Abstract

Background

Alcohol use disorders (AUD) occur frequently in sexual minority (SM) adults (identifying as gay, lesbian or bisexual). Age-specific prevalence estimates, particularly during middle and older ages, remain obscure. With questions for sexual identity recently included in the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), increased precision is possible. This study investigates the age-specific estimate for AUD in sexual minority versus sexual majority adults.

Methods

Analysis of the 2015–2017 NSDUH, ages 18-years-and-older (N=128,740). We estimate age-specific, 12-month DSM-IV AUD prevalence and adjusted prevalence ratios (via Poisson regression) by sexual identity. Adjusted models control for demographic, social, and mental health variables. Post-hoc analysis included age-specific estimates after redefining SM to include any same-sex attraction.

Results

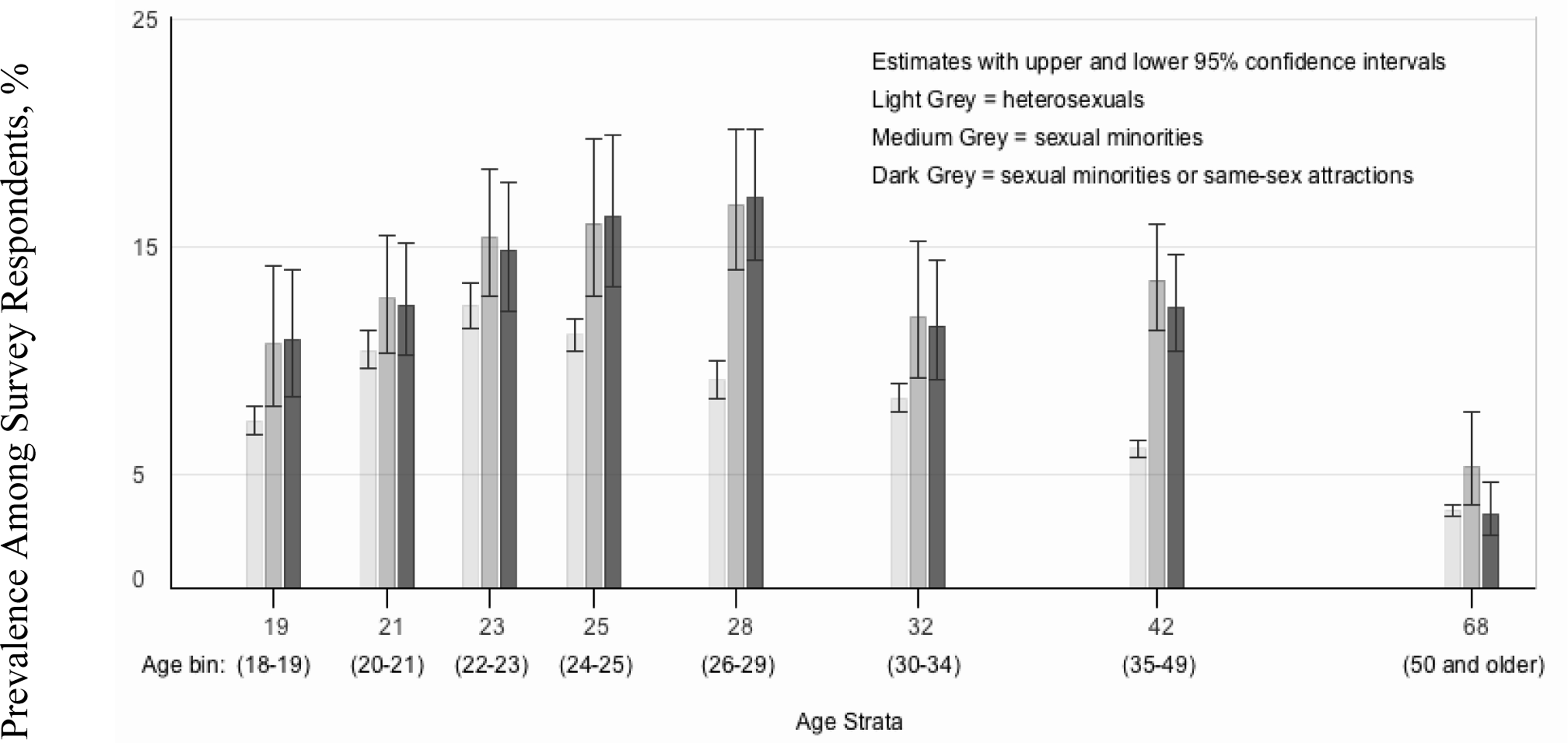

The age-specific estimate showed peak AUD prevalence at age ~28 for all SMs, compared to age ~23 for heterosexuals. By subgroup, gay men ages 18–23, had the highest AUD prevalence at 18.8% (CI: 13.5, 25.5). Bisexual women ages 24–29 had the highest disparity, a prevalence ratio (reference heterosexual women) of 2.59 (CI: 2.15, 3.13). Above age 50, the definition of SM is salient: in this age group, prevalence of AUD converges for heterosexuals and SMs that include individuals with any same-sex attraction.

Conclusion

In this largest study to date, SMs have a high prevalence of AUD. A disparity in the age-by-age estimates emerges by age 25 when AUD occurrence declines in heterosexuals but increases in SMs. A prevalence disparity occurs with each successive age strata, but by age 50-and-older, the difference is null.

Keywords: Sexual minorities (SMs), Alcohol use disorders, Psychiatric disorders, Gay/lesbian, Bisexual, Disparities

Introduction |

Youth who identify as gay, lesbian or bisexual (sexual minorities, SMs) appear to have an increased risk of heavy alcohol use and alcohol use disorder (AUD) relative to heterosexuals (Brewster and Tillman, 2012; Kerridge et al., 2017; McCabe et al., 2009; Talley et al., 2014), yet there are few studies of age-specific disparities. Most studies on AUD among SMs typically bin participants into large age groups or only include age as a control when estimating prevalence ratios relative to heterosexuals. Prevalence of AUD above age 50 is particularly unclear due to a paucity of nationally-representative data (Yarns et al., 2016).

National surveys have not included questions on sexual identity (SI) until recently. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) first added questions about SI and sexual attraction in 2015. Prior studies of AUD in SMs have been based on 2012–2013 data from National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III), which included a population sample of ~35,000 participants. With three replicates of the NSDUH, 2015–2017, ~125,000 individuals have since answered questions about sexual orientation and AUD, enabling increased precision for estimates stratified by age, sex, and SI.

NESARC-III enabled the following studies of past-12-month prevalence of AUD within sexual minority subgroups, by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Version 5 (DSM-5): First, examining the 18-and-older age group, Kerridge et al. (2017), found a prevalence of ~25% among SMs compared to ~10% among heterosexual women and ~17% of heterosexual men. Bisexual men had the highest AUD prevalence of any subgroup at ~31%. In another study analyzing the association of SM identity with AUD prevalence, Rice et al. (2019) found fairly stable AUD disparities across all ages, with possible increases noted at ages ~18 and ~40.

With data from the 2015–2016 NSDUH surveys, Schuler et al. (2018) revealed that past-12-month prevalence of substance use disorder (SUD) increased across three age groups, 18–25, 26–34, and 35–49 for gay males, with a ~33% prevalence in the oldest age group. 35–49-year-olds also had the highest SUD prevalence odds ratio at 2.74 (CI: 1.78, 4.22; SMs relative to sexual majority individuals of the same sex). NSDUH continues to use DSM-IV criteria with assurances that SUD prevalence estimates based on DSM-IV versus DSM-5 should differ by ~3% or less (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016).

Maladaptive coping with alcohol is expected to be less common in older ages for all subgroups based on a life-course framework that links increased resiliency with older age, (Masten, 2001). Minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) has been posited to explain unexpected AUD disparities by SI (Dermody, 2018). SM discriminatory experiences decline steadily after peaking at age ~18 (Evans-Polce et al., 2019), suggesting that AUD disparities should narrow with age.

Discriminatory experiences may not be the only factor associated with AUD: life-course events such as marriage and child-rearing— protective factors more common among heterosexuals— may partially explain SI disparities in AUD. Because these experiences occur in mid-adulthood, a corresponding mid-adult peak in SM AUD disparities could be expected. The recent legalization of same-sex marriage may have contributed to a cohort phenomenon affecting age-specific patterns.

In this study, we analyze the NSDUH’s 2015–2017 survey to obtain current, precise estimates of DSM-IV AUD by age, sex and SI for the United States (US) population. First, we pool all SM subgroups, enabling a high-resolution view of age-specific estimates in AUD prevalence for both SM and heterosexual individuals. Then we examine key developmental age groups, 18–23, 24–29, and 30–49, with stratification by sex and SI subgroups. Hypothesized mechanisms for age-related patterns— minority stress, social support, and age-associated resiliency— motivate our inquiry, but we limited the scope of this short communication to prevalence estimates and adjusted prevalence ratios that control for social and mental health factors.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population and sample

The study design is an epidemiological cross-sectional survey conducted for the NSDUH by the Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, a subdivision of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The study population includes non-institutionalized, US civilian residents (including the District of Columbia), ages 12-years-and-older. The average annual survey response rate was 68.4% after screenings for eligible households. Sampled dwellings include households and group quarters such as dormitories and homeless shelters. NSDUH staff follow institutional review board-approved protocols, ensuring confidentiality with use of audio computer-assisted self-interviews. All survey respondents gave informed consent and received $30 compensation (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018).

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. SM status:

NSDUH asked participants who were 18-years-and-older at the time of the survey about SI: “Which one of the following do you consider yourself to be?” Responses include: 1) “heterosexual, 2) gay or lesbian, 3) bisexual or 4) I don’t know.” Sexual attraction was assessed with: “People are different in their sexual attraction to other people. Which statement best describes your feelings?” Responses include: “1) I am only attracted to the opposite sex. 2) I am mostly attracted to opposite sex. 3) I am equally attracted to males and females. 4) I am mostly attracted to same sex. 5) I am only attracted to same sex. 6) I am unsure. 7) Don’t know.” Same-sex sexual attraction has been viewed as a distinct construct (Bauer and Brennan, 2013); thus, we initially focused on SI. Research has shown higher prevalence of AUD in gay/lesbian/bisexual identifying individuals compared to those who only report same-sex attraction (McCabe et al., 2009). For a post-hoc analysis, we also estimated age-by-age AUD prevalence by defining SMs more broadly inclusive of SI or any same-sex attraction.

2.2.2. Alcohol Use Disorder:

AUD status was assessed for participants who used alcohol within the past year with standardized items corresponding to the DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2003). For these variables— dependence or abuse— any occurrence within 12 months prior to the assessment counted as a positive case.

2.2.3. Demographic variables:

We include sex (self-reported male or female), age (at some ages, NSDUH bins ages to prevent re-identification of participants) and race/ethnicity categorized as 1) White, 2) Black or African-American, 3) American-Indian/Alaska-Native, 4) Native-Hawaiian/other Pacific-Islander, 5) Asian, or 6) non-Hispanic multiple races or 7) Hispanic. We also included measures of education (high school or less, some college, college graduate), employment status (full time, part time, unemployed, ‘other’), and income (<$20,000, $20,000-$49,999, $50,000-$75,000, >$75,000).

2.3. Statistical analysis

We aggregated the 2015–2017 NSDUH data before estimating the prevalence of AUD for heterosexuals and three categories of SI: 1) gay/lesbian, 2) bisexual, and 3) SMs (the first two categories combined). We omitted those who reported ‘I don’t know’ and missing data. First, we estimated AUD prevalence by the smallest age categories available within NSDUH pooling by sex and SM subgroups to increase the resolution of the age-by-age estimates. Next we made larger age groups—18–23, 24–29, and 30–49— that segment key developmental periods (e.g. age 21, peak age of alcohol initiation). The 50+ age group had insufficient cases (n=37) to include. By sex and SM subgroup, we estimated AUD prevalence and adjusted prevalence ratios using Poisson regression. Adjusted models included demographic, social, and mental health variables as described in the table caption. Analyses accounted for NSDUH survey design; per NSDUH guidelines, original sampling weights were divided by three to account for pooling across 2015 to 2017. For all analyses, Stata software (Version 14.1; Stata Corp., 2015) was used, with ‘svyset’ and ‘subpop’ procedures.

Table.

Weighted Prevalence and Adjusted Prevalence Ratio of an Alcohol Use Disorder within 12 months of the Assessment. Estimates Stratified by Age, Sex, and Sexual Identity, with 95% Confidence Interval Included in Parentheses. National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 2015–2017 (N=128,740).

| Weighted Prevalence (%) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 18–23 | |||||

| Heterosexual | 10.8 (10.1, 11.5) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| SM | 16.2 (12.9, 20.1) | 1.45 (1.17, 1.79) | 1.42 (1.14, 1.75) | 1.22 (0.98, 1.52) | 1.21 (1.00, 1.46) | |

| Gay | 18.8 (13.5, 25.5) | 1.62 (1.19, 2.20) | 1.58 (1.16, 2.14) | 1.41 (1.05, 1.89) | 1.26 (0.94, 1.69) | |

| Bisexual | 14.2 (10.3, 19.3) | 1.30 (0.94, 1.79) | 1.28 (0.93, 1.76) | 1.07 (0.76, 1.51) | 1.15 (0.84, 1.58) | |

| 24–29 | ||||||

| Heterosexual | 12.7 (11.9, 13.6) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| SM | 16.0 (12.5, 20.2) | 1.26 (0.98, 1.63) | 1.16 (0.89, 1.50) | 1.13 (0.87, 1.46) | 1.11 (0.87, 1.43) | |

| Gay | 18.2 (13.7, 23.8) | 1.46 (1.09, 1.96) | 1.31 (0.97, 1.77) | 1.35 (1.00, 1.81) | 1.26 (0.94, 1.68) | |

| Bisexual | 13.0 (9.30, 17.9) | 1.02 (0.73, 1.41) | 0.95 (0.69, 1.32) | 0.86 (0.62, 1.20) | 0.92 (0.66, 1.28) | |

| 30–49 | ||||||

| Heterosexual | 8.9 (8.40, 9.50) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| SM | 15.7 (12.3, 19.7) | 1.69 (1.34, 2.15) | 1.41 (1.10, 1.80) | 1.42 (1.12, 1.82) | 1.32 (1.03, 1.68) | |

| Gay | 16.4 (12.0, 22.1) | 1.77 (1.29, 2.42) | 1.37 (0.98, 1.91) | 1.49 (1.10, 2.04) | 1.32 (0.97, 1.81) | |

| Bisexual | 14.6 (10.0, 20.7) | 1.58 (1.11, 2.25) | 1.47 (1.03, 2.09) | 1.32 (0.92, 1.90) | 1.31 (0.91, 1.88) | |

| Females | 18–23 | |||||

| Heterosexual | 9.2 (8.60, 9.80) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| SM | 11.6 (9.90, 13.5) | 1.24 (1.04, 1.48) | 1.20 (1.01, 1.43) | 0.98 (0.82, 1.17) | 0.86 (0.72, 1.03) | |

| Lesbian | 9.50 (6.30, 14.1) | 1.03 (0.68, 1.57) | 0.96 (0.63, 1.46) | 0.87 (0.57, 1.32) | 0.72 (0.47, 1.12) | |

| Bisexual | 12.0 (10.1, 14.1) | 1.28 (1.07, 1.55) | 1.25 (1.04, 1.50) | 1.00 (0.83, 1.21) | 0.89 (0.74, 1.07) | |

| 24–29 | ||||||

| Heterosexual | 6.7 (6.10, 7.30) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| SM | 16.8 (14.4, 19.5) | 2.56 (2.14, 3.07) | 2.26 (1.89, 2.69) | 2.01 (1.67, 2.42) | 1.79 (1.49, 2.14) | |

| Lesbian | 15.4 (10.4, 22.2) | 2.44 (1.61, 3.69) | 1.97 (1.35, 2.88) | 2.14 (1.47, 3.13) | 1.90 (1.24, 2.91) | |

| Bisexual | 17.2 (14.5, 20.2) | 2.59 (2.15, 3.13) | 2.34 (1.95, 2.81) | 1.98 (1.63, 2.41) | 1.76 (1.46, 2.13) | |

| 30–49 | ||||||

| Heterosexual | 4.4 (4.0, 4.80) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| SM | 11.2 (9.1, 13.7) | 2.40 (1.91, 3.02) | 2.02 (1.60, 2.56) | 1.84 (1.45, 2.32) | 1.54 (1.21, 1.98) | |

| Lesbian | 9.3 (6.3, 13.6) | 1.97 (1.32, 2.95) | 1.54 (1.02, 2.32) | 1.70 (1.15, 2.53) | 1.44 (0.96, 2.18) | |

| Bisexual | 12.0 (9.7, 14.8) | 2.58 (2.05, 3.26) | 2.25 (1.78, 2.85) | 1.88 (1.50, 2.37) | 1.58 (1.23, 2.03) | |

Note: Alcohol use disorder is 12-month history of alcohol abuse or dependence according to DSM-IV case definition. The weighted prevalence estimates rely on a weighting algorithm to ensure nationally representative estimates.

Prevalence ratio estimates use Poisson regression for each outcome with model adjustments. Bolded numbers are statistically significant based on a t-test of the coefficient with alpha at 0.05 and p-value less than 0.05. All models contain adjustment for demographic variables (age, education, employment status, income, race/ethnicity). Model adjustments are as follows:

Model 1) Only demographic variables, as described above.

Model 2) Marriage, or children < 17 years old in household.

Model 3) Moderate or serious mental illness as estimated by NSDUH based on several survey responses.

Model 4) Past 12-month history of cannabis or other internationally regulated drug use or disorder, or nicotine dependence in past 30 days.

3. Results

Sample sizes of ages-18-and-older ranged from 42,554–43,561 for 2015–2017 (total N=128,740), including 1,065 SMs with AUD. The Figure illustrates age-by-age estimates in AUD, which decrease steadily across age strata for both SMs and heterosexuals after peaking in early adulthood. While these prevalence estimates are similar for SM and majority participants in young adulthood, a gap emerges due to successively lower AUD estimates among heterosexuals after age ~23. In contrast, for SMs, AUD prevalence is lower after age ~28, but plateaus from ages 32-to-42.

Figure.

12-Month Prevalence of Alcohol Use Disorders by Age Strata and Sexuality. National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2015–2017.

Note: The y-axis is the 12-month prevalence of alcohol dependence or abuse. Bars represent the estimated prevalence by sexual identity based on the pooled annual surveys from 2015–2017; horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence interval. The x-axis shows the average age of the participants (rounded to the nearest integer) within each age bin. The range of the age bin is shown in parentheses just below the average age. To represent the relative gaps between ages, we used a log scale for the x-axis, which compresses gaps at older ages in favor of increased resolution at younger ages. These estimates are based on numerators (unweighted counts of cases) above 100 in all age strata, except for 50 and older, in which case the numerator was 37. The estimates for heterosexuals compared to sexual minorities (medium grey) are significantly different for each age group, except for 20–21-year-olds, (based on a two-tailed z test for proportions with alpha at 0.05 and p-value is less than 0.05).

If an individual has same sex attractions, age may be associated with a tendency to identify as gay, lesbian or bisexual. Therefore, we also estimated the age-specific 12-month AUD prevalence using a broader definition of SM status: a report of any same-sex attraction or SM identity. These post-hoc estimates for AUD based on same-sex attraction are shown in the figure (dark grey). In all cases, confidence intervals broadly overlap with estimates based on the narrow definition of SM (only those who identify as gay/lesbian or bisexual).

The Table shows past-12-month AUD estimates stratified by sex and ages 18–23, 24–29, and 30–49-years. Gay men in the youngest age group (18–23) have the highest AUD prevalence of any subgroup at 18.8% (13.5%, 25.5%) compared to 10.8% (CI: 10.1%, 11.5%) among heterosexuals men of the same ages. Bisexual women, ages 24–29, had AUD prevalence of 17.2% (CI: 14.5%, 20.2%), compared to 6.7% (CI: 6.1%, 7.3%) among heterosexual women of the same ages. After controlling for possible demographic confounders, the prevalence ratio of these two subgroups (bisexual compared to heterosexual women) was 2.59 (2.15, 3.13).

Prevalence ratios are generally higher in the older two age strata, the 24–29, and 30–49-year-old and higher among women as compared to men. The table shows an attenuation of the prevalence ratio in model 2, 3, and 4, which were adjusted for marriage and children, mental illness, and cannabis/tobacco/illicit drug use or disorders, respectively. AUD may be directly related to facets of experience represented in these models, but an investigation of the temporal sequence of these variables relative to AUD is beyond the scope of this paper.

4. Discussion

The prevalence of recent AUD peaks at age ~23 for sexual majority individuals compared to age ~28 for SMs. We note that additional survey replicates are needed to determine any cohort or period effects. The disparity emerges from age ~25 to age ~50 with increases in AUD prevalence ratio seen especially among women and despite adjustment for many potentially confounding variables. After age 50, AUD prevalence for heterosexuals and SMs is very similar. In fact, if the more inclusive definition of an SM is used, (SM identity or any same-sex attraction), the null hypothesis of no AUD prevalence difference from heterosexuals cannot be rejected.

This study is limited by self-reported measures. The cross-sectional design warrants interpreting the age-by-age estimates cautiously given possible confounding by period or cohort effects. Furthermore, those with AUD may be more difficult to contact for study participation due to increased occurrence of severe health problems (Bolton and Sareen, 2011; Kerridge et al., 2017; Neumark et al., 2000). This ‘left truncation’ problem likely affects sexual majority and minority individuals similarly, however, due to the higher prevalence of AUD in SMs, a more substantial ‘cut’ may occur each year for SMs. This may explain converging estimates (seen after age 50) but not diverging estimates, with increases in AUD prevalence among SMs between 23–28 years.

Notwithstanding limitations, our study identifies key patterns of age-specific AUD prevalence worthy of further study. While evidence suggests that discriminatory experiences slowly decline after age 18 for SMs, increasing disparities at age 28 implicates other social determinates such as social support, family formation, and peer normative behavior. NSDUH has no measure of discrimination by SI, but facets of social determinates, such as marriage, seem feasible to study with the NSDUH.

Study strengths include its large, nationally-representative sample, and its more detailed age-by-age estimates. Our analysis examines two definitions of SM: 1) those who identify as an SM, and 2) those who meet the former definition or have any same-sex attraction. We find age-by-age estimates are not merely related to an age-specific preference for identifying as an SM given same-sex attractions.

5. Conclusion

With the inclusion of SI variables in major US surveys, we can now estimate age-specific AUD prevalence for SMs with new precision. A disparity emerges for SMs by age 25— that gap nearly closes in the 50-and-older group. Primary care doctors now routinely collect information about age, and increasingly, sexual identity. Identification of high risk subgroups using these variables could direct ‘personalized’ AUD prevention efforts.

Highlights.

Alcohol use disorder occurs more frequently in sexual minorities compared to heterosexuals.

This gap in prevalence occurs at nearly all ages, until after age 50, when disparities decline.

Alcohol use disorder prevalence peaks at age ~28 for sexual minorities.

For heterosexual individuals, that peak occurs at age ~23.

Acknowledgments:

The authors wish to acknowledge the project’s funding sources, which include the National Institute of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse training grant T32DA021129 [CLT] and R25DA030310 [RLP], The US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration created the NSDUH public use datasets utilized in this work. Additionally, we would like to thank Dr. James C. Anthony for his ongoing mentorship.

Role of the Funding Source:

RLP: R25DA030310. CLT: NIDA T32 DA021129. Funding source had no influence or involvement on the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Abbreviations:

- AUD

Alcohol use disorder

- CI

Confidence interval

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition

- NSDUH

National Surveys on Drug Use and Health

- SI

Sexual identity

- SUD

Substance use disorder

- SM

Sexual minority

- US

United States

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: N/A

Conflict of Interest: no conflict declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association., 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth ed., text revision. Arlington, Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR, Brennan DJ, 2013. The problem with “behavioral bisexuality”: assessing sexual orientation in survey research. J. Bisex. 13, 148–165. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton SL, Sareen J, 2011. Sexual orientation and its relation to mental disorders and suicide attempts: findings from a nationally representative sample. Can. J. Psychiatry. 56, 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster KL, Tillman KH, 2012. Sexual orientation and substance use among adolescents and young adults. Am. J. Public Health. 102, 1168–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018. 2015 National survey on drug use and health public use file codebook, Substance abuse and mental health services administration. Rockville, Maryland. https://samhda.s3-us-gov-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/field-uploads-protected/studies/NSDUH-2015/NSDUH-2015-datasets/NSDUH-2015-DS0001/NSDUH-2015-DS0001-info/NSDUH-2015-DS0001-info-codebook.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016. Impact of the DSM-IV to DSM-5 changes on the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Substance abuse and mental health services administration. Rockville, MD. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermody SS, 2018. Risk of polysubstance use among sexual minority and heterosexual youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 192, 38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Polce RJ, Veliz PT, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, McCabe SE, 2019. Associations between sexual orientation discrimination and substance use disorders: differences by age in US adults. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerridge BT, Pickering RP, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Chou SP, Zhang H, Jung J, Hasin DS, 2017. Prevalence, sociodemographic correlates and DSM-5 substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among sexual minorities in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 170, 82–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, 2001. Ordinary magic: resilience processes in development. Am. Psychol. 56, 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick WB, West BT, and Boyd CJ, 2009. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the united states. Addiction. 104, 1333–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, 2003. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 129, 674–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark YD, Van Etten ML, Anthony JC, 2000. “Alcohol dependence” and death: survival analysis of the Baltimore ECA sample from 1981 to 1995. Subst. Use Misuse. 35, 533–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice CE, Vasilenko SA, Fish JN, Lanza ST 2019. Sexual minority health disparities: an examination of age-related estimates across adulthood in a national cross-sectional sample. Ann Epidemiol. 19, 20–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler MS, Rice CE, Evans-Polce RJ, Collins RL, 2018. Disparities in substance use behaviors and disorders among adult sexual minorities by age, gender, and sexual identity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 189, 139–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley AE, Hughes TL, Aranda F, Birkett M, Marshal MP, 2014. Exploring alcohol-use behaviors among heterosexual and sexual minority adolescents: intersections with sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Am. J. Public Health. 104, 295–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarns BC, Abrams JM, Meeks TW, Sewell DD, 2016. The mental health of older lgbt adults. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 18, 60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]