Abstract

Using data from a community-based lifestyle behavioral intervention study, this secondary data analysis investigated whether emotional coping, coping self-efficacy, and autonomous motivation mediated the association between the intervention and perceived stress in low-income overweight or obese mothers of young children. Results showed that coping self-efficacy significantly mediated the association between the intervention and perceived stress. However, emotional coping and autonomous motivation did not significantly mediate the association between intervention and perceived stress. Interventions may be more effective in helping the target audience reduce stress if they incorporate practical skills that can increase a sense of coping self-efficacy.

Keywords: autonomous motivation, coping self-efficacy, low-income, obesity, stress

Introduction

Low-income adults with high levels of perceived stress, defined as the degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as stressful (Cohen et al., 1983), contribute to health outcome disparities (Brotman et al., 2007). Perceived stress (hereafter referred to as stress) has been strongly associated with increased risk of major depression (Cohen et al., 2007), cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality (Cohen et al., 2007), stroke (Booth et al., 2015), and premature death (Keller et al., 2012). Also, perceive stress has been linked with obesity (Jackson et al., 2017), which is a strong predictor of cardiovascular disease (Zheng et al., 2017). Being low-income doubles one’s risk for cardiovascular disease (Braveman et al., 2010). Moreover, high levels of stress are prevalent in low-income overweight or obese women of child-bearing age (Chang et al., 2019b) and have been strongly associated with at least four concurrent chronic medical conditions (e.g. depression, type 2 diabetes, and angina) (Vancampfort et al., 2017). Low-income overweight or obese mothers of young children have reported that stress negatively affects their ability to eat healthier and be more physically activity, both of which are important factors associated with health outcomes (Chang et al., 2008b). Furthermore, maternal stress has been strongly associated with mothers’ inability to provide healthy meals to their young children (Berge et al., 2017), with offspring obesity (Baskind et al., 2019), and with children’s behavior problems (de Cock et al., 2017). Given the adverse effects of stress on health outcomes and its link with obesity and child behaviors, it is imperative to help reduce the stress of low-income overweight or obese mothers of young children.

To date, intervention studies aimed to promote mental health and well-being in women of child-bearing age have focused on depression rather than stress. Even if intervention studies aimed to reduce stress, the focus has been on postpartum women who abused drugs, had preterm births, were first-time mothers, or were highly distressed (Song et al., 2015). Although two lifestyle behavioral intervention studies aimed to promote weight loss in low-income women have included stress management, both studies reported no intervention effect on stress (Krummel et al., 2010; Walker et al., 2012). Similarly, another intervention study with low-income postpartum women that aimed to improve mental health did not find any intervention effect on stress (McFarlane et al., 2017). These studies suggest that there is not a good understanding of how to successfully reduce stress or improve mental health, highlighting the critical need to identify mechanisms associated with stress reduction in low-income overweight or obese mothers of young children.

We recently published results of a community-based randomized controlled lifestyle behavioral intervention for low-income overweight or obese mothers of young children (Chang et al., 2019a). The results reported by Chang et al. (2019a) indicated that the intervention group had significant improvement in emotional coping (p ⩽ 0.01, effect size (Cohen’s d, d) = 0.39), coping self-efficacy (p ⩽ 0.01, d = 0.53), and stress (p ⩽ 0.01, d = 0.34) compared with the comparison group by the end of the 16-week intervention. Autonomous motivation was measured at T1 and T2 but was not analyzed by Chang et al. (2019a). Therefore, alongside the possible roles of emotional coping and coping self-efficacy, the current analyses also examined whether autonomous motivation might also play a role. In the current secondary analysis of those data, we describe new analyses examining whether emotional coping, coping self-efficacy, and autonomous motivation do serve as potential mediators of intervention effects on changes in stress.

Theoretical and empirical evidence has suggested an association between stress and psychosocial factors, such as emotional coping, coping self-efficacy, and autonomous motivation. Based on Social Cognitive Theory, interventions that include emotional coping, defined as strategies to reduce, tolerate, or eliminate stress sensation, can improve various cognitive or mental processes that occur within the individual (Bandura, 1986). Also, individuals with higher coping self-efficacy, defined as one’s belief in his or her ability and efforts (in thought and action) to effectively manage stressful situations (Bandura, 1997), were more likely to report lower levels of stress than those with lower coping self-efficacy (Bandura, 1989). Moreover, prior studies have shown negative associations between stress and emotional coping (Prakash et al., 2015) and between stress and coping self-efficacy (Bosmans et al., 2015). According to Self-Determination Theory, interventions that facilitate autonomous motivation (Ryan and Deci, 2000), defined as the intrinsic value of achieving success (Murayama et al., 2010), can reduce stress, which has been supported by a prior study (Huang et al., 2016). Collectively, the literature underscores the importance of targeting emotional coping, coping self-efficacy, and autonomous motivation in stress management interventions. However, no prior studies have examined these concepts as mediators between an intervention and resulting stress.

Study objectives

This study addresses the critical gap in attempting to better understand how a lifestyle behavioral intervention reduces stress in low-income overweight or obese mothers of young children. Using data from a large community-based randomized controlled lifestyle behavioral intervention study aimed to prevent weight gain, this secondary data analysis investigated whether emotional coping, coping self-efficacy, and autonomous motivation plausibly mediated the association between the intervention and later reduced stress in the target population.

Methods

Participants and setting

Detailed descriptions of recruitment and study procedures have been published previously (Chang, 2017b). Briefly, participants were recruited between September 2012 to January 2015 from the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) in Michigan. WIC is a federally funded nutrition program serving individuals with annual household income at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty line—low-income pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding women and children (0–5 years). Trained peer recruiters invited potential participants in person to complete a pencil-and-paper screening survey, then measured each potential participant’s height and weight to compute body mass index (BMI). To be eligible to participate, women had to have a BMI of 25.0–39.9 kg/m2, be between 18 and 39 years old, and be between 6 weeks and 4.5 years postpartum. All eligible women signed consent forms before participating. The study was approved by the Michigan State University and Michigan Department of Community Health Institutional Review Boards.

Intervention

The 16-week lifestyle behavioral intervention had two components: viewing 10 intervention videos in DVD format at home and joining 10 peer support group teleconferences. The videos applied concepts of emotional coping and coping self-efficacy and the peer support group teleconferences were aimed at enhancing autonomous motivation. Each video (20 minutes per video) featured four overweight or obese WIC mothers of young children (featured mothers) with family members, mainly their young children, to connect with the viewers. The featured mothers provided testimonies and demonstrated practical tips to overcome daily challenges to better manage stress, eat healthier, and be more physically active. To improve participants’ emotional coping, the videos offered ways to identify and respond effectively to the triggers of negative emotions. To build participants’ coping self-efficacy, the videos were designed to help them think positively, become aware of their current life situations, identify root causes of problems, enhance their strengths, and recommend solutions to solve various problems. The peer support group teleconferences (30 minutes per session) were led by trained moderators who were peer educators or WIC dietitians. The moderators were trained in motivational interviewing. All peer support group teleconferences were audio-recorded with participants’ permission. A detailed description of the intervention has been reported previously (Chang et al., 2014).

Measures

Initially, demographic data were obtained via a pencil-and-paper survey while women waited for their WIC appointments. Then, at baseline (T1) and immediately after the 16-week intervention (T2), women completed a phone interview conducted by the study trained interviewers to provide data on emotional coping, coping self-efficacy, autonomous motivation, and stress.

Demographics.

The birthdate of each woman and her youngest child was used to calculate the participant’s age and duration of the postpartum period, respectively. Data were also collected on race, smoking, education, and employment status.

Emotional coping.

A scale with five items was used to measure emotional coping. This scale has established construct validity and reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha (α) = 0.91) in the target population (Chang et al., 2008a). An example item is, “In the past three months, how often do you deal with or prevent stress by taking a walk?” Response choices ranged from 1 (rarely or never) to 4 (usually or always). A higher mean score for the five items indicated better emotional coping (α: T1 = 0.60, T2 = 0.62).

Coping self-efficacy.

A scale with 10 items was used to measure coping self-efficacy. The scale has established construct validity and reliability (α = 0.92) in the target audience (Chang et al., 2003). One example scale item is, “In the past three months, how confident are you that you can relax, even when your kids scream.” Response choices ranged from 1 (not at all confident) to 4 (very confident). A higher mean score for the 10 items indicated higher coping self-efficacy (α: T1 = 0.80, T2 = 0.88).

Autonomous motivation.

The Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire (six items) with previous construct validity and reliability (α = 0.92) was used to measure autonomous motivation (Pelletier et al., 1997). Participants were asked why they engaged in better ways to deal with stress regularly in the past 3 months. One example of an item is, “because it is an important choice I really want to make.” Response choices ranged from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true). A higher mean score for the six items indicated higher autonomous motivation (α: T1 = 0.83, T2 = 0.84).

Perceived stress.

A nine-item Perceived Stress Scale, which has established predictive validity (correlation with stressful life events = 0.65) and reliability (α = 0.72), was used to measure the degree to which participants viewed their lives as being unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded during the past month (Cohen et al., 1983). Response choices ranged from 1 (rarely or never) to 4 (usually or always). A higher mean score for the nine items indicated a higher level of stress (α: T1 = 0.83, T2 = 0.84).

Statistical analysis

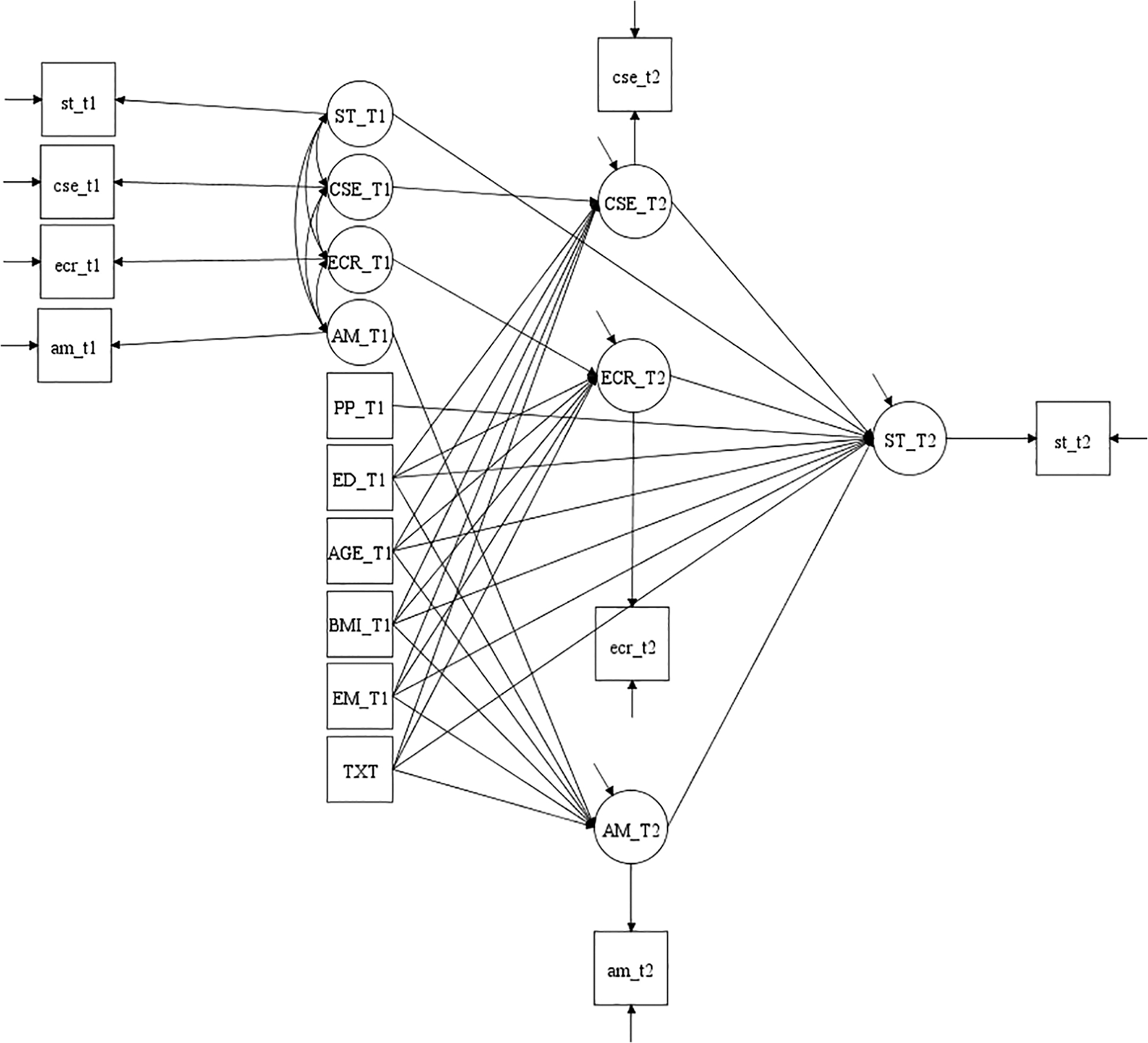

Mplus version 8 (Muthén and Muthén, 2007) was used to conduct the secondary data analysis of responses from the 338 (out of 569) women who completed both T1 and T2 phone interviews from a community-based randomized controlled lifestyle behavioral intervention. Bivariate tests (t-test and Chi-square test) were performed to examine the group differences in demographic variables. In the Mplus analyses, intervention was the exogenous variable (an independent variable or predictor). Stress was the endogenous variable (outcome or dependent variable). Potential mediators included emotional coping, coping self-efficacy, and autonomous motivation. Covariates included in the model were postpartum period, which has been associated with stress (Whitaker et al., 2014), education, age, BMI, and employment status. To investigate the mediation pattern, composite indicator structural equation (CISE) modeling was performed using maximum likelihood estimation adjusting for the T1 measures and the covariates (see Figure 1 for a depiction of the tested model).

Figure 1.

Structure of mediation model testing. CSE: coping self-efficacy; ECR: emotional coping; AM: autonomous motivation; ST: stress; Txt: intervention; PP: postpartum period; ED: education; BMI: body mass index; EM: employment status; T1: baseline; T2: immediately after the 16-week intervention.

CISE modeling is an errors-in-variables approach (Hausman et al., 2019) that models measurement errors in both exogenous and endogenous variables. Also, the CISE creates latent variables by combining the items of each separate measurement domain into a single indicator (McDonald et al., 2005). To control for measurement errors in our CISE model, the error variance of the indicator was fixed at (1 – α)*σ2, where α was Cronbach’s alpha and σ2 was the variance of the composite variable (Petrescu, 2013). There are advantages of using CISE modeling. It improves reliability by including measurement errors into the model, thereby reducing attenuation in estimates. Also, aggregating items in CISE modeling promotes a normal distribution, reduces the number of measured variables in models by combining items for each latent variable, and improves the parameter to sample size ratio (Petrescu, 2013). Model fit was assessed using the R2 value for the endogenous variable. The R2 value indexes the proportion of the variance in an outcome (dependent) variable that is explained by the set of predictors (independent variable and mediator variables) in a regression model. Effect size was calculated using the proportion of maximum possible (POMP) scores in the endogenous variable with per unit change in the exogenous variable. POMP = (parameter estimate/((maximum scale value – minimum scale value) + 1))*100 (Cohen et al., 1999).

Results

Demographics

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the study participants. There were no significant differences in age, BMI, race, smoking, and education between the intervention and comparison groups. However, there were significant differences between the two groups in postpartum period and employment status. Women in the comparison group had a longer postpartum period than those in the intervention group. Also, the comparison group had higher proportions of full-time employed and unemployed women and a lower proportion of homemakers than the intervention group.

Table 1.

Study participant characteristics.

| Characteristics | Intervention number (%) or mean (SD) | Comparison number (%) or mean (SD) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29.21 (4.92) | 29.63 (4.95) | 0.44 |

| Postpartum period (years) | 1.63 (1.23) | 1.99 (1.30) | 0.01 |

| Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) | 31.83 (4.34) | 31.53 (4.28) | 0.53 |

| Race | 0.08 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 179 (84.43%) | 97 (76.98%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 33 (15.57%) | 29 (23.02%) | |

| Smoking | 0.28 | ||

| Non-smoker | 175 (82.55%) | 98 (77.78%) | |

| Smoker | 37 (17.45%) | 28 (22.22%) | |

| Education | 0.47 | ||

| High school or less | 59 (27.83%) | 43 (34.12%) | |

| Some college or technical school | 100 (47.17%) | 54 (42.86%) | |

| College graduate or higher | 53 (25.00%) | 29 (23.02%) | |

| Employment status | 0.006 | ||

| Full-time | 34 (16.04%) | 32 (25.40%) | |

| Part-time | 46 (21.70%) | 28 (22.22%) | |

| Unemployed | 28 (13.21%) | 28 (22.22%) | |

| Homemaker | 79 (37.26%) | 28 (22.22%) | |

| Self-employed, student, and other | 25 (11.79%) | 10 (7.94%) |

SD: standard deviation.

N = 388: 212 intervention and 126 comparison.

Total effect of intervention

The overall effects of the intervention on stress were significant and negative (B = −0.147, p = 0.005, POMP = −3.77%; see Table 3). This finding means the intervention significantly decreased participants’ level of reported stress.

Table 3.

Direct and indirect effects of mediation testing while adjusting for baseline measures and covariates.

| Effect | B (SE) | 95% CI | p-value | β | POMP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect of intervention | |||||

| Treatment → stress_T2 | −0.147 (0.053) | −0.676, 0.645 | 0.005 | −0.156 | −3.77% |

| Direct effects | |||||

| Treatment → emotional coping_T2 | 0.134 (0.050) | 0.037, 0.232 | 0.007 | 0.169 | 3.52% |

| Treatment → coping self-efficacy_T2 | 0.316 (0.061) | 0.197, 0.435 | 0.000 | 0.262 | 7.90% |

| Treatment → autonomous motivation_T2 | 0.121 (0.084) | −0.44, 0.285 | 0.150 | 0.069 | 1.72% |

| Emotional coping_T2 → stress_T2 | −0.098 (2.217) | −4.443, 4.248 | 0.965 | −0.501 | −2.51% |

| Coping self-efficacy_T2 → stress_T2 | −0.392 (−0.074) | −0.537, −0.246 | 0.000 | −0.082 | −10.0% |

| Autonomous motivation_T2 → stress_T2 | 0.038 (0.035) | −0.030, 0.106 | 0.273 | 0.070 | 0.97% |

| Indirect effects (mediation) | |||||

| Treatment → emotional coping_T2 → stress_T2 | −0.013 (0.332) | −0.664, 0.638 | 0.969 | −0.014 | −0.33% |

| Treatment → coping self-efficacy_T2 → stress_T2 | −0.124 (0.032) | −0.187, −0.061 | 0.000 | −0.131 | −3.18% |

| Treatment → autonomous motivation_T2 → stress_T2 | 0.005 (0.006) | −0.007, 0.016 | 0.780 | 0.005 | 0.12% |

| Direct effects | |||||

| Treatment → stress_T2 | −0.015 (0.037) | −0.676, 0.645 | 0.964 | 0.016 | −0.38% |

| Other paths | |||||

| Postpartuma,b → stress_T2 | −0.001 (0.017) | −0.034, 0.032 | 0.961 | −0.002 | −0.02% |

| Educationa,c → stress_T2 | −0.015 (0.085) | −0.182, 0.151 | 0.857 | −0.031 | −0.38% |

| Agea,b → stress_T2 | −0.005 (0.014) | −0.031, 0.022 | 0.740 | −0.052 | −0.12% |

| BMIa,b → stress_T2 | 0.006 (0.014) | −0.022, 0.033 | 0.696 | 0.054 | 0.15% |

| Employment statusa,d → stress_T2 | 0.031 (0.156) | −0.274, 0.336 | 0.842 | 0.035 | 0.79% |

| Stress_T1 → stress_T2 | 0.575 (2.292) | −3.917, 5.068 | 0.802 | 0.478 | 14.78% |

| Emotional coping_T1 → emotional coping_T2 | 0.800 (0.107) | −0.041, 0.806 | 0.000 | 0.839 | 21.05% |

| Coping self-efficacy_T1 → coping self-efficacy_T2 | 0.383 (0.216) | 0.589, 1.010 | 0.076 | 0.478 | 9.57% |

| Autonomous motivation_T1 → autonomous motivation_T2 | 0.649 (0.068) | 0.517, 0.782 | 0.000 | 0.655 | 9.27% |

| Correlations between latent variables | |||||

| Stress_T1 with emotional coping_T1 | −0.560 (0.168) | 0.000 | |||

| Stress_T1 with self-efficacy_T1 | −0.667 (0.114) | 0.000 | |||

| Stress_T1 with autonomous motivation_T1 | −0.015 (0.062) | 0.801 | |||

| Emotional coping_T1 with coping self-efficacy_T1 | 0.460 (0.114) | 0.000 | |||

| Emotional coping_T1 with autonomous motivation T1 | 0.073 (0.060) | 0.226 | |||

| Coping self-efficacy_T1 with autonomous motivation_T1 | 0.016 (0.060) | 0.789 |

SE: standard error; CI: confidence interval; POMP: proportion of maximum possible scores in the endogenous variable (stress outcome) with per unit change in each exogenous variable (predictors); T1: baseline; T2: immediately post the 16-week intervention; B: unstandardized parameter; β: standardized parameter.

N = 338 (212 intervention, 126 control).

Covariates included in the model testing.

Postpartum status, age, and BMI (body mass index): continuous variables.

Education was coded as some high school or less, high school graduate, some college or technical school, and college graduate or higher.

Employment status was coded as a dummy variable: employed versus unemployed.

Direct and indirect (mediation) effects

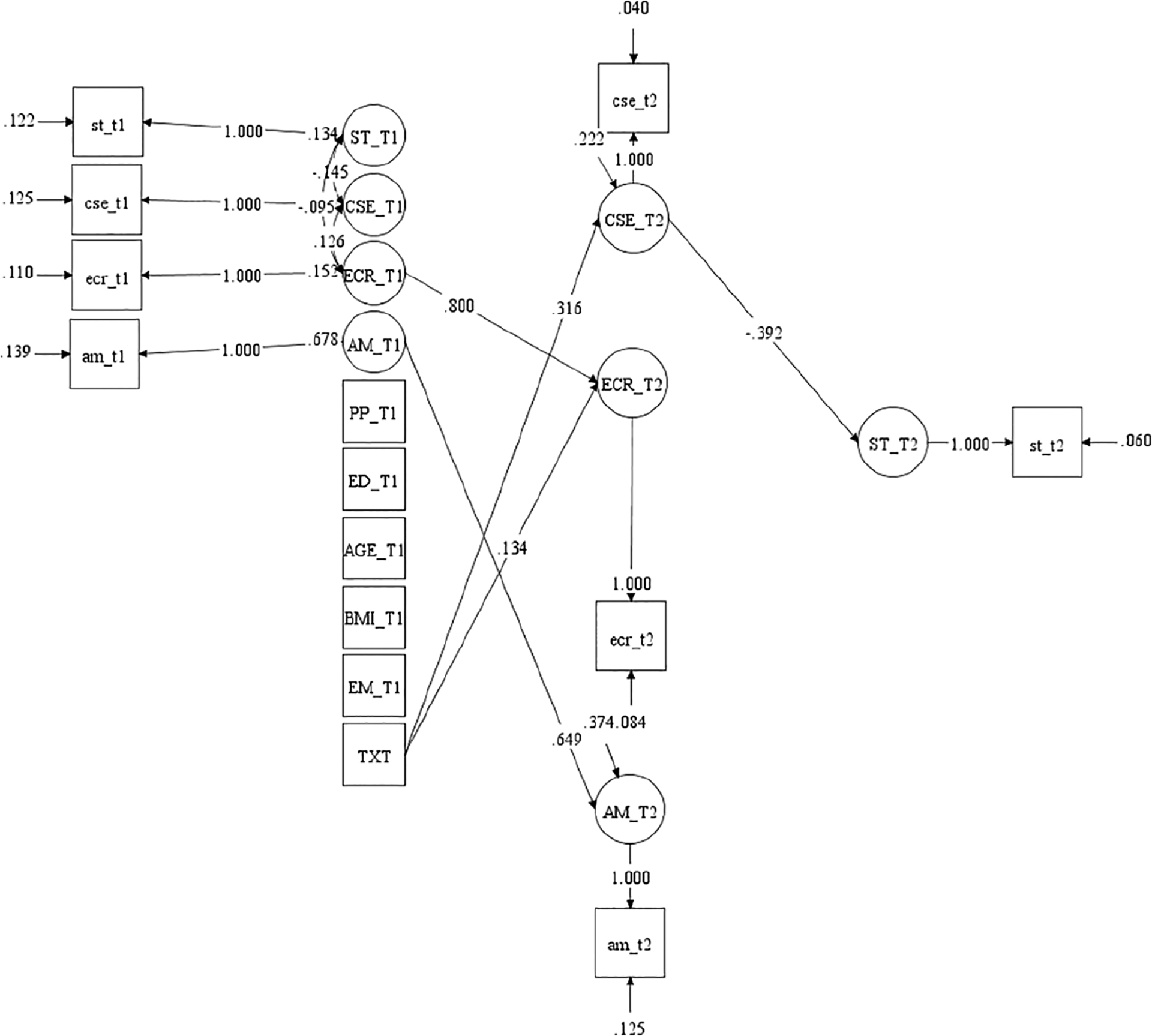

Table 2 presents the correlation matrix used for the model testing and mean (standard deviation (SD)) for each study variable. Table 3 shows the direct effects of the intervention on the three potential mediators (emotional coping, coping self-efficacy, and autonomous motivation), the associations between the three mediators and stress at T2 when controlling for the intervention, the indirect effects of the intervention on stress through the three mediators, and the direct effects of the intervention on stress when controlling for the influences of the three mediators. Figure 2 illustrates the significant paths from the mediation model testing. The R2 value was 0.70.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix.

| Study variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional coping_T1 (1) | 1.00 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.25 | −0.04 | 0.24 | 0.00 |

| Coping self-efficacy_T1 (2) | 1.00 | −0.01 | 0.43 | 0.25 | 0.34 | −0.04 | 0.27 | 0.05 | |

| Autonomous motivation_T1 (3) | 1.00 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.55 | −0.06 | −0.05 | ||

| Stress_T1 (4) | 1.00 | 0.35 | 0.39 | −0.04 | 0.57 | −0.06 | |||

| Emotional coping_T2 (5) | 1.00 | 0.46 | 0.06 | 0.50 | −0.14 | ||||

| Coping self-efficacy_T2 (6) | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.59 | −0.24 | |||||

| Autonomous motivation_T2 (7) | 1.00 | −0.07 | −0.09 | ||||||

| Stress_T2 (8) | 1.00 | −0.14 | |||||||

| Intervention (9) | 1.00 |

SD: standard deviation; T1: baseline; T2: immediately after the 16-week intervention.

Mean (SD) for each study variable—emotional coping response: T1 (2.89 (0.52)), T2 (3.05 (0.47)), coping self-efficacy: T1 (2.27 (0.79)), T2 (2.46 (0.59)), autonomous motivation: (3.82 (0.90)), T2 (3.96 (0.89)), stress: (2.54 (0.50)), T2 (2.43 (0.52)).

Figure 2.

Significant paths of mediation model adjusting for baseline measures and covariates. CSE: coping self-efficacy; ECR: emotional coping; AM: autonomous motivation; ST: stress; Txt: intervention; PP: postpartum period; ED: education; BMI: body mass index; EM: employment status; T1: baseline; T2: immediately after the 16-week intervention.

The intervention significantly improved women’s emotional coping (B = 0.134, p = 0.007, POMP = 3.52%) and coping self-efficacy (B = 0.316, p < 0.001, POMP = 7.90%) at T2. However, the intervention did not significantly increase women’s autonomous motivation at T2. When controlling for the intervention, neither emotional coping nor autonomous motivation was significantly associated with stress. However, coping self-efficacy was significantly and negatively associated with stress (B = −0.392, p < 0.001, POMP = −10.0%). Consistent with the lack of association relation with stress, when assessing the potential role of emotional coping and autonomous motivation as mediators, neither indirect effect of the intervention on stress through emotional coping or autonomous motivation was significant. However, when examining the potential role of coping self-efficacy as a mediator, the indirect effect of intervention on stress through coping self-efficacy was significant and negative (B = −0.124, p < 0.001, POMP = −3.18%). When controlling for the possible indirect effects of the intervention on stress through emotional coping, coping self-efficacy, and autonomous motivation, the intervention had no significant direct effect on stress. Overall, the result is consistent with coping self-efficacy mediating the association between the intervention and stress. However, emotional coping and autonomous motivation were not significant mediators.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating whether emotional coping, coping self-efficacy, or autonomous motivation might be responsible for the observed association between a lifestyle behavioral intervention and stress in low-income overweight or obese mothers of young children. Results of this study suggest that coping self-efficacy may have been a reason that the intervention reduced stress, but there was little indication that intervention effects relied on influences on emotional coping or autonomous motivation.

The finding that coping self-efficacy significantly mediated the association between the intervention and stress is supported in some ways by a previous intervention study of working mothers, aged 25–52 years. In that study, self-efficacy for physical activity (rather than for coping with stress) mediated the association between the behavior intervention and stress (Mailey and McAuley, 2014). The current study’s effect size for coping self-efficacy as a mediator was small (POMP = −3.18%). This small effect might have come about for a variety of reasons (e.g. participants had challenges in making specific plans for achieving small short-term goals and were unaware of benefits for making positive changes) based on the variety of reasons given on the randomly selected 25 percent of the audio recordings. Building on the key role for coping self-efficacy, future intervention studies might focus on helping participants with HOW to make specific and feasible plans/steps for achieving goals (e.g. using having a better relationship with family as a goal, the potential steps may include the following: listen carefully when family members speak, make a good eye contact, and use a clam and caring voice to talk) instead of the traditional approach of telling participants WHAT they should do to achieve their goals. Increasing people’s sense of knowing what to do increases self-efficacy and, therefore, decreases the uncertainty that might enhance stress. Also, for stress per se, helping participants identify benefits that they have received from making positive changes may be critical. Because peers of the target audience have similar life situations as the target audience, example strategies or behaviors from those peers can empower and motivate the target audience to make positive changes (Chang et al., 2017a). Therefore, researchers designing future interventions might consider using peers to deliver key parts of the intervention, for example, providing a variety of practical strategies that can be easily applied to women’s daily lives to achieve their goals.

In contrast to the two previous lifestyle behavioral intervention studies resulting in non-significant decreases in stress (Krummel et al., 2010; Walker et al., 2012), results of this intervention showed that our 16-week lifestyle behavior intervention effectively reduced stress in the target audience. One possible reason is that our intervention was mainly delivered via DVD and teleconferences, facilitating women’s participation. The two previous interventions applied a face-to-face format, limiting women’s participation due to their unpredictable schedules or lack of transportation or child-care. Our intervention effectively increased emotional coping and coping self-efficacy. However, the intervention had little influence on autonomous motivation for stress management. These findings might imply that the peer support group teleconferences to apply motivational interviewing techniques did not work as expected, perhaps because of difficulty finding a common time for each group members to meet due to women’s different schedules or changes in schedule over time (Chang et al., 2017a). Although the intervention significantly improved emotional coping, the improvement did not significantly contribute to a decrease in stress. It is possible that emotional coping improved symptoms of stress that were not measured in this study but did not influence the perceptions of stress that were measured. Future studies might consider examining the effect of emotional coping in relation to more specific stress symptoms rather than (or in addition to) more general perceptions of stress.

Limitations to the study

There are several study limitations. First, it was a secondary analysis that examined effects (mediation) that had not been previously examined. Therefore, it is difficult to know what level of power the tests might have had. If tests of one or more of the mediators were under-powered, that might mean that future studies involving a larger sample might garner support that was not obtained in the current research. Although there were significant differences in postpartum period and employment status between the intervention and comparison groups, the study findings did not change after including these two variables as covariates. Therefore, it seems unlikely that the effects of the intervention were actually due to unintended differences across conditions in postpartum period or employment. The study results may not be generalizable to low-income overweight or obese mothers who are from different racial/ethnic backgrounds because the study sample included predominately low-income Non-Hispanic White women. Finally, the study did not include an objective measurement of stress, such as cortisol (though cortisol may not be a good measure for individuals experiencing chronic stress; De Vente et al., 2003).

Conclusion

Results of this study indicated that coping self-efficacy was an important mediator in the association between the community-based lifestyle behavioral intervention, which included stress management, and stress. However, emotional coping and autonomous motivation were not identified as significant mediators in the association between the intervention and stress. Researchers conducting future intervention studies aimed to reduce stress might consider ways to emphasize coping self-efficacy in the intervention.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The lifestyle behavior intervention study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number: R18-DK-083934).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Trial registration

Clinical trials: NCT01839708.

References

- Bandura A (ed.) (1986) Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1989) Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist 44: 1175–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1997) Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Baskind MJ, Taveras EM, Gerber MW, et al. (2019) Parent-perceived stress and its association with children’s weight and obesity-related behaviors. Preventing Chronic Disease 16: E39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge JM, Tate A, Trofholz A, et al. (2017) Momentary parental stress and food-related parenting practices. Pediatrics 140: e20172295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth J, Connelly L, Lawrence M, et al. (2015) Evidence of perceived psychosocial stress as a risk factor for stroke in adults: A meta-analysis. BMC Neurology 15: 233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosmans MW, Hofland HW, De Jong AE, et al. (2015) Coping with burns: The role of coping self-efficacy in the recovery from traumatic stress following burn injuries. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 38: 642–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, et al. (2010) Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: What the patterns tell us. American Journal of Public Health 100(Suppl. 1): S186–S196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman DJ, Golden SH and Wittstein IS (2007) The cardiovascular toll of stress. Lancet 370: 1089–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MW, Brown R and Nitzke S (2008a) Scale development: Factors affecting diet, exercise, and stress management (FADESM). BMC Public Health 8: 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MW, Nitzke S, Brown R, et al. (2003) Development and validation of a self-efficacy measure for fat intake behaviors of low-income women. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 35: 302–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MW, Nitzke S, Brown R, et al. (2014) A community based prevention of weight gain intervention (Mothers In Motion) among young low-income overweight and obese mothers: Design and rationale. BMC Public Health 14: 280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MW, Brown R and Nitzke S (2017a) Results and lessons learned from a prevention of weight gain program for low-income overweight and obese young mothers: Mothers In Motion. BMC Public Health 17: 182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MW, Nitzke S, Brown R, et al. (2017b) Recruitment challenges and enrollment observations from a community based intervention (Mothers In Motion) for low-income overweight and obese women. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communication 5: 26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MW, Nitzke S and Brown R (2019a) Mothers In Motion intervention effect on psychosocial health in young, low-income women with overweight or obesity. BMC Public Health 19: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MW, Nitzke S, Guilford E, et al. (2008b) Motivators and barriers to healthful eating and physical activity among low-income overweight and obese mothers. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 108: 1023–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MW, Tan A and Schaffir J (2019b) Relationships between stress, demographics and dietary intake behaviours among low-income pregnant women with overweight or obesity. Public Health Nutrition 22: 1066–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J, Aiken LS, et al. (1999) The problem of units and the circumstance for POMP. Multivariate Behavioral Research 34: 315–346. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D and Miller GE (2007) Psychological stress and disease. Journal of the American Medical Association 298: 1685–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T and Mermelstein R (1983) A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 24: 385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vente W, Olff M, Van Amsterdam JG, et al. (2003) Physiological differences between burnout patients and healthy controls: Blood pressure, heart rate, and cortisol responses. Occupational & Environmental Medicine 60(Suppl. 1): i54–i61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cock ESA, Henrichs J, Klimstra TA, et al. (2017) Longitudinal associations between parental bonding, parenting stress, and executive functioning in toddlerhood. Journal of Child and Family Studies 26: 1723–1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausman J, Liu H, Luo Y, et al. (2019) Errors in the dependent variable of quantile regression models. NBER working papers, no. 25819. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Lv W and Wu J (2016) Relationship between intrinsic motivation and undergraduate students’ depression and stress: The moderating effect of interpersonal conflict. Psychological Reports 119: 527–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SE, Kirschbaum C and Steptoe A (2017) Hair cortisol and adiposity in a population-based sample of 2,527 men and women aged 54 to 87 years. Obesity 25: 539–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A, Litzelman K, Wisk LE, et al. (2012) Does the perception that stress affects health matter? The association with health and mortality. Health Psychology 31: 677–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krummel D, Semmens E, Macbride AM, et al. (2010) Lessons learned from the mothers’ overweight management study in 4 West Virginia WIC offices. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 42: S52–S58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RA, Behson SJ and Seifert CF (2005) Strategies for dealing with measurement error in multiple regression. Journal of Academy of Business and Economics 5: 80–97. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane E, Burrell L, Duggan A, et al. (2017) Outcomes of a randomized trial of a cognitive behavioral enhancement to address maternal distress in home visited mothers. Maternal and Child Health Journal 21: 475–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailey EL and McAuley E (2014) Physical activity intervention effects on perceived stress in working mothers: The role of self-efficacy. Women & Health 54: 552–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama K, Matsumoto M, Izuma K, et al. (2010) Neural basis of the undermining effect of monetary reward on intrinsic motivation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107: 20911–20916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK and Muthén BO (2007) Mplus Users Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier LG, Tuson KM and Haddad NK (1997) Client Motivation for Therapy Scale: A measure of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation for therapy. Journal of Personality Assessment 68: 414–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrescu M (2013) Marketing research using single-item indicators in structural equation models. Journal of Marketing Analytics 1: 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash RS, Hussain MA and Schirda B (2015) The role of emotion regulation and cognitive control in the association between mindfulness disposition and stress. Psychology and Aging 30: 160–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM and Deci EL (2000) Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist 55: 68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JE, Kim T and Ahn JA (2015) A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for women with postpartum stress. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing 44: 183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort D, Koyanagi A, Ward PB, et al. (2017) Perceived stress and its relationship with chronic medical conditions and multimorbidity among 229,293 community-dwelling adults in 44 low- and middle-income countries. American Journal of Epidemiology 186: 979–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LO, Sterling BS, Latimer L, et al. (2012) Ethnic-specific weight-loss interventions for low-income postpartum women: Findings and lessons. Western Journal of Nursing Research 34: 654–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker K, Young-Hyman D, Vernon M, et al. (2014) Maternal stress predicts postpartum weight retention. Maternal and Child Health Journal 18: 2209–2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Manson JE, Yuan C, et al. (2017) Associations of weight gain from early to middle adulthood with major health outcomes later in life. Journal of the American Medical Association 318: 255–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]