Abstract

Gap junctions (GJs) are integral membrane proteins that enable the direct cytoplasmic exchange of ions and low molecular weight metabolites between adjacent cells. They are formed by the apposition of two connexons belonging to adjacent cells. Each connexon is formed by six proteins, named connexins (Cxs). Current evidence suggests that gap junctions play an important part in ensuring normal embryo development. Mutations in connexin genes have been linked to a variety of human diseases, although the precise role and the cell biological mechanisms of their action remain almost unknown. Among the big family of Cxs, several are expressed in nervous tissue but just a few are expressed in the anterior neural tube of vertebrates. Many efforts have been made to elucidate the molecular bases of Cxs cell biology and how they influence the morphogenetic signal activity produced by brain signaling centers. These centers, orchestrated by transcription factors and morphogenes determine the axial patterning of the mammalian brain during its specification and regionalization. The present review revisits the findings of GJ composed by Cx43 and Cx36 in neural tube patterning and discuss Cx43 putative enrollment in the control of Fgf8 signal activity coming from the well known secondary organizer, the isthmic organizer.

Keywords: Cx36, Cx43, Fgf8, gap junction, isthmic organizer, mammalian neural tube patterning, morphogenesis

We provide recent findings of Cx43 and Cx36 in neural tube patterning and discuss Cx43 putative enrollment in the control of Fgf8 signal activity coming from the well known secondary organizer, the isthmic organizer.

Gap junctional communication structure and function: An overview

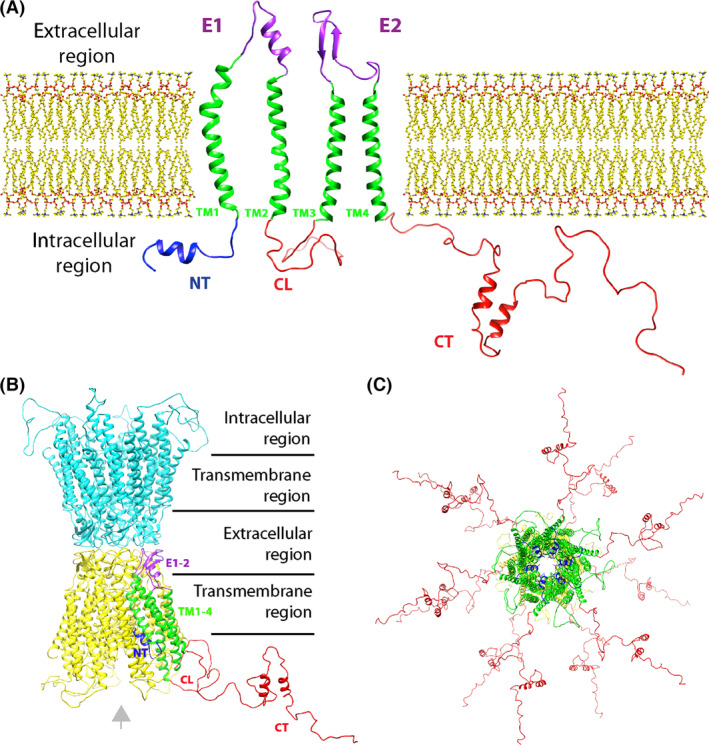

Gap Junction (GJ) plaques are aggregations of juxtaposing connexons of abutting cells, creating hydrophilic pores bypassing both plasma membranes, which constitute a direct exchange hub between the two cytoplasms. Each connexon represent an hemichannel, and is formed by six monomers of connexins (Cxs) in a hexameric disposition. Cxs are transmembrane proteins, endowed with: an N‐terminal domain (NT) facing the inner surface of the cavity, four transmembrane hydrophobic portions (TM1–4) encompassing a cytoplasmic loop (CL) between TM2 and TM3 and two extracellular loops (E1–E2) between TM1–2 and TM3–4, and a C‐terminal tail (CT) extending into the cytosol (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Connexins structure and assembly into gap junctions (GJs). The sketch depicted in (a) show all the domains of a single connexin, the GJ monomer, as if it was ideally unraveled on a 2D plane in respect to the plasma membrane of a cell. Connexin protein feature four transmembrane hydrophobic domains (green), two extracellular domains (in purple), and three cytosolic domains: one conserved N‐terminal (in blue) and two variable cytoplasmic loops (CL) and tails (CT (in red). In this particular drawing, CT and CL are Cx43's ones, base on the hypothetical 3D model by (Sorgen et al. 2004). CT and CL are mainly random coil regions, hosting post‐translational modification consensus sites, so their structure in this picture is arbitral, for length comparison. (b) Same color code as (a) is used to show the relative position of a Cx43 domains assembled into a connexon (in yellow) in the typical hexameric conformation. Note that the extracellular domains dock the interactions with the juxtaposing connexon of the neighbor cell (in cyan), thus sealing the GJ. Note the position of the N‐terminal domains (NTs), facing the lumen of the junction (also in c). Gray arrow indicates the view plane of c. (c) orthogonal vision of an homomeric Cx43 GJ. All images were obtained with “Phyre2” homology modeling using “PDB database”, and elaborated with UCSF “Chimera” program.

Historically, the first identification of a 27 kDa GJ's protein in bovine liver (Gorin et al. 1984) was rapidly followed by its cloning (Kumar & Gilula 1986) and by the discovery of further Cxs (Beyer et al. 1987; Nicholson et al. 1987). Nowadays, it has been clarified that the Cxs family is broad, counting 21 members in human and 20 in mouse (reviewed in Sohl & Willecke 2004).

The regions of maximum sequence diversity between distinct family members are the cytosolic ones, CL and CT, while NT, E1/2 and TMs topology remains strongly conserved. In fact, since the first 2D and 3D structures of Cxs were resolved with X‐Ray diffraction (Makowski et al. 1977) and electron crystallography (Unwin & Zampighi 1980; Unwin & Ennis 1984), comparative studies between different isoforms have become feasible, and Cxs cytoplasmic domains emerged as variable in length and sequence, thus accounting for the functional differences between Cxs types (see for review Bai 2016).

Gap junctions can be constituted by the same kind of Cxs (thus named homomeric) or by different monomers (thus named heteromeric), hence giving rise to exponential combination of the 20 family members, resulting in an even vaster heterogeneity of gap junctional assembly. These channels differ from each other by their unitary conductance (Rackauskas et al. 2007) permeability (Qu & Dahl 2002) and regulation (Harris 2001). The vast majority of Cxs have remarkably short half‐lives of only 1–3 h, much faster than typical integral membrane proteins (10–100 h) (Lauf et al. 2002; Laird 2006), therefore implicating a highly regulated signaling for turnover. GJs are known to allow the intercellular transfer of ions, amino acids, nucleotides, metabolites and secondary messengers (e.g., Ca++, glucose, cAMP, cGMP, ATP, IP3) while macromolecules are excluded, albeit small RNAs may pass (Suzhi et al. 2015). The first studies on GJ's permeability to large molecules in the 1960s carried on with colorant and fluorescent tracers initially wrongly included the passage of 70 KDa proteins (Serum Albumine) probably due to degradation and translocation of the reporter subunit (Kanno & Loewenstein 1966). Nowadays the cutoff is defined at around 1.5 KDa, or 1–2 nm of diameter (for long and thin molecules like small RNAs).

Regarding the gating mechanism, numerous models have been proposed during the years, and yet there is not one uniquely accepted. Several researchers believe that the regulation of GJ gating requires the presence of Ca++, (Unwin & Ennis 1984; Bennett et al. 2016). Others, suggest that the changes in cytoplasmic pH and voltage are the reason for regulation of GJ gating (Spray et al. 1979, 1981). Cx domains proposed to cause the closure of the pore are various too. Shibayama et al. proposed that both voltage and pH gating of Cx43 channels result from an interaction between CT and CL (Shibayama et al. 2006) whereas others impute a hydrogen bond network in NTs aggregates (Fig. 1b,c) (Purnick et al. 2000). Such a variety described above in GJ's gating may be due to the difficulty in the extraction of these complex membrane proteins for structure determination, and impossibility of detecting a closed GJ being sure not to affect its closure state with the fixation itself.

GJ in the nervous system

Since first identification of GJ by electron microscopy between large presynaptic terminals in cell bodies and dendrites of neurons from adult rat lateral vestibular nucleus (Sotelo & Palay 1970), many Cxs have been reported to be expressed in the nervous system. For example, both Cx32 and Cx29 are expressed in non‐compact myelin Schwann cells. Cx32 was demonstrated to form a reflexive communication pathway connecting the myelin layers. Mutations in Cx32 cause a X‐linked form of the inherited neuropathy Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth (CMTX) syndrome, thus confirming its necessity in peripheral nervous system (Bergoffen et al. 1993). On the other hand, Cx29 function is less clear, but it has been proposed to be involved in myelin‐forming glial cells proliferation (Sohl et al. 2001).

In central nervous system (CNS) instead, Cxs are reported to be expressed in astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and neurons. Oligodendrocytes express Cx32, Cx47, and Cx29, while astrocytes express Cx43, Cx30, and possibly Cx26 (Nagy et al. 2003). In these cases, GJ communication seems to be necessary for spatial buffering of ions and neurotransmitters, and may influence the recovery of tissue damage after ischemia. Mutations in Cx47 cause Pelizaeus Merzbacher–like disease while mutations in CX43 cause oculo‐dento‐digital‐dysplasia (ODDD) syndrome. Only Cx36, Cx45 and Cx30.2 have been definitively identified in nonretinal brain neurons, where they form electrical synapses, synchronizing neuronal network oscillations. Therefore, neuron–neuron coupling malfunction is suspected to play a role in the pathogenesis of epilepsy. (Sohl et al. 2005; Kreuzberg et al. 2008) Cx57 instead, is exclusively expressed by horizontal cells in the retina (Shelley et al. 2006). Several Cxs expression profile, Cx26, Cx30, Cx31.1, Cx32, Cx36 and Cx43 mRNAs, indicated that their expression is developmentally regulated in the dopaminergic neurons of substantia nigra pars compacta (Vandecasteele et al. 2006). Last but not least, Cx30.3 protein is expressed in the progenitor cells of the olfactory epithelium and in the vomeronasal organ (Zheng‐Fischhofer et al. 2007), in addition in the adult rat cochlea (Wang et al. 2010). Cx43, the focus of this review, is by far the most abundantly and widely expressed gap junction protein, and its essential role is highlighted by the fact that Cx43 knockout mice die in perinatal period due to alterations in heart morphogenesis and severe pulmonary outflow tract obstructions (Reaume et al. 1995).

Secondary organizers and Cxs in neural tube patterning

The establishment of the vertebrate's body plan is a complex process requiring the precise control of induction, patterning and morphogenesis. The idea that specific molecules might control embryogenesis, often referred to as morphogens, is a well‐established concept in developmental biology, extending back to the middle of last century. Many embryological experiments have found ready explanations in terms of a gradient(s) of a substance or cellular property that provides embryonic cells with developmental cues and is interpreted to generate the appropriate cellular response. This was formalized in the concept of ‘positional information by Wolpert in 1969 (Wolpert 1969; see in Wolpert 2009), a special interview of Wolpert L by Richardson MK). The collective cell response to exogenous cues depended on cell–cell interactions most probably to enhance sensitivity to weak or noisy stimuli (Ellison et al. 2016). In fact, GJ communication is found critically important in many biological issues including control of cell proliferation, differentiation and proper migration, embryonic development, wound healing, and the coordinated contraction of electrically coupled tissues like heart and smooth muscle (Warner 1992).

Interestingly, GJs have been assumed to play a key role in establishing the neuromeric subdivisions in the vertebrate neural tube (Puelles & Rubenstein 2003), especially in intercellular communication within the neuroepithelium (Minkoff et al. 1991; Martinez et al. 1992) suggesting the presence of region‐specific signaling mechanisms and, possibly, an impedance of cell communication among subpopulations of cells at critical stages of development. On the other hand, modulation of GJs has been proposed just to redefining pre‐existent morphogenetic fields at newly formed boundaries, and perhaps contributing to position‐dependent fate specification. Thus, the topographic distribution of the neuronal gap junction in the neuroepithelium would bear on the related mechanism of clonal restriction according to (Gulisano et al. 2000).

First experiments in GJs' pivotal role during early embryonic development were done in Xenopus morula (Warner et al. 1984), showing that the administration of a connexin antibody disrupted its function, leading to insane one‐eyed tadpoles. The concept was then extended to 8‐cell mouse embryos (Lee et al. 1987) hinting strongly at conserved roles for GJs in developmental processes across vertebrates. At later stages, dye injections at postimplantation mouse embryo blastocyst demonstrated cell–cell communication in inner cell mass and trophoblast (Lo & Gilula 1979).

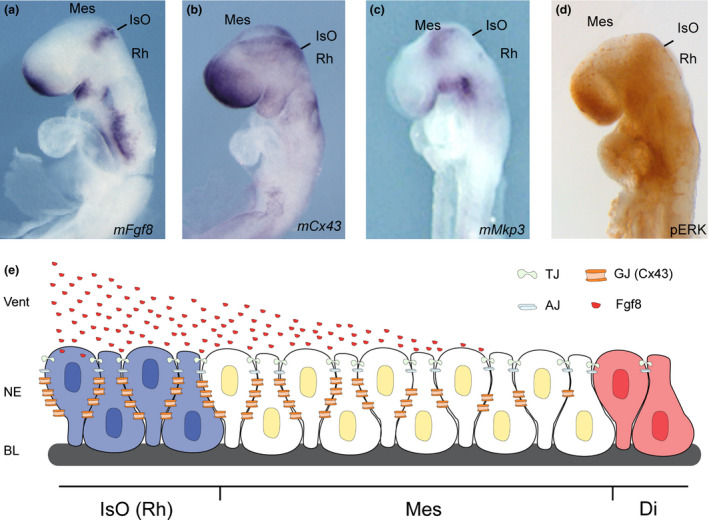

During neural plate and tube patterning, when morphogens diffusion rules axial patterning, GJs act as conduit for information flow, which depends on the ability of cells to communicate each other (Rela & Szczupak 2004). The morphogenetic regulatory processes at specific locations of the developing neural primordium has led to the concept of secondary organizers, which regulate the identity and regional polarity of neighboring neuroepithelial regions (Ruiz i Altaba 1998; for review see Nakamura et al. 2008; Vieira et al. 2010). Very recently, it was reported that polarized neuroepithelium depends on the topographical location of secondary organizers and the cues exerted from them (Crespo‐Enriquez et al. 2012). These organizers, secondary to those that operate throughout the embryo during gastrulation, usually develop within the previously broadly regionalized neuroectoderm at given genetic boundaries (frequently where cells expressing different transcription factors are juxtaposed). Their subsequent activity refines local neural identities along the AP or DV axes and regionalizing the anterior neural plate and neural tube (Meinhardt 1983; Figdor & Stern 1993; Wassef & Joyner 1997; Rubenstein et al. 1998; Joyner et al. 2000) Crespo‐Enriquez et al. 2012). Among them the isthmic organizer (IsO) at the mid‐hindbrain boundary has been extensively studied during the last three decades (Martinez & Alvarado‐Mallart 1989; Nakamura 1990; Nakamura et al. 2005; Vieira et al. 2010; for review see Wurst & Bally‐Cuif 2001). It is involved in maintaining the mid‐hindbrain molecular boundary and providing structural polarity to the adjoining regions in order to orchestrate the complex cellular diversity of the mesencephalon (rostrally) and the cerebellum (caudally) (Itasaki & Nakamura 1992; Rhinn & Brand 2001; Crespo‐Enriquez et al. 2012). Thus, it is clear that such signaling centers controls proper specification, migration and differentiation processes of nearby cells. In this sense GJ communication seems to coordinate migration events, for instance in neural crest development. Neural crest cells arise in early developmental stage from the dorsal neuroepithelium and migrate extensively through the embryo in order to reach target locations, where they differentiate in various cell types. A role for Cxs in this process is indicated by the presence of Cx43 in neural crest cells (Fig. 2), and by defects associated with Cx43 misexpression in neural crest derived‐tissues, as well as the correlation between GJ inhibition and migration defects (Lo et al. 1997). Another example of the role of GJ communication during brain patterning comes from the study during telencephalic regionalization (Elias et al. 2007). This study shows that Cxs are expressed during migration throughout cortical development. In fact, Cx43 and Cx26 were present at the contacts between migrating neurons and their scaffold radial glia, indicating that junctional coupling in migration seems to control cell cytoskeleton and the establishment of polarity, thus allowing efficient forward motion.

Figure 2.

Fgf8‐related Isthmic organizer players in mouse neurulation stage E8.0–8.5. (a–d) whole mount in situ hybridization for Fgf8 (a), Cx43 (b), Mkp3 (c) and whole mount immunohistochemistry for pERK (d). E represents the typical drawing of the morphogenetic activity of FGF8 protein arising from the isthmic organizer (IsO) in the rhombencephalon (Rh) that diffuses through the extracellular matrix and ventricle (vent), onto the mesencephalon (Mes) and diencephalon (Di) in a gradient manner. The pseudostratified neuroepithelial cells (NE) are inter‐connected and inter‐communicated by adherens junctions (AJ), tight junctions (TJ) and gap junctions (GJ‐Cx43). GJ made of Cx43 (in b) is distributed in a gradient along the NE as the protein FGF8, remembering also the expression pattern profile of Fgf8 downstream negative feedback modulator, Mkp3 (in c) and of Fgf8 intracellular MAP‐kinase product, the phosphorylated Extracellular signal‐Regulated Kinase 1/2 (pERK; in d).

Cxs and FGFs during brain patterning

It is well accepted that fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) control a variety of physiological responses during embryonic development and in adult organisms. The coordination of these events by FGFs must be tightly regulated, ensuring the correct doses at a particular time and place for proper embryogenesis to occur. The family of FGFs consists of a large group of structurally related polypeptides (Ornitz & Itoh 2015). In human, 22 FGF genes exist, 15 of which are paracrine factors, three are hormone‐like factors, and four are intracellular proteins lacking the capacity to bind FGF receptors at the cell surface.

An interesting link between FGFs and Cxs comes from the work of Bernhard Reuss and his team (Reuss et al. 1998). They chose the fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF‐2; also named bFGF) known as a potent multifunctional growth factor and highly abundant in brain. The authors demonstrated in vitro that FGF‐2 caused a reduction of Cx43‐protein, mRNA transcription, and intercellular communication revealed by dye spreading. Those changes occurred in cortical and striatal cells, but not in mesencephalic astroglial cells, and the effects were time‐ and concentration‐dependent. Others (Nadarajah et al. 1998; Cheng et al. 2004) found that the same FGF, applied to cortical progenitor cells in vitro, produced an increase in the expression of the gap junction protein Cx43 and in the mRNA encoding Cx43 but not of Cx26 mRNA. The latter results suggest that GJ channels provide a direct link for mitogens released in response to bFGF to effectively regulate proliferation during brain formation.

A member of this family, Fgf8, was found to be highly expressed in the most anterior hindbrain and the isthmic organizer (IsO; Crossley & Martin 1995). Fgf8 is required to maintain the expression of genes and transcription factors that play a role in neural tube patterning. Moreover, it is essential for cell survival, as evidenced by the finding that partial inactivation of Fgf8 at early neural plate stages causes extensive cell death throughout the mesencephalon and rostral hindbrain, resulting in full deletion of the midbrain and cerebellum (Martínez et al. 2012).

Fgf8 expression at E8.5 mouse embryos is detected in two distinct domains in the developing neural plate, one at its rostral end, and the other in a more caudal position in the region between the prospective midbrain and hindbrain (Fig. 2a). From E8.5 until E14.5 the caudal Fgf8 expression domain is restricted to a sharp, narrow band of neuroepithelial cells that extends from the dorsal midline around the lateral walls of the neural tube in the region of the isthmic constriction. This opened ring in the ventral midline lies at the interface of Otx2 and Gbx2 positive neuroepithelial cells (Millet et al. 1999; Garda et al. 2001; Liu & Joyner 2001). The caudal limit of Otx2 expression and the rostral limit of Gbx2 therefore mark the mid‐hindbrain molecular boundary (Millet et al. 1996; Martinez‐Barbera et al. 2001; Hidalgo‐Sanchez et al. 2005). FGF8 signal may act at the IsO in concert with other signaling molecules, such as Wingless 1, Sonic Hedgehog and transforming growth factor family members (for review see Vieira et al. 2010). On the other hand, mesencephalic and diencephalic epithelia are also receptive to FGF8 (Crossley et al. 1996; Martinez et al. 1999) which possibly regulates gene expression and neuroepithelial polarity in the alar plate of these territories (Vieira & Martinez 2006; Crespo‐Enriquez et al. 2012). A decreasing gradient of FGF8 protein concentration in the alar plate of the isthmus and rhombomere 1 is fundamental for cell survival and the differential development of cerebellar regions (Wassarman et al. 1997; Chi et al. 2003; Nakamura et al. 2005; Basson et al. 2008).

Cx43 has a very interesting expression pattern profile during neurulation process. Its expression was found in the telencephalon, with strong signal at the roof and a gradient pattern extending caudally. In the midbrain, low levels of hybridization signal were observed, while in the hindbrain, a wide transversal expression (again, as a ring) was detected at the isthmic region that gradually diffuses either rostrally to mesencephalon or caudally to the cerebellar anlage (Fig. 2b). Another remarkable staining is observed at the presumptive neural crest fold (Ruangvoravat & Lo 1992). Although not yet proved, based on these similarities on expression profile, it is plausible to think that Fgf8 requires stable conditions of Cx43 to control in space and time its planar induction properties along the anterior‐posterior axis (Ruangvoravat & Lo 1992). In this sense, Levin and Mercola reported the initial hint of long range signaling by GJC in 1998. By testing the hypothesis that Cx43 was important for normal laterality in vertebrate frog and chick primitive streak, they proposed that left‐right information is transferred unidirectionally throughout the epiblast by GJC in order to pattern left‐sided Shh expression at Hensen's node (Levin & Mercola 1998).

Cx36, the major detected Cx in neurons, is exclusively expressed in GABAergic interneurons in the adult mammalian brain. Cx36‐positive neurons have been described in the retina, dentate gyrus, CA1, CA3 and CA4 regions of the hippocampus, piriform cortex, amygdala, cerebellum, mesencephalon, suprachiasmatic nucleus, thalamus, hypothalamus and various brainstem nuclei (Condorelli et al. 1998; Sohl et al. 1998; Degen et al. 2004; Rash et al. 2007; Helbig et al. 2010)

Interesting as ventral derivatives, Cx36 has been detected in the basal ganglia, including nucleus accumbens (Condorelli et al. 1998), in dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra (Allison et al. 2006; Vandecasteele et al. 2006) that project to the neostriatum, and in GABAergic interneurons of the tegmental ventral area (Allison et al. 2006). Cx36 transcript starts to be faintly expressed at E7 in decidual annexes (extraembryonic tissue). First detection in embryonic structures is evident only at E9.5, when it localizes in the most rostral region of the developing brain, the forebrain (Gulisano et al. 2000). It is worth noting that at this stage the forebrain is undertaking a regionalization process into different neuromeric subdivisions, the prosomeres (Puelles & Rubenstein 2003). Thus, during these stages the Cx36 GJs could be mainly involved in coupling of neuroepithelial cells at the onset of neurogenesis, possibly establishing a functional coupled compartment (neuromere).

At later stages instead, from E12.5, its expression is in the diencephalon in the pretectum (prosomere 1;p1) and delineating the zona limitans intrathalamica (ZLI), another secondary organizer located between the future thalamus and prethalamus (between p2 and p3; Puelles & Rubenstein 2003, Vieira et al. 2010) will differentiate. Finally in ventral secondary prosencephalon, the future hypothalamus was also positive for Cx36 hybridization signal. Thus, at this stage the Cx36 GJs could be involved in defining properties of the boundaries themselves via direct coupling. In fact, Cx36 GJs may play a role in confining the intercellular diffusion of morphogenetic molecules to single neuromere, in agreement with previous studies (Martinez et al. 1992) These observations lead to the question about the nature of the molecules that are confined or are able to pass through these Cx36 GJ channels located at these boundaries. Further investigations should undertake these remarkable questions.

Fgf8 long range signaling and Cx43 in morphogenesis

The proposed mechanism by which FGF8 signaling spreads over a field of target cells, at least in zebrafish, is established and maintained by two essential factors: firstly, free diffusion of single FGF8 molecules away from the secretion source through the extracellular space and secondly, an absorptive function of the receiving cells regulated by receptor‐mediated endocytosis (Nowak et al. 2011; Muller et al. 2013). Therefore, Fgf8 receiving cells seem to control both, the propagation width and the signal strength of the morphogen (Yu et al. 2009). Thus, it is reasonable to think that these neuroepithelial cells may respond to exogenous morphogens depending on the cell–cell interaction. The multicellular sensitivity rather than monocellular, may enable detection of and respond properly even to shallow growth factor gradients (Fig. 2e) (Ellison et al. 2016).

Fibroblast growth factor signaling is mediated via receptor tyrosine‐ kinases (RTKs). These transmembrane FGF receptors (FGFRs) activate signaling cascades including the phosphatidylinositol‐3 kinase (PI3K) and Ras‐ERK pathways (MAPK) (Niehrs & Meinhardt 2002). The regulation of Cxs lay in the intracellular domains, CTs and CLs. These chain domains host characteristic and often multiple consensus sequences for post‐translational modifications fostering changes in the channel trafficking, protein‐protein interaction, and gating. Although there is evidence of phosphorylation, hydroxylation, acetylation, nitrosylation, and palmitoylation, the most important and characterized of these modifications is by far, phosphorylation. So far, various kinases have been identified as targeting Cxs, among them Akt, PKC, MAPKs, tyrosine kinases, (Contreras et al. 2003)

In the mouse neural tube Mkp3 (Fig. 2d), Sef and those belonging to the Sprouty family are feedback modulators induced by Fgf8 expression in the Fgf8‐related secondary organizers and may determine the spatial reduction of Fgf8 activity in a gradient manner by interaction with the intracellular mechanism of the MAP kinase cascade (Furthauer et al. 2002; Tsang et al. 2002; Echevarria et al. 2005a; Echevarria et al. 2005b; Vieira & Martinez 2005). In particular, Mkp3 selectively inactivates the ERK1/2 class of MAP kinases by dephosphorylation leading to catalytic inactivation. It thus prevents translocation into the nucleus, resulting in inhibition of ERK1/2‐dependent transcription (Fig. 2c) (Camps et al. 1998; Muda et al. 1998; Crespo‐Enriquez et al. 2012). In the same manner MAP kinases have been shown to phosphorylate Cx43 on serine residues at the cytoplasmatic CT (Warn‐Cramer et al. 1998) and ERKs all have been reported to phosphorylate Cx43 (Cameron et al. 2003; Leykauf et al. 2003). Blocking GJs pharmacologically inhibits the proliferative of bFgfs. Cx43 expression increases proliferation in cultures not treated with bFGF but does not increase proliferation in cultures already treated with bFGF. Together, this suggests that the upregulation of Cx43 through MAP kinase signaling is necessary and sufficient for the proliferative effects of bFGF (Nadarajah et al. 1998; Cheng et al. 2004). Several studies have disclosed the position preferences of neuroepithelial cells to FGF8 planar signal activity. The differential orientation and polarity of the FGF8 signal seems to be directly dependent on the spatial position of mouse Fgf8‐related secondary organizers and on the activity of the negative modulators, Mkp3 (Echevarria et al. 2005a,b a), Sef (Furthauer et al. 2002; Tsang et al. 2002) and Sprouty1/2 (Minowada et al. 1999), for review see (Korsensky & Ron 2016). Thus, communication through the direct intercellular pathway mediated by gap junction may act alongside cellular interactions achieved by the release of growth factors and their subsequent binding to membrane receptors to coordinate embryogenesis and morphogenesis (Levin 2007).

Concluding remarks

Here we have reviewed data suggesting that gap junction communication mediates neuronal migration and neuronal differentiation and morphogenetic activity during neural tube patterning. Gap junction‐mediated signaling is still a virgin field when considering the largely unknown downstream signaling pathways of connexin biology. One of the major challenges in the field of neuroembryology and connexins will be to identify the molecules exchanged between coupled cells and how they regulate the cell–cell multicellular response to exogenous cues. Current data suggest that hemichannels on cortical radial glial cells mediate ATP release that activates purinergic receptors and initiates Ca2+ waves in the cortical ventricular zone (Weissman et al. 2004). Recent reports suggest that gap junction expression might coordinate the expression of networks of genes, the so‐called connexin transcriptome, which might have diverse effects that are largely unexplored (Spray & Iacobas 2007). Thus we should take note that when designing future studies to discern the role of gap junctions in neural tube development, not only will it be necessary to consider the possible roles of gap junctions as channels, hemichannels, adhesions or signaling molecules but also how these functions are integrated into the cells signaling pathways and communication machinery for the final proper development of the brain as we know.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Eduardo Puelles for critical reading of the manuscript and Ms Francisca Almagro for technical assistance. Ms Camilla Bosone Contract and manuscript was supported by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología Grant (BFU2013‐48230‐P).

References

- Allison, D. W. , Ohran, A. J. , Stobbs, S. H. , Mameli, M. , Valenzuela, C. F. , Sudweeks, S. N. , Ray, A. P. , Henriksen, S. J. & Steffensen, S. C. 2006. Connexin‐36 gap junctions mediate electrical coupling between ventral tegmental area GABA neurons. Synapse. 60, 20–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, D. 2016. Structural analysis of key gap junction domains‐Lessons from genome data and disease‐linked mutants. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 50, 74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson, M. A. , Echevarria, D. , Ahn, C. P. , Sudarov, A. , Joyner, A. L. , Mason, I. J. , Martinez, S. & Martin, G. R. 2008. Specific regions within the embryonic midbrain and cerebellum require different levels of FGF signaling during development. Development. 135, 889–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, B. C. , Purdy, M. D. , Baker, K. A. , Acharya, C. , McIntire, W. E. , Stevens, R. C. , Zhang, Q. , Harris, A. L. , Abagyan, R. & Yeager, M. 2016. An electrostatic mechanism for Ca(2 + )‐mediated regulation of gap junction channels. Nat. Commun. 7, 8770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergoffen, J. , Scherer, S. S. , Wang, S. , Scott, M. O. , Bone, L. J. , Paul, D. L. , Chen, K. , Lensch, M. W. , Chance, P. F. & Fischbeck, K. H. 1993. Connexin mutations in X‐linked Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease. Science 262, 2039–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, E. C. , Paul, D. L. & Goodenough, D. A. 1987. Connexin43: a protein from rat heart homologous to a gap junction protein from liver. J. Cell Biol. 105, 2621–2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, S. J. , Malik, S. , Akaike, M. , Lerner‐Marmarosh, N. , Yan, C. , Lee, J. D. , Abe, J. & Yang, J. 2003. Regulation of epidermal growth factor‐induced connexin 43 gap junction communication by big mitogen‐activated protein kinase1/ERK5 but not ERK1/2 kinase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 18682–18688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camps, M. , Nichols, A. , Gillieron, C. , Antonsson, B. , Muda, M. , Chabert, C. , Boschert, U. & Arkinstall, S. 1998. Catalytic activation of the phosphatase MKP‐3 by ERK2 mitogen‐activated protein kinase. Science. 280, 1262–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, A. , Tang, H. , Cai, J. , Zhu, M. , Zhang, X. , Rao, M. & Mattson, M. P. 2004. Gap junctional communication is required to maintain mouse cortical neural progenitor cells in a proliferative state. Dev. Biol. 272, 203–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi, C. L. , Martinez, S. , Wurst, W. & Martin, G. R. 2003. The isthmic organizer signal FGF8 is required for cell survival in the prospective midbrain and cerebellum. Development. 130, 2633–2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condorelli, D. F. , Parenti, R. , Spinella, F. , Trovato Salinaro, A. , Belluardo, N. , Cardile, V. & Cicirata, F. 1998. Cloning of a new gap junction gene (Cx36) highly expressed in mammalian brain neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 10, 1202–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, J. E. , Sáez, J. C. , Bukauskas, F. F. & Bennett, M. V. 2003. Gating and regulation of connexin 43 (Cx43) hemichannels. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 11388–11393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo‐Enriquez, I. , Partanen, J. , Martinez, S. & Echevarria, D. 2012. Fgf8‐related secondary organizers exert different polarizing planar instructions along the mouse anterior neural tube. PLoS One. 7, e39977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, P. H. & Martin, G. R. 1995. The mouse Fgf8 gene encodes a family of polypeptides and is expressed in regions that direct outgrowth and patterning in the developing embryo. Development. 121, 439–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, P. H. , Martinez, S. & Martin, G. R. 1996. Midbrain development induced by FGF8 in the chick embryo. Nature 380, 66–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degen, J. , Meier, C. , Van Der Giessen, R. S. , Sohl, G. , Petrasch‐Parwez, E. , Urschel, S. , Dermietzel, R. , Schilling, K. , De Zeeuw, C. I. & Willecke, K. 2004. Expression pattern of lacZ reporter gene representing connexin36 in transgenic mice. J Comp Neurol. 473, 511–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria, D. , Belo, J. A. & Martinez, S. 2005a. Modulation of Fgf8 activity during vertebrate brain development. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 49, 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria, D. , Martinez, S. , Marques, S. , Lucas‐Teixeira, V. & Belo, J. A. 2005b. Mkp3 is a negative feedback modulator of Fgf8 signaling in the mammalian isthmic organizer. Dev. Biol. 277, 114–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias, L. A. , Wang, D. D. & Kriegstein, A. R. 2007. Gap junction adhesion is necessary for radial migration in the neocortex. Nature 448, 901–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, D. , Mugler, A. , Brennan, M. D. , Lee, S. H. , Huebner, R. J. , Shamir, E. R. , Woo, L. A. , Kim, J. , Amar, P. , Nemenman, I. , Ewald, A. J. & Levchenko, A. 2016. Cell‐cell communication enhances the capacity of cell ensembles to sense shallow gradients during morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 113, E679–E688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figdor, M. C. & Stern, C. D. 1993. Segmental organization of embryonic diencephalon. Nature 363, 630–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furthauer, M. , Lin, W. , Ang, S. L. , Thisse, B. & Thisse, C. 2002. Sef is a feedback‐induced antagonist of Ras/MAPK‐mediated FGF signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 170–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garda, A. L. , Echevarria, D. & Martinez, S. 2001. Neuroepithelial co‐expression of Gbx2 and Otx2 precedes Fgf8 expression in the isthmic organizer. Mech. Dev. 101, 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorin, M. B. , Yancey, S. B. , Cline, J. , Revel, J. P. & Horwitz, J. 1984. The major intrinsic protein (MIP) of the bovine lens fiber membrane: characterization and structure based on cDNA cloning. Cell 39, 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulisano, M. , Parenti, R. , Spinella, F. & Cicirata, F. 2000. Cx36 is dynamically expressed during early development of mouse brain and nervous system. NeuroReport 11, 3823–3828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A. L. 2001. Emerging issues of connexin channels: biophysics fills the gap. Q. Rev. Biophys. 34, 325–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbig, I. , Sammler, E. , Eliava, M. , Bolshakov, A. P. , Rozov, A. , Bruzzone, R. , Monyer, H. & Hormuzdi, S. G. 2010. In vivo evidence for the involvement of the carboxy terminal domain in assembling connexin 36 at the electrical synapse. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 45, 47–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo‐Sanchez, M. , Millet, S. , Bloch‐Gallego, E. & Alvarado‐Mallart, R. M. 2005. Specification of the meso‐isthmo‐cerebellar region: the Otx2/Gbx2 boundary. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 49, 134–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itasaki, N. & Nakamura, H. 1992. Rostrocaudal polarity of the tectum in birds: correlation of en gradient and topographic order in retinotectal projection. Neuron 8, 787–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner, A. L. , Liu, A. & Millet, S. 2000. Otx2, Gbx2 and Fgf8 interact to position and maintain a mid‐hindbrain organizer. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12, 736–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno, Y. & Loewenstein, W. R. 1966. Cell‐to‐cell passage of large molecules. Nature 212, 629–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korsensky, L. & Ron, D. 2016. “Regulation of FGF signaling: Recent insights from studying positive and negative modulators”. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 53, 101–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzberg, M. M. , Deuchars, J. , Weiss, E. , Schober, A. , Sonntag, S. , Wellershaus, K. , Draguhn, A. & Willecke, K. 2008. Expression of connexin30.2 in interneurons of the central nervous system in the mouse. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 37, 119–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N. M. & Gilula, N. B. 1986. Cloning and characterization of human and rat liver cDNAs coding for a gap junction protein. J. Cell Biol. 103, 767–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird, D. W. 2006. Life cycle of connexins in health and disease. Biochem J. 394(Pt 3), 527–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauf, U. , Giepmans, B. N. , Lopez, P. , Braconnot, S. , Chen, S. C. & Falk, M. M. 2002. Dynamic trafficking and delivery of connexons to the plasma membrane and accretion to gap junctions in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 99, 10446–10451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. , Gilula, N. B. & Warner, A. E. 1987. Gap junctional communication and compaction during preimplantation stages of mouse development. Cell 51, 851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin, M. 2007. Gap junctional communication in morphogenesis. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 94, 186–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin, M. & Mercola, M. 1998. The compulsion of chirality: toward an understanding of left‐right asymmetry. Genes Dev. 12, 763–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leykauf, K. , Durst, M. & Alonso, A. 2003. Phosphorylation and subcellular distribution of connexin43 in normal and stressed cells. Cell Tissue Res. 311, 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A. & Joyner, A. L. 2001. EN and GBX2 play essential roles downstream of FGF8 in patterning the mouse mid/hindbrain region. Development 128, 181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo, C. W. & Gilula, N. B. 1979. Gap junctional communication in the post‐implantation mouse embryo. Cell 18, 411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo, C. W. , Cohen, M. F. , Huang, G. Y. , Lazatin, B. O. , Patel, N. , Sullivan, R. , Pauken, C. & Park, S. M. 1997. Cx43 gap junction gene expression and gap junctional communication in mouse neural crest cells. Dev. Genet. 20, 119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makowski, L. , Caspar, D. L. , Phillips, W. C. & Goodenough, D. A. 1977. Gap junction structures. II. Analysis of the x‐ray diffraction data. J. Cell Biol. 74, 629–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, S. & Alvarado‐Mallart, R. M. 1989. Transplanted mesencephalic quail cells colonize selectively all primary visual nuclei of chick diencephalon: a study using heterotopic transplants. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 47, 263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, S. , Geijo, E. , Sanchez‐Vives, M. V. , Puelles, L. & Gallego, R. 1992. Reduced junctional permeability at interrhombomeric boundaries. Development 116, 1069–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, S. , Crossley, P. H. , Cobos, I. , Rubenstein, J. L. & Martin, G. R. 1999. FGF8 induces formation of an ectopic isthmic organizer and isthmocerebellar development via a repressive effect on Otx2 expression. Development 126, 1189–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, S. , Puelles, E. , Puelles, L. & Echevarria, D. . (2012). Molecular regionalization of the developing neural tube.The Mouse Nervous System (ed. Watson C., Paxinos G. & Puelles L.) Academic Press, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez‐Barbera, J. P. , Signore, M. , Boyl, P. P. , Puelles, E. , Acampora, D. , Gogoi, R. , Schubert, F. , Lumsden, A. & Simeone, A. 2001. Regionalisation of anterior neuroectoderm and its competence in responding to forebrain and midbrain inducing activities depend on mutual antagonism between OTX2 and GBX2. Development 128, 4789–4800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt, H. 1983. Cell determination boundaries as organizing regions for secondary embryonic fields. Dev. Biol. 96, 375–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millet, S. , Bloch‐Gallego, E. , Simeone, A. & Alvarado‐Mallart, R. M. 1996. The caudal limit of Otx2 gene expression as a marker of the midbrain/hindbrain boundary: a study using in situ hybridisation and chick/quail homotopic grafts. Development 122, 3785–3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millet, S. , Campbell, K. , Epstein, D. J. , Losos, K. , Harris, E. & Joyner, A. L. 1999. A role for Gbx2 in repression of Otx2 and positioning the mid/hindbrain organizer. Nature 401, 161–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkoff, R. , Parker, S. B. & Hertzberg, E. L. 1991. Analysis of distribution patterns of gap junctions during development of embryonic chick facial primordia and brain. Development 111, 509–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minowada, G. , Jarvis, L. A. , Chi, C. L. , Neubuser, A. , Sun, X. , Hacohen, N. , Krasnow, M. A. & Martin, G. R. 1999. Vertebrate Sprouty genes are induced by FGF signaling and can cause chondrodysplasia when overexpressed. Development 126, 4465–4475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muda, M. , Theodosiou, A. , Gillieron, C. , Smith, A. , Chabert, C. , Camps, M. , Boschert, U. , Rodrigues, N. , Davies, K. , Ashworth, A. & Arkinstall, S. 1998. The mitogen‐activated protein kinase phosphatase‐3 N‐terminal noncatalytic region is responsible for tight substrate binding and enzymatic specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 9323–9329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, P. , Rogers, K. W. , Yu, S. R. , Brand, M. & Schier, A. F. 2013. Morphogen transport. Development 140, 1621–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadarajah, B. , Makarenkova, H. , Becker, D. L. , Evans, W. H. & Parnavelas, J. G. 1998. Basic FGF increases communication between cells of the developing neocortex. J. Neurosci. 18, 7881–7890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, J. I. , Ionescu, A. V. , Lynn, B. D. & Rash, J. E. 2003. Coupling of astrocyte connexins Cx26, Cx30, Cx43 to oligodendrocyte Cx29, Cx32, Cx47: Implications from normal and connexin32 knockout mice. Glia 44, 205–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, H. 1990. Do CNS anlagen have plasticity in differentiation? Analysis in quail‐chick chimera. Brain Res. 511, 122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, H. , Katahira, T. , Matsunaga, E. & Sato, T. 2005. Isthmus organizer for midbrain and hindbrain development. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 49, 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, H. , Sato, T. & Suzuki‐Hirano, A. 2008. Isthmus organizer for mesencephalon and metencephalon. Dev. Growth Differ. 50(Suppl 1), S113–S118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, B. , Dermietzel, R. , Teplow, D. , Traub, O. , Willecke, K. & Revel, J. P. 1987. Two homologous protein components of hepatic gap junctions. Nature 329, 732–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehrs, C. & Meinhardt, H. 2002. Modular feedback. Nature 417, 35–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M. , Machate, A. , Yu, S. R. , Gupta, M. & Brand, M. 2011. Interpretation of the FGF8 morphogen gradient is regulated by endocytic trafficking. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornitz, D. M. & Itoh, N. 2015. The Fibroblast Growth Factor signaling pathway. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 4, 215–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puelles, L. & Rubenstein, J. L. 2003. Forebrain gene expression domains and the evolving prosomeric model. Trends Neurosci. 26, 469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purnick, P. E. , Benjamin, D. C. , Verselis, V. K. , Bargiello, T. A. & Dowd, T. L. 2000. Structure of the amino terminus of a gap junction protein. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 381, 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y. & Dahl, G. 2002. Function of the voltage gate of gap junction channels: selective exclusion of molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 99, 697–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rackauskas, M. , Verselis, V. K. & Bukauskas, F. F. 2007. Permeability of homotypic and heterotypic gap junction channels formed of cardiac connexins mCx30.2, Cx40, Cx43, and Cx45. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 293, H1729–H1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash, J. E. , Olson, C. O. , Davidson, K. G. , Yasumura, T. , Kamasawa, N. & Nagy, J. I. 2007. Identification of connexin36 in gap junctions between neurons in rodent locus coeruleus. Neuroscience 147, 938–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaume, A. G. , de Sousa, P. A. , Kulkarni, S. , Langille, B. L. , Zhu, D. , Davies, T. C. , Juneja, S. C. , Kidder, G. M. & Rossant, J. 1995. Cardiac malformation in neonatal mice lacking connexin43. Science 267, 1831–1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rela, L. & Szczupak, L. 2004. Gap junctions: their importance for the dynamics of neural circuits. Mol Neurobiol. 30, 341–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuss, B. , Dermietzel, R. & Unsicker, K. 1998. Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF‐2) differentially regulates connexin (cx) 43 expression and function in astroglial cells from distinct brain regions. Glia 22, 19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhinn, M. & Brand, M. 2001. The midbrain–hindbrain boundary organizer. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 11, 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruangvoravat, C. P. & Lo, C. W. 1992. Connexin 43 expression in the mouse embryo: localization of transcripts within developmentally significant domains. Dev. Dyn. 194, 261–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz i Altaba, A. 1998. Neural patterning. Deconstructing the organizer. Nature 391, 748–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein, J. L. , Shimamura, K. , Martinez, S. & Puelles, L. 1998. Regionalization of the prosencephalic neural plate. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 21, 445–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelley, J. , Dedek, K. , Schubert, T. , Feigenspan, A. , Schultz, K. , Hombach, S. , Willecke, K. & Weiler, R. 2006. Horizontal cell receptive fields are reduced in connexin57‐deficient mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 3176–3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibayama, J. , Gutierrez, C. , Gonzalez, D. , Kieken, F. , Seki, A. , Carrion, J. R. , Sorgen, P. L. , Taffet, S. M. , Barrio, L. C. & Delmar, M. 2006. Effect of charge substitutions at residue his‐142 on voltage gating of connexin43 channels. Biophys. J. 91, 4054–4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohl, G. & Willecke, K. 2004. Gap junctions and the connexin protein family. Cardiovasc. Res. 62, 228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohl, G. , Degen, J. , Teubner, B. & Willecke, K. 1998. The murine gap junction gene connexin36 is highly expressed in mouse retina and regulated during brain development. FEBS Lett. 428, 27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohl, G. , Eiberger, J. , Jung, Y. T. , Kozak, C. A. & Willecke, K. 2001. The mouse gap junction gene connexin29 is highly expressed in sciatic nerve and regulated during brain development. Biol. Chem. 382, 973–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohl, G. , Maxeiner, S. & Willecke, K. 2005. Expression and functions of neuronal gap junctions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorgen, P. L. , Duffy, H. S. , Sahoo, P. , Coombs, W. , Delmar, M. & Spray, D. C. 2004. Structural changes in the carboxyl terminus of the gap junction protein connexin43 indicates signaling between binding domains for c‐Src and zonula occludens‐1. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 54695–54701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotelo, C. & Palay, S. L. 1970. The fine structure of the lateral vestibular nucleus in the rat: II. The synaptic organization. Brain Res. 18, 93–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spray, D. C. & Iacobas, D. A. 2007. Organizational principles of the connexin‐related brain transcriptome. J. Membr. Biol. 218, 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spray, D. C. , Harris, A. L. & Bennett, M. V. 1979. Voltage dependence of junctional conductance in early amphibian embryos. Science 204, 432–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spray, D. C. , Harris, A. L. & Bennett, M. V. 1981. Gap junctional conductance is a simple and sensitive function of intracellular pH. Science 211, 712–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzhi, Z. , Liang, T. , Yuexia, P. , Lucy, L. , Xiaoting, H. , Yuan, Z. & Qin, W. 2015. Gap Junctions Enhance the Antiproliferative Effect of MicroRNA‐124‐3p in Glioblastoma Cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 230, 2476–2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, M. , Friesel, R. , Kudoh, T. & Dawid, I. B. 2002. Identification of Sef, a novel modulator of FGF signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 165–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin, P. N. & Ennis, P. D. 1984. Two configurations of a channel‐forming membrane protein. Nature 307, 609–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin, P. N. & Zampighi, G. 1980. Structure of the junction between communicating cells. Nature 283, 545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandecasteele, M. , Glowinski, J. & Venance, L. 2006. Connexin mRNA expression in single dopaminergic neurons of substantia nigra pars compacta. Neurosci. Res. 56, 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, C. & Martinez, S. 2005. Experimental study of MAP kinase phosphatase‐3 (Mkp3) expression in the chick neural tube in relation to Fgf8 activity. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 49, 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, C. & Martinez, S. 2006. Sonic hedgehog from the basal plate and the zona limitans intrathalamica exhibits differential activity on diencephalic molecular regionalization and nuclear structure. Neuroscience 143, 129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, C. , Pombero, A. , Garcia‐Lopez, R. , Gimeno, L. , Echevarria, D. & Martinez, S. 2010. Molecular mechanisms controlling brain development: an overview of neuroepithelial secondary organizers. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 54, 7–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. H. , Yang, J. J. , Lin, Y. C. , Yang, J. T. & Li, S. Y. 2010. Novel expression patterns of connexin 30.3 in adult rat cochlea. Hear. Res. 265, 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warn‐Cramer, B. J. , Cottrell, G. T. , Burt, J. M. & Lau, A. F. 1998. Regulation of connexin‐43 gap junctional intercellular communication by mitogen‐activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 9188–9196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner, A. 1992. Gap junctions in development–a perspective. Semin. Cell Biol. 3, 81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner, A. E. , Guthrie, S. C. & Gilula, N. B. 1984. Antibodies to gap‐junctional protein selectively disrupt junctional communication in the early amphibian embryo. Nature 311, 127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassarman, K. M. , Lewandoski, M. , Campbell, K. , Joyner, A. L. , Rubenstein, J. L. , Martinez, S. & Martin, G. R. 1997. Specification of the anterior hindbrain and establishment of a normal mid/hindbrain organizer is dependent on Gbx2 gene function. Development 124, 2923–2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassef, M. & Joyner, A. L. 1997. Early mesencephalon/metencephalon patterning and development of the cerebellum. Perspect. Dev. Neurobiol. 5, 3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman, T. A. , Riquelme, P. A. , Ivic, L. , Flint, A. C. & Kriegstein, A. R. 2004. Calcium waves propagate through radial glial cells and modulate proliferation in the developing neocortex. Neuron 43, 647–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert, L. 2009. Diffusible gradients are out ‐ an interview with Lewis Wolpert. Interviewed by Richardson, Michael K. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 53, 659–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert, L. 1969. Positional information and the spatial pattern of cellular differentiation. J. Theor. Biol. 25, 1–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurst, W. & Bally‐Cuif, L. 2001. Neural plate patterning: upstream and downstream of the isthmic organizer. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S. R. , Burkhardt, M. , Nowak, M. , Ries, J. , Petrasek, Z. , Scholpp, S. , Schwille, P. & Brand, M. 2009. Fgf8 morphogen gradient forms by a source‐sink mechanism with freely diffusing molecules. Nature 461, 533–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng‐Fischhofer, Q. , Schnichels, M. , Dere, E. , Strotmann, J. , Loscher, N. , McCulloch, F. , Kretz, M. , Degen, J. , Reucher, H. , Nagy, J. I. , Peti‐Peterdi, J. , Huston, J. P. , Breer, H. & Willecke, K. 2007. Characterization of connexin30.3‐deficient mice suggests a possible role of connexin30.3 in olfaction. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 86, 683–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]