Abstract

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy serves as the standard of care for individuals with advanced stages of gastric cancer. Nevertheless, the emergence of chemoresistance in GC has detrimental impacts on prognosis, yet the underlying mechanisms governing this phenomenon remain elusive. Level of mitophagy and ferroptosis of GC cells were detected by fluorescence, flow cytometry, GSH, MDA, Fe2+ assays, and to explore the specific molecular mechanisms between NPR1 and cisplatin resistance by performing western blot and coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays. These results indicates that NPR1 positively correlated with cisplatin-resistance and played a crucial part in conferring resistance to cisplatin in gastric cancer cells. Mechanistically, NPR1 affected levels of mitophagy and ferroptosis in human cisplatin-resistance GC cells with cisplatin treatment. Specifically, NPR1 inhibited mitophagy-dependent ferroptosis by reducing the ubiquitination-mediated degradation of PARL; moreover, NPR1 promoted PARL stabilization by disrupting the PARL–MARCH8 complex, which ultimately led to the development of chemoresistance in GC cells. Considering our findings, NPR1 appears to play an important role in chemotherapy for GC. NPR1 could potentially be used to overcome chemotherapy resistance.

Graphical Abstract

1. NPR1 is highly expressed in cisplatin-resistant GC cells and promotes the cisplatin resistance.

2. According to IP-MS, NPR1 inhibits mitophagy-dependent ferroptosis through its downstream protein PARL.

3. NPR1 promoted PARL stabilization by disrupting the PARL–MARCH8 complex to inhibit the ubiquitination-mediated degradation of PARL.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10565-024-09931-z.

Keywords: NPR1, PARL, Gastric Cancer, Mitophagy, Ferroptosis, Chemoresistance, Ubiquitination

Introduction

Annually, gastric cancer is diagnosed in over a million individuals globally. GC is among the most prevalent malignancies on the planet (López et al. 2023). GC, which is often diagnosed at advanced stages, has a high mortality rate, making it the third most significant contributor to cancer-related deaths. Currently, nonsurgical therapies for GC predominantly involve conventional methods such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy (Guan et al. 2023).

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy is the recommended treatment for advanced GC. Despite the efficacy of chemotherapy, progression to chemoresistance is a key obstacle to improving the prognosis of GC. Therefore, it is important to identify the underlying mechanisms and develop new therapeutic strategies.

Advanced GC are suggested to be treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Chemoresistance remains one of the biggest obstacles to improving prognoses. The identification of the underlying mechanisms and the development of new therapeutic strategies are therefore crucial.

Natriuretic peptide receptor A (NPR1) is an important receptor of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), and it has been demonstrated that ANP–NPR1 pathway affects the process of tumorigenesis, such as tumor proliferation and migration (Li et al. 2021). Studies previously conducted by our team have demonstrated the conclusions: NPR1 promotes fatty acid metabolism and the proliferation of GC cells by binding to PPARα (Cao et al. 2023). One recent study showed that silencing NPR1 causes cells to lose viability and proliferation because it induces cytoprotective autophagy and accumulates reactive oxygen species (ROS), and NPR1 can also influence drug resistance in GC by affecting stemness and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) (Chen et al. 2023). FAO and ROS levels are inextricably linked. Impaired FAO in mitochondria causes lipid accumulation, excessive ROS production and oxidative damage (Zeng et al. 2022). An autophagic process that removes damaged or unwanted mitochondrial fractions from cells is termed mitophagy, which is a two-edged sword in the development of tumors (Picca et al. 2023). Ferroptosis, iron accumulates in the cells, ROS are generated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) accumulate in the phospholipids, resulting in intracellular, iron-dependent cell death In the process, lipid cross-linking interferes with the normal function of the cell membrane, macromolecules and cellular structure are damaged, which, ultimately, leads to cell death (Jiang et al. 2021). The interplay between autophagy and ferroptosis has garnered significant interest in recent time (Park and Chung 2019), offering fresh insights into the intricate regulation of cellular death (Zhou et al. 2020). Several studies have hinted at autophagy acting as a catalyst, particularly under certain circumstances, to augment ferroptosis by disrupting redox equilibrium and fostering ROS-fueled ferroptosis processes. This intricate interplay forms a feedback loop where ROS, the instigators of ferroptosis, also trigger autophagy, which in turn spurs further ROS production, thereby reinforcing ferroptosis (Li et al. 2023; Lin et al. 2023).

Furthermore, there is a growing body of evidence that points to decreased ferroptosis levels as a pivotal mechanism contributing to the development of chemotherapy resistance in tumor cells (Zhang et al. 2022). However, it remains unknown whether NPR1 can influence chemotherapy resistance by affecting ferroptosis levels.

NPR1 positively correlated with cisplatin-resistance and contributed significantly to the development of cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer cells. Mechanistically, NPR1 affected levels of mitophagy and ferroptosis in human cisplatin-resistance GC cells with cisplatin treatment. Specifically, NPR1 inhibited mitophagy-dependent ferroptosis by reducing the ubiquitination-mediated degradation of PARL, which ultimately led to chemoresistance in GC.

Materials and methods

Cells, transfection, plasmids, antibodies, reagents

AGS, AGS/DDP and HGC27, HGC27/DDP (human gastric cancer) cell lines were routinely maintained in RPMI 1640 media and DMEM medium high glucose (BDBIO, China) respectively which was fortified with 10% fetal bovine serum under standard culture conditions (Lonsera, China). For transfection, cells were transfected with PolyJet™ DNA transfection reagent when the cell density reached 80–90% confluence (SignaGen Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD). The HA-Ubiquitin, pLV3-CMV-PARL (human)-CopGFP-Puro, pCMV-GFP-NEDD4L(human)-3 × FLAG-Neo, pCMV-MARCHF8(human)-3 × FLAG-Neo were obtained from MiaoLingBio (Wuhan, China), pcDNA3.1-NPR1(human)-3 × FLAG-C was obtained from Genepharma (Shanghai, China). MG-132 (HY-13259) and Cycloheximide (CHX, HY-12320), Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1, HY-100579), 3-Methyladenine (3-MA, HY-19312), and Mitochondrial division inhibitor 1 (Mdivi-1, HY-15886) were purchased from MedChemExpress. Chloroquine (CQ, CSN25650) was purchased from CSNpharm. Cisplatin (D8810) was purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China). PARL Antibody (F-3) and NPR1 Antibody (G-2) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-PINK1, anti-Parkin, anti-LC3B and anti-p62 Antibodies were obtained from abcam. Anti-GPX4, anti-SLC7A11, anti-FTH, anti-HO-1, anti-COX2, anti-TFRC, anti-VDAC1, anti-TOMM20, anti-MARCH1, anti-DRP1, anti-MFN1, anti-β-actin, iFluor™ 647 & 488 Conjugated Goat anti-rabbit & mouse IgG, HRP Conjugated Goat anti-Rabbit & Mouse IgG Antibodies were obtained from Huabio (Hangzhou, China). Anti-NEDD4L and anti-MARCH8 Antibodies were obtained from Proteintech (Wuhan, China).

The quantitative real-time RT-PCR method (qRT-PCR)

Collect total RNA from the cells of each group according to the instructions of Eastep® Super Total RNA Extraction Kit (LS1040, Promega, China). Then, use RevertAid™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (K1622, Thermo Scientific, USA) to reverse transcribe the obtained cellular RNA into cDNA. Add the cDNA and its corresponding primers and Universal SYBR Green Fast qPCR Mix (4993626, QIAGEN, China)into an 8-tube strip, and use a PCR instrument to detect the expression of each gene.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)

The target cells, which were approximately 30% to 50% confluent, were transfected with 100 nM of siRNA molecules, mixed with 4.5 μl GenMute (SignaGen, SL100568) in a cell culture plate. Cells were cultured for 48 h before plating for protein or RNA isolation and various assays.

si-NPR1-1: 5′- GUGGAACCGAAGCUUUCAATT-3′;

si-NPR1-2: 5′- CCUGUACACUUGCUUUGAUTT-3′;

si-NPR1-3: 5′-GCCUCAAGAAUGGAGUCUATT-3′;

si-NPR1-4: 5′- GGUACUCACUCACCAAUGATT-3′;

si-PARL: 5′-AUUAACAAGUGGUGGAAUA-3′;

si-MARCH1: 5′- GGUAGUGCCUGUACCACAATT-3′;

si-MARCH8: 5′- GGAAGAGACTCAAGGCCTA-3′;

si-NEDD4L: 5′- AACCACAACAAAGUCACAG-3′.

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

An Enhanced Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (BL1055A, Biosharp, China) was used in the cell proliferation assay, wherein 3000 cells/well was seeded in 96 well plates. According to manufacturer’s instruction, we examined the cell proliferation.

Colony formation assay

The GC cells underwent enumeration and were subsequently seeded in triplicate fashion into a 6-well plate, with each well containing precisely 1000 cells. Following a 10-day incubation period, the cells were fixed utilizing 4% paraformaldehyde for a duration of 15 min. Each sample of fixed cells was stained three times with crystal violet solution, ensuring that the staining process was replicated in triplicate for consistency and accuracy. After washing out the dye, we counted colony numbers and compared the results.

Transwell assay

We placed 1 × 10^4 transfected GC cells into the upper chamber of a 24-well transwell insert (8-micron pore size, Corning, USA), utilizing 200 μL of medium devoid of serum. In the lower chamber, 600 µl of complete medium containing 15% FBS was placed. After 24 h of coculture in an incubator, after fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, the cells were subsequently stained using 0.1% crystal violet. Following drying, the stained cells were photographed using a Nikon optical microscope manufactured in Japan. ImageJ software was employed for counting the stained cells.

EdU assay

The transfected cells were subjected to an incubation process with 50 mM EdU reagent in a 37 °C incubator that was supplemented with 5% CO2 for a period of 2 h. Post-incubation, the cells underwent rigorous PBS washes and were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. After additional PBS washes, the GC cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Subsequently, the samples were exposed to an anti-EdU working solution for staining. Following this, the nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst33342 for 10 min and visualized using a Nikon optical microscope from Japan. Subsequently, the enumeration of the stained cells was conducted employing the ImageJ software for analysis.

Analysis of malondialdehyde (MDA), glutathione (GSH), lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) and Fe2+levels

For assessing MDA levels, the MDA Assay Kit (A003-4–1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China) was employed. Centrifuged cell lysates (12,000 g, 4 °C, 10 min) were utilized, and the MDA detection working solution was subsequently added, thoroughly mixed, and heated to 100 °C for 15 min. After cooling to room temperature, the supernatant was centrifuged. Utilizing the standard curve method, the MDA content was quantified by measuring the optical density (OD) at 532 nm. For determining GSH levels, the GSH Assay Kit (A006-2–1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China) was applied. Cell lysates, centrifuged at 12,000 g, 4 °C for 10 min, served as the starting material. The GSH detection working solution was added and thoroughly mixed. Following incubation to room temperature, the solution3 was added. Subsequently, the GSH content was quantified through the standard curve method by measuring the optical density (OD) at 405 nm. To analyze Fe2+ levels, the Fe2+ Assay Kit (E-BC-K772-M, Elabscience, China) was employed. Cell lysates, subjected to centrifugation at 12,000 g, 4 °C for 10 min, were utilized. The supernatant was mixed with an iron reductase reagent and incubated for 40 min. Subsequently, the optical density was measured at 593 nm utilizing a microplate reader for Fe2+ quantification. The LDH-Glo™ Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (J2380, Promega,China) was used to conduct LDH + level assay. Optical density readings at 490 nm were obtained using a microplate reader to analyze the plates.

Analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential

To assess the mitochondrial membrane potential, we employed the Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit with JC-1 (M8650, Solarbio, China). The transfected cells were first rinsed with PBS and then incubated with JC-1 dye at 37 °C for 20 min. Following the incubation period, the cells were promptly washed with PBS. DAPI (BL105A, Biosharp, China) was used to counterstain nuclei. Fluorescence images were captured by an inverted Routine Microscope (ECLIPSE Ts2, Japan).

Detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels

We counted GC cells, planted them in wells, digested them with DCFH-DA ROS probe (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), stained them with the dye, and analyzed the results by flow cytometry. (CytExpert, Beckman, Bremen, Germany).

Western blot assay

Protein content of cells was extracted using Laemmli 2 × Concentrate (S3401; Sigam). By electrophoresis on polyacrylamide gels, proteins were separated from samples and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (NC) (66,485, PALL, USA) and detected with the antibodies. Using Bio-Rad's ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System (Hercules, USA) to capture the protein bands after incubation with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (ECL, Millipore, Burlington, USA).

Co-localization assays

The transfected cells were washed with PBS. Incubate the cells with 100 nM LysoTracker Green (C1047S, Beyotime, China) and 100 nM MitoTracker Red(C1035-50 μg, Beyotime, China) at 37 °C for 1 h to label mitochondria and lysosomes, respectively. After staining, replace the staining solution with fresh medium. Fluorescence detection is performed by Confocal Laser Scanning Microcopy (LSM 800, Zeiss, Germany).

Immunofluorescence (IF) assay

The GC cells were seeded onto a confocal dish. Underwent fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for a period of 15 min, followed by three thorough washes in PBS. To permeabilize the cells, they were exposed to 0.1% Triton X-100 from Solarbio, China, for 10 min. Following this, the cells were blocked in PBS supplemented with 1% Bovine Serum Albumin for 30 min. The cells were incubated with the designated primary antibodies at 4 °C for an overnight period. Subsequently, they were incubated with the secondary antibodies at room temperature for a duration of 1 h. Nuclei counterstaining was achieved using DAPI (acquired from Biosharp, China). Finally, the fluorescence detection was conducted utilizing a Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope, model LSM 800, manufactured by Zeiss in Germany.

Immunoprecipitation (IP)

The cellular material was gathered using an IP lysis buffer which included the protease inhibitor PMSF from Beyotime (product code ST505) and a protease inhibitor cocktail sourced from Biosharp, China (product code P1005). Subsequently, 500 µg of the whole cell lysate protein underwent pre-clearing by being incubated overnight at 4℃ with 1.0 µg of the PARL antibody, utilizing IgG as the control. This mixture was then incubated with Protein A + G Agarose beads (Beyotime, China, product code P2012) for 5 h. Following three washes with chilled PBS buffer, the beads were subjected to boiling in a 2 × SDS loading buffer. Finally, protein expression analysis was carried out using the Western blot assay methodology.

Ubiquitination assay

To the collected cell samples, an adequate volume of cell lysis buffer was introduced. The cell lysate was incubated on ice for a period of time, and then the lysed cells were centrifuged. The supernatant was carefully transferred to a new centrifuge tube, whereupon PARL antibody was introduced to the protein samples. These were then incubated overnight at a temperature of 4 °C. The following day, A/G agarose beads were added to the mixture to sequester the formed antigen–antibody complex. The agarose beads underwent a washing procedure using RIPA buffer. Lastly, the agarose bead-antigen–antibody complex was resuspended in 2 × loading buffer, and the sample was boiled for 5 min to release the antigen, antibody, and beads. Subsequently, the ubiquitination level was detected by Western blot assay using ubiquitin antibody.

LC–MS/MS

Hydrolyze all protein samples from co-IP by protein endonucleases (Trypsin). Subsequently, the hydrolyzed samples were subjected to detection and analysis utilizing Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (nanoLC-QE). Upon completion, the LC–MS/MS data were processed by means of mass spectrometry matching software, specifically MASCOT, to attain qualitative identification information pertaining to the peptide molecules of the target protein.

Nude mouse xenograft animal assay

Male nude mice, aged approximately 4–5 weeks and weighing between 18 and 20 g, were procured from Qinglongshan Animal Breeding Farm located in Jiangning District, Nanjing, China. To explore the in vivo function of NPR1, the mice were randomly assigned to three distinct groups: an NPR1 knockdown group, an overexpression group, and a control group, with an equal number of 5 mice in each. From each group, a quantity of 5 million cells (5 × 10^6) were harvested and subsequently subcutaneously injected into distinct locations within the inguinal area of each mouse. One week following the injection, cisplatin (administered at a dose of 5 mg/kg) dissolved in PBS, or solely PBS, was injected intraperitoneally three times per week. After a period of 5 weeks, the xenograft tumors were extracted. Throughout the study, the tumor volume was regularly monitored on a weekly basis, and after 5 weeks, the tumors were excised and weighed for analysis.

Statistical analysis

All experimental findings are presented in the form of the mean, accompanied by the standard deviation (SD), derived from three independent and replicate experiments. The statistical evaluation of these data was conducted utilizing the GraphPad Prism 6 software package (La Jolla, CA, USA). For comparisons between two groups, Student's t-test was employed to assess the significance of observed differences. For evaluating the statistical significance of biological effects in more complex scenarios, either one-way or two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with multiple comparison tests are utilized. These methods allow for the comprehensive assessment of differences between multiple groups, providing insights into the underlying biological mechanisms and effects. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Results

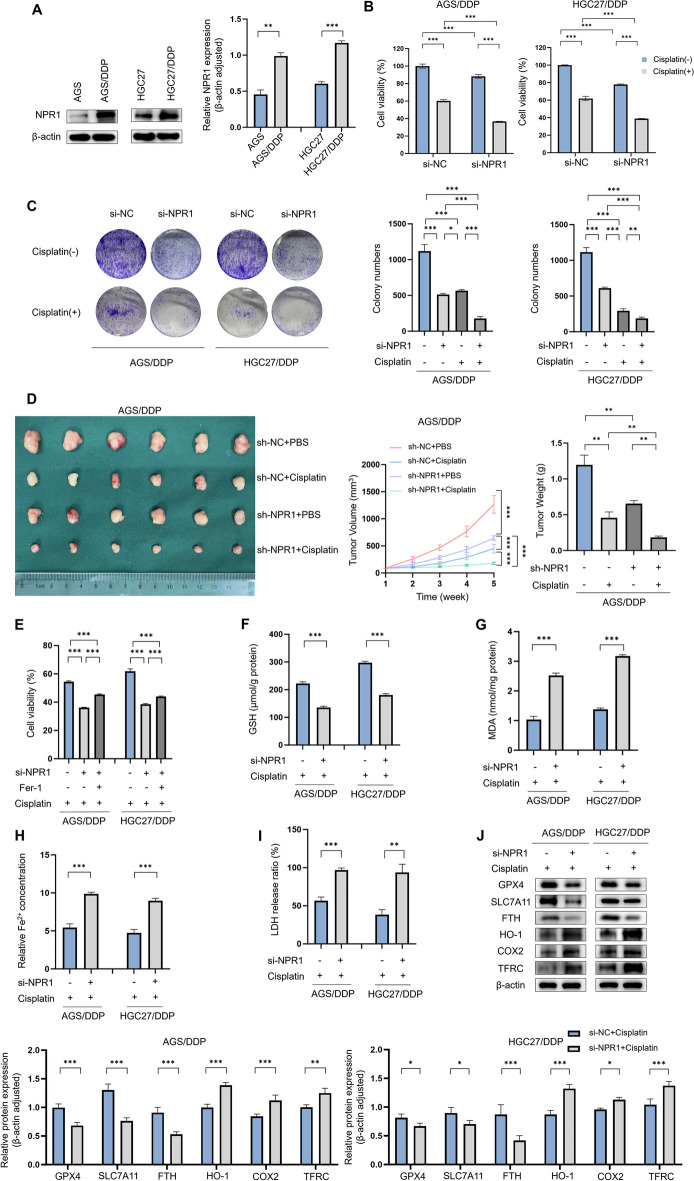

NPR1 affects cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer in vivo and in vitro through a pathway that influences ferroptosis

Western blot analysis demonstrated a substantial elevation in NPR1 expression levels in cisplatin-resistant AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cell lines, when compared to their cisplatin-sensitive counterparts, AGS and HGC27 (Fig. 1A). CCK8 assays revealed that NPR1 knockdown inhibited cisplatin resistance in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP (Fig. 1B). Similarly, colony formation assays revealed reduced cisplatin resistance in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP with NPR1 knockdown (Fig. 1C). In mouse subcutaneous tumor formation assays, NPR1 knockdown resulted in reductions in tumor size, volume and weight (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, the addition of the ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1 reversed the decrease in cisplatin resistance caused by NPR1 knockdown, as determined in CCK8 assays (Fig. 1E). These findings suggest that the effect of NPR1 on GC cell resistance to cisplatin may be related to its influence on ferroptosis in GC cells. Analysis of MDA, GSH, LDH, and Fe2+ levels revealed that after NPR1 was knocked down, the level of ferroptosis in GC cells increased (Fig. 1F, G, H, I). Verification through Western blot analysis of ferroptosis-associated protein levels upheld this observation (Fig. 1J).

Fig. 1.

NPR1 affects Cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer in vivo and vitro through a pathway that influences ferroptosis. A Differential expression of NPR1 in cisplatin-resistant and sensitive cell lines of gastric cancer detected by western blot assay. B-C CCK8 assay detects cisplatin resistance in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cell lines after knockdown of NPR1. Colony formation assay detects cisplatin resistance in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cells lines after knockdown of NPR1. Cisplatin (6 µM). D Mouse subcutaneous tumor formation assay detects cisplatin resistance in AGS/DDP after knockdown of NPR1. Cisplatin (5 mg/kg, three times a week). E CCK8 assay detects cisplatin resistance in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cell lines after knockdown of NPR1 and concomitant addition of Fer-1. F-I Analysis of glutathione (GSH), malondialdehyde (MDA), Fe2+, and lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) levels detect ferroptosis level in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cell lines with knockdown of NPR1. J Expression of ferroptosis-related proteins after knockdown of NPR1 in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cell lines by western blot assay

NPR1-induced ferroptosis occurs in gastric cancer cells via a mitophagy-dependent pathway

Upon NPR1 knockdown in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP, immunofluorescence assays demonstrated reduced intensity of LC3B fluorescence signals along with decreased colocalization of LC3B with MitoTracker (Fig. 2A); similarly, the yellow fluorescence signal, which indicates the spatial overlap between mitochondria and lysosomes, referred to as colocalization, was also decreased after NPR1 knockdown (Fig. 2B). JC-1 assays revealed green fluorescence, indicating a decrease in the mitochondrial membrane potential, in response to NPR1 knockdown (Fig. 2C). Intracellular ROS levels increased upon NPR1 knockdown, as shown by flow cytometric assays (Fig. 2D). Verification through Western blot analysis of mitophagy-associated protein levels upheld this observation (Fig. 2E). After treatment with autophagy inhibitor 3-MA, the expression levels of autophagy markers LC3 and P62 increased, while the expression levels of mitophagy markers PINK1, Parkin, TOM20, and VDAC1 did not show an increase. Therefore, we conclude that NPR1 induced mitophagy is not mediated through autophagy (Fig. 2F). Interestingly, compared with AGS and HGC27, AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP showed significant changes in DRP1 and MFN1 expression after NPR1 knockdown, and changes in these proteins can influence mitochondrial dynamics (Fig. 2G). In addition, the increased levels of ferroptosis caused by NPR1 knockdown were reversed by the mitophagy inhibitor Mdivi-1, as indicated by analysis of MDA, GSH, and Fe2+ levels (Fig. 2H, I, J). These findings hint at a possible association between NPR1's influence on mitophagy levels and its ferroptosis-mediated modulation of cisplatin resistance in GC cells. Our hypothesis was confirmed via Western blot analysis of ferroptosis-related protein levels (Fig. 2K).

Fig. 2.

NPR1 induced ferroptosis occurs in gastric cancer cells via a mitophagy-dependent pathway. A Immunofluorescence assay detect the fluorescent signal intensity of LC3B and the co-localisation of LC3B with Mitotrack after knockdown of NPR1 in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP (scale bar: 5 μm). B Immunofluorescence assay detect the co-localisation of mitochondria and lysosomes after knockdown of NPR1 (scale bar: 5 μm). C JC-1 assay after knockdown of NPR1 (scale bar: 20 μm). D Western blot assay detect the levels of mitophagy-related proteins and ferroptosis-related proteins after treatment with si-NPR1. E Flow cytometric assay detects ROS levels due to knockdown of NPR1 (MFI: Mean Fluorescence Intensity). F Western blot assay detect the expression levels of mitophagy-related proteins after treatment with autophagy inhibitor 3-MA. G The expression of Drp1 and MFN1 after knockdown of si-NPR1 in AGS/DDP, HGC27/DDP and AGS, HGC27 cells. H-J Analysis of MDA, GSH, and Fe2+ levels showed that the elevated levels of ferroptosis due to knockdown of NPR1. K. Western blot assay detect the expression levels of ferroptosis-related proteins after treatment with mitophagy inhibitor Mdivi-1

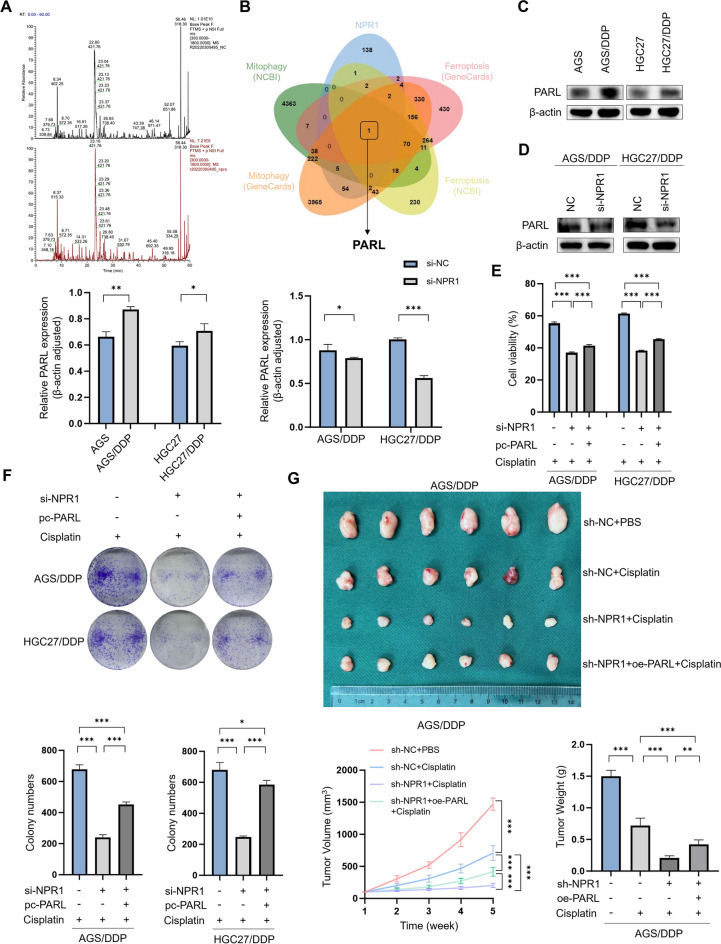

NPR1 functions biologically through PARL

Next, to investigate how NPR1 regulates mitophagy-dependent ferroptosis in GC cells, we conducted IP/MS. After overexpressing NPR1 in the GC cell line AGS, protein samples from the co-IP experiments were analyzed by qualitative and quantitative LC‒MS/MS analysis, which identified proteins that interact with NPR1 (Fig. 3A). By combining the LC–MS/MS results with the mitophagy-related and ferroptosis-related genes in the NCBI and the GENECARDS database, we concluded that NPR1 could bind to PARL (Fig. 3B). Western blot analysis revealed that PARL expression was elevated in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP compared with AGS and HGC27 (Fig. 3C). Moreover, compared with the control, NPR1 knockdown in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP significantly reduced PARL expression (Fig. 3D). These findings indicate that PARL is downstream of NPR1. Further CCK8 assays revealed that NPR1 knockdown inhibited cisplatin resistance in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP and that PARL overexpression reversed the decrease in cisplatin resistance caused by NPR1 knockdown (Fig. 3E). Similarly, colony formation assays revealed that PARL reversed the NPR1 knockdown-mediated decrease in the cisplatin resistance of AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP (Fig. 3F). In subcutaneous tumor formation experiments in mice, the decreases in tumor size, volume, and weight caused by NPR1 knockdown were reversed by PARL overexpression (Fig. 3G). Immunofluorescence assays revealed that the NPR1 knockdown-mediated reductions in the fluorescence signal intensity of LC3B and the colocalization of LC3B with MitoTracker in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP were reversed by PARL overexpression (Fig. 4A); similarly, the yellow fluorescence signal, which indicates the colocalization of mitochondria and lysosomes, was increased by PARL overexpression (Fig. 4B). A JC-1 assay revealed that PARL overexpression reversed the NPR1 knockdown-mediated increase in green fluorescence, an indicator of mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 4C). To deepen our understanding, we executed western blot experiments specifically designed to assess the abundance of proteins implicated in mitophagy (Fig. 4D). In addition, PARL overexpression reversed the increase in intracellular ROS levels caused by NPR1 knockdown, as shown by flow cytometry assays (Fig. 4E). Analysis of MDA, GSH, and Fe2+ levels revealed that PARL overexpression reversed the increase in ferroptosis caused by NPR1 knockdown (Fig. 4F, G, H). To further investigate, western blot assays were conducted, focusing on the analysis of ferroptosis-related protein levels (Fig. 4I).

Fig. 3.

NPR1 promotes Cisplatin resistance through PARL. A-B By overexpressing NPR1 in the GC cell line AGS for IP/MS, which yielded proteins interacting with NPR1 with pull-downs, and by intersecting with the mitophagy and ferroptosis databases of NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene) and GENECARDS (https://www.genecards.org/). C Differential expression of PARL in cisplatin-resistant and sensitive cell lines of gastric cancer detected by western blot assay. D Western blot assay showed that compared with the control groups that knockdown of NPR1 in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cells significantly reduced PARL expression. E CCK8 assay showed that knockdown of NPR1 inhibited cisplatin resistance in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP, and overexpression of PARL reversed the decrease in cisplatin resistance caused by knockdown of NPR1. F Colony formation assays showed that PARL reverted the reduced cisplatin resistance of AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP due to knockdown of NPR1, and overexpression of PARL reversed the decrease in cisplatin resistance caused by knockdown of NPR1. G In subcutaneous tumor formation experiments in mice, the decrease in tumor size, volume, and weight due to knockdown of NPR1 are all reverted by overexpression of PARL

Fig. 4.

NPR1 promotes mitophagy-dependent ferroptosis through PARL. A Immunofluorescence assay detect the fluorescent signal intensity of LC3B and the co-localisation of LC3B with Mitotrack after knockdown of NPR1 and overexpression of PARL in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP (scale bar: 5 μm). B Immunofluorescence assay detect the co-localisation of mitochondria and lysosomes after knockdown of NPR1 and overexpression of PARL (scale bar: 5 μm). C JC-1 assay after knockdown of NPR1 and overexpression of PARL (scale bar: 20 μm). D Western blot assays detect the levels of mitophagy-related proteins after knockdown of NPR1 and overexpression of PARL. E Flow cytometric assay detects ROS levels after knockdown of NPR1 and overexpression of PARL. F–H Analysis of MDA, GSH, and Fe2+ levels showed that the levels of ferroptosis after knockdown of NPR1 and overexpression of PARL. I Western blot assays detect the levels of ferroptosis-related proteins after knockdown of NPR1 and overexpression of PARL

NPR1 affects the ubiquitination of PARL

To elucidate the precise molecular pathway through which NPR1 modulates PARL expression in GC cells, we initially assessed PARL mRNA levels employing qPCR methodology. Our results suggested that NPR1's influence on the transcriptional expression of PARL mRNA was found to be negligible, the transcriptional expression of PARL mRNA remained largely unchanged (Fig. 5A). Then, through co-IP and immunofluorescence colocalization assays, we confirmed the interaction and colocalization of NPR1 and PARL in GC cells (Fig. 5B, C). Next, we explored the mechanism by which NPR1 and PARL interact in greater detail. Since the ability of NPR1 to promote cisplatin resistance requires PARL upregulation, based on our reasoning, we postulated that NPR1 regulates PARL's protein stability. To validate this supposition, we conducted an assessment of PARL's stability in GC cells subjected to cycloheximide (CHX, 200 µg/mL), an inhibitor of protein synthesis, by determining its half-life. NPR1 knockdown significantly shortened the half-life of PARL (Fig. 5D). Subsequently, we evaluated the significance of two fundamental protein degradation pathways: the proteasomal and autophagic mechanisms. The autophagy inhibitor chloroquine (20 µM) had no effect on NPR1-regulated PARL expression. In contrast, treatment of GC cells with the 26S protostome inhibitor MG-132 (10 µM) blocked the NPR1 knockdown-mediated increase in the proteasomal degradation of PARL (Fig. 5E). These findings substantiate the involvement of the NPR1-regulated ubiquitin–proteasome pathway in PARL stabilization. Specifically, when endogenous PARL was immunoprecipitated from cells transfected with HA-Ub, a marked enhancement of ubiquitin signals on PARL was observed in NPR1-siRNA-transfected cells, suggesting that NPR1 elevates PARL levels through modulation of the ubiquitin–proteasome system (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5.

NPR1 affects the ubiquitination process of PARL. A RT-qPCR detects PARL mRNA levels after knockdown of NPR1. B-C Immunofluorescence co-localisation assay and co-IP detect the existence of interaction and co-localisation between NPR1 and PARL in GC cells (scale bar: 5 μm). D Western blot assays examine the half-life of PARL in GC cells treated with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX, 200 µg/mL). E Western blot assays detect effect on NPR1-regulated PARL expression by autophagy inhibitor chloroquine (20 µM) and 26S protostome inhibitor MG-132 (10 µM). F co-IP assay detects the ubiquitin signals of PARL that after endogenous PARL was immunoprecipitated in cells transfected with HA-Ub in NPR1-siRNA cells

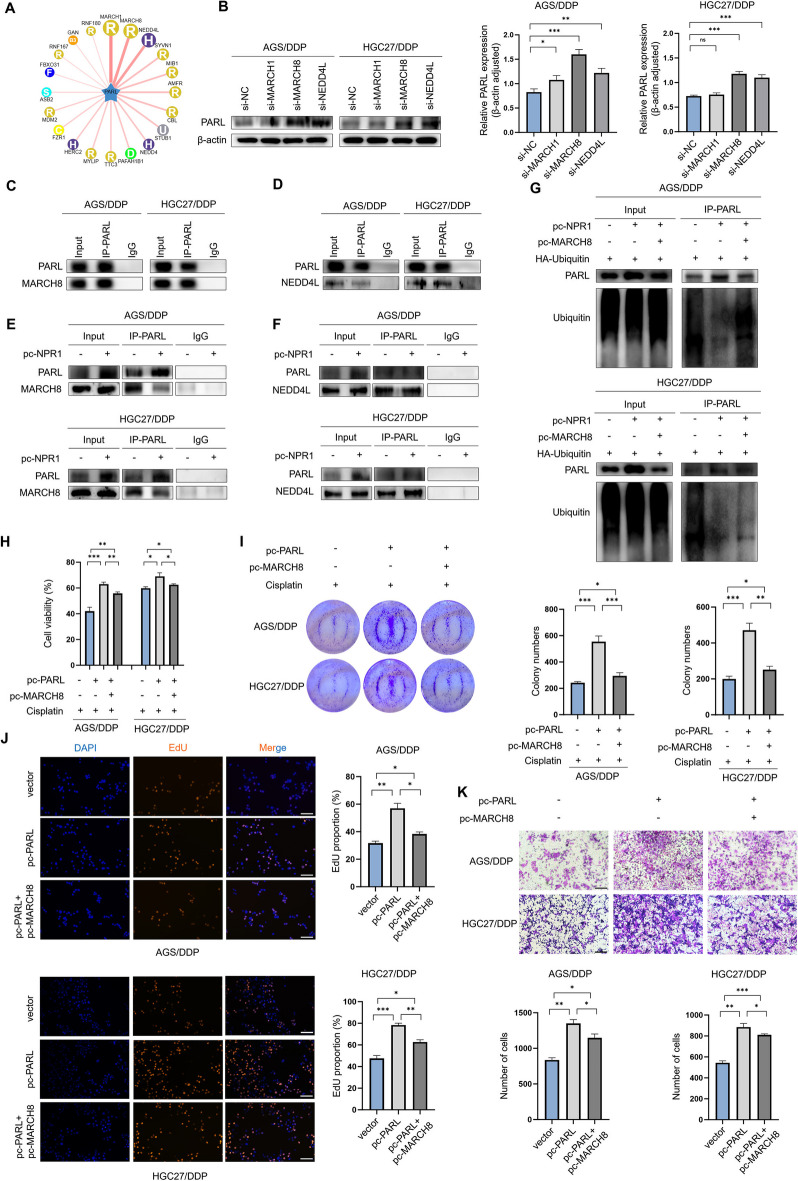

MARCH8 and NEDD4L are E3 ubiquitin ligases for PARL

To uncover the mechanism by which NPR1 slows down the ubiquitin–proteasome mediated degradation of PARL, we embarked on a quest to pinpoint the specific E3 ligase that engages with PARL, utilizing the predictive power of the computational platform UbiBrowser database. According to this database, there are no known E3 ligases that interact with PARL (Fig. 6A). Therefore, we selected the three E3 ligases with the highest score and credibility and transfected siRNAs targeting these three E3 ligases into GC cells, subsequently, the extraction of total cellular protein was carried out, followed by its application in a western blot analysis. Contrary to the siMARCH8 and siNEDD4L groups, which exhibited significant increases, the PARL protein levels in the siMARCH1 group remained relatively unchanged compared to the control group (Fig. 6B). Through a co-IP assay, we confirmed the interactions between MARCH8 and PARL and between NEDD4L and PARL in GC cells (Fig. 6C, D). In conclusion, our results confirmed that MARCH8 and NEDD4L are E3 ligases for PARL.

Fig. 6.

NPR1 affects the process of ubiquitination of PARL by competing with MARCH8 for the binding of PARL. A UbiBrowser (http://ubibrowser.bio-it.cn/ubibrowser) analyze the E3 ligase that interacts with PARL using a computational predictive system. B Western blot analysis revealed the impact on PARL expression after knocking down MARCH1, MARCH8, and NEDD4L in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cells, compared with the control group. C-D co-IP assay confirmed the existence of interaction between MARCH8 and PARL, NEDD4L and PARL in GC cells. E–F co-IP detected E3 ligase that competitively binds to PARL with NPR1, less MARCH8 protein was precipitated with PARL in the overexpression of NPR1 cells compared with the control GC cells. G co-IP assay detects the ubiquitin signals of PARL that after endogenous PARL was immunoprecipitated in cells transfected with HA-Ub in pc-NPR1 and pc-MARCH8. H-I The CCK8 assay and colony formation assay indicates the functions in drug resistance of PARL and its E3 ubiquitin ligase MARCH8. J-K The EdU assay and transwell assay indicates the functions in tumorigenesis of PARL and its E3 ubiquitin ligase MARCH8 (scale bar: 100 μm)

NPR1 affects PARL ubiquitination by competing with MARCH8 for PARL binding

The findings suggest that NPR1 potentially impedes the association of MARCH8 or NEDD4L with PARL. To validate this supposition, a co-IP assay was undertaken. Less MARCH8 protein was precipitated with PARL in NPR1-overexpressing group, compared to the control group (Fig. 6E), and the amount of NEDD4L protein that precipitated with PARL did not differ between NPR1-overexpressing cells and control cells (Fig. 6F). Furthermore, cDNA plasmid transfection to overexpress MARCH8 reversed the NPR1-mediated reduction in PARL ubiquitination (Fig. 6G). Utilizing CCK8 and colony formation assays, we observed that PARL overexpression augmented cisplatin resistance in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cells. Conversely, MARCH8 overexpression mitigated the enhanced cisplatin resistance resulting from PARL knockdown (Fig. 6H, I). Additionally, our EdU and Transwell assays illustrated that PARL overexpression bolstered GC cell proliferation and migration, which were countered by MARCH8 overexpression (Fig. 6J, K). Collectively, these results indicate that NPR1 facilitates PARL stabilization in GC cells by disrupting the interaction between PARL and MARCH8.

Discussion

Globally, gastric cancer (GC) ranks as the most prevalent form of cancer. Age, high salt intake and Helicobacter pylori infection are risk factors for GC (Ajani et al. 2022). In China, a significant proportion of cancer patients are diagnosed at a late stage, necessitating the administration of continuous CDDP chemotherapy as a primary treatment option for advanced cancer. However, CDDP resistance is one of the main obstacles to the clinical efficacy of chemotherapy. Enhancing understanding of the mechanisms underlying CDDP resistance is paramount for optimizing GC prognosis. Multiple pathways contribute to drug resistance, encompassing epigenetic and genetic alterations, as well as alterations in signaling cascades. Furthermore, accumulating evidence underscores the crucial role of reduced ferroptosis in tumor cells' acquisition of chemoresistance (Lugones et al. 2022).

Our previous research revealed that NPR1 can interact with PPARα to promote fatty acid metabolism in GC cells. Recent studies have shown that NPR1 can limit cell proliferation and viability by inducing protective autophagy and the accumulation of ROS (Li et al. 2016) while also affecting cancer resistance through impacts on stemness and FAO. There is an inseparable relationship between FAO and ROS levels. Disrupted FAO in mitochondria can lead to lipid accumulation, excessive ROS production, and oxidative damage (Gao et al. 2022). Nonetheless, the influence of NPR1 on ferroptosis within cancer cells remains unexplored. Numerous mechanisms and signaling pathways, including redox homeostasis, iron therapy, mitochondrial activity, and the metabolism of sugar, lipids, and amino acid, control ferroptosis (Chen et al. 2021). Additionally, there are reports indicating that cancer cells resistant to certain drugs exhibit heightened sensitivity to ferroptosis (Zhao et al. 2022). Increasing evidence suggests that autophagy can lead to ferroptosis under certain conditions (Dai et al. 2020). Autophagy is believed to promote ROS production by disrupting the redox balance (Su et al. 2023). A type of selective autophagy called mitophagy clears cells of damaged or undesirable mitochondria. The relationship between autophagy and iron deficiency anemia has attracted increasing attention, providing a new concept for the regulation of cell death. ROS cause autophagy in ferroptosis, which in turn causes ROS-mediated autophagy, which increases ROS production (Liu et al. 2021), this feedback loop aids in the activation of ferroptosis (Lee et al. 2023). NPR1 is an important receptor for ANP, and it has been demonstrated that the ANP–NPR1 pathway influences inflammation, tumorigenesis, and so on. We found that NPR1 is highly expressed in cisplatin-resistant GC cells. Moreover, our study revealed that NPR1 can reduce ferroptosis, a finding we validated using the ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1. Moreover, in the mechanistic analysis, we found that NPR1 can affect the expression level of ferroptosis-related genes by binding to PARL. Multiple reports have confirmed the close relationships between PARL and mitophagy and ferroptosis. We found that NPR1 can affect the extent of mitochondrial autophagy and ferroptosis in cisplatin-resistant GC cells. Specifically, NPR1 inhibits mitophagy-dependent ferroptosis by competing with the E3 ligase MARCH8 for binding to PARL, reducing its ubiquitination-mediated degradation and ultimately leading to chemotherapy resistance in GC.

As mentioned above, NPR1 can affect the expression level of ferroptosis-related genes by binding to PARL. Within the inner mitochondrial membrane, PARL belongs to the rhomboid family of intramembrane serine proteases, marking it as a vital component within this enzyme group. The encoded protein has been investigated in a number of malignancies and controls both apoptosis and mitochondrial remodeling by modifying the proteolytic cleavage of substrate proteins (Lysyk et al. 2020). Research has demonstrated that PARL is a crucial component of mitophagy, and multiple reports have highlighted the close relationship between PARL and the PINK/PARKIN pathway. Additionally, according to a recent study, ferroptosis and halted spermatogenesis are the results of mitochondrial abnormalities brought on by PARL deficiency (Radaelli 2023). Another study found that via stabilizing PARL-induced PINK1 degradation, STOML2 limits mitophagy and boosts chemosensitivity in pancreatic cancer (Qin et al. 2023). However, there have been no reports on the mechanism by which PARL impacts cisplatin resistance in GC. Therefore, after determining through IP-MS that PARL is downstream of and interacts with NPR1, using western blot analysis, we were able to identify the distinct expression of PARL in GC cell lines that were cisplatin-sensitive and cisplatin-resistant. The results showed that PARL expression increased in cisplatin-resistant cell lines, and we demonstrated via rescue experiments that NPR1 promotes cisplatin resistance in GC cells through PARL. As a key contributor to malignant biological behaviors such as ferroptosis and mitophagy, continued research on PARL is expected in order to investigate this potential molecular target for treating chemoresistance in cancer cells.

MARCH8 is a constituent of the MARCH family of E3 ubiquitin ligases, characterized by their membrane-association and the presence of RING-CH-type zinc fingers, conferring unique biochemical functions. Contemporary investigations into cisplatin resistance in GC have illuminated JWA's regulatory role in TRAIL-induced apoptosis, specifically via MARCH8-facilitated DR4 ubiquitination, in cisplatin-resistant GC cells (Wang et al. 2017). The NEDD4 family of E3 ubiquitin ligases, characterized by their HECT (homologous to E6-AP C-terminus) domain, mediates the ubiquitination of various targets and is vital for epithelial sodium transport. This process is governed by the NEDD4L gene, which regulates the cell surface expression of the epithelial sodium channel ENaC. Research has demonstrated that NEDD4L may work as a tumor suppressor in a variety of malignancies, including GC. It also suppresses bladder cancer cells' migration, invasion, and cisplatin resistance while promoting their apoptosis through the p62/Keap1/Nrf2 pathway (Wu et al. 2023). To date, there have been no reports on the molecular mechanism by which E3 ubiquitin ligases regulate PARL. Therefore, we selected the three E3 ubiquitin ligases with the highest interaction scores with PARL from the UBIBROWSER database for further analysis. When MARCH1 was knocked down, there was an absence of notable alterations in PARL protein levels, whereas knocking down the two E3 ligases MARCH8 and NEDD4L significantly increased PARL protein levels. Through co-IP experiments, we confirmed the interactions between MARCH8 and PARL and between NEDD4L and PARL in GC cells. We hypothesized that NPR1 affects the ubiquitination of PARL through MARCH8 and NEDD4L. Therefore, we conducted further experiments to verify these findings and found that less MARCH8 protein precipitated with PARL in NPR1-overexpressing cells than in control GC cells, suggesting that NPR1 can hinder the binding of MARCH8 to PARL. A two-edged sword in the development of tumors, variations in PARL expression are crucial. Therefore, we believe that NEDD4L may affect the level of mitochondrial autophagy in cells through PARL, thereby affecting the malignant progression of tumors. Overall, MARCH8 and NEDD4L, as E3 ligases for important functional proteins such as PARL, should be further studied using multiomics approaches to fully elucidate their mechanisms with PARL, providing robust evidence to solve related scientific problems such as chemoresistance.

In summary, we validated the chemical resistance induced by NPR1 in GC cells by comparison of sensitive and resistant GC cell lines. Moreover, we discovered an interaction between NPR1 and PARL. Studies have shown that PARL is related to mitophagy and ferroptosis. NPR1 competitively binds to MARCH8 to protect PARL from proteasome-mediated degradation, thereby inhibiting mitophagy-dependent ferroptosis. Our understanding of NPR1's function in the management and prognosis of GC will improve as a result of these findings. According to the current research, NPR1 emerges as a potential therapeutic target for the clinical prevention and management strategies aimed at GC.

Conclusion

We confirmed the important role of NPR1 in cisplatin resistance in GC cells. Mechanistically, we found that NPR1 was highly expressed in cisplatin-resistant GC cells and it affects the levels of mitophagy and ferroptosis. Specifically, NPR1 inhibits mitophagy-dependent ferroptosis by reducing the ubiquitination-mediated degradation of PARL and promotes PARL stabilization by disrupting the PARL-MARCH8 complex, ultimately leading to chemoresistance in GC cells.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Fig. S1 A. The drug sensitivity of NPR1 was calculated using the information from the GDSC (Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer) drug sensitivity database (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/). Computer molecular docking simulations is conducted of cisplatin with NPR1. B. The expression of NPR1 was knocked down using four siRNAs in AGS HGC27 AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cells. C. The drug sensitivity PARL was calculated using the information from the GDSC (Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer) drug sensitivity database (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/). Computer molecular docking simulations is conducted of cisplatin with PARL. D. The expression of PARL was increasing after overexpressing PARL in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cells. E-G. Select the three highest scoring E3 ligases and transfected the siRNAs of the corresponding three E3 ligases in GC cells, after which total cellular proteins were extracted and subjected to western blot assay. H. The expression of NPR1 was increasing after overexpressing NPR1 in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cells. I. The expression of MARCH8 was increasing after overexpressing MARCH8 in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cells (JPG 1526 KB)

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for the help of Figdraw (Figdraw.com) and the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82372707, 81902515); Natural Science Research Project of Higher Education in Anhui Province (2023AH051771, KJ2021A0857, 2023AH040254); Anhui Provincial Health Commission Provincial Financial Key Projects(AHWJ2023A10126); Wuhu Science and Technology Program (2022cg27).

Author contributions

CWW, SW, TH and XRX: Conceptualization, Figure preparation, & Writing—Original draft preparation. XXH, LMW, LX and YBX: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—Reviewing & editing. LSX, JWW and YFH: Writing—Reviewing & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82372707, 81902515); Natural Science Research Project of Higher Education in Anhui Province (2023AH051771, KJ2021A0857, 2023AH040254); Anhui Provincial Health Commission Provincial Financial Key Projects (AHWJ2023A10126); Wuhu Science and Technology Program (2022cg27).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments are approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Wannan Medical College. (Approval no. WNMC-AWE-2024341).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chengwei Wu, Song Wang, Tao Huang and Xinran Xi contributed equally to this work.

References

- Ajani JA, et al. Gastric Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20:167–92. 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao T, et al. NPRA promotes fatty acid metabolism and proliferation of gastric cancer cells by binding to PPARα. Transl Oncol. 2023;35:101734. 10.1016/j.tranon.2023.101734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G, Tang D. Broadening horizons: the role of ferroptosis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:280–96. 10.1038/s41571-020-00462-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, et al. MSC-NPRA loop drives fatty acid oxidation to promote stemness and chemoresistance of gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2023;565:216235. 10.1016/j.canlet.2023.216235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai E, et al. Autophagy-dependent ferroptosis drives tumor-associated macrophage polarization via release and uptake of oncogenic KRAS protein. Autophagy. 2020;16:2069–83. 10.1080/15548627.2020.1714209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, et al. Self-amplified ROS production from fatty acid oxidation enhanced tumor immunotherapy by atorvastatin/PD-L1 siRNA lipopeptide nanoplexes. Biomaterials. 2022;291:121902. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan WL, He Y, Xu RH. Gastric cancer treatment: recent progress and future perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. 2023;16:57. 10.1186/s13045-023-01451-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Stockwell BR, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:266–82. 10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, et al. Autophagy mediates an amplification loop during ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14:464. 10.1038/s41419-023-05978-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, et al. Natriuretic peptide receptor A inhibition suppresses gastric cancer development through reactive oxygen species-mediated G2/M cell cycle arrest and cell death. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;99:593–607. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, et al. Natriuretic peptide receptor a promotes gastric malignancy through angiogenesis process. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:968. 10.1038/s41419-021-04266-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, et al. The crosstalk between ferroptosis and mitochondrial dynamic regulatory networks. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:2756–71. 10.7150/ijbs.83348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, et al. Mitophagy alleviates cisplatin-induced renal tubular epithelial cell ferroptosis through ROS/HO-1/GPX4 axis. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:1192–210. 10.7150/ijbs.80775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, et al. Ferroptosis inducer erastin sensitizes NSCLC cells to celastrol through activation of the ROS-mitochondrial fission-mitophagy axis. Mol Oncol. 2021;15:2084–105. 10.1002/1878-0261.12936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López MJ, et al. Characteristics of gastric cancer around the world. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2023;181:103841. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugones Y, Loren P, Salazar LA. Cisplatin Resistance: Genetic and Epigenetic Factors Involved. Biomolecules. 2022;12. 10.3390/biom12101365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lysyk L, Brassard R, Touret N, Lemieux MJ. PARL Protease: A Glimpse at Intramembrane Proteolysis in the Inner Mitochondrial Membrane. J Mol Biol. 2020;432:5052–62. 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E, Chung SW. ROS-mediated autophagy increases intracellular iron levels and ferroptosis by ferritin and transferrin receptor regulation. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:822. 10.1038/s41419-019-2064-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picca A, Faitg J, Auwerx J, Ferrucci L, D’Amico D. Mitophagy in human health, ageing and disease. Nat Metab. 2023;5:2047–61. 10.1038/s42255-023-00930-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C, et al. STOML2 restricts mitophagy and increases chemosensitivity in pancreatic cancer through stabilizing PARL-induced PINK1 degradation. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14:191. 10.1038/s41419-023-05711-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radaelli E et al. Mitochondrial defects caused by PARL deficiency lead to arrested spermatogenesis and ferroptosis. Elife. 2023;12. 10.7554/eLife.84710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Su L, Zhang J, Gomez H, Kellum JA, Peng Z. Mitochondria ROS and mitophagy in acute kidney injury. Autophagy. 2023;19:401–14. 10.1080/15548627.2022.2084862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, et al. JWA regulates TRAIL-induced apoptosis via MARCH8-mediated DR4 ubiquitination in cisplatin-resistant gastric cancer cells. Oncogenesis. 2017;6:e353. 10.1038/oncsis.2017.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, et al. NEDD4L inhibits migration, invasion, cisplatin resistance and promotes apoptosis of bladder cancer cells by inactivating the p62/Keap1/Nrf2 pathway. Environ Toxicol. 2023;38:1678–89. 10.1002/tox.23796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng S, et al. Inhibition of Fatty Acid Translocase (FAT/CD36) Palmitoylation Enhances Hepatic Fatty Acid β-Oxidation by Increasing Its Localization to Mitochondria and Interaction with Long-Chain Acyl-CoA Synthetase 1. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2022;36:1081–100. 10.1089/ars.2021.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Liu X, Jin S, Chen Y, Guo R. Ferroptosis in cancer therapy: a novel approach to reversing drug resistance. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:47. 10.1186/s12943-022-01530-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, et al. Ferroptosis in cancer and cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2022;42:88–116. 10.1002/cac2.12250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B, et al. Ferroptosis is a type of autophagy-dependent cell death. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;66:89–100. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 Fig. S1 A. The drug sensitivity of NPR1 was calculated using the information from the GDSC (Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer) drug sensitivity database (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/). Computer molecular docking simulations is conducted of cisplatin with NPR1. B. The expression of NPR1 was knocked down using four siRNAs in AGS HGC27 AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cells. C. The drug sensitivity PARL was calculated using the information from the GDSC (Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer) drug sensitivity database (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/). Computer molecular docking simulations is conducted of cisplatin with PARL. D. The expression of PARL was increasing after overexpressing PARL in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cells. E-G. Select the three highest scoring E3 ligases and transfected the siRNAs of the corresponding three E3 ligases in GC cells, after which total cellular proteins were extracted and subjected to western blot assay. H. The expression of NPR1 was increasing after overexpressing NPR1 in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cells. I. The expression of MARCH8 was increasing after overexpressing MARCH8 in AGS/DDP and HGC27/DDP cells (JPG 1526 KB)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.