Abstract

Background:

Magnetocardiography (MCG) is a novel non-invasive technique that detects subtle magnetic fields generated by cardiomyocyte electrical activity, offering sensitive detection of myocardial ischemia. This study aimed to assess the ability of MCG to predict impaired myocardial perfusion using single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).

Methods:

A total of 112 patients with chest pain underwent SPECT and MCG scans, from which 65 MCG output parameters were analyzed. Using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression to screen for significant MCG variables, three machine learning models were established to detect impaired myocardial perfusion: random forest (RF), decision tree (DT), and support vector machine (SVM). The diagnostic performance was evaluated based on the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC).

Results:

Five variables, the ratio of magnetic field amplitude at R-peak and positive T-peak (RoART+), R and T-peak magnetic field angle (RTA), maximum magnetic field angle (MAmax), maximum change in current angle (CCAmax), and change positive pole point area between the T-wave beginning and peak (CPPPATbp), were selected from 65 automatic output parameters. RTA emerged as the most critical variable in the RF, DT, and SVM models. All three models exhibited excellent diagnostic performance, with AUCs of 0.796, 0.780, and 0.804, respectively. While all models showed high sensitivity (RF = 0.870, DT = 0.826, SVM = 0.913), their specificity was comparatively lower (RF = 0.500, DT = 0.300, SVM = 0.100).

Conclusions:

Machine learning models utilizing five key MCG variables successfully predicted impaired myocardial perfusion, as confirmed by SPECT. These findings underscore the potential of MCG as a promising future screening tool for detecting impaired myocardial perfusion.

Clinical Trial Registration:

ChiCTR2200066942, https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.html?proj=187904.

Keywords: chronic coronary syndromes, magnetocardiography, myocardial perfusion imaging, machine learning algorithm

1. Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD), characterized by atherosclerotic plaque deposition and luminal narrowing of the coronary arteries, is a leading cause of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and chronic coronary syndromes (CCS), contributing significantly to global morbidity and mortality. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines define CCS as a distinct phase of CAD, marked by stable plaques, vascular spasms, or microvascular diseases, and stable periods after ACS—excluding acute thrombotic ruptures [1]. Although coronary angiography (CAG) is recognized as the gold standard for diagnosing CAD, it is unsuitable for patients with CCS who lack obstructive CAD due to its invasiveness and the patient’s relative stability. Consequently, the ESC guidelines recommend a pre-test probability (PTP) of obstructive CAD based on age, sex, and symptoms [1]. Patients with PTP 15% are recommended to undergo non-invasive functional imaging to avoid excessive procedures and costs of these examinations [1]. Since anatomical stenosis of less than 90% of the luminal diameter is not necessarily associated with myocardial ischemia [2, 3], functional tests such as stress cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), stress echocardiography, single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and positron emission tomography (PET), rather than anatomical imaging such as coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA), are required to determine the need for revascularization [1, 2, 3].

Myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI), including SPECT and PET, is regarded as the gold standard for non-invasive detection of abnormal perfusion and helps decision-making for follow-up treatment [4, 5]. These techniques can identify the region and extent of myocardial ischemia and differentiate ischemia from infarction by observing radiotracers extracted by cardiomyocytes at rest and during stress [4, 5]. Compared to initial CAG, MPI-guided therapeutic strategies have been associated with lower rates of revascularization, myocardial infarction (MI), and death in stable CAD patients [6]. However, MPI requires significant time investment, typically necessitating at least 4 h for complete inspection and analysis of results.

Magnetocardiography (MCG) is a novel noninvasive technique for detecting weak magnetic fields generated by the electrical activity of cardiomyocytes [7]. This technique is particularly useful when the heart experiences ischemia or infarction, leading to a reduction in blood flow and insufficient oxygen supply to cardiac cells [8, 9]. This shortage impacts the electrical activity of cardiomyocytes, causing abnormal cardiac depolarization or repolarization and altering the normal magnetic field map [10].

Myocardial ischemia or infarction can induce significant changes in magnetic fields, which are detectable and analyzable through MCG instruments. (1) A potential alteration is the multipolarization or unipolarization of the magnetic field: ischemic conditions may cause uneven electrical activity among cardiomyocytes, leading to a varied distribution of magnetic field intensity across different cardiac regions, typically exhibiting multipolarization patterns [11]. In cases of severe ischemia, unipolarization may occur when the magnetic field is significantly enhanced, primarily in one direction [12]. (2) Another change involves the deflection of the magnetic field angle, as myocardial ischemia can shift the orientation of cardiac electrical activity, causing variability in the direction of the magnetic field on the MCG [13]. (3) Additionally, an evident pole shift is observed due to the non-uniform electrical activity of cardiomyocytes, possibly relocating the heart’s magnetic field [14]. (4) Furthermore, myocardial ischemia may result in an abnormal or uneven distribution of the cardiac magnetic field, manifesting as an anomalous intensity distribution on MCG, which is indicative of injury and necrosis [15]. These alterations in the magnetic field can be directly detected and analyzed using MCG instruments.

Compared to an electrocardiogram (ECG), an MCG detects magnetic rather than electrical signals generated by the heart’s currents [8, 16]. This method exhibits superior stability as magnetic fields are not attenuated by the body and have minimal effect on contact resistance and muscle motion artifacts [8, 16]. Previous studies have shown that MCG is highly sensitive in diagnosing myocardial ischemia [12, 17, 18], and its superior ability to detect CAD has been validated in several clinical studies [19, 20]. Unlike SPECT, MCG does not require patients to be injected with tracers, and the entire scan can be completed within 90 seconds [7]. Therefore, MCG is emerging as a safe, feasible, convenient, and effective diagnostic tool for identifying impaired myocardial perfusion and can be particularly useful in diagnosing patients with CCS.

Testing with MCG currently involves two main approaches: image analysis and parameter determination. The images analyzed include magnetic field maps, pseudo-current density maps, and MCG waveforms [21, 22, 23]. Normally, in healthy individuals, the synchronization of cardiomyocyte electrical activity results in an organized magnetic dipole orientation without dispersion or splitting during the repolarization phase, as seen in magnetic field maps [7]. In contrast, myocardial ischemia results in biological injury currents and repolarization abnormalities, manifesting as dipole angulation or disorganization in magnetic field maps [7]. However, interpreting these images is time-consuming and subjective, requiring professional analysis. To address these challenges, there is a critical need to develop a predictive model that provides automatic output parameters, enhancing both diagnostic accuracy and efficiency.

Machine learning algorithms, including random forest (RF), decision tree (DT), and support vector machine (SVM), have become essential tools in medical data processing, especially for binary categorical variables [15, 16, 17, 18]. These algorithms have demonstrated exceptional capabilities and diagnostic accuracy in recent studies [24, 25, 26, 27]. In this study, we leveraged RF, DT, and SVM to establish three machine learning classifiers. The aim is to utilize selected MCG variables to predict abnormal myocardial perfusion as recognized by SPECT.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

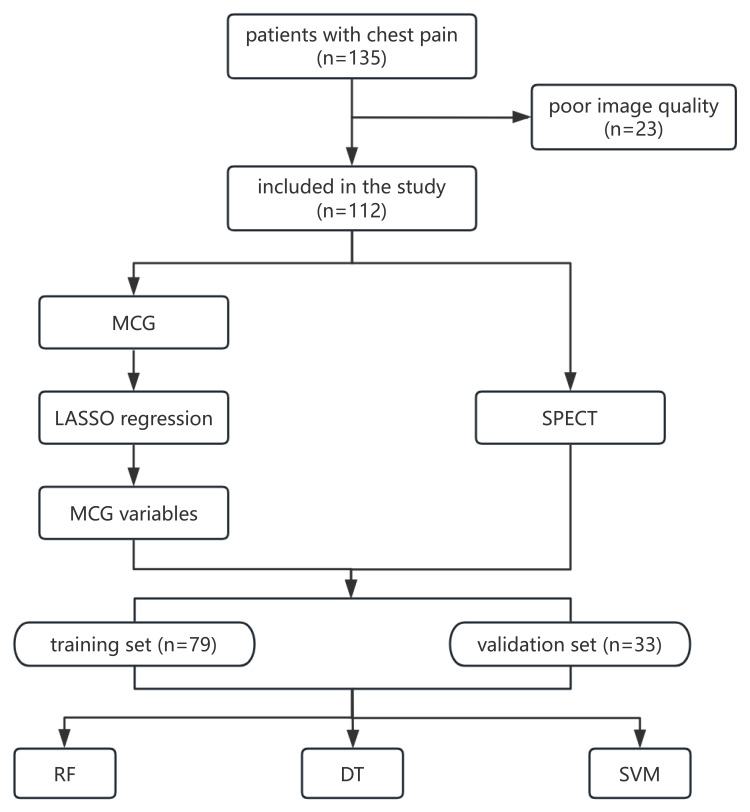

This study was conducted at the Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, and involved patients from the prospective cohort study ‘Application values of MCG in the CAD diagnosis’, which was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Beijing Anzhen Hospital affiliated to Capital Medical University (number: KS2022054). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Initially, 135 patients with chest pain in an outpatient setting were enrolled. The exclusion criteria included the presence of magnetic implants (e.g., pacemakers, implantable cardioverter defibrillators), claustrophobia, New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class III/IV heart failure, severe chest deformities, or any other condition making MCG scans inappropriate. Due to size limitations, patient movement, and metal interference, 23 patients were excluded after inadequate MCG scans and sensor captures, leaving 112 patients (91 males and 21 females) in the data analysis. All patients underwent SPECT testing at rest and/or during stress as well as MCG recordings within 3 months before any revascularization. In this cohort, 70 patients were diagnosed with reduced myocardial perfusion by SPECT. A flowchart of the study is presented in Fig. 1. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the institution’s human research committee.

Fig. 1.

Patient enrollment and analysis flowchart for evaluating myocardial perfusion using MCG and SPECT. Initially, 135 outpatients with chest pain were enrolled in this study and 112 patients were included in the data analysis finally. These patients underwent SPECT testing and MCG recordings within a 3-month period before any revascularization procedures. Post-screening, significant MCG variables were identified, and three machine learning models (RF, DT, and SVM) were developed to detect reduced myocardial perfusion. Abbreviations: MCG, magnetocardiography; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography; RF, random forest; DT, decision tree; SVM, support vector machine; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator.

2.2 Myocardial Perfusion Imaging Acquisition and Data Analysis

A conventional rest and exercise/drug stress two-day MPI imaging method was followed. Patients were instructed to discontinue theophyllines, nitrates, and -receptor antagonists 1 to 2 days before the examination. During the stress test, adenosine (90 mg/30 mL) was injected intravenously at a rate of 0.14 mgkg-1min-1, Technetium 99m sestamibi (99mTc-MIBI) was injected at the peak of adenosine administration, three minutes into the infusion, and MPI imaging was performed 1.5 h after injecting the imaging agent. The following day, resting MPI imaging was similarly performed 1.5 h after the intravenous injection of 99mTc-MIBI in the resting state. Imaging was performed using a Siemens SYMBIA INTEVO 16 SPECT/CT machine, equipped with a SMARTZOOM collimator and IQ-SPECT technology for SPECT data acquisition and a computerized image reconstruction system. The images were analyzed according to the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines, and the entire myocardium of the left ventricle was divided into 17 segments. A visual semi-quantitative 5-point scale was utilized for evaluation as follows: 0, normal radioactivity uptake; 1, mildly reduced radioactivity distribution; 2, moderately reduced radioactivity uptake; 3, severely reduced radioactivity uptake; and 4, radioactivity defects. Myocardial ischemia was defined as a segmental ‘reversible’ change in radioactivity distribution, whereas myocardial infarction was defined as a segmental ‘irreversible’ defect in radioactivity distribution in the myocardium.

2.3 MCG System and Recording

A 36-channel OPM-MCG system (Miracle MCG, Beijing X-MAGTECH Technologies Ltd., Beijing, China) was used for all MCG measurements. This system features a measurement sensitivity of 30 fT/Hz1/2 through the 36-channel atomic magnetometer. The direct-current residual magnetic field in the MCG measurement area was maintained below 5 nT. Notably, the system was operated in an examination room without the need for additional magnetic shielding. Prior to each measurement, all potential sources of magnetic field interference, including magnetic metal objects (e.g., metal dentures and glasses), electronic devices (e.g., mobile phones, watches, and electronic locators), and magnetic materials (e.g., magnets, bank cards, banknotes, and undergarments with magnetic components), were removed from the vicinity. Patients were placed supine on the examination bed, with the sensor array positioned approximately 2 cm above the chest. Controlled by the MCG system software, both the patient and the sensor array automatically entered the magnetic shielding space, initiating the automatic collection of cardiac magnetic field data. Each patient’s cardiac activity was continuously recorded across 36 points using an arrayed sensor in a 6 6 grid positioned above the chest, with a total recording time of 90 seconds.

2.4 MCG Data Analysis

After the MCG data collection was completed, the patient was automatically moved out of the magnetic shielding space, and the software automatically reconstructed high-precision magnetic field maps and pseudo-current density maps. These maps visually represented the spatiotemporal distribution of magnetic fields and provided outputs of the corresponding parameters. An independent investigator then conducted a quality evaluation and image analysis to exclude unqualified images. Sixty-five parameters associated with magnetic field, current angle, magnetic field amplitude, and magnetic pole change were collected from each patient.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R 4.3.0 software (R Core Team, 2023, Vienna, Austria). The baseline data were expressed as mean value standard deviation (SD), with comparisons between mean values performed with an independent sample Student’s t-test to assess statistical significance between the ischemic and non-ischemic groups, assuming data normality. For non-normally distributed variables, the chi-square test was used. Variable selection was performed using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression to identify key MCG parameters. The study population was divided into a training set and a validation set in a 7:3 ratio, and machine learning models—RF, DT, and SVM—were developed using MCG variables [27, 28, 29, 30]. The RF model uses the random forest function of the random forest package (version 4.7-1.1), the DT model used the rpart function in the rpart package (version 4.1.23), and the SVM function of the e1071 package (version 1.7-14) was used for the SVM model. Diagnostic measures including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy were calculated. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted to calculate the areas under the ROC curves (AUC). Statistical significance was set at p 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Patient Demographics

Of the initial 135 patients, 112 met the inclusion criteria for the study. These patients had an average age of 58.93 9.583 years (range: 35–77), with 91 (81.25%) being male. The median time between SPECT and MCG was 5.00 (2.00, 25.25) days. Impaired myocardial perfusion, indicative of myocardial ischemia or infarction, was observed in 70 patients. Notably, the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors was significantly higher in this group, especially concerning sex, dyslipidemia, previous MI, and previous PCI. Specifically, in the group with impaired myocardial perfusion, 45 patients (64.3%) were diagnosed with hypertension, 24 (34.3%) with diabetes, and 62 (88.6%) with dyslipidemia. Comparatively, in the control group, these figures were 21 (50.0 %), 11 (26.2 %), and 30 (71.4 %), respectively. Among the 112 patients, 27 (38.6%) patients in the experimental group and 9 (21.4%) patients in the control group had a history of smoking. Twenty-four (34.3%) patients in the experimental group were diagnosed with MI, and 21 (30%) underwent PCI (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comprehensive demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, and therapeutic interventions for patients with and without impaired myocardial perfusion.

| Impaired myocardial perfusion | Normal myocardial perfusion | p value | |

| Men, n (%) | 65 (92.9%) | 26 (61.9%) | 0.000 |

| Age, years | 58.90 9.97 | 58.98 9.01 | 0.968 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 45 (64.3%) | 21 (50.0%) | 0.137 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 24 (34.3%) | 11 (26.2%) | 0.371 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 62 (88.6%) | 30 (71.4%) | 0.022 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 27 (38.6%) | 9 (21.4%) | 0.060 |

| Previous MI, n (%) | 24 (34.3%) | 6 (14.3%) | 0.021 |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 21 (30%) | 4 (9.5%) | 0.012 |

Values are n (%) or mean SD. Abbreviations: MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SD, standard deviation.

3.2 LASSO Regression for MCG Variable Selection

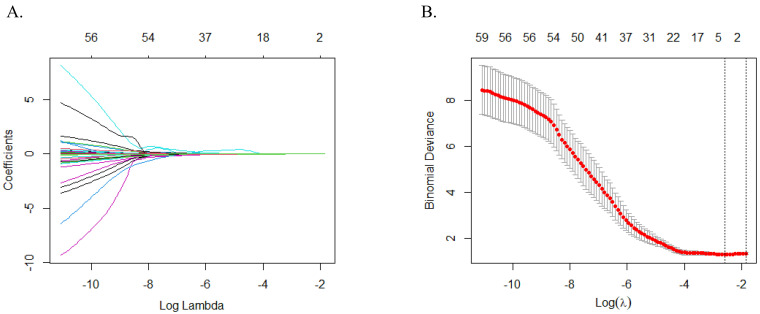

To optimize the selection of meaningful MCG variables, we utilized the LASSO selection method with 10-fold cross-validation. The variation in characteristics for these variables is depicted in Fig. 2A. We determined 0.061440 as the optimal regularization parameter, which was lambda.min (shown in Fig. 2B), chosen specifically to minimize prediction errors. This parameter was used to select five key variables—the ratio of magnetic field amplitude at R-peak and positive T-peak (RoART+), R and T-peak magnetic field angle (RTA), maximum magnetic field angle (MAmax), maximum change in current angle (CCAmax) and change positive pole point area between T-wave beginning and peak (CPPPATbp)—due to their strong association with myocardial perfusion (Table 2). These variables will serve as crucial inputs in the predictive model.

Fig. 2.

LASSO regression analysis for MCG variable selection. (A) The variation characteristics of the coefficient of variables. (B) The selection process of the optimum value of the parameter in the LASSO regression model by cross-validation method. Abbreviations: LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; MCG, magnetocardiography.

Table 2.

Key MCG parameters identified by LASSO regression for myocardial perfusion analysis.

| Parameter | Definition |

| RoART+ | The ratio of magnetic field amplitude at R-peak and the positive amplitude at T-peak |

| RTA | The magnetic field angle between R-peak and T-peak |

| MAmax | The maximum magnetic field angle at intervals of a certain time τ within TT segment |

| CCAmax | The maximum value of changes in current angle at intervals of a certain time τ within TT segment |

| CPPPATbp | The change in positive pole point area between T-begin and T-peak |

Abbreviations: RoART+, the ratio of magnetic field amplitude at R-peak and positive T-peak; RTA, R and T-peak magnetic field angle; MAmax, maximum magnetic field angle; CCAmax, maximum change in current angle; CPPPATbp, change positive pole point area between T-wave beginning and peak; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; MCG, magnetocardiography.

3.3 RF, DT and SVM Models for Prediction of Abnormal Myocardial Perfusion

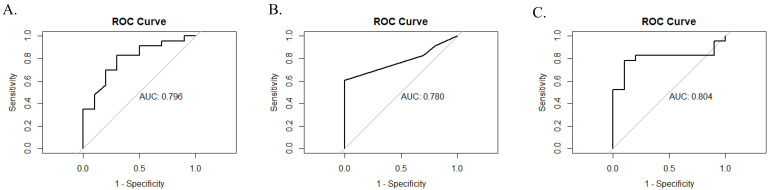

After confirming the five variables through LASSO regression, we developed three predictive models, RF, DT, and SVM, to assess if the MCG variables predict impaired myocardial perfusion. All included participants were randomly assigned to a training set (n = 79) or a validation set (n = 33) in a ratio of 7:3. Each model utilized the five screened MCG variables: RoART+, RTA, MAmax, CCAmax, and CPPPATbp. According to the ESC Guidelines, impaired myocardial perfusion was defined as exhibiting either a reversible or fixed deficit on SPECT [1, 31]. The diagnostic performances of the three models in the validation set are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 3. All three models demonstrated excellent diagnostic accuracy, with AUC values of 0.796, 0.780, and 0.804, respectively. Additionally, the models showed high sensitivity (RF = 0.870, DT = 0.826, and SVM = 0.913), whereas their specificity was comparatively lower (RF = 0.500, DT = 0.300, and SVM = 0.100). In terms of predictive performance, the RF model had a positive predictive value (PPV) of 0.800, a negative predictive value (NPV) of 0.625, and an overall accuracy of 0.758. The accuracies of the DT and SVM models were 0.667, PPVs of 0.730 and 0.700, and NPVs of 0.428 and 0.333, respectively.

Table 3.

Comparative diagnostic performance of RF, DT, and SVM models in the validation set.

| Models | Performance | |||||

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | AUC | |

| RF | 0.870 | 0.500 | 0.800 | 0.625 | 0.758 | 0.796 |

| DT | 0.826 | 0.300 | 0.730 | 0.428 | 0.667 | 0.780 |

| SVM | 0.913 | 0.100 | 0.700 | 0.333 | 0.667 | 0.804 |

This table compares the diagnostic performance of three machine learning models—RF, DT, and SVM—in the validation set. Performance metrics include Sensitivity, Specificity, PPV, NPV, Accuracy, and AUC. Abbreviations: RF, random forest; DT, decision tree; SVM, support vector machine; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

Fig. 3.

ROC curves and AUC values for RF, DT and SVM models. (A) RF. (B) DT. (C) SVM. These graphs highlight the diagnostic performances of the models with their respective AUC values of 0.796, 0.780, and 0.804. The models demonstrated high sensitivity (RF = 0.870, DT = 0.826, and SVM = 0.913) but varied in specificity (RF = 0.500, DT = 0.300, and SVM = 0.100). Abbreviations: ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; RF, random forest; DT, decision tree; SVM, support vector machine.

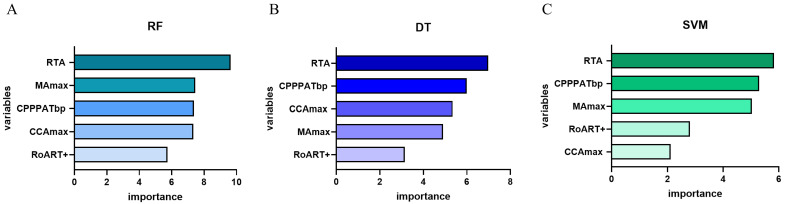

As shown in Fig. 4, the importance of each variable was determined using the calculated coefficients in each model. Among the five parameters evaluated, RTA emerged as the most critical variable in the RF, DT, and SVM models. In contrast, the importance of the remaining parameters varied between each model. Specifically, CPPPATbp was identified as the second most significant variable in the DT and SVM models, while MAmax was ranked second in the RF model.

Fig. 4.

The ranking of variables in all three models. (A) RF. (B) DT. (C) SVM. This figure illustrates the importance of five variables within three predictive models. RTA emerged as the most crucial variable across all models, significantly influencing the model outcomes. Abbreviations: RF, random forest; DT, decision tree; SVM, support vector machine; RTA, R and T-peak magnetic field angle; MAmax, maximum magnetic field angle; CPPPATbp, change positive pole point area between T-wave beginning and peak; CCAmax, maximum change in current angle; RoART+, the ratio of magnetic field amplitude at R-peak and positive T-peak.

Additionally, 41 patients with impaired SPECT myocardial perfusion underwent CAG within 3 months of SPECT and MCG testing. Of these, 28 patients underwent revascularization during the CAG procedure. Using a criterion of stenosis 50% for defining significant CAD, 35 patients were identified with positive CAG results, and 6 with negative results. Both the SPECT and MCG tests showed positive outcomes in these patients. Therefore, with CAG as the gold standard, the sensitivities of both SPECT and MCG were determined to be 1.00, indicating perfect agreement in detecting clinically relevant coronary obstructions.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the correlation between OPM-MCG and SPECT in an unshielded clinical environment. We analyzed 65 MCG parameters and selected five critical variables using LASSO regression. Subsequently, we employed three machine learning algorithms—RF, DT, and SVM—to develop predictive models. These models demonstrated exceptional diagnostic performance in detecting impaired myocardial perfusion, as identified by SPECT. We further evaluated the importance of each variable across all three models and found that RTA, which characterizes the magnetic field’s properties, was the most influential variable.

Unlike prior MCG research, this study was conducted in an unshielded clinical setting. The magnetic fields generated by myocardial cell activity are exceedingly weak, approximately 10-11 to 10-14 T, compared with Earth’s magnetic field of about 10-4 T [32]. Traditionally, MCG assessments required magnetically shielded rooms to mitigate environmental magnetic noise [33, 34, 35]. However, the OPM-MCG used in our study integrates built-in shielding within the device itself, providing robust anti-interference capabilities against environmental magnetic fields. This study successfully demonstrates that high-quality MCGs scans, including magnetic field maps and pseudo-current density maps, can be performed in unshielded environments using the advanced OPM-MCG, thus supporting the feasibility of broader clinical application without the need for specialized shielding infrastructure.

According to the 2019 ESC of Cardiology guidelines, functional stress imaging is highly recommended for patients with CCS who exhibit new symptoms after PTP evaluation to guide further treatment strategies [1]. However, the use of tracers and the associated waiting time for tracer distribution are both time-consuming and inconvenient. In contrast, MCG, which has been proven to be highly sensitive to ischemia, overcomes these drawbacks. It is likely to effectively identify impaired myocardial perfusion and can thus be applied in diagnosing patients with CCS. A previous study showed that MCG’s performance in detecting significant CAD, as diagnosed by CAG, was not inferior to that of stress SPECT [36]. In this study, we further explored the capacity of MCG to identify impaired myocardial perfusion, as confirmed using SPECT, highlighting its potential as an efficient and non-invasive diagnostic tool.

By analyzing the diagnostic indicators, we found that all three models exhibited high sensitivity but had relatively lower specificity. Several factors contribute to this low specificity in MCG. Primarily, patients with a history of diabetes who present with positive MCG results but negative SPECT results may exhibit coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD), which is prevalent in this demographic [37, 38, 39]. Although PET scans, which measure absolute quantitative myocardial blood flow (MBF) and coronary flow reserve (CFR), remain the gold standard for noninvasively assessing CMD, quantifying CFR in SPECT is challenging due to its lower sensitivity [40, 41, 42]. In our study, myocardial perfusion was evaluated using a visual semi-quantitative 5-point scale, which may not effectively recognize coronary microvascular lesions. However, MCG has the capability to detect subtle magnetic field changes caused by abnormal electrical activity of cardiomyocytes, potentially identifying coronary microvascular ischemia that is not detected by SPECT.

In our study, 26.2% of patients who exhibited normal myocardial perfusion on SPECT (11/42) had diabetes, suggesting that CMD should explain some of the low specificity observed with MCG. However, the diagnosis of CMD mainly relies on the measurement of the index of microvascular resistance (IMR) during CAG or CFR using PET—procedures that were not performed on our study participants. Consequently, further research is necessary to validate our hypothesis that the diagnostic capabilities of MCG for CMD can effectively assess microvascular dysfunction.

Additionally, SPECT reflects the relative blood flow in the myocardium. When lesions are uniformly present across all three coronary artery branches, balanced ischemia may occur, potentially leading to false-negative results in SPECT imaging. In situations where patients exhibit severe symptoms yet present with normal SPECT results, MCG can be an invaluable supplementary diagnostic tool to assess the need for further CAG. Because of these dynamics, MCG often yields a higher number of false positives and fewer true negatives, reflecting its lower specificity and enhanced sensitivity. Therefore, MCG has proven to be an effective screening method for myocardial ischemia, adept at identifying patients at high risk for impaired myocardial perfusion. For patients with positive MCG results, additional diagnostic evaluations are recommended to mitigate the risk of overlooked ischemia.

In our study, the RTA, which measures the magnetic field angle between the R-peak and T-peak, emerged as the most critical parameter across all three models. This finding aligns with several studies that have identified the magnetic field angle as a fundamental parameter for the diagnosis of myocardial ischemia. For instance, Ramesh et al. [21] investigated 29 patients with chest pain and normal resting ECG s, reporting that an abnormal magnetic field angle was significantly more prevalent among patients with positive treadmill test results (72% vs. 6%). Similarly, Lim et al. [43] evaluated 24 MCG parameters and identified the field-map angle as one of the most sensitive for detecting patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). Our results corroborate these earlier findings, underscoring the importance of changes in the magnetic field angle—caused by cardiomyocyte injury—in the detection of myocardial ischemia.

This study had several limitations. First, as a single-center study, the robustness and generalizability of our findings, including the MCG parameters and machine learning models, cannot be conclusively determined. Subsequent multicenter studies are required to apply these parameters and models to validate their performance across broader populations. Second, the sample size was relatively small, reflecting the limited routine use of SPECT in clinical practice. Again, larger studies are needed to construct more stable and reliable models to aid in the diagnosis of myocardial ischemia. Finally, patients were categorized based solely on the presence or absence of reduced myocardial perfusion detected by SPECT, without considering the specific degrees and locations of decreased perfusion. In future studies, we intend to increase the number of enrolled patients and construct models to predict the degree and location of impaired myocardial perfusion.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that machine learning models—specifically RF, DT, and SVM—possess excellent data processing capabilities, making them highly effective for detecting impaired myocardial perfusion. Notably, the R and T-peak magnetic field angle (RTA) emerged as the most critical variable in all the three models. Consequently, MCG shows great potential as an effective screening tool for identifying patients at high risk of impaired myocardial perfusion. Looking forward, MCG could significantly enhance diagnostic strategies for myocardial ischemia.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Zhechun Zeng, Ming Ding, and Bin Cai for their help in statistics and data analysis.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Beijing Hospitals Authority ‘sailing' Program (grant number YGLX202323), Beijing Nova Program (grant number 20220484222), Coordinated innovation of scientific and technological in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region (grant number Z231100003923008), Beijing Hospitals Authority's Ascent Plan (grant number DFL20220603), Project of The Beijing Lab for Cardiovascular Precision Medicine (grant number PXM2018_014226_000013) and High-level public health technical talent construction project of Beijing Municipal Health Commission (Leading Talent-02-01).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chenchen Tu, Email: tcc2033@163.com.

Xiantao Song, Email: song0929@mail.ccmu.edu.cn.

Author Contributions

HZ, ZM designed the research study and performed statistical analysis. SY, LL, SZ, LF, XZ, XY provided help in collecting and organizing data. HM, JJ, WD provided help and advice on the data analysis of myocardial perfusion imaging. HZ wrote the manuscript. XS, CT, HJZ proposed the research conception, supervised the program and revised the manuscript. XS, CT took management and coordination responsibility for the research activity planning and execution. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Patients in this study were obtained from a prospective cohort study ‘Application values of magnetocardiography in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease’, which was approved by Medical Ethics Committee of Beijing Anzhen Hospital affiliated to Capital Medical University (number: KS2022054). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Funding

This study was supported by Beijing Hospitals Authority ‘sailing’ Program (grant number YGLX202323), Beijing Nova Program (grant number 20220484222), Coordinated innovation of scientific and technological in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region (grant number Z231100003923008), Beijing Hospitals Authority’s Ascent Plan (grant number DFL20220603), Project of The Beijing Lab for Cardiovascular Precision Medicine (grant number PXM2018_014226_000013) and High-level public health technical talent construction project of Beijing Municipal Health Commission (Leading Talent-02-01).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, Capodanno D, Barbato E, Funck-Brentano C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. European Heart Journal . 2020;41:407–477. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Knuuti J, Ballo H, Juarez-Orozco LE, Saraste A, Kolh P, Rutjes AWS, et al. The performance of non-invasive tests to rule-in and rule-out significant coronary artery stenosis in patients with stable angina: a meta-analysis focused on post-test disease probability. European Heart Journal . 2018;39:3322–3330. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tonino PAL, Fearon WF, De Bruyne B, Oldroyd KG, Leesar MA, Ver Lee PN, et al. Angiographic versus functional severity of coronary artery stenoses in the FAME study fractional flow reserve versus angiography in multivessel evaluation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology . 2010;55:2816–2821. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Iskander S, Iskandrian AE. Risk assessment using single-photon emission computed tomographic technetium-99m sestamibi imaging. Journal of the American College of Cardiology . 1998;32:57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, Cohen I, Berman DS. Comparison of the short-term survival benefit associated with revascularization compared with medical therapy in patients with no prior coronary artery disease undergoing stress myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography. Circulation . 2003;107:2900–2907. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072790.23090.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hung GU, Ko KY, Lin CL, Yen RF, Kao CH. Impact of initial myocardial perfusion imaging versus invasive coronary angiography on outcomes in coronary artery disease: a nationwide cohort study. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging . 2018;45:567–574. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3872-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pena ME, Pearson CL, Goulet MP, Kazan VM, DeRita AL, Szpunar SM, et al. A 90-second magnetocardiogram using a novel analysis system to assess for coronary artery stenosis in Emergency department observation unit chest pain patients. International Journal of Cardiology. Heart & Vasculature . 2020;26:100466. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2019.100466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Camm AJ, Henderson R, Brisinda D, Body R, Charles RG, Varcoe B, et al. Clinical utility of magnetocardiography in cardiology for the detection of myocardial ischemia. Journal of Electrocardiology . 2019;57:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2019.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lim HK, Kwon H, Chung N, Ko YG, Kim JM, Kim IS, et al. Usefulness of magnetocardiogram to detect unstable angina pectoris and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. The American Journal of Cardiology . 2009;103:448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Van Leeuwen P, Hailer B, Beck A, Eiling G, Grönemeyer D. Changes in dipolar structure of cardiac magnetic field maps after ST elevation myocardial infarction. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology . 2011;16:379–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2011.00466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Xu F, Tu CC, Yang SW, Ding M, Cai B, Zhang H, et al. Clinical value of helium-free magnetocardiography in diagnosis of coronary heart disease. Chinese Journal of General Practice . 2023;22:1159–1166. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nomura M, Nakaya Y, Fujino K, Ishihara S, Katayama M, Takeuchi A, et al. Magnetocardiographic studies of ventricular repolarization in old inferior myocardial infarction. European Heart Journal . 1989;10:8–15. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lant J, Stroink G, ten Voorde B, Horacek BM, Montague TJ. Complementary Nature of Electrocardiographic and Magnetocardiographic Data in Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease. Journal of Electrocardiology . 1990;23:315–322. doi: 10.1016/0022-0736(90)90121-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Steinberg BA, Roguin A, Watkins SP 3rd, Hill P, Fernando D, Resar JR. Magnetocardiogram Recordings in a Nonshielded Environment-Reproducibility and Ischemia Detection. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology . 2005;10:152–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2005.05611.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bang WD, Kim K, Lee YH, Kwon H, Park Y, Pak HN, et al. Repolarization Heterogeneity of Magnetocardiography Predicts Long-Term Prognosis in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Yonsei Medical Journal . 2016;57:1339–1346. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.6.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chen J, Thomson PD, Nolan V, Clarke J. Age and sex dependent variations in the normal magnetocardiogram compared with changes associated with ischemia. Annals of Biomedical Engineering . 2004;32:1088–1099. doi: 10.1114/b:abme.0000036645.35013.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kanzaki H, Nakatani S, Kandori A, Tsukada K, Miyatake K. A new screening method to diagnose coronary artery disease using multichannel magnetocardiogram and simple exercise. Basic Research in Cardiology . 2003;98:124–132. doi: 10.1007/s00395-003-0392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rong Tao, Shulin Zhang, Xiao Huang, Minfang Tao, Jian Ma, Shixin Ma, et al. Magnetocardiography-Based Ischemic Heart Disease Detection and Localization Using Machine Learning Methods. IEEE Transactions on Bio-Medical Engineering . 2019;66:1658–1667. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2018.2877649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Park JW, Hill PM, Chung N, Hugenholtz PG, Jung F. Magnetocardiography predicts coronary artery disease in patients with acute chest pain. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology . 2005;10:312–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2005.00634.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].On K, Watanabe S, Yamada S, Takeyasu N, Nakagawa Y, Nishina H, et al. Integral value of JT interval in magnetocardiography is sensitive to coronary stenosis and improves soon after coronary revascularization. Circulation Journal . 2007;71:1586–1592. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ramesh R, Senthilnathan S, Satheesh S, Swain PP, Patel R, Ananthakrishna Pillai A, et al. Magnetocardiography for identification of coronary ischemia in patients with chest pain and normal resting 12-lead electrocardiogram. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology, Inc . 2020;25:e12715. doi: 10.1111/anec.12715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Udovychenko Y, Popov A, Chaikovsky I. Multistage Classification of Current Density Distribution Maps of Various Heart States Based on Correlation Analysis and k-NN Algorithm. Front Med Technol . 2021;3:779800. doi: 10.3389/fmedt.2021.779800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Tu CC, Ding M, Cai B, Zhou S, Yang SW, Liu LQ, et al. The Operating Procedure and Image Quality Factors of the New Helium-Free magnetocardiography. Journal of Cardiovascular & Pulmonary Diseases . 2023;42:758–761. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yu Y, He Z, Ouyang J, Tan Y, Chen Y, Gu Y, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging radiomics predicts preoperative axillary lymph node metastasis to support surgical decisions and is associated with tumor microenvironment in invasive breast cancer: A machine learning, multicenter study. eBioMedicine . 2021;69:103460. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Yang L, Wu H, Jin X, Zheng P, Hu S, Xu X, et al. Study of cardiovascular disease prediction model based on random forest in eastern China. Scientific Reports . 2020;10:5245. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62133-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sánchez-Reolid R, Martínez-Rodrigo A, López MT, Fernández-Caballero A. Deep Support Vector Machines for the Identification of Stress Condition from Electrodermal Activity. International Journal of Neural Systems . 2020;30:2050031. doi: 10.1142/S0129065720500318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Feng C, Di J, Jiang S, Li X, Hua F. Machine learning models for prediction of invasion Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess syndrome in diabetes mellitus: a singled centered retrospective study. BMC Infectious Diseases . 2023;23:284. doi: 10.1186/s12879-023-08235-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pang W, Zhang B, Jin L, Yao Y, Han Q, Zheng X. Serological Biomarker-Based Machine Learning Models for Predicting the Relapse of Ulcerative Colitis. Journal of Inflammation Research . 2023;16:3531–3545. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S423086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ambale-Venkatesh B, Yang X, Wu CO, Liu K, Hundley WG, McClelland R, et al. Cardiovascular Event Prediction by Machine Learning: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circulation Research . 2017;121:1092–1101. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Seethaler B, Nguyen NK, Basrai M, Kiechle M, Walter J, Delzenne NM, et al. Short-chain fatty acids are key mediators of the favorable effects of the Mediterranean diet on intestinal barrier integrity: data from the randomized controlled LIBRE trial. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition . 2022;116:928–942. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqac175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tilkemeier PL, Bourque J, Doukky R, Sanghani R, Weinberg RL. ASNC imaging guidelines for nuclear cardiology procedures: Standardized reporting of nuclear cardiology procedures. Journal of Nuclear Cardiology . 2017;24:2064–2128. doi: 10.1007/s12350-017-1057-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hart G. Biomagnetometry: imaging the heart’s magnetic field. British Heart Journal . 1991;65:61–62. doi: 10.1136/hrt.65.2.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kwon H, Kim K, Lee YH, Kim JM, Yu KK, Chung N, et al. Non-invasive magnetocardiography for the early diagnosis of coronary artery disease in patients presenting with acute chest pain. Circulation Journal . 2010;74:1424–1430. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hänninen H, Takala P, Korhonen P, Oikarinen L, Mäkijärvi M, Nenonen J, et al. Features of ST segment and T-wave in exercise-induced myocardial ischemia evaluated with multichannel magnetocardiography. Annals of Medicine . 2002;34:120–129. doi: 10.1080/07853890252953518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Takala P, Hänninen H, Montonen J, Korhonen P, Mäkijärvi M, Nenonen J, et al. Heart rate adjustment of magnetic field map rotation in detection of myocardial ischemia in exercise magnetocardiography. Basic Research in Cardiology . 2002;97:88–96. doi: 10.1007/s395-002-8391-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wu YW, Lin LC, Tseng WK, Liu YB, Kao HL, Lin MS, et al. QTc Heterogeneity in Rest Magnetocardiography is Sensitive to Detect Coronary Artery Disease: In Comparison with Stress Myocardial Perfusion Imaging. Acta Cardiologica Sinica . 2014;30:445–454. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Di Carli MF, Janisse J, Grunberger G, Ager J. Role of chronic hyperglycemia in the pathogenesis of coronary microvascular dysfunction in diabetes. Journal of the American College of Cardiology . 2003;41:1387–1393. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Nitenberg A, Valensi P, Sachs R, Cosson E, Attali JR, Antony I. Prognostic value of epicardial coronary artery constriction to the cold pressor test in type 2 diabetic patients with angiographically normal coronary arteries and no other major coronary risk factors. Diabetes Care . 2004;27:208–215. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].von Scholten BJ, Hasbak P, Christensen TE, Ghotbi AA, Kjaer A, Rossing P, et al. Cardiac (82)Rb PET/CT for fast and non-invasive assessment of microvascular function and structure in asymptomatic patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia . 2016;59:371–378. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3799-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Schindler TH, Fearon WF, Pelletier-Galarneau M, Ambrosio G, Sechtem U, Ruddy TD, et al. Myocardial Perfusion PET for the Detection and Reporting of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction: A JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging Expert Panel Statement. JACC. Cardiovascular Imaging . 2023;16:536–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2022.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Crea F, Camici PG, Bairey Merz CN. Coronary microvascular dysfunction: an update. European Heart Journal . 2014;35:1101–1111. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Del Buono MG, Montone RA, Camilli M, Carbone S, Narula J, Lavie CJ, et al. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction Across the Spectrum of Cardiovascular Diseases: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology . 2021;78:1352–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lim HK, Chung N, Kim K, Ko YG, Kwon H, Lee YH, et al. Can magnetocardiography detect patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction? Annals of Medicine . 2007;39:617–627. doi: 10.1080/07853890701538040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.