Abstract

KCNQ1 (Kv7.1 or KvLQT1) is a voltage-gated potassium ion channel that is involved in the ventricular repolarization following an action potential in the heart. It forms a complex with KCNE1 in the heart and is the pore forming subunit of slow delayed rectifier potassium current (Iks). Mutations in KCNQ1, leading to a dysfunctional channel or loss of activity have been implicated in a cardiac disorder, long QT syndrome. In this study, we report the overexpression, purification, biochemical characterization of human KCNQ1100–370, and lipid bilayer dynamics upon interaction with KCNQ1100–370. The recombinant human KCNQ1 was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified into n-dodecylphosphocholine (DPC) micelles. The purified KCNQ1100–370 was biochemically characterized by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, western blot and nano-LC-MS/MS to confirm the identity of the protein. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy was utilized to confirm the secondary structure of purified protein in vesicles. Furthermore, 31P and 2H solid-state NMR spectroscopy in DPPC/POPC/POPG vesicles (MLVs) indicated a direct interaction between KCNQ100–370 and the phospholipid head groups. Finally, a visual inspection of KCNQ1100–370 incorporated into MLVs was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The findings of this study provide avenues for future structural studies of the human KCNQ1 ion channel to have an in depth understanding of its structure-function relationship.

INTRODUCTION

Membrane proteins play a significant role in several biochemical and physiological pathways1–3. The human KCNQ1 (Kv7.1) protein is a member of the voltage-gated potassium channel (Kv) superfamily4–10. Upon association with KCNE1 (minK), KCNQ1 forms a channel complex in the heart, causes an increase in the current amplitude and slows down the channel activation kinetics8–13. Mutations in KCNQ1 result in the loss of function or channel dysfunction causing disorders like long QT syndrome, atrial fibrillation, and congenital deafness14–20. Human KCNQ1 consists of 676-amino acid residues which is divided in three distinct domains: N-terminal cytosolic domain (100 amino acids), six transmembrane helices forming the channel domain (~260 amino acids), and C-terminal cytosolic domain (~300 amino acids). The channel domain comprises a voltage sensor, Q1-VSD: (helix S1-S4) and a pore domain, PD: (helix S5-S6)21,22. Computational modeling and electrophysiology-based patch clamp studies have provided several key features of the channel with respect to its structure and function21,23–27. Cryo-EM structure of KCNQ1/CaM complex from Xenopus laevis in the uncoupled state pin pointed several key features of the channel in its open conformation28. KCNQ1 is unique in that it can conduct current even when Q1-VSD adopts an intermediate conformation, unlike other Kv channels29–31. Most studies on human KCNQ1 channel focused on truncated versions of the KCNQ1, including the Q1-VSD and the soluble cytosolic C-terminal domain32–35. In order to understand the mechanism behind VSD-PD coupling and the topology and structural dynamics of KCNQ1, full length of the channel needs to be purified. Here, we report the overexpression, purification and membrane interaction studies of KCNQ1100–370, comprising all six transmembrane helical segments of the channel using 31P and 2H solid-state NMR spectroscopy.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Overexpression of KCNQ1100–370

The expression vector (pET-21b) containing C-terminal His-tagged (10x) human KCNQ1 encoding amino-acid residues 100–370, was tested for expression in E.coli strains: BL21 (DE3), BL21 (DE3)-Star, Rosetta/C43 (DE3), BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RP. The transformed cells were cultured by picking a single colony and screened for overexpression in M9 minimal medium with MEM vitamin (Mediatech), Luria Broth (LB), and Terrific Broth (TB) using appropriate antibiotics. Different temperature conditions were tested to grow the cells and induce overexpression. The cultures were induced once the OD600 reached 0.6–0.8 by adding 1 mM IPTG and the protein was allowed to express overnight.

KCNQ1100–370 Purification

The cells were harvested/pelleted by centrifugation at 6500 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. Furthermore, pelleted cells were processed using 20x lysis buffer (75 mM Tris-base, 300 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, pH = 7.5, PMSF (20 mg/mL), LDR stock: 100 mg/mL Lysozyme, 10 mg/mL DNase, 10 mg/mL RNase, Magnesium Acetate (5 mM), and 2 mM TCEP. The cells were tumbled for 30 min at room temperature. Cell suspension was sonicated using Fisher Scientific Sonic Dismembrator Model 500 for up to 15 min (depending on the cell density) at 40% amplitude on ice. Empigen BB detergent (30% stock to a final concentration of 3%) was added to the lysate in order to dissolve all the membranes. The empigen mediated solubilization of the membranes was tested at room temperature for 3 hr and overnight at 4°C. The un-dissolved membranes and other cell debris was centrifuged at low speed for 30 min and the supernatant was collected for further purification. To purify the KCNQ1100–370, a pre-equilibrated Ni(II)-NTA superflow resin (Qiagen) (resin was equilibrated with cold buffer A: 40 mM HEPES, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP, pH = 7.5) was added to the supernatant and rotated at 4°C for 30 min. Post incubation, the resin-supernatant mix was spun at 4000 rpm to collect the protein bound resin fraction. This resin was transferred to a column using cold buffer A supplemented with Empigen and 2 mM TCEP before wash steps (wash buffer: 50 mM imidazole + Empigen + 2 mM TCEP). Detergent exchange was carried out with cold buffer A + DPC + 2 mM TCEP adding 1 mL at a time. The KCNQ1100–370 protein was eluted with 250 mM imidazole + DPC + 2 mM TCEP. Total yield of the purified protein was estimated with a Nanodrop and purity was confirmed by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis.

Immunoblot verification of recombinant KCNQ1100–370 expression

The expressed KCNQ1100–370 protein was immunoblotted to confirm its expression and purity. Different samples corresponding to flow, wash and purified KCNQ1100–370 were run in SDS-PAGE for 90 min at 120 V. The protein was transferred on to nitrocellulose membrane and blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate buffered saline containing Tween 80 (PBST), for 60 min at room temperature. The blocked membrane was treated with anti-His tag antibody (Invitrogen, titer 1:8000) for 60 min at room temperature. Protein blot was treated with ECL substrate (Bio-Rad) and image developed using a chemiluminescence imager.

Nano-LC-MS/MS analysis of purified KCNQ1100–370 protein

Approximately 10 ug of eluted KCNQ1 protein was run with a 4–12% Bis Tris gel (Invitrogen, #NP0321) gradient SDS-PAGE gel. The protein separation was performed at 125 V for 15 min. The protein in gel was fixed using a solution of 50% ethyl alcohol, 10 % acetic acid solution in water. Once the fixation reaction was done (overnight), 2 cm gel region was excised using a razor blade and sliced before in gel digestion. In gel trypsin digestion and peptide recovery was performed as previously described36.

Nano-LC-MS/MS analysis was performed as previously described37,38. Mass spectrometry (MS) analysis was performed on a TripleTof 5600+ mass spectrometer (Sciex; Concord, Ontario, Canada). MS was also coupled with a chromatographic nanoLC-ultra nanoflow system (Eksigent, Dublin, CA). ~2.0 μg of extracted peptides from the protease digestion step were loaded on to a trap column (Eksigent Chrom XP C18-CL-3 μm 120 Å, 350 μm × 0.5 mm; Sciex, Toronto, Canada) for concentration and desalting steps. The chromatographic separation was performed using Acclaim PepMap100 C18 LC column (75 μm × 15 cm, C18 particle sizes of 3 μm, 120 Å) (Dionex; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. The chromatographic gradient used in peptides elution was a variable mobile phase (MP) from 95% of 0.1% formic acid (gradient A) to 40% of 99.9% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid (gradient B) for 70 mins, furthermore from 40% of gradient B to 85% phase B of gradient B for 5 minutes. The MS data was collected on data dependent mode (DDA)37,38. Protein Pilot v.5.0, (Sciex) software was used to perform a protein data base search against SwissProt database (version: 196) with a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.05.

Reconstitution into Lipid Bilayers

All powdered phospholipids were purchased from Avanti polar lipids (Alabaster, AL) and stored at −20°C. 1,2-dipalmitoyl-d62-sn-glycero-3-phosphotidylcholine (DPPC-d62), 1-palmitoyl-2oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphotidylcholine (POPC), and 1-palmitoyl-2oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphotidylglycerol (POPG) were used to prepare 1:3:1 (DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG). Powdered lipids were dissolved in chloroform and dried to a film under a stream of nitrogen and vacuum dried overnight to remove residual solvent. The film was rehydrated in deuterium depleted buffer (5 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) and stored at −20°C and used within a week.

KCNQ1100–370 protein was mixed with an appropriate amount of rehydrated lipids to achieve a lipid/protein molar ratio of 400:1 and freeze/thawed three times to equilibrate. SM2 Bio Beads (Bio-Rad) were washed with methanol followed by water (8 column volumes each) using a gravity flow column prior to use. Bio Beads were added to the equilibrated mixture and rotated at 4°C overnight. To remove any residual detergent, dialysis was performed for 24 h and buffer was changed every 6–8 h. The resulting sample was centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 2 min to remove the Bio Beads. The proteoliposomes were pelleted at 100,000 rpm for 45 min at 4°C. The proteo-liposome pellet was resuspended in deuterium depleted buffer (5 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) and was used for spectroscopic studies within 24 h. The protein incorporation efficiency was calculated by estimating the protein in the supernatant fraction after ultracentrifugation. Samples were extruded using 50-nm filter membrane for TEM.

Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy

An Aviv Circular Dichroism Spectrometer model 435 was used to perform CD experiments. CD scans were collected from 190–260 nm and the overall signal averaging was performed at 10 scans with a bandwidth of 1 nm. The quartz cuvette path length was 1.00 mm, and CD spectra were recorded at 296 K. Spectra of empty vesicles without the protein were used to account for the background lipid absorbance and light scattering phenomenon and subtracted from lipid-protein spectra. Spectra were processed and analyzed on Dichroweb using CONTIN with the SMP180 reference set40. The spectral width of 200–240 nm was used for data analysis39–46.

Solid State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

A Bruker Advance 500 MHz WB UltraShield NMR spectrometer equipped with a 4 mm triple resonance CPMAS probe (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) was used to record all NMR data. The 31P NMR spectra were collected at 200 MHz with proton decoupling of 4-μs 90° pulse and a 4 sec recycle delay. The collected free induction decay was processed using 300 Hz of line broadening. The data was analyzed as previously described47–53. 2H NMR spectra were collected at 76.77 MHz using a standard quadrupolar echo pulse sequence (3 μs 90° pulse length, 40 μs inter-pulse delay with a 0.5 sec recycle delay). The spectral width was set to 100 kHz. Exponential line broadening of 100 Hz was used before the Fourier transformation was performed. Both 31P and 2H experiments were carried out at 25°C. Data analysis for 2H NMR was done as previously reported54. DePaking of 2H spectra were performed using MATLAB with the dePaking script published and provided by the Brown group at the University of Arizona54. The dePaked spectra were used to pick the individual peaks and quadrupolar splitting values were determined by plotting the dePaked spectra on Igor Pro 6.0.3.1. The quadrupolar splitting of each peak corresponds to the deuterium atoms bonded to different carbons on the lipid acyl chain with the peak of the 2H nuclei of the terminal methyl carbon appearing closest to 0 kHz and assigned as carbon number 16. The remaining carbon number assignments were made in decreasing order as the quadrupolar splitting values for the respective 2H atoms increased. The quadrupolar splitting for the 2H atoms on the carbons closest to the glycerol backbone appear as a plateau and were estimated by integrating the last broad peak. Order parameters for 2H atoms on each carbon were calculated using the quadrupolar splitting values and equation (1).

| (1) |

Where is the quadrupolar splitting value, represents deuterium quadrupolar coupling constant which is equal to 167 kHz for all C-D covalent bonds, and is the order parameter for the deuterium on the given carbon.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

The samples for TEM were prepared as previously described55. One drop of control DPPC/POPC/POPG vesicles and KCNQ1100–370 incorporated vesicles were adsorbed to 200 mesh copper carbon-coated grids and incubated for 10 sec. The excess solution was then removed using a filter paper. The grids were stained with two drops of 1.5% ammonium molybdate for 10 sec and extra stain was removed with filter paper. Images were recorded using Joel-1200 electron microscope at 100keV.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Expression and Purification of human-KCNQ1100–370

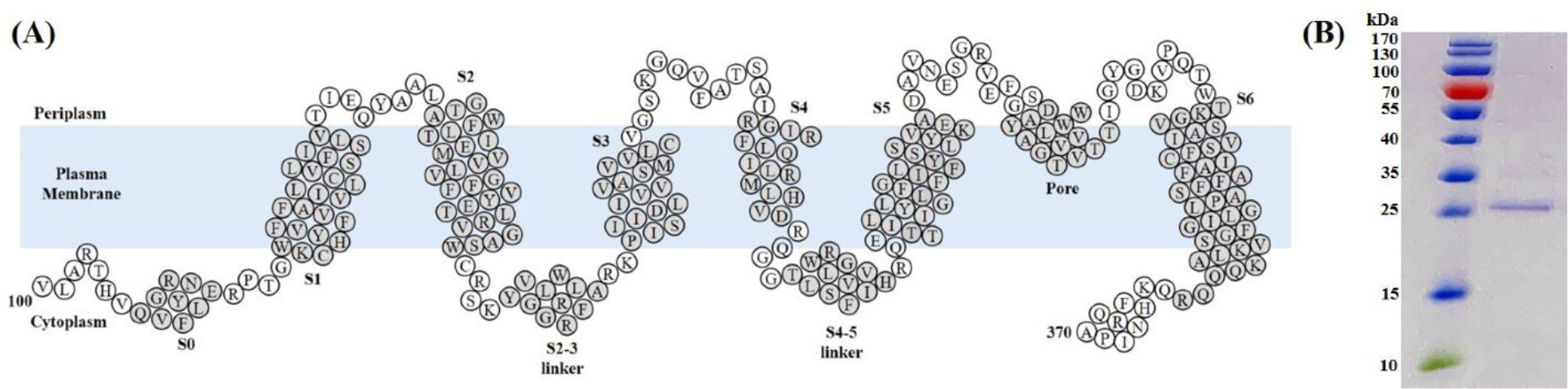

C-terminally His-tagged (10x) human KCNQ1 construct comprising residues 100–370 were tested for its expression in several E. coli strains, BL21 (DE3), BL21 (DE3)-Star, Rosetta/C43 (DE3), BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RP. Among all the strains tested, BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RP with TB culture media showed the highest expression levels and therefore was chosen for subsequent experiments. Higher expression levels were observed when the cells were grown at 37°C with induction carried out at 25°C after cooling down the cultured cells to room temperature. Membrane proteins suffer from lower expression yields and difficulties in folding upon overexpression, one of the major hurdles in their studies for structural and functional characterization. Human KCNQ1 is a six-pass transmembrane protein. Out of the 6 helices, first four (S1–S4) comprise the voltage sensor domain (Q1-VSD), while S5 and S6 constitute the pore domain (PD) of the protein (Figure 1A). Q1-VSD has been successfully expressed and characterized using solution NMR and EPR spectroscopic techniques32,33,35. After the cell lysis step, all membranes were solubilized using Empigen BB detergent. Two different temperature conditions were tested, 3 hr at room temperature and overnight at 4°C. The overall recovery was higher when the solubilization was carried out overnight at 4°C. The final purified protein was eluted in DPC micelles. The expression yield for the KCNQ1100–370 was ~2.5 mg per liter of TB culture. Although our optimized expression workflow was able to express relatively lower amount of KCNQ1, it was expected because of the complex transmembrane protein structure and challenges in incorporation to provide the overall stability.

Figure 1.

(A) Human KCNQ1100–370 topology depicting helices S1-S6. (B) Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel stained with Coomassie blue showing affinity purified KCNQ1 100–370 in DPC micelles, Lane 1: Marker, Lane 2: Purified KCNQ1100–370.

SDS-PAGE electrophoresis analysis was performed on purified KCNQ1100–370 to check the purity and integrity of Ni-NTA affinity purified protein. A protein band was observed ~26 kDa (Figure 1B) confirming the purity of the protein. To check robustness of the purification protocol, additional SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblot experiments were performed by running flow-through, wash and eluate fractions in the gel (supplementary Figure 1A). As expected, a major KCNQ1100–370 band was observed only with eluate fraction (supplementary Figure 1A) suggesting minimal protein loss during the purification steps. Western-blot experiment was carried out following the same setup as shown in supplementary Figure 1A to confirm the identity of expressed protein as KCNQ1100–370 (supplementary Figure 1B). Given that the KCNQ1100–370 sequence contained 10x-His-tag at the C-terminal end, an anti-His antibody was used to probe for KCNQ1100–370 protein (supplementary Figure 1B). The immunoblot showed a dominant band around ~26 kDa further confirming that the purified protein was KCNQ1100–370.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot experiments showed the successful overexpression of His-tagged KCNQ1100–370. Additional nano-LC-MS/MS based mass spectrometry experiments were performed to identify the peptides corresponding to human KCNQ1. The expressed protein was in gel digested to obtain tryptic peptides before MS injection. The MS data was searched against all species using the Swiss-Prot database to avoid any spurious protein identification. The false discovery rate (FDR) implemented in the search was 0.05. We successfully identified the peptides consistent with the human KCNQ1 protein (4 unique peptides with > 95% confidence interval) (Table 1 and supplementary File 1). Based on SDS-PAGE, immunoblot and MS experiments, we successfully confirmed the expression, purification and identification of human KCNQ1100–370 protein. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time when the KCNQ1 channel protein comprising all 6 TM helices of human KCNQ1 was expressed and purified successfully.

Table 1.

Nano-LC-MS/MS based identification of recombinant KCNQ1 after in gel digestion.

| Protein Accession | Name & Species | Peptides(95%) | Subcellular Location | Sequence Length | Mass Spectrometry | Entry Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sp|P51787|KCNQ1_HUMAN | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily KQT member 1 | 4 | Cell membrane | 676 | Triple TOF | Swiss Prot: v196 |

| OS=Homo sapiens GN=KCNQ1 | Multi-pass membrane protein |

Reconstitution of KCNQ1100–370 into DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG Vesicles

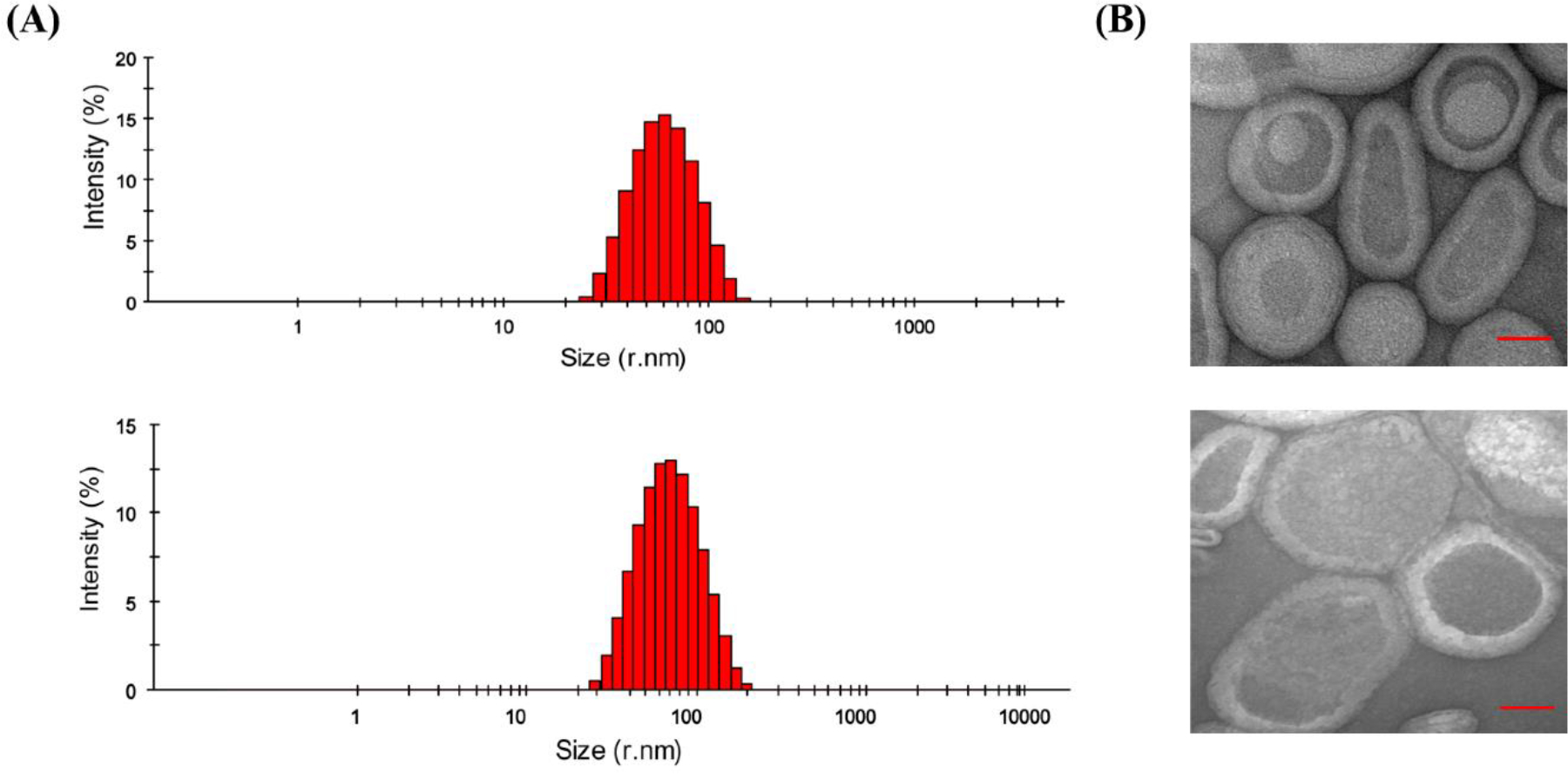

To generate homogeneously reconstituted KCNQ1100–370 in a lipid bilayer, DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG lipids (1:3:1) were used52,53. A combination of SM2 Bio-Beads and dialysis were used to ensure complete detergent removal. Initial DPC detergent removal was carried out at 4°C using SM2 Bio-Beads followed by 24 hr dialysis using 14kDa molecular weight cut off membrane. The homogeneity of the vesicles was confirmed by DLS. DLS data showed a uniform particle size distribution at room temperature, as shown in Figure 2A. The average particle size was ~60 nm for DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG (400:0) vesicles and ~80 nm for KCNQ1100–370 incorporated DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG (400:1) vesicles. The morphology of the vesicle preparation was visually inspected using TEM. Negative stain electron microscopy revealed uniformly sized vesicles in the both control and protein incorporated vesicles with smooth surface for empty vesicles. The regions of granularity and irregularities on the edges were observed in the protein incorporated vesicles indicating the presence of the protein in these vesicles.

Figure 2.

(A) DLS data of DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG (1:3:1) vesicles and with KCNQ1100–370 at L:P ratio 400:0 and 400:1 prepared using extrusion, and (B) the corresponding Negative-Stain TEM.

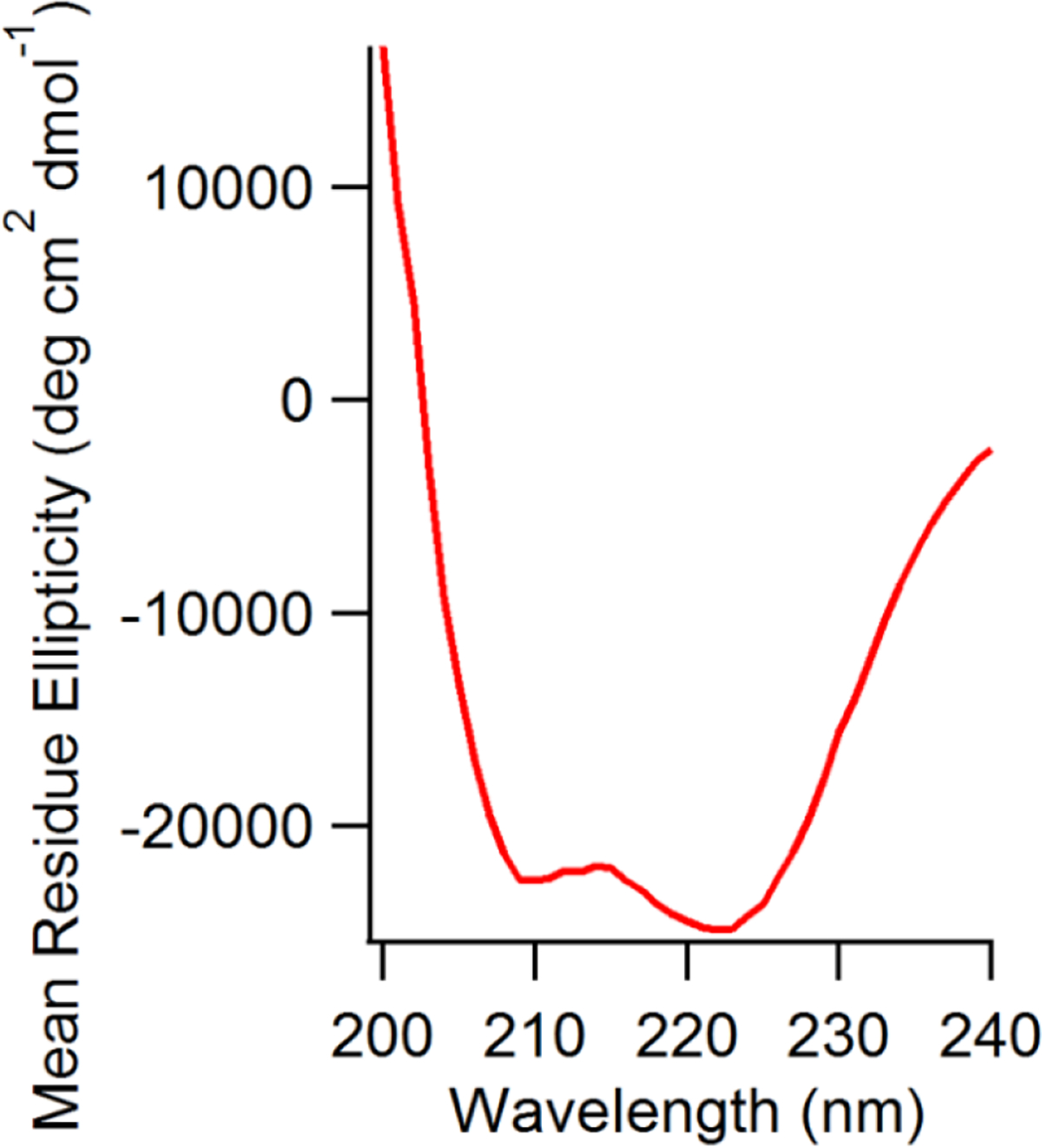

The circular dichroism spectrum of KCNQ1100–370 is characteristic for an α-helix with conspicuous troughs at 208 and 222 nm and a positive peak at 192 nm39–46. The CD measurements were carried out in 10 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.5 at 25°C. Due to the DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG lipids absorbing at lower wavelengths, the signal to noise at lower wavelength for vesicles was poor, therefore the data for vesicle sample is reported till 200 nm. Figure 3 depicts the CD data of KCNQ1100–370 in DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG vesicles at pH 7.5 and 296 K. CD experiments demonstrated a typical α-helical pattern in the vesicle environment39–46. Quantitative analysis of the CD data indicated helical content of 89% for KCNQ1100–370 reconstituted in lipid vesicles clearly indicating that KCNQ1100–370 adopts an ordered α-helical structure upon incorporation into a lipid bilayer.

Figure 3.

CD spectra of WT KCNQ1100–370 in DPPC/POPC/POPG vesicles, pH 7.5, 296 K.

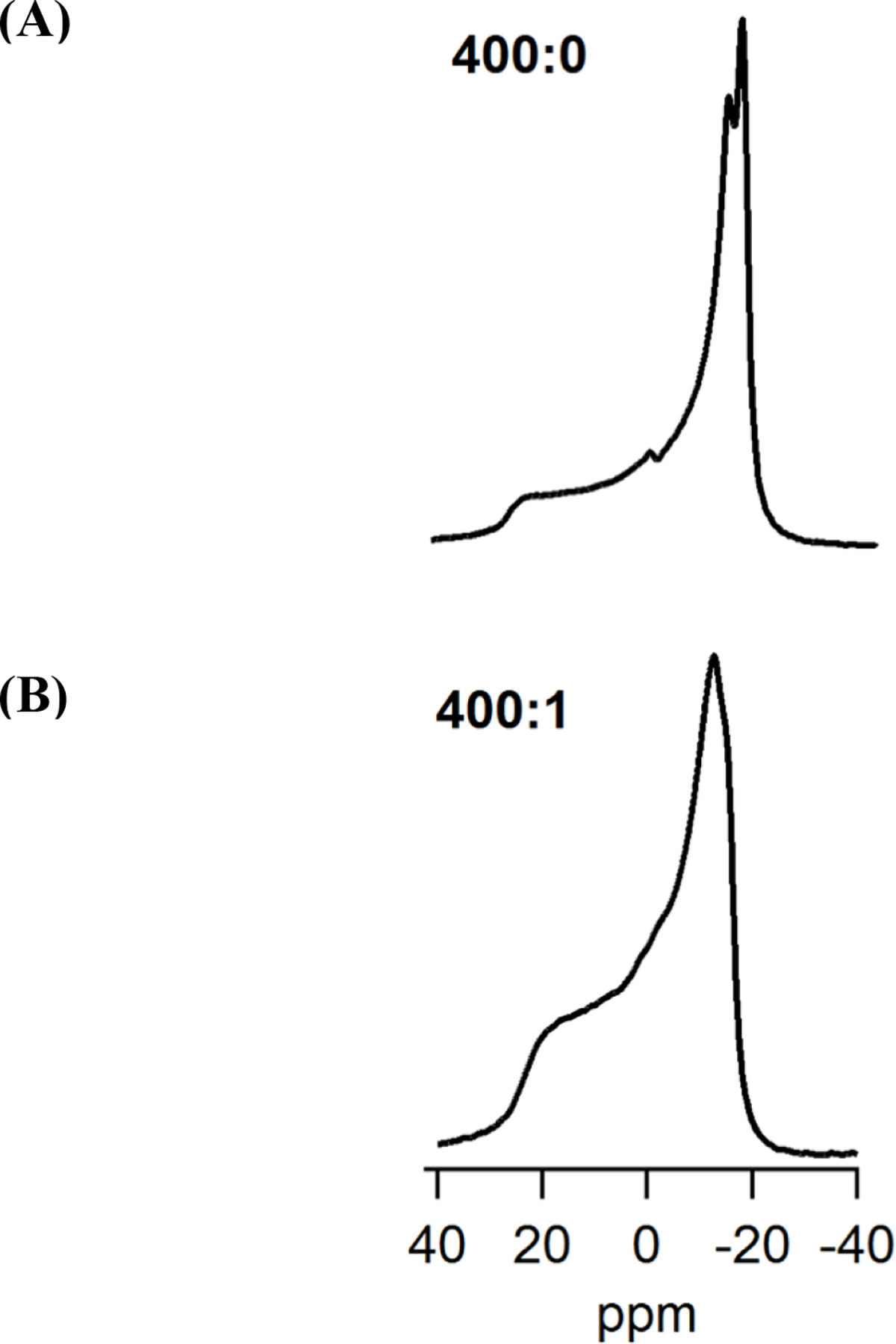

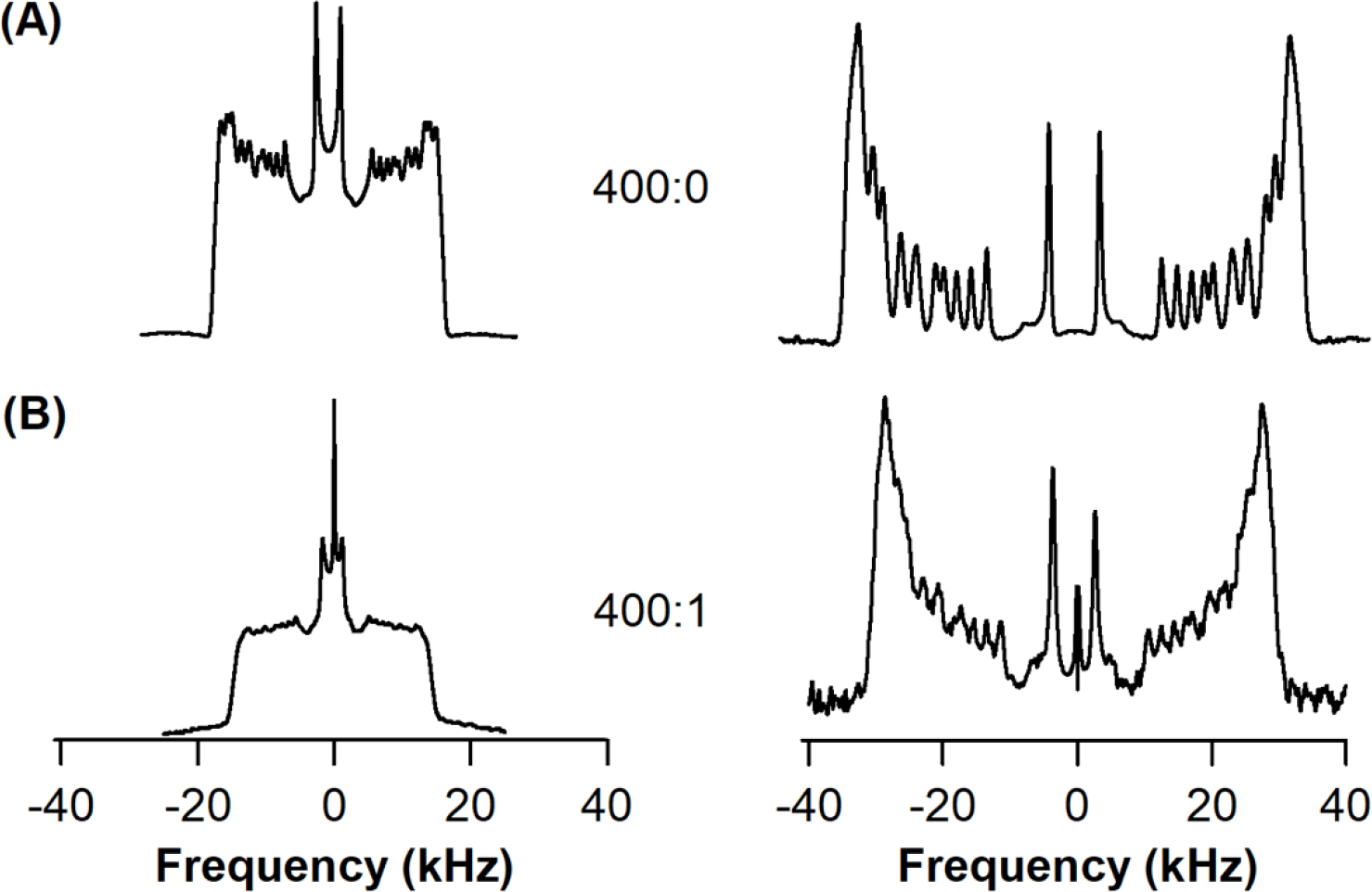

To confirm the interaction of KCNQ1100–370 with the phospholipid head groups of the membrane, the dynamic properties of the lipid bilayers upon KCNQ1100–370 incorporation were investigated using 31P solid-state NMR spectroscopy. The static 31P NMR spectra collected at 25°C displaying the perturbations of KCNQ1100–370 on the dynamics of lipid bilayered vesicles as a function of lipid/protein (L:P) ratio are shown in Figure 4. In the absence of protein and at 25°C the DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG spectra exhibited a typical motionally averaged, axially symmetric chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) of a phospholipid bilayer in the liquid crystalline phase (Lα).

Figure 4.

31P Solid state NMR spectra of (A) empty DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG vesicles (400:0), and (B) KCNQ1100–370 protein incorporated into DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG vesicles (400:1).

In the absence of the protein, 31P NMR spectra revealed two different peaks due to different CSAs for DPPC-d62/POPC and POPG52,53. The peaks for DPPC-d62 and POPC were not resolved due to similar CSA. The addition of KCNQ1100–370 caused a significant decrease in the CSA spectral linewidth35, when compared to empty DPPC/POPC/POPG (1:3:1) vesicles as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

31P NMR chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) and 2H quadrupolar splitting spectral width of empty DPPC/POPC/POPG vesicles (400:0) and with KCNQ1100–370 incorporated (400:1).

| Sample (L:P) | 31P CSA (ppm) | 2H Quad. Splitting (kHz) |

|---|---|---|

| 400:0 | 43.8 ± 1.0 | 30.6 ± 1.0 |

| 400:1 | 37.9 ± 1.0 | 29.6 ± 1.0 |

The 31P lineshape and CSA width data indicates an increase in the membrane surface fluidity upon addition of KCNQ1100–370 and consequently its interaction with the lipid bilayer. Similar reductions in CSA line width upon increasing protein concentration has been previously reported47–53. Overall, the 31P lineshape and reduction in the CSA line width show that the phospholipid head groups of the DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG are perturbed significantly upon addition of the protein, indicating that KCNQ1100–370 interacts with the phospholipid head groups of the DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG lipid bilayer.

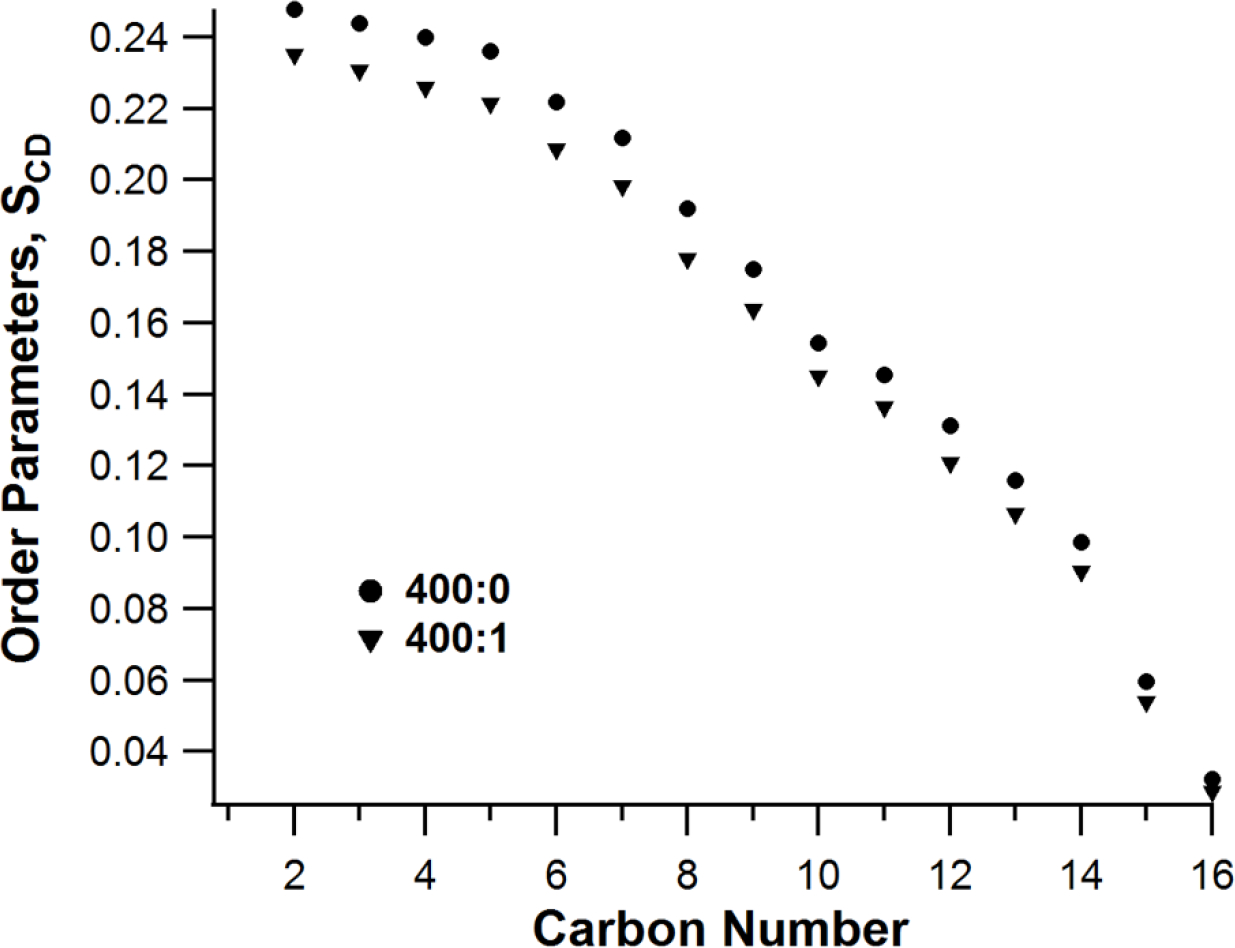

The effect of KCNQ1100–370 on the acyl chain dynamics and overall order within the DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG bilayer were studied using 2H solid-state NMR spectroscopy. The 2H quadrupolar splitting () and order parameters (SCD) were measured. The 2H NMR spectra of empty DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG and with KCNQ1100–370 incorporated in DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG bilayers at 25°C are presented in Figure 5. The 2H NMR spectra are characteristic of axially symmetric motions about randomly oriented phospholipid bilayer normal. The spectra reveal signals from different CD2 and one CD3 segment resulting in a quadrupolar powder pattern with the overall distance between the main peaks reflecting a characteristic quadrupolar splitting for every position in the acyl chain. A less constrained reorientation is representative of smaller splittings due to CD3 segment present at the methyl end of the acyl chain. For CD2 groups lying in the vicinity of the phospholipid head group, the motions are much more restricted resulting in larger quadrupole splittings. The overall spectral width for empty DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG vesicles and with KCNQ1100–370 at L:P ratio 400:0 and 400:1 are shown in Table 2. The decrease in spectral width along with a loss of resolution of spectra upon KCNQ1100–370 incorporation indicates an increase in the lipid bilayer fluidity further suggesting perturbations in the lipid acyl chains of the DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG.

Figure 5.

2H solid-state NMR spectra of (A) empty DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG vesicles (400:0), and (B) KCNQ1100–370 protein incorporated into DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG vesicles (400:1). The resulting dePaked data is shown in the right.

The 2H NMR powder pattern spectra were dePaked to deduce changes in the overall dynamics of acyl chains upon KCNQ1 100–370 incorporation. SCD order parameters were calculated using equation (1) where the quadrupolar splitting values were determined through dePaking of the original 2H NMR spectra as shown in Figure 5. 2H Quadrupolar splitting represents the average alignment of the C-D vector and reveal the position dependent dynamic averaging of the acyl chains in a bilayer. The overall decrease of order parameters for each CD2 moving further away from the glycerol backbone for empty DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG vesicles and with KCNQ1100–370 at L:P ratio 400:0 and 400:1 are shown in Figure 6. The motions are most restricted near the glycerol backbone and increase along the length of the acyl chain. The order parameter values range from 0.03 for the CD3 terminal methyl to 0.25 for the CD2 nearest to the glycerol backbone for DPPPC-d62/POPC/POPG vesicles. Upon addition of KCNQ1100–370 the order parameters at 25°C, as shown in Figure 6, indicate significant perturbations in the acyl chain carbon closer to the glycerol backbone.

Figure 6.

Order Parameters (SCD) for empty DPPC-d62/POPC/POPG vesicles and with KCNQ1100–370 at L:P ratio 400:0 and 400:1respectively.

Since 31P NMR revealed similar powder pattern with no isotropic component (η = 0) in both empty and KCNQ1100– 370 incorporated vesicles, it is inferred that the decrease in 2H quadrupolar splittings were not the result of protein-induced membrane curvature.

Conclusions

The study presented here describes in detail the expression, purification and biochemical and biophysical characterization of the human KCNQ1100–370 voltage gated potassium ion channel protein. The solid-state 31P and 2H NMR data clearly indicates the successful incorporation of KCNQ1100–370 and changes in the lipid dynamics upon lipid-protein interaction. Several studies have reported the structure and functional dynamics of Q1-VSD32,33,35. This study lays the groundwork for future studies involving in KCNQ1100–370 structure, topology, VSD-PD coupling and its interaction with KCNE1. The data presented in this study also describes a method to study a complex membrane protein like KCNQ1 in its native membrane like environment. This, along with other signaling lipids like PIP2 can form the basis for future studies involving the interaction of KCNQ1 and its role in Long-QT syndrome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Dr. Theresa Ramelot for her continuous support for the solid-state NMR instruments and data analysis. The authors thank the members of the Lorigan, Dabney-Smith and Charles R Sanders (research groups) for their valuable suggestions throughout the development of this manuscript. This work was generously supported by the NIGMS/NIH Maximizing Investigator’s Research Award (MIRA) R35 GM126935 award and a NSF CHE-1807131 grant (to Gary A Lorigan) and by RO1 HL122010 (to Charles R Sanders). Gary A. Lorigan would also like to acknowledge support from the John W. Steube Professorship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Sanders CR, Myers JK. Disease-related misassembly of membrane proteins. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 33 (2004) 25–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders CR, Nagy JK. Misfolding of membrane proteins in health and disease: the lady or the tiger? Curr Opin Struct Biol 10 (2000) 438–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dwivedi P, Greis KD Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor receptor signaling in severe congenital neutropenia, chronic neutrophilic leukemia, and related malignancies. Exp Hematol 46 (2017) 9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu FH, Catterall WA. The VGL-chanome: A protein superfamily specialized for electrical signaling and ionic homeostasis. Sci STKE 5 (2004) re15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catterall WA. Structure and function of voltage-gated ion channels. Annual Review of Biochemstry 64 (1995) 493–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bezanilla F, Perozo E. The voltage sensor and gate in ion channels. Advances in Protein Chemistry 63 (2003) 211–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacKinnon R Potassium channels. FEBS Letters 555 (2003) 62–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbott GW Biology of the KCNQ1 potassium channel. New J. Sci. (2014) No. e237431. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jespersen T, Grunnet M, and Olesen SP The KCNQ1 potassium channel: from gene to physiological function. Physiology 20 (2005) 408–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanguinetti MC, Curran ME, Zou A, Shen J, Spector PS, Atkinson DL, Keating MT. Coassembly of KvLQT1 and minK (Isk) protein to form cardiac Iks potassium channel. Nature 384 (1996) 80–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakajo K, Kubo Y KCNQ1 channel modulation by KCNE proteins via the voltage sensing domain. J. Physiol (2015) 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barhanin J, Lesage F, Guillemare E, Fink M, Lazdunski M, Romey G. KvLQT1 and IsK (mink) proteins associate to form the Iks cardiac potassium current. Nature 384 (1996) 78–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang KW, Tai KK, Goldstein SA. MinK residues line a potassium channel pore. Neuron 16 (1996) 571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiron C, Campuzano O, Perez-Serra A, Mademont I, Coll M, Allegue C, Iglesias A, Partemi S, Striano P, Oliva A, Brugada R. Further evidence of the association between LQT syndrome and epilepsy in family with KCNQ1 pathogenic variant. Seizure 25 (2015) 65–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldman AM, Glasscock E, Yoo J, Chen TT, Klassen TL, Noebels JL. Arrhythmia in heart and brain: KCNQ1 mutations link epilepsy and sudden unexplained death. Sci Transl Med 1 (2009) 2ra6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dworakowska B, Dolowy K Ion channels-related diseases. Acta Biochi. Pol. 47 (2000) 685–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neyroud N, Tesson F, Denjoy I, Leibovici M, Donger C, Barhanin J, Faure S, Gary F, Coumel P, Petit C, Schwartz K, Guicheney P. A novel mutation in the potassium channel gene KVLQT1 causes the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen cardioauditory syndrome. Nat Gen 15 (1997) 186–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niemeyer BA, Mery L, Zawar C, Suckow A, Monje F, Pardo LA, Stuhmer W, Flockerzi V, Hoth M Ion channels in health and disease. EMBO rep. 2 (2001) 568–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maljevic S, Wuttke TV, Seebohm G, Lerche H KV7 channelopathies. Pfluegers Arch. 460 (2010) 277–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peroz D, Rodriguez N, Choveau F, Baro I, Merot J, and Loussouarn G Kv7.1 (KCNQ1) properties and channelopathies. J. Physiol. 586 (2008) 1785–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith JA, Vanoye CG, George AL, Meiler J, and Sanders CR Structural models for the KCNQ1 voltage-gated potassium channel. Biochemistry 46 (2007) 14141–14152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang WP, Levesque PC, Little WA, Conder ML, Shalaby FY, and Blanar MA KvLQT1, a voltage-gated potassium channel responsible for human cardiac arrhythmias. Porc Natl Acad Sci USA 94 (1997) 4017–4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boulet IR, Labro AJ, Raes AL, and Snyders DJ Role of S6 C-terminus in KCNQ1 channel gating. J Physiol 585 (pt. 2) (2007) 325–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu Y, Wang Y, Meng XY, Zhang M, Cui M, and Tseng GN Building KCNQ1/KCNE1 channel models and probing their interactions by molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys J 105 (2013) 2461–2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haitin Y, Yisharel I, Malka E, Schamgar L, Schottelndreier H, Peretz A, Paas Y, and Attali B S1 constrains S4 in the voltage sensor domain of Kv7.1 K+ channels. PLOS One 3 (2008) e1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banerjee A, Lee A, Campbell E, and Mackinnon R Structure of a pore-blocking toxin in complex with a eukaryotic voltage-dependent K+ channel. eLife 2 (2013) e00594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva JR, Pan H, Wu D, Nekouzadeh A, Decker KF, Cui J, Baker NA, Sept D, and Rudy Y A multiscale model linking ion channel molecular dynamics and electrostatics to the cardiac action potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106 (2009) 11102–11106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun J, and MacKinnon R Cryo-EM structure of a KCNQ1/CaM complex reveals insights into congenital long QT syndrome. Cell 169 (2017) 1042–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaydman MA, Kasimova MA, McFarland K, Beller Z, Hou P, Kinser HE, Liang H, Zhang G, Shi J, Tarek M, Cui J Domain–domain interactions determine the gating, permeation, pharmacology, and subunit modulation of the IKs ion channel. Elife (2014) 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osteen JD, Barro-Soria R, Robey S, Sampson, Kass RS, and Larsson PH. Allosteric gating mechanism underlies the flexible gating of KCNQ1 potassium channels. Prot Natl Acad Sci USA 109 (2012) 7103–7108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hou P, Eldstrom J, Shi J, Zhong L, McFarland K, Gao Y, Fedida D, and Cui J Inactivation of KCNQ1 potassium channles reveals dynamic coupling between voltage sensing and pore opening. Nat Commum 8 (2017) 1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang H, Kuenze G, Smith JA, Taylor KC, Duran AM, Hadziselimovic A, Meiler J, Vanoye CG, George AL Jr., and Sanders CR Mechanisms of KCNQ1 channel dysfunction in long QT syndrome involving voltage sensor domain mutations. Sci. Adv. 4 (2018) eaar2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng D, Kim JH, Kroncke BM, Law CL, Xia Y, Droege KD, van Horn WD, Vanoye CG and Sanders C Purification and structural study of the voltage-sensor domain of the human KCNQ1 potassium ion channel. Biochemistry 53 (2014) 2032–2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiener R, Haitin Y, Shamgar L, Fernandez-Alonso MC, Martos A, Chomsky-Hecht O, Rivas G, Attali B, and Hirsch JA The KCNQ1 (Kv7.1) COOH terminus, a multilayered scaffold for subunit assembly and protein interaction. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 283 (pt. 9) (2007) 5815–5830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dixit G, Sahu ID, Reynolds WD, Wadsworth TM, Harding BD, Jaycox CK, Dabney-Smith C, Sanders CR, and Lorigan GA Probing the dynamics and structural topology of the reconstituted human KCNQ1 voltage sensor domain (Q1-VSD) in lipid bilayers using electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry 58 (2019) 965–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eismann T, Huber N, Shin T, Kuboki S, Galloway E, Wyder M, Edwards MJ, Greis KD, Shertzer HG, Fisher AB, Lentsch AB Peroxiredoxin-6 Protects Against Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Liver Injury During Ischemia/Reperfusion in Mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 296(2) (2009) G266–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dwivedi P, Muench DE, Wagner M, Azam M, Grimes HL, and Greis KD Time resolved quantitative phospho-tyrosine analysis reveals Bruton;s tyrosine kinase mediated signaling downstream of the mutated granulocyte-colony stimulating factor receptors. Leukemia 33 (2019) 75–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dwivedi P, Muench DE, Wagner M, Azam M, Grimes HL, and Greis KD Phospho serine and threonine analysis of normal and mutated granulocyte colony stimulating factor receptors. Sci Data 6 (2019) 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Findlay EH, Booth PJ The folding, stability and function of lactose permease differ in their dependence on bilayer lipid composition. Scientific Reports 7 (2017) 13056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitmore L, Wallace BA DICHROWEB, an online server for protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopic data. Nucleic Acids Res 32 (2004) W668–W673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whitmore L, Wallace BA Protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopy: Methods and reference databases. Biopolymers 89 (2008) 392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park K, Perczel A, Fasman GD Differentiation between transmembrane helices and peripheral helices by deconvolution of circular dichroism spectra of membrane proteins. Protein Science 1 (1992) 1032–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mercer EAJ, Abbott GW, Brazier SP, Ramesh B, Haris PI, Srai SKS Synthetic putative transmembrane region of minimal potassium channel protein (minK) adopts an alpha-helical conformation in phospholipid membranes. Biochemical Journal 325 (1997) 475–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corbin J, Methot N, Wang HH, Baenziger JE, Blanton MP Secondary structure analysis of individual transmembrane segments of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor by circular dichroism and fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. The Journal of Biological chemistry 273 (1998) 771–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dwivedi P, Rodriguez J, Ibe NU, Weers PM. Deletion of the N- and C-terminal helix of apolipophorin III to create a four-helix bundle protein. Biochemistry 55 (26) (2016) 3607–3615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Larsen AN, Sorensen KK, Johansen NT, Martel A, Kirkensgaard JJ, Jensen KJ, Arleth L, and Midtgaard SR Dimeric peptides with three different linkers self-assemble with phospholipids to form peptide nanodiscs that stabilize membrane proteins. Soft Matter 12 (2016) 5937–5949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shadi A-B, Phospholamban Lorigan G. A. and its phosphorylated form interact differently with lipid bilayers: A 31P, 2H and 13C solid-state NMR spectroscopic study. Biochemistry 45 (2006) 13312–13322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seeling J 31P Nuclear magnetic resonance and the head group structure of phospholipids in membranes. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 515 (1978) 105–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garner J, Inglis SR, Hook J, Separovic F, and Harding MM A solid-state NMR study of the interaction with fish antifreeze proteins with phospholipid membranes. Eur Biophys J 37 (2008) 1031–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salnikov ES, and Bechinger B The membrane interactions of antimicrobial peptides revealed by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 165 (2012) 282–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang L, Liu L, Maltsev S, Lorigan GA, and Dabney-Smith C Investigating the interaction between peptides of the amphipathic helix of Hcf106 and the phospholipid bilayer by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta 1838 (2014) 413–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roldan N, Perez-Gil J, Morrow MR, and Garcia-Alvarez B Divide & Conquer: Surfactant protein SP-C and cholesterol modulate phase segregation in lung surfactant. Biophysical Journal 113 (2017) 847–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Antharam VC, Farver RS, Kuznetsova A, Sippel KH, Mills FD, Elliott DW, Sternin E, and Long JR Interactions of the C-terminus of pulmonary surfactant B with lipid bilayers are modulated by acyl chain saturation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1778(11) (2008) 2544–2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Molugu TR, Xu X, Leftin A, Lope-Piedrafita S, Martinez GV, Petrache HI, and Brown MF Solid-state deuterium NMR spectroscopy of membranes. Modern Magnetic Resonance, (2017) pp.1–23. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-28275-6_89-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harding BD, Dixit G, Burridge KM, Sahu ID, Dabney-Smith C, Edelmann RE, Konkolewicz D, and Lorigan GA Characterizing the structure of styrene-maleic acid copolymer-lipid nanoparticles (SMALPs) using RAFT polymerization for membrane protein spectroscopic studies. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 218 (2018) 65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.