Abstract

Abstract

Tyramine has attracted considerable interest due to recent findings that it is an excellent starting material for the production of high-performance thermoplastics and hydrogels. Furthermore, tyramine is a precursor of a diversity of pharmaceutically relevant compounds, contributing to its growing importance. Given the limitations of chemical synthesis, including lack of selectivity and laborious processes with harsh conditions, the biosynthesis of tyramine by decarboxylation of l-tyrosine represents a promising sustainable alternative. In this study, the de novo production of tyramine from simple nitrogen and sustainable carbon sources was successfully established by metabolic engineering of the l-tyrosine overproducing Corynebacterium glutamicum strain AROM3. A phylogenetic analysis of aromatic-l-amino acid decarboxylases (AADCs) revealed potential candidate enzymes for the decarboxylation of tyramine. The heterologous overexpression of the respective AADC genes resulted in successful tyramine production, with the highest tyramine titer of 1.9 g L−1 obtained for AROM3 overexpressing the tyrosine decarboxylase gene of Levilactobacillus brevis. Further metabolic engineering of this tyramine-producing strain enabled tyramine production from the alternative carbon sources ribose and xylose. Additionally, up-scaling of tyramine production from xylose to a 1.5 L bioreactor batch fermentation was demonstrated to be stable, highlighting the potential for sustainable tyramine production.

Key points

• Phylogenetic analysis revealed candidate l-tyrosine decarboxylases

• C. glutamicum was engineered for de novo production of tyramine

• Tyramine production from alternative carbon substrates was enabled

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00253-024-13319-8.

Keywords: Corynebacterium glutamicum, Tyramine, Aromatic amino acid decarboxylase, Sustainable amine production, Plant alkaloids, Pharmaceutical drug precursor

Introduction

Tyramine is a primary amine that can be found in bacteria, plants, and animals. Recently, there has been a notable increase in interest across various industries with regard to its diverse applications. In addition to its use as a monomer for the production of high-performance thermoplastics (Chen et al. 2023), tyramine has been shown to improve the wettability and formation of stable cell–matrix interactions of alginate-based hydrogels, rendering them promising biomaterials for tissue engineering (Schulz et al. 2019). Moreover, tyramine serves as a precursor to a variety of compounds that hold potential for use in pharmaceutical and industrial applications. For instance, tyrosol that can be derived from tyramine has anti-inflammatory effects (Giovannini et al. 2002) and is itself a precursor for several health-promoting compounds, including β-blockers and the neuroprotective salidroside (Ippolito and Vigmond 1988; Yu et al. 2011; Torrens-Spence et al. 2018). Furthermore, N-acetyltyramine has been demonstrated to exhibit activity against multidrug-resistant pathogens and is a putative new antiplatelet drug due to its inhibitory effect on factor Xa (Lee et al. 2017; Driche et al. 2022). Dopamine, another attractive derivative of tyramine, is a neurotransmitter. Furthermore, it forms polydopamines, which have applications in biotechnology for reversible binding of enzymes and other biomolecules. Additionally, polydopamines have been demonstrated to delay fouling when applied as coatings to membranes used for water purification (Lee et al. 2009; McCloskey et al. 2010).

The chemical synthesis of primary amines can be achieved through the catalytic hydrogenation of nitriles. However, a lack of selectivity towards the desired amine often results in the formation of secondary or tertiary amines, as well as other undesired side products. Moreover, chemical tyramine synthesis is laborious, comprising multiple synthesis steps, and requires harsh conditions rendering it environmentally unfavorable (Hegedűs and Máthé 2005; McAllister et al. 2018). Conversely, the biotechnological production of tyramine from l-tyrosine can be achieved under mild conditions by selective pyridoxal-5′phosphate dependent decarboxylation of aromatic l-amino acids by AADCs (EC 4.1.1.28; Li et al. 2012). Therefore, whole-cell biotransformation utilizing AADCs for tyramine production represents a desirable alternative to chemical synthesis, as the enzymatic decarboxylation of l-tyrosine occurs at ambient pH and temperature. Furthermore, biotransformation allows for a high degree of selectivity, thereby offering more cost-efficient production processes compared to the chemical synthesis (Lin and Tao 2017; Sheldon and Woodley 2018). However, whole-cell biotransformation necessitates an external supply of l-tyrosine and its efficient import into the cells (Zhu et al. 2020). To circumvent this limitation, de novo biosynthesis of tyramine from simple nitrogen and carbon sources can be employed. In bacteria, l-tyrosine is synthesized via the shikimate pathway (Chávez-Béjar et al. 2012). Metabolic engineering can extend the biosynthesis of l-tyrosine by its subsequent decarboxylation, thus, enabling the de novo production of tyramine from simple starting materials such as ammonia and glucose or more sustainable carbon sources such as xylose or arabinose, which are prevalent in lignocellulosic agricultural waste products (Aristidou and Penttilä 2000).

Corynebacterium glutamicum is an optimal host for metabolic engineering aimed at tyramine production since it is a well-established workhorse in the industry, utilized for the production of millions of tons of amino acids per year (Wendisch 2020). It exhibits the capacity to utilize a diverse range of carbon sources, encompassing various sugars, such as glucose, fructose, maltose, sucrose, and ribose (Blombach and Seibold 2010), as well as organic acids, including acetate and lactate (Gerstmeir et al. 2003; Stansen et al. 2005). Furthermore, it has been engineered to utilize various alternative carbon sources, including arabinose (Kawaguchi et al. 2008; Schneider et al. 2011), xylose (Gopinath et al. 2011; Meiswinkel et al. 2013), and glycerol (Rittmann et al. 2008). C. glutamicum has been genetically engineered for the production of high-value active ingredients for food, feed, human well-being and health (Wolf et al. 2021). For example, various aromatic compounds, including l-phenylalanine (Zhang et al. 2015), l-tryptophan (Bampidis et al. 2019), N-methylphenylalanine (Kerbs et al. 2021), halogenated tryptophan derivatives (Veldmann et al. 2019), indole (Mindt et al. 2022), and protocatechuic acid (Okai et al. 2016) can be obtained in fermentative processes using engineered C. glutamicum strains.

In this study, the l-tyrosine synthesis pathway in C. glutamicum was extended by l-tyrosine decarboxylation to enable de novo biosynthesis of tyramine. Previously, metabolic engineering has resulted in the l-tyrosine overproducing strain AROM3, achieving an l-tyrosine titer of 3.1 g L−1 (Kurpejović et al. 2023). Moreover, the heterologous overexpression of AADC genes from Bacillus atrophaeus, Clostridium sporogenes, and Ruminococcus gnavus in an l-tryptophan overproducing C. glutamicum strain enabled the de novo production of tryptamine (Kerbs et al. 2022). To identify potential AADCs active with l-tyrosine, a phylogenetic analysis was conducted and four candidate AADC genes were selected and overexpressed in the l-tyrosine overproducing strain AROM3 to facilitate tyramine production (Fig. 1). Finally, the substrate spectrum of the optimal tyramine-producing strain was expanded to encompass alternative carbon sources, thereby facilitating sustainable tyramine production.

Fig. 1.

Scheme of metabolic engineering of C. glutamicum AROM3 for tyramine production. Continuous arrows indicate single reaction steps, while dashed arrows indicate multiple reaction steps. Genetic modifications of AROM3 are depicted by colored enzyme names, whereby a blue arrow up indicates overexpression, red arrows down indicate reduced expression by start codon exchange from ATG to TTG, and an arrow marked with a red cross indicates gene deletion. Overexpression of genes for tyramine production from alternative carbon sources are represented by green enzyme names and arrows pointing up. AADCXx: aromatic-l-amino acid decarboxylase from different organisms, AroF and AroG: DAHP synthase, AroGEcfbr: feedback-resistant DAHP synthase from E. coli, Csm: chorismate mutase, DapC: N-succinyl-aminoketopimelate aminotransferase, DAHP: 3-deoxy-d-arabinoheptulosonate-7-phosphate, E4P: erythrose 4-phosphate; LdhA: lactate dehydrogenase, NAD(P): nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate), PEP: phosphoenolpyruvate, PheA: prephenate dehydratase, PPP: pentose phosphate pathway, TrpE: anthranilate synthase, TyrA: arogenate dehydrogenase, XylA: xylose isomerase, XylB: xylulose kinase

Material and methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli and C. glutamicum were cultivated at 37 °C and 180 rpm or at 30 °C and 120 rpm, respectively, in lysogeny broth (LB, Bertani 1951) medium or brain–heart infusion (BHI) medium supplemented with 91 g L−1 sorbitol. When appropriate, the medium was supplemented with kanamycin 25 µg mL−1 and tetracycline 5 µg mL−1.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain | Relevant characteristics | Antibiotic resistance | Supplements | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | supE44ΔlacU169 (Φ80dlacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyr96 thi-1 relA1 | - | - | Hanahan (1983) |

| AROM3 | C1* ΔldhA Δvdh::PilvC-aroGEcD146N trpEM1L pheAM1L | - | l-Phenylalanine | Kurpejović et al. (2023) |

| AROM3 EV | AROM3 harboring pECXT99A | TetR | l-Phenylalanine, IPTG | This study |

| AROM3 aaDCBa | AROM3 harboring pECXT-Psyn-aaDCBa | TetR | l-Phenylalanine | This study |

| AROM3 aaDCCs | AROM3 harboring pECXT-Psyn-aaDCCs | TetR | l-Phenylalanine | This study |

| AROM3 aaDCRg | AROM3 harboring pECXT-Psyn-aaDCRg | TetR | l-Phenylalanine | This study |

| AROM3 tdcLb | AROM3 harboring pECXT99A-tdcLb | TetR | l-Phenylalanine, IPTG | This study |

| AROM3 tdcLb xylAXcBCg | AROM3 harboring pECXT99A-tdcLb and pVWEx1-xylAXc-xylBCg | TetR, KanR | l-Phenylalanine, IPTG | This study |

| Plasmid | ||||

| pECXT99A | C. glutamicum/E. coli shuttle vector for inducible overexpression, Ptrc, lacIq, pGA1 mini oriVCg, pMB1 oriVEc | TetR | IPTG | Kirchner and Tauch (2003) |

| pECXT-Psyn-aaDCBa | pECXT-Psyn derivative for overexpression of codon-harmonized aaDC from B. atrophaeus with an optimized RBS | TetR | - | Kerbs et al. (2022) |

| pECXT-Psyn-aaDCCs | pECXT-Psyn derivative for overexpression of codon-harmonized aaDC from C. sporogenes with an optimized RBS | TetR | - | Kerbs et al. (2022) |

| pECXT-Psyn-aaDCRg | pECXT-Psyn derivative for overexpression of codon-harmonized aaDC from R. gnavus with an optimized RBS | TetR | - | Kerbs et al. (2022) |

| pECXT99A-tdcLb | pECXT99A derivative for overexpression of codon-harmonized tdc from L. brevis with an optimized RBS | TetR | IPTG | This study |

| pVWEx1-xylAXcBCg | Derivative from pVWEx1 for inducible overexpression of xylA from Xanthomonas campestris and xylB from C. glutamicum | KanR | IPTG | Meiswinkel et al. (2013) |

Growth and production experiments with C. glutamicum strains were performed under selective conditions in 100 mL baffled shake flasks with 10 mL CGXII minimal medium (Eggeling and Bott 2005) containing 40 g L−1 glucose as carbon source, if not mentioned otherwise, and supplemented with 0.5 mM l-phenylalanine (Kurpejović et al. 2023). The CGXII minimal medium was inoculated to an initial optical density at a wavelength of 600 nm (OD600) of 1 and growth was monitored for 72 h by measurement of the OD600 using a V-1200 spectrophotometer (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA). OD600 was converted to g L−1 cell dry weight (CDW) by multiplication with the experimentally determined conversion factor 0.353. Gene expression of the plasmids pECXT99A and pVWEx1 and their derivatives was induced by addition of 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). To assess possible toxic effects of tyramine, C. glutamicum AROM3 was cultivated in CGXII minimal medium containing tyramine at different concentrations.

Molecular genetic techniques and strain construction

All primers used for DNA amplification and sequencing (Supplementary Table S1) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Ulm, Germany). Plasmid isolation and DNA purification were performed using the GeneJET Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Schwerte, Germany) and the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up Kit (Macherey–Nagel GmbH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentrations were measured using the NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 260 nm.

The tdc gene from L. brevis (Genbank: JX204286) was codon-harmonized for C. glutamicum (Haupka 2020, Supplementary Table S2) and constructed by gene synthesis by Twist Bioscience (South San Francisco, CA, USA). Using an Allin™ HiFi DNA Polymerase (highQu GmbH, Kraichtal, Germany), the tdcLb was amplified with the primers tdc_pECXT99A_fw and tdc_pECXT99A_rv adding pECXT99A overhangs as well as an optimized ribosome binding site (RBS) calculated using the Salislab software (Reis and Salis 2020, Supplementary Table S2). The amplified gene was cloned into the EcoRI linearized pECXT99A-plasmid (New England Biolabs, Frankfurt, Germany) via Gibson assembly (Gibson et al. 2009). Chemocompetent E. coli DH5α were prepared by the CaCl2 method and transformed with the pECXT99A-tdcLb by performing a heat shock at 42 °C (Sambrook and Russel 2001). The correct sequence of the constructed plasmid was verified by sequencing using the appropriate oligonucleotides (Supplementary Table S1).

For the construction of tyramine producing C. glutamicum strains, electrocompetent C. glutamicum AROM3 cells were prepared and transformed by electroporation followed by a heat shock at 46 °C with the plasmids for the overexpression of the AADC genes (Eggeling and Bott 2005).

Quantification of aromatic compounds and carbohydrates by HPLC analysis

Extracellular glucose, xylose, and ribose as well as l-phenylalanine, l-tyrosine, and l-tryptophan, and their corresponding amines were quantified using the Agilent 1200 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies Deutschland GmbH, Waldbronn, Germany). Cell culture samples were vortexed vigorously, diluted to the linear range of the corresponding detector, and centrifuged at 20,238 × g and room temperature for 10 min. The supernatant was subjected to HPLC analysis and the resulting data was evaluated with OpenLab CDS (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA).

For the quantification of the aromatic amino acids and amines, 100 μM cadaverine was added as an internal standard to each sample, and an automatic pre-column derivatization with o-phthalaldehyde was performed (Jones and Gilligan 1983). 5 µL sample was injected into a reversed-phase system consisting of a 40 × 4 mm LiChrospher 100 RP18 EC-5 μm pre-column (CS-Chromatographie Service GmbH, Langerwehe, Germany) and a 125 × 4 mm LiChrospher 100 RP18 EC-5 μm (CS-Chromatographie Service GmbH, Langerwehe, Germany) main column. As mobile phase, 0.25% (v/v) sodium acetate, pH 6.0 (solvent A), and methanol (solvent B) were used applying the gradient and flow rates stated in Supplementary Table S3. Detection was carried out with a fluorescence detector (FLD G1321A, 1200 series, Agilent Technologies) with excitation and emission wavelength of 230 nm and 450 nm, respectively.

Carbohydrates were analyzed on a system consisting of a 40 × 8 mm organic acid resin pre-column and a 300 × 8 mm organic acid resin main column with 10 μm particle size (CS-Chromatographie Service GmbH, Langerwehe, Germany). 5 μL sample was injected into the system, and separation was performed at a column temperature of 60 °C using 5 mM sulfuric acid as mobile phase at a constant flow rate of 0.8 mL min−1 for 17 min. Detection was performed using a refractive index detector (RID Detector G1362A, Agilent Technologies Deutschland GmbH, Waldbronn, Germany). Pure substances were purchased as standards for identification and quantification.

Bioreactor batch-mode cultivation

Batch fermentations were conducted in glass bioreactors with a total volume of 3.7 L and a stirrer/reactor diameter ratio of 0.39 (KLF, Bioengineering AG, Wald, Switzerland). Two six-bladed Rushton turbines were positioned on the stirrer axis at heights of 6 cm and 12 cm, accompanied by a mechanical foam breaker at 22 cm.

First precultures of AROM3 tdcLb and AROM3 tdcLb xylAXcBCg were cultivated as described above under selective conditions in 50 mL LB medium containing 10 g L−1 glucose or xylose, respectively, for 8 h. Second precultures were performed in 200 mL CGXII minimal medium supplemented with 40 g L−1 glucose or xylose, 1 mM l-phenylalanine, 1 mM l-tryptophan, and respective antibiotics. They were inoculated with the first precultures to an OD600 of 1 or 3, respectively, and cultivated overnight. For batch fermentations, 1.5 L of CGXII minimal medium without MOPS, containing the same supplements as the second precultures, was inoculated to an initial OD600 of 1.

Throughout fermentation, the temperature was kept constant at 30 °C and a steady air flow of 0.3 NL min−1 was sustained with a ring sparger. The stirrer speed was automatically adjusted between 400 and 1500 rpm to maintain the relative dissolved oxygen saturation (rDOS) at 30%. The pH was kept constant at 7.0 ± 0.1 by the automatic addition of 10% (v/v) H3PO4 or 25% (v/v) NH3. Foaming was reduced by the addition of antifoam 204 controlled by an antifoam probe. Samples were taken using an autosampler and stored at 4 °C until analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis of aromatic amino acid decarboxylases

The amino acid sequence of the TdcLb was subjected to a PSI-BLAST search (Altschul et al. 1997) against the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database (The UniProt Consortium 2021) using the BLOSUM62 matrix and an e-value cut-off of 0.001. The resulting list of proteins with high sequence similarity was then aligned with Clustal Omega using the default iteration settings (Sievers et al. 2011). With these alignments, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-tree v1.6.12 (Trifinopoulos et al. 2016). The parameters used were “-bb 1000 -alrt 1000”. The enzyme groups were labeled and the phylogenetic tree was visualized using Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6.9 (Letunic and Bork 2021).

Results

Assessing the suitability of C. glutamicum for tyramine production

Several bacteria, including coryneform bacteria, have been reported to possess the ability to degrade tyramine through the utilization of amine oxidases (Leuschner et al. 1998). To determine whether tyramine is degraded by C. glutamicum and, at the same time, to evaluate the influence of tyramine on its growth, C. glutamicum AROM3 was grown in CGXII minimal medium with 40 g L−1 glucose as sole carbon source in the presence of 0–50 mM tyramine for 48 h. Samples were taken from the cultures containing 10 mM tyramine at the beginning and the end of cultivation, and tyramine concentrations were determined via HPLC measurement.

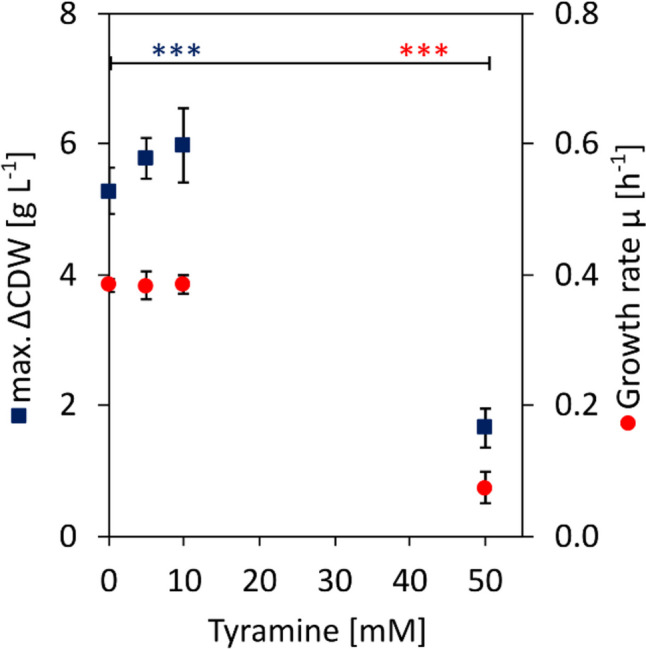

The concentration of tyramine did not decrease within 48 h of cultivation (Supplementary Fig. S1), indicating that AROM3 does not degrade tyramine. Exposure to tyramine concentrations up to 10 mM had no significant effect on the growth of AROM3 in glucose containing minimal medium (Fig. 2). However, in the presence of 50 mM tyramine, the growth rate was significantly reduced and a maximum ΔCDW of only about 30% was reached compared to the culture without tyramine supplementation. These results indicated that high concentrations of tyramine inhibit the growth of AROM3. In summary, the robustness of AROM3 to tyramine concentrations of up to 10 mM and the fact that this strain does not degrade tyramine renders it a suitable candidate for metabolic engineering aimed at the large-scale production of tyramine.

Fig. 2.

Influence of tyramine on the growth of C. glutamicum AROM3. Maximum ΔCDW (dark blue squares) and specific growth rate (red circles) of AROM3 cultivated in 10 mL CGXII minimal medium supplemented with 40 g L−1 glucose, 0.5 mM l-phenylalanine, and 0–50 mM tyramine for 48 h. Values and error bars represent means and standard deviations of triplicate cultivations. Significance was calculated with a two-sided Student’s t-test with ***: p < 0.001. No significant differences in the growth behavior were obtained between cultivations with 0, 5, and 10 mM tyramine

Phylogenetic analysis of decarboxylases

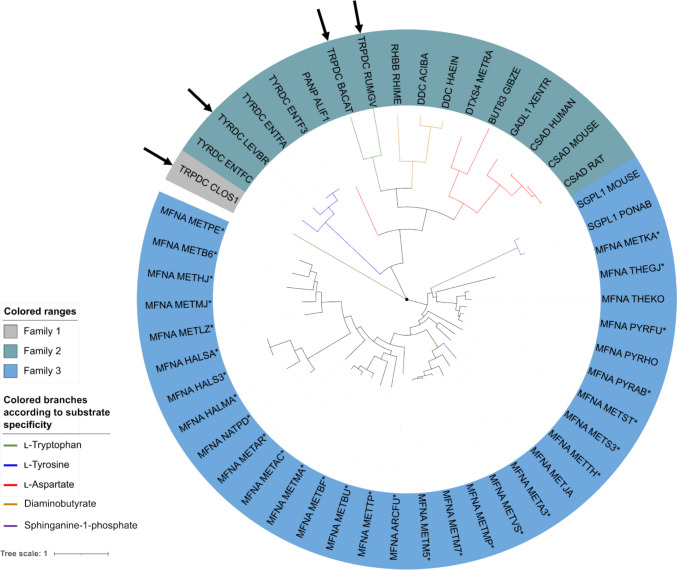

Tyramine arises from l-tyrosine by decarboxylation. However, C. glutamicum is not known to secrete tyramine and inspection of its genome did not indicate candidate genes encoding l-tyrosine decarboxylases. Similarly, l-tryptophan decarboxylases are absent from the C. glutamicum genome and de novo tryptamine production was only achieved via introduction of heterologous aromatic-l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADCs, EC 4.1.1.28) genes from one of the three microorganisms Bacillus atrophaeus, Clostridium sporogenes, or Ruminococcus gnavus in an l-tryptophan overproducing C. glutamicum strain (Kerbs et al. 2022). Since these three AADCs accept all three aromatic proteinogenic amino acids as substrates (Williams et al. 2014; Choi et al. 2021), their utilization for tyramine production was an obvious choice. However, these enzymes prefer l-tryptophan over l-tyrosine as substrate. Thus, a phylogenetic analysis was conducted to find related enzyme candidates that might be more specific for l-tyrosine. The phylogenetic analysis depicted in Fig. 3 revealed that the homologous proteins identified by PSI-BLAST can be classified into three major families. Family 1 is unique in that it contains only the AADC from C. sporogenes (Williams et al. 2014). By contrast, family 2 contains a diversity of well-annotated decarboxylases, including the two AADCs from B. atrophaeus and R. gnavus. Therefore, we focused on this family of enzymes to find alternative AADCs for tyramine production. Each branch of family 2 consists of decarboxylases with the same substrate specificity. One of these branches, colored in blue, comprises l-tyrosine decarboxylases (Tdcs, EC 4.1.1.25) from Enterococcus faecalis and Levilactobacillus brevis. The Tdcs from E. faecalis exhibit high activity for l-tyrosine, but can also accept l-phenylalanine as a substrate (Liu et al. 2014). In contrast, the Tdc from L. brevis (TdcLb) is specific for l-tyrosine and does not decarboxylate l-tryptophan or l-phenylalanine (Moreno-Arribas and Lonvaud-Funel 2001). In addition, TdcLb is reported to have a lower Km value for l-tyrosine and an approximately 30-fold higher Vmax value compared to E. faecalis Tdcs (Zhang and Ni 2014; Liu et al. 2014). Family 3 includes an l-tyrosine decarboxylase from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii (MFNA METJA). However, since this bacterium is thermophilic and its decarboxylase exhibits activity at 70 °C (Kezmarsky et al. 2005), it is not a suitable candidate for in vivo tyramine production in C. glutamicum, which is cultivated at its temperature optimum of 30 °C. Besides this enzyme, family 3 consists mostly of enzymes that have not yet been characterized and are therefore annotated as putative l-tyrosine/l-aspartate decarboxylases based on sequence similarity, many of which also originate from thermophiles.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of amino acid decarboxylases divided into three major families. Enzymes are labeled with their annotation and organism as listed in Supplementary Table S4. Branches of characterized decarboxylases were colored according to their substrate specificity. Putative l-tyrosine/l-aspartate decarboxylases are marked with an asterisk. AADCs chosen as candidates for the production of tyramine in AROM3 are highlighted by arrows

Taken together, besides the AADCs from C. Sporogenes, B. atrophaeus, and R. gnavus, we chose the Tdc from L. brevis as a promising enzyme for tyramine production in AROM3.

Testing of AADCs for fermentative tyramine production

To conduct a comparative analysis of tyramine production, the candidate decarboxylase gene tdcLb and the three AADC genes aaDCBa, aaDCCs, and aaDCRg previously used for tryptamine production (Kerbs et al. 2022) were overexpressed in the l-tyrosine producing strain AROM3. For this, pECXT-plasmid derivatives carrying either one of the four decarboxylase genes codon-harmonized for C. glutamicum or no insert as a negative control were used to transform the strain AROM3. The resulting strains were named AROM3 tdcLb, AROM3 aaDCBa, AROM3 aaDCCs, AROM3 aaDCRg, and AROM3 EV and were cultivated in glucose containing minimal medium for 72 h.

Tyramine production was observed for all strains expressing the different decarboxylase genes (Fig. 4), while the empty vector carrying strain produced l-tyrosine (1.7 g L−1), but no tyramine. By contrast, the strains AROM3 aaDCBa, AROM3 aaDCCs, and AROM3 aaDCRg, produced tryptamine and 2-phenethylamine (2-PEA) in concentrations up to 0.1 g L−1. Notably, neither of these two amines was detected in the AROM3 tdcLb culture supernatants.

Fig. 4.

Production of l-tyrosine (light blue), 2-phenethylamine (red), tryptamine (green), and tyramine (dark blue) by C. glutamicum AROM3 strains overexpressing different decarboxylase genes. AROM3 strains carrying the plasmids pECXT99A, pECXT99A-tdcLb, or pECXT-Psyn-aaDCRg/Ba/Cs were grown in CGXII minimal medium containing 40 g L−1 glucose and 0.5 mM l-phenylalanine. AROM3 EV and AROM3 tdcLb were induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG at the start of cultivation. For each strain, the mean concentrations of l-tyrosine, tyramine, tryptamine, and 2-phenethylamine (PEA) measured in the culture supernatants are represented by the corresponding area in a pie chart. The total area of each pie correlates with the sum of these measured compounds. Neither l-phenylalanine nor l-tryptophan was detected in any of the culture supernatants (detection limit: 0.1 mM)

The highest tyramine titer of 1.9 ± 0.1 g L−1 was achieved with AROM3 tdcLb, followed by AROM3 aaDCRg (1.3 ± 0.1 g L−1), AROM3 aaDCBa (0.8 ± 0.1 g L−1), and AROM3 aaDCCs (0.2 ± 0.1 g L−1). Notably, AROM3 tdcLb accumulated 1.9 ± 0.1 g L−1 tyramine (and 0.1 ± 0.1 g L−1 l-tyrosine), which compared to the l-tyrosine production of AROM3 EV (1.7 ± 0.1 g L−1) was about 12% higher by weight, which is equivalent to an increase by approximately 43 mol-%. Thus, tyramine production by AROM3 tdcLb benefitted from a metabolic pull caused by the efficient decarboxylation of l-tyrosine to tyramine catalyzed by TdcLb. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of fermentative de novo production of tyramine by C. glutamicum.

Tyramine production from alternative carbon sources

The increasing demand for the use of alternative sustainable feedstocks in biotechnological processes prompted us to test if the successful glucose-based de novo production of tyramine by AROM3 tdcLb could be transferred to tyramine production based on the pentose sugars ribose or xylose. While C. glutamicum is naturally able to grow with ribose, it cannot utilize xylose as a carbon source. Previously, the combined overexpression of the xylose isomerase gene from Xanthomonas campestris (xylAXc) and the endogenous xylulose kinase gene xylBCg enabled efficient growth and amino acid production by C. glutamicum from xylose (Meiswinkel et al. 2013). Thus, AROM3 tdcLb was transformed with pVWEx1-xylAXc-xylBCg, resulting in the strain AROM3 tdcLb xylAXcBCg. The parental strain AROM3 tdcLb and the xylose utilizing strain AROM3 tdcLb xylAXcBCg were cultivated in CGXII minimal medium containing 40 g L−1 ribose or xylose, respectively, for 72 h. The tyramine production on these carbon sources was compared with a control grown on glucose. AROM3 tdcLb showed comparable growth on glucose and ribose (Supplementary Fig. S2). After 72 h of cultivation, only minor amounts of ribose remained (0.2 ± 0.1 g L−1), and the tyramine production on ribose did not differ significantly from that on glucose. Both conditions resulted in similar titers, volumetric productivities, and product yield coefficients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Tyramine titers, volumetric productivities, and product per substrate yield coefficients (YPS) of AROM3 tdcLb and AROM3 tdcLb xylAXcBCg on different carbon sources. The strains were cultivated in CGXII minimal medium containing 40 g L−1 glucose, ribose, or xylose as a carbon source as well as 0.5 mM l-phenylalanine for 72 h. Values represent means and standard deviations of triplicate cultivations

| Strain | Carbon source | Tyramine titer [g L−1] |

Volumetric productivity [g L−1 h−1] |

YPS [g g−1 carbon source] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AROM3 tdcLb | Glucose | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 0.022 ± 0.001 | 0.040 ± 0.003 |

| AROM3 tdcLb | Ribose | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 0.019 ± 0.001 | 0.034 ± 0.003 |

| AROM3 tdcLb xylAXcBCg | Xylose | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 0.037 ± 0.001 |

The growth of AROM3 tdcLb xylAXcBCg with xylose showed a longer lag phase compared to AROM3 tdcLb cultivated with glucose (4.3 ± 0.9 h compared to 1.2 ± 0.7 h) and the growth rate was more than halved, from 0.26 ± 0.04 h−1 to 0.11 ± 0.01 h−1 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Nevertheless, both the tyramine titer and the volumetric productivity after 72 h of cultivation with xylose were comparable to those of AROM3 tdcLb grown with ribose (Table 2). At the end of cultivation, approximately 8.3 ± 0.3 g L−1 of xylose remained, resulting in a product on substrate yield for the tyramine production on xylose that exceeded the yield on ribose. These results indicated that both ribose and xylose serve as suitable alternative carbon sources to glucose, allowing for a sustainable tyramine production with the engineered C. glutamicum strains.

Bioreactor batch-mode fermentation for the production of tyramine

Since the overexpression of tdcLb in AROM3 led to successful tyramine production on the carbon sources glucose and xylose with similar substrate yield coefficients (0.040 ± 0.003 g g−1 glucose and 0.037 ± 0.001 g g−1 xylose), it was evaluated whether the tyramine production can be upscaled to bioreactor cultivation in a stable manner. AROM3 tdcLb and AROM3 tdcLb xylAXcBCg were cultivated in bioreactors with 1.5 L CGXII minimal medium with 40 g L−1 glucose or 40 g L−1 xylose, respectively. Since higher biomass formation was expected during bioreactor cultivation, 1 mM l-phenylalanine and l-tryptophan, each, was supplemented to ensure that neither of these amino acids would be growth limiting.

In comparison to shake flask cultivation, during which glucose was entirely consumed after 72 h, glucose was consumed after 20 h of fermentation in the bioreactor cultivation. For the strain AROM3 tdcLb, the maximum CDW of 8.6 g L−1was reached after 12 h of fermentation (Fig. 5A), which is approximately 28% higher than that obtained during shake flask cultivation (Supplementary Fig. S2). This higher growth was at the expense of tyramine production, as the final tyramine titer of 1 g L−1 corresponded to approximately 63% of the tyramine titers achieved in shake flask cultivation on glucose after 72 h (Table 2). Nevertheless, this tyramine titer was achieved after 24 h of fermentation, resulting in a nearly twofold increase in volumetric productivity of 0.040 g L−1 h−1 compared to 0.022 g L−1 h−1 observed for shake flask cultivation. These results indicate that the upscaling to bioreactor cultivation accelerated glucose consumption and tyramine production with AROM3 tdcLb. However, this was accompanied by the accumulation of 0.27 g L−1 l-tyrosine at the end of fermentation, which suggests that the decarboxylation of l-tyrosine by TdcLb activity became the limiting step during bioreactor cultivation.

Fig. 5.

Tyramine production by C. glutamicum AROM3 strains expressing tdcLb in batch bioreactor cultivation. Strains AROM3 tdcLb (A) and AROM3 tdcLb xylAXcBCg (B) were cultivated in 1.5 L CGXII minimal medium without MOPS containing 40 g L−1 of either glucose or xylose as a carbon source, respectively, and supplemented with 1 mM l-phenylalanine, 1 mM l-tryptophan, and 1 mM IPTG. Fermentations were performed with an initial OD600 of 1 at 30 °C and pH 7.0 with a constant aeration rate of 0.3 NL min−.1

Similar to shake flask cultivations, strain AROM3 tdcLb xylAXcBCg grown in the bioreactor with CGXII minimal medium containing 40 g L−1 xylose exhibited slower growth compared to AROM3 tdcLb grown on glucose (Fig. 5B), reaching the stationary phase after 36 h. Throughout the fermentation process, l-tyrosine did not accumulate to considerable concentrations, indicating its complete conversion into tyramine. After 72 h of fermentation, tyramine accumulated to a titer of 1 g L−1 with a volumetric productivity of 0.013 g L−1 h−1 and a substrate yield of 0.038 g g−1 xylose. These results are comparable to those obtained in shake flask cultivation using xylose as a carbon source (Table 2). Overall, the upscaling of tyramine production on xylose as carbon source to a 1.5 L scale was stable, allowing for a sustainable fermentative tyramine production with AROM3 tdcLb xylAXcBCg.

Discussion

We have successfully established the de novo production of tyramine in C. glutamicum from glucose, ribose, and xylose and demonstrated the transfer to a 1.5 L bioreactor cultivation operated in batch mode. Upon overexpression of tdc from L. brevis in the l-tyrosine overproducing strain AROM3, only tyramine was produced, with neither 2-PEA nor tryptamine being detected. In contrast, AROM3 strains overexpressing an AADC gene from either Bacillus atrophaeus, Clostridium sporogenes, or Ruminococcus gnavus produced tryptamine (0.1 g L−1) as well as 2-PEA (0.01 g L−1) in the case of AROM3 aaDCBa, and AROM3 aaDCRg. Although we cannot exclude differences regarding the expression levels of the AADC genes, our results are consistent with the biochemical characterization of these enzymes as AADCCs and AADCRg have been demonstrated to exhibit up to 1000-fold higher efficiency in decarboxylating l-tryptophan relative to l-tyrosine (Williams et al. 2014). Similarly, AADCBa has been shown to have a 50-fold higher activity for l-tryptophan compared to l-tyrosine (Choi et al. 2021). Conversely, TdcLb has been characterized to exhibit specificity for l-tyrosine, while accepting neither l-tryptophan nor l-phenylalanine as substrate (Moreno-Arribas and Lonvaud-Funel 2001; Zhang and Ni 2014).

The strain AROM3 tdcLb, which overexpresses the gene for Tdc from L. brevis, produced approximately 43 mol-% more tyramine (1.9 ± 0.1 g L−1) in shake flasks than the empty vector carrying control strain, AROM3 EV, produced l-tyrosine (1.7 ± 0.1 g L−1). This metabolic pull effect could be explained by the decarboxylation of l-tyrosine to tyramine, which reduces the feedback inhibition by this amino acid on its own biosynthesis pathway. This pathway contains three reactions that are known to be inhibited by l-tyrosine. Firstly, the DAHP synthases, which provide DAHP for the shikimate pathway, are feedback-inhibited by all three proteinogenic aromatic amino acids (Hagino and Nakayama 1974a). However, the gene encoding the feedback-inhibition resistant mutant of DAHP synthase from E. coli (aroGEcfbr) was integrated into the genome of AROM3. This DAHP synthase mutant was demonstrated to be insensitive to feedback-inhibition by l-phenylalanine concentrations up to 10 mM (Kikuchi et al. 1997). Furthermore, the overexpression of aroGEcfbr in E. coli allowed for a production of approximately 0.2 g L−1 l-tyrosine, while no l-tyrosine production was detected for its parental strain (Kim et al. 2018). Therefore, AroGEcfbr remains active in AROM3, whereas the native DAHP synthases are inhibited. Furthermore, the activities of the native chorismate mutase (Csm) and the native arogenate dehydrogenase (TyrA) are reduced in vitro to 40% and 50%, respectively, in the presence of 1 mM l-tyrosine (Hagino and Nakayama 1974b, 1975). Because of its decarboxylation, the l-tyrosine concentration in supernatants of the AROM3 tdcLb cultures is reduced to concentrations below 0.2 mM after 48 h of shake flask cultivation (Supplementary Fig. S3). It is reasonable to assume that the decarboxylation of l-tyrosine to tyramine results in a similarly low intracellular l-tyrosine concentration. Under these conditions, Csm and TyrA would hardly be subjected to feedback inhibition by l-tyrosine. This would allow for an elevated l-tyrosine biosynthesis, which by subsequent l-tyrosine decarboxylation results in a higher tyramine production.

The de novo tyramine production described here (1.9 ± 0.1 g L−1 after 72 h of cultivation) is not yet economically viable since titer, yield and volumetric productivity have to be improved. The addition of yeast extract and tryptone, which generally support better growth and higher production titers in biotechnology, but also significantly increase costs (Sikder et al. 2012), boosted an E. coli process (Yang et al. 2022) to a comparable performance (1.965 ± 0.205 g L−1 after 72 h of cultivation) as our C. glutamicum process. However, as compared to this and other biotechnological approaches, our study stands out, as it does not require yeast extract and tryptone.

Given that l-tyrosine was completely decarboxylated to tyramine by AROM3 tdcLb at the end of shake flask cultivation as well as bioreactor cultivation on xylose, it can be concluded that the l-tyrosine synthesis represents the bottleneck under these conditions. Consequently, optimizing the l-tyrosine supply is essential for achieving higher tyramine titers in the future. In C. glutamicum, l-tyrosine is synthesized via the l-arogenate pathway, which involves the transamination of prephenate to l-arogenate, followed by its decarboxylation to l-tyrosine (Fazel and Jensen 1979). In several bacteria, including E. coli, l-tyrosine is synthesized via the 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate (4-OHPP) pathway, where the order of decarboxylation and transamination is reversed as compared to the l-arogenate pathway (Koch et al. 1971; Gelfand and Steinberg 1977). Overexpressing the E. coli 4-OHPP pathway enzyme genes tyrAEc and tyrBEc, in addition to the native l-tyrosine synthesis pathway in AROM3 tdcLb, would result in a bifurcated pathway (in parallel via l-arogenate and via 4-OHPP) potentially increasing l-tyrosine formation. A pronounced increase in tyramine concentrations was observed after 12 h and 36 h of bioreactor cultivation on glucose and xylose, respectively. This correlated with the time when the supplemented l-phenylalanine and l-tryptophan were entirely consumed for both bioreactor cultivations. This suggests that, despite the overexpression of the E. coli aroGEcfbr, l-tyrosine production was inhibited by the supplemented amino acids. A potential explanation for this observation is that AroGEcfbr is unable to sufficiently compensate for the native DAHP synthases that are inhibited by the supplemented amino acids. The transcription of the DAHP synthase gene aroF was demonstrated to be attenuated by aroR in the presence of l-phenylalanine (Neshat et al. 2014). Consequently, a potential strategy to mitigate the inhibitory effects on l-tyrosine biosynthesis could involve the mutation of the aroR stop codon to prevent reduction in aroF expression in the presence of l-phenylalanine and probably also l-tyrosine. To additionally alleviate l-tyrosine biosynthesis from feedback inhibition, endogenous Csm and TyrA mutants resistant to feedback-inhibition might/could be identified in a screening approach similar to the identification of a feedback-inhibition resistant mutant of the chorismate mutase/prephenate dehydrogenase TyrAEcfbr from E. coli (Lütke-Eversloh and Stephanopoulos 2005).

A further optimized l-tyrosine supply in AROM3 tdcLb might result in the decarboxylation step becoming rate limiting for tyramine production. A first indication is the finding that AROM3 tdcLb grown with glucose in the bioreactor culture showed a faster glucose consumption and tyramine production, but accumulated l-tyrosine as by-product (Fig. 5). To avoid an incomplete conversion of l-tyrosine upon faster glucose consumption, its decarboxylation should be improved in the future. A number of bacterial decarboxylases assist in maintaining pH homeostasis under acidic stress, since decarboxylation is associated with H+-ion consumption and consequently display elevated activity at low pH (Bearson et al. 1997; Viala et al. 2011). For instance, TdcLb exhibits the highest activity at pH 5 (Zhang and Ni 2014). Accordingly, a two-phase production process, similar to that established for γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production with Bacillus methanolicus (Irla et al. 2017), comprising an initial phase at pH 7 for cell growth and l-tyrosine accumulation, followed by a second phase at a reduced pH for its decarboxylation into tyramine, may prove advantageous to facilitate tyramine production. Alternatively, bioinformatics and protein engineering could be combined to predict and screen for TdcLb mutants with enhanced activity at neutral pH conditions (Suplatov et al. 2015).

Another potential avenue for enhancing tyramine production is transport engineering. For example, overexpression of the endogenous aromatic amino acid importer gene aroP to increase the reuptake of excreted l-tyrosine (Wehrmann et al. 1995) may increase tyramine production, especially regarding the glucose bioreactor fermentation, during which l-tyrosine accumulated in the culture. Furthermore, the identification and overexpression of the tyramine exporter gene represents another promising strategy for enhancing tyramine production in the future. Currently, a tyramine transporter is unknown, however, it is reasonable to assume that AroP is not responsible, given that the amino acids l-lysine and l-ornithine do have transporters that differ from the transporters of their corresponding decarboxylation products cadaverine and putrescine (Pérez-García and Wendisch 2018).

The division of labor is frequently discussed in the context of the application of engineered microbial consortia for biotechnological production (Sgobba and Wendisch 2020). This is due to the fact that the distribution of different tasks of bioprocesses among different populations reduces the metabolic burden of each individual population. Consequently, the strategic engineering of microbial consortia has the potential to result in the development of more efficient bioprocesses when compared to a single population (Zhou et al. 2015; Tsoi et al. 2018). A consortium of two genetically engineered E. coli strains has recently been established for cadaverine production. One strain was genetically modified to overproduce l-lysine, while the other strain decarboxylated l-lysine into cadaverine. This prevented feedback inhibition due to high intracellular cadaverine concentrations in the l-lysine overproducer (Wang et al. 2018). It is conceivable to use consortia for tyramine production, e.g., by co-cultivation of C. glutamicum AROM3, which overproduces l-tyrosine, and an L. brevis strain that decarboxylates l-tyrosine to tyramine. However, the solubility of l-tyrosine in water is less than 0.5 g L−1. Therefore, the l-tyrosine secreted by AROM3 into the medium would rapidly precipitate. After uptake of the dissolved l-tyrosine by L. brevis and its decarboxylation into tyramine, l-tyrosine would be dissolved again. However, this process would require time, making it beneficial to combine l-tyrosine production and its decarboxylation in one organism rather than a consortium as done here.

The engineering of AROM3 tdcLb for the utilization of ribose and xylose as alternative carbon sources resulted in g tyramine per g substrate yields comparable to those observed for the tyramine production on glucose. Moreover, the upscaling of the xylose-based tyramine production to the 1.5 L scale was demonstrated to be stable, allowing for a sustainable fermentative production of tyramine. As a potential avenue for further optimization, a fed-batch tyramine production process could be established in the future with the aim of achieving higher tyramine titers. Moreover, an evolved xylAXcBCg module with a duplication of the 5′ untranslated region and the beginning of the xylAXc gene was demonstrated to improve the growth of C. glutamicum on xylose (Werner et al. 2023). The genomic integration of this module into AROM3 tdcLb could alleviate the plasmid burden. By extending the substrate spectrum of AROM3 tdcLb xylAXcBCg to arabinose in addition to xylose, it would be possible to utilize hydrolysates of lignocellulosic agricultural wastes, which contain high amounts of these two pentoses, in more efficient manner (Aristidou and Penttilä 2000). For instance, xylose and arabinose collectively comprise approximately 50% (w/w) of all carbohydrates in rice straw or wheat bran hydrolysates (Gopinath et al. 2011). Another avenue for sustainable tyramine production from waste material is a consortium with a partner that is capable of degrading sustainable feedstocks. Potential partners for this include Trichoderma reesei or an α-amylase secreting E. coli strain, which allow for the utilization of microcrystalline cellulose and alkaline pretreated corn stover or starch. These have recently been demonstrated to be suitable consortium partners in sustainable biotechnological processes (Scholz et al. 2018; Sgobba et al. 2018).

Biotransformation of l-tyrosine to tyramine is another option for sustainable tyramine production from food wastes with a high protein content (Wohlgemuth 2022). When AROM3 tdcLb is cultivated on waste materials with a high l-tyrosine content, the l-tyrosine can be imported into the cell and, in addition to the metabolically produced l-tyrosine, be decarboxylated into tyramine. Potential waste materials for this approach include orange peel, brewing cake, and pumpkin kernel cake, which contain 2 to 14 mg l-tyrosine per g dry matter (Prandi et al. 2019). Notably, an orange peel hydrolysate containing 34 mg L−1 l-tyrosine successfully supported growth and l-tyrosine production by C. glutamicum AROM3 (Junker et al. 2024). Orange peel and brewing cake accumulate to a considerable extent, amounting up to 20 million tons per year (Thiago et al. 2014; Aboagye et al. 2017). Also, pumpkin kernel cake is abundant with approximately 11,500 tons being produced annually as a by-product of pumpkin seed oil production (Balbino et al. 2019).

Consequently, with the metabolic optimization described above and the utilization of agricultural side streams, the proof-of-concept of sustainable tyramine production by C. glutamicum developed in this study might lead to an economically viable and environmentally friendly sustainable tyramine production process in the near future. Moreover, the engineered C. glutamicum strain may be used for extension of the tyramine production pathway by acetylation or hydroxylation steps to yield N-acetyltyramine or dopamine, respectively (Chenprakhon et al. 2017; Pan et al. 2023), or to obtain its anti-inflammatory derivative tyrosol (Satoh et al. 2012).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contribution

S–S.P. and N.J. performed phylogenetic analysis, cloned strains, performed experiments, and quantified products via HPLC analysis. S–S.P., N.J., and F.M. performed batch fermentation. V.F.W. acquired funding, conceived and designed the study. S–S.P., N.J., and V.F.W. drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. We acknowledge the financial support of the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Open Access Publication Fund of Bielefeld University for the article processing charge. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Data availability

All data are present in the manuscript and its Supplement.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sara-Sophie Poethe and Nora Junker contributed equally to this work.

References

- Aboagye D, Banadda N, Kiggundu N, Kabenge I (2017) Assessment of orange peel waste availability in Ghana and potential bio-oil yield using fast pyrolysis. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 70:814–821. 10.1016/j.rser.2016.11.262 [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25:3389–3402. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aristidou A, Penttilä M (2000) Metabolic engineering applications to renewable resource utilization. Curr Opin Biotechnol 11:187–198. 10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00085-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbino S, Dorić M, Vidaković S, Kraljić K, Škevin D, Drakula S, Voučko B, Čukelj N, Obranović M, Ćurić D (2019) Application of cryogenic grinding pretreatment to enhance extractability of bioactive molecules from pumpkin seed cake. J Food Process Eng 42:e13300. 10.1111/jfpe.13300 [Google Scholar]

- Bampidis V, Azimonti G, de Lourdes BM, Christensen H, Dusemund B, Kouba M, Kos Durjava M, López-Alonso M, López Puente S, Marcon F, Mayo B, Pechová A, Petkova M, Sanz Y, Villa RE, Woutersen R, Costa L, Dierick N, Flachowsky G, Glandorf B, Mantovani A, Wallace RJ, Anguita M, Manini P, Tarrés-Call J, Ramos F (2019) Safety and efficacy of l-tryptophan produced by fermentation with Corynebacterium glutamicum KCCM 80176 for all animal species. EFSA J 17:e05729. 10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearson S, Bearson B, Foster JW (1997) Acid stress responses in enterobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett 147:173–180. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10238.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertani G (1951) Studies on lysogenesis I: the mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 62:293–300. 10.1128/jb.62.3.293-300.1951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blombach B, Seibold GM (2010) Carbohydrate metabolism in Corynebacterium glutamicum and applications for the metabolic engineering of l-lysine production strains. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 86:1313–1322. 10.1007/s00253-010-2537-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez-Béjar MI, Báez-Viveros JL, Martínez A, Bolívar F, Gosset G (2012) Biotechnological production of l-tyrosine and derived compounds. Process Biochem 47:1017–1026. 10.1016/j.procbio.2012.04.005 [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, He X, Lv J, Xiao H, Tan W, Wang Y, Hu J, Zeng K, Yang G (2023) A new bio-based thermosetting with amorphous state, sub-zero softening point and high curing efficiency. Polymer 264:125518. 10.1016/j.polymer.2022.125518 [Google Scholar]

- Chenprakhon P, Dhammaraj T, Chantiwas R, Chaiyen P (2017) Hydroxylation of 4-hydroxyphenylethylamine derivatives by R263 variants of the oxygenase component of p-hydroxyphenylacetate-3-hydroxylase. Arch Biochem Biophys 620:1–11. 10.1016/j.abb.2017.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Han S-W, Kim J-S, Jang Y, Shin J-S (2021) Biochemical characterization and synthetic application of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase from Bacillus atrophaeus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 105:2775–2785. 10.1007/s00253-021-11122-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driche EH, Badji B, Bijani C, Belghit S, Pont F, Mathieu F, Zitouni A (2022) A new Saharan strain of Streptomyces sp. GSB-11 produces maculosin and N-acetyltyramine active against multidrug-resistant pathogenic bacteria. Curr Microbiol 79:298. 10.1007/s00284-022-02994-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggeling L, Bott M (2005) Handbook of Corynebacterium glutamicum. CRC Press, Bosa Roca [Google Scholar]

- Fazel AM, Jensen RA (1979) Obligatory biosynthesis of l-tyrosine via the pretyrosine branchlet in coryneform bacteria. J Bacteriol 138:805–815. 10.1128/jb.138.3.805-815.1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand DH, Steinberg RA (1977) Escherichia coli mutants deficient in the aspartate and aromatic amino acid aminotransferases. J Bacteriol 130:429–440. 10.1128/jb.130.1.429-440.1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstmeir R, Wendisch VF, Schnicke S, Ruan H, Farwick M, Reinscheid D, Eikmanns BJ (2003) Acetate metabolism and its regulation in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biotechnol 104:99–122. 10.1016/S0168-1656(03)00167-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang R-Y, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, Smith HO (2009) Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods 6:343–345. 10.1038/nmeth.1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannini L, Migliori M, Filippi C, Origlia N, Panichi V, Falchi M, Bertelli AAE, Bertelli A (2002) Inhibitory activity of the white wine compounds, tyrosol and caffeic acid, on lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha release in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Int J Tissue React 24:53–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath V, Meiswinkel TM, Wendisch VF, Nampoothiri KM (2011) Amino acid production from rice straw and wheat bran hydrolysates by recombinant pentose-utilizing Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 92:985–996. 10.1007/s00253-011-3478-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagino H, Nakayama K (1974a) DAHP Synthetase and its control in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Agric Biol Chem 38:2125–2134. 10.1080/00021369.1974.10861482 [Google Scholar]

- Hagino H, Nakayama K (1974b) Regulatory properties of prephenate dehydrogenase and prephenate dehydratase from Corynebacterium glutamicum. Agric Biol Chem 38:2367–2376. 10.1080/00021369.1974.10861536 [Google Scholar]

- Hagino H, Nakayama K (1975) Regulatory properties of chorismate mutase from Corynebacterium glutamicum. Agric Biol Chem 39:331–342. 10.1080/00021369.1975.10861620 [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D (1983) Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol 166:557–580. 10.1016/S0022-2836(83)80284-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupka C (2020) chaupka/codon_harmonization: release v1.2.0. 10.5281/ZENODO.4062177

- Hegedűs L, Máthé T (2005) Selective heterogeneous catalytic hydrogenation of nitriles to primary amines in liquid phase: Part I. Hydrogenation of benzonitrile over palladium. Appl Catal Gen 296:209–215. 10.1016/j.apcata.2005.08.024 [Google Scholar]

- Ippolito RM, Vigmond S (1988) Process for preparing substituted phenol ethers via oxazolidine-structure intermediates. US Patent No. 4,760,182. U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, Washington, DC

- Irla M, Nærdal I, Brautaset T, Wendisch VF (2017) Methanol-based γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production by genetically engineered Bacillus methanolicus strains. Ind Crops Prod 106:12–20. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.11.050 [Google Scholar]

- Jones BN, Gilligan JP (1983) o-Phthaldialdehyde precolumn derivatization and reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography of polypeptide hydrolysates and physiological fluids. J Chromatogr A 266:471–482. 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)90918-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junker N, Sariyar Akbulut B, Wendisch VF (2024) Utilization of orange peel waste for sustainable amino acid production by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 12:1419444. 10.3389/fbioe.2024.1419444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi H, Sasaki M, Vertès AA, Inui M, Yukawa H (2008) Engineering of an l-arabinose metabolic pathway in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 77:1053–1062. 10.1007/s00253-007-1244-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerbs A, Mindt M, Schwardmann L, Wendisch VF (2021) Sustainable production of N-methylphenylalanine by reductive methylamination of phenylpyruvate using engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microorganisms 9:824. 10.3390/microorganisms9040824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerbs A, Burgardt A, Veldmann KH, Schäffer T, Lee J-H, Wendisch VF (2022) Fermentative production of halogenated tryptophan derivatives with Corynebacterium glutamicum overexpressing tryptophanase or decarboxylase genes. ChemBioChem 23:e202200007. 10.1002/cbic.202200007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kezmarsky ND, Xu H, Graham DE, White RH (2005) Identification and characterization of a l-tyrosine decarboxylase in Methanocaldococcusjannaschii. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) - Gen Subj 1722:175–182. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi Y, Tsujimoto K, Kurahashi O (1997) Mutational analysis of the feedback sites of phenylalanine-sensitive 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase of Escherichiacoli. Appl Environ Microbiol 63:761–762. 10.1128/aem.63.2.761-762.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B, Binkley R, Kim HU, Lee SY (2018) Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the enhanced production of l-tyrosine. Biotechnol Bioeng 115:2554–2564. 10.1002/bit.26797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner O, Tauch A (2003) Tools for genetic engineering in the amino acid-producing bacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biotechnol 104:287–299. 10.1016/S0168-1656(03)00148-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch GL, Shaw DC, Gibson F (1971) The purification and characterisation of chorismate mutase-prephenate dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli K12. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) – Protein Structure 229:795–804. 10.1016/0005-2795(71)90298-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurpejović E, Burgardt A, Bastem GM, Junker N, Wendisch VF, Sariyar Akbulut B (2023) Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for l-tyrosine production from glucose and xylose. J Biotechnol 363:8–16. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2022.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Rho J, Messersmith PB (2009) Facile conjugation of biomolecules onto surfaces via mussel adhesive protein inspired coatings. Adv Mater 21:431–434. 10.1002/adma.200801222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W, Kim M-A, Park I, Hwang JS, Na M, Bae J-S (2017) Novel direct factor Xa inhibitory compounds from Tenebrio molitor with anti-platelet aggregation activity. Food Chem Toxicol 109:19–27. 10.1016/j.fct.2017.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, Bork P (2021) Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 49:W293–W296. 10.1093/nar/gkab301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuschner RG, Heidel M, Hammes WP (1998) Histamine and tyramine degradation by food fermenting microorganisms. Int J Food Microbiol 39:1–10. 10.1016/S0168-1605(97)00109-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Huo L, Pulley C, Liu A (2012) Decarboxylation mechanisms in biological system. Bioorganic Chem 43:2–14. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2012.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Tao Y (2017) Whole-cell biocatalysts by design. Microb Cell Factories 16:106. 10.1186/s12934-017-0724-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Fang, Xu Wenjuan, Du Lihui, Wang Daoying, Zhu Yongzhi, Geng Zhiming, Zhang Muhan, Xu Weimin (2014) Heterologous Expression and Characterization of Tyrosine Decarboxylase from Enterococcus faecalis R612Z1 and Enterococcus faecium R615Z1. J Food Prot 77(4):592–598. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lütke-Eversloh T, Stephanopoulos G (2005) Feedback inhibition of chorismate mutase/prephenate dehydrogenase (TyrA) of Escherichia coli: generation and characterization of tyrosine-Insensitive Mutants. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:7224–7228. 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7224-7228.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister MI, Boulho C, McMillan L, Gilpin LF, Wiedbrauk S, Brennan C, Lennon D (2018) The production of tyramine via the selective hydrogenation of 4-hydroxybenzyl cyanide over a carbon-supported palladium catalyst. RSC Adv 8:29392–29399. 10.1039/C8RA05654D [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey BD, Park HB, Ju H, Rowe BW, Miller DJ, Chun BJ, Kin K, Freeman BD (2010) Influence of polydopamine deposition conditions on pure water flux and foulant adhesion resistance of reverse osmosis, ultrafiltration, and microfiltration membranes. Polymer 51:3472–3485. 10.1016/j.polymer.2010.05.008 [Google Scholar]

- Meiswinkel TM, Gopinath V, Lindner SN, Nampoothiri KM, Wendisch VF (2013) Accelerated pentose utilization by Corynebacterium glutamicum for accelerated production of lysine, glutamate, ornithine and putrescine. Microb Biotechnol 6:131–140. 10.1111/1751-7915.12001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindt M, Beyraghdar Kashkooli A, Suarez-Diez M, Ferrer L, Jilg T, Bosch D, Martins dos Santos V, Wendisch VF, Cankar K (2022) Production of indole by Corynebacterium glutamicum microbial cell factories for flavor and fragrance applications. Microb Cell Factories 21:45. 10.1186/s12934-022-01771-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Arribas V, Lonvaud-Funel A (2001) Purification and characterization of tyrosine decarboxylase of Lactobacillus brevis IOEB 9809 isolated from wine. FEMS Microbiol Lett 195:103–107. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10505.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neshat A, Mentz A, Rückert C, Kalinowski J (2014) Transcriptome sequencing revealed the transcriptional organization at ribosome-mediated attenuation sites in Corynebacterium glutamicum and identified a novel attenuator involved in aromatic amino acid biosynthesis. J Biotechnol 190:55–63. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okai N, Miyoshi T, Takeshima Y, Kuwahara H, Ogino C, Kondo A (2016) Production of protocatechuic acid by Corynebacterium glutamicum expressing chorismate-pyruvate lyase from Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100:135–145. 10.1007/s00253-015-6976-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H, Li H, Wu S, Lai C, Guo D (2023) De novo biosynthesis of N-acetyltyramine in engineered Escherichia coli. Enzyme Microb Technol 162:110149. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2022.110149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-García F, Wendisch VF (2018) Transport and metabolic engineering of the cell factory Corynebacteriumglutamicum. FEMS Microbiol Lett 365:fny166. 10.1093/femsle/fny166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prandi B, Faccini A, Lambertini F, Bencivenni M, Jorba M, Van Droogenbroek B, Bruggeman G, Schöber J, Petrusan J, Elst K, Sforza S (2019) Food wastes from agrifood industry as possible sources of proteins: a detailed molecular view on the composition of the nitrogen fraction, amino acid profile and racemisation degree of 39 food waste streams. Food Chem 286:567–575. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.01.166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis AC, Salis HM (2020) An automated model test system for systematic development and improvement of gene expression models. ACS Synth Biol 9:3145–3156. 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittmann D, Lindner SN, Wendisch VF (2008) Engineering of a glycerol utilization pathway for amino acid production by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:6216–6222. 10.1128/AEM.00963-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russel D (2001) Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- Satoh Y, Tajima K, Munekata M, Keasling JD, Lee TS (2012) Engineering of a tyrosol-producing pathway, utilizing simple sugar and the central metabolic tyrosine, in Escherichia coli. J Agric Food Chem 60:979–984. 10.1021/jf203256f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J, Niermann K, Wendisch VF (2011) Production of the amino acids l-glutamate, l-lysine, l-ornithine and l-arginine from arabinose by recombinant Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biotechnol 154:191–198. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz SA, Graves I, Minty JJ, Lin XN (2018) Production of cellulosic organic acids via synthetic fungal consortia. Biotechnol Bioeng 115:1096–1100. 10.1002/bit.26509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz A, Gepp MM, Stracke F, von Briesen H, Neubauer JC, Zimmermann H (2019) Tyramine-conjugated alginate hydrogels as a platform for bioactive scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A 107:114–121. 10.1002/jbm.a.36538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgobba E, Wendisch VF (2020) Synthetic microbial consortia for small molecule production. Curr Opin Biotechnol 62:72–79. 10.1016/j.copbio.2019.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgobba E, Stumpf AK, Vortmann M, Jagmann N, Krehenbrink M, Dirks-Hofmeister ME, Moerschbacher B, Philipp B, Wendisch VF (2018) Synthetic Escherichia coli-Corynebacterium glutamicum consortia for l-lysine production from starch and sucrose. Bioresour Technol 260:302–310. 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.03.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon RA, Woodley JM (2018) Role of biocatalysis in sustainable chemistry. Chem Rev 118:801–838. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG (2011) Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7:539. 10.1038/msb.2011.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikder J, Roy M, Dey P, Pal P (2012) Techno-economic analysis of a membrane-integrated bioreactor system for production of lactic acid from sugarcane juice. Biochem Eng J 63:81–87. 10.1016/j.bej.2011.11.004 [Google Scholar]

- Stansen C, Uy D, Delaunay S, Eggeling L, Goergen J-L, Wendisch VF (2005) Characterization of a Corynebacterium glutamicum lactate utilization operon induced during temperature-triggered glutamate production. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:5920–5928. 10.1128/AEM.71.10.5920-5928.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suplatov D, Voevodin V, Švedas V (2015) Robust enzyme design: bioinformatic tools for improved protein stability. Biotechnol J 10:344–355. 10.1002/biot.201400150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The UniProt Consortium (2021) UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res 49:D480–D489. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiago RDSM, Pedro PMDM, Eliana FCS (2014) Solid wastes in brewing process: a review. J Brew Distill 5:1–9. 10.5897/JBD2014.0043 [Google Scholar]

- Torrens-Spence MP, Pluskal T, Li F-S, Carballo V, Weng J-K (2018) Complete pathway elucidation and heterologous reconstitution of Rhodiola salidroside biosynthesis. Mol Plant 11:205–217. 10.1016/j.molp.2017.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trifinopoulos J, Nguyen L-T, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ (2016) W-IQ-TREE: a fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 44:W232–W235. 10.1093/nar/gkw256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoi R, Wu F, Zhang C, Bewick S, Karig D, You L (2018) Metabolic division of labor in microbial systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115:2526–2531. 10.1073/pnas.1716888115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldmann KH, Dachwitz S, Risse JM, Lee J-H, Sewald N, Wendisch VF (2019) Bromination of l-tryptophan in a fermentative process with Corynebacterium glutamicum. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 291:7–16. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2018.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viala JPM, Méresse S, Pocachard B, Guilhon A-A, Aussel L, Barras F (2011) Sensing and adaptation to low pH mediated by inducible amino acid decarboxylases in Salmonella. PLoS ONE 6:e22397. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Lu X, Ying H, Ma W, Xu S, Wang X, Chen K, Ouyang P (2018) A novel process for cadaverine bio-production using a consortium of two engineered Escherichia coli. Front Microbiol 9:1312. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrmann A, Morakkabati S, Krämer R, Sahm H, Eggeling L (1995) Functional analysis of sequences adjacent to dapE of Corynebacterium glutamicum reveals the presence of aroP, which encodes the aromatic amino acid transporter. J Bacteriol 177:5991–5993. 10.1128/jb.177.20.5991-5993.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendisch VF (2020) Metabolic engineering advances and prospects for amino acid production. Metab Eng 58:17–34. 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner F, Schwardmann LS, Siebert D, Rückert-Reed C, Kalinowski J, Wirth M-T, Hofer K, Takors R, Wendisch VF, Blombach B (2023) Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for fatty alcohol production from glucose and wheat straw hydrolysate. Biotechnol Biofuels 16:116. 10.1186/s13068-023-02367-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BB, Van Benschoten AH, Cimermancic P, Donia MS, Zimmermann M, Taketani M, Ishihara A, Kashyap PC, Fraser JS, Fischbach MA (2014) Discovery and characterization of gut microbiota decarboxylases that can produce the neurotransmitter tryptamine. Cell Host Microbe 16:495–503. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlgemuth R (2022) Selective biocatalytic defunctionalization of raw materials. Chemsuschem 15:e202200402. 10.1002/cssc.202200402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S, Becker J, Tsuge Y, Kawaguchi H, Kondo A, Marienhagen J, Bott M, Wendisch VF, Wittmann C (2021) Advances in metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum to produce high-value active ingredients for food, feed, human health, and well-being. Essays Biochem 65:197–212. 10.1042/EBC20200134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Wu P, Zhang Y, Cao M, Yuan J (2022) High-titre production of aromatic amines in metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. J Appl Microbiol 133:2931–2940. 10.1111/jam.15745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H-S, Ma L-Q, Zhang J-X, Shi G-L, Hu Y-H, Wang Y-N (2011) Characterization of glycosyltransferases responsible for salidroside biosynthesis in Rhodiola sachalinensis. Phytochemistry 72:862–870. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Ni Y (2014) Tyrosine decarboxylase from Lactobacillus brevis: soluble expression and characterization. Protein Expr Purif 94:33–39. 10.1016/j.pep.2013.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Zhang J, Kang Z, Du G, Chen J (2015) Rational engineering of multiple module pathways for the production of l-phenylalanine in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 42:787–797. 10.1007/s10295-015-1593-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou K, Qiao K, Edgar S, Stephanopoulos G (2015) Distributing a metabolic pathway among a microbial consortium enhances production of natural products. Nat Biotechnol 33:377–383. 10.1038/nbt.3095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Zhou C, Wang Y, Li C (2020) Transporter engineering for microbial manufacturing. Biotechnol J 15:1900494. 10.1002/biot.201900494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are present in the manuscript and its Supplement.