Abstract

Considerable progress has been made in the genomics of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) since the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension, with the identification of rare variants in several novel genes, as well as common variants that confer a modest increase in PAH risk. Gene and variant curation by an expert panel now provides a robust framework for knowing which genes to test and how to interpret variants in clinical practice. We recommend that genetic testing be offered to specific subgroups of symptomatic patients with PAH, and to children with certain types of group 3 pulmonary hypertension (PH). Testing of asymptomatic family members and the use of genetics in reproductive decision-making require the involvement of genetics experts. Large cohorts of PAH patients with biospecimens now exist and extension to non-group 1 PH has begun. However, these cohorts are largely of European origin; greater diversity will be essential to characterise the full extent of genomic variation contributing to PH risk and treatment responses. Other types of omics data are also being incorporated. Furthermore, to advance gene- and pathway-specific care and targeted therapies, gene-specific registries will be essential to support patients and their families and to lay the foundation for genetically informed clinical trials. This will require international outreach and collaboration between patients/families, clinicians and researchers. Ultimately, harmonisation of patient-derived biospecimens, clinical and omic information, and analytic approaches will advance the field.

Shareable abstract

We summarise the conclusions and recommendations of the 7th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension genetics and genomics task force, highlighting progress over time, new recommendations on genes and genetic testing, and key needs to advance the PH field. https://bit.ly/4djRvZP

Introduction

For >20 years, advances in genetic contributions to pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) have contributed to our understanding of the underlying pathobiology of PAH. Since the reports in 2000 that heterozygous germline variants in the gene bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 (BMPR2) cause PAH in many familial PAH cases, rare variants (mutations) in >20 genes have been associated with PAH. While many of these genes contribute to overlapping molecular mechanisms and pathways, more recent discoveries highlight novel contributions to the pathogenesis of PAH. In addition, since the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension (WSPH), unique contributions to our genetic understanding have been made applying genomic sequencing to large cohorts of well-phenotyped PAH patients. Among recent discoveries is the recognition that PAH diagnosed during childhood has a higher frequency of pathogenic variants across a wider diversity of genes driving heritable disease, as well as a deeper understanding of the risk of PAH among those with heterozygous pathogenic variants in PAH-associated genes.

Technological advances now support genomic studies to incorporate variations in all genes and their interactions. This will provide insight into the combined influence of multiple genetic variants upon vascular growth and development, inflammation, response to injury and cellular homeostasis. However, substantial opportunities and work remain. Key needs include, but are not limited to, the development and incorporation of large diverse cohorts to power equitable approaches to discovery and progress to all participants around the world and across the lifespan. Genetic research drives discovery of pathobiology and provides targets for therapy. In addition, the direct clinical applications of genomic studies are 1) to provide information about prognosis and therapeutic response, as well as tailored surveillance information for conditions beyond PAH relevant to a subset of genes; 2) risk prediction for asymptomatic individuals including family members; and 3) anticipation of potential future opportunities for genetically based therapy. In this document, we review strategies to address these needs, with a recognition that PAH is a disease that impacts people of all ages, and identification of individuals at increased risk of PAH can facilitate early diagnosis and early initiation of treatment to improve clinical outcomes.

Methods of genetic therapy are rapidly evolving and include antisense oligonucleotides, gene addition and gene editing. Several of these therapies are now approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency and include genetic therapies for diseases such as spinal muscular atrophy and sickle cell disease [1]. Genetic therapies for cardiomyopathies are in clinical trials, and multiple genetic therapeutic approaches are in development for cystic fibrosis [2]. Methods of genetic delivery to the lung are being developed for inhalation, and targeting the pulmonary vasculature is possible with right heart catheterisation. Given these opportunities for genetic therapy that are rapidly evolving, it is critical to prepare and to be ready to seize on these advances for patients with heritable PAH. To prepare for these future opportunities, it will be critical to catalogue the genes causing PAH, their mechanism of action, the relevant cell type of action, identify patients with these genetic conditions, and understand the natural history of each genetic condition and the window of therapeutic treatment. It is likely that early identification and treatment of individuals at risk and in early stages of disease will be the ones most effectively treated which will be a paradigm shift for the field. If only end-stage patients are identified and available to test efficacy of these therapies, these patients may be beyond the window of therapeutic efficacy with irreversible changes to the pulmonary vasculature, and they may not respond in clinical trials. We may then miss an opportunity to effectively support the next generation of patients at high risk of PAH.

Genetic and genomic approaches in complex diseases

The foundational discoveries of the genetic underpinning of PAH in patients and families impacted by familial and/or heritable PAH occurred initially with positional cloning of single genes harbouring rare genetic variants (e.g. the discovery of BMPR2 in PAH) [3, 4]. Many genes in the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β pathway were considered and tested as candidate genes before we were able to interrogate the genome comprehensively. More recently, genomic sequencing studies of patients and families and large cohorts of well-phenotyped participants supported unbiased, rigorous gene discovery and validation. Discussion of the mechanism of these genes is summarised in the report by the task force on pathology and pathobiology of PH [5]. Related efforts to identify the genomic and nongenomic factors which modify disease penetrance and contribute to variable expressivity of the PAH phenotype continue, but are currently underpowered.

To systematically assess the level of evidence supporting PAH gene disease association to inform which genes should be included in genetic testing panels of PAH, an international group of PAH geneticists followed the standardised Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) semi-quantitative scoring system based on genetic and experimental evidence (https://search.clinicalgenome.org/kb/genes/HGNC:8582) [6]. This ClinGen framework is standardised and provides consistency across the global community across genetic conditions. Replication of results across studies and sufficient time for results to potentially be refuted are included within the system of assessment. The amount of genetic and experimental evidence for a particular gene varied based upon the year in which the gene was first published to be associated with PAH and based upon the frequency of PAH cases with rare predicted deleterious variants in the genes. 12 genes (BMPR2, ACVRL1, ATP13A3, CAV1, EIF2AK4, ENG, GDF2, KCNK3, KDR, SMAD9, SOX17 and TBX4) were classified as having definitive evidence, and three genes (ABCC8, GGCX and TET2) with moderate evidence. Six genes (AQP1, BMP10, FBLN2, KLF2, KLK1 and PDGFD) were classified as having limited evidence. The genes with moderate or limited evidence have largely been described within the past 5 years, and additional evidence may emerge over time to increase the confidence of their association with PAH. TOPBP1 was classified as having no known PAH relationship. Five genes (BMPR1A, BMPR1B, NOTCH3, SMAD1 and SMAD4) were disputed due to a paucity of genetic evidence over time, with most of the evidence being provided by experimental data rather than human genetic data (table 1). These disputed genes were identified during the era of candidate gene assessment before unbiased genome-wide methods were possible, and these disputed genes should not be included in genetic testing panels. Each gene is scheduled to be reassessed every 3 years as new evidence evolves.

TABLE 1.

Strength of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)–gene relationships for genes implicated in PAH

| Gene name | Type of PAH | Mode of inheritance | Genetic evidence | Variant type score | Experimental evidence | Evidence type scored | Total score | >3 years? | Classification | Tissue/cell expression | Molecular mechanism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP13A3 | ATPase 13A3 | Isolated | AD/AR | 12 | pLoF | 1 | F/expression; FA/non-patient | 13 | Yes 2018 |

Definitive | PASMC, PAEC, BOEC | Unknown |

| BMPR2 | Bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 | Isolated | AD | 12 | pLoF | 6 | F/expression, biochemical, interaction; FA/patient; M/non-human; R/non-human | 18 | Yes 2000 |

Definitive | PASMC, PAEC | Haploinsufficiency |

| CAV1 | Caveolin 1 | Isolated | AD | 6 | pLoF, missense | 6 | F/biochemical; FA/patient; M/non-human; R/non-human | 12 | Yes 2012 |

Definitive | Lung EC | Dominant negative |

| GDF2 | Growth differentiation factor 2 | Isolated | AD | 12 | pLoF, missense | 6 | F/expression, biochemical, interaction; FA/patient, non-patient; M/cell culture | 18 | Yes 2016 |

Definitive | HMVEC/PAEC/ hepatic stellate cells | Haploinsufficiency |

| KCNK3 | Potassium two pore domain channel subfamily K member 3 | Isolated | AD | 7 | Missense | 5 | F/expression; FA/patient; M/non-human | 12 | Yes 2013 |

Definitive | Lung, PA, PASMC | LoF |

| KDR | Kinase insert domain receptor | Isolated | AD | 6.5 | pLoF | 6 | F/expression; M/non-human | 12.5 | Yes 2018 |

Definitive | PAEC | Haploinsufficiency |

| SMAD9 | Smad family member 9 | Isolated | AD | 9.6 | pLoF, missense | 4.5 | F/biochemical, interaction; FA/patient, non-patient; R/patient cells | 14.1 | Yes 2009 |

Definitive | PAEC, PASMC | LoF |

| SOX17 | SRY-box transcription factor 17 | Isolated | AD | 11.8 | pLoF, missense | 1.5 | F/expression; FA/non-patient | 13.3 | Yes 2018 |

Definitive | PAEC, PAH plexiform lesions | Haploinsufficiency |

| ABCC8 | ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 8 | Isolated | AD | 9.0 | pLoF, missense | 1.0 | F/expression | 10 | Yes 2018 |

Moderate | Lung, PA | LoF |

| GGCX | Gamma glutamyl carboxylase | Isolated | AD | 8.8 | pLoF, missense | 0.5 | F/expression | 9.3 | Yes 2019 |

Moderate | Lung | Unknown |

| TET2 | Tet- methylcytosine-dioxygenase-2 | Isolated | AD | 4.6 | pLoF, missense | 3.5 | F/expression, biochemical; M/non-human | 8.1 | No 2020 |

Moderate | Lung | LoF |

| AQP1 | Aquaporin 1 | Isolated | AD | 3.3 | Missense | 0.5 | F/expression | 3.8 | Yes 2018 |

Limited | PASMC, PAEC, BOEC | NA |

| BMP10 | Bone morphogenetic protein 10 | Isolated | AD | 1.9 | pLoF, missense | 1.1 | F/expression, biochemical, interaction | 3.0 | Yes 2019 |

Limited | Plasma, right atrium | Haploinsufficiency |

| FBLN2 | Fibulin 2 | Isolated | AD | 2.0 | Missense | 0.5 | F/expression | 2.5 | No 2021 |

Limited | Heart, aorta coronaries, basement membrane | Unknown (GoF?) |

| KLF2 | Krüppel-like factor 2 | Isolated | AD | 0.5 | Missense | 3.0 | F/expression, interaction; FA/patient | 3.5 | Yes 2017 |

Limited | Lung, vasculature | NA |

| KLK1 | Tissue kallikrein | Isolated | AD | 5.2 | pLoF, missense | 0.5 | F/expression | 5.7 | Yes 2019 |

Limited | Lung, vasculature | Unknown (haploinsufficiency and/or LoF?) |

| PDGFD | Platelet derived growth factor D | Isolated | AD | 2.1 | 2.0 case–control data+0.1 missense | 0.5 | F/expression | 2.6 | No 2021 |

Limited | Lung, vasculature, mesenchyme | Unknown (GOF?) |

| TOPBP1 | DNA topoisomerase II binding protein 1 | Isolated | NA | 0 | None | 1.0 | F/expression; FA/non-patient | 1.0 | NA | No known disease relationship | Lung, PAEC | NA |

| BMPR1A | Bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A | Isolated | NA | 0 | Missense | 2 | F/expression, biochemical, interaction | 2.0 | Yes 2018 |

Disputed | PASMC | NA |

| BMPR1B | Bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1B | Isolated | NA | 0 | Missense | 2 | F/expression, biochemical, interaction | 2.0 | Yes 2012 |

Disputed | PASMC | NA |

| NOTCH3 | Notch receptor 3 | Isolated | NA | 0 | Missense | 2.0 | F/expression, biochemical; FA/non-patient | 2.0 | Yes 2014 |

Disputed | Lung, PASMC | NA |

| SMAD1 | Smad family member 1 | Isolated | NA | 0 | Missense | 3.0 | F/biochemical; M/non-human | 3.0 | Yes 2011 |

Disputed | PAEC, PASMC | NA |

| SMAD4 | Smad family member 4 | Isolated | NA | 0 | Missense, other | 1.0 | F/biochemical | 1.0 | Yes 2011 |

Disputed | PAEC, PASMC | NA |

| ACVRL1 | Activin receptor like 1 | HHT | AD | 12 | pLoF, missense | 6 | F/expression, biochemical, interaction; M/non-human | 16 | Yes 2001 |

Definitive | Lung, PAEC | Haploinsufficiency |

| ENG | Endoglin | HHT | AD | 10.1 | pLoF, missense, other | 3.5 | F/expression, interaction; M/nonhuman | 13.6 | Yes 2003 |

Definitive | Lung, PAEC | Haploinsufficiency |

| TBX4 | T-box transcription factor 4 | TBX4 syndrome | AD | 12 | pLoF | 1 | F/expression; FA/patient, non-patient | 13 | Yes 2013 |

Definitive | Lung mesenchyme | Haploinsufficiency |

| EIF2AK4 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α kinase 4 | PVOD/PCH | AR | 12 | pLoF, missense | 0.5 | F/expression | 12.5 | Yes 2014 |

Definitive | Lung, PASMCs | LoF |

AD: autosomal dominant; AR: autosomal recessive; pLoF: predicted loss of function (nonsense, frameshift and canonical splice variants); F: function (relevant expression, biochemical function, protein interaction); FA: functional alteration (in patient or non-patient cells); PASMC: pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell; PAEC: pulmonary artery endothelial cell; BOEC: blood outgrowth endothelial cell; M: model (human or non-human, cell culture/human or non-human); R: rescue (human or non-human, cell culture/human or non-human); EC: endothelial cell; HMVEC: human lung microvascular endothelial cell; PA: pulmonary artery; NA: not applicable; GoF: gain of function; LoF: loss of function; HHT: hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia; PVOD: pulmonary veno-occlusive disease; PCH: pulmonary capillary haemangiomatosis.

A key area of knowledge for pulmonary hypertension (PH) clinicians is interpretation of clinically obtained genetic test results. Variant classification ideally follows guidelines proposed by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) [7] or a similar approach [8]. In addition, online resources exist such as ClinGen to assist with interpretation of genetic results (https://clinicalgenome.org/working-groups/sequence-variant-interpretation/). The five ACMG-recommended variant classification categories (pathogenic, likely pathogenic, uncertain significance, likely benign and benign) are widely used by clinical genetic laboratories approved to return results. Only pathogenic/likely pathogenic results are diagnostic and should be acted upon clinically. Variants of uncertain significance (VUS) are not diagnostic and require further assessment, such as segregation studies within the family of the genetic variant and PAH. If the VUS is found to be de novo upon parental testing, the variant may be reclassified to likely pathogenic.

Burden of rare variants associated with PAH is not equal across the lifespan

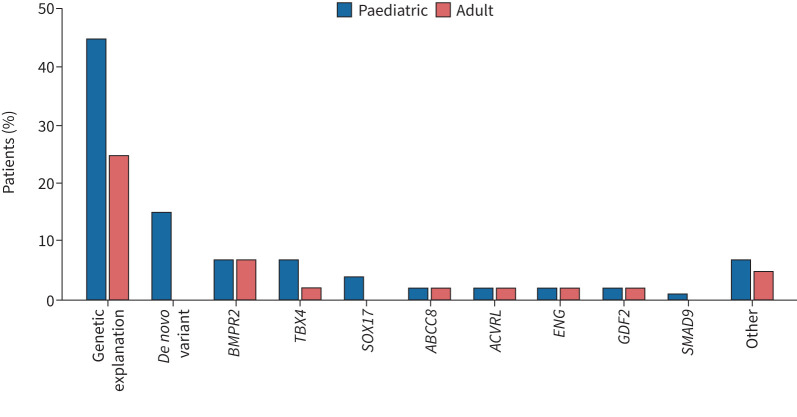

PAH is a disease which can present at any age, with disease onset ranging from infancy to late adulthood. While there are some phenotypic differences between paediatric-onset and adult-onset PAH (e.g. the pre-pubertal male:female ratio approximates 1:1, unlike the skew toward higher prevalence among biological female sex post-puberty; paediatric-onset cases have worse haemodynamics at diagnosis). A striking finding is the higher burden of germline rare variants among those diagnosed during childhood (figure 1). Perhaps this is not surprising, given the enrichment of genes relevant to cardiopulmonary development implicated in PAH, such as BMPR2 and other members of the TGF-β pathway, as well as transcription factors such as TBX4 and SOX17. Initial work by Zhu et al. [9] documented roughly two-fold enrichment of deleterious de novo variants among paediatric-onset cases previously classified as idiopathic PAH (IPAH). A recent multinational study found nearly 2.5-fold enrichment compared to the expected rate using 124 trios of paediatric-onset PAH probands, estimating that ∼ 15% of all paediatric-onset cases are attributable to de novo variants [10]. Most of the de novo variants influence developmentally relevant processes including, but not limited to, previously discovered genes such as BMPR2, TBX4 and SOX17. However, larger cohorts of paediatric- and adult-onset PAH, representing PAH of all types, are needed to verify and expand the concept that paediatric-onset PAH is particularly enriched by rare (and perhaps less rare) variations in developmentally important and other genes.

FIGURE 1.

Approximate burden of rare variants (mutations) in genes associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) among patients diagnosed at paediatric or adult age. Fewer paediatric than adult cases lack genetic explanation. Among paediatric cases, ∼15% have an identifiable de novo variant in a gene not represented in the figure nor inherited from a biological parent while few to no adult cases have this finding. The “other” category includes genes classified (table 1) as definitive for PAH as well as those with less definitive evidence. BMPR2: bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2; TBX4: T-box transcription factor 4; SOX17: SRY-box transcription factor 17; ABCC8: ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 8; ACVRL: activin receptor like 1; ENG: endoglin; GDF2: growth differentiation factor 2; SMAD9: Smad family member 9.

Genetic testing in clinical care

Survey data from participants in the UK RAPID-PAH study demonstrate that 74% of PAH patients were interested in genetic testing [11]. When surveyed at the 7th WSPH, 66% of providers voted that the most useful role of genetic testing is to inform family members and/or contribute to family planning decisions.

The utility of genetic testing in PH is summarised in table 2. Genetic testing should be offered to all adult patients with group 1 PH subtypes of IPAH, heritable PAH (HPAH), congenital heart disease, pulmonary capillary haemangiomatosis, and drugs and toxins (table 3). In adults, a genetic test composed of a panel of genes with validated association with PAH is recommended (ClinGen definitive or moderate evidence). If no mutation is identified in an adult with HPAH or with associated congenital heart disease, exome/genome sequencing is appropriate.

TABLE 2.

Utility of genetic testing in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)

| Prognostic information | Provides more accurate prognostic information |

| Identifies conditions with associated features (TBX4, ENG, ACVLR1) to tailor care | |

| Personalised treatment | More precise classification and tailored treatments based on genetic mutations (e.g. EIF2AK4) |

| Familial risk assessment | Clarifies risk for family members (both increased and not increased risk) |

| Informs family planning and monitoring strategies | |

| Early diagnosis of asymptomatic family members | Identifies heritable forms of PAH |

| Enables early detection and intervention, potentially improving disease outcomes | |

| Research and clinical trials | Enhances understanding of PAH pathogenesis for future genetic therapies |

| May allow for patient stratification of responders and adverse outcomes in clinical trials |

TABLE 3.

Recommendations for genetic testing in pulmonary hypertension

| Symptomatic patients | Asymptomatic family members | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paediatric | Adult | Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in proband known | Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in proband unknown | |

| Types of pulmonary hypertension recommended for testing | Group 1: IPAH, HPAH, CHD, PVOD/PCH and DT-PAH Group 3: developmental lung disorders and congenital diaphragmatic hernia# |

Group 1: IPAH, HPAH, CHD, PVOD/PCH and DT-PAH | ||

| Type of test recommended | ES/GS, ideally including parental samples | Panel testing; follow-up with ES/GS if panel is negative in HPAH, CHD | Test for family-specific variant | Panel testing: if negative, the test is uninformative |

IPAH: idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension; HPAH: heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension; CHD: congenital heart disease; PVOD: pulmonary veno-occlusive disease; PCH: pulmonary capillary haemangiomatosis; DT-PAH: drug- and toxin-associated PAH; ES: exome sequencing; GS: genome sequencing. #: genetic testing for trisomy 21 and bronchopulmonary dysplasia should be limited to patients with atypical presentation, severity or response to therapy.

Genetic testing should be offered to all paediatric patients with group 1 PH subtypes of IPAH, HPAH, congenital heart disease, pulmonary capillary haemangiomatosis, and drug and toxin-associated PAH and group 3 PH subtypes of developmental lung disorders and congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Genetic testing for individuals with trisomy 21 or bronchopulmonary dysplasia should be limited to patients with atypical presentation, severity or response to therapy. Genetic testing in children should be exome or genome sequencing including both biological parents when possible to identify de novo variants.

Genetic testing in a family ideally should begin with an individual diagnosed with PAH to identify the relevant PAH gene and variant in that family. Otherwise, initial genetic testing on unaffected family members yielding normal results is uninformative and cannot reassure the unaffected family members that they are not at increased risk of PAH.

The provider who orders genetic testing for a patient with PAH may vary by country and/or expertise of the provider. Genetic results should be discussed with providers experienced in genetics including PAH clinicians, medical geneticists and/or genetic counsellors. Clinical care may include care for associated features beyond PAH that require referral to other specialists. Examples include conditions such as those associated with TBX4 (orthopaedic issues), ENG and ACVRL1 (hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia with brain or liver arteriovenous malformations) or SOX17 (congenital heart disease).

Once a pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in a PAH gene is identified, other family members can choose to test to predict their risk of PAH. Most PAH genes are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion with incomplete penetrance. BMPR2 has higher penetrance in females (42% in females and 14% in males) [12]. Genetic testing of asymptomatic family members should be performed by a genetic counsellor/medical geneticist and should include discussion of disease surveillance, treatment options, prognosis with treatment, reproductive implications and reproduction options. Reproductive options can include no genetic testing of the pregnancy, prenatal genetic testing (rarely done), pre-implantation genetic diagnosis after in vitro fertilisation, donor gamete, adoption or choosing not to reproduce. These are complex decisions, especially as reproductive rights in the USA and other countries evolve including limitations on pregnancy termination and in vitro fertilisation. Informed decisions rely heavily on accurate estimates of disease risk over the life course and by sex as well as treatability. Therefore, these decisions are likely to evolve as knowledge and treatments evolve. Genetic counselling by someone experienced with PAH genetics is critical to help individuals make informed reproductive decisions. We encourage development of telemedicine options to disseminate this clinical genetic expertise more widely to PAH patients.

Integration of multiomic approaches with traditional “genetic studies”

PAH classification has historically been performed based upon clinical features, and it is unclear whether there may be other relevant ways to categorise and cluster patients based upon other omic dimensions. Multiomic integration combines data from different “omics” technologies to reveal complex molecular interactions. This approach provides a holistic view of diverse biological dimensions, offering a more complete and nuanced understanding of disease mechanisms. There are three major approaches to multiomics integration: post-analysis data integration, integrated data analysis and systems-modelling techniques. The first two function as discovery tools or hypothesis generators, providing high-level mechanistic insights. In contrast, systems-modelling techniques are primarily interpretive or hypothesis-testing in nature, with the goal of mathematically describing underlying mechanisms [13, 14].

The integration of multiple omics layers, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics, is essential to elucidate the complex mechanisms underlying PAH. Quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping, which identifies genomic regions associated with variation in specific traits, plays an important role in this process [15, 16]. Expression QTLs link genetic variants to gene expression levels [14]; protein QTLs link genetic variants to protein abundance [17] and metabolite QTLs link genetic variants to metabolite concentrations. These QTL analyses help to understand how genetic variations influence intermediate phenotypes and contribute to disease pathology. The over-representation of these QTLs in a disease context, such as PAH, facilitates the identification of underlying biological mechanisms by which genetic risk variants mediate disease susceptibility. For example, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) on circulating proteins revealed cis-acting protein QTLs for the platelet-derived growth factor-β receptor (PDGFRβ), a known drug target in PAH (with safety concerns) [18, 19]. Clinical trials can use protein QTLs to identify patients who will benefit from specific therapies, such as imatinib, which targets PDGFRβ. More recently, Walters et al. [20] utilised multiomic integration to demonstrate how common genetic variants in enhancer regions upstream of the SOX17 gene influence PAH, as described later.

The combination of QTL data and Mendelian randomisation (MR) studies enables the inference of causality between genetic variants and phenotypic traits [21]. MR uses genetic variants as instrumental variables to distinguish causal relationships from correlations, resulting in strong evidence for potential therapeutic targets. In the context of PAH, MR studies have shown that iron deficiency (highly correlated with PAH) is not causally related to the disease, narrowing the focus to more relevant biological pathways [22]. Toshner et al. [23] utilised MR to investigate the causal role of interleukin (IL)-6 in PAH, finding no significant treatment effect with tocilizumab (IL-6 receptor blocker) and no causal link between IL6R variants and PAH risk. Intriguingly, this effect could potentially be reversed by existing drugs.

Systems-modelling techniques study numerous possible simultaneous interactions between relevant genes, proteins and metabolites [24]. For example, mapping perturbed genes, micro (mi)RNAs, and proteins onto the interactome revealed miRNA-21 as a central regulator in pulmonary hypertension [25], highlighted the role of complement in PAH and revealed novel disease pathways and drug targets. This approach, while still in its early stages, shows great promise as more data become available, from the Pulmonary Vascular Disease Phenomics (PVDomics) and other studies. These approaches of multiomics integration increase our understanding of PAH and support the development of precision medicine approaches.

In vitro functional studies are critical in defining the pathogenicity of variants, especially for missense and putative splicing variants. Such studies have contributed significant evidence for one of the newer PAH genes, GDF2, which encodes the ligand BMP9. BMP9 is synthesised as a pro-protein that dimerises and then undergoes furin cleavage. In vitro protein expression studies showed that rare missense variants found in PAH patients disrupt this cleavage process, leading to a reduction in mature BMP9 [10, 26, 27]. PAH patients with GDF2 mutations showed reduced levels of circulating BMP9 in plasma. Plasma BMP9 is also reduced in portopulmonary hypertension, where it predicted transplant-free survival [28]. Available data suggest that associated PAH patients have normal BMP9 plasma levels, although BMP9 levels may be reduced in a subset of IPAH cases [29, 30]. Similarly for TBX4, luciferase reporter assays have been used to assess the pathogenicity of missense variants. This led to the unexpected identification of gain-of-function variants, which were associated with an older age of PAH onset compared with loss-of-function variants [31]. Similar types of studies will be important for other genes that show a preponderance of missense variants, both to add weight to the evidence as definitive PAH genes, and to better understand the underlying molecular mechanisms to guide therapeutic strategies. Additionally, advances in artificial intelligence are providing algorithms that are increasingly accurate at predicting the likely pathogenicity (or otherwise) of missense and splice-region variants. These are a valuable adjunct to wet lab experiments and may in future supersede the need for many in vitro studies.

While exome and genome sequencing studies have made strides in identifying genes harbouring rare variants of relatively high penetrance, the contribution of common genetic variants still lags, mainly because the available cohorts remain underpowered to detect small effects. One notable exception is SOX17, where both rare and common variants have been characterised [20, 32]. GWAS and a meta-analysis identified risk alleles near SOX17 that alter regulation of gene expression in endothelial cells by modulating the function of an enhancer [20]. The risk haplotype conferred a small but highly significant increase in the risk of developing PAH, with an odds ratio of 1.8 [27]. The transcription factor SOX17 plays important roles in cardiac development and pulmonary vascular morphogenesis, and rare loss-of-function variants in this gene may account for up to 3% of PAH cases associated with a structural congenital heart defect [9]. Statistical power to identify causal genetic variation increases with the size of the cohort [10]. Hence, initiatives like the International Consortium for Genetic Studies in PAH (PAH-ICON; https://pahicon.com/) will be critical to maximise size and ethnic diversity of the cohorts for discovery and validation. Prerequisite to this endeavour is the adoption of existing standards such as GA4GH (Global Alliance for Genomics and Health; www.ga4gh.org/), Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership Common Data Model (Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics; www.ohdsi.org/) or Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources to ensure phenotypic data use a common nomenclature and data federation allows for data aggregation to increase power [33, 34].

Assessment of genomics alone only provides an explanation in ∼25% of patients with IPAH. With the advances in high-throughput technologies, additional molecular dimensions can be assessed, allowing for large-scale analysis of gene expression (transcriptomics) and its regulation through DNA methylation, histone modification, chromatin conformation and noncoding RNAs (epigenomics), abundance of proteins (proteomics), lipids (lipidomics) and metabolites (metabolomics) in bulk and more recently even at the single-cell level. In fact, multiple omics analyses are now starting to identify novel biomarkers and pathways associated with PAH with the potential to explore individualised tailored treatment and to improve risk stratification. Transcriptomic profiling of whole blood in 359 patients with HPAH/IPAH identified three subgroups with poor, moderate and good prognosis linked to the dysregulation of a small number of genes [35]. Systems analysis of transcriptomic profiles of explanted PAH and control lung tissues has been used to define distinct endotypes [36]. Similarly, computational analysis has also been applied to define differential dependency networks between cancer and PAH to define drugs that may be repurposed [37]. Ultimately, it will be important to integrate various forms of distinct data for each patient to apply a precision medicine approach to each person [38]. Precision medicine is an integrative approach to cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment that considers an individual's genetics, lifestyle and exposures as determinants of their cardiovascular health and disease phenotypes. This focus overcomes the limitations of reductionism in medicine, which presumes that all patients with the same signs of disease share a common pathophenotype and, therefore, should be treated similarly. Precision medicine incorporates standard clinical and health record data with advanced panomics (i.e. genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, metabolomics, microbiomics) for deep phenotyping. These phenotypic data can then be analysed within the framework of molecular interaction (interactome) networks to uncover previously unrecognised disease phenotypes, relationships between diseases, and select pharmacotherapeutics or identify potential protein–drug or drug–drug interactions.

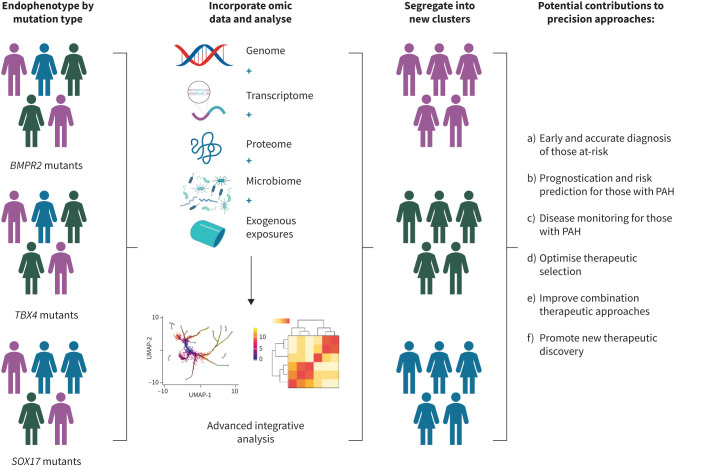

The progress in precision medicine for PAH has been limited beyond clarifying prognosis and associated clinical features for a few PAH genes. For such a precision medicine approach to be successful, endophenotypes are needed for the various genetic drivers. An endotype can define a distinct pathophysiological mechanism as a clinical phenotype that is more refined and specific to the mechanistic aetiology of PAH, potentially with more direct genetic association with the causative gene (reviewed in [39]). For example, BMPR2 heterozygotes with HPAH typically have a subtype of “primary pulmonary hypertension”. In contrast, a person with TBX4-associated HPAH may have combined group 1 and group 3 PH endophenotypes with airway, pulmonary vascular and skeletal abnormalities [40–43]. Future efforts should elucidate gene-associated endotypes (endophenotypes), incorporate various sources of omic-derived data, and complex analyses to 1) guide risk stratification of those at risk; 2) enhance prognostication; 3) facilitate disease monitoring; 4) support therapeutic selection; 5) guide new therapeutic development; and 6) assist in the improvement of combination therapy (figure 2, adapted from [38]). As demonstrated in figure 2, stratification of individuals into groups of people with different rare variants in known PAH-specific genes is only the beginning of precision-based approaches, not the end. Application of current and future omic and related technologies to further explore the biological variations of each patient may allow more precise segregation of patients into clusters of endophenotypes that better facilitate precision approaches to care.

FIGURE 2.

Example of approach to optimise precision approaches to subjects using genomic information (adapted from [38]). As gene-associated endotypes (endophenotypes) are determined, this information may be combined with various sources of omic-derived data, such as transcriptomics and proteomics. Efforts to incorporate exogenous sources of influence, such as environmental or other exposures should also be made. Subsequent integrative analytic approaches may reveal that individuals with similar endophenotype (including pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)-specific mutation) ultimately segregate into different clusters of disease profile. They may have a similar endophenotype, but be biologically distinct and have different disease profiles. This may ultimately improve precision approaches to populations of subjects as well as individuals. BMPR2: bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2; TBX4: T-box transcription factor 4; SOX17: SRY-box transcription factor 17; UMAP: uniform manifold approximation and projection. Created using BioRender.com.

Importance of diverse, well-phenotyped human cohorts followed longitudinally

Observational cohorts of participants with PAH have supported large genomic studies, often but not always multicentre studies from a single country (table 4). These cohorts contribute deeply phenotyped participants, a key component to successful scientific advance, but this approach requires financial support, time and effort on the part of enrolling sites as well as study participants. Enrolment is a multi-year process with clinical data submission, retention of participants and acquisition of longitudinal clinical data. Additional challenges include enrolment bias due to location of centres, which may select for key demographic features such as ancestry, socioeconomic status and severity of disease due to travel limitations, access to care, and other restrictions. Unless intentionally broad, the type of phenotypic data collected may bias toward a particular question or result [54].

TABLE 4.

Cohort characteristics of large, published pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) cohorts in paediatric and adult studies [9, 27, 44–53]

| PAHB | UK NBR | BHFPAH | UK NBR | PVDomics# | PHAR | Spanish | The Netherlands | FinGen | Han Chinese | The Netherlands (paediatric) | PPHNet (only group 1) | Japan and China (paediatric) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | 2572 | 1048 | 275 | 493 | 1193 | 340 | 267 | 126 | 313 | 331 | 154¶ | 663 | 54 |

| Child (<19 years) | 226 (8.8) | NA | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 57 (17) | 154 (100) | 663 (100) | 54 (100) |

| Adult (>19 years) | 2345 (91.2) | 1048 (100) | 275 (100) | 493 (100) | 1193 (100) | 340 (100) | 267 (100) | 126 (100) | 313 (100) | 274 (83) | NA | NA | NA |

| Age years | 48±19 | 45.9±20 | 51.3±7.7 | 63.4±8.21 | 58.2±14.5 | 44.7±18.5 | 48.6±0.9 | 49±16 | 61.2 | 28±10.8 | 22 (0.4–6.7) | 4.3±5.4 | 8.5±3.9 |

| Females | 2023 (78.7) | 723 (68.9) | 184 (66.9) | 250 (50.7) | 742 (62.1) | 237 (70) | 186 (70) | 89 (71) | 206 (65.8) | 258 (77.9) | 80 (51) | 367 (55.3) | 30 |

| Female:male ratio | 3.7:1 | 2.2:1 | 2:1 | 1:1 | 1.64:1 | 2.3:1 | 1.9:1 | 3.5:1 | 1.2:1 | 1.25:1 | |||

| Ancestry | |||||||||||||

| European | 1852 (72) | 934 (81.6) | 275 (100) | 493 (100) | 958 (80) | 340 (100) | 245 (92.8) | 126 (100) | 313 (100) | ||||

| Hispanic | 315 (12.3) | 110 (9.1) | 11 (4.2) | ||||||||||

| African | 292 (11.4) | 145 (12) | 4 (1.5) | ||||||||||

| East Asian | 70 (2.7) | 26 (2.2)+ | 331 (100) | 54 (100) | |||||||||

| South Asian | 28 (1.1) | ||||||||||||

| Others | 15 (0.58) | ||||||||||||

| Haemodynamics | |||||||||||||

| mPAP mmHg | 50±14 | 52 | 55.3±1.1 | 52±17 | 62±14.9 | 51±20 | 64.3±20.6§ | ||||||

| PVR WU | 10.7±7 | 12.6±0.4 | 9.9±1.75 | 15.2±6.9 | 17.8±12.7 | 19.1±11.6 | |||||||

| PCWP mmHg | 10±4 | 9.4 | 9.1±0.3 | 10±3 | 9±2.9 | 9±5 | 9.0±2.7 | ||||||

| Cardiac output L·min−1 | 4.5±1.8 | 3.9 | 4.3±0.1 | ||||||||||

| Mean arterial pressure mmHg | 90±19 | ||||||||||||

| PAH type | |||||||||||||

| IPAH | 1110 (43) | 908 (86.6) | 246 (89.5) | 158 (13.2) | 142 (45.3) | 114 (90) | 331 (100) | 36 (23.3) | |||||

| HPAH | 101 (3.9) | 58 (5.5) | 27 (9.8) | 27 (2.2) | 16 (5.1) | ||||||||

| CHD-PAH | 268 (10.4) | 36 (3.0) | 38 (12.1) | 111 (72) | |||||||||

| CTD-PAH | 722 (28) | 93 (7.8) | 30 (9.5) | 3 (1.9) | |||||||||

| DT-PAH | 110 (4.2) | 60 (5.7) | 2 (0.7) | 16 (1.3) | |||||||||

| HIV-PAH | 110 (4.2) | 10 (0.8) | 1 (0.06) | ||||||||||

| PVOD | 11 (0.4) | 22 (2.1) | 15 (4.7) | 12 (10) | 3 (1.9) | ||||||||

| PoPH-PAH | 139 (5.4) | 18 (1.5) | |||||||||||

| Other | 1 (0.03) | 10 (0.8) | 26 (8.3) |

Data are presented as n, n (%) or mean±sd. PAHB: Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Biobank; UK NBR: UK National Institute for Health Research BioResource – Rare Diseases; BHFPAH: British Heart Foundation PAH cohort; PVDomics: Pulmonary Vascular Disease Phenomics Study; PHAR: Pulmonary Hypertension Association Registry; PPHNet: Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension Network; mPAP: mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance; WU: Wood Units; PCWP: pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; IPAH: idiopathic PAH; HPAH: heritable PAH; CHD: congenital heart disease; CTD: connective tissue disease; DT: drug and toxin; PVOD: pulmonary veno-occlusive disease; PoPH: portopulmonary hypertension; NA: not applicable. #: PVDomics includes all five World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension groups (n=750), together with disease comparators (n=347) and 96 healthy controls; ¶: 19 with genetic testing; +: all Asian subjects combined; §: right heart catheterisation only performed in 44 subjects.

Longitudinal characterisation of genetically-at-risk individuals identified based upon family history or genotype in large disease-agnostic genomic studies will be critical to understand age- and sex-dependent penetrance and natural history that will be critical to inform timing of interventions to prevent PAH just in time to maximise benefits and minimise toxicity. Such studies in the absence of effective methods for prevention or treatment can be psychologically difficult for participants, but have been conducted successfully in other diseases such as Huntington disease [55]. These studies require a long-term commitment of participants and critically depend on individuals to know their genetic status and thus are predicated on patients with PAH accessing genetic testing and sharing results with their family members. Infrastructure and funding to support these efforts internationally will be needed to support these initiatives. At-risk family members do not have to know their genetic status if they prefer not to carry the psychological burden of knowing their risk, and inclusion of genotype-negative family members serve as good controls. Ideally, research protocols will also include in-depth phenotypic assessments, including detailed medical history and physical examinations, echocardiographic-based metrics, lung function studies and perhaps standard and novel mechanisms to image the lungs and pulmonary vasculature (for example, in targeted genetic conditions such as TBX4 heterozygotes who may have developmental lung disease, standard and more novel imaging approaches, such as hyperpolarised gas-anchored magnetic resonance imaging) may be appropriate. However, protocols should include notification of patients once it becomes apparent that PAH progression has begun to allow for initiation of treatment.

Despite these challenges, tremendous progress has been made using existing observational research cohorts. Examples include large national biobanks such as the National Biological Sample and Data Repository for PAH (PAH Biobank), UK National Institute for Health and Care Research BioResource – Rare Diseases (NBR), the British Heart Foundation Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and country-specific cohorts in France, Spain, the Netherlands, China and others. However, there remains an opportunity to address the limitations noted earlier, as well as a tremendous need to expand these studies to individuals underrepresented in genomic studies to date.

In fact, the lack of diversity in human genetic studies remains insufficiently addressed [56]. To date, >72% of people in large-scale genetic studies are of European descent, while African and South Asian ancestries are significantly underrepresented. This substantial imbalance can limit the generalisability of genetic findings across different ancestries and highlights the need for more inclusive research (table 5).

TABLE 5.

Cohorts and registries with available rare variant genetic data

| Subjects n | Ancestry | PAH subtype | Genetic data | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European | African | East Asian | IPAH | HPAH | CHD-PAH | DT-PAH | |||

| PAHB | 2572 | 72 | 11.4 | 2.7 | 43 | 3.9 | 10.4 | 4.2 | WES |

| UK NBR | 1048 | 81.6 | 86.6 | 5.5 | 5.7 | WGS | |||

| BHFPAH | 275 | 100 | 89.5 | 9.8 | 0.7 | WGS | |||

| PHAR | 340 | 100 | WGS | ||||||

| REHAP | 1132 | 73.9 | 11.4 | WES | |||||

| The Netherlands | 126 | 100 | 90 | Panel | |||||

| Han Chinese | 331 | 100 | 100 | WES | |||||

| Paediatric cohorts | |||||||||

| The Netherlands | 19 | 100 | |||||||

| PPHNet | 40 | 100 | |||||||

| REHIPED | 98 | 81.6 | 1 | 53.1 | 5.1 | 30.6 | WES | ||

| Japan/China | 54 | 100 | Panel | ||||||

Data are presented as %, unless otherwise stated. PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; IPAH: idiopathic PAH; HPAH: heritable PAH; CHD: congenital heart disease; DT: drug and toxin; PAHB: Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Biobank; UK NBR: UK National Institute for Health Research BioResource – Rare Diseases; BHFPAH: British Heart Foundation PAH cohort; PHAR: Pulmonary Hypertension Association Registry; REHAP: Rehabilitation in Pulmonary Hypertension; PPHNet: Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension Network; REHIPED: Spanish Registry of Pediatric Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension; WES: whole-exome sequencing; WGS: whole-genome sequencing.

In addition, the incorporation of genetic diversity and genetic variant status has been insufficiently addressed in clinical trials of PAH. The issue is also striking given the skewed enrolment in most industry-sponsored clinical trials. Growing recognition of the contribution of genetics to clinical trial outcomes in other diseases must be applied to PAH. This is particularly important in the case of high-impact rare genetic variants, as trials which do not incorporate genetic variants may falsely discover, or falsely miss, therapeutic effects [57]. It is important for industry- and nonindustry-sponsored trials to incorporate genetic variation in pre-trial design. At a minimum, post-trial analyses should incorporate genetic variation, including future trials and those previously completed and appropriately consented.

Furthermore, given the importance of environmental exposures to penetrance, as well as the growing understanding of PAH genetic variants across the lifecycle, there are opportunities for genomic studies to investigate lifecycle changes. In addition, the differential prevalence and response to therapy between female and male biological sex suggests an opportunity to study the interaction between genomic variations and sex. There are opportunities to incorporate rare and common genetic variants with biological changes through puberty, menopause and late life.

Integration of genome-level data into risk score development and testing

Risk score development continues to expand, improving clinicians’ ability to determine and tailor therapy according to specific patient factors. To date, there has been limited incorporation of genetic data into risk scores, with the exception of heritable PAH status in the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL) 2.0 [58]. While it has been confirmed in a multinational study that BMPR2 heterozygotes have more severe disease, this has not been applied to clinical decision-making, nor has stratification by genetics been incorporated extensively (e.g. according to age, sex or other factors). In depth understanding of the phenotype by monogenic variation is a major missed opportunity.

Risk prediction scores should be developed and will be of immediate relevance to family members carrying genetic risk factors to determine intensity of surveillance over the life course, to best utilise medical resources and minimise psychological burden. Such models will require study of asymptomatic individuals with longitudinal surveillance to ensure accuracy.

Building biological banks: research cohorts within and between countries

As is the case for all rare diseases, sizable cohorts are typically necessary to enable well-powered analyses that yield meaningful results. This is no different for PAH. For common diseases, studies are now being performed using cohorts >100 000. While studies of this magnitude will never be possible for PAH, it is important to include as many patients as possible to ensure the most meaningful results. Recognising the need for a sizeable cohort of PAH patients, the National Biologic Sample and Data Repository for PAH was established with USD 10 million in funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Institutes of Health. Known more commonly as the PAH Biobank (www.pahbiobank.org), this initiative aimed to enrol >2500 group 1 PAH patients across North America. Participants provided blood samples that enabled the banking of plasma, serum, DNA, RNA and transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs). In addition, clinical data were provided for each patient in a secured, encrypted online case report form. DNA prepared from whole blood was used to generate genomic data including whole-genome single nucleotide polymorphism data, panel sequencing of PAH-specific genes and dosage data for a small subset of established PAH genes. The PAH Biobank enrolled 2874 PAH patients over the 6-year enrolment period from 38 different enrolling centres. This included the storage of >100 000 aliquots of both plasma and serum, >20 000 vials of transformed LCLs, 5600 vials of both DNA and RNA, genomic data as well as the associated clinical data collected for enrolees. Created as a resource for the scientific community, these data and samples have been shared with >40 investigators resulting in >50 publications, and several R01 research projects funded using the samples and data.

Other PAH patient cohorts have also yielded significant findings. These include a large UK cohort (NBR consortium, UK PAH Cohort Study Consortium) consisting of >1000 IPAH patients, and the PVDomics project funded by the National Institutes of Health with almost 1200 participants followed longitudinally. Uniquely, PVDomics enrolled all five WSPH groups, together with disease comparators and healthy controls, and will therefore provide novel omics insights across the PH spectrum [46]. Biospecimens include not only peripheral blood, but also blood samples obtained during right heart catheterisation and invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Other smaller cohorts with biospecimens also exist. To this end, it would be advantageous to integrate these existing cohorts for future genetic and other research studies. This is evidenced in the recent report combining the exome sequence data generated for the PAH Biobank and the genome sequence data of the NBR consortium resulting in the rare variant analysis of 4241 PAH cases and several novel genes contributing to PAH. PAH-ICON, a collaborative network of centres around the world, brings research expertise and/or patient populations to the consortium. The group aims to enable studies that will have the statistical power to characterise the genomic architecture of PAH and to address the major questions regarding the role of genetic variation on disease penetrance, phenotype and the clinical course of disease.

Another potentially important resource for the study of PAH genetics and genomics are the large and broad population biobanks both in the USA and the UK. The All of Us Research Program in the USA, funded by the National Institutes of Health, is inviting 1 million people across the USA to build one of the most diverse health databases available. Researchers can use the data to learn how biology, lifestyle and environment affect health. To date, >519 000 participants have completed all the initial steps of the study. Short-read genome sequencing is available for 245 400 of the participants. These data are available by registering on the website (https://researchallofus.org/). While there may be individuals with PAH enrolled in this program, largely, the All of Us programme participants can serve as controls for PAH studies. The UK Biobank is an even larger resource of data for additional PAH patients or control data. It is a large-scale biomedical database and research resource containing in-depth, de-identified genetic and health data from a half million UK participants. It is globally accessible to approved researchers and scientists undertaking vital research into the most common and life-threatening diseases. The UK Biobank includes the largest genome sequencing dataset in the world having sequenced all 500 000 participants with a wide range of biochemical markers in samples collected at baseline from all 500 000 participants. Both the All of Us Research Program and the UK Biobank can provide important data for PAH genetic (and other) studies either by identifying additional patients with PAH or as control data.

Genetic condition specific registries for each PAH gene need to be developed to support each of the rare genetic disease communities associated with PAH. These research registries should use a common core of PAH data elements, but also need to include condition-specific elements. Building online international rare genetic disease communities is empowering to patients and their families and can provide critical biospecimens and data to allow for effective partnership with researchers to develop novel treatments. Hence, during the WSPH in Barcelona we initiated a “call to action” for building future PH cohorts. Interested scientists can register their interest at https://bit.ly/BuildingFuturePHCohorts (supplementary figure S1), which will be followed-up within the PAH-ICON.

Key role for engagement and partnership with stakeholders

Successful research into the genomic and other features of PAH is intimately related to patient and family participation in research studies. In addition, integration of researchers around the world and among academic medicine, governmental and nongovernmental organisations and industry is vital.

A key element is inclusion, particularly of all patients and their family members and patient advocacy groups. Barriers to participation exist, including but not limited to challenges with time commitment for participation, incomplete understanding of study goals and complexities about the return of study results due to the need for confirmation of research genetic results in a clinical laboratory. Physicians and other medical providers should be involved in study design and implementation, and educated on the conduct and results of studies in which their patients participate [59].

Overall, there is a tremendous opportunity for leading PH researchers and organisations to partner with other stakeholders to develop guidelines and agreements for 1) engagement of patients and families, in particular, in study design and conduct; 2) engagement of medical providers; 3) determination of mechanisms to share genetic data under a framework with involvement of genetic counselling/education; and 3) proactive engagement of diverse populations supported across cultures, socioeconomic levels and geographic locations.

Application of new discoveries to clinical care and research studies

An underdeveloped area is biospecimen data and genomic data from clinical trials in PAH. Adding additional dimensions of data might be critical in post hoc analyses of outcomes of clinical trials, especially those that do not meet their primary outcome and/or are associated with toxicity. Stratification by genotype could identify subsets of responders, nonresponders or individuals with adverse outcomes and could help to reconsider medications for genetically defined subsets of patients. As an example, adverse events due to hypersensitivity with abacavir for HIV were limited to individuals with an HLA-B*5701 that are now genotyped prior to drug initiation and identification of this genotoxicity salvaged a drug that otherwise would have been discarded due to adverse events [60].

Typically, clinical trial participants are deeply phenotyped (although not in a homogeneous manner across trials) including well-defined PAH subtypes, clinical information, medicinal exposures and biospecimen data. It is increasingly common to incorporate genomic and molecular characterisation into trial designs, presuming that comprehensive molecular profiling will accelerate precision therapeutic selection. For example, the identification of genetic variants that modify response to existing and novel therapeutic agents is an important potential advance not realised in PH. While not specific to PH, a number of barriers impair incorporation of genetic analyses into clinical trials, such as 1) genomic data are often not included in the limited budget allocations available to conduct expensive nonindustry-sponsored clinical trials and/or industry partners have little incentive to support such data generation for industry-sponsored trials; 2) a uniform approach to centralised storage for genomic and similar data is limited; 3) deposition of data into public repositories is often incomplete and/or delayed relative to study completion/publication, or, matching phenotypic data are incomplete; 4) bioinformatics platforms lack uniform file formats, data quality filter parameters, and other variations that discourage harmonisation across data sources; and 5) restrictions to data sharing across national borders are complicated and vary by country and region [61]. Each of these barriers inhibit investigators’ ability to reanalyse or combine datasets for scientific discovery.

The capacity to view the genomic data across all completed trials at the subject level might stimulate tremendous advances. Such a need demands a change in our field regarding data access. An effective system would harmonise data across clinical trial and other human cohort studies to facilitate maximally effective use of genomic and phenotypic data. For example, secondary analysis of several US FDA-derived industry-sponsored datasets has proven highly successful in expanding our understanding of phenotypic differences in trial outcomes, surrogate end-points and other contributions. Similar analyses incorporating genomic data may prove beneficial and is a lost study opportunity [62–64].

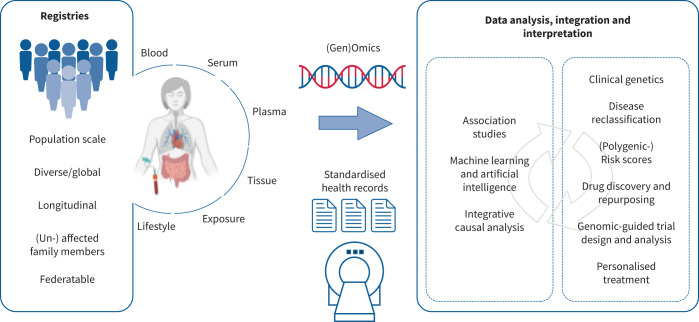

Ultimately, genetic and genomic contributions to the PH field will flourish by the integration of patient-derived data from a wide variety of sources linked to accessible biospecimens for research. Data generated from these sources will require advanced forms of data analysis, integration and interpretation. A continually iterative process will harmonise with clinical phenotypic advances, novel approaches to therapeutic development, and clinical trial designs to truly achieve precision-based PH management and approach to those who are healthy but at risk (figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Harmonisation of resources, biomedical reagents and information and analytic approaches must be achieved to truly advance the field.

Summary

There have been significant advances in the genetic understanding of PAH. We provide updated guidelines for clinical genetic testing, which should start with the patient before testing healthy family members. Important gaps remain in our knowledge of genetic contributions to PAH across the lifespan, particularly in children, genetic and nongenetic modifiers of penetrance over the life course, natural history, and response to therapy for each genetic subtype of PAH. Larger and more diverse cohorts, particularly those that include longitudinal and treatment data and clinical trial data, will be critical to answer these questions. Inclusion of asymptomatic genetically at-risk individuals with longitudinal data will minimise biases that could inflate penetrance estimates. Multiomic data could help to refine risk estimate and elucidate molecular mechanisms. All of this information will be important for the next generation of therapies that could include genetically based therapies to correct the underlying genetic cause, but perhaps only if individuals are identified before irreversible disease manifestations arise.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-01370-2024.Supplement (24.7KB, pdf)

Shareable PDF

Acknowledgements

Progress in the pursuit of scientific knowledge regarding the genetics and genomics of PAH cannot proceed without the generous participation of countless patients and impacted families. We thank each research participant for their contribution through the years, as well as the countless scientists involved in PAH research. In addition, the authors wish to acknowledge the contributions to the field of PAH genetics and PH more broadly by our friend and collaborator, John H. Newman, a leader in the PH theatre and member of this task force, who unfortunately passed away in early 2024.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: E.D. Austin reports grants from NIH (R01FD007627; 1R01HL134802; T32HL160508; R01HL169859; R34HL173389; 5P01HL108800) and the Cardiovascular Medical Research Fund, payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, manuscript writing or educational events from Acceleron, Inc., participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board with NIH, and leadership roles with PHA and TBX4Life. M. Alotaibi reports grants from NIH. M.A. Aldred reports grants from NHLBI and a leadership role with the International Consortium for Genetics Studies in PAH (PAH-ICON). S. Gräf reports a leadership role as Co-Chair of the International Consortium for Genetic Studies in Pulmonary (Arterial) Hypertension (P(A)H-ICON). W.C. Nichols reports grants from NIH/NHLBI. R.C. Trembath reports support for attending meetings from conference organisers. W.K. Chung has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Mendell JR, Al-Zaidy S, Shell R, et al. Single-dose gene-replacement therapy for spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1713–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee J-A, Cho A, Huang EN, et al. Gene therapy for cystic fibrosis: new tools for precision medicine. J Transl Med 2021; 19: 452. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-03099-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deng Z, Morse JH, Slager SL, et al. Familial primary pulmonary hypertension (gene PPH1) is caused by mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein receptor-II gene. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 67: 737–744. doi: 10.1086/303059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International PPH Consortium , Lane KB, Machado RD, et al. Heterozygous germline mutations in BMPR2, encoding a TGF-β receptor, cause familial primary pulmonary hypertension. Nat Genet 2000; 26: 81–84. doi: 10.1038/79226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guignabert C, Aman J, Bonnet S, et al. Pathology and pathobiology of pulmonary hypertension: current insights and future directions. Eur Respir J 2024; 64: 2401095. [ 10.1183/13993003.01095-2024]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welch CL, Aldred MA, Balachandar S, et al. Defining the clinical validity of genes reported to cause pulmonary arterial hypertension. Genet Med 2023; 25: 100925. doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2023.100925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rehder C, Bean LJH, Bick D, et al. Next-generation sequencing for constitutional variants in the clinical laboratory, 2021 revision: a technical standard of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med 2021; 23: 1399–1415. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01139-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houge G, Laner A, Cirak S, et al. Stepwise ABC system for classification of any type of genetic variant. Eur J Hum Genet 2022; 30: 150–159. doi: 10.1038/s41431-021-00903-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu N, Pauciulo MW, Welch CL, et al. Novel risk genes and mechanisms implicated by exome sequencing of 2572 individuals with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Genome Med 2019; 11: 69. doi: 10.1186/s13073-019-0685-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu N, Swietlik EM, Welch CL, et al. Rare variant analysis of 4241 pulmonary arterial hypertension cases from an international consortium implicates FBLN2, PDGFD, and rare de novo variants in PAH. Genome Med 2021; 13: 80. doi: 10.1186/s13073-021-00891-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swietlik EM, Fay M, Morrell NW. Unlocking the potential of genetic research in pulmonary arterial hypertension: insights from clinicians, researchers, and study team. Pulm Circ 2024; 14: e12353. doi: 10.1002/pul2.12353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larkin EK, Newman JH, Austin ED, et al. Longitudinal analysis casts doubt on the presence of genetic anticipation in heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 186: 892–896. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201205-0886OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leopold JA, Hemnes AR. Integrative omics to characterize and classify pulmonary vascular disease. Clin Chest Med 2021; 42: 195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2020.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinu FR, Beale DJ, Paten AM, et al. Systems biology and multi-omics integration: viewpoints from the metabolomics research community. Metabolites 2019; 9: 76. doi: 10.3390/metabo9040076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin S-Y, Fauman EB, Petersen A-K, et al. An atlas of genetic influences on human blood metabolites. Nat Genet 2014; 46: 543–550. doi: 10.1038/ng.2982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long T, Hicks M, Yu HC, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies common-to-rare variants associated with human blood metabolites. Nat Genet 2017; 49: 568–578. doi: 10.1038/ng.3809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun BB, Maranville JC, Peters JE, et al. Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature 2018; 558: 73–79. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0175-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghofrani HA, Morrell NW, Hoeper MM, et al. Imatinib in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients with inadequate response to established therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182: 1171–1177. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0123OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoeper MM, Barst RJ, Bourge RC, et al. Imatinib mesylate as add-on therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: results of the randomized IMPRES study. Circulation 2013; 127: 1128–1138. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walters R, Vasilaki E, Aman J, et al. SOX17 enhancer variants disrupt transcription factor binding and enhancer inactivity drives pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 2023; 147: 1606–1621. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.061940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsson SC, Butterworth AS, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization for cardiovascular diseases: principles and applications. Eur Heart J 2023; 44: 4913–4924. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ulrich A, Wharton J, Thayer TE, et al. Mendelian randomisation analysis of red cell distribution width in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1901486. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01486-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toshner M, Church C, Harbaum L, et al. Mendelian randomisation and experimental medicine approaches to interleukin-6 as a drug target in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2022; 59: 2002463. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02463-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menche J, Sharma A, Kitsak M, et al. Disease networks. Uncovering disease–disease relationships through the incomplete interactome. Science 2015; 347: 1257601. doi: 10.1126/science.1257601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parikh VN, Jin RC, Rabello S, et al. MicroRNA-21 integrates pathogenic signaling to control pulmonary hypertension: results of a network bioinformatics approach. Circulation 2012; 125: 1520–1532. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.060269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gräf S, Haimel M, Bleda M, et al. Identification of rare sequence variation underlying heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Commun 2018; 9: 1416. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03672-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhodes CJ, Batai K, Bleda M, et al. Genetic determinants of risk in pulmonary arterial hypertension: international genome-wide association studies and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2019; 7: 227–238. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30409-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robert F, Certain MC, Baron A, et al. Disrupted BMP-9 signaling impairs pulmonary vascular integrity in hepatopulmonary syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2024; 210: 648–661. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202307-1289OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X-J, Lian TY, Jiang X, et al. Germline BMP9 mutation causes idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2019; 53: 1801609. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01609-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodgson J, Swietlik EM, Salmon RM, et al. Characterization of GDF2 mutations and levels of BMP9 and BMP10 in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 201: 575–585. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201906-1141OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van den Heuvel LM, Jansen SMA, Alsters SIM, et al. Genetic evaluation in a cohort of 126 Dutch pulmonary arterial hypertension patients. Genes 2020; 11: 1191. doi: 10.3390/genes11101191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu N, Welch CL, Wang J, et al. Rare variants in SOX17 are associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension with congenital heart disease. Genome Med 2018; 10: 56. doi: 10.1186/s13073-018-0566-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fischer, P, Stöhr, M R, Gall, H, et al. Data integration into OMOP CDM for heterogeneous clinical data collections via HL7 FHIR bundles and XSLT. Stud Health Technol Inform 2020; 270: 138–142. doi: 10.3233/SHTI200138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biedermann P, Ong R, Davydov A, et al. Standardizing registry data to the OMOP Common Data Model: experience from three pulmonary hypertension databases. BMC Med Res Methodol 2021; 21: 238. doi: 10.1186/s12874-021-01434-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kariotis S, Jammeh E, Swietlik EM, et al. Biological heterogeneity in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension identified through unsupervised transcriptomic profiling of whole blood. Nat Commun 2021; 12: 7104. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27326-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stearman RS, Bui QM, Speyer G, et al. Systems analysis of the human pulmonary arterial hypertension lung transcriptome. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2019; 60: 637–649. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2018-0368OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Negi V, Yang J, Speyer G, et al. Computational repurposing of therapeutic small molecules from cancer to pulmonary hypertension. Sci Adv 2021; 7: eabh3794. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abh3794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leopold JA, Loscalzo J. Emerging role of precision medicine in cardiovascular disease. Circ Res 2018; 122: 1302–1315. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Genkel VV, Shaposhnik II. Conceptualization of heterogeneity of chronic diseases and atherosclerosis as a pathway to precision medicine: endophenotype, endotype, and residual cardiovascular risk. Int J Chronic Dis 2020; 2020: 5950813. doi: 10.1155/2020/5950813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Austin ED, Elliott CG. TBX4 syndrome: a systemic disease highlighted by pulmonary arterial hypertension in its most severe form. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 2000585. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00585-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galambos C, Mullen MP, Shieh JT, et al. Phenotype characterisation of TBX4 mutation and deletion carriers with neonatal and paediatric pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2019; 54: 1801965. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01965-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kerstjens-Frederikse WS, Bongers EM, Roofthooft MT, et al. TBX4 mutations (small patella syndrome) are associated with childhood-onset pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Med Genet 2013; 50: 500–506. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thoré P, Girerd B, Jaïs X, et al. Phenotype and outcome of pulmonary arterial hypertension patients carrying a TBX4 mutation. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1902340. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02340-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DesJardin JT, Kolaitis NA, Kime N, et al. Age-related differences in hemodynamics and functional status in pulmonary arterial hypertension: baseline results from the Pulmonary Hypertension Association Registry. J Heart Lung Transplant 2020; 39: 945–953. 10.1016/j.healun.2020.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martínez‐Meñaca A, Cruz‐Utrilla A, Mora‐Cuesta VM, et al. Simplified risk stratification based on cardiopulmonary exercise test: a Spanish two‐center experience. Pulm Circ 2024; 14: e12342. 10.1002/pul2.v14.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hemnes AR, Leopold JA, Radeva MK, et al. Clinical characteristics and transplant-free survival across the spectrum of pulmonary vascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022; 80: 697–718. 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.05.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Post MC, Van Dijk, Hoendermis ES, et al. PulmoCor: national registry for pulmonary hypertension. Neth Heart J 2016; 24: 425–430. 10.1007/s12471-016-0830-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pentikäinen M, Soini E, Asseburg C, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) patients in Finland (FINPAH) – a descriptive retrospective real world cohort study between. Value Health 2022; 25: S43. 10.1016/j.jval.2022.09.208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang R, Dai L-Z, Xie W-P, et al. Survival of Chinese patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern treatment era. Chest 2011; 140: 301–309. 10.1378/chest.10-2327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Castaño JAT, Hernández-Gonzalez I, Gallego N, et al. Customized massive parallel sequencing panel for diagnosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Genes 2020; 11: 1158. 10.3390/genes11101158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haarman MG, Kerstjens-Frederikse WS, Vissia-Kazemier TR, et al. The genetic epidemiology of pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Pediatr 2020; 225: 65–73. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyamoto K, Inai K, Kobayashi T, et al. Outcomes of idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension in Japanese children: a retrospective cohort study. Heart Vessels 2021; 36: 1392–1399. 10.1007/s00380-021-01806-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang M-T, Charng M-J, Chi P-L, et al. Gene mutation annotation and pedigree for pulmonary arterial hypertension patients in Han Chinese patients. Global Heart 2021; 16: 67. 10.5334/gh.1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bowton E, Field JR, Wang S, et al. Biobanks and electronic medical records: enabling cost-effective research. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6: 234cm3. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jiang A, Handley RR, Lehnert K, et al. From pathogenesis to therapeutics: a review of 150 years of Huntington's disease research. Int J Mol Sci 2023; 24: 13021. doi: 10.3390/ijms241613021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sirugo G, Williams, SM, Tishkoff, SA. The missing diversity in human genetic studies. Cell 2019; 177: 26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leonard H, Blauwendraat C, Krohn L, et al. Genetic variability and potential effects on clinical trial outcomes: perspectives in Parkinson's disease. J Med Genet 2020; 57: 331–338. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2019-106283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Benza RL, Gomberg-Maitland M, Elliott CG, et al. Predicting survival in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: the REVEAL risk score calculator 2.0 and comparison with ESC/ERS-based risk assessment strategies. Chest 2019; 156: 323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Appelbaum PS, Stiles DF, Chung W. Cases in precision medicine: should you participate in a study involving genomic sequencing of your patients? Ann Intern Med 2019; 171: 568–572. doi: 10.7326/M19-1414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stekler J, Maenza J, Stevens C, et al. Abacavir hypersensitivity reaction in primary HIV infection. AIDS 2006; 20: 1269–1274. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000232234.19006.a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Asad S, Kananen K, Mueller KR, et al. Challenges and gaps in clinical trial genomic data management. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 2022; 6: e2100193 doi: 10.1200/CCI.21.00193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mathai SC, Puhan MA, Lam D, et al. The minimal important difference in the 6-minute walk test for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 186: 428–433. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0480OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]