Abstract

Background

Gene fusions can be used as tools for functional prediction and also as evolutionary markers. Fused genes often show a scattered phyletic distribution, which suggests a role for processes other than vertical inheritance in their evolution.

Results

The evolutionary history of gene fusions was studied by phylogenetic analysis of the domains in the fused proteins and the orthologous domains that form stand-alone proteins. Clustering of fusion components from phylogenetically distant species was construed as evidence of dissemination of the fused genes by horizontal transfer. Of the 51 examined gene fusions that are represented in at least two of the three primary kingdoms (Bacteria, Archaea and Eukaryota), 31 were most probably disseminated by cross-kingdom horizontal gene transfer, whereas 14 appeared to have evolved independently in different kingdoms and two were probably inherited from the common ancestor of modern life forms. On many occasions, the evolutionary scenario also involves one or more secondary fissions of the fusion gene. For approximately half of the fusions, stand-alone forms of the fusion components are encoded by juxtaposed genes, which are known or predicted to belong to the same operon in some of the prokaryotic genomes. This indicates that evolution of gene fusions often, if not always, involves an intermediate stage, during which the future fusion components exist as juxtaposed and co-regulated, but still distinct, genes within operons.

Conclusion

These findings suggest a major role for horizontal transfer of gene fusions in the evolution of protein-domain architectures, but also indicate that independent fusions of the same pair of domains in distant species is not uncommon, which suggests positive selection for the multidomain architectures.

Background

Gene fusion leading to the formation of multidomain proteins is one of the major routes of protein evolution. Gene fusions characteristically bring together proteins that function in a concerted manner, such as successive enzymes in metabolic pathways, enzymes and the domains involved in their regulation, or DNA-binding domains and ligand-binding domains in prokaryotic transcriptional regulators [1,2,3]. The selective advantage of domain fusion lies in the increased efficiency of coupling of the corresponding biochemical reaction or signal transduction step [1] and in the tight co-regulation of expression of the fused domains. In signal transduction systems, such as prokaryotic two-component regulators and sugar phosphotransferase (PTS) systems, or eukaryotic receptor kinases, domain fusion is the main principle of functional design [4,5,6]. Furthermore, accretion of multiple domains appears to be one of the important routes for increasing functional complexity in the evolution of multicellular eukaryotes [7,8,9].

Pairs of distinct genes that are fused in at least one genome have been termed fusion-linked [3]. A gene fusion is presumably fixed during evolution only when the partners cooperate functionally and, by inference, a functional link can be predicted to exist between fusion-linked genes. Recently, this simple concept has been used by several groups as a means of systematic prediction of the functions of uncharacterized genes [1,2,3,10,11].

In addition to their utility for functional prediction, analysis of gene fusions may help in addressing fundamental evolutionary issues. Gene fusions often show scattered phyletic patterns, appearing in several species from different lineages. By investigating the phylogenies of each of the two fusion-linked genes, it may be possible to determine the evolutionary scenario for the fusion itself. A recent study provided evidence that the fission of fused genes occurred during evolution at a rate comparable to that of fusion [12]. Here, we address another central aspect of the evolution of gene fusions, namely, do fusions of the same domains in different phylogenetic lineages reflect vertical descent, possibly accompanied by multiple lineage-specific fission events, or independent fusion events, or horizontal transfer of the fused gene? In other words, is a fusion of a given pair of genes extremely rare and, once formed, is it spread by horizontal gene transfer (HGT) perhaps also followed by fissions in some lineages? Alternatively, are independent fusions of the same gene pair in distinct lineages relatively common during evolution? Among fusions that are found in at least two of the three primary kingdoms of life (Bacteria, Archaea and Eukaryota), we detected both modes of evolution, but horizontal transfer of a fused gene appeared to be more common than independent fusion events or vertical inheritance with multiple fissions.

Results and discussion

To distinguish between a single fusion event followed by HGT and/or fission of the fused gene and multiple, independent fusion events in distinct organisms, we analyzed phylogenetic trees that were constructed separately for each of the fusion-linked domains (proteins). The fusion was split into the individual component domains and phylogenetic trees were built for each of the corresponding orthologous sets from 32 complete microbial genomes (Figure 1, and see Materials and methods), including both fusion components and products of stand-alone genes. The topologies of the resulting trees were compared to each other and to the topology of a phylogenetic tree constructed on the basis of a concatenated alignment of ribosomal proteins, which was chosen as the (hypothetical) species tree of the organisms involved [13]. If the fusion events either occurred independently of each other or were vertically inherited, perhaps followed by fission in some lineages, the distribution of the fusion components in the phylogenetic trees for the orthologous clusters to which they belong is expected to mimic the distribution of the species carrying the fusion in the species tree. In contrast, if the fusion gene has been disseminated by HGT, fusion components will form odd clusters different from those in the species tree.

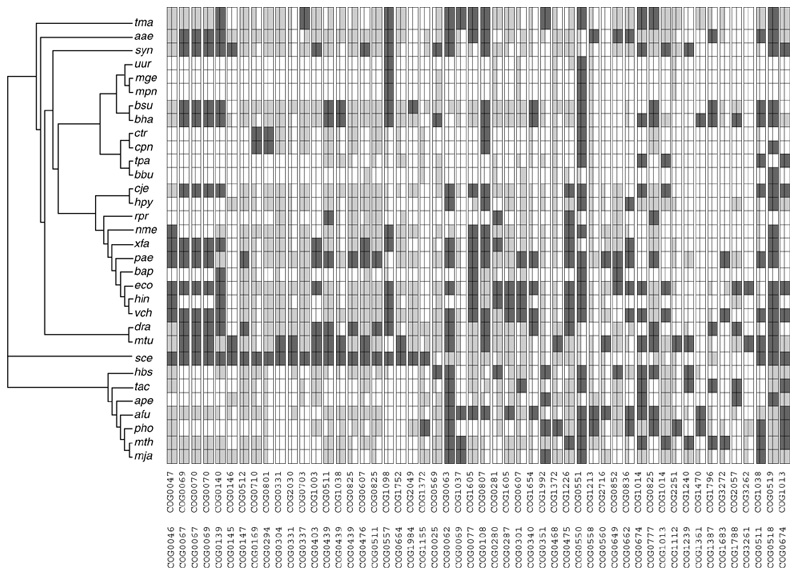

Figure 1.

Phyletic patterns of fusion-linked COGs. Each pair of COGs is represented by a double column. The dark-gray rectangles indicate fusions, the light-gray rectangles indicate that the fusion components are represented by stand-alone genes in the given genomes, and the white rectangles indicate that there is no representative of the given COG in the given genome. Where one rectangle in a double column is light gray and the other is white, the genome in question has a representative of only one of the pair of fusion-linked COGs. Species abbreviations are as listed in Materials and methods.

This could be a straightforward approach to reconstructing the evolutionary history of gene fusions, if only the topology of the species trees was well resolved. However, this is not necessarily the case for bacteria or archaea, where relationships between major lineages remain uncertain [14,15], although a recent detailed analysis suggested some higher-level evolutionary affinities [13]. Because the distinction between the three primary kingdoms is widely recognized [14,16] and is clear in the trees for most protein families [17], trans-kingdom horizontal transfers of fused genes can be more reliably detected with the proposed approach. Therefore, we concentrated on the evolutionary histories of gene fusions that are shared by at least two of the three primary kingdoms.

As the framework for this analysis, we used the database of clusters of orthologous groups (COGs) of proteins [18,19], which contains sets of orthologous proteins and domains from complete microbial genomes (32 genomes at the time of this analysis; see Materials and methods). Domain fusions represented in some genomes by stand-alone versions of the fusion components are split in the COG database so that each fusion component can be assigned to a different COG. Whenever distinct domains of a fusion protein belong to separate COGs, the corresponding COGs are said to be fusion-linked [3]. A search of the COGs database revealed 405 pairs of fusion-linked COGs. The vast majority (87%) of fusion links include fusion present in only one primary kingdom (Table 1). Only 52 pairs of fusion-linked COGs included fusions represented in two or three kingdoms (Table 1), and for reasons discussed above, we chose these pairs of COGs for an evolutionary analysis of gene fusions.

Table 1.

Phyletic patterns of gene fusions

| Kingdom profile* | Number of fusion links between COGs |

| abe | 3 |

| ab- | 27 |

| -be | 20 |

| a-e | 1 |

| a-- | 82 |

| -b- | 215 |

| --e | 56 |

| Total | 405 |

*a, Archaea; b, Bacteria; e, Eukaryota.

Figure 1 shows a genome-COG matrix that reveals the phyletic (phylogenetic) patterns of the presence or absence of the orthologs across the spectrum of the sequenced genomes [18] for each of the 52 pairs of fusion-linked COGs containing cross-kingdom fusions. When assessed against the topology of the tentative species tree based on the concatenated alignments of ribosomal proteins [13], fusions showed a scattered distribution in phyletic patterns (depicted by columns in Figure 1). For example, the fusion between COG1788 and COG2057 (α and β subunits of acyl-CoA: acetate CoA transferase) is seen in the bacteria Escherichia coli, Deinococcus radiodurans and Bacillus halodurans, and in the archaea Aeropyrum pernix, Thermophilus acidophilum and Halobacterium sp. Similarly, the fusion between COG1683 and COG3272 (uncharacterized, conserved domains) was found in the bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Vibrio cholerae, and in the archaeon Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. In each of these cases, with the species tree used as a reference, the bacteria involved are phylogenetically distant from each other and more so from the archaea, and non-fused versions of the two domains exist within the same bacterial lineages and in archaea (Figure 1). These observations emphasize the central question of this work: are the fusions between the same pair of domains in different species independent or are they best explained by HGT?

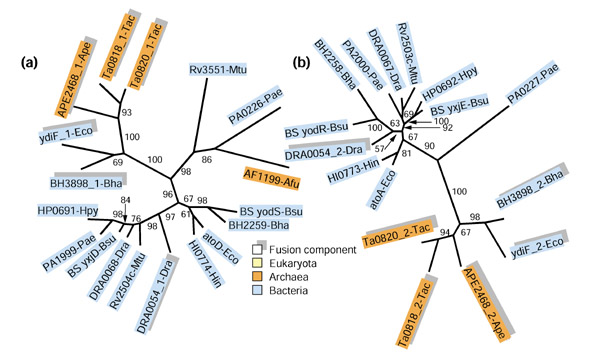

Figure 2 shows the pair of phylogenetic trees for the fusion-linked COGs 1788 and 2057. In both trees, the fusion components from E. coli and B. halodurans (YdiF and BH3898, respectively) confidently group with the archaeal fusion components, to the exclusion of the non-fused orthologs. This position of the E. coli and B. halodurans fusion components is unexpected and is in contrast to the placement of the orthologs from other gamma-proteobacteria and Gram-positive bacteria, as well as non-fused paralogs from the same species (AtoA/D and BH2258/2259, respectively) within the bacterial cluster. These observations strongly suggest that the gene for fused subunits of acyl-CoA: acetate CoA transferase was disseminated horizontally between E. coli, B. halodurans, and archaea. The presence of non-fused paralogs in both these bacterial species appears to be best compatible with gene transfer from archaea to bacteria. In contrast, the fusion of the pair of domains from the same COGs seen in D. radiodurans seems to be an independent event because, in both trees, the D. radiodurans branch is in the middle of the bacterial cluster (Figure 2a,2b). Thus, the history of this pair of fusion-linked COGs appears to involve horizontal transfer of the fused gene between bacteria and archaea (and possibly also within kingdoms), as well as at least one additional, independent fusion event in bacteria.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic trees for fusion-linked COGs: α and β subunits of acyl-CoA:acetate CoA transferase. Fusion components are denoted by shading and by a number after an underline (_1 for the amino-terminal domain and _2 for the carboxy-terminal domain). The three primary kingdoms are color-coded as indicated in the figure. The RELL bootstrap values are indicated for each internal branch. (a) α subunit (domain) (COG1788); (b) β subunit (domain) (COG2057). The proteins are designated using the corresponding systematic gene names followed (after the underline) by the abbreviated species names. Species abbreviations are as in Materials and methods and Figure 1.

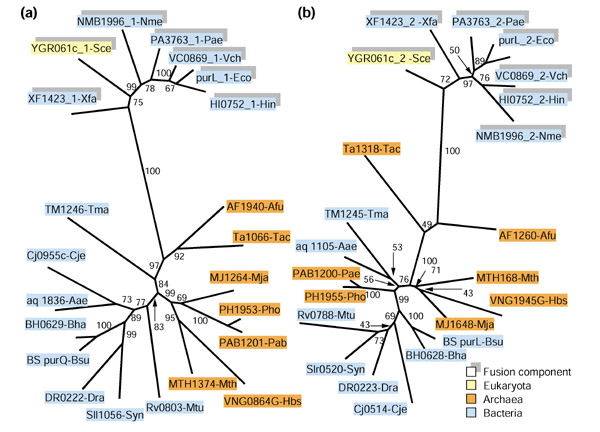

Figure 3 shows the phylogenetic trees for the two domains of phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine (FGAM) synthase, a purine biosynthesis enzyme. The components of this fusion, which is found in proteobacteria and eukaryotes, form a tight cluster separated by a long internal branch from the non-fused bacterial and archaeal orthologs. This tree topology suggests HGT between bacteria and eukaryotes, possibly a relocation of the fused gene from the pro-mitochondrion to the eukaryotic nuclear genome or, alternatively, gene transfer from eukaryotes to proteobacteria. An additional aspect of the evolution of this gene is the apparent acceleration of evolution upon gene fusion, which is manifest in the long branch that separates the proteobacterial-eukaryotic cluster from the rest of the bacterial and archaeal species (Figure 3a,3b).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic trees for fusion-linked COGs: phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine (FGAM) synthase. (a) Synthetase domain (subunit) (COG0046); (b) glutamine amidotransferase domain (subunit) (COG0047). Protein designations are as in Figure 2.

The fusion-linked COGs 1605 and 0077 (chorismate mutase and prephenate dehydratase, respectively) show a more complicated history, with distinct fusion events resulting in different domain architectures (see legend to Figure 4). The presence, in both trees, of two distinct clusters of fusion components and the isolated fusion in Campylobacter jejuni suggest at least three independent fusion events, two of which apparently were followed by horizontal dissemination of the fused gene (Figure 4a,4b). The single archaeal fusion, the Arachaeoglobus fulgidus protein AF0227, belongs to one of these clusters and shows a strongly supported affinity with the ortholog from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. (Figure 4a,4b). Given the broad distribution of this fusion in bacteria, horizontal transfer of the bacterial fused gene to archaea is the most likely scenario.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic trees for fusion-linked COGs: chorismate mutase and prephenate dehydratase. (a) Chorismate mutase (COG1605); (b) prephenate dehydratase (COG0077). Protein designations are as in Figure 2. The protein AF0227 contains a prephenate dehydrogenase domain in addition to the chorismate mutase and prephenate dehydratase domains.

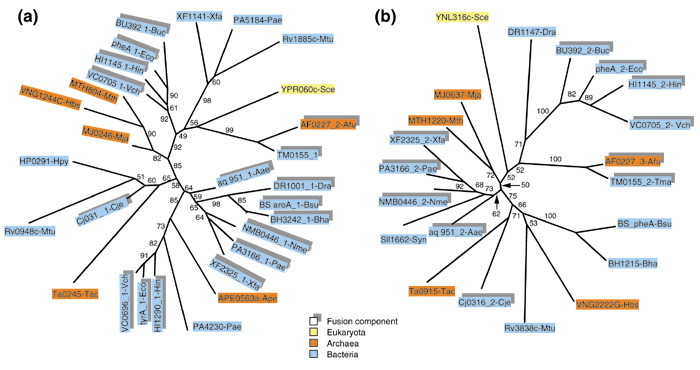

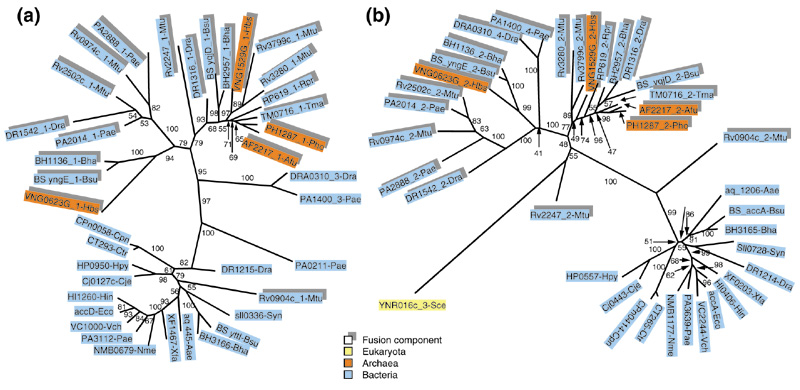

The pair of fusion-linked COGs 0777 and 0825 (α and β subunits of acetyl-CoA carboxylase, respectively) shows unequivocal clustering of the fusion components from numerous archaeal and bacterial species, which indicates a prevalent role for HGT in the evolution of this fusion (Figure 5a,5b). Moreover, archaea are scattered among bacteria, suggesting multiple HGT events. However, an apparent independent fusion is seen in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Figure 5a,5b). It could be argued that, in cases like those in Figure 5, where there is a sharp separation (a long, strongly supported internal branch in each of the trees) between the fusion components and stand-alone proteins, the COGs involved needed to be reorganized, to form one COG consisting of fusion proteins only and two separate COGs consisting of stand-alone proteins. Formally, this would eliminate the need for HGT as an explanation of the tree topology for any of these new COGs. However, this solution (even if attractive from the point of view of classification) does not seem to be correct in light of the principle of orthology that underlies the COG system: it appears that, in both of the COGs involved, the fusion components and stand-alone proteins are bona fide orthologs, as judged by the high level of sequence conservation and by the fact that, in the majority of species involved, they are the only versions of this key enzyme.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic trees for fusion-linked COGs: α and β subunits of acetyl-CoA carboxylase. (a) β subunit (domain) (COG0777); (b) α subunit (domain) (COG0825). Protein designations are as in Figure 2. The proteins DRA0310 and PA1400, in addition to the domains corresponding to the α and β subunits of acetyl-CoA carboxylase, contain a biotin carboxylase domain and a biotin carboxyl carrier protein domain. The clustering of these proteins in phylogenetic trees almost certainly reflects HGT between the respective bacterial lineages.

The results of phylogenetic analyses of the 51 cross-kingdom fusion links are summarized in Tables 2 and 3 and the Additional data. In 31 of the 51 links, an inter-kingdom horizontal transfer of the fused gene appeared to be the evolutionary mechanism by which the fusion entered one of the kingdoms. In contrast, only 14 fusion-linked pairs of COGs show evidence of independent fusion in two kingdoms, and in just two cases, the fusion seems to have been inherited from the last universal common ancestor. The latter two scenarios were distinguished on the basis of the parsimony principle, that is, by counting the number of evolutionary events (fusions or fissions) that were required to produce the observed distribution of fusion components and stand-alone versions of the domains involved across the tree branches. Accordingly, it needs to be emphasized that we can only infer the most likely scenario under the assumption that the probabilities of fusion and fission are comparable. It cannot be ruled out that some of the scenarios we classify as independent fusions in reality reflect the existence of an ancestral fused gene and subsequent multiple, independent fissions. The detection of ancestral domain fusions may call for the unification of the respective COG pairs in a single COG, with the species in which fission occurred represented by two distinct proteins.

Table 2.

Evolutionary history of trans-kingdom gene fusions

| COG A | Protein function | COG B | Protein function | Kingdom pattern* | Principal mode of evolution† | Fusion | Gene juxtaposition‡ | Evolutionary scenario |

| COG0046 | Phospho-ribosyl-formylglycinamidine (FGAM) synthase, synthetase domain | COG0047 | Phospho-ribosyl-formyl-glycinamidine (FGAM) synthase glutamine Amidotransferase domain | -be | HGT | Ecol, Paer, Vcho, Hinf, Xfas, Nmen | Pyro, Paby, Tmar, Drad, Bsub, Bhal | One fusion event, fused gene transfer between eukaryotes and proteobacteria |

| COG0067 | Glutamate synthase domain 1 | COG0069 | Glutamate synthase domain 2 | -be | HGT | Most bacteria | Aful, Mjan, Tmar | One fusion event, fused gene transfer between eukaryotes and bacteria |

| COG0067 | Glutamate synthase domain 1 | COG0070 | Glutamate synthase domain 3 | -be | HGT | Most bacteria | - | One fusion event, fused gene transfer between eukaryotes and bacteria |

| COG0069 | Glutamate synthase domain 2 | COG0070 | Glutamate synthase domain 3 | -be | HGT | Most bacteria | Aful, Mjan, Mthe | One fusion event, fused gene transfer between eukaryotes and bacteria |

| COG0139 | Phospho-ribosyl-AMP cyclohydrolase (histidine biosynthesis) | COG0140 | Phospho-ribosyl-ATP pyrophospho-hydrolase (histidine biosynthesis) | -be | Most bacteria | - | Uncertain | |

| COG0145 | N-methylhydaintoinase A | COG0146 | N-methylhydaintoinase B | -be | HGT | Mtub, Syne, Scer | Mjan, Aero, Hpyl | One fusion event, fused gene transfer between eukaryotes and (the ancestor of) Cyanobacteria and Actinomycetes |

| COG0147 | Anthranilate/para-aminobenzoate synthase component I | COG0512 | Anthranilate/para-aminobenzoate synthase component II | -be | IFE | Nmen, Cjej, Paer, Scer | Aful, Mthe, Taci, Aero, Tmar, Drad, Bsub, Bhal, Ecol, Vcho, Xfas | Independent fusion events in eukaryotes and bacteria |

| COG0169 | Shikimate 5-dehydrogenase | COG0710 | 3-dehydro-quinate dehydratase | -be | IFE | Ctra, Cpne, Scer | Paby¶Ecol | Independent fusion events in eukaryotes and bacteria |

| COG0294 | Dihydropteroate synthase | COG0801 | 7,8-dihydro-6-hydroxymethylpterin-pyrophosphokinase | -be | IFE | Ctra, Cpne, Scer | Llac¶, Tmar, Drad, Bsub, Bhal | Independent fusion events in eukaryotes and bacteria |

| COG0304 | 3-oxoacyl-(acyl-carrier-protein) synthase | COG0331 | (acyl-carrier-protein) S-malonyl-transferase | -be | HGT | Mtub, Scer | Drad, Ecol, Vcho | One fusion event, fused gene transfer between eukaryotes and bacteria |

| COG0331 | 3-oxoacyl-(acyl-carrier-protein) synthase | COG2030 | Acyl dehydratase | -be | HGT | Mtub, Bsub, Scer | - | Fused gene transfer between eukaryotes and Actinomycetes; additional, independent fusions in bacteria |

| COG0337 | 3-dehydroquinate synthetase | COG0703 | Shikimate kinase | -be | IFE | Tmar, Scer | Drad, Mtub, Proteo-bacteria, Ctra, Cpne | Independent fusion events in eukaryotes and bacteria (with different domain organizations) |

| COG0403 | Glycine cleavage system protein P (pyridoxal-binding), amino-terminal domain | COG1003 | Glycine cleavage system protein P (pyridoxal-binding), carboxy-terminal domain | -be | HGT | Drad, Mtub, Syne, Ecol, Paer, Xfas, Nmen | Hbsp, Pyro, Taci, Aero, Tmar, Bsub, Bhal | One fusion event, fused gene transfer between eukaryotes and proteobacteria |

| COG0439 | Biotin carboxylase | COG0511 | Biotin carboxyl carrier protein | -be | HGT | Hbsp, Mtub, Rpxx, Scer | Bhal, Ecol, Paer Vcho, Hinf, Xfas, Nmen, Hpyl, Ctra, Cpne | One fusion event, fused gene transfer between eukaryotes and bacteria; additional, independent fusions in bacteria |

| COG0439 | Biotin carboxylase | COG1038 | Pyruvate carboxylase, carboxy-terminal domain/subunit | -be | HGT | Bsub, Scer | Mjan | One fusion event, fused gene transfer between eukaryotes and bacteria; subsequent domain accretion in eukaryotes |

| COG0439 | Biotin carboxylase | COG0825 | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase α-subunit | -be | HGT | Mtub, Scer | Hbsp, Rpxx | One fusion event, fused gene transfer between eukaryotes and bacteria; subsequent domain accretion in eukaryotes |

| COG0476 | Dinucleotide-utilizing enzyme involved in molybdopterin and thiamine biosynthesis | COG0607 | Rhodanese-related sulfurtransferase | -be | IFE | Mtub, Syne, Paer, Scer | - | Independent fusion events in x sulfurtransferase |

| COG0511 | Biotin carboxyl carrier protein | COG0825 | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase α-subunit | -be | IFE | Drad, Paer, Scer | Pyro, Tmar, Hbsp¥ | Independent fusion events in eukaryotes and bacteria |

| COG0664 | cAMP-binding domain | COG1752 | Esterase | -be | HGT | Mtub, Ccre||, Scer | - | One fusion event, fused gene transfer between eukaryotes and actinomycetes; an additional, independent fusion event in bacteria |

| COG1984 | Allophanate hydrolase subunit 2 | COG2049 | Allophanate hydrolase subunit 1 | -be | IFE | Bsub, Scer | Most bacteria | Independent fusion events in eukaryotes and bacteria |

| COG1155 | Archaeal/vacuolar-type H+-ATPase subunit A | COG1372 | Intein | a-e | IFE | Taci, Pyro, Scer | - | Independent fusion events in eukaryotes and archaea |

| COG0025 | Na+/H+ and K+/H+ antiporters | COG0569 | K+ transport systems, NAD-binding component | ab- | Hbsp, Bhal, Syne | - | Uncertain | |

| COG0062 | Uncharacterized, conserved protein | COG0063 | Predicted sugar kinase | ab- | AF | All archaea; all bacteria that have COG0062 | NA | One ancestral fusion; fission in eukaryotes |

| COG0069 | Glutamate synthase domain 2 | COG1037 | Ferredoxin-like domain | ab- | HGT | Aful, Mjan, Mthe, Tmar; (all that have COG1037) | NA | One ancestral fusion; fused gene transfer from archaea to bacteria (Thermotoga) |

| COG0077 | Prephenate dehydratase | COG1605 | Chorismate mutase | ab- | HGT | Aful, Aqua, Tmar, Ecol, Vcho, Paer, Hinf, Xfas, Nmen, Cjej | - | Fused gene transfer between bacteria and archaea (Archaeoglobus and Thermotoga lineages); additional, independent fusions in bacteria |

| COG0108 | 3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone 4-phosphate synthase | COG0807 | GTP cyclohydrolase II | ab- | Aful, Aqua, Tmar, Drad, Mtub, Bsub, Bhal, Syne, Paer, Vcho, Xfas, Nmen, Hpyl, Cjej, Ctra, Cpne | - | Uncertain | |

| COG0280 | Phosphotransacetylase | COG0281 | Malic enzyme | ab- | HGT | Hbsp, Ecol, Hinf, Xfas, Rpxx | - | One fusion event, fused gene transfer from bacteria to archaea (Halobacterium) |

| COG0287 | Prephenate dehydrogenase | COG1605 | Chorismate mutase | ab- | IFE | Aful, Ecol, Vcho, Hinf | Taci, Aero, Ccre | Independent fusion events in archaea and bacteria |

| COG0301 | ATP pyrophosphatase (thiamine biosynthesis) | COG0607 | Rhodanese-related sulfurtransferase | ab- | IFE | Taci, Ecol, Vcho, Paer, Hinf | - | Independent fusion events in archaea and bacteria |

| COG0340 | Biotin-(acetyl-CoA carboxylase) ligase | COG1654 | Biotin operon repressor | ab- | HGT | Aful, Paby, Drad, Bsub, Bhal, Ecol, Paer, Vcho, Xfas; (all that have COG1654) | NA | One fusion event, fused gene transfer from bacteria to archaea (Archaeoglobus) |

| COG0351 | Hydroxymethyl-pyrimidine/phospho-methylpyrimidine kinase | COG1992 | Uncharacterized conserved protein | ab- | HGT | Hbsp, Mjan, Pyro, Aero, Tmar | - | One fusion event, fused gene transfer from archaea to bacteria (Thermotoga) |

| COG0468 | RecA/RadA recombinase | COG1372 | Intein | ab- | IFE | Hbsp, Pyro, Mtub | NA | Independent fusion events in archaea and bacteria |

| COG0475 | Kef-type K+ transport systems, membrane component | COG1226 | Kef-type K+ transport systems, NAD-binding component | ab- | HGT | Mthe, Ecol, Paer, Hinf, Xfas, Nmen, Cjej, Rpxx | - | One fusion event, fused gene transfer from bacteria to archaea (Methanobacterium) |

| COG0550 | Topoisomerase IA | COG0551 | Zn-finger domain associated with topoisomerase type IA | ab- | AF | Most bacteria and archaea | - | One ancestral fusion with subsequent fission in Aper, Aqua |

| COG0558 | Phosphatidyl-glycerophosphate synthase | COG1213 | Predicted sugar nucleotidyltransferase | ab- | HGT | Aful, Pyro, Aqua | Aero | One fusion event, fused gene transfer from archaea to bacteria (AquIFEx) |

| COG0560 | Phosphoserine phosphatase | COG2716 | ACT-domain-containing protein | ab- | Aful, Mtub, Paer | - | Uncertain | |

| COG0649 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit 7 | COG0852 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase 27 kD subunit | ab- | HGT | Hbsp, Aqua, Ecol, Paer | Most archaea and bacteria | One fusion event, fused gene transfer from bacteria to archaea (Halobacterium) |

| COG0662 | Mannose-6-phosphate isomerase | COG0836 | Mannose-1-phosphate guanylyltransferase | ab- | HGT | Aful, Pyro, Aqua, Ecol, Paer, Vcho, Xfas, Hpyl, Cjej | - | Fused gene transfer from bacteria to archaea; a second, independent fusion event in bacteria |

| COG0674 | Pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase and related 2-oxoacid:ferredoxin oxidoreductases, alpha subunit | COG1014 | Pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase and related 2-oxoacid:ferredoxin oxidoreductases, gamma subunit | ab- | HGT | Aful, Hbsp, Taci, Aero, Mtub, Bhal, Syne, Ecol, Vcho, Tpal | Mjan, Mthe, Aqua, Tmar, Hpyl, Cjej | Fused gene transfer from archaea to bacteria; a second, independent fusion event in bacteria |

| COG0777 | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase β subunit | COG0825 | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase α subunit | ab- | HGT | Aful, Hbsp, Pyro, Tmar, Drad, Mtub, Bsub, Bhal, Paer, Rpxx | - | Fused gene transfer from bacteria to archaea; a second, independent fusion event in bacteria |

| COG1013 | Pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase and related 2-oxoacid:ferredoxin oxidoreductases, beta subunit | COG1014 | Pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase and related 2-oxoacid:ferredoxin oxidoreductases, gamma subunit | ab- | IFE | Mthe, Syne, Ecol, Vcho, Tpal | Aful, Taci, Aero, Mtub, Bhal | Independent fusion events in archaea and bacteria |

| COG1112 | Superfamily I DNA and RNA helicases and helicase subunits | COG2251 | Predicted metal-binding domain | ab- | IFE | Pyro, Mtub | - | Independent fusion events in archaea and bacteria |

| COG1239 | Mg-chelatase subunit ChlI | COG1240 | Mg-chelatase subunit ChlD | ab- | HGT | Hbsp, Mthe, Taci, Mtub, Syne | Mjan, Paer | Fused gene transfer between bacteria and archaea, with subsequent fissions |

| COG1361 | S-layer domain | COG1470 | Predicted membrane protein | ab- | HGT | Aful, Pyro, Bhal | - | One fusion event, fused gene transfer from archaea to bacteria |

| COG1387 | Histidinol phosphatase and related hydrolases of the PHP family | COG1796 | DNA polymerase IV (family X) | ab- | HGT | Mthe, Taci, Drad, Bsub, Bhal; (all prokaryotes that have COG1796) | NA | One fusion event, fused gene transfer between archaea to bacteria |

| COG1683 | Uncharacterized conserved protein | COG3272 | Uncharacterized conserved protein | ab- | HGT | Mthe, Paer, Vcho | - | One fusion event, fused gene transfer between archaea and bacteria (Methanobacterium and Vibrio/Pseudomonas, respectively) |

| COG1788 | Acyl-CoA:acetate CoA transferase alpha subunit | COG2057 | Acyl-CoA:acetate CoA transferase beta subunit | ab- | HGT | Hbsp, Taci, Aero, Drad, Bhal, Ecol | Mtub, Bsub, Paer, Hinf, Hpyl | Fused gene transfer between bacteria and archaea; a second, independent fusion event in bacteria |

| COG3261 | Ni, Fe-hydrogenase III large subunit | COG3262 | Ni, Fe-hydrogenase III component G | ab- | HGT | Paby, Mtub, Ecol | Pyro | One fusion event, fused gene transfer from bacteria to archaea |

| COG0518 | GMP synthase - Glutamine amidotransferase domain | COG0519 | GMP synthase-PP-ATPase domain | abe | HGT | Aero, Scer, most bacteria | Mthe, Pyro, Paby | Fused gene transfer among bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes |

| COG0674 | Pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase and related 2-oxoacid:ferredoxin oxidoreductases, alpha subunit | COG1013 | Pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase and related 2-oxoacid:ferredoxin oxidoreductases, beta subunit | abe | HGT | Aful, Mthe, Taci, Pyro, Paby, Scer, Syne, Ecol, Vcho, Cjej, Tpal | Hbsp, Mjan, Aero, Aqua, Tmar, Mtub, Hpyl | Fused gene transfer from archaea to bacteria (α-proteobacteria) |

*Abbreviations: a, archaea, b, bacteria, e, eukaryotes; a dash indicates that the given kingdom is not represented in at least one of the fusion-linked COGs. †AF, ancestral fusion, HGT, horizontal gene transfer, IFE, independent fusion events. ‡ In several cases, the indicated genes are separated by one to three genes or their order is switched compared to that of the fusion components. §Paby, Pyrococcus abyssi, an archaeal genome not included in the master set of genomes analyzed in this study. ¶Llac, Lactococcus lactis, a bacterial genome not included in the master set of genomes analyzed in this study. ||Ccre, Caulobacter crescentus, a bacterial genome not included in the master set of genomes analyzed in this study. ¥Hbsp, Halobacterium sp., an archaeal genome not included in the master set of genomes analyzed in this study.

Table 3.

Summary of evolutionary scenarios for cross-kingdom gene fusions

| Evolutionary mode* | Number of fusion-linked COG pairs |

| Cross-kingdom horizontal transfer of a fused gene | 31 |

| Independent fusion events | 14 |

| Ancestral fusion | 2 |

| Uncertain | 4 |

| Total | 51 |

*As indicated in Table 2, the evolutionary scenarios for some of the analyzed COGs included both cross-kingdom horizontal transfer and apparent independent gene fusion within one of the kingdoms.

Examination of the genomic context of the genes that encode stand-alone counterparts of the fusion components showed that, in 25 of the 51 cases, these genes were juxtaposed in some, and in certain cases, many prokaryotic genomes (Table 2). This suggests that evolution of gene fusions often, if not always, passes through an intermediate stage of juxtaposed and co-regulated, but still distinct, genes within known or predicted operons. In addition, some of the juxtaposed gene pairs might have evolved by fission of a fused gene.

The results of the present analysis point to HGT as a major route of cross-kingdom dissemination of fused genes. Horizontal transfer might be even more prominent in the evolution of fused genes within the bacterial and archaeal kingdoms. This notion is supported by the topologies of some of the phylogenetic trees analyzed, which show unexpected clustering of bacterial species from different lineages (note, for example, the grouping of D. radiodurans with P. aeruginosa in Figure 5). Massive HGT between archaea and bacteria, particularly hyperthermophiles, has been suggested by genome comparisons [20,21,22,23,24]. However, proving HGT in each individual case is difficult, and the significance of cross-kingdom HGT has been disputed [25,26]. With gene fusions, the existence of a derived shared character (fusion) supporting the clades formed by fusion components and the concordance of the independently built trees for each of the fusion components make a solid case for HGT.

The apparent independent fusion of the same pair of genes (or, more precisely, members of the same two COGs) on multiple occasions during evolution might seem unlikely. However, we found that one-fourth to one-third of the gene fusions shared by at least two kingdoms might have evolved through such independent events, and probable additional independent fusions were noted among bacteria. This could be due to the extensive genome rearrangement characteristic of the evolution of prokaryotes [27,28], and to the selective value of these particular fusions, which tend to get fixed once they emerge.

Materials and methods

The version of the COG database used in this study included the following complete prokaryotic genomes. Bacteria: Aae, Aquifex aeolicus; Bap, Buchnera aphidicola; Bbu, Borrelia burgdorferi; Bsu, Bacillus subtilis; Bhal, Bacillus halodurans; Cje, Campylobacter jejuni; Cpn, Chlamydophila pneumoniae; Ctr, Chlamydia trachomatis; Dra, Deinococcus radiodurans; Eco, Escherichia coli; Hin, Haemophilus influenzae; Hpy, Helicobacter pylori; Mge, Mycoplasma genitalium; Mpn, Mycoplasma pneumoniae; Mtu, Mycobacterium tuberculosis; Nme, Neisseria meningitidis; Pae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Rpr, Rickettsia prowazekii; Syn, Synechocystis sp.; Tma, Thermotoga maritima; Tpa, Treponema pallidum; Vch, Vibrio cholerae; Xfa, Xylella fastidiosa. Eukaryote: Sce, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Archaea: Ape, Aeropyrum pernix; Afu, Archaeoglobus fulgidus; Hbs, Halobacterium sp.; Mja, Methanococcus jannaschii; Mth, Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum; Pho, Pyrococcus horikoshii; Pab, Pyrococcus abyssi; Tac, Thermoplasma acidophilum.

COGs containing fusion components from at least two of the three primary kingdoms, were selected for phylogenetic analysis. COGs containing 60 or more members were excluded because of potential uncertainty of orthologous relationship between members of such large groups [18]. Multiple alignments were generated for each analyzed COG using the T-Coffee program [29].

Phylogenetic trees were constructed by first generating a distance matrix using the PROTDIST program and the Dayhoff PAM model for amino-acid substitutions and employing this matrix for minimum evolution (least-square) tree building [30] using the FITCH program. The PROTDIST and FITCH programs are modules of the PHYLIP software package [31]. The tree topology was then optimized by local rearrangements using PROTML, a maximum likelihood tree-building program, included in the MOLPHY package [32]. Local bootstrap probability was estimated for each internal branch by using the resampling of estimated log-likelihoods (RELL) method with 10,000 bootstrap replications [33]. The gene order in prokaryotic genomes was examined using the 'Genomic context' feature of the COG database.

Additional data files

Phylogenetic trees for 84 individual COGs presented as 52 pairs of trans-kingdom fusion-linked COGs are available. Bootstrap values (percentage of 1,000 replications) are indicated for each fork. Archaeal proteins are designated by black squares, bacterial proteins by gray squares and eukaryotic proteins by empty squares. Fusion components are denoted by _1, _2, _3, etc. Pylogenetic trees are avaliabel as PDF files for the following individual COGs:

See Table 2 for more details of individual COGs

Supplementary Material

COG0025

COG0046

COG0047

COG0062

COG0063

COG0067

COG0069

COG0070

COG0077

COG0108

COG0139

COG0140

COG0145

cdf2psc: converts a .cdf file into a .psc file.

COG0147

COG0169

COG0280

COG0281

COG0287

COG0294

COG0301

COG0304

COG0331

COG0337

COG0340

COG0351

COG0403

COG0439

COG0468

COG0475

COG0476

COG0511

COG0512

COG0518

COG0519

COG0550

COG0551

COG0558

COG0560

COG0569

COG0607

COG0649

COG0662

COG0664

COG0674

COG0703

COG0710.

COG0777

COG0801

COG0807

COG0825

COG0836

COG0852

COG1003

COG1013

COG1014

COG1037

COG1038

COG1112

COG1155

COG1213

COG1226

COG1239

COG1240

COG1361

COG1372

COG1387

COG1470

COG1605

COG1654

COG1683

COG1752

COG1788

COG1796

COG1984

COG1992

COG2030

COG2049

COG2057

COG2251

COG2716

COG3261

COG3262

COG3272

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Charles DeLisi, Adnan Derti, I. King Jordan, Kira Makarova, Igor Rogozin, and Fyodor Kondrashov for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions.

References

- Marcotte EM, Pellegrini M, Ng HL, Rice DW, Yeates TO, Eisenberg D. Detecting protein function and protein-protein interactions from genome sequences. Science. 1999;285:751–753. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynen MJ, Snel B. Gene and context: integrative approaches to genome analysis. Adv Protein Chem. 2000;54:345–379. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(00)54010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanai I, Derti A, DeLisi C. Genes linked by fusion events are generally of the same functional category: a systematic analysis of 30 microbial genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:7940–7945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141236298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson JS, Kofoid EC. Communication modules in bacterial signaling proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:71–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reizer J, Saier MH., Jr Modular multidomain phosphoryl transfer proteins of bacteria. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:407–415. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T. Signaling - 2000 and beyond. Cell. 2000;100:113–127. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81688-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin EV, Aravind L, Kondrashov AS. The impact of comparative genomics on our understanding of evolution. Cell. 2000;101:573–576. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80867-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin GM, Yandell MD, Wortman JR, Gabor Miklos GL, Nelson CR, Hariharan IK, Fortini ME, Li PW, Apweiler R, Fleischmann W, et al. Comparative genomics of the eukaryotes. Science. 2000;287:2204–2215. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Human Genome Consortium Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright AJ, Ilipoulos I, Kyrpides NC, Ouzounis CA. Protein interaction maps for complete genomes based on gene fusion events. Nature. 1999;402:86–90. doi: 10.1038/47056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin MY, Koonin EV. Who's your neighbor? New computational approaches for functional genomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:609–613. doi: 10.1038/76443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snel B, Bork P, Huynen M. Genome evolution: gene fusion versus gene fission. Trends Genet. 2000;16:9–11. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01924-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf YI, Rogozin IB, Grishin NV, Tatusov RL, Koonin EV. Genome trees constructed using five different approaches suggest new major bacterial clades. BMC Evol Biol. 2001;1:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace NR. A molecular view of microbial diversity and the biosphere. Science. 1997;276:734–740. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichmann SA, Mitchison G. Is there a phylogenetic signal in prokaryote proteins? J Mol Evol. 1999;49:98–107. doi: 10.1007/pl00006538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JR, Doolittle WF. Archaea and the prokaryote-to-eukaryote transition. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:456–502. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.4.456-502.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science. 1997;278:631–637. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Natale DA, Garkavtsev IV, Tatusova TA, Shankavaram UT, Rao BS, Kiryutin B, Galperin MY, Fedorova ND, Koonin EV. The COG database: new developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:22–28. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin EV, Mushegian AR, Galperin MY, Walker DR. Comparison of archaeal and bacterial genomes: computer analysis of protein sequences predicts novel functions and suggests a chimeric origin for the archaea. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:619–637. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4821861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L, Tatusov RL, Wolf YI, Walker DR, Koonin EV. Evidence for massive gene exchange between archaeal and bacterial hyperthermophiles. Trends Genet. 1998;14:442–444. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01553-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson KE, Clayton RA, Gill SR, Gwinn ML, Dodson RJ, Haft DH, Hickey EK, Peterson JD, Nelson WC, Ketchum KA, et al. Evidence for lateral gene transfer between Archaea and Bacteria from genome sequence of Thermotoga maritima. Nature. 1999;399:323–329. doi: 10.1038/20601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle WF. Lateral genomics. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:M5–M8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin EV, Makarova KS, Aravind L. Horizontal gene transfer in prokaryotes: quantification and classification. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:709–742. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrpides NC, Olsen GJ. Archaeal and bacterial hyperthermophiles: horizontal gene exchange or common ancestry? Trends Genet. 1999;15:298–299. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01811-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon JM, Faguy DM. Thermotoga heats up lateral gene transfer. Curr Biol. 1999;9:R747–R751. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80474-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandekar T, Snel B, Huynen M, Bork P. Conservation of gene order: a fingerprint of proteins that physically interact. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:324–328. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01274-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf YI, Rogozin IB, Kondrashov AS, Koonin EV. Genome alignment, evolution of prokaryotic genome organization and prediction of gene function using genomic context. Genome Res. 2001;11:356–372. doi: 10.1101/gr.gr-1619r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J. T-Coffee: A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:205–217. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch WM, Margoliash E. Construction of phylogenetic trees. Science. 1967;155:279–284. doi: 10.1126/science.155.3760.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Inferring phylogenies from protein sequences by parsimony, distance, and likelihood methods. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:418–427. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi J, Hasegawa M. MOLPHY: Programs for Molecular Phylogenetics Tokyo: Institute of Statistical Mathematics; 1992.

- Kishino H, Miyata T, Hasegawa M. Maximum likelihood inference of protein phylogeny and the origin of chloroplasts. J Mol Evol. 1990;31:151–160. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

COG0025

COG0046

COG0047

COG0062

COG0063

COG0067

COG0069

COG0070

COG0077

COG0108

COG0139

COG0140

COG0145

cdf2psc: converts a .cdf file into a .psc file.

COG0147

COG0169

COG0280

COG0281

COG0287

COG0294

COG0301

COG0304

COG0331

COG0337

COG0340

COG0351

COG0403

COG0439

COG0468

COG0475

COG0476

COG0511

COG0512

COG0518

COG0519

COG0550

COG0551

COG0558

COG0560

COG0569

COG0607

COG0649

COG0662

COG0664

COG0674

COG0703

COG0710.

COG0777

COG0801

COG0807

COG0825

COG0836

COG0852

COG1003

COG1013

COG1014

COG1037

COG1038

COG1112

COG1155

COG1213

COG1226

COG1239

COG1240

COG1361

COG1372

COG1387

COG1470

COG1605

COG1654

COG1683

COG1752

COG1788

COG1796

COG1984

COG1992

COG2030

COG2049

COG2057

COG2251

COG2716

COG3261

COG3262

COG3272