Abstract

Expanded GAA·TTC trinucleotide repeats in intron 1 of the frataxin gene cause Friedreich’s ataxia (FRDA) by reducing frataxin mRNA levels. Insufficient frataxin, a nuclear encoded mitochondrial protein, leads to the progressive neurodegeneration and cardiomyopathy characteristic of FRDA. Previously we demonstrated that long GAA·TTC tracts impede transcription elongation in vitro and provided evidence that the impediment results from an intramolecular purine·purine·pyrimidine DNA triplex formed behind an advancing RNA polymerase. Our model predicts that inhibiting formation of this triplex during transcription will increase successful elongation through GAA·TTC tracts. Here we show that this is the case. Oligodeoxyribonucleotides designed to block particular types of triplex formation provide specific and concentration-dependent increases in full-length transcript. In principle, therapeutic agents that selectively interfere with triplex formation could alleviate the frataxin transcript insufficiency caused by pathogenic FRDA alleles.

INTRODUCTION

Friedreich’s ataxia (FRDA) is the most common inherited ataxia and the first member of the repeat expansion diseases found to be caused by expansion of the trinucleotide repeat GAA·TTC. The expansion occurs within the first intron of the frataxin gene (1). Normal frataxin alleles usually have between 7 and 21 GAA·TTC triplets, while pathogenic alleles contain hundreds to thousands of these triplets (1,2). FRDA is a progressive neurodegenerative disease with associated cardiomyopathy. The disease has a broad clinical spectrum; in the classic case onset of neurological symptoms occurs before puberty, followed by an unrelenting progression until death (3). The length of the GAA·TTC expansion, particularly of the shorter allele, is directly correlated with disease severity (4–6). The expanded repeat reduces expression of frataxin mRNA (7) and protein in patient tissues (8). Frataxin is a nuclear encoded mitochondrial protein involved in iron homeostasis. Its reduction leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, most severely affecting large neurons and heart muscle because of their particularly high energy requirements and absolute dependence on aerobic metabolism (8–11).

Most FRDA patients have intact frataxin coding sequences, so reversing the transcription deficit caused by the expanded GAA·TTC tract is an obvious target for therapeutic intervention. Understanding the biochemical basis of the reduced transcription and developing a readily manipulated system to test conditions that perturb the block are necessary first steps for such an endeavor. Elucidating this mechanism in vitro will provide a basis for understanding the effects of the GAA·TTC expansion in vivo and may suggest possible therapeutic strategies.

The reduction in transcript production by expanded frataxin GAA·TTC tracts has been reproduced in transfected cell lines (12), with nuclear extracts containing human RNA polymerase (RNAP) II in vitro (13) and with purified phage RNAP (13,14). The strand asymmetry of purine (R) and pyrimidine (Y) gives the GAA·TTC sequence the potential to form several types of triplex structures (15,16). Most models proposed to explain the effects of the GAA·TTC tract expansion on transcription invoke one or more variants of these structures (12,13,17,18). We have recently provided evidence for a triplex-based model that differs from these previous models in several important respects.

We proposed that a long GAA·TTC tract impedes elongation by dynamic formation of a transient intramolecular R·R·Y DNA triplex during transcription (14). According to this model, the domain of negative supercoiling, which is known to be generated behind an advancing polymerase (19,20), drives the formation of an intramolecular DNA triplex within an R·Y tract (21,22) because intramolecular triplex formation relaxes negative supercoils (23,24). Opening of the template at the transcription bubble while RNAP is within the GAA·TTC tract initiates triplex formation and the non-template GAA strand folds back to become the third strand in the triplex (Fig. 1A). The model also suggests that an intramolecular Y·R·Y DNA triplex should form in an analogous way when a GAA·TTC tract is transcribed in the opposite direction and TTC is on the non-template strand (14).

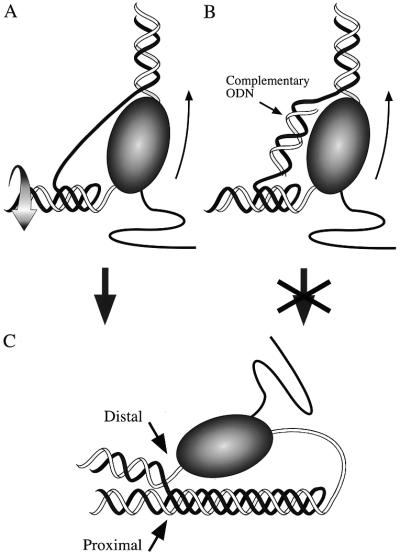

Figure 1.

Rationale for ODN antagonism of transcription-driven intramolecular triplex formation. Ribbon diagrams show two points in transcription-driven triplex formation (A and C) and indicate how ODN hybridization may disrupt it (B). (A) RNAP (shaded oval, thin arrow shows direction of transcription) with an attached nascent transcript (black wavy line) is shown just after nucleation of an intramolecular triplex in the R·Y tract behind it. The curved arrow indicates rotation of the acceptor helix as it winds in the third strand and relaxes negative supercoils. The supercoil energy-driven spread of triplex formation may rapidly progress to the situation shown in (C). (B) As in (A) but with the addition of an ODN able to bind to the non-template strand. Hybridization by the ODN to the expanded transcription bubble (indicated as a short duplex to the left of the RNAP) might prevent the initial fold-back that nucleates triplex formation or stop spread of the triplex by blocking additional winding in by the third strand, as shown here. RNAP continues to transcribe unhindered. (C) Once the non-template strand has been wound into a triplex, the RNAP that initiated formation may be paused at the triplex–duplex junction formed ahead of it at the promoter distal end of the triplex. If the triplex is stable, it may serve to block the next transcribing polymerase, which will encounter the triplex at its promoter proximal end.

Since transcript truncations occur predominantly in the very distal end of the GAA tract, we believe that RNAP has difficulty negotiating the junction between the duplex and triplex regions at the distal end of the structure (14). The absence of stops in the promoter proximal half of the GAA tract indicates either that the proximal duplex–triplex junction does not present much of an obstacle or that the triplex does not last long enough to form a secondary block to subsequent RNAPs (14).

This model predicts that factors that stabilize a transcription-driven triplex will not only exacerbate the negative effect on transcription, but will also increase the frequency of promoter proximal pauses, since a stable triplex can present an additional obstacle to subsequent RNAP at its promoter proximal end (Fig. 1C). Conversely, factors that inhibit triplex formation or stability should increase the amount of transcript produced and lead to a more distal distribution of pauses. In particular, the transcription-driven model predicts that an oligodeoxyribonucleotide (ODN) complementary to the non-template strand should interfere with its participation as a third strand by competitive binding (Fig. 1B).

Here we provide evidence that the presence of an appropriate ODN during transcription through a GAA·TTC tract substantially increases the yield of full-length transcript. In addition, we show that a Y·R·Y triplex does indeed form during transcription in the other direction, that it is relatively stable and that it can produce promoter proximal pauses. If we reduce the stability of this transcription-driven Y·R·Y triplex by including an appropriate ODN or by raising the pH during transcription, a proximal to distal shift in truncations accompanies the increased yield of UUC-RNA. These findings substantiate our model and also have implications for potential therapeutic strategies aimed at alleviating the frataxin transcript deficit in Friedreich’s ataxia patients. Since regions with the potential to influence transcription via the formation of either Y·R·Y or R·R·Y triplexes are widespread in mammalian genomes (25,26), our observations may also prove to be more generally relevant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids

Uninterrupted (CAG·CTG)88 and (GAA·TTC)n repeats were made by a defined stepwise expansion of smaller units cloned into the pREX plasmid (a derivative of pSP72) using asymmetrical type IIS restriction digests, fragment purification and ligation as previously described (27). An HpaI–XhoI fragment, which included the T7 promoter and the triplets, was excised from pREX derivatives containing (CAG·CTG)88 or (GAA·TTC)88 and ligated into XbaI (blunted)- and XhoI-digested pCMV-RiboCOP-250 (Genosys). The RiboCOP plasmids contain a self-cleaving ribozyme sequence which cleaves the RNA transcript 226 bases 3′ to the XhoI recognition sequence. Cleavage is efficient for all inserts tested (14). Plasmids were prepared using a modified alkaline lysis procedure (28). Long GAA·TTC inserts are unstable in bacteria (27), so some templates were gel purified to enrich for full-length inserts.

Oligodeoxyribonucleotides

The ODNs (GAA)7, (TTC)7, (CAG)7 and (CTG)7 were synthesized using standard phosphoramidite chemistry by Life Technologies (Rockville, MD).

Agarose gel electrophoresis

Electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels was performed in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris–acetate, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). Where noted, this buffer was adjusted to pH 7.0 or 6.0 with acetic acid. For ODN retention studies supercoiled templates were suspended in 1.1× T7 transcription buffer (lacking enzymes) at pH 8.0 or 7.0 and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. A 1/10 vol of TE or 10 µM ODN was added, mixed well and incubated for 20 min at 37°C. A 2-fold v/v aliquot of a loading buffer designed to chelate magnesium and neutralize pH differences (100 mM Tris pH 8.8, 10 mM EDTA, 15% v/v glycerol and 0.05% each bromophenol blue and xylene cyanol) was added to each sample. The samples were resolved on a 1% agarose gel with TAE pH 8.0, as running buffer. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide after electrophoresis.

In vitro transcription

RNA transcription from phage promoters was performed in T7 transcription buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT and 0.5 mM each NTP) supplemented with 200 U/ml RNase inhibitor (Ambion) in a final volume of 20 µl at 37°C for 20 min. T7 RNAP (Ambion) was used at a final concentration of 1000 U/ml. Template concentrations (usually ∼200 ng/reaction) were estimated by ethidium bromide fluorescence. The 5′-end of the transcript was labeled by including [γ-32P]GTP (6000 Ci/mmol; NEN Life Science Products). The γ-phosphate is retained only in the first position.

To set up reactions, master mixes of components were added together sequentially. For the various ODN experiments templates were first brought to 1.1× with T7 buffer lacking enzymes, then mixed with a 1/10 vol of TE or ODNs and incubated at 37°C for 5 min. A pre-warmed aliquot of complete buffer with RNAP was then added. For the pH experiments a pre-warmed cocktail containing NTPs, [γ-32P]GTP, DTT, RNase inhibitor and RNAP was mixed with templates. These were then split into pre-warmed tubes containing the remaining T7 transcription buffer components (NaCl, MgCl2 and HEPES, pH 9.0, 8.0 or 7.0) and incubated for 20 min at 37°C.

Transcript analysis

Radiolabeled reactions were stopped with 130 ml of stop buffer (96% deionized formamide, 10 mM EDTA and 10 µg/ml tRNA). The samples were precipitated with ethanol, resuspended in denaturing gel loading buffer (96% formamide, 10 mM EDTA and 0.05% each bromophenol blue and xylene cyanol) heated to 90°C and loaded on a prewarmed 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gel containing 8 M urea. An MspI digest of pBR322 (New England Biolabs) was used as a size marker. Images of radioactive gels were obtained using FujiFilm BAS III-S phosphorimaging screens and a FujiFilm BAS 1500 reader. Analysis and quantitation was performed with FujiFilm Image Gauge 3.3 (Mac) software.

RESULTS

ODNs designed to inhibit triplex formation increase transcript yield from GAA·TTC templates

Our model proposes that when RNAP transcribes a long GAA·TTC tract, part of the non-template GAA strand can fold back behind the polymerase to bind the flanking GAA·TTC duplex and become the third strand in an R·R·Y triplex (Fig. 1A). Competition for the non-template strand by a complementary ODN should inhibit triplex formation (Fig. 1B). Transcription in the presence of such an ODN should therefore produce more full-length transcript.

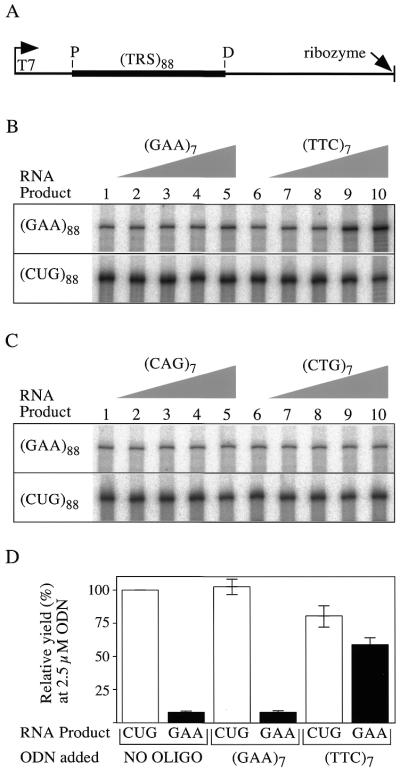

To examine this idea, we transcribed templates containing variations of the cassette shown in Figure 2A in the presence of several ODNs. The templates had 88 repeats of GAA, or CTG on the non-template strand of the triplet repeat sequence (TRS) and generated (GAA)88-containing RNA (GAA-RNA) and (CUG)88-containing RNA (CUG-RNA), respectively. The ODNs tested were (TTC)7, (GAA)7, (CAG)7 and (CTG)7. The effects that these ODNs had on production of full-length transcripts from the test templates are shown in Figure 2B and C.

Figure 2.

Specific reversal of inhibition of full-length GAA-RNA synthesis by (TTC)7. (A) Schematic of the transcription cassette contained in the supercoiled templates used in this work. An arrow on the left designates the T7 promoter. Only the first base in the transcript (a G) retains the γ-phosphate, so [γ-32P]GTP end-labels transcription products. The promoter proximal (P) and promoter distal (D) ends of the TRS are indicated. A self-cleaving ribozyme sequence (right end) determines the 3′-end of ‘full-length’ transcripts, which for (TRS)88 is 590 bases. (B and C) The full-length RNA products containing the TRS indicated to the left from transcription at pH 8 in the presence of various concentrations of the indicated ODNs. Lanes 1 and 6, no ODN; lanes 2 and 7, 10 nM; lanes 3 and 8, 100 nM; lanes 4 and 9, 1 µM; lanes 5 and 10, 10 µM. (D) The bar graph shows the levels of full-length (GAA)88 transcript synthesis (black bar) relative to the (CUG)88 control (first white bar defined as 100%). Transcription was at pH 8 (n = 4).

For generation of GAA-RNA the ODN complementary to the non-template strand, i.e. (TTC)7, increased the yield of full-length transcript when present at concentrations of 1 µM or above (Fig. 2B, lanes 9 and 10). The (GAA)7 ODN had no effect on the yield of GAA-RNA (Fig. 2B, lanes 1–5). Neither ODN had a specific effect on transcription of a template with CTG repeats as the non-template strand. Moreover, neither (CAG)7 nor (CTG)7 altered transcription of either template (Fig. 2C). Since (CAG)7 is complementary to the non-template strand of the plasmid directing synthesis of CUG-RNA, transcriptional enhancement is not a general property of ODNs complementary to the non-template strand.

At high concentrations (TTC)7 acted as a non-specific template for T7 RNAP and produced a ladder of products (Fig. 2B, lane 10). This caused a general reduction in the yield of CUG-RNA and limited the increase obtained for GAA-RNA. Further titration within the micromolar range (not shown) indicated that the peak effective concentration for (TTC)7 was 2–3 µM. We quantified the full-length products generated from four independent experiments using an ODN concentration of 2.5 µM and expressed the values graphically as percent relative to the CUG control without added ODNs (Fig. 2D).

In the absence of added ODNs the amount of full-length GAA-RNA was only 8.5% that of the CUG-RNA control. The presence of 2.5 µM (GAA)7 did not alter this ratio. However, the addition of 2.5 µM (TTC)7 increased the yield of full-length GAA-RNA substantially, so that it averaged ∼75% of the matched CUG-RNA control (Fig. 2D, last 2 bars).

A Y·R·Y triplex reduces UUC-RNA yield from a GAA·TTC tract transcribed in the reverse orientation

According to our model, transcription in the opposite direction through a GAA·TTC tract will result in formation of a Y·R·Y triplex. If this is so, then the (GAA)7 ODN, which had no effect on GAA-RNA synthesis, should improve full-length UUC-RNA yields. To test this, a template with the (GAA·TTC)88 TRS in the reverse orientation was transcribed in the presence of the test ODNs. The effects that the (GAA)7 and (TTC)7 ODNs had on the production of UUC-RNA are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Transcription in the opposite direction through GAA·TTC is rescued by (GAA)7. The full-length RNA products containing (UUC)88 from transcription at pH 8 in the presence of the indicated ODNs. Lanes 1 and 6, no ODN; lanes 2 and 7, 10 nM; lanes 3 and 8, 100 nM; lanes 4 and 9, 1 µM; lanes 5 and 10, 10 µM.

As predicted, the presence of the (GAA)7 ODN produced a concentration-dependent increase in the yield of UUC-RNA, suggesting that it competitively inhibited formation of a Y·R·Y triplex. Like the other templates, neither (CAG)7 nor (CTG)7 had any effect (not shown). However, in contrast to transcription to synthesize GAA-RNA, the presence of the ODN complementary to the template strand, rather than having no effect, actually decreased UUC-RNA levels (Fig. 3, lanes 9 and 10). The (TTC)7 ODN reduced UUC-RNA accumulation beyond the general reduction shown by the CUG-RNA control (compare to Fig. 2B), suggesting a specific repressive effect on UUC-RNA transcription.

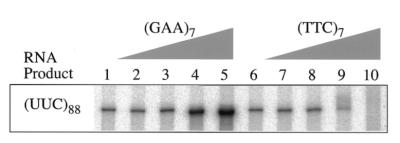

It is possible that the (TTC)7 ODN decreased UUC-RNA yield by forming an intermolecular triplex with the template. However, given the short length of the ODN, intermolecular structures are likely to be too unstable to block RNAP. An alternative possibility is that intramolecular Y·R·Y triplexes form spontaneously on these supercoiled templates and that (TTC)7 then stabilizes these triplexes by binding to GAA regions left single stranded (29), as shown in Figure 4A.

Figure 4.

Specific uptake of (TTC)7 by long GAA·TTC tracts in transcription buffer at neutral pH. (A) (Left) The ribbon diagram of an intramolecular triplex shows that unwinding of the third strand from its original duplex and its winding into the neighboring R·Y region as a third strand both provide turns (indicated by curved arrows) that relax negative supercoils in the flanking DNA. (Right) Once formed, an intramolecular triplex leaves part of the complement to the third strand single stranded and available to bind an ODN. The examples shown depict a Y·R·Y triplex. The purine (R) strand is dark; the pyrimidine (Y) strand is light. (B) Supercoiled templates bearing 0, 11, 44 or 88 GAA·TTC triplets were incubated in transcription buffer at pH 8.0 or 7.0 in the presence of 1 µM (GAA)7 or (TTC)7 for 20 min at 37°C in the combinations indicated. A loading buffer designed to neutralize pH differences was added to each sample. The samples were resolved on a 1% agarose gel with TAE, pH 8.0, as running buffer. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide after electrophoresis. The number of triplets contained in the plasmid is indicated above the lanes. Lane M is a 1 kb DNA ladder showing bands of 1636, 2036 and 3054 bp, respectively. (C) Supercoiled templates bearing 0, 11, 44 or 88 GAA·TTC triplets were subjected to electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel with TAE as the running buffer, at pH 8.0, 7.0 or 6.0. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide after electrophoresis. Lane M is a 1 kb DNA ladder showing bands of 1018, 1636, 2036 and 3054 bp, respectively.

To evaluate the potential contributions of pre-existing R·R·Y or Y·R·Y structures during transcription we used (GAA)7 or (TTC)7 ODNs as specific probes for the single strands generated by each structure. In a GAA·TTC tract formation of an intramolecular R·R·Y structure leaves part of the TTC strand unpaired and available to bind the (GAA)7 ODN. An intramolecular Y·R·Y structure, on the other hand, leaves part of the GAA strand unpaired and available to hybridize to (TTC)7. The stability of a Y·R·Y triplex is enhanced by low pH, because third strand cytosines must be protonated to pair with the central G of a C·G·C triplet (15). Consequently, we could enhance the likelihood of Y·R·Y formation by incubation at a lower pH. While R·R·Y triplex formation is pH independent, it does require divalent cations such as magnesium (16), which is a component of the transcription buffer. We therefore incubated supercoiled plasmids in transcription buffer at pH 8.0 or 7.0 with either (GAA)7 or (TTC)7. After the incubation period all samples were adjusted to pH 8.8 and EDTA was added to destabilize untrapped triplexes of either type. Retention of the ODN, which causes a decreased gel mobility, was monitored by subsequent electrophoresis of the plasmids in an agarose gel at pH 8.0.

The left side of Figure 4B shows the mobility of supercoiled plasmids with the indicated number of GAA·TTC triplets after incubation with (GAA)7 in transcription buffer at pH 8.0 or 7.0. All plasmids had the same mobility as they did when subject to electrophoresis at pH 8.0 without prior incubation with an ODN (Fig. 4C). The lack of (GAA)7 uptake indicates that very few of the templates spontaneously adopt the R·R·Y structure at either pH.

The right half of Figure 4B shows that an altered gel mobility is seen after preincubation with the (TTC)7 ODN, but only for plasmids bearing 44 or 88 GAA·TTC triplets. When incubated in transcription buffer at pH 8.0 before electrophoresis there is a small amount of (TTC)7 uptake. This is visible as a decrease in the intensity of the major supercoiled band and a smear above it in the lanes containing the (GAA·TTC)44 and (GAA·TTC)88 plasmids. The uptake of (TTC)7 during incubation in transcription buffer at pH 7.0 is more significant, as indicated by the amount of material with a retarded mobility seen in the last two lanes. The (GAA·TTC)11 plasmid and the control plasmid did not take up either ODN at either pH of incubation. Lack of (TTC)7 uptake by the (GAA·TTC)11 plasmid indicates that the uptake seen for the 44 and 88 triplets was not simply due to invasion of the ODN into a complementary region of a supercoiled plasmid or to binding as the third strand of an intermolecular triplex.

The extent of ODN uptake by plasmids with 44 or 88 GAA·TTC triplets indicates that a large proportion of these plasmids spontaneously form the Y·R·Y structure in transcription buffer at neutral pH. (TTC)7 uptake could indicate a stable Y·R·Y triplex or it could be due to kinetic trapping of an unstable short-lived triplex by the ODN (29). To distinguish between these possibilities we subjected templates to electrophoresis at various pH values. Formation of an intramolecular triplex relaxes negative supercoils, as illustrated in Figure 4A, left, and its continued presence during electrophoresis will alter the mobility of a supercoiled plasmid (23,24).

Figure 4C shows that all templates migrate as a single band consistent with normal bacterial superhelical density when electrophoresis is performed at pH 8.0. However, at pH 7.0 ∼50% of the (GAA·TTC)44 and (GAA·TTC)88 plasmids migrate between the positions of fully supercoiled and fully relaxed molecules. This is compatible with formation of a long-lived Y·R·Y triplex that relaxes only some supercoils or oscillation between fully relaxed and fully supercoiled states.

Electrophoresis at pH 6.0 causes most of the (GAA·TTC)44 and (GAA·TTC)88 plasmid molecules to migrate as if completely relaxed, consistent with formation of a more stable intramolecular Y·R·Y triplex that removes a larger number of superhelical turns. In contrast, the supercoiled templates with 0 or 11 GAA·TTC triplets migrate as discrete bands with the expected mobility at all three pH values. The proportion of molecules showing a mobility shift at pH 7.0 indicates that a large fraction of the (GAA·TTC)44 and (GAA·TTC)88 plasmids with normal bacterial superhelical densities form stable Y·R·Y triplexes at neutral pH.

Relative triplex stability determines both RNA yield and the distribution of truncations

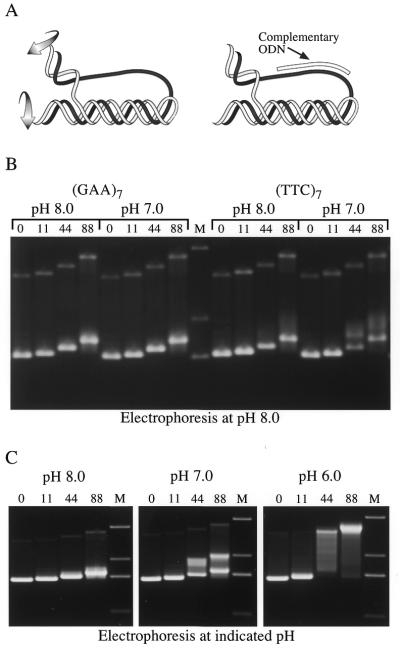

Although we lack a means to selectively stabilize the R·R·Y triplex, the spontaneous formation of a stable Y·R·Y triplex at neutral pH in the absence of transcription suggested that evidence of promoter proximal RNAP pauses might be observed in UUC-RNA products if transcription was performed at pH 7.0. Our model predicts that pause sites should become more distal at higher pH, when the Y·R·Y structure is weakened and its formation is thus more dependent on the wave of negative supercoiling generated behind RNAP (Fig. 1C). To test these predictions we transcribed templates in reactions that differed only in the pH of the buffer. The pH range chosen was approximately ±1 pH unit from pH 7.9, the optimum for T7 RNAP activity. Figure 5 shows the end-labeled RNA products produced from supercoiled templates transcribed at pH 9.0 (lanes 1–3), 8.0 (lanes 4–6) and 7.0 (lanes 7–9).

Figure 5.

Relative triplex strength determines polymerase pause sites. The gel image shows the products of transcription at the indicated pH from supercoiled templates producing an RNA with the (TRS)88 indicated above each lane. The large black arrow to the left points to the full-length product. The gray bracket immediately below full-length indicates short products that come from deletions present within the TRS in the templates. The black bracket indicates the location of the triplets in the transcript. The TRS in the GAA-RNA is slightly offset from the other two; it starts at base 55, the others at base 67 in the transcripts. Small black arrowheads point to specific truncated products in the distal end of the TRS; hollow arrowheads denote their absence. The numbers to the right indicate the size in bases of selected bands of an MspI digest of pBR322. To the right of the gel image and aligned with it are scans of the TRS portion of lanes 2, 3 and 8. The arrows at the top indicate the lane scanned and highlight the relative peaks at the end of the TRS.

The yield of CUG-RNA from the control template showed little difference at these pH values (Fig. 5, lanes 1, 4 and 7). Production of full-length GAA-RNA remained well below the levels of the control at all pH values (lanes 3, 6 and 9). A characteristic pattern of truncations within the distal end of the tract was similar at all three pH values (small arrowheads, lanes 3, 6 and 9). The yield of full-length GAA-RNA increased slightly with decreasing pH, but the increase was usually less than 2-fold across this pH range.

While GAA-RNA levels did not decrease as the pH was lowered, the yield of full-length UUC-RNA showed a steep decline (Fig. 5, lanes 2, 5 and 8). When transcribed at pH 9.0 the yield of full-length UUC-RNA is similar to the control (lanes 1 and 2). The pattern of truncations within the UUC tract at this pH resembles that of the GAA tract (Fig. 5, lanes 2 and 3 in gel and scan), including a small peak at the distal end of the repeat (small arrowhead in lanes 2 and 3 and scan). When transcribed at pH 8.0 (lane 5) the yield of full-length UUC-RNA is reduced, truncations in the distal part of the repeat are less prominent and the truncations have a generally more promoter proximal distribution. Very little full-length UUC-RNA is produced at pH 7.0 (lane 8) and the major truncation points are clustered within the proximal triplets (Fig. 5, scan of lane 8), suggesting a relatively stable proximal impediment to transcription.

ODNs that increase yield change the distribution of truncated transcripts

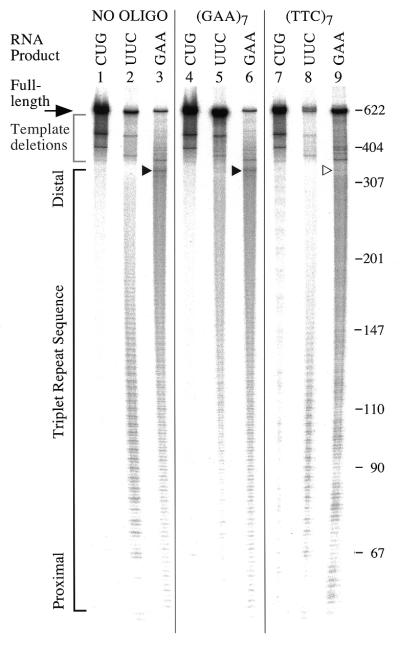

If an ODN increases the yield of full-length RNA by inhibiting triplex formation as we suggest, a change in the distribution of pauses within the repeat should also occur. For UUC-RNA we would predict that the change in the distribution of pauses due to the ODN might resemble the shift to distal truncations seen when the Y·R·Y structure is destabilized by alkaline conditions during transcription at pH 9.0. In the case of GAA-RNA, which has only distal pauses to begin with, we might expect a decrease in some or all of these truncations. To test this, we performed transcription reactions (all at pH 8.0) in the presence of either (GAA)7 or (TTC)7 and examined the pattern of truncated products as well as the yield of full-length RNA. The gel image in Figure 6 shows that specific changes in the pattern of truncations within the GAA·TTC tract accompany an ODN-mediated increase in full-length transcript.

Figure 6.

ODNs effective in enhancing transcription produce specific changes in truncations. The gel image shows the products of transcription, in the presence of the ODNs indicated at the top, from supercoiled templates producing an RNA with the (TRS)88 indicated above each lane. The large black arrow to the left points to the full-length product. The gray bracket immediately below the arrow indicates short products from deletions present within the TRS in the templates. The black bracket indicates the location of the triplets in the transcript. The GAA tract starts at base 55, the others at base 67 in the transcripts. Small black arrowheads point to bands in the distal part of the GAA tract in lanes 3 and 6. A hollow arrowhead highlights the absence of the distal bands in lane 9. The numbers to the right indicate the size in bases of selected bands of an MspI digest of pBR322. The ODN concentration was 2.5 µM, when present. The (TTC)7 ODN produced a ladder of products that can be seen in lane 7 and is superimposed on the truncations present in lanes 8 and 9.

The distribution of truncated UUC-RNA in the absence of ODN and the presence of (TTC)7 were similar (lanes 2 and 8). However, the pattern of truncations for UUC-RNA in the presence of (GAA)7 shown in lane 5 is different. Both the yield of full-length UUC-RNA and the distal distribution of truncations more closely resemble that of UUC-RNA transcription at pH 9.0 (compare to Fig. 5, lane 2).

The characteristic pattern of truncations within the GAA-RNA repeat tract which culminate in a peak at the distal end of the tract was similar in the absence of ODN and in the presence of (GAA)7 (small arrowheads, lanes 3 and 6). The (TTC)7-mediated increase in GAA-RNA is accompanied by a reduction in truncations at the distal end of the GAA tract (indicated by a hollow arrowhead in Fig. 6, lane 9). This distal location appears to be the most significant R·R·Y triplex-mediated RNAP pause site on these templates and the apparently small decrease in truncated material here translates to a large increase in full-length GAA-RNA production.

DISCUSSION

Our model posits that R·R·Y triplex formation during transcription causes the deficit in full-length transcripts when GAA-containing RNA is being synthesized from a long GAA·TTC tract, as is the case in FRDA. We also propose that if the GAA·TTC tract is transcribed in the opposite direction that Y·R·Y triplexes cause a deficit in UUC-containing RNA production. In either case, conditions that favor the transcription-driven triplex exacerbate the impediment, while conditions inhibitory to formation of the triplex increase the yield of full-length transcripts. Moreover, agents that selectively modulate the stability of only the R·R·Y or only the Y·R·Y form selectively alter the accumulation of full-length GAA-RNA or UUC-RNA, respectively.

Accordingly, the presence of a (TTC)7 ODN during transcription, which should inhibit transcription-dependent formation of the R·R·Y triplex, specifically increases the yield of GAA-RNA. In contrast, the presence of a (GAA)7 ODN, which should not interfere with transcription-driven R·R·Y formation, has little or no effect on the yield of this transcript. When the GAA·TTC tract is transcribed in the opposite orientation and the transcription-driven triplex is predicted to be of the Y·R·Y form, the effective oligonucleotide is reversed. Here the (GAA)7 ODN but not the (TTC)7 ODN increases the yield of UUC-RNA levels, as predicted. In this case the (TTC)7 ODN actually inhibited UUC-RNA accumulation, perhaps via a stabilizing effect on pre-existing Y·R·Y triplexes.

Furthermore, altering the stability of Y·R·Y triplexes by transcribing templates at different pH values selectively altered the yield of full-length UUC-RNA. An increase in full-length UUC-RNA and a shift to distal pauses in the TRS, both of which are consistent with a weak and transient triplex, was seen for transcription reactions performed at pH 9.0. That the (GAA)7 ODN produces a similar increase in yield and distribution of truncations with this template suggests that both treatments exert their effects via a common mechanism, namely by destabilizing the Y·R·Y triplex. On the other hand, transcription at pH 7.0 reduced the production of full-length UUC-RNA and increased pausing at promoter proximal sites relative to transcription at pH 9.0. These effects are consistent with the known stabilization of Y·R·Y structures at reduced pH.

Our demonstration of spontaneous formation of stable Y·R·Y intramolecular triplexes at neutral pH by GAA·TTC tracts is significant for a number of reasons. While it has previously been shown using ODNs that the Y·R·Y triplex can form at neutral pH when the constituent strands of the triplex are already unpaired (30,31), our data demonstrate for the first time that spontaneous triplex formation by GAA·TTC tracts from otherwise duplex molecules occurs to a significant degree under physiologically reasonable conditions. This supports the idea that long GAA·TTC tracts may spontaneously adopt such structures in vivo. This may affect the properties of regions containing them in a number of ways, influencing not only transcription, but perhaps DNA replication and chromatin structure as well.

Although the electrophoretic assays for triplex formation (Fig. 4) show that a large proportion of the templates contain a pre-existing Y·R·Y triplex at neutral pH, this does not adversely affect synthesis of GAA-RNA. In contrast to the decreased full-length UUC-RNA yield from transcription of the GAA·TTC tract in the opposite orientation at pH 7.0 there is, if anything, more GAA-RNA produced at this pH than at pH 8.0. This supports our original contention that the Y·R·Y triplex is not responsible for the deficit in GAA-RNA (14). Furthermore, it indicates that the (TTC)7 ODN most likely increases GAA-RNA yields by inhibiting R·R·Y formation, not by its additional property of stabilizing spontaneously formed Y·R·Y structures. While it could be argued that the ODN complementary to the non-template strand acts by interfering with other structures, most of those proposed (12,13,17,18) are inconsistent with our observation that the majority of the truncated GAA transcripts terminate at the distal end of the GAA·TTC tract. One hypothetical structure, a so-called ‘collapsed R-loop’ (32), in which a purine non-template strand collapses onto a RNA·DNA hybrid formed within an R·Y tract, has been suggested to cause RNAP pausing in the distal end of a (G·C)32 tract (33). Our model does predict that an RNA·DNA hybrid could form subsequent to triplex formation. However, while we do have evidence that this occurs, we have no evidence to suggest that the R-loop collapses.

In any case, the efficacy of this ODN approach in vitro suggests potential as a therapy for treating FRDA patients. Unmodified ODNs such as used here may have limited utility in vivo since relatively high concentrations are required and degradation could be a problem. Peptide–nucleic acids (PNAs), which bind to DNA with much higher affinity than unmodified ODNs and are resistant to nucleases (34), may be effective at far lower concentrations. The ODNs beneficial to transcription are in fact ‘antisense’ and therefore have the potential to cause RNase H-mediated transcript degradation. However, since PNAs do not induce RNase H cleavage of RNA·PNA hybrids, their use should also eliminate this potential drawback (35).

The ready uptake of the (TTC)7 ODN by GAA·TTC tracts suggests a more lasting therapeutic strategy. The use of oligonucleotides to generate targeted point mutations shows promise in reversing disease-causing point mutations (36). Formation of either a stable D-loop or a triplex by the oligonucleotide appears to be an important intermediate in this process (37,38). Long GAA·TTC tracts might therefore be particularly amenable to the introduction of mutations in this way. The large target provided by these tracts would present multiple opportunities for mutagenic oligonucleotides to anneal. The introduction of a small number of point mutations in a previously pathogenic FRDA allele might significantly reduce the likelihood of triplex formation, thereby alleviating the transcriptional defect without the need for continuous treatment.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Anthony V. Furano, Debbie Hinton and Nancy Nossal for their critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Campuzano V., Montermini,L., Molto,M.D., Pianese,L., Cossee,M., Cavalcanti,F., Monros,E., Rodius,F., Duclos,F., Monticelli,A. et al. (1996) Friedreich’s ataxia: autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science, 271, 1423–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cossee M., Schmitt,M., Campuzano,V., Reutenauer,L., Moutou,C., Mandel,J.L. and Koenig,M. (1997) Evolution of the Friedreich’s ataxia trinucleotide repeat expansion: founder effect and premutations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 7452–7457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harding A.E. (1981) Friedreich’s ataxia: a clinical and genetic study of 90 families with an analysis of early diagnostic criteria and intrafamilial clustering of clinical features. Brain, 104, 589–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durr A., Cossee,M., Agid,Y., Campuzano,V., Mignard,C., Penet,C., Mandel,J.L., Brice,A. and Koenig,M. (1996) Clinical and genetic abnormalities in patients with Friedreich’s ataxia. N. Engl. J. Med., 335, 1169–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filla A., De Michele,G., Cavalcanti,F., Pianese,L., Monticelli,A., Campanella,G. and Cocozza,S. (1996) The relationship between trinucleotide (GAA) repeat length and clinical features in Friedreich ataxia. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 59, 554–560. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montermini L., Richter,A., Morgan,K., Justice,C.M., Julien,D., Castellotti,B., Mercier,J., Poirier,J., Capozzoli,F., Bouchard,J.P., Lemieux,B., Mathieu,J., Vanasse,M., Seni,M.H., Graham,G., Andermann,F., Andermann,E., Melancon,S.B., Keats,B.J., Di Donato,S. and Pandolfo,M. (1997) Phenotypic variability in Friedreich ataxia: role of the associated GAA triplet repeat expansion. Ann. Neurol., 41, 675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cossee M., Campuzano,V., Koutnikova,H., Fischbeck,K., Mandel,J.L., Koenig,M., Bidichandani,S.I., Patel,P.I., Molte,M.D., Canizares,J., De Frutos,R., Pianese,L., Cavalcanti,F., Monticelli,A., Cocozza,S., Montermini,L. and Pandolfo,M. (1997) Frataxin fracas. Nature Genet., 15, 337–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campuzano V., Montermini,L., Lutz,Y., Cova,L., Hindelang,C., Jiralerspong,S., Trottier,Y., Kish,S.J., Faucheux,B., Trouillas,P., Authier,F.J., Durr,A., Mandel,J.L., Vescovi,A., Pandolfo,M. and Koenig,M. (1997) Frataxin is reduced in Friedreich ataxia patients and is associated with mitochondrial membranes. Hum. Mol. Genet., 6, 1771–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson T.J., Koonin,E.V., Musco,G., Pastore,A. and Bork,P. (1996) Friedreich’s ataxia protein: phylogenetic evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction. Trends Neurosci., 19, 465–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babcock M., de Silva,D., Oaks,R., Davis-Kaplan,S., Jiralerspong,S., Montermini,L., Pandolfo,M. and Kaplan,J. (1997) Regulation of mitochondrial iron accumulation by Yfh1p, a putative homolog of frataxin. Science, 276, 1709–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rotig A., de Lonlay,P., Chretien,D., Foury,F., Koenig,M., Sidi,D., Munnich,A. and Rustin,P. (1997) Aconitase and mitochondrial iron-sulphur protein deficiency in Friedreich ataxia. Nature Genet., 17, 215–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohshima K., Montermini,L., Wells,R.D. and Pandolfo,M. (1998) Inhibitory effects of expanded GAA.TTC triplet repeats from intron I of the Friedreich ataxia gene on transcription and replication in vivo. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 14588–14595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bidichandani S.I., Ashizawa,T. and Patel,P.I. (1998) The GAA triplet-repeat expansion in Friedreich ataxia interferes with transcription and may be associated with an unusual DNA structure. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 62, 111–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grabczyk E. and Usdin,K. (2000) The GAA·TTC triplet repeat expanded in Friedreich’s ataxia impedes transcription elongation by T7 RNA polymerase in a length and supercoil dependent manner. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 2815–2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells R.D., Collier,D.A., Hanvey,J.C., Shimizu,M. and Wohlrab,F. (1988) The chemistry and biology of unusual DNA structures adopted by oligopurine.oligopyrimidine sequences. FASEB J., 2, 2939–2949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohwi Y. and Kohwi-Shigematsu,T. (1988) Magnesium ion-dependent triple-helix structure formed by homopurine-homopyrimidine sequences in supercoiled plasmid DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 3781–3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohshima K., Kang,S., Larson,J.E. and Wells,R.D. (1996) Cloning, characterization and properties of seven triplet repeat DNA sequences. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 16773–16783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakamoto N., Chastain,P.D., Parniewski,P., Ohshima,K., Pandolfo,M., Griffith,J.D. and Wells,R.D. (1999) Sticky DNA: self-association properties of long GAA.TTC repeats in R.R.Y triplex structures from Friedreich’s ataxia. Mol. Cell, 3, 465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu L.F. and Wang,J.C. (1987) Supercoiling of the DNA template during transcription. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 84, 7024–7027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu H.Y., Shyy,S.H., Wang,J.C. and Liu,L.F. (1988) Transcription generates positively and negatively supercoiled domains in the template. Cell, 53, 433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reaban M.E. and Griffin,J.A. (1990) Induction of RNA-stabilized DNA conformers by transcription of an immunoglobulin switch region. Nature, 348, 342–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grabczyk E. and Fishman,M.C. (1995) A long purine-pyrimidine homopolymer acts as a transcriptional diode. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 1791–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Htun H. and Dahlberg,J.E. (1988) Single strands, triple strands and kinks in H-DNA. Science, 241, 1791–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Htun H. and Dahlberg,J.E. (1989) Topology and formation of triple-stranded H-DNA. Science, 243, 1571–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manor H., Rao,B.S. and Martin,R.G. (1988) Abundance and degree of dispersion of genomic d(GA)n.d(TC)n sequences. J. Mol. Evol., 27, 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tripathi J. and Brahmachari,S.K. (1991) Distribution of simple repetitive (TG/CA)n and (CT/AG)n sequences in human and rodent genomes. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 9, 387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grabczyk E. and Usdin,K. (1999) Generation of microgram quantities of trinucleotide repeat tracts of defined length, interspersion pattern and orientation. Anal. Biochem., 267, 241–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baumann C.G. and Bloomfield,V.A. (1995) Large-scale purification of plasmid DNA for biophysical and molecular biology studies. Biotechniques, 19, 884–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belotserkovskii B.P., Krasilnikova,M.M., Veselkov,A.G. and Frank-Kamenetskii,M.D. (1992) Kinetic trapping of H-DNA by oligonucleotide binding. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 1903–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gacy A.M., Goellner,G.M., Spiro,C., Chen,X., Gupta,G., Bradbury,E.M., Dyer,R.B., Mikesell,M.J., Yao,J.Z., Johnson,A.J., Richter,A., Melancon,S.B. and McMurray,C.T. (1998) GAA instability in Friedreich’s Ataxia shares a common, DNA-directed and intraallelic mechanism with other trinucleotide diseases. Mol. Cell, 1, 583–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mariappan S.V., Catasti,P., Silks,L.A., Bradbury,E.M. and Gupta,G. (1999) The high-resolution structure of the triplex formed by the GAA/TTC triplet repeat associated with Friedreich’s ataxia. J. Mol. Biol., 285, 2035–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reaban M.E., Lebowitz,J. and Griffin,J.A. (1994) Transcription induces the formation of a stable RNA.DNA hybrid in the immunoglobulin alpha switch region. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 21850–21857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krasilnikova M.M., Samadashwily,G.M., Krasilnikov,A.S. and Mirkin,S.M. (1998) Transcription through a simple DNA repeat blocks replication elongation. EMBO J., 17, 5095–5102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ray A. and Norden,B. (2000) Peptide nucleic acid (PNA): its medical and biotechnical applications and promise for the future. FASEB J., 14, 1041–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knudsen H. and Nielsen,P.E. (1996) Antisense properties of duplex- and triplex-forming PNAs. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 494–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cole-Strauss A., Yoon,K., Xiang,Y., Byrne,B.C., Rice,M.C., Gryn,J., Holloman,W.K. and Kmiec,E.B. (1996) Correction of the mutation responsible for sickle cell anemia by an RNA-DNA oligonucleotide. Science, 273, 1386–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan P.P., Lin,M., Faruqi,A.F., Powell,J., Seidman,M.M. and Glazer,P.M. (1999) Targeted correction of an episomal gene in mammalian cells by a short DNA fragment tethered to a triplex-forming oligonucleotide. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 11541–11548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gamper H.B. Jr, Cole-Strauss,A., Metz,R., Parekh,H., Kumar,R. and Kmiec,E.B. (2000) A plausible mechanism for gene correction by chimeric oligonucleotides. Biochemistry, 39, 5808–5816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]