Abstract

Background

Preterm birth (PTB) is associated with significant neonatal mortality and morbidity. Universal measurement of cervical length has been proposed as a screening tool to direct intervention to prevent PTB.

Aim

To assess the impact of the introduction of sonographic mid-trimester cervical length screening on the use of cervical cerclage and PTB.

Material and Methods

A retrospective cohort study reviewed two groups of women who underwent cervical cerclage before and after the introduction of universal sonographic cervical length screening. Demographics and outcomes were compared using Student’s t test, Fisher's Exact test and Kaplan–Meier analysis.

Results

Following introduction of universal cervical length screening, the overall rate of cerclage increased from 2.5/1000 births to 6.0/1000 births (p < 0.01). There was a reduction in the proportion of sutures placed purely based on maternal history (50.0% to 30.4%; p < 0.001), while the proportion of sutures placed following ultrasound assessment increased in both high- (21.7 to 36.6%) and low-risk (11.7% to 30.4%) women (p < 0.001). The overall rate of PTB <37 weeks in women has a cerclage was 25.7% and was highest in women undergoing rescue cerclage (64.3%; p < 0.01). There was no difference in the rate of PTB between high- and low-risk women undergoing history- or ultrasound-indicated cerclage. Mean pregnancy length was most prolonged in low-risk women undergoing ultrasound-indicated cerclage, extending gestation from 33.9 to 38.3 weeks (p < 0.01).

Conclusion

Universal cervical length screening results in an increase in the use of cerclage, specifically on the basis of the ultrasound findings. Women who were at low risk but then underwent ultrasound-indicated cerclage experienced most prolongation of pregnancy. Women who were at high risk but had a suture on the basis of ultrasound findings-indicated cerclage represent an alternative method of management with no significant difference in the gestational age of delivery.

Keywords: cerclage, premature birth, cervical length measurement, progesterone, ultrasonography

Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB) affects 8–13% of all pregnancies and is associated with significant neonatal mortality and morbidity.1–3 Effective prediction of risk of PTB allows implementation of therapeutic interventions to prevent this adverse outcome. Historically, risk was assessed on the basis of maternal history, recognizing, for example, the association of spontaneous preterm birth (sPTB) with previous PTB.1,4 Cerclage was the traditional primary intervention, and mitigates the risk of PTB in high-risk women.5,6 Cervical cerclage comprises applying a surgical suture around the cervical canal, commonly being performed vaginally with (Shirodkar) or without (McDonald) dissecting and reflecting the urinary bladder.

More recently, the predictive value of second-trimester transvaginal ultrasound assessment of cervical length has been recognized as a powerful tool to stratify the risk of sPTB.7–9 In asymptomatic high-risk women, ultrasound can be used serially to monitor changes in cervical length,10–12 which may help select women for therapeutic intervention. In low-risk women, it can be used as a screening tool in the second-trimester to identify a subset of women who may also benefit from intervention.13 The indications for cervical cerclage have evolved from being limited to rescue and history-based cerclage for high-risk groups, to include ultrasound-indicated cerclage for both high- and low-risk groups, alongside the continued use of rescue and history-indicated cerclage.

It is not clear how the use of second-trimester transvaginal ultrasound assessment of cervical length has affected the clinical use and outcomes of cervical cerclage. We have reviewed the impact of introducing this approach to screening in our population.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of women who underwent cervical cerclage during pregnancy. The study includes women who underwent cervical cerclage identified through hospital obstetric and theatre admission records. Two cohorts of singleton pregnancies were compared. The first (January 2003 to February 2008) preceded introduction of a policy of universal transvaginal cervical length screening at 18–20 weeks’ gestation. The second (January 2010 to December 2014) followed the introduction of this policy. Data for the 22-month period between these time periods were excluded to allow for transition between screening and management protocols.

Within each cohort, women were first stratified into high- and low-risk groups, according to their clinical history. Women were deemed at high risk if they had a history of previous PTB, ≥3 previous miscarriages (any gestation) or >1 second trimester pregnancy loss, a known congenital uterine anomaly, a history of cone biopsy or large loop excision of the cervical transformation zone (LLETZ). Women were identified as symptomatic prior to insertion of cerclage if they had presented with symptoms and signs of threatened preterm labour.

Ultrasound was not routinely used to stratify risk in the first cohort. Management of women identified as being high-risk was determined by the patient’s obstetrician and the only intervention offered to mitigate risk was cerclage. Progesterone was not routinely prescribed to high-risk women. Low-risk women who remained asymptomatic were not offered any intervention. Women found to have a dilated cervix following presentation with symptoms of threatened preterm birth were offered rescue cerclage.

In the second cohort, high-risk women were offered early elective cerclage (typically performed after combined first-trimester screening, at 12–14 weeks’ gestation) or expectant management with serial ultrasound surveillance of cervical length at 16, 19 and 23 weeks’ gestation. Women who had serial ultrasound surveillance were advised to have a cerclage if the cervix was <25mm in length at any time point or if there was cervical shortening of >10mm between two scans. Progesterone was not routinely prescribed to high-risk women. Low-risk women were offered a transvaginal assessment of cervical length at the time of their routine 18–20-week morphology scan. If their cervix was short (<25mm), they were offered either progesterone (200mg PV nocte) or cerclage as first-line prophylaxis against preterm birth; the choice of intervention being a shared decision between clinician and patient. A proportion of women who were treated with progesterone had a cerclage as a second, delayed intervention if there was further cervical shortening. Another group of women requested treatment with both progesterone and cerclage, although they were advised that there was no evidence to demonstrate a synergistic effect. The final group in this second cohort were symptomatic women who presented with symptoms of threatened preterm labour. These women had a speculum examination and /or transvaginal ultrasound scan as part of assessment at presentation and were assessed for risk of chorioamnionitis before being offered a cerclage if their cervix was short (<25mm) or dilated. The type of cerclage used was determined by the individual obstetrician.

Electronic and paper medical records were reviewed for all included cases. Maternal demographic characteristics, indications for and type of cerclage and pregnancy outcome data were collected. Demographic features and outcomes were compared using Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA for continuous variables and Fisher's Exact test for categorical variables. Kaplan–Meier curves were constructed to determine whether there was a significant difference in outcomes following cervical cerclage. The statistical software package SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all data analyses.

Results

Two hundred and fifty-seven women underwent cervical cerclage during the two study periods. Twenty-seven patients with multiple pregnancies were excluded, and 9 patients were lost to follow-up. Sixty women underwent cerclage between January 2003 and February 2008 (Cohort 1), and 161 women underwent cerclage between January 2010 and December 2014 (Cohort 2). There were a total of 23,535 deliveries within the hospital in the first period and 26,679 deliveries in the second period. The cerclage rates over the two time periods therefore increased from 2.55/1000 to 6.03/1000 births (p < 0.01).

Demographics

The demographic characteristics of the two cohorts are shown in Table 1. Women who had a cerclage in the first cohort were significantly more likely to have had previous spontaneous preterm birth or preterm prelabour rupture of membranes (PPRoM) (71.7% vs 29.2%; p < 0.01). The prevalence of previous cervical surgery increased from 6.7% to 12.4% - but was not statistically significant. There were no other significant differences between the two groups.

Table 1.

Comparison of Maternal Characteristics Between the Two Cohorts of Women Having Cervical Cerclage

| Characteristic | Cohort 1 (n=60) (Jan 2003 - Feb 2008) | Cohort 2 (n=161)(Jan 2010 – Dec 2014) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (mean (SD)) a | 34.2 (4.7) years | 33.7 (4.6) years | 0.47 |

| Maternal age (>35 years) | 27 (45.0%) | 67 (41.6%) | 0.76 |

| Primigravid women (n (%)) | 17 (28.3%) | 57 (35.4%) | 0.20 |

| Previous history of spontaneous preterm birth or preterm rupture of membranes (n (%)) | 43 (71.7%) | 47 (29.2%) | <0.001 |

| ≥3 previous miscarriages | 11 (18.3%) | 22 (13.7%) | 0.40 |

| Previous cone biopsy or LLETZ b | 4 (6.7%) | 20 (12.4%) | 0.24 |

| Shirodkar (as opposed to McDonald) cerclage | 26 (43.3%) | 76 (47.2%) | 0.65 |

Notes: aStandard Deviation; bLarge Loop Excision of Transformation Zone.

Indications for Cerclage

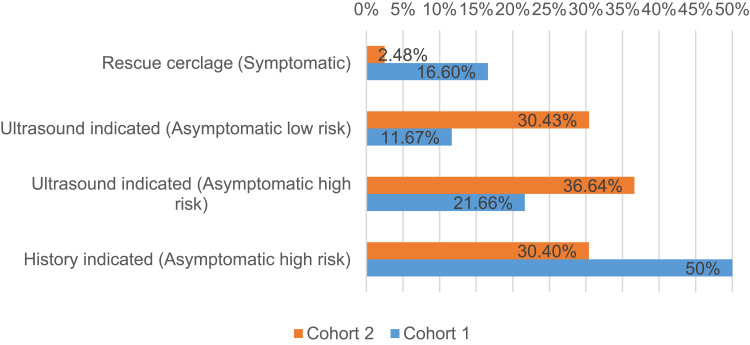

Indications for cerclage were significantly different between the two cohorts. Half of the sutures placed in the first cohort were performed on high-risk women, on the basis of history alone (30 procedures; prevalence of 1.27 per 1000 births). Although ultrasound surveillance was not routine offered, more than one in five women stitched in this group had prior ultrasound assessment that identified a short cervix. A total of 43 (71.7%) women who had a suture were high-risk; the overall prevalence of cerclage in high-risk pregnancies was 1.82 per 1000 pregnancies. Similarly, although ultrasound surveillance was not offered on a routine basis, a small number of asymptomatic low-risk women were identified as having a short or dilated cervix and had a cerclage. The prevalence of cerclage for low risk/asymptomatic women with a short cervix was 0.30 per 1000 births. Ten (16.7%) women presented with symptoms associated with preterm birth and, after been identified as having a dilated cervix, had a rescue cerclage (prevalence of 0.42 per 1000 births).

The overall rate of cerclage increased in the second cohort, and the relative proportions in high- and low-risk groups were significantly different. More high-risk women were identified as needing a cerclage, and the overall prevalence of treatment for high-risk women increased significantly from 1.82 per 1000 births to 4.05 per 1000 births (p < 0.01). The rate of elective cerclage was similar to the previous cohort (1.27 per 1000 vs 1.84 per 1000 births (p = 0.12)) but the rate of cerclage following serial ultrasound surveillance in high-risk women increased significantly from 0.55 per 1000 women to 2.21 per 1000 women (p < 0.01). More sutures were placed in high-risk women following ultrasound surveillance rather than on the basis of history alone. Four (6.8%) of the 59 women that underwent cerclage after serial ultrasound surveillance were found to have a dilated cervix at the last scan, which could be regarded as a failure of this process of assessment. Thirty percent (49/161) of sutures in the second cohort were inserted in asymptomatic women of apparent low risk who were found to have a short cervix during ultrasound surveillance; a significant six-fold increase from 0.30 per 1000 births to 1.84 per 1000 births (p < 0.01). The prevalence of rescue cerclage was lower, falling from 0.42 per 1000 births to 0.15 per 1000 births, although this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.11). The total proportion of sutures placed in a dilated cervix fell from 25% to 8.7% (p<0.01) between the two cohorts. Figure 1 compares the indications of cervical cerclage between the two periods.

Figure 1.

Indications of cervical cerclage.

Gestation of Cerclage

High-risk women offered elective cerclage on the basis of clinical history were universally offered a suture toward the end of the first trimester of pregnancy (12.4–14.4 weeks); there was no difference between the two cohorts. This was significantly earlier (p < 0.01) than both high- and low-risk groups of women offered cerclage after ultrasound assessment who typically had a cerclage at 19–22 weeks’ gestation. Rescue cerclage was also typically performed late (mean 21–22 weeks’ gestation) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Indications for, and Pregnancy Outcomes After, Cerclage

| Indications for Cerclage | Progesterone | Gestational Age at Stitch Insertion Weeks: Mean (IQR)a | Gestational Age at Delivery Weeks: Mean (IQR) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort 1 (n=60) | Cohort 2 (n=161) | p value | Cohort 1 (n=60) | Cohort 2 (n=161) | P value | Cohort 1 (n=60) | Cohort 2 (n=161) | P value | ||

| High Risk / Asymptomatic selected by clinical history |

No | 30 (50%) | 49 (30.4%) | <0.01 | 13.3 (12.4–13.9) | 13.7 (13–14.4) | 0.1 | 38.1 (37.3–39.0) | 36.9 (36.7–38.7) | 0.2 |

| High Risk / Asymptomatic selected by serial ultrasound / short cervix |

No | 11 (18.3%) | 29 (18%) | 21.1 (19.8–21.5) | 19.1 (17.0–21.7) | 0.1 | 38.3 (38.1–39.3) | 36.9 (36.1–39.0) | 0.3 | |

| High Risk / Asymptomatic selected by serial ultrasound / short cervix |

Yes | 1 (1.7%) | 26 (16.1%) | 19.6 (-) | 21.3 (19.2–23.8) | 0.5 | 35.4 | 37.1 (36.4–39.3) | 0.6 | |

| High Risk / Asymptomatic selected by serial ultrasound / dilated cervix |

No | 1 (1.7%) | 4 (2.5%) | 19.7 (-) | 22.6 (20.5–23.9) | 0.5 | 22.0 | 31.1 (22.8–40.0) | 0.5 | |

| Low Risk / Asymptomatic selected by ultrasound / short cervix |

No | 3 (5%) | 21 (13%) | 22.3 (21.4–23.0) | 20.4 (19.0–21.3) | 0.1 | 33.9 (30.8–36.3) | 38.3 (37.4–39.9) | 0.01 | |

| Low Risk / Asymptomatic selected by ultrasound / short cervix |

Yes | – | 22 (13.7%) | – | – | 21.9 (20.3–23.2) | – | – | 37.6 (37.1–39.1) | – |

| Low Risk / Asymptomatic selected by ultrasound / dilated cervix |

No | 4 (6.7%) | 6 (3.7%) | 18.5 (18.3–18.8) | 19.8 (19.1–21.4) | 0.2 | 22.9 (19.5–23.4) | 31.6 (23.8–39.3) | 0.1 | |

| Symptomatic of threatened preterm labour dilated cervix (speculum or ultrasound) |

No | 10 (16.7%) | 4 (2.5%) | <0.01 | 21.4 (21.6–22.2) | 22.4 (20.8–23.9) | 0.6 | 32.3 (29.5–36.7) | 31.1 (23.9–39.1) | 0.8 |

Note: aInterquartile Range.

Pregnancy Outcomes

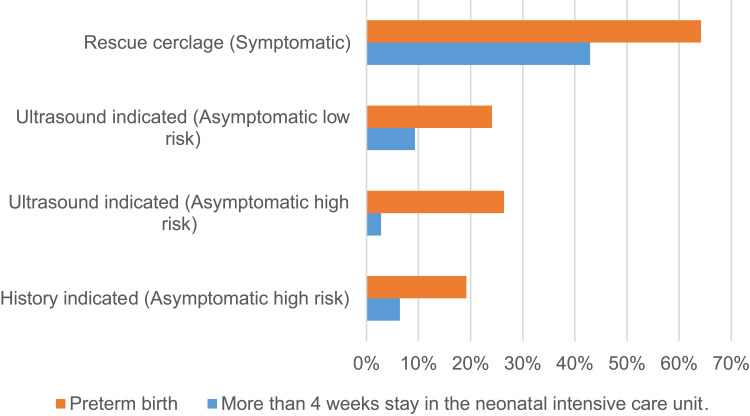

Cervical cerclage is offered to women deemed at high risk of preterm birth; this is reflected in the overall rate of preterm birth <37 weeks’ gestation, which 25.3% (56/221 pregnancies). The risk of PTB was significantly higher in symptomatic women undergoing rescue cerclage (64.3%; p < 0.01), who delivered at a mean gestational age of 31.7 weeks (Table 3). Women who had a rescue cerclage were also more likely to have PPRoM, although this result was not significant (p = 0.07), potentially impacted by low numbers of affected pregnancies. Surviving infants following rescue cerclage were more likely to have a prolonged NICU admission (p < 0.01). Figure 2 describes the statistically significant outcomes among different indications of cervical cerclage.

Table 3.

Neonatal Outcomes Described by Indication for Cerclage

| History-indicated Asymptomatic High-risk N=78 | Ultrasound-indicated Asymptomatic High-risk N=72 | Ultrasound-indicated Asymptomatic Low-risk N=54 | Rescue Cerclage N=14 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks) (n (%)) | 15 (19.2%) | 19 (26.4%) | 13 (24.1%) | 9 (64.2%) | <0.01 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks; mean (SDa)) | 37.5 (2.6) | 36.6 (4.6) | 36.5 (4.9) | 31.7 (6.8) | <0.01 |

| Preterm premature rupture of membranes (n (%)) | 6 (7.6%) | 6 (8.3%) | 8 (14.3%) | 4 (30.8%) | 0.07 |

| Neonatal death (n (%)) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (4.2%) | 2 (3.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0.02 |

| Respiratory distress syndrome (n (%)) | 3 (3.8%) | 4 (5.6%) | 3 (5.6%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0.82 |

| NICUb stay more than 4 weeks (n (%)) | 5 (6.4%) | 2 (2.8%) | 5 (9.3%) | 6 (42.9%) | <0.01 |

Notes: aStandard Deviation; bNeonatal Intensive Care Unit.

Figure 2.

Significant outcomes described for different indications of cervical cerclage.

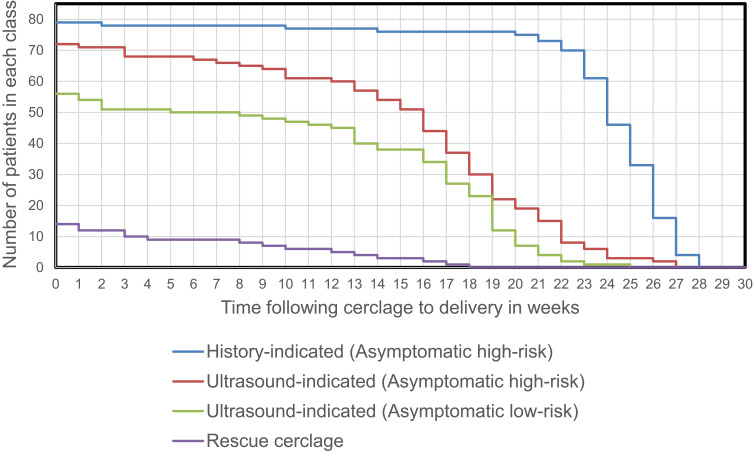

There was no significant difference in gestational age at delivery of women who underwent history-indicated elective cerclage (mean 37.2 weeks) or high- and low-risk women undergoing ultrasound-indicated cerclage (mean 36.5 weeks and 35.9 weeks respectively). Kaplan–Meier analysis appears to show a more rapid decay rate amongst high-risk women who had ultrasound-indicated rather than history-indicated cerclage (Figure 3) but when this is adjusted for the fact that the cerclage was inserted a mean of 8 weeks earlier, there is no significant difference between curves. The rate of preterm delivery for women who had a rescue cerclage is notably different. Interestingly, the Kaplan–Meier plots for high-risk and low-risk groups that had an ultrasound-indicated cerclage show no significant difference – suggesting that ultrasound is of equal value as a predictor in these two settings.

Figure 3.

Kaplan Meier outcomes of cerclage based on indication.

The finding of a significant increase in mean gestational age at delivery in asymptomatic low-risk women who underwent ultrasound-indicated cerclage (33.9 to 38.3 weeks; p < 0.01) is likely a reflection of the fact that only “extreme” reductions in cervical length were recognised prior to the introduction of a universal screening policy.

Effect of Progesterone

Progesterone was prescribed to only one woman in the first cohort and to 48 women in the second cohort (p < 0.01). In the second cohort, 26 of the 59 (44%) high-risk women who had a cerclage after ultrasound surveillance had progesterone prescribed as an additional intervention (Table 2). There was a trend towards delayed insertion of cerclage in these high-risk women (19.6 vs 21.1 weeks; p = 0.06), but despite this delay there was no difference in mean gestational age at delivery ((37.2 weeks/no progesterone vs 36.9 weeks/with progesterone; p = 0.70). Twenty-two (51%) of low-risk women in the second cohort who were found to have a short cervix were prescribed progesterone before, or at the time of cerclage. Low-risk women with a short cervix who were prescribed progesterone underwent cerclage at a later gestation than those not treated with progesterone (20.4 vs 21.9 weeks, p = 0.03); but once again, there was no difference in gestational age at delivery with or without adjuvant progesterone treatment (37.6 vs 38.3 weeks; p = 0.85).

Short vs Dilated Cervix

Dilated rather than short cervix diagnosed by routine cervical screening has been linked to worse outcome, where the mean gestational age of delivery was found to be shorter. This finding was present despite the fact that both high- and low-risk women with an asymptomatic dilated cervix underwent cerclage at similar times to women with a short but closed cervix (20.1 vs 20.6 weeks; p = 0.5), cerclage after cervical dilatation was associated with earlier delivery (28.3 weeks vs 36.7 weeks; p < 0.01).

Adverse Outcomes

The overall adverse outcome rate was 3.6% (8/221). Adverse outcomes were defined as PPROM within 24 hours of cerclage (2/8, 25%); infection within one week of cerclage (2/8, 25%); significant bleeding (2/8, 25%); or incomplete removal of cerclage (2/8, 25%). The risk of adverse outcome was least for history-indicated cerclage at <14 weeks gestation (1.3%) and significantly more likely for ultrasound-indicated cerclage (3.9%) or for rescue cerclage (14.3%) (p < 0.01).

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study has identified that the introduction of a policy of screening for risk of preterm birth through universal second-trimester transvaginal sonographic assessment of cervical length is associated with increased use of cervical cerclage. Routine ultrasound assessment of low-risk women who were asymptomatic at the time of the 18–20-week morphology scan resulted in a four-fold increase in placement of a suture in this cohort of women. This increase likely reflects the change in screening practice – and is seen despite the fact that many women were managed with progesterone rather than cerclage – and is consistent with reports from other groups.14 Surprisingly, the new policy was also associated with an increase in the rate of intervention in high-risk pregnancies; most noticeably through a six-fold increase in cerclage amongst women having serial cervical surveillance rather than a purely elective procedure. We suggest that the framework of routine surveillance led to better identification of, and consistent management of pregnancies at high-risk of preterm birth. Interestingly, there was also a large increase in reporting of LLETZ procedures in the cohort undergoing routine surveillance (from 6.7% to 12.4%). LLETZ is associated with both an increase in the risk of sPTB and also with shorter cervical length in the second trimester.15,16

One in six cerclage placed in the first cohort was rescue stitches – placed in symptomatic women found to have a dilated cervix. This form of late presentation was significantly reduced in the second cohort – which likely led to better neonatal outcomes as rates of preterm birth after rescue cerclage were extremely high. Similarly, it should be noted that placement of cerclage in asymptomatic women who were found, through ultrasound, to have a dilated rather than short cervix, was associated with earlier preterm birth.

The data demonstrate that women who require cerclage, in any setting, have very high rates of preterm birth. We would advocate ongoing surveillance post cerclage for recognition of this risk and minimization of the risks associated with preterm delivery.17,18 Although very few low-risk women in the first cohort had a cerclage based on ultrasound findings of a short cervix, it is interesting to note that these women delivered earlier than the equivalent group in the second cohort, identified through routine ultrasound screening (33.9 weeks’ vs 38.3 weeks’ gestation). The policy of universal screening may prolong pregnancy by even a few weeks gestation, resulting in less neonatal morbidity.1

The use of ultrasound surveillance for high-risk patients remains controversial. Whilst this approach reduces the number of cases where a cerclage is inserted, the delay potentially makes the procedure more difficult. Six percent of women managed through this protocol subsequently needed cerclage and were found to have a dilated cervix at their last scan – which appears to be associated with higher ongoing morbidity. However, the cohort of women who were at high risk and had cerclage due to cervical shortening (rather than cervical dilatation) had very similar outcomes to those that had a cerclage on the basis of clinical history. This is consistent with other reports.19,20 A future subgroup analysis of individual risk factors may be useful in determining the utility of cervical length measurement in high-risk women.

Vaginal progesterone has previously been shown to prevent PTB in both high- and low-risk women.21,22 Only a minority of women included in this series had progesterone in addition to cerclage. There was no significant difference in gestation of delivery between equivalent groups that had/did not have progesterone. High-risk women with a short cervix in our cohort were typically given progesterone prior to cerclage; the progression to cerclage was likely due to failure of first-line progesterone therapy. It is of value to recognize that there was no difference in outcome related to preterm birth in these cases. This finding is supported by a previous study showing that cerclage prolongs pregnancies after failure of first-line progesterone therapy.23 Low-risk women who were given progesterone as an adjunct to cerclage also delivered at a similar gestation to those that had cerclage alone. The value of “dual therapy” has not been widely explored, and it will require a large cohort to identify any benefit.24–27

Limitations of our study include its retrospective nature, the small case numbers in some subgroups, and the inability to compare pregnancy outcomes to a general low-risk population. The study does, however, demonstrate the ongoing relevance of cervical cerclage in preventing PTB, and directs further avenues of inquiry, including the need to clarify the role of cervical length surveillance in women at high-risk for PTB and the adjuvant effect of progesterone following cerclage.

Conclusions

Routine ultrasound surveillance of cervical length for prediction of preterm birth leads to an increase in rates of cervical cerclage in most circumstances – but a decrease in the rate of rescue cerclage, which is associated with the highest ongoing risk of preterm delivery. If a high-risk pregnancy is managed through serial ultrasound surveillance, then relatively early recourse to cerclage provides a better outcome than use of cerclage once the cervix is dilated. These outcomes are similar to those of women having an elective cerclage earlier in pregnancy. More low-risk women who have a short cervix are identified through a structured program of universal screening, and these women achieve better gestational outcomes. Overall, preterm delivery rates remain high after cerclage – and these women should be managed with a higher level of ongoing surveillance.

Funding Statement

This research did not receive any specific funding.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital [Third party]. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available [From the corresponding author] with the permission of the IRB committee at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital [Third party]. Informed consent was obtained from the study participants prior to the study commencement.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the hospital ethics committee (RPA X11-0305) at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital. Permission for identification of patients and for review of their medical records was granted. Consents are available on request. The study complies with the declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D, et al. Born too soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health. 2013;10(SUPPL. 1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-S1-S2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Heal. 2019;7(1):e37–e46. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30451-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogel JP, Chawanpaiboon S, Moller AB, Watananirun K, Bonet M, Lumbiganon P. The global epidemiology of preterm birth. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;52:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Preterm birth 1: epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owen J, Hankins G, Iams JD, et al. Multicenter randomized trial of cerclage for preterm birth prevention in high-risk women with shortened midtrimester cervical length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(4):375.e1–375.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alfirevic Z, Stampalija T, Medley N. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2017(6). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008991.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ, et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. national institute of child health and human development maternal fetal medicine unit network. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(9):567–572. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602293340904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berghella V, Roman A, Daskalakis C, Ness A, Baxter JK. Gestational age at cervical length measurement and incidence of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 I):311–317. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000270112.05025.1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grobman WA, Lai Y, Iams JD, et al. Prediction of spontaneous preterm birth among nulliparous women with a short cervix. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35(6):1293–1297. doi: 10.7863/ultra.15.08035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guzman ER, Mellon C, Vintzileos AM, Ananth CV, Walters C, Gipson K. Longitudinal assessment of endocervical canal length between 15 and 24 weeks’ gestation in women at risk for pregnancy loss or preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1998;92(1):31–37. doi: 10.1080/00006250-199807000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szychowski JM, Owen J, Hankins G, et al. Timing of mid-trimester cervical length shortening in high-risk women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;33(1):70–75. doi: 10.1002/uog.6283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crane JMG, Hutchens D. Follow-up cervical length in asymptomatic high-risk women and the risk of spontaneous preterm birth. J Perinatol. 2011;31(5):318–323. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orzechowski KM, Boelig RC, Baxter JK, Berghella V. A universal transvaginal cervical length screening program for preterm birth prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):520–525. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu C, Lim B, Robson S. increasing incidence rate of cervical cerclage in pregnancy in Australia: a population-based study. Healthcare. 2016;4(3):68. doi: 10.3390/healthcare4030068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer RL, Sveinbjornsson G, Hansen C. Cervical sonography in pregnant women with a prior cone biopsy or loop electrosurgical excision procedure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(5):613–617. doi: 10.1002/uog.7682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poon LCY, Savvas M, Zamblera D, Skyfta E, Nicolaides KH. Large loop excision of transformation zone and cervical length in the prediction of spontaneous preterm delivery. BJOG an Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;119(6):692–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03203.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berghella V, Ciardulli A, Rust OA, et al. Cerclage for sonographic short cervix in singleton gestations without prior spontaneous preterm birth: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials using individual patient-level data. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50(5):569–577. doi: 10.1002/uog.17457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood AM, Dotters-Katz SK, Hughes BL. Cervical cerclage versus vaginal progesterone for management of short cervix in low-risk women. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36(2):111–117. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1668547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berghella V, MacKeen AD. Cervical length screening with ultrasound-indicated cerclage compared with history-indicated cerclage for prevention of preterm birth: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(1):148–155. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821fd5b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simcox R, Seed PT, Bennett P, Teoh TG, Poston L, Shennan AH. A randomized controlled trial of cervical scanning vs history to determine cerclage in women at high risk of preterm birth (CIRCLE trial). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(6):623.e1–623.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R, Nicolaides K, et al. Vaginal progesterone vs cervical cerclage for the prevention of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix, previous preterm birth, and singleton gestation: a systematic review and indirect comparison metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(1):42.e1–42.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.10.877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romero R, Conde-Agudelo A, Da Fonseca E, et al. Vaginal progesterone for preventing preterm birth and adverse perinatal outcomes in singleton gestations with a short cervix: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(2):161–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Enakpene CA, DiGiovanni L, Jones TN, Marshalla M, Mastrogiannis D, Della Torre M. Cervical cerclage for singleton pregnant patients on vaginal progesterone with progressive cervical shortening. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(4):397.e1–397.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park JY, Jung YM, Kook SY, Jeon SJ, Oh KJ, Hong JS. The effect of postoperative vaginal progesterone in ultrasound-indicated cerclage to prevent preterm birth. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2019. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2019.1668371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roman AR, Da Silva Costa F, Araujo Júnior E, Sheehan PM. Rescue adjuvant vaginal progesterone may improve outcomes in cervical cerclage failure. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2018;78(8):785–790. doi: 10.1055/a-0637-9324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinkey RG, Garcia MR, Odibo AO. Does adjunctive use of progesterone in women with cerclage improve prevention of preterm birth?*. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2018;31(2):202–208. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1280019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavie M, Shamir-Kaholi N, Lavie I, Doyev R, Yogev Y. Outcomes of ultrasound and physical-exam based cerclage: assessment of risk factors and the role of adjunctive progesterone in preventing preterm birth—a retrospective cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301(4):981–986. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05482-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital [Third party]. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available [From the corresponding author] with the permission of the IRB committee at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital [Third party]. Informed consent was obtained from the study participants prior to the study commencement.