertebrates and invertebrates in relation to the control of the concentration and the physiological role of adenosine. Biochem. J.174:965–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsotti, C., and Ipata, P. L. (2004). Metabolic regulation of ATP breakdown and of adenosine production in rat brain extracts. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol.36:2214–2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger, S. J., Carter, J. G. , and Lowry, O. H. (1985). Distribution of guanine deaminase in mouse brain. J. Neurochem.44:1736–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialkowska, A., Bialkowski, K., Gerschenson, M., Diwan, B. A., Jones, A. B., Olivero, O. A., Poirier, M. C., Anderson, L. M., Kasprzak, K. S., and Sipowicz, M. A. (2000). Oxidative DNA damage in fetal tissues after transplacental exposure to 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine (AZT). Carcinogenesis21:1059–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky, I. W., and Collins, R. C. (1989). Metabolic anatomy of brain: A comparison of regional capillary density, glucose metabolism, and enzyme activities. J. Comp. Neurol.288:401–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst, P., Balzarini, J., Ono, N., Reid, G., de Vries, H., Wielinga, P., Wijnholds, J., and Zelcer, N. (2004). The potential impact of drug transporters on nucleoside-analog-based antiviral chemotherapy. Antiviral Res.62:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosh, S., Sperling, O., Bromberg, Y., and Sidi, Y. (1990). Developmental changes in the activity of enzymes of purine metabolism in rat neuronal cells in culture and in whole brain. J. Neurochem. 54:1776–1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosh, S., Zoref-Shani, E., Danziger, E., Bromberg, Y., Sperling, O., and Sidi, Y. (1996). Adenine nucleotide metabolism in primary rat neuronal cultures. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol.28:319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, C. J., Saven, A., and Piro, L. D. (1994). Purine metabolism of lymphocytes. Targets for chemotherapy drug development. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am.8:357–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos, G., Tuttle, J. B., and Rubio, R. (1994). Differential distribution of purine metabolizing enzymes between glia and neurons. J. Neurochem.62:1144–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T. H. , Wang, M. F., Liang, Y. F., Komatsu, T., Chan, Y. C., Chung, S. Y., and Yamamoto, S. (2000). A nucleoside–nucleotide mixture may reduce memory deterioration in old senescence-accelerated mice. J. Nutr.130:3085–3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli, R., Ballerini, P., Sabatino, G., Rathbone, M. P., D’Onofrio, M., Caciagli, F., and Di Iorio, P. (2001). Involvement of astrocytes in purine-mediated reparative processes in the brain. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci.19:395–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessi, F., Pollard, H., Moreau, J., Ben-Ari, Y., and Charriaut-Marlangue, C. (1995). Cytosine arabinoside induces apoptosis in cerebellar neurons in culture. J. Neurochem. 64:1980–1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, M. C., Scheibel, A. B., Murphy, G. M. Jr., and Harvey, T. (1985). On the brain of a scientist: Albert Einstein. Exp. Neurol.88:198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobolyi, Á., Reichart, A., Szikra, T., Szilágyi, N., Kékesi, A. K., Karancsi, T., Slégel, P., Palkovits, M., and Juhász, G. (1998). Analysis of purine and pyrimidine bases, nucleosides and deoxynucleosides in brain microsamples (microdialysates and micropunches) and cerebrospinal fluid . Neurochem. Int.32:247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eells, J. T., and Spector, R. (1983). Identification, development, and regional distribution of ribonucleoside reductase in adult rat brain. J. Neurochem.40:1008–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z. C. Roberts, E. L. Jr., Sick, T. J., and Rosenthal, M. (1988). Depth profile of local oxygen tension and blood flow in rat cerebral cortex, white matter and hippocampus. Brain Res.445:280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, J. L. (1991). 5′-Nucleotidase activity increases in aging rat brain. Neurobiol. Aging12:523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghandour, M. S., Vincendon, G., and Gombos, G. (1980). Astrocyte and oligodendrocyte distribution in adult rat cerebellum: An immunohistological study. J. Neurocytol.9:637–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Tatham, R. L., Anderson, R. E., and Black, W. (1998). Multivariate Data Analysis. Prentice Hall.

- Hansen, S. W. (2002). Gemcitabine, platinum, and paclitaxel regimens in patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma. Semin. Oncol.29:17–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauber, W., and Bareiss, A. (2001). Facilitative effects of an adenosine A1/A2 receptor blockade on spatial memory performance of rats: Selective enhancement of reference memory retention during the light period. Behav. Brain Res.118:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrström, S. A., Wang, L., and Eriksson, S. (2001). Antiviral guanosine analogs as substrates for deoxyguanosine kinase: implications for chemotherapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.45:739–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, Zs., Kékesi, K. A., Bobest, M., Török, T., Szilágyi, N., Szikra, T., Szepesi, Zs., Nyilas, R., Dobolyi, Á., Palkovits, M., and Juhász, G. (2005). Post mortem degradation of nucleosides in the brain: Comparison of human and rat brains for estimation of in vivo concentration of nucleosides. J. Neurosci. Meth.148:88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuba, G., and Garey, L. J. (1989). Comparison of neuronal and glial numerical density in primary and secondary visual cortex of man. Exp. Brain Res.77:31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, D. R. (1991). Neurologic complications of chemotherapy. Neurol. Clin.9:955–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major, P. P., Agarwal, R. P., and Kufe, D. W. (1981). Deoxycoformycin: Neurological toxicity. Cancer Chemother. Pharm.5:193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardia, K. V., Kent, J. T., and Bibby, J. M. (1979). Multivariate Analysis (Probability and Mathematical Statistics). Academic Press.

- Meghji, P., Tuttle, J. B., and Rubio, R. (1989). Adenosine formation and release by embrionic chick neurons and glia in cell culture. J. Neurochem.53:1852–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata, H., Mimori, Y., Nakamura, S., and Kameyama, M. (1984). Regional and subcellular distribution in mammalian brain of the enzymes producing adenosine. J. Neurochem.42:1001–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norstrand, I. F., Siverls, V. C., and Libbin, R. M. (1984). Regional distribution of adenosine deaminase in the human neuraxis. Enzyme32:20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Kusky, J., and Colonnier, M. (1982). A laminar analysis of the number of neurons, glia, and synapses in the visual cortex (area 17) of adult macaque monkeys. J. Comp. Neurol.210:278–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono-Yagi, K., Ohno, M., Iwami, M., Takano, T., Yamano, T., and Shimada, M. (2000). Heterotopia in microcephaly induced by cytosine arabinoside: Hippocampus in the neocortex. Acta Neuropathol.100:403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovits, M. (1973). Isolated removal of hypothalamic or other brain nuclei of the rat. Brain Res.59:449–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, F. E., Sinclair, C. J. D., Othman, T., Haughey, N. J., and Geiger, J. D. (2002). Differences between rat primary cortical neurons and astrocytes in purine release evoked by ischemic conditions. Neuropharmacology43:836–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazzagli, M., Corsi, C., Fratti, S., Pedata, F., and Pepeu, G. (1995). Regulation of extracellular adenosine levels in the striatum of aging rats. Brain Res.684:103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, E., and Newsholme, E. A. (1979). Maximum activities, properties and distribution of 5′-nucleotidase, adenosine kinase and adenosine deaminase in rat and human brain. J. Neurochem.33:553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlis, A., and Fanning, M. M. (1993). Zidovudine toxicity. Clinical features and management. Drug Safety8:312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulovacki, M., Virus, R. M., Djuricic-Nedelson, M., and Green, R. D. (1984). Adenosine analogs and sleep in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.228:268–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S. (1996). Applied Multivariate Techniques. Wiley, New York, Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Suleiman, S. A., and Spector, R. (1982). Identification, development, and regional distribution of thymidilate synthase in adult rabbit brain. J. Neurochem.38:392–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M. (1990). Purine nucleosides and nucleotides as central nervous system modulators. Adenosine as the prototypic paracrine neuroactive substance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.603:93–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K., Bastia, E., and Schwarzschild, M. (2005). Therapautic potential of adenosine A2A receptor antagonists in Parkinson's disease. Pharmacol. Ther.105:267–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, A. L., Bakay, B., Kung, F. H., and Nyhan, W. L. (1981). Effects of 2′-deoxycoformycin on the metabolism of purines and the survival of malignant cells in a patient with T-cell leukemia. Cancer Res.41:2677–2682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, H. (1992). 5′-Nucleotidase: Molecular structure and functional aspects. Biochem. J.285:345–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoref-Shani, E., Bromberg, Y., Lilling, G., Gozes, I., Brosh, S., Sidi, Y., and Sperling, O. (1995). Developmental changes in purine nucleotide metabolism in cultured rat astroglia. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci.13:887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]