Abstract

This is an observational case report to detail a novel case of scleroderma renal crisis presenting as bilateral exudative retinal detachments in a patient with newly diagnosed systemic sclerosis. An otherwise healthy 58-year-old female presented primarily with vision complaints and was found to have malignant hypertension (230/120 mm Hg) and bilateral exudative retinal detachment on dilated fundus examination and macular OCT scan. Further history revealed sclerodactyly, mild dysphagia, and dyspnea. She was diagnosed with diffuse systemic sclerosis and Sjogren’s syndrome complicated by an episode of scleroderma renal crisis based on initial medical workup. She was admitted to intensive care for management of refractory hypertension with IV antihypertensive therapy. Three months after treatment, her visual symptoms and ocular findings resolved. The presence of exudative retinal detachment among other signs of hypertensive retinopathy warrants thorough systemic screening for underlying causes of malignant hypertension, including systemic sclerosis. Treatment of the underlying disease with urgent antihypertensive therapy resolved the exudative retinal detachments and restored vision in the case of a scleroderma renal crisis.

Keywords: Hypertensive retinopathy, Exudative retinal detachment, Scleroderma renal crisis, Systemic sclerosis

Introduction

Severe hypertension is a risk factor for several vision-threatening conditions, with hypertensive retinopathy being the most common pathological presentation [1]. Chronic hypertensive damage typically presents with generalized retinal arteriolar narrowing and arteriovenous nicking, whereas the presence of retinal hemorrhages, microaneurysms, cotton-wool spots, and hard exudates in addition to optic disc edema and serous retinal detachment are suggestive of acute changes in blood pressure [2]. Patients with severe hypertensive retinopathy in the context of a hypertensive crisis present a medical emergency that requires immediate evaluation and treatment for secondary causes of hypertension to prevent further end-organ damage. A rare but important cause of hypertensive crisis is systemic sclerosis – also known as scleroderma – an autoimmune, inflammatory, fibrotic connective tissue disease that affects the skin and the cardiovascular, respiratory, renal and gastrointestinal systems [3]. Patients may progress to develop scleroderma renal crisis, an acute condition characterized by sudden-onset marked hypertension and acute kidney injury [4]. Clinical features include fatigue, generalized malaise, headaches, seizures, encephalopathy with confusion and change in mental status, fever, congestive heart failure, thrombocytopenia, and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia [5]. Published literature on the extent of ocular involvement in systemic sclerosis describes dry eye and periocular skin changes highlighting the rare nature of the disease and its ocular manifestations [6–8]. To our knowledge, there have been no reports of visual changes as the presenting symptom of scleroderma renal crisis. This paper describes a 58-year-old female who presented with blurred vision due to bilateral exudative retinal detachment and was found to have diffuse systemic sclerosis complicated by a scleroderma renal crisis. We demonstrate resolution of visual symptoms and ocular findings with the initiation of aggressive antihypertensive therapy. The CARE Checklist has been completed by the authors for this case report, attached as online supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000530973).

Case Report

A 58-year-old woman was seen for a 1-month history of progressive bilateral blurred vision and intermittent headaches. She had no known past medical or ocular history and was not on any medications. On examination, her best corrected visual acuity was 20/25 in the right eye, and 20/70 + 1 in the left eye. Her intraocular pressures were 15 mm Hg in the right eye and 14 mm Hg in the left. Anterior segment examination was normal aside from 1+ nuclear sclerotic cataract in both eyes. Dilated fundus examination revealed bilateral large exudative retinal detachments temporally and superiorly approaching the macule in both eyes. There were multiple exudates and cotton-wool spots present in the macular area of both eyes. Paton’s lines were present around the optic nerves with no clear optic nerve head elevation. Macular OCT revealed inner retinal layer thickening of both eyes with macular subretinal fluid in the left eye (Fig. 1).

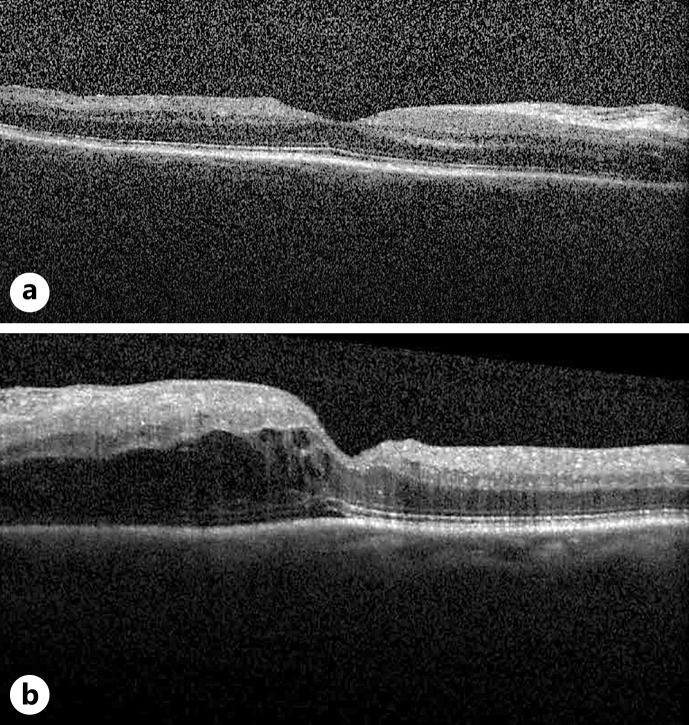

Fig. 1.

OCT images of the macula from day of presentation of the right eye (a) and left eye (b). Blood pressure was 230/120 mm Hg.

Given the signs and symptoms of potential hypertensive retinopathy and hypertensive crisis, the patient’s blood pressure was immediately assessed. She was found to be hypertensive at 230/120 mm Hg. The patient was transferred to the emergency department and admitted to hospital for further workup and management. Further questioning revealed she had a 1-month history of preceding exertional shortness of breath, Raynaud’s phenomenon occurring 4 years prior, mild esophageal dysmotility, and longstanding pruritus. Physical examination showed skin thickening on her dorsal hands bilaterally extending to upper arms, facial skin thickening resulting in reduced expressiveness, sclerotic appearance of skin over her legs, significantly reduced mouth opening, and dry lips.

Initial systemic workup showed low hemoglobin (67 g/L) and platelets (71 × 109/L) with evidence of schistocytes and hemolysis. She had evidence of acute kidney injury with an initial creatinine of 324 μmol/L which was previously normal. A rheumatological workup showed positive results for ANA at 1:160, anti PM/Scl-100, and anticardiolipin IgG at 29. She has negative results for anti-GBM, ANCA, lupus anticoagulant, and anti-dsDNA. A kidney biopsy showed features compatible with systemic sclerosis including thrombotic microangiopathy involving the arterioles and glomeruli, severe interstitial fibrosis, and tubular atrophy.

She was diagnosed with diffuse systemic sclerosis and Sjogren’s syndrome complicated by an episode of scleroderma renal crisis. She was briefly admitted to the intensive care unit for management of refractory hypertension with IV antihypertensive medications and afterward maintained on an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.

The patient was reassessed 1 week later by ophthalmology. Best corrected visual acuity was 20/60 in the right eye and 20/50 + 1 in the left. A dilated fundus examination showed resolving exudative retinal detachment in both eyes along with bilateral cotton-wool spots of the macula (Fig. 2a, b). Retinal OCT demonstrated ongoing subretinal fluid (Fig. 2c, d). Following discharge from hospital, the patient was reassessed by ophthalmology 3 months after initial presentation. Visual acuity was 20/25 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left. An OCT and dilated fundus examination revealed no retinal detachment (Fig. 3). There was interval resolution of cotton-wool spots.

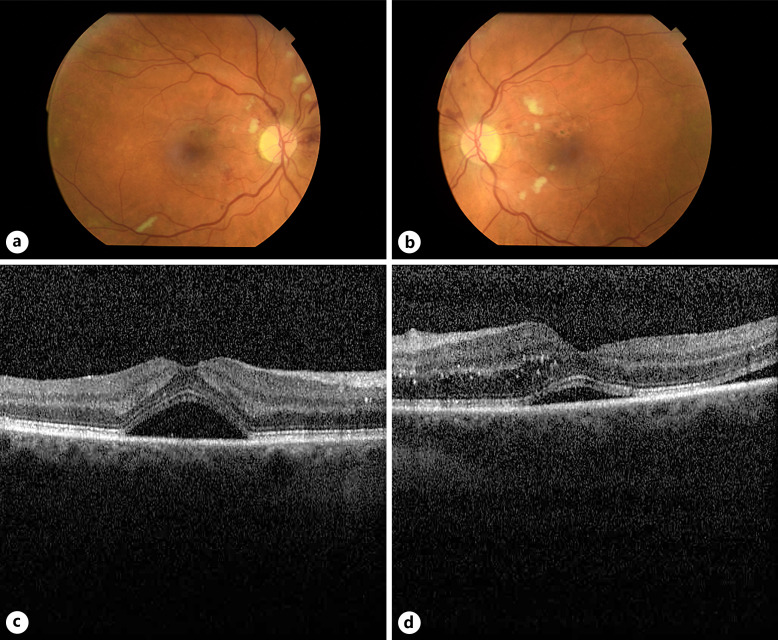

Fig. 2.

Images taken 1 week after presentation and initiation of blood pressure control. Color fundus photographs of the right eye (a) and left eye (b). OCT images of the macula of the right eye (c) and left eye (d). Blood pressure was 149/79 mm Hg.

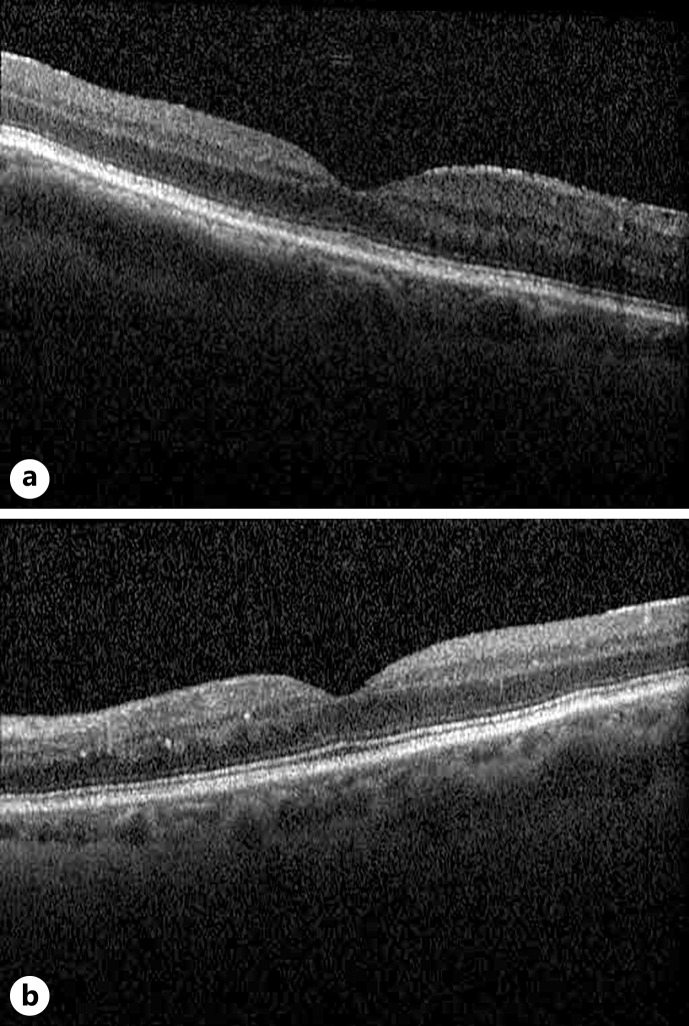

Fig. 3.

Representative OCT of the macula in the right eye (a) and left eye (b) 3 months after initial presentation. Blood pressure was 140/100 mm Hg.

The patient’s kidney function did not improve despite medical management and hemodialysis was required. A year after her initial presentation, she developed end-stage renal disease with a stable creatinine around 450–550 μmol/L. Her systemic sclerosis was stable on mycophenolate for pruritus and pantoprazole, but no other immunosuppressive therapy was required. Her blood pressure was stable at 140/100 mm Hg on amlodipine, bisoprolol, and perindopril. She was deemed to be a suitable candidate for renal transplantation and is currently awaiting a donor.

Discussion

We present a 58-year-old female with a chief complaint of subacute blurred vision, found to have bilateral exudative retinal detachment and malignant hypertension. Workup revealed diffuse systemic sclerosis complicated by an episode of scleroderma renal crisis which was managed with aggressive antihypertensive therapy after which her visual symptoms successfully resolved.

Signs of hypertensive retinopathy can be detected in 2%–15% of the nondiabetic population, including those without a known history of hypertension [9]. It is a predictive risk factor for stroke and cardiovascular mortality and can present as the initial finding of a more insidious disease process [10]. Retinal microvascular changes are graded based on severity using the Mitchell-Wong system, which classifies serous retinal detachment as a marker of malignant hypertension (Table 1). The differential diagnosis for serous retinal detachment is extensive, including a variety of conditions categorized into inflammatory, infectious, neoplastic, vascular and congenital etiologies. Many of these conditions warrant prompt workup and management, guided by careful clinical history and the presence of ocular and systemic signs.

Table 1.

Classification of hypertensive retinopathy using the Mitchell-Wong system

| Grade of Retinopathy | Clinical Findings |

|---|---|

| Mild | One or more of the following: generalized or focal arteriolar narrowing, arteriovenous nicking, and copper wiring of the arteriolar wall |

| Moderate | One or more of the following: retinal hemorrhages (blot, dot, or flame-shaped), microaneurysms, cotton-wool spots, and hard exudates |

| Malignant | Includes signs of moderate retinopathy in addition to disc edema due to optic nerve ischemia or serous retinal detachment secondary to fibrinoid necrosis of choroidal arterioles |

Scleroderma renal crisis is a life-threatening complication of systemic sclerosis, arising in the first 4 years after diagnosis, typically with sudden-onset malignant hypertension and acute kidney injury that present as neurologic symptoms [5]. Documented ocular manifestations are rare and demonstrate limited reported associations, mainly in terms of dry eye symptoms and decreased choroidal thickness [8]. Less than 10% of patients with systemic sclerosis are affected, rarely of whom present with ocular manifestations as their chief complaint [5]. The presence of acute bilateral exudative retinal detachments likely corresponds to underlying endothelial injury related to malignant hypertension as opposed to a combination of fibrosis and vasculopathy that result in eyelid, conjunctival, dry eye, and choroidal perfusion disorders in systemic sclerosis [5, 8]. A recent review highlighted retinal changes in 34% of subjects with systemic sclerosis (n = 29), with the main posterior segment finding being related to microvascular changes such as hard exudates and vascular tortuosity. However, these observations were made based on fundus photos without OCT, and the latter is shown in this report. Additionally, none of these patients presented with active scleroderma renal crisis or retinal detachment, making our case unique in the literature. In retrospect, systemic signs of scleroderma had been present given the patient’s history of sclerodactyly, dyspnea, and dysphagia; however, this case highlights the importance of prompt recognition of ocular manifestations to prevent the sequelae of end-stage organ damage.

Generally, serous retinal detachments resolve with appropriate management of underlying disease, though further intervention may be required in severe cases. Given the rare nature of systemic sclerosis and limited literature on ocular involvement, recommendations do not exist to guide specific treatment. However, as demonstrated in our case through serial fundus examinations and OCT imaging, antihypertensive IV therapy is sufficient for resolution of retinal findings and improvement of vision.

In summary, we present the case of a previously healthy patient diagnosed with scleroderma renal crisis in the context of diffuse systemic sclerosis, whose primary presenting complaint was blurred vision found to be due to bilateral exudative retinal detachment. Although ocular involvement in systemic sclerosis is rare, its detection and differentiation from other etiologies is crucial for the timely management and prevention of further organ damage. Vision may be restored in cases of serous retinal detachment due to scleroderma renal crisis by urgent intervention with antihypertensive therapy. This case contributes an additional vignette to the growing literature on the ocular manifestations of systemic sclerosis and the efficacy of aggressive antihypertensive management. It also serves to highlight consideration of scleroderma renal crisis when evaluating patients with malignant hypertension who present with acute ocular involvement including bilateral exudative retinal detachments.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank the patient and the team involved in the provision of their care.

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the details of their medical case and accompanying images. This report does not contain any personal information that could lead to the identification of the patient. The research was conducted ethically in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval is not required for this study in accordance with local or national guidelines.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No funding was received for this case report.

Author Contributions

R.A.: literature review, manuscript writing and editing, and preparing the final version for submission. C.L. and J.D.: patient clinical care, chart analysis, and manuscript writing and editing. B.H.: patient clinical care and manuscript overview and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding Statement

No funding was received for this case report.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. Tsukikawa M, Stacey AW. A review of hypertensive retinopathy and chorioretinopathy. Clin Optom. 2020;12:67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Naranjo M, Chauhan S, Paul M. Malignant hypertension. StatPearls: management of acute kidney problems. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. [cited 2022 Oct 4]. p. 305–16. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507701/ [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hinchcliff M, Varga J. Systemic sclerosis /scleroderma: a treatable multisystem disease. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(8):961–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Denton CP, Lapadula G, Mouthon L, Müller-Ladner U. Renal complications and scleroderma renal crisis. Rheumatology. 2009;48(Suppl 3):iii32–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bose N, Chiesa-Vottero A, Chatterjee S. Scleroderma renal crisis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;44(6):687–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. West RH, Barnett AJ. Ocular involvement in scleroderma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1979;63(12):845–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tailor R, Gupta A, Herrick A, Kwartz J. Ocular manifestations of scleroderma. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54(2):292–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kreps EO, Carton C, Cutolo M, Cutolo CA, Vanhaecke A, Leroy BP, et al. Ocular involvement in systemic sclerosis: a systematic literature review, it’s not all scleroderma that meets the eye. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;49(1):119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wong TY, Mitchell P. Hypertensive retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(22):2310–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wong TY, Mitchell P. The eye in hypertension. Lancet. 2007;369(9559):425–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.