Abstract

This study aims to investigate the maximum achievable dose reduction for applying a new deep learning-based reconstruction algorithm, namely the artificial intelligence iterative reconstruction (AIIR), in computed tomography (CT) for hepatic lesion detection. A total of 40 patients with 98 clinically confirmed hepatic lesions were retrospectively included. The mean volume CT dose index was 13.66 ± 1.73 mGy in routine-dose portal venous CT examinations, where the images were originally obtained with hybrid iterative reconstruction (HIR). Low-dose simulations were performed in projection domain for 40%-, 20%-, and 10%-dose levels, followed by reconstruction using both HIR and AIIR. Two radiologists were asked to detect hepatic lesion on each set of low-dose image in separate sessions. Qualitative metrics including lesion conspicuity, diagnostic confidence, and overall image quality were evaluated using a 5-point scale. The contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) for lesion was also calculated for quantitative assessment. The lesion CNR on AIIR at reduced doses were significantly higher than that on routine-dose HIR (all p < 0.05). Lower qualitative image quality was observed as the radiation dose reduced, while there were no significant differences between 40%-dose AIIR and routine-dose HIR images. The lesion detection rate was 100%, 98% (96/98), and 73.5% (72/98) on 40%-, 20%-, and 10%-dose AIIR, respectively, whereas it was 98% (96/98), 73.5% (72/98), and 40% (39/98) on the corresponding low-dose HIR, respectively. AIIR outperformed HIR in simulated low-dose CT examinations of the liver. The use of AIIR allows up to 60% dose reduction for lesion detection while maintaining comparable image quality to routine-dose HIR.

Keywords: Computed tomography, Hepatic lesion, Dose reduction, Artificial intelligence iterative reconstruction

Introduction

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) is one primary modality that has been widely used for the diagnosis of hepatic lesions. Detecting hepatic lesions with CT images depends on not only lesion characteristics, such as lesion size and contrast, but also the applied radiation dose [1–3]. That is, detection of small low-contrast lesions is a challenging task because of the similar attenuation between lesions and the surroundings. Low-dose CT acquisitions may present additional difficulties owing to a substantial increase in image noise and artifacts. With recent advantages in artificial intelligence, various deep learning-based reconstruction (DLR) algorithms based on deep neural network models have been proposed to improve image quality in low-dose settings [4]. Several studies on the use of these algorithms have reported that low-dose hepatic CT reconstructed with DLR might yield diagnostic image quality and lesion detectability comparable to that of standard-of-care images [5–8]. However, these results were limited by the fact that only one low-dose level was investigated, while the maximum possible dose reduction of DLR on hepatic CT is yet to be determined.

An ideal way of this investigation is to compare the low-dose images against that of the routine scan, which means rescans must be placed on each patient multiple times [9–11]. Even with patients’ consent, the extra radiation dose delivered by the rescan remains questionable from the ethical perspective. Phantoms mimicking the patient anatomy could help as a surrogate [12, 13], but their relevance in detailed settings of specific clinical applications is often insufficient. In this regard, low-dose CT simulation, which was generally used in developing CT image reconstruction algorithms, offers the advantage of allowing head-to-head comparisons between low-dose and routine-dose images, while involving neither rescanning nor additional radiation dose. With the simulation technique, many studies have enabled to investigate low-dose diagnostic performance in various clinical scenarios, e.g., detection of cerebral perfusion impairment [14], vertebral fracture [15], and suspected appendicitis [16].

Therefore, our study aimed to explore the maximum achievable dose reduction for applying a new DLR, namely the artificial intelligence iterative reconstruction (AIIR, United Imaging Healthcare, Shanghai, China), regarding the image quality and hepatic lesion detection by the use of low-dose simulation. To this end, datasets with three simulated low-dose levels (40%, 20%, and 10%) were generated from the original data (100%-dose). Subsequently, low-dose images were reconstructed with the AIIR and compared to routine-dose images reconstructed with the routinely available hybrid iterative reconstruction (HIR, United Imaging Healthcare, Shanghai, China).

Materials and Methods

The study protocol was approved by the medical research ethical committee of our institutional review board, where the need for written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of data analysis.

Study Population

We reviewed all cases between January and May 2022 to identify patients who underwent routine contrast-enhanced abdominal CT examinations with the same scanner for clinical indications. All adult patients diagnosed with focal hepatic lesions were considered for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were (a) lack of raw data, which is needed for AIIR in the course of reconstruction, and (b) the presence of severe motion/metal artifacts on the image. Among the 54 patients identified from the reviewing period, 10 patients were removed where the raw data for AIIR reconstruction was not properly saved. Another 4 patients were excluded from this study due to poor image quality. Finally, a total of 40 patients were included in this study. Based on previously reported data [17, 18] and our power analysis, a sample size of 40 would provide a statistical power of at least 80%. Patient demographics and clinical information were recorded from electronic medical records. Figure 1 illustrates the study design.

Fig. 1.

The flowchart of the study design

CT Scan Acquisition

All patients underwent helical contrast-enhanced CT on a 320-detector row CT scanner (uCT 960 + , United Imaging Healthcare, Shanghai, China). The scanning was performed with the following parameters: a fixed tube voltage of 120 kVp and auto-mAs technique for dose modulation; 0.5 s gantry rotation time; 80 mm collimation, and 0.9937 pitch. Iodinated contrast medium (Iomeprol 400 mgI/mL, Bracco Diagnostics) was administered using a weight-dependent volume of 1.3 mL/kg at an injection rate of 2.5–3.0 mL/s, followed by a 30 mL saline chase. The scanning began with 5, 25–30 and 60–70 s delay for the hepatic arterial, portal venous, and equilibrium phases, respectively, after a threshold of 210 HU on the descending aorta was achieved.

Low-Dose CT Simulation and Image Reconstruction

CT raw data acquired at the portal venous phase were used for low-dose simulation and analysis in the present study. Low-dose projections were simulated from the original projection data via the approach proposed by Zabić et al. [19], which followed the Poisson statistics for X-ray photons, accounted for the covariance between the original and the lowered signal, included a realistic non-Gaussian component for detector noise, and was found to be sufficiently accurate for highly attenuated regions as well as extremely low-dose scenarios. Specifically, simulations were made at 40%-, 20%-, and 10%-dose levels, corresponding to 60%, 80%, and 90% dose reduction, respectively.

Simulated low-dose CT were reconstructed with both HIR and AIIR, where the reconstruction parameters were set exactly the same as taken for the original routine-dose data. All reconstructions were 2 mm in slice thickness and 2 mm in slice interval, as commonly used for routine examinations. The AIIR is a vendor-specific algorithm that integrates both deep learning denoising network and model-based iterative reconstruction into the reconstruction workflow, showing great potential in thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic applications [20–22]. During the iterative loop, a deep learning-based model is utilized in the noise regularization term to achieve noise reduction while maintaining the natural image appearance. The AIIR was trained by taking noise-contaminated sinogram and image data as input, and producing noise-free images as output. To improve the generalizability of the AIIR, various datasets, including different kVp, mAs, contrast enhancements, and body parts, were used for the training.

Image Analysis

A total of 280 image datasets (40 patients × 7 reconstructions) were transferred to a clinical post-processing workstation (uWS-CT R004, United Imaging Healthcare, Shanghai, China) for image analysis.

Reference Standard and Lesion Detection

The reference standard was established by making use of every piece of information available in routine clinical setting, including multiphasic CT, liver MRI, PET/CT, biopsy, and surgery. All focal hepatic lesions, defined as any non-calcified, focal, or solid organ abnormality with increased or decreased relative density, were identified and marked on the original 100%-dose HIR images. It was worth mentioning that, as required by the standard diagnostic workflow, the diagnosis on the original images was first conducted by one radiologist and then reviewed by another radiologist (usually more senior). The size, type, and number of lesions present on the marked images were recorded and were accounted for in all subsequent image analysis.

Two board-certified abdominal radiologists (with 7 and 9 years of experience in CT diagnosis) were asked to independently read the low-dose images and perform hepatic lesion detection. They were blinded both to the patient demographics and the reconstruction methods. Each reader evaluated 10%-, 20%-, and 40%-dose images in three separate sessions, with an interval period of 3 weeks to reduce recall bias. For each session, images were presented in random order and in a setting where readers were permitted to scroll, zoom, and adjust the display window/level, emulating the clinical environment. After each reading session was completed, consensus was reached through negotiation between readers as discrepancy for lesion detection occurred, which was consistent to the diagnostic workflow in our institution.

Qualitative Analysis

In process of the detective reading, the two aforementioned readers were also asked to independently score the images for each patient, regarding lesion conspicuity, diagnostic confidence, and overall image quality using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = poor, 2 = low, 3 = acceptable, 4 = good, and 5 = excellent. The conspicuity of lesions was assessed based on the differentiation of lesion relative to the background tissue. Diagnostic confidence was rated on both the detectability of lesions and the difficulty for performing diagnosis. The overall image quality was assessed for the entire image, including the regions of hepatic veins, tissues beyond liver, and the factors such as noise appearance and artifacts. Since it is rather common to have multiple lesions present on the same image, making it unrealistic to expect the observer to focus on a single lesion and objectively rate it at one time, such that all qualitative analyses were performed on per-patient level. Finally, the qualitative image quality for routine-dose HIR was evaluated in the same manner.

Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative measurements were conducted using the regions of interest (ROIs) delineated by an experienced radiologist (with 11 years of experience in CT diagnosis) on the routine-dose HIR. The ROIs were then copied-pasted to the low-dose image sets, to ensure consistency on ROI placement throughout the datasets. For attenuation measurements, multiple circular ROIs with the largest possible size were placed in the homogeneous part of the lesions, liver parenchyma, main portal vein, and paraspinal musculature. The image noise was defined as the standard deviation (SD) of the attenuation in the ROI. Care was taken to avoid confounding structures, such as calcification plaques, vessel edges, and artifacts, in each ROI. For all reconstructions, attenuation (in HU) and SD in each ROI were recorded. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was determined by dividing the mean attenuation by SD. The contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) for liver and for portal vein relative to muscle was calculated as , while the CNR for lesion relative to liver was calculated as , where HUliver, HUvein, HUmuscle, and HUlesion are the mean attenuation of liver, portal vein, paraspinal musculature, and lesion, respectively. SDmuscle and SDliver are the mean image noise of paraspinal musculature and liver, respectively.

Subgroup Analysis

To further explore confounding factors associated with lesion detection, a subgroup analysis was performed. The impact of body mass index (BMI), radiation dose, reconstruction algorithm, lesion type, size, SNR, and CNR on lesion detection was tested by using univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed on SPSS version 20.0. The normality of quantitative data was examined by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. For comparison of the quantitative and qualitative image quality across the reconstructions and the radiation doses, either the paired t-test or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used, if appropriate. The chi-square test was used to test the difference of categorical data. Inter-observer agreement for qualitative evaluation was tested by weighted kappa analysis, where 0–0.20 as slight, 0.21–0.40 as fair, 0.41–0.60 as moderate, 0.61–0.80 as substantial, and 0.81–1 as perfect agreement. A p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistically significant.

Results

Patient and Lesion Characteristics

The final cohort consisted of 40 patients (15 females, 25 males), with a mean age of 57.3 ± 13.5 years (range, 29–83), a mean height of 167.5 ± 7.4 cm (range, 153–180), and a mean BMI of 22.4 ± 2.7 (range, 17.3–28.7). The mean CTDIvol, DLP, and effective dose for the portal venous phase were 13.66 ± 1.73 mGy, 737.32 ± 183.11 mGy × cm, and 11.13 ± 2.77 mSv, respectively.

According to the reference standard, a total of 98 focal hepatic lesions were found among the included patients: 37 hepatic cysts, 8 hepatocellular carcinomas, 21 hepatic metastases, 24 hepatic hemangiomas, 3 focal hepatic steatoses, 4 benign hypo-attenuating hepatic lesions, and one hepatic adenoma. Of these lesions, 43 (mean size, 5.8 ± 1.9 mm; range, 3.1–9.8 mm) were ≤ 10 mm, while 55 (mean size, 21.1 ± 10.1 mm; range, 10.3–52.3 mm) were > 10 mm, with a mean size in diameter of 14.4 ± 10.8 mm (range, 3.1–52.3 mm).

Lesion Detection

Representative cases are shown in Figs. 2 and 3. On HIR images, the lesion detection rate was 98% (96/98), 73.5% (72/98), and 40% (39/98) at 40%-, 20%-, and 10%-dose levels, respectively. Two hepatic cysts were missed on 40%-dose HIR. The 26 lesions missed on 20%-dose HIR included hepatic cysts (n = 9), hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 1), hepatic metastases (n = 6), hepatic hemangiomas (n = 9), and benign hypo-attenuating hepatic lesion (n = 1). More than half of lesions (59/98) were missed at 10%-dose level, with only 39 lesions detected (11 hepatic cysts, 4 hepatocellular carcinomas, 12 hepatic metastases, 6 hepatic hemangiomas, 3 focal hepatic steatoses, and 3 benign hypo-attenuating hepatic lesions). On the contrary, all lesions were correctly detected on 40%-dose AIIR images for both readers. With AIIR reconstruction, the lesion detection rate was improved to 98% (96/98) and 73.5% (72/98) on 20%- and 10%-dose levels, respectively. Only 2 hepatic cysts were missed on 20%-dose AIIR, and 26 lesions, including 11 hepatic cysts, 1 hepatocellular carcinoma, 5 hepatic metastases, 7 hepatic hemangiomas, and 2 benign hypo-attenuating hepatic lesions, were missed on 10%-dose AIIR. No false-positive lesions were detected during the review.

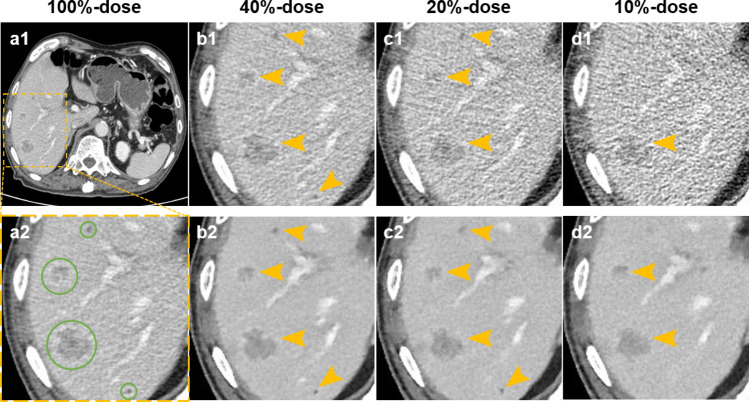

Fig. 2.

Comparison of hepatic CT images at 4 dose levels in an 83-year-old male with hepatic cysts and metastases. (a1–d1 and a2) images reconstructed with HIR. (b2–d2) images reconstructed with AIIR. Green circles indicate reference lesions, and yellow arrows indicate hepatic lesions detected by readers. All lesions can be detected on 40%-dose and 20%-dose AIIR, with the lesion conspicuity being scored as 5 and 4, respectively. However, a tiny hepatic cyst (3.4 mm) was missed on 20%-dose HIR, where the lesion conspicuity was scored as 2. On 10%-dose HIR and AIIR, 3 and 2 out of 4 lesions were failed to detect by readers, respectively

Fig. 3.

Comparison of hepatic CT images at 4 dose levels in a 64-year-old male with an 8.1 mm hepatic hemangioma (green circle). (a1–d1 and a2) images reconstructed with HIR. (b2–d2) images reconstructed with AIIR. The hemangioma was detected on both AIIR and HIR at 40%- and 20%-dose level (yellow arrows), while it appears more conspicuous with AIIR than with HIR. Two readers failed to detect the hemangioma on both 10%-dose HIR and AIIR, where the lesion CNR were 0.22 and 0.51, respectively. The lesion conspicuity was scored as 1 for two images, due to the blurring of lesion boundary and loss of imaging detail

Image Quality Analysis

The results of quantitative measurements are shown in Table 1. Compared to HIR, AIIR significantly improved the SNR and CNR for liver, main portal vein, and lesion at the same dose level (all p < 0.001). As the radiation dose reduced, quantitative image quality showed a tendency to decrease for both reconstructions. Nevertheless, the SNR and CNR for 10%-dose AIIR were superior to those for routine-dose HIR (all p < 0.001), yielding approximately two-fold improvements for all anatomic structures.

Table 1.

Quantitative image quality analysis

| SNR | CNR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Main portal vein | Lesion | Liver | Main portal vein | Lesion | |

| 100% dose | ||||||

| HIR | 6.71 ± 1.62 | 8.05 ± 2.36 | 3.28 ± 2.57 | 3.09 ± 1.44 | 6.96 ± 2.34 | 3.57 ± 2.52 |

| 40% dose | ||||||

| HIR | 4.66 ± 1.04#* | 5.72 ± 1.45#* | 2.57 ± 1.96#* | 2.16 ± 0.98#* | 4.81 ± 1.64#* | 2.44 ± 1.69#* |

| AIIR | 12.57 ± 2.52* | 15.09 ± 4.84* | 6.69 ± 4.07* | 5.25 ± 2.4* | 11.68 ± 3.64* | 6.55 ± 4.45* |

| 20% dose | ||||||

| HIR | 3.51 ± 0.84#* | 4.49 ± 1.09#* | 2.07 ± 1.55#* | 1.58 ± 0.74#* | 3.6 ± 1.19#* | 1.86 ± 1.36#* |

| AIIR | 11.66 ± 2.84* | 14.14 ± 3.94* | 4.85 ± 3.54* | 5.21 ± 2.36* | 11.53 ± 3.85* | 6.1 ± 4.31* |

| 10% dose | ||||||

| HIR | 2.47 ± 0.67#* | 3.16 ± 0.75#* | 1.65 ± 1.09#* | 1.17 ± 0.55#* | 2.68 ± 0.93#* | 1.21 ± 0.86#* |

| AIIR | 11.17 ± 2* | 13.32 ± 3.55* | 5.37 ± 3.84* | 4.91 ± 2.22* | 10.74 ± 3.62* | 5.12 ± 3.76* |

#p ≤ 0.001 between HIR and AIIR at the same dose level

*p ≤ 0.05 between low-dose images and 100%-dose HIR

For qualitative analysis of both readers (Table 2), a similar trend of degraded image quality was observed with reduced radiation dose for HIR and AIIR reconstructions. Compared to HIR, AIIR images provided higher lesion conspicuity, improved diagnostic confidence, and superior overall image quality at the same dose level (all p < 0.001). There were no significant differences between 40%-dose AIIR and routine-dose HIR for all qualitative image quality metrics. Furthermore, based on the qualitative scores rated by reader 1, the proportions of scores ≥ 4 regarding lesion conspicuity, diagnostic confidence, and overall image quality were 95%, 89%, and 100% in routine-dose HIR, and 82%, 79%, and 100% in 20%-dose AIIR, respectively, without statistical differences (all p > 0.05). The image quality inter-observer agreement was fair for routine-dose HIR images (κ, 0.23), fair to substantial for low-dose HIR (κ, 0.33–0.65), and substantial to perfect for low-dose AIIR (κ, 0.57–0.89).

Table 2.

Qualitative image quality scores

| Reader 1 | Reader 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion conspicuity | Diagnostic confidence | Overall image quality | Lesion conspicuity | Diagnostic confidence | Overall image quality | |

| 100% dose | ||||||

| HIR | 4.63 ± 0.59 | 4.53 ± 0.69 | 4.84 ± 0.37 | 4.82 ± 0.39 | 4.79 ± 0.41 | 4.74 ± 0.52 |

| 40% dose | ||||||

| HIR | 3.74 ± 0.79#* | 3.76 ± 0.79#* | 3.39 ± 0.68#* | 3.68 ± 0.66#* | 3.79 ± 0.7#* | 3.52 ± 0.69#* |

| AIIR | 4.82 ± 0.39 | 4.76 ± 0.43 | 4.92 ± 0.27 | 4.79 ± 0.41 | 4.82 ± 0.39 | 4.66 ± 0.53 |

| 20% dose | ||||||

| HIR | 2.42 ± 0.76#* | 2.53 ± 0.83#* | 2.79 ± 0.62#* | 2.53 ± 0.89#* | 2.63 ± 0.91#* | 2.63 ± 0.63#* |

| AIIR | 3.89 ± 0.51* | 3.87 ± 0.53* | 4.45 ± 0.5* | 4 ± 0.62* | 3.87 ± 0.41* | 4.42 ± 0.5* |

| 10% dose | ||||||

| HIR | 1.45 ± 0.6#* | 1.5 ± 0.65#* | 1.97 ± 0.54#* | 1.42 ± 0.6#* | 1.45 ± 0.6#* | 2.11 ± 0.69#* |

| AIIR | 2.32 ± 0.77* | 2.55 ± 0.6* | 3.11 ± 0.39* | 2.42 ± 0.72* | 2.61 ± 0.59* | 3.08 ± 0.36* |

#p ≤ 0.001 between HIR and AIIR at the same dose level

*p ≤ 0.05 between low-dose images and 100%-dose HIR

Factors of Lesion Detection

Univariate analysis found that radiation dose, reconstruction algorithm, lesion size, and CNR were the factors with significant influence on lesion detection, except for BMI, lesion type, and SNR. According to multivariate analysis, radiation dose, reconstruction algorithm, lesion size, and CNR remained significant factors of lesion detection (Table 3).

Table 3.

Linear regression analysis to identify factors associated with lesion detection

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | p value | Coefficient (95% CI) | p value | |

| BMI | − 0.059 (− 0.020, 0.002) | 0.122 | − 0.035 (− 0.014, 0.004) | 0.279 |

| Radiation dose (reference: 100%) | ||||

| 40% | − 0.012 (− 0.090, 0.070) | 0.803 | − 0.108 (− 0.170, − 0.009) | 0.029 |

| 20% | − 0.173 (− 0.223, − 0.063) | < 0.001 | − 0.255 (− 0.293, − 0.129) | < 0.001 |

| 10% | − 0.524 (− 0.223, − 0.063) | < 0.001 | − 0.582 (− 0.566, − 0.397) | < 0.001 |

| Reconstruction algorithm (reference: HIR) | ||||

| AIIR | 0.168 (0.071, 0.183) | < 0.001 | 0.157 (0.040, 0.197) | 0.003 |

| Lesion type (reference: hepatic adenoma) | ||||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.026 (− 0.258, 0.329) | 0.811 | 0.025 (− 0.207, 0.275) | 0.781 |

| Metastases | 0.007 (− 0.276, 0.290) | 0.962 | 0.031 (− 0.205, 0.261) | 0.815 |

| Hemangiomas | − 0.069 (− 0.342, 0.223) | 0.679 | 0.017 (− 0.218, 0.249) | 0.898 |

| Steatoses | 0.066 (− 0.177, 0.462) | 0.380 | 0.034 (− 0.190, 0.335) | 0.587 |

| Benign hypo-attenuating | 0 (− 0.309, 0.309) | > 0.999 | 0.025 (− 0.213, 0.308) | 0.719 |

| Cysts | − 0.065 (− 0.331, 0.230) | 0.725 | − 0.068 (− 0.298, 0.192) | 0.673 |

| Lesion size | 0.172 (0.003, 0.009) | < 0.001 | 0.193 (0.004, 0.010) | < 0.001 |

| Lesion SNR | 0.056 (− 0.002, 0.015) | 0.142 | − 0.047 (− 0.016, 0.005) | 0.291 |

| Lesion CNR | 0.254 (0.019, 0.034) | < 0.001 | 0.232 (0.013, 0.035) | < 0.001 |

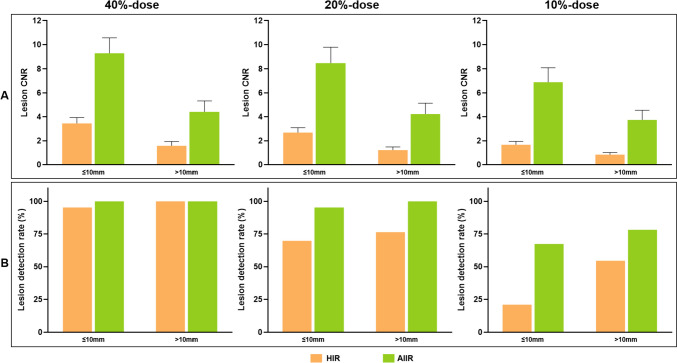

The detection rates for lesions with sizes of ≤ 10 mm and > 10 mm were 95.3% (41/43) and 100% (45/45) at 40%-dose level, 69.8% (30/43) and 76.4% (42/55) at 20%-dose level, and 20.9% (9/43) and 54.5% (30/55) at 10%-dose level, respectively, on HIR. Lesions that were detected had notably higher CNR than those that were not detected (2.07 ± 1.53 vs. 1.28 ± 0.98, p < 0.001), regardless of lesion size. As the radiation dose reduced, the trend for decreased CNR was more pronounced on lesions ≤ 10 mm than those > 10 mm (Fig. 4A). Reduced detection rate was observed with a lower radiation dose, smaller lesion size, and worse lesion CNR (Table 3; Fig. 4B). With the use of AIIR, the mean CNR for lesions were significantly improved, especially for those lesions that were failed to detect on HIR images (AIIR vs. HIR: 4.88 ± 3.88 vs. 1.28 ± 0.98, p < 0.001). Among 87 lesions missed on HIR, 61 (70%) lesions with a mean CNR of 5.46 ± 4.11 were correctly detected on AIIR images, while the remaining lesions with a relatively lower CNR of 3.53 ± 2.9 were still failed to detect. Consequently, the detection rates for lesions with sizes of ≤ 10 mm and > 10 mm were improved to 100% (43/43) and 100% (55/55) at 40%-dose level, 95.3% (41/43) and 100% (55/55) at 20%-dose level, and 67.4% (29/43) and 78.2% (43/55) at 10%-dose level, respectively, by AIIR.

Fig. 4.

Bar graphs show lesion CNR and detection rate in relation to radiation dose, reconstruction algorithm, and lesion size

Discussion

Low-dose hepatic CT imaging with the maximum achievable dose reduction is not only in keeping with but also necessary to exercising the “As low as reasonably achievable (ALARA)” principle. However, the boundaries for dose reduction on hepatic CT by DLR are still to be determined. Our results demonstrated that AIIR performed better than HIR at reduced doses. AIIR showed the benefit of detecting low-contrast hepatic lesions, particularly for those with smaller sizes (≤ 10 mm). The use of AIIR allows for significant dose reduction as much as up to 60% for lesion detection while maintaining the image quality, compared to routine-dose HIR.

Low-contrast detection tasks are mainly affected by image contrast differences. This study revealed that the mean CNR of lesions was significantly improved using AIIR. This was not surprising because of the robust denoising provided by AIIR that increased the contrast between the target lesion and background tissue. The deep learning-based model utilized in AIIR was trained with high-quality CT images that contain various clinical scenarios. Thus, AIIR adds better performance for noise reduction than HIR. As supported by lesion detection analysis, lesions with higher CNR can be more easily detected by readers. Our results were analogous to those of Park et al. [8], who concluded that DLR in their study provides better conspicuity of hepatic lesions by improving lesion CNR. Another related study by Lyu et al. [23] also reported that DLR improves image quality and hepatic metastases CNR, allowing for lesion detection with increased diagnostic confidence at reduced dose. Considering these results, the present findings further confirm the benefits of such DLR algorithms on low-contrast lesion detection.

However, in this study, there was a discrepancy between CNR and lesion conspicuity. Although CNR on low-dose AIIR was significantly higher than that on routine-dose HIR, lower lesion conspicuity was observed as the radiation dose reduced. This may be explained from two perspectives. First, AIIR was trained to achieve lower image noise; therefore, better quantitative image quality, including noise, SNR, and CNR, can be obtained by AIIR. Second, CNR is a simple metric related with image noise, which may not be sufficient for assessing the contour of lesion boundaries. During reviewing cases, readers reported that some lesions decreased in size with blurred edges on 10%-dose AIIR, which degraded the lesion conspicuity. The current results showed that AIIR may induce the loss of imaging detail at ultralow-dose due to the similar behavior with other noise reduction methods [24, 25], suggesting dose reduction must be balanced against an acceptable level of lesion detection and evaluation.

The degree to which DLR can decrease radiation exposure varies upon factors such as the baseline and specific clinical tasks intended. A phantom analysis by Greffier et al. [13], where dose levels up to a CTDIvol of 15 mGy, indicated a potential dose reduction of 46–56% for one of the DLRs relative to HIR. Several clinical studies also reported that a 49–67% dose reduction to the mean CTDIvol of 4.42–12.2 mGy is possible by DLRs on hepatic CT [6–8, 23]. In this study, we analyzed the performance of AIIR on lesion detection, as well as the correlations between the AIIR and HIR, across a range of dose levels. The present study adds to these findings by demonstrating that low-dose hepatic CT using DLR with a 60% dose reduction (mean CTDIvol, 5.46 mGy) yielded non-inferior image quality and lesion detection, as compared with routine-dose CT using HIR. Furthermore, the use of AIIR may allow for a significant dose reduction of 80% while preserving lesion detection rate for lesion > 10 mm. Although 20%-dose AIIR revealed inferior qualitative results than routine-dose HIR, the mean scores for all metrics were higher than 3, which is acceptable for diagnosis.

Apart from reducing tube current and utilizing advanced CT image reconstructions, lowering tube voltage is another method for the reduction of radiation dose. The application of low-kilovolt protocols has already been reported to effectively reduce both radiation dose and contrast medium dosage [26–28], which could be of clinical importance for patients who underwent multiple contrast-enhanced CT examinations. However, the decrease of tube voltage usually induces increased image noise and susceptibility to beam hardening artifacts, resulting in the degradation of image quality. A prospective study recently confirmed the feasibility of AIIR used in our study on aortic CT angiography with a 70-kVp protocol [20]. The AIIR can help reduce image noise as well as metal artifacts caused by implanted material, even in patients with a large BMI. Accordingly, it is conceivable that the AIIR would be valuable for low-kilovolt hepatic CT imaging with potential implications of patient care.

This study had several limitations. First, the investigative strategy adopted in this study, which was simulation, naturally carries a question regarding the discrepancy between real and simulated data. Although the simulation technique has been well validated and every care was taken in the test to follow the diagnostic practice in clinical setting, it is still of interest to verify the findings in complete clinical scenarios, hopefully taking advantage of the hints as provided in this study. Second, only three radiation dose levels were simulated for study analysis, which may potentially introduce bias to the conclusions. Third, the current results are vendor-specific and are directly applicable only to the liver. Nevertheless, the demonstrated investigative strategy for determining the maximum achievable dose reduction can be translated to other body parts and clinical scenarios. Finally, we did not compare the performance between different DLR algorithms. Therefore, further comparison studies with a larger population would be of interest.

Conclusion

AIIR outperformed HIR in simulated low-dose CT examinations of the liver. The use of AIIR allows up to 60% dose reduction for lesion detection while maintaining comparable image quality to routine-dose HIR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Zhenlin Li and Guozhi Zhang; data collection: Yongchun You, Yuting Wen, Dian Guo and Wanjiang Li; statistical analysis and data interpretation: Yongchun You, Sihua Zhong, Wanjiang Li; manuscript preparation: Yongchun You, Sihua Zhong and Guozhi Zhang; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFF0501504); and West China Hospital “1·3·5” Discipline of Excellence Project (ZYGD18019).

Data Availability

All the data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

Institutional review board approval was obtained.

Consent to Participate

Written informed consent was waived.

Consent for Publication

The authors affirm that consent to publish has been received from all human research participants.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wanjiang Li and Zhenlin Li contributed equally as co-corresponding authors to this work.

Contributor Information

Wanjiang Li, Email: 452766554@qq.com.

Zhenlin Li, Email: HX_lizhenlin@126.com.

References

- 1.Volders D, Bols A, Haspeslagh M, Coenegrachts K. Model-based iterative reconstruction and adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction techniques in abdominal CT: comparison of image quality in the detection of colorectal liver metastases. Radiology. 2013;269(2):469–474. 10.1148/radiol.13130002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon J, Marin D, Roy Choudhury K, Patel B, Samei E. Effect of Radiation Dose Reduction and Reconstruction Algorithm on Image Noise, Contrast, Resolution, and Detectability of Subtle Hypoattenuating Liver Lesions at Multidetector CT: Filtered Back Projection versus a Commercial Model-based Iterative Reconstruction Algorithm. Radiology. 2017;284(3):777–787. 10.1148/radiol.2017161736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pooler BD, Lubner MG, Kim DH, et al. Prospective Evaluation of Reduced Dose Computed Tomography for the Detection of Low-Contrast Liver Lesions: Direct Comparison with Concurrent Standard Dose Imaging. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(5):2055–2066. 10.1007/s00330-016-4571-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koetzier LR, Mastrodicasa D, Szczykutowicz TP, et al. Deep Learning Image Reconstruction for CT: Technical Principles and Clinical Prospects. Radiology. 2023;306(3):e221257. 10.1148/radiol.221257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh R, Digumarthy SR, Muse VV, et al. Image Quality and Lesion Detection on Deep Learning Reconstruction and Iterative Reconstruction of Submillisievert Chest and Abdominal CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;214(3):566–573. 10.2214/AJR.19.21809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeng L, Xu X, Zeng W, et al. Deep learning trained algorithm maintains the quality of half-dose contrast-enhanced liver computed tomography images: Comparison with hybrid iterative reconstruction: Study for the application of deep learning noise reduction technology in low dose. Eur J Radiol. 2021;135:109487. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.109487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen CT, Gupta S, Saleh MM, et al. Reduced-Dose Deep Learning Reconstruction for Abdominal CT of Liver Metastases. Radiology. 2022;303(1):90–98. 10.1148/radiol.211838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park S, Yoon JH, Joo I, et al. Image quality in liver CT: low-dose deep learning vs standard-dose model-based iterative reconstructions. Eur Radiol. 2022;32(5):2865–2874. 10.1007/s00330-021-08380-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vardhanabhuti V, Loader RJ, Mitchell GR, Riordan RD, Roobottom CA. Image quality assessment of standard- and low-dose chest CT using filtered back projection, adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction, and novel model-based iterative reconstruction algorithms. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200(3):545–552. 10.2214/AJR.12.9424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang B, Li N, Shi X, et al. Deep Learning Reconstruction Shows Better Lung Nodule Detection for Ultra-Low-Dose Chest CT. Radiology. 2022;303(1):202–212. 10.1148/radiol.210551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang G, Zhang X, Xu L, et al. Value of deep learning reconstruction at ultra-low-dose CT for evaluation of urolithiasis. Eur Radiol. 2022;32(9):5954–5963. 10.1007/s00330-022-08739-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higaki T, Nakamura Y, Zhou J, et al. Deep Learning Reconstruction at CT: Phantom Study of the Image Characteristics. Acad Radiol. 2020;27(1):82–87. 10.1016/j.acra.2019.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greffier J, Hamard A, Pereira F, et al. Image quality and dose reduction opportunity of deep learning image reconstruction algorithm for CT: a phantom study. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(7):3951–3959. 10.1007/s00330-020-06724-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afat S, Brockmann C, Nikoubashman O, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Simulated Low-Dose Perfusion CT to Detect Cerebral Perfusion Impairment after Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Retrospective Analysis. Radiology. 2018;287(2):643–650. 10.1148/radiol.2017162707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sollmann N, Mei K, Hedderich DM, et al. Multi-detector CT imaging: impact of virtual tube current reduction and sparse sampling on detection of vertebral fractures. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(7):3606–3616. 10.1007/s00330-019-06090-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolb M, Storz C, Kim JH, et al. Effect of a novel denoising technique on image quality and diagnostic accuracy in low-dose CT in patients with suspected appendicitis. Eur J Radiol. 2019;116:198–204. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen CT, Liu X, Tamm EP, et al. Image Quality Assessment of Abdominal CT by Use of New Deep Learning Image Reconstruction: Initial Experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;215(1):50–57. 10.2214/AJR.19.22332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao L, Liu X, Li J, et al. A study of using a deep learning image reconstruction to improve the image quality of extremely low-dose contrast-enhanced abdominal CT for patients with hepatic lesions. Br J Radiol. 2021;94(1118):20201086. 10.1259/bjr.20201086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zabić S, Wang Q, Morton T, Brown KM. A low dose simulation tool for CT systems with energy integrating detectors. Med Phys. 2013;40(3):031102. 10.1118/1.4789628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li W, You Y, Zhong S, et al. Image quality assessment of artificial intelligence iterative reconstruction for low dose aortic CTA: A feasibility study of 70 kVp and reduced contrast medium volume. Eur J Radiol. 2022;149:110221. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2022.110221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang L, Liu H, Han J, et al. Ultra-low-dose CT lung screening with artificial intelligence iterative reconstruction: evaluation via automatic nodule-detection software. Clin Radiol. 2023;S0009-9260(23)00031-4. 10.1016/j.crad.2023.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu Y, Zheng Z, Yu H, Wang J, Yang X, Shi H. Ultra-low-dose CT reconstructed with the artificial intelligence iterative reconstruction algorithm (AIIR) in 18F-FDG total-body PET/CT examination: a preliminary study. EJNMMI Phys. 2023;10(1):1. 10.1186/s40658-022-00521-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyu P, Liu N, Harrawood B, et al. Is it possible to use low-dose deep learning reconstruction for the detection of liver metastases on CT routinely?. Eur Radiol. 2023;33(3):1629–1640. 10.1007/s00330-022-09206-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deák Z, Grimm JM, Treitl M, et al. Filtered back projection, adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction, and a model-based iterative reconstruction in abdominal CT: an experimental clinical study. Radiology. 2013;266(1):197–206. 10.1148/radiol.12112707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen CT, Telesmanich ME, Wagner-Bartak NA, et al. Evaluation of Abdominal Computed Tomography Image Quality Using a New Version of Vendor-Specific Model-Based Iterative Reconstruction. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2017;41(1):67–74. 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagayama Y, Nakaura T, Oda S, et al. Value of 100 kVp scan with sinogram-affirmed iterative reconstruction algorithm on a single-source CT system during whole-body CT for radiation and contrast medium dose reduction: an intra-individual feasibility study. Clin Radiol. 2018;73(2):217.e7–217.e16. 10.1016/j.crad.2017.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hou P, Feng X, Liu J, et al. Low Tube Voltage and Iterative Model Reconstruction in Follow-up CT Angiography After Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair: Ultra-low Radiation Exposure and Contrast Medium Dose. Acad Radiol. 2018;25(4):494–501. 10.1016/j.acra.2017.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Y, Liu Z, Li M, et al. Reducing both radiation and contrast doses in coronary CT angiography in lean patients on a 16-cm wide-detector CT using 70 kVp and ASiR-V algorithm, in comparison with the conventional 100-kVp protocol. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(6):3036–3043. 10.1007/s00330-018-5837-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.