Abstract

Introduction

Fishbone (FB) ingestion is a rare cause of gastrointestinal perforation. Herein, we report a case of FB-induced colonic perforation, in which the presence of a penile colonic carcinoma may have contributed to the development of the perforation.

Case Presentation

An 83-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with severe abdominal pain during bowel movement. Computed tomography (CT) yielded a diagnosis of sigmoid colonic perforation due to FB and secondary peritonitis. Preoperative endoscopic examination suggested that the perforation was associated with a stalked colon tumor in the vicinity. After undergoing low anterior resection and sigmoid colostomy, the patient is currently doing well.

Conclusion

The incidence of FB-induced colorectal-cancer-related perforation is expected to increase in the future owing to an aging society, the increase in the rates of colorectal cancer, and increase in fish consumption. This rare case suggests that preoperative examinations are important and that even relatively small polyps can contribute to gastrointestinal perforation caused by FBs. Older individuals should exercise caution during fish ingestion.

Keywords: Fishbone, Perforation, Colorectal carcinoma, Penile polyp

Introduction

Fish consumption has increased worldwide because of its effect on reducing the risk of cardiovascular diseases [1], and accidental fishbone (FB) ingestion has also become a common clinical issue. After FB ingestion, the most common complication below the diaphragm is perforation of the hollow viscus [2, 3]. Perforation by an FB can occur anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract but is especially likely in areas that are narrow or acutely angled, such as the cricopharyngeus, lower esophagus, or ileocecal and rectosigmoid junctions [4]. Similar to FBs, chicken bones also cause gastrointestinal perforations. Six cases of gastrointestinal perforation caused by chicken or FBs that involved the presence of cancer have been reported in the English literature [5–10]. However, none of the patients had cancer detected by prior endoscopy.

We encountered a case of FB-induced sigmoid colon perforation in which the presence of a stalked polyp may have contributed to the development of the perforation. The presence of the polyp could not be noted on CT but could be noted on endoscopy. Furthermore, we were able to pathologically determine that the polyp was cancerous, and we proceeded with surgery. Although many cases of intestinal perforation caused by FBs have been reported, to the best of our knowledge, none of the previous reports described the involvement of a penile polyp in its development. Therefore, we consider this case to be highly suggestive, and we describe its findings in this report.

Case Report

An 83-year-old man presented with severe abdominal pain and occasional small amounts of dark red blood in his bowel movement that had begun 2 weeks before visiting our hospital. He recalled having a rockfish bone stuck in his throat 2 weeks prior to his visit; he had swallowed the bone with rice, and it then passed into his esophagus.

On examination, his temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate were 36.4°C, 60 beats/min, 118/76 mm Hg, and 16 breaths/min, respectively. The abdomen was soft and flat, with no palpable mass or tenderness. His respiratory and cardiac sounds were normal, and no cardiac murmurs were audible. Laboratory tests revealed moderately elevated levels of C-reactive protein. No other major abnormalities, including abnormalities in tumor marker levels, were observed.

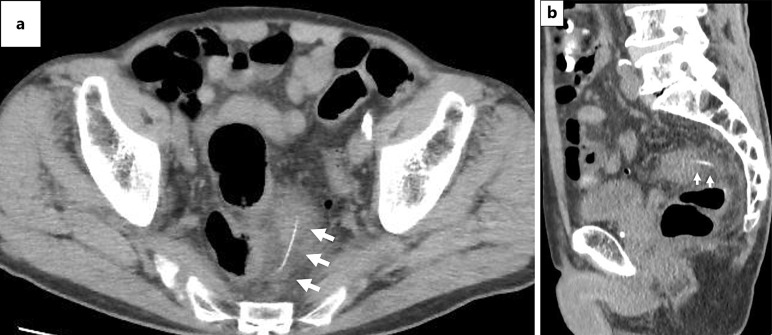

CT showed a 40-mm-long linear structure with a high-density signal (arrows) extending from the lumen to the outer wall of the sigmoid colon, whose wall was thickened with an increased density of surrounding fatty tissue (Fig. 1a, b). However, no images suspicious of colorectal cancer were obtained. Ultrasound (US) examination of the lower abdomen demonstrated a linear hyperechoic structure (arrows) that did not change shape with peristalsis of the intestinal tract (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 1.

CT shows a 40-mm-long linear structure with a high-density signal (arrows) in the axial (a) and sagittal (b) sections. The intestinal wall near the highly dense structure was thickened, and the surrounding fatty tissue concentration was elevated. No obvious tumors were observed.

Fig. 2.

a Abdominal US revealed a high echoic linear structure that did not change shape in the peristaltic intestinal tract (arrows). b A portion of the epithelial tumor is barely visible within the adherent sigmoid colon (arrowheads). This mass was suspected to be mobile because it came out and retracted and later turned out to be colonic cancer. c A mass (arrow heads) with a stalk (arrows) in the rectosigmoid colon was identified. No obvious leakage of contrast media was observed. C, cecum; S, sigmoid colon; R, rectum.

The distal sigmoid colon was so strongly adherent that the colonoscope could not pass through it, and insertion of the scope deeper than the distal sigmoid colon was difficult even when using a thin scope for nasal upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (5 mm in diameter). When the tip of the scope was slightly inserted into the adherent intestine, a part of the erythematous mass (arrowheads) was observed (Fig. 2b). This mass was suspected to be stalked because it came out and retracted; it was later diagnosed as a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma based on the biopsy results returned at a later date.

An enema examination with Gastrografin, a water-soluble contrast agent, revealed a translucent image of a mass (arrowheads) with a stalk (arrows) in the distal sigmoid colon (Fig. 2c). The contrast distribution in the sigmoid colon was normal, and no extramural leakage of the contrast was observed.

On the basis of these examinations, we diagnosed that an FB lodged on the oral side of the sigmoid colon cancer had perforated the intestinal tract, causing peritonitis. A laparoscopic sigmoid colon resection and colostomy were performed. Intraoperative findings showed a 20-mm head-sized early-stage colon cancer (arrowheads) with a stalk (white arrows) in the distal sigmoid colon (Fig. 3a). The area (yellow arrow) perforated by the FB was in the immediate vicinity of the polyp. The FB was 35 mm long (Fig. 3b). The FB (white arrows) had penetrated the sigmoid colon, and the other end was buried in the mesorectum on the rectal side (yellow arrow) (Fig. 3c). Laparoscopic lower anterior resection and sigmoid colostomy were performed, and the patient showed a good postoperative course.

Fig. 3.

Surgical specimen. a A 20-mm head-sized red mass (arrow heads) with a thick stalk (white arrows) was observed in the distal sigmoid colon. A perforation point was present in the immediate vicinity of the polyp. b The removed FB was 35 mm long. c The FB protruding outside the serosa from the sigmoid colon (white arrows) reached the mesorectum of the contralateral rectum (yellow arrow). S, sigmoid colon; R, rectum; O, oral side; A, anal side.

Discussion

Among patients who accidentally ingest a foreign object, 10–20% require endoscopic removal, and approximately 1% develop gastrointestinal tract perforation necessitating surgical intervention [11]. Clinical manifestations in such cases include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, bloody stools, and hematochezia [3, 12]. Since perforation due to accidental ingestion of a foreign body is rare, and the patient may not remember accidental ingestion, perforation may be difficult to differentiate from a malignant tumor, inflammatory mass, or appendicitis [3, 12, 13], necessitating caution. The terminal ileum and sigmoid colon are the most prone to perforation because they are narrow and curved [9]. Large bowel perforations can occur in the presence of ischemia, ulcerative colitis, diverticula, or tumors in the bowel wall [1, 5, 7]. Conversely, colorectal cancer has been discovered due to perforation in a few cases. In the present case, perforation of the sigmoid colon by an FB led to the discovery of a stalked colorectal carcinoma. To our knowledge, this is the first report of FB-induced perforated peritonitis in which the presence of colorectal carcinoma was confirmed by preoperative endoscopic examination.

The definitive diagnosis of FB is established by the demonstration of a linear dense foreign body, which is more sensitive to non-contrast CT than contrast CT [14]. The main imaging features of FB-induced perforation are focal intestinal wall thickening, fat stranding, bowel obstruction, ascites, localized pneumoperitoneum, intra-abdominal abscess, liver abscess, and a linear hyperdense structure in the abdominal cavity in the gastrointestinal tract or within a parenchymal cavity surrounded by inflammatory changes [1, 2]. In this case, the appearance of a 4-cm-long linear structure with a high-density signal, whose wall was thickened with an increased density of surrounding fatty tissue, was thought to be a relatively typical image. US identification of FBs in the gastrointestinal tract has been described in a few reports; however, we were able to identify linear high echoes that did not move during peristalsis of the surrounding gastrointestinal tract. As Kumar et al. [14] noted, US was useful in that it allowed radiation-free assessment to the symptomatic area.

Most FBs pass through the gastrointestinal tract within a week [2]. Many patients are unaware of FB ingestion; however, this patient remembered swallowing a large FB with rice. FB ingestion and the onset of abdominal pain during defecation occurred almost sequentially, suggesting that the swallowed FB migrated to the rectosigmoid colon in a relatively short period and caused perforation. Since most FBs are excreted in the stool without causing any complications in the digestive tract [2, 11], this FB may not have caused perforation if the sigmoid colon had no polyps. Thus, FBs may cause perforation or other accidental injuries relatively quickly if they show stagnation due to impaired passage through the gastrointestinal tract.

The literature contains six cases of malignant disorders in the colon that were discovered incidentally during colon perforation by chicken or fishbones (Table 1; [7], [5], [9], [6], [10], [8]). The shortest perforating bone was 15 mm long, and the longest was 55 mm long. Zeidan et al. [10] also reported perforation with non-spiky bones. In many cases, CT did not indicate the presence of a tumor; however, Yamashita et al. [8] suspected the presence of cancer on a preoperative CT scan, suggesting that a large cancer may be identifiable by careful follow-up CT assessments. Endoscopy at the time of perforation may yield useful information; however, caution should be exercised because it may worsen the disease. McGregor et al. [9] confirmed a mass with a narrowing of 30 cm using prior endoscopy. Moreover, Zeidan et al. [10] reported that perforating chicken bones could be endoscopically removed preoperatively. In the present case, CT did not indicate a tumor; however, preoperative colonoscopy confirmed a neoplastic lesion near the perforation site, and its presence was suspected to have contributed to the perforation. The fact that the patient could undergo surgery after pathological diagnosis of colorectal cancer facilitated a successful surgery.

Table 1.

Review of case reports of fish-/chicken-bone-induced colonic perforation in which cancer is involved in its development (English literature)

| Author, year | Age | Sex | Bone types | Length of bone, mm | Perforation site | Primary or metastatic | Surgical procedure | Country | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osler (1984) | 78 | Female | Chicken | – | Sigmoid colon | Colon cancer | Hartmann’s resection with end sigmoid colostomy | USA | [1–16] |

| Vardaki (2001) | 69 | Male | Chicken | 15 | Sigmoid colon | Colon cancer | Open surgery | Greece | [5] |

| McGregor (2011) | 86 | Male | Chicken | 26 | Sigmoid colon | Colon cancer (5.5 × 4.4 cm circumferential ulcered mass) | Sigmoid resection with end colostomy and Hartmann’s pouch | USA | [9] |

| Terrace (2013) | 85 | Male | Chicken | 55 | Sigmoid colon | Colon cancer (T3N1) | Anterior resection with colorectal anastomosis | UK | [6] |

| Zeidan (2019) | 60 | Female | Chicken | 25 | Sigmoid colon | Metastatic tumor from lung cancer | Hartmann’s resection | UK | [10] |

| Yamashita (2022) | 64 | Male | Fish | 24 | Rectosigmoid colon | Colon cancer (Borrmann type 2) | Hartmann’s resection | Japan | [8] |

| Our case | 88 | Male | Fish | 35 | Rectosigmoid colon | Stalked colon cancer | Anterior resection and sigmoid colostomy | Japan | – |

USA, United States of America; UK, United Kingdom.

In all cases presented in Table 1, the perforation occurred in the sigmoid or rectosigmoid colon. The sigmoid colon is the narrowest portion of the colon, and the presence of a tumor in the sigmoid colon, which is narrow enough for bones to pass through other colons, increases the risk of perforation caused by fish- or chicken bones. In this case, the tumor was in the early stage, relatively small, and stalked, in contrast to the large advanced tumors reported in previous cases. Moreover, in this case, the head of the tumor was approximately 20 mm in diameter and was thought to have obstructed passage. Thus, in a narrow sigmoid colon, even small polyps can result in perforation by FBs.

The risk of accidental ingestion of foreign objects is the highest in children aged <10 years, especially those aged <4 years [15, 16]. Other groups known to be at higher risk include older individuals with prosthetic limbs, psychiatric patients, and alcoholics [11]. The main causes are poor mastication, visual impairment (inability to identify objects), distraction, and drug and alcohol intake [16]. Table 1 shows that fish- and chicken-bone perforations occur relatively frequently in older individuals. This may be due to the fact that accidental ingestion is more common in older individuals due to decreased swallowing function and visual impairment. The low incidence of perforation in children may be attributed to their good gastrointestinal motility. In contrast, the decreased gastrointestinal motility in older individuals may increase the risk of perforations. While many reports of perforation due to chicken bones have been published in the past, reports of perforation due to FBs have emerged more frequently in recent years, perhaps because of the growing awareness of the benefits of and the worldwide increase in fish consumption. Both cases of colon perforation caused by FBs in Table 1 have been reported from Japan, which is surrounded by oceans and has a high rate of fish consumption. Therefore, cases of FB perforation may spread worldwide in the future.

In conclusion, we present a rare case of colorectal perforation caused by an FB. Preoperative endoscopy revealed the involvement of a penile colorectal carcinoma in the development of the perforation, which facilitated the subsequent surgery. This rare case suggests that preoperative examinations are important and that even relatively small polyps can contribute to gastrointestinal perforation caused by FBs. The incidence of FB-induced colorectal-cancer-related perforation is expected to increase in the future owing to an aging society, the increase in the rates of colorectal cancer, and increase in fish consumption. The possibility of perforation by bone must be included in the differential diagnosis of colonic perforation, especially in countries where fish consumption is high. Older people may need to consume fish sold with bones removed or avoid eating fish with hard bones. The CARE Checklist has been completed by the authors for this case report, attached as online supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000541081).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Etsuko Makino, Setsuko Tsujimura, Mayumi Hagiwara, and Tsuyoshi Imoto for their helpful suggestions regarding the manuscript.

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. Ethical approval was not required for this study in accordance with local and national guidelines.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

Author Contributions

A.I. was the patient’s attending physician and drafted the original manuscript. Y.N., M.A., M.N., and K.O. performed surgery. Y.S. performed colonoscopy. H.M. performed enema examination. M.F. performed ultrasound. H.K., A.A., and K.H. contributed to writing – review and editing. H.N. supervised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript draft and revised it critically on intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Funding Statement

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this review are included in this article and its online supplementary material files. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. Paixão TS, Leão RV, de Souza Maciel Rocha Horvat N, Viana PC, Da Costa Leite C, de Azambuja RL, et al. Abdominal manifestations of fishbone perforation: a pictorial essay. Abdom Radiol. 2017;42(4):1087–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bathla G, Teo LL, Dhanda S. Pictorial essay: complications of a swallowed fish bone. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2011;21(1):63–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pinero Madrona A, Fernández Hernández JA, Carrasco Prats M, Riquelme Riquelme J, Parrila Paricio P. Intestinal perforation by foreign bodies. Eur J Surg. 2000;166(4):307–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mutlu A, Uysal E, Ulusoy L, Duran C, Selamoğlu D. A fish bone causing ileal perforation in the terminal ileum. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2012;18(1):89–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vardaki E, Maniatis V, Chrisikopoulos H, Papadopoulos A, Roussakis A, Kavadias S, et al. Sigmoid carcinoma incidentally discovered after perforation caused by an ingested chicken bone. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(1):153–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Terrace JD, Samuel J, Robertson JH, Wilson RG, Anderson DN. Chicken or the leg: sigmoid colon perforation by ingested poultry fibula proximal to an occult malignancy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(11):945–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Osler T, Stackhouse CL, Dietz PA, Guiney WB. Perforation of the colon by ingested chicken bone, leading to diagnosis of carcinoma of the sigmoid. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28(3):177–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yamashita K, Komohara Y, Uchihara T, Arima K, Uemura S, Hanada N, et al. A rare case of perforation of a colorectal tumor by a fish bone. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2022;15(3):598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McGregor DH, Liu X, Ulusarac O, Ponnuru KD, Schnepp SL. Colonic perforation resulting from ingested chicken bone revealing previously undiagnosed colonic adenocarcinoma: report of a case and review of literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zeidan Z, Lwin Z, Iswariah H, Manawwar S, Karunairajah A, Chandrasegaram MD. Unusual presentation of a sigmoid mass with chicken bone impaction in the setting of metastatic lung cancer. Case Rep Surg. 2019;2019:1016534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Velitchkov NG, Grigorov GI, Losanoff JE, Kjossev KT. Ingested foreign bodies of the gastrointestinal tract: retrospective analysis of 542 cases. World J Surg. 1996;20(8):1001–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Joglekar S, Rajput I, Kamat S, Downey S. Sigmoid perforation caused by an ingested chicken bone presenting as right iliac fossa pain mimicking appendicitis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maglinte DD, Taylor SD, Ng AC. Gastrointestinal perforation by chicken bones. Radiology. 1979;130(3):597–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kumar D, Venugopalan Nair A, Nepal P, Alotaibi TZ, Al-Heidous M, Blair Macdonald D. Abdominal CT manifestations in fish bone foreign body injuries: what the radiologist needs to know. Acta Radiol Open. 2021;10(7):20584601211026808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gore DG, Maharaj A, Doddridge N. Visual failure in the elderly and dysphagia. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013200628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fincher RK, Osgard EM. A case of mistaken identity: accidental ingestion of coins causing esophageal impaction in an elderly female. MedGenMed. 2003;5(2):3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this review are included in this article and its online supplementary material files. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.