Abstract

A wide range of theoretical methods, including high level ab initio, density functional, self-consistent reaction field, molecular dynamics and thermodynamic integration calculations, have been used to analyze the mutagenic properties of oxanosine. The major tautomeric forms in the gas phase and aqueous solution have been determined. The ability of oxanosine to recognize thymine and cytosine in the gas phase and in the DNA environment has been compared with that of guanine. A physicochemical explanation for the mutagenic properties of oxanosine is suggested.

INTRODUCTION

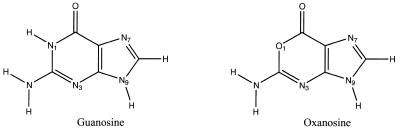

Oxanosine (5-amino-3-β-d-ribofuranosyl-3H-imidazo[4,5-d]oxazin-7-one; see Fig. 1) was originally isolated from Streptomyces capreolus MG265-CF3 (1) and has antibiotic properties in both its ribo and 2′-deoxyribo forms (1–4). In addition to its antibacterial activity, oxanosine exhibits other important biological effects. Thus, it was demonstrated in the early 1980s (3) that oxanosine inhibits the growth of leukemia L12100 cell lines, as well as nucleic acid synthesis and in vitro cell growth (4–6) of tumoral cells obtained by infection with a mutant Rous sarcoma virus. Interestingly, the cytotoxic properties of oxanosine are stronger in tumoral cells than in healthy cells (5,6), which suggests potential therapeutic applications as an antineoplasic agent. This possibility was reinforced by the discovery that oxanosine induced reversion of K-ras-transformed rat kidney cells to the normal phenotype (7). The mechanisms of the antitumoral activity of oxanosine are still unclear, but they have been attributed to either inhibition of GMP synthase or to its genotoxic properties (see below and 1–7).

Figure 1.

Structure of oxanosine (5-amino-3-β-d-ribofuranosyl-3H-imidazo[4,5-d]oxazin-7-one) and guanosine.

Very recently 2′-deoxyoxanosine has also been associated with nitric oxide (NO)-induced genotoxicity. Both nitrous acid and NO are genotoxic since they deaminate nucleosides, nucleotides and nucleic acids (8). It has recently been shown that 2′-deoxyoxanosine is one of the main products of NO-induced deamination of 2′-deoxyguanosine (9), suggesting a key role in NO-induced genotoxicity (9,10). This hypothesis was reinforced by the finding that 2′-deoxyxanthosine, another product of NO-induced deamination of 2′-deoxyguanosine, is easily eliminated by spontaneous hydrolysis due to its weak N-glycosidic bond (10), while 2′-deoxyoxanosine is as stable as 2′-deoxyguanosine (10). These results suggest that 2′-deoxyoxanosine might be inserted into DNA for long enough to induce genotoxic effects (10).

The replacement of 2′-deoxyguanosine by 2′-deoxyoxanosine destabilizes the duplex (10), but circular dichroism experiments (10) have shown that the presence of a few 2′-deoxyoxanosine molecules in a DNA does not affect the duplex structure. Moreover, a remarkable feature of 2′-deoxyoxanosine is its ambiguity in pyrimidine pairing (10,11). Thus, while d(G·T) mismatching decreases the melting temperature of the duplex by 12°C, d(O·T) mismatching reduces the melting temperature of the duplex by only 3°C [with respect to the d(O·C) pair]. These findings have been confirmed by the demonstration that 2′-deoxyoxanosine can be incorporated into DNA (11) paired to C with an efficiency only slightly better than when paired to T.

Although a large body of evidence supports the potential applications of 2′-deoxyoxanosine, its genotoxic mechanism is not understood. It is known from crystal data (2) that oxanosine (and its 2′-deoxy form) exists mainly in the anti conformation, with sugar puckerings in the South and North regions. The neutral keto-amino (lactone) tautomer is the main species in the crystal (2) and probably in solution at physiological pH (10,11). However, the physiologically relevant tautomer of 2′-deoxyoxanosine has not been identified and the structural and energetic details of the interaction of this ‘active form’ of 2′-deoxyoxanosine with DNA remain to be determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

QM calculations

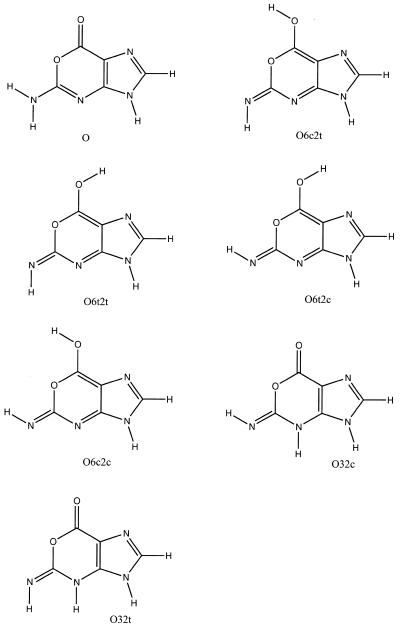

The tautomerism of oxanosine in the gas phase was examined using high level ab initio and DFT quantum mechanical computations. The solvent effect on tautomerism was introduced from self-consistent reaction field calculations. The geometry of selected tautomers (see Fig. 2) was fully optimized at the HF/6-31G(d) (12) and Becke3-Lee-Yang-Parr (B3LYP) levels (13). The minimum nature of the optimized structures was verified from vibrational frequency analysis. Single point calculations were carried out at the HF and MP2 levels on the 6-311++G(d,p) basis (14) using the HF/6-31G(d) optimized geometry and on the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) basis using geometrical parameters optimized at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level. Considering the convergence in the tautomerization energy further extension of the level of theory was not considered. Thermal and entropic corrections were determined within the harmonic oscillator–rigid rotor framework using the HF/6-31G(d) and B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) optimized geometries and the standard procedures in Gaussian 94 (15). The HF/6-31G(d) frequencies were scaled by 0.893. These corrections were added to the energy differences to derive the thermodynamic parameters for tautomerism equilibria.

Figure 2.

Tautomers of oxanosine considered in this study.

The free energy of tautomerism in aqueous solution was determined from equation 1, where the differences in free energy (ΔGaqA→B) between tautomers were computed by adding the relative free energies of hydration (ΔΔGhydA→B) to the gas phase free energy differences (ΔGgasA→B). The relative free energies of hydration were determined from the absolute values computed using our HF/6-31G(d) optimized version (16–18) of the MST method (also called the Polarizable Continuum Model; 19–21).

ΔGaqA→B = ΔGgasA→B + ΔGhydB – ΔGhydA = ΔGgasA→B + ΔΔGhydA→B 1

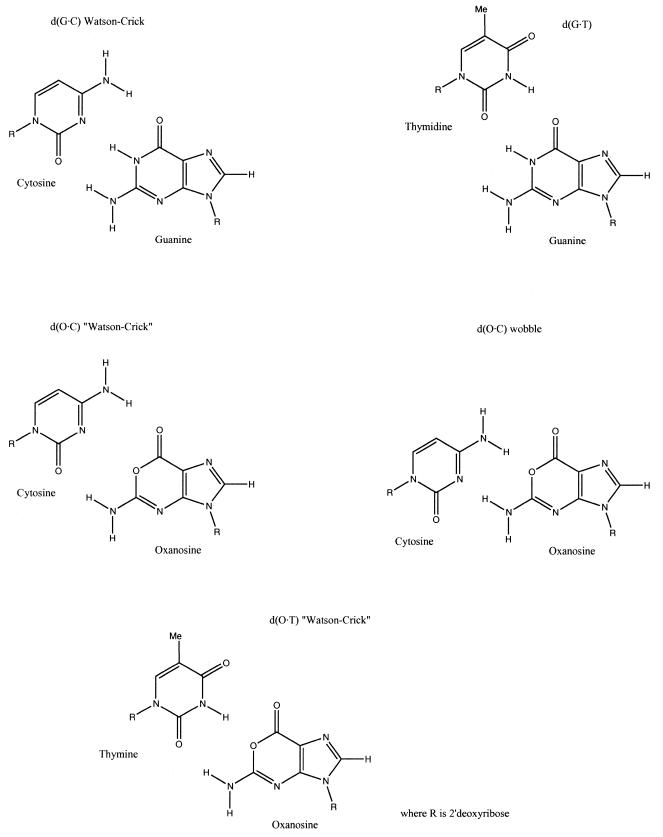

Once the major tautomeric form of oxanosine was identified, QM calculations were performed to determine the stability of selected dimers of guanine/oxanosine (only Watson–Crick-type geometries were considered) and cytosine/thymine (see Fig. 3). The geometries of the dimers were fully optimized at the HF/6-31G(d) and B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) levels and single point calculations were performed using different basis sets [from 6-31G(d) to aug-cc-pVDZ; 22]. The HF, MP2 and B3LYP levels of theory were considered. In all cases the basis set superposition error was corrected using the counterpoise method (23). Thermal, expansion and entropic corrections to the interaction energy were computed as noted above at the HF/6-31G(d) and B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) levels to obtain the dimerization free energy for a reference state of the ideal gas phase at 298 K and 1 atm.

Figure 3.

Hydrogen bonded dimers for the different pairs considered in the study. Only patterns of interactions resembling the original Watson–Crick scheme were considered.

Molecular dynamics (MD) calculations

MD calculations were performed to examine the structure, flexibility and interaction characteristics of DNA duplexes containing d(G·C), d(G·T), d(O·C) and d(O·T) pairs. For this purpose DNA duplexes d(CCAAXCTTGG)·d(CCAAGYTTGG) (where X is O or G and Y is C) were generated from the crystal structure (24) and manipulated (when necessary) to change the nucleotides at position 5 (for simplicity these duplexes are denoted in the following by only one of the strands).

Each structure was immersed in a box of 2550 TIP3P (25) water molecules with sodium ions added to maintain neutrality. Structures were optimized, heated and equilibrated using our standard 130 ps equilibration protocol (26–29). Equilibrated structures were then subjected to 1.5 ns of unrestrained MD simulation at constant pressure (1 atm) and temperature (298 K). The structures obtained after 0.5 ns of unrestrained MD simulations were used to generate starting models for the duplexes d(CCAAXCTTGG)·d(CCAAGYTTGG), with Y = T and X = O or G. These new structures were optimized, heated and equilibrated as noted above. Finally, they were subjected to 1.5 ns unrestrained MD simulations at constant pressure (1 atm) and temperature (298 K).

Periodic boundary conditions (PBC) and the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) (30,31) technique were used to account for long-range effects. Bond distances were fixed at their equilibrium values using SHAKE (32), which allowed us to use a time step of 2 fs for the integration of Newton equations of motion. AMBER-99 (33) and TIP3P (25) force field parameters were used to describe the DNA and water. Atomic charges for oxanosine were determined using the standard RESP procedure (34), from HF/6-31G(d) molecular electrostatic potentials, and van der Waal’s parameters were taken from corresponding atom types in the AMBER-99 force field.

Models of single-stranded DNA were generated using 5mer oligonucleotides of sequence d(AAXCT) (where X = G or O) and d(AGYTT) (Y = C or T), since our previous experience suggests that they are reliable models of single-stranded oligonucleotides. Starting models were built up from the corresponding duplex geometries and then optimized, heated and equilibrated as already noted. Finally, 1.5 ns unrestrained MD simulations were conducted at 1 atm and 298 K for the four single-stranded oligonucleotides.

Molecular solvation maps of the four duplexes (22) were determined by computing the density of water around the DNA using the structures collected during the last 0.5 ns of trajectory. Molecular Interaction Potential (MIP) (22) for the interaction of DNAs with an O+ probe molecule were calculated using the MD average structures obtained using the last 0.5 ns of each trajectory.

Thermodynamic integration

MD thermodynamic integration (MD-TI) calculations were used to determine the changes in stabilization free energies between d(G·C), d(G·T), d(O·C) and d(O·T) pairs using the standard procedure in equation 2. Accordingly, mutations between bases were performed both in duplexes and in single-stranded DNA. Starting structures for MD-TI simulations were those obtained at the end of the different trajectories. Calculations were carried out using 21 or 41 windows each consisting of 10 ps of equilibration and 10 ps of averaging, leading to a total of 420 or 820 ps of MD simulation for each mutation in the duplex and single-stranded DNAs. MD-TI simulations were performed using AMBER-95 (35) and AMBER-99 (33) force fields to determine the impact of the force field in the free energy estimates (starting structures for MD-TI/AMBER-95 calculations were obtained after 1 ns of MD/AMBER-95 trajectory). Mutations were made in the G→O and C→T-direction and the thermodynamic cycle d(G·C)→d(O·C)→d(O·T)→d(G·T)→d(G·C) was closed to verify convergence of the results. In all cases estimates of free energy changes obtained using the first and second halves of each window were determined to provide an additional measure of the errors related to limited sampling in simulations. All inter-group and non-bonded intra-group contributions to the free energy change during the mutations were considered in MD-TI calculations. The PBC and PME techniques, as well as all the same technical details for MD simulations, were also used in MD-TI calculations.

Computational details

Gas phase calculations were carried out using Gaussian 94 (15). MST calculations were performed using a locally modified version of MonsterGauss (36). Molecular dynamics and thermodynamic integration calculations were carried out using AMBER-5 (37). Helical analysis of duplex structures was performed with Curves 4.1 (38). All calculations were performed at the Centre de Supercomputació de Catalunya (CESCA) and on workstations in our laboratory.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Tautomerism of oxanosine

The nucleobases are highly versatile in the formation of hydrogen bonded complexes owing to the presence of numerous hydrogen bond donor and acceptor groups. Indeed, the distribution of such groups along the DNA grooves codifies sequence-specific recognition of the bases, which is crucial in processes like replication, transcription and binding to other molecules. Since the network of hydrogen bond interactions that modulates recognition relies on the assumption of specific tautomers, it is necessary to examine the tautomerism of oxanosine in order to analyze its recognition by nucleic acid bases.

Table 1 gives the differences in energy, enthalpy and free energy of the tautomers of oxanosine determined at the HF, MP2 and B3LYP levels on the 6-311++G(d,p) basis. There is close agreement in the results irrespective of the level of computation considered, which gives confidence in their quality. It is clear that the lactone species (O in Fig. 2) is by far the preferred form in the gas phase. In fact, considering the large difference in stability with the other forms, the lactone is expected to be the only detectable species in the gas phase.

Table 1. Differences (kcal/mol) in energy, enthalpy and free energy for tautomers of oxanosine in the gas phasea.

| Molecule | Methodb | ΔE | ΔH | ΔGgas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O6c2t | HF | 31.2 | 31.0 | 31.4 |

| MP2 | 32.9 | 32.7 | 33.1 | |

| B3LYP | 30.2 | 29.9 | 30.0 | |

| O6c2c | HF | 34.3 | 33.9 | 34.2 |

| MP2 | 35.1 | 34.7 | 35.0 | |

| B3LYP | 31.5 | 30.7 | 30.7 | |

| O6t2t | HF | 31.4 | 31.3 | 31.7 |

| MP2 | 32.6 | 32.5 | 32.9 | |

| B3LYP | 30.2 | 29.7 | 29.8 | |

| O6t2c | HF | 33.1 | 32.9 | 33.3 |

| MP2 | 33.6 | 33.4 | 33.8 | |

| B3LYP | 30.4 | 29.8 | 29.8 | |

| O32t | HF | 23.6 | 23.4 | 22.7 |

| MP2 | 23.5 | 23.3 | 22.6 | |

| B3LYP | 22.8 | 22.3 | 21.6 | |

| O32c | HF | 16.4 | 16.3 | 15.9 |

| MP2 | 16.7 | 16.6 | 16.2 | |

| B3LYP | 15.7 | 15.5 | 15.1 |

aThe values are relative to the lactone form. The energy (au) of this latter species at the different computational levels is –559.361684 (HF), –561.097480 (MP2) and –562.574695 (B3LYP). See Figure 2 for nomenclature of tautomers.

bAll the values were determined on the 6-311++G(d,p) basis. HF and MP2 calculations were performed using the geometries optimized at the HF/6-31G(d) level, whereas the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) optimized geometry was utilized in B3LYP calculations.

The effect of hydration on tautomerism was examined by means of ab initio HF/6-31G(d) MST calculations (see above). The differences in free energy of hydration between tautomers are given in Table 2. The results indicate that the enol-imino tautomers are in general better hydrated than the lactone species. This difference, nevertheless, is small and does not affect the intrinsic gas phase stability, the lactone form being the preferred species in aqueous solution by at least 12 kcal/mol compared to the keto-imino tautomers. Therefore, it seems clear that the lactone form of oxanosine is the only biologically important species in any condensed phase, in agreement with previous assumptions based mainly on crystal data (2).

Table 2. MST free energies of hydration (ΔΔGhyd, kcal/mol) and free energy differences in aqueous solution (ΔGsol, kcal/mol) for tautomers of oxanosinea.

| Molecule | ΔΔGhydb | ΔGsol(MP2)c | ΔGsol(B3LYP)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| O6c2t | –0.3 | 32.8 | 29.7 |

| O6c2c | –2.1 | 32.9 | 28.6 |

| O6t2t | 0.2 | 33.1 | 30.0 |

| O6t2c | –1.2 | 32.6 | 28.6 |

| O32t | –8.9 | 13.7 | 12.7 |

| O32c | –3.5 | 12.7 | 11.6 |

aThe values are relative to the lactone form. The free energy of hydration (kcal/mol) of this latter species is –16.2 kcal/mol. See Figure 2 for nomenclature of tautomers.

bNo significant differences (<0.1 kcal/mol) were found in the free energies of hydration when the geometries optimized at the HF/6-31G(d) or B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) levels were considered.

cThe values were determined by adding the relative free energies of hydration to the gas phase free energy differences computed at the MP2 and B3LYP levels reported in Table 1 (see equation 1).

Base pairing in the gas phase

Hydrogen bond dimerization was determined using a wide range of QM and classical methods. Geometries for the dimers used in the calculations [optimized at the HF/6-31G(d) and B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) levels] are compared in Table 3. In general, there are no relevant differences between the HF/6-31G(d) and B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) geometries, even though hydrogen bond distances in the B3LYP calculations were typically 0.1–0.2 Å shorter than the HF values (Table 3). The only important geometrical difference occurs for the O·C pair, where the cytosine is displaced to the N7 side of oxanosine in the B3LYP optimized geometry compared to the HF. This leads to a notable shortening of the N2H→O2 and O6←N4H hydrogen bonds and a concomitant increase in the N2H→N3 and O1←N4H distances when moving from the HF/6-31G(d) to the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) geometry. These results, together with HF interaction energies for distorted O·C dimers (data not shown), suggest that the potential energy surface of the O·C dimer is rather flat, which might lead to the co-existence of different binding modes (see below).

Table 3. Selected hydrogen bond distances in the geometries of the four dimers optimized at the HF/6-31G(d) and B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) levels.

| Dimer | Distancea | HF/6-31G(d) | B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| G·C | N2H→O2 | 2.01 | 1.90 |

| N1H→N3 | 2.03 | 1.90 | |

| O6←N4H | 1.92 | 1.75 | |

| G·T | N2H→O2 | 2.89 | 2.76 |

| N1H→O2 | 1.90 | 1.78 | |

| O6←N3H | 1.99 | 1.81 | |

| O·C | N2H→O2 | 2.28 | 1.91 |

| N2H→N3 | 2.32 | 2.64 | |

| O6←N4H | 2.17 | 1.95 | |

| O1←N4H | 2.62 | 2.86 | |

| O·T | N2H→O2 | 2.01 | 1.89 |

| O6←N3H | 2.35 | 2.24 | |

| O1←N3H | 2.67 | 2.47 |

aDistances in Å. Purine (pseudopurine) and pyrimidine atoms are indicated on the left and right sides of the arrow, respectively. The arrows show the donor→acceptor of the hydrogen bond. The purine/pyrimidine nomenclature is used for numbering (see Fig. 1).

The interaction energies obtained at different levels of theory (see selected values in Table 4) are reasonably close for a given base pair. It is worth noting the performance of the AMBER force field, which reproduces our best theoretical results (MP2/aug-cc-pVDZ) with an average root mean square deviation (RMSD) of only 1.1 kcal/mol. The G·C pairing is the most stable (stabilization energy around –28 kcal/mol at the highest level of theory, MP2/aug-cc-pVDZ), followed by the O·C and G·T pairs (around –16 kcal/mol), with the O·T dimer being the least stable pair (around –11 kcal/mol). Thermodynamic analysis (Table 5) shows that entropic and thermal effects are very important for the determination of absolute dimerization free energies, but do not alter the general qualitative trends derived from interaction energies.

Table 4. Interaction energies (kcal/mol) for pairs of oxanosine and guanine with cytosine and thymine determined at selected theoretical levelsa.

| Pair | Method | Energy |

|---|---|---|

| G·C | HF/6-31G(d) | –22.7 |

| B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) | –24.7 | |

| MP2/aug-cc-pVDZ | –27.7 | |

| AMBER | –27.6 | |

| G·T | HF/6-31G(d) | –12.0 |

| B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) | –13.4 | |

| MP2/cc-pVDZ | –14.1 | |

| MP2/aug-cc-pVDZ | –15.6 | |

| AMBER | –15.5 | |

| O·C | HF/6-31G(d) | –14.2 |

| B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) | –14.3 | |

| MP2/aug-cc-pVDZ | –16.4 | |

| AMBER | –18.6 | |

| O·T | HF/6-31G(d) | –7.3 |

| B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) | –7.4 | |

| MP2/aug-cc-pVDZ | –10.7 | |

| AMBER | –11.2 |

aAMBER, HF and MP2 values were determined using the HF/6-31G(d) geometry, whereas the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) optimized geometry was utilized in B3LYP calculations (see text for computation details). Best estimates are displayed in bold. In addition to these calculations, values determined at HF/6-311++G(d,p), HF/cc-pVDZ, MP2/6-311++G(d,p). B3LYP/6-31G(d) and MP2/cc-pVDZ are available upon request.

Table 5. Thermodynamic parameters for interaction of the different dimers in the gas phasea.

| Pair | ΔE | ΔH | ΔGb |

|---|---|---|---|

| G·C | –27.7 | –26.2 | –14.8 |

| –25.7 | –14.3 | ||

| G·T | –15.6 | –14.3 | –3.6 |

| –14.0 | –3.7 | ||

| O·C | –16.4 | –14.8 | –3.9 |

| –14.6 | –4.7 | ||

| O·T | –10.7 | –9.3 | –0.6 |

| –9.2 | –0.0 |

aEnergy values from MP2/aug-cc-pVDZ calculations (see Table 4). Enthalpies and entropies were determined from B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) and HF/6/31G(d) (bold) frequencies. All values are in kcal/mol.

bFree energy of dimerization computed using the ideal gas phase at 298 K and 1 atm as the reference state.

The preceding results suggest that the d(G·C)→d(G·T) mutation should greatly destabilize the duplex, since the gas phase binding energy decreases by >10 kcal/mol. The d(G·C)→d(O·C) substitution also reduces the stability of the duplex (>9 kcal/mol from high level QM calculations), but probably less than would be expected from the existence of repulsive interactions in the O·C dimer between O1(oxanosine) and N3(cytosine). In fact, the stability of the O·C pair is even greater than that found for the canonical A·T pair (39,40), which suggests that incorporation of O (paired to C) into DNA should not destroy the double helix, in agreement with low resolution data obtained from circular dichroism experiments (10). Finally, our calculations show that the d(O·C)→d(O·T) mutation leads to a moderate (∼5 kcal/mol) destabilization of the dimer. This result is not obvious from simple inspection of hydrogen bonding dimers (see Fig. 3) and demonstrates the complex nature of the nucleobase–nucleobase interactions.

Molecular dynamics simulations

MD simulations were used to examine the structural and energetic characteristics of the duplex DNA [d(CCAAXCTTGG)] with a normal d(G·C) step (denoted hereafter reference duplex) as well as with altered d(G·T), d(O·C) and d(O·T) pairs. The four trajectories are well equilibrated and the sampled structures correspond to double helical DNAs, the hydrogen bonding scheme being well preserved in all cases. The reference duplex belongs to the B family and shows a similar conformation to that found in the crystal, as noted in the RMSD (Table 6), the sugar puckerings and the helical parameters of the average structures (Table 7). In summary, MD samplings of the d(CCAAGCTTGG)·d(CCAAGCTTGG) duplex agree well with the experimental data for B-type duplexes.

Table 6. RMSd (in Å) between the different trajectories (row) and reference structures (columns)a for the decamer and the central hexamer (italic).

| Trajectory | Averageb | B-DNAc | A-DNAc | Average [d(G·C)]d | X-raye |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d(G·C) | 1.3 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.5) | 4.3 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.5) |

| 0.8 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.2) | 2.9 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.2) | |

| d(O·C) | 1.4 (0.3) | 2.4 (0.5) | 4.3 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.3) | – |

| 1.0 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.2) | 3.0 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | – | |

| d(G·T) | 1.5 (0.3) | 2.9 (0.4) | 4.3 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.3) | – |

| 0.8 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.2) | 2.9 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | – | |

| d(O·T) | 1.2 (0.3) | 2.7 (0.4) | 4.4 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.3) | – |

| 1.0 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.3) | 3.0 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.2) | – |

RMSD profiles showing the time evolution of the trajectories are available upon request.

aValues obtained using the last 0.5 ns for each trajectory. Standard deviations of the averages are in parentheses.

bMD averaged structure for the same trajectory obtained by averaging coordinates during the last 0.5 ns of the trajectory.

cCanonical models of A-DNA and B-DNA from Arnott and Hukins (40).

dMD averaged structure obtained for the trajectory of the duplex with the standard d(G·C) pair.

eX-ray structure for the duplex with the standard d(G·C) in Grzeskowiak et al. (24).

Table 7. Selected helical parameters for the MD averaged structure and MD averaged helical parameters (italic) for the four trajectories compared with experimental values.

| Parameter | d(G·C) | d(O·C) | d(G·T) | d(O·T) | Bfibera | Bcrystb | Afibera | Acrystb | X-rayc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rise | 3.25 | 3.23 | 3.21 | 3.28 | 3.32 | [3.3,3.4] | 3.42 | [3.3,3.5] | 3.35 |

| 3.3 (0.4) | 3.3 (0.4) | 3.3 (0.4) | 3.3 (0.4) | ||||||

| Twist | 33.2 | 32.4 | 32.6 | 31.0 | 35.8 | [34,36] | 30.9 | [31,32] | 35.4 |

| 32 (7) | 32 (7) | 32 (8) | 31 (8) | ||||||

| Inclination | 6.0 | 3.6 | 1.5 | –3.7 | –5.9 | [–0.4,1.7] | 19.2 | [1.4,12] | 1.7 |

| –2.6 (6) | –2.4 (6) | –7.4 (9) | –7.1 (7) | ||||||

| Roll | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 3.5 | –3.6 | [1.7,3.9] | 10.7 | [7.2,7.8] | 3.9 |

| 5.1 (11) | 4.0 (11) | 4.6 (11) | 3.7 (10) | ||||||

| X-disp | –1.6 | –1.4 | –1.0 | –1.3 | –0.7 | [–0.8,1.2] | –5.4 | [–4.4,–3.5] | 0.6 |

| –1.0 (0.6) | –0.9 (0.8) | –0.6 (1.2) | –0.8 (0.6) | ||||||

| Phase angle | 137 | 131 | 137 | 129 | 191 | [129,160] | 13 | [16,24] | 154 |

| 140 (36) | 139 (39) | 137 (22) | 133 (23) | ||||||

| m-gr. widthd | 12.1 | 12.4 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 11.7 | [10,13] | 17.0 | [15,16] | 13.2 |

| 11.8 (1) | 12.1 (1) | 12.1 (1) | 11.4 (1) | ||||||

| M-gr. widthd | 16.9 | 18.7 | 19.4 | 20.5 | 17.0 | [17,19] | 8.2 | [8,11] | 17.8 |

| 18.7 (2) | 19.8 (2) | 19.7 (2) | 20.3 (2) | ||||||

| χ | –113 | –116 | –110 | –119 | –98 | [–115,–97] | –154 | [–163,–158] | –99.2 |

| –112 (19) | –114 (20) | –115 (20) | –118 (23) |

Rotation parameters and angles are in degrees, translation parameters and groove dimensions are in Å. When ‘local’ and ‘global’ parameters are possible, ‘local’ values are shown. Helical parameters were determined with Curves 4.1 (38). Standard deviations of the averages are in parentheses.

aArnott and Hukins (40).

bRange of average helical values obtained from Curves 4.1 analysis of high resolution X-ray structures for B-DNA (PDB entries BD0023, BDJ051, BDJ061 and BDJ052) and A-DNA (ADL025, ADL045, ADL046, ADJ050 and ADJ051).

cShields et al. (26) (BD0052).

dM-gr. and m-gr. indicate the major and minor grooves, respectively. Width is measured as the minimum P-P distances (no vDW reduction).

Mutated duplexes belong to the B family (Tables 6 and 7). Mutations in the central d(G·C) step do not affect the general structure of the DNA. This is noted in the RMSD between the d(G·T), d(O·C) and d(O·T) trajectories and the MD averaged structure of the reference duplex (Table 6), as well as in the average helical parameters (Table 7). These findings agree with experimental data for d(G·T) mismatches in B-type DNAs of different sequences (41,42), which show that this mutation induces only small variations in the general helical properties of the DNA.

Let us now examine in more detail the local structure at and around the mutation site in the duplex. All the mutations decrease the twist and, in general, the deviation of inclination and opening at the mutation site (data not shown), probably reflecting the larger local distortion in the DNA induced by the mutated pairs. There is also a general widening of the grooves at the mutation site. However, all these local distortions have little effect on the general structure of DNA, in agreement with experimental findings for structures with a d(G·T) pair (41,42).

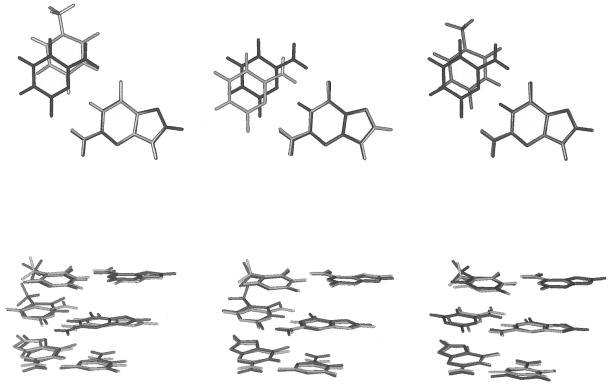

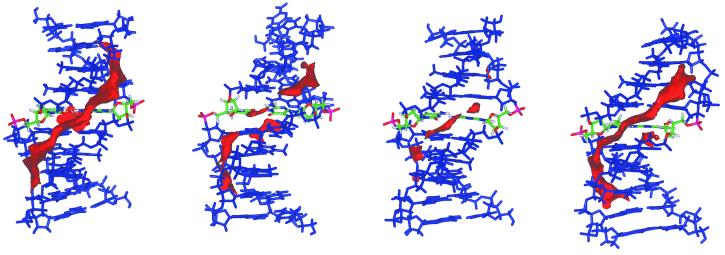

Figure 4 (top) shows superposition of the three mutated base pairs (as found in the average structures of the three mutated duplexes) on the reference pair [d(G·C)]. As expected from the gas phase calculations, the relative position of the pyrimidine varies between the different pairs. The mutated base pairs are also displaced, as noted in Figure 4 (bottom), which compares the positions of the three central steps [d(AXC)·d(GYT)] upon fitting of the base pair at position 4 [the d(A·T) pair] of the mutated structures to the reference duplex. Considering the position of the mutated base pair, with respect to the previous and following steps, a slight decrease in twist [from 2° for d(G·T) to 3° for d(O·T)] is found. This slight variation agrees well with experimental data for the crystal structure of a duplex containing a d(G·T) mutation (41), where the mutation is found to induce an average decrease of 1° in twist. Interestingly, the mutations lead to displacement of the bases from the canonical Watson–Crick pairing. For instance, in the mutation d(G·C)→d(O·C) the C is displaced to the major groove and in the mutation d(G·C)→d(G·T) G and T are displaced to form a wobble pairing (Fig. 4), as found experimentally (41). In summary, mutations introduce small alterations in the local structure of the duplex, but do not change the general structure of the helix.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the structures of the d(G·T), d(O·C) and d(O·T) pairs (dark) with the canonical d(G·C) one (light) as found in the average structures of the four trajectories. (Top) Structures are shown after superposition of the purine/pseudopurine. (Bottom) Structures are shown after superposition of the d(A·T) base pairs shown at the top.

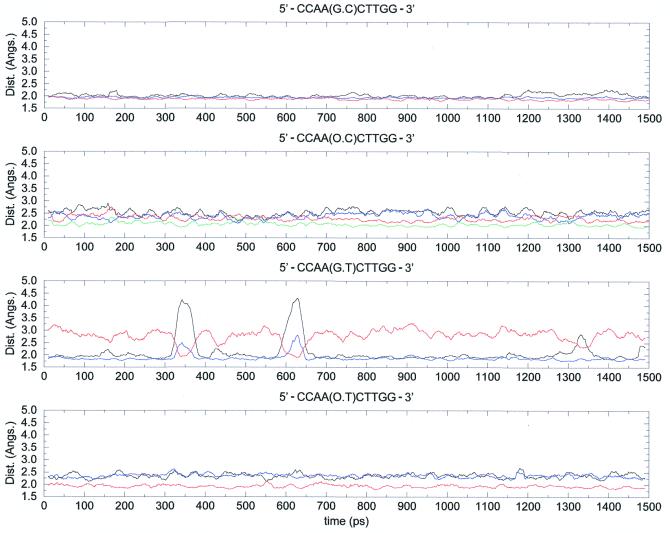

A dynamic view of the hydrogen bonding patterns of the base pairs can be gained from inspection of selected hydrogen bond distances during the trajectory (Fig. 5). Thus, the d(G·C) pair is quite rigid, as expected from the strength of the three canonical hydrogen bonds (see above). The d(G·C)→d(O·C) mutation increases the flexibility of the hydrogen bonded dimer, which fluctuates between binding modes, as expected from gas phase calculations. The hydrogen bond pattern of the d(G·T) pair suggests a partial breathing effect, similar to that previously found in DNAs containing one adenine·difluorotoluene pair (39). This ‘breathing movement’ might explain the efficiency of the DNA repair system in recognizing C→T mutations (43,44). Finally, the hydrogen bond scheme for the d(O·T) pair is not as flexible as that of the d(G·T) pair, but slight breathing movements and local changes in hydrogen bond patterns are clear in Figure 5. In summary, MD trajectories predict a more relaxed pattern of hydrogen bonded interactions and greater flexibility in mutated pairs compared to the canonical one, which reflects the lower strength of the hydrogen bond interactions.

Figure 5.

Changes in key hydrogen bonding distances during the four trajectories (time in ps, distances in Å). Distances plotted are: d(G·C) duplex [O6-H4 (black), H1-N3 (blue) and H2-O2 (red)]; d(G·T) duplex [O6-H3 (black), H1-O2 (blue) and H2-O2 (red)]; d(O·C) duplex [O6-H4 (black), H2-N3 (cyan), O1-H4 (red) and H2-O2 (blue)]; d(O·T) duplex [O6-H3 (black), O1-H3 (blue) and H2-O2 (red)]. In all cases the purine (pseudopurine) atom is noted first and the pyrimidine second.

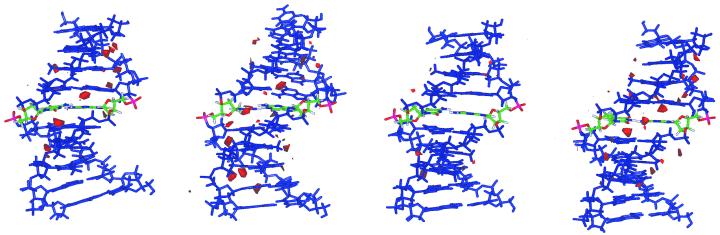

The preceding discussion indicates that the DNA is flexible enough to accept mutations without a dramatic distortion of its global structure, as already suggested by the experimental data (41,42). However, local changes in structure and flexibility induced by mutations are not negligible and can alter the reactivity of the DNA. To analyze this suggestion, molecular solvation maps and MIPs were computed using the procedure explained in Materials and Methods. MIPs are displayed in Figure 6 and solvation maps in Figure 7. The MIP contours show a region of negative potential located along the minor groove in all cases. This region of negative potential is reduced for all the mutated pairs (Fig. 6), especially around the mutation site. This suggests a reduction in reactivity in the minor groove induced by mutations.

Figure 6.

MIPs for the four DNA structures: from left to right d(G·C), d(G·T), d(O·C) and d(O·T). The mutation site is shown in a different color. A counter level of –5 kcal/mol is displayed. O+ was used as probe molecule.

Figure 7.

Molecular solvation map of the four DNA structures: from left to right d(G·C), d(G·T), d(O·C) and d(O·T). The mutation site is shown in a different color. A contour level corresponding to three times the density of pure water is displayed.

Analysis of solvation maps along the trajectories revealed the regions of preferential hydration of the DNA and the effect of mutations on the general hydration pattern of the helix (Fig. 7). The reference duplex shows a classical pattern of hydration with the ‘spine’ of water molecules arranged along the minor groove (45–48). This spine is weaker in the d(G·C) regions, but does not disappear at the contour level displayed (3.0 g/ml). Mutations, in general, reduce hydration in the minor groove, but slightly increase solvation in the major groove. It is worth noting that the d(G·C)→d(G·T) mutation generates a region of preferential solvation around N7(G), which agrees with the experimental location of two water molecules found in the crystal structure of a duplex containing the d(G·T) pair (42).

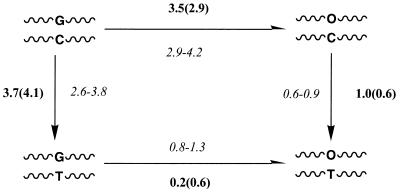

Free energy calculations

MD-TI calculations were performed to obtain theoretical estimates of the free energy changes associated with the changes G↔O and C↔T (see Materials and Methods). Calculations were performed using 420 (AMBER-95 and AMBER-99) and 820 (AMBER-95) ps simulations for duplexes and single-stranded DNAs. In all cases the free energy and differential free energy (ΔΔGλ = ΔGλduplex – ΔGλsingle strand) profiles were smooth without discontinuities. Free energy estimates obtained using the first (equilibration) and second halves (collection) of each window agree within a few tenths of a kcal/mol and the estimates computed using 420 and 820 ps trajectories are also quite similar irrespective of the force field used. A final test of the statistical quality of the results lies in closure of the thermodynamic cycle shown in Figure 8. Using an average of the values obtained from the six independent estimates (see above) of each mutation the cycle is closed with an error of 0.4 kcal/mol error. Overall, the results indicate that the simulation protocol is correct and that the estimated free energy values have small uncertainties.

Figure 8.

Theoretical (bold) and experimental (italics) estimates of the changes in stability induced by mutations. Estimates obtained indirectly by exact closure of the thermodynamic cycle (see text) are in parentheses. All the values are in kcal/mol.+

The statistical quality of the MD-TI calculations and the good performance of the force field (Table 4) support the reliability of the free energy estimates. Further support comes from the fact that the free energy difference between the C→T and G→O mutations in the single-stranded oligonucleotide in water and in the gas phase has to be similar to the difference in solvation free energy. Values of 4.3 ± 0.4 and 4.1 ± 0.2 kcal/mol are obtained for the difference in free energy of solvation between G and O and C and T. These values can be compared with MST/6-31G(d) (17–21) (5.5 and 4.7 kcal/mol, respectively). Considering the sources of error in both calculations, the agreement obtained is very satisfactory and reinforces confidence in the MD-TI estimates.

MD-TI calculations suggest that the d(G·C)→d(O·C) mutation is disfavored by 3 kcal/mol, indicating that only a small ratio of incorporation of 2′-deoxyoxanosine is expected in vivo. The d(G·C)→d(G·T) mutation is disfavored under physiological conditions, since it destabilizes the duplex by almost 4 kcal/mol. More interestingly, the corresponding mutation for 2′-deoxyoxanosine [d(O·C)→d(O·T)] is only slightly disfavored (<1 kcal/mol). Thus, this indicates a marked difference between G and O as far as their ability to selectively recognize C and T is concerned. This is also noted in the free energy difference for the mutation d(G·T)→d(O·T), which does not lead to any significant change in stability of the duplex.

Comparison of these results (Fig. 8) with gas phase energies of pairing (Table 5) shows qualitative agreement. Additional information can be obtained from the analysis of hydrogen bonding and stacking energies on the central d(AXC)·d(GYT) trimer along the four AMBER-99 trajectories. The results in Table 8 suggest that the mutation G→O does not introduce major changes in the stacking of DNAs, which is related to its similar electrostatic potential distribution in the aromatic plane (electrostatic potential above the aromatic rings of O and G are also very similar). In contrast, the change C→T weakens stacking (∼4 kcal/mol from Table 8) irrespective of the complementary base. All the mutations have a dramatic effect on the hydrogen bonding energy, which is reflected in the total stabilization energy of the central trimer (Table 8). Interestingly, the d(G·C)→d(G·T) mutation destabilizes the trimer by ∼17 kcal/mol, due mainly to the loss of hydrogen bonding (∼13 kcal/mol). On the other hand, the d(O·C)→d(O·T) mutation destabilizes the trimer by only 11 kcal/mol, due to the loss of ∼9 kcal/mol of hydrogen bonding energy. Therefore, these results indicate that the smaller loss of hydrogen bonding interactions due to the d(O·C)→d(O·T) mutation compared to d(G·C)→d(G·T) mutation is the main reason for the genotoxic properties of 2′-deoxyoxanosine.

Table 8. Stacking and hydrogen bond energies in the central trimer d(AXC)·d(GYT) obtained in the MD trajectoriesa.

| Pair | Ehydrogen bond | Estacking | Etotal |

|---|---|---|---|

| G·C | –63.8 (3.0) | –27.4 (2.2) | –91.2 (3.9) |

| G·T | –51.1 (2.6) | –22.8 (2.3) | –73.9 (3.4) |

| O·C | –54.4 (2.5) | –27.3 (2.0) | –82.7 (3.3) |

| O·T | –48.0 (2.3) | –23.1 (2.2) | –71.6 (3.5) |

aEnergy values (in kcal/mol) were obtained using the AMBER-99 force field by averaging over the last 0.5 ns of the trajectories. The three A·T, X·Y and C·T hydrogen bonds are considered to determine Ehydrogen bond. Both intra- and inter-strand stacking contributions are considered to determine Estacking.

bStandard deviations (in kcal/mol) are shown in parentheses.

Theoretical results obtained from MD-TI simulations (Fig. 8) clearly suggest a small ratio of d(G·C)→d(G·T) and d(G·C)→d(O·C) mutations in vivo. In fact, relative populations of 0.6 and 0.1% are predicted for d(O·C)/d(G·C) and d(G·T)/d(G·C) pairings. Therefore, the ratio of incorporation of mismatchings in the d(G·C) step is small, albeit not negligible considering the length of the DNA. Incorporation of 2′-deoxyoxanosine should be damaging to the genome since: (i) 2′-deoxyoxanosine is not eliminated by cellular excision repair systems (9–11); (ii) the preference of O to interact with C or T is very similar, which might lead to incorrect incorporation of T into the DNA.

MD-TI estimates of the differences in stability of duplexes with d(G·C), d(O·C), d(G·T) and d(O·T) pairs cannot be directly compared with experimental data, owing to the lack of suitable thermodynamic studies. Comparison with experimental data derived from incorporation into DNA by DNA polymerase (11) shows good qualitative agreement with the theoretical order of stability. Thus, the low (but detectable) efficiency of incorporation of O instead of G and the similar ratio of incorporation of O opposite to C and T found experimentally (11) is clearly explained by our theoretical calculations.

Rough estimates of the changes in stabilization free energies can be derived by: (i) assuming a linear relationship between experimental melting temperatures and stabilization free energies; (ii) using experimental heat capacities for similar DNA sequences (49–52). The values (Fig. 8) agree very well with our MD-TI calculations, giving strong support to the quality of our MD-TI results and to the conclusions derived from them.

In summary, state of the art theoretical calculations provide a detailed view of the effect of a G→O substitution on DNA structure, flexibility and reactivity. It is suggested that the incorporation of O instead of G might lead to an increase in the ratio of C→T mutations in duplex DNA. MD and MD-TI calculations suggest that the d(O·T) pair is quite stable, especially compared to the ‘canonical’ d(O·C) pair. Indeed, ‘breathing’ movements are rare and in fact appear to be more intense in the d(G·T) pair. Finally, the glycosidic bond of 2′-deoxyoxanosine is not labile. The complete results strongly suggest that the d(G·C)→d(O·T) lesion might not be repaired and the C→T mutation might exist for long enough to enter into a DNA replication cycle, leading then to a potentially dangerous d(G·C)→d(A·T) mutation.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Prof. J. Tomasi for providing us with a copy of the MST routines, which were modified by us to perform the present calculations. We also thank Dr T. Darden for technical help with the GIBBS module of AMBER-95. Computational facilities of the Centre de Supercomputació de Catalunya (CESCA, Molecular Recognition Project) are acknowledged. This work was supported by the Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica (DGICYT, PB98-1222 and PB96-1005) and the European Union (QLG1-CT-1999-00008). This is a contribution of the Centre Especial de Recerca en Química Teòrica.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shimada N., Yagisawa,N., Naganawa,H., Takita,T., Hamada,M., Takeuchi,T. and Umezawa,H. (1981) Oxanosine, a novel nucleoside from Actinomycetes. J. Antibiot., 34, 1216–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakamura H., Yagisawa,N., Shimada,N., Mezawa,H. and Iitaka,Y. (1981) The X-ray structure determination of oxanosine. J. Antibiot., 34, 1219–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yagisawa N., Shimada,N., Takita,T., Ishizuka,M., Takeuchi,T. and Umezawa,H. (1985) Mode of action of oxanosine, a novel nucleoside antibiotic. J. Antibiot., 35, 755–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato K., Yagisawa,N., Shimada,N., Hamada,M., Takita,T., Maeda,K. and Umezawa,H. (1984) Chemical modification of oxanosine. 1. Synthesis and biological properties of 2′-deoxyoxanosine. J. Antibiot., 37, 941–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uehara Y., Hasegawa,M., Hori,M. and Umezawa,H. (1985) Increased sensitivity to oxanosine, a novel nucleoside antibiotic, of rat-kidney cells upon expression of the integrated viral Src gene. Cancer Res., 45, 5230–5234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uehara Y., Hasegawa,M., Hori,M. and Umezawa,H. (1985) Differential sensitivity of Rsvts (Temperature-Sensitive Rous-Sarcoma Virus)-infected rat-kidney cells to nucleoside antibiotics at permissive and non-permissive temperatures. Biochem. J., 232, 825–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Itoh O., Kuroiwa,S., Atsumi,S., Umezawa,K., Takeuchi,T. and Hori,M. (1989) Induction by the guanosine analog oxanosine of reversion toward the normal phenotype of K-Ras-transformed rat-kidney cells. Cancer Res., 49, 996–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wink D.A., Kasprzak,K.S., Maragos,C.M., Elespuru,R.K., Misra,M., Dunams,T.M., Cebula,T.A., Koch,W.H., Andrews,A.W., Allen,J.S. and Keefer,L.K. (1991) DNA deaminating ability and genotoxicity of nitric-oxide and its progenitors. Science, 254, 1001–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki T., Yamaoka,R., Nishi,M., Ide,H. and Makino,K. (1996) Isolation and characterization of a novel product, 2′-deoxyoxanosine, from 2′-deoxyguanosine, oligodeoxynucleotide and calf thumus DNA treated by nitrous-acid and nitric-oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 118, 2515–2516. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki T., Matsamura,Y., Ide,H., Kanaori,K.,Tajima,K. and Makino,K. (1997) Deglycosylation susceptibility and base-pairing stability of 2′-deoxyoxanosine in oligodeoxynucleotide. Biochemistry, 36, 8013–8019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki T., Yoshida,M., Yamada,M., Ide,H., Kobayashi,M., Kanaori,K., Tajima,K. and Makino,K. (1997) Misincorporation of 2′-deoxyoxanosine 5′-triphosphate by DNA-polymerases and its implication for mutagenesis. Biochemistry, 37, 11592–11598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hariharan P.C. and Pople,J.A. (1973) The influence of polarization functions on molecular orbital hydrogenation energies. Theor. Chim. Acta, 28, 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee C., Yang,W. and Parr,R.G. (1998) Development of the Colle-Salveti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density Phys. Rev., 37B, 785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark T., Chandrasekhar,J., Spitznagel,G.W. and Schleyer,P.v.R. (1983) Efficient diffuse function-augmented basis-sets for anion calculations. 3. The 3-21+g basis set for 1st-row elements, Li-F. J. Comput. Chem., 4, 294–301. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frisch M.J., Trucks,G.W., Schlegel,H.B., Gill,P.M.W., Johnson,B.G., Robb,M.A., Cheeseman,J.R., Keith,T.A., Petersson,G.A., Montgomery,J.A., Raghavachari,K., Al-Laham,M.A., Zakrzewski,V.G., Ortiz,J.V., Foresman,J.B., Cioslowski,J., Stefanov,B.B., Nanayakkara,A., Challacombe,M., Peng,C.Y., Ayala,P.Y., Chen,W., Wong,M.W., Anfres,J.L., Replogle,E.S., Gomperts,R., Martin,R.L., Fox,D.J., Binkley,J.S., Defress,D.J., Baker,J., Stewart,J.J.P., Head-Gordon,M., Gonzalez,C. and Pople,J.A. (1995) GAUSSIAN 94 (Rev. A.1). Gaussian Inc., Pittsburgh, PA.

- 16.Luque F.J., Bachs,M. and Orozco,M. (1994) An optimized AM1/MST method for the MST-SCRF representation of solvated systems. J. Comput. Chem., 15, 847–857. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orozco M., Bachs,M. and Luque,F.J. (1995) Development of optimized MST/SCRF methods for semiempirical calculations. The MNDO and PM3 hamiltonians. J. Comput. Chem., 16, 563–575. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachs M., Luque,F.J. and Orozco,M. (1994) Optimization of solute cavities and van-der-Waals parameters in ab-initio MST-SCRF calculations of neutral molecules. J. Comput. Chem., 15, 446–454. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miertus S., Scrocco,E. and Tomasi,J. (1981) Electrostatic interaction of a solute with a continuum—a direct utilization of abinitio molecular potentials for the prevision of solvent effects. J. Chem. Phys., 55, 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miertus S. and Tomasi,J. (1982) Approximate evaluations of the electrostatic free-energy and internal energy changes in solution processes. J. Chem. Phys., 65, 239–245. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomasi J. and Persico,M. (1994) Molecular interactions in solution—an overview of methods based on continuous distributions of the solvent. Chem. Rev., 94, 2027–2094. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunning T.H. Jr (1989) Gaussian-basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. 1. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys., 90, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boys S.F. and Bernardi,F. (1970) The calculation of small molecular interactions by the differences of separate total energies. Some procedures with reduced errors. Mol. Phys., 19, 553–559. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grzeskowiak K., Goodsell,D.S., Kaczor-Grzeskowiak,M., Gascio,D. and Dickerson.R.E. (1993) Crystallographic analysis of C-C-A-A-G-C-T-T-G-G and its implications for bending in B-DNA. Biochemistry, 32, 8923–8931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jorgensen W.L., Chandrasekhar,J., Madura,J.D., Impey,R. and Klein,M.L. (1983) Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys., 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shields G., Laughton,C.A. and Orozco,M. (1997) Molecular-dynamics simulations of the D(T·A·T) triple-helix. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 199, 7463–7469. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soliva R., Luque,F.J. and Orozco,M. (1999) Can G-C Hoogsteen-wobble pairs contribute to the stability of d(G·C-C) triplexes? Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 2248–2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shields G.C., Laughton,C.A. and Orozco,M. (1998) Molecular-dynamics simulation of a PNA·DNA·PNA triple-helix in aqueous-solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 120, 5895–5904. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soliva R., Laughton,C.A., Luque,F.J. and Orozco,M. (1998) Molecular-dynamics simulations in aqueous-solution of triple helices containing d(G·C·C) trios. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 120, 11226–11233. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheatham T.E., Miller,J.L., Fox,T., Darden,T.A. and Kollman,P.A. (1995) Molecular-dynamics simulations on solvated biomolecular systems—the Particle Mesh Ewald method leads to stable trajectories of DNA, RNA and proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 117, 4193–4194. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Essmann U., Perera,L., Berkowitz,M.L., Darden,T., Lee,H. and Pedersen,L.G. (1995) A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys., 103, 8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryckaert J.P., Ciccote,G. and Berendsen,J.C. (1977) Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constrains: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys., 23, 327–332. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheatham T.E., Cieplak,P. and Kollman,P.A. (1999) A modified version of the Cornell et al. force-field with improved sugar pucker phases and helical repeat. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 16, 845–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bayly C.I., Cieplak,P., Cornell,W.D. and Kollman,P.A. (1993) A well-behaved electrostatic potential based method using charge restraints for deriving atomic charges—the RESP model. J. Phys. Chem., 97, 10269–10280. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cornell W.D., Cieplak,P., Bayly,C.I., Gould,I.R., Merz,K.M., Ferguson,D.M., Spellmeyer,D.C., Fox,T., Caldwell,J.W. and Kollman,P.A. (1995) A 2nd generation force-field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic-acids and organic-molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 117, 5179–5197. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson M. and Poirier,R. (1980) MonsterGauss. Department of Chemistry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada (modified 1987 by Cammi,R., Bonaccorsi,R. and Tomasi,J., University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy; further modified 1995 by Luque,F.J. and Orozco,M., University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain).

- 37.Case D.A., Pearlman,D.A., Caldwell,J.W., Cheatham,T.E., Ross,W.S., Simmerling,C.L., Darden,T.A., Merz,K.M., Stanton,R.V., Cheng,A.L., Vincent,J.J., Crowley,M., Ferguson,D.M., Radmer,R.J., Seibel,G.L., Singh,U.C., Weiner,P.K. and Kollman,P.A. (1997) AMBER 5. University of California, San Francisco, CA.

- 38.Lavery R. and Sklena,J. (1988) The definition of generalized helicoidal parameters and of axis curvature for irregular nucleic-acids. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 6, 63–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cubero E., Sherer,E.C., Luque,F.J., Orozco,M. and Laughton,C.A. (1999) Observation of spontaneous base-pair breathing events in molecular-dynamics simulation of a difluorotolueno-containing DNA oligonucleotide. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 121, 8653–8654 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arnott S. and Hukins,D.W.L. (1972) Optimised parameters for A-DNA and B-DNA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 47, 1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allawi H.T. and SantaLucia,J. (1998) NMR solution structure of a DNA dodecamer containing single G·T mismatches. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 4925–4934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hunter W.N., Brown,T., Kneale,G., Anand,N.N., Rabinovich,D. and Kennard,O. (1987) The structure of guanosine-thymidine mismatches in B-DNA at 2.5-Å resolution. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 9962–9970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kramer B., Kramer,W. and Fritz,H.J. (1984) Different base mismatches are corrected with different efficiencies by the methyl-directed DNA mismatch-repair system of Escherichia coli. Cell, 38, 879–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fersht A.R., Knill-Jones,J.W. and Tsui,W.C. (1982) Kinetic basis of spontaneous mutation—MIS-insertion frequencies, proofreading specificities and cost of proofreading by DNA-polymerases of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol., 156, 37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soliva R., Luque,F.J., Alhambra,C. and Orozco,M.(1999) Role of sugar re-puckering in the transition of A-form and B-form of DNA in solution—a molecular-dynamics study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 17, 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dickerson R.E. (1992) DNA-structure from A to Z. Methods Enzymol., 211, 67–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drew H.R., Wing,R.M, Takana,S., Broka,C., Tanaka,S., Itakura,K. and Dickerson,R.E. (1981) Structure of a B-DNA dodecamer—conformation and dynamics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 78, 2179–2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shui X., McFail-Isom,L., Hu,G.G. and Williams,L.D. (1998) The B-DNA dodecamer at high resultion reveals a spine of water on sodium. Biochemistry, 37, 8341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schweitzer B.A. and Kool,E.T. (1995) Hydrophobic, non-hydrogen-bonding bases and base-pairs in DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 117, 1863–1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moran S., Ren,R. and Kool,E.T. (1997) A thymidine triphosphate shape analog lacking Watson-Crick pairing ability is replicated with high sequence selectivity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 10506–10511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matray T.J. and Kool,E.T. (1998) Selective and stable DNA-base pairing without hydrogen-bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 120, 6191–6192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guckian K.M., Morales,J.C. and Kool,E.T. (1998) Structure and base pairing propierties of a replicable nonpolar isostere for deoxyadenosine. J. Org. Chem., 63, 9652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]