Abstract

1. Changes in the serotonergic (5-HT) system are suspected to play a role in stress-induced neuropathologies and neurochemical measures indicate that serotonergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) are activated during stress. In the present study we analyzed gene expression in the DRN after chronic social stress using subtractive cDNA hybridization.

2. In the resident intruder paradigm, male Wistar rats were chronically stressed by daily social defeat during 5 weeks, RNA was isolated from their DRN, cDNA was generated, and subtractive hybridization was performed to clone sequences that are differentially expressed in the stressed animals.

3. From the cDNA libraries that were obtained, we selected the following genes for quantitative Real-time PCR: Two genes related to neurotransmission (synaptosomal associated protein 25 and synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2b), a glial gene presumptively supporting neuroplasticity (N-myc downstream-regulated gene 2), and a gene possibly related to stress-induced regulation of transcription (CREB binding protein). These four genes were upregulated after the chronic social stress. Quantitative Western blotting revealed increased expression of synaptosomal associated protein 25 and synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2b.

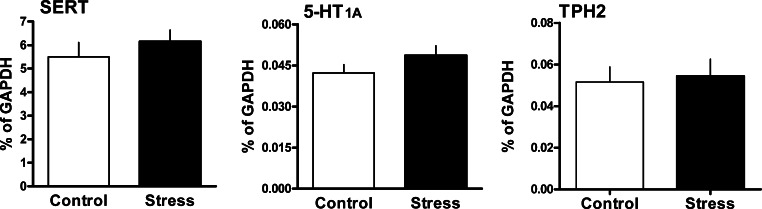

4. Genes directly related to 5-HT neurotransmission were not contained in the cDNA libraries and quantitative Real-time PCR for the serotonin transporter, tryptophan hydroxylase 2 and the 5-HT1A autoreceptor confirmed that these genes are not differentially expressed after 5-weeks of daily social stress.

5. These data show that 5 weeks of daily social defeat lead to significant changes in expression of genes related to neurotransmission and neuroplasticity in the DRN, whereas expression of genes directly related to 5-HT neurotransmission is apparently normal after this period of chronic stress.

KEY WORDS: dorsal raphe, gene expression, serotonin, neurotransmission, synaptic plasticity, social stress

INTRODUCTION

Chronic stress is known to have many adverse effects on the central nervous system and may lead to psychopathologies such as depression (Kendler et al., 1999; McEwen, 2002). Several data indicate that stress activates serotonergic (5-HT) neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN), the largest nucleus of the brainstem 5-HT nuclei containing about 50% of the serotonergic neurons in the rat CNS (Wiklund and Björklund, 1980). This activation increases 5-HT release in target areas of the DRN (Palkovits et al., 1976; see Chaouloff, 2000; Kirby et al., 1997), but stress effects on 5-HT neurons in the DRN appear to depend on the type of stress and its duration. Restraint stress followed by social isolation as well as eight weeks of ultra-mild stress lead to desensitization of 5-HT1A autoreceptors (Laaris et al., 1999; Lanfumey et al., 1999). An acute immobilization stress did not affect serotonin transporter (SERT) mRNA in the DRN but only in the raphe pontis, but repeated immobilization upregulated expression of trytophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1) mRNA in rat DRN (Vollmayr et al., 2000; Chamas et al., 1999, 2004). However, although it is known that in humans social stress, especially when chronic, may precipitate affective disorders and in spite of the key role of the serotonergic system in these diseases there have so far been no reports on gene expression in the DRN after chronic social stress. Studies in another species, the male tree shrew, revealed no effect of chronic social stress on 5-HT1A autoreceptor expression in the DRN (Flügge, 1995). In the present study, we analyzed whether chronic social stress changes expression of genes in the DRN.

Exposure to an inescapable stress is considered as a stressful life event that may lead to psychopathologies, and experimental social defeat paradigms have relatively high face validity for depression in humans (Koolhaas et al., 1990; Willner et al., 1995; Fuchs and Flügge, 2002). Therefore, to induce chronic social stress in male Wistar rats, we employed a recently developed model that uses daily social defeat by an aggressive dominant male to induce behavioral and physiological alterations in the defeated animal (Koolhaas et al., 1990, 1997; Rygula et al., 2005). In this rat model, daily social defeat by the dominant induces characteristic stress symptoms in the subordinate such as increased adrenal weight reflecting hyperactivity of the hypothalamus-pituitary adrenal axis, reduced locomotor and exploratory behavior, impaired sucrose preference behavior, prolonged immobility time in the forced swimming test and reduced body weight gain (Rygula et al., 2005). Since these stress-induced symptoms are most pronounced after 5 weeks of stress, the present study reports on gene expression in the DRN after 5 weeks of daily social defeat.

To find target genes that might be differentially regulated by chronic social stress in the DRN we used subtractive cDNA hybridization, a hypothesis-free method that allows identification of candidate genes that are differentially regulated by stress (Alfonso et al., 2004a). This technique is based on the principal that mRNA transcripts from the DRN of the two groups of animals are transcribed to cDNA and that then, all cDNA sequences that are equally present in stressed and control animals are eliminated by hybridization, whereas transcripts that are present in excess in stress or control animals will be cloned. We purified mRNA from DRN of chronically stressed and control animals and generated two cDNA libraries containing sequences that were potentially regulated by the stress. From these libraries, we selected genes according to their functions for further quantitative analysis. Because stress is known to activate central nervous neurotransmission we determined expression of two genes involved in neurotransmission (synaptosomal associated protein 25 kD, SNAP-25, and synaptic vesicle protein 2b, SV2b) using Real-time PCR. Furthermore, SNAP-25 and SV2b protein expression was determined by quantitative immunoblotting. To get an insight whether also glial genes might contribute to chronic social stress-induced changes in the DRN, we also quantified mRNA of N-myc downstream-regulated gene 2 (NDRG2) that is expressed in astrocytes (Nichols, 2003). The gene for CREB binding protein (CBP) was also contained in the cDNA library after subtractive hybridization. Because CBP plays a role in activation of the transcription factor CREB that is known to be regulated by stress and supposed to play role in psychopathologies (Nibuya et al., 1996; Dowlatshahi et al., 1998) we also analyzed expression of CBP mRNA. Furthermore, expression of three genes directly related to serotonin neurotransmission but not contained in the subtractive cDNA libraries, the 5-HT1A autoreceptor, TPH2 and SERT, was also quantified by Real-time PCR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental Animals

Experimentally naive male Wistar rats (Harlan-Winkelmann, Borchen, Germany) weighing 180–200 g at the time of arrival were used for the study. They were housed individually in type III macrolon cages, with rat chow and water available ad libitum. The animal facility was maintained at 21°C with a reversed 12 h:12 h light/dark cycle (lights off at 10.00 am). After arrival, animals were habituated to the conditions for two weeks and handled daily (control phase). All experimental manipulations were performed during the dark phase of the light/dark cycle under dim red light. Animal experiments were conducted according to the European Council Directive of November 24, 1986 (86/609/ECC), and were approved by the Government of Lower Saxony, Germany.

Chronic Social Stress

Two groups of male Wistar rats were analyzed, controls and stress (3 rats/group for generation of the subtractive cDNA library, and 8 rats/group for quantification of gene expression). Chronic social stress was induced as described before with the exception that wild-type rats were used as residents (Rygula et al., 2005). Wild-type rats (Rattus norvegicus WTG; age ∼4 months, body weight 450±6.6, mean±SEM) were a generous gift from Dr. J. Koolhaas (University of Groningen, The Netherlands). These rats have been originally wild-trapped and bred for several generations in Dr. J. Koolhaas’ laboratory under pathogen-free conditions (see Sgoifo et al., 1999). In the resident-intruder paradigm that took place under dim red light, the experimental (Wistar) rat was introduced into the home cage of the unfamiliar aggressive wild-type male. These residents (wild-type males) were paired with sterilized females and housed in large plastic cages (60 cm×40 cm×40 cm=l×w×h) located in a separate room, kept under the same conditions as the Wistar rats. Before the start of the social defeat procedure, the female resident rats were removed from the cages. Each experimental male Wistar rat (intruder) was then transferred from its home cage to the resident's cage for one hour. Usually within 1–3 min, the intruder was attacked and defeated by the resident, as shown by freezing behavior and submissive posture, whereupon intruder and resident were separated. For the rest of the hour, the intruder was kept in a small wire-mesh compartment (25 cm×15 cm×15 cm) within the resident's cage to be protected from direct physical contact but remaining in olfactory, visual and auditory contact with the resident. Thereafter, intruders were returned to their home cages. Animals from the stress group were subjected to social defeat daily for five weeks. To avoid individual differences in intensity of the defeat, the intruders were confronted each day with a different resident. Control animals were handled daily throughout the entire experiment. Handling consisted of picking up each rat, transferring it to the experimental room and returning it to its home cage.

Body weight was measured regularly at 12:00 am (two hours after lights off), first at the end of the control phase (baseline), then at weekly intervals (weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) during the stress phase. Body weight gain was calculated as percentage of individual baseline body weight at the beginning of the experiment (initial baseline values were transformed to the percentages of the baseline mean value). At the end of the experiment, animals were sacrificed, brains and adrenals were dissected and adrenal weights calculated as percentage of body weight.

Dissection of Brains

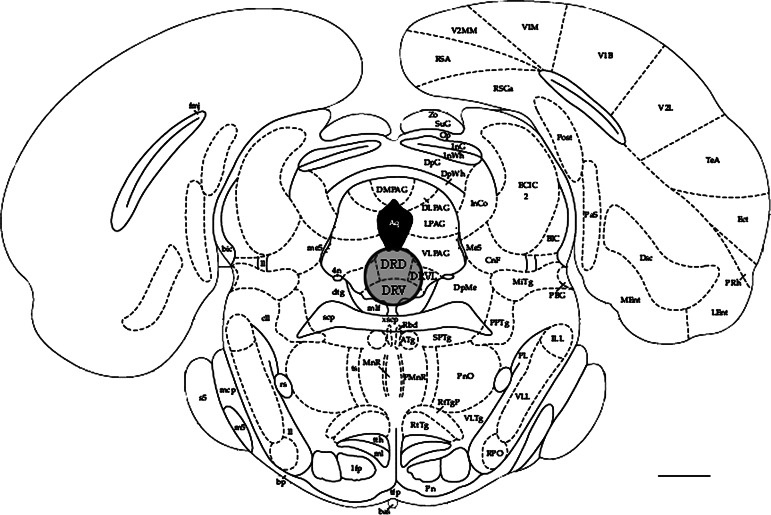

Animals were decapitated 24 h after the last stress exposure. Brains were quickly removed, dissected into two parts by a cut perpendicular to the cortical surface along the caudal side of the hippocampus. The caudal part was immediately frozen over liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C until use. Tissue from the dorsal raphe nucleus was obtained according to the method of Palkovits (1973). The caudal part of the brain was positioned on the specimen holder of a cryostat (at –18°C), and tissue was cut in caudal to rostral direction until −8.00 from bregma (Paxinos and Watson, 1986; Fig. 1). At this level, a pre-cooled sharpened hypodermic needle (inner diameter 1.3 mm, −20°C) was punched 1 mm deep into the DRN. This depth corresponds to the maximal caudo-rostral extension of the DRN. RNA was immediately isolated (see below).

Fig. 1.

Schematic drawing of the anatomical level at which the DRN was punched out. The caudal part of the brain was positioned on the specimen holder of a cryostat (at –18°C), and tissue was cut in caudal to rostral direction until −8.00 from bregma. DRN tissue was then punched out using a pre-cooled sharpened hypodermic needle (inner diameter 1.3 mm, −20°C) going 1 mm deep into the tissue (shaded areae). DRD, nucleus raphe dorsalis part dorsalis; DRV, nucleus raphe dorsalis part ventralis. DRVL, nucleus raphe dorsalis part ventrolateralis. Adapted from Paxinos and Watson, 1986. Scale bar =1 mm.

Construction of Subtractive cDNA Hybridization Library and Analysis of the Clones

For generation of cDNA libraries, mRNA was purified from pooled DRN of 3 control and 3 stressed male Wistar rats and two custom-subtracted cDNA libraries were constructed using the PCR-Select™ cDNA subtraction kit according to the manufacturer's manual (Clontech, Heidelberg, Germany), and as described before (Alfonso et al., 2004a). The efficiency of the subtraction procedure was evaluated according to the manufacturer's instructions using primers for the housekeeping gene GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase). Transcripts of the GAPDH gene were entirely subtracted during hybridization suggesting that this gene is not differentially expressed under our experimental conditions. Clones (containing inserts ≥100 bp) were sequenced using standard Hot Shot procedure (SEQLAB Sequence Laboratories GmbH, Göttingen, Germany). After sequencing, the non-vector sequences were used to search the public databases using the default databases search BLASTN (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/), the non-redundant nucleotide databases constructed from the Entrez databases (the National Center for Biotechnology Information, NCBI). Prior to the BLASTN analysis, we removed the flanking nested primers keeping only the inserted sequences in order to avoid false BLASTN hits. Identified clones were compared among each other to detect and remove redundant clones. The remaining clones were compared to public databases for identification of the genes or the proteins represented by the cloned sequences.

Analysis of mRNA by Real-Time PCR

To quantify mRNA in the DRN of stressed and control male Wistar rats, tissue dissected from DRN of individual animals (n=8 per group) was homogenized in Trizol® reagent (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) for isolation of total RNA. DNase I digestion was performed and the total RNA was purified using phenol/chloroform/isoamylalcohol followed by isopropyl/sodium acetate precipitation. The integrity and quantity of the RNA was checked using RNA 6000 Nano LabChip® kit (Agilent Technologies, Böblingen, Germany). RNA was reverse-transcribed with Superscript II (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). Primer sequences for target genes were designed using Primer Express software v2.0 (Application-based primer design software, Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). Amplicons were 50–150 bp long. We selected the primers that amplify sequences close to the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of the target genes (Table I). Amplicons were amplified using 7500 Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) with QuantiTect™ SYBR® Green PCR (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). A heat dissociation protocol was performed in order to verify that the SYBR green dye detected only one PCR product (Ririe et al., 1997). Experiments were performed in triplicates for each cDNA sample using two independently generated cDNA templates. All samples were normalized against the house keeping gene GAPDH. The threshold cycle for each gene was determined and the percentage of the relative abundance of each gene to the GAPDH for each animal was calculated as described previously (Peirson et al., 2003).

Table I.

Primer Sequences Used in the Real-time PCR Experiments

| Gene name | Forward primer sequence | Reverse primer sequence |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | TGCCCCCATGTTTGTGATG | TGGTGGTGCAGGATGCATT |

| SNAP-25 | CCATCTCCCTGT GGTTTGTCA | CAGCAATTTGGTTGTGCATAGC |

| SV2b | CGTTCGCTGTTCATGATGTGTT | AGAAGCAACTCCCAAAGAAGCC |

| CBP | TGTCCCGATAACGAGCTGATG | CTTGGAGATGCCCACAGAGTTC |

| NDRG2 | GAGATGGTGGCCAGTGAAGAAC | AATGCCCCTGCTTCAATGTG |

| SERT | TCTGAAAAGCCCCACTGGACT | TAGGACCGTGTCTTCATCAGGC |

| 5-HT1A | GTCCTGCCTTTCTGTGAAAGCA | TATGGCACCCAACAACGCA |

| TPH2 | TGAGAACCCCAAATCCTGCA | CCCAGCCAACAGACCTAACTGA |

Quantitative Immunoblotting

Total protein extracts from the DRN was obtained from the phenolic phase of the pooled Trizol homogenates after RNA isolation according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples from each group were pooled and proteins were precipitated with isopropyl alcohol and then washed with 0.3 M guanidine hydrochloride in 95% ethanol. The pellet was dissolved in 1% SDS and protein concentration was measured using modified Lowry method (Stoscheck, 1990). The concentrations of total protein loaded on the gel was adjusted so that the respective protein (SNAP-25 or SV2b) yielded a clearly visible band. For analysis of SNAP-25, 0.3 μg total proteins from DRN of stressed and control animals, respectively, were boiled in Laemmli buffer, loaded and separated on 12% SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, protein was transferred to nitrocellulose membrane from the gel. The membrane was blocked with 5% BSA in TBS (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.6) overnight at 4°C. Following blocking, the membrane was washed with TBS-T (TBS, 0.05% Tween 20), then incubated with the primary anti-SNAP-25 antibody (dilution 1:10000, Synaptic Systems, Göttingen, Germany) for 2 h at room temperature. Thereafter, the membrane was washed with TBS-T and incubated with peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse secondary antibody (dilution 1:3000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., California, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. After further washing and drying, the membrane was subjected to enhanced chemiluminescence amplification (ECL) and the bands were visualized on Hyperfilm™ ECL films according to the manufacturer's manual (Amersham Bioscience Ltd, UK). For SV2b, 30 μg of total protein were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. After blotting, the membrane was incubated with anti-SV2b primary antibody (dilution 1:1000, Synaptic Systems) followed by peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibody (dilution 1:7500, DakoCytomation, Denmark). The simultaneous detection of β-actin using mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (dilution 1:2000, Sigma, Taufkirchen. Germany) served as internal loading control for quantification of optical density of the bands. The relative optical density of bands on the ECL films was quantified using the AIS40 imaging software (Imaging System Inc., St. Catherines, Canada). Optical density of bands was calculated as percentage of the relative optical density of the band in the control animals (3 independent experiments).

Statistics

All data were tested for normality (95% confidence interval). Group means of stressed animals and controls were analyzed using two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test with the aid of Graph Pad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc. San Diego, USA). Body weight data were analyzed using ANOVA for repeated measurements with two factors (stress versus control × weeks, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test. Results are presented as mean±SEM. A probability level of 95% chosen to determine statistical significance (p<0.05).

RESULTS

Body and Adrenals Weight

Stressed rats gained less body weight than control rats (Table II). Statistical analyses revealed a significant effect of the stress [F (1)=60.39, p<0.0001] and significant stress × time interaction [F (5)=4.55, p=0.001]. Subsequent Bonferroni post-hoc tests confirmed significant reduction in the percentage of body weight gain in stressed animals after 2, 3, 4 and 5 weeks of social stress, as compared with the control group (Table II). At the end of the experiment, adrenal weight (expressed as relative body weight) was significantly increased in stressed animals: Stress, 0.0134±0.0007; controls, 0.0110±0.0004; p<0.05. These data show that the daily social defeat is stressful for the animals.

Table II.

Body Weight Gain Expressed as Percentage of the Initial (Baseline) Body Weight in Daily Stressed Animals and Controls (n=8/group) During the 5 Experimental Weeks

| Experimental week | Control | Stress | Significant difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18.17±0.75 | 14.29±0.84 | — |

| 2 | 31.60±0.91 | 24.27±1.44 | p < 0.05 |

| 3 | 45.89±1.22 | 36.63±1.64 | p < 0.001 |

| 4 | 54.60±1.81 | 44.97±1.67 | p < 0.001 |

| 5 | 64.83±4.11 | 50.48±1.19 | p < 0.001 |

Statistical differences were analyzed using two factorial ANOVA for repeated measurements followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test. data are presented as mean±SEM.

Subtractive cDNA Libraries Enriched in Stress Regulated Genes

To identify new genes potentially involved in stress-induced activation of DRN neurons we performed subtractive cDNA hybridization. We generated two cDNA libraries from pooled tissue of the DRN of chronically stressed rats and controls and sequenced 247 clones (the average insert length ∼200 bp) from the libraries (forward and reverse). Sequences were compared against public databases both at the DNA and the protein level. We found that 68% of the obtained sequences codify known proteins or genes, 2% encode ESTs published in at least one database, 13% are novel sequences matching only human or mouse genome, and 17% are novel sequences that do not match with any public database. The sequences matching known proteins or genes (168 sequences) were compared against each other for redundancy, and we found that they match 36 genes/proteins. Assigning the known genes to functional groups resulted in 8 main categories: Extracellular matrix proteins, proteins related to ion transport, cell energy/metabolism, protein synthesis and degradation, signal transduction including kinases, synaptic and other proteins related to neurotransmission, transcription factors, and RNA and DNA binding proteins. Genes that could not be classified were included as miscellaneous (Table III).

Table III.

Identified Sequences Cloned After Subtractive cDNA Hybridization (Libraries with Genes Potentially Up or Downregulated by Chronic Social Stress). Sequences were Classified According to Functional Aspects

| Accession number | Gene name |

|---|---|

| Extracellular matrix | |

| XP_342327 | Procollagen, type XI, alpha 1a |

| NM_031583 | Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 6a |

| NM_012656 | Secreted acidic cysteine rich glycoprotein, osteonectin (SPARC)a |

| Ions concentration | |

| NM_134363 | Solute carrier family12, member 5 (potassium/chloride transporter)a |

| NM_017290 | ATPase, Ca2+ transporting, cardiac muscleb |

| Energy | |

| M64496 | Cytochrome c oxidase polypeptide IIa |

| P00159, J01436 | Cytochrome ba |

| NM_145783 | Cytochrome c Va-subunita |

| AAN77603 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit 4a |

| NM_139325 | Neuron-specific enolase (NSE)a |

| Protein synthesis and/or degradation | |

| XM_221325 | Translation initiation factor 4A, isoform 2, eIF-4AIIa |

| NM_031978 | 26S proteasome, subunit p112 (PSMD1)a |

| NM_031106, BC059132 | Ribosomal protein L37a |

| NM_012876 | Ribosomal protein S29a |

| NM_031706, XM_237702 | 40S Ribosomal protein S8a |

| NM_031108 | ribosomal protein S9b |

| Signal transduction and kinases | |

| NM_133583 | N-myc downstream-regulated gene 2 (NDRG2)a |

| U36444 | PCTAIRE-1 kinasea |

| XM_341764 | Protein phosphatase 2 (formerly 2A), regulatory subunit A (PR 65), alpha isoform (Ppp2r1a)a |

| NM_053723 | LanC-like 1 lanthionin synthaseb |

| Synaptic proteins and neurotransmission | |

| NM_030991 | Synaptosomal associated protein (SNAP-25)a |

| NM_057207, AF372834 | Synaptic vesicle glycoprotein protein 2b (SV2b)a |

| X70496, Q08326 | GDP-releasing protein; guanine nucleotide releasing protein; Mss4 protein (guanine nucleotide exchange factor MSS4, RAB interacting factor)a |

| Transcription regulation | |

| AY462245 | CREB binding protein (CBP)a |

| A23692 | CCAAT-binding, chain A1a |

| RNA and DNA binding | |

| XM_223190 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D-like; A+U-rich element RNA binding factora |

| XM_216420 | DNA polymerase epsilon p17 subunita |

| Miscellaneous | |

| XM_217436 | Danj homologue (Hsp 40) superfamily B member 2, neuronal DANJ like 1a |

| NM_133544 | Diabetes associated protein in insulin sensitive tissuea |

| AF439750 | Myelin basic proteina |

| NM_013015 | Brain prostaglandin D2 synthasea |

| XM_340768 | RIKEN cDNA 0610007p22 similar to hypothetical proteina |

| XM_225699 | Similar to hypothetical protein (LOC307249)a |

| XM_486647 | Dedicator of cytokinesis 11 (Dock11)a |

| Q63199 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 6 precursora |

| XM_214061 | Ab2-450 T-cell activation proteinb |

aUpregulated genes.bDownregulated genes.

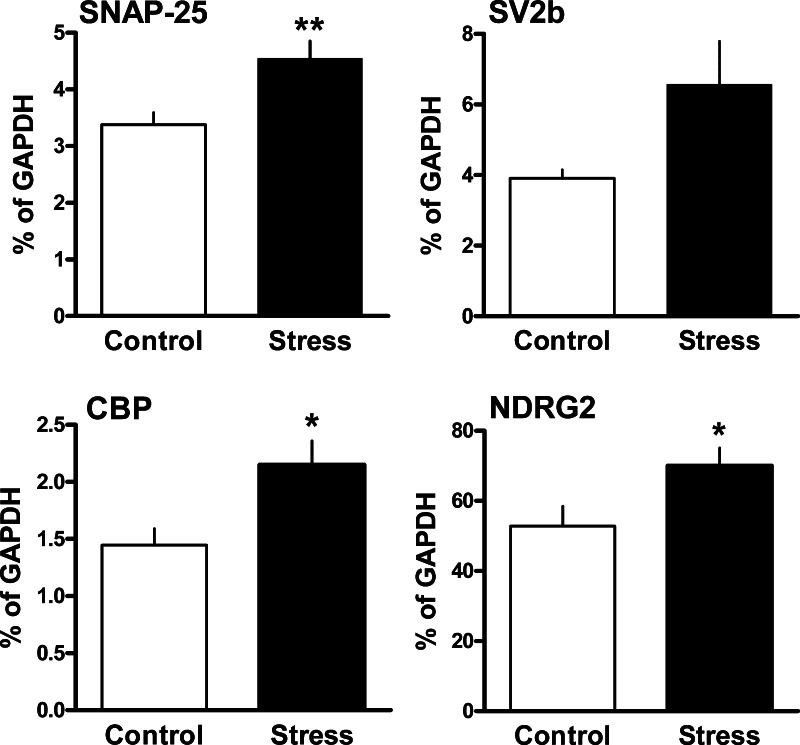

Genes Regulated by Stress in the DRN

From the cDNA libraries with sequences potentially up or downregulated by the chronic stress we selected 4 genes according to their functions, 2 related to synaptic mechanisms, SNAP-25 and SV2b, the astrocytic gene NDRG2, and CBP. We analyzed expression of these genes by quantitative Real-time PCR. The mRNA levels for the following genes were found to be increased in DRN of the Wistar rats after 5 weeks of daily social defeat (Fig. 2): SNAP-25 (by 35%), SV2b (by 67%), CBP (by 49%) and NDRG2 (by 31%). Statistical analysis using t-test showed significant effects of stress on mRNA expression for 3 genes: SNAP-25 [t (14)=3.09, p<0.01], CBP [t (14)=2.76, p<0.05] and NDRG2 [t (14)=2.35, p<0.05]. SV2b showed a trend towards increased expression in stressed animals [t (14)=2.13, p=0.051] (Fig. 2). Expression of genes directly related to 5-HT neurotransmission, 5-HT1A, TPH2 and SERT mRNA, was not significantly changed by the chronic social stress (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Effect of chronic social stress on expression of genes in the DRN: Synaptosomal associated protein 25 kD (SNAP-25), synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2b (SV2b), CREB binding protein (CBP) and N-myc down-stream regulated gene 2 (NDRG2). Data were generated with Real-time PCR. Transcript expression is presented as percentage of mRNA for the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Significant differences between stressed and control animals are indicated by asterisks (n=8/group; two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test; * p<0.05;** p<0.01). SV2b showed a trend towards increased expression in stressed animals (p=0.051). Data are expressed as mean±SEM.

Fig. 3.

Expression of serotonin related genes, serotonin transporter (SERT), 5-HT1A autoreceptor (5-HT1A) and tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (TPH2) after chronic social stress. Data were generated by Real-time PCR. Transcript expression is presented as percentage of mRNA for the housekeeping gene GAPDH (n=8/group). No significant differences were found. Data are expressed as mean±SEM.

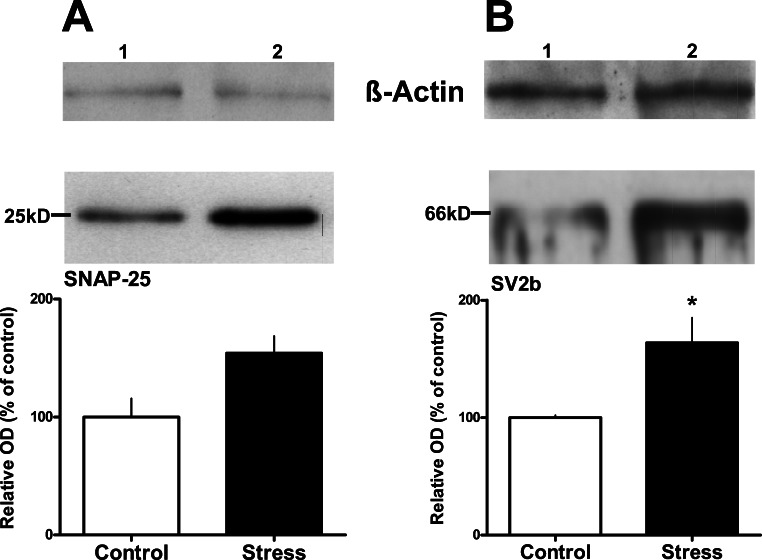

Quantitative Immunoblotting

Expression of SNAP-25 and SV2b proteins was quantified by Western blot analysis. The blotting membrane revealed one clear band for SNAP-25 in the molecular range of the protein (25 kD; Fig. 4), and chronic social stress increased the optical density of this band (by 54%). However, the difference between the bands of stressed animals and controls determined in three independent experiments was not significant (p=0.065). For SV2b, a strong band of the expected molecular weight (66 kD) was detected, showing the common electrophoretic pattern of the glycoprotein SV2b (see Discussion). The optical density of the 66 kD band was significantly increased after stress (by 64%; p<0.05; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Western blot analysis revealed that chronic social stress (5 weeks) increases expression of (A) synaptosomal associated protein 25 (SNAP-25) and (B) synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2b (SV2b). Equal amount of total proteins from pooled DRN of controls (lane 1) and stressed animals (lane 2) were loaded. An anti-ß-actin antibody was used for control (upper panel in A & B). For each protein, the relative optical density (OD) of the bands was determined and presented as percentage of the respective band for the control animals (n=8/group). Results were obtained from 3 independent experiments for each protein and presented as mean±SEM. Two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test was performed; * p<0.05. The difference in the SNAP-25 protein expression did not reach statistical significance (p=0.065).

DISCUSSION

Stressful life events such as social defeat induce neuroadaptive changes related to the degree and the specificity of a stressor (Miczek et al., 1991; de Kloet et al., 1998; McEwen, 2000). Already a brief social defeat changed gene expression in discrete regions of the rat brain (Martinez et al., 1998; Chung et al., 2000). The present study provides insight into the modulatory processes within the DRN neural network in response to chronic social stress. We show that expression of genes involved in neurotransmission and/or neuroplasticity, SNAP-25, SV2b, CBP and NDRG2, is upregulated by 5 weeks of daily social defeat in the dorsal raphe nucleus of male rats. According to our knowledge this is the first study that explores gene expression in the DRN in response to chronic social stress. We used subtractive hybridization, a method that allows identification of genes whose mRNA is differentially expressed under distinct experimental conditions (Alfonso et al., 2005). The present Real-time PCR data show that even transcripts showing a low level of differential expression such as NDRG2 mRNA can be identified with this method.

We found that SNAP-25 is regulated by chronic social stress in the DRN. This soluble protein is directly involved in neurotransmitter release in that it plays a key role in fusion of synaptic vesicles with the terminal plasma membrane (Sollner et al., 1993). In the course of the fusion process, interaction of the synaptic vesicle proteins with the target plasma membrane proteins leads to formation of an intermediate complex that is stabilized by SNAP-25 (Bock and Scheller, 1999; Chen et al., 1999; Fiebig et al., 1999). SNAP-25 was shown to play a role in axonal growth in vitro, and it has been suggested that high levels of this protein in specific regions of the adult brain contribute to nerve terminal plasticity (Osen-Sand et al., 1993). It is possible that the stress-induced upregulation of SNAP-25 both at the mRNA and the protein level, reflects a facilitation of neurotransmitter release.

SV2b was also upregulated by chronic social stress in the DRN. Using Western blotting, an enhanced expression of SV2B was observed in the DRN after chronic social stress. SV2b protein is involved in neurotransmitter release in that it regulates the readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles and their exocytosis (Janz et al., 1999; Xu and Bajjalieh, 2001). It has been reported that SV2b forms a complex with synaptotagmin 1, and this protein complex also contains SNAP-25 (Lazzell et al., 2004). The slight tailing of the bands representing the SV2b protein has been observed before. It is most likely due to aggregation of SV2b upon denaturing the samples before loading onto the gel (Bajjalieh et al., 1994). The stress-induced upregulation of SV2b expression supports the hypothesis that chronic stress leads to presynaptic changes in DRN neurons. These might have occurred in serotonergic as well as non-serotonergic neurons because SNAP-25 as well as SV2b are expressed in different types of neurons (Oyler et al., 1992; Bajjalieh et al., 1994). However, since approximately 30% of the cells in the DRN are serotonergic (Descarries et al., 1982) one can assume that at least part of the amount of SNAP-25/SV2b mRNA represents enhanced expression of theses genes in serotonergic neurons. Vesicle-containing dendrites (Descarries et al., 1982), dendro-dendritic synapses (Chazal and Ralston, 1987) and collaterals of serotonergic axons have been observed in the DRN (Beaudet and Descarries, 1981), which most probably contain SNAP-25 and SV2b proteins. However, it remains to be elucidated whether the changes in the analyzed transcripts occur in the serotonergic or in non-serotonergic neurons of the DRN and whether the presumptive changes in neurotransmission have consequences for 5-HT release in target regions where these neurons project to.

NDRG2 is a member of the astrocytic N-myc downstream-regulated gene family (NDRG 1-4) with putative supportive roles in neuronal differentiation, synapse formation and axon survival in the developing and adult nervous system (Zhou et al., 2001; Nichols, 2003). A potential role of NDRG2 in proper neuronal functioning including synaptic plasticity has been postulated (Nichols, 2003). NDRG2 was found to be upregulated in astrocytes in response to corticosterone treatment in the hippocampus of adrenalectomized rats (Nichols and Finch, 1994; Nichols et al., 1994; Nichols, 2003). The present data revealing increased NDRG2 expression in the DRN may suggest glia-mediated processes of plasticity (Nichols et al., 2005). Also in the hippocampus, an increase in the density of GFAP-immunoreactive astrocytes has been observed after one week of activity-stress (Lambert et al., 2000). On the basis of several post mortem studies it was concluded that glial structures are also changed in subjects with psychiatric disorders (Ongur et al., 1998; Cotter et al., 2002; Stark et al., 2004). Therefore, our data may suggest that stress-related neuropathologies are accompanied by glia changes in the DRN.

CBP is a conserved transcriptional adaptor protein which contains histone acetyltransferase activity that links transcription with chromatin remodeling (Goodman and Smolik, 2000). CBP is of particular interest because its recruitment is essential for the activity of the transcription factor CREB after phosphorylation (Mayr and Montminy, 2001). CREB itself is considered to have neuroprotective functions (Lonze et al., 2002), is regulated by antidepressants (Nibuya et al., 1996), and apparently plays a role in the neuropathology of mood disorders as indicated by a post mortem study in humans (Dowlatshahi et al., 1998). Future studies are required to investigate whether the stress-induced increase in CBP expression as detected in the present study might be related to enhanced CREB activity.

The concept that stress activates the serotonergic system would imply alterations in expression of genes directly related to regulation of 5-HT release in the DRN. It can be assumed that mRNA isolated from this nucleus contains a high number of transcripts related to 5-HT neurotransmission because approximately one third of the neurons in the DRN are serotonergic (Descarries et al., 1982). However, sequences of those genes could not be found in the cDNA library after subtractive hybridization suggesting that expression of genes directly related to 5-HT neurotransmission is not changed after five weeks of chronic social stress, or that there are only minor alterations that cannot be detected by subtractive hybridization. However, on the bases of the other changes in gene expression observed here one may assume that a 30% change is enough to detect the respective transcripts after subtractive hybridization. To verify whether expression of genes related to 5-HT neurotransmission was really unaffected after 5 weeks of chronic social stress we performed Real-time PCR experiments. No significant alteration in SERT, TPH2 and 5-HT1A autoreceptor transcript expression was detected. There might be two explanations for these findings: First, expression of these molecules is really not regulated by the social stress, or second, expression was regulated by stress but the effect disappeared in the course of the chronic stress period. However, in another chronic social stress paradigm using a non-rodent species, the male tree shrew (Fuchs and Flügge, 2002), an autoradiography study with the radiolabeled agonist 8-OH-DPAT showed no change in 5-HT1A autoreceptor number in the DRN at different time points in the course of a 4-weeks social stress period, but only a decrease in affinity of the receptors (Flügge, 1995). This may support the first hypothesis that there is no transient change in 5-HT1A receptor expression during chronic social stress. However, further investigations are still needed to verify this hypothesis in the rat chronic social stress model. In coincidence with the above observations in tree shrews, desensitization of 5-HT1A autoreceptors was also observed after 8 weeks of mild stress in mice (Lanfumey et al., 1999). Altogether, these findings may suggest that in the serotonergic neurons of the DRN, the response of 5-HT1A autoreceptors to stressful events is restricted to changes in receptor affinity resulting in altered agonist sensitivity, but does not include alterations in expression of 5-HT1A autoreceptor mRNA.

Expression of SERT was also found to be unchanged in the DRN after 5 weeks of social stress in the rat DRN. However in mice, 10 days of social defeat upregulated SERT mRNA in a larger brain stem region defined as ‘area of raphe nuclei’ (Filipenko et al., 2002). It is possible that the difference between these and our present data is due to the fact that we selectively punched out the DRN for isolation of transcripts. In this context it is interesting to note that after acute immobilization stress in rats, SERT mRNA expression was found to be unchanged in the DRN but downregulated in the raphe pontis (Vollmayr et al., 2000).

It has been shown that transcripts of tryptophan hydroxylase isoform 1 (TPH1) are enhanced after 3 and 7 days of repeated immobilization stress in rats (Chamas et al., 1999, 2004). However, the role of TPH1 in brain 5-HT biosynthesis is under debate because mice genetically deficient for TPH1 (tph−/−) had normal 5-HT levels in the brain stem and exhibited no significant behavioral deficits (Walther et al., 2003). It has been concluded that the presumptive link between TPH1 gene expression and polymorphisms with respect to mood disorders has to be reconsidered (Walther et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2004). For this reason in our present study, we designed primers for the TPH2 transcript which is abundant in the brain (Walther et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2004). Expression of TPH2 transcripts was found to be unchanged after 5 weeks of chronic social stress. In coincidence with the present data, chronic sound stress lasting up to 6 weeks increased TPH activity in the cortex but not in the brain stem (Boadle-Biber et al., 1989). From these data one may conclude that after a chronic stress period, expression of genes directly involved in presynaptic mechanisms of 5-HT neurotransmission in the DRN is relatively stable. However, in the present model we still cannot exclude the possibility of any transient response in those transcripts (SERT, TPH2 and 5-HT1A) that might have occurred during the 5 weeks experimental period.

In the present experiments, the cDNA libraries of differentially expressed genes contained several sequences from the mitochondrial genome. A presumptive increase in expression of mitochondrial genes could represent auxiliary mechanisms in order to increased energy availability for the neurons in response to the continuous energy demand, e.g. due to enhanced neurotransmitter release. The importance of mitochondria for synaptic plasticity has been addressed (Li et al., 2004). Also the ‘stress-hormones’ cortisol and corticosterone, respectively, regulate expression of mitochondrial genes in the hippocampus when administered chronically (Alfonso et al., 2004b; Datson et al., 2001). The hippocampal mossy fiber terminals that are occupied by large numbers of mitochondria were enlarged after chronic stress (Magariños et al., 1997). It is interesting to note that also chronically administered antidepressants increased mRNA levels of the mitochondrial gene for cytochrome b in mouse cerebral cortex (Huang et al., 1997) and cytochrome c oxidase mRNA in the rat hippocampus (Drigues et al., 2003). The observation that effects of chronic stress and antidepressants on expression of certain mitochondrial genes go in the same direction may support the hypothesis that upregulation of these genes reflects increased energy demands (Wong et al., 2004).

The cDNA libraries contained sequences encoding extracellular matrix (ECM) components suggesting that chronic stress differentially regulates expression of these molecules. Alterations in the extracellular matrix components occur in the context of synaptic plasticity, in inflammatory processes and may be associated with brain pathologies including dementia-associated diseases (Rauch, 2004). Some of the ECM components may affect neural plasticity and cellular functions by binding to other ECM elements such a osteonectin (Sweetwyne et al., 2004). Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans may affect neural plasticity through binding to cell surface molecules (Maurel et al., 1994).

In conclusion, the present data show that in the DRN, five weeks of daily social defeat upregulate expression of genes involved in synaptic functions and neuroplasticity indicating effects of chronic social stress on neurotransmission in the DRN. However, since expression of genes directly involved in regulation of 5-HT release was apparently unchanged it remains to be determined whether the chronic stress-induced changes in neurotransmission took place in serotonergic or in non-serotonergic neurons.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through the DFG-Research Center for Molecular Physiology of the Brain (CMPB). N. Abumaria receives a Georg-Christoph-Lichtenberg thesis grant from the Government of Lower Saxony and is enrolled in the MS/PhD Program Neurosciences at the University of Goettingen. We are grateful to Prof. Dr. Jaap Koolhaas for providing us with wild-type rats, to Dr. Julieta Alfonso for help with the subtractive hybridization technique and to Dr. Boldizsar Czeh for helpful discussion. The excellent technical assistance of Stefanie Gleisberg and Anna Hoffmann is also gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations:

- CBP

CREB-binding protein

- DRN

dorsal raphe nucleus

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- 5-HT1A receptor

5-Hydroxytryptamine 1A receptor

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- NDRG2

N-myc downstream-regulated gene 2

- SERT

serotonin transporter

- SNAP-25

synaptosomal associated protein 25-kD

- SV2b

synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2b

- TPH

tryptophan hydroxylase

REFERENCES

- Alfonso, J., Pollevick, G. D., Van der Hart, M. G., Flügge, G., Fuchs, E., and Frasch, A. C. C. (2004a). Identification of genes regulated by chronic psychosocial stress and antidepressant treatment in the hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci.19:659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso, J., Aguero, F., Sanchez, D. O., Flügge. G., Fuchs, E., Frasch, A. C., and Pollevick, G. D. (2004b). Gene expression analysis in the hippocampal formation of tree shrews chronically treated with cortisol. J. Neurosci. Res.78:702–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso, J., Frasch, A. C., and Flügge, G. (2005) Chronic stress, depression and antidepressants: effects on gene transcription in the hippocampus. Rev. Neurosci.16:43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajjalieh, S. M., Frantz, G. D., Weimann, J. M., McConnell, S. K., and Scheller, R. H. (1994). Differential expression of synaptic vesicle protein 2 (SV2) isoforms. J. Neurosci.14:5223–5235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudet, A., and Descarries, L.. (1981). The fine structure of central serotonin neurons. J. Physiol. (Paris) 77:193–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boadle-Biber, M. C., Corley, K. C., Graves, L., Phan, T. H., and Rosecrans, J. (1989). Increase in the activity of tryptophan hydroxylase from cortex and midbrain of male Fischer 344 rats in response to acute or repeated sound stress. Brain Res.482:306–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock, J. B., and Scheller, R. H. (1999). SNARE proteins mediate lipid bilayer fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.96:12227–12229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamas, F., Serova, L., and Sabban, E. L. (1999). Tryptophan hydroxylase mRNA levels are elevated by repeated immobilization stress in rat raphe nuclei but not in pineal gland. Neurosci. Lett.267:157–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamas, F. M., Underwood, M. D., Arango, V., Serova, L., Kassir, S. A., Mann, J. J., and Sabban, E. L. (2004). Immobilization stress elevates tryptophan hydroxylase mRNA and protein in the rat raphe nuclei. Biol. Psychiatry55:278–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaouloff, F. (2000). Serotonin, stress and corticoids. J. Psychopharmacol.14:139–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazal, G., and Ralston, H. J. 3rd. (1987). Serotonin-containing structures in the nucleus raphe dorsalis of the cat: an ultrastructural analysis of dendrites, presynaptic dendrites, and axon terminals. J. Comp. Neurol.259:317–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. A., Scales, S. J., Patel, S. M., Doung, Y. C., and Scheller, R. H. (1999). SNARE complex formation is triggered by Ca2+ and drives membrane fusion. Cell97:165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, K. K., Martinez, M., and Herbert, J. (2000). c-fos expression, behavioural, endocrine and autonomic responses to acute social stress in male rats after chronic restraint: modulation by serotonin. Neuroscience95:453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter, D., Mackay, D., Chana, G., Beasley, C., Landau, S., and Everall, I. P. (2002). Reduced neuronal size and glial cell density in area 9 of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in subjects with major depressive disorder. Cereb. Cortex12:386– xsxs94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datson, N. A., van der Perk, J., de Kloet, E. R., and Vreugdenhil, E. (2001). Identification of corticosteroid-responsive genes in rat hippocampus using serial analysis of gene expression. Eur. J. Neurosci.14:675–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descarries, L., Watkins, K. C., Garcia, S., and Beaudet, A. (1982). The serotonin neurons in nucleus raphe dorsalis of adult rat: a light and electron microscope radioautographic study. J. Comp. Neurol.207:239–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowlatshahi, D., MacQueen, G. M., Wang, J. F., and Young L. T. (1998). Increased temporal cortex CREB concentrations and antidepressant treatment in major depression. Lancet352:1754–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drigues, N., Poltyrev, T., Bejar, C., Weinstock, M., and Youdim, M. B. (2003). cDNA gene expression profile of rat hippocampus after chronic treatment with antidepressant drugs. J. Neural Transm.110:1413–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiebig, K. M., Rice, L. M., Pollock, E., and Brunger, A. T. (1999). Folding intermediates of SNARE complex assembly. Nat. Struct. Biol.6:117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipenko, M. L., Beilina, A. G., Alekseyenko, O. V., Dolgov, V. V., and Kudryavtseva, N. N. (2002). Repeated experience of social defeats increases serotonin transporter and monoamine oxidase A mRNA levels in raphe nuclei of male mice. Neurosci. Lett.321:25–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flügge, G. (1995). Dynamics of central nervous 5-HT1A-receptors under psychosocial stress. J. Neurosci.11:7132–7140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, E., and Flügge, G. (2002). Social stress in tree shrews: effects on physiology, brain function, and behavior of subordinate individuals. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav.73:247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R. H., and Smolik, S. (2000). CBP/p300 in cell growth, transformation, and development. Genes Dev.14:1553–1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, N. Y., Strakhova, M., Layer, R. T., and Skolnick, P. (1997). Chronic antidepressant treatments increase cytochrome b mRNA levels in mouse cerebral cortex. J. Mol. Neurosci.9:167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz, R., Goda, Y., Geppert, M., Missler, M., and Sudhof, T. C. (1999). SV2A and SV2B function as redundant Ca2+ regulators in neurotransmitter release. Neuron.24:1003–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler, K., Karkowski, L., and Prescott, C. (1999). Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry156:837–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, L. G., Chou-Green, J. M., Davis, K., and Lucki, I. (1997). The effects of different stressors on extracellular 5-hydroxytryptamine and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid. Brain Res.760:218–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet, E., Vreugdenhil, E., Oitzl, M., and Joels, M. (1998). Brain corticosteroid receptor balance in health and disease. Endocr. Rev.19:269–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas, J. M., Hermann, P. M., Kemperman, C., Bohus, B. van den Hoofdakker, R. H., and Beersma, D. G. M. (1990). Single social defeat in male rats induces a gradual but long lasting behavioral change: a model of depression. Neurosci. Res. Commun.7:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas, J. M., De Boer, S. F., De Rutter, A. J., Meerlo, P., and Sgoifo, A. (1997). Social stress in rats and mice. Acta. Physiol. Scand. Suppl.640:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laaris, N., Le Poul, E., Laporte, A. M., Hamon, M., and Lanfumey, L. (1999). Differential effects of stress on presynaptic and postsynaptic 5-hydroxytryptamine-1A receptors in the rat brain: an in vitro electrophysiological study. Neuroscience91:947–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, K. G., Gerecke, K. M., Quadros, P. S., Doudera, E., Jasnow, A. M., and Kinsley, C. H. (2000). Activity-stress increases density of GFAP-immunoreactive astrocytes in the rat hippocampus. Stress3:275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfumey, L., Pardon, M. C., Laaris, N., Joubert, C., Hanoun, N., Hamon, M., and Cohen-Salmon, C. (1999). 5-HT1A autoreceptor desensitization by chronic ultramild stress in mice. Neuroreport10:3369–3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzell, D. R., Belizaire, R., Thakur, P., Sherry, D. M., and Janz, R. (2004). SV2B regulates synaptotagmin 1 by direct interaction. J. Biol. Chem.279:52124–52131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z., Okamoto, K., Hayashi, Y., and Sheng, M. (2004). The importance of dendritic mitochondria in the morphogenesis and plasticity of spines and synapses. Cell119:873–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonze, B. E., Riccio, A., Cohen, S., and Ginty, D. D. (2002). Apoptosis, axonal growth defects, and degeneration of peripheral neurons in mice lacking CREB. Neuron34:371–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magariños, A. M., Verdugo, J. M., and McEwen, B. S. (1997). Chronic stress alters synaptic terminal structure in hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.94:14002–14008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, M., Phillips, P. J., and Herbert, J. (1998). Adaptation in patterns of c-fos expression in the brain associated with exposure to either single or repeated social stress in male rats. Eur. J. Neurosci.10:20–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel, P., Rauch, U., Flad, M., Margolis, R. K., and Margolis, R. U. (1994). Phosphacan, a chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan of brain that interacts with neurons and neural cell-adhesion molecules, is an extracellular variant of a receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.91:2512–2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr, B., and Montminy, M. (2001). Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.2:599–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, B. S. (2000). Effects of adverse experiences for brain structure and function. Biol. Psychiatry48:721–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, B. S. (2002). Sex, stress and the hippocampus: allostasis, allostatic load and the aging process. Neurobiol. Aging23:921–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek, K. A., Thompson, M. L., and Tornatzky, W. (1991). Subordinate animals: behavioral and physiological adaptations and opioid tolerance. In: Brown M. R., Koob G. F., and Rivier, C. (eds.), Stress: neurobiology and neuroendocrinology, Marcel Dekker, New York, pp. 323–357. [Google Scholar]

- Nibuya, M., Nestler, E. J., and Duman, R. S. (1996). Chronic antidepressant administration increases the expression of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) in rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci.16:2365–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, N. R., Masters, J. N., and Finch, C. E. (1994). Cloning of steroid-responsive mRNAs by differential hybridization. Methods Neurosci.22:296–313. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, N. R., and Finch, C. E. (1994). Gene products of corticosteroid action in hippocampus. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci.746:145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, N. R. (2003). NDRG2, a novel gene regulated by adrenal steroids and antidepressants, is highly expressed in astrocytes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.1007:349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, N. R., Agolley, D., Zieba, M., and Bye, N. (2005). Glucocorticoid regulation of glial responses during hippocampal neurodegeneration and regeneration. Brain Res. Rev.48:287–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongur, D., Drevets, W. C., and Price, J. L. (1998). Glial reduction in the subgenual prefrontal cortex in mood disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.95:13290–13295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osen-Sand, A., Catsicas, M., Staple, J. K., Jones, K. A., Ayala, G., Knowles, J., Grenningloh, G., and Catsicas, S. (1993). Inhibition of axonal growth by SNAP-25 antisense oligonucleotides in vitro and in vivo. Nature364:445–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyler, G. A., Polli, J. W., Higgins, G. A., Wilson, M. C., and Billingsley, M. L. (1992). Distribution and expression of SNAP-25 immunoreactivity in rat brain, rat PC-12 cells and human SMS-KCNR neuroblastoma cells. Dev. Brain Res.65:133–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovits, M. (1973). Isolated removal of hypothalamic or other brain nuclei of the rat. Brain Res.59:449–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovits, M., Brownstein, M., Kizer, J. S., Saavedra, J. M., and Kopin, I. J. (1976). Effect of stress on serotonin concentration and tryptophan hydroxylase activity of brain nuclei. Neuroendo.22:298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos, G., and Watson, C. (1986). The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press Inc., San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- Peirson, S. N., Butler, J. N., and Foster, R. G. (2003). Experimental validation of novel and conventional approaches to quantitative Real-time PCR data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res.31:e73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, U. (2004). Extracellular matrix components associated with remodeling processes in brain. Cell. Mol. Life Sci.61:2031–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ririe, K. M., Rasmussen, R. P., and Wittwer, C. T. (1997). Product differentiation by analysis of DNA melting curves during the polymerase chain reaction. Anal. Biochem.245:154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rygula, R., Abumaria, N., Flügge, G., Fuchs, E., Rüther, E., and Havemann-Reinecke, U. (2005). Anhedonia and motivational deficits in rats: Impact of chronic social stress. Behav. Brain Res.162:127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgoifo, A., Koolhaas, J. M., Musso, and E., De Boer S. F. (1999) Different sympathovagal modulation of heart rate during social and nonsocial stress episodes in wild-type rats. Physiol. Behav.67:733–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollner, T., Whiteheart, S. W., Brunner, M., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Geromanos, S., Tempst, P., and Rothman, J. E. (1993). SNAP receptors implicated in vesicle targeting and fusion. Nature362:318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark, A. K., Uylings, H. B., Sanz-Arigita, E., and Pakkenberg B. (2004). Glial cell loss in the anterior cingulate cortex, a subregion of the prefrontal cortex, in subjects with schizophrenia. Am. J. Psych.161:882–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoscheck, C. M. (1990). Quantitation of protein. Methods in Enzymology182:50–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetwyne, M. T., Brekken, R. A., Workman, G., Bradshaw, A. D., Carbon, J., Siadak, A. W., Murri, C., and Sage, E. H. (2004). Functional analysis of the matricellular protein SPARC with novel monoclonal antibodies. J. Histochem. Cytochem.52:723–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmayr, B., Keck, S., Henn, F. A., and Schloss, P. (2000). Acute stress decreases serotonin transporter mRNA in the raphe pontis but not in other raphe nuclei of the rat. Neurosci. Lett.290:109–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther, D. J., Peter, J. U., Bashammakh, S., Hortnagl, H., Voits, M., Fink, H., and Bader, M. (2003). Synthesis of serotonin by a second tryptophan hydroxylase isoform. Science299:76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiklund, L., and Björklund, A. (1980). Mechanisms of regrowth in the bulbospinal serotonin system following 5,6-dihydroxytryptamine induced axotomy. II. Fluorescence histochemical observations. Brain Res.191:109–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner, P., D’Aquila, P. S., Coventry, T., and Brain, P. (1995). Loss of social status: preliminary evaluation of a novel animal model of depression. J. Psychopharmacol.9:207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, M. L., O’Kirwan, F., Hannestad, J. P., Irizarry, K. J., Elashoff D., and Licinio, J. (2004). St John's wort and imipramine-induced gene expression profiles identify cellular functions relevant to antidepressant action and novel pharmacogenetic candidates for the phenotype of antidepressant treatment response. Mol. Psych.9:237–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T., and Bajjalieh, S. M. (2001). SV2 modulates the size of the readily releasable pool of secretory vesicles. Nat. Cell Biol.3:691–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Beaulieu, J. M., Sotnikova, T. D., Gainetdinov, R. R., and Caron, M. G. (2004). Tryptophan hydroxylase-2 controls brain serotonin synthesis. Science305:217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R. H., Kokame, K., Tsukamoto, Y., Yutani, C., Kato, H., and Miyata, T. (2001). Characterization of the human NDRG gene family: a newly identified member, NDRG4, is specifically expressed in brain and heart. Genomics73:86–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]