Abstract

Introduction

Erythema nodosum (EN) is the most common form of panniculitis. EN can be idiopathic or secondary to an underlying systemic disease, infection, drug use, or tumor. CD5-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (CD5+ DLBCL) is a relapsed and refractory lymphoma, and further understanding of its pathology is required. We report a case of newly diagnosed CD5+ DLBCL with concomitant EN. Within the scope of our search, there were no reports of CD5+ DLBCL complicated with EN.

Case Presentation

A 79-year-old woman experienced swelling, warmth, redness, and pain in both legs and a mass lesion on the right side of the back at almost the same time. The respective lesions were diagnosed as EN and CD5+ DLBCL by biopsy. With chemotherapy, the lymphoma and EN improved in parallel courses. The patient has completed scheduled chemotherapy, and there has been no recurrence of swelling in the legs or mass on the right side of the back.

Discussion

The lymphoma and EN developed simultaneously and followed a parallel clinical course after chemotherapy, suggesting that EN was a paraneoplastic symptom of CD5+ DLBCL. Recognizing and treating underlying malignancies in patients presenting with EN is crucial.

Keywords: CD5-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Erythema nodosum, Immune complexes, Paraneoplastic symptoms

Introduction

Panniculitis is an inflammation of subcutaneous fat. Erythema nodosum (EN) is the most common form of panniculitis. Lesions can occur anywhere on the body, including the face, but are mainly localized to the extensor surfaces of the legs and are characterized by painful, round or oval, erythematous, firm, and solid nodules. In addition to the cutaneous manifestations of the disease, patients with EN may present with nonspecific systemic symptoms, such as fever, fatigue, joint pain, and arthritis. The classic pathological finding is septal panniculitis without vasculitis; however, this abnormality changes over time. Early lesions show septal edema and lymphohistiocytic infiltration, with a mixture of neutrophils and eosinophils. Inflammation is usually concentrated around the septum and spreads to the surrounding fat lobules between fat cells. The degree of vascular damage varies; however, edema and lymphocytic infiltration may occur in vein walls. Older lesions show less vascular changes and a shift from primarily neutrophilic infiltrates to either lymphocytes or histiocytes [1, 2]. EN is considered a reactive process triggered by various stimuli. Although half of the causes cannot be identified, the possible causes include infections, sarcoidosis, autoimmune diseases, pregnancy, and drug use. Although rare, there have been reports of malignant tumors, including malignant lymphoma, as causes of EN [2–4].

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) accounts for approximately 30% of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and is a heterogeneous disease with various subsets. It is estimated that 5–10% of DLBCLs express CD5, a rare subset [5]. Classical DLBCL is morphologically classified into three common and several variants: centroblastic (80%), immunoblastic (8–10%), anaplastic (3%), and other rare variants. On the other hand, CD5-positive (CD5+) DLBCL is reported in four variants: commonly described as monomorphic or centroblastic (76%), immunoblastic (1%), giant cell-rich (11%), and polymorphic (12%). Both giant cell-rich and anaplastic variants have a poor prognosis. However, the giant cell-rich variant in CD5+ DLBCL is more frequent than the anaplastic variant in classical DLBCL, which may explain the overall poorer prognosis of CD5+ DLBCL compared with classical DLBCL. CD5+ DLBCL is mostly positive for CD10, Bcl2, and Mum1 immunohistochemically [6]. Patients with CD5+ DLBCL are more likely to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 1 or higher, a higher International Prognostic Index score, develop B symptoms, and have a higher rate of central nervous system recurrence and bone marrow involvement than those with CD5-negative DLBCL [6]. CD5+ DLBCL is recognized as a particularly aggressive subtype and requires further understanding [5, 6].

There have been some cases of DLBCL complicated by EN; however, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no mention of CD5 positivity [7, 8]. We report a case of simultaneous CD5+ DLBCL and EN.

Case Report

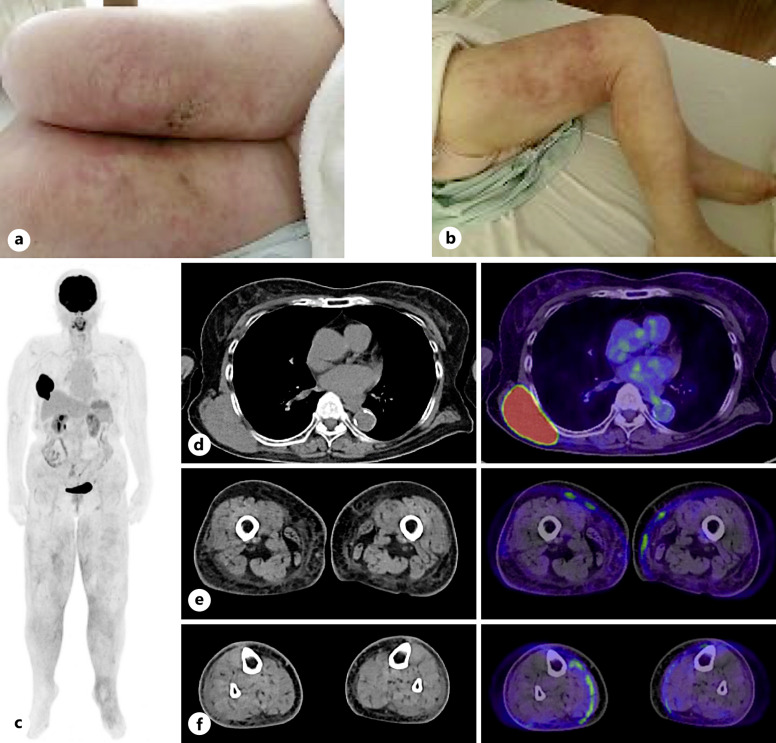

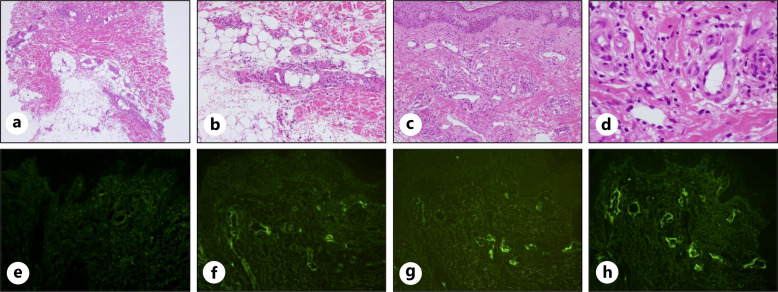

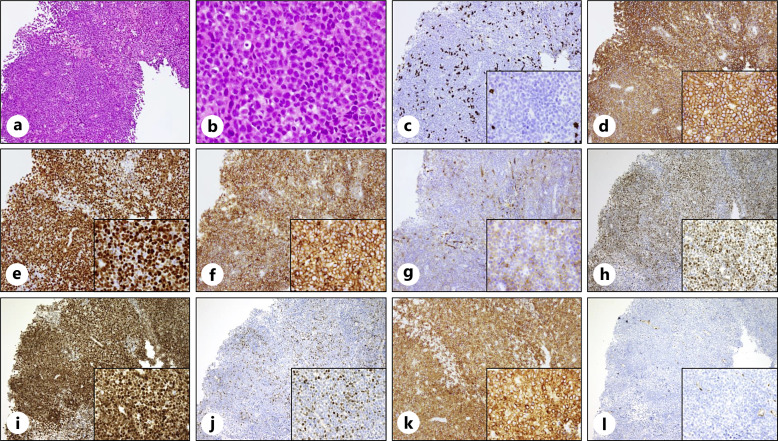

A 79-year-old woman noticed edema and pain in the right leg in early August and a mass on the right side of the back in late August. In early September, the patient experienced a burning sensation and pain because edema, redness, and warmth appeared in both legs. The patient was prescribed topical medications and diuretics by a local physician, but there was no improvement; therefore, the patient visited our hospital in early October. The patient had been taking irbesartan and amlodipine for hypertension for 6 years, had leg numbness and knee pain since a lumbar compression fracture 4 years prior, and had been taking limaprost alfadex and Tsumura-Kampo boiogito extract granules. Laboratory tests revealed increased lactate dehydrogenase and sIL-2R levels. Although an increase in IgG and IgA was observed, immunoelectrophoresis did not reveal the presence of M protein (data not shown). Elevated complement levels were observed, and autoantibodies, including anti-nuclear antibody, myeloperoxidase anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, proteinase-3 anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, IgG-rheumatoid factor, anti-SS-A antibody, anti-SS-B antibody, and anti-double stranded DNA IgG antibody, were negative. The examination revealed no obvious evidence of infection, including hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, human T-cell leukemia virus type 1, human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and tuberculosis (Table 1). Physical examination revealed swelling, redness, warmth, and hardened skin lesions on both legs (Fig. 1a, b). No skin lesions were observed on the face, upper limbs, or trunk. Other than the legs, there were no signs of inflammation in the hands, or joints. A 7 cm tumor was found on the patient’s right side of the back. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET-CT) revealed a mass with abnormal F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake on the right side of the back. Edema with subcutaneous fat tissue opacity and mild FDG accumulation were observed (Fig. 1c–f). Skin biopsy of the right thigh was performed. Neutrophils infiltrated the subcutaneous tissue, and fibrous septa were observed (Fig. 2a, b). Although mild inflammatory cell infiltration was observed around the blood vessels in the dermis, there were few signs of vasculitis, such as destruction or damage to the blood vessel wall, followed by hemorrhage and ischemia (Fig. 2c, d). Immunohistochemical staining revealed IgA, IgM, and C3c deposition on the vessel wall but no IgG deposition (Fig. 2e–h). The patient was diagnosed with EN due to septal panniculitis without vasculitis. In addition, biopsy of the right dorsal mass revealed diffuse proliferation of medium-to-large cells with round nuclei and increased chromatin (Fig. 3a, b). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD20, CD5, MUM-1, BCL6, and BCL2; partially positive for CD10; and negative for CD3, c-Myc, and cyclin D1. The Ki-67 positivity rate was >90% (Fig. 3c–l). Therefore, the mass on the right side of the back was diagnosed as CD5+ DLBCL. The bone marrow examination revealed no obvious lymphoma infiltration. The lymphoma stage was IA, and the International Prognostic Index indicated a low-intermediate risk. After 1 cycle of chemotherapy (pola-R-CHP; polatuzumab vedotin, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisolone) alleviated symptoms in the legs, and the mass on the right side of the back was barely visible. No severe adverse events due to chemotherapy were observed. After the patient completed 6 cycles of chemotherapy, PET-CT showed decreased mass on the right side of the back and decreased FDG accumulation in the mass and legs, indicating metabolic complete response. It has been 2 months since the last chemotherapy, and there has been no recurrence of swelling in the legs or mass on the right side of the back. The CARE Checklist has been completed by the authors for this case report, attached as online supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000540913).

Table 1.

Patient’s laboratory data on admission

| Complete blood count | Biochemistry | TSH | 2.24 | μIU/mL | Infection | ||||||||||

| WBC | 4,590 | /μL | TP | 7.8 | g/dL | FT3 | 1.54 | pg/mL | ↓ | HBs Ag | (−) | ||||

| Seg | 84.0 | % | ↑ | Alb | 3.5 | g/dL | ↓ | FT4 | 0.72 | ng/dL | HBs Ab | (−) | |||

| St | 1.0 | % | T-Bil | 0.7 | mg/dL | IgG | 2,031 | mg/dL | ↑ | HBc Ab | (−) | ||||

| Ly | 7.0 | % | ↓ | AST | 40 | U/L | ↑ | IgA | 522 | mg/dL | ↑ | HCV Ab | (−) | ||

| Mon | 7.0 | % | ALT | 11 | U/L | IgM | 82 | mg/dL | HTLV-1 | (−) | |||||

| Eos | 1.0 | % | ALP | 92 | U/L | C3 | 155 | mg/dL | ↑ | HIV | (−) | ||||

| Bas | 0.0 | % | γ-GTP | 21 | U/L | C4 | 42 | mg/dL | ↑ | β-D-glucan | <4.0 | pg/mL | |||

| RBC | 3.05 | 106/μL | ↓ | ChE | 185 | U/L | ↓ | CH50 | 56.5 | CH50/mL | ↑ | Epstein-Barr virus | |||

| Hb | 9.8 | g/dL | ↓ | LDH | 611 | U/L | ↑ | ANA | <40 | VCA-IgG | 160 | ||||

| Het | 29.3 | % | ↓ | BUN | 9.2 | mg/dL | MPO-ANCA | <1.0 | U/mL | VCA-IgA | <10 | ||||

| MCV | 96.1 | fl | Cre | 0.77 | mg/dL | PR3-ANCA | <1.0 | U/mL | VCA-IgM | <10 | |||||

| MCH | 32.2 | pg | UA | 8.5 | mg/dL | ↑ | IgG-RF | 1.3 | IgG-RF | EA-DR-IgG | <10 | ||||

| MCHC | 33.5 | g/dL | Na | 139 | mmol/L | SSA Ab | <1.0 | U/mL | EA-DR-IgA | <10 | |||||

| PLT | 344 | 103/μL | Cl | 100 | mmol/L | ↓ | SSB Ab | <1.0 | U/mL | EA-DR-IgM | <10 | ||||

| Coagulation | K | 3.8 | mmol/L | dsDNA IgG Ab | 2.8 | IU/mL | EBNA | 160 | |||||||

| PT | 103 | % | Ca | 9.4 | mg/dL | Urine test | CMV-IgG | 1,296.7 | AU/mL | ↑ | |||||

| APTT | 55.6 | sec | ↑ | IP | 3.8 | mg/dL | Appearance | Yellow | CMV-IgM | 0.09 | Index | ||||

| Fib | 423 | mg/dL | ↑ | CRP | 5.86 | mg/dL | ↑ | pH | 6.5 | T-Spot.TB | (−) | ||||

| FDP | 10.0 | μg/mL | ↑ | BS | 103 | mg/dL | Specific gravity | 1.002 | |||||||

| D-dimer | 3.0 | μg/mL | ↑ | HbA1c | 4.9 | % | Protein | (−) | |||||||

| Coombs test | Fe | 36 | μg/dL | ↓ | Glucose | (−) | |||||||||

| DAT | (−) | TIBC | 252 | μg/dL | Urobilinogen | (±) | |||||||||

| IAT | (−) | FER | 501.4 | ng/mL | ↑ | Bilirubin | (−) | ||||||||

| β2-MG | 4.16 | mg/L | ↑ | Ketone | (−) | ||||||||||

| sIL-2R | 1,289 | U/mL | ↑ | Occult blood | (−) | ||||||||||

Up and down arrows indicate values higher and lower than the reference value in our hospital, respectively.

WBC, white blood cells; Seg, segmented cell; St, stab cell, Ly, lymphocyte; Mon, monocyte; Eos, eosinophils; Bas, basophils; RBC, red blood cells; Hb, hemoglobin; Het, hematocrit; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; PLT, platelets; PT, prothrombin time; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; Fib, fibrinogen; FDP, fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products; DAT, direct antiglobulin test; IAT, indirect antiglobulin test; TP, total protein; Alb, albumin; T-Bil, total bilirubin; AST, aspartate aminotransaminase; ALT, alanine aminotransaminase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; γ-GTP, gamma glutamyl transpeptidase; ChE, cholinesterase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cre, creatinine; UA, uric acid; Na, natrium; Cl, chloride; K, potassium; Ca, calcium; IP, inorganic phosphorus; CRP, C-reactive protein; BS, blood sugar; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; Fe, iron; TIBC, total iron-binding capacity; FER, ferritin; β2-MG, beta 2-microglobulin; sIL-2R, soluble interleukin-2 receptor; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; FT3, free tri-iodothyronine; FT4, free thyroxine; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgM, immunoglobulin M; C3, complement 3; C4, complement 4; CH50, complement activity; ANA, anti-nuclear antibody; MPO-ANCA, myeloperoxidase anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; PR3-ANCA, proteinase-3 anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; IgG-RF, IgG-rheumatoid factor; SSA Ab, anti-SS-A antibody; SSB Ab, anti-SS-B antibody; dsDNA IgG Ab, anti-double stranded DNA IgG antibody; HBs Ag, hepatitis B virus surface antigen; HBs Ab, hepatitis B virus surface antibody; HBc Ab, hepatitis B virus core antibody; HCV ab, hepatitis C virus antibody; HTLV-1, human T-cell leukemia virus type 1; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; VCA, viral capsid antigen; EA-DR, early antigen diffuse-type and restricted-type; EBNA, Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen; CMV, cytomegalovirus; T-Spot.TB, interferon gamma release assay for tuberculosis.

Fig. 1.

a, b Images of legs and positron emission tomography/computed tomography before chemotherapy Leg appearance. c Whole-body positron emission tomography/computed tomography images. d F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose abnormal accumulations in the mass on the right side of the back. e, f Both legs show subcutaneous fat tissue opacity and mild F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.

Fig. 2.

Histopathology of EN histological findings of the skin reveal that neutrophils infiltrated the subcutaneous tissue; fibrous septa are observed (hematoxylin-eosin staining; a, ×4 magnification; b, ×10 magnification). Mild inflammatory cell infiltration around the blood vessels is observed (hematoxylin-eosin staining; c, ×10 magnification; d, ×40 magnification). Immunohistochemical staining for IgG (e), IgA (f), IgM (g), and C3c (h).

Fig. 3.

Histopathology of CD5+ DLBCL histological findings of the right dorsal mass reveal a diffuse proliferation of medium-to-large-sized cells with round nuclei and increased chromatin (hematoxylin-eosin staining; a, ×10 magnification; b, ×40 magnification). Immunohistochemical staining of CD3 (c), CD20 (d), Ki-67 (e), CD5 (f), CD10 (g), BCL6 (h), MUM-1 (i), c-Myc (j), BCL2 (k), and cyclin D1 (l) (×10 magnification; ×40 magnification in the enlarged images).

Discussion

The exact etiology of EN is unknown, but it is probably a delayed hypersensitivity reaction caused by the deposition of immune complexes in the septal venules of subcutaneous fat, leading to neutrophilic panniculitis [2]. CD5+ DLBCL cells overexpress IL-10, BCL2, cyclin D2, and CXCR4 [6]. Furthermore, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), known as a CD5+ B-cell tumor, is also known to produce IL-10 [9]. IL-10 is a tolerogenic cytokine that inhibits proinflammatory cytokine production and T-cell stimulatory ability. In contrast, IL-10 is a growth and differentiation factor for B cells and may promote the production of autoantibodies [10]. In this case, although the surface immunoglobulins of lymphoma cells were not tested, an increase in IgG and IgA levels was observed in the serum. An immunoelectrophoretic test of the serum was performed, but the M protein was not detected. In addition, fluorescence microscopy revealed deposition of IgA, IgM, and C3c on blood vessel walls. Although these results indicated an increase in polyclonal immunoglobulins rather than monoclonal immunoglobulins from the tumor itself, the involvement of tumor-derived immunoglobulins could not be completely ruled out. Immune-related abnormalities may underlie the mechanisms underlying the onset of EN. However, if EN development is dependent on CD5+ B-cell tumors, then the incidence of EN in CD5+ DLBCL and CLL should be high. Therefore, multiple factors, in addition to CD5+ B-cell tumors, may be involved in the development of EN.

Approximately half of EN cases are idiopathic, and secondary EN is commonly caused by infections and sarcoidosis. Nevertheless, EN can be associated with malignant tumors [4, 11–13]. There are two important criteria for skin lesions to be considered paraneoplastic symptoms of neoplasms. First, skin lesions develop after the onset of the neoplasm. Second, skin lesions and neoplasms follow a parallel clinical course. However, it is difficult to determine the onset of tumor development; therefore, it is often difficult to prove that skin lesions occur after the development of neoplasms [14]. Fortunately, in this case, the tumor was noticed within 1 month after the appearance of EN in the lower extremities because DLBCL was palpable. If the tumor is located deep in the body, its presence may be underestimated and misdiagnosed as idiopathic EN. If a patient is diagnosed with idiopathic EN, treatment includes non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, colchicine, and potassium iodide for mild disease and prednisone and immunosuppressive medications such as methotrexate for severe, chronic, and recurrent disease [2]. However, in paraneoplastic EN, treatment of the underlying disease is important [1]. Even if EN is determined to be idiopathic, careful observation is necessary because the tumor may be located deep or become apparent after a delay.

In this case, the tumor size decreased, and EN significantly improved with chemotherapy. The tumor and EN developed simultaneously and followed a parallel clinical course after chemotherapy, suggesting that EN was a paraneoplastic symptom of CD5+ DLBCL. However, the prednisolone and rituximab contained in chemotherapy have a high immunosuppressive effect. It should be noted that the improvement of EN by chemotherapy may be due to not only the indirect effect of malignant lymphoma suppression but also the direct effect of immunosuppression.

A limitation of this study was that only a portion of the skin lesion was biopsied. In a report on biopsies of tender skin nodules on the lower legs, the incidence of skin infiltration by malignant tumors such as lymphoma or leukemia was 6.5%, whereas the incidence of panniculitis, including EN, was 84% [15]. In de novo CD5+ DLBCL patients, 6 of 109 (5.5%) had skin or subcutaneous tissue involvement [16]. Although skin involvement secondary to DLBCL is rare, it has been reported in up to 20% of cases in some reports [17]. Although the diagnosis of EN appears to have some certainty, it is difficult to infiltration of DLBCL into other skin tissues cannot be completely excluded.

In summary, we report a case in which EN developed as a paraneoplastic symptom of CD5+ DLBCL. As paraneoplastic EN requires treatment of the underlying disease, it is crucial to investigate the cause of EN. Because it is unclear whether CD5+ neoplastic B cells play a role in EN development, future case studies are desirable.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Editage for the English language review.

Statement of Ethics

Ethical approval is not required for this study in accordance with local or national guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

This study did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Author Contributions

M.A. performed conceptualization, data curation, investigation, supervision, visualization, and writing – original draft. K.O., Y.N., Y.S., and H.S. performed investigation and writing – review and editing. The work reported in the paper has been performed by the authors.

Funding Statement

This study did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. Hafsi W, Badri T. Erythema nodosum. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Discl Talel Badri Declares Relevant Financ Relat Ineligible Companies; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blake T, Manahan M, Rodins K. Erythema nodosum – a review of an uncommon panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20(4):22376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schattner A, Uliel L, Dubin I. The cat did it: erythema nodosum and additional atypical presentations of Bartonella henselae infection in immunocompetent hosts. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2017222511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. García-Porrúa C, González-Gay MA, Vázquez-Caruncho M, López-Lazaro L, Lueiro M, Fernández ML, et al. Erythema nodosum: etiologic and predictive factors in a defined population. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(3):584–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Durani U, Ansell SM. CD5+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a narrative review. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;62(13):3078–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xu Y, Sun W, Li F. De novo CD5(+) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: biology, mechanism, and treatment advances. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(10):e782–e790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kav T, Ozen M, Uner A, Abdullazade S, Ozseker B, Bayraktar Y. How confocal laser endomicroscopy can help us in diagnosing gastric lymphomas? Bratisl Lek Listy. 2012;113(11):680–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheong KA, Rodgers NG, Kirkwood ID. Erythema nodosum associated with diffuse, large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma detected by FDG PET. Clin Nucl Med. 2003;28(8):652–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. DiLillo DJ, Weinberg JB, Yoshizaki A, Horikawa M, Bryant JM, Iwata Y, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia and regulatory B cells share IL-10 competence and immunosuppressive function. Leukemia. 2013;27(1):170–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Geginat J, Larghi P, Paroni M, Nizzoli G, Penatti A, Pagani M, et al. The light and the dark sides of interleukin-10 in immune-mediated diseases and cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016;30:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cribier B, Caille A, Heid E, Grosshans E. Erythema nodosum and associated diseases. A study of 129 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37(9):667–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Psychos DN, Voulgari PV, Skopouli FN, Drosos AA, Moutsopoulos HM. Erythema nodosum: the underlying conditions. Clin Rheumatol. 2000;19(3):212–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mert A, Kumbasar H, Ozaras R, Erten S, Tasli L, Tabak F, et al. Erythema nodosum: an evaluation of 100 cases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25(4):563–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McLean DI. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122(7):765–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eimpunth S, Pattanaprichakul P, Sitthinamsuwa P, Chularojanamontri L, Sethabutra P, Mahaisavariya P. Tender cutaneous nodules of the legs: diagnosis and clinical clues to diagnosis. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52(5):560–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yamaguchi M, Seto M, Okamoto M, Ichinohasama R, Nakamura N, Yoshino T, et al. De novo CD5+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 109 patients. Blood. 2002;99(3):815–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lloret-Ruiz C, Moles-Poveda P, Barrado-Solis N, Gimeno-Carpio E. Diffuse systemic large B-cell lymphoma with secondary skin involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106(8):685–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.