Abstract

Brain tumors are a threat to life for every other human being, be it adults or children. Gliomas are one of the deadliest brain tumors with an extremely difficult diagnosis. The reason is their complex and heterogenous structure which gives rise to subjective as well as objective errors. Their manual segmentation is a laborious task due to their complex structure and irregular appearance. To cater to all these issues, a lot of research has been done and is going on to develop AI-based solutions that can help doctors and radiologists in the effective diagnosis of gliomas with the least subjective and objective errors, but an end-to-end system is still missing. An all-in-one framework has been proposed in this research. The developed end-to-end multi-task learning (MTL) architecture with a feature attention module can classify, segment, and predict the overall survival of gliomas by leveraging task relationships between similar tasks. Uncertainty estimation has also been incorporated into the framework to enhance the confidence level of healthcare practitioners. Extensive experimentation was performed by using combinations of MRI sequences. Brain tumor segmentation (BraTS) challenge datasets of 2019 and 2020 were used for experimental purposes. Results of the best model with four sequences show 95.1% accuracy for classification, 86.3% dice score for segmentation, and a mean absolute error (MAE) of 456.59 for survival prediction on the test data. It is evident from the results that deep learning–based MTL models have the potential to automate the whole brain tumor analysis process and give efficient results with least inference time without human intervention. Uncertainty quantification confirms the idea that more data can improve the generalization ability and in turn can produce more accurate results with less uncertainty. The proposed model has the potential to be utilized in a clinical setup for the initial screening of glioma patients.

Keywords: Brain tumors, Artificial intelligence, MTL, Gliomas, Uncertainty estimation

Introduction

Artificial intelligence has taken its place in every field and now can be seen everywhere, i.e., robotics, environmental engineering, educational institutes to financial predictions for banks and industries [1, 2]. We can predict the future outcome and hence can manage our present in a more efficient way using AI. That is the true wonder of artificial intelligence. Similarly, the wonders of AI cannot be overlooked in medical disease diagnosis [1, 2]. For a decade or so, AI is turning waves in the medical field. One cannot see any disease left behind that has not been diagnosed and tested using AI [2].

Brain tumors are considered very harmful due to their difficult diagnosis [1]. More than 120 types of tumors have evolved [1–3], and they are spreading quickly in children, too [1, 4]. Brain tumors can be benign or malignant. Benign tumors have a regular shape and get detected easily while malignant tumors have an irregular shape and difficult diagnosis [1]. Brain tumors can be classified as either primary or secondary. Primary brain tumors start growing inside the brain and spread there while secondary brain tumors start growing anywhere inside the body and then travel towards the brain [1]. Gliomas are one of the most dangerous types of brain tumors that arise in the glial cells of the brain and come under the category of primary malignant brain tumors [1, 5, 6]. Gliomas can be a high grade (HGG) or low grade (LGG) depending upon their appearance and chemical composition [4, 7]. High-grade gliomas are considered a malignant category of tumors due to their aggressive nature, high mortality rate, and their low chance of survival whereas low-grade gliomas are slow growing with a high chance of survival [8].

Currently, all types of brain tumors are diagnosed with the help of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology, which is considered the best due to its non-invasive nature and contrast enhancement features [6]. Although varying types of MRI sequences are there, frequently used MRI sequences are T1, T2, T1CE (T1 contrast-enhanced), and Flair (fluid attenuation recovery). Conventionally, manual segmentation of tumors is used all over the world, which is time-consuming and is also prone to subjective as well as objective errors [5, 6, 9]. The difficulty in diagnosis arises due to the complex appearance inherited by the tumorous cells. The chemical composition of the tumor makes it appear quite like non-tumorous tissue, which creates difficulty in detection and prognosis. The delay in detection causes many deaths. The biopsy is considered the gold standard which requires high-cost facilities along with trained manpower and is also a painful procedure [6].

For the last decade or so, researchers have been using AI and deep learning for the early diagnosis and detection of brain tumors using MRI images and remained quite successful [6, 9]. A lot of promising algorithms have surfaced and have proven to be very useful in one way or the other [2, 10], but nothing exists so far that can be easily installed in a clinical setup and can be used commercially as a viable product. The availability of large amounts of data is also a limitation.

Considering the ongoing issues in existing computer-aided tools and to assist doctors efficiently, a very lightweight multi-task learning (MTL) architecture with multi-scale feature attention is proposed in this paper that can perform three tasks simultaneously, i.e., classify the tumor as either HGG/LGG, segments the lesion area, and predict the overall survival of patients in days simultaneously with no human intervention. The architecture also finds uncertainty in its predictions and shows the pixels with the least confidence in the form of images. The contributions can be highlighted as follows:

The novel MTL model gives predictions for three tasks simultaneously, i.e., classification as HGG/LGG, multi-class segmentation, and estimated survival in days.

The proposed MTL solution is a very efficient lightweight model that uses the least resources in terms of computation, memory, and inference time.

Uncertainty estimations account for the confidence level of the proposed architecture.

The proposed solution has the capability to be utilized in clinical routine for initial screening of gliomas.

Figure 1 shows a summarized overview of each section of the paper. The paper is organized as follows: the “Introduction” section covers the topic introduction and application of AI in this domain, the “Related Work” section covers the related literature and the progress made so far in the field, the “Proposed Methodology” section explains in detail the proposed methodology/architecture, the “Results” and “Discussion” sections project the results achieved using different configurations and modalities along with detailed discussion, the “Comparison with Other Studies” and “Complexity Analysis” sections discuss the comparative analysis of the achieved results with relevant recent deep learning techniques along with complexity analysis of the proposed scheme, and finally, the “Conclusion” section concludes the whole research conducted along with highlighting the study’s limitations and future possibilities.

Fig. 1.

Overview of research work

Related Work

An extensive and very thorough review was conducted to understand and get an insight into state-of-the-art research going on in the areas of brain tumor classification, segmentation, and survival prediction [1]. None of the studies presented here handled all three tasks simultaneously, so we reviewed separate papers in each category to cover the advancements going on in each area. We also reviewed studies considering MTL for brain tumor analysis to compel the audience about the need for the proposed solution and for fair comparisons.

Six convolutional neural network (CNN) models for brain tumor classification are built in a study conducted by Kalaiselvi and Padmapriya [11]. The number of layers is the primary differentiator between the six CNN models. Two distinct CNN models use the dropout layer for regularization, with further two models employing stopping criteria and batch normalization in addition to the dropout layer. Two other models are utilized without these layers. The BraTS 2013 dataset is used for training, whereas the World Brain Atlas (WBA) is used for testing. According to the findings, model 4 achieves the greatest results, with a lowered false alarm rate for non-tumor images, while model 6 achieves the best overall accuracy of 96%.

Brain tumor classification is vital for medical prognosis and effective treatment. In this study at [12], a combined feature and image-based classifier (CFIC) is proposed for brain tumor image classification. Multiple deep neural network and deep convolutional neural network architectures are introduced for image classification, including variations like actual image feature–based classifier, segmented image feature–based classifier, and their combinations. The Kaggle Brain Tumor Detection 2020 dataset is used for training and testing. Notably, CFIC outperforms other proposed methods, achieving remarkable results in terms of sensitivity (98.86%), specificity (97.14%), and accuracy (98.97%), respectively, compared to existing classification approaches.

This study at [13] focuses on the classification of brain tumors using 3D MRI images as an alternative of tumor biopsies. A hybrid model termed time distributed-CNN-LSTM (TD-CNN-LSTM) is created for better classification using three BraTS datasets, each of which has four 3D MRI sequences for a single patient. This model treats the MRI sequences from each patient as a single input by fusing a 3D convolutional neural network (CNN), a long short-term memory (LSTM), and a time distributed function. Through ablation investigations on layer design and hyper-parameters, the TD-CNN-LSTM model was further improved. For comparison, a different 3D CNN model is trained for each MRI scan. Performance improvement is ensured through preprocessing. With a remarkable test accuracy of 98.90%, the results show that TD-CNN-LSTM surpasses 3D CNN.

The study at [14] developed and tested a deep learning model for automatic tumor segmentation using conventional MRI data for meningiomas. Two components were included in T1CE segmentation: (i) total lesion volume and (ii) contrast-enhanced tumor volume (union of lesion volume in T1CE and FLAIR, together with solid tumor parts as well as surrounding edema). Data preprocessing included registration, skull stripping, resampling, and normalization. Two separate readers used manual segmentations to design a deep learning model on 70 cases. The system was tested on 56 cases, with automatic and manual segmentations being compared. Deep learning–based automated segmentation provided excellent segmentation accuracy in contrast to manual intrareader variability.

The study at [15] introduces DeepSeg, a novel decoupling framework for automated brain lesion identification and segmentation utilizing only the flair sequence. It is made up of two basic components that work together to encode and decode information. The encoder component uses CNN to extract spatial information. For acquiring a full-resolution probability map, the generated semantic map is sent to the decoder component. The CNN models used in this study were ResNet, DenseNet, and NASNet, which were designed on a modified U-Net architecture. This research has focused on integrating multiple deep learning models into a new DeepSeg framework for automated brain tumor segmentation in flair MRI Images. Results showed that the new framework was able to accurately segment tumors in most images.

In this research at [16], CSU-Net, a novel segmentation network that overcomes the drawbacks of Transformer and CNN topologies, is introduced. Transformers struggle with local information, whereas CNN struggles with long-distance and contextual processing. In the “encoder-decoder” structure adopted by CSU-Net, simultaneous CNN and Transformer-based branches are used in the encoder to extract features, and a dual Swin Transformer decoder block is used in the decoder to upsample the features. Skip connections are used to integrate features with multiple resolutions. On BraTS 2020, CSU-Net gets remarkable Dice score of 89.27% for whole tumor (WT), 88.57% for tumor core (TC), and 81.88% for enhancing tumor (ET), respectively.

For medical diagnosis and prognosis, MRI brain tumor segmentation is essential. Challenges arise from the intricacy of tumor characteristics such as shape and appearance. Although deep neural networks (DNN) have the capacity to segment data accurately, training can be time-consuming because of gradient-related problems. An improved Residual Network (ResNet)-based brain tumor segmentation method is suggested at [17] as a solution to this problem. This method optimizes residual blocks, promotes projection shortcuts, and improves information flow through network layers. With an average dice score of 91%, the enhanced ResNet architecture speeds up learning and reduces computational costs while accelerating segmentation.

For diagnosis, treatment planning, and outcome evaluation, accurate segmentation of gliomas is essential. But manual procedure complicates the timely accurate diagnosis. Although medical imaging technology’s diagnosis has improved, there is optimism for more precise outcomes using deep learning–based segmentation, especially for gliomas. A novel method based on 2D-CNNs with an attention mechanism is suggested at [18] to address the shortcomings of existing approaches. For segmenting multimodal gliomas, the scientists devised a U-Net-based channel attention mechanism and a spatial attention mechanism. While segmenting gliomas more precisely, the attention mechanism can concentrate on task-related properties with less assistance from the computer. This reduces the computational load. The method was evaluated using BraTS-2018 and BraTS-2019 datasets and gives an average dice score of 83%.

In another paper [19], the authors have proposed an efficient encoder-decoder–based multi-task learning (MTL) approach for brain tumor segmentation. The authors have divided the task of segmentation into two parallel architectures performing computations relevant to each task. One architecture generates the mask for enhancing tumor (ET) and tumor core (TC) while the other architecture generates the mask for the whole tumor (WT). The authors have also proposed a hybrid loss function to optimize and account for the losses due to multiple outputs. Extensive experimentations have been performed on BraTS 2019 datasets showing remarkable results.

Another very efficient One-Pass Multi-Task Network (OM-Net) architecture to combat the shortcomings of Model Cascade (MC) is proposed by the authors in [20]. The authors have designed a very well-formulated model with cross-task–guided attention modules for three tasks. The brain tumor segmentation task is divided into three related tasks and integrated into the OM-Net architecture which takes three inputs related to these three tasks and gives three outputs corresponding to three task-specific architectures. One-layer outputs coarse the segmentation of the whole tumor with edema, the second layer outputs fine segmentation without edema, and the last layer outputs the enhancing tumor only. The authors have experimented with the proposed model using BraTS 2015, 2017, and 2018. The proposed scheme proved remarkable with reduced complexity and effective task relationship modeling.

The authors of [21] proposed a multi-task learning model with auxiliary tasks based on the Dilated Multifiber Network (DMF-Net) for the segmentation of small brain tumors. The network has an encoder-decoder–like architecture. The architecture uses two U-Net modules in the first two layers of the encoder-decoder–like U-Net model and used these reconstructed features as an auxiliary task to reinforce the prediction by the base model. The authors utilized two types of losses, segmentation loss and reconstruction loss for better optimization of the proposed architecture. Extensive experimentations were performed on BraTS 2018 dataset and achieved a maximum dice score of 44% better than state-of-the-art models.

In another paper at [22], authors proposed a multi-task learning (MTL) architecture involving fully annotated and weakly annotated images enabling mixed supervision. The idea is to cut down the cost and time factor involved in arranging annotated images. Conventional U-Net architecture was used as a baseline and then was modified by adding a branch for classification also called an auxiliary task. The output of the second to last layer of the U-Net was used as an input to the additional branch for classification. Experiments were performed on the benchmark dataset of BraTS 2018. Results showed an overall dice score ranging from 76 to 81% for the whole tumor which is comparable with state-of-the-art techniques.

In another study at [23], a very novel and optimized deep MTL architecture was demonstrated as a potential candidate for brain tumor segmentation and classification. The architecture was constructed with one shared branch and three separate branches after the bottleneck which corresponds to dedicated tasks. These three tasks include reconstruction, segmentation, and classification. The focus of the authors was on enhancing tumors, so the classifying branch only detects if there is any enhancing tumor or not. The final prediction on the BraTS validation data gives dice scores of 89%, 79%, and 75% for the whole tumor, tumor core, and the enhancing tumor region, respectively.

Another ensemble approach for overall survival prediction of brain tumor patients using multiple views of each modality in MRI scans has been proposed in [24]. The authors have proposed a multi-view single- and multiple-column CNN architecture with a feature ensemble approach. Three multi-view architectures are proposed (one single column and two multiple columns). All three views of a single modality have been utilized and given as 2D input scans to the Mv-CNN model in single- and multiple-column approaches. Single-column models are trained 12 times while multiple-column models are trained 3 and 4 times. Afterwards, extracted features are given as input to 6 different machine-learning models for predicting the OS. Experiments show that SVM gives the best prediction accuracy of OS with the proposed scheme.

The authors in [25] have proposed extensive experimentations with four types of regressor models for improved survival accuracy. The authors first used the conventional 3D U-Net model for brain tumor segmentation. Afterwards, image-based and radiomic-based features were extracted and fed to four regressor models namely, artificial neural network (ANN), linear regressor (LR), gradient boosting regressor (GBR), and random forest regressor (RFR). Results have shown that shape-based features with the gradient boosting regressor are the best combination for survival prediction.

The authors in [26] have introduced a very novel approach of coordinate transformation as a pre-processing step before tumor segmentation and survival prediction. The authors transformed the MRI images from cartesian to spherical for taking the advantage of data augmentation and rich features. Three cascaded DNN models based on variation autoencoders are produced, i.e., Cartesian-v1, Cartesian-v2, and bis Cartesian, which differ in pre-processing technique. Segmentation labels obtained from three models are then combined for more refined segmentation results. Afterwards, three variational autoencoder models are developed for the survival prediction task that extracts the features from the segmentation labels produced in the first stage. The extracted features are then reduced using PCA while a generalized linear model is used as a regressor. Experimental results show 58% overall survival accuracy using the ensemble approach.

In another paper at [27], a simple 2D method for estimating the survival time of patients with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is presented. To semantically partition brain tumor subregions, a 2D residual U-Net is trained. Then, utilizing both raw and segmented MRI volumes along with clinical information, a 2D CNN is trained to forecast survival time in days. With an accuracy of 51.7%, and a mean square error (MSE) of 136,783.42, the experimental results on the Multimodal Brain Tumor Segmentation (BraTS) 2020 validation set using the proposed scheme demonstrate competitive performance. The work illustrates the advantages of deep learning–based feature learning over conventional machine learning approaches.

The study at [28] provides a paradigm for using MRI analysis to forecast the prognosis of individuals with brain tumors. A self-supervised learning technique that focuses on detecting image patches from the same or distinct images to improve the network’s grasp of local and global spatial links is offered to overcome the issue of restricted dataset size. The network learns about these links by identifying both intra- and inter-image differences. In flair MRI brain images, the suggested technique shows a significant association between local spatial relationships and survival class prediction. Evaluation utilizing the BraTS 2020 validation dataset demonstrates this approach’s superiority to alternative approaches by offering an accuracy of 58% and MSE of 97,216.345.

Proposed Methodology

The framework of the proposed solution revolves around the 3D multi-task learning architecture on the U-Net baseline because of its immense popularity [6]. A 2D MTL architecture focusing on segmentation and classification has already been proposed by us [29]. The current work is the 3D extension of our previous work with extended capabilities. The reason for choosing the MTL model is that existing models have a high demand for computational resources and take a large amount of time in processing different tasks separately [1]. MTL can save resources as well as time since it can give results of all associated tasks simultaneously because it learns and optimizes in a parallel fashion by leveraging shared information [30]. Secondly, this model is the best solution for situations where enough data is not available [31]. The literature review also shows that the headache of having multiple models for multiple tasks has also been discouraged by healthcare practitioners. Currently, there is no one end-to-end model that can perform all these three tasks with the least resource utilization and is acceptable for clinical setup [1]. This was the main motivation for proposing the MTL model for brain tumor analysis.

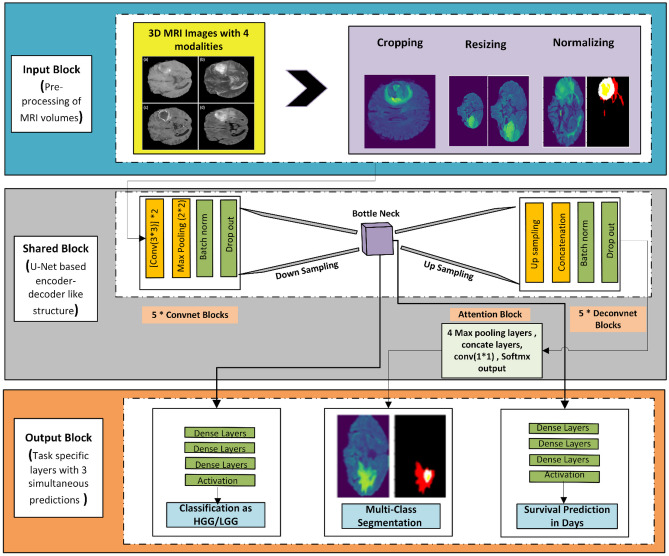

The complete research is carried out according to the sequenced blocks shown in Fig. 2. At first, the data is preprocessed, and then it is fed to the MTL model having three outputs corresponding to three different but interrelated tasks. The model is optimized for maximum accuracy for classification, maximum dice for segmentation, and minimum error for survival prediction. The results are recorded for different models having different MRI modalities. The process is repeated for BraTS 2019 and BraTS 2020 datasets. Uncertainty estimation has also been added to account for the prediction accuracy of the model and to make it more acceptable in the market.

Fig. 2.

General pipeline of 3D MTL methodology

Basic MTL Model

The systematic model of a general MTL architecture is shown in Fig. 3. Multi-task learning architecture has multiple outputs and solves multiple tasks simultaneously [32] by sharing parameters having feature information [33–35] taken from a shared backbone. Learning multiple tasks at the same time also helps in reducing overfitting and regularization of all outputs by leveraging task relatedness [36, 35]. Multi-task learning (MTL) is not a new concept; however, it has shown some promising results recently [37, 38]. In the past, it was mostly used in natural language understanding (NLU) or vision and speech recognition [39, 35, 36], but now, it is equally famous in other domains especially image processing and computer vision [36].

Fig. 3.

Simple MTL (hard parameter sharing scheme)

MTL models can be used in a variety of ways depending on the architecture.

Soft parameter–sharing mode

Hard parameter–sharing mode

Cross-stitch mode

The approach followed in our proposed model is a hard parameter–sharing approach in which one backbone network is shared among multiple prediction networks/tasks as can be seen in Fig. 3.

Proposed MTL Architecture

The simple block diagram of the proposed model with 3 prediction outputs is shown in Fig. 4. Every model is created on some baseline architecture. The proposed 6-layered MTL model is inspired by the conventional U-Net-like encoder-decoder–based model; however, the architecture is extended for multiple outputs. The model is optimized for three outputs, i.e., classification as HGG/LGG, segmentation of tumor area, and survival prediction in days. The model takes in the pre-processed 3D MRI volumes of size 128 × 128 of all four sequences from BraTS 2019 and 2020 datasets and gives the output for each of the respective tasks. It was designed with limited parameters for building an efficient architecture. A simple MTL equation with 3 predictions for three tasks can be written as:

| 1 |

where is the input samples and is the corresponding labels for each task. The fully functional complete MTL model with details of each block is shown in Fig. 5. Each respective block is explained below.

Fig. 4.

Proposed 3D MTL scheme

Fig. 5.

3D MTL Architecture with multi-scale feature attention

Input Block

The input block consists of 3D MRI volumes with their respective ground truths for three tasks. As the underlying technology is based on supervised learning, we have used raw images along with ground truths. As the model gives outputs for three tasks, three different ground truths are used and fed into the model for a combination of different MRI modalities. Further details about the selected MRI data are explained below.

Dataset Selection

Brain tumor segmentation challenge (BraTS) is a renowned worldwide challenge happening since 2012. The organizers launch a huge amount of brain MRI datasets every year for research [5, 10]. The data provided by BraTS contain images of patients with high-grade gliomas (HGGs) and low-grade gliomas (LGGs). BraTS 2019 dataset with 278 volumes and BraTS 2020 with 302 volumes are used in the proposed scheme. Four MRI sequences have been provided by the organizers, i.e., T1, T2, Flair, and T1CE. Each volume consists of 1 mm3 voxel size with a dimension of 240 × 240 × 155 where 155 is the total number of slices. Each of the four sequences plays a vital role in significant feature extraction pertinent to a specific task.

We used a combination of these sequences for a better understanding and analysis to make an efficient and reduced complexity architecture. Table 1 shows the distribution of BraTS datasets used in the proposed research.

Table 1.

Dataset distribution

| 3D MRI volumes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Entity | BraTS 2019 | BraTS 2020 |

| Total volumes | 278 | 302 |

| Total HGG | 212 | 236 |

| Total LGG | 66 | 66 |

| Training data | 195 | 211 |

| Validation data | 28 | 31 |

| Test data | 55 | 60 |

Each case from the selected BraTS dataset was unzipped, and all volumes of different sequences were stored in separate folders. Ground truths were saved in a separate folder. Survival data is contained in a CSV file, so only the information on survival rate in days was taken and stored in a separate folder as NumPy arrays for the data generator. The procedure was repeated for both datasets (2019 and 2020).

Three types of models were tested using combinations of MRI sequences, i.e., the 3D model with only flair sequence, the 3D model with flair and T2, and finally, the 3D model with all four sequences. Each of the four sequences has different attributes and qualities that help in learning a different and useful feature for prediction. Flair shows edema clearly while T1CE shows enhancing tumor as a bright spot.

Pre-processing Block

Pre-processing was done to make the data clean and more acceptable concerning the model. It is also done to remove any noise in the image which may occur during transferring and/or acquiring images, converting them into different formats, etc. As can be seen in Fig. 5, the pre-processing block consists of brain area cropping to reduce class imbalance problems in MRI images due to the small foreground area and large background. The background of MRI images usually contains no information and overfits the model, so we dropped some rows and columns and extracted the complete brain area with minimum black borders.

After that, z-score normalization has been performed by subtracting the mean from each image and then dividing the image by its standard deviation. z-score normalization converts the data into a standard format to reduce gradient exploding or gradient vanishing problems. Finally, the volumes are resized to 128 × 128 × 128 to reduce the computational complexity of the system. Figure 6 shows unprocessed data with ground truth and processed data with processed masks for visualizing the effects of pre-processing.

Fig. 6.

a Unprocessed data of Flair, T1, T2, and T1CE and b the corresponding processed data with c processed mask for visualizing the effects of pre-processing

Shared Encoder Layers

A shared encoder performs the function of feature extraction as it consists of consecutive convolutional layers that have the capability of learning low-level to high-level features. It converts the image () into a set of feature maps () depending on the number of filters applied at each layer. The general shared encoder functionality can be explicitly described by the equation shown below:

| 2 |

Five (5) convolutional blocks have been used at the encoder side. Each convolutional block is made up of two convolution layers, ReLU activation function, a batch normalization layer and a max pooling layer. As convolution is performed using filters, filters of size (3,3) are used at each convolutional block. A total of 256 filters are used till the last layer of the encoder starting from a filter size of 16. The batch normalization layer not only helps the model converge faster but also plays a vital role in decreasing the gradient explode problem in the network [40]. Max pooling of size (2,2,2) is used to reduce the feature vector which consequently reduces overfitting and helps in efficient and concrete learning [41]. The complete set of operations as explained above that makes up the convolutional block can be represented in an equation form as:

| 3 |

where is the original image, is the 2-dimensional convolutional operation, is the activation function, and is the batch normalization layer while is the max pooling layer. This complete set of operations makes one convnet block. The shared feature representation extracted using the 3D MRI volumes is then forwarded separately to the task specific layers for prediction of each respective output.

Task-Specific Layers

The individual task prediction layers after the backbone (share layers) in an MTL model can be composed of any number of layers, and any type of model can be used depending on the requirement. In the proposed scenario, all three task prediction models have a different number of layers and are composed of different deep learning strategies.

The task-specific layers dedicated for the classification task classify the input 3D MRI volume as either HGG/LGG by assigning the number 0 to HGG volume and 1 to LGG volume. The feature vector for preforming classification was directly taken from the output of the last layer of backbone architecture (encoder). Afterwards, the classification prediction was reached by using three (3) dense layers followed by SoftMax activation function. Various operations performed on the combined feature map obtained from the encoder layers make up the task specific layers for classification nd can be written in equation form as:

| 4 |

Segmentation divides the input volume into three overlapping classes, i.e., whole tumor (WT), core tumor (TC), and enhancing tumor (ET). Segmentation prediction was done by using a decoder having 5 deconvolutional blocks after the backbone architecture. Feature concatenation is performed using deconvolutional blocks to generate the mask corresponding to each input MRI image. Each deconvolutional block consists of one up-sampling layer with filters of size (2 × 2 × 2), a concatenation layer, a dropout layer with 0.5% drop rate, 2 convolutional layers, and finally batch normalization layer. Feature concatenation in the form of skip connections is used to predict the mask for the input/test images. The complete set of operations that make up deconvolutional block can be represented in equation form as:

| 5 |

Finally, the last set of feature maps obtained after the fifth deconvolutional block is passed through one dimensional convolutional layer and sigmoid activation function to get the final prediction. The final set of operations can be represented as:

| 6 |

Survival prediction as the name suggests estimates the total number of days a person will stay alive keeping in mind their current health condition. Survival prediction was a regression problem, so it was done using five (5) dense layers and a linear activation function after taking the output from the last layer of the backbone (encoder). The set of operations responsible for survival prediction can be written as:

| 7 |

Multi-scale Feature Attention Block

The multi-scale feature attention block as already explained earlier is made by passing the output of each deconvolutional block through 2 × 2 pooling layers with consecutively reducing filter size that help in decreasing the feature maps from previous layers. The reduced attention maps obtained from each deconvolutional block can be represented in an equation form as:

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

Afterwards, the three reduced feature maps of same size are concatenated with the output of the first deconvolutional block of decoder to get an enhanced feature attention map. This last attention map is upsampled and concatenated with the output of the last deconvolutional block to get the final segmentation output. The improved segmentation output using the concatenated attention maps can be represented by:

| 12 |

The attention also helps in better loss optimization for other tasks by reducing the loss in the segmentation prediction. In general, feature concatenation from previous layers tends to retain the low-level information in the deep layers hence improving the efficiency of the model output [7].

MTL Loss Function

The most important factor in MTL models that control the learning ability, feature sharing ability, and feature transfer ability of each task is the combined loss that travels through the shared network, then splits and again is combined during backward propagation for loss weight optimization. The loss function is an important parameter that tells us the validity of our proposed model by comparing the results with the ground truth/labels. So mainly, the loss should be minimized for increased accuracy and improved efficiency. In the proposed scheme, we have used three types of loss with different loss weights as we are solving three types of problems.

There is always uncertainty about loss optimization; however, we tried to maintain a balance between the loss of all three tasks. For more than 1 task, weighted loss for each task is combined using algebraic sum which is then used for optimization. For the proposed scheme, the loss weight used for classification was w1 = 0.01, for segmentation it was w2 = 10, and for survival prediction, it was chosen to be w3 = 0.001. These values were selected because they gave the optimum results after extensive experimentation. Values other than these were also tested but gave very poor results. The combined cost function can be represented in equation forms as:

| 13 |

| 14 |

where is the branch number in multitask learning, that is, in our approach, is the task-specific weight, and is the loss for task . Cross entropy was used to calculate for classification. is the loss in the segmentation task that was calculated using dice loss while is the loss in the survival prediction task, and it was calculated using mean absolute error. Loss optimization was one of the biggest challenges in making an optimal 3D MTL architecture with an acceptable prediction power. Segmentation task loss was given high loss weight due to the complexity of the task while classification and survival loss was given low weight.

Optimizer

The main responsibility of any optimizer is to make the model converge faster by reducing loss during backpropagation learning. RMSprop has been used for all experiments with different model settings because it gave the optimum results for each task.

Training and Hyperparameter Tuning

Training the model means making the model learn by extracting low- to high-level features and optimizing the model using the combined loss function. Hyperparameters are all those entities that can be varied to get better results, e.g., batch size, filters, epochs, loss weights, learning rate, dropouts. The proposed model was trained on 100 epochs and took 6 h for 2 modalities and 8 h in the case of 4 modalities.

Results

Dataset Preparation

All four sequences of both datasets are first pre-processed. Pre-processing is done in the same way as already explained under the “Pre-processing Block” section. Pre-processed data is then stored in separate folders for effective usage. We made separate NumPy arrays for one (Flair), two (Flair, T2), and all four sequences (Flair, T1, T2, T1CE) depending upon the experimentation to be performed. The dataset was randomly divided into training, validation, and test data. Eighty percent of the data was used for training while 20% was used for validation/testing purposes.

Hardware and Software Used

Two types of systems have been used. Results with batch size 1 have been acquired using the GPU Titan-X Pascal with 128 GB RAM. The experimentations with batch size 32 were not supported using this system, so they were performed by using the online GPU-based system provided by Kaggle [42] and Collab pro version [43] provided by Google. Python language was used for the complete programming using the Jupyter platform [44]. The code was written in Keras while different libraries were used separately for different tasks.

Performance Metrics

Accuracy

Accuracy is the estimated number of images that were predicted correctly by the model. Classification into HGG and LGG tasks has been evaluated using accuracy. The formula used for estimating classification accuracy is represented by equation 15 below.

| 15 |

where TP is true positive, TN is true negative, FP is false positive, and FN is false negative.

Dice Similarity Coefficient

All types of medical imaging segmentation solutions use dice as the state-of-the-art performance metric as it gives a relative score of similarity per image with the ground truth. It works by comparing the length of each pixel in the image with the corresponding pixel in the ground truth. Higher scores aim for high confidence. The formula used for estimating segmentation dice score is represented by equation 16 below.

| 16 |

where is the ground truth and is the generated mask.

Mean Squared Error (MSE)

Mean squared error (MSE) measures the amount of error in statistical models, especially regression. It assesses the average squared difference between the observed and predicted values. When a model has no error, the MSE equals zero. As model error increases, its value increases. The formula used for estimating survival MSE is represented by equation 17 below.

| 17 |

where is the observed value and is the predicted value.

Classification as HGG and LGG

Glioma is categorized into two types, i.e., high-grade glioma (HGG) and low-grade glioma (LGG) depending upon the severity, physical appearance, chemical composition, and complex nature [1, 45]. The model classifies the input MRI volumes into HGG and LGG. The first leg of the MTL model performs this operation. Table 2 presents the results for classification with three different types of architecture settings. Accuracy has been used as the performance metric. Results of one modality with/without attention, two modalities (flair/T2) with/without attention, and four modalities (with/without attention) have been compared and analyzed separately using batch size 1 and batch size 32.

Table 2.

Results of classification as HGG and LGG on BraTS 2019 and 2020

| Dataset | Modality | Attention block | Training classification accuracy | Validation classification accuracy | Testing classification accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch size 1 and learning rate 0.0001 with RMSprop | |||||

| BraTS 2019 | Flair | No | 0.846 | 0.750 | 0.654 |

| Flair | Yes | 0.979 | 0.857 | 0.872 | |

| Flair + T2 | No | 0.953 | 0.750 | 0.801 | |

| Flair + T2 | Yes | 0.984 | 0.821 | 0.963 | |

| BraTS 2020 | Flair | No | 0.990 | 0.773 | 0.860 |

| Flair | Yes | 0.100 | 0.742 | 0.931 | |

| Flair + T2 | No | 0.995 | 0.838 | 0.916 | |

| Flair + T2 | Yes | 0.800 | 0.838 | 0.766 | |

| Batch Size 32 and learning rate 0.0001 with RMSprop | |||||

| BraTS 2019 | Flair + T2 | Yes | 0.989 | 0.750 | 0.829 |

| BraTS 2020 | Flair + T2 | Yes | 0.995 | 0.935 | 0.950 |

| Batch size 64 with learning rate 0.0001 and RMSprop | |||||

| BraTS 2019 | Flair, T1, T2, T1C | No | 0.100 | 0.942 | 0.951 |

| Yes | 0.979 | 0.821 | 0.854 | ||

| BraTS 2020 | Flair, T1, T2, T1C | No | 0.919 | 0.806 | 0.733 |

| Yes | 0.943 | 0.903 | 0.916 | ||

Bold values refer to the best performing models each for two sequences and four sequences

The best model with two sequences was the one with batch size 32 using BraTS 2020. The results of this model are shown in bold in Table 2. It gave a classification accuracy of 95% on the test dataset. It can also be noted that the model performed better when two MRI modalities were used. This is because the increased feature set has helped the model in better generalization ability.

Similarly, the best model with four sequences is shown in bold in Table 2. It gave a classification accuracy of 94% on the test dataset. It can be observed that the classification accuracy has decreased because of underfitting due to shallow architecture and its inability to learn extended features of four sequences. The class imbalance issue has also affected the results of classification as we have more HGG samples than LGG.

Multi-class Segmentation

The second task to be performed by the proposed MTL model was tumor segmentation. Segmentation is termed as pixel-level classification where you assign a label to every pixel. Segmentation of three tumor sub-regions is mainly the target of every automated diagnostic tool because it helps in effective prognosis and surgery [29]. It is the most critical of all tasks, so it was optimized keeping in mind the importance of this task. Three segmentation labels have been provided by the BraTS organizers. They are edema, non-enhancing, and enhancing tumors. The Dice score has been used as the performance metric. The U-Net-inspired MTL model used as the baseline successfully produces masks for any test image from the BraTS 2019 and 2020 datasets. Again, the best model with two sequences for this task is the same as for classification and produces a mean Dice of 75% while the best model with four sequences shows a mean Dice of 86%. These models are shown in bold in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of multi-class segmentation on BraTS 2019 and 2020

| Dataset | Modality | Attention block | Training segmentation Dice | Validation segmentation Dice | Testing segmentation Dice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch size 1 and learning rate 0.0001 with RMSprop | |||||

| BraTS 2019 | Flair | No | 0.749 | 0.681 | 0.475 |

| Flair | Yes | 0.818 | 0.707 | 0.722 | |

| Flair + T2 | No | 0.793 | 0.7061 | 0.747 | |

| Flair + T2 | Yes | 0.788 | 0.700 | 0.691 | |

| BraTS 2020 | Flair | No | 0.810 | 0.700 | 0.729 |

| Flair | Yes | 0.830 | 0.725 | 0.729 | |

| Flair + T2 | No | 0.785 | 0.702 | 0.712 | |

| Flair + T2 | Yes | 0.813 | 0.738 | 0.710 | |

| Batch size 32, learning rate 0.0001 with RMSprop | |||||

| BraTS 2019 | Flair + T2 | Yes | 0.836 | 0.710 | 0.756 |

| BraTS 2020 | Flair + T2 | Yes | 0.862 | 0.752 | 0.742 |

| Batch size 64 with learning rate 0.0001 and RMSprop | |||||

| BraTS 2019 | Flair, T1, T2, T1C | No | 0.880 | 0.859 | 0.863 |

| Yes | 0.866 | 0.817 | 0.774 | ||

| BraTS 2020 | Flair, T1, T2, T1C | No | 0.845 | 0.852 | 0.817 |

| Yes | 0.832 | 0.859 | 0.802 | ||

Bold values refer to the best performing models each for two sequences and four sequences

Figure 7 shows the results of the best model for multi-class segmentation using two modalities while Fig. 8 shows the results of the best model with four modalities. All three classes, i.e., necrotic core/non-enhancing tumor, edema, and enhancing tumors are shown in different colors. It can be observed that the enhancing tumor core was not detected properly either with the model using two sequences or four sequences. The main reason is its extremely small and variable size as compared to other tumor classes, i.e., edema and non-enhancing tumor. This problem is called class-imbalance, and it has severely affected the detection of enhancing tumor in both HGG and LGG volumes. It can be concluded that the batch size and increased training set do affect the output performance and increase the generalization ability of the model.

Fig. 7.

Multiple outputs using the BraTS 2020 dataset with the best model using two sequences along with uncertainty estimation against each mask predicted

Fig. 8.

Multiple outputs using the BraTS 2020 dataset with the best model using four sequences along with uncertainty estimation against each mask predicted

Survival Prediction (in Days)

The survival prediction task estimates the lifespan of a patient with a given MRI scan. BraTS dataset contains the comma-separated value (CSV) files having clinical information of the patients along with actual survival in days for each case. Given survival was used as the ground truth in each case. The survival of only HGG patients was listed in the CSV file. So, literature was reviewed and found that almost 7 years is the average survival [130] of patients with LGG. Keeping that in mind, 2600 was set as the average survival in days of LGG patients after consultation with local doctors and radiologists. MAE and MSE are used as performance metrics. This task is a regression problem as the model must predict some continuous values, so a linear activation function was used.

As can be seen in Table 4, the models with different batch sizes and MRI sequence combinations successfully predicted the survival in days for each test case with different MSE. The best one shown in bold predicts the overall survival with MAE as low as 244.25 days for the validation dataset with a combination of two sequences. The best model with four sequences is also shown in bold and gives the best MAE of 456.59 days for the test data. If we closely observe the difference in the results obtained with a combination of two and four sequences, the latter is more stable while the former is random in its results and does not show a pattern. This is because an increase in data has improved learning. It was also observed that the model predicts the survival of low-grade gliomas with high mean square error as compared to high-grade gliomas due to the class imbalance issue between both classes (more HGG cases and less LGG cases).

Table 4.

Results of survival prediction on BraTS 2019 and 2020 with different batch sizes and different combinations of sequences

| Dataset | Modality | Attention block | Training | Validation | Testing | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival MAE (days) | Mean squared error | Survival MAE (days) | Mean squared error | Survival MAE (days) | Mean squared error | |||

| Batch size 1 and learning rate 0.0001 and RMSprop | ||||||||

| BraTS 2019 | Flair | No | 536.93 | 655183 | 602.63 | 971960.50 | 767.71 | 1192586 |

| Flair | Yes | 124.16 | 52883.10 | 759.60 | 1109947 | 598.44 | 779794 | |

| Flair + T2 | No | 236.39 | 179488.43 | 833.62 | 1310097.62 | 657.50 | 916284.87 | |

| Flair + T2 | Yes | 191.65 | 87443.23 | 546.33 | 682155.62 | 560.89 | 874878.93 | |

| BraTS 2020 | Flair | No | 106.99 | 23755.46 | 699.50 | 929758.12 | 522.38 | 727780.30 |

| Flair | Yes | 126.34 | 36202.23 | 697.88 | 1030573 | 353.48 | 358022.71 | |

| Flair + T2 | No | 138.64 | 39907.79 | 519.38 | 496939.31 | 593.12 | 842750.31 | |

| Flair + T2 | Yes | 129.49 | 37016.62 | 424.10 | 410986.46 | 400.33 | 428525.18 | |

| Batch size 32 with learning rate 0.0001 and RMSprop | ||||||||

| BraTS 2019 | Flair + T2 | Yes | 128.80 | 33479.75 | 634.93 | 912442.12 | 512.58 | 633241.68 |

| BraTS 2020 | Flair + T2 | Yes | 120.63 | 31701.14 | 388.44 | 263091 | 244.25 | 139688.75 |

| Batch size 64 with learning rate 0.0001 and RMSprop | ||||||||

| BraTS 2019 | Flair, T1, T2, T1C | No | 73.14 | 10709.48 | 448.81 | 264552.46 | 456.59 | 462130.31 |

| Flair, T1, T2, T1C | Yes | 73.28 | 12459.93 | 562.92 | 599336.94 | 454.17 | 405980.66 | |

| BraTS 2020 | Flair, T1, T2, T1C | No | 195.63 | 93430.18 | 468.07 | 488229.44 | 579.72 | 770501.63 |

| Flair, T1, T2, T1C | Yes | 190.07 | 75686.70 | 597.50 | 601147.38 | 454.43 | 455172.97 | |

Bold values refer to the best performing models each for two sequences and four sequences

Significance of Attention Block for All Three Tasks

As can be seen in Table 2, 3, and 4 that two types of results have been presented, one with attention and one without attention. The mathematical composition of the attention block has already been explained in the attention block heading under the methodology section while the systematic overview of its working is shown in Fig. 9. While the high-level feature map provides sophisticated semantic information on brain tumors, the low-level feature map has a wealth of boundary information about brain tumors [2]. By using the encoder block’s skip connections, the network is better able to extract global features. In addition, the attention mechanism is used to selectively extract key feature information from the output feature maps of different levels of decoder blocks. To get the final output of segmentation, the multi-scale feature maps are fused [6]. The attention block takes all the low-level to high-level features and merges them in the final output to retain maximum information.

Fig. 9.

Feature-guided attention block

If one looks closely at all three tables (Table 2, 3, 4), then, it can be observed that the results of the model with two sequences are affected much with the MSFA block and showed improved performance as compared to the model not using MSFA. On the other hand, the model with four sequences does not get much affected with the use of the MSFA block in terms of performance. There is little to no difference between the results of the model with MSFA and the model without MSFA. It can be concluded that attention networks can only work well when there is less data but can deviate the network away from convergence when enough data is available making loss optimization worse in case of multiple tasks.

Uncertainty Estimation

In deep learning, uncertainty is the presence of doubt about the predicted outputs. It tells us about the confidence level of the model on the predicted output so that more attention can be given to uncertain areas or pixels [46]. Deep learning has achieved extraordinary success in many sectors, but it has been acknowledged that clinical diagnosis calls for particular vigilance when using modern deep learning algorithms because erroneous predictions might have serious repercussions [5]. The AI-based diagnosis method, however, frequently makes false predictions and missclassifications [5]. As a result, AI has not been extensively used in the field of medicine yet [5]. The type of uncertainty measured in the proposed research is epistemic uncertainty which is categorized as the uncertainty of the model parameters [46] [47]. It decreases with increased training set size [48, 47]. Literature has proved dropouts to be a very clear indication of the uncertainty of the model if they are used while testing [5]. A statistical method called Monte Carlo (MC) dropout sampling was combined with the baseline model to quantify the degree of uncertainty in the baseline forecast.

We sampled T = 100 sets of parameters (weights and biases) dropping out feature maps at test time in segmentation using MC dropout to produce various estimates of the (multi-class) segmentation. We may calculate T outputs per voxel per class based on those parameters, which represent samples from the prediction distribution. The Bayesian model averaging of the MC dropout ensemble determining the mean of the class-specific prediction distribution at a voxel level may be obtained from this sample as follows [134]:

| 18 |

where represents the class specific MC dropout distribution for a given input x and voxel j while represents the class-specific MC dropout distribution for a given input x, voxel j, and class c which gives us the epistemic uncertainty maps. In the proposed case, each image was passed T = 100 times through the model to account for the uncertainty estimation. The epistemic uncertainty of the proposed model can be visualized intuitively in Figs. 7 and 8. The uncertain pixels for some of the images predicted through the best model with two modalities can be seen in Fig. 7 while Fig. 8 shows the uncertain pixels of the images predicted using the best model with four modalities. The colored dots show those pixels that were predicted with less confidence by the model on every pass, so they were captured by our uncertainty prediction model.

It is evident from the images of Fig. 7 that the border areas and most of the area of enhancing core have not been predicted with satisfied accuracy and hence were displayed as uncertain pixels. If we look at the images of Fig. 8 closely, we can see that only the pixels on the border areas of three parts of the glioma tumor are shown as uncertain pixels. So, it can be concluded by comparing the uncertainty maps of Figs. 7 and 8 that the increased training set size used for the results of Fig. 8 has improved the performance of the model for better generalization ability along all three classes of glioma.

Discussion

The motivation behind this work was to make a very efficient, less complex, and end-to-end model that can perform more than one task and give predictions simultaneously without human intervention. The model was mainly developed to work as a screening tool for assisting clinicians. This is the main reason to opt for a shallow model. Secondly, we also studied the effects of modalities, batch size, and attention block on the classification accuracy, segmentation dice score, and survival MSE in days for both datasets (2019, 2020) and recorded the results.

As can be seen in Table 2, 3, and 4, the learning rate and optimizer have not been changed because the combination of learning rate = 0.0001 and RSMprop optimizer gave the best results for all other parameters. It is already known that small learning rates converge slower while larger learning rates converge faster which may skip some important details, so keeping that in mind, we tuned this parameter and found 0.0001 to be the best. A learning rate lower than 0.0001 overfits the model and gives extremely poor results for both datasets. Furthermore, it was noted that for shallow architectures, we do not need to train for many epochs as it makes the model overfit. The Dice score started to decrease when we increased the epochs to 150 or 200 or decreased it below 100, so we decided to stick to 100 based on our observation. Batch size, attention block, and combination of MRI sequences were varied accordingly throughout the whole experimentation procedure.

It can be easily concluded from the results of classification, segmentation, and survival prediction presented in Table 2, 3, and 4 that the segmentation results have improved when we increased the data from 2 to 4 modalities, but no significant change occurred in case of classification while survival results got reduced and did not perform well for attention or without attention. It can be because of the lack of complexity of the model and its inability to generalize well for new data inputs.

The graphs of classification accuracy, segmentation Dice score, and survival MSE for the best-performing models are shown in Figs. 10 and 11. The graphs show the behavior of three performance metrics for 100 epochs. The slow convergence of loss because of the small learning rate in each case is obvious from the graphs. It can also be visualized that the model has performed well on training data but shows unstable behavior in the case of the validation dataset and shows irregular spikes for all three tasks. This can be due to a small validation dataset. These variations also show that the model needs to be trained on deeper layers for smooth validation curves. When comparing both Figs. 10 and 11, it can be noticed that the graphs of Fig. 11 are more stable over 100 epochs while the graphs of Fig. 10 are more random for all three tasks. This is because of the increased training set size with the addition of two more modalities in the results of Fig. 11 which helps in faster convergence and improved generalization ability.

Fig. 10.

Graphs showing model performance over 100 epochs for metrics corresponding to three different tasks with two sequences

Fig. 11.

Graphs showing model performance over 100 epochs for metrics corresponding to three different tasks with four sequences

Radiomic features along with machine learning techniques have become quite famous for 1–2 years, but they increase the model complexity due to the overhead of a separate feature extraction module combined with a separate machine learning module for classification. Cascaded networks are also being used to boost model performance, but they also increase computational complexity. Conventionally, separate models are being used for each of the three tasks which also adds delays in the prediction results along with time and computation complexity. These types of models cannot be used easily in a clinical setting as they take an increased amount of execution time and are not user-friendly. However, the current study presents a very lightweight reduced complexity model with predictions for all three tasks simultaneously. It only uses deep learning techniques to simultaneously give predictions without the need to have radiomics and machine learning.

Comparisons with Other Studies

Multi-task learning has attracted the attention of researchers during the last few years because an efficient end-to-end system capable of performing multiple tasks at once in a clinical setting is in high demand. In this regard, a lot of studies have surfaced in the past 5 years to exploit the unseen capabilities of MTL models and to cater to the associated problems of loss optimization and task relationship learning. Unfortunately, very few studies have utilized MTL for medical imaging. Literature review also proved that MTL is showing some promising results when multiple outputs are expected from the limited data. As already stated, this type of model has not been used in the way we have used it so we could not find relevant studies that have performed three tasks simultaneously using one model. For a fair comparison, we have mentioned MTL-related studies that have done any of the three tasks in Table 5 and compared the results of each of the three tasks separately with some recent state-of-the-art studies in the respective context in Table 6.

Table 5.

Extensive comparisons with MTL-related studies

| Study ref | Classification accuracy | Segmentation mean Dice score | Survival MSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| MTL studies | |||

| [49] | ––- | 86.74 | ––- |

| [50] | ––- | 82.00 | ––- |

| [51] | ––- | 78.00 | ––- |

| [21] | ––- | 85.20 | ––- |

| [19] | ––- | 82.90 | ––- |

| [20] | ––- | 85.02 | ––- |

| Proposed model (two sequences) |

Val—94.00 Test—95.00 |

Val—75.00 Test—74.00 |

Val—263,091 Test—139,688.75 |

| Proposed model (four sequences) |

Val—94.20 Test—95.13 |

Val—86.00 Test—86.30 |

Val—264,552.46 Test—462,130.31 |

Bold values refer to the best performing models each for two sequences and four sequences

Table 6.

Comparisons with recent deep learning techniques

| Study Ref | Classification accuracy | Segmentation mean Dice score | Survival MSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison with recent studies for classification | |||

| [52] | 95.0 | –- | –- |

| [53] | 75.0 | –- | –- |

| [54] | 77.0 | –- | –- |

| [55] | 76.0 | –- | –- |

| Comparison with recent studies for segmentation | |||

| [56] | –- | 74.33 | –- |

| [57] | –- | 83.72 | –- |

| [58] | –- | 83.36 | –- |

| [16] | –- | 86.44 | –- |

| Comparison with recent studies for survival prediction | |||

| [59] | –- | –- | 392,963.2 |

| [60] | –- | –- | 417,633.26 |

| [61] | –- | –- | 100,053.08 |

| [25] | –- | –- | 115,424.30 |

| Proposed model (two sequences) |

Val—0.94 Test—0.95 |

Val—75.00 Test—74.00 |

Val—263,091 Test—139,688.75 |

| Proposed model (four sequences) |

Val—94.20 Test—95.13 |

Val—86.00 Test—86.30 |

Val—264,552.46 Test—462,130.31 |

Bold values refer to the best performing models each for two sequences and four sequences

It is clear from Table 5 and 6 that our proposed models performed well in all three tasks, i.e., classification, segmentation, and survival prediction. The reason for not performing much higher than the mentioned studies can be that other models are only dealing with one loss while the proposed model is optimizing three tasks simultaneously. Only one of the studies has used detection as one of the many tasks while others have used different tasks for the output, e.g., one study has shown segmentation of edema as one task and segmentation of enhancing + non-enhancing tumor as the other task [19]. Most importantly, the reported studies have either used 2D models or used an input image size of 240 × 240 while we have used a 3D model with an input size 128 × 128 which limits the performance. Multiple models for multiple tasks do exist in literature but no single model to date is present that is doing the complete brain tumor analysis using the MTL model as proposed.

The results in Table 6 show that both best models also performed quite well in the classification task. It can also be concluded that the attention model has helped it in improved learning and loss optimization. Furthermore, the shared representation learning due to the shared backbone also helps in mutual information sharing thus improving gradient optimization using backpropagation. The results of the segmentation Dice scores are comparable with the Dice scores of both Table 5 and 6 and performed well.

Similarly, if we can observe the results of the studies related to the survival prediction task in Table 5 and 6, then one can easily see that our model with two sequences has performed well both in the case of validation and testing scores as compared to other complex models while the results of the model with four sequences have underperformed in this case due to the reasons of underfitting. We have performed survival using the deep learning model and no radiomic or any other feature extraction mechanism has been used. No machine learning techniques are employed for regression. It means deep learning alone can bring extraordinary results without the need for advanced feature extraction mechanisms.

Existing systems either work for one task only or are not suitable for clinical setup due to certain limitations. It is evident from the results of Table 5 and 6 that the proposed deep learning MTL model has the potential to replace all existing techniques for brain tumor analysis due to certain advantages, i.e., reduced complexity of pre-processing, one baseline model with multiple outputs, all-in-one end-to-end system for clinical purpose. Existing systems either work for one task only or are not suitable for clinical setup due to certain limitations.

Complexity Analysis

Computational complexity of a deep learning model includes both the network complexity in terms of parameters and the resources required. Table 7 compares the proposed model inference time (testing time for one subject). It can be seen easily that the proposed model has the least inference time for one subject with all four modalities (T1, T2, Flair, T1CE).

Table 7.

Comparisons of inference time with some state-of-the-art models

Inference time is important for doctors and patients as well because the responsiveness of the tool has significance in timely diagnosis which will lead to timely prognosis in real time and treatment planning. The model has been designed in such a way to work as an assistive tool for radiologists with the least test run time (test time) per patient.

Similarly, Table 8 shows a quick comparison of the training time which is important for reproducibility of any deep learning model. The table clearly depicts that our model takes the least amount of time in training leading to least resource utilization.

Table 8.

Comparison of training time with some state-of-the-art models

| Models reference | Year | Training time | Hardware |

|---|---|---|---|

| [62] | 2020 | 29 h | NVIDIA GTX 1080Ti |

| [63] | 2020 | 19 h | NVIDIA GTX 1080Ti |

| [69] | 2019 | 48 h |

NVIDIA Tesla V100 32 GB |

| [70] | 2020 | 96–120 h | NVIDIA Tesla V100-SXM2 with 16 GB |

| [71] | 2022 | 37.5 h | NVIDIA A100 40G GPU |

| [72] | 2022 | 1750 h | NVIDIA DGX-1 V (8 × V100 32 GB) |

| Proposed model | 2023 | 8 h | Titan X Pascal and P100 (Kaggle) |

A lot of models are being produced regularly and are uploaded on many sharing portals like GitHub but not all can be reproduced due to the unavailability of high computational resources, but the proposed model has been made keeping in mind the resources that are available freely like Google Colab and Kaggle. The model can easily be trained on these platforms without any additional resource requirements.

Table 9 shows a comparison of the computational complexity of using three models vs one model. The table clearly shows that our model is much more efficient in terms of deployment and scalability options because of the smaller number of total trainable parameters. The proposed model gives three predictions as outcome along with uncertainty estimation with reduced number of parameters and training time.

Table 9.

Comparison of network size of three separate models for classification/segmentation/survival prediction vs one model for all

Conclusion and Future Prospects

U-Net-inspired 3D MTL models with reduced complexity were proposed in this paper. The paper aimed to highlight the efficiency of the MTL architecture in combining multiple tasks and predicting the outputs simultaneously to create an end-to-end model for clinical setup to assist radiologists. We have used MTL with hard parameter sharing and split it at the end into three tasks, i.e., classification, segmentation, and survival prediction. Uncertainty estimation was also performed to analyze and access the confidence level of the model on the predictions. The training was done on the famous BraTS datasets (2019–2020). The complexity is reduced by using a very simple 5-layer model and very nominal data preprocessing. Complexity analysis has also been done to prove the efficiency of the proposed scheme.

The model classifies the input MRI volumes of glioma patients as HGG or LGG, performs multi-class segmentation on 3D volumes, and predicts the overall survival duration in days. Loss weight and learning rate were optimized for all three tasks. Extensive experiments were done for fair comparisons using different model settings and MRI sequence combinations. Results show an improved classification accuracy of 95.1%, mean dice score of 86.3%, and survival MAE of 456.59 in a combined setting. Moreover, a comparison with related MTL studies also shows that the model is competent enough to beat them.

Although promising, our technique has several drawbacks. First, because this was a retrospective study, the dataset utilized in it had a small sample size, which harmed the model’s robustness. We used the BraTS MRI volumes by reducing their size from 240 × 240 × 155 to 128 × 128 × 128 due to hardware limitations which also affected the performance due to loss of information. This reduced input size refrained the model from learning useful information which may have been lost during pre-processing. Class imbalance issues between HGG and LGG as already mentioned in Table 1 also affected the classification task. The inter-class imbalance between the three tumor classes shown in the sample ground truth of Fig. 6 also gave poor results for the enhancing tumor in the segmentation task. Lastly, the model is yet to be tested on a local dataset for local deployment.

The results completely declare that deep learning alone has the potential to surpass human intelligence with far better accuracy. The power of deep learning is continuously challenging and unpredictable. The proposed MTL scheme has the potential to give tough competition to complex methodologies like radiomics with multi-cascaded networks and machine learning techniques. The future of the proposed methodology is promising and is a big step towards the hidden possibilities of MTL architecture in healthcare. More data can improve the segmentation dice score of training and validation sets. In the future, the idea is to analyze results by adding additional clinical information and fine-tuning the model using local datasets. Another idea is to use a deeper model along with an augmentation technique to further improve the segmentation Dice. Other auxiliary tasks can be introduced in classification and survival tasks to improve segmentation.

Uncertainty quantification can be an important indicator towards fixing AI mistakes and improving its performance. A methodology for incorporating uncertainty could effectively point out incorrect predictions. Currently, the model only shows its uncertainty for each case, but we also plan to use this uncertainty estimation to further improve the model predictions. With a little expansion, the suggested model can effectively change inaccurate predictions by making use of uncertainty. This will build the confidence level of doctors in AI-based assistive tools for medical disease diagnosis.

MTL models are promising for exploiting task relationships between similar tasks. Overall, the proposed architecture in its current setting is fully ready to be deployed in a clinical setup. The model will surely help in improving and revolutionizing healthcare standards by providing a timely and accurate diagnosis. It is quite evident that hopefully soon, early diagnosis using the proposed MTL model will be able to replace biopsies taking the healthcare sector to the next level.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of their friends for supporting and helping in every way possible.

Author Contribution

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Maria Nazir. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Maria Nazir and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Dr. Sadia Shakil and Dr. Khurram Khurshid proofread and reviewed all the versions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was not supported by any individual or organization.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the online BraTS Challenge Dataset repository available at [https://www.med.upenn.edu/cbica/brats2019/data.html] [https://www.med.upenn.edu/cbica/brats2020/data.html].

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.M. Nazir, S. Shakil, and K. Khurshid, “Role of deep learning in brain tumor detection and classification (2015 to 2020): A review,” Comput. Med. Imaging Graph., vol. 91, no. May, 2021, 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2021.101940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D. Hee Lee and S. N. Yoon, “Application of artificial intelligence-based technologies in the healthcare industry: Opportunities and challenges,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 1–18, 2021, 10.3390/ijerph18010271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.S. Ahuja, B. K. Panigrahi, and T. K. Gandhi, “Enhanced performance of Dark-Nets for brain tumor classification and segmentation using colormap-based superpixel techniques,” Mach. Learn. with Appl., vol. 7, no. March 2021, p. 100212, 2022, 10.1016/j.mlwa.2021.100212.

- 4.S. Vidyadharan, B. V. V. S. N. Prabhakar Rao, Y. Perumal, K. Chandrasekharan, and V. Rajagopalan, “Deep Learning Classifies Low- and High-Grade Glioma Patients with High Accuracy, Sensitivity, and Specificity Based on Their Brain White Matter Networks Derived from Diffusion Tensor Imaging,” Diagnostics, vol. 12, no. 12, 2022, 10.3390/diagnostics12123216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.J. Lee, D. Shin, S. H. Oh, and H. Kim, “Method to Minimize the Errors of AI: Quantifying and Exploiting Uncertainty of Deep Learning in Brain Tumor Segmentation,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 6, 2022, 10.3390/s22062406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.X. He, W. Xu, J. Yang, J. Mao, S. Chen, and Z. Wang, “Deep Convolutional Neural Network With a Multi-Scale Attention Feature Fusion Module for Segmentation of Multimodal Brain Tumor,” Front. Neurosci., vol. 15, no. November, pp. 1–9, Nov. 2021, 10.3389/fnins.2021.782968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D. Xu, X. Zhou, X. Niu, and J. Wang, “Automatic segmentation of low-grade glioma in MRI image based on UNet++ model,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser., vol. 1693, no. 1, 2020, 10.1088/1742-6596/1693/1/012135.

- 8.Z. Liu et al., “Deep learning based brain tumor segmentation: a survey,” Complex Intell. Syst., vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1001–1026, 2022, 10.1007/s40747-022-00815-5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.K. T. Islam, S. Wijewickrema, and S. O’leary, “A Deep Learning Framework for Segmenting Brain Tumors Using MRI and Synthetically Generated CT Images,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 2, 2022, 10.3390/s22020523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.W. W. Lin, J. W. Lin, T. M. Huang, T. Li, M. H. Yueh, and S. T. Yau, “A novel 2-phase residual U-net algorithm combined with optimal mass transportation for 3D brain tumor detection and segmentation,” Sci. Rep., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–16, 2022, 10.1038/s41598-022-10285-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.T. Kalaiselvi, S. T. Padmapriya, P. Sriramakrishnan, and K. Somasundaram, “Deriving tumor detection models using convolutional neural networks from MRI of human brain scans,” Int. J. Inf. Technol., pp. 2–7, 2020, 10.1007/s41870-020-00438-4.

- 12.A. Veeramuthu et al., “MRI Brain Tumor Image Classification Using a Combined Feature and Image-Based Classifier,” Front. Psychol., vol. 13, no. March, pp. 1–12, 2022, 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.848784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.S. Montaha, S. Azam, A. K. M. R. H. Rafid, M. Z. Hasan, A. Karim, and A. Islam, “TimeDistributed-CNN-LSTM: A Hybrid Approach Combining CNN and LSTM to Classify Brain Tumor on 3D MRI Scans Performing Ablation Study,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 60039–60059, 2022, 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3179577. [Google Scholar]

- 14.K. R. Laukamp et al., “Automated Meningioma Segmentation in Multiparametric MRI: Comparable Effectiveness of a Deep Learning Model and Manual Segmentation,” Clin. Neuroradiol., vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 357–366, 2021, 10.1007/s00062-020-00884-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.R. A. Zeineldin, M. E. Karar, J. Coburger, C. R. Wirtz, and O. Burgert, “DeepSeg: deep neural network framework for automatic brain tumor segmentation using magnetic resonance FLAIR images,” Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg., vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 909–920, 2020, 10.1007/s11548-020-02186-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.M. Brain, T. Segmentation, Y. Chen, M. Yin, Y. Li, and Q. Cai, “CSU-Net : A CNN-Transformer Parallel Network for,” pp. 1–12, 2022.

- 17.M. Aggarwal, A. K. Tiwari, M. P. Sarathi, and A. Bijalwan, “An early detection and segmentation of Brain Tumor using Deep Neural Network,” BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak., vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2023, 10.1186/s12911-023-02174-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Y. Wang and X. Ye, “U-Net multi-modality glioma MRIs segmentation combined with attention,” 2023 Int. Conf. Intell. Supercomput. BioPharma, ISBP 2023, pp. 82–85, 2023, 10.1109/ISBP57705.2023.10061312.

- 19.G. Cheng, J. Cheng, M. Luo, L. He, Y. Tian, and R. Wang, “Effective and efficient multitask learning for brain tumor segmentation,” J. Real-Time Image Process., vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 1951–1960, Dec. 2020, 10.1007/s11554-020-00961-4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.C. Zhou, C. Ding, X. Wang, Z. Lu, and D. Tao, “One-Pass Multi-Task Networks With Cross-Task Guided Attention for Brain Tumor Segmentation,” IEEE Trans. Image Process., vol. 29, pp. 4516–4529, 2020, 10.1109/TIP.2020.2973510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]