Abstract

Recurrences are frequent in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) despite high remission rates with treatment, leading to considerable morbidity. This study aimed to develop a prediction model for NPC survival by harnessing both pre- and post-treatment magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) radiomics in conjunction with clinical data, focusing on 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) as the primary outcome. Our comprehensive approach involved retrospective clinical and MRI data collection of 276 eligible NPC patients from three independent hospitals (180 in the training cohort, 46 in the validation cohort, and 50 in the external cohort) who underwent MRI scans twice, once within 2 months prior to treatment and once within 10 months after treatment. From the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images before and after treatment, 3404 radiomics features were extracted. These features were not only derived from the primary lesion but also from the adjacent lymph nodes surrounding the tumor. We conducted appropriate feature selection pipelines, followed by Cox proportional hazards models for survival analysis. Model evaluation was performed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, the Kaplan–Meier method, and nomogram construction. Our study unveiled several crucial predictors of NPC survival, notably highlighting the synergistic combination of pre- and post-treatment data in both clinical and radiomics assessments. Our prediction model demonstrated robust performance, with an accuracy of AUCs of 0.66 (95% CI: 0.536–0.779) in the training cohort, 0.717 (95% CI: 0.536–0.883) in the testing cohort, and 0.827 (95% CI: 0.684–0.948) in validation cohort in prognosticating patient outcomes. Our study presented a novel and effective prediction model for NPC survival, leveraging both pre- and post-treatment clinical data in conjunction with MRI features. Its constructed nomogram provides potentially significant implications for NPC research, offering clinicians a valuable tool for individualized treatment planning and patient counseling.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10278-024-01109-7.

Keywords: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Prognosis, Artificial intelligence, Magnetic resonance radiomics

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a relatively rare malignancy, with an annual incidence rate of approximately 1 in every 100,000 cases, accounting for 0.7% of neoplasms worldwide. It is particularly prevalent in the Southeast Asian region where it is considered endemic [1, 2]. According to the differentiation of tumor cells, the WHO classified NPC into three types: nonkeratinizing carcinoma (differentiated or undifferentiated), keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma [3]. Among these, in epidemic regions, differentiated nonkeratinizing NPC predominates [4], with over 70% of the patients being diagnosed in stages II, III, and IV when found due to occult manifestations of stage I [5, 6] (TNM staging system, AJCC 8th Edition [7]). Most cases of NPC show an effective response to treatment with radiotherapy for early-stage NPC and concurrent chemoradiotherapy for advanced NPC as recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network [8]. Nevertheless, the diagnosis and treatment are frequently initiated at an advanced stage and the outcomes of NPC patients remain unsatisfactory, with nearly 30% of cases suffering treatment failure [5, 6, 9–11].

Optimum imaging is crucial for staging and treatment planning for NPC, of which magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), compared with CT, is the preferred method for primary tumor delineation because of its high resolution on soft tissue [9]. As time progresses, a novel era of technology in the 2010s is transforming how medical imaging is utilized—artificial intelligence (AI) [12]. Converting medical imaging into measurable characteristics presents a dependable methodology for evaluating the scope of neoplastic disease and subsequently enhances traditional clinical prognosticators concerning locoregional control (LRC) and overall survival (OS). Nevertheless, the utilization of AI in predicting the prognosis of NPC patients has been relatively understudied, primarily owing to the low incidence of NPC and its limited distribution [13]. Various models, predominantly employing machine learning algorithms and statistical nomograms, were explored, encompassing those relying on clinical data, pre- and post-treatment radiomics, and integrated approaches combining both [14–18]. It shows that the integration of AI and radiomics offers a promising avenue for refining prognostic accuracy [12]. However, there is a need for an enhancement in the model as it has been observed that, in most instances, only pre-treatment MR images have been employed without taking into account any discrepancies in post-treatment images [19]. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, existing studies have not emphasized the utilization of integrating clinical data retrieved both before and after treatments. Numerous clinical parameters have been examined for their association with or contribution to disease progression [20–23]. Consequently, this approach could provide valuable insights into the dynamic changes in patient status over the course of treatment and may enhance the predictive accuracy of prognostic models for NPC survival. We postulated that a more refined profiling of tumor-related characteristics in NPC patients, achieved by incorporating radiomics with clinical data, could yield an augmented prediction of patient survival [24, 25]. Diverging from prior research, we embarked on a novel exploration of both clinicopathological and hematological data, collectively referred to as clinical data, along with MRI features obtained from both pre- and post-treatment stages.

In this research, we aim to assess the predictive efficacy of various clinical and radiomics factors for survival models in a substantial cohort comprising non-metastatic NPC cases treated with radiation therapy alone or combined with chemotherapy across three distinguished hospitals in Taiwan: Taipei Medical University Hospital, Shuangho Hospital, and Taipei Municipal Wanfang Hospital.

Materials and Methods

Data Acquisition

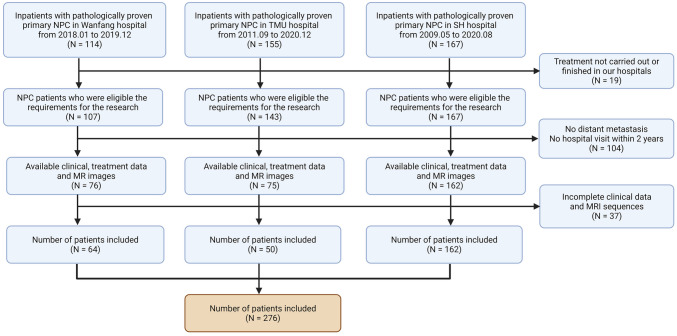

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Wanfang Hospital (IRB no. N202112049), and the informed consent from patients was exempted. We retrospectively collected radiomics and clinical data of newly diagnosed NPC patients between March 2008 to December 2020 from Taipei Medical University Hospital, Shuang-Ho Hospital, and Taipei Municipal Wanfang Hospital in Taiwan. The flowchart of patient screening is presented in Fig. 1. Our inclusion criteria consisted of the following: histologically proven primary NPC; absence of distant metastasis; regular follow-up within at least 2 years after diagnosis; available oncologic treatment summary; vital status with time of recurrence, including local and distant metastases ascertained based on CT/MRI with progression-free survival at 3 years (3-year PFS [26, 27]) as the observation endpoint; availability of relevant clinical parameters such as type of NPC cancer, clinical TNM tumor staging, BMI, sex, age at diagnosis, and blood test values. Exclusion criteria included patients’ refusal or incomplete hospital treatment plan, insufficient clinical or MRI imaging data, surgical treatment plans involved, and irregular follow-up (less than every 3 months for 2 years).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart on clinical and MRI data collection process of eligible NPC patients

Patients were staged according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system [28]. A total of 286 patients were eligible for this study. Of these, 7 NPC patients received radiation without chemotherapy regardless of advanced age and/or other factors; 58 patients received concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT), and none of them received adjuvant chemotherapy (AC). Clinical data and MRIs were acquired once within a 2-month window prior to treatment initiation and once within 10 months following treatment completion. Specifically, patients’ data were collected at the latest pre-treatment and post-treatment time points, designated to occur 1 month before treatment initiation and 2 months afterward. The timing for post-treatment MRI was selected according to the standardized follow-up schedule recommended for NPC patients. Nonetheless, occasional deviations occurred, with data collection extending beyond the 2-month post-treatment window, yet all such instances occurred within a timeframe of less than 10 months post-treatment. The time interval between the date of cancer diagnosis and the last outpatient examination or death was referred to as survival time. We subsequently randomly partitioned the datasets from Wanfang Hospital and Shuang-Ho Hospital into two different cohorts: training (N = 180), testing (N = 46), and employing random stratified sampling with a specified test size of 20%. The dataset from Medical University Hospital served as a validation cohort (N = 50). The training cohort was utilized to develop the survival model, while the testing and validation cohorts were employed to assess the performance of the model.

Preprocessing MR Images

On 1.5 T MRI scanners (GE Healthcare, Iowa, USA), patients had their nasopharyngeal and neck examined. Subjects were placed supine, head first, arms alongside the body (head-first supine position). The obtained postcontrast T1-weighted MRIs were acquired in the axial plane and saved in DICOM format.

The primary tumor and regional lymph node were next manually segmented via the 3D Slicer (http://www.slicer.org) as the Region of Interest (ROI). Accurate contouring in post-treatment MRI is complicated by anatomical distortion caused by radiation, which makes it particularly challenging to identify tumors and lymph nodes [29–32]. Moreover, similar challenges are encountered in radiographic evaluation, and currently, there is no consensus on the optimal imaging modality for post-treatment assessment or the most accurate method for delineating boundaries between tumors and lymph nodes following irradiation. As a result, the physician’s experience is paramount in determining the ROIs for post-treatment lesions to achieve optimal outcomes. Consequently, vigilance should be exercised as necessary to ensure accurate delineation, followed by a consensus on the anatomic limits. In our study, an otolaryngologist and two radiologists with more than 10 years of experience were involved in the process. The delineation of tumors and lymph nodes was strictly based on their experience, devoid of any clinical information and biopsy evidence from the patient. This standardized process, guided by a consensus guideline [31] and augmented by cross-examination, ensured meticulous and precise interpretation of the imaging data. The basic criteria for lymph node delineation included retropharyngeal lymph nodes exceeding 5 mm or cervical lymph nodes surpassing 10 mm in the shortest diameter. Additionally, the presence of three or more contiguous and confluent lymph nodes with a shortest diameter of 8–10 mm, lymph nodes of any size displaying central necrosis or a contrast-enhanced rim, or those demonstrating extracapsular extension were also considered. Pyradiomics version 2.0.0 was implemented to extract ROIs, which can be categorized into 4 classes: shape-based class, first-ordered intensity class, texture-based class, and wavelet-based class. In each ROI of the tumor/nodes, 851 radiomics were obtained with a custom bin width of 25.

Survival Predictors Identification

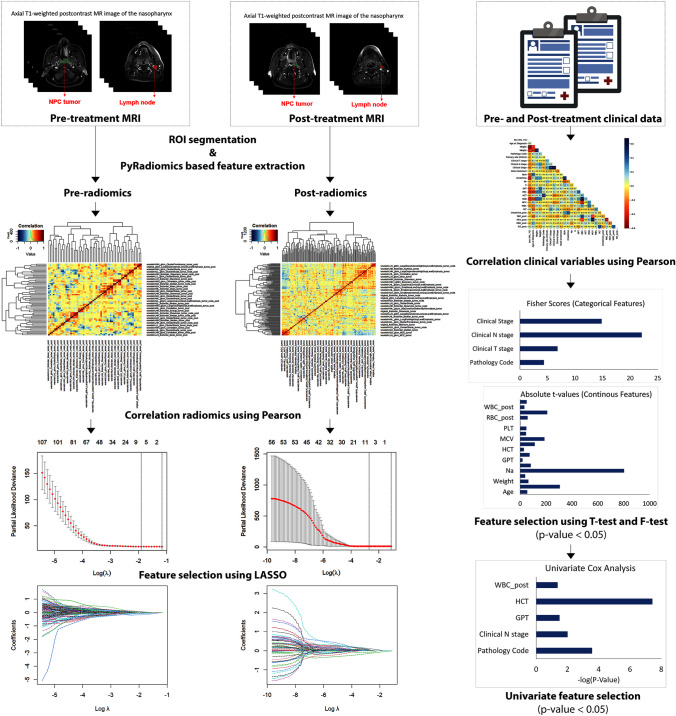

Pearson’s correlation was applied to each clinical, pre-, and post-radiomics training set with a setting of 0.75 to minimize highly correlated variables. The filtered clinical variables were then split into two groups: categorical or continuous variables to perform F-test or T-test, respectively. Following statistical analysis, factors exhibiting a significant correlation with survival (p-value < 0.05) were retained for inclusion in univariate Cox regression analysis to assess the relationship between each potential predictor and the hazard of an event. Only significant clinical predictors with a p-value < 0.05 were included in our model. Radiomics variables were included in the LASSO regression model with λ-based optimization with tenfold cross-validation. Variables with non-zero coefficients after the model performance were referred to as radiomics predictors and included in our model. The workflow description for feature selection is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Clinical and radiomics feature extraction workflow in this study. Radiomics features were extracted from ROI segmentations of pre- and post-treatment MRI images by PyRadiomics and then screened for highly correlated variables using Pearson’s before being input into LASSO regression (a tenfold cross-validation was applied to select the optimal penalty parameter λ, resulting in λ = 0.1486442 for pre-radiomics and λ = 0.06743348 for post-radiomics). Clinical variables underwent a similar screening process through the Pearson correlation analysis and were subsequently divided into two groups: categorical and continuous variables. These variables were analyzed to determine their statistical significance on survival rate using the F-test for categorical variables and the T-test for continuous variables. The selected variables were then evaluated for univariate survival association

Model Construction

Multivariate Cox regression analysis was applied on clinical and radiomics predictors for the binary outcome of survival. Each patient’s risk score was derived from the regression coefficients, involving a linear combination of the predictors (provided in Table 2). The study proposed models utilizing clinical predictors alone, radiomics predictors alone, a fusion of pre- and post-treatment radiomics predictors, and an integrated model incorporating both clinical predictors and radiomics features. Models were assessed for their predictive performance by computing the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) with bootstrapping and Harrell’s C-index for a 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) on training, testing, and validation cohort. A nomogram was created to predict 3-year and 5-year survival times, serving as a practical tool for enhancing NPC local control rates [33], using risk scores generated by the best-performing model. Calibration curves were then utilized to evaluate the precision of survival time predictions.

Table 2.

Formulas concerning the risk score for a clinical model; pre-radiomics model; pre- and post-radiomics model; and clinical, pre-, and post-radiomics model

| Selected features | Coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Formulas for calculating clinical, pre-, and post-treatment risk score | (2) Formulas for calculating clinical risk score | Pathology code | * | 0.0012918 | |

| Clinical N stage | * | −0.0219753 | |||

| GPT | * | −0.0148756 | |||

| HCT | * | 0.0222087 | |||

| WBC_post | * | 0.1037531 | |||

| (3) Formulas for calculating pre- and post-treatment risk score | (4) Formulas for calculating pre-treatment risk score | wavelet-LLH_firstorder_Skewness_tumor | * | 0.7077376 | |

| wavelet-HLL_glcm_Correlation_tumor | * | −0.6199902 | |||

| wavelet-HHL_glcm_Correlation_tumor | * | −2.2239969 | |||

| wavelet-LLL_firstorder_Kurtosis_tumor | * | 0.0380356 | |||

| wavelet-LHH_glszm_LargeAreaLowGrayLevelEmphasis_tumor_node | * | 8.482E-06 | |||

| wavelet-HHH_ngtdm_Busyness_tumor_node | * | −0.0001618 | |||

| (5) Formulas for calculating post-treatment risk score | wavelet-LLH_firstorder_Skewness_tumor_post | * | 0.9250657 | ||

| wavelet-LLH_glcm_ClusterShade_tumor_post | * | 1.157E-05 | |||

| wavelet-LHH_glcm_Correlation_tumor_post | * | 1.0702511 | |||

| wavelet-HLL_firstorder_Median_tumor_post | * | 0.0109764 | |||

| wavelet-HLL_glszm_LargeAreaLowGrayLevelEmphasis_tumor_post | * | −6.97E-05 | |||

| wavelet-HLH_glcm_ClusterShade_tumor_post | * | 0.0039309 | |||

| wavelet-HHL_glcm_ClusterProminence_tumor_post | * | 0.0015269 | |||

| wavelet-HLL_glszm_LargeAreaLowGrayLevelEmphasis_tumor_node_post | * | 0.000576 | |||

The value of each predictor is multiplied by its corresponding coefficient. This multiplication represents the contribution of that predictor to the predicted outcome. The asterisk (*) is used to denote this multiplication operation.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism (version 9, Massachusetts, USA), Python, and R software. Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Differences between groups were compared using a t-test or Fisher’s exact test. The Bland–Altman plot was employed to evaluate interobserver agreement in manual segmentation, with a comprehensive evaluation conducted using metrics such as the Pearson correlation coefficient (r), standard error of the estimate (SEE), mean absolute difference (MAD), root mean square error (RMSE), and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). The Cox regression method was employed for both univariate and multivariate analyses. The LASSO Cox model was built based on the glmnet package. Pairwise comparisons of AUC values were conducted using the Hanley and McNeil method, computing significance values to assess variations in predictive performance across cohorts. Precision, recall, F1 score, accuracy, and the area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC) were computed to evaluate the performance of the predictive models. Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier and compared using the log-rank test. The nomogram and calibration curves were generated using the rms package. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical Characteristics

The flow diagram for patient selection of this study is shown in Fig. 1. A total of 276 patients met the criteria for inclusion in the study. Training (N = 180) and testing cohorts (N = 46) included patients from Wanfang and Shuangho hospitals. An external cohort consisting of 50 patients from Taipei Medical University Hospital was utilized to validate the effectiveness of the model. The clinical data of all patients are summarized in Table 1. Significant differences (p-value < 0.05) in the TMN stage, N category, GOT, and follow-up time were observed between the training, testing, and validation cohorts. Men in midlife constituted the majority of NPC cases, which were discovered at stages III–IV of squamous nonkeratinizing cell carcinoma. The median follow-up time was 3–5 years after treatment, during which 46 deaths were recorded within the first 2–3 years.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinicopathologic characteristics of NPC patients

| Training cohort (n = 180) | Testing cohort (n = 46) | External cohort (n = 50) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, no. (%) | 0.231 | |||

| Men | 140 (77.78%) | 35 (76.09%) | 33 (66.00%) | |

| Women | 40 (22.22%) | 11 (23.91%) | 17 (34.00%) | |

| Age, mean (± SD), y | 51.63 (± 11.73) | 52.05 (± 13.11) | 49.64 (± 14.47) | 0.415 |

| Height, mean (± SD), cm | 164.73 (± 8.12 | 164.85 (± 7.90) | 164.93 (± 10.11) | 0.957 |

| Weight, mean (± SD), kg | 68.88 (± 14.74) | 68.71 (± 12.69) | 66.15 (± 14.23) | 0.391 |

| BMI | 25.25 (± 4.37) | 25.17 (± 3.71) | 24.35 (± 4.39) | 0.183 |

| TMN stage*, no. (%) | 0.037 | |||

| I | 13 (7.22%) | 1 (2.17%) | 4 (8.00%) | |

| II | 38 (21.11%) | 8 (17.39%) | 5 (10.00%) | |

| III | 66 (36.67%) | 17 (36.96%) | 13 (26.00%) | |

| IV | 63 (35.00%) | 20 (43.48%) | 28 (56.00%) | |

| T stage*, no. (%) | 0.136 | |||

| T1 | 52 (28.89%) | 9 (19.57%) | 20 (40.00%) | |

| T2 | 49 (27.22%) | 9 (19.57%) | 6 (12.00%) | |

| T3 | 37 (20.56%) | 12 (26.09%) | 9 (18.00%) | |

| T4 | 42 (23.33%) | 16 (34.78%) | 15 (30.00%) | |

| N stage*, no. (%) | 0.023 | |||

| N0 | 23 (12.78%) | 2 (4.35%) | 4 (8.00%) | |

| N1 | 62 (34.44%) | 15 (32.61%) | 12 (24.00%) | |

| N2 | 65 (36.11%) | 22 (47.83%) | 16 (32.00%) | |

| N3 | 30 (16.67%) | 7 (15.22%) | 18 (36.00%) | |

| Pathology code (type) **, no. (%) | 0.0757 | |||

| 80723 | 161 (89.44%) | 39 (84.78%) | 49 (98.00%) | |

| 80203 | 9 (5.00%) | 4 (8.70%) | 1 (2.00%) | |

| 80713 | 5 (2.78%) | 2 (4.35%) | ||

| 80103 | 3 (1.67%) | 1 (2.17%) | ||

| 80413 | 1 (0.56%) | |||

| 80703 | 1 (0.56%) | |||

| BUN, mean (± SD), mg/dL | 13.06 (± 4.22) | 12.69 (± 3.85) | 13.36 (± 3.58) | 0.476 |

| Na, mean (± SD), mmol/L | 138.73 (± 2.37) | 138.90 (± 2.39) | 138.30 (± 2.54) | 0.652 |

| K, mean (± SD), mmol/L | 3.91 (± 0.35) | 3.90 (± 0.36) | 4.06 (± 0.44) | 0.163 |

| GPT, mean (± SD), U/L | 28.71 (± 18.98) | 28.42 (± 23.04) | 24.48 (± 17.14) | 0.203 |

| GOT, mean (± SD), U/L | 24.77 (± 11.10) | 24.26 (± 13.14) | 21.13 (± 6.87) | 0.023 |

| Creatinine, mean (± SD), mg/dL | 0.83 (± 0.21) | 0.81 (± 0.16) | 0.81 (± 0.25) | 0.785 |

| RBC, mean (± SD), × 106/µL | 4.67 (± 0.50) | 4.67 (± 0.85) | 4.65 (± 0.65) | 0.796 |

| HCT, mean (± SD), % | 35.22 (± 15.26) | 35.92 (± 14.59) | 40.31 (± 4.71) | 0.870 |

| HGB, mean (± SD), mg/dL | 14.15 (± 1.48) | 13.92 (± 1.62) | 13.73 (± 1.67) | 0.194 |

| MCV, mean (± SD), fL | 89.42 (± 5.89) | 89.10 (± 8.37) | 87.37 (± 7.07) | 0.223 |

| WBC, mean (± SD), × 103/µL | 7.15 (± 1.86) | 7.29 (± 1.94) | 7.16 (± 2.71) | 0.726 |

| PLT, mean (± SD), × 103/µL | 252.76 (± 73.03) | 241.48 (± 50.33) | 247.52 (± 56.86) | 0.831 |

| Creatinine_post, mean (± SD), mg/dL | 0.92 (± 0.25) | 0.95 (± 0.28) | 0.86 (± 0.25) | 0.253 |

| RBC_post,mean (± SD), × 106/µL | 3.85 (± 0.55) | 3.76 (± 0.66) | 3.85 (± 0.64) | 0.563 |

| HCT_post, mean (± SD), % | 30.56 (± 12.33) | 30.47 (± 11.55) | 35.64 (± 4.91) | 0.120 |

| HGB_post, mean (± SD), mg/dL | 12.35 (± 1.48) | 11.82 (± 1.66) | 12.23 (± 1.70) | 0.114 |

| MCV_post, mean (± SD), fL | 93.84 (± 5.36) | 92.81 (± 8.06) | 93.36 (± 6.57) | 0.546 |

| WBC_post, mean (± SD), × 103/µL | 4.85 (± 1.57) | 4.81 (± 1.77) | 4.60 (± 1.84) | 0.219 |

| PLT_post, mean (± SD), × 103/µL | 216.43 (± 52.17) | 208.57 (± 58.06) | 204.48 (± 62.39) | 0.083 |

| Follow-up time, mean (± SD), y | 5.50 (± 3.20) | 5.46 (± 3.27) | 3.73 (± 2.01) | 0.003 |

| Therapeutic regimens, no. (%) | 0.256 | |||

| RT | 23 (12.78%) | 2 (4.35%) | 5 (10.00%) | |

| CCRT | 157 (87.22%) | 44 (95.65%) | 45 (90.00%) | |

| Survival, no. (%) | 0.530 | |||

| Alive | 153 (85.00%) | 36 (78.26%) | 41 (82.00%) | |

| Dead | 27 (15.00%) | 10 (21.74%) | 9 (18.00%) |

BUN blood urea nitrogen, Na sodium, K potassium, GTP glutamic pyruvic transaminase, GOT glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase, RBC red blood cell, HCT hematocrit, HGB hemoglobin, MCV mean corpuscular volume, WBC white blood cells, PLT platelet, RT radiation therapy, CCRT concurrent chemoradiotherapy

*according to 7th AJCC stage system; ** according to Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT): 80723 (Squamous cell carcinoma, nonkeratinizing), 80203 (Carcinoma, undifferentiated NOS), 80703 (Squamous cell carcinoma, NOS), 80713 (Squamous cell carcinoma, keratinizing NOS), 80413 (Small cell carcinoma NOS), 80103 (Heterotopia-associated carcinoma); Blood urea nitrogen (BUN), Sodium (Na), Potassium (K), Glutamic Pyruvic Transaminase (GTP), Glutamic-Oxaloacetic Transaminase (GOT), Red blood cell (RBC), Hematocrit (HCT), Hemoglobin (HGB), Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV), White blood cells (WBC), Platelet (PLT), Radiation therapy (RT), Concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT)

The correlations between retrieved clinical data were calculated. A total of 31 variables were included in the analysis and 4 highly correlated variables were excluded: GOT, HCT_post, HGB_post, and BMI. The remaining 26 variables were split into two groups for the F-test and T-test analyses, consisting of 7 categorical variables and 19 continuous variables, respectively (Fig. S1, Appendix). The survival outcome of NPC patients was found to be highly associated with a total of 22 variables, which were subsequently incorporated in the univariate Cox regression analysis to determine the association between survival and survival time. Significant variables (p-value < 0.05) included the pathology code, clinical N stage, GPT, HCT, and WBC_post (Table S1, Appendix). The risk scores for the clinically relevant models were then calculated using coefficients of these variables in a multivariate Cox regression analysis (Table 2). The general workflow for selecting clinical predictors is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Radiomics Signature

Extracted from pre-treatment axial T1-weighted postcontrast MRIs of the nasopharynx were 1702 features, including 851 features derived from segmented tumors and/or an equivalent number from segmented lymph nodes. Similarly, post-treatment extracted radiomics features gave 851 features for tumors and/or 851 features for nodes, adding up to 3404 radiomics features for each NPC patient in total. In light of the challenges posed by the unclear boundaries of delineated ROIs on post-treatment MRIs, we conducted a Bland–Altman analysis (Fig. S2, Appendix), revealing a robust positive correlation (r = 0.81) between observer 1 and observer 2 in the manual segmentation. While the moderate agreement (ICC = 0.664) signified a degree of consistency in their measurements, it also acknowledged the presence of variability (MAD = 0.025, RMSE = 0.682, SEE = 1.156), indicating that although their measurements are related, they may not always be identical.

Each set of pre-radiomics or post-radiomics was individually analyzed following the same workflow, illustrated in Fig. 2. After the Pearson analysis, 135 pre-radiomics features and 59 post-radiomics features with low intra-feature correlations were retained and subjected to the LASSO-Cox regression analysis to identify potential prognostic predictors (Figs. S3 and S4, Appendix). Six and eight predictors of the pre- and post-radiomics features were retained with non-zero coefficients after the analysis (provided in Table S2, Appendix). They were subsequently subjected to multivariate Cox regression analysis to compute the risk scores for each patient (Table 2).

Model Construction

We constructed five models, comprising three that exclusively utilized clinical predictors and pre- and post-radiomic predictors, one integrating pre- with post-radiomics predictors, and another integrating clinical with pre- and post-radiomic predictors. Risk scores for each model were calculated from relevant selected features using multivariate regression analysis (Table 2).

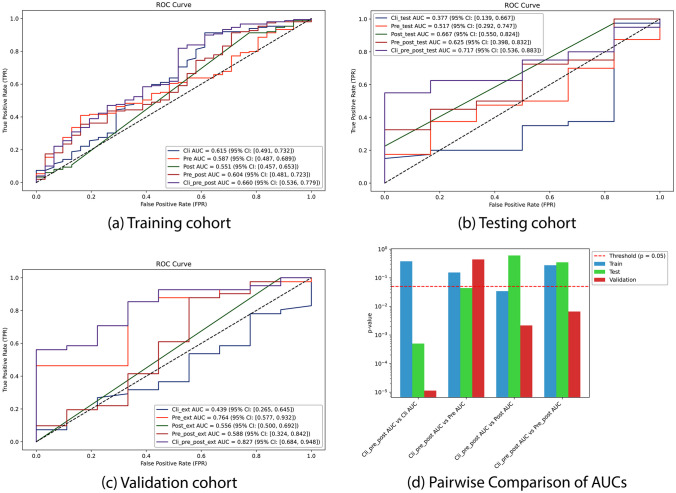

The results of model performances, depicted through ROC curves based on the actual survival status of individual NPC patients, across three datasets (training, testing, and validation cohorts), are illustrated in Fig. 3. The utilization of exclusively predictors exhibited poor predictive performance and demonstrated variability across different cohorts. The assembling pre- and post-radiomics model demonstrated stability with AUCs hovering around 0.6, yet exhibited poor predictive performance. Integration of all three parameters—clinical, pre-radiomics, and post-radiomics—into a unified model yielded the highest and most stable AUC values for survival prediction across all three cohorts: 0.66 (95% CI: 0.536–0.779) in the training cohort, 0.717 (95% CI: 0.536–0.883) in the testing cohort, and 0.827 (95% CI: 0.684–0.948) in the validation cohort. The improvement, ranging from 0.05 to 0.06 compared to the best AUC values achieved by previous models, signified an enhancement in predictive performance. Specifically, there was an increase of 0.045 in comparison to the AUC of clinical data in the training set, 0.05 compared to the AUC of post-radiomics data in the testing set, and 0.06 compared to the AUC of pre-radiomics data in the validation set. Statistical analyses conducted on these models revealed significant improvements with the assembly of clinical, pre-, and post-radiomics data compared to the other models across all cohorts. In the training cohort, it demonstrated superiority over the post-treatment radiomics model (p = 0.034). In the testing cohort, it outperformed the clinical model (p = 0.0005) and the pre-radiomics model (p = 0.044). In the validation cohort, it surpassed the clinical model (p = 1.13e-05), the post-radiomics model (p = 0.002), and the combined pre- and post-radiomics model (p = 0.007). The incorporation of AUPRC offered additional insights, particularly in scenarios with imbalanced datasets or when the emphasis was on positive class prediction (Fig. S5, Appendix). Additionally, precision, recall, F1 score, and accuracy metrics were included to ensure a comprehensive assessment of model performance (Fig. S6, Appendix). It showed that the clinical model exhibited robust performance across all metrics, while the pre-radiomics, post-radiomics, and its assembled models demonstrated subpar performance. Notably, the assembling clinical, pre-, and post-radiomics model achieved similar performance to the clinical model, demonstrating high precision, recall, F1 score, and accuracy, with a higher AUPRC value. This suggests an improved precision-recall trade-off in predicting positive cases.

Fig. 3.

ROC curves were plotted for four models: the clinical model, pre-radiomics model, post-radiomics model, assembling pre- and post-radiomics model, and assembling clinical, pre-, and post-radiomics model in a training cohort, b testing cohort, and c validation cohort. Pairwise comparisons of the area under the ROC curves (d) were conducted, specifically focusing on the assembled clinical, pre-, and post-radiomics model against the other models across different cohorts. All analyses were based on predictions of 3-year progression-free survival (PFS)

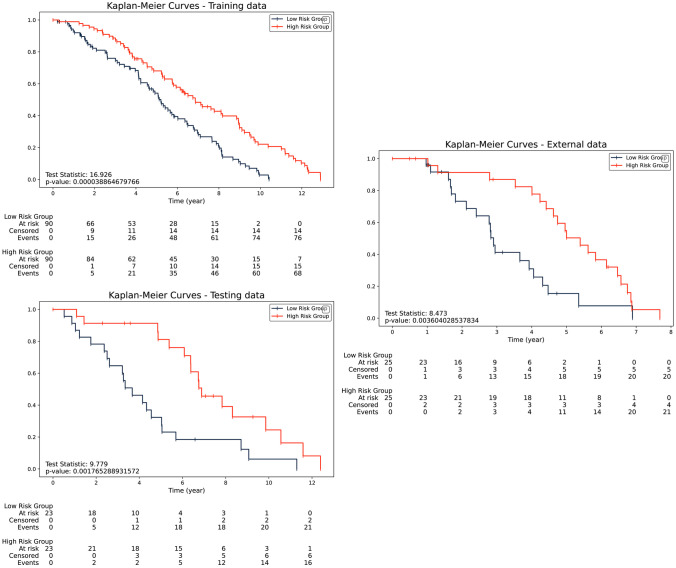

The Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the different investigated cohorts were depicted in Fig. 4, based on the best-performing model, which integrated clinical, pre-, and post-radiomics. The median score of risk score was computed and utilized to classify patients into high- and low-risk groups. According to the log-rank test, there was a discernible disparity (p-value < 0.05) in survival time among NPC patients classified into high- and low-risk groups, thereby distinguishing them from one another. The striking differentiation underscores both the predictive power and potential clinical utility of the integrated model in prognosticating NPC patient outcomes, particularly with high test statistics indicating a strong and significant association between risk groups and survival outcomes, thus reinforcing the reliability and validity of the analysis.

Fig. 4.

The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of risk levels was computed from clinical, pre-, and post-treatment MRI risk scores in a training cohort, b testing cohort, and c validation cohort, with respect to 3-year progression-free survival (PFS)

An Individualized Clinical-Radiomics Monogram

We provided a nomogram integrating the well-established model with survival-relevant clinical predictors, furnishing clinicians with quantitative tools to predict initialized NPC patient survival following treatment (Fig. 5a). The findings demonstrated that the computed risk score performed superior to all traditional clinical prediction indicators, offering the ideal guideline for gauging the long-term prognosis of patients following treatment. Calibration curves were provided to compare the consistency between survival time and the predicted progress (Fig. 5b), which demonstrated the consistency between predicted survival outcomes and actual patient survival times. Therefore, the predictive model, represented by the nomogram, proved effective in estimating the long-term prognosis of patients following treatment when integrating clinical, pre-, and post-radiomics data.

Fig. 5.

a An established nomogram including clinical and risk factor scores derived from clinical and radiomics predictors for 3-year and 5-year progression-free survival, and b calibration curves to estimate progression-free survival in NPC patients

Discussions

In the present study, we conducted a thorough investigation into the effectiveness of utilizing a combination of clinical data and MRI radiomics, both before and after treatment, for predicting survival outcomes in patients across various stages and types of NPCs. Our findings underscore the potential of combining clinical data with radiomics derived from both pre- and post-treatment MRI scans to enhance the accuracy of 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) predictions in NPC patients.

NPC presents clinicians with multifaceted challenges, primarily due to its tendency for late detection and the heightened risk of second primary cancers. The location of the tumor allows it to progress to an advanced stage before symptoms lead to its discovery, making early detection challenging [34]. Additionally, studies have indicated that patients with NPC have a 24% increased risk of developing second primary cancers, which can significantly impact patient survival [35]. Furthermore, familial predisposition to NPC extends beyond the disease itself, encompassing virally associated cancers of the salivary glands and cervical uteri [36]. Following treatment for NPC, while advancements in treatment have improved outcomes, patients face various potential outcomes, ranging from complete remission to disease recurrence and progression. Most individuals achieve long-term survival and cure; others may experience disease persistence or relapse, leading to a poorer prognosis [11, 13]. Understanding the factors associated with post-treatment mortality is of paramount importance in guiding clinical decision-making and optimizing patient care. Consequently, the development of prediction models not only enhances clinical decision-making but also empowers patients by providing them with realistic prognostic information to guide their treatment journey.

Numerous studies have focused on predicting the prognosis of NPC patients, aiming to enhance treatment strategies and patient outcomes. Clinical predictors typically encompass cancer stage and the type of NPCs, commonly employed to delineate the extent of cancer throughout the body [28, 37]. In addition, it has been demonstrated in several prior studies, both in experimental and statistical scenarios, that certain blood constituents, which are detectable through routine clinical blood tests, may be able to anticipate both the disease status and prognosis in NPC [20–23]. In our study, we rigorously examined the clinical data of patients before and after treatment, meticulously analyzing demographics and clinical-pathologic features. Through this comprehensive statistical investigation, we identified several crucial clinical predictors of survival in NPC patients. These predictors encompassed key clinical variables such as the pathology code for cancer categorization, clinical N cancer stage, GPT levels, HCT levels, and post-treatment WBC levels (WBC_post). In alignment with previous research findings regarding the association of clinicopathological data with NPC prognosis [16, 17, 38] and changes in GPT levels and HCT levels with NPC progression [28, 39], our study further emphasizes the significance of evaluating lymph node topography before treatment and specifically highlights post-treatment inflammation as being linked to white blood cell counts [40].

Recent advancements in imaging techniques have shown that MRI-radiomics can serve as a preferred tool for imaging in NPC patients due to its enhanced resolution of soft tissue as the nasopharynx [41]. Through intricate topography evaluation, clinicians can discern subtle tissue characteristics and patterns, thereby gaining deeper insights into tumor behavior, treatment response, and patient outcomes. In parallel, the integration of MRI data with AI models holds significant promise for enhancing prognostic capabilities in NPC [42]. By leveraging AI algorithms trained on MRI-radiomics features, these models can extract complex patterns and relationships from imaging data that may not be readily apparent to human observers [43, 44]. Consequently, we meticulously analyzed radiomics features extracted from pre- and post-treatment MRI scans of 276 NPC patients. From a vast array of extracted features, we utilized the Pearson correlation and LASSO regression for feature selection, ensuring that only the most relevant and non-redundant features were retained, thus minimizing the risk of overfitting [45]. Through this rigorous process, we identified the most pertinent features from both pre- and post-treatment MRI scans that contribute to prognostic insights in NPC. It is intriguing that highly associated features were identified from both the tumor and lymph nodes before treatment, while only information from the delineated tumor after treatment proved significant. Residual tumors and/or lymph nodes in NPC patients within 2 months after treatment are well-known as the “phantom tumor” phenomenon, contributing to the patient’s response to treatment [29, 46–48]. Given the intrinsic complexity associated with delineating ROIs on post-treatment MRIs, arising from the intratumor heterogeneity induced by variations in tissue tolerance and survival subsequent to irradiation, [30–32], our manual segmentation process remained effective in delineating tumors and lymph nodes, with acceptable variation observed between different clinicians [49, 50]. Upon screening, it was suggested that tissues appearing at the site of the tumor around 2 months after treatment can contain valuable information that can significantly contribute to the prognosis.

In prior research endeavors, radiomics data has frequently been extracted from CT or MRI scans, often alongside clinical information, and subsequently incorporated into a variety of machine learning or deep learning algorithms (e.g., logistic regression [13]; random forest [14]; Nomogram [41, 42], and convolutional neural network [51–53]). Notably, the focus in these studies has primarily been on pre-treatment images, thus potentially overlooking the valuable prognostic insights offered by post-treatment changes [24, 26, 54]. Indeed, some recent studies on NPC have recognized and demonstrated the importance of integrating post-treatment radiomics in survival prediction models. These models have shown higher accuracy compared to those based solely on pre-treatment radiomics [18, 55, 56]. One cannot, nevertheless, argue that clinical data is redundant, as its combination with radiomics information can yield a prediction model significantly more precise than one generated using only radiomics data [57, 58].

As a multi-center study, our investigation encompassed diverse models aimed at optimizing prognosis in NPC, including those relying solely on clinical data, pre-treatment radiomics, post-treatment radiomics, the radiological integration of pre- and post-treatment data, and an integrated approach combining both clinical and radiomics data from pre- and post-treatment stages. The AUC analyses unveiled that models relying solely on clinical data or pre- and post-radiomics predictors demonstrated limited predictive capacity with single radiomics predictors exhibiting more extensive and consistent predictive performance than clinical. Integrating pre- and post-radiomics data bolstered the model’s performance. Moreover, the inclusion of clinical predictors not only enhanced predictive capabilities, yielding AUCs ranging from 0.66 to 0.827, the highest across the cohorts, but also optimized the delicate balance between precision and recall, thereby improving prognostic accuracy for NPC patient survival. Consequently, through the amalgamation of all available data sources, the model can effectively identify patients at high risk of adverse outcomes while minimizing false positives and false negatives. Relative to comparable studies [14–18], our model has evinced noteworthy efficacy in forecasting the survival of NPC patients subsequent to treatment, showcasing elevated accuracy and reliability in prognostic assessments. Specifically, Bao et al. demonstrated the combined radiomics and clinical features yielded an AUC of 0.78 for predicting 3-year disease progression-free survival (PFS) in 199 patients [17]. Jiang et al. showed that the pre-treatment radiomic model outperformed the clinical model, with a performance range of 0.781 to 0.848, in 218 nonmetastatic NPC patients [15]. Additionally, in a cohort of 206 patients, Li et al. illustrated that their ensemble model, integrating pre- and post-treatment images, surpassed individual models and traditional TNM staging, achieving a performance range of 0.83 to 0.842 [14]. Sun et al. developed a clinical-and-radiomics nomogram integrating pre-treatment and post-treatment radiomics signatures yielded an AUC of 0.871 for predicting 2-year PFS in 120 NPC patients [18]. Xi et al. integrated clinical and pre-treatment radiomics features to predict 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) in 313 NPC patients, achieving high predictive performance with AUC values of 0.84 in the training set and 0.81 in the test set [16]. While these studies collectively underscore the significance of integrating multiple predictors for enhancing NPC survival prognosis, further research on diverse patient cohorts and prediction tools is essential to refine the true predictive capability, especially in low-incidence contexts of NPC with limited resources for external validation and advanced model application. Our study’s strength lies in its comprehensive approach, integrating both clinicopathologic and hematological data with MRI features obtained from both pre- and post-treatment stages, offering a more holistic and accurate predictive tool for NPC patient prognosis in various patient cohorts. These results are particularly notable given the challenges associated with NPC prognosis, including its heterogeneous nature and frequent recurrences despite initial treatment success. The integration of post-treatment MRI and clinical data appears to be a key factor in the enhanced performance of our model, suggesting that changes in tumor characteristics following treatment provide valuable prognostic information.

The Kaplan–Meier curves have shown the assembling model’s effectiveness, contributing to the reliable stratification of NPC patients. In consideration of the phantom tumor phenomenon, classifying patients into two risk groups will allow clinicians to tailor their treatment plans as well as carefully monitor cases where residual tumors/nodes may need histological confirmation [59]. Moreover, the use of nomograms in oncology has been widespread due to their capacity to offer individualized risk assessments using multiple variables [60]. Sun et al. constructed a nomogram using data from stage II NPC patients to predict 5-year and 10-year overall survival and to estimate the benefit of concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Similarly, Li et al. developed a nomogram based on serum biomarkers and clinical characteristics for non-metastatic NPC patients, which facilitated more precise prognostic predictions [61]. Faccioli et al. highlighted the importance of assessing cell proliferative activity to predict the clinical course for high-risk NPC patients, emphasizing the need for improved therapeutic strategies [62]. These studies underscore the significance of utilizing diverse tools and methodologies to enhance prognostic predictions for NPC patients. In our study, the nomogram derived from the optimal model, integrating both clinical and radiomics data obtained before and after therapy, could be utilized for predicting patient survival. The calibration curves further validate the accuracy of our nomogram, showing good agreement between predicted and observed survival probabilities. This offers a practical tool for clinicians to predict individualized survival outcomes for NPC patients ensuring that interventions and treatments are precisely targeted, thereby enhancing patient outcomes and enabling the implementation of more personalized healthcare strategies in NPC management.

While the study presents a comprehensive approach to predicting NPC survival by integrating pre- and post-treatment clinical data with MRI radiomics, several limitations exist. First, the data was collected from three independent hospitals in Taiwan, which might not be representative of NPC patients from other regions or ethnicities. The study is retrospective in nature, which may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of the findings. Indeed, the significant differences observed in the TMN stage, N category, GOT, and follow-up time among the different cohorts could disproportionately affect the model’s predictive accuracy. The observed higher discrepancy in model performance of the test and validation cohorts compared to the training cohort underscores the presence of selective bias in the enrolled data. Despite rigorous preprocessing and validation, inherent limitations in real-world data collection persist. Additionally, while HRs offer valuable insights into the relationship between variables and outcomes, it is crucial to recognize the potential for bias inherent in their estimation process [63]. Future endeavors should prioritize larger, balanced datasets to improve predictive model reliability and explore prospective designs to mitigate selection bias and enhance HR estimate robustness. The study also relied on manual segmentation of MRI scans, despite undergoing a rigorous delineation process by experienced individuals, which may still introduce variability and potential inaccuracies in extracting radiomics features. The radiomics profiles were not built and evaluated on multiple MRI planes to identify the most valuable radiomics features but were built only on postcontrast T1 images. Lastly, the current study did not compare the performance of the proposed model with other existing prediction models for NPC survival within the dataset, which makes it challenging to determine its relative superiority or novelty. Nevertheless, the promising results from this study on NPC survival prediction still pave the way for several future research avenues. There exists a clear potential to refine and expand the model by incorporating advanced imaging modalities and data from various MRI planes, exploring alternative machine learning algorithms, or integrating genomic and proteomic data for a more comprehensive prediction approach. Given that the study was primarily conducted in Taiwan, it would be beneficial to validate and adapt the model across diverse geographical regions and ethnic populations to ensure its generalizability and applicability beyond the specific population studied. Additionally, real-time application of the model in clinical settings, followed by a feedback loop for continuous improvement, can further enhance its predictive accuracy and clinical relevance.

Conclusion

We constructed pre- and post-treatment profiles encompassing a comprehensive array of clinical and radiomics predictors, contributing to the development of a robust survival predictive model. Clinicians are encouraged to utilize these novel predictors and incorporate the proposed model, which integrates clinical data with MRI radiomics in both pre- and post-treatment phases, to effectively stratify NPC patients into high- and low-risk groups. Moreover, the potential utility of this model extends to the creation of nomograms for use in clinical settings, providing clinicians with valuable tools for facilitating tailored treatment strategies and improving patient outcomes. Further prospective studies and validations conducted across diverse populations are essential to solidify the clinical utility of our proposed model.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

The study is supported by TMU—Wan Fang Research grant no. 111TMU-WFH-13.

Data Availability

All data in this study can be obtained by contacting the corresponding authors upon reasonable request

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Luong Huu Dang and Shih-Han Hung contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.X. Zhou, W. Zhao, Y. Chen, and Z. Zhang, “Chapter Six - Patient-derived tumor models for human nasopharyngeal carcinoma,” in Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane Model and Precision Cancer Therapy, vol. 46, F. B. T.-T. E. Tamanoi, Ed., Academic Press, 2019, pp. 81–96. 10.1016/bs.enz.2019.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.L.-X. Peng and C.-N. Qian, “Chapter 17 - Nasopharyngeal Cancer,” S. G. B. T.-E. C. T. Gray, Ed., Boston: Academic Press, 2015, pp. 373–389. 10.1016/B978-0-12-800206-3.00017-3.

- 3.P. J. Slootweg and A. K. El-Naggar, “World Health Organization 4th edition of head and neck tumor classification: insight into the consequential modifications.” Virchows Archiv: an international journal of pathology, vol. 472, no. 3. Germany, pp. 311–313, Mar. 2018. 10.1007/s00428-018-2320-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Y. Wang, Y. Zhang, and S. Ma, “Racial differences in nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the United States.,” Cancer Epidemiol, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 793–802, Dec. 2013. 10.1016/j.canep.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.H. Peng et al., “Prognostic value of deep learning PET/CT-based radiomics: Potential role for future individual induction chemotherapy in advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma,” Clinical Cancer Research, vol. 25, no. 14, pp. 4271–4279, 2019. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.J. Yi et al., “Nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated by radical radiotherapy alone: Ten-year experience of a single institution.,” Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 161–168, May 2006. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.M. Kang et al., “Validation of the 8th edition of the UICC/AJCC staging system for nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy.,” Oncotarget, vol. 8, no. 41, pp. 70586–70594, Sep. 2017. 10.18632/oncotarget.19829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.S. Li, Y. Deng, Z. Zhu, H. Hua, and Z. Tao, A Comprehensive Review on Radiomics and Deep Learning for Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Imaging. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.P. Bossi et al., “Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up,” Annals of Oncology, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 452–465, 2021. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Y.-P. Chen, A. T. C. Chan, Q.-T. Le, P. Blanchard, Y. Sun, and J. Ma, “Nasopharyngeal carcinoma,” The Lancet, vol. 394, no. 10192, pp. 64–80, Jul. 2019. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30956-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.S. Wang, S. Chen, Q. Zhong, and Y. Liu, “Immunotherapy for the treatment of advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a promising new era,” J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2022. 10.1007/s00432-022-04214-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.V. Kaartemo and A. Helkkula, “A Systematic Review of Artificial Intelligence and Robots in Value Co-creation: Current Status and Future Research Avenues,” Journal of Creating Value, vol. 4, Oct. 2018. 10.1177/2394964318805625.

- 13.W. M. Yu and S. S. M. Hussain, “Incidence of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Chinese immigrants, compared with Chinese in China and South East Asia: review.,” J Laryngol Otol, vol. 123, no. 10, pp. 1067–1074, Oct. 2009. 10.1017/S0022215109005623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.S. Li et al., “Deep learning for locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma prognostication based on pre- and post-treatment MRI,” Comput Methods Programs Biomed, vol. 219, p. 106785, 2022. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2022.106785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.S. Jiang, L. Han, L. Liang, and L. Long, “Development and validation of an MRI-based radiomic model for predicting overall survival in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients with local residual tumors after intensity-modulated radiotherapy,” BMC Med Imaging, vol. 22, no. 1, Dec. 2022. 10.1186/s12880-022-00902-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Y. Xi et al., “Early prediction of long-term survival of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma by multi-parameter MRI radiomics,” Eur J Radiol Open, vol. 12, Jun. 2024. 10.1016/j.ejro.2023.100543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.D. Bao et al., “Prognostic and predictive value of radiomics features at MRI in nasopharyngeal carcinoma,” Discover Oncology, vol. 12, no. 1, Dec. 2021. 10.1007/s12672-021-00460-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.M. X. Sun, M. J. Zhao, L. H. Zhao, H. R. Jiang, Y. X. Duan, and G. Li, “A nomogram model based on pre-treatment and post-treatment MR imaging radiomics signatures: application to predict progression-free survival for nasopharyngeal carcinoma,” Radiation Oncology, vol. 18, no. 1, Dec. 2023. 10.1186/s13014-023-02257-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.X. Yang, J. Wu, and X. Chen, “Application of Artificial Intelligence to the Diagnosis and Therapy of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma,” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 12, no. 9. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), May 01, 2023. 10.3390/jcm12093077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Z. Lin, X. Zhang, Y. Luo, Y. Chen, and Y. Yuan, “The value of hemoglobin-to-red blood cell distribution width ratio (Hb/RDW), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) for the diagnosis of nasopharyngeal cancer,” Medicine (United States), vol. 100, no. 28, p. E26537, Jul. 2021. 10.1097/MD.0000000000026537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.E. Kifle, M. Hussein, J. Alemu, and W. Tigeneh, “Prevalence of Anemia and Associated Factors among Newly Diagnosed Patients with Solid Malignancy at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Radiotherapy Center, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia,” Adv Hematol, vol. 2019, p. 8279789, 2019. 10.1155/2019/8279789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.J. Zhu, R. Fang, Z. Pan, and X. Qian, “Circulating lymphocyte subsets are prognostic factors in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma,” BMC Cancer, vol. 22, no. 1, Dec. 2022. 10.1186/s12885-022-09438-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Y. Dai et al., “The effect of hispidulin, a flavonoid from salvia plebeia, on human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cne-2z cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and apoptosis,” Molecules, vol. 26, no. 6, Mar. 2021. 10.3390/molecules26061604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.M. Zhang, S. Wei, L. Su, W. Lv, and J. Hong, “Prognostic significance of pretreated serum lactate dehydrogenase level in nasopharyngeal carcinoma among Chinese population: A meta-analysis.,” Medicine, vol. 95, no. 35, p. e4494, Aug. 2016. 10.1097/MD.0000000000004494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.L. Huang et al., “Lactate dehydrogenase kinetics predict chemotherapy response in recurrent metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma.,” Ther Adv Med Oncol, vol. 12, p. 1758835920970050, 2020. 10.1177/1758835920970050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.J. Li et al., “Prognostic nomogram for patients with Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma incorporating hematological biomarkers and clinical characteristics.,” Int J Biol Sci, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 549–556, 2018. 10.7150/ijbs.24374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.N. Lee et al., “Intensity-modulated radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Radiation therapy oncology group phase II trial 0225,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 27, no. 22, pp. 3684–3690, Aug. 2009. 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.M. B. Amin et al., “ The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population‐based to a more ‘personalized’ approach to cancer staging ,” CA Cancer J Clin, vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 93–99, Mar. 2017. 10.3322/caac.21388. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.C. C. Lee, J. C. Lee, W. Y. Huang, C. J. Juan, Y. M. Jen, and L. F. Lin, “Image-based diagnosis of residual or recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma may be a phantom tumor phenomenon,” Medicine (United States), vol. 100, no. 8, p. E24555, Feb. 2021. 10.1097/MD.0000000000024555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.A. A. K. Abdel Razek and A. King, “MRI and CT of nasopharyngeal carcinoma,” American Journal of Roentgenology, vol. 198, no. 1. pp. 11–18, Jan. 2012. 10.2214/AJR.11.6954. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.M. W. van den Brekel et al., “Cervical lymph node metastasis: assessment of radiologic criteria.,” Radiology, vol. 177, no. 2, pp. 379–384, Nov. 1990. 10.1148/radiology.177.2.2217772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.T. Liu et al., “Radiomic signatures reveal multiscale intratumor heterogeneity associated with tissue tolerance and survival in re-irradiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a multicenter study,” BMC Med, vol. 21, no. 1, Dec. 2023. 10.1186/s12916-023-03164-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.S. F. Su et al., “Treatment outcomes for different subgroups of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy,” Chin J Cancer, vol. 30, no. 8, pp. 565–573, 2011. 10.5732/cjc.010.10547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D. P. Shedd, C. F. von Essen, and H. Eisenberg, “Cancer of the nasopharynx in connecticut. 1935 through 1959,” Cancer, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 508–511, Jan. 1967. 10.1002/1097-0142(1967)20:4<508::AID-CNCR2820200407>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.M.-C. Chen et al., “The incidence and risk of second primary cancers in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a population-based study in Taiwan over a 25-year period (1979–2003),” Annals of Oncology, vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 1180–1186, Jun. 2008. 10.1093/annonc/mdn003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.J. Friborg, J. Wohlfahrt, A. Koch, H. Storm, O. R. Olsen, and M. Melbye, “Cancer Susceptibility in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Families—A Population-Based Cohort Study,” Cancer Res, vol. 65, no. 18, pp. 8567–8572, Sep. 2005. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.T. S. De Silva, D. MacDonald, G. Paterson, K. C. Sikdar, and B. Cochrane, “Systematized nomenclature of medicine clinical terms (SNOMED CT) to represent computed tomography procedures,” Comput Methods Programs Biomed, vol. 101, no. 3, pp. 324–329, 2011. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.S. Miao et al., “Development and validation of a risk prediction model for overall survival in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a prospective cohort study in China,” Cancer Cell Int, vol. 22, no. 1, Dec. 2022. 10.1186/s12935-022-02776-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.B. Zhang, T. Zhang, L. Jin, Y. Zhang, and Q. Wei, “Treatment Strategy of Metastatic Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma With Bone Marrow Involvement—A Case Report,” Front Oncol, vol. 12, Jun. 2022. 10.3389/fonc.2022.877451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.J. Liu, C. Wei, H. Tang, Y. Liu, W. Liu, and C. Lin, “The prognostic value of the ratio of neutrophils to lymphocytes before and after intensity modulated radiotherapy for patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma,” Medicine (United States), vol. 99, no. 2, Jan. 2020. 10.1097/MD.0000000000018545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.X. Zhong et al., “Cervical spine osteoradionecrosis or bone metastasis after radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma? The MRI-based radiomics for characterization,” BMC Med Imaging, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 104, 2020. 10.1186/s12880-020-00502-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.M. Bologna et al., “Baseline mri-radiomics can predict overall survival in non-endemic ebv-related nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 1–20, Oct. 2020. 10.3390/cancers12102958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.H. Shen et al., “Predicting Progression-Free Survival Using MRI-Based Radiomics for Patients With Nonmetastatic Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma,” Front Oncol, vol. 10, no. May, pp. 1–7, 2020. 10.3389/fonc.2020.00618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.S. D. McGarry et al., “Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Based Radiomic Profiles Predict Patient Prognosis in Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma Before Therapy.,” Tomography, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 223–228, Sep. 2016. 10.18383/j.tom.2016.00250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.R. Tibshirani, “Regression Shrinkage and Selection Via the Lasso,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 267–288, Jan. 1996. 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1996.tb02080.x. [Google Scholar]

- 46.J. Weng et al., “Clinical outcomes of residual or recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with endoscopic nasopharyngectomy plus chemoradiotherapy or with chemoradiotherapy alone: A retrospective study,” PeerJ, vol. 2017, no. 10, 2017. 10.7717/peerj.3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.H. L. Hua et al., “Deep learning for the prediction of residual tumor after radiotherapy and treatment decision-making in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma based on magnetic resonance imaging,” Quant Imaging Med Surg, vol. 13, no. 6, Jun. 2023. 10.21037/qims-22-1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.J. L. Mi, M. Xu, C. Liu, and R. S. Wang, “Prognostic nomogram to predict the distant metastasis after intensity-modulated radiation therapy for patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma,” Medicine (United States), vol. 100, no. 47, Nov. 2021. 10.1097/MD.0000000000027947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.L. Zhang et al., “Development and validation of a magnetic resonance imaging-based model for the prediction of distant metastasis before initial treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A retrospective cohort study,” EBioMedicine, vol. 40, pp. 327–335, Feb. 2019. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.X. Zhang et al., “The effects of volume of interest delineation on MRI-based radiomics analysis: evaluation with two disease groups,” Cancer Imaging, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 89, 2019. 10.1186/s40644-019-0276-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.J. Huang, R. He, J. Chen, S. Li, Y. Deng, and X. Wu, “Boosting Advanced Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Stage Prediction Using a Two-Stage Classification Framework Based on Deep Learning,” International Journal of Computational Intelligence Systems, vol. 14, no. 1, 2021. 10.1007/s44196-021-00026-9.

- 52.S. Intarak et al., “Tumor Prognostic Prediction of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Using CT-Based Radiomics in Non-Chinese Patients,” Front Oncol, vol. 12, no. January, pp. 1–9, 2022. 10.3389/fonc.2022.775248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.M. Qiang et al., “A Prognostic Predictive System Based on Deep Learning for Locoregionally Advanced Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma,” JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 113, no. 5, pp. 606–615, May 2021. 10.1093/jnci/djaa149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.R.-X. Cen and Y.-G. Li, “Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as a potential prognostic factor in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A meta-analysis.,” Medicine, vol. 98, no. 38, p. e17176, Sep. 2019. 10.1097/MD.0000000000017176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.S. J. Kim, J. Y. Choi, Y. C. Ahn, M. J. Ahn, and S. H. Moon, “The prognostic value of radiomic features from pre- and post-treatment 18F-FDG PET imaging in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma,” Sci Rep, vol. 13, no. 1, Dec. 2023. 10.1038/s41598-023-35582-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Y. Xi et al., “Prediction of Response to Induction Chemotherapy Plus Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy for Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Based on MRI Radiomics and Delta Radiomics: A Two-Center Retrospective Study,” Front Oncol, vol. 12, Apr. 2022. 10.3389/fonc.2022.824509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.X. Bin et al., “Nomogram Based on Clinical and Radiomics Data for Predicting Radiation-induced Temporal Lobe Injury in Patients with Non-metastatic Stage T4 Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma,” Clin Oncol, vol. 34, no. 12, pp. e482–e492, Dec. 2022. 10.1016/j.clon.2022.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.P. Bos et al., “Improved outcome prediction of oropharyngeal cancer by combining clinical and MRI features in machine learning models,” Eur J Radiol, vol. 139, no. March, p. 109701, 2021. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2021.109701. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Y.-Y. Huang, X. Cao, Z.-C. Cai, J.-Y. Zhou, X. Guo, and X. Lv, “Short-term efficacy and long-term survival of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients with radiographically visible residual disease following observation or additional intervention: A real-world study in China,” Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 1881–1892, Dec. 2022. 10.1002/lio2.980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.V. P. Balachandran, M. Gonen, J. J. Smith, and R. P. DeMatteo, “Nomograms in oncology: more than meets the eye,” Lancet Oncol, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. e173–e180, Apr. 2015. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71116-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Q.-J. Li et al., “A Nomogram Based on Serum Biomarkers and Clinical Characteristics to Predict Survival in Patients With Non-Metastatic Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma,” Front Oncol, vol. 10, 2020, [Online]. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2020.594363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.S. Faccioli, O. Cavicchi, U. Caliceti, A. R. Ceroni, and P. Chieco, “Cell proliferation as an independent predictor of survival for patients with advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma.,” Mod Pathol, vol. 10 9, pp. 884–94, 1997, [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:24871135 [PubMed]

- 63.M. A. Hernán, “The hazards of hazard ratios,” Epidemiology, vol. 21, no. 1. pp. 13–15, Jan. 2010. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c1ea43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data in this study can be obtained by contacting the corresponding authors upon reasonable request