Abstract

Background:

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a rare condition leading to morbidity and mortality. Liver transplantation (LT) is often required, but patients are not always listed for LT. There is a lack of data regarding outcomes in these patients. Our aim is to describe outcomes of patients with ALF not listed for LT and to compare this with those listed for LT.

Methods:

Retrospective analysis of all nonlisted patients with ALF enrolled in the Acute Liver Failure Study Group (ALFSG) registry between 1998 and 2018. The primary outcome was 21-day mortality. Multivariable logistic regression was done to identify factors associated with 21-day mortality. The comparison was then made with patients with ALF listed for LT.

Results:

A total of 1672 patients with ALF were not listed for LT. The median age was 41 (IQR: 30–54). Three hundred seventy-one (28.9%) patients were too sick to list. The most common etiology was acetaminophen toxicity (54.8%). Five hundred fifty-eight (35.7%) patients died at 21 days. After adjusting for relevant covariates, King’s College Criteria (adjusted odds ratio: 3.17, CI 2.23–4.51), mechanical ventilation (adjusted odds ratio: 1.53, CI: 1.01–2.33), and vasopressors (adjusted odds ratio: 2.10, CI: 1.43–3.08) (p < 0.05 for all) were independently associated with 21-day mortality. Compared to listed patients, nonlisted patients had higher mortality (35.7% vs. 24.3%). Patients deemed not sick enough had greater than 95% survival, while those deemed too sick still had >30% survival.

Conclusions:

Despite no LT, the majority of patients were alive at 21 days. Survival was lower in nonlisted patients. Clinicians are more accurate in deeming patients not sick enough to require LT as opposed to deeming patients too sick to survive.

Keywords: acute liver failure, ALFSG prognostic index, liver transplantation, prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a rare syndrome that occurs following a severe insult to hepatocytes in a patient without prior underlying chronic liver disease.1 Within at least 26 weeks of the insult, often much less, rapid deterioration of hepatic function results in jaundice, coagulopathy, and HE followed by multiorgan failure (MOF).2 ALF is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Clinical outcomes generally depend on the etiology of ALF and range from spontaneous recovery to the need for emergent liver transplantation (LT) to mortality.3 Overall, mortality is around 30%.4,5

Treatment of ALF is mainly supportive and aims to prevent and control cerebral edema, correct metabolic derangements, and maintain hemodynamic stability.6,7 Over the past 2 decades, ALF outcomes have steadily improved, especially for acetaminophen (APAP)-induced ALF.8 This is mainly due to improved recognition and intensive care unit therapies. Prompt N-acetylcysteine usage for both APAP and non-APAP–induced ALF, early initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), and use of high-volume plasma exchange have all improved survival in patients with ALF.9,10,11,12,13

However, a number of patients fail to recover with maximal medical therapies and require emergent LT. Despite being critically ill at the time of transplant, 1-year and 3-year post-LT survival is still as high as 91% and 90%, respectively.4 Even when early consideration of LT occurs, certain factors may preclude patients from being listed for LT, including severe MOF and a variety of psychosocial factors.14,15

Currently, there is a paucity of epidemiologic data on outcomes of patients with ALF not listed for LT. Therefore, our primary objective was to analyze prospectively collected ALF patient data from the multicenter Acute Liver Failure Study Group (ALFSG) registry between 1998 and 2018 to evaluate factors leading to nonlisting of patients with ALF, outcomes of these patients, including 21-day survival, and lastly, factors associated with mortality in nonlisted patients with ALF. We then compared outcomes of nonlisted patients with ALF to those who were listed for LT to determine how accurately patients deemed either too well or too sick for LT are prognosticated.

METHODS

Study design

We performed a retrospective cohort study of all patients with ALF prospectively enrolled in the ALFSG registry between January 1998 and December 2018 who were evaluated but not listed for LT (n = 1672). All patients not listed for LT had an evaluation for LT, and none passed away before LT waitlist decision. We included all nonlisted patients with outcomes data (n = 1564). We then added patients listed for LT (n = 934) to our study for comparison to nonlisted patients. A detailed report of the listed patients in this same registry has been previously published.16 All respective institutional review boards/health research ethics boards at participating sites (tertiary LT referral centers) within the ALFSG provided approval for the study’s protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant or next of kin (in cases of HE at the time of enrollment). All research procedures were conducted according to the principles of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Therapeutic interventions and monitoring were implemented according to participating institutional standards of care. Criteria for listing and performing LT were those utilized at participating centers. This study was written according to the STROBE guideline for reporting retrospective studies.17

Participants

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) evidence of ALF according to the enrollment criteria of the ALFSG (see operational definitions), (2) participant age ≥18 years, and (3) not listed for LT. Patients listed for liver transplants were also included to allow comparison to nonlisted patients. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) evidence of cirrhosis/acute-on-chronic liver failure and (2) severe acute liver injury only defined by the presence of coagulopathy with an international normalized ratio (INR) ≥1.5, illness onset <26 weeks from hepatic injury, and no presence of HE.

Operational definitions

ALF was defined by the following criteria: (1) HE of any degree (West Haven Criteria), (2) evidence of coagulopathy with an INR ≥1.5, (3) illness onset <26 weeks from hepatic injury, and (4) no evidence of cirrhosis. The King’s College Criteria (KCC) qualifies poor prognosis in ALF: for APAP-induced ALF, KCC is defined as either (1) arterial pH <7.3, or (2) all 3 of (i) INR >6.5, (ii) creatinine >300 μmol/L (3.4 mg/dL), and (iii) the presence of grade 3/4 HE; for non-APAP–induced ALF, KCC is defined as either (1) INR >6.5, or (2) 3 of (i) poor prognosis etiology, (ii) time from jaundice to HE >7 days, (iii) age<10 or >40, iv) INR >3.5, and (v) serum bilirubin >17 mg/dL.18 The Acute Liver Failure Study Group Prognostic Index (ALFSG-PI) is an internally validated mathematical model that predicts 21-day transplant-free survival (TFS) of patients with ALF using hospital admission data and it has been previously described.19 The MELD is calculated as follows: [3.78 × ln(bilirubin in mg/dL) + 11.2 × ln(INR) + 9.57 × ln(creatinine in mg/dL) + 6.43]; a serum creatinine value of 354 μmol/L (4 mg/dL) is substituted for dialyzed patients.20 Renal replacement therapy (RRT) included both intermittent hemodialysis and CRRT. Patients receiving CRRT and intermittent hemodialysis during days 1–7 were coded accordingly.

Data collection

Patients were enrolled prospectively into the ALFSG registry (data coordinating centers at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 1998–2010 and the Medical University of South Carolina, 2010–2018) and analyzed retrospectively. Detailed demographic, clinical, and outcome data on patients with ALF were recorded in an electronic database with the observation period beginning at the time of study enrollment. Baseline data on those with ALF who were not listed for LT and those who were listed for LT included demographic features, etiology of ALF, blood biochemistries, HE grade, and MELD score. Additional data including organ support requirements (invasive mechanical ventilation and oxygenation status [PaO2/FiO2]), vasopressors, and RRT were recorded. Clinical outcomes included intensive care unit complications, causes of death, and overall 21-day survival. The primary outcome was overall 21-day survival.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata (version 18.0; StataCorp). Continuous variables were reported as medians with IQR following testing for normality and compared using the Student t test (normal distribution) and Wilcoxon Rank sum test (nonparametric variables). Categorical variables were reported as numbers and percentages and were compared using the chi-squared test. To study the association between overall 21-day survival and nonlisting for ALF, multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed. Covariates were included based on their significance in the univariable regression analysis (p < 0.20). Collinear variables were excluded where appropriate. Results were reported as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% CIs. Model performance was assessed using the c-statistic (AUROC). We used a statistical significance threshold of 0.05 for 2-tailed p values.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of nonlisted patients

In total, 1672 patients (64%) with ALF who were not listed for LT at any time were identified in the ALFSG registry. Out of those, 1564 had data on survival. Median (IQR) age was 42 (30–54) years, and 497 (31.8%) were male. Around half of the patients (51.4%) were enrolled in the recent era (2009–2018). APAP was the etiology of ALF in 843 (53.9%) patients. Reasons recorded for not listing for LT included patients not being sick enough (33.3%), patients having psychosocial contraindications (28.4%), as well as patients being too sick (29.8%), which included irreversible brain injury (1.6%) and sepsis (3.0%). Nonlisted patients had median MELD of 36 (26–44) and ALFSG-PI of 36.8% (12.4%–69.0%), with 948 (61.8%) patients having high-grade HE and 324 (20.7%) patients meeting KCC. Regarding organ supports, 905 (57.9%) nonlisted patients required mechanical ventilation, 540 (34.5%) patients needed vasopressor support, and 520 (33.3%) patients required RRT, with 244 (15.6%) receiving CRRT. Demographic data for nonlisted patients with ALF are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and outcomes of 1564 ALF patients not listed for LT

| Overall (N = 1564) | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | Number (%) or median (IQR) | |

| Age | 1564 | 42 (30–54) |

| Year of enrollment | ||

| 1998–2008 | 1564 | 760 (48.6) |

| 2009–2018 | 1564 | 804 (51.4) |

| Sex (male) | 1564 | 497 (31.8) |

| Reason declined for LT | ||

| Not sick enough | 1217 | 405 (33.3) |

| Psychosocial | 1217 | 346 (28.4) |

| Too sick | 1217 | 362 (29.8) |

| Irreversible brain injury | 20 (1.6) | |

| Sepsis | 37 (3.0) | |

| Etiology | ||

| APAP | 1564 | 843 (53.9) |

| DILI | 1564 | 130 (8.3) |

| HBV | 1564 | 80 (5.1) |

| AIH | 1564 | 54 (3.5) |

| Indeterminate | 1564 | 122 (7.8) |

| Other | 1564 | 90 (5.8) |

| King’s College Criteria | 1564 | 324 (20.7) |

| Highest MELD (during 7 d) | 1550 | 36 (26–44) |

| Coma Grade 3/4 (highest during days 1–7) | 1535 | 948 (61.8) |

| ALFSG Prognostic Index (highest days 1–7) | 1521 | 36.8% (12.4%–69.0%) |

| Organ support (days 1–7) | ||

| Mechanical ventilation | 1564 | 905 (57.9) |

| Vasopressors | 1564 | 540 (34.5) |

| Renal replacement therapy | 1564 | 520 (33.3) |

| Hemodialysis | 1564 | 334 (21.4) |

| CVVH | 1564 | 244 (15.6) |

| Admission biochemistry | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 1542 | 10.8 (9.4–12.3) |

| White blood cells (109/L) | 1541 | 9.8 (6.6–14.6) |

| Platelets (109/L) | 1534 | 119 (74–179) |

| INR | 1526 | 2.6 (1.9–4.0) |

| ALT (IU/L) | 1530 | 2344 (830–4620) |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1532 | 5.3 (3.0–11.2) |

| pH | 1152 | 7.41 (7.34–7.47) |

| Ammonia (venous) (μmol/L) | 592 | 89 (58–140) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1548 | 1.8 (0.9–3.2) |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 911 | 3.7 (2.2–7.2) |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 1336 | 3 (2.0–4.4) |

| ICP therapies (days 1–7) | ||

| ICP monitor | 1474 | 79 (5.4) |

| Mannitol | 1564 | 197 (12.6) |

| Barbiturate | 1564 | 76 (4.9) |

| Hypothermia | 1564 | 71 (4.5) |

| Sedatives | 1564 | 902 (57.7) |

| Blood products (days 1–7) | ||

| Red blood cells | 1564 | 433 (27.7) |

| Fresh frozen plasma | 1564 | 640 (40.9) |

| Platelets | 1564 | 272 (17.4) |

| ICU complications (days 1–7) | ||

| Seizures | 1564 | 86 (5.5) |

| Arrhythmia | 1564 | 340 (21.7) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 1564 | 144 (9.2) |

| Abnormal chest x-ray | 844 | 556 (65.9) |

| Bacteremia/blood stream infection | 1564 | 227 (14.5) |

| Intra-study NAC | ||

| i.v. | 1564 | 1029 (65.8) |

| Oral | 1564 | 658 (42.1) |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | 1564 | 645 (41.2) |

| Overdose intent (IF APAP) | ||

| Suicide attempt | 897 | 327 (36.5) |

| Unintentional | 897 | 454 (50.6) |

| Unknown | 897 | 116 (12.9) |

| Alcohol use | ||

| <7 drinks/wk | 638 | 463 (72.6) |

| >=7 drinks/wk | 638 | 175 (27.4) |

| Intravenous drug use | 1549 | 119 (7.7) |

| Death (days 1–21) | 1564 | 558 (35.7) |

| Cause of death | ||

| Multiorgan failure | 1297 | 235 (18.1) |

| Cerebral edema | 1297 | 80 (6.2) |

| Unknown | 1297 | 84 (6.5) |

| Outcome (day 21) | ||

| Survival | 1564 | 1006 (64.3) |

| Death | 1564 | 558 (35.7) |

Abbreviations: AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALF, acute liver failure; ALFSG, Acute Liver Failure Study Group; APAP, acetaminophen; CVVH, continuous veno-venous hemofiltration; ICP, intracranial pressure; ICU, intensive care unit; INR, international normalized ratio; i.v., intravenous; LT, liver transplantation; NAC, N-acetylcysteine.

Outcomes of nonlisted patients

Death at 21 days post-enrollment occurred in 558 (35.7%) of nonlisted patients, with 235 (18.1%) patients dying from MOF and 80 (6.2%) patients dying from cerebral edema. When comparing nonlisted survivors to nonsurvivors, survivors were younger (39 vs. 46 y of age, p < 0.001), had higher APAP etiology rates (63.1% vs. 37.3%, p < 0.001), lower KCC rates (9.2% vs. 41.4%, p < 0.001), lower high-grade HE rates (48.8% vs. 85.2%, p < 0.001), and had higher ALFSG-PI (53.9% vs. 11.4%, p < 0.001). Nonlisted ALF survivors required less mechanical ventilation (46.2% vs. 78.9%, p < 0.001), less vasopressor use (19.5% vs. 61.6%, p < 0.001), and less RRT (28.7% vs. 41.4%, p < 0.001). Survivors were more likely to not be listed for not being sick enough (48.6% vs. 4.1%, p < 0.001) and less likely to not be listed for being too sick (15.5% vs. 56.8%, p < 0.001). Of the patients who died, 4.1% were deemed not sick enough to list for LT. Of the patients who survived, 15.5% were considered too sick to survive. A comparison of nonlisted ALF survivors to nonsurvivors is described in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Demographics of 1564 patients with ALF not listed for LT stratified based on overall 21-day survival

| Alive at day 21 (N = 1006) | Deceased at day 21 (N = 558) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | p | |||

| Age | 1006 | 39 (29–51) | 558 | 46 (34–59) | <0.001 |

| Year of enrollment | 1006 | 558 | 0.104 | ||

| 1998–2008 | 1006 | 475 (47.2%) | 558 | 285 (51.1%) | 0.144 |

| 2009–2018 | 1006 | 531 (52.8%) | 558 | 273 (48.9%) | 0.144 |

| Sex (male) | 1006 | 294 (29.2%) | 558 | 203 (36.4%) | 0.004 |

| Reason declined for LT | |||||

| Not sick enough | 798 | 388 (48.6%) | 419 | 17 (4.1%) | <0.001 |

| Psychosocial | 798 | 240 (30.1%) | 419 | 106 (25.3%) | 0.079 |

| Too sick | 798 | 124 (15.5%) | 419 | 238 (56.8%) | <0.001 |

| Irreversible brain injury | 798 | 1 (0.1%) | 419 | 19 (4.5%) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 798 | 13 (1.6%) | 419 | 24 (5.7%) | <0.001 |

| Etiology (we will get all the etiology information) | |||||

| APAP | 1006 | 635 (63.1%) | 558 | 208 (37.3%) | <0.001 |

| DILI | 1006 | 71 (7.1%) | 558 | 59 (10.6%) | 0.016 |

| HBV | 1006 | 29 (2.9%) | 558 | 51 (9.1%) | <0.001 |

| AIH | 1006 | 23 (2.3%) | 558 | 31 (5.6%) | <0.001 |

| Indeterminate | 1006 | 54 (5.4%) | 558 | 68 (12.2%) | <0.001 |

| Other | 1006 | 28 (2.8%) | 558 | 62 (11.1%) | <0.001 |

| King’s College Criteria | 1006 | 93 (9.2%) | 558 | 231 (41.4%) | <0.001 |

| Highest MELD (during 7 d) | 1003 | 32 (23–40) | 547 | 42 (34–49) | <0.001 |

| Coma Grade 3/4 (highest during days 1–7) | 988 | 482 (48.8%) | 547 | 466 (85.2%) | <0.001 |

| ALFSG Prognostic Index (highest days 1–7) | 985 | 53.9% (29.7%–80.7%) | 536 | 11.4% (4.3%–26.0%) | <0.001 |

| Organ support (days 1–7) | |||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 1,006 | 465 (46.2%) | 558 | 440 (78.9%) | <0.001 |

| Vasopressors | 1,006 | 196 (19.5%) | 558 | 344 (61.6%) | <0.001 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 1,006 | 289 (28.7%) | 558 | 231 (41.4%) | <0.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 1,006 | 197 (19.6%) | 558 | 137 (24.6%) | 0.022 |

| CVVH | 1,006 | 131 (13.0%) | 558 | 113 (20.3%) | <0.001 |

| Admission biochemistry | |||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 991 | 10.9 (9.5–12.6) | 551 | 10.4 (9.1–12.0) | <0.001 |

| White blood cells (109/L) | 991 | 9.3 (6.4–13.6) | 550 | 11.0 (7.3–16.6) | <0.001 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 986 | 127 (85–185) | 548 | 103 (60–160) | <0.001 |

| INR | 984 | 2.4 (1.8–3.5) | 542 | 3.1 (2.3–4.8) | <0.001 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 988 | 2701 (1278–4997) | 542 | 1423 (468–3971) | <0.001 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 986 | 4.5 (2.4–7.9) | 546 | 8.6 (4.1–20.1) | <0.001 |

| pH | 728 | 7.42 (7.36–7.47) | 424 | 7.39 (7.29–7.46) | <0.001 |

| Ammonia (venous) (μmol/L) | 388 | 80 (55–122) | 204 | 112 (72–174) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 997 | 1.5 (0.8–3.0) | 551 | 2.3 (1.3–3.6) | <0.001 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 583 | 2.7 (1.8–4.8) | 328 | 6.8 (4.0–11.7) | <0.001 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 864 | 2.7 (1.8–3.7) | 472 | 4.0 (2.7–5.9) | <0.001 |

| ICP therapies (days 1–7) | |||||

| ICP monitor | 953 | 41 (4.3%) | 521 | 38 (7.3%) | 0.015 |

| Mannitol | 1006 | 78 (7.8%) | 558 | 119 (21.3%) | <0.001 |

| Barbiturate | 1006 | 29 (2.9%) | 558 | 47 (8.4%) | <0.001 |

| Hypothermia | 1006 | 34 (3.4%) | 558 | 37 (6.6%) | 0.003 |

| Sedatives | 1006 | 516 (51.3%) | 558 | 386 (69.2%) | <0.001 |

| Blood products (days 1–7) | |||||

| Red blood cells | 1006 | 227 (22.6%) | 558 | 206 (36.9%) | <0.001 |

| Fresh frozen plasma | 1006 | 317 (31.5%) | 558 | 323 (57.9%) | <0.001 |

| Platelets | 1006 | 129 (12.8%) | 558 | 143 (25.6%) | <0.001 |

| ICU complications (days 1–7) | |||||

| Seizures | 1006 | 32 (3.2%) | 558 | 54 (9.7%) | <0.001 |

| Arrhythmia | 1006 | 177 (17.6%) | 558 | 163 (29.2%) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 1006 | 61 (6.1%) | 558 | 83 (14.9%) | <0.001 |

| Abnormal chest x-ray | 473 | 282 (59.6%) | 371 | 274 (73.6%) | <0.001 |

| Bacteremia/blood stream infection | 1006 | 148 (14.7%) | 558 | 79 (14.2%) | 0.766 |

| Intra-study NAC | |||||

| i.v. | 1006 | 699 (69.5%) | 558 | 330 (59.1%) | <0.001 |

| Oral | 1006 | 458 (45.5%) | 558 | 200 (35.8%) | <0.001 |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | 1006 | 467 (46.4%) | 558 | 178 (31.9% | <0.001 |

| Overdose intent (IF APAP) | |||||

| Suicide attempt | 586 | 245 (41.8%) | 195 | 82 (42.1%) | 0.953 |

| Unintentional | 586 | 341 (58.2%) | 195 | 113 (58.0% | 0.953 |

| Unknown | 659 | 73 (11.1%) | 238 | 43 (18.1%) | 0.006 |

| Alcohol use | |||||

| <7 drinks/wk | 428 | 302 (70.6%) | 210 | 161 (76.7%) | 0.104 |

| >=7 drinks/wk | 428 | 126 (29.4%) | 210 | 49 (23.3%) | 0.104 |

| Intravenous drug use | 999 | 96 (9.6%) | 550 | 23 (4.2%) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALF, acute liver failure; ALFSG, Acute Liver Failure Study Group; APAP, acetaminophen; CVVH, continuous veno-venous hemofiltration; ICP, intracranial pressure; ICU, intensive care unit; INR, international normalized ratio; i.v., intravenous; LT, liver transplantation; NAC, N-acetylcysteine.

Multivariable analysis of nonlisted patients: Association with mortality at 21 days

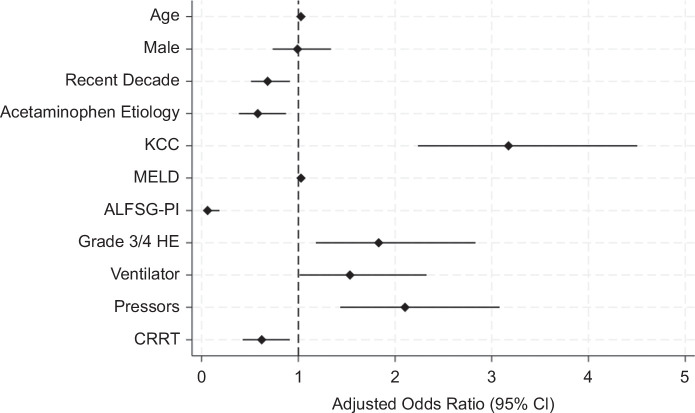

To determine variables independently associated with mortality at 21 days, multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed. Testing for collinearity did not reveal any collinear variables. In our final multivariate model, after adjusting for covariates, age (aOR: 1.03 [95% CI: 1.02–1.04], p < 0.001), KCC (aOR: 3.17 [95% CI: 2.23–4.51], p < 0.001), MELD (aOR: 1.03 [95% CI: 1.01–1.05], p = 0.004), coma (high-grade HE) (aOR: 1.83 [95% CI: 1.18–2.83], p = 0.007), mechanical ventilation (aOR: 1.53 [95% CI: 1.01–2.33], p = 0.043), and vasopressor use (aOR: 2.10 [95% CI: 1.43–3.08], p < 0.001) were all independently associated with mortality at 21 days. Recent era (aOR: 0.68 [95% CI: 0.51–0.91], p = 0.01), APAP etiology (aOR: 0.58 [95% CI: 0.38–0.87], p = 0.009), ALFSG-PI (aOR: 0.06 [95% CI: 0.02–0.18], p < 0.001), and CRRT use (aOR: 0.62 [95% CI: 0.42–0.91], p = 0.015) were all independently associated with reduced mortality at 21 days. This is shown in Table 3 and Figure 1. This model performed well with an AUROC of 0.875.

TABLE 3.

Logistic regression for nonlisted ACLF patients (n=1564)

| Univariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | Odds ratio | p |

| Age | 1564 | 1.03 (1.02–1.03) | <0.001 |

| Male (vs. female) | 1564 | 1.38 (1.11–1.72) | 0.004 |

| Recent era (vs. early era) | 1564 | 0.86 (0.70–1.05) | 0.144 |

| APAP etiology (vs Non-APAP etiology) | 1564 | 0.35 (0.28–0.43) | <0.001 |

| King’s College Criteria (days 1–7) | 1564 | 6.94 (5.28–9.10) | <0.001 |

| Highest MELD (days 1–7) | 1550 | 1.08 (1.07–1.10) | <0.001 |

| Highest ALFSG Prognostic Index (days 1–7) | 1521 | 0.004 (0.002–0.008) | <0.001 |

| Coma Grade 3/4 (days 1–7) | 1535 | 6.04 (4.62–7.89) | <0.001 |

| Ventilation (days 1–7) | 1564 | 4.34 (3.41–5.50) | <0.001 |

| Vasopressors (days 1–7) | 1564 | 6.64 (5.27–8.37) | <0.001 |

| CRRT(days 1–7) | 1564 | 1.70 (1.29–2.24) | <0.001 |

| Multivariable model: N = 1521; AUROC = 0.875 | |||

| Variable | Included in model | Adjusted odds ratio | p |

| Age | Yes | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | <0.001 |

| Male (vs. female) | Yes | 0.99 (0.73–1.34) | 0.953 |

| Recent era (vs. early era) | Yes | 0.68 (0.51–0.91) | 0.01 |

| APAP etiology (vs Non-APAP etiology) | Yes | 0.58 (0.38–0.87) | 0.009 |

| King’s College Criteria (days 1–7) | Yes | 3.17 (2.23–4.51) | <0.001 |

| Highest MELD (days 1–7) | Yes | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.004 |

| Highest ALFSG Prognostic Index (days 1–7) | Yes | 0.06 (0.02–0.18) | <0.001 |

| Coma Grade 3/4 (days 1-7) | Yes | 1.83 (1.18–2.83) | 0.007 |

| Ventilation (days 1–7) | Yes | 1.53 (1.01–2.33) | 0.043 |

| Vasopressors (days 1–7) | Yes | 2.10 (1.43–3.08) | <0.001 |

| CRRT(days 1–7) | Yes | 0.62 (0.42–0.91) | 0.015 |

Note: Independent associations for death at 21 days. Collinearity testing was completed, showing no collinearity. AUROC is 0.875. Final model: [log(odds of death at 21 days) = −2.512 + 0.026 (Age) – 0.009 (Male) – 0.384 (recent era) – 0.547 (APAP etiology) + 1.156 (KCC) + 0.027 (MELD) – 2.789 (ALFSG-PI) + 0.604 (Coma) + 0.428 (Ventilator) + 0.743 (Vasopressor) – 0.477 (CRRT)].

Abbreviations: ALFSG, Acute Liver Failure Study Group; ALFSG-PI, Acute Liver Failure Study Group Prognostic Index; APAP, acetaminophen; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; KCC, King’s College Criteria.

FIGURE 1.

Adjusted independent associations with increased and decreased death at 21 days in nonlisted patients with ALF. Abbreviations: ALFSG-PI, Acute Liver Failure Study Group prognostic index; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; KCC, King’s College criteria.

Comparison of nonlisted and listed patients

After comparing nonlisted patients with ALF to those listed for LT, nonlisted patients were older (42 vs. 38 y of age, p < 0.001), a higher proportion enrolled in the recent era (51.4% vs. 39.0%, p < 0.001), were more likely to have APAP etiology (53.9% vs. 29.1%, p < 0.001), were less likely to meet KCC (20.7% vs. 28.3%, p < 0.001), and had higher ALFSG-PI (36.8% vs. 15.0%, p < 0.001). Survival at 21 days was significantly lower (64.3% vs. 75.7%, p < 0.001) in nonlisted patients. A comparison between nonlisted and listed patients with ALF is shown in Supplemental Table S1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B72.

Comparison of nonlisted (not sick enough) and listed patients

After separating nonlisted patients with ALF into 2 categories (not sick enough and too sick) and then comparing these patients to listed patients, the nonlisted (not sick enough) patients had a higher proportion being enrolled in the recent era (61.2% vs. 39.0%, p < 0.001), a higher proportion having APAP etiology (63.7% vs. 29.1%, p < 0.001), were less likely to fulfill KCC (5.4% vs. 28.3%, p < 0.001), had lower MELD (29 vs. 36, p < 0.001), were less likely to have high-grade HE (34.2% vs. 65.4%, p < 0.001), and had significantly higher ALFSG-PI (67.6% vs. 15.0%, p < 0.001). Survival at 21 days was significantly higher for nonlisted (not sick enough) patients (95.8% vs. 75.7%, p < 0.001). Comparison between nonlisted (not sick enough) and listed patients is demonstrated in Supplemental Table S2, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B72.

Comparison of nonlisted (too sick) and listed patients

When comparing nonlisted (too sick) patients to those who were listed, nonlisted (too sick) patients were older (51 vs. 38 y of age, p < 0.001), had higher proportion enrolled in the recent era (70.4% vs. 39.0%, p < 0.001), higher MELD (40 vs. 36, p < 0.001), higher rates of high-grade HE (75.3% vs. 65.4%, p < 0.001), had similar rates of APAP etiology, similar rates of the fulfillment of KCC, and similar ALFSG-PI. Survival at 21 days was significantly lower for nonlisted (too sick) patients (34.4% vs. 75.7%, p < 0.001). Comparison between nonlisted (too sick) and listed patients is demonstrated in Supplemental Table S3, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B72.

Comparison of nonlisted (not sick enough) survivors and nonsurvivors

Nonlisted patients with ALF deemed not sick enough for LT listing had a 95.8% survival rate. When survivors and nonsurvivors were compared, survivors had higher APAP etiology rates (64.7% vs. 35.3%, p = 0.014), lower rates of fulfilling KCC (4.6% vs. 29.4%, p < 0.001), and had higher ALFSG-PI (68.1% vs. 31.3%, p < 0.001). Survivors required less life support in the form of mechanical ventilation (31.7% vs. 64.7%, p = 0.005), vasopressor use (11.3% vs. 31.6%, p < 0.001), and CRRT (9.0% vs. 23.5%, p = 0.047). Survivors developed fewer complications, including seizures (2.8% vs. 11.8%, p = 0.041), abnormal chest x-rays (44.5% vs. 100%, p = 0.004), and infections (9.5% vs. 29.4%, p = 0.009). Comparison between survivors and nonsurvivors of nonlisted (not sick enough) patients is demonstrated in Supplemental Table S4, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B72.

Comparison of nonlisted (too sick) survivors and nonsurvivors

Nonlisted patients with ALF deemed too sick had a 34.3% survival rate. When survivors and nonsurvivors were compared, survivors had lower rates of fulfilling KCC (15.3% vs. 39.9%, p < 0.001), lower MELD scores (36 vs. 41, p < 0.001), lower rates of high-grade HE (61.3% vs. 83.7%, p < 0.001), and higher ALFSG-PI (33.3% vs. 10.1%, p < 0.001). Survivors also required less life support in the form of mechanical ventilation (57.3% vs. 76.1%, p < 0.001) and vasopressor use (31.5% vs. 60.9%, p < 0.001). When looking at admission biochemistry, survivors had lower INR (2.3 vs. 3.2, p < 0.001), lower bilirubin (4.6 vs. 10.1, p < 0.001), lower ammonia (72 vs. 114, p < 0.001), and lower lactate (3.1 vs. 7.0, p < 0.001). Aside from having higher rates of infection, survivors and nonsurvivors had similar rates of all other complications. Comparison between survivors and nonsurvivors of nonlisted (too sick) patients is demonstrated in Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HC9/B72.

DISCUSSION

Key results

In this study of 1672 patients with ALF not listed for LT, roughly a third fell into each of 3 categories: 33.3% of patients were deemed not sick enough, 28.4% of patients had psychosocial contraindications, and 29.8% of patients were deemed too sick to benefit from LT. Overall survival at 21 days was 64.3%. Overall 21-day survival was 95.8% for patients not listed due to being not sick enough and 34.3% for patients not listed due to being considered too sick to survive. After adjusting for covariates, factors associated with improved overall 21-day survival in nonlisted patients included being enrolled in the recent era, having APAP etiology for ALF, having a high ALFSG-PI, and using CRRT.

Nonlisted patients who were not sick enough were classified as such for a number of reasons. Close to 95% did not fulfill KCC, and over 60% had APAP as the etiology of ALF. A minority of these patients required life support measures. These patients had signs of ongoing clinical improvement early in their course. Nonlisted patients who were too sick were also classified as such for a number of reasons by the treating team. Having irreversible brain injury (1.6%) and sepsis (3%) were factors, along with the need for high amounts of life support (close to 70% required mechanical ventilation and over 50% required vasopressors), presence of MOF (cause of death in 30%), and having pre-existing conditions that would make surviving LT a challenge.

When comparing overall nonlisted patients to listed patients, nonlisted patients were more likely to have APAP etiology of ALF, less likely to require mechanical ventilation and RRT, less likely to meet KCC, have higher ALFSG-PI, more likely to develop bacteremia, and more likely to die. When compared to listed patients, nonlisted patients who were not sick enough were more likely to survive, while nonlisted patients who were too sick had lower rates of survival with higher rates of death by MOF. Overall, clinicians were more accurate in deeming patients not sick enough to need LT (>95% survival rate) as opposed to deeming patients too sick to survive (still >30% survival rate).

Comparison with the literature

This study represents a large multicenter cohort of patients with ALF not listed for LT and provides a detailed assessment of outcomes and clinical and biochemical factors that affect these outcomes. Despite not being listed for LT, overall 21-day survival in this study was 64.3%, which is greater than previously reported TFS rates of 43%–56.2%.15,21 Over the past 20 years, outcomes have significantly improved for patients with ALF.4,8 In this study, there was an era effect seen with being enrolled between 2009 and 2018, which was independently associated with survival in nonlisted patients with ALF, suggesting improved outcomes over the years. This is similar to recent studies by Karvellas et al and MacDonald et al, showing improved survival over the years in patients with ALF listed for LT, as well as specifically patients with APAP-induced ALF.4,8 A major factor for improved survival is better prevention of cerebral edema through the early use of CRRT.11,12,22,23 The use of CRRT was also independently associated with survival in our study. The requirement of mechanical ventilation, which is most often for decreased mental status and airway protection, was independently associated with mortality in this study. However, 39% of patients with ALF require mechanical ventilation for significant lung injury, which negatively impacts outcomes.24

The etiology of ALF has been demonstrated to be an important factor in the prognosis of ALF. TFS was previously reported at 40% in APAP-related ALF compared with only 11% for non-APAP–related ALF.25 Similarly, having APAP as the etiology of ALF pertained to a better prognosis and was independently associated with survival in this study. In a study of patients with ALF listed for LT, patients with APAP etiology had spontaneous survival of 60% (more than twice that of non-APAP etiology) and were only transplanted 16% of the time.16

Ammonia levels are associated with complications and can affect outcomes in patients with ALF, even if severe hyperammonemia (>150 μmol/L) is not necessarily present. Previously, Bernal et al26 demonstrated that an ammonia level >100 μmol/L was associated with severe HE. Even with persistent ammonia levels >85 μmol/L, patients with ALF had an increased risk of complications and death.27 Our study found that nonlisted patients had a median ammonia level of 89 μmol/L, with those who died having a much higher median ammonia level of 112 μmol/L. The vast majority of nonlisted patients who died had severe HE (85.2%), which our study found was independently associated with death at 21 days.

Despite the majority of nonlisted patients with ALF surviving and with steady improvements in outcomes over the years, listing for LT is still often required for patients not responding to maximal medical therapies. This study demonstrated significantly higher 21-day overall survival rates in patients listed for LT (75.7% vs. 64.3%, p < 0.001) compared to nonlisted patients. This is most likely related to excellent survival after LT. Karvellas et al4 recently demonstrated one-year and 3-year post-LT survival rates of 91% and 90%, respectively. Previously, Reddy et al16 also showed excellent survival (92%) after LT in patients with ALF listed for LT. Also seen in this cohort, patients with ALF not ultimately transplanted had a spontaneous survival of 52%. LT, therefore, needs to be seriously considered in patients with ALF who show no signs of spontaneous recovery.

With improvements in outcomes, prognostication in ALF remains highly important. Prognostic tools such as KCC, MELD, and ALFSG-PI all independently affected overall 21-day mortality in this study, with meeting KCC and having high MELD associated with increased 21-day mortality while having high ALFSG-PI being associated with reduced 21-day mortality. Previous studies have shown KCC to have a sensitivity and specificity for predicting mortality of 58%–68% and 82%–95%, respectively, depending on whether ALF was APAP-induced or not.28,29 This suggests that KCC is better at predicting mortality than predicting survival. MELD was shown to have similar sensitivity and specificity for predicting mortality when compared with KCC.30 More recently, the ALFSG-PI was developed to help predict 21-day TFS as opposed to mortality and performed better than both KCC and MELD.19 However, the ALFSG-PI may overestimate the need for LT.25 Therefore, it appears prognostication still remains a challenge.

In this study, patients with ALF not listed for LT due to not being sick enough still had 4% mortality at 21 days, whereas patients deemed too sick to survive had 34.3% survival at 21 days. When looking at the entire group of nonlisted patients, fulfillment of KCC was lower, and ALFSG-PI was higher compared to listed patients. For the subcategory of nonlisted patients who were too well, fulfillment of KCC was also lower, and ALFSG-PI was also higher compared to listed patients. However, for the subcategory of nonlisted patients who were too sick, there was no difference in fulfillment of KCC and ALFSG-PI compared to listed patients. This suggests a better ability, although not perfect, to predict patients who are well and will spontaneously survive (>95% survival rate in nonlisted patients deemed not sick enough) as opposed to being able to predict patients who are too sick and will not survive (>30% survival in nonlisted patients deemed too sick). Further studies looking at prognostication in ALF are still needed.

Strengths and limitations

This study should be interpreted in light of its strengths and limitations. The strengths include the recruitment of patients from multiple intensive care units across many geographic regions in North America. Patients in this study were mostly young, female, and demographically similar to patient populations reported in previous ALF studies from North America and Europe. Limitations include the retrospective nature of the analysis, resulting in only associations being drawn, and the inability to conclusively rule out sources of selection bias. Given that the ALFSG registry does not have complete clinical information before day 1 of study enrollment, we cannot exclude a possible referral bias of patients from referring hospitals to ALFSG enrolling sites. Data on patients enrolled in the ALFSG registry from the referring hospital (ie, pre-enrollment requirement for organ support) were unavailable. Development of the ALFSG-PI used patient data from the ALFSG registry, so many of the same patients were also included in this current study. Therefore, even with no collinearity seen in multivariate analysis, ALSFG-PI may not entirely be an independent variable, and its prognostic importance should be viewed within this limitation. Despite the limitations, this study is the most recent and largest cohort of consecutive patients with ALF not listed for transplant evaluating clinical outcomes across multiple tertiary care centers, allowing for broad generalizability of the results.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients with ALF may not undergo listing for LT for a multitude of reasons. Despite this, the majority of these patients are still alive at 21 days, especially those with APAP as the etiology. When compared to patients listed for LT, nonlisted patients did have lower 21-day survival. Accurate prognostication is important in this patient population, and clinicians are highly accurate at predicting those who are not sick enough to need an LT (spontaneous survival rate of over 95%). Prognosticating patients deemed too sick to survive, however, still remains somewhat of a challenge (spontaneous survival rates of over 30%).

Supplementary Material

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Victor Dong: performed statistical analysis and interpretation of data and drafted the final manuscript. Valerie Durkalski: helped with the study concept and design and significantly revised the final manuscript. William M. Lee: supervisor of the entire Acute Liver Failure Study Group (U-01 Grant) and critically revised the manuscript. Constantine J. Karvellas: conceived the study concept and design, performed statistical analysis and interpretation of the data, and critically revised the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Members and institutions participating in the Acute Liver Failure Study Group 1998–2016 are as follows: W.M. Lee, MD (Principal Investigator); Anne M. Larson, MD, Iris Liou, MD, University of Washington, Seattle, WA; Oren Fix, MD, Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, WA; Michael Schilsky, MD, Yale University, New Haven, CT; Timothy McCashland, MD, University of Nebraska, Omaha, NE; J. Eileen Hay, MBBS, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN; Natalie Murray, MD, Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, TX; A. Obaid S. Shaikh, MD, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA; Andres Blei, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL (deceased), Daniel Ganger, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL; Atif Zaman, MD, University of Oregon, Portland, OR; Steven H.B. Han, MD, University of California, Los Angeles, CA; Robert Fontana, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI; Brendan McGuire, MD, University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL; Raymond T. Chung, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA; Alastair Smith, MB, ChB, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC; Robert Brown, MD, Cornell/Columbia University, New York, NY; Jeffrey Crippin, MD, Washington University, St Louis, MO; Edwin Harrison, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ; Adrian Reuben, MBBS, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC; Santiago Munoz, MD, Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA; Rajender Reddy, MD, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA; R. Todd Stravitz, MD, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA; Lorenzo Rossaro, MD, University of California Davis, Sacramento, CA; Raj Satyanarayana, MD, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL; and Tarek Hassanein, MD, University of California, San Diego, CA; Constantine J. Karvellas MD, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB; Jodi Olson, MD, University of Kansas, Kansas City, KA; Ram Subramanian, MD, Emory, Atlanta, GA; James Hanje, MD, Ohio State University, Columbus,OH; Bilal Hameed, MD, University of California San Francisco, CA. The University of Texas Southwestern Administrative Group included Grace Samuel, Ezmina Lalani, Carla Pezzia, and Corron Sanders, PhD, Nahid Attar, Linda S. Hynan, PhD, and the Medical University of South Carolina Data Coordination Unit included Valerie Durkalski, PhD, Wenle Zhao, PhD, Jaime Speiser, Catherine Dillon, Holly Battenhouse, and Michelle Gottfried.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The study was sponsored by NIH grant U-01 58369 (from NIDDK).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

William M. Lee receives research support from Merck, Conatus, Intercept, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novo Nordisk, Synlogic, Eiger, Cumberland, Exalenz, Instrumentation Laboratory, and Ocera Therapeutics, now Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, and has received personal fees for consulting from Forma, Sanofi, Seattle Genetics, Affibody, Karuna, and Genentech. The remaining authors have no conflicts to report.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The institutional review board/health research ethics boards of all participating ALFSG sites approved all protocols.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ALF, acute liver failure; ALFSG, Acute Liver Failure Study Group; ALFSG-PI, Acute Liver Failure Study Group Prognostic Index; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; APAP, acetaminophen; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; INR, international normalized ratio; KCC, King’s College Criteria; LT, liver transplantation; MOF, multiorgan failure; RRT, renal replacement therapy; TFS, transplant-free survival.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.hepcommjournal.com.

Contributor Information

Victor Dong, Email: vdong@ualberta.ca.

Valerie Durkalski, Email: durkalsv@musc.edu.

William M. Lee, Email: william.lee@utsouthwestern.edu.

Constantine J. Karvellas, Email: cjk2@ualberta.ca.

Collaborators: W.M. Lee, Anne M. Larson, Iris Liou, Oren Fix, Michael Schilsky, Timothy McCashland, J. Eileen Hay, Natalie Murray, A. Obaid S. Shaikh, Andres Blei, Daniel Ganger, Atif Zaman, Steven H.B. Han, Robert Fontana, Brendan McGuire, Raymond T. Chung, Alastair Smith, Robert Brown, Jeffrey Crippin, Edwin Harrison, Adrian Reuben, Santiago Munoz, Rajender Reddy, R. Todd Stravitz, Lorenzo Rossaro, Raj Satyanarayana, Tarek Hassanein, Constantine J. Karvellas, Jodi Olson, Ram Subramanian, James Hanje, Bilal Hameed, Ezmina Lalani Samuel, Carla Pezzia, Corron Sanders, Nahid Attar, Linda S. Hynan, Valerie Durkalski, Wenle Zhao, Jaime Speiser, Catherine Dillon, Holly Battenhouse, and Michelle Gottfried

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernal W, Auzinger G, Dhawan A, Wendon J. Acute liver failure. Lancet. 2010;376:190–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong V, Nanchal R, Karvellas CJ. Pathophysiology of acute liver failure. Nutr Clin Pract. 2020;35:24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams R, Schalm SW, O'Grady JG. Acute liver failure: Redefining the syndromes. Lancet. 1993;342:273–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karvellas CJ, Leventhal TM, Rakela JL, Zhang J, Durkalski V, Reddy KR, et al. Outcomes of patients with acute liver failure listed for liver transplantation: A multicenter prospective cohort analysis. Liver Transpl. 2023;29:318–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stravitz RT, Lee WM. Acute liver failure. Lancet. 2019;394:869–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stravitz RT, Kramer AH, Davern T, Shaikh AOS, Caldwell SH, Mehta RL, et al. Intensive care of patients with acute liver failure: Recommendations of the U.S. Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2498–2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernal W, Hyyrylainen A, Gera A, Audimoolam VK, McPhail MJW, Auzinger G, et al. Lessons from look-back in acute liver failure? A single centre experience of 3300 patients. J Hepatol. 2013;59:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald AJ, Speiser JL, Ganger DR, Nilles KM, Orandi BJ, Larson AM, et al. Clinical and neurologic outcomes in acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: A 21-year multicenter cohort study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2615–2625.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prescott LF, Critchley JAJH. The treatment of acetaminophen poisoning. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1983;23:87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee WM, Hynan LS, Rossaro L, Fontana RJ, Stravitz RT, Larson AM, et al. Intravenous N-acetylcysteine improves transplant-free survival in early stage non-acetaminophen acute liver failure. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:856–64, 864.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardoso FS, Gottfried M, Tujios S, Olson JC, Karvellas CJ, Group UALFS . Continuous renal replacement therapy is associated with reduced serum ammonia levels and mortality in acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2018;67:711–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong V, Robinson AM, Dionne JC, Cardoso FS, Rewa OG, Karvellas CJ. Continuous renal replacement therapy and survival in acute liver failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care. 2024;81:154513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsen FS, Schmidt LE, Bernsmeier C, Rasmussen A, Isoniemi H, Patel VC, et al. High-volume plasma exchange in patients with acute liver failure: An open randomised controlled trial. J Hepatol. 2016;64:69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pezzia C, Sanders C, Welch S, Bowling A, Lee WM. Psychosocial and behavioral factors in acetaminophen-related acute liver failure and liver injury. J Psychosom Res. 2017;101:51–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ostapowicz G. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:947–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy KR, Ellerbe C, Schilsky M, Stravitz RT, Fontana RJ, Durkalski V, et al. Determinants of outcome among patients with acute liver failure listed for liver transplantation in the United States. Liver Transpl. 2016;22:505–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Grady JG, Alexander GJM, Hayllar KM, Williams R. Early indicators of prognosis in fulminant hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koch DG, Tillman H, Durkalski V, Lee WM, Reuben A. Development of a model to predict transplant-free survival of patients with acute liver failure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1199–1206.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamath P. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:464–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reuben A, Tillman H, Fontana RJ, Davern T, McGuire B, Stravitz RT, et al. Outcomes in adults with acute liver failure between 1998 and 2013: An observational cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:724–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nanchal R, Subramanian R, Karvellas CJ, Hollenberg SM, Peppard WJ, Singbartl K, et al. Guidelines for the management of adult acute and acute-on-chronic liver failure in the ICU: Cardiovascular, endocrine, hematologic, pulmonary and renal considerations: Executive summary. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:415–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shingina A, Mukhtar N, Wakim-Fleming J, Alqahtani S, Wong RJ, Limketkai BN, et al. Acute liver failure guidelines. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:1128–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dong V, Sun K, Gottfried M, Cardoso FS, McPhail MJ, Stravitz RT, et al. Significant lung injury and its prognostic significance in acute liver failure: A cohort analysis. Liver Int. 2020;40:654–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stravitz RT, Fontana RJ, Karvellas C, Durkalski V, McGuire B, Rule JA, et al. Future directions in acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2023;78:1266–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernal W, Hall C, Karvellas CJ, Auzinger G, Sizer E, Wendon J. Arterial ammonia and clinical risk factors for encephalopathy and intracranial hypertension in acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2007;46:1844–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar R, Shalimar, Sharma H, Prakash S, Panda SK, Khanal S, et al. Persistent hyperammonemia is associated with complications and poor outcomes in patients with acute liver failure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:925–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Craig DGN, Ford AC, Hayes PC, Simpson KJ. Systematic review: Prognostic tests of paracetamol-induced acute liver failure. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:1064–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McPhail MJW, Wendon JA, Bernal W. Meta-analysis of performance of Kings’s College Hospital Criteria in prediction of outcome in non-paracetamol-induced acute liver failure. J Hepatol. 2010;53:492–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parkash O, Mumtaz K, Hamid S, Ali Shah SH, Wasim Jafri SM. MELD score: Utility and comparison with King’s College criteria in non-acetaminophen acute liver failure. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2012;22:492–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.