Abstract

Many molecular mechanisms underlying blood glucose homeostasis remain elusive. Juan-Mateu et al. find that pancreatic islet cells utilize a regulatory program involving the alternative splicing of microexons in genes important for insulin secretion or diabetes risk. This regulatory program was originally identified in neurons.

When the first draft of the reference human genome was released in 2001, there was surprise that the number of protein-coding genes in the human genome was similar to those of seemingly less-complex species (1). Since then, it has become clear that post-transcriptional (2) and post-translational (3) gene regulation allows for increased complexity, such that one gene can encode for many different protein products. Alternative splicing is one such essential regulatory mechanism that affects over 95% of human multi-exonic genes (4) and can be regulated in tissue- and cell-specific manners (5). Misregulation of alternative splicing has been found in some human diseases and has the potential to be targeted therapeutically (6). In recent years, genome-wide association studies have revealed that variants in regulatory elements that influence gene expression in pancreatic islet cells can alter risk for diabetes. However, the roles of alternative splicing in pancreatic islet function are not yet fully understood (7).

Microexons are short exons (3 to 27 nucleotides long) involved in tissue-enriched alternative splicing and are highly conserved in neurons (8). They add one or more amino acids into the protein surface while maintaining the open reading frame, often affecting protein–protein interactions (8). Their regulation is mediated by the RNA-binding proteins SRRM3 and SRRM4, which are necessary and sufficient for microexon splicing (9).

A new study by Juan-Mateu et al. now sheds light on post-transcriptional regulation of glucose homeostasis by identifying this conserved neural mechanism in islets and exploring its impact on islet cell development (10). Through analysis of publicly available data, they found an enrichment of microexons in pancreatic islets, which they term islet microexons or IsletMICs, and that islets have the highest ratio of enriched microexons to enriched long exons across all human tissues. Further analysis by the authors revealed that IsletMICs are overrepresented in genes involved in insulin secretion and genes associated with altered risk for type 2 diabetes.

From publicly available data, they found that 97.3% of IsletMICs overlap with microexons that are highly included in neural cells, suggesting that they comprise a subprogram of the neural microexon mechanism. To determine whether IsletMICs are regulated in the same manner as neural microexons, they investigated the functions of the SRRM RNA-binding proteins in islets. They found that SRRM3, but not SRRM4, is present in islets, although at a lower level than neurons, and that SRRM3 is specifically necessary for IsletMIC inclusion in vitro in human EndoC-βH1 and rat INS-1E beta cell lines. To explore why IsletMICs are included in pancreatic cells despite lower SRRM expression, they used a doxycycline-inducible system to exogenously express SRRM3 in HeLa cells and found that, while most IsletMICs were more frequently included at low SRRM3 expression levels, most of the neural-only microexons were only included under higher SRRM3 levels. This suggests that IsletMICs correspond to the subset of neuronal microexons with high sensitivity to SRRM3.

To identify the functional role of alternative microexon splicing in pancreatic islets, the authors explored the impact of perturbation to this mechanism in human EndoC-βH1 and rat INS-1E beta cell lines. They found that depletion of SRRM3 leads to increased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, and that exclusion of some IsletMICs results in inappropriate secretion of insulin. In rat INS-1E cells, they then explored the effects of Srrm3 depletion on energy metabolism and exocytosis, pathways that they found to be associated with IsletMICs genes. They found that Srrm3 knockdown led to increased basal and glucose-stimulated ATP production and disrupted normal cell morphology due to altered actin cytoskeleton and microtubule polymerization, suggesting that IsletMIC control of insulin secretion acts in part through altered energy metabolism and cytoskeleton reorganization. To explore this further in vivo, they characterized the effects of loss of Srrm3 in mice and found that Srrm3 depletion leads to hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Srrm3−/− mice had lower blood glucose levels under ad libitum feeding, fasting, and postprandial conditions compared to wildtype and Srrm3+/− mice. By measuring insulin plasma levels at fasting and postprandial conditions, they found that the observed hypoglycemia in Srrm3−/− mice was associated with increased insulin secretion. These results suggest that depletion of Srrm3 impairs glucose homeostasis due to inappropriate insulin secretion. In isolated islets from these Srrm3−/− mice, they found that IsletMICs were downregulated to a greater extent than other exons and that the islets secreted more insulin following exposure to glucose or amino acids. Their data demonstrate that perturbation of the alternative microexon program in islets leads to defective insulin secretion. However, IsletMICs did not correspond to the upregulated genes in the Srrm3−/− mice, leaving room for further investigation of the mechanism by which Srrm3 impacts insulin secretion. Pathway analysis pointed to a role for pancreas development, and pancreas histology from newborn and 4 week old mutant mice showed that loss of Srrm3 alters both cell composition and architecture, suggesting that Srrm3 plays a role in maintaining normal islet morphogenesis and development.

Since a majority of T2D GWAS signals are located in regions of the non-coding genome and pancreatic islet function is central to diabetes pathogenesis, the authors used publically available genetic data to investigate whether genetic variation at the SRRM3 locus is associated with altered risk for T2D or variation in glucose levels in the population. They identified that a previously reported variant, rs67070387, which is associated with glycemic traits, maps to an intronic region near the SRRM3 promoter, which is annotated as a weak enhancer. Analysis of bulk human islet RNA-Seq data from 111 non-diabetic caderveric donors revealed an association between rs67070387 and increased SRRM3 expression in cis and IsletMIC inclusion in trans. Additionally, analysis of RNA-Seq data from human islets cultured at different glucose conditions showed that SRRM3 expression and microexon inclusion were significantly increased when exposed to high glucose levels, suggesting that SRRM3 is activated by glucose levels in humans. Further studies in larger sample sizes are needed to replicate these interesting findings and establish a causal relationship between variation in the SRRM3 locus and T2D susceptibility.

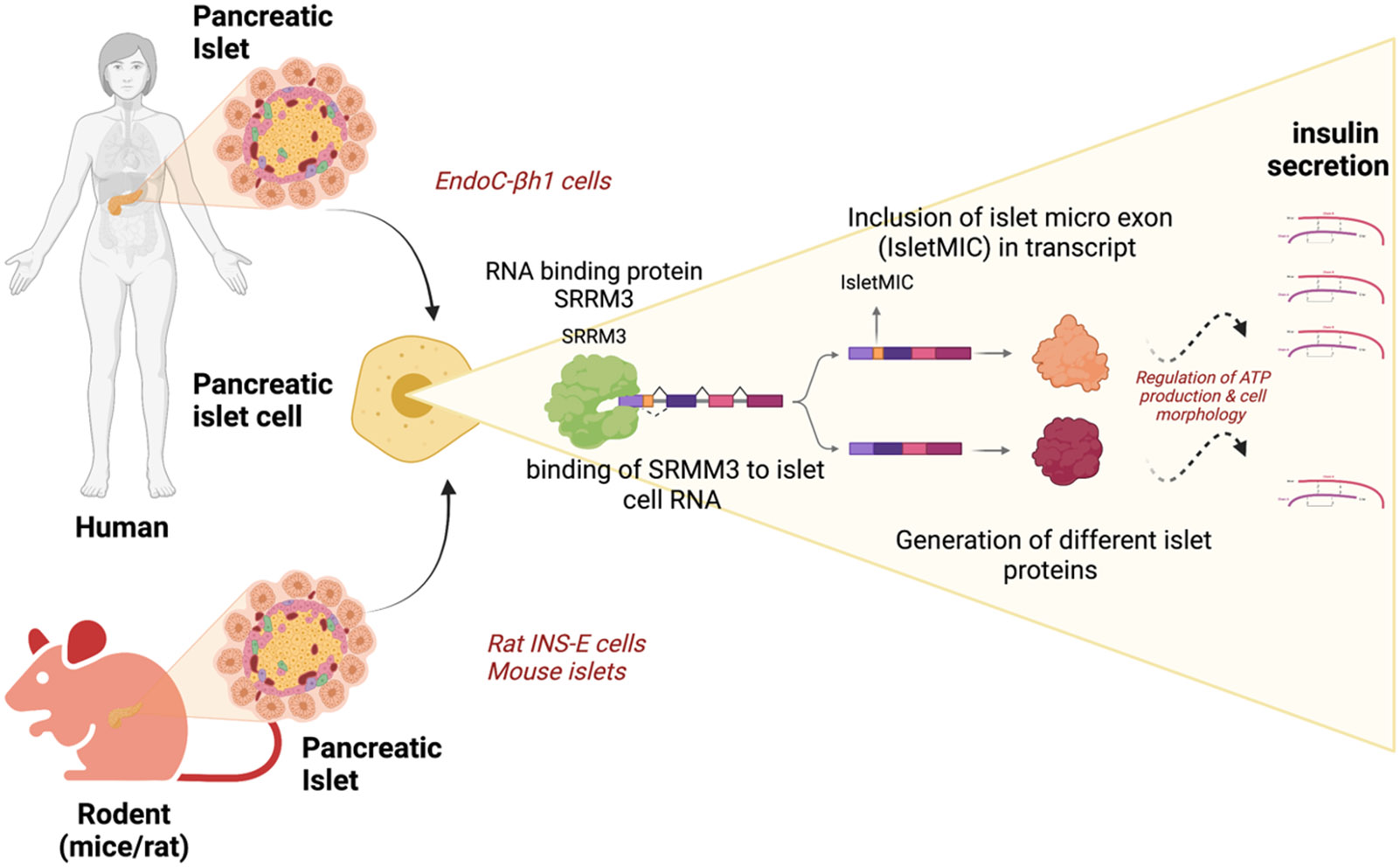

Juan-Mateu et al. shed light on the post-transcriptional landscape of pancreatic islet function by describing a mechanism in which regulation of alternative microexons in islets can have important effects on glucose homeostasis via changes in insulin secretion. Their data support a mechanism by which SRRM3-mediated IsletMIC inclusion in certain genes allows beta cells to properly regulate insulin secretion (Fig 1). This leaves room for further studies to elucidate the mechanisms by which these regulatory changes at the gene level result in phenotypic changes at the cell and organism level.

Figure 1. SRRM3-mediated islet microexon (IsletMIC) inclusion and insulin secretion.

In pancreatic beta cells of rodent and human islets, genes involved in energy metabolism, exocytosis, and other pathways can contain IsletMICs, whose alternative inclusion is mediated by SRRM3. IsletMIC inclusion is associated with increased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

KG declares no conflicts. ALG’s spouse hold stock options in Roche and is an employee of Genentech.

References

- 1.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409(6822):860–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kan Z, Rouchka EC, Gish WR, States DJ. Gene structure prediction and alternative splicing analysis using genomically aligned ESTs. Genome Res. 2001;11(5):889–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banks RE, Dunn MJ, Hochstrasser DF, Sanchez JC, Blackstock W, Pappin DJ, et al. Proteomics: new perspectives, new biomedical opportunities. Lancet. 2000;356(9243):1749–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet. 2008;40(12):1413–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tapial J, Ha KCH, Sterne-Weiler T, Gohr A, Braunschweig U, Hermoso-Pulido A, et al. An atlas of alternative splicing profiles and functional associations reveals new regulatory programs and genes that simultaneously express multiple major isoforms. Genome Res. 2017;27(10):1759–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Marabti E, Abdel-Wahab O. Therapeutic Modulation of RNA Splicing in Malignant and Non-Malignant Disease. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27(7):643–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasquali L, Gaulton KJ, Rodriguez-Segui SA, Mularoni L, Miguel-Escalada I, Akerman I, et al. Pancreatic islet enhancer clusters enriched in type 2 diabetes risk-associated variants. Nat Genet. 2014;46(2):136–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irimia M, Weatheritt RJ, Ellis JD, Parikshak NN, Gonatopoulos-Pournatzis T, Babor M, et al. A highly conserved program of neuronal microexons is misregulated in autistic brains. Cell. 2014;159(7):1511–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torres-Mendez A, Bonnal S, Marquez Y, Roth J, Iglesias M, Permanyer J, et al. A novel protein domain in an ancestral splicing factor drove the evolution of neural microexons. Nat Ecol Evol. 2019;3(4):691–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juan-Mateu J, Bajew S, Miret-Cuesta M, Iniguez LP, Lopez-Pascual A, Bonnal S, et al. Pancreatic microexons regulate islet function and glucose homeostasis. Nat Metab. 2023;5(2):219–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]