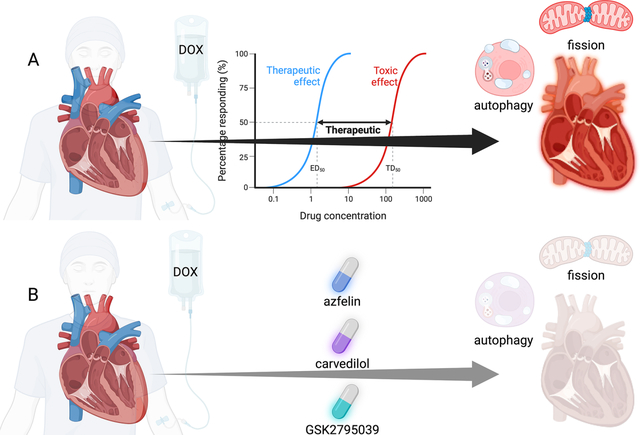

Graphical Abstract

Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity and potential interventions. (A) The mechanisms of anthracycline toxicity. Anthracycline causes dilated cardiomyopathy that can result in heart failure and arrhythmia. The mechanism of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity is dose dependent. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity is related to cardiomyocyte mitochondrial fission, necrosis, and autophagy. (B) Therapies that attenuate the effects of anthracycline on the heart include: afzelin, carvedilol, and GSK2795039 that mitigate the adverse effects of anthracyclines in vitro and in vivo.

Background

Anticancer treatment, while necessary and life-saving, often comes with a trade-off, particularly in the context of anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Anthracyclines remain a cornerstone of anti-cancer therapy for many malignancies. However, anthracycline-mediated cardiotoxicity causes significant morbidity and mortality and is irreversible. In this commentary, we highlight recent articles published in a Virtual Special Issue (VSI) on Recent Advances in the Cardiotoxicity of Anti-Cancer Drugs in Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology that contribute valuable insights into anthracycline-mediated adverse effects, mechanisms of toxicity, and potential therapies against cardiotoxicity of these potent chemotherapeutic agents.

Adverse effects of Anthracyclines

Cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin (DOX), the most powerful and efficacious of the anthracyclines, manifests acutely, but the effects may occur several years after administration as described in an up-to-date review of Bayles et al. (1). DOX causes cardiomyocyte death and fibrosis, leading to dilated cardiomyopathy. However, arrhythmias are also associated with DOX, including supraventricular arrhythmias. Durço, et al. investigate cotreatment with d-limonene (DL) plus hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HβDL) in attenuating cardiac arrhythmias in a Swiss mice model of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity (2). Arrhythmias were exacerbated in their model. Their study suggested that the observed cardioprotective effects of HβDL prevented triggered arrhythmia in a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMKII) manner. Although HβDL does not improve DOX-induced cardiomyopathy, it might mitigate arrhythmia that causes heart failure exacerbation and reduce hospital admissions.

In addition to cardiac effects, DOX is linked to metabolic complications, which can eventually lead to cardiovascular disease; however, the mechanisms are poorly understood. To study the effects of DOX, Postmus et al. used (Ldlr−/−)-p16–3MR mice to test the contribution of p16Ink4a+-senescent cell accumulation and cardiometabolic disease development (3). While their study did not find a link between DOX treatment and p16Ink4a+-senescent cells in the development of diet-induced cardiometabolic disease, there is clearly a need to understand better the mechanisms of DOX-mediated metabolic dysfunction, and thus, further investigations are merited.

Mechanisms of Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity (dose, pathways, alternative uses)

DOX-mediated cardiotoxicity remains poorly understood, with the effect of dose on the myocardium and the form of cell death unclear. Kawalec et al. explore the differential impact of DOX dose on cell death during acute cardiotoxicity (4). The authors investigate the effects of low and high-dose DOX in C57BL/6J mice. Surprisingly, the authors find that low doses did not affect cardiac structure or function, yet the high dose of DOX is several-fold higher than the dose used clinically -- a high dose causes significant necrosis. Low dose is associated with the apoptosis pathway, while high dose is associated with autophagy. While these results might suggest that dosing could significantly alter DOX-mediated cardiotoxicity, the model does not fully explain the patient-specific nature of the disease because not all patients experience cardiotoxicity.

More mechanistic cardiotoxicity studies might reduce cardiotoxicity by identifying novel drug targets to prevent cardiotoxicity. Pirarubicin is an anthracycline drug with less cardiotoxicity than DOX. However, Duan et al. investigated how Ring Finger Protein 10 promotes pirarubicin-induced cardiac inflammation via the AP-1/Meox2 signaling pathway (5). This study contributes valuable knowledge to the intricate signaling pathways involved in anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Importantly, the authors identify Ring Finger Protein as a target to reduce cardiovascular toxicity of pirarubicin, yet it remains to be tested if DOX (and other anthracyclines) stimulates this pathway.

Similarly, Xu et al. uncover that Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel subfamily C member 6 (TRPC6) promotes daunorubicin-induced mitochondrial fission and cell death using embryonic rat H9c2 cells as their model for cardiotoxicity (6). Using siRNA, the authors found that TRCP6 knockdown prevents mitochondrial fission and cell death. The study also reveals that daunorubicin (another anthracycline) activates the ERK1/2-DRP1 pathway via TRPC6. Thus, this study provides molecular insights into anthracyclines-induced mitochondrial dynamics and cardiotoxicity and might be a potential new target to prevent adverse cardiovascular events. Again, it will be valuable to see how much overlap there is between different anthracycline drugs and these newly revealed targets.

Mitigating the effects of DOX and potential therapeutic approaches

The adverse effects and mechanistic studies shed light on the cardiotoxicity of anthracyclines. However, several articles found potential therapies to mitigate their adverse effect, including nutraceuticals such as ononin and afzelin with a strong structure activity analysis of natural bioactive compounds that augment DOX inhibition of topoisomerase II-alpha activity yet enhance safety (7). Specifically, ononin is an isoflavone that may prevent anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Zhang et al. test the cardioprotective effect of ononin using H9c2 cells and Wistar rats exposed to DOX (8). Their study reveals that ononin alleviates endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by activating sirtuin 3 (SIRT3). Ononin also improves cardiac function in rats in vivo. Thus, ononin is a promising candidate for mitigating the effects of ER stress caused by DOX. Similarly, Sun et al. explored using afzelin, a flavanol glycoside found in Houttuynia cordata, to mitigate the adverse effects of DOX (9). Using H9c2 cells as their model, the authors discovered that afzelin protected against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by improving cell survival, preventing apoptosis, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Moreover, studies in C57Bl/6 mice show afzelin treatment attenuates cardiotoxicity. The authors found that the AMPKα/SIRT1 signaling pathway mediated afzelin’s cardioprotective effects. Although these are promising results, translating nutraceuticals into clinical usage may be challenging because of the costs associated with performing clinical trials and the large doses needed in humans, even with allometric scaling.

Zidan et al. use a more conventional therapy to investigate beta-blockers as cardioprotective therapies with DOX in murine models (10). Zidan et al. used carvedilol or nano-formulated carvedilol and found that carvedilol treatment prevents DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. While the results were compelling, beta blockade is used to treat DOX-cardiomyopathy, and cotreatment may mask the cardiotoxicity of DOX. It would be interesting to see if the cardioprotective effects of beta-blockade persisted after cessation of DOX. However, previous epidemiological data supports using beta-blockers to prevent anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy.

Lastly, Zhang et al. explore a novel small molecule inhibitor, GSK2795039, for preventing DOX-induced cardiomyopathy (11). GSK2795039 is a novel small molecular NADPH oxidase 2 (Nox2) inhibitor. GSK2795039 prevented RIP1-RIP3-MLKL-mediated cardiomyocyte necroptosis in doxorubicin-induced heart failure using H9c2 cell and murine models. By inhibiting NADPH oxidase-derived oxidative stress, GSK2795039 emerges as a protective agent for anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. However, these novel compound entities require rigorous absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion screening before being tested for utility as a clinically available therapeutic for humans.

Conclusion

In conclusion, these studies contribute to a deeper understanding of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity and its mechanism as stated here, and also as covered in a thorough review of Bayles et al., (1). Moreover, these findings offer innovative strategies to mitigate anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. Thus, as we navigate the intricate landscape of anticancer drug cardiotoxicity research, we can expect a new armamentarium of cotreatments to mitigate the adverse effects of anthracyclines and other drugs to make cancer treatments more effective and safer well into the future. There remains however a need to move our models into addressing individualized or personalized approaches (e.g., human induced pluripotent stem cells) given that not all cancer patients develop cardiotoxicity with anthracycline or other anti-cancer therapies.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the effort of Sujith Dassanayaka, Ph.D., to propose and to organize the topic for this VSI. Mark Chandy holds the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario/Barnett Ivy Chair.

Funding

This work was supported by the Jewish Heritage Fund for Excellence (DJC) and NIH P30GM127607 (DJC).

References

- 1.Bayles CE, Hale DE, Konieczny A, Anderson VD, Richardson CR, Brown KV, Nguyen JT, Hecht J, Schwartz N, Kharel MK, Amissah F, Dowling TC, and Nybo SE. Upcycling the anthracyclines: New mechanisms of action, toxicology, and pharmacology. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 459: 116362, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durco AO, Souza DS, Rhana P, Costa AD, Marques LP, Santos L, de Souza Araujo AA, de Aragao Batista MV, Roman-Campos D, and Santos M. d-Limonene complexed with cyclodextrin attenuates cardiac arrhythmias in an experimental model of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: Possible involvement of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 474: 116609, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Postmus AC, Kruit JK, Eilers RE, Havinga R, Koster MH, Johmura Y, Nakanishi M, van de Sluis B, and Jonker JW. The chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin does not exacerbate p16(Ink4a)-positive senescent cell accumulation and cardiometabolic disease development in young adult female LDLR-deficient mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 468: 116531, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawalec P, Martens MD, Field JT, Mughal W, Caymo AM, Chapman D, Xiang B, Ghavami S, Dolinsky VW, and Gordon JW. Differential impact of doxorubicin dose on cell death and autophagy pathways during acute cardiotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 453: 116210, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duan L, Tang H, Lan Y, Shi H, Pu P, and He Q. Ring finger protein 10 improves pirarubicin-induced cardiac inflammation by regulating the AP-1/Meox2 signaling pathway. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 462: 116411, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu LX, Wang RX, Jiang JF, Yi GC, Chang JJ, He RL, Jiao HX, Zheng B, Gui LX, Lin JJ, Huang ZH, Lin MJ, and Wu ZJ. TRPC6 promotes daunorubicin-induced mitochondrial fission and cell death in rat cardiomyocytes with the involvement of ERK1/2-DRP1 activation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 470: 116547, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elfadadny A, Ragab RF, Hamada R, Al Jaouni SK, Fu J, Mousa SA, and El-Far AH. Natural bioactive compounds-doxorubicin combinations targeting topoisomerase II-alpha: Anticancer efficacy and safety. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 461: 116405, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang H, Weng J, Sun S, Zhou J, Yang Q, Huang X, Sun J, Pan M, Chi J, and Guo H. Ononin alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by activating SIRT3. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 452: 116179, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun Y, Guo D, Yue S, Zhou M, Wang D, Chen F, and Wang L. Afzelin protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by promoting the AMPKalpha/SIRT1 signaling pathway. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 477: 116687, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zidan A, El Saadany AA, El Maghraby GM, Abdin AA, and Hedya SE. Potential cardioprotective and anticancer effects of carvedilol either free or as loaded nanoparticles with or without doxorubicin in solid Ehrlich carcinoma-bearing mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 465: 116448, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang XJ, Li L, Wang AL, Guo HX, Zhao HP, Chi RF, Xu HY, Yang LG, Li B, Qin FZ, and Wang JP. GSK2795039 prevents RIP1-RIP3-MLKL-mediated cardiomyocyte necroptosis in doxorubicin-induced heart failure through inhibition of NADPH oxidase-derived oxidative stress. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 463: 116412, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]