Abstract

Clubroot disease caused by the infection of Plasmodiophora brassicae is widespread in China, and significantly reduces the yield of Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). However, the resistance mechanism of Chinese cabbage against clubroot disease is still unclear. It is important to exploit the key genes that response to early infection of P. brassicae. In this study, it was found that zoospores were firstly invaded hair roots on the 8th day after inoculating with 1 × 107 spores/mL P. brassicae. Transcriptome analysis found that the early interaction between Chinese cabbage and P. brassicae caused the significant expression change of some defense genes, such as NBS-LRRs and pathogenesis-related genes, etc. The above results were verified by quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Otherwise, peroxidase (POD) salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA) were also found to be important signal molecules in the resistance to clubroot disease in Chinese cabbage. This study provides important clues for understanding the resistance mechanism of Chinese cabbage against clubroot disease.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-76634-0.

Subject terms: Plant sciences, Transcriptomics

Introduction

Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis) is Brassica plant in the Cruciferae family1. Clubroot disease caused by Plasmodiophora brassicae Woronin (P. brassicae) is a worldwide soil-borne disease of the Brassicaceae, which can lead to plant wilting, weak growth, low absorption of water and nutrients to influent the production of Chinese cabbage2,3.

The life cycle of P. brassicae is divided into two main stages: the primary infection of root hair and the secondary infection of the cortex tissue4,5. In the primary infection period of root hair, each resting spore germinates to a primary zoospore. These zoospores swim to and infect root hairs by penetrating the cell wall. Within the root hairs, primary plasmodia develop quickly and cleave into zoosporangia, each containing 4–16 secondary zoospores. Secondary infection is followed by the development of secondary plasmodia within the root cortex, which results in the production of clubroot symptoms6. Each secondary plasmodium was cleaved into large numbers of resting spores within the clubbed root. As the root tissues disintegrate, the resting spores are released into the soil and remain in the soil for at least 10 years7, making it difficult to control in the field once soil is contaminated8,9. The virulence of populations of P. brassicae contained a range of pathotypes10. P. brassicae usually exists as a mixture of several pathotypes, which has hampered the research on resistance mechanisms of cruciferous crops against P. brassicae11. The pathotypes of P. brassicae were commonly assessed using the Williams classification12, the European Clubroot Differential (ECD) set13, and Sinitic clubroot differential (SCD) set14,15. The Williams classification is still widely used because the small number of host lines are easier to manage, requiring less space and time than the other systems. Lv et al. (2021) developed a stable method for isolation and production of single-spore brassicas using Williams system, and revealed pathotype 4 was the most prevalent in China11. So pathotype 4 was used as pathogen in this study. To P. brassicae populations, when the inoculation concentration was 1 × 107 spores/mL, infection rate of root hairs was the highest, and plasmodia spores were found in the root hairs on the 4th day after inoculation16. Therefore, previous researchers used the P. brassicae populations with a concentration of 1 × 107 to infect Chinese cabbage seedlings17,18. To use pathotype 4 as pathogen for subsequent studies, it is necessary to find its optimal infection concentration and the earliest infection period.

Plants are attacked by a variety of microbial pathogens throughout their life cycle. Unlike animals, plants have no adaptive immune system, but they can make use of innate immunity of their own cells to generate systemic acquired resistance (SAR) or induced systemic resistance (ISR)19. Of these, the salicylic acid (SA) signaling pathway results in the activation of SAR, while the jasmonic acid (JA)/ethylene (ET) signaling pathway is involved in ISR20. SA signaling generally regulates plant defense against biotrophic pathogens, and JA/ET-dependent signaling pathways are required for resistance against necrotrophic pathogens21. As an endogenous signal molecule of SAR signal transduction pathway, SA has been demonstrated in tobacco, cucumber and Arabidopsis22. JA is an important endogenous regulator in plants and a major regulator of induction defense signaling network23,24. POD is one of the most stable plant enzymes, converts hydrogen peroxide into water25. Increasing the content of POD in plants can improve the antioxidant capacity of plants, and then improve the stress resistance of plants26.

In recent years, an increasing number of studies have been employed to examine the interactions between hosts and P. brassicae by transcriptome. RNA-seq technology is frequently used and created favorable conditions for us to explore the molecular mechanisms between plants and P. brassicae3,9,27,28,]. It was predicted the possible regulatory mechanisms among plant genes or proteins after P. brassicae infection of roots and stems through transcriptome analysis. Transcriptome analysis of Arabidopsis at the beginning of P. brassicae infection (24 and 48 h) showed that flavonoids and the lignin synthesis pathways were enhanced, glucosinolates, terpenoids, and proanthocyanidins accumulated and many hormonal and receptor-kinase related genes were expressed29.

In the early stage of infection by P. brassicae, the differences between the R line and S line of Chinese cabbage had been already shown along with the host’s defense against P. brassicae was induced. Among them, the activity of defense enzymes was elevated, and some genes involved in DNA repair were expressed8,30. Therefore, studying early response genes in the host-pathogen interactions may provide a considerable discovery.

In this study, the optimal concentration and time for P. brassicae spore suspension for infecting seedlings of Chinese cabbage were studied; RNA-seq analysis was performed on the roots infected by P. brassicae at the initial stage; The content levels of some key signal molecules were detected. Finally, the earliest regulatory genes were tried to be explored. These results will provide new ideas for understanding the interaction mechanism between Chinese cabbage and P. brassicae in the early infection stage.

Materials

The materials used in the experiment were susceptible variety‘SN742’of Chinese cabbage and physiological race no.4 of P. brassicae. Both were preserved by Liaoning Key Laboratory of Genetics and Breeding for Cruciferous Vegetable Crops, College of Horticulture, Shenyang Agricultural University.

Methods

Preparation of P. brassicae spore suspension

The pathogen used in this study was NO.4 physiological race of P. brassicae, which was isolated and reproduced with Chinese cabbage in previous work11. 200 g clubbed roots with NO.4 physiological race of P. brassicae were rinsed three times with sterile water, homogenized in 500 mL of sterile water with a blender (JYL-C022E, Joyoung, China), and then filtered through eight layers of cotton gauze, and the filtrate was clarified by centrifugation twice (BiofugeStratos, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 3000 rpm for 9 min and 4000 rpm for 12 min. The concentration of resting spores was measured using a hemocytometer and adjusted to 1 × 105, 1 × 106, 1 × 107, 1 × 108 (spores/mL) respectively with Hoagland nutrient solution.

Preparation of plant materials

Seeds of Chinese cabbage variety ‘SN742’ were reproduced by self-pollination. The seeds were surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol for 1 min, washed twice with sterile water, placed in a petri dish lined with wet filter paper, and cultured in the dark at about 25℃ for about 2 days until the root hairs grew out. The seedlings were divided into two groups: one group was inoculated with P. brassicae (Treatment group, T) and the other group was control group (CK). For treated group, a drop of agar solution (80 µL, 1.0%) was pipetted on a sterilized glass slide. After solidification,1 mL of the different concentration of P. brassicae spore suspension was added to the surface of agarose block and then placed on the root hairs of germinated seeds such that the spore side was touching the roots. After 3 days of cultivation in the dark at 25℃, the seedlings of treated and control group were transferred to a 2 mL uncovered centrifuge tube and cultured with Hoagland nutrient solution in an incubator (16 h light/8 h dark, 25℃, 60% humidity).

Three randomly selected plants were observed under a microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i, Japan) every 24 h until root hair infection was confirmed for sampling. Five plants were randomly selected from T or CK groups to form two sample pools. Three biological replicates were performed for each Pool. The roots were cleaned with distilled water, dried on a paper towel, wrapped in tin foil, quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80℃. The cytological observation methods for the infection process were as described in a previous study11.

RNA extraction

Frozen roots were placed in a mortar, followed by grinding with a pre-cooled pestle in the presence of liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted with the RNA extraction kit (Sangon, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted RNA samples were assessed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis to avoid RNA degradation or impurities.

RNA-seq

The qualified samples were sent to BGI Shenzhen Co., Ltd. for RNA-seq. Total RNA is extracted from the samples, and the long-stranded RNA is split into short fragments, which are then reverse-transcribed into cDNA. cDNA libraries for sequencing are constructed through steps such as joining joints (adapters) and PCR amplification. The cDNA libraries are sequenced using high-throughput sequencing platforms (e.g. Illumina, Ion Torrent, etc.). Finally, data analysis is performed. The raw reads were cleaned by removing the adapter sequence, N-sequence, and low-quality reads. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between two groups were screened by NOISeq method and according to the following: foldchange ≥ 2, false discovery rate (P value) < 0.05, and diverge probability ≥ 0.8.

Bioinformatics analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) (https://www.geneontology.org) was used to enrich analyze the genes with significant differential expression, and obtained GO annotation of each differentially expressed gene. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) public database (https://www.kegg.jp/ or https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) was used for pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs. The cDNA sequences of the differential genes were obtained from the Brassica Database (http://brassicadb.cn/#/). Search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) for detailed functions of some key genes. The above references to previous methods31,32.

Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis

The genes with the expression difference exceeding twice were selected to verify the results of RNA-Seq. Corresponding primers were designed using Primer 5.0 and showed in Table S1. First-strand cDNAs were synthesized using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), an oligo-(dT) 15 primer, and Recombinant RNasin Ribonu-clease Inhibitor (Takara Co. Ltd., Japan). BrActin gene of Chinese cabbage was used as an internal reference gene33, whose primer sequence was showed in Table S1. The qRT-PCR analysis performed on the IQ5 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, USA) with the UItraSYBR Mixture kit (low ROX) (ComWin Biotech, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The study was arranged in a completely random design with three replicates and five seedlings per experimental unit. The expression level of relative gene was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Data were analyzed using SPSS 11.5 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), and Origin Pro 7.5 (Origin Lab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA) was used to produce the graphics.

Determination of POD concentration

The POD concentration was determined based on previous research26 and adjusted appropriately. 1 g of roots from treatment group or control group was put into a sterile pre-cooled mortar, added 10 mL phosphate buffer with pH = 7, and then added a small amount of quartz sand to grind evenly. The POD extract was centrifuged and stored at 4℃. The reaction solution without POD extract was used as a blank control. The absorbance changes within 40 s were measured under the wave length of 470 nm, and take the linear change part to calculate the absorbance changes per minute (ΔA470). POD activity expressed as ΔA470 min− 1g− 1. Student’s t test (α = 0.05 or α = 0.01) was conducted for evaluating the significance differences among the mean values. Data were analyzed using SPSS 11.5 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), and Origin Pro 7.5 (Origin Lab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA) was used to produce the graphics. The study was arranged in a completely random design with three replicates and five seedlings per experimental unit.

Results

Infection efficiency analysis of different concentration of P. Brassicae

From the 5th day after inoculation with different concentrations of P. brassicae spore suspension, the infection status of seedling roots was observed under microscope. It was found that when the concentration of P. brassicae was too high (such as 1 × 108 spores/mL), the seedlings gradually died, while the plants could grow normally under other lower concentrations of P. brassicae spores (Fig. 1). The microscopical observation showed that the zoospores were firstly found in the infected roots on the 8th day after inoculation with 1 × 107 spores/mL, while lower P. brassicae concentrations (1 × 106 or 1 × 105 spores/mL) delayed infection for two to four days (Table 1), higher P. brassicae concentrations (1 × 108) killed plants. These results indicated that the infection progress was related to P. brassicae concentrations. 1 × 107 spores/mL was the optimal concentration due to its shortest infection period and slight damage to plants.

Fig. 1.

The state of plant growth on the 8th day after being inoculated with different concentration of P. brassicae spore suspension.

Table 1.

The infection status of root hairs of Chinese cabbage at different time after inoculation with different concentration of P. Brassicae spore suspension.

| Concentrations of P. brassicae spore suspension (spores/mL) | The infection status of root hairs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 d | 10 d | 12 d | 14 d | |

| 1 × 105 | \ | \ | √ | √ |

| 1 × 106 | \ | √ | √ | √ |

| 1 × 107 | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 1 × 108 | × | × | × | × |

\, The absence of infection by spores of P. brassicae; √, the infection of spores of P. brassicae; ×, P. brassicae spores is unobserved in dead plants.

Transcriptome sequencing analysis

DEGs between the infected and control roots on the 8th day after inoculation with 1 × 107 spores/mL (optimal concentration) of P. brassicae of were analyzed by RNA-seq technology, 23,786,510 raw sequencing reads and then 23,711,138 clean reads were obtained after filtering low quality. The available data rate is around 99%, which is sufficient for further analysis (Table S2). Further analysis revealed that a total of 1378 DEGs were identified, 826 genes were significantly down-regulate expressed and 552 genes were significantly up-regulate expressed after infection by P. brassicae (Fig. 2). These remarkably DEGs were then used for further experimental analysis.

Fig. 2.

DEGs between the control (CK) and treatment (T) groups from three replicates of Chinese cabbage at the initial infection stage.

GO analysis

The distribution of species gene function was performed using GO. A total of 656 DEGs were assigned to three GO classes: biological process, cellular component, and molecular function (Fig. 3). In biological process functional classification, DEGs of the “metabolic process”, “cellular process”, and “response to stimulus” accounted for a large proportion, (73.78%, 69.82% and 58.84% respectively). In cell components classification, DEGs of “cell”, “cell part”, and “organelle” accounted for a large proportion (85.06%, 85.06 and 59.30% respectively). In molecular function functional classification, DEGs of “binding” and “catalytic activity” accounted for a large proportion (66.62%, and 51.98% respectively).

Fig. 3.

GO analysis of DEGs between the control (CK) and treatment (T) groups of Chinese cabbage at the initial infection stage. The proportion of DEGs in the cellular component, biological process, and molecular function categories are shown. Red indicates up-regulated genes; green indicates down-regulated genes in the roots of T group.

KEGG pathway analysis

The results of pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs based on KEGG database showed that a total of 890 DEGs were annotated in the KEGG database and assigned to 116 KEGG pathways. Among them, the top 20 of KEGG pathways were displayed on Table S3. The “Metabolic pathway” was the most enriched term and contained 272 DEGs (30.56%), including 84 up-regulated genes and 188 down-regulated genes; In the term of “Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites”, there were 157 DEGs (17.64%), including 53 up-regulated genes and 104 down-regulated genes; In the term of “Plant hormone signal transduction”, there were 60 DEGs (6.74%), including 37 up-regulated genes and 23 down-regulated genes. In the term of “Plant-pathogen interaction”, there were 48 DEGs (5.39%), including 32 up-regulated genes and 16 down-regulated genes (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Top 20 terms of KEGG analysis of DEGs between the control (CK) and treatment (T) groups of Chinese cabbage at the initial infection stage. Orange indicates up-regulated genes; blue indicates down-regulated genes in the roots of T group.

Differential expression analysis of resistance-related genes

In order to understand the role of resistance-related genes in Chinese cabbage infected by P. brassicae at the initial stage, 52 differentially regulated disease resistance genes (16 disease resistance genes with the structure of NBS-LRR, six pathogenesis-related protein genes, 23 autophagy-related genes, three Ca2+ binding genes and four chitinases-related genes) were obtained and analyzed separately. The enrichment analysis of these DEGs was shown in Fig. 5 and Table S4. Among the disease resistance genes with NBS-LRR structure, ten genes were up-regulated, six genes were down-regulated, and the expression difference of three genes (Bra030997, Bra019410 and Bra040841) was more than twice between T and CK groups. Among the pathogenesis-related (PR) protein genes, six of them were up-regulated, one was down-regulated, and the expression difference of five genes (Bra038986, Bra038988, Bra038981, Bra038982 and Bra034581) was more than twofold. There were 11 up-regulated genes and 12 down-regulated genes in autophagy-related genes. In Ca2+ binding genes, one of which was up-regulated, two of them were down-regulated. In chitinases-related genes, one gene (Bra038726) was up-regulated, with expression differences exceeding twice include of RNA-seq results. To detect the reliability of RNA-seq results, selecting DEGs with expression differences exceeding twice include for further detection by qRT-PCR. The results showed that their expression was consistent with the transcriptome results (Fig. 6). This further demonstrated the high reliability of the RNA-seq in this study.

Fig. 5.

Heatmap of DEGs related to disease resistance between the control (CK) and treatment (T) groups of Chinese cabbage at the initial infection stage. Green indicates significantly up-regulated genes; red indicates significantly down-regulated genes in the roots of T group. Arrow represents DEGs with more than twofold difference.

Fig. 6.

qRT-PCR analyzed of the differentially expressed disease resistance genes with more than twofold difference between control (CK) and treated (T, inoculated with P. brassicae) roots of Chinese cabbage at the initial infection stage. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3); *The significance at p ≤ 0.05, maintain as student’s t test.

DEGs related to POD in the infection process of P. brassicae

Based on the analysis of DEGs in RNA-seq, 17 DEGs related to POD were found in the process of P. brassicae infection in Chinese cabbage at the initial stage. NCBI comparison and bioinformatics induction showed that among POD related genes, eight were up-regulated and nine were down-regulated. Among them, the expression difference of three genes (Bra032809, Bra024972 and Bra022090) was exceeding and belonged to regulatory genes (Fig. 7a, Table S5). Their expression difference was verified by qRT-PCR (Fig. 7b). It indicated that POD-related genes were involved in the interaction process between P. brassicae and Chinese cabbage at the initial infection stage. To further understand the role of POD in the process of clubroot infection of Chinese cabbage roots, the content of POD in the roots of T and CK group roots at the initial infection stage was detected. The results showed that the POD value was significantly higher in P.brassicae infected T materials than that of uninfected CK materials (Fig. 7c).

Fig. 7.

POD-related (DEGs) between control (CK) and treated (T, inoculated with P. brassicae) roots of Chinese cabbage at the initial infection stage. (a) Heatmap of all significant POD-related DEGs. Green indicates significantly up-regulated genes; red indicates significantly down-regulated genes in the roots of T group. Arrow represents DEGs with more than a twofold difference. (b) qRT-PCR analysis for DEGs with more than twofold difference. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3); The significance at p ≤ 0.05, maintain as student’s t test. c, POD activity in CK and T groups. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3); *The significance at p ≤ 0.05, maintain as student’s t test.

DEGs related to SA and JA signaling induced by P. brassicae infection

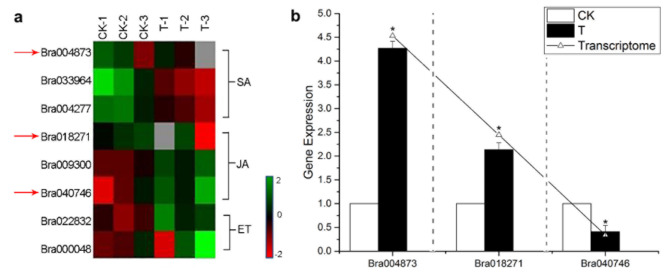

SA and JA/ET signal transduction pathways as plant hormone pathways are related to disease resistance. In this study, RNA-seq analysis found three SA-related, three JA-related and two ET-related DEGs. Most of these DEGs were down-regulated in the process of P. brassicae infection to Chinese cabbage at the initial stage. Among them, DEGs with expression difference exceeding twice include one of SA pathway gene (Bra004873) and two of JA pathway genes, (Bra018271 and Bra040746) (Fig. 8a, Table S6). Otherwise, two of ET-related genes were without significant difference (Fig. 8a). These results of DEGs with expression difference exceeding twice were validated by qRT-PCR (Fig. 8b).

Fig. 8.

DEGs of SA and JA/ET signaling pathway between the control group (CK) and treatment group (T, inoculated with P. brassicae) of Chinese cabbage at the initial infection stage. (a) Heatmap of all significant DEGs of SA and JA/ET signaling. Green indicates significantly up-regulated genes; red indicates significantly down-regulated genes in the roots of T group. Arrow represents DEGs with more than a twofold difference. (b) qRT-PCR analysis for DEGs more than twofold. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3); *The significance at p ≤ 0.05, maintain as student’s t test.

Discussion

The infection of P. brassicae was related to the concentration and infection time of P. brassicae. To obtained the DEGs at the initial infection stage of P. brassicae infection, it is important to find the earliest period of infection and the optimal concentration of P. brassicae16. In our previous studies, the root hair infection stage occurred over approximately seven days, and the cortical infection happened over approximately 14 days after inoculation with of P. brassicae34. In this study, it was found that 1 × 107 spores/mL of P. brassicae was the optimal concentration with the shortest primary infection period of eight days (Fig. 1; Table 1). Zoospores swimming to and infecting root hairs was happened in the primary infection6. So, the primary infection period of root hairs in Chinese cabbage should be the 7-8th days after inoculation with 1 × 107 spores/mL of P. brassicae. The timing of initial infection may change with changes in spore concentration and environment.

Plants themselves generate effective mechanisms to recognize and respond to invasions by pathogens. Plant resistance gene analogs (RGAS), as resistance candidate genes (R genes) with conserved domains and motifs, play a special role in pathogen resistance35 and stress resistance in Chinese cabbage36. Although there has been transcriptome analysis of Chinese cabbage during different stages of P. brassicae infection by some studies28,36, identifying the DEGs at the initial infection stage when Chinese cabbage response to P. brassicae infection represents a major breakthrough to understanding their interactions. In this study, 826 down-regulated and 552 up-regulated DEGs were obtained in Chinese cabbage infected by P. brassicae at primary stage using RNA-seq. A total of 656 DEGs were annotated by GO enrichment analysis, and a total of 890 DEGs were assigned to 116 KEGG pathways (Fig. 4).

Disease-resistance related genes pathogenesis-related proteins play crucial role in plant defense against outside pathogens23,35. One of the features of plant defense response is the specific induction of PR protein in pathological or related situations37. In B. napus, PR genes (PR1, PR2, and PR4) were consistently up-regulated during infection by P. brassicae27,38. Calcium binding genes positively regulate the disease resistance of Chinese cabbage39, while autophagy related genes may play a role in delaying cell death and limiting cell necrosis when pathogens infect host crops. Chitinase was the main component of the cell wall of Brassica and could resist the invasion of pathogens. Chitinases-related genes were induced in the process of P. brassica infection1,40. In our results, some resistance-related DEGs were found to have significant changes after inoculation with P. brassicae, such as disease resistance genes with the structure of NBS-LRR, PR protein genes, autophagy-related genes, Ca2+ binding genes and chitinases-related genes (Fig. 5; Table S4). Among them, Bra019410 as one of disease resistance genes with the structure of NBS-LRR has been confirmed to play a positive regulatory role in the resistance of Chinese cabbage to P. brassicae infection41.These results suggest that those resistance-related DEGs were involved in the clubroot at the initial infection stage of infection by P. brassicae. Further verifying other DEGs should provide key clue for to understanding their interactions between Chinese cabbage and P. brassicae.

In plants, POD has many different physiological functions in most animals and plants42. The infection process of P. brassicae to Chinese cabbage is more complicated43. Study showed that the resistant genotype has higher antioxidant ability than susceptible rapeseed37,44. In our study, among 17 DEGs related to POD, three genes (Bra032809, Bra024972 and Bra022090) were up-regulated more than twofold after being primary infected by P. brassicae (Fig. 7a, Table S5), and moreover the POD value of root significantly induced by the primary infection of P. brassicae (Fig. 7c). An increase in POD activity leads to an increase in phenol oxide content in plants45, which in turn acts to inhibit the synthesis of pathogenic cell wall enzymes46. It speculated that P. brassicae infection induces the oxidative burst pathway, and the increase of POD value can improve the resistance of Chinese cabbage to P. brassicae.

SA is an important regulator to trigger immune responses. Previous studies have shown that when plants are invaded by pathogens, the content of SA in host plants increases significantly, and the genes encoding several PRPs are activated through SA biosynthesis pathway, thus enhancing the resistance of plants to pathogens27,47. In Brassica, several studies indicated that the genes related to disease-resistance, chitinase synthesis, oxidative stress, SA signal transduction3,28. In this study, SA-related gene (Bra004873) was up-regulated 4.5-fold in the infection process (Fig. 8a, Table S6). Several studies showed that P. brassicae may induce SA signaling pathway in plants38,48,49. Both morphological aberrations and altered susceptibility to powdery mildews of rop6 (DN) plants are caused by perturbations that are independent the SA-related responses50. These perturbations uncouple SA-dependent defense signaling from disease resistance execution. P. brassicae induced the up-regulated expression of SA-related genes, which indicated that P. brassicae stimulated plants to use SA signaling response to fight infection.

The plant disease resistance pathway mediated by JA signal transduction pathway has two branches. One branch is related to ET mediated disease resistance pathway to resist pathogen infection through ET response factor pathway, and the other branch is inversely related to SA pathway51. Some studies have shown that both SA and JA signals can play a role in partial inhibition of clubroot development in compatible interactions between Arabidopsis and P. brassicae52. Nitschke et al. found that activation of the JA pathway and accumulation of JA metabolites are critical for inducing cell death53. JA can modulate the activity of stress enzymes to ensure maximum protection of plants. In this study, two JA-related genes (Bra018271 and Bra040746) were significantly expression changed by the primary infection of P. brassicae (Fig. 8a, Table S6). These results indicated that P. brassicae also stimulated plants to use JA signaling response to fight infection.

Conclusions

The primary infection period of root hairs in Chinese cabbage should be the 7-8th days after inoculation with 1 × 107 spores/mL of P. brassicae. 826 down-regulated and 552 up-regulated DEGs were obtained in Chinese cabbage infected by P. brassicae at primary stage using RNA-seq. Some resistance-related DEGs were found to have significant changes after inoculation with P. brassicae, such as disease resistance genes with the structure of NBS-LRR, PR protein genes, autophagy-related genes, Ca2+ binding genes and chitinases-related genes. POD/SA/JA-related gene and the contents of POD were significantly changed by the primary infection of P. brassicae. Based upon above mentioned pathways and genes regulating, we proposed a simplified schematic diagram to explore the resistance response at the initial stage of P. brassicae infection (Fig. 9). Our results could provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying of resistance to P. brassicae infection at the initial stage.

Fig. 9.

A simplified schematic diagram of the resistance response of Chinese cabbage at the initial infection stage by P. brassicae.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

RJ,HW and JZ; Data curation: RJ and YW; Methodology: RJ and WG; Formal analysis: YW and XW; Investigation: JZ,HW and JZ; Visualization: JZ; Writing-original draft preparation: HW, JZ and YW; Writing review and editing: HW, BF and RJ; Funding acquisition: RJ; Supervision: RJ.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 31972412; 32272717] and the Shenyang Science and Technology Bureau [grant number 22-319-2-05].

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and within its supplementary data. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Huihui Wang, Jing Zhang and Yilian Wang.

References

- 1.Chen, J., Piao, Y., Liu, Y., Li, X. & Piao, Z. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of chitinase gene family in Brassica rapa reveals its role in clubroot resistance. Plant Sci.270, 257–267. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.02.017 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhering, A. D. S., Carmo, Matos, M. G. F. & Lima, T. S. A. & do Amaral Sobrinho, N. M. B. Soil factors related to the severity of clubroot in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil. Plant Dis.101, 1345–1353. 10.1094/pdis-07-16-1024-sr (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galindo-González, L., Manolii, V., Hwang, S. F. & Strelkov, S. E. Response of Brassica napus to Plasmodiophora brassicae involves salicylic acid-mediated immunity: An RNA-Seq-based study. Front. Plant Sci.11, 1025. 10.3389/fpls.2020.01025 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ingram, D. S. & Tommerup, I. C. The life history of Plasmodiophora brassicae Woron. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 180, 103–112, doi: (1997). 10.1098/rspb.1972.0008

- 5.Naiki, T. & Dixon, G. R. The effects of chemicals on developmental stages of Plasmodiophora brassicae (clubroot). Plant Pathol.36, 316–327. 10.1111/j.1365-3059.1987.tb02238.x (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kageyama, K. & Asano, T. Life cycle of Plasmodiophora brassicae. J. Plant Growth Regul.28, 203–211. 10.1007/s00344-009-9101-z (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang, S. F., Howard, R. J., Strelkov, S. E., Gossen, B. D. & Peng, G. Management of clubroot (Plasmodiophora brassicae) on canola (Brassica napus) in western Canada. Can. J. Plant Pathol.36, 49–65 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan, Y. et al. Transcriptome and coexpression network analyses reveal hub genes in Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis) during different stages of Plasmodiophora brassicae infection. Front. Plant Sci.12, 650252. 10.3389/fpls.2021.650252 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng, J., Xiao, Q., Hwang, S. F., Strelkov, S. E. & Gossen, B. D. Infection of canola by secondary zoospores of Plasmodiophora brassicae produced on a nonhost. Eur. J. Plant Pathol.132, 309–315. 10.1007/s10658-011-9875-2 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buczacki, S. et al. Study of physiologic specialization in Plasmodiophora brassicae: Proposals for attempted rationalization through an international approach. Trans. Br. Mycol. soc.65, 295–303 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lv, M. et al. An improved technique for isolation and characterization of single-spore isolates of Plasmodiophora brassicae. Plant Dis.105, 3932–3938. 10.1094/pdis-03-21-0480-re (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xue, S., Cao, T., Howard, R. J., Hwang, S. F. & Strelkov, S. E. Isolation and variation in virulence of single-spore Isolatesof Plasmodiophora brassicae from Canada. Plant Dis.92, 456–462. 10.1094/PDIS-92-3-0456 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, L. et al. A genome-wide association study reveals new loci for resistance to clubroot disease in Brassica napus. Front. Plant Sci.7, 1483. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01483 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao, T. et al. Effect of canola (Brassica napus) cultivar rotation on Plasmodiophora brassicae pathotype composition. Can. J. Plant Sci.100, 218–225. 10.1139/cjps-2019-0126 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han, X. et al. Plasmodiophora brassicae in Yunnan and its resistant sources in Chinese cabbage. Int. J. Agric. Biol.25, 805–812. 10.17957/IJAB/15.1732 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo, H., Chen, G., Liu, C., Huang, Y. & Xiao, C. An improved culture solution technique for Plasmodiophora brassicae infection and the dynamic infection in the root hair. Australas. Plant Pathol.43, 53–60. 10.1007/s13313-013-0240-0 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arif, S. et al. Exogenous inoculation of endophytic bacterium Bacillus cereus suppresses clubroot (Plasmodiophora brassicae) occurrence in pak choi (Brassicacampestris sp. chinensis L). Planta. 253, 25. 10.1007/s00425-020-03546-4 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li, J., Huang, T., Lu, J., Xu, X. & Zhang, W. Metabonomic profiling of clubroot-susceptible and clubroot-resistant radish and the assessment of disease-resistant metabolites. Front. Plant Sci.13, 1037633. 10.3389/fpls.2022.1037633 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rolfe, S. A. et al. The compact genome of the plant pathogen Plasmodiophora brassicae is adapted to intracellular interactions with host Brassicaspp. BMC Genom.1710.1186/s12864-016-2597-2 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Vlot, A. C. et al. Systemic propagation of immunity in plants. New Phytol.229, 1234–1250. 10.1111/nph.16953 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romera, F. J. et al. Induced systemic resistance (ISR) and Fe deficiency responses in dicot plants. Front. Plant. Sci.10, 287. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00287 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glazebrook, J. Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol.43, 205–227. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.135923 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang, Y. X., Ahammed, G. J., Wu, C., Fan, S. Y. & Zhou, Y. H. Crosstalk among jasmonate, salicylate and ethylene signaling pathways in plant disease and immune responses. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci.16, 450–461. 10.2174/1389203716666150330141638 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leon Reyes, A. et al. Salicylate-mediated suppression of jasmonate-responsive gene expression in Arabidopsis is targeted downstream of the jasmonate biosynthesis pathway. Planta232, 1423–1432. 10.1007/s00425-010-1265-z (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Y, W., H, H. K. & S, M. & Effects of salinity on endogenous ABA, IAA, JA, AND SA in Iris hexagona. J. Chem. Ecol.27, 327–342 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plieth, C. & Vollbehr, S. Calcium promotes activity and confers heat stability on plant peroxidases. Plant Signal. Behav.7, 650–660. 10.4161/psb.20065 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao, Y. et al. Transcriptome analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana in response to Plasmodiophora brassicae during early infection. Front. Microbiol.8, 673. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00673 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jia, H. et al. Root RNA-seq analysis reveals a distinct transcriptome landscape between clubroot-susceptible and clubroot-resistant Chinese cabbage lines after Plasmodiophora brassicae infection. Plant Soil.421, 93–105. 10.1007/s11104-017-3432-5 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang, X. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis between Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) and wild cabbage (Brassica Macrocarpa Guss.) In response to Plasmodiophora brassicae during different infection stages. Front. Plant. Sci.7, 1929. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01929 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, L., Long, Y., Li, H. & Wu, X. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals key pathways and hub genes in rapeseed during the early stage of Plasmodiophora brassicae infection. Front. Genet.10, 1275. 10.3389/fgene.2019.01275 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gene Ontology Consortium: going forward. Nucleic Acids Res.43, D1049–1056. 10.1093/nar/gku1179 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Masoudi-Nejad, A., Goto, S., Endo, T. R. & Kanehisa, M. KEGG bioinformatics resource for plant genomics research. Methods Mol. Biol.406, 437–458. 10.1007/978-1-59745-535-0_21 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods25, 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji, R. et al. Infection of Plasmodiophora brassicae in Chinese cabbage. Genet. Mol. Res.13, 10976–10982. 10.4238/2014.December.19.20 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sekhwal, M. K. et al. Disease resistance gene analogs (RGAs) in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci.16, 19248–19290. 10.3390/ijms160819248 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan, G. et al. Genome-wide analysis and expression profiles of glyoxalase gene families in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L). PLoS One13, e0191159. 10.1371/journal.pone.0191159 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Su, H. et al. Comprehensive analysis of the full-length transcripts and alternative splicing involved in clubroot resistance in Chinese cabbage. J. Integr. Agric.22, 3284–3295. 10.1016/j.jia.2022.09.014 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen, J., Pang, W., Chen, B., Zhang, C. & Piao, Z. Transcriptome analysis of Brassica rapa near-isogenic lines carrying clubroot-resistant and -susceptible alleles in response to Plasmodiophora brassicae during early infection. Front. Plant. Sci.6, 1183. 10.3389/fpls.2015.01183 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ji, R. et al. Proteomic analysis of the interaction between Plasmodiophora brassicae and Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. Pekinensis) at the initial infection stage. Sci. Hortic.233, 386–393. 10.1016/J.SCIENTA.2018.02.006 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nie, S., Zhang, M. & Zhang, L. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of calmodulin-like (CML) genes in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). BMC Genom.18, 842. 10.1186/s12864-017-4240-2 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ge, W. et al. Analysis of the role of BrRPP1 gene in Chinese cabbage infected by Plasmodiophora brassicae. Front. Plant Sci.1410.3389/fpls.2023.1082395 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Su, Y. et al. Identification, phylogeny, and transcript of chitinase family genes in sugarcane. Sci. Rep.5, 10708. 10.1038/srep10708 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dong, R. et al. Transcriptome analyses reveal candidate pod shattering-associated genes involved in the pod ventral sutures of common vetch (Vicia sativa L). Front. Plant. Sci.8, 649. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00649 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwelm, A. et al. The Plasmodiophora brassicae genome reveals insights in its life cycle and ancestry of chitin synthases. Sci. Rep.5, 11153. 10.1038/srep11153 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mei, J. et al. Understanding the resistance mechanism in Brassica napus to clubroot caused by Plasmodiophora brassicae. Phytopathology. 109, 810–818. 10.1094/phyto-06-18-0213-r (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aghaie, P., Tafreshi, S. A. H., Ebrahimi, M. A. & Haerinasab, M. Tolerance evaluation and clustering of fourteen tomato cultivars grown under mild and severe drought conditions. Sci. Hortic.232, 1–12. 10.1016/j.scienta.2017.12.041 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kohler, A. C., Simmons, B. A. & Sale, K. L. Structure-based engineering of a plant-fungal hybrid peroxidase for enhanced temperature and pH tolerance. Cell Chem. Biol.25, 974–983e973. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.04.014 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lahlali, R. et al. Heteroconium chaetospira induces resistance to clubroot via upregulation of host genes involved in jasmonic acid, ethylene, and auxin biosynthesis. PLoS One9, e94144. 10.1371/journal.pone.0094144 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ji, R. et al. The salicylic acid signaling pathway plays an important role in the resistant process of Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis to Plasmodiophora brassicae Woronin. J. Plant. Growth Regul.40, 1–18. 10.1007/s00344-020-10105-4 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poraty-Gavra, L. et al. The Arabidopsis rho of plants GTPase AtROP6 functions in developmental and pathogen response pathways. Plant physiol.161, 1172–1188. 10.1104/pp.112.213165 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lorenzo, O., Piqueras, R., Sánchez-Serrano, J. J. & Solano, R. ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1 integrates signals from ethylene and jasmonate pathways in plant defense. Plant Cell15, 165–178. 10.1105/tpc.007468 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lemarié, S. et al. Both the jasmonic acid and the salicylic acid pathways contribute to resistance to the biotrophic clubroot agent Plasmodiophora brassicae in Arabidopsis. Plant. Cell Physiol.56, 2158–2168. 10.1093/pcp/pcv127 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nitschke, S. et al. Circadian stress regimes affect the circadian clock and cause jasmonic acid-dependent cell death in cytokinin-deficient Arabidopsis plants. Plant Cell28, 1616–1639. 10.1105/tpc.16.00016 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and within its supplementary data. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.