Although herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) is regarded as causing most cases of genital herpes, preliminary reports suggest that the type 1 virus (HSV-1) is increasingly the cause of infection.1 Recurrence rates, viral shedding, and the mode of acquiring HSV-1 infection are different from those for HSV-2, so counselling and clinical management strategies may need to be revised. We studied longitudinal trends in laboratory reports of genital HSV-1 infection.

Methods and results

The West of Scotland Specialist Virology Centre processes 99% of all herpes simplex virus culture samples in the region. All genital samples of herpes simplex processed between 1 January 1986 and 31 December 2000 were reviewed for source of referral, patient's sex and age (stratified into seven bands: ⩽20, 21-25, 26-30, 31-35, 36-40, 41-45, and >45 years), and the type of virus isolated.

Samples were cultured and then typed using fluorescein labelled monoclonal antibodies to HSV-1 and HSV-2 (Syva Microtrak). From January 1999, the virus was detected and typed using a polymerase chain reaction method and restriction fragment length polymorphism.2 The referral patterns and age and sex profiles of patients did not change during the period of analysis.

We compared the proportion of HSV-1 in all positive swabs between sexes and ages using χ2 tests, and over the three year time bands by the Cochran Armitage trend test (both overall and within four subgroups with age categorised as ⩽25 years or >25 years for each sex) using SAS 8.2.

Of 10 547 swabs, the virus was identified in 3181 (30%); 3126 were typed, 1530 (49%) as HSV-1 and 1596 (51%) as HSV-2. Of the swabs testing positive for HSV, 2004 (63%) were from women and 1177 (37%) were from men. Age was recorded for 3099 (97.4%) patients, with 555 (18%) aged ⩽20, 885 (29%) aged 21-25, 686 (22%) aged 26-30, 413 (13%) aged 31-35, 239 (8%) aged 36-40, 159 (5%) aged 41-45, and 162 (5%) aged >45 years. The origin of the request to detect the virus was recorded for 10 476 (99%) samples: 7579 (72%) were from genitourinary medicine clinics, 678 (6%) from general practice, 223 (2%) from family planning clinics, and 1996 (19%) from other sources.

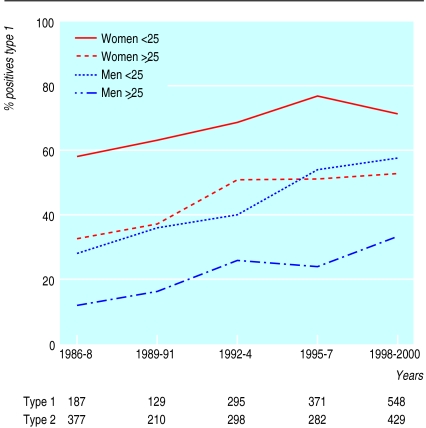

HSV-1 was strongly associated with female sex and younger age (P<0.0001). Over the entire study period, HSV-1 was found in 751 (70%) of all positive swabs in women <25 years, 141 (41%) in men <25 years, 413 (49%) in women ⩾25 years, and 182 (23%) in men ⩾25 years.

In 1986-8, 33% (187) of all positive swabs were due to HSV-1, rising progressively to 56% (548) in 1998-2000 (P<0.0001). A significant rise (P<0.0001, 1986 v 2000) in the proportion of isolates attributable to HSV-1 occurred in each of the four age and sex subgroups (P<0.0001) (figure).

Comment

Both the number and percentage of genital HSV-1 infections have risen. Genital infection with HSV-1 is strongly associated with being young (aged <25 years) and being female.

Explanations include changing host susceptibility and changing sexual behaviour of the population. The population seroprevalence of HSV-1 is falling: increasing numbers of young adults are susceptible to HSV-1 infection.3 As genital tract reactivation of latent HSV-1 infection is infrequent, most new cases of genital HSV-1 infection are likely to be due to orogenital transmission, but there is no evidence suggesting that oral sex practices have changed substantially.4 The occurrence of HSV-1 infection in women, seen consistently in other studies,1 is unexplained.

These results have three important implications for management. Firstly, patients should be counselled about the more favourable clinical course of genital HSV-1 than of HSV-2 infection; recurrences are generally milder and infrequent. Secondly, subclinical shedding of HSV-1 is less common; this has a direct bearing on the likelihood of transmission.5 Thirdly, preventive strategies for genital herpes should focus on the risk of unprotected orogenital intercourse, which is frequently perceived as “safe” in the context of sexually transmitted infections.

Figure.

Proportion (%) of herpes simplex virus test that were type 1

Acknowledgments

We thank Geoffrey Clements, previously director of the West of Scotland Specialist Virology Centre.

Footnotes

Funding: No additional funding.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Lamey P-J, Hyland PL. Changing epidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 1 infections. Herpes. 1999;6:20–24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scoular A, Gillespie G, Carman WF. Polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of genital herpes in a genitourinary medicine clinic. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78:21–25. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vyse AJ, Gay NJ, Slomka M, Gopal R, Gibbs T, Morgan-Capner P, et al. The burden of infection with HSV-1 and HSV-2 in England and Wales: implications for the changing epidemiology of genital herpes. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76:183–187. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.3.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson AM, Wadsworth J, Wellings K, Field J. Sexual attitudes and lifestyles. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lafferty WE, Coombs RW, Benedetti J, Critchlow C, Corey L. Recurrences after oral and genital herpes simplex virus infection: influence of site of infection and viral type. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1444–1449. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706043162304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]