Summary

Antipsychotic drugs have been shown to have antitumor effects but have had limited potency in the clinic. Here, we unveil that pimozide inhibits lysosome hydrolytic function to suppress fatty acid and cholesterol release in glioblastoma (GBM), the most lethal brain tumor. Unexpectedly, GBM develops resistance to pimozide by boosting glutamine consumption and lipogenesis. These elevations are driven by SREBP-1, which we find upregulates the expression of ASCT2, a key glutamine transporter. Glutamine, in turn, intensifies SREBP-1 activation through the release of ammonia, creating a feedforward loop that amplifies both glutamine metabolism and lipid synthesis, leading to drug resistance. Disrupting this loop via pharmacological targeting of ASCT2 or glutaminase, in combination with pimozide, induces remarkable mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress, leading to GBM cell death in vitro and in vivo. Our findings underscore the promising therapeutic potential of effectively targeting GBM by combining glutamine metabolism inhibition with lysosome suppression.

Keywords: glioblastoma, pimozide, ASCT2, glutamine, GLS, SREBP-1, lipid droplets, cholesterol, fatty acids, lysosome

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Pimozide inhibits lysosome function while stimulating glutamine consumption in GBM

-

•

Pimozide activates SREBP-1 that promotes glutamine uptake by upregulating ASCT2

-

•

Combining lysosome and glutamine inhibition severely impairs mitochondria in GBM

-

•

This combination significantly suppresses GBM growth in vitro and in vivo

Zhong et al. report that GBM resists the antipsychotic drug pimozide treatment by activating SREBP-1, which unexpectedly elevates glutamine consumption by upregulating the expression of ASCT2. They demonstrate combining pimozide with a pharmacological blockade of glutamine consumption effectively inhibits GBM growth in vivo, presenting a promising avenue for targeting GBM.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, there has been no significant progress in the therapy for glioblastoma (GBM), which has a median survival of only 12–16 months from diagnosis despite extensive treatments.1,2 GBM is a very aggressive cancer, and at diagnosis its tumor cells have already invaded into the surrounding normal brain tissue, rendering complete surgical resection, an ineffective therapeutic option.2 Additionally, the presence of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) restricts the penetration of many potent antitumor drugs into GBM tissues, making GBM one of the most difficult cancers to treat.3

Recent investigations have revealed the potential of certain brain-penetrant antipsychotic drugs to induce cell death in GBM cells in vitro.4,5 However, these promising effects are difficult to reproduce in vivo in intracranial GBM models.6 The inconsistency between in vitro and in vivo studies may be attributed to two factors: first, the in vivo administration of these drugs could not achieve an effective dose capable of efficiently eliminating tumor cells, due to a toxicity concern in normal tissues; and second, tumor cells could rapidly develop resistance to intracranially delivered drugs.7,8,9 Our primary objective was 2-fold: to identify a potent brain-penetrant drug capable of effectively treating GBM at a safe dose in a preclinical model, while concurrently developing a strategy to prevent the development of tumor resistance.

In this study, we discovered that the antipsychotic drug pimozide exhibits inhibitory effects on GBM cell viability. However, GBM cells acquire resistance to this therapy by upregulating glutamine metabolism. By targeting glutamine uptake or consumption, we uncovered a potent synergy with pimozide, overcoming tumor resistance and effectively eradicating GBM cells both in vitro and in vivo settings. This combination treatment holds promise for translation into clinical trials, not only as a potential therapy for GBM but also for other aggressive tumor types reliant on glutamine and lipids for sustenance.

Results

Limiting glutamine availability sensitizes GBM to pimozide-based treatment

We examined the cytotoxic effects of nine Food and Drug Administration-approved antipsychotic drugs previously reported for their potential antitumor activities10,11,12,13 in GBM cell lines U251 and U373 and patient-derived primary GBM30 cells. Our investigation revealed that pimozide, a medication used for the treatment of schizophrenia,14,15 as well as motor and phonic tics associated with Tourette’s syndrome,16,17 exhibited the highest potency in vitro against all these GBM cells (Figure S1A). Notably, the antitumor properties of pimozide were recognized as far back as the 1970s, demonstrated in pituitary tumor cell lines and rat models.18 Subsequent research on this drug has persisted, exploring its potential for various types of cancers in preclinical models.19,20,21 Additionally, in the 1980s, a phase 2 clinical trial involving 30 patients with metastatic melanoma investigated pimozide’s effectiveness, yielding partial responses in six of the patients.22 Since this trial, no further cancer trials with pimozide have been reported.

Recent studies have underscored the critical roles of specific amino acids, notably, glutamine, methionine, lysine, and arginine, in fueling tumor growth.23,24,25,26,27 We set out to investigate whether limiting amino acid availability could enhance the sensitivity of GBM to pimozide treatment. We cultured three different GBM cells for 6 days in a full DMEM medium that contains 15 amino acids until colonies formed (Figures 1A, 1B, and S1B). Subsequently, we replaced the complete medium with a fresh medium, each lacking one of the 15 amino acids, followed by treatment with/without pimozide in the presence of 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Unexpectedly, limiting glutamine availability led to a profound effect: pimozide at 3 μM nearly completely eradicated pre-existing colonies and effectively killed GBM cells (Figures 1B, 1C, and S1B–S1D). In contrast, when used at the same dose in the complete medium, pimozide only exhibited mild inhibition of colony growth (Figures 1B, 1C, and S1B–S1D). Intriguingly, removal of any other amino acids failed to heighten pimozide sensitivity (Figures 1B, 1C, and S1B). Notably, cystine (Cys), crucial in regulating cellular redox homeostasis,28,29 was found to be vital for GBM colony maintenance (Figures 1B and S1B), emphasizing the critical role of redox balance in GBM viability.

Figure 1.

Pimozide upregulates glutamine metabolism in GBM cells

(A) Schematic diagram illustrating the development of GBM colonies for drug treatment.

(B and C) Effects of pimozide treatment for 8 days on established U251 cells-derived colonies (n = 3 independent experiments) in DMEM medium containing 1% FBS in the presence and absence of the indicated amino acids (AA) (B) Day 0 indicates the pre-formed colonies before treatment. Colony numbers were quantified by ImageJ and normalized with the number of control cells in a full DMEM medium without drug treatment (mean ± SD, n = 3) (C). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons adjustments.

(D and E) Heatmap of metabolomics analysis of U251 cells supplemented with 13C5-glutamine (2 mM) for 1 h after treatment with pimozide (PMZ, 3 μM) for 24 h (D). The results are from three biological replicates and summarized by the indicated schematic diagram (E). 13C carbons are shown as red circles, and 12C carbons are shown as white circles. Created with BioRender.com.

(F–M) Comparison of the abundance of individual metabolites derived from 13C5-glutamine in different metabolic pathways between pimozide-treated and untreated U251 cells (mean ± SD, n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by unpaired Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons adjustments. Metabolomics studies are repeated twice. Results represent one of two independent experiments. See also Figures S1 and S2.

Pimozide enhances glutamine consumption and promotes reductive carboxylation-mediated lipid synthesis

We proceeded to investigate the role of glutamine in pimozide sensitivity. We conducted a stable isotope 13C5-glutamine flux assay coupled with untargeted metabolomics analysis using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) in GBM cells. Notably, pimozide treatment exhibited a remarkable increase in virtually all facets of glutamine metabolism (Figures 1D–1M and S2A–S2D). These encompassed elevated glutamine uptake (Figure 1F), intensified glutaminolysis (Figures 1G and S2A), heightened reductive carboxylation (Figure 1H) and the subsequent de novo fatty acid (FA) synthesis it drives (Figures 1I and S2B), augmented tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle anaplerosis (Figures 1J and S2C), and intensified synthesis of glutathione (GSH) (Figure 1K), nucleotides (Figure 1L), and other amino acids, namely proline and aspartate (Figures 1M and S2D). These findings strongly suggest that the upregulation of glutamine uptake and consumption potentially serves as a survival mechanism for GBM cells under pimozide treatment.

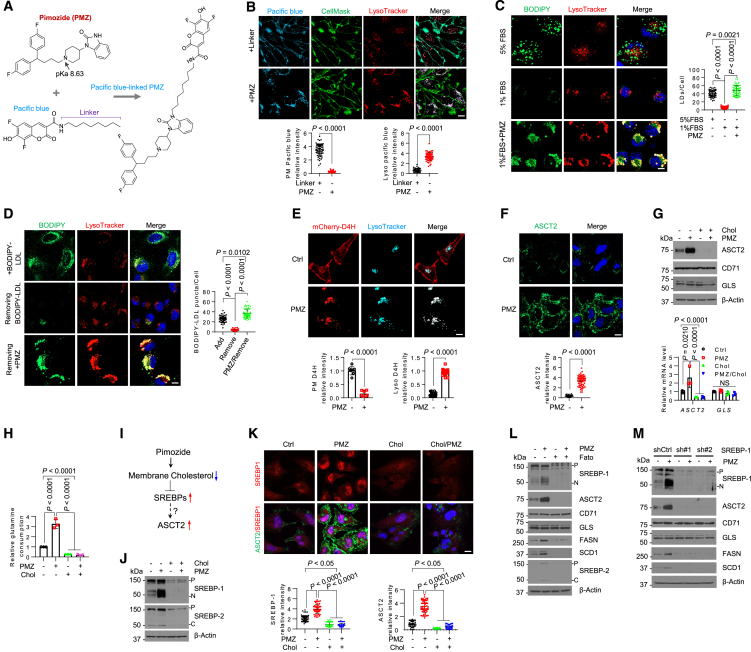

Pimozide diminishes membrane cholesterol levels by inhibiting lysosome-mediated lipid droplet and lipoprotein hydrolysis

To investigate how pimozide induces the upregulation of glutamine metabolism, we employed Pacific blue, a fluorescent molecule, to label the drug (Figures 2A, S3A, and S3B). This enabled us to examine its subcellular distribution within GBM cells. Fluorescence imaging revealed that Pacific blue-labeled pimozide predominantly accumulated within the lysosomes, as confirmed by co-staining with LysoTracker (Figure 2B). We did not observe Pacific blue-labeled pimozide localization in the plasma membrane, as indicated by CellMask staining (green) (Figure 2B), mitochondria (MitoTracker, green) (Figure S3C), or endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (mCherry-labeled ER protein marker Sec61) (Figure S3D). In contrast, Pacific blue specifically attached to the plasma membrane through the linker (octanamine) (Figure 2B), while Pacific blue alone, without the linker, did not bind to the cells (Figure S3E).

Figure 2.

Pimozide acts via SREBP-1 to upregulate the expression of the glutamine transporter ASCT2 to promote glutamine consumption

(A) A schematic diagram illustrating the synthesis of Pacific blue-labeled pimozide. Created with ChemDraw.

(B) Representative fluorescence imaging of Pacific blue-labeled pimozide (3 μM) vs. Pacific blue with the linker only (3 μM) in U251 cells with co-staining of lysosomes by LysoTracker, plasma membrane by CellMask after treatment for 24 h in 1% FBS. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(C and D) Representative fluorescence images of lipid droplets (LDs) stained with BODIPY 493/503 (C) or BODIPY-labeled LDL (D) together with lysosome staining by LysoTracker in U251 cells after pimozide (3 μM) treatment for 24 h in 1%FBS. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(E) Representative fluorescence images of the cholesterol-binding probe derived from anaerobic bacteria Perfringolysin O theta toxin domain 4 (D4H) labeled by mCherry (GST-mCherry-D4H) in U251 cells under the same treatment as (C) and (D). The cells were co-stained with LysoTracker. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(F) Representative immunofluorescence images of anti-ASCT2 in U251 cells under the same treatment condition as (C) and (D). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(G) Western blotting analysis of membrane extracts (for ASCT2 and CD71) and total lysates (for GLS) (top) and real-time RT-PCR analysis of their gene expression (bottom) (mean ± SD, n = 3) in U251 cells after treatment with/without pimozide (3 μM) and cholesterol (3 μg/mL) for 24 h.

(H) Relative glutamine consumption levels in U251 cells after treatment as G and normalized with control cells (mean ± SD, n = 3).

(I) A schematic diagram illustrating the potential mechanism by which ASCT2 expression is upregulated by pimozide.

(J) Western blotting analysis of the total lysates of U251 cells after treatment as in panel G.

(K) Representative immunofluorescence images of anti-SREBP-1 and anti-ASCT2 in U251 cells after treatment as in (G). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(L and M) Western blotting analysis of U251 cells after treatment with/without pimozide (3 μM) and Fatostatin (Fato, 5 μM) for 24 h (L), or after shRNA silencing of SREBP-1 vs. shRNA control (shCtrl) for 48 h following treatment with or without pimozide (3 μM) for another 24 h in 1% FBS condition (M). P, precursor; N, N-terminal form; C, C-terminal form. See also Figures S3 and S4.

Pimozide is characterized by its amphiphilic nature and includes an amine group with a pKa of approximately 8.6 (Figure 2A). We next tested whether pimozide penetrates lysosomes, which typically maintain a pH 4.5–5.0, and affects their pH. By using LysoSensor Yellow/Blue dextran, a pH-sensitive fluorescence reagent,30 we found that pimozide treatment substantially increased lysosomal pH, evident in the shift from yellow (indicative of an acidic pH) to blue (indicating a more neutral pH) fluorescence signals (Figure S3F). Furthermore, through the utilization of DQ-Green BSA assays, we demonstrated that pimozide treatment markedly suppressed lysosomal hydrolytic activity, as indicated by a decrease in the bright green fluorescence observed in untreated cells (Figure S3G). We then delved into whether pimozide impeded the hydrolysis of lipid droplets (LDs) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), both of which contain significant amounts of cholesteryl esters requiring lysosomal hydrolysis for the release of stored cholesterol and FAs to support GBM growth.31,32,33,34,35,36 Notably, our fluorescence imaging experiments revealed that pimozide treatment hindered the hydrolysis of both LDs (Figure 2C) and LDL (Figure 2D), leading to their accumulation within the lysosomes.

We then proceeded to investigate whether pimozide treatment resulted in a reduction of membrane cholesterol. To assess this, we employed a fluorescence probe, GST-mCherry-D4H, derived from the anaerobic bacteria Perfringolysin O theta toxin domain 4 (D4H) (mCherry-D4H, red), which can detect membrane cholesterol levels when they exceed 20% of total membrane lipids.31,37 In untreated GBM cells, we observed strong GST-mCherry-D4H binding in the plasma membrane, with modest binding to the lysosomes (Figure 2E). In contrast, in pimozide-treated cells, GST-mCherry-D4H fluorescence was exclusively observed within the lysosomes (Figure 2E), indicating a significant reduction in membrane cholesterol levels outside of the lysosomal compartments due to pimozide treatment.

Cholesterol reduction activates SREBP-1, leading to upregulation of ASCT2 expression and increased glutamine consumption

We subsequently investigated whether pimozide-induced membrane cholesterol reduction had a direct correlation with its stimulation of glutamine consumption. Through a combination of immunofluorescence (IF), western blotting, and real-time PCR analyses, we made the unexpected discovery that pimozide treatment led to a significant increase in both protein and mRNA levels of the glutamine transporter ASCT2, encoded by SLC1A5 gene, but not glutaminase (GLS) (Figures 2F, 2G, and S4A–S4D). In addition, enzyme activity measurement showed that pimozide treatment did not affect GLS enzyme activity (Figure S4E). In contrast, the elevation in ASCT2/SLC1A5 expression correlated with heightened glutamine consumption under the same treatment conditions (Figure 2H). Importantly, these observed elevations in ASCT2/SLC1A5 expression and glutamine consumption disappeared when cholesterol was added to the cell culture medium (Figures 2G, 2H, and S4F–S4H).

We wondered whether sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs), crucial lipogenic transcription factors whose activation is negatively regulated by cholesterol levels,38,39,40,41 were involved in ASCT2 upregulation and glutamine uptake (Figure 2I). Through a combination of western blotting and IF imaging, we observed that pimozide treatment markedly promoted SREBP-1 cleavage and subsequent nuclear translocation—key indicators of SREBP activation (Figures 2J, 2K, S4F, and S4G).34,40,42,43 This activation coincided with the upregulation of ASCT2 expression and its distribution to the plasma membrane (Figures 2F, 2G, 2K, S4F, and S4G). In contrast, SREBP-2 cleavage was only slightly increased by pimozide (Figures 2J and S5F). Notably, the supplementation of the culture medium with cholesterol completely abolished both SREBP-1 activation and ASCT2 upregulation (Figures 2J, 2K, S4F, and S4G). Intriguingly, pharmacological (using fatostatin) or genetic (via short hairpin RNA [shRNA]) inhibition of SREBP-1, but not SREBP-2, completely abolished pimozide-induced ASCT2 expression (Figures 2L, 2M, and S4I–S4K).

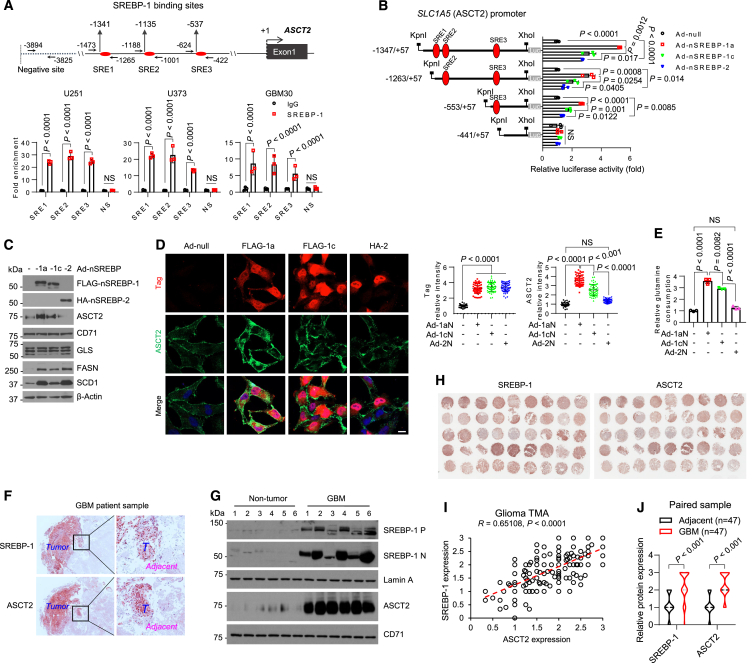

We then delved into whether SREBP-1 directly regulates ASCT2 expression. We proceeded to analyze SLC1A5 gene promoter (which encodes ASCT2) using the online JASPAR resource, a database of transcription factor binding profiles,44,45 and identified three potential sterol regulatory element (SRE) sites (Figure 3A, upper panel). Subsequently, through chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays and real-time PCR analysis, we confirmed that SREBP-1 bound to these identified sites (Figure 3A). To further validate these findings, we cloned the SLC1A5 gene promoter into a pGL3-luciferase promoter reporter vector. Luciferase activity assays revealed that the N-terminal isoform SREBP-1a exhibited the highest potency in stimulating SLC1A5 promoter activity (Figure 3B). Consistently, by introducing N-terminal active forms of SREBPs into GBM cells via adenovirus-mediated expression, western blotting and IF showed that SREBP-1a expression exhibited the strongest upregulation of ASCT2 expression, while SREBP-1c had a modest effect, and SREBP-2 had minimal to no effect (Figures 3C, 3D, S5A, and S5B). Consistently, elevated glutamine consumption was observed in GBM cells expressing N-terminal SREBP-1a and -1c, with no significant effect in SREBP-2-expressing cells (Figures 3E and S5C).

Figure 3.

SREBP-1 transcriptionally activates SLC1A5 gene expression to promote glutamine consumption

(A) The putative SREBP-1 binding sites (SREs) and negative binding site (NS) in the SLC1A5 promoter (top). The arrows show the locations of the designed primers for PCR analysis after immunoglobulin G (IgG) or anti-SREBP-1 antibody-mediated chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) (Bottom).

(B) A schematic diagram illustrating the cloning of different fragments of the SLC1A5 promoter in pGL3-luciferase (Luc) reporter plasmid (left) and measuring their activities in U251 cells in response to the expression of different N-terminal SREBP isoforms (right).

(C and D) Western blotting (C) and immunofluorescence (D) analysis of U251 cells after adenovirus (Ad)-mediated expression of FLAG- or hemagglutinin (HA)-labeled N-terminal SREBP-1a, -1c, or -2 isoforms for 48 h in 5% FBS condition. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(E) Relative glutamine consumption levels in U251 cells after expressing N-terminal SREBP isoforms as in (C) and normalized with control cells (Ad-null) (mean ± SD, n = 3).

(F) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of human GBM tumor (T) vs. Adjacent brain tissues. Scale bars, 50 μm.

(G) Western blotting analysis of membrane and nucleus lysates of GBM tumor vs. non-tumor brain tissues from patient autopsies (n = 6).

(H–J) Representative images of IHC staining of SREBP-1 (left) and ASCT2 (right) (H) and scatterplots of their relative expression (I) in human glioma tissue microarray (TMA, N = 223). The expression levels of SREBP-1 and ASCT2 in paired GBM samples with adjacent brain tissues (J). Experiments from (A–D) were repeated three times. The results represent one of three independent experiments. Statistical significance for (A, B, D, E, and J) were determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons adjustments. See also Figure S5 and Table S1.

Additionally, we conducted an extensive analysis of clinical samples through western blotting and immunohistochemistry (IHC). Our observations revealed a strong co-upregulation of SREBP-1 and ASCT2 in GBM tumor tissues, whereas both were expressed at lower levels in adjacent normal brain tissues (Figures 3F–3J and S5D–S5J; Table S1). This correlation was further corroborated by their higher mRNA expression levels in human GBM compared to normal brain tissues from TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) and GTEx (The Genotype-Tissue Expression) database (Figure S5K). Interestingly, the expression of SREBF2 gene was significantly lower in GBM compared to normal brain tissues, which contrasted with higher expression levels of ASCT2 and SREBP-1a in GBM tissues (Figure S5K).

In summary, our data reveal that pimozide via activation of SREBP-1 upregulates ASCT2 expression and subsequent promotion of glutamine consumption in GBM cells.

Pimozide boosts SREBP-1-driven glutamine uptake in a feedforward loop to concurrently stimulate both glutamine metabolism and lipogenesis

We recently made the discovery that glutamine uptake and metabolism result in the intracellular release of ammonia that serves as a pivotal activator to stimulate SREBP-1 activation and subsequent lipogenesis.46 Building upon this finding and our current results demonstrating SREBP-1 directly upregulates ASCT2 expression (Figures 2I–2M, 3A–3D, and S4E–S4J), we postulated the existence of a feedforward loop involving SREBP-1 activation, ASCT2 expression, glutamine uptake, and ammonia release (Figure 4A). To test this hypothesis, we initially examined human glioma samples using Nessler’s staining to detect ammonia levels47 and conducted IHC to evaluate protein levels. Our observations revealed elevated levels of ammonia, indicated by dark brown dots, in GBM tumor tissues (Figure S6A). This elevation in ammonia levels correlated with increased expression of SREBP-1 and ASCT2 when compared to normal brain and low-grade glioma tissues (Figure S6A). Furthermore, we analyzed tissues from healthy mice and found that ammonia levels in various mouse tissues were closely associated with the expression levels of SREBP-1, ASCT2, and GLS. They were all highly abundant in the small intestine, kidney, spleen, and muscle, modestly presented in the large intestine and liver, and displayed low levels in the brain and pancreatic tissues (Figure S6B).

Figure 4.

Pimozide activates SREBP-1/glutamine uptake feedforward loop that promotes GBM resistance

(A) This schematic diagram illustrates the proposed model of a potential feedforward loop activated by pimozide, leading to the development of GBM resistance. It also highlights the potential efficacy of pharmacological targeting of ASCT2 or GLS in combination with pimozide in effectively eliminating tumor cells.

(B) Nessler’s staining of ammonia (dark brown dots) in U251 cells after treatment with or without pimozide (3 μM), GPNA (1 mM), CB-839 (100 nM), or DON (10 μM) alone or combination for 24 h in 1% FBS. Ammonia dots were quantified by ImageJ from 30 cells (mean ± SD) and normalized with total cell areas (right). Scale bar, 100 μm.

(C–E) Western blotting analysis of U251 cells under the same treatment condition as in (B) in the presence or absence of glutamine (4mM) (E) or ammonia solution (NH4OH) (4 mM).

(F) Combination treatment effects of pimozide (PMZ) with GPNA, DON, CB-839, or Fatostatin (Fato) at indicated doses (48 h) on GBM U251 cell viabilities. Values in each block represent the mean cell viability inhibition with SD (n = 3).

(G) Three-dimensional (3D) plot showing the Loewe synergy score of pairwise dose combinations as shown in (F) in U251 cells. z axis, synergy score; x/y axis, drug combination with different doses.

(H and I) Effects of drug treatment as in B for 8 days on GBM cells-derived colonies in 1% FBS (H). Colony numbers were quantified by ImageJ and normalized with untreated cells (I). See also Figures S6 and S7.

To validate the existence of this feedforward loop, we investigated whether ammonia levels in GBM cells were elevated by pimozide (Figure 4A). Indeed, through Nessler’s staining, we observed a significant increase in ammonia levels in pimozide-treated GBM cells compared to untreated cells (Figure 4B). This was accompanied by heightened SREBP-1 activation and increased ASCT2 expression (Figures 4C–4E and S7A–S7C, lane 2 vs. 1). In contrast, the inhibition of ASCT2 with L-γ-glutamyl-p-nitroanilide (GPNA), various glutamine utilization enzymes with 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON), or GLS with CB-839 led to the abolishment of elevated ammonia levels, SREBP-1 activation, and ASCT2 expression, as well as the expression of the two key lipogenic enzymes fatty acid synthase (FASN) and stearoyl desaturase 1 (SCD1) (Figures 4B, 4D, S7A, and S7B, lane 4 vs. 2). However, the supplementation of ammonia solution (NH4OH) in the presence of these inhibitors fully restored SREBP-1 activation and the levels of ASCT2, FASN, and SCD1 (Figures 4C and 4D, lane 5 vs. 4, and S7A and S7B, lane 5 vs. 4). Consistently, the removal of glutamine also abolished pimozide-induced SREBP-1 activation and ASCT2/FASN/SCD1 expression, all of which were restored by addition of ammonia (NH4OH) (Figures 4E and S7C). Moreover, genetic inhibition of ASCT2 via shRNA-mediated knockdown reduced SREBP-1 activation and FASN/SCD1 expression in multiple GBM cells (Figure S7D). Finally, in an orthotopic xenograft model in mice, we found that knockdown of ASCT2 resulted in reduced levels of both ammonia and SREBP-1 in GBM tumor tissues, along with a significant inhibition of tumor growth and extension of overall survival (Figures S7E–S7H).

We next examined whether disrupting SREBP-1 activation/glutamine uptake feedforward loop by combining inhibition of glutamine metabolism and lysosomal function had synergistic inhibitory effects on GBM cells. To test this, we treated GBM cells with multiple doses of GPNA, DON, CB-839, or Fatostatin in combination with pimozide for 48 h. The analysis using online SynergyFinder web application showed the strong synergy for each drug combination with pimozide in inhibiting GBM cell viabilities (Figures 4F and 4G). Furthermore, the combination of GPNA, DON, or CB-839 with pimozide resulted in the nearly complete eradication of pre-formed GBM cell colonies and the death of these cells, while each drug alone exhibited only a marginal inhibitory effect at the same dose (Figures 4H, 4I, and S8A). In contrast, these treatments did not significantly affect normal human astrocytes (NHAs) (Figure S8A).

In conclusion, our data reveal SREBP-1 activation/ASCT2 expression/glutamine uptake/ammonia release feedforward loop, which is upregulated by pimozide to promote GBM cell resistance (Figure 4A).

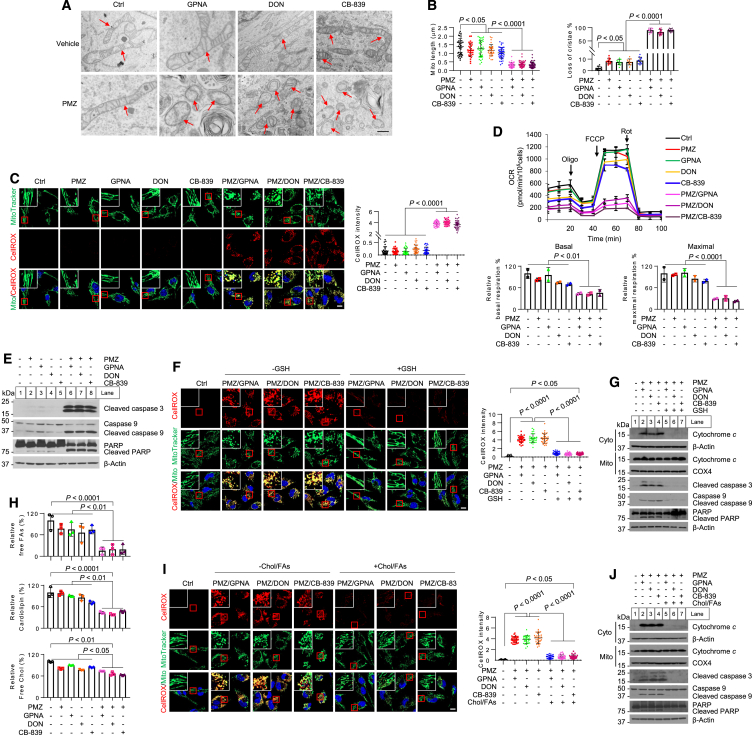

Inhibiting glutamine consumption synergizes with pimozide to induce mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress to blunt GBM cell growth

Strikingly, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging revealed that the mitochondria in GBM cells subjected to the combination treatments of GPNA, DON, and CB-839 with pimozide were dramatically fragmented and displayed a loss of cristae, in stark contrast to the slight effects observed with each drug alone, when compared to control cells (Figures 5A and 5B). Fluorescent imaging using MitoTracker or EGFP-OMP25, a GFP-labeled mitochondrial outer membrane protein,48 confirmed extensive mitochondrial fragmentation in GBM cells following combination treatments, in contrast to single-drug treatment and control cells (Figures 5C and S8B–S8D). The combinations also led to a substantial reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential (Figure S8E).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of glutamine consumption synergizes with pimozide to induce mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress that blunts GBM cell growth

(A and B) Representative transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the mitochondria in U251 cells after treatment (A). Scale bar, 500 nm. Red arrows indicate mitochondria. Over 30 mitochondria were quantified (mean ± SEM) (B).

(C) Representative fluorescence images of U251 cells stained with MitoTracker and CellROX Deep Red after treatment as (A). CellROX-positive signals were quantified by ImageJ in more than 30 cells (mean ± SEM) (right). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(D) Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measured by Seahorse XF24 in U251 cells after treatment as (A) (top, mean ± SD, n = 3). Oligo, oligomycin; FCCP, carbonyl cyanide 4-trifluoromethoxy-phenylhydrazone; Rot, rotenone. Relative basal and maximal respiration was normalized with the untreated control cells (bottom).

(E) Western blotting analysis of U251 cells after treatment as in (A) for 48 h.

(F) Representative fluorescence images of U251 cells stained with MtioTracker and CellROX Deep Red after treatment as in (A) in the presence or absence of GSH (3 mM) for 24 h. Scale bar, 10 μm. CellROX-positive signals were quantified by ImageJ in over 30 cells (mean ± SEM) (right). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(G) Western blotting analysis of the cytosol (Cyto), mitochondrial (Mito), and total lysates of U251 cells after treatment as in (A) for 48 h.

(H) Relative free FA, cardiolipin, and free cholesterol levels in U251 cells after treatment as in (A).

(I) Representative fluorescence images of U251 cells stained with MitoTracker and CellROX Deep Red after treatment as in (A) in the presence or absence of the mixture of cholesterol (3 μg/mL) and FAs (palmitate: 20 μM, oleic acid: 20 μM, palmitoleic acid: 5 μM). CellROX-positive signals were quantified by ImageJ in over 30 cells (mean ± SEM) (right). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(J) Western blotting analysis of U251 cells after treatment as in (A) for 48 h. Experiments except TEM (A, twice) were repeated three times. The results were representatives of one of three (two) independent experiments. Statistical significance for all the results was determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons adjustments. See also Figures S8 and S9.

We then investigated whether mitochondrial damage resulted in elevated levels of oxidative stress, leading to the death of GBM cells. Our findings confirmed that the combination of pimozide with GPNA, DON, or CB-839 all led to a significant increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) within mitochondria, as indicated by CellROX staining (red) together with MitoTracker staining (green), while single-drug treatments only induced a modest rise in ROS levels (Figures 5C, S8C and S8D). These combinations also caused a substantial reduction in mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate (OCR) (Figure 5D), along with increased levels of apoptotic markers such as cleaved caspase-3, -6, and poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) (Figures 5E and S8F). In contrast, supplementation with GSH in these cells markedly reduced the ROS induced by the drug combination, restored mitochondrial morphology to a tubular and elongated structure like untreated cells (Figures 5F, S9A, and S9B), prevented the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria into the cytosol, inhibited apoptotic marker cleavage, and rescued GBM cells from death (Figures 5G, S9C, and S9D).

Pimozide, as shown in Figures 2C and 2D, inhibits the release of cholesterol and FAs from LDs and LDL hydrolysis. On the other hand, the inhibition of glutamine consumption reduces de novo lipid synthesis by suppressing SREBP-1 activity, as demonstrated in Figures 4A–4E and S7A–S7D. We then investigated whether combining pimozide with inhibitors of glutamine consumption significantly reduced cellular cholesterol and FA levels, resulting in synergistic effects in killing GBM cells. Indeed, the combination of pimozide with GPNA, DON, or CB-839 all led to a marked reduction in levels of free FAs, cardiolipin, and free cholesterol (Figure 5H). Supplementation with cholesterol and FAs (a mixture of palmitate 16:0, palmitoleic acid 16:1, and oleic acid 18:1) significantly attenuated the ROS levels induced by the combination treatments (Figures 5I and S9E), restored mitochondrial morphology to a state resembling untreated cells (Figures 5I and S9E), and reduced cytochrome c release and caspases-3/9 and PARP cleavage (Figures 5J and S9F), ultimately rescuing GBM cells from the combination-induced cell death (Figure S9G).

Combining glutamine consumption inhibition with pimozide effectively suppresses GBM growth in vivo

We next assessed the initial efficacy of pimozide in a primary GBM30 cells-derived subcutaneous xenograft mouse model. Pimozide treatment showed only marginal inhibition of tumor growth (Figures S10A–S10C). Through IHC and Nessler’s staining analyses, we observed that pimozide treatment significantly increased SREBP-1, ASCT2, ammonia, and FASN levels in tumor tissues from pimozide-treated mice tumors as compared to control tumors (Figure S10D). We then investigated whether pharmacological inhibition of ASCT2 with GPNA or inhibition of GLS with CB-839 could sensitize GBM tumor to pimozide treatment. Strikingly, the combination of either GPNA or CB-839 with pimozide demonstrated a powerful synergistic antitumor effect in this subcutaneous xenograft model (Figures 6A and 6B). We further tested the effects of combining the SREBP-1 inhibitor fatostatin with pimozide in GBM cells and found that they synergistically damaged mitochondria, increased ROS (Figures S11A and S11B), reduced mitochondria membrane potential (Figures S11C and S11D), triggered apoptosis (Figure S11E), and eradicated GBM cells pre-formed colonies and effectively killed GBM cells in vitro (Figures S11F and S11G). Importantly, in an in vivo xenograft model, this combination therapy also synergistically inhibited GBM growth (Figures 6C and 6D). Encouragingly, examination via H&E staining did not reveal obvious toxic effects in vital organs such as the kidney, liver, pancreas, spleen, brain, small intestine, and lager intestine after drug treatment of the mice (Figures S12A–S12G). These findings suggest the potential clinical promise of this combination therapy in the treatment of GBM.

Figure 6.

Combining an inhibitor of glutamine uptake or its consumption with pimozide synergistically suppresses tumor growth in GBM xenografts and patient-derived organoids

(A–D) Tumor growth curve of GBM30-derived subcutaneous xenografts (n = 6, mean ± SD) treated with pimozide (15 mg/kg/day, intraperitoneal [i.p.]) in combination with or without GPNA (60 mg/kg/day, i.p.), CB-839 (20 mg/kg/day, i.p.) (A), or Fatostatin (20 mg/kg/day, i.p.) (C) for 14 days. Tumors were imaged after 14 days treatment and weighed (B and D).

(E) Schematic diagram illustrating the development of GBM patient-derived organoids for drug treatment. Created with BioRender.com.

(F) Representative imaging of GBM organoids derived from 3 patients stained with Hoechst33342 (blue, nuclei), Calcein-AM (green, live cells), and propidium iodide (PI, red, dead cells) after treatment with pimozide (PMZ, 3 μM), GPNA (1 mM), DON (10 μM), CB-839 (100 nM), or Fatostatin (Fato, 5 μM) alone or combination for 3 days. BF, bright field. PI intensity was quantified by ImageJ in ≥10 organoids derived from each patient (mean ± SD).

(G) Representative bright-field images (top), size, and viabilities (bottom) of GBM organoids after treatments as (F) for 10 days. The maximum length of organoids was measured by ImageJ (size). Viabilities of organoids were measured by CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay. Biological statistic for all the results in Figure 6 was examined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons adjustments. See also Figures S10–S12.

We next examined three GBM patient-derived organoids to validate the efficacy of our proposed therapy. Notably, organoids have been recognized as a more physiologically relevant model of human cancer, including GBM, as it sustains human tumor microenvironment.49 Clearly, our results showed that combining pimozide with GPNA, DON, CB-839, or fatostatin dramatically induced tumor cell death (propidium iodide, PI staining) (Figure 6F) and significantly reduced organoid size and inhibited tumor cell viability (Figure 6G) in all GBM patient-derived organoids.

We further determined the antitumor effects of the combination of pimozide with GPNA, CB-839, or fatostatin in intracranial GBM mouse models, in both female and male mice, by using primary GBM cells (GBM30) derived from a female patient (Figure 7A). By magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) conducted on day 12 after drug treatments, we found that all combinations significantly inhibited GBM tumor growth in the mouse brain of female mice compared to the control and single-drug treatment groups (Figures 7B, S12H, and S12I). Kaplan-Meier plot analysis demonstrated that all the combinations significantly extended the overall survival of GBM-bearing mice compared to the control and single-drug treatment groups, and there was no obvious difference in response between female and male mice (Figures 7C and 7D). Through IHC and ammonia staining, we observed that pimozide treatment significantly increased SREBP-1, ASCT2, ammonia, and FASN levels in intracranial tumor tissues (Figure 7E). Importantly, these increases were effectively reversed by combining pimozide with GPNA, CB-839, or fatostatin (Figure 7E). IHC analysis further revealed that these combinations significantly reduced Ki67 staining, a marker of cell proliferation, while there were marked increase in cleaved caspase-3 levels in the tumor tissues (Figure 7E). Moreover, these combinations significantly increased the therapeutic effects of radiation on GBM growth, effectively suppressing intracranial tumor growth and extending the survival of female mice bearing GBM (Figures 7F–7H). We also measured mouse blood ammonia levels following drug treatments. Interestingly, ammonia levels in mouse blood were significantly increased approximately 1.5-fold in pimozide-treated mice compared with control mice without drug treatment, which were restored to the basal levels as those of control mice when combined with GPNA, CB-839, or fatostatin treatments (Figure S12J).

Figure 7.

Combining inhibition of glutamine metabolism with pimozide significantly suppresses tumor growth in orthotopic GBM models

(A) A schematic diagram outlining the treatment schedule for a GBM30-derived orthotopic xenograft model by pimozide (25 mg/kg/day, intraperitoneal [i.p.]), GPNA (60 mg/kg/day, i.p.), CB-839 (20 mg/kg/day, i.p.), or Fatostatin (20 mg/kg/day, i.p.) alone or in combination.

(B) Representative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of female mouse brains from the GBM30-derived orthotopic models after treatment as outlined in (A) for 12 days. The tumor border was outlined by a pink circle (left). Tumor volume was quantified by ITK-SNAP (Version 3.8.0) (right).

(C and D) Kaplan-Meier plot analysis of overall survival in GBM-bearing mice, in both female and male mice (n = 7/each sex) after treatment as outlined in (A). Significance was determined by a log rank test. NS, not significant.

(E) Representative IHC (proteins) and Nessler’s (ammonia, dark brown dots) staining images of the intracranial GBM30-derived tumors isolated from the mice at the indicated days (endpoint) after treatment as outlined in (A). Six separate areas from each tumor were quantified by ImageJ (mean ± SEM, n > 1,000 cells) (right). Scale bars, 50 μm for IHC. 100 μm for ammonia staining.

(F–H) A schematic diagram outlining the treatment schedule for a GBM30-derived orthotopic xenograft model (female) by pimozide, GPNA, CB-839, or Fatostatin alone or in combination with radiation (F). Representative MRI images of mouse brains from the GBM30-derived orthotopic models (n = 7) after treatment for 12 days (G). Mouse overall survival was analyzed by Kaplan-Meier plot (H). Significance was determined by a Log rank test. Statistical significance from (B–G) was determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons adjustments. See also Figures S12 and S13.

Discussion

A major obstacle in effectively treating GBM is the development of tumor resistance to nearly all current treatments.1,2 Therefore, understanding the underlying mechanisms of this resistance is crucial for the development of successful GBM therapy. Antipsychotic drugs have long been studied for their potential antitumor properties.4,10,50 However, their translation into clinical cancer therapy has been hampered by issues of tumor resistance, despite the proposal of various antitumor mechanisms for this large class of drugs.6,21 This aspect has received limited attention in previous research. Our study sheds light on a mechanism of resistance to the antipsychotic drug pimozide in GBM.

Metabolic plasticity empowers GBM resistance to lysosome inhibition

Our findings reveal that pimozide activates a feedforward loop involving SREBP-1 activation and increased glutamine uptake, which ultimately promotes GBM resistance to therapy (Figure S13). Additionally, our study highlights the remarkable adaptability of GBM cells in response to lysosome inhibition, demonstrating their ability to switch between metabolic pathways to ensure survival. Specifically, when one metabolic resource, such as cholesterol and FAs, is limited due to the inhibition of lysosomal hydrolysis, GBM cells can compensate by upregulating an alternative pathway, namely glutamine uptake and reductive carboxylation-mediated de novo lipid synthesis, to replenish these crucial building blocks (Figure S13). This metabolic switch identified in our study has important implications for the development of combination therapies to counteract this adaptive response and improve treatment outcomes in GBM. Overall, our research opens possibilities for understanding and overcoming resistance mechanisms in GBM and potentially in other cancers. It emphasizes the importance of metabolic adaptability in cancer cells and highlights the potential of combination therapies to address this challenge.

Unexpected role of SREBP-1 in regulating glutamine metabolism

The discovery of SREBP-1’s role in regulating glutamine metabolism shifts the conventional thoughts regarding the functions of SREBPs. For over three decades, SREBPs have been thought mainly to regulate cholesterol and FA biosynthesis.38 However, our study demonstrates that SREBP-1 has a role in governing glutamine metabolism. The identification of the feedforward loop involving SREBP-1, ASCT2, glutamine uptake, and ammonia release provides a comprehensive review of how SREBP-1 can orchestrate two critical metabolic pathways simultaneously: lipid synthesis and glutamine consumption (Figure S13). Moreover, our recent discovery that ammonia released by glutamine catabolism can activate SREBP cleavage and nuclear translocation46 further underscores the intricate connections between metabolic pathways and transcriptional regulation. These insights stand to impact not only cancer research but also our broader understanding of metabolic regulation in health and disease.

Combining glutamine metabolism and lysosome inhibition is an effective strategy targeting cancers

The combination of targeting glutamine metabolism via ASCT2 or GLS inhibition along with pimozide represents a promising strategy to broadly inhibit glutamine’s functions, limit lipid supplies for tumor cells, and effectively kill GBM cells, as illustrated in Figure S13. However, as mentioned, targeting GLS alone has shown limited success in clinical trials,51 a trend that aligns with our study’s findings indicating that CB-839 alone is insufficient to restrain tumor growth in an intracranial GBM model. Many clinical trials have explored the use of CB-839 in combination with various anticancer agents, such as chemotherapeutics, molecule target inhibitors, and immune checkpoint inhibitors. But these combinations often lack clear mechanistic synergies and have not yielded promising results. In contrast, the synergistic combination of CB-839 with pimozide, as supported by our research, provides a rational and mechanistically driven approach (Figure S13). Moving this combination to clinical trials could hold promise for improving GBM therapy if successful.

Critical role of cholesterol and FAs in preserving mitochondrial integrity and function

Cholesterol and FAs are essential lipids for cell function.31,52,53,54 Maintaining an adequate supply of these lipids is essential for supporting cell proliferation. Despite this knowledge, the precise mechanism underlying tumor cell death due to lipid deficiency has remained elusive. Our study brings to light the fact that mitochondria are particularly susceptible when confronted with a shortage of cholesterol and FAs. Consequently, when we inhibit lipid synthesis and the release of lipids from LDs and LDL through a combination of inhibiting glutamine uptake or consumption and targeting lysosomal function, it leads to severe mitochondrial damage and a surge in oxidative stress. These factors collectively lead to apoptotic cell death in GBM. Our findings provide insights into the pivotal role of mitochondria in responding to lipid deficiencies, offering valuable implications for potential therapeutic strategies not only for GBM but also for other cancers.

Limitations of the study

Though the combination of glutamine metabolism inhibitors with pimozide showed significant antitumor effects, the orthotopic GBM-bearing mice still died around approximately 40 days. We think the main reason for GBM-bearing mice maintaining resistance to the combination treatments is that the BBB limits the effective drug doses in the brain, leading to residual tumor growth and mouse death. This reasoning is supported by the results of the efficacy of drug treatments in the GBM subcutaneous tumor model. In that model, each single drug showed a modest antitumor effect, while the single-drug treatments did not show significant antitumor effects in the orthotopic model. This is a common issue for drug treatment in brain tumors. In a future study, we need to utilize a strategy, such as localized ultrasound, to further increase drug penetration into GBM tissues to completely eradicate tumor cells. The intracerebral drug levels should also be measured, providing insights for future clinical tests. Additionally, despite the likelihood of the aforementioned explanation, we cannot exclude the involvement of glycolysis and pyruvate carboxylation-mediated anaplerosis in tumor resistance. We also cannot exclude the possibility of drug efflux by efflux transporters, leading to the insufficient drug concentrations in GBM tissues. These possibilities should be tested in follow-up studies.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Deliang Guo (deliang.guo@osumc.edu).

Materials availability

All plasmids and cell lines generated in this study are available from the lead contact with a completed materials transfer agreement.

Data and code availability

-

•

All the data reported in this paper are available from the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NINDS and NCI (USA) grants NS104332, NS112935, NS141312, and CA240726 to D.G. and CA227874 to D.G. and A.C. We also appreciate the support from the OSUCCC-Pelotonia Idea grant and Urban and Shelly Meyer Fund for Cancer Research to D.G. MRI imaging was taken from the OSU Small Animal Imaging Core (SAIC) that is supported by the grant P30 CA016058.

Author contributions

D.G. conceived the ideas and led the project. Y.Z. and D.G. designed the experiments. Y.Z., F.G., and L.M. performed the experiments and analyzed data. X.Y., L.H., and X.Z. performed metabolomics study and analysis. S.M., E.X., P.-K.L., and X.C. synthesized fluorescence-labeled pimozide. A.P.B. and A.C. prepared glioma TMA. E.L. constructed ASCT2/SLC1A5 gene promoter. H.S., Y.F., Y.K., C.-Y.C., Y.G., and Q.W. helped in animal studies. X.M. helped with heatmap and statistical analysis. Y.Z. and D.G. wrote the manuscript. We also thank Xipeng Ma from the University of Louisville for helping upload the metabolomics data to the National Metabolomics Data Repository (NMDR), the Metabolomics Workbench. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Cleaved Caspase 3 (Asp175) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat #: 9661; RRID: AB_2341188 |

| Cleaved Caspase-9 (Asp330) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat #: 9501; RRID: AB_331424 |

| Rabbit Anti-PARP monoclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat #: 9532; RRID: AB_659884 |

| Rabbit anti-COX IV (3E11) monoclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat #: 4850; RRID: AB_2085424 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: A-11036; RRID: AB_10563566 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: A-11004; RRID: AB_2534072 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: A-11034; RRID: AB_2576217 |

| HA-Tag (C29F4) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: 3724S; RRID: AB_1549585 |

| SCD1 (M38) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: 2438S; RRID: AB_823634 |

| CD71 (D7G9X) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: 13113S; RRID: AB_2715594 |

| FASN (C20G5) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: 3180S; RRID: AB_2100796 |

| Horse Anti-Mouse IgG Antibody (H + L), Biotinylated | Vector Laboratories | Cat #: BA-2000; RRID: AB_2313581 |

| Horse Anti-Rabbit IgG Antibody (H + L), Biotinylated | Vector Laboratories | Cat #: BA-1100; RRID: AB_2336201 |

| ASCT2 (SLC1A5) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: HPA035240; RRID: AB_10604092 |

| Mouse Anti-β-Actin Monoclonal Antibody | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: A1978; RRID: AB_476692 |

| Monoclonal Anti-Flag® M2 antibody | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: F3165; RRID: AB_259529 |

| GLS | Abcam | Cat #: ab93434; RRID: AB_10561964 |

| Anti-Ki67 antibody [SP6] | Abcam | Cat #: ab16667; RRID: AB_302459 |

| Cytochrome c antibody | BD Biosciences | Cat #: 556433; RRID: AB_396417 |

| Mouse Anti-SREBP-1 | BD Biosciences | Cat #: 557036; RRID: AB_396559 |

| Mouse Anti-SREBP-2 | BD Biosciences | Cat #: 557037; RRID: AB_396560 |

| Normal mouse IgG | Merck Millipore | Cat #: NI03; RRID: AB_490557 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Adeno-null | Geng et al.31 | N/A |

| Adeno-nSREBP-1a | Geng et al.31 | N/A |

| Adeno-nSREBP-1c | Geng et al.31 | N/A |

| Adeno-nSREBP-2 | Geng et al.31 | N/A |

| Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: FEREC0114 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Glioma tumor tissue microarray (TMA) | Department of Pathology at the OSU Medical Center | https://pathology.osu.edu |

| Human GBM patient samples | Department of Pathology at the OSU Medical Center | https://pathology.osu.edu |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Pimozide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: P1793 |

| Fluoxetine hydrochloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: F132 |

| Haloperidol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: H1512 |

| Imipramine hydrochloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: I7379 |

| Clozapine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: C6305 |

| Olanzapine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: O1141 |

| Perphenzaine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: P6402 |

| Promazine hydrochloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: P6656 |

| Sulpiride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: S2190000 |

| (L-γ-Glutamy-p-nitroanilide) hydrochloride (GPNA) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: G6133 |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 67-68-5 |

| 6-Diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: D2141 |

| Cholesterol Oxidase from microorganisms | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: C8868 |

| B-27 serum-free Supplement | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: 17504044 |

| TrypLE Express | Gibco | Cat #: 12604021 |

| Telaglenastat (CB-839) | Adooq Bioscience | Cat #: A14396 |

| Fatostatin | ChemBridge Corporation | Cat #: 5533803 |

| Human epidermal growth factor (EGF) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: E9644 |

| DMEM medium without Amino Acids | MyBioSource | Cat #: MBS6120661; Lot #: L22080101 |

| D-(+)-Glucose solution | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: G8644 |

| Gibco™ L-Glutamine | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: A2916801 |

| Gibco™ Sodium pyruvate | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: 11360070 |

| Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: F5392 |

| Heparin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: H3393 |

| Non-essential Amino Acid Solution | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: M7145 |

| GlutaMax | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: 35050061 |

| HEPES | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: BP299100 |

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 158127 |

| Hydrogen peroxide | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: H323 |

| eBioscience™ IHC Antigen Retrieval Solution-High pH (10x) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: 00-4956-58 |

| Hematoxylin QS Counterstain | Vector Laboratories | Cat #: H-3404 |

| Nessler’s reagent | Ricca Chemical Company | Cat #: 5250-4 |

| 6,8-difluoro-7-hydroxy-2-oxo-2h-chromene-3-carboxylic acid | AmBreed | Cat #: 1C65038; CAS #: 215868-31-8 |

| N-Boc-8-bromooctan-1-amine | Advanced ChemBlocks Inc | Cat #: P41296; CAS #: 142356-35-2 |

| Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) | Corning | Cat #: 15–0312 CV |

| DMEM/F-12 Flex Media | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: A2494301 |

| L-Glycine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: CDBC7825 |

| L-Arginine monohydrochloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: A6969 |

| L-Cystine dihydrochloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: C6727 |

| L-Histidine monohydrochloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: H5659 |

| L-Isoleucine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: I7403 |

| L-Leucine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: L8000 |

| L-Lysine monohydrochloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: L8662 |

| L-Methionine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: M5308 |

| L-Phenylalanine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: P5482 |

| L-Serine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: S4311 |

| L-Threonine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: T8441 |

| L-Tryptophan | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: T8941 |

| L-Tyrosine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: T8566 |

| L-Valine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: V0513 |

| Bromophenol blue sodium salt | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: B8026 |

| Methanol | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: BPA412P4 |

| Lenti-X Concentrator | Clontech | Cat #: 631231 |

| TRIzolTM Reagent | Invitrogen | Cat #:15596018 |

| TWEEN® 80 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #:P8074 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| PowerUpTM SYBRTM Green Master Mix | Applied Biosystems | Cat #: A25778 |

| Qproteome Mitochondria Isolation Kit | QIAGEN | Cat #: 37612 |

| LysoSensor™ Yellow/Blue dextran | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: L22460 |

| DQ-green BSA | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat #: D12050 |

| BODIPY™ 493/503 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: D3922 |

| LysoTracker™ Red DND-99 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: L7528 |

| Low-Density Lipoprotein from Human Plasma, BODIPY™ FL-LDL complex | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: L3483 |

| Rhodamine 123 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: R302 |

| CellROX™ Deep Red reagent | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: C10422 |

| MitoTracker™ Green FM Dye | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: M7514 |

| Free fatty acid assay Kit (Quantification) | Abcam | Cat #: ab65341 |

| Cardiolipin assay Kit | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: MAK362 |

| Amplex Red Cholesterol Assay Kit | Invitrogen | Cat #: A12216 |

| Glutaminase (GLS) Activity Assay Kit (Fluorometric) | Abcam | Cat #: ab284547 |

| BCA protein assay kit II | Abcam | Cat #: ab287853 |

| RIPA lysis buffer | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: NC9484499 |

| EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 11836170001 |

| Phosphatase inhibitor | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 4906837001 |

| Hoechst 33342 Solution | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: 62249 |

| Glo Lysis buffer | Promega | Cat #: E266A |

| Promega Renilla-Glo™ Luciferase Assay System | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #: PRE2710 |

| X-tremeGENETM HP DNA Transfection Reagent | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 6366236001 |

| ECL kit | Cytiva Amersham | Cat #: RPN2106 |

| iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit | Bio-rad | Cat #: 170-8891 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Metabolomics data | This paper | NMDR: ST003362 Project DOI: https://doi.org/10.21228/M8QJ9B |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| GBM patient-derived primary cell, GBM30 | The Ohio State University | N/A |

| GBM patient-derived primary cell, GBM6 | Mayo clinic | N/A |

| GBM patient-derived primary cell, GBM26 | Mayo clinic | N/A |

| Human GBM cell: U251 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 09063001; |

| Human GBM cell: U87 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 89081402; |

| Human GBM cell: U373 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 08061901; |

| Human GBM cell: T98 | ATCC | Cat #: #CRL-1690™ ATCC; |

| Human GBM cell: LN229 | ATCC | Cat #: CRL-2611™; |

| Human embryonal kidney cell: 293FT | Invitrogen™ | Cat #: R70007 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Athymic NCr-nu/nu, outbred, NCI stock | Charles River Lab | Strain # 553 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| shSREBP-1 #1 (TRCN0000414192) | This paper | AGACATGCTTCAGCTTATCAA |

| shSREBP-1 #2 (TRCN0000422088) | This paper | TGAGGCTCCTGTGCTACTTTG |

| shSREBP-2 #1 (TRCN0000020668) | This paper | GACCTGAAGATCGAGGACTTT |

| shSREBP-2 #2 (TRCN0000020666) | This paper | GCAACAACAGACGGTAATGAT |

| shASCT2 #1 (TRCN0000043118) | This paper | CTGGATTATGAGGAATGGATA |

| shASCT2 #2 (TRCN0000288922) | This paper | GCCTGAGTTGATACAAGTGAA |

| Primers for RT-qPCR (Human) | This paper | See method details |

| Primers for ASCT2 promoter (Human) | This paper | See method details |

| Primers for Chip assay (Human) | This paper | See method details |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pLKO.1 | Addgene | RRID: Addgene_24150 |

| pMD2.G | Addgene | RRID: Addgene_12259 |

| psPAX2 | Addgene | RRID: Addgene_12260 |

| pGEX-GST-mCherry-D4H∗ | Geng et al.31 | N/A |

| pRL Renilla Luciferase Control Reporter Vectors | Promega | Cat #: E2261 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism Ver. 9.41 | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com/features |

| TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) | National Cancer Institute | https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga |

| SynergyFinder | Ianevski et al.55 | https://synergyfinder.fimm.fi/ |

| Biorender | Biorender | https://www.biorender.com/ |

| JASPAR2024 | Rauluseviciute et al.45 | https://jaspar.elixir.no/ |

| ITK-SNAP (Version 3.8.0) | The Ohio State University | N/A |

| Chem draw | NCH Software | N/A |

| ZEN 2 (blue edition) | Zeiss | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/us/downloads.html |

| ImageJ | ImageJ | https://imagej.net/Downloads |

| Microsoft Excel | Microsoft | https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel |

Experimental model and study participant details

Cell lines and culture

Authenticated (short tandem repeat profiling) human GBM cell lines, U251 (Male) and U373 (Male) from Sigma, U87 (HTB-14) (Female), T98 (CRL-1690) (Male), LN (CRL-2611) (Female) cells American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), supplemented with 5% HyClone fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 4 mM glutamine.

Authenticated GBM30 (Female), GBM6 (Male) and GBM26 (Male) are primary GBM patient-derived cell lines that were previously molecularly characterized and described.56 They were cultured in SILAC Advanced DMEM/F-12 Flex Media supplemented with 1×B-27 serum-free supplements, 2 mg/mL heparin, 2 mM glutamine, 50 ng/mL EGF, and 50 ng/mL fibroblast growth factor (FGF). GBM30-luc cells stably express luciferase (luc) and were previously described.46 All cells were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Cell lines in this study have different morphologies and growth rates, and any signs of contamination were constantly monitored. All cell lines used in this study were free from mycoplasma contamination based on PCR detection and were regularly maintained with mycoplasma reagent.

Clinical samples

The collection and analysis of human tissue were approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board (IRB) under ref. 2015C0067. The clinical specimens were collected under a waiver of consent as the specimens are de-identified to recipient investigators. Individual glioma tumor and adjacent brain tissues, glioma tumor tissue microarray (TMA) containing 47 paired (tumors and matched adjacent brain tissues) and 176 unpaired glioma tumor tissues were from the Department of Pathology at the OSU Medical Center. Frozen normal brain tissues were obtained from cerebral autopsy samples from non-cancer individuals. Neuro-pathology reports showed that the brain tissues were normal. All samples tested negative for HIV and hepatitis B. The details of patients’ information, i.e., gender and age, are included in Table S1. TMA slides were scanned using ScanScope and analyzed using ImageScope v11 software (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA, USA). The staining intensity of tissues was graded as 0, 1+, 2+, or 3+.

Intracranial and subcutaneous xenograft models

For GBM orthotopic xenograft model, 5×104 patient-derived neurosphere GBM30 cells expressing luciferase in 5 μL PBS were intracranially injected into 5–6 week old female and male athymic nude mice (NCr-nu/nu, Charles River Lab strain #553), which are immune-compromised and lack T-cells, using a stereotactic system. Tumor growth was monitored at day 7 and day 18 after injection by using an OSU Small Animal Imaging Core and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), respectively. Seven mice were injected for each group. For drug treatment, pimozide (15, 25 mg/kg/day), GPNA (60 mg/kg/day), CB-839 (20 mg/kg/day) were formulated with DMSO (final concentration 10%), and then Tween-80 (final concentration 10%, Sigma, 9005656) in PBS; Fatostatin (20 mg/kg/day) was formulated with DMSO and Tween-80 in 0.9% Sodium Chloride (McKesson Medical-Surgical, #R5201-01) and administrated to mice by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection when tumors were established 7 days after implantation. Mice were observed until they became moribund, at which point they were sacrificed. Survival until the onset of neurologic symptoms was applied for survival curves.

For subcutaneous xenograft models, 200×104 GBM30 cells were subcutaneously injected into 6 week-old female athymic nude mice. Drugs were treated when tumor size reached approximately 80 mm3. Mice weight was measured every day and tumor size was measured every two days. Tumor volume was calculated by the formula: ½×Short×Short×Long. Mice were housed 5 per cage in a conventional barrier facility on a 12 h light/dark cycle at 22°C with free access to water and food. All animals were maintained within the barrier vivarium facilities under highest level of sterility and routinely monitored for health status per OSU IACUC guidelines, and not treated with any drug or test article unless specified. All mice experiments were performed according to the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Ohio State University (ref. 2011A00000064-R4).

Organoid culture

GBM patient tumors were dissociated using a human tumor dissociation kit (Miltenyi Biotech; Cat# 130-095-929) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Dissociated tissue was filtered via a 70 μm filter and subjected to isolation of human tumor cells using a human cancer cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotech; Cat#130-108-339). These tumor cells were cultured in ultra-low plate with SILAC Advanced DMEM/F-12 Flex Media supplemented with 1×B-27 serum-free supplements, 2 mg/mL heparin, 2 mM glutamine, 50 ng/mL EGF, and 50 ng/mL fibroblast growth factor (FGF) according to a previously published protocol.57,58 The diameter of the organoids was measured with ImageJ. To detect the degree of cell death in organoids, organoid medium was supplemented with Hoechst 33342 (10 μg/mL) (Invitrogen, Cat#H21486), Calcein AM (5μM) (Invitrogen; cat#C3100MP) and PI (10 μg/mL) (Invitrogen; Cat#P1304MP) and incubated for 1 h under the growth condition. Organoids were then imaged on an Echo Revolve fluorescence microscope. The intensity of each organoid’s PI was measured with ImageJ.

The cell viability was measured by CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay according to manufacturer instructions.

Method details

Synergy prediction

For synergy analysis, individual values of relative cell viability from each well were measured and analyzed using online SynergyFinder web application.55 Synergy scores < −10, from −10 to 10, and >10 indicate an antagonistic, additive, and synergistic effect, respectively.

Colony growth assay

The colony growth ability of U251, GBM30, and U373 cells was determined after pimozide treatment with or without different amino acids in full DMEM medium (containing 15 amino acids), i.e., L-Glutamine (4 mM), L-Glycine (0.4mM), L-Arginine monohydrochloride (0.4 mM), L-Cystine dihydrochloride (0.2 mM), L-Histidine monohydrochloride (0.2 mM), L-Isoleucine (0.8 mM), L-Leucine (0.8 mM), L-Lysine monohydrochloride (0.8 mM), L-Methionine (0.2 mM), L-Phenylalanine (0.4 mM), L-Serine (0.4 mM), L-Threonine (0.8 mM), L-Tryptophan (0.8 mM), L-Tyrosine (0.4 mM), L-Valine (0.8 mM).

Cells were first seeded at the density of 2000 cells/well into the 6-well plate and incubated for 6 days in full DMEM medium with 5% FBS until cell colonies were formed (medium was changed every 3 days). Cell medium was then replaced with a fresh DMEM medium without amino acids, in which 14 amino acids from the above list was added, skipping one amino acid each well, respectively, with 1% FBS added in this medium. Pimozide (3 μM) was added into medium to treat for 8 days (medium was changed every 3 days). The medium was pre-warmed in the incubator, which minimizes disturbance to cells caused by medium change. Three replicates were performed for each condition. After 8 days of treatment, colonies were fixed and stained with 1% bromophenol blue sodium salt in 80% methanol for 1 h at room temperature. Then the samples were washed completely with double distilled water and imaged by a GE Amersham Imager 600. Colony numbers were counted by ImageJ.

Stable isotope 13C5-glutamine labeling, polar metabolite and long chain fatty acid sample preparation

300 × 104 U251 cells were seeded in a 15-cm dish for 24 h, then treated with/without Pimozide (3 μM) in a fresh medium containing 1%FBS, 5 mM glucose, 4 mM glutamine for another 24 h. After drug treatment, cells were deprived for 1 h with a serum-free medium containing 5 mM glucose, 0 mM glutamine, and 1 mM pyruvate. 2 mM 13C5-glutamine was added to the media and incubated for 1h. The cells were washed twice with cold PBS and quenched with cold acetonitrile and ultrapure water (4:3, v/v) for 5 min.

Polar metabolites were extracted from the cells using a two-phase liquid-liquid extraction method. Cells were homogenized for 1 min using a Sonic Dismembrator (Fisher Scientific, USA). The homogenized sample was transferred into a 15-mL glass tube, and chloroform was added to the glass tube to make the final solvent, chloroform/acetonitrile/water (2: 4: 3, v/v/v). The mixture was then vortexed for 3 min and centrifuged at 2300 ×g for 8 min. The upper layer was transferred to a fresh tube and lyophilized overnight. The dried sample was reconstituted in 50% acetonitrile and vigorously vortex-mixed for 3 min. The supernatant was transferred into an autosampler vail after centrifugation at 18,000 ×g, 4°C for 20 min for 2DLC-MS analysis.

For long chain fatty acid extraction, cells were homogenized for 1 min. After centrifugation at 18,000 ×g, 4°C for 20 min, the supernatant was transferred into a micro centrifuge tube and lyophilized overnight. The dried sample was reconstituted in 200 μL 50% ethanol, and loaded onto an OASIS HLB Cartridge (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA). The long chain fatty acids were eluted using 600 μL of acetonitrile/methanol (90:10, v/v) after washing with 1 mL of 5% methanol. The eluate was dried under the nitrogen gas flow, reconstituted into 25 μL 75% ethanol, and transferred to an autosampler vial for LC-MS analysis.

LC-MS analysis and data processing

All samples were analyzed on a Thermo Q Exactive HF Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer coupled with Thermo DIONEX UltiMate 3000 UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For polar metabolite profiling, the LC system was equipped with a reversed phase column (RPC, a Waters Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column, 2.1 × 150 mm, 1.8 μm) and a hydrophilic interaction chromatography column (HILIC, a Millipore SeQuant ZIC-cHILIC column, 2.1 × 150 mm, 3 μm). The two chromatographic columns were configured to form a parallel 2DLC-MS system. The mobile phases, gradient, flow rate and column temperature were same with our previous study.59 All samples were analyzed in a random order in positive (+) and negative (−) modes to obtain full MS data for metabolite quantification. For metabolite identification, a pooled sample of each group was analyzed by 2DLC-MS/MS in positive and negative modes at three collision energies, 20, 40, and 60 eV. For analysis of long chain fatty acids, the LC system was equipped with a reversed phase column (RPC, a Waters Acquity UPLC BEH C8 column, 2.1 × 100 mm, and 1.7 μm). Water with 0.1% acetic acid was used as mobile phase A, and acetonitrile with 0.1% acetic acid was as mobile phase B. The flow rate was 0.4 mL/min. The gradient was started with 30% B, held for 3 min, increased to 99% B at 20 min, held for 5 min; then held at 30% B from 25.1 to 28 min. The column temperature was 40°C. All samples were analyzed in negative (−) modes to obtain full MS data and a pooled sample of each group was analyzed by LC-MS/MS in negative modes at three collision energies, 20, 40, and 60 eV.

For LC-MS data analysis, XCMS software was used for spectrum deconvolution60 and MetSign software for metabolite identification, cross-sample peak list alignment, normalization, and statistical analysis.59,61 To identify metabolites, 2DLC-MS/MS data was first matched to our in-house database that contains parent ion m/z, MS/MS spectra, and retention time of authentic standards. Threshold for spectral similarity was set ≥0.4, while thresholds of retention time difference and m/z variation window were respectively set ≤0.15 min and ≤5 ppm 2DLC-MS/MS data without a match with the metabolites in the in-house database were further analyzed using Compound Discoverer software (v 2.0, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany), where MS/MS spectra similarity score threshold was set ≥40 with a maximum score of 100. Those date are included in National Metabolomics Data Repository (NMDR), the Metabolomics Workbench.62

Synthesis of Pacific blue-labeled pimozide

Synthesis of tert-butyl (8-(3-(1-(4,4-bis(4-fluorophenyl)butyl)piperidin-4-yl)-2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)octyl)carbamate (SOH-I-185-01): To the solution of 1-(1-(4,4-bis(4-fluorophenyl)butyl)piperidin-4-yl)-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-one (1.0 eq) in DMF, was added NaH (1.2 eq) and stirred for 15 min. Then, tert-butyl (6-bromohexyl)carbamate (1.0 Eq) was added to the reaction mixture and stirred overnight. The reaction mixture was dissolved in EtOAc and water and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 25 mL). The collective organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated on reduced vapor pressure. The residue was purified by combi flash using 0–100% EtOAc in Hexane gradient (62% yield): 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.01 (bs, 2H), 7.26–7.24 (m, 2H), 7.20–7.15 (m, 3H), 7.08–6.94 (m, 6H), 4.48–4.32 (m, 2H), 3.90–3.82 (m, 3H), 3.12–2.88 (m, 2H), 2.44–2.34 (m, 3H), 2.08–2.00 (m, 3H), 1.78–1.68 (m, 8H), 1.63–1.59 (m, 12H), 1.49–1.43 (m, 8H); (LC-MS (ESI) m/z calculated for C41H54F2N4O3: 688.4164, observed [M + H]: 689.60.

Synthesis of 1-(8-aminooctyl)-3-(1-(4,4-bis(4-fluorophenyl)butyl)piperidin-4-yl)-1,3-dihydro 2H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-one (SOH-I-185-02): To the solution of tert-butyl (8-(3-(1-(4,4-bis(4-fluorophenyl)butyl)piperidin-4-yl)-2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)octyl)carbamate (1.0 eq) in DCM, was added 4N HCl in dioxane (4 eq) and stirred for overnight. The reaction mixture was concentrated on rotavapor and diluted with DCM and neutralized with diluted ammonia and adjusted the pH to 7. The reaction mixture was extracted 10% MeOH in DCM (3 × 25 mL). The collective organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated on reduced vapor pressure. The residue was utilized for the next step without purification.

Synthesis of N-(8-(3-(1-(4,4-bis(4-fluorophenyl)butyl)piperidin-4-yl)-2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)octyl)-6,8-difluoro-7-hydroxy-2-oxo-2H-chromene-3-carboxamide (SOH-I-188-01): To the solution of 6,8-difluoro-7-hydroxy-2-oxo-2H-chromene-3-carboxylic acid in DMF, was added HBTU (1.5 eq), DIPEA (1. 1 Eq), and stirred for 15 min. Then, 1-(8-aminooctyl)-3-(1-(4,4-bis(4-fluorophenyl)butyl)piperidin-4-yl)-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzo[d] imidazol-2-one (1.0 Eq) was added to the reaction mixture and stirred overnight. The reaction mixture was purified by loaded on combi flash using a reverse phase column and 90-10% water in acetonitrile gradient (42% yield, Light yellow solid): 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.77–8.71 (m, 2H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.13–7.05 (m, 6H), 7.00–6.90 (m, 6H), 4.72–4.66 (m, 1H), 3.89–3.82 (m, 3H), 3.64–3.61 (m, 2H), 3.45–3.40 (m, 2H), 3.03–2.75 (m, 9H), 2.12–1.96 (m, 4H), 1.84–1.55 (m, 6H), 1.32 (bs, 6H); 13CNMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 163.3, 162.4, 162.1, 159.8, 153.2, 143.3, 143.2, 141.2, 129.9, 129.8, 129.7, 129.5, 116.14, 121.3, 121.0, 115.7, 115.5, 109.4, 109.2, 108.9, 108.6, 52.0, 48.8, 32.3, 29.6, 29.0, 28.8, 28.0, 26.7, 26.4; HRMS (ESI): calculate for (C46H48F4N4O5+ H+), 813.36336; found, 813.26321; (M + H+).

Synthesis of 6,8-difluoro-7-hydroxy-N-octyl-2-oxo-2H-chromene-3-carboxamide (SOH-I-203-01): To the solution of 6,8-difluoro-7-hydroxy-2-oxo-2H-chromene-3-carboxylic acid in DMF, was added HBTU (1.5 eq), DIPEA (1. 1 Eq), and stirred for 15 min. Then, octan-1-amine (1.0 Eq) was added to the reaction mixture and stirred overnight. The reaction mixture was directly loaded on combi flash and purified by using a reverse phase column and 90-10% water in acetonitrile gradient (52% yield, Colorless solid): 1HNMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.70 (bs, 1H), 8.49 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (dd, J = 1.6 Hz, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 1.44 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 1.21–1.18 (m, 12H), 0.78 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H); 13CNMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.3, 160.1, 150.6, 147.5, 141.0, 140.9, 140.5, 140.4, 138.0, 138.0, 116.7, 111.0, 111.0, 110.85, 110.82, 109.9, 109.84, 31.6, 29.4, 29.1, 29.0, 26.8, 22.5, 14.4; (LC-MS (ESI) m/z calculated for C18H21F2NO4: 353.143, observed [M + H]: 354.3.

Cell proliferation

3×104 cells/well were seeded in 12-well plates, and washed with PBS after 24 h, followed by addition of fresh medium with 1% FBS, 5 mM glucose and 1mM pyruvate and supplemented with or without 3 μM pimozide, 1 mM GPNA,100 nM CB-839, 10 μM DON or/and 4 mM glutamine for 1, 2, 3, 4 days. Live cells were counted at the indicated times using a hemocytometer after trypan blue staining.

Sphere formation assay

A total of 2000 GBM30 cells were incubated in neurobasal medium with 1×B-27 serum-free supplements, 2 mg/mL heparin, 2 mM glutamine, 50 ng/mL EGF, and 50 ng/mL FGF in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The number of spheres were counted 3 days and 6 days after cell seeding and treatment. All the experiments were performed in triplicate.

Preparation of Cell membrane fractions

Cell membranes were isolated as previously described.43 Briefly, cells were washed once with PBS and harvested by scraping. Cells were resuspended in a buffer containing 10 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.6), 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM sodium EDTA, 1 mM sodium EGTA, 250 mM sucrose and a mixture of protease inhibitors, 5 μg/mL pepstatin A, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 0.5 mM Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mM DTT (DL-Dithiothreitol), and 25 μg/mL ALLN (Calpain Inhibitor I) for 30 min on ice. Extracts were passed through a 22G × 1-1/2 inch needle 30 times and centrifuged at 900 × g at 4°C for 5 min to remove nuclei. The supernatants were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. For subsequent western blot analysis (for ASCT2 and CD71 protein), the pellet was dissolved in 0.1 mL of SDS lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 100 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) SDS, 1 mM sodium EDTA, and 1 mM sodium EGTA) and designated “membrane fraction”. The membrane fraction was incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and protein concentration was determined by reading SpectraMax Plus 384 (Molecular Devices). One μL of bromophenol blue solution (100×) was added before the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma.

Mitochondria and cytosol Fractionation

The mitochondrial proteins were prepared using Qproteome Mitochondria Isolation Kit (QIAGEN, #37612) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were harvested and washed with PBS, and resuspended with Lysis buffer and incubated at 4°C for 10 min. The cells were centrifuged at 1,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, and the supernatants were used as the cytosolic fractions. Pellets were resuspended in disruption buffer and disrupted by using a 21G needle and a syringe. Following a centrifugation at 1,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, the supernatants were transferred to new tubes and centrifuged at 6,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. The pellets containing mitochondria were resuspended in mitochondria storage buffer and centrifuged at 6,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min. Pellets were then resuspended in mitochondria storage buffer and protein concentration was determined.

Western blotting