Abstract

Background:

This paper aims to perform a bibliometric analysis of research pertaining to the nursing care of infected wounds. It also aims to examine the current focal points and trends in research development. The paper offers research references that may be useful for practitioners interested in related areas.

Methods:

The Web of Science Core Collection database was queried for publications pertaining to infected wound care. Publication trends and proportions were analyzed using Graphpad Prism v8.0.2. CiteSpace (6.2.4R [64-bit]) and VOSviewer (version 1.6.18) were employed to assess the literature and conduct mapping.

Results:

The Web of Science Core Collection database contains 3868 literature related to wound infection care, including 3327 articles and 541 reviews. The literature concerned 117 countries and territories, 4673 institutions, and 20,161 authors. The growth rate of literature was relatively slow before 2015 and markedly accelerated after 2016. Among them, the United States occupies the absolute dominance in research in this field, publishing 37.25% of the papers, and the United States occupies 8 of the top 10 scientific institutions that publish papers. The University of Harvard has published the largest number of papers. Keyword analysis shows a total of 1125 keywords, and through reference literature and time clustering analysis shows that wound healing, sepsis, spine surgery, postoperative infection, nanocrystalline silver, beta lactamase are the current research hotspots.

Conclusion:

The escalating rate of literary expansion since 2016 suggests that this domain is garnering an increasingly significant amount of interest. Minimizing the risk of patient wound infection is crucial in reducing patients’ discomfort and facilitating their prompt recovery. The literature analysis presented in this study serves as a valuable resource for comprehending the current state of the subject and identifying the current areas of focus.

Keywords: Bibliometric analysis, Infected wounds, Nursing care, Wound healing

1. Introduction

Wound infections provide substantial difficulties in the healthcare field, especially when it comes to chronic wounds and patients who are severely ill.[1,2] Prompt detection and treatment of wound infections are essential for facilitating the healing process and averting problems.[3,4] Nurses have a crucial role in the care of wounds, since they need to possess information about the processes of wound healing, the identification of infections, and the use of management strategies that are based on evidence.[5,6] Nevertheless, observational studies have identified discrepancies between the recommended and actual practices for wound care, underscoring the necessity for enhanced adherence to guidelines.[6] For consistent and efficient therapy of wound infections in hospital settings, it is crucial to utilize multidisciplinary techniques and evidence-based guidelines.[7] Comprehending the typical organisms that cause infections and using antibiotics appropriately is essential for the management of antimicrobial treatment, since the improper use of antibiotics in wound care continues to be an issue.[8] Continual education and application of evidence-based techniques are essential for improving the prevention and treatment outcomes of wound infections.

Bibliometric analysis have been employed to investigate research patterns in different facets of wound healing and infection. Research has investigated the role of biofilms in wound healing,[9] the occurrence of periprosthetic joint infection after total knee arthroplasty,[10] the effectiveness of Aloe vera in wound healing,[11] and the relationship between fracture and infection.[12] These assessments offer valuable insights into worldwide research trends by identifying the prominent countries, organizations, journals, and authors that contribute to each specific topic. The United States often emerges as a significant contributor in several scientific endeavors. Current study areas of interest encompass biotechnology methodologies and drug-delivery approaches for Aloe vera as well as enhanced diagnosis of infections associated with fractures.[13] Although bibliometric studies provide significant insights into research landscapes, certain areas, such as periprosthetic joint infection, suffer from a dearth of high-level evidence studies.[14] This highlights the necessity for additional randomized controlled trials.[15]

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data collection

The Web of Science Core Collection database is best for literature analysis since it accurately categorizes literary genres. We chose this database for our search. On June 13, 2023, we searched Web of Science for wound infection care articles. Articles from 2004 to 2023 were included. The search criteria were: ((TS = (nursing)) OR TS = (care)) OR TS= (“nursing care”) AND ((TS= (“Wound Infection”)) OR TS= (“Infection, Wound”)) OR (TS= (“Infections, Wound”)). The literature screening for this study included (1) complete texts of highly relevant wound infection care publications; (2) English-language articles and review manuscripts; and (3) articles published between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2023. The following were exclusion criteria. The publications were conference abstracts, news articles, briefs, etc, not wound infection treatments. Papers were exported as plain text. The process of retrieving and collecting data is depicted in Guidelines Flow Diagram.

2.2. Visualized analysis

The analysis and visualization of annual publishing patterns and rates were conducted using Graphpad prism v8.0.2. Furthermore, the data was analyzed and the scientific knowledge graph was shown using CtieSpace (6.2.4R [64-bit] Premium Edition) and VOSviewer (v.1.6.18). VOSviewer v.1.6.17, developed by Waltman et al in 2009, is a freely available software written in JAVA. It is designed for evaluating extensive collections of literary data and presenting it visually in the form of a map. Prof Chaomei Chen developed the CiteSpace (6.2.4R) software to visually represent the findings of research in a certain field by mapping the co-citation network of literature.[16] This software utilizes an experimental framework to investigate new ideas and assess current technology. This allows users to gain a deeper comprehension of many domains of knowledge, cutting-edge study fields, and emerging trends, as well as make informed predictions about their future research advancements.

3. Results

3.1. Trends in article publication and citations

Between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2023, the Web of Science Core Collection database includes a total of 3868 publications on wound infection care. These included 3327 articles and 541 reviews. The literature encompasses 117 countries and regions, 4673 institutions, and 20,161 writers.

Since 2004, there has been a gradual increase in the annual number of published papers (Fig. 1). This may be divided into 3 distinct phases. Firstly, there was a period of slow growth from 2004 to 2006, as shown in the figure. This suggests that the area was developing slowly during this time. Secondly, there was a gradual increase in the number of publications from 2007 to 2015. Finally, after 2016, there was a significant acceleration in the pace of publications in the field, reaching its peak in 2023.

Figure 1.

Annual volume of publications.

3.2. Analysis of communications from different countries

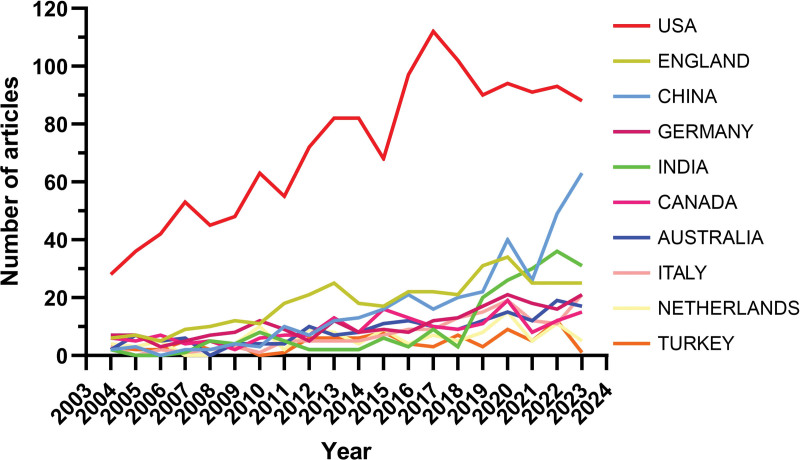

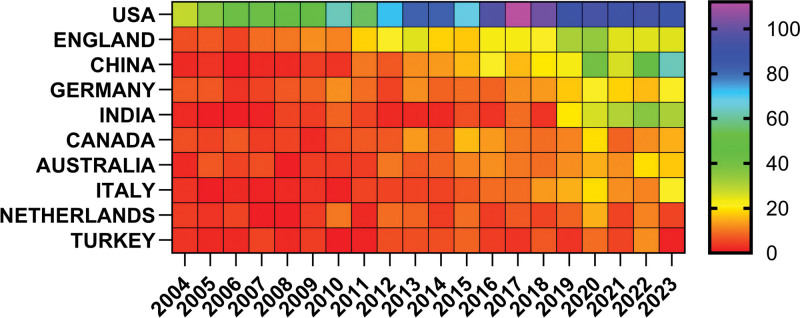

Analysis of messages from various countries. Studies on the utilization of wound infection care have been carried out in 117 nations and territories. Figures 2 and 3 display the yearly publishing volume of the leading 10 countries over the past decade. The top 5 countries in this domain are the United States, the United Kingdom, China, Germany, and India. The United States contributed 37.25% of the total number of publications, significantly surpassing all other countries, organizations, and establishments.

Figure 2.

Line graph of national publications.

Figure 3.

Heat map of national publications.

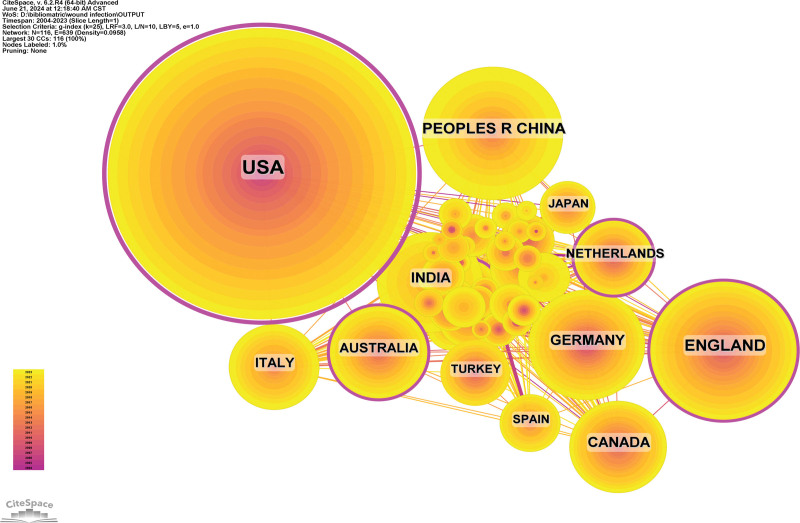

Out of the top 10 countries/regions in terms of the number of papers published, the United States stands out with 53,799 citations (Table 1), surpassing all other countries/regions. Additionally, its citation/publication ratio of 37.33 ranks 4th among all countries, suggesting that the overall quality of its published papers is high. The United Kingdom ranks second globally in terms of the number of publications, with a total of 364. It also holds the second position in terms of the number of citations, with a count of 14,542. Furthermore, the UK’s citation/publication ratio is very high, standing at 39.95. The collaboration network is depicted in Figure 4, illustrating the strong collaboration between the 2 most productive countries, the USA and the UK. The United States engages in tight collaboration with countries such as China, Italy, and Australia, while the United Kingdom engages in even closer collaboration with countries such as Canada, Japan, and Germany. The United States possesses a substantial quantity of publications and experiences a high frequency of citations. Additionally, it attains a centrality score of 0.61, signifying its current prominent position in this subject.

Table 1.

Table of country published literature.

| Rank | Country/region | Article counts | Centrality | Percentage (%) | Citation | Citation per publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | USA | 1441 | 0.61 | 37.25% | 53,799 | 37.33 |

| 2 | England | 364 | 0.14 | 9.41% | 14,542 | 39.95 |

| 3 | China | 331 | 0.02 | 8.56% | 7045 | 21.28 |

| 4 | Germany | 218 | 0.1 | 5.64% | 5063 | 23.22 |

| 5 | India | 195 | 0.01 | 5.04% | 2297 | 11.78 |

| 6 | Canada | 183 | 0.07 | 4.73% | 9673 | 52.86 |

| 7 | Australia | 174 | 0.12 | 4.50% | 5838 | 33.55 |

| 8 | Italy | 148 | 0.04 | 3.83% | 3431 | 23.18 |

| 9 | Netherlands | 118 | 0.14 | 3.05% | 5229 | 44.31 |

| 10 | Turkey | 89 | 0 | 2.30% | 1027 | 11.54 |

Figure 4.

Networks of country cooperation.

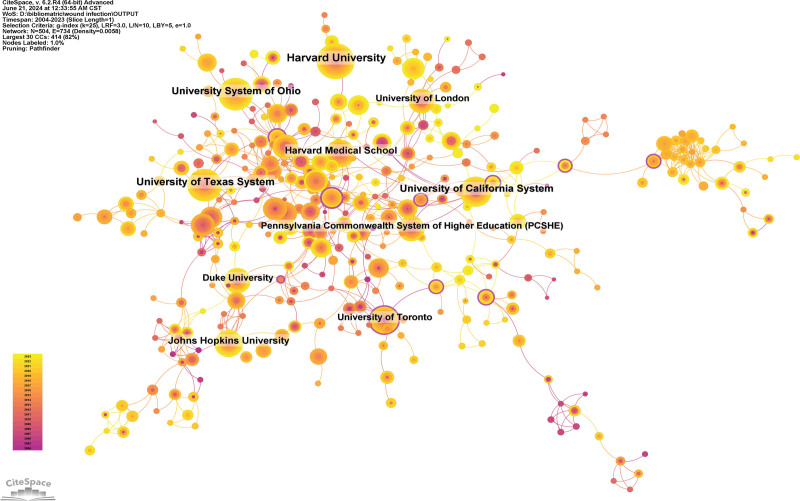

3.3. Analysis of article publishing organizations

A total of 4673 institutes consistently released literature pertaining to the management of wound infections. Among the top 10 institutions in terms of publications, 8 were affiliated with the United States, 1 with Canada, and 1 with the United Kingdom (as seen in Table 2 and Fig. 5). Harvard University has the highest number of published literature, with 118 publications and 8353 citations, resulting in an average of 70.79 citations per paper. The University of Texas System, with 91 publications and 3954 citations, had an average of 43.45 citations per paper, ranking second. The University System of Ohio, with 88 papers and 2857 citations, had an average of 32.47 citations per paper, ranking third. The University of California System, with 87 papers and 5567 citations, had an average of 63.99 citations per paper, ranking 4th. Upon conducting a more thorough examination, we have discovered that both domestic and foreign institutions exhibit a preference for collaborating with their respective domestic counterparts. Therefore, we advocate for enhancing cooperation between domestic and foreign institutions and dismantling any existing academic obstacles.

Table 2.

Table of institutional published literature.

| Rank | Institution | Country | Number of studies | Total citations | Average citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Harvard University | USA | 118 | 8353 | 70.79 |

| 2 | University of Texas System | USA | 91 | 3954 | 43.45 |

| 3 | University System of Ohio | USA | 88 | 2857 | 32.47 |

| 4 | University of California System | USA | 87 | 5567 | 63.99 |

| 5 | Johns Hopkins University | USA | 69 | 6316 | 91.54 |

| 6 | Harvard Medical School | USA | 69 | 6070 | 87.97 |

| 7 | University of Toronto | Canada | 55 | 2349 | 42.71 |

| 8 | Pennsylvania Commonwealth System of Higher Education (PCSHE) | USA | 54 | 2296 | 42.52 |

| 9 | University of London | England | 51 | 2009 | 39.39 |

| 10 | Duke University | USA | 51 | 5468 | 107.22 |

Figure 5.

Networks of institutional co-operation.

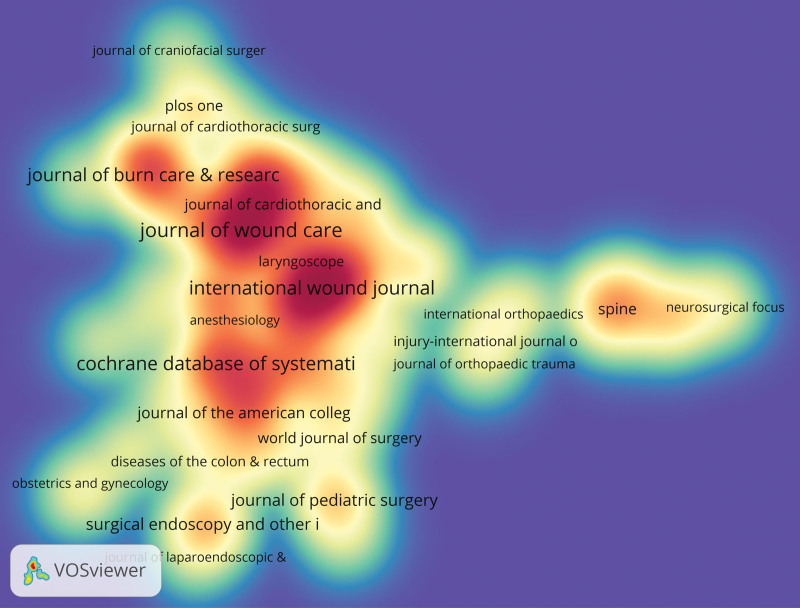

3.4. Analysis of publishing journals

Tables 3 and 4 contain a list of the top 10 journals that are both highly productive and often cited. The journal of wound care is the most prolific publication in the sector, with 85 papers accounting for 2.20% of the total. It is followed by the International wound journal, which has produced 71 articles (1.84%), the Cochrane database of systematic reviews with 67 articles (1.73%), and Surgical infections with 62 articles (1.60%) (Fig. 6). Out of the top ten most productive journals, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews had the highest impact factor of 88.4. Sixty percent of the journals were classified in the Q1 or Q2 regions.

Table 3.

Table of journal publications.

| Rank | Journal | Article counts | Percentage (3868) | IF | Quartile in category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Journal of Wound Care | 85 | 2.20% | 1.9 | Q3 |

| 2 | International Wound Journal | 71 | 1.84% | 3.1 | Q1 |

| 3 | Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | 67 | 1.73% | 8.4 | Q1 |

| 4 | Surgical Infections | 62 | 1.60% | 2.0 | Q3 |

| 5 | Cureus Journal of Medical Science | 59 | 1.53% | 1.2 | Q3 |

| 6 | Journal of Burn Care & Research | 56 | 1.45% | 1.4 | Q3 |

| 7 | Burns | 49 | 1.27% | 2.7 | Q2 |

| 8 | Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology | 45 | 1.16% | 4.5 | Q2 |

| 9 | Annals of Thoracic Surgery | 42 | 1.09% | 4.6 | Q2 |

| 10 | Journal of Pediatric Surgery | 39 | 1.01% | 2.4 | Q2 |

IF = impact factor.

Table 4.

Co-citation table of journals.

| Rank | Cited journal | Co-citation | IF (2022) | Quartile in category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | New Engl J Med | 1200 | 158.5 | Q1 |

| 2 | Ann Surg | 1103 | 10.1 | Q1 |

| 3 | Infect Cont Hosp Ep | 997 | 4.5 | Q2 |

| 4 | Lancet | 941 | 168.9 | Q1 |

| 5 | Am J Infect Control | 887 | 4.9 | Q1 |

| 6 | Jama-J Am Med Assoc | 881 | 120.7 | Q1 |

| 7 | J Hosp Infect | 831 | 6.9 | Q1 |

| 8 | Clin Infect Dis | 794 | 11.8 | Q1 |

| 9 | Arch Surg-Chicago | 749 | 5.1 | Q1 |

| 10 | Am J Surg | 689 | 3.0 | Q2 |

IF = impact factor.

Figure 6.

Density map of journal publications.

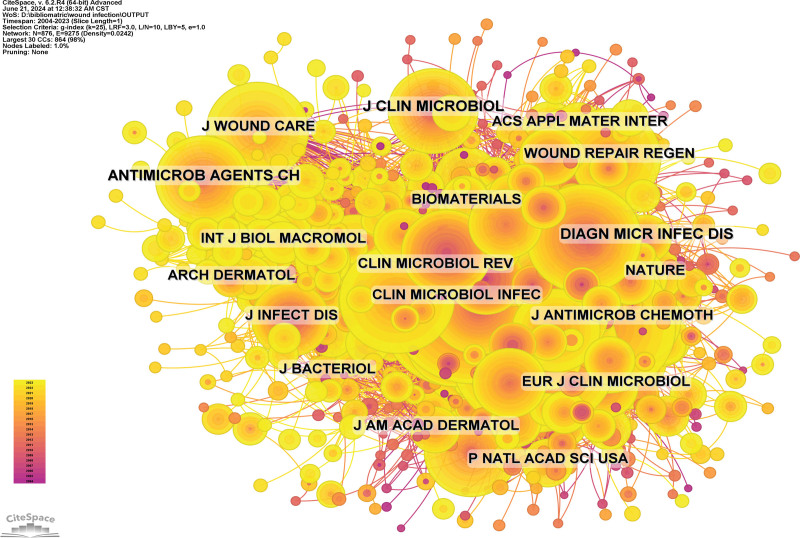

Journal impact is assessed based on the frequency of co-citations, which reflects the extent to which the journal has influenced the scientific community. Based on the data presented in Figure 7 and Table 4, the journal with the greatest number of co-citations is New Engl J Med, with a count of 1200. Following closely after are Ann Surg with 1103 co-citations and Infect Cont Hosp Ep with 997 co-citations. Out of the top 10 most often referenced journals, Lancet received 941 citations, which is the greatest impact factor among the top 10 journals (1168.9). All of the journals that were co-cited were located in the Q1/Q2 region.

Figure 7.

Co-citation network map of journals.

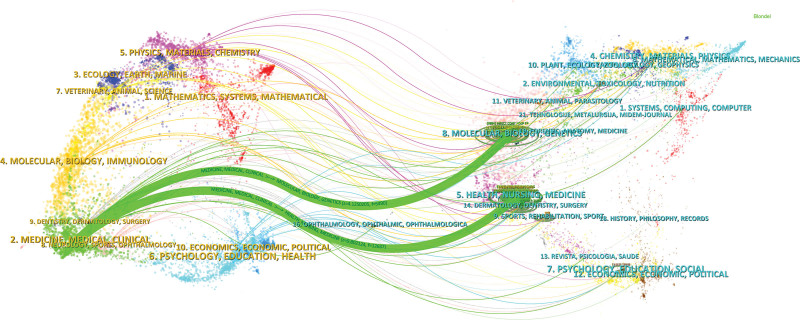

The distribution of scholarly publications according to themes is depicted using a double map overlay (Fig. 8). The tracks that are colored represent citation links, with the journals that are doing the citing on the left and the journals that are being cited on the right. From the results shown, we have observed 2 primary citation patterns. Specifically, studies published in molecular/biology/genetics journals were predominantly cited by studies published in molecular/biology/immunology journals. On the other hand, studies published in health/nursing/medicine journals were mainly cited by studies published in molecular/biology/immunology journals.

Figure 8.

Dual map of journals.

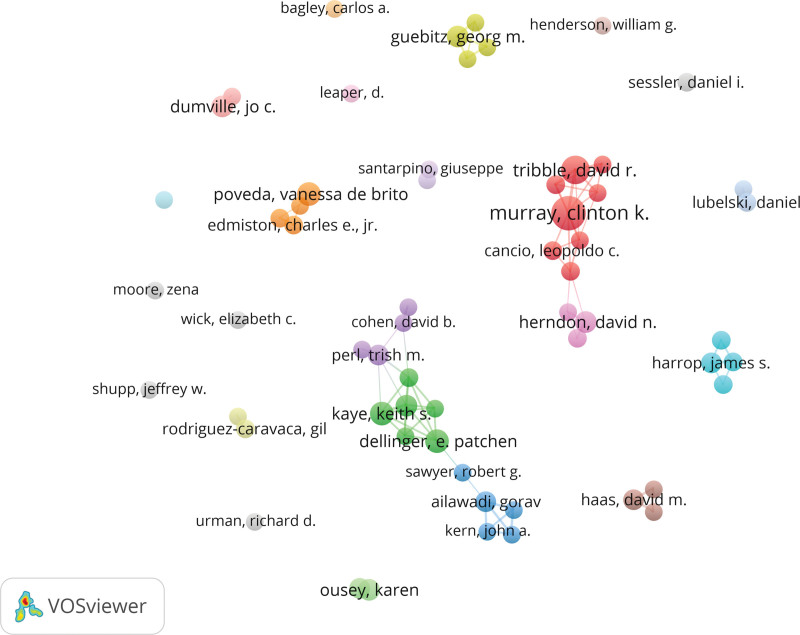

3.5. Authors and co-cited authors

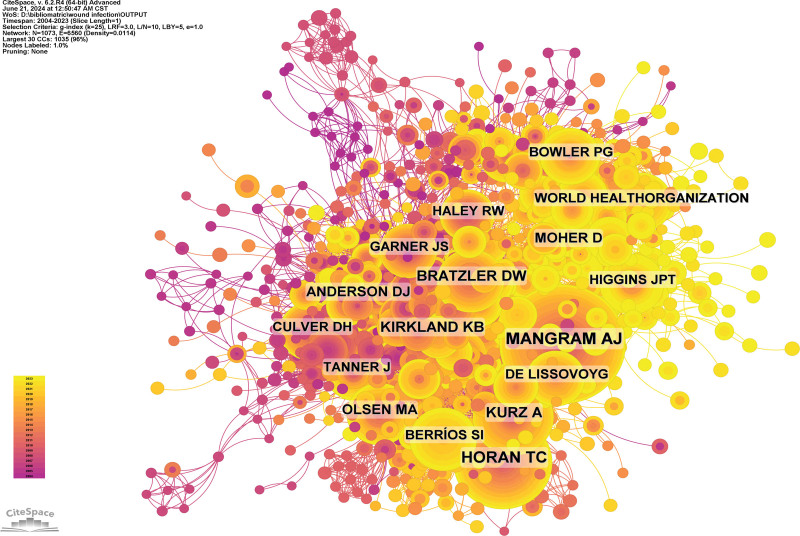

Table 5 is a compilation of the top 10 writers who have published the most number of papers on wound infection management among all the authors who have contributed relevant literature. The collective output of the top 10 writers amounted to 99 papers, accounting for a mere 2.56% of the entire body of papers in the area. Murray, Clinton K. has the most number of published research papers with 19, followed by Tribble, David R. with 13 papers, Dellinger, E. Patchen with 9 papers, Kaye, Keith S. with 9 papers, and Poveda, Vanessa de Brito with 9 articles. CiteSpace provides a visual representation of the network connecting writers (Fig. 9).

Table 5.

Author’s publications and co-citation table.

| Rank | Author | Count | Rank | Co-cited author | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Murray, Clinton K. | 19 | 1 | Mangram Aj | 392 |

| 2 | Tribble, David R. | 13 | 2 | Horan Tc | 284 |

| 3 | Dellinger, E. Patchen | 9 | 3 | Kurz A | 173 |

| 4 | Kaye, Keith S. | 9 | 4 | Bratzler Dw | 158 |

| 5 | Poveda, Vanessa De Brito | 9 | 5 | Kirkland Kb | 155 |

| 6 | Anderson, Deverick J. | 8 | 6 | Anderson Dj | 143 |

| 7 | Dumville, Jo C. | 8 | 7 | Moher D | 131 |

| 8 | Guebitz, Georg M. | 8 | 8 | Olsen Ma | 122 |

| 9 | Herndon, David N. | 8 | 9 | Berríos Si | 113 |

| 10 | Ousey, Karen | 8 | 10 | Haley Rw | 110 |

Figure 9.

Cooperation network of authors.

Figure 10 displays the top 10 authors who are most frequently quoted together, while Table 5 presents the top 10 authors who are cited the most. A total of 80 writers were mentioned more than 50 times, demonstrating the significant reputation and importance of their study. The largest nodes correspond to the writers with the highest number of co-citations, namely MANGRAM AJ (392 citations), HORAN TC (284 citations), and KURZ A (1173 citations).

Figure 10.

Co-citation network of authors.

3.6. Periodicals and co-cited periodicals

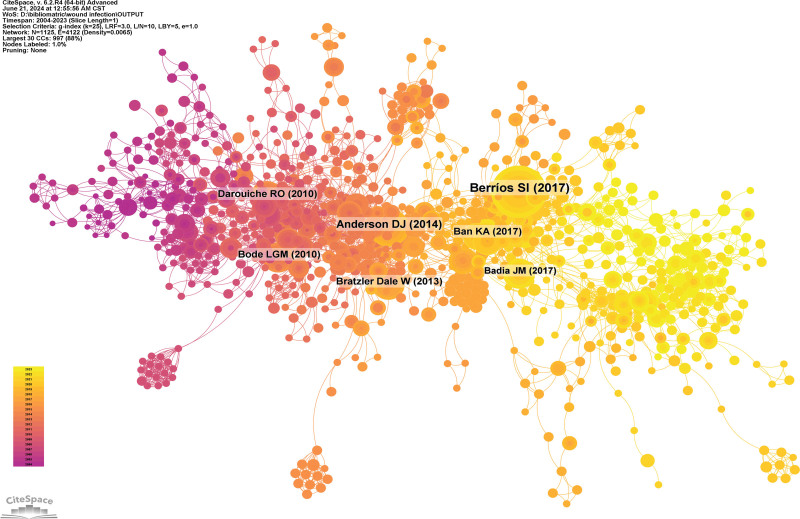

From 2004 to 2023, the co-cited reference network consisted of 1125 nodes and 4122 linkages (Fig. 11). The article titled “Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 2017” authored by Sandra I. Berrios is among the top 10 most co-cited publications in Journal of the American Medical Association Surgery Care, as shown in Table 6. The article’s findings indicate that the expenses associated with managing surgical site infections (SSIs) are consistently rising, both in terms of human impact and economic burden. The United States is experiencing an increase in the number of surgical procedures, and the initial difficulties in surgical patients are growing more intricate. Between 1998 and April 2014, we performed a focused and methodical examination of relevant literature in MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library. The quality of the evidence and the robustness of the final recommendations were assessed using a modified Grading of Recommendations, Assessments, Developments, and Evaluations technique. This approach also helped make obvious connections between the evidence and the recommendations. Out of the 5759 titles and abstracts that were examined, 896 were thoroughly assessed by 2 separate reviewers. Before undergoing surgery, patients should cleanse their entire body by showering or bathing with either antimicrobial or non-antimicrobial soap or disinfectant, at least on the evening prior to the scheduled surgery day. Antimicrobial prophylaxis should only be used when following established clinical practice guidelines and should be given to ensure that effective levels of antibiotics are present in the bloodstream and tissue at the time of making an incision. Prior to making an incision in the skin during a cesarean section, it is important to administer antibacterial prophylaxis. Alcohol-based treatments should be used to prepare the skin in the operating room, unless there is a reason not to do so. It is not necessary to administer more doses of preventive antimicrobial drugs in the operating room after the surgical incision has been closed, even if drains are present, for procedures that are considered clean or clean-contaminated. It is not recommended to apply topical antimicrobials on surgical incisions. During surgical procedures, it is important to regulate blood glucose levels to a goal level below 200 mg/dL and ensure that the patient’s body temperature remains within the normal range. For patients with normal lung function undergoing general anesthesia with tracheal intubation, it is recommended to increase the amount of breathed oxygen during surgery and soon after extubation following the operation. Refusing to provide surgical patients with blood product transfusions should not be employed as a method of preventing SSIs. This guideline aims to offer new and updated evidence-based guidelines for preventing SSIs. It should be included into a complete surgical quality improvement program to enhance patient safety.

Figure 11.

Co-cited network of literature.

Table 6.

Co-citation table of literature.

| Rank | Title | Journal | Author(s) | Total citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Centers for disease control and prevention guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 2017 | JAMA Surgery | Berrios, Sandra I. | 94 |

| 2 | Strategies to prevent surgical site infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update | Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology | Anderson DJ | 61 |

| 3 | Chlorhexidine–alcohol vs povidone–iodine for surgical-site antisepsis | New England Journal of Medicine | Darouiche RO | 39 |

| 4 | American college of surgeons and surgical infection society: surgical site infection guidelines, 2016 update | Journal of the American College of Surgeons | Ban KA | 37 |

| 5 | Preventing surgical-site infections in nasal carriers of Staphylococcus aureus | New England Journal of Medicine | Bode LGM | 34 |

| 6 | Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery | American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy | Bratzler Dale W | 34 |

| 7 | Impact of surgical site infection on healthcare costs and patient outcomes: a systematic review in 6 European countries | Journal of Hospital Infection | Badia JM | 33 |

| 8 | New WHO recommendations on preoperative measures for surgical site infection prevention: an evidence-based global perspective | Lancet Infectious Diseases | Allegranzi Benedetta | 29 |

| 9 | Multistate point–prevalence survey of health care—associated infections | New England Journal of Medicine | Magill SS | 25 |

| 10 | Adherence to surgical care improvement project measures and the association with postoperative infections | Jama—Journal of the American Medical Association | Stulberg JJ | 22 |

The article titled “Strategies to Prevent Surgical Site Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 Update” by Anderson, Deverick J. is ranked as the second best. The essay contends that existing standards offer thorough suggestions for identifying and averting healthcare-associated infections. This publication aims to present practical guidelines in a brief way to assist acute care hospitals in implementing and prioritizing initiatives to avoid SSIs. This paper provides an updated version of the Surgical Site Infection Prevention Strategies for Acute Care Hospitals that was originally published in 2008.

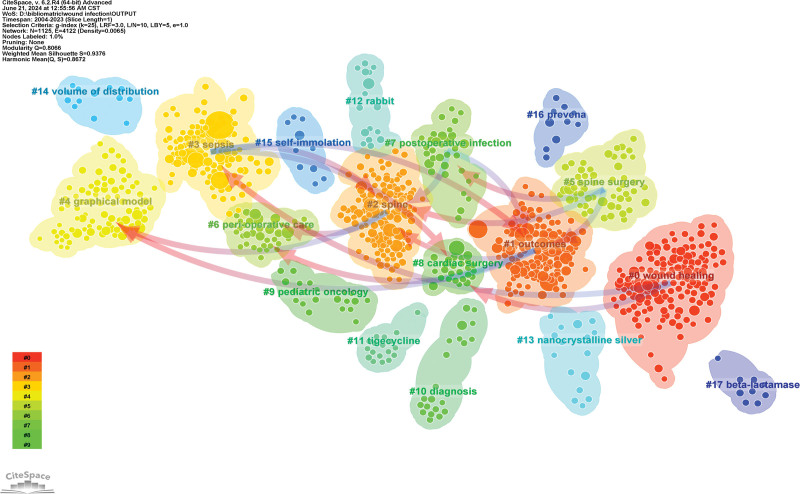

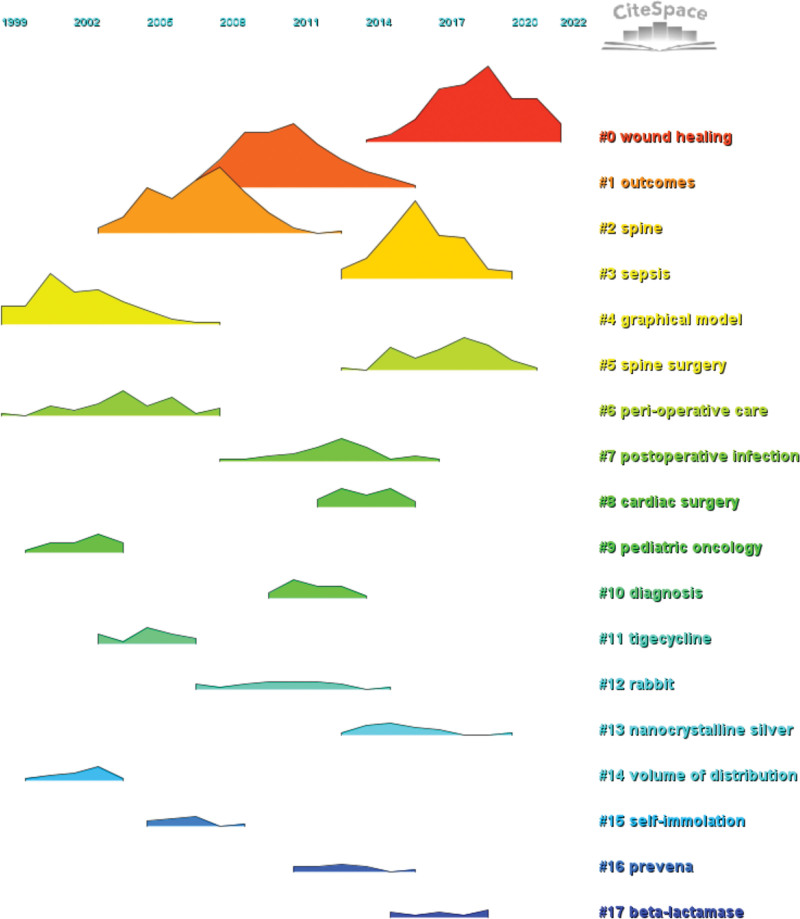

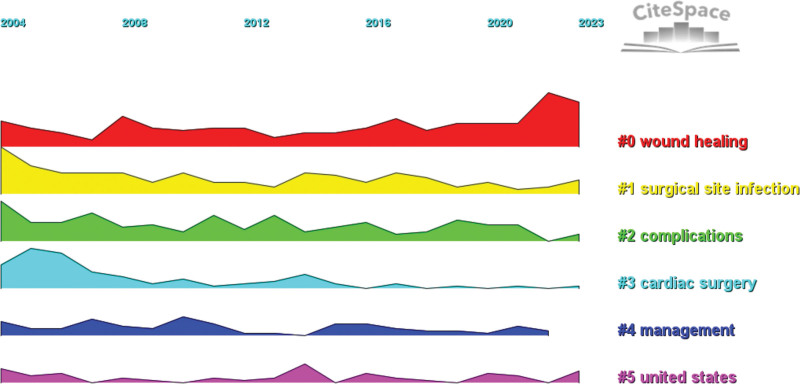

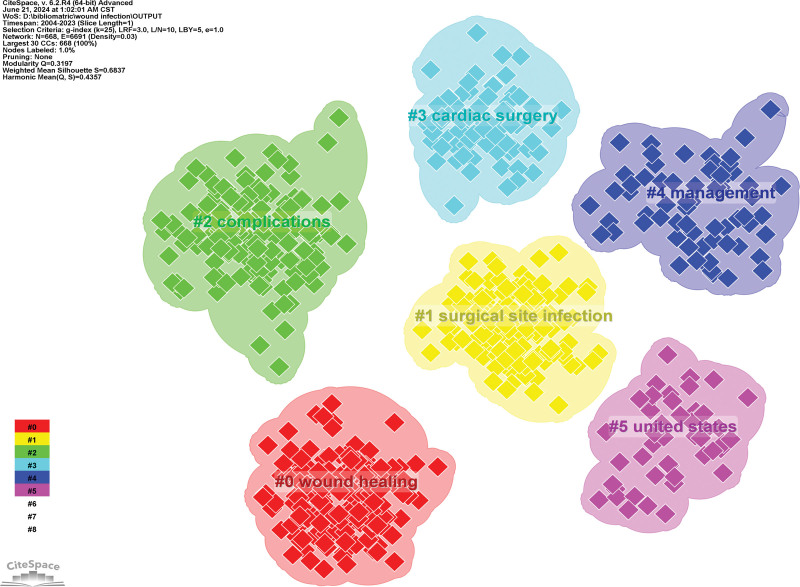

We conducted co-citation reference clustering and temporal clustering analysis, as shown in Figures 12 and 13. Our investigation revealed that graphical model (cluster4), peri-operative care (cluster6), pediatric oncology (cluster8), and volume of distribution (cluster14) emerged as prominent areas of early research interest. The mid-term research hotspots include outcome (cluster1), spine (cluster2), cardiac surgery (cluster8), diagnostic (cluster10), tigecycline (cluster11), rabbit (cluster12), self-immolation (cluster15), and prevena (cluster16). Wound healing (cluster0), sepsis (cluster3), spine surgery (cluster5), postoperative infection (cluster7), nanocrystalline silver (cluster13), and beta lactamase (cluster17) are currently popular and emerging subjects in the discipline.

Figure 12.

Clustering of co-cited literature.

Figure 13.

Peak map of co-cited literature.

3.7. Analysis of keywords of the publications

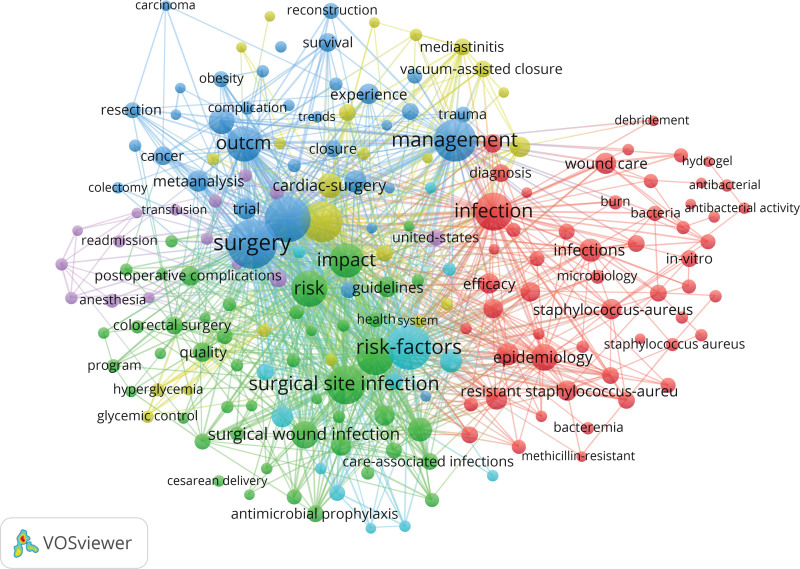

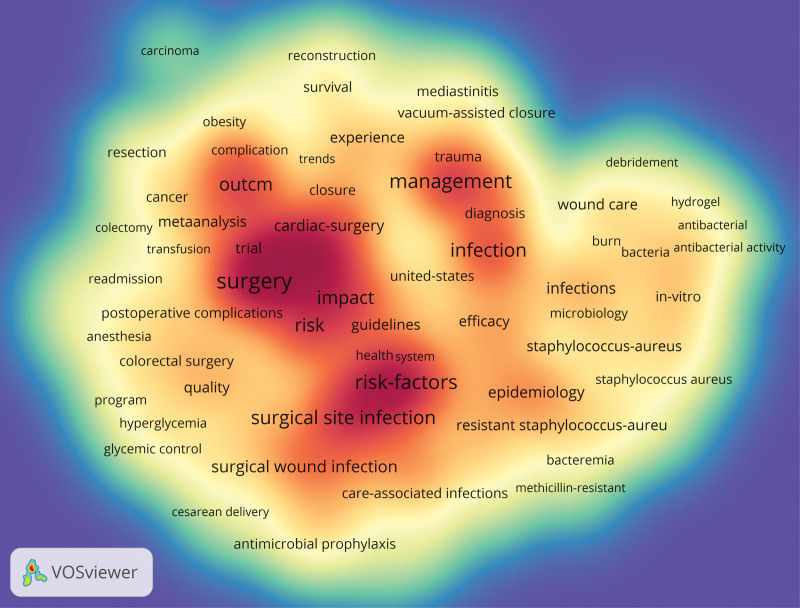

Through the analysis of keywords, we can swiftly obtain a concise summary of a certain field and its trajectory. Based on the co-occurrence of terms in VOSviewer, the keyword “surgery” was the most frequently used (570 occurrences), followed by “complications” (498 occurrences), “risk-factors” (458 occurrences), “management” (416 occurrences), and “mortality” (391 occurrences) (Table 7, Figs. 14 and 15). We eliminated irrelevant keywords and created a network consisting of 187 keywords that appeared at least 27 times. This resulted in a total of 6 distinct clusters. Cluster 1 (red) consisted of 54 keywords, such as efficacy, burns, skin, infection, delivery, sepsis, mrsa, bacteria, biofilms, wound care, antibacterial, antimicrobial, chronic wounds, colonization, diagnosis, dressing, epidemiology, hydrogel, injury, intensive care unit, model, nanoparticles, nursing, pneumonia. Group 2 (green) consists of 47 keywords, such as preventive, surgical site infection, guidelines, risk, impact, prophylaxis, surveillance, surgical wound infection, adverse events, colon, cost, health, human, implementation, index, meta-analysis, program, reduce, and strategy. Group 3 consists of 45 keywords, highlighted in blue, such as surgery, complication, outcome, morbidity, management, closure, infants, body mass index, appendicitis, cancer, follow up, head, multicenter, obesity, repair, pain, and trends. Group 4 consists of 23 keywords, highlighted in yellow, which include cardiac surgery, glucose control, hyperglycemia, mortality, mediastinitis, randomized trial, revascularization, society, sternal wound infection, and sternotomy. Group 5 consists of 15 keywords, specifically anesthesia, arthroplasty, association, blood loss, hip, normothermia, outcomes, predictors, readmission, replacement, temperature, and transfusion. The keywords are denoted by the letter ‘z’ followed by the color purple. Group 6 consists of 13 terms, specifically “sky blue,” which include categorization, cost, fusion, instrument, operation, patient, rate, risk factor, spine, and vancomycin. We generated a Peak map using CiteSpace software to visually represent the areas of intense research activity over time. We plotted Peak maps and clustering maps through CiteSpace to visualize the research hotspots over time (Figs. 16 and 17).

Table 7.

High frequency keyword table.

| Rank | Keyword | Counts | Rank | Keyword | Counts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Surgery | 570 | 11 | Impact | 287 |

| 2 | Complications | 498 | 12 | Surgical wound infection | 176 |

| 3 | Risk-factors | 458 | 13 | Epidemiology | 166 |

| 4 | Management | 416 | 14 | Morbidity | 161 |

| 5 | Mortality | 391 | 15 | Cardiac-surgery | 145 |

| 6 | Surgical site infection | 356 | 16 | Surveillance | 139 |

| 7 | Infection | 338 | 17 | Infections | 129 |

| 8 | Prevention | 333 | 18 | Children | 118 |

| 9 | Risk | 313 | 19 | Surgical site infections | 115 |

| 10 | Outcome | 298 | 20 | Prevalence | 114 |

Figure 14.

Network map of high-frequency keywords.

Figure 15.

Density map of keywords.

Figure 16.

Peak map of keyword clustering.

Figure 17.

Clustering map of keywords.

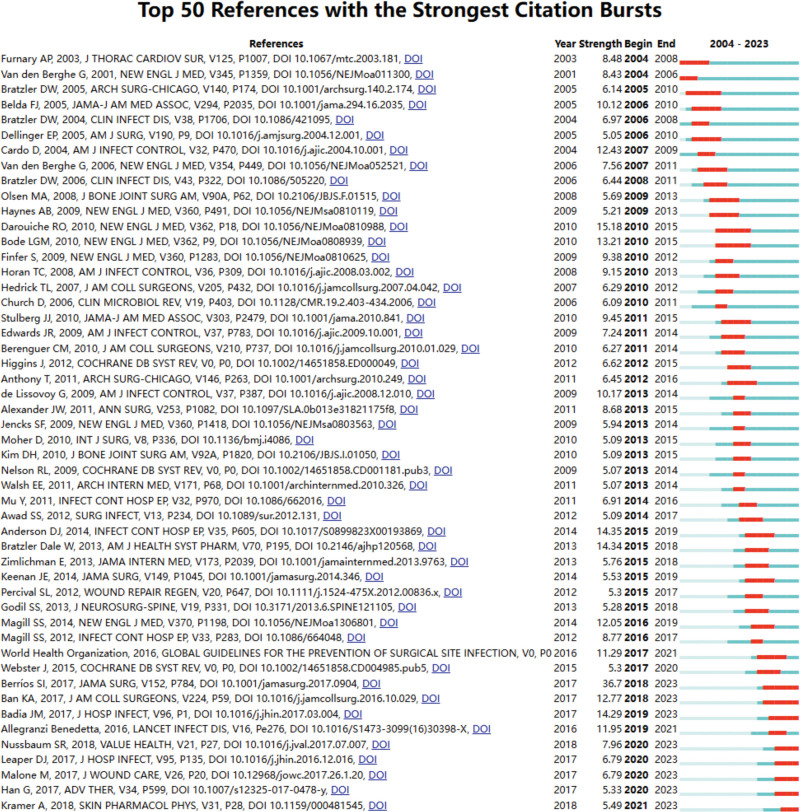

3.8. Co-cited references and keywords

By utilizing CiteSpace, we have identified the top 50 citation bursts that are highly dependable in the field of wound infection care. The reference that is frequently mentioned was published in The New England Journal of Medicine under the title “Chlorhexidine–alcohol versus povidone–iodine for surgical-site antisepsis.” The article, authored by Rabih O. Darouiche, presents the argument that enhancing preoperative skin antisepsis can potentially decrease postoperative infections. This is because the patient’s skin is the primary reservoir of pathogens responsible for surgical site infections. Our hypothesis was that preoperative skin cleaning using chlorhexidine–alcohol would be superior in preventing infection compared to skin scouring with povidone–iodine. Adults having clean-contamination procedures at 6 hospitals were randomly allocated to receive either chlorhexidine–alcohol or povidone–iodine skin scrubbing and painting before their operation. The main result measured was the occurrence of any infection at the surgical site within a 30-day period following the surgery. The intention-to-treat analysis included a total of 849 participants, with 409 in the chlorhexidine-alcohol group and 440 in the povidone–iodine group. The incidence of surgical site infections was markedly lower in the chlorhexidine–alcohol group compared to the povidone–iodine group (9.5% vs 16.1%; P = .004; relative risk 0.59; 95% confidence interval 0.41–0.85). Chlorhexidine–alcohol was shown to be considerably more effective than povidone–iodine in preventing superficial incision infections (4.2% vs 8.6%; P = .008) and deep incision infections (1% vs 3%; P = .05). However, there was no significant difference between the 2 in preventing interstitial organ infections (4.4% vs 4.5%). Consistent findings were noted in a per-protocol analysis of 813 participants who completed the research and were followed up for 30 days. Preoperative skin cleansing using chlorhexidine–alcohol was found to be more efficacious than povidone–iodine in avoiding surgical site infections following procedures involving contaminated cleansing. Out of the total of 50 references, 48 were published within the time frame of 2004 to 2023. This suggests that these articles have received significant citations during the past 2 decades. Significantly, 8 of these studies are presently experiencing high citation rates (Fig. 18), indicating that wound infection care will be a subject of interest in the future.

Figure 18.

Bursting map of cited literature.

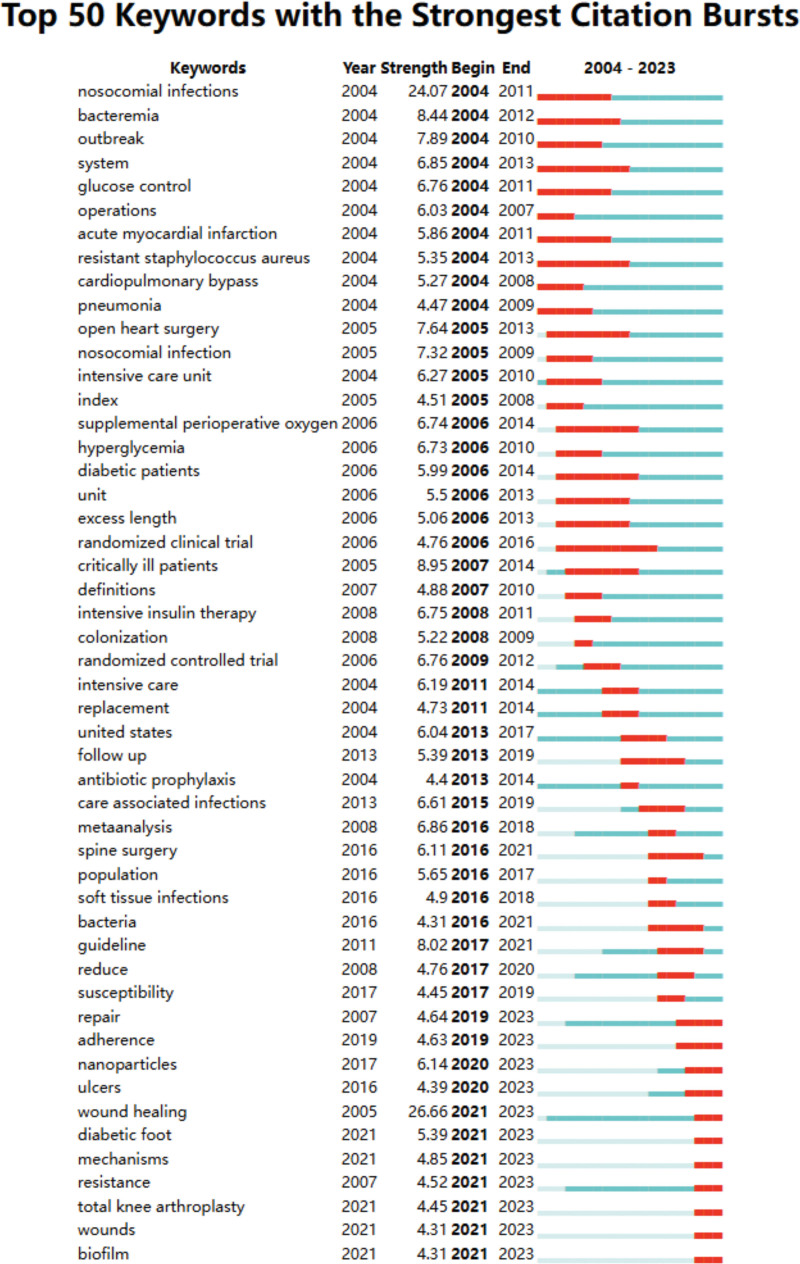

Out of the 576 most powerful mutated terms in the field, our attention was directed towards the 50 keywords with the most significant mutations (Fig. 19). These keywords not only indicate current areas of intense research but also suggest potential routes for future research.

Figure 19.

Bursting map of keywords.

4. Discussion

4.1. Current status of research on infected wounds

Current studies on infected wounds concentrate on the development of sophisticated medication delivery methods and alternate treatments to address the issue of antibiotic resistance. Novel strategies including bacteriophage therapy,[17] antimicrobial peptides, cold plasma treatment, and photodynamic therapy.[18] Antibacterial wound dressings that include natural substances such as essential oils and honey have potential, as indicated by Neguț et al[19] Researchers are now investigating the antibacterial qualities and effectiveness in wound healing of nanoparticles and hydrogels, namely those based on chitosan.[20,21] Probiotics have shown promise in preventing the development of microorganisms and the creation of biofilms in long-lasting wounds.[22] These innovative approaches are designed to address difficulties such as hostile wound conditions, long-lasting nature of the wounds, and the development of biofilms.[23] Although initial data suggests the potential of these alternatives, more research and extensive clinical trials are required to validate their efficacy in the treatment of infected wounds.[24] This study presents a bibliometric analysis of research pertaining to infected wound care, aiming to examine the focal points and trends of contemporary research advancements and to offer a valuable reference for practitioners in related disciplines. The analysis of this study indicated that the primary keywords in wound healing research predominantly included: sepsis, spinal surgery, postoperative infections, nanocrystalline silver, and β-lactamase, suggesting that enhancing wound care and treatment to facilitate healing and minimize complications is a significant research focus.

4.2. The critical role of nursing in promoting infected wound repair

Nursing is crucial in facilitating the healing of infected wounds through a range of therapies. In order to provide evidence-based treatment, nurses must possess a comprehensive understanding of wound healing physiology, be able to differentiate between inflammation and infection, and be able to identify biofilms.[25] Wound infections may result in delayed wound healing, the development of chronic conditions, and higher healthcare expenses.[4] Chronic wound development is substantially affected by the existence of harmful bacteria and biofilms.[26] According to Dutton et al,[27] wound care nurses have the ability to enhance healing periods and reduce the occurrence of pressure injuries. The innate immune system plays a vital role in the process of wound healing, with a closely controlled transition from inflammatory to reparative processes.[28] Effective wound-bed preparation, which involves the removal of dead tissue and the use of topical antiseptics, is crucial for the treatment of infections and the facilitation of the healing process.[29] In order to provide successful treatment for infected wounds, nurses must be knowledgeable about advanced procedures such as vacuum therapy.

4.3. Progress in the treatment of infected wounds

Optimizing wound healing therapy methods can significantly improve healing outcomes. Primarily, debridement, dressing alteration, and antibiotic administration are essential components of the conventional wound care methodology.[1] Secondly, advancements in biotechnology provide renewed optimism for wound healing. The utilization of growth factors and cytokines is regarded as a significant method for enhancing wound healing. The local or systemic use of these bioactive compounds can substantially expedite the wound healing process.[30] Thirdly, gene therapy offers innovative approaches for wound healing. Genetic engineering technique enables the introduction of certain genes into cells at the wound site, therefore influencing cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration, which further enhances wound healing.[31] Fourthly, the advancement of nanotechnology and intelligent materials presents novel prospects for wound healing. Nanomaterials exhibit significant potential in this domain owing to their distinctive physical and chemical characteristics. For instance, nanofiber scaffolds can replicate the architecture of the extracellular matrix, thereby creating an optimal environment for cellular proliferation and enhancing wound healing. Conversely, smart dressings possess the capability to monitor wound healing status in real time and administer medications as required, further refining the healing process.[32] In conclusion, advancements in research on wound healing therapies have yielded substantial development, with the use of diverse novel technologies and methodologies offering enhanced possibilities for clinical therapy. In the future, the ongoing advancement of science and technology will further enhance studies on wound healing, yielding more advantages for patients.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

The literature on infected wound care examined in this study was obtained from the Web of Science database, specifically the Science Citation Index Expanded Journals. The analysis covered the period from 2004 to 2023, ensuring a thorough and unbiased assessment. However, our inclusion criteria limited the survey to publications in English, potentially leading to the omission of relevant non-English studies from the database and analyses. All searches were conducted within a single day to prevent any bias caused by database updates. We recommend that future research investigate the citation frequency of recent publications and consider including studies in languages other than English.

Author contributions

Visualization: Zheng Wang.

Writing – original draft: Mengdi Liu, Cuifang Ma, Xiaowei Dong, Mengyi Gu, Zheng Wang.

Writing – review & editing: Qian Gao, Xiaoyu Guo.

Abbreviation:

- SSIs

- surgical site infections

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

How to cite this article: Liu M, Ma C, Dong X, Gu M, Wang Z, Gao Q, Guo X. Nursing bibliometric analysis of wound infections. Medicine 2024;103:43(e40256).

Contributor Information

Cuifang Ma, Email: macuifang0518@163.com.

Xiaowei Dong, Email: dxw661@163.com.

Mengyi Gu, Email: 13953439905@163.com.

Zheng Wang, Email: zhengyimingdao@gmail.com.

Qian Gao, Email: sygaoqian@126.com.

Xiaoyu Guo, Email: zcguoli@163.com.

References

- [1].Williams M. Wound infections: an overview. Br J Community Nurs. 2021;26:S22–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cefalu JE, Barrier KM, Davis AH. Wound infections in critical care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2017;29:81–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rutter L. Identifying and managing wound infection in the community. Br J Community Nurs. 2018;23:S6–S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sandoz H. An overview of the prevention and management of wound infection. Nurs Stand. 2022;37:75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Johnson AC, Buchanan EP, Khechoyan DY. Wound infection: a review of qualitative and quantitative assessment modalities. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2022;75:1287–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ding S, Lin F, Marshall AP, Gillespie BM. Nurses’ practice in preventing postoperative wound infections: an observational study. J Wound Care. 2017;26:28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zakhary SA, Davey C, Bari R, et al. The development and content validation of a multidisciplinary, evidence-based wound infection prevention and treatment guideline. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2017;63:18–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fukuta Y, Chua H, Phe K, Poythress EL, Brown CA. Infectious diseases management in wound care settings: common causative organisms and frequently prescribed antibiotics. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2022;35:535–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Li P, Tong X, Wang T, et al. Biofilms in wound healing: a bibliometric and visualised study. Int Wound J. 2023;20:313–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Shen S, Zhang Y, Zhang Q, Xiao K, Tang J. Periprosthetic joint infection after total knee arthroplasty: a bibliometrics analysis. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:9927–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Farhat F, Sohail SS, Siddiqui F, Irshad RR, Madsen DO. Curcumin in wound healing-a bibliometric analysis. Life (Basel). 2023;13:143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Liu R, Zhai L, Feng S, Gao R, Zheng J. Research frontiers and hotspots in bacterial biofilm wound therapy: bibliometric and visual analysis for 2012-2022. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023;85:5538–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tang NFR, Heryanto H, Armynah B, Tahir D. Bibliometric analysis of the use of calcium alginate for wound dressing applications: a review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;228:138–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gürler M, Alkan S, Özlü C, Aydin B. Diyabetik Ayak Enfeksiyonu İle İlgili Yayinlarin İşbirliğine Dayali Ağ Analizi ve Bibliyometrik Analizi. J Biotechnol Strateg Health Res. 2021;5:194–9. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Li C, Ojeda-Thies C, Renz N, Margaryan D, Perka C, Trampuz A. The global state of clinical research and trends in periprosthetic joint infection: a bibliometric analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96:696–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jin B, Wu XA, Du SD. Top 100 most frequently cited papers in liver cancer: a bibliometric analysis. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90:21–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chang R, Morales S, Okamoto Y, Chan H. Topical application of bacteriophages for treatment of wound infections. Transl Res J Lab Clin Med. 2020;220:153–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Karinja SJ, Spector JA. Treatment of infected wounds in the age of antimicrobial resistance: contemporary alternative therapeutic options. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142:1082–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Negut I, Grumezescu V, Grumezescu AM. Treatment strategies for infected wounds. Molecules. 2018;23:2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang X, Song R, Johnson M, et al. Chitosan-based hydrogels for infected wound treatment. Macromol Biosci. 2023;23:e2300094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zu X, Han Y, Zhou W, Huangfu C, Zhang M, Han Y. Research progress of antibacterial hydrogel in treatment of infected wounds. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2024;38:249–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Brognara L, Salmaso L, Mazzotti A, Di Martino A, Faldini C, Cauli O. Effects of probiotics in the management of infected chronic wounds: from cell culture to human studies. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2020;15:193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kaiser P, Wächter J, Windbergs M. Therapy of infected wounds: overcoming clinical challenges by advanced drug delivery systems. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2021;11:1545–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mirhaj M, Labbaf S, Tavakoli M, Seifalian A. An overview on the recent advances in the treatment of infected wounds: antibacterial wound dressings. Macromol Biosci. 2022;22:e2200014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Woldegioris T, Bantie G, Getachew H. Nurses’ knowledge and practice regarding prevention of surgical site infection in Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. Surg Infect. 2019;20:71–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hussain MA, Huygens F. Role of infection in wound healing. Bangladesh J Med Sci. 2020;19:598–602. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dutton M, Chiarella M, Curtis K. The role of the wound care nurse: an integrative review. Br J Community Nurs. 2014;19:S39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].MacLeod AS, Mansbridge JN. The innate immune system in acute and chronic wounds. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2016;5:65–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Barrett S. Wound-bed preparation: a vital step in the healing process. Br J Nurs. 2017;26:S24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Legrand J, Martino MM. Growth factor and cytokine delivery systems for wound healing. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2022;14:a041234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zomer HD, Trentin AG. Skin wound healing in humans and mice: challenges in translational research. J Dermatol Sci. 2018;90:3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bhattacharya D, Ghosh B, Mukhopadhyay M. Development of nanotechnology for advancement and application in wound healing: a review. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2019;13:778–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]