Abstract

Radiologist interruptions, though often necessary, can be disruptive. Prior literature has shown interruptions to be frequent, occurring during cases, and predominantly through synchronous communication methods such as phone or in person causing significant disengagement from the study being read. Asynchronous communication methods are now more widely available in hospital systems such as ours. Considering the increasing use of asynchronous communication methods, we conducted an observational study to understand the evolving nature of radiology interruptions. We hypothesize that compared to interruptions occurring through synchronous methods, interruptions via asynchronous methods reduce the disruptive nature of interruptions by occurring between cases, being shorter, and less severe. During standard weekday hours, 30 radiologists (14 attendings, 12 residents, and 4 fellows) were directly observed for approximately 90-min sessions across three different reading rooms (body, neuroradiology, general). The frequency of interruptions was documented including characteristics such as timing, severity, method, and length. Two hundred twenty-five interruptions (43 Teams, 47 phone, 89 in-person, 46 other) occurred, averaging 2 min and 5 s with 5.2 interruptions per hour. Microsoft Teams interruptions averaged 1 min 12 s with only 60.5% during cases. In-person interruptions averaged 2 min 12 s with 82% during cases. Phone interruptions averaged 2 min and 48 s with 97.9% during cases. A substantial portion of reading room interruptions occur via predominantly asynchronous communication tools, a new development compared to prior literature. Interruptions via predominantly asynchronous communications tools are shorter and less likely to occur during cases. In our practice, we are developing tools and mechanisms to promote asynchronous communication to harness these benefits.

Keywords: Interruptions, Imaging productivity, Asynchronous communication, Reading room, Radiology workflow

Introduction

Interruptions are very common in the radiology reading room and are often necessary for patient care. Radiologists juggle multiple responsibilities alongside a high volume of cases. These responsibilities include offering consultation to providers, supporting radiology technologists, and discussing imaging findings with colleagues, among other tasks [1]. These interruptions can disrupt workflow and are especially detrimental to attention during active case readings. Interruptions during critical exam findings in radiology can negatively impact both radiologist concentration and patient safety. Even after the interrupting task is over, there is an inattention gap where radiologists are at increased risk for subsequent reading errors [2–4].

Historically, the primary methods of communication have been synchronous, such as phone calls or in-person conversations [5, 6]. Consequently, most of the research on interruptions in radiology has been focused on synchronous interruption modalities. Accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic and technology advancements, predominantly asynchronous methods of communication are now more widely available in healthcare systems, yet little is known about how these asynchronous interruptions impact radiology work.

Our study builds on existing literature on radiology workflow [1, 4, 7] to investigate the patterns, frequency, and severity of interruptions across reading rooms in the era of widespread use of predominantly asynchronous communication methods. Our goal is to better understand the evolving nature of radiology interruptions and the effects of the communication tools used. Our hypothesis is that compared to interruptions occurring through synchronous methods, interruptions via asynchronous methods reduce the disruptive nature of interruptions by requiring attention between cases (as opposed to during cases), being shorter, and less severe. Understanding the influence of the communication tools on the nature and effect of the interruption can help us proactively design better systems and workflow processes in the reading room.

Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review board. The study was performed in a mid-sized academic radiology department in multiple reading rooms including body, neuroradiology, and general reading rooms during regular business hours. Lunchtime and conference times were avoided.

Data Collection

Data collection was done through direct observation of a radiology attending or a radiology trainee for approximately 90-min session. Two medical students performed the observations with the consent of the radiologist. During each session, the student recorded the time stamp for starting each new case as well as the time stamp for the beginning and end of each interruption, and whether the interruption occurred during the reading of the case or between cases. The interruptions were categorized according to their type, method, relation to the study being read, source, task, and severity. The categories for classification were delineated, and then refined following an initial trial observation. Additional free text notes were recorded for some interruptions to provide additional contextual information.

This prospective study spanned the course of 14 nonconsecutive days. A total of 30 radiologists were observed including 14 residents, four fellows, and 12 attendings. Thirteen observation sessions were in the neurology reading room, 12 sessions in the body reading room, and five sessions in the general reading room.

Defining and Categorizing Interruptions

Synchronous communication methods included answered phone calls and in-person communication. Predominantly asynchronous communication included Microsoft Teams (Teams), email, or personal devices. Our primary study interest was interruptions arriving through phone, Teams, and, in-person. The timing of the interruption (during a case or between cases), the duration of the interruption, and the degree to which the radiologist disengaged from reading cases to address the interruption (severity) were recorded. The counting and categorization of the interruption was based on when the radiologist shifted attention to the interruption and not based on receiving a notification of the interruption. For example, a phone call to the reading room is not counted as an interruption unless the observed radiologist answers it. Similarly, a notification on the workstation is not considered an interruption, until the radiologist clicks on it and interacts with it. The scenario of an unplanned incoming voice calls on Teams is rare in our practice and did not occur during the observation sessions, but would be classified as a phone call if the radiologist answers it, since it was effectively equivalent to a phone call. Planned resident read outs whether in person or via Teams voice call are not categorized as interruption but are rather equivalent to starting a new case. For severity, interruptions causing radiologists to leave their desks or open a different patient exam in PACS were deemed more severe than interruptions causing computer disengagement or opening another application but not switching patient exam images. Table 1 details the categories for classification of interruptions.

Table 1.

Classification system of interruptions

| Timing | Typef | Method | Relation | Source | Task | Severity | Observation | Room |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During case | Internal | Phone | Related | Rad Resident | Consultation | Computer Disengagea | Resident | Abdomen |

| Between cases | External | In-person | Unrelated | Rad Attending | Question | Exam Disengageb | Fellow | Abdomen office |

| New case | Teams General | Rad tech | Support | Pacs_Disengagec | Attending | Neuro | ||

| Read out | Teams eConsulte | Non Rad Provider | Protocoling | Left Deskd | MSK General | |||

| End session | Patient | Break | Chest General | |||||

| Device | Other_Source | Communicate out | Peds General | |||||

| Paper | Research | |||||||

| Other_workstation | Presenting | |||||||

| Other Task |

aComputer disengagement: Shifting focus to something other than workstation computer but keeping current patient case on screen

bPACS Disengagement: Opening up another program besides PACS but keeping the current case read on the workstation computer

cExam Disengagement: Disengaging from current case exam and opening a different patient exam before finishing case read

dLeft Desk: Leaving desk to complete another task before finishing case read

eTeams eConsult: Are consultation arriving through teams using a homegrown solution

fType: In classifying interruptions based on type, the interruption was considered external if initiated outside of the radiologist and delivered to the radiologist to respond and was considered internal if initiated by the radiologist. For example, when the phone rings and the radiologist answers, it is an external interruption. If the radiologist lifts the phone and dials, it is an internal interruption initiated by the radiologist. The distinction was occasionally trickier when it comes to asynchronous methods, since it takes the observer some judgment to distinguish between a radiologist responding to an incoming message (external) or a radiologist initiating a conversation (internal). We were very keen on having our observer be a “fly on the wall” and minimize interaction between the observer and the radiologist. We have therefore analyzed our data both ways with and without considering the type

Methods and Data Analysis

The data was analyzed with respect to the overall number and rate of interruptions and the mean and median lengths of interruptions. Interruption by predominantly asynchronous and synchronous methods was compared with respect to the relative duration using 2-sample T-test. They were also compared with respect to their timing and severity using Z-test.

Results

The mean interruption length for the neuroradiology reading room was 2 min and 39 s, 1 min and 35 s for the body reading room, and 2 min and 9 s for the general reading room (Table 2). The mean interruption length for residents was 2 min and 22 s, attendings was 2 min and 1 s, and fellows was 1 min and 36 s (Table 3). Summary of the results is shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Summary of interruptions divided by reading room

| Neuroradiology room | Body reading room | General reading room | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interruptions/hour | 4.3 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 5.2 |

| Total raw interruptions no | 80 | 101 | 44 | 225 |

| Total time (hours) | 18.7 | 17.0 | 7.5 | 43.1 |

| Observational sessions | 13 | 13 | 5 | 31 |

| Mean interruption length (seconds) | 159 | 95 | 129 | 125 |

| Median interruption length (seconds) | 90 | 50 | 74 | 65 |

Table 3.

Comparison of interruptions between residents, attendings, and fellows

| Resident | Attending | Fellow | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interruptions/hour | 4.2 | 6.0 | 6.2 |

| Total raw interruptions no | 81 | 107 | 37 |

| Total time (hours) | 19.3 | 17.9 | 5.9 |

| Observational sessions | 14 | 13 | 4 |

| Mean interruption length (seconds) | 142 | 121 | 96 |

| Median interruption length (seconds) | 78 | 61 | 42 |

Approximately 43 h and 9 min of radiologist activity was observed, encompassing 225 interruptions. Interruption time constituted 7 h and 47 min (18% of radiologist time). The average interruption length lasted 2 min and 5 s with a median of 1 min and 5 s. The most common methods of interruptions were in-person (39.6%), phone (20.9%), or Microsoft Teams (19.1%) (Fig. 1). The breakdown of interruption by source of interruption and task performed by the radiologist is presented in Figs. 2 and 3.

Fig. 1.

Observation Breakdown by Interruption Method

Fig. 2.

Observation Breakdown by Source of Interruption

Fig. 3.

Observation Breakdown by Task

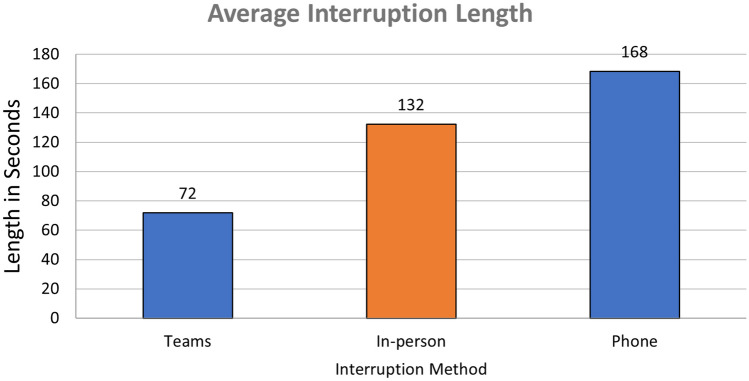

The mean interruption time was as follows: phone was 2 min and 48 s, in-person was 2 min and 12 s, and Teams was 1 min and 12 s. The median interruption time for phone was 1 min and 52 s, in-person was 1 min and 12 s, and Teams was 49 s. The interquartile range for phone interruptions was 127 s, in-person was 114 s, and Teams was 48 s. The phone interruptions (p < 0.01) and in-person interruptions (p < 0.01) were both found to be significantly longer than Teams interruptions (Figs. 4 and 5).

Fig. 4.

Average Interruption Length

Fig. 5.

Interruption Length Box Plot

With regard to the proportion of the studies classified as severe: in-person was 43.8%, phone was 31.9%, and Teams was 16.3%. In-person (p < 0.01) was found to be statistically more significant than Teams interruptions. However, when compared to Teams, phone interruption only approached statistical significance (p = 0.08) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Severe Interruptions Percentage

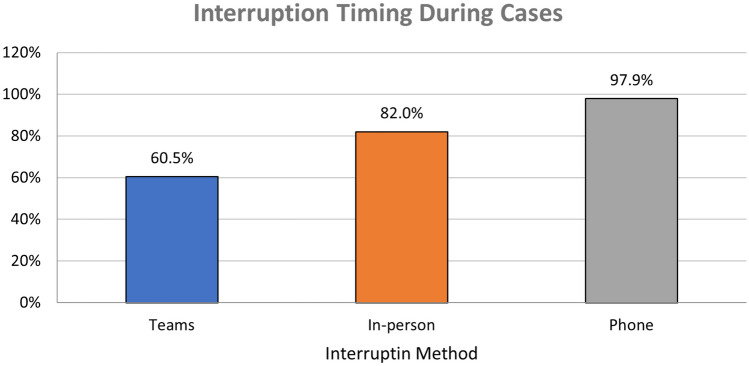

With regard to timing, the proportion of interruptions during cases was 60.5% for Teams, 82.0% for in-person, and 97.9% for phone. Both in-person (p < 0.01) and phone interruptions (p < 0.01) occurred statistically more during cases as compared to Teams interruptions (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Percentage of interruption occurring during cases

The vast majority of interruptions are not related to the case being read by the radiologist (Teams 86.0%, in-person 80.9%, and phone 80.9%), and these differences were not statistically significant. Likewise the majority of interruptions were external (meaning not initiated by the radiologist) with no statistical different between the methods (Teams 62.8%, in-person 74.2%, and phone 78.7%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary comparison of the interruption methods

| All methods | Teams | In-person | Phone | Team vs in-person | Teams vs phone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | 225 | 43 | 89 | 47 | NA | NA |

| Percentage of overall interruption | 100.0% | 19.1% | 39.6% | 20.9% | NA | NA |

| Mean duration in seconds | 125 | 72 | 132 | 168 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 |

| Median duration in seconds | 65 | 49 | 72 | 112 | NA | NA |

| Interquartile range (Q3-Q1) in seconds | 102 | 48 | 114 | 127 | N/A | N/A |

| Percent severe | 28.0% | 16.3% | 43.8% | 31.9% | p < 0.01 | p = 0.08 |

| Percent during case | 82.2% | 60.5% | 82.0% | 97.9% | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 |

| Percent unrelated | 76.4% | 86.0% | 80.9% | 80.9% | p = 0.46 | p = 0.51 |

| Percent external | 61.8% | 62.8% | 74.2% | 78.7% | p = 0.18 | p = 0.1 |

| Percent during case for external only | 88.5% | 74.1% | 89.4% | 97.3% | p = 0.06 | p < 0.01 |

Discussion

Interruptions in the reading room underpin an age-old dilemma that is growing increasingly pertinent. On one hand, the role of the radiologist as an imaging consultant and a steward of medical imaging resources is increasingly emphasized by radiology societies particularly as we anticipate the era of value-based healthcare. On the other hand, repeated interruptions can be very disruptive to workflow and are harder to manage in the light of the increasing productivity demands. Solving this dilemma requires an in-depth understanding of the characteristics of the reading room interruptions. Our study offers a detailed analysis of interruptions and demonstrates many commonalities with the existing literature on the topic. For example, compared to a prior observational study performed in a comparable setting and with similar study design in 2016 [4], the frequency and duration of interruptions were comparable (e.g., The mean duration is 2 min and 5 s in the current study, compared to 2 min and 24 s in the prior). Similar patterns were also observed in other studies performed in similar day time reading room settings [1, 6, 8, 9]. The key difference between our study and the prior studies is the increasing use of modern predominantly asynchronous communication tools which were not observed in the prior studies [1, 6, 8, 9]. The adoption of these tools in our health system, further propelled by the COVID-19 pandemic, is reflective of a broader trend in healthcare, persisting post pandemic after the return to routine workflows in the reading room [10]. In our study, Teams accounted for 19% of all interruptions. We have shown that interruptions occurring via predominantly asynchronous tools are less disruptive to workflow. Specifically, they are more likely to require attention between cases and are shorter in duration. Past research on interruption supports the notion that interruptions between tasks and shorter interruptions are less disruptive [11, 12]. Thus, asynchronous communication that shifts interruptions to the time interval between cases mitigates the most negative effects of interruptions on workflow and attention. Drawing from literature on interruptions in radiology and in other fields, interruptions during cases are likely to incur an additional time penalty in refocusing attention on the interrupted task [1, 11, 13, 14] and can theoretically increase the likelihood of error [12, 13, 15, 16]. According to a review by Li et al. on interruptions and its patient safety implications, “interruptions occurring during execution have been consistently shown to be more disruptive than those occurring in between” [17]. The interruptions via predominantly asynchronous communication tools in our study were also less severe defined by the radiologist needing to switch to a different screen or leave their desk. Research on interruptions also shows that when people are required to direct their attention completely away from their primary task (i.e., reading the case) to the interrupting task, there can be significant effects on spatial memory, and returning to the primary task can be particularly difficult under these conditions [18].

Our results suggest that shifting communication to predominantly asynchronous methods would reduce the disruptive nature of interruptions. There is a growing adoption of such methods of communications which presents an opportunity to enhance the radiology consultative services while reducing disruptions. There is limited radiology literature about the subject, but a recent article highlights the importance of exploring of electronic consultations in radiology [19]. In our institution, we have developed an electronic consultation solution that delivers requests for consultation asynchronously to the radiologist via Teams. A survey performed after the initial pilot of the tool indicated that both referring providers and radiologists expressed a positive initial perception of the solution with the majority considering it superior to traditional phone calls [20]. A subsequent unpublished survey data performed as part of continuous quality assurance confirmed the same positive reaction to the solution after 2 years of usage and 8–10-fold increase in users and in participating hospitals within our healthcare system. Sevenster et al. have developed an asynchronous communication solution that aims to reduce avoidable interruptions caused by technologist-radiologist communication and similarly found positive initial perception of the tool among radiologist and technologists [21].

Our study had several limitations. Our study was limited to an academic radiology department during regular reading room hours. While we believe that the patterns observed can be generalized to community radiology practices, our study does not assess or empirically support that. Furthermore, the radiologists we observed were aware of this study and that they were being observed. This may have theoretically influenced their workflow and their handling of interruptions. To mitigate that, the observers were instructed to eliminate or minimize any communication with the observed radiologist. The observed radiologists were also not told the hypothesis of the study, to minimize or eliminate any conscious or subconscious change in how they handle interruptions.

Using predominantly asynchronous communication methods, radiologists can better time interruptions, thus reducing concentration impairment and improving patient safety. In our practice, we are developing mechanisms and tools to promote asynchronous communication and harness these benefits.

The authors declare that they had full access to all of the data in this study, and the authors take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Shah SH, Atweh LA, Thompson CA, Carzoo S, Krishnamurthy R, Zumberge NA. Workflow Interruptions and Effect on Study Interpretation Efficiency. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2022;51:848–51. 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2022.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eyrolle H, Cellier JM. The effects of interruptions in work activity: field and laboratory results. Appl Ergon 2000;31:537–43. 10.1016/S0003-6870(00)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee MH, Schemmel AJ, Pooler BD, Hanley T, Kennedy TA, Field AS, et al. Workflow Dynamics and the Imaging Value Chain: Quantifying the Effect of Designating a Nonimage-Interpretive Task Workflow. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2017;46:275–81. 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ratwani RM, Wang E, Fong A, Cooper CJ. A Human Factors Approach to Understanding the Types and Sources of Interruptions in Radiology Reading Rooms. J Am Coll Radiol 2016;13:1102–5. 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kansagra AP, Liu K, Yu J-PJ. Disruption of Radiologist Workflow. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2016;45:101–6. 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watura C, Blunt D, Amiras D. Ring Ring Ring! Characterising Telephone Interruptions During Radiology Reporting and How to Reduce These. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2019;48:207–9. 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu J-PJ, Kansagra AP, Mongan J. The radiologist’s workflow environment: evaluation of disruptors and potential implications. J Am Coll Radiol 2014;11:589–93. 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith EA, Schapiro AH, Smith R, O’Brien SE, Smith SN, Eckerle AL, et al. Increasing Median Time between Interruptions in a Busy Reading Room. Radiographics 2021;41:E47–56. 10.1148/rg.2021200094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schemmel A, Lee M, Hanley T, Pooler BD, Kennedy T, Field A, et al. Radiology Workflow Disruptors: A Detailed Analysis. J Am Coll Radiol 2016;13:1210–4. 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yacoub JH, Swanson CE, Jay AK, Cooper C, Spies J, Krishnan P. The Radiology Virtual Reading Room: During and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Digit Imaging 2021:1–12. 10.1007/s10278-021-00427-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adamczyk PD, Bailey BP. If not now, when? Proc SIGCHI Conf Hum Factors Comput Syst 2004:271–8. 10.1145/985692.985727. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monk CA, Trafton JG, Boehm-Davis DA. The Effect of Interruption Duration and Demand on Resuming Suspended Goals. J Exp Psychol Appl 2008;14:299–313. 10.1037/A0014402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wynn RM, Howe JL, Kelahan LC, Fong A, Filice RW, Ratwani RM. The Impact of Interruptions on Chest Radiograph Interpretation. Acad Radiol 2018;25:1515–20. 10.1016/j.acra.2018.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drew T, Williams LH, Aldred B, Heilbrun ME, Minoshima S. Quantifying the costs of interruption during diagnostic radiology interpretation using mobile eye-tracking glasses. J Med Imaging 2018;5:1. 10.1117/1.JMI.5.3.031406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balint BJ, Steenburg SD, Lin H, Shen C, Steele JL, Gunderman RB. Do Telephone Call Interruptions Have an Impact on Radiology Resident Diagnostic Accuracy? Acad Radiol 2014;21:1623–8. 10.1016/j.acra.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grundgeiger T, Sanderson P. Interruptions in healthcare: Theoretical views. Int J Med Inform 2009;78:293–307. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li SYW, Magrabi F, Coiera E. A systematic review of the psychological literature on interruption and its patient safety implications. J Am Med Informatics Assoc 2012;19:6–12. 10.1136/amiajnl-2010-000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ratwani RM, Trafton JG. Spatial memory guides task resumption. Vis Cogn 2008;16:1001–10. 10.1080/13506280802025791. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suresh K, Hill PA, Kahn CE, Schnall MD, Rosen MA, Zafar HM, et al. Quality Improvement Report: Design and Implementation of a Radiology E-Consult Service. Radiographics 2023;43:e230139. 10.1148/rg.230139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yacoub JH, Bourne MD, Krishnan P. The Virtual Radiology Reading Room: Initial Perceptions of Referring Providers and Radiologists. J Digit Imaging 2023;36:787–93. 10.1007/s10278-022-00745-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sevenster M, Hergaarden K, Hertgers O, Nguyen D, Wijn V, Vlachomitrou AS, et al. Design and Perceived Value of a Novel Solution for Asynchronous Communication in Radiology. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2024;53:96–101. 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2023.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]