Abstract

An intron module was developed for Saccharomyces cerevisiae that imparts conditional gene regulation. The kanMX marker, flanked by loxP sites for the Cre recombinase, was embedded within the ACT1 intron and the resulting module was targeted to specific genes by PCR-mediated gene disruption. Initially, recipient genes were inactivated because the loxP-kanMX-loxP cassette prevented formation of mature transcripts. However, expression was restored by Cre-mediated site-specific recombination, which excised the loxP-kanMX-loxP cassette to generate a functional intron that contained a single loxP site. Cre recombinase activity was controlled at the transcriptional level by a GAL1::CRE expression vector or at the enzymatic level by fusing the protein to the hormone-dependent regulatory domain of the estrogen receptor. Negative selection against leaky pre-excision events was achieved by growing cells in modified minimal media that contained geneticin (G418). Advantages of this gene regulation technique, which we term the conditional knock-out approach, are that (i) modified genes are completely inactivated prior to induction, (ii) modified genes are induced rapidly to expression levels that compare to their unmodified counterparts, and (iii) it is easy to use and generally applicable.

INTRODUCTION

Co-ordinated regulation of gene expression is essential to the survival of all organisms, as it is critical for growth, development and response to external stimuli. Deviation from the normal program of human gene expression can lead to disease. Gaining experimental control over the expression of specific genes is often an early objective in studies of basic physiological processes, as well as pathological states.

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has emerged as a popular model organism because it is highly amenable to genetic and biochemical manipulation. Equally important is the fact that numerous yeast genes are structurally and functionally related to genes in higher eukaryotes (1). The expression of native as well as foreign genes in yeast has generally relied on creating transcriptional fusions with well-characterized yeast promoters. Non-inducible promoters, such as those found at CYC1, ADH1, TEF2 and GPD, are used for constitutive expression of heterologous genes. Owing to the different strengths of these promoters, expression levels spanning three orders of magnitude can be obtained (2). Inducible promoters, such as those found at GAL1, MET25 and CUP1, are used when conditional expression is required. GAL1 and CUP1 are induced by exposure to galactose and copper, respectively, whereas MET25 is induced by the absence of methionine. In general, these promoters respond rapidly to stimulating conditions (30 min for maximal CUP1 response) and produce large changes in expression level upon induction (1000-fold for GAL1) (3,4). The use of inducible promoters, however, is subject to limitations. They can yield undesirable levels of over-expression, a factor that can cause non-physiological consequences. In addition, inducible promoters are not entirely ‘off’ in the absence of inducer. Low-level basal expression can be significant, which is problematic if the expression of a toxic gene must be controlled.

Here, we describe an alternative approach for controlling gene expression. The method takes advantage of an engineered intron module that can be targeted to any gene of interest by homologous recombination. Initially the embedded intron thwarts production of a functional transcript because it contains inhibitory sequences. However, the inhibitory sequences can be eliminated from DNA by inducible site-specific recombination, thereby permitting production of full-length, spliceable transcripts, at levels comparable to the unmodified gene. We show that expression of test genes can be tightly repressed and rapidly induced by this ‘conditional knock-out’ approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA constructions

The loxP-kanMX-loxP cassette of pUG6 (5) was PCR-amplified using primers KanMX5 (5′-cagctgaagcttcgtacgc-3′) and KanMX3-SalI (5′-ccaccgtcgacgcataggccactagtggatctg-3′). The fragment was cleaved with SalI and cloned into the XhoI site of the ACT1 intron in pRX1 (6), to yield pRKO. The following primer pairs were used to PCR amplify the 1898 bp intron/kanMX module in pRKO for one-step homology-driven genomic disruptions of URA3 and SIR3: URA3up, 5′-atgtcgaaagctacatataaggaacgtgctgctactcatcctagtcctgtgtatgttctagcgcttgcac-3′, URA3down, 5′-cacacaagtttgtttgcttttcgtgcatgatattaaatagcttggcagcactaaacatataatatagcaacaaaaagaatg-3′; SIR3up, 5′-gttttgttctaacaattggattagctaaaatggctaaaacattggtatgttctagcgcttgcac-3′, SIR3down, 5′-cctgatcatctgtaatgataacttgccaaccgtccaaatctttctaaacatataatatagcaacaaaaagaatg-3′. We have found that 45 bp of flanking homology is not sufficient for targeted integration of PCR products at some locations, including the SIR3 site described here. In such cases, a second round of PCR was performed to add an additional 45 bp of homology to either one or both ends of the integrating fragment.

Plasmids pSH47, pSH62 and pSH63 are single copy GAL-CRE recombinase expression vectors with URA3, HIS3 and TRP1 as selectable markers, respectively (5). Plasmid pSH62-EBD was generated by an in vivo recombination approach (7), using plasmid pSH62 and a fragment containing the estrogen binding domain (EBD). The 314 amino acid EBD (spanning residues 282–595 of the estrogen receptor) was amplified from plasmid pWT251-3 (8) using primers that contained homology to the 3′-end of the Cre recombinase gene: EBD-CREup, 5′-gatagtgaaacaggggcaatggtgcgcctgctggaagatggcgatctcgagccatctgctggagacatgagag-3′ and EBD-CREdown, 5′-cttttgacaggaaacgcaacggatattgagtcaatatcaggcattctactcagactgtggcaggg-3′. pSH62 was linearized with BlpI, which cuts 140 bp downstream of the CRE stop codon. Both the linearized plasmid and PCR fragment were cotransformed into strain THC82 ura3::intron/kanMX and plated on SC-his plates. Transformants were patched onto SC-his-ura plates containing either dextrose, galactose or galactose and 1 µM estradiol (Sigma #E8875, stock solution 1 mM in EtOH). Recombinant plasmids were isolated from patches that grew exclusively on estradiol-containing plates and were confirmed by restriction digestion. pSH62-EBD resembles pSH62 except that the EBD is linked in-frame to the terminal amino acid of Cre by Leu-Glu-Pro, and that 148 bp of untranslated sequence downstream of the CRE gene were removed.

Strain constructions

Strain PJ1 URA3 was derived from W303-1A MATa HMLα HMRa ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3 112 trp1-1 ura3-1 rad5-535 by one-step gene conversion with a PCR-amplified URA3 fragment. The intron/kanMX module was targeted between nucleotides +50 and +51 of the URA3 open reading frame (ORF) in strain PJ1 to yield THC82 ura3::intron/kanMX. Transformants were selected on YPDA plates containing 200 µg/ml G418 (Sigma #G5013) after an initial period of growth (overnight) in non-selective media. Strain THC83 URA3::intron was obtained by transforming THC82 ura3::intron/kanMX with a GAL1-CRE recombinase vector and growing overnight in media containing galactose. The intron/kanMX module was targeted between nucleotides +15 and +16 of the SIR3 ORF in strain THC62 Δmat::TRP1 HMLα Δhmr::rHMLα ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3 112 trp1-1 ura3-1 Δlys2 Δbar1::hisG rad5-535 (9) to yield strain CRC9. All genomic manipulations were confirmed by Southern hybridization.

Preparation of SE media containing G418

For SE drop-in media, 1 g of glutamic acid (monosodium salt, Sigma #G-1626), 1.7 g of yeast nitrogen base lacking both amino acids and ammonium sulfate, 20 g of Bacto agar and the amino acid supplements that were necessary for viable and selective growth of the transformed strains used were added to 900 ml of H2O according to Kaiser et al. (10). Dextrose and filter-sterilized G418 were added after autoclaving to final concentrations of 2% and 200 µg/ml, respectively. SE drop-out media were prepared similarly, using standard recipes for drop-out mixes (10).

Induction protocol for restoration of inactivated genes

Strains containing an integrated intron/kanMX module and a CRE expression vector were pre-grown in appropriate SE drop-in media that contained dextrose and 200 µg/ml G418. At an OD600 of 1–2, the culture was diluted 1/50 into appropriate SC drop-out media containing raffinose and grown for a period spanning four doublings in cell density (~10 h) prior to the addition of galactose (Cf = 2%). Isolation and detection of nucleic acids were performed according to Cheng and Gartenberg (9).

Manipulation and measurement of SIR3 function

Strain CRC9 Δmat::TRP1 HMLα Δhmr::rHMLα sir3::intron/kanMX Δlys2 mates as a MATα strain because α mating-type genes are expressed at both of the derepressed HM loci. If excision of the kanMX cassette from sir3::intron/kanMX restores SIR3 function, the α genes will be silenced at the HM loci and the strain will mate as an a-type cell (Δmat strains mate as a type cells by default). Therefore, the mating capacity of CRC9 was tested with a MATα counterpart strain, W303-1B MATα LYS2. CRC9 was first transformed with pSH47 and grown for induction, as described above. After 2 h in galactose, dextrose was added (Cf = 3%) and cells were plated on SC-ura plates containing dextrose. A control culture was grown similarly though galactose addition was omitted. Individual colonies were patched on YPDA with W303-1B and grown overnight. The patches were replica plated to SC-trp,-lys to test for mating.

RESULTS

The experimental system

We sought a system for controlling gene expression that satisfied the following criteria: (i) tight repression prior to induction; (ii) rapid inducibility; (iii) induction to expression levels that compared to the unmodified gene; and (iv) general applicability. To this end, an engineered intron was used to introduce regulatory sequences into genes of interest. Though relatively few yeast genes contain introns, the approach is generally applicable because the elements have been shown to splice efficiently when placed in heterologous genes (11). Moreover, because all of the information necessary for splicing is contained within the intron, the coding sequence of recipient genes is not altered.

Introns can tolerate sequence insertions as long as the added sequences do not interfere with functional residues (12) or terminate transcription (13). Introns are also constrained by size because splicing efficiency diminishes when intron length exceeds 500 bp (14). Guided by these principles, we developed an intron module that would inhibit expression when placed within a gene but that could be activated conditionally to restore expression. As shown in Figure 1A, the module consisted of the ACT1 gene intron which was modified by insertion of a 1.6 kb kanMX gene cassette flanked by loxP sites (5). Genes interrupted by this module, termed the intron/kanMX module, should not yield full-length pre-mRNA because the kanMX cassette contains an appropriately-oriented transcription terminator (15). Moreover, the intron should be sufficiently large that splicing would not occur in the event that the terminator within the intron is leaky.

Figure 1.

The conditional knock-out approach for controlling gene expression. (A) Methodology. The 5′- and 3′-ends of the ACT1 intron (Int5′ and Int3′, respectively) were separated by a kanMX cassette, which contains the following sequences: the kanamycin resistance gene (kanr), the Ashbya gossypii TEF2 promoter (prom.) and terminator (term.) and tandemly oriented loxP sites. PCR is used to amplify the module and add sequences with genomic homology to the ends. The amplified fragment is used to modify YFG (your favorite gene) by one-step gene disruption (15,16), which results in loss of YFG expression. Inducible site-specific recombination is used to excise the inhibitory kanMX cassette and restore YFG expression. (B) Primer sequences for modifying genes with the intron/kanMX module. The Up and Down primers bind to the 5′-donor and 3′-acceptor sites of the ACT1 intron, respectively. Amplification of plasmid pRKO with these primers yields the self-contained intron/kanMX module with 45 bp of additional sequence on each end (X45 and Y45), which correspond to the integration site within the recipient gene.

The inhibitory action of the intron module can be reversed by Cre recombinase, which utilizes the loxP sites to excise the kanMX cassette (5), as illustrated in Figure 1A. Galactose-induced expression of the recombinase should therefore result in the rapid production of spliceable transcripts, at levels comparable to the unaltered gene.

Validation of the conditional knock-out approach: regulation of URA3

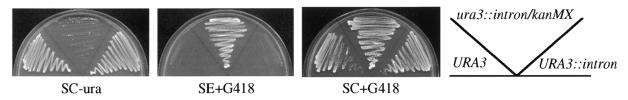

The intron/kanMX module is compact and can therefore be PCR-amplified and targeted to genes of interest using the single-step gene disruption technique (15,16). To test whether the module could inactivate gene expression, it was targeted to the chromosomal URA3 locus. Most yeast introns reside near the 5′-ends of genes and experimental studies have shown that proximity to the 5′-end contributes to optimal splicing efficiency (12,14). Therefore, the intron/kanMX module was inserted between nucleotides +50 and +51 of the URA3 ORF and function of the modified gene was tested by streaking the strain on SC-ura. The first panel of Figure 2 shows that the ura3::intron/kanMX allele did not support growth in the absence of uracil. We conclude that the integrated intron/kanMX module can block expression of a recipient gene.

Figure 2.

Control of URA3 expression by the conditional knock-out approach. Three isogenic strains, PJ1 URA3, THC82 ura3::intron/kanMX and THC83 URA3::intron, were streaked on: panel 1, SC-ura; panel 2, SE+G418 drop-in media containing histidine, leucine, tryptophan, uracil and adenine (SE corresponds to synthetic media containing glutamate as a nitrogen source); panel 3, SC+G418. Rare Cre-independent recombination events between loxP sites (expected at a frequency of 1/104) probably account for the infrequent appearance of ura+ colonies among THC82 cells.

To test whether URA3 inactivation was reversible, the disrupted strain was transformed with a GAL1-CRE expression vector and grown on galactose to induce recombination. This procedure generated the URA3::intron allele, which restored growth in the absence of uracil (Fig. 2, panel 1). Large scale plating assays indicated that galactose-mediated reversion occurred within all plasmid-containing cells (data not shown). Furthermore, restoration of uracil prototrophy was accompanied by loss of G418 resistance, as demonstrated by inhibition of growth on plates containing the antibiotic (Fig. 2, panel 2). Together, these data indicate that inhibition of gene expression by the intron/kanMX module can be reversed by galactose-induced excision of the kanMX cassette.

Synthetic media for G418 selections

Selection for kanMX transformants is typically performed in rich media containing G418. Webster and Dickson (17) noted that kanamycin-resistant cells cannot be selected on minimal media because the high salt content of the media appeared to interfere with sensitivity of wild-type cells to the antibiotic. This observation was recapitulated in the third panel of Figure 2, where strains, irrespective of kanMX genotype, formed colonies on SC+G418 plates. We found that the problematic ingredient was ammonium sulfate, which serves as the primary nitrogen source in standard synthetic media recipes. If media was prepared with monosodium glutamate (1 g/l) instead of ammonium sulfate, G418 selectivity was restored with little effect on growth rate (Fig. 2, panel 2). Other nitrogen sources, such as proline and α-aminoadipate also worked, though growth rates were reduced significantly. Hereafter, we refer to synthetic media based on glutamate as SE media.

Kinetics and magnitude of URA3 activation

Gene activation by the conditional knock-out approach was examined at the DNA and RNA level using a strain that contained the intron/kanMX module at the URA3 locus. The strain was transformed with a TRP1-marked GAL-CRE expression vector and pre-grown in liquid SE+G418 drop-in media containing dextrose but specifically lacking tryptophan. This step was necessary to select for the plasmid and to select against pre-excision events that occur because of low but measurable basal expression of the recombinase (data not shown, 5). Recombination was induced by the addition of galactose (Materials and Methods), and DNA rearrangements were examined by Southern blot analysis. Figure 3A shows that the DNA excision reaction occurred rapidly: ~80% of the integrated intron/kanMX module recombined within 60 min. In addition, the figure shows that the level of pre-excision at time zero was negligible within the limits of detection. These results indicate that rearrangement of the URA3 template occurred rapidly and in a tightly regulated manner.

Figure 3.

Changes in DNA and RNA during URA3 activation. Nucleic acids were harvested from strain THC82 containing pSH63 (lanes 4–7) at timed intervals following the addition of galactose, according to the procedures prescribed in Materials and Methods. (A) Rearrangement of the URA3 gene. Samples were cut with NdeI prior to electrophoresis. Blot was hybridized with a randomly-primed probe corresponding to the ACT1 intron. Band intensities were measured by phosphorimaging. The percentage of recombination (% recombined) was measured by the disappearance of the ura3::intron/kanMX band, which was normalized for loading and reported relative to the value in lane 4. (B) Changes in mature URA3 mRNA levels. Blot was hybridized sequentially with probes to the 5′-UTR of URA3 and the ACT1 ORF. Values were normalized for loading and reported relative to that for the native URA3 gene in lane 1. The plasmid-free strains used as controls in lanes 1–3 were PJ1 URA3, THC82 ura3::intron/kanMX and THC83 URA3::intron, respectively.

Northern blots were used to monitor URA3 transcripts in samples derived from this experiment (Fig. 3B). A control strain that contained the recombined form of the intron reduced the level of mature URA3 mRNA by only 20%, indicating that the intervening sequence was not a significant hindrance to expression (compare lanes 1 and 3). In contrast, the recombined intron/kanMX module eliminated URA3 transcripts completely (lane 2). Induction of the Cre recombinase in this strain resulted in the appearance of mature URA3 transcript at a rate consistent with the DNA rearrangements shown in Figure 3A (see lanes 4–7). Mature URA3 transcript was maximally induced 60 min after galactose addition. At this point the RNA level was within a factor of two of that measured in a strain containing the native URA3 gene (compare lanes 1 and 6). Positioning the intron closer to the 5′-end of the URA3 transcript may have increased splicing efficiency, and thereby increased induced expression of the modified gene further (12,14). Nevertheless, these data demonstrate that regulated recombination of the intron/kanMX module can induce the expression of a modified gene from zero to near-normal levels within a short time frame.

Hormone-dependent control of recombination

As an alternative method for Cre recombinase induction, the CRE gene was fused to the EBD of the human estrogen receptor. Linkage of the EBD to a variety of heterologous proteins has been shown to confer ligand-dependent control of their activity (18). Notably, Cre-EBD chimeras have been used to perform a wide range of ligand-dependent recombination reactions in mammalian cells (19–21). In yeast, the activity of the Flp recombinase was regulated by an analogous fusion construct (8).

We characterized the galactose-driven Cre-EBD expression vector by measuring recombination of the intron/kanMX module at URA3. Figure 4 shows that the EBD greatly reduced Cre-mediated recombination in the absence of ligand. Negligible excision occurred after 2 h growth in galactose (lane 4). Simultaneous addition of galactose and estradiol, however, resulted in >75% excision during the same interval, indicating that in yeast the EBD confers estradiol-dependent control to Cre recombinase (compare lanes 4 and 5). As expected, estradiol treatment resulted in a corresponding increase in the fraction of cells that grew in the absence of uracil (data not shown). A staggered induction protocol was tested in which a 1 h galactose incubation period was followed by a 1 h galactose/estradiol incubation. No recombination occurred after the initial induction of fusion protein expression, whereas 68% of the templates recombined following activation of the fusion protein with estradiol (lanes 6 and 7). This experiment shows that synthesis and activation of the recombinase can be separated temporally. 5

Figure 4.

Inducing DNA rearrangements with a Cre-EBD fusion protein. Strain THC82 ura3::intron/kanMX containing pSH62-EBD (lanes 3–7) was induced with galactose, as described previously. In lane 5, galactose and estradiol (Cf = 1 µM) were added simultaneously for a 2 h interval. In lane 7, galactose was added 1 h prior to the addition of estradiol. Strains THC82 ura3::intron/kanMX and THC83 URA3::intron serve as controls in lanes 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 5.

Patch mating assay for restoration of SIR3 function. Recombination was induced in strain CRC9 sir3::intron/kanMX containing pSH47. Individual colonies from the induction protocol were patch-mated with W303-1B overnight and replica-plated to SC-trp,-lys (Materials and Methods). Left panel, no galactose control. The infrequent instances of mating (2/42 isolates mated and formed patches) probably arose from low-level basal expression of the recombinase. Right panel, exposure to galactose for 2 h (40/42 isolates mated and formed patches). The percentage of mating competent cells was dependent on the length of time in galactose, indicating that restoration of SIR3 expression occurred during (and not after) the galactose induction interval (data not shown).

Regulation of SIR3 by the conditional knock-out approach

To confirm that the conditional knock-out approach was generally applicable, we targeted the intron/kanMX module to the 5′-end of the SIR3 gene. SIR3 is required for silencing of the transcriptionally repressed HM mating-type loci. Cells that lack the gene cannot mate because the silent HM loci are derepressed. A strain containing a sir3::intron/kanMX allele was transformed with a GAL-CRE expression vector, exposed to galactose, and tested for restoration of silencing by using a patch test for mating (Materials and Methods). By virtue of the strains used, diploids acquired the ability to grow without tryptophan and lysine, whereas non-mated haploids did not. Figure 4 shows that few cells containing sir3::intron/kanMX mated (~5%), indicating that the disrupted gene was not functional. In contrast, exposure to galactose for 2 h resulted in restoration of silencing in >95% of the cells tested. These results indicate that SIR3 expression can be regulated by the intron/kanMX module and that the conditional knock-out approach is generally applicable.

DISCUSSION

This paper demonstrates that expression of genes in yeast can be controlled by inducible rearrangement of an engineered intron. The approach offers distinct advantages over more traditional methods of conditional gene activation, such as fusing ORFs to heterologous promoters or isolating temperature sensitive alleles. First, the method imposes tight repression because the regulatory module is placed within the ORFs of modified genes. Prior to activation by recombination, transcription from the endogenous promoter or non-specific sequences nearby cannot produce functional transcript. Though pre-excision may occur in a small population of cells due to basal expression of GAL1-CRE, growth in G418 prior to induction can be used to select against such events. In addition, the Cre-EBD chimera can be used to suppress the activity of basally-expressed recombinase. Because the conditional knock-out approach offers tight repression, it should be particularly useful in situations where a toxic gene must be controlled or when basal expression complicates the ultimate goal of the experiment.

A second advantage of the approach is that reactivated genes are expressed at levels comparable to their unaltered counterparts. Genes that are activated by the conditional knock-out procedure are expressed from their own unaltered promoters and the resulting transcripts appear to splice efficiently (Fig. 3). Additionally, the spliced transcripts are identical to those from unmodified genes because splicing removes the residual sequences of the regulatory module. Consequently, translation, folding and localization of activated gene products are not affected by this induction method. Temperature-sensitive alleles, by contrast, must always possess mutations, usually within the coding sequence, even at permissive temperatures.

A third advantage of the conditional knock-out approach is that inactivated genes can be rapidly reactivated. In this system, the promoters of regulated genes are already assembled in a transcriptionally-active state. Inhibition of expression occurs at a later step, either during transcriptional elongation or RNA processing. Restoration of gene activity appears to be limited largely by the rate of Cre-mediated DNA excision, which occurs rapidly in yeast, as shown in Figure 3. Unlike transcriptional fusions and temperature-sensitive alleles, however, the approach is limited by the fact that once activated, recombined genes cannot be turned back off. In applications where transient expression is desired, the more traditional forms of gene control are better suited.

The development of a Cre-EBD expression vector for yeast makes more elaborate induction protocols possible, such as the sequential induction of two genes. In this case, expression of the first gene (along with inactive Cre-EBD) can be driven by a galactose-regulated promoter, whereas expression of the second gene can be regulated by estradiol, GAL1::CRE-EBD and the intron/kanMX module. The hormone regulated recombinase will be useful in situations where galactose inductions must be avoided.

A fourth advantage of the conditional knock-out approach is that it is easy to use and generally applicable. The procedure requires only simple laboratory procedures, cheap and easily obtained chemicals, a recombinase expression vector and a pair of gene-specific PCR primers. Though URA3 and SIR3 serve as proofs of principle, it is likely that other (perhaps all) non-essential genes could be controlled similarly. The approach could also be used to activate expression of dominant negative alleles or to express epitope-tagged alleles of proteins at particular stages of the cell cycle or during developmental processes. Programmed DNA rearrangements, like those described here, have been used to activate gene expression in mammalian cells (21). In these cases, genes were inactivated by placing a piece of inhibitory yet excisable ‘stuffer DNA’ directly within the ORF (22) or within the 5′-UTR (23–25).

In this paper, we also show that selection for G418 resistance is possible in minimal media containing glutamate as the primary nitrogen source. While it is not yet clear why glutamate works and ammonium sulfate does not, the answer may lie in the complex regulatory network that governs nitrogen utilization (26). Yeast cells sense the available nitrogen sources in media and up-regulate factors necessary for utilization of the optimal nitrogen-containing compound and down-regulate pathways required for utilization of others. Conceivably, growth on ammonia sufficiently down-regulates a pathway necessary for import or activity of G418. Irrespective of the mechanism, the use of glutamate as a nitrogen source expands the utility of the popular kanMX cassette because it can now be used as a coselectable marker in procedures that require more than one selectable gene, such as yeast crosses, cotransformations and comaintenance of multiple plasmids or unstable genetic loci.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Abram Gabriel and Steve Brill for valuable consultation and Steve Brill, as well as contributors to the bionet.molbio.yeast newsgroup, for suggestions on G418 selection in minimal media. We thank Abram Gabriel, Francis Stewart, Johannes Hegemann and Steve Brill for kindly providing plasmids. This work was funded by a grant from the NIH (GM51402).

REFERENCES

- 1.Botstein D., Chervitz,S.A. and Cherry,J.M. (1997) Yeast as a model organism. Science, 277, 1259–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mumberg D., Müller,R. and Funk,M. (1995) Yeast vectors for the controlled expression of heterologous proteins in different genetic backgrounds. Gene, 156, 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rönicke V., Graulich,W., Mumberg,D., Müller,R. and Funk,M. (1997) Use of conditional promoters for expression of heterologous proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol., 283, 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labbé S. and Thiele,D.J. (1999) Copper ion inducible and repressible promoter systems in yeast. Methods Enzymol., 306, 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Güldener U., Heck,S., Fiedler,T., Beinhauer,J. and Hegemann,J.H. (1996) New efficient gene disruption cassette for repeated use in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 2519–2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu X. and Gabriel,A. (1999) Patching broken chromosomes with extranuclear cellular DNA. Mol. Cell, 4, 873–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oldenburg K.R., Vo,K.T., Michaelis,S. and Paddon,C. (1997) Recombination-mediated PCR-directed plasmid construction in vivo in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 451–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nichols M., Rientjes,J.M., Logie,C. and Stewart,A.F. (1997) Flp recombinase/estrogen receptor fusion proteins require the receptor D domain for responsiveness to antagonists, but not agonists. Mol. Endocrinol., 11, 950–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng T.-H. and Gartenberg,M.R. (2000) Yeast heterochromatin is a dynamic structure that requires silencers continuously. Genes Dev., 14, 452–463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser C., Michaelis,S. and Mitchell,A. (1994) Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 11.Rymond B.C. and Rosbash,M. (1992) In Broach,J.R., Jones,E.W. and Pringle,J.R. (eds), The Molecular and Cellular Biology of Yeast Saccharomyces: Gene Expression. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, Vol. 2, pp. 143–192.

- 12.Yoshimatsu T. and Nagawa,F. (1994) Effect of artificially inserted intron on gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Cell Biol., 13, 51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doheny K.F., Sorger,P.K., Hyman,A.A., Tugendreich,S., Spencer,F. and Hieter,P. (1993) Identification of essential components of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae kinetochore. Cell, 73, 761–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klinz F.J. and Gallwitz,D. (1985) Size and position of intervening sequences are critical for the splicing efficiency of pre-mRNA in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res., 13, 3791–3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wach A., Brachat,A., Pöhlmann,R. and Philippsen,P. (1994) New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast, 10, 1793–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baudin A., Ozier-Kalogeropoulos,O., Denouel,A., Lacroute,F. and Cullin,C. (1993) A simple and efficient method for direct gene deletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 3329–3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webster T.D. and Dickson,R.C. (1983) Direct selection of Saccharomyces cerevisiae resistant to the antibiotic G418 following transformation with a DNA vector carrying the kanamycin-restistance gene Tn903. Gene, 26, 243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Picard D. (1994) Regulation of protein function through expression of chimaeric proteins. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., 5, 511–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Logie C. and Stewart,A.F. (1995) Ligand-regulated site-specific recombination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 5940–5944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Metzger D., Clifford,J., Chiba,H. and Chambon,P. (1995) Conditional site-specific recombination in mammalian cells using a ligand-dependent chimeric Cre recombinase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 6991–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metzger D. and Feil,R. (1999) Engineering the mouse genome by site-specific recombination. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., 10, 470–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Gorman S., Fox,D.T. and Wahl,G.M. (1991) Recombinase-mediated gene activation and site-specific integration in mammalian cells. Science, 251, 1351–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sauer B. and Henderson,N. (1989) Cre-stimulated recombination at loxP-containing DNA sequences placed into the mammalian genome. Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 147–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanegae Y., Lee,G., Sato,Y., Tanaka,M., Nakai,M., Sakaki,T., Sugano,S. and Saito,I. (1995) Efficient gene activation in mammalian cells by using recombinant adenovirus expressing site-specific Cre recombinase. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 3816–3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angrand P.-O., Woodroofe,C.P., Buchholz,F. and Stewart,A.F. (1998) Inducible expression based on regulated recombination: a single vector for stable expression in cultured cells. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 3263–3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magasanik B. (1992) In Broach,J.R., Jones,E.W. and Pringle,J.R. (eds), The Molecular and Cellular Biology of Yeast Saccharomyces: Gene Expression. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, Vol. 2, pp. 283–317.