Abstract

1. Phosphatidylinositol transfer proteins (PI-TP) are responsible for the transport of phosphatidylinositol (PI) and other phospholipids from endoplasmic reticulum to the other membranes and indirectly for lipid mediated signaling. Till now little is known about PI-TPs in brain aging and neurodegeneration. The aim of this study was to investigate expression of PI-TP in the brain during aging and in animal's model of Parkinson disease (PD) induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP). Moreover, in vitro, effect of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridine cation (MPP+) on PI-TP, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) protein level, and viability of cells was investigated.

2. Wistar rats 4, 24, and 36 months old and C57/BL mice and rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cell line were used for the studies. Mice C57/BL received three injections of MPTP in saline at 2 h intervals in a total dose of 40 mg/kg and then after 3, 7, and 14 days they were used for the investigation. PC12 cells were treated with increasing concentration (50–300 μM) of MPP+ for 24 h at 37°C. The level of PI-TPα and β and TH were determined using Western Blot analysis.

3. Our data indicated that PI-TPα and β level decreased in brain of 36 months old rat by 20% comparing to the control value (4 months old). In animal's model of PD, PI-TPα and β level was significantly lower by 85, 69, 64% in striatum at 3, 7, and 14 days after MPTP injection, respectively, compared to the control value. MPP+ decreased PI-TPα and β, TH expression, and viability of PC12 cells in a dose-dependent manner. H2O2, menadione, and NO donor significantly decreased the PI-TP level and viability of PC12 cells.

4. Our results indicate the lower protein expression of PI-TPα and β in aged brain and in PD and suggest that oxidative stress may be responsible for the alteration of PI-TP.

KEY WORDS: Phosphatidylinositol transfer protein, Aging, Parkinson disease, Neurodegeneration, Oxidative stress

INTRODUCTION

Phosphatidylinositol (PI) transfer protein (PI-TP) is a small ubiquitously expressed and abundant protein that transfers PI and phosphatidylcholine (PC) between membranes (Wirtz, 1991, 1997; Geijtenbeerk et al., 1994). Recent studies have shown that the cellular functions of PI-TP are not only connected with phospholipid transfer per se from its site of synthesis in the endoplasmic reticulum to the other membranes but also with other important cell functions as vesicle transport, dynamics of cytoskeleton proteins, and PI metabolism (Thomas et al., 1993b; Liscovitch and Cantley, 1995; Monaco et al., 1998; Snoek et al., 1999). PI-TP is an essential for agonist stimulated synthesis of polyphosphoinositide (Thomas et al., 1993b; Kauffmann-Zeh et al., 1995; Kearns et al., 1998). The high affinity of PI-TP for PIP and PIP2 impose that these lipids remain bound to PI-TP after their formation. The PI-TP may also deliver these lipids as a substrates for phospholipase C (PLC) and phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (Thomas et al., 1993b; Kauffmann-Zeh et al., 1995; Snoek et al., 1999). A remarkable evidence indicates that membrane traffic events are connected with the activity of PI3′-kinase and with the formation of different class of lipids as phosphatidylinositol (3) phosphate PI(3)P, PI(3,4)P2, and PI(3,4)P3 (Kular et al., 1997; Panaretou et al., 1997). These lipids are not substrates for PLC but they are very active intracellular messenger molecules.

Polyphosphoinositide containing phosphate in D3 position influences the proteins that regulate vesicle formation and perhaps also their docking and fusion. Hay (1995) has suggested that PI-TPs promote assembly of the actin by cytoskeletal PIP2 -binding proteins.

One of the major factors, which can influence the membrane fluidity is phospholipid composition of membrane. Oxidative stress increases lipid peroxidation and also decreases the membrane fluidity (Yehuda et al., 2002). Diminishing of membrane fluidity was observed with aging (Joseph et al., 1998). Previous studies indicate that phosphoinositide metabolism decreases in aged brain and in PD (Bothmer et al., 1992; Klerenyi et al., 1998; Zambrzycka, 2004). It was shown that total polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) level was decreased in the aged brain and may contribute to cell damage by increasing PUFA oxidation and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Kukreja et al., 1986).

According to the free radicals hypothesis of aging the generation and accumulation of reactive oxygen species result in oxidative damage molecules, which is coupled with insufficient antioxidant defense mechanism (Harman, 1992; Ames et al., 1993). Free radicals may also disturb phosphoinositides metabolism, transport, and signaling. It was shown previously by Hamilton et al. (1997) that the vibrator mutation caused neurodegeneration-induced significant reduction of PI-TP mRNA and protein level. Till now little is known about the PI-TPs in brain aging and Parkinson disease.

The aim of this study was to investigate expression of PI-TPα and β in the brain during aging and in animal's model of Parkinson disease (PD) induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP). Moreover, using PC 12 cells in culture we have investigated the effect of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridine cation (MPP+) on PI-TPα and β expression.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Materials

Rabbit polyclonal anti-TH antibody (Biocom International, Temecula, CA, USA), rabbit polyclonal anti-β-actin antibody, goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (AR-HRP), and goat anti-rabbit conjugated with AP antibody were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Nitrocellulose membrane was obtained from Bio-Rad (Wien, Austria). ECL kit was obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Protease inhibitors were from Boehringer-Mannheim (Mannheim, Germany). 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), and the remaining reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Animals

4, 18, and 36 months old male Wistar rats (200–250 g) and 8-week-old C57/bl mice (20–25 g) were supplied from the Animal Breeding House of Medical Research Center, Polish Academy of Sciences (Warsaw, Poland). Animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle with free access to food and water.

MPTP Treatment

Mice were housed in a temperature-controlled room under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle with free access to food and water. On the day of the experiment, mice C57/BL received intraperitioneally (i.p.) three injections of MPTP in saline at 2 h intervals in a total dose 40 mg/kg. Control mice obtained saline only. Mice were sacrificed at 3, 7, and 14 days after MPTP treatment. Different parts of brain as striatum, midbrain, hippocampus, and brain cortex were quickly dissected on an ice-cold glass Petri dish. Samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C till analyzed.

PC12 Cell Culture

Pheochromocytoma cells line (PC 12 cells) were cultured in 75 cm2 flasks in DMEM supplemented with 10%-heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 5% heat-inactivated horse serum (HS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL), 2 mM glutamine. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Cells were subcultured about once a week. For experiments, confluent cells were subcultured into polyethylenimine-coated 60 mm2 dishes or 24-well plates. Cells were used for experiments 1 day after plated in 24-well plate or 75–90% confluence for determination of PI-TP protein level. Prior to treatment, cells were replenished with DMEM medium containing 2% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL), 2 mM glutamine.

PC12 Cells Treatment

PC12 cells were treated with MPP+ (50–300 μM), H2O2 (500 μM), menodione (100 μM) or NO donor, sodium nitroprusside (500 μM) for 24 h at 37°C. Then after washing with cold phosphate saline buffer (PBS), cells were lysed in boiling buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 1% SDS and protease inhibitors (1 tab/10 mL buffer, Boehringer-Mannheim GmbH, Germany). After sonification, the protein content was determined by the Lowry method (Lowry et al., 1951).

Preparation of Homogenate

The rats were sacrificed and brain hemispheres or the other parts of brain were quickly dissected on an ice-cold glass Petri dish. The brain cortex, hippocampus, striatum, and cerebellum were homogenized in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.4 containing 0.25 M sucrose, 1mM EDTA and protease inhibitors (1 tab/10 mL buffer, Boehringer-Manheim GmbH, Germany) in a Dounce homogenizer by 14 strokes. The protein content of homogenate was determined by the Lowry method (Lowry et al., 1951).

Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blotting for PI-TP and Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH)

Homogenate aliquots (40 μg protein) and an aliquot of purification PI-TP protein (2 μg/mL, positive control) were mixed with an equal volume of sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 100 mM DTT, 10% glycerol and 0.025% bromophenol blue; Laemmli, 1970). The samples were boiled for 5 min at 95°C. The proteins were analyzed by electrophoresis on 10% polyacrylamide gel SDS-PAGE (Laemmli, 1970). Then proteins were electrophoretically transferred from the SDS polyacrylamide gel at 1 mA/cm2 for 75 min at room temperature to nitrocellulose membranes. The membrane was blocked in 5% Milk Powder (nonfat dry-milk) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.05% Tween20 (TBS-T) for 1 h at 37 °C. Then the blot was incubated with anti-PI-TPαβ antibody (raised aganist synthetic peptides, diluted 1:100) in TBS-T containing 0.2% (w/v) nonfat milk) or anti-TH antibody (diluted 1:1000 in TBS-T), anti-β-actin (diluted 1:400 in TBS-T) overnight at room temperature. The PI-TP antibody complex was identified with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (GAR-AP, 1:5000 diluted in TBS-T containing 0.2% w/v nonfat milk). The TH and β-actin antibodies complex were identified with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugate with horseradish peroxidase (GAR-HR, diluted 1:8000). The GAR-AP was visualized with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoylphosphate p-toluidine salt and p-nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (BCIP/NBT) as color development substrate for alkaline phosphatase. The GAR-HR was visualized with ECL kit and Hyperfilm-Kodak (Sigma, MO, USA). The optical densities of the PI-TP and TH bands on the immunoblot were quantified using a NucleoVision apparatus and the GelExpert 4.0 software.

Assessment of Cell Viability

Cell viability was determined by MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) conversion. This assay takes advantage of the conversion of the yellow MTT to purple formazan crystals by mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase in viable cells.

The cells were treated with MPP+ or H2O2, menadione, NO donors for 24 h as described earlier and in legend to Figures. After the cell treatment, the culture medium was removed and replaced with MTT solution at the final concentration of 0.25 mg/mL in DMEM medium and incubated for 2 h to allow the conversion of MTT into formazan crystals in a 5% CO2 humidified chamber. Then the MTT solution was removed from cells and cells were lysed with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and absorbance was read at 595 nm on a 96-well plate using ELISA Bio-Rad Microplate Reader (Wien, Austria). The results were expressed as percentage of control.

Statistical Analysis

The results were expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences among means were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls posthoc test when appropriate. p<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

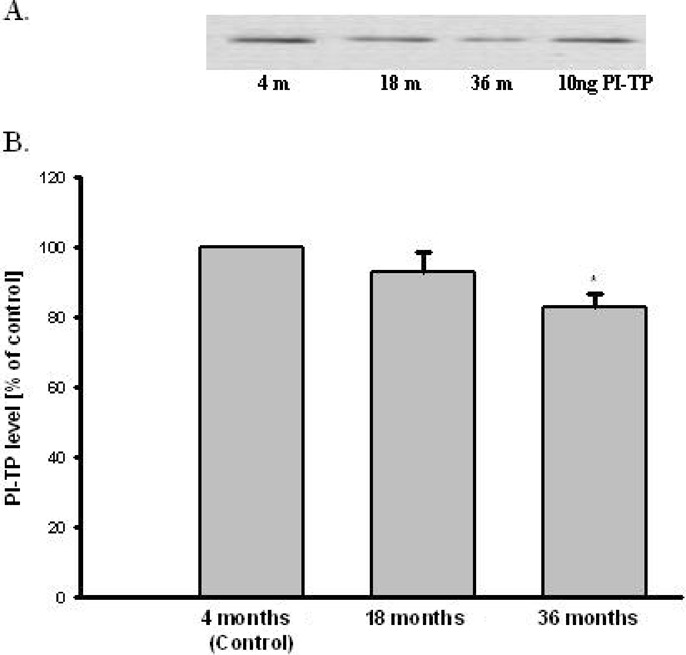

The level of PI-TPα and β and TH were determinated using immunochemistry method (Western Blot analysis). Purified PI-TP protein level was used as a standard for calculation of amount of PI-TP in samples. Densitometric analysis indicated that PI-TPα and β level is similar in all investigated brain parts: the hippocampus, brain cortex, striatum, and cerebellum of adult rats (Fig. 1). PI-TPα and β protein level decreased by 20% in aged brain of 36 months old rats compared to the adults (4 months old rats, control). PI-TP protein level did not change in brain of 18 months old rats (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

PI-TP level in the brain cortex, hippocampus, striatum midbrain, and cerebellum. Results are the mean values ± SEM of seven separate experiments and are expressed as ng/mg protein

Fig. 2.

The effect of aging on PI-TP level in brain rats. (A) Western Blot analysis of PI-TP and actin. The photographic inserts show typical results of Western Blot product analyses. Lanes: 4m—brain of 4 months old rat (control), 18m—brain of 18 months old rat (old), 36m—brain of 36 months old rat, PI-TP—10 ng purification of PI-TP protein as positive control. (B) Densitometric analysis results are the mean values ± SEM of four separate experiments and are expressed as the percentage of the respective control. * p<0.05 versus the control (one-way ANOVA followed by the Student–Newman–Keuls test)

In animal's model of PD, the PI-TPα and β level was significantly lower in striatum 3, 7, and 14 days after MPTP injection and decreased by 85, 69, 64%, respectively compared to the control value (nontreated mice) (Fig. 3). MPTP administration caused about 40, 45, and 55% decrease in the dopaminergic fibers in striatum at 3, 7, 14 days after the treatment, respectively (Chalimoniuk et al., 2004a).

Fig. 3.

Effect of MPTP on PI-TP level in striatum at 3, 7, and 14 days after treatment. (A) Western Blot analysis of striatum PITP. The photographic inserts show typical results of Western Blot product analyses. Lanes: C—control, 3—3 days, 7—7 days, and 14—14 days after MPTP injection, PI-TP—10 ng purification of PI-TP as positive control. (B) PI-TP level in striatum after MPTP treatment. The results are the mean values ± SEM of five separate experiments and are expressed as the percentage of the respective control. * p<0.005, **<0.001 versus the control (one-way ANOVA followed by the Student–Newman–Keuls test)

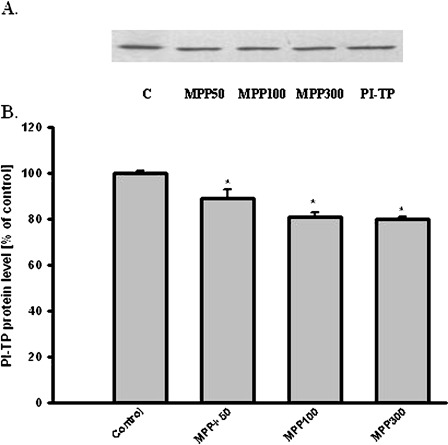

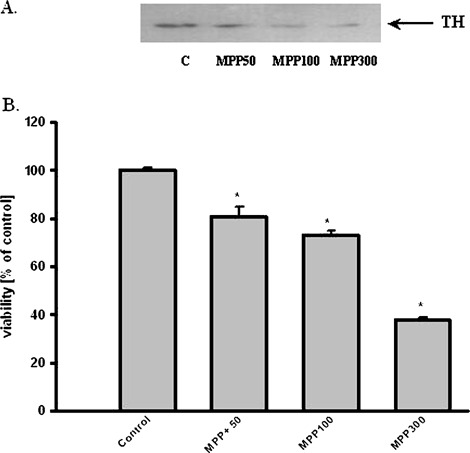

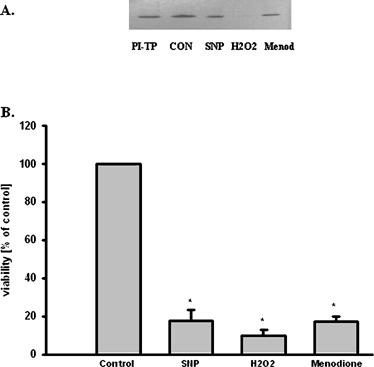

MPTP is metabolized by monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) to MPP+, which is transported into dopaminergic neurons by dopamine transporter (DAT) and induced many biochemical changes. In vitro studies indicated that dose-dependent MPP+ altered PI-TPα and β protein level in PC12 cells (Fig. 4). However, dose- dependent MPP+ decreased PC12 cells viability and TH protein level in PC12 cells (Fig. 5). Compounds inducing peroxidation, such as H2O2, menadione, and NO donor, which decreased PC12 cells viability of about 80%, caused significant reduction of the PI-TPα and β protein concentration in PC12 cells (Fig. 6).

Fig. 4.

Effect of MPP+ on PI-TP level in PC12 cells. (A) Western Blot analysis of PI-TP immunoreactivity. The photographic inserts show typical results of Western Blot product analyses. Lanes: C—control, MPP50-MPP+ 50 μM, MPP100–MPP+ 100 μM, MPP300–MPP+ 300 μM, PI-TP- 10 ng purification of PI-TP as a positive control. (B) Densitometric analysis results are the mean values ± SEM of four separate experiments and are expressed as the percentage of the respective control. * p<0.001 versus the control (one-way ANOVA followed by the Student–Newman–Keuls test)

Fig. 5.

Effect of MPP+ on TH protein level and viability in PC12 cells. (A) Western Blot analysis of TH protein level. The photographic inserts show typical results of Western Blot product analyses. Lanes: C—control, MPP50—MPP+ 50 μM, MPP100—MPP+ 100 μM, MPP300—MPP+ 300 μM. (B) PC12 cells viability results are the mean values ± SEM of four separate experiments and are expressed as the percentage of the respective control. * p<0.001 versus the control (one-way ANOVA followed by the Student–Newman–Keuls test)

Fig. 6.

Effect of prooxidative compounds on PI-TP protein level and PC12 cells viability. (A) Western Blot analysis of PI-TP protein level. The photographic inserts show typical results of Western Blot product analyses. Lanes: C—control, SNP—SNP 500 μM, H2O2—H2O2 500 μM, Menod—menodione 100 μM. PI-TP—10 ng purification of PI-TP as positive control. (B) PC12 cells viability results are the mean values ± SEM of four separate experiments and are expressed as the percentage of the respective control. * p<0.001 versus the control (one-way ANOVA followed by the Student–Newman–Keuls test)

DISCUSSION

These studies indicated that PI-TPα and β protein level decreased significantly in aged brain of 36 months old rats and in striatum of mice in PD model. Our in vitro study indicated that free radicals are involved in significant reduction of PI-TPα and β protein level and suggested that they may be responsible for PI-TPα and β alteration in aged brain and in mice model of Parkinson disease. The lower concentration of PI-TPα and β in aged brain and in mice model of PD may disturb phosphoinositidies signaling and membrane fluidity.

Previous studies indicate that phosphoinositide metabolisms decrease in aged brain and in PD (Bothmer et al., 1992; Klerenyi et al., 1998; Tariq et al., 2001; Zambrzycka, 2004). The activation of enzymes, which hydrolyzed phospholipids (PLA2, PLC) and released free arachidonic acid (AA) were enhanced in aged brain and PD (Klerenyi et al., 1998; Tariq et al., 2001). Additionally, it was shown that total polyunsaturated fatty acids level was decreased in the aged brain as a consequence of free radicals dependent oxidation (Yehuda et al., 2002). It is known, that free radicals (oxidative stress) have been implicated in mechanism leading to neuronal cells injury in various pathological states of the brain as Parkinson, Alzheimer diseases (Zhang et al., 2000; Calabrese et al., 2003; Barja, 2004).

Our studies indicated that PI-TP protein level was decreased in aged brain and in striatum of MPTP-induced Parkinsonism. Our in vitro study indicated that MPP+ decreased PI-TP and TH protein levels and viability in PC12 cells. These results suggest that transfer of PI and other lipids from the site of synthesis to the intracellular and plasma membranes is diminished. Simultaneously increased phospholipids hydrolysis by PLA2 in the brain aging and PD was observed. In consequence the phospholipids composition of membrane may undergo modification in aged and PD brains. Phospholipids composition of membrane influence membrane fluidity and phospholipids signaling. A lowering of membrane fluidity was observed with aging (Joseph et al., 1998). Yehuda et al. (2002) have shown that oxidative stress, which leads to an increase of free radicals increases lipid peroxidation and decreases the membrane fluidity (Yehuda et al., 2002). Enhanced free AA level by excessive activation of PLA2 induced modification of membrane fluidity (Katsuki and Okuda, 1995), and it may exert several neurotoxic effects (Toborek et al., 1999; Garrido et al., 2001). In addition, arachidonic acid is a very potent messenger involved in synaptic transmission, and in a variety of signal transduction pathways (Katsuki and Okuda, 1995).

Studies performed on patients with PD and on animal model of PD have demonstrated an increase in oxidative stress in substantia nigra including lipid peroxidation, production of free radicals (Dexter et al., 1989; Przedborski et al., 1996; Jenner, 1998; Chalimoniuk et al., 2004b), and decreased glutathione concentration (Sian et al., 1994; Beal, 1995; Beal et al., 1998; Bharath et al., 2002).

Our in vitro study indicated that free radicals induced the decrease of PI-TP protein level in PC12 treated with peroxidant compounds as H2O2, menodione, NO donor, and decreased PC12 cells viability. The free radicals may be involved in PI-TP alteration in brain aging and PD.

The role of PI-TP in physiology and pathology of the central nervous system (CNS) is still not clear. These proteins are involved in phospholipids degradation, phospholipids transport, as well as in dynamic cytoskeleton changes and in function of Golgi system (Wirtz, 1991, 1997; Snoek et al., 1999). It seems that the decrease of PI-TP protein level may be one of the important factors that lead to disturbing of phospholipids signaling and also may be involved in neurodegeneration of CNS. Alb et al. (2002, 2003) indicated that lack of PI-TPα caused aponecrotic spinocerebrallar disease in PI-TPα knockout mice. The mice lacking PI-TPα die soon after birth (Alb et al., 2002). The vibrator mutation caused an early-onset progressive action tremor, degeneration of brain stem and spinal cord neurons, and juvenile death. PI-TP mRNA and protein level were decreased five times in vibrator mutation (Hamilton et al., 1997).

On the other hand, the increase of PI-TP level may prevent neurodegeneration. PI-TP plays a role in delivery PI to PI4-kinase, which synthesize PI 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), these lipids remain bound to PI-TP, which may also deliver these substance for PLC (Thomas et al., 1993a). The activation of PLC-pathway leads to elevated level of diacylogicerol (DAG). In the next steps DAG activates PKC, which, via phosphorylation initiates MAP kinase cascade. Jiang et al. (2002) showed that MAPK/ERK1/2 signaling was involved in protection of cultured cerebral cortical astrocytes against ischemic injury. It has been shown that ERK2 caused an increase in bcl-2 expression and inhibition cellular apoptosis. The elevated expression of PI-TPα was also observed in astrocytes subjected to ischemia in vitro after treatment with aniracetam (1-anisoyl-2-pyrrolidinone), a modulator of ionotropic α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole (AMPA) and metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptors (Gabryel et al., 2005). Aniracetam could affect PI-TP, that activation of these proteins was involved in escalation of MAP kinase cascade and prevented ischemia-induced apoptosis of astrocyte cells (Gabryel et al., 2004, 2005).

In summary, our results suggest that oxidative stress may be responsible for the decrease of PI-TPα and β level in aged brain and in PD that may disturb phosphoinositides transport, metabolism and influence cytoskeleton dynamic and function. In consequence this decrease may lead to neurodegeneration and death of neurons in aged brain and PD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by RSC grant 3P05A13622, and PBZ-MIN001/P05/16.

Abbreviations used:

- AMPA

ionotropic α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic

- ECL

enhanced chemiluminescence

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HS

horse serum

- mGlu

metabotropic glutamate (mGlu)MPP+, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridine cation

- MPTP

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

- MTT

3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- PD

Parkinson disease

- PC12 cells

pheochromocytoma cell line

- PBS

phosphate saline buffer

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PI

Phosphatidylinositol

- PI-TP

phosphatidylinositol transfer proteins

- PLA2

phospholipase A2

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acids

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase.

REFERENCES

- Alb, J. G. Jr., Cortese, J. D., Philips, S. E., Albin, R. L., Nagy, T. R., Hamilton, B. A., and Bankaitis, V. A. (2003). Mice lacking phosphotidylinositol transfer protein-alpha exhibit spinocereberallar degeneration, intestinal and hepatic steatosis, and hypoglycemia. J. Biol. Chem.29:33501–33518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alb, J. G. Jr., Philips, S. E., Rostand, K., Cui, X., Pinxteren, J., Cotlin, L., Manning, T., et al. (2002). Genetic ablation of Phosphatidylinositol transfer protein function in murine embryonic stem cells. Mol. Biol. Cell13:739–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames, B. N., Shigenaga, M. K., and Hagen, T. M. (1993). Oxidants antioxidants and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.90:7915–7922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barja, G. (2004). Free radicals and aging. Trends Neurosci.27(10):595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal, M. F. (1995). Aging, energy and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Ann. Neurol.38:357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal, M. F., Matthews, R. T., Tieleman, A., and Shults, C. W. (1998). Coenzyme Q10 attenuates the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) induced loss of striatal dopamine and dopaminergic axons in aged mice. Brain Res.783:109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharath, S., Hsu, M., Kaur, D., Rajagopalan, S., and Andersen, J. K. (2002). Glutathione, iron and Parkinson's disease. Biochem. Pharmacol.64:1037–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boje, K. M. (2004). Nitric oxide neurotoxicity in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Biosci.9:763–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bothmer, J., Mommers, M., Markerink, M., and Jolles, J. (1992). The effect of age on phosphatidylinositol kinase, phosphatidiyliositol phosphate kinase and diacylglycerol kinase activities in rat brain cortex. Growth Dev. Aging58:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, V., Scapaginini, G., Colombrita, C., Ravagna, A., Pennisi, G., Giuffrida, Stella, A. M., Galli, F., and Butterfield, D. A., (2003). Redox regulation of heat shock protein expression in aging and neurodegenerative disorders associated with oxidative stress: A nutritional approach. Amino Acids25:435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalimoniuk, M., Langfort, J., Lukacova, N., and Marsala, J. (2004a). Upregulation of guanylyl cyclase expression and activity in striatum of MTPT-induced Parkinsonism in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.324:118–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalimoniuk, M., Stepien, A., and Strosznajder, J. B. (2004b). Pergolide mesilate, dopaminergic receptor agonist, applied with L-DOPA enhances serum antioxidant enzymes activity in Parkinson Disease. Clin. Neuropharmacol.27:223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter, D. T., Carter, C. J., and Wells, F. R. (1989). Basal lipid peroxidation in substantia nigra is increased in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurochem.52:381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabryel, B., Chalimoniuk, M., Małecki, A., and Strosznajder, J. (2005). Effect of aniracetam on phosphatidylinositol transfer protein alpha in cytosolic and plasma membrane fractions of astrocytes subjected to simulated ischemia in vitro. Pharmacol. Rep.57:664–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabryel, B., Pudełko, A., and Małecki, A. (2004). Erk1/2 and Akt kinases are involved in the protective effect of aniracetam in astrocytes subjected to stimulated ischemia in vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol.494:111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, R., Mattson, M. P., Hennig, B., and Toborek, M. (2001). Nicotine protects against arachidonic-acid-induced caspase activation, cytochrome c release and apoptosis of cultured spinal cord neurons. J. Neurochem.76:1395–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geijtenbeek, T. B., de Groot, E., van Baal, J., Brunink, F., Westerman, J., Snoek, G. T., and Wirtz, K. W. (1994). Characterization of mouse phosphatidylinositol transfer protein expressed in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1213:309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, B. A., Smith, D. J., Kerrebrock, A. W., Bronson, R. T., van Berkel, V., Daly, M. J., Kruglyak, L., Reeve, M. P., Nemhauser, J. L., Hawkins, T. L., Rubin, E. M., and Lander, E. S. (1997). The vibrator mutation causes neurodegeneration via reduced expression of PI-TP alpha: Positional complementation cloning and extragenic suppression. Neuron18:711–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman, D. (1992). Role of free radicals in aging and disease. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci.673:126–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay, J. E. (1995). Bone disease after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. Surg.1:55–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner, P. (1998). Oxidative mechanisms in nigral cell death in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord.13(Suppl. 1):24–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner, P., and Olanow, C. W. (1996). Pathological evidence for oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease and related degenerative disorders. In Olanow, C. W., Jenner, P., and Youdim, M. (eds.), Neurodegeneration and Neuroprotection in Parkinson's Disease, London Academic, London, pp. 24–45. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z., Zuang, Y., Chem, X., Lam, P. Y., Yang, H., Xu, Q., and Yu, A. C. H. (2002). Activation of ERK1/2 in astrocytes under ischemia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.294:726–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, J. A., Denisova, N. A., Fisher, D., Bickford, P., and Cao, G. (1998). Age-related neurodegeneration and oxidative stress: Putative nutritional intervention. Neurol. Clin.16:747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuki, H., and Okuda, S. (1995). Arachidonic acid as a neurotoxic and neurotrophic substance. Prog. Neurobiol.46:607–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffmann-Zeh, A., Thomas, G. M., Ball, A., Prosser, S., Cunningham, E., Cockcroft, S., and Hsuan, J. J. (1995). Requirement for phosphatidylinositol transfer protein in epidermal growth factor signalling. Science268:1188–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns, B. G., Alb, J. G. Jr., and Bankaitis, V. (1998). Phosphatidylinositol transfer proteins: The long and winding road to physiological function. Trends Cell Biol.8:276–282Author: Please check the page range in Kearns et al. (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klerenyi, P., Beal, M. F., Ferrante, R. J., Andreassen, O. A., Wermer, M., Chin, M. R., and Bonventre, J. V. (1998). Mice deficient in group IV cytosolic phospholipase A2 are resistant to MPTP neurotoxicity. J. Neurochem.71:2634–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukreja, R. C., Kontos, H. A., Hess, M. L., and Ellis, E. F., (1986). PGH synthase and lipooxygenase generate superoxide in the presence of NADH or NADPH. Circ. Res.59:612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kular, G., Loubtchenkov, M., Swigart, P., Whatmore, J., Ball, A., Cockcroft, S., and Wetzker, R. (1997). Co-operation of phosphatidylinositol transfer protein with phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma in the formylmethionyl-leucylphenylalanine-dependent production of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate in human neutrophils. Biochem. J.325:299–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli, U. K. (1970). Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature227:680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liscovitch, M., and Cantley, L. C. (1995). Signal transduction and membrane traffic: The PITP/phosphoinositide connection. Cell81:659–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, O. H., Rosebrough, N. J., Farr, A. L., and Randell, R. J. (1951). Protein measurement with Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem.193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaco, M. E., Alexander, R. J., Snoek, G. T., Moldover, N. H., Wirtz, K. W., and Walden, P. D. (1998). Evidence that mammalian phosphatidylinositol transfer protein regulates phosphatidylcholine metabolism. Biochem. J.335:175–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaretou, C., Domin, J., Cockcroft, S., and Waterfield, M. D., (1997). Characterization of p150, an adaptor protein for the human phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns) 3-kinase. Substrate presentation by phosphatidylinositol transfer protein to the p150.Ptdins 3-kinase complex. J. Biol. Chem.272:2477–2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przedborski, S., Jackson-Lewis, V., Yokoyama, R., Shibata, T., Dawson, V. L., and Dawson, T. M. (1996). Role of nitric oxide in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrapyridine (MPTP)-induced dopamninergic neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci.12:1658–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sian, J., Dexter, D. T., and Lees, A. J. (1994). Alterations in glutathione levels in Parkinson's disease and other neurodegenerative disorders affecting basal ganglia. Ann. Neurol.36:348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snoek, G. T., Berrie, C. P., Geijtenbeek, T. B., van der Helm, H. A., Cadee, J. A., Iurisci, C., Corda, D., and Wirtz, K. W. (1999). Overexpression of phosphatidylinositol transfer protein alpha in NIH3T3 cells activates a phospholipase A. J. Biol. Chem.274:35393–35399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariq, M., Khan, H. A., Moutaery, K. A., and Deeb, S. A. (2001). Protective effect of quinacrine on striatal dopamine levels in 6-OHDA and MPTP models of Parkinsonism in rodents. Brain Res. Bull.54:77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, G. M. H., Cunningham, E., Fensome, A., Ball, A., Totty, N. F., and Cockcroft, S. (1993a). An essential role for Phosphatidylinositol transfer protein in phospholipase C-mmediated inositol lipid signaling. Cell74:919–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J. B., Clark, S. M., and Gioia, D. A. (1993b). Strategic sensemaking and organizational performance: Linkages among scanning, interpretation, action, and outcomes. Acad. Manage. J.36:239–270 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toborek, M., Malecki, A., Garrido, R., Mattson, M. P., Hennig, B., and Young, B. (1999). Arachidonic acid-induced oxidative injury to cultured spinal cord neurons. J. Neurochem.73:684–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, K. W. (1991). Phospholipid transfer proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem.60:73–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, K. W. (1997). Phospholipid transfer proteins revisited. Biochem. J.324:353–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda, S., Rabinovicz, S., Carasso, R. L., and Mostofsky, D. I. (2002). The role of polyunsaturated fatty acids in restoring the aging neuronal membrane. Neurobiol. Aging23:843–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambrzycka, A., (2004). Aging decreases phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bis-phosphate level but has no effect on activities of phosphoinositide kinases. Pol. J. Pharmacol.56:651–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., Dawson, V. L., and Dawson, T. M. (2000). Oxidative stress and genetics in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol. Dis.7:240–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]