Abstract

Spontaneously ruptured aortic plaques are known to scatter frequently. Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is assumed to be exacerbated by aortic embolism besides local atherosclerosis. However, it has been challenging to show where the embolic plug came from. We estimated the embolic source of PAD in a 78-year-old male with a history of repetitive occlusion in the right peroneal artery by demonstrating and sampling using non-obstructive angioscopy (NOGA) for peripheral arteries and the aorta. Screening of the aorta, the iliac artery, and the femoral artery by computed tomography angiography, and NOGA revealed aortic dissection in the infrarenal abdominal artery. Four puff-chandelier ruptures that scattered like puffs were detected, and sampling was successful from puff-chandelier ruptures in the thoracic aorta, in the suprarenal abdominal artery, and in the dissected infrarenal abdominal artery. Among three puff-chandelier ruptures, a puff-chandelier rupture in the dissected infrarenal abdominal artery had the highest homology regarding the structure and the degree of fatty globules and cholesterol crystals. Endovascular graft replacement in the infrarenal dissected abdominal artery stopped the patient's repeated worsening of PAD.

Learning objective

The potential cause of peripheral artery disease is embolism from the upstream arteries beside local atherosclerosis. Homological comparison between materials from the occluded site and scattering plaques at the aorta and upstream arteries may suggest the embolic mechanism. In this case, repetitive occlusion in the right peritoneal artery was attributed to the embolism from the dissected infrarenal aorta because the highest homology was shown between the dissected infrarenal aorta where stent graft replacement stopped worsening of peripheral artery disease.

Keywords: Peripheral artery disease, Embolism, Atheroma, Angioscopy

Introduction

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is associated with high mortality with cardiovascular events [1]. Restenosis rates range after revascularization procedures up to 25 % [2]. One of the causes of PAD is embolism [3,4]. It has been challenging to identify the embolic source because the complex conditions of proximal stenosis and occlusion have made it challenging to observe only the distal peripheral regions.

Non-obstructive general angioscopy (NOGA) is an invasive imaging device to screen and sample atherosclerosis of the aorta and peripheral artery [5]. NOGA revealed that spontaneously ruptured aortic plaques (SRAPs) including atheromatous materials, cholesterol crystals (CCs), and fibrin were commonly scattered from the aorta to the downstream in patients with suspected or confirmed coronary artery disease [5]. The incidence of SRAPs in patients with suspected or confirmed coronary artery disease was 80.9 %. It is necessary to investigate where the embolism originated from in patients with PAD. However, there is no method for comparing the composition of embolic material at the embolized site and the composition of the embolic sources. We present a case of embolic origin of PAD investigated from debris sampled from SRAPs and occluded peripheral artery using NOGA.

Case report

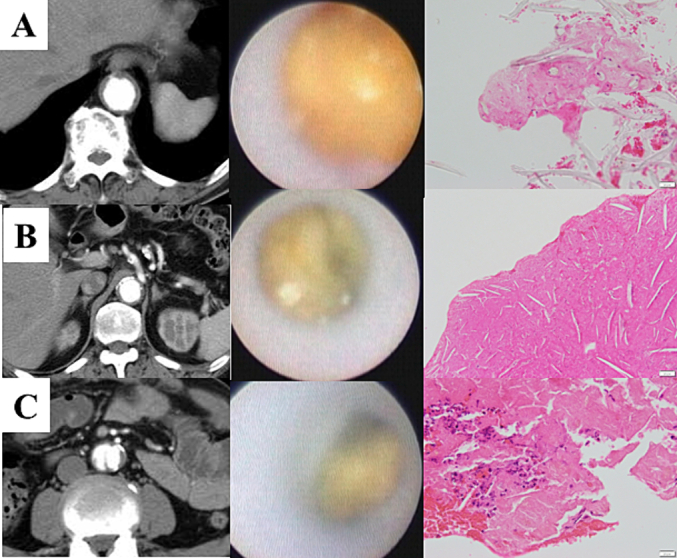

A 78-year-old male with a history of endovascular treatment (EVT) for the occlusion of the right superficial femoral artery 19 months previously was admitted with intermittent claudication. The patient had angina pectoris, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and chronic kidney disease. He did not recognize a symptom of strong abdominal or back pain. Two stents were implanted for the occlusion of the right superficial femoral artery 19 months previously [S.M.A.R.T. stent (Cordis, Miami Lakes, FL, USA) and MISAGO (Terumo Corp., Tokyo, Japan)] (Fig. 1A). The right ankle-brachial index (ABI) was improved to 0.91 from 0.43. He presented with rest pain in the right leg for the past two weeks. Aortography revealed an occlusion in the right anterior tibia artery (Fig. 1A). NOGA was performed to evaluate the occluded site [5]. It showed smooth white intima after aspirating puff-type emboli (Fig. 1B). After the aspiration of the emboli, no ruptured plaque was detected in the surroundings (Fig. 1C). Histopathological analysis stained with hematoxylin-eosin demonstrated atheroma (Fig. 1D). After aspiration, a good run-off was obtained (Fig. 1A). The right ABI was improved to 0.95 from 0.68. Two months after the second EVT, the patient suffered from pallor and pain in the skin of the right foot. The ABI of the right leg was decreased to 0.79. Invasive aortography revealed the occlusion of the right anterior tibial artery (Fig. 1A). Aspiration was successfully performed. Emboli consisting of atheroma were obtained at the second and third EVT (Fig. 1A). The atherosclerosis of the aorta or iliac artery was examined as repetitive embolism from upstream was suspected. Computed tomography angiography revealed a double lumen with a stenosed lumen suggested by asymptomatic aortic dissection in the infrarenal aorta. NOGA demonstrated many SRAPs and injuries, such as subintimal bleeding, fissure bleeding, and flap that were representative of aortic dissection at the double lumen, and puff-chandelier ruptures (PC) in the thoracic and the abdominal aorta (Video 1). No SRAP was detected in the right common iliac artery. Sampling was successfully performed from three representative SRAPs in the abdominal aorta (Fig. 2A–C). The pathological homology was analyzed between three PCs and emboli on second and third EVTs. The content, the extent of fatty globule, and the area ratio of CCs were evaluated. The area ratio of CCs was measured as the ratio of the area of needle-shaped cholesterol clefts to samples in hematoxylin-eosin stain using Image J 1.54d software (NIH, USA). Three rectangular areas were arbitrarily selected within the pathological tissue in atheroemboli, and three SRAPs and their ratio of CCs were calculated and averaged. The homology was analyzed between atheroemboli and three SRAPs by the tissue characteristics. The two emboli had the same characteristics as each other (Table 1). Two atheroemboli and puff-chandelier rupture in the suprarenal abdominal artery (PC-1; Fig. 2A) had one thing in common. Two atheroemboli and puff-chandelier rupture in the suprarenal abdominal artery (PC-2; Fig. 2B) had two things in common. Two atheroemboli and puff-chandelier rupture in the infrarenal abdominal artery had three things in common (PC-3; Fig. 2C). Thus, the highest degree of homology was observed between two atheroemboli and the PC-3 (Table 1). In a pathological comparison between atheroemboli and SRAPs, the highest degree of homology was observed between atheroemboli and the SRAP in the infrarenal abdominal aorta. Thus, the embolic source of recurrent occlusion was due to the SRAP in the infrarenal abdominal aorta. Graft replacement (AFX stent graft system; BA22-90/116/30, Japan Lifeline, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was performed in the infrarenal aorta. Although there is a limitation that all puff-chandelier ruptures were not analyzed, the patient has been free of recurrent limb symptoms such as rest pain or intermittent claudication for two years. Thus, the embolic source was thought to be PC- 3.

Fig. 1.

The clinical course, aortographic images, angioscopic images, and histopathological images.

A. The clinical course of the patient and aortography.

B. Angioscopic images before aspiration at the occluded site after endovascular treatment (EVT).

C. Angioscopic images after aspiration at the occluded site after EVT. A white smooth inner lumen removed emboli, suggesting embolic occlusion.

D. Histopathology of aspirated materials. Emboli consisting of atheroma with abundant fibrin and cholesterol crystals aspirated at second EVT.

Bar: 20 μm.

E. A histopathological image stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Bar: 50 μm.

Fig. 2.

Images of computed tomography aortography (left), angioscopic images of puff-chandelier rupture (mid), and histopathological images (right).

Bar: 20 μm.

A. Rupture at the diaphragm level consisted of fibrin-rich atheroma with macrophage and calcification (PC-1).

B. Rupture in the suprarenal abdominal aorta consisted of fibrin-rich atheroma with cholesterol crystals, macrophages, and calcification (PC-2).

C. Rupture in the true lumen of chronic aortic dissection at the infrarenal abdominal aorta with fibrin-rich atheroma with cholesterol crystals, macrophages, and calcification (PC-3).

Table 1.

Pathological homology between three puff-chandelier ruptures and emboli on second and third endovascular therapies.

| PC-1 | PC-2 | PC-3 | Emboli-1 | Emboli-2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | Fibrin-rich atheroma with macrophages and fibrin | Fibrin-rich atheroma with CCs, macrophages, and fibrin | Fibrin-rich atheroma with CCs, macrophages, and fibrin | Fibrin-rich atheroma with CCs | Fibrin-rich atheroma with CCs |

| Fat globule | Remarkable | Few | Few | Few | Few |

| The area ratio of CCs | ~0.1 % | 14.0 % | 2.02 % | 3.53 % | 2.20 % |

PC-1, puff-chandelier plaque in the suprarenal abdominal aorta; PC-2, puff-chandelier plaque in the suprarenal abdominal aorta; PC-3, puff-chandelier plaque in the dissected infrarenal abdominal aorta; Emboli-1, aspirated emboli at the second endovascular treatment; Emboli-2, aspirated emboli at the third endovascular treatment; CCs, cholesterol crystals.

Discussion

We confirmed that the repetitive occlusion events were caused by embolization in a patient with PAD. If a smooth, white tissue without SRAPs appears after aspiration at the occluded site with NOGA, the cause of the occlusion is likely embolism. Atheroembolism from the aorta is one of the leading causes of peripheral organs [5]. If SRAPs from the aorta cause PAD, it is expected that re-stenosis or re-occlusion of the lower limb arteries will repeatedly occur despite successful intervention. A-to-A embolism from the upstream of the peripheral arteries in patients with critical limb ischemia was proposed [6]. However, embolism from the aorta seems challenging to verify because no modality could detect SRAPs and sample emboli scattering from the SRAPs from the aorta and the peripheral artery. The case had an asymptomatic aortic dissection in the infrarenal abdominal artery. Aortic dissection is a hidden cause of embolism [7]. Intervention for aortic dissection may prevent repeated peripheral embolism if the emboli originated from the injured aortic wall of the dissected aorta [7]. We previously reported that remarkable atherosclerosis was found in a patient with chronic aortic dissection [8]. The current understanding has considered a relationship between embolic lesions and the presence of mobile plaques upstream if both are detected. Plaque characteristics such as CC content may vary on aortic plaques [9]. Our analysis can advance this correlation. It is possible to identify the source of the emboli by pairing it with the emboli themselves. The emboli that caused recurrent occlusion showed high similarity to the large arteries. Graft replacement for aortic dissection stopped repeated peripheral embolism. Ideally, all scattering-type plaques and emboli could be compared among them. The strategy may provide a hint for preventing recurrent restenosis or re-occlusion in PAD, although the accumulation of cases is needed.

Conclusions

The mechanism of repetitive occlusion in the right peroneal artery was shown to be the embolism from puff-chandelier rupture in the dissected infrarenal abdominal aorta.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Angioscopic videos of the anterior tibial artery before and after aspiration, computed tomography videos, and angioscopic videos of puff-chandelier ruptures in the suprarenal abdominal artery (PC-1, and PC-2), and in the infrarenal abdominal artery (PC-3).

Declaration of competing interest

Sei Komatsu is a technical consultant for Nemoto Kyorin-do Co. Ltd. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

We thank the Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Osaka University, for technical assistance.

Consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Caro J., Migliaccio-Walle K., Ishak K.J., Proskorovsky I. The morbidity and mortality following a diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease: long-term follow-up of a large database. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2005;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atmer B., Jogestrand T., Laska J., Lund F. Peripheral artery disease in patients with coronary artery disease. Int Angiol. 1995;14:89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McFarland R.J., Taylor R.S., Woodyer A.B., Eastwood J.B. The femoropopliteal segment as a source of peripheral atheroembolism. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1989;30:597–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campia U., Gerhard-Herman M., Piazza G., Goldhaber S.Z. Peripheral artery disease: past, present, and future. Am J Med. 2019;132:1133–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komatsu S., Yutani C., Ohara T., Takahashi S., Takewa M., Hirayama A., Kodama K. Angioscopic evaluation of spontaneously ruptured aortic plaques. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:2893–2902. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.03.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narula N., Dannenberg A.J., Olin J.W., Bhatt D.L., Johnson K.W., Nadkarni G., Min J., Torii S., Poojary P., Anand S.S., Bax J.J., Yusuf S., Virmani R., Narula J. Pathology of peripheral artery disease in patients with critical limb ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2152–2163. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimizu R., Sumi M., Murakami Y., Ohki T. False lumen thrombus following aortic dissection diagnosed as the source of repeat lower extremity emboli with angioscopy: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2022;8:65. doi: 10.1186/s40792-022-01416-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi S., Komatsu S., Takewa M., Kodama K. Demonstration of entry tear and disrupted intima in asymptomatic chronic thrombosed type B dissection with non-obstructive angioscopy. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-225268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komatsu S., Yutani C., Takahashi S., Takewa M., Iwa N., Ohara T., Kodama K. Cholesterol crystals as the main trigger of interleukin-6 production through innate inflammatory response in human spontaneously ruptured aortic plaques. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2023;30:1715–1726. doi: 10.5551/jat.64098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Angioscopic videos of the anterior tibial artery before and after aspiration, computed tomography videos, and angioscopic videos of puff-chandelier ruptures in the suprarenal abdominal artery (PC-1, and PC-2), and in the infrarenal abdominal artery (PC-3).