Abstract

1. Acetylation of morphine at the 6-position changes its pharmacology. To see if similar changes are seen with codeine, we examined the analgesic actions of codeine and 6-acetylcodeine.

2. Like codeine, 6-acetylcodeine is an effective analgesic systemically, supraspinally and spinally, with a potency approximately a third that of codeine.

3. The sensitivity of 6-acetylcodeine analgesia to the mu-selective antagonists β-FNA and naloxonazine confirmed its classification as a mu opioid. However, it differed from the other mu analgesics in other paradigms.

4. Antisense mapping revealed the sensitivity of 6-acetylcodeine to probes targeting exons 1 and 2 of the mu opioid receptor gene (Oprm), a profile distinct from either codeine or morphine. Although heroin analgesia also is sensitive to antisense targeting exons 1 and 2, heroin analgesia also is sensitive to the antagonist 3-O-methylnaltrexone, while 6-acetylcodeine analgesia is not.

5. Thus, 6-acetylcodeine is an effective mu opioid analgesic with a distinct pharmacological profile.

KEY WORDS: codeine, opioid, MOR-1, analgesia, 6-acetylcodeine, antisense, Mu opioid receptor, morphine, heroin

INTRODUCTION

Heroin remains one of the most widely abused drugs in the world. A derivative of morphine, heroin is rapidly de-acetylated in the blood to 6-acetylmorphine, its active agent. Heroin and 6-acetylmorphine are potent analgesics, sharing many other actions with those of morphine and other mu opioids. Like morphine, both heroin and 6-acetylmorphine depress respiration and inhibit gastrointestinal transit. However, a number of studies have revealed important differences between morphine and both heroin and 6-acetylmorphine. While morphine, heroin and 6-acetylmorphine analgesia are all reversed by mu-selective antagonists such as β-funaltrexamine and naloxonazine, 3-methylnaltrexone reverses heroin and 6-acetylmorphine analgesia at doses that are ineffective against morphine. CXBK mice have long been known to be insensitive to morphine (Baron et al., 1975; Reith et al., 1981; Pick et al., 1993). Yet, CXBK mice show normal analgesic sensitivity towards both heroin and 6-acetylmorphine (Rossi et al., 1996). Their actions also can be distinguished at the molecular level. Antisense mapping, in which different exons are targeted with antisense oligodeoxynucleotides, reveals different patterns between the drugs. Finally, disruption of exon 1 of the mu opioid receptor gene (Oprm) eliminates morphine actions, but heroin and 6-acetylmorphine retain analgesic activity in these mice, although at a slightly lower potency (Schuller et al., 1999). Thus, despite their similar classification as mu opioids, their pharmacology differs.

Structurally, codeine is a close analogue of morphine, differing only by the methylation of the 3-hydroxyl group. Pharmacologically, it also is very similar. Like morphine, codeine is a selective mu analgesic (Reisine and Pasternak, 1996). Its actions are selectively blocked by mu opioid antagonists and are markedly diminished in morphine-insensitive CXBK mice and it shows cross-tolerance with morphine (Rossi et al., 1996). The current study explores the pharmacological effects produced by acetylation of the 6-hydroxyl group of codeine.

METHODS

Codeine sulfate was purchased from Mallinckrodt (Saint Louis, MO). Morphine, 6-acetylcodeine and 6-acetylmorphine were obtained from the Research Technology Branch of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Naloxonazine was synthesized as described previously (Hahn and Pasternak, 1982). Halothane was produced from Halocarbon Lab (Hackensack, NJ).

Male Crl:CD-1 mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratory (Raleigh, NC). Knockout MOR-1 and DOR-1 mice were generated and backcrossed into C57/Bl6 mice for 10 generations (Schuller et al., 1999; Zhu et al., 1999). Mixed groups of homozygous male and female animals were used in the knockout studies. Drugs were administered either intracerebroventricularly (i.c.v.) (Haley and McCormick, 1957) or intrathecally (i.t.) (Hylden and Wilcox, 1980) under halothane anesthesia or subcutaneously (s.c.). Analgesia was assessed quantally as a doubling or greater of the baseline latency using a radiant heat tailflick assay (Rossi et al., 1996; Le Bars et al., 2001). Baseline latencies typically ranged between 1.5 and 3 s. A 10-s cutoff was imposed to minimize tissue damage. Group comparisons were performed by the Fisher exact test and ED50 and 95% confidence limits were calculated by the Litchfield–Wilcoxon method (Tallarida and Murray, 1987). Results using the quantal paradigm closely mimicked those seen using graded responses. All experimental protocols were approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and all procedures are in compliance with the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

MOR-1 antisense oligodeoxynucleotide sequences were based on the cloned mouse mu opioid receptor sequence (Rossi et al., 1995). The oligodeoxynucleotides were synthesized by Midland Certified Reagent Co. (Midland, TX, USA), purified in our laboratory and dissolved in 0.9% saline. The probe had the following sequences: exon 1: CGCCCCAGCCTCTTCCTCT; exon 2: TTGGTGGCAGTCTTCATTTTGG; and mismatch: CGCCCCGACCTCTTCC CTT. Mice received i.c.v. injections of antisense (5 μg in 2 μl) on days 1, 3 and 5 and tested on day 6, as previously described (Standifer et al., 1994; Rossi et al., 1996).

RESULTS

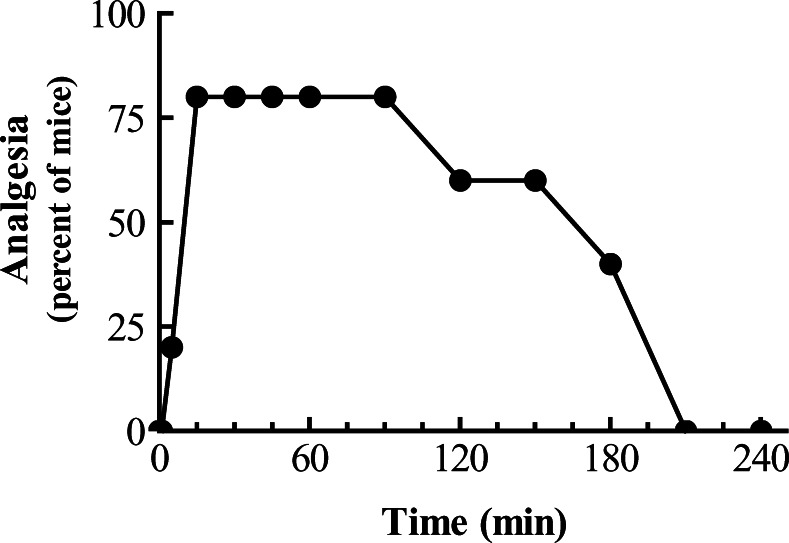

6-Acetylcodeine was an effective analgesic. Given subcutaneously, it quickly produced its maximal effect within 15 min and maintained it for over an hour (Fig. 1). Dose–response curves between codeine and 6-acetylcodeine revealed a threefold greater potency for codeine when the drugs are administered subcutaneously (Fig. 2a). Both agents also were active supraspinally (Fig. 2b) and spinally (Fig. 2c). As with systemic administration, codeine remained more potent than its 6-acetyl derivative.

Fig. 1.

Timecourse of 6-acetylcodeine analgesia. A group of mice (n=10) received 6-acetylcodeine (20 mg/ kg, s.c.) and analgesia was assessed at the indicated time.

Fig. 2.

Dose–response studies of 6-acetylcodeine and codeine analgesia. Groups of mice (n=20) received the indicated doses of 6-acetylcodeine or codeine (A) systemically, (B) supraspinally or (C) spinally and were assessed in the tailflick assay after 30, 15 or 15 min, respectively. Systemic ED50 values with 95% confidence limits for 6-acetylcodeine and codeine are 12.3 mg/kg (10.1, 15) and 3.91 mg/kg (3.02, 5.07), respectively. The supraspinal ED50 values with 95% confidence limits for 6-acetylcodeine and codeine are 3.53 μg (2.55, 4.90) and 0.86 μg (0.62, 1.19), respectively. Intrathecal ED50 values with 95% confidence limits for 6-acetylcodeine and codeine are 3.45 μg (2.44, 4.90) and 1.06 μg (0.69, 1.62), respectively.

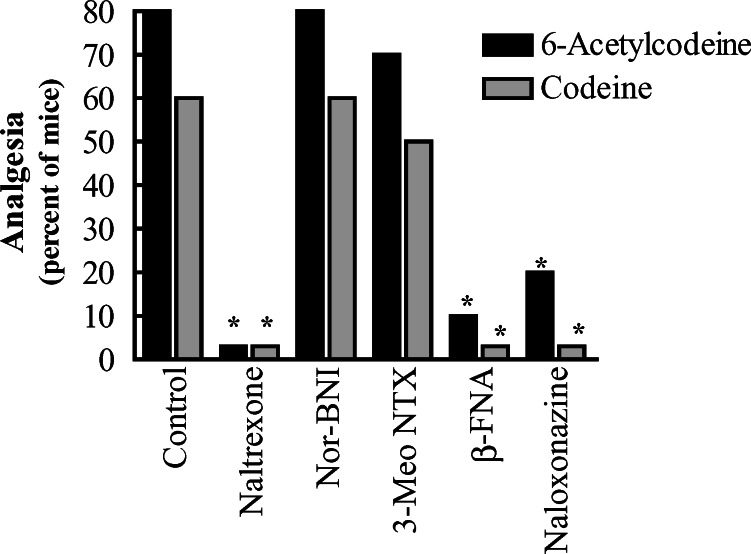

Both codeine and 6-acetylcodeine were effectively blocked by a number of mu-selective opioid antagonists (Fig. 3). The general opioid antagonist naltrexone blocked the actions of both agents, as did the mu-selective antagonist β-FNA and the mu1-selective antagonist naloxonazine. 3-O-Methylnaltrexone, which selectively blocks the analgesic actions of M6G, heroin and 6-acetylmorphine, had little effect on either codeine or 6-acetylcodeine. Neither the kappa1 antagonist norBNI, nor the delta antagonist naltrindole significantly reduced the actions of 6-acetylcodeine, but naltrindole did decrease the analgesic activity of codeine. To ensure that codeine was acting through mu receptors, we next examined codeine analgesia in both MOR-1 and a DOR-1 knockout mice (Fig. 4). Codeine was analgesic in the wildtype animals, although it showed a lower potency than in the CD-1 mice used earlier. The codeine dose–response in the DOR-1 knockout mice was indistinguishable from that in the wildtype, but the responses in the MOR-1 knockout animals were significantly reduced, consistent with a mu mechanism of codeine action.

Fig. 3.

Sensitivity of codeine and 6-acetylcodeine to antagonists. Groups of mice (n≥20) received codeine and 6-acetylcodeine and either saline, naltrexone, norBNI, 3-O-methylnaltrexone, β-FNA or naloxonazine. β-FNA and naloxonazine were administered 24 h prior to agonists. The others were given immediately prior to the agonists. Only naltexone, β-FNA and naloxonazine significantly reversed the analgesic actions of the drugs.

Fig. 4.

Codeine analgesia in opioid receptor knockout mice. Groups of mice with the indicated gene disruption were backcrossed to generation F10 into a C57/Bl6 background. A cumulative dose–response curve was carried out with codeine and analyzed quantally. Graded responses analysis give similar results.

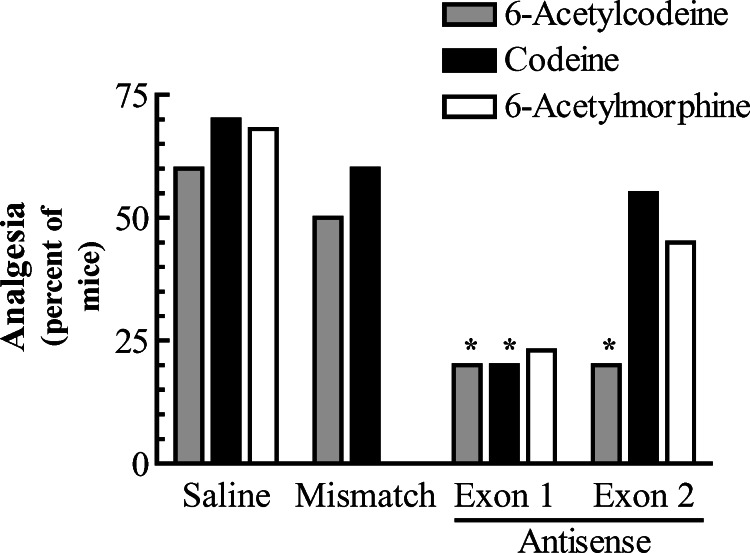

Antisense studies provide a sensitive method for exploring, at a molecular level, the receptor(s) mediating a behavior (Pasternak and Standifer, 1995; Rossi et al., 1995). In antisense mapping, antisense oligodeoxynucleotides are designed to target-specific exons within a gene and to downregulate mRNAs containing the targeted exon, providing a way to distinguish among splice variants of a single gene. Antisense probes targeting exons 1 and 2 revealed interesting differences between codeine and 6-acetylcodeine (Fig. 5). Codeine showed a pattern like morphine, with only the exon 1 antisense probe lowering the analgesic response. Prior studies from our laboratory have shown that morphine analgesia is unaffected by the exon 2 antisense probe. Similarly, this probe had little effect against codeine. 6-Acetycodeine, on the other hand, gave a response like heroin, in which both the exons 1 and 2 antisense oligodeoxynucleotides effectively decreased analgesia, distinguishing the actions of 6-acetylcodeine from those of either codeine or morphine.

Fig. 5.

Antisense mapping 6-acetylcodeine and codeine analgesia. Groups of mice (n≥20) received the indicated antisense (5 μg in 2 μl, i.c.v.) or saline on days 1, 3, 5 and were tested with either codeine (2 μg, i.c.v.) or 6-acetylcodeine (7.5 μg, i.c.v.) supraspinally on day 6 and analgesia was assessed 15 min post-injection. Antisense targeting exon 1 showed a reduction in analgesia for agents, while antisense targeting exon 2 showed a reduction in only for 6-acetylcodeine. Saline and mismatch treated mice showed no reduction in analgesic response.

Cross-tolerance is yet another way to assess common mechanisms of action. Following chronic morphine administration for 5 days, the ED50 value for morphine was significantly shifted over 1.5-fold (Table I). Similar shifts were observed with 6-acteylcodeine and for codeine.

Table I.

Analgesic Sensitivity to Opioids in Control and Morphine-Tolerant Mice

| ED50 (95% confidence limits) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Drug | Control | Morphine-tolerant |

| Codeine | 3.91 mg/kg (3.02, 5.07) | 12.2 mg/kg (8.07, 18.4) |

| 6-Acetylcodeine | 12.3 mg/kg (10.1, 15.0) | 19.5 mg/kg (16.4, 23.1) |

| Morphine | 3.29 mg/kg (1.99, 5.46) | 5.58 mg/kg (4.37, 7.12) |

Note. ED50 values with 95% confidence limits were determined from dose–response curves generated from groups of mice (n≥10) using at least three doses of each drug s.c. Control mice were naïve. Morphine-tolerant mice received a fixed dose of morphine (5 mg/kg, s.c.) daily for 4 days before performing the dose–response curve with the indicated drug on day 5.

DISCUSSION

Substitutions at the 6-position of morphine can change its pharmacology. Morphine-β-glucuronide (M6G) is an excellent example. Although glucuronidation at the 6-position does not appreciably change the receptor binding characteristics of the compound compared to morphine (Brown et al., 1997b), the pharmacology of the drug is altered (Table II). Despite a slightly lower affinity than morphine in mu receptor binding assays, its analgesic potency is 100-fold greater than morphine when given centrally to bypass the blood-brain barrier. It shows incomplete tolerance to morphine and retains its activity in CXBK mice that are unresponsive to systemic and supraspinal morphine (Rossi et al., 1996). Antisense mapping reveals different sensitivity profiles for morphine and M6G (Rossi et al., 1995, 1996) and M6G analgesia is retained in mice with a disruption of the first exon of the mu opioid receptor gene (Oprm) (Schuller et al., 1999). Acetylation of morphine at the 6-position also changes its pharmacology. Like M6G, 6-acetylmorphine, the active metabolite of heroin, retains its activity in CXBK mice and in the MOR-1 exon 1 knockout mice (Rossi et al., 1996). 6-Acetylmorphine also shows incomplete tolerance to morphine and is antagonized by 3-O-methylnaltrexone at doses inactive against morphine (Walker et al., 1999).

Table II.

Sensitivity of Opioids to Antisense Treatments Targeting Exons of Oprm

| Sensitivity of analgesia to treatment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOR-1 | Antisense | CXBK | 3-O-Methyl- | ||||

| Drug | β-FNA | Naloxonazine | KO | Exon 1 | Exon 2 | (i.c.v.) | naltrexone |

| Morphine | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| 6-Acetylmorphine | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| M6G | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Codeine | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| 6-Acetylcodeine | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | No |

| Heroin | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Note. (–) Not determined.

Codeine is structurally very similar to morphine, raising the question of whether or not acetylation of its 6-position produced pharmacological changes similar to those observed with 6-acetylmorphine. 6-Acetylcodeine was an effective analgesic with a potency approximately threefold lower than that of codeine, which contrasts with the similar analgesic potency of morphine and 6-acetylmorphine. It has been suggested that codeine may produce its actions after conversion to codeine-6-glucuronide (Vree et al., 2000), which is far more potent than codeine itself (G. Rossi and G. W. Pasternak, unpublished observations). Although codeine-6-glucuronide is generated in patients, opioid 6-glucuronidation does not occur in rodents. Thus, the greater potency of codeine to 6-acetylcodeine cannot be due to the conversion of codeine to its more potent 6-glucuronide.

The potency of codeine varied depending upon the strain of mouse being tested. While it was quite potent against CD-1 mice, its activity in C57/Bl6 wildtype mice was less. Clinically, codeine is far less active in patients than morphine (Payne and Pasternak, 1992a,b; Reisine and Pasternak, 1996), observations closer to those seen with the C57/Bl6 mice.

Pharmacologically, both codeine and 6-acetylcodeine are mu opioids, as shown by their sensitivity toward the mu-selective antagonists β-funaltrexamine and naloxonazine. Furthermore, they both demonstrate cross-tolerance to morphine. Antisense mapping also implicated the mu opioid receptor gene (Oprm) in the actions of both drugs. Yet, the overall pharmacological profile of 6-acetylcodeine analgesia differed from codeine, morphine and 6-acetylmorphine (Table II). Unlike M6G, heroin and 6-acetylmorphine, 6-acetylcodeine analgesia was not reversed by 3-O-methylnaltrexone (Brown et al., 1997a; Walker et al., 1999). Its antisense mapping profile also was distinct from the other drugs. Like morphine, 6-acetylcodeine analgesia was sensitive to the exon 1 antisense, but the ability of the exon 2 antisense to block 6-acetylcodeine clearly distinguished it from both morphine and codeine. The ability of both exons 1 and 2 antisense to block 6-acetylcodeine is similar to responses seen with heroin and fentanyl.

Overall, the drugs examined are all mu opioids and they share more similarities than differences, but the current studies reveal subtle pharmacological differences between 6-acetylcodeine and the other mu opioids. Clinically, the pharmacology of mu opioids is quite complex, with some patients responding better to one mu opioid than another (Payne and Pasternak, 1992a,b; Reisine and Pasternak, 1996). These subtle differences may reflect the presence of multiple mu receptor subtypes, as originally proposed 30 years ago (Pasternak and Snyder, 1975; Pasternak et al., 1980; Wolozin and Pasternak, 1981). Molecular studies have now identified at least two dozen splice variants of the mouse mu opioid receptor splice variants (Pan et al., 1999, 2000, 2001), seven rat variants (Zimprich et al., 1995; Pasternak et al., 2004) and at least 10 human variants (Bare et al., 1994; Pan et al., 2003, 2005). These variants, or others yet to be identified, may help explain the complex responses of mu analgesics and provides a focus for future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to GWP (DA00220, DA07241) and to JP (DA09040) and a core grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA08748).

REFERENCES

- Bare, L. A., Mansson, E., and Yang, D. (1994). Expression of two variants of the human μ opioid receptor mRNA in SK-N-SH cells and human brain. FEBS Lett.354:213–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron, A., Shuster, L., Elefterhiou, B. E., and Bailey, D. W. (1975). Opiate receptors in mice: Genetic differences. Life Sci.17:633–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G. P., Yang, K., King, M. A., Rossi, G. C., Leventhal, L., Chang, A., and Pasternak, G. W. (1997a). 3-Methoxynaltrexone, a selective heroin/morphine-6β-glucuronide antagonist. FEBS Lett.412:35–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G. P., Yang, K., Ouerfelli, O., Standifer, K. M., Byrd, D., and Pasternak, G. W. (1997b). 3H-Morphine-6β-glucuronide binding in brain membranes and in an MOR-1 transfected cell line. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.282:1291–1297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, E. F., and Pasternak, G. W. (1982). Naloxonazine, a potent, long-acting inhibitor of opiate binding sites. Life Sci.31:1385–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley, T. J., and McCormick, W. G. (1957). Pharmacological effects produced by intracerebral injections of drugs in the conscious mouse. Br. J. Pharmacol.12:12–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hylden, J. L. K., and Wilcox, G. L. (1980). Intrathecal morphine in mice: A new technique. Eur. J. Pharmacol.67:313–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bars, D., Gozariu, M., and Cadden, S. W. (2001). Animal models of nociception. Pharmacol. Rev.53:597–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, L., Xu, J., Yu, R., Xu, M., Pan, Y. X., and Pasternak, G. W. (2005). Identification and characterization of six new alternatively spliced variants of the human mu opioid receptor gene, Oprm. Neuroscience133:209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y. X., Xu, J., Bolan, E., Chang, A., Mahurter, L., Rossi, G., and Pasternak, G. W. (2000). Isolation and expression of a novel alternatively spliced mu opioid receptor isoform, MOR-1F. FEBS Lett.466:337–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y. X., Xu, J., Bolan, E. A., Abbadie, C., Chang, A., Zuckerman, A., Rossi, G. C., and Pasternak, G. W. (1999). Identification and characterization of three new alternatively spliced mu opioid receptor isoforms. Mol. Pharmacol.56:396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y. X., Xu, J., Mahurter, L., Xu, M. M., Gilbert, A.-K., and Pasternak, G. W. (2003). Identification and characterization of two new human mu opioid receptor splice variants, hMOR-1O and hMOR-1X. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.301:1057–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.-X., Xu, J., Mahurter, L., Bolan, E. A., Xu, M. M., and Pasternak, G. W. (2001). Generation of the mu opioid receptor (MOR-1) protein by three new splice variants of the Oprm gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.98:14084–14089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak, D. A., Pan, L., Xu, J., Yu, R., Xu, M., Pasternak, G. W., and Pan, Y.-X. (2004). Identification of three new alternatively spliced variants of the rat mu opioid receptor gene: Dissociation of affinity and efficacy. J. Neurochem.91:881–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak, G. W., Childers, S. R., and Snyder, S. H. (1980). Opiate analgesia: Evidence for mediation by a subpopulation of opiate receptors. Science208:514–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak, G. W., and Snyder, S. H. (1975). Identification of a novel high affinity opiate receptor binding in rat brain. Nature253:563–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak, G. W., and Standifer, K. M. (1995). Mapping of opioid receptors using antisense oligodeoxynucleotides: Correlating their molecular biology and pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol. Sci.16:344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne, R., and Pasternak, G. W. (1992a). Pain. In Johnston, M. V., Macdonald, R. L., and Young, A. B. (eds.), Principles of Drug Therapy in Neurology. Davis, Philadelphia, FA, pp. 268–301. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, R., and Pasternak, G. W. (1992b) Pharmacology of pain treatment. In Johnston M. V., MacDonald R., and Young A. B. (eds.), Contemporay Neurolog Series: Scientific Basis of Neurologic Drug Therapy. Davis, Philadelphia, pp 268–301. [Google Scholar]

- Pick, C. G., Nejat, R., and Pasternak, G. W. (1993). Independent expression of two pharmacologically distinct supraspinal mu analgesic systems in genetically different mouse strains. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.2265:166–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisine, T., and Pasternak, G. W. (1996) Opioid analgesics and antagonists. In Hardman J. G., and Limbird L. E. (eds.), Goodman & Gilman’s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. McGraw-Hill, pp. 521–556.

- Reith, M. E. A., Sershen, H., Vadasz, C., and Lajtha, A. (1981). Strain differences in opiate receptors in mouse brain. Eur. J. Pharmacol.74:377–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, G. C., Brown, G. P., Leventhal, L., Yang, K., and Pasternak, G. W. (1996). Novel receptor mechanisms for heroin and morphine-6β -glucuronide analgesia. Neurosci. Lett.216:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, G. C., Pan, Y.-X., Brown, G. P., and Pasternak, G. W. (1995). Antisense mapping the MOR-1 opioid receptor: Evidence for alternative splicing and a novel morphine-6β-glucuronide receptor. FEBS Lett.369:192–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuller, A. G., King, M. A., Zhang, J., Bolan, E., Pan, Y. X., Morgan, D. J., Chang, A., Czick, M. E., Unterwald, E. M., Pasternak, G. W., and Pintar, J. E. (1999). Retention of heroin and morphine-6 beta-glucuronide analgesia in a new line of mice lacking exon 1 of MOR-1. Nat. Neurosci.2:151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standifer, K. M., Chien C.-C., Wahlestedt, C., Brown, G. P., and Pasternak, G. W. (1994). Selective loss of δ opioid analgesia and binding by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides to a δ opioid receptor. Neuron12:805–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida, R. J., and Murray, R. B. (1987) Manual of Pharmacological Calculations with Computer Programs. Springer-Verlag, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Vree, T. B., van Dongen, R. T., and Koopman-Kimenai, P. M. (2000). Codeine analgesia is due to codeine-6-glucuronide, not morphine [In Process Citation]. Int. J. Clin. Pract.54:395–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, J. R., King, M., Izzo, E., Koob, G. F., and Pasternak, G. W. (1999). Antagonism of heroin and morphine self-administration in rats by the morphine-6β-glucuronide antagonist 3-O-methylnaltrexone. Eur. J. Pharmacol.383:115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolozin, B. L., and Pasternak, G. W. (1981). Classification of multiple morphine and enkephalin binding sites in the central nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA78:6181–6185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. X., King, M. A., Schuller, A. G. P., Nitsche, J. F., Reidl, M., Elde, R. P., Unterwald, E., Pasternak, G. W., and Pintar, J. E. (1999). Retention of supraspinal delta-like analgesia and loss of morphine tolerance in δ opioid receptor knockout mice. Neuron24:243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimprich, A., Simon, T., and Hollt, V. (1995). Cloning and expression of an isoform of the rat μ opioid receptor (rMOR 1 B) which differs in agonist induced desensitization from rMOR1. FEBS Lett.359:142–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]