Abstract

Objective

The necessary training and certification of providers performing venous ablation has become a topic of debate in recent years. As venous interventions have shifted away from the hospital, the diversity of provider backgrounds has increased. We aimed to characterize superficial venous ablation practice patterns associated with different provider types.

Methods

We analyzed Medicare Fee-For-Service data from 2010 through 2018. Procedures were identified by their Current Procedural Terminology code and included radiofrequency ablation, endovenous laser ablation, chemical adhesive ablation (ie, VenaSeal; Medtronic, Inc), and mechanochemical ablation. These procedures were correlated with the practitioner type to identify provider-specific trends.

Results

Between 2010 and 2018, the number of ablation procedures increased by 107% from 114,197 to 236,558 per year (P < .001). Most procedures were performed by surgeons without vascular board certification (28.7%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 28.7%-28.8%), followed by vascular surgeons (27.1%; 95% CI, 27.0%-27.2%). Traditionally noninterventional specialties, which exclude surgeons, cardiologists, and interventional radiologists, accounted for 14.1% (95% CI, 14.1%-14.2%), and APPs accounted for 3.5% (95% CI, 3.4%-3.5%) of all ablation procedures during the study period. The total number of ablations increased by 9.7% annually (95% CI, 9.7%-9.8%), whereas procedures performed by APPs increased by 62.0% annually (95% CI, 61.6%-62.4%). There were significant differences between specialties in the use of nonthermal ablation modalities: APPs had the highest affinity for nonthermal ablation (odds ratio [OR], 2.60; 95% CI, 2.51-2.69). Cardiologists were also more likely to use nonthermal ablation (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.59-1.66). Similarly, the uptake of new nonthermal technology (ie, chemical adhesives) was greatest among APPs (OR, 3.57; 95% CI, 3.43-3.70) and cardiologists (OR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.81-1.91). Vascular surgeons were less likely to use nonthermal modalities (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.92-0.97), including new nonthermal technology in the first year of availability (OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.90-0.95).

Conclusions

The use of venous procedures has increased rapidly during the past decade, particularly as endovenous ablations have been performed by a wider practitioner base, including APPs and noninterventionalists. Practice patterns differ by provider type, with APPs and cardiologists skewing more toward nonthermal modalities, including more rapid uptake of new nonthermal technology. Provider-specific biases for specific ablation modalities might reflect differences in training, skill set, the need for capital equipment, clinical privileges, or reimbursement. These data could help to inform training paradigms, the allocation of resources, and evaluation of appropriateness in a real-world setting.

Keywords: Advanced practice provider, Endovenous ablation, Nonthermal ablation, Superficial venous reflux, VenaSeal

Article Highlights.

-

•

Type of Research: A retrospective review of prospectively collected data from the Medicare Fee-For-Service database

-

•

Key Findings: Between 2010 and 2018, the number of endovenous ablations for superficial venous disease more than doubled from 114,197 to 236,558 annually. Vascular surgeons performed 27.1% of ablations, and noninterventionalists (ie, specialties outside of surgery, cardiology, and radiology) and advanced practice providers (APPs) performed 14.1% and 3.5%, respectively. The annual growth rate of APP ablations (62.0%) surpassed the annual growth rate averaged among all practitioners (9.7%). APPs and cardiologists showed the greatest affinity toward nonthermal modalities (odds ratio, 2.60 and 1.62, respectively) and were also the most likely to be early adopters of the new nonthermal chemical adhesive modality VenaSeal (Medtronic, Inc; odds ratio, 3.57 and 1.86, respectively).

-

•

Take Home Message: The use of endovenous ablation has increased rapidly in the Medicare population due to increased volumes per practitioner type and adoption by a wider range of practitioners, including APPs. Practice patterns differ by practitioner type. Additional efforts should be made to corroborate the safety, efficacy, and appropriateness of ablation procedures by different providers in the real world to inform new paradigms in training and certification and ensure best practices.

Superficial venous insufficiency (SVI) is a prevalent disorder and can be associated with significant morbidity. Varicose veins are often the earliest clinical indicators of SVI, affecting about 30% to 50% of the adult population.1 In addition, 20% to 50% of patients will have symptoms such as swelling, heaviness, and restlessness. However, as the disease progresses, 3% to 5% of the adult population develop skin trophic changes ranging from pigmentation and dermatitis to lipodermatosclerosis and ulceration.2, 3, 4, 5 Chronic venous disease has a well-documented association with deterioration in quality of life.6, 7, 8

Historically, SVI was managed surgically with high ligation at the saphenofemoral junction with or without stripping of the great saphenous vein. Less commonly, treatment of small saphenous vein reflux is warranted with ligation at the saphenopopliteal junction. However, since the introduction of endovenous ablation in the early 2000s, minimally invasive treatments have achieved wide clinical uptake due to their high technical success rates, increased periprocedural comfort, and more rapid recovery times.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 These treatments include endothermal modalities, such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and endovenous laser ablation (EVLA), and nonthermal modalities, such as chemical adhesive ablation, mechanochemical ablation (MOCA), and chemical ablation with foam sclerotherapy.14,15

Endovenous approaches to SVI have enabled a wider provider population to offer treatment in a range of nonoperating room settings. In recent years much attention has been focused on the potential for overuse of vein ablation.16, 17, 18 As a result, the necessary training and certification of providers performing venous ablation have become a topic of debate. Little has been documented about the actual composition, growth, and practice patterns of various providers currently treating SVI. We aimed to characterize the practice patterns associated with provider training, with a focus on advanced practice providers (APPs) and traditionally noninterventional specialties (ie, specialties excluding surgery, cardiology, and radiology). Specifically, we used the Medicare Fee-For-Service database to examine the influence of provider background on the choice of vein treatment modality and the likelihood of clinical uptake of a new ablation technology.

Methods

Institutional review board approval and patient informed consent were not required, and the study adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was a retrospective review of the de-identified Medicare Fee-for-Service database from 2010 through 2018, a database with >2 million superficial venous interventions at the time of analysis, including >1.5 million ablations; 2018 was the most recent year of validated data available.

Venous procedures were identified by Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code and included thermal modalities, such as RFA (CPT code 36475) and EVLA (CPT code 36478), and nonthermal modalities, such as chemical adhesive ablation (CPT code 36482; ie, VenaSeal; Medtronic, Inc), and MOCA (CPT code 36473; ie, ClariVein; Merit Medical Systems, Inc). Other venous procedures were analyzed for comparison. These included microphlebectomy (CPT codes 37565 and 37566) and sclerotherapy (CPT code 36468). Certain procedures, including chemical adhesive ablation and MOCA, only had approved CPT codes after 2016.

Each procedure was then correlated with the practitioner type. The practitioner types listed in the database were consolidated into the following groups: “vascular surgeon,” “surgeon, other,” “cardiologist,” “radiologist,” “noninterventionalist,” and “advanced practice provider.” The practitioner specialty data reported by Medicare are based on the self-reported specialty of the provider to the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System and is thus publicly available. Each practitioner category encompassed a range of specialties and training credentials to capture the full spectrum of providers involved in superficial venous ablation. Table I lists the database specialties and credentials defined under each practitioner grouping. Thus, the APP category included certified clinical nurse specialist, certified registered nurse anesthetist, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, and anesthesiologist assistant. The noninterventionalist category was defined as the remainder of physician specialties, excluding surgical specialties, cardiology, and interventional radiology.

Table I.

Practitioner types

| Grouping | Specialty as recorded in Medicare database |

|---|---|

| APP | Certified clinical nurse specialist |

| Certified registered nurse anesthetist | |

| Nurse practitioner | |

| Physician assistant | |

| Anesthesiologist assistant | |

| Cardiologist | Cardiac electrophysiology |

| Cardiology | |

| Noninterventionalist | Anesthesiology |

| Critical care (intensivists) | |

| Dermatology | |

| Family practice | |

| General practice | |

| Internal medicine | |

| Obstetrics/gynecology | |

| Osteopathic manipulative medicine | |

| Pain management | |

| Pathology | |

| Pediatric medicine | |

| Physical medicine and rehabilitation | |

| Preventative medicine | |

| Podiatry | |

| Gynecological/oncology | |

| Sports medicine | |

| Physical therapist | |

| Radiologist | Diagnostic radiology |

| Interventional radiology | |

| Surgeon, other | Cardiac surgery |

| General surgery | |

| Orthopedic surgery | |

| Plastic and reconstructive surgery | |

| Hand surgery | |

| Vascular surgeon | Peripheral vascular specialist |

| Vascular surgery |

These data were used to evaluate provider-specific practice patterns and how they changed over time. Specifically, we investigated temporal changes in total venous ablation procedures and the rate of their growth compared with other superficial venous procedures over time. Additionally, we assessed the distribution of providers performing ablations, the settings in which ablations were performed, and the correlation between provider type and their ablation modality of choice. Given the emergence of new nonthermal modalities during the study period, we also explored the factors associated with the incorporation of these novel technologies into clinical practice.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 28 (IBM Corp). The two-proportion Z test was used to determine significance, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

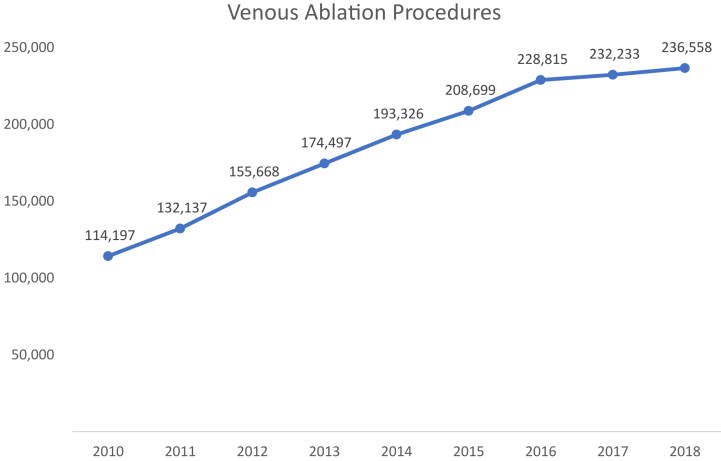

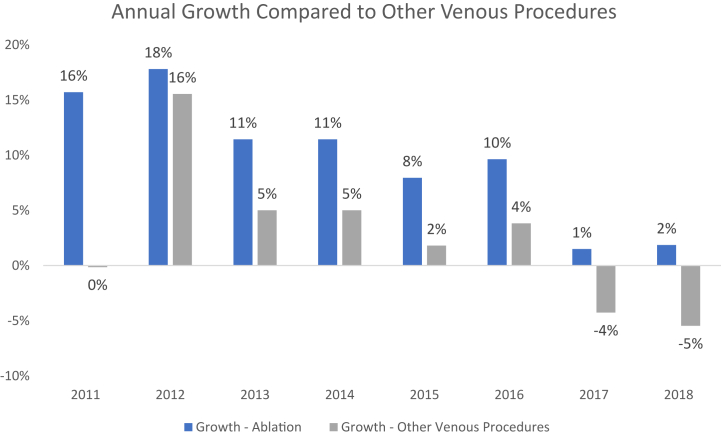

Between 2010 and 2018, the total number of venous ablation procedures increased by 107% from 114,197 to 236,558 annually (P < .001; Fig 1). This growth represented an average annual increase of 9.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 9.7%-9.8%) in total procedural volume. Other superficial venous procedures (ie, microphlebectomy and sclerotherapy) increased at an average annual rate of 5.3% from 2010 to 2016 and subsequently decreased by 4% to 5% annually from 2016 to 2018 (Fig 2). Early on, EVLA was the predominant modality used for endovenous ablation, comprising the majority (54.6%-59.9%; P < .05) of all ablations performed annually. After 2014, most cases of endovenous ablation transitioned to RFA (P < .05). Subsequently, with Food and Drug Administration approval of VenaSeal and its initial Medicare coverage in 2018, ablations with chemical adhesives accounted for 12.7% of all endovenous ablation procedures. This change coincided with a decrease in the use of thermal ablation modalities (P < .01). Based on available Medicare site-of-service data among key varicose vein CPT codes in 2018, >90% of ablations occurred in an office or ambulatory surgical center. Although most microphlebectomy and sclerotherapy procedures were also performed in this setting, more than one tenth of these other venous procedures were performed in hospitals on an outpatient basis.

Fig 1.

Total number of Medicare Fee-for-Service ablations annually. Venous ablation procedures includes the sum of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 36473, 36475, 36578, and 36482.

Fig 2.

Growth of venous ablation compared with other venous procedures. Other venous procedures includes the sum of stab phlebectomy veins (10-20; CPT code 37765), phlebectomy veins, extremity (≥20; CPT code 37766), and injections of spider veins (CPT code 36468).

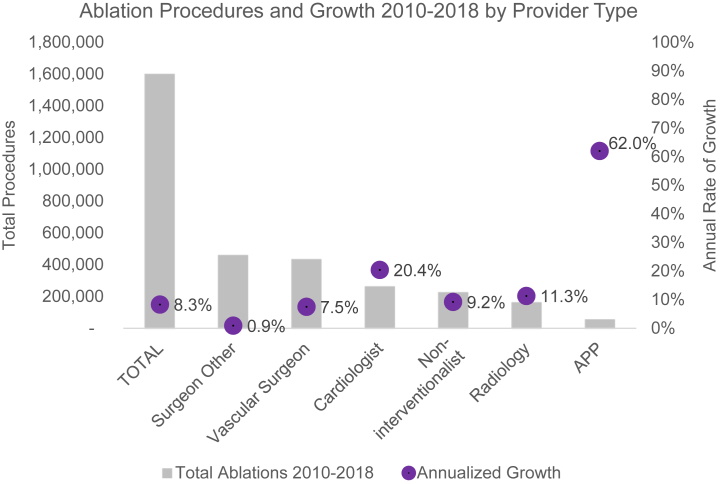

In stratifying procedural volume by provider background, we found that vascular surgeons performed only 27.1% of all endovenous ablations (95% CI, 27.0%-27.2%). Surgeons of other specialties accounted for the greatest procedural volume (28.7%; 95% CI, 28.7%-28.8%), and APPs performed the least (3.5%; 95% CI, 3.4%-3.5%). Despite their relatively low volume, APP procedures have increased at 62.0% annually (95% CI, 61.6%-62.4%), significantly faster than the 9.7% annualized growth rate of all providers performing ablations. In contrast, ablations by vascular surgeons and other surgeons grew the slowest by 7.5% (95% CI, 7.5%-7.6%) and 0.9% (95% CI, 0.8%-0.9%) annually, respectively (Table II; Fig 3).

Table II.

Volume and growth by provider type

| Provider type | Endovenous ablation procedures (2010-2018) |

|

|---|---|---|

| No., % of total (95% CI) | Annualized growth, % (95% CI) | |

| APP | 55,153 (3.5; 3.4-3.5) | 62.0 (61.6-62.4) |

| Vascular surgeon | 432,943 (27.1; 27.0-27.2) | 7.5 (7.5-7.6) |

| Surgeon, other | 459,139 (28.7; 28.7-28.8) | 0.9 (0.8-0.9) |

| Cardiologist | 262,257 (16.4; 16.4-16.5) | 20.4 (20.2-20.5) |

| Radiology | 162,385 (10.2; 10.1-10.2) | 11.3 (11.1-11.4) |

| Noninterventionalist | 225,549 (14.1; 14.1-14.2) | 9.2 (9.1-9.4) |

| Total | 1,597,426 (100.0) | 9.7 (9.7-9.8) |

APP, Advanced practice provider; CI, confidence interval.

Fig 3.

Volume and growth stratified by provider type. APP, Advanced practice provider.

Finally, we identified provider-specific preferences for different therapeutic modalities in superficial venous management. There was a broad distribution of provider types among the different ablation modalities, such that no modality was used exclusively by certain practitioners. However, cardiologists and APPs had the strongest affinity toward nonthermal ablation modalities (odds ratio [OR], 1.62; 95% CI, 1.59-1.66; P < .001; and OR, 2.60; 95% CI, 2.51-2.69; respectively). Conversely, surgeons—and, in particular, nonvascular surgeons (OR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.56-0.59; P = .005)—were less likely to use nonthermal modalities (Table III). During the study period, VenaSeal, a new nonthermal modality, was introduced. APPs were nearly four times more likely to use the new nonthermal modality than were other practitioners (OR, 3.57; 95% CI, 3.43-3.70; P = .001). Cardiologists also showed an affinity toward VenaSeal (OR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.81-1.91; P < .001). Surgeons outside of vascular surgery (OR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.50-0.53; P < .001) and noninterventionalists (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.53-0.58; P = .002) were approximately one half as likely to use VenaSeal (Table III).

Table III.

Modalities associated with provider types

| Provider type | Nonthermal ablation modality use |

VenaSeal uptake in first year |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| APP | 2.60 (2.51-2.69) | <.001 | 3.57 (3.43-3.70) | .001 |

| Vascular surgeon | 0.95 (0.93-0.97) | <.001 | 0.93 (0.90-0.95) | <.001 |

| Surgeon, other | 0.58 (0.56-0.59) | <.001 | 0.51 (0.50-0.53) | <.001 |

| Cardiologist | 1.62 (1.59-1.66) | <.001 | 1.86 (1.81-1.91) | <.001 |

| Radiology | 1.02 (0.99-1.05) | .014 | 1.14 (1.10-1.19) | .001 |

| Noninterventionalist | 0.87 (0.84-0.89) | .005 | 0.56 (0.53-0.58) | .002 |

APP, Advanced practice provider; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

This study highlights the general growth and the evolving clinical background of practitioners performing endovenous ablations in the Medicare patient population. By understanding the diverse composition of superficial venous specialists in the real world, we can inform a broad swath of initiatives in education, industry, and public policy to optimize treatment. We found that during the course of 9 years, the number of ablation procedures more than doubled. Vascular surgeons performed only a minority of these ablations, and noninterventionalists and APPs accounted for almost 18% of them. Ablations by APPs underwent the fastest growth, and APPs were the most likely to be early adopters of a novel nonthermal modality, followed by cardiologists.

The increase in the use of endovenous ablation in the Medicare population is likely multifactorial. The incidence of SVI is expected to increase in parallel with the increasing prevalence of its main risk factors (ie, age and obesity).19 As such, the data might reflect an increasing need for superficial venous treatment. However, the differential growth of endovenous ablation compared with other venous procedures indicates more than an increasing demand: we are witnessing a shifting paradigm in the de facto standard of care for SVI. The guidelines from the Society for Vascular Surgery, American Venous Forum, and American Vein and Lymphatic Society recommend treatment with endovenous ablation instead of high ligation and stripping for the management of symptomatic varicose veins and axial reflux.20 These recommendations are supported by myriad randomized controlled trials demonstrating similar rates of technical success between ablation and open surgery, although with less postoperative pain, faster recovery times, and fewer postoperative complications with the use of the former.21,22 Although the precipitous growth of endovenous ablation might, therefore, be expected, the breadth of practitioners driving this escalation is notable.

Physicians with formal vascular training are performing more ablations, as are practitioners with different training related to venous interventions, including noninterventionalists and APPs. In particular, this study might have captured the early part of a transition in the superficial venous workforce: ablations by APPs, although still small in volume, have grown at an annual rate far surpassing that of any physician. It is possible that by delegating procedures to APPs, physicians can scale revenue increases in their practices. The extent of physician oversight during APP procedures is not apparent in the Medicare database. The level of independence and specific procedures performed by APPs vary based on their training and experience and the laws in their jurisdiction. APPs do not typically perform highly invasive procedures unless in an assistive role. However, many states' laws regarding APPs’ scope of practice are vague. For instance, New Hampshire defines nurse practitioners' scope of practice as “providing such functions common to a nurse practitioner for which the APRN [advanced practice registered nurse] is educationally and experientially prepared and which are consistent with standards established by a national credentialing or certification body.” Furthermore, with dedicated postgraduate training, APPs have been shown to be proficient in independently performing certain minimally invasive procedures, such as arterial and venous catheterizations, intubations, and paracenteses or thoracenteses.23, 24, 25 Therefore, certain endovenous modalities, specifically nonthermal ablations that do not require laser privileges, might fall within specific APPs' scope of practice. Nevertheless, given the lack of standardized criteria to ensure procedural consistency and safety, these findings identify a new area for evaluation. The growth of ablations in this practitioner group, as well as in other nonvascular specialties, might be secondary to a greater awareness of superficial venous conditions, the increasing availability of diagnostic imaging modalities (ie, in-office duplex ultrasound), and overall procedural simplification.26,27

Thus, concerns have also been raised about overusage and safety. Multiple publications have shown an increasing number of ablations per patient in recent years, even after adjusting for patient-level variables.16,17 Crawford et al16 showed that 22% of providers performed greater than two ablations per patient on average, a practice that should only be reserved for the most complex cases. Specifically, specialties without any formal vascular training tended to perform more ablations per patient. Precipitated by accounts of inappropriate venous procedures, the American Venous Forum, in collaboration with other professional societies, developed criteria for the appropriate use of procedures to manage chronic lower extremity venous disease.28 In addition, a recent report of serious adverse events, including death, during cyanoacrylate closure, a modality preferentially used by APPs and cardiologists, could raise concerns regarding the safety of these procedures in the hands of nonformally trained operators.29 Disparate practice patterns suggest the need to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and appropriateness of treatments among different provider types in a real-world setting.

Moreover, provider-specific biases for specific ablation modalities might reflect differences in training and skill set. In general, vascular surgery, interventional radiology, and, in select cases, general surgery and cardiology have specific venous training.30,31 However, education on superficial venous management is largely deficient, even in certain vascular surgical programs.32 Rather, because ablation procedures are technically straightforward, short training sessions with device company representatives are often sufficient to learn and apply the steps of the procedure. Training on appropriate patient selection and application of this procedure is more controversial and might be less ubiquitous. Nonthermal ablation, which avoids tumescent anesthesia and considerations associated with heat injury, is a particularly streamlined intervention. It might be that with the explosion of nonthermal modalities, including VenaSeal, in the past decade, new providers performing ablation during this period are more accepting of new technologies in the absence of a precedent. After all, practitioners with the most growth, including APPs and cardiologists, had the highest affinity toward nonthermal modalities, including VenaSeal, and surgeons and noninterventionalists with the least growth had the least affinity.

Finally, provider-specific trends might also be influenced by the need for capital equipment and reimbursement. Due to the high costs of consumable items, venous ablation is perceived by many providers to be more expensive than traditional surgery.33 Surgeons' investment in equipment, including instrumentation, operating and recovery space, and anesthesia, might de-incentivize additional expenditures on these disposable items. This might partially explain their slow growth rate. Prior studies have also quantified the procedural costs for thermal and nonthermal modalities. Ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy is the least costly.34 RFA and EVLA procedural costs are less than those for MOCA and chemical adhesive ablation.35 However, VenaSeal has the highest Medicare reimbursement rates ($3826 per procedure) of all modalities, and reimbursements for ligation and stripping, RFA, EVLA, and MOCA are comparable to one another ($2366-$2612 per procedure).36 Notably, there have been significant cuts in Medicare reimbursement for vascular procedures. Venous procedures have experienced the largest cuts, with an average 42.4% decrease in inflation-adjusted reimbursements between 2011 and 2021. The adjusted reimbursement of endovenous ablation therapy specifically decreased by 34.3%.37 Consistent with the declining buying power of venous ablations, their growing procedural volume might partly reflect a compensatory increase to maintain financially viable practices. In reality, financial incentives are complex and also likely depend on various other factors, including overall cost-effectiveness and sunk costs of equipment and personnel for other types of procedures.

There are several limitations in this study. This was a retrospective review of the Medicare Fee-for-Service database. Therefore, the issues inherent to a retrospective review were present. In addition, the data were restricted to patients with Medicare coverage, and many superficial venous interventions are performed under private insurance, particularly with the younger demographic. These treatments would not be included in this analysis. Also, given the novelty of some modalities, they are frequently not covered initially under private insurance carriers. Therefore, the use of new nonthermal technology might be lower in the general population than represented in this study. We also did not assess local or regional factors contributing to the patterns. Finally, the indications and clinical outcomes for the procedures were not listed, because these are not available in the Medicare database. This makes it challenging to translate these data into an assessment of appropriateness.

Conclusions

The use of venous procedures has increased rapidly in the Medicare population, which has resulted from an increased volume per practitioner type and the adoption of venous interventions by a wider range of practitioners, including APPs. It also seems that APPs and cardiologists have skewed more rapidly toward the nonthermal modalities. Having identified the shear diversity of practitioner types performing ablations, additional efforts might be needed to determine how to best engage this broad range of practitioners and to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and appropriateness of provider-specific endovenous treatments in the real-world setting.

Author contributions

Conception and design: CW, MS

Analysis and interpretation: CW, EC, CR, GJ, MS

Data collection: CW

Writing the article: CW, EC, MS

Critical revision of the article: CW, EC, CR, GJ, MS

Final approval of the article: CW, EC, CR, GJ, MS

Statistical analysis: CW

Obtained funding: Not applicable

Overall responsibility: CW

Disclosures

None.

From the American Venous Forum

Footnotes

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the Journal policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Aslam M.R., Muhammad Asif H., Ahmad K., et al. Global impact and contributing factors in varicose vein disease development. SAGE Open Med. 2022;10 doi: 10.1177/20503121221118992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpentier P.H., Maricq H.R., Biro C., Ponçot-Makinen C.O., Franco A. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical patterns of chronic venous disorders of lower limbs: a population-based study in France. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:650–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham I.D., Harrison M.B., Nelson E.A., Lorimer K., Fisher A. Prevalence of lower-limb ulceration: a systematic review of prevalence studies. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2003;16:305–316. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200311000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher J. Measuring the prevalence and incidence of chronic wounds. Prof Nurse. 2003;18:384–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carradice D. Superficial venous insufficiency from the infernal to the endothermal. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:5–10. doi: 10.1308/003588414X13824511650498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carradice D., Mazari F.A., Samuel N., Allgar V., Hatfield J., Chetter I.C. Modelling the effect of venous disease on quality of life. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1089–1098. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan R.M., Criqui M.H., Denenberg J.O., Bergan J., Fronek A. Quality of life in patients with chronic venous disease: San Diego population study. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:1047–1053. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith J.J., Guest M.G., Greenhalgh R.M., Davies A.H. Measuring the quality of life in patients with venous ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31:642–649. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.104103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergan J.J., Kumins N.H., Owens E.L., Sparks S.R. Surgical and endovascular treatment of lower extremity venous insufficiency. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:563–568. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61648-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bush R.L., Ramone-Maxwell C. Endovenous and surgical extirpation of lower-extremity varicose veins. Semin Vasc Surg. 2008;21:50–53. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen A.J., Ulloa J.G., Torrez T., et al. Mechanochemical endovenous ablation of the saphenous vein: a look at contemporary outcomes. Ann Vasc Surg. 2022;82:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2021.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang L., Wang X., Wei Z., Zhu C., Liu J., Han Y. The clinical outcomes of endovenous microwave and laser ablation for varicose veins: a prospective study. Surgery. 2020;168:909–914. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2020.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marrocco C.J., Atkins M.D., Bohannon W.T., Warren T.R., Buckley C.J., Bush R.L. Endovenous ablation for the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency and venous ulcerations. World J Surg. 2010;34:2299–2304. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0659-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beale R.J., Mavor A.I., Gough M.J. Minimally invasive treatment for varicose veins: a review of endovenous laser treatment and radiofrequency ablation. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2004;3:188–197. doi: 10.1177/1534734604272245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhan H.T., Bush R.L. A review of the current management and treatment options for superficial venous insufficiency. World J Surg. 2014;38:2580–2588. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2621-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crawford J.M., Gasparis A., Almeida J., et al. A review of United States endovenous ablation practice trends from the Medicare Data Utilization and Payment Database. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2019;7:471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2019.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mann M., Wang P., Schul M., et al. Significant physician practice variability in the utilization of endovenous thermal ablation in the 2017 Medicare population. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2019;7:808–816.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2019.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mo M., Hirokawa M., Satokawa H., et al. Supplement of clinical practice guidelines for endovenous thermal ablation for varicose veins: overuse for the inappropriate indication. Ann Vasc Dis. 2021;14:323–327. doi: 10.3400/avd.ra.21-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies A.H. The seriousness of chronic venous disease: a review of real-world evidence. Adv Ther. 2019;36:5–12. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-0881-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gloviczki P., Lawrence P.F., Wasan S.M., et al. The 2022 society for vascular surgery, American venous Forum, and American vein and lymphatic society clinical practice guidelines for the management of varicose veins of the lower extremities. Part I. Duplex scanning and treatment of superficial truncal reflux: endorsed by the society for vascular medicine and the international union of phlebology. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2023;11:231–261.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2022.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siribumrungwong B., Noorit P., Wilasrusmee C., Attia J., Thakkinstian A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials comparing endovenous ablation and surgical intervention in patients with varicose vein. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44:214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farah M.H., Nayfeh T., Urtecho M., et al. A systematic review supporting the society for vascular surgery, the American venous Forum, and the American vein and lymphatic society guidelines on the management of varicose veins. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2022;10:1155–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2021.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kreeftenberg H.G., Aarts J.T., Bindels A.J.G.H., van der Meer N.J.M., van der Voort P.H.J. Procedures performed by advanced practice providers compared with medical residents in the ICU: a prospective observational study. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2 doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crum E.A., Varma M.K. Advanced practice professionals and an outpatient clinic: improving longitudinal care in an interventional radiology practice. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2019;36:13–16. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1683357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz J., Powers M., Amusina O. A review of procedural skills performed by advanced practice providers in emergency department and critical care settings. Dis Mon. 2021;67 doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2020.101012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eidson J.L., Atkins M.D., Bohannon W.T., Marrocco C.J., Buckley C.J., Bush R.L. Economic and outcomes-based analysis of the care of symptomatic varicose veins. J Surg Res. 2011;168:5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamel-Desnos C., Gérard J.L., Desnos P. Endovenous laser procedure in a clinic room: feasibility and side effects study of 1,700 cases [published correction appears in Phlebology. 2009 Aug;24(4):190] Phlebology. 2009;24:125–130. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2008.008040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masuda E., Ozsvath K., Vossler J., et al. The 2020 appropriate use criteria for chronic lower extremity venous disease of the American venous Forum, the society for vascular surgery, the American vein and lymphatic society, and the society of interventional radiology. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8:505–525.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsi K., Zhang L., Whiteley M.S., et al. 899 serious adverse events including 13 deaths, 7 strokes, 211 thromboembolic events, and 482 immune reactions: the untold story of cyanoacrylate adhesive closure. Phlebology. 2023;39:80–95. doi: 10.1177/02683555231211086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardman R.L., Rochon P.J. Role of interventional radiologists in the management of lower extremity venous insufficiency. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2013;30:388–393. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1359733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cameron S.J. Vascular medicine: the eye cannot see what the mind does not know. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2760–2763. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eidt J.F., Mills J., Rhodes R.S., et al. Comparison of surgical operative experience of trainees and practicing vascular surgeons: a report from the Vascular Surgery Board of the American Board of Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:1130–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shepherd A.C., Ortega-Ortega M., Gohel M.S., Epstein D., Brown L.C., Davies A.H. Cost-effectivness of radiofrequency ablation versus laser for varicose veins. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2015;31:289–296. doi: 10.1017/S0266462315000537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lattimer C.R., Azzam M., Kalodiki E., Shawish E., Trueman P., Geroulakos G. Cost and effectiveness of laser with phlebectomies compared with foam sclerotherapy in superficial venous insufficiency. Early results of a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;43:594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Epstein D., Bootun R., Diop M., Ortega-Ortega M., Lane T.R.A., Davies A.H. Cost-effectiveness analysis of current varicose veins treatments. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2022;10:504–513.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2021.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Physician Fee Schedule. Baltimore: U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/physicianfeesched/pfs-relative-value-files-items/rvu18a

- 37.Haglin J.M., Edmonds V.S., Money S.R., et al. Procedure reimbursement, inflation, and the declining buying power of the vascular surgeon (2011-2021) Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;76:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2021.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]