Key Points

Question

What are the characteristics and outcomes for patients younger than 65 years who receive transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) compared with those aged 65 to 80 years?

Findings

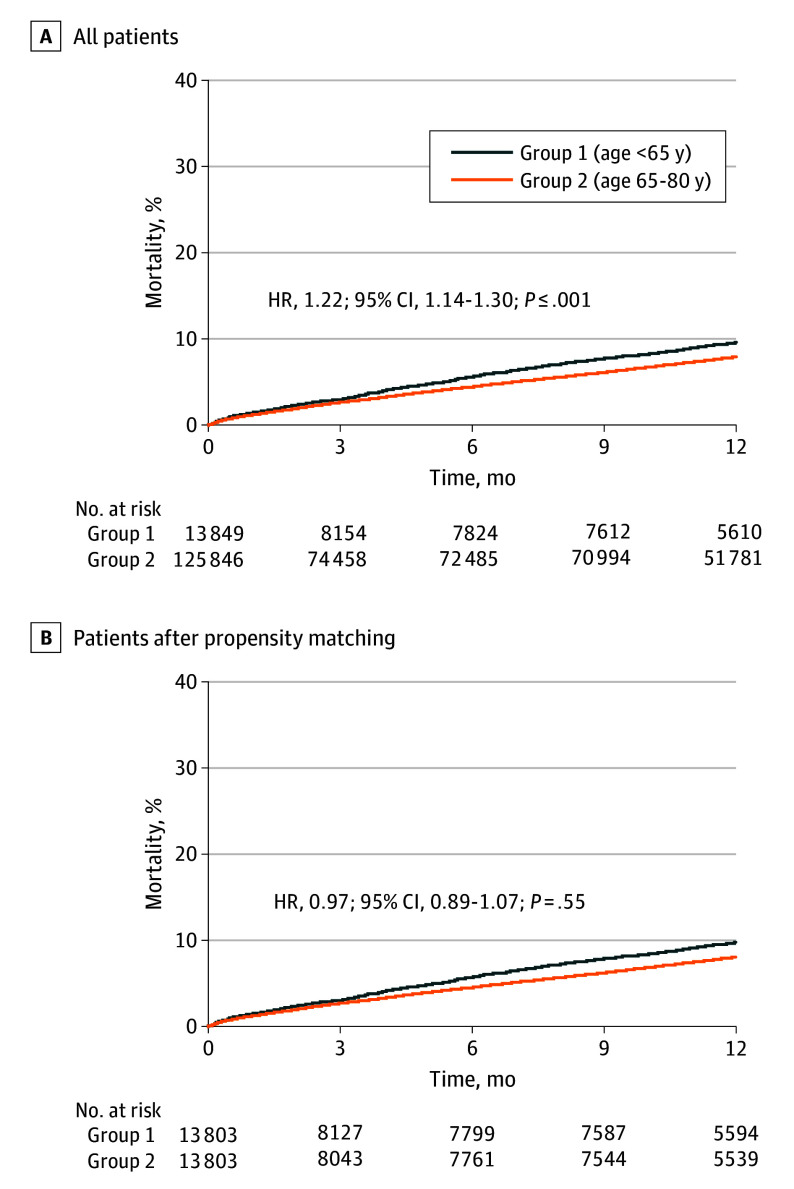

In this cohort study of 139 695 patients undergoing balloon-expandable valve (BEV) TAVR, patients younger than 65 years had a higher comorbidity burden and significantly higher all-cause mortality and readmission 1 year post-TAVR than patients aged 65 to 80 years.

Meaning

The findings suggest that patients younger than 65 years undergoing BEV TAVR in the US were at higher risk with greater likelihood for reduced longevity.

This cohort study assesses characteristics and outcomes of younger patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Abstract

Importance

Guidelines advise heart team assessment for all patients with aortic stenosis, with surgical aortic valve replacement recommended for patients younger than 65 years or with a life expectancy greater than 20 years. If bioprosthetic valves are selected, repeat procedures may be needed given limited durability of tissue valves; however, younger patients with aortic stenosis may have major comorbidities that can limit life expectancy, impacting decision-making.

Objective

To characterize patients younger than 65 years who received transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and compare their outcomes with patients aged 65 to 80 years.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective registry-based analysis used data on 139 695 patients from the Society for Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy (TVT) Registry, inclusive of patients 80 years and younger undergoing TAVR from August 2019 to September 2023.

Intervention

Balloon-expandable valve (BEV) TAVR with the SAPIEN family of devices.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Comorbidities (heart failure, coronary artery disease, dialysis, and others) and outcomes (death, stroke, and hospital readmission) of patients younger than 65 years compared to patients aged 65 to 80 years.

Results

In the years surveyed, 13 849 registry patients (5.7%) were younger than 65 years, 125 846 (52.1%) were aged 65 to 80 years, and 101 725 (42.1%) were 80 years and older. Among those younger than 65, the mean (SD) age was 59.7 (4.8) years, and 9068 of 13 849 patients (65.5%) were male. Among those aged 65 to 80 years, the mean (SD) age was 74.1 (4.2) years, and 77 817 of 125 843 patients (61.8%) were male. Those younger than 65 years were more likely to have a bicuspid aortic valve than those aged 65 to 80 years (3472/13 755 [25.2%] vs 9552/125 001 [7.6%], respectively; P < .001). They were more likely to have congestive heart failure, chronic lung disease, diabetes, immunocompromise, and end stage kidney disease receiving dialysis. Patients younger than 65 years had worse baseline quality of life (mean [SD] Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire score, 47.7 [26.3] vs 52.9 [25.8], respectively; P < .001) and mean (SD) gait speed (5-meter walk test, 6.6 [5.8] seconds vs 7.0 [4.9] seconds, respectively; P < .001) than those aged 65 to 80 years. At 1 year, patients younger than 65 years had significantly higher readmission rates (2740 [28.2%] vs 23 178 [26.1%]; P < .001) and all-cause mortality (908 [9.9%] vs 6877 [8.2%]; P < .001) than older patients. When propensity matched, younger patients still had higher 1-year readmission rates (2732 [28.2%] vs 2589 [26.8%]; P < .03) with similar mortality to their older counterparts (905 [9.9%] vs 827 [10.1%]; P = .55).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among US patients receiving BEV TAVR for severe aortic stenosis in the low–surgical risk era, those younger than 65 years represent a small subset. Patients younger than 65 years had a high burden of comorbidities and incurred higher rates of death and readmission at 1 year compared to their older counterparts. These observations suggest that heart team decision-making regarding TAVR for most patients in this age group is clinically valid.

Introduction

Although transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is now the treatment of choice for most older patients with severe aortic stenosis across the risk spectrum, the treatment of patients younger than 65 years who require AVR has been more challenging. This issue has been inadequately addressed by low surgical risk trials, as few trial patients were young (ie, fewer than 8% were younger than 65 years). Treatment decisions are more complex when lifetime management is introduced into decision-making; that is, when patients are expected to outlive the valve durability. Detailed long-term follow-up after AVR extends at most to 10 years. In this context, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines recommended surgical AVR (SAVR) over TAVR for patients younger than 65 years due to a probable life expectancy greater than 20 years, while acknowledging a role for shared decision-making wherein informed patient preferences could be considered.

Despite these guideline recommendations, 3 recent analyses indicate a growing percentage of patients younger than 65 years receiving TAVR over SAVR in the past few years. Reports from state registries show that nearly 50% of younger patients (<65 years in 2 studies and <60 years in the other) undergoing isolated AVR received TAVR. These findings were alternatively interpreted as an indication that TAVR operators are making inappropriate recommendations for TAVR in this age group, younger patients tend to prioritize less invasiveness over all other treatment attributes, or heart teams are failing to inform patients of the lifetime issues of valve failure and risk of repeat AVR after TAVR.

An alternative hypothesis is that many younger patients with aortic stenosis have a high comorbidity burden, which shortens life expectancy and negates the need for repeat procedures. In this context, heart teams may be making thoughtful decisions with patients to balance harms, benefits, and valve longevity and reserving TAVR for younger patients with limited longevity. To help inform these hypotheses regarding the increasing use of TAVR in younger patients, we used data from the Society for Thoracic Surgeons (STS)/ACC Transcatheter Valve Therapy (TVT) Registry to describe the characteristics and outcomes of patients younger than 65 years in the US who underwent balloon-expandable valve (BEV) TAVR in the contemporary low-risk era and compare this group to their older counterparts (aged 65-80 years).

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

The STS/ACC TVT Registry and its data elements have been previously described. The TVT Registry protocol was granted a waiver of informed consent owing to the use of unidentifiable patient data by Advarra and the Duke University institutional review board, who approved the study. The TVT Registry is inclusive of all patients receiving a commercial TAVR device. For this study, those who provided data on BEV at the request of Edwards LifeSciences were included. All patients who received TAVR for native valve aortic stenosis with the contemporary SAPIEN family of BEVs (SAPIEN 3, SAPIEN 3 Ultra, or SAPIEN 3 Ultra RESILIA [Edwards Lifesciences]) in the STS/ACC TVT Registry were examined in this retrospective registry-based analysis. Patients aged younger than 65 and those aged 65 to 80 years were compared in the era of low–surgical risk approval (August 2019 to September 2023). Baseline and procedural characteristics and in-hospital, 30-day, and 1-year outcomes were evaluated and compared.

Study Outcomes

Outcomes included comorbid conditions (Table 1), all-cause mortality, stroke, and a composite of all-cause mortality or stroke in-hospital, at 30 days, and at 1 year following the procedure. Additional outcomes included cardiac death, life-threatening bleeding, major vascular complications, new pacemaker, new requirement for dialysis, new-onset atrial fibrillation, aortic valve reintervention, or any readmission. Health status outcomes included quality of life as assessed by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) score.

Table 1. Unmatched Baseline Characteristicsa.

| No./total No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age <65 y (n = 13 849) | Age 65-80 y (n = 125 846) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 59.7 (4.8) | 74.1 (4.2) | <.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 9068/13 849 (65.5) | 77 817/125 843 (61.8) | <.001 |

| Female | 4781/13 849 (34.5) | 48 026/125 843 (38.2) | |

| Race and Ethnicityb | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 97/13 849 (0.7) | 392/125 846 (0.3) | <.001 |

| Asian | 121/13 849 (0.9) | 970/125 846 (0.8) | .19 |

| Black | 1037/13 849 (7.5) | 5135/125 846 (4.1) | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 1166/13 649 (8.5) | 6278/123 939 (5.1) | <.001 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 21/13 849 (0.2) | 116/125 846 (0.1) | .034 |

| White | 11 935/13 849 (86.2) | 115 209/125 846 (91.5) | <.001 |

| Multiple | 140/13 849 (1.0) | 1000/125 846 (0.8) | .007 |

| Unknown | 498/13 849 (3.6) | 3024/125 846 (2.4) | <.001 |

| STS risk score, mean (SD), % | 3.1 (3.5) | 3.3 (3.2) | <.001 |

| STS risk score, median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.2-3.6) | 2.3 (1.5-3.9) | <.001 |

| 4 | 10 463/13 461 (77.7) | 93 686/122 922 (76.2) | <.001 |

| 4-8 | 2107/13 461 (15.7) | 22 102/122 922 (18) | <.001 |

| >8 | 891/13 461 (6.6) | 7134/122 922 (5.8) | <.001 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 33.6 (15.9) | 31.2 (10.7) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 11619/13 847 (83.9) | 113 076/125 833 (89.9) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 6551/13 842 (47.3) | 55 223/125 817 (43.9) | <.001 |

| Currently receiving dialysis | 1613/13 830 (11.7) | 5041/125 700 (4.0) | <.001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 4479/13 822 (32.4) | 34 067/125 671 (27.1) | <.001 |

| Hostile chest | 680/13 846 (4.9) | 3354/125 816 (2.7) | <.001 |

| Immunocompromise present | 1248/12 648 (9.9) | 7517/113 819 (6.6) | <.001 |

| Endocarditis | 119/13 845 (0.9) | 414/125 819 (0.3) | <.001 |

| Permanent pacemaker | 581/13 845 (4.2) | 8847/125 818 (7.0) | <.001 |

| Previous ICD | 391/13 840 (2.8) | 2939/125 831 (2.3) | <.001 |

| Prior PCI | 3395/13 842 (24.5) | 37 257/125 814 (29.6) | <.001 |

| Prior CABG | 1405/13 843 (10.1) | 15 960/125 817 (12.7) | <.001 |

| Prior stroke | 1258/13 847 (9.1) | 12 155/125 821 (9.7) | .03 |

| Prior TIA | 562/13 845 (4.1) | 7181/125 778 (5.7) | <.001 |

| Previous cardiac surgeries | 1713/13 791 (12.4) | 17 168/125 377 (13.7) | <.001 |

| Prior aortic valve procedure | 402/13 843 (2.9) | 2389/125 825 (1.9) | <.001 |

| Carotid stenosis | 1279/12 670 (10.1) | 18 035/116 890 (15.4) | <.001 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 2375/13 844 (17.2) | 23 838/125 824 (18.9) | <.001 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 2568/13 840 (18.6) | 21 225/125 779 (16.9) | <.001 |

| Heart failure within 2 wk | 8715/12 651 (68.9) | 74 481/113 982 (65.3) | <.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock within 24 h | 312/13 845 (2.3) | 964/125 742 (0.8) | <.001 |

| Cardiac arrest within 24 h | 60/13 835 (0.4) | 260/125 739 (0.2) | <.001 |

| Porcelain aorta | 202/13 844 (1.5) | 1077/125 792 (0.9) | <.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 2795/13 843 (20.2) | 37 054/125 801 (29.5) | <.001 |

| Home oxygen | 1133/13 834 (8.2) | 7937/125 728 (6.3) | <.001 |

| NYHA class III/IV | 8848/13 684 (64.7) | 76 256/124 698 (61.2) | <.001 |

| KCCQ overall summary score, mean (SD) | 47.7 (26.3) | 52.9 (25.8) | <.001 |

| Current/recent smoking (<1 y) | 2904/10 158 (28.6) | 10 759/80 913 (13.3) | <.001 |

| 5- m Walk test, mean (SD), s | 6.6 (5.8) | 7.0 (4.9) | <.001 |

| Hemoglobin, mean (SD), g/dL | 12.8 (2.3) | 12.7 (2.1) | .009 |

| Albumin, mean (SD), g/dL | 3.9 (0.6) | 3.9 (0.5) | <.001 |

| GFR, mean (SD), mL/min | 68.9 (33.1) | 65.9 (25.7) | <.001 |

| Left main stenosis ≥50% | 521/13 095 (4.0) | 5928/119 230 (5.0) | <.001 |

| Proximal LAD ≥70% | 1204/13 045 (9.2) | 13 186/119 021 (11.1) | <.001 |

| Echocardiographic characteristics | |||

| AV area, mean (SD), cm2 | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.2) | .048 |

| AV mean gradient, mean (SD), mm Hg | 44.0 (14.8) | 42.2 (13.5) | <.001 |

| AV mean gradient ≥20, mm Hg | 13253/13 690 (96.8) | 120 934/124847 (96.9) | .71 |

| AV annular size, mean (SD), mm | 25.3 (2.8) | 24.8 (2.6) | <.001 |

| AV morphology, bicuspid | 3472/13 755 (25.2) | 9552/125 001 (7.6) | <.001 |

| AV morphology, tricuspid | 9838/13 755 (71.5) | 111 703/125001 (89.4) | <.001 |

| LVEF, mean (SD), % | 53.6 (14.4) | 56.9 (11.8) | <.001 |

| ≥Moderate aortic regurgitation | 2705/13 661 (19.8) | 18 756/124545 (15.1) | <.001 |

| ≥Moderate mitral regurgitation | 1734/9751 (17.8) | 17 729/93227 (19) | .003 |

| ≥Moderate tricuspid regurgitation | 1572/13 713 (11.5) | 13 551/124537 (10.9) | .04 |

Abbreviations: AV, aortic valve; BMI, body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The performance of matching was assessed by absolute standardized differences for which a difference of less than 0.10 could be considered as a good balance.

Race and ethnicity data were collected via self-reported data from patients at the site level and was included to assess for differences in representation across age groups.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and partial graphical illustration using R version 4.3.2 (R Foundation). Statistical significance was 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered significant for all tests. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline was followed.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics and outcomes of each group were compared both prior to and after propensity matching. Race and ethnicity were based on self-reported data from patients at the site level and was included to assess for differences in representation across age groups. The racial and ethnic definitions were drawn from the US Office of Management and Budget Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity,which has been revised since these data were collected.

Continuous variables were compared based on the t test, and categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test. The 95% confidence intervals were used as a statistical significance criterion. Pairwise comparison was used (ages younger than 65 years vs 65-80 years) to test whether a significant difference existed between the 2 groups. Time to event was assessed using Kaplan-Meier estimates, and statistical significance was evaluated with a log-rank test.

Propensity score matching was conducted using a logistic regression model with age group as a binary dependent variable (<65 years vs 65-80 years). Matching was performed based on a greedy matching strategy with a caliper of width equal to 0.2. In total, 48 covariates were used for propensity score matching (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Missing values were imputed using the Markov-Chain Monte Carlo method. The performance of matching was assessed by absolute standardized differences for which a difference of less than 0.10 is considered as a good balance. Baseline characteristics of each group were compared both prior to and after propensity matching. Continuous variables were compared based on the t test, and categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test. The 95% confidence intervals were used as a statistical significance criterion.

Subgroup analyses included a comparison by age of patients in whom low risk was reported as heart team reason for procedure. The STS/ACC TVT Registry instructs local site registry staff, “If the heart team did not document a risk category, consider patients with a predicted risk of 30-day mortality based on the risk model developed by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons as noted below,” and advised that “low risk is considered <3%.” The second subgroup analysis was a comparison of case selection among patients younger than 65 years in the early era (August 2019 to August 2020) and later era (August 2022 to August 2023). The total number of TAVRs performed in each age group over the study period was also collected and reported.

Results

Study Population and Baseline Characteristics

Among 241 420 patients who underwent BEV TAVR from August 2019 to September 2023, patients younger than 65 years constituted a small percentage (n = 13 849 [5.7%]); those aged 65 to 80 comprised 52.1% (n = 125 846), and those older than 80 years made up 42.1% (n = 101 725). We elected to use a two-cohort analysis population (n = 139 695), which includes 13 849 (9.9%) younger than 65 years and the remainder aged 65 to 80 years (Table 1). The population older than 80 years was not included in this report as this report focused on characteristics and outcomes for younger patients compared to their closest counterparts. Among those younger than 65 years, the mean (SD) age was 59.7 (4.8) years; 9068 of 13 849 patients (65.5%) were male and 4781 (34.5%) were female. Among those aged 65 to 80 years, the mean (SD) age was 74.1 (4.2) years, and 77 817 of 125 843 patients (61.8%) were male and 48 026 (38.2%) were female. Representation with respect to race and ethnicity was higher in the younger cohort. Among those younger than 65 years, 97 patients (0.7%) were American Indian or Alaska Native, 121 (0.9%) were Asian, 1037 (7.5%) were Black, 21 (0.2%) were Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, 11 935 (86.2%) were White, 140 (1.0%) reported multiple races or ethnicities, and 498 (3.6%) were unknown and reported as other. Among those aged 65 to 80 years, 392 (0.3%) were American Indian or Alaska Native, 970 (0.8%) were Asian, 5135 (4.1%) were Black, 116 (0.1%) were Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, 115 209 (91.5%) were White, 1000 (0.8%) reported multiple races or ethnicities, and 3024 (2.4%) were unknown and reported as other.

Patients younger than 65 years were more likely to have a bicuspid aortic valve than the older cohort (3472/13 755 [25.2%] vs 9552/125 001 [7.6%], respectively; P < .001). Patients younger than 65 years undergoing TAVR often had serious cardiac history, including atrial fibrillation (2795 [20.2%]), prior myocardial infarction (2568 [18.6%]), or cardiac surgery (1713 [12.4%]). Heart failure within 2 weeks of procedure was common (8715 [68.9%]). One in 3 had chronic lung disease, and 1 in 10 were receiving dialysis (Table 1).

Analyses showed significant differences in comorbidities between age cohorts. Compared to patients aged 65 to 80 years, those younger than 65 years were more likely to smoke, use home oxygen, have diabetes, have immunocompromised states, currently be receiving dialysis, or have a hostile chest. Patients younger than 65 years had significantly lower baseline quality of life scores than those aged 65 to 80 years (baseline mean [SD] KCCQ score, 47.7 [26.3] vs 52.9 [25.8], respectively; P < .001) and slower 5-meter walk test times (mean [SD] 6.6 [5.8] seconds vs 7.0 [4.9] seconds, respectively; P < .001) (Table 1).

Procedural Characteristics and In-Hospital Outcomes

More than 95% of procedures were done through transfemoral access. Patients younger than 65 years had a lower percentage of conscious sedation, higher contrast volume, and a tendency toward larger transcatheter valve size compared to the older age group. There were no differences in implant success, coronary compression or obstruction, new requirement for dialysis, or aortic valve reintervention between the groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Unmatched Procedural Characteristics and In-hospital Outcomes.

| No./total No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age <65 y (n = 13 849) | Age 65-80 y (n = 125 846) | ||

| Procedure details | |||

| Transfemoral approach | 13 239/13 844 (95.6) | 119 908/125 830 (95.3) | .08 |

| Type of anesthesia, moderate sedation | 7507/13 840 (54.2) | 72 629/125 722 (57.8) | <.001 |

| Total procedure time, mean (SD), min | 71.5 (41.4) | 68.6 (39.7) | <.001 |

| Fluoroscopy time, mean (SD), min | 14.5 (10.9) | 14.1 (9.7) | <.001 |

| Contrast volume, mean (SD), mL | 91.0 (57.6) | 85.5 (52.1) | <.001 |

| Implant success | 13 750/13 845 (99.3) | 124 809/125 821 (99.2) | .14 |

| Conversion to open heart surgery | 30/13 828 (0.2) | 302/125 712 (0.2) | .59 |

| Procedure status | |||

| Elective | 11 747/13 848 (84.8) | 114 919/125 823 (91.3) | <.001 |

| Urgent/emergency/salvage | 2101/13 848 (15.2) | 10 904/125 823 (8.7) | |

| Heart team reason for procedure | |||

| Inoperable/extreme risk | 761/13 763 (5.5) | 4402/125 124 (3.5) | <.001 |

| High risk | 3907/13 763 (28.4) | 28 936/125 124 (23.1) | <.001 |

| Intermediate risk | 3634/13 763 (26.4) | 41 929/125 124 (33.5) | <.001 |

| Low risk | 5461/13 763 (39.7) | 49 857/125 124 (39.8) | .70 |

| Procedure complication | |||

| Annular dissection | 14/13 849 (0.1) | 140/125 846 (0.1) | .73 |

| Aortic dissection | 13/13 849 (0.1) | 96/125 846 (0.1) | .48 |

| Coronary compression or obstruction | 16/13 849 (0.1) | 102/125 846 (0.1) | .19 |

| Device embolization | 3/13 849 (0.0) | 149/125 846 (0.1) | .001 |

| Perforation with or without tamponade | 33/13 849 (0.2) | 515/125 846 (0.4) | .002 |

| THV size | |||

| 20 mm | 177/13 844 (1.3) | 2330/125 799 (1.9) | <.001 |

| 23 mm | 3340/13 844 (24.1) | 37 492/125 799 (29.8) | <.001 |

| 26 mm | 6252/13 844 (45.2) | 56 283/125 799 (44.7) | .35 |

| 29 mm | 4075/13 844 (29.4) | 29 694/125 799 (23.6) | <.001 |

| In-hospital outcomes | |||

| Index hospitalization length of stay, median (IQR), d | 1.0 (1.0-2.0) | 1.0 (1.0-2.0) | <.001 |

| ICU length of stay, mean (SD), h | 20.5 (53.7) | 17.8 (42.8) | .002 |

| Discharge to home | 13 092/13 848 (94.5) | 119 309/125 838 (94.8) | .17 |

| All-cause mortality | 133/13 849 (1.0) | 930/125 846 (0.7) | .004 |

| Cardiac death | 93/13 849 (0.7) | 581/125 846 (0.5) | <.001 |

| Stroke | 118/13 849 (0.9) | 1272/125 846 (1.0) | .07 |

| Aortic valve reintervention | 8/13 849 (0.1) | 95/125 846 (0.1) | .47 |

| Life-threatening bleeding, derived | 133/13 849 (1.0) | 1052/125 846 (0.8) | .13 |

| Major vascular complication | 110/13 849 (0.8) | 1242/125 846 (1.0) | .03 |

| New requirement for dialysis | 40/13 849 (0.3) | 323/125 846 (0.3) | .48 |

| New pacemaker without baseline pacemaker | 566/13 268 (4.3) | 6519/116 999 (5.6) | <.001 |

| Any readmissions | 29/13 849 (0.2) | 250/125 846 (0.2) | .79 |

| New onset of atrial fibrillation | 145/11 937 (1.2) | 1572/99 182 (1.6) | .002 |

Although implant success and complication rates did not differ, all-cause in-hospital mortality was higher in patients younger than 65 years compared to the group aged 65 to 80 years (133 of 13 849 [1.0%] vs 930 of 125 846 [0.7%], respectively; P = .004), without a difference in acute stroke (118 of 13 849 [0.9%] vs 1272 of 125 846 [1.0%], respectively; P = .07). There was no difference in the combined end point (all-cause in-hospital mortality or stroke) between groups. New pacemaker rates were low in both groups (566 of 13 268 [4.3%] among those <65 years vs 6519 of 116 999 [5.6%] in those aged 60-85 years; P < .001) (Table 2).

Thirty-Day and 1-Year Clinical Outcomes

At 30 days following TAVR, patients younger than 65 years had higher all-cause mortality than patients in the group aged 65 to 80 years (210 [1.6%] vs 1645 [1.4%], respectively; P = .03). Patients younger than 65 years had lower stroke rates than their older counterparts (156 [1.2%] vs 1805 [1.5%], respectively; P = .004), with no significant difference in new requirements for dialysis and aortic valve reintervention (Table 3).

Table 3. Unmatched 30-Day and 1-Year Clinical Outcomes.

| Events, No. (Kaplan-Meier rate, %) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age <65 y (n = 13 849) | Age 65-80 y (n = 125 846) | ||

| 30-d Outcomes | |||

| All-cause mortality | 210 (1.6) | 1645 (1.4) | .03 |

| Cardiac death | 120 (0.9) | 844 (0.7) | .007 |

| Stroke | 156 (1.2) | 1805 (1.5) | .004 |

| Aortic valve reintervention | 15 (0.1) | 128 (0.1) | .81 |

| Life-threatening bleeding, derived | 137 (1.0) | 1137 (0.9) | .27 |

| Major vascular complication | 129 (0.9) | 1389 (1.1) | .07 |

| New requirement for dialysis | 48 (0.4) | 384 (0.3) | .38 |

| New pacemaker without baseline pacemaker | 742 (5.8) | 8988 (7.9) | <.001 |

| Any readmissions | 1016 (7.8) | 8653 (7.2) | .02 |

| New onset of atrial fibrillation | 201 (1.7) | 2157 (2.2) | <.001 |

| 1-y Outcomes | |||

| All-cause mortality | 908 (9.9) | 6877 (8.2) | <.001 |

| Cardiac death | 289 (3.0) | 1931 (2.1) | <.001 |

| Stroke | 242 (2.2) | 2691 (2.7) | .003 |

| Aortic valve reintervention | 51 (0.5) | 332 (0.4) | .02 |

| Life-threatening bleeding, derived | 204 (1.8) | 1549 (1.5) | .01 |

| Major vascular complication | 152 (1.2) | 1493 (1.2) | .37 |

| New requirement for dialysis | 89 (0.9) | 619 (0.6) | .01 |

| New pacemaker without baseline pacemaker | 844 (7.0) | 9925 (9.2) | <.001 |

| Any readmissions | 2740 (28.2) | 23178 (26.1) | <.001 |

| New onset of atrial fibrillation | 285 (2.9) | 2929 (3.5) | <.001 |

At 1 year, patients younger than 65 years had higher rates of any readmission than those aged 65 to 80 years (2740 [28.2]% vs 23 178 [26.1%], respectively; P < .001). Nearly 1 in 10 patients younger than 65 years had died. Younger patients were more likely to die than their older counterparts (908 [9.9%] vs 6877 [8.2%], respectively; P < .001) (Table 3; Figure 1A).

Figure 1. One-Year Mortality.

HR indicates hazard ratio.

Quality of life as measured by KCCQ improved significantly for both age groups at 30 days and 1 year (mean [SD] increase at 30 days, 32.1 [26.1] in those <65 years and 27.8 [25.1] in those aged 65-80 years; at 1 year, 34.0 [26.9] in those 65 years and 29.9 [25.4] in those aged 65 to 80 years). KCCQ was underreported, with one-third of patients providing data at 1 year.

In the matched cohort, with all adjusted covariates showing an absolute standardized difference of less than 0.1, readmission at 1 year remained higher in younger patients (2732 [28.2%] vs 2589 [26.8%], respectively; P = .03). Mortality at 1 year remained high after matching and was not different between younger and older patients (905 [9.9%] vs 927 [10.1%], respectively; P = .55) (eTables 2 and 3 in Supplement 1; Figure 1B).

In the subgroup analysis of patients in whom low risk was reported as the heart team reason for the procedure, patient comorbidity burden remained high, and 1-year hospital readmissions and all-cause mortality remained comparable between young patients selected for TAVR and their older counterparts (readmission, 699 [18.0%] vs 6617 [18.8%], respectively; P = .32; mortality, 148 [4.1%] vs 1214 [3.7%], respectively; P = .22) (eTables 4-6 in Supplement 1).

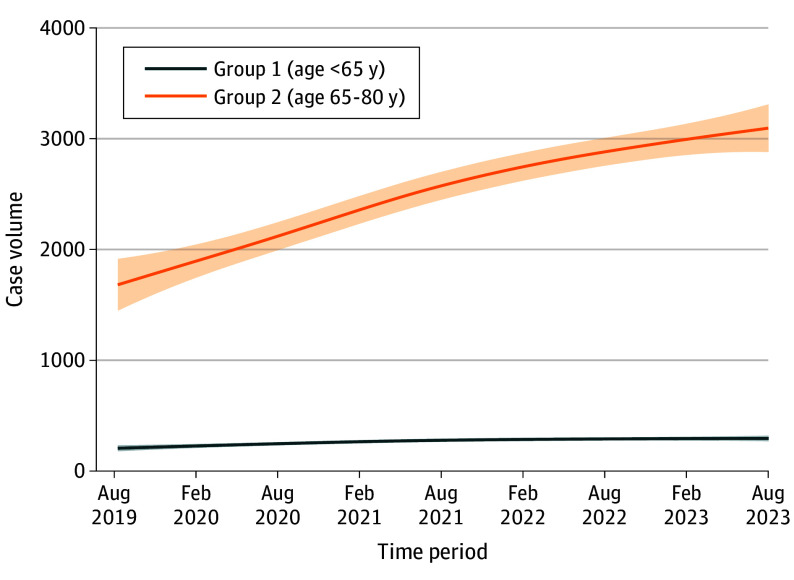

During the low–surgical risk era (2019 to 2023), the overall percentage of patients younger than 65 years undergoing BEV TAVR declined. Absolute numbers for these patients receiving TAVR increased slightly during 2020 and then remained flat (Figure 2). When comparing characteristics of patients younger than 65 years in the earlier portion of this era (August 2019 to August 2020) to later (August 2022 to August 2023), STS risk score fell slightly (from 3.3% to 3.0%; P < .001), and comorbidity burden remained high in the later era (atrial fibrillation/flutter, 740 of 3651 [20.3%]; prior myocardial infarction, 642 of 3651 [17.6%]; cardiac surgery, 412 of 3643 [11.3%]; chronic lung disease, 1098 of 3651 [30.1%]; dialysis, 415 of 3643 [11.4%]) (eTable 7 in Supplement 1).

Figure 2. Temporal Trends in Case Volume by Age Group (2019-2023).

Discussion

In this cohort study, patients younger than 65 years selected for BEV TAVR in the US during the low-risk era (2019-2023) had a high comorbidity burden and 1 -year mortality, both greater than their counterparts aged 65 to 80 years. Following successful TAVR, morbidity at 1 year was significant in this select group of patients younger than 65 years, with more than 28.2% of patients rehospitalized. This refutes the claim that heart teams are rejecting current US guidelines for younger patients with aortic stenosis. Instead, the evidence supports that heart teams continue to use TAVR in patients with a high comorbidity burden. These selected patients are unlikely to have expanded longevity, as they experience significantly higher mortality seen as early as 1 year postprocedure (9.9%). This mortality rate is 10 times higher than patients a decade older who were selected for the BEV low–surgical risk randomized clinical trial (1-year mortality: 1.0% for TAVR, 2.5% for SAVR). Patients undergoing TAVR are not average 65-year-olds and are unlike patients enrolled in trials with equipoise between TAVR and SAVR, making registry comparisons problematic.

Younger patients remain a minority among those receiving TAVR: those younger than 65 years constituted 5.7% of patients who underwent TAVR with BEV, with the percentage of young patients receiving BEV TAVR decreasing over time. Absolute numbers of TAVR in younger patients remained low and with minimal growth in the low–surgical risk era. These comparative data speak to rational case selection for younger patients undergoing aortic stenosis by heart teams in real-world practice.

Current regulatory policies require the participation of a heart team to determine suitability for the procedure. The prevalence of comorbidities affecting longevity among younger patients in this analysis likely reflects careful case selection by local heart teams. The ACC/AHA guidelines advise, “Some younger patients with comorbid conditions have a limited life expectancy…decision-making should be individualized based on patient-specific factors that affect longevity or quality of life, such as co-morbid cardiac and noncardiac conditions.” Similarly, for young patients with severe aortic stenosis who have a predicted long lifespan, guidelines include consideration of mechanical valves or the Ross procedure to minimize the need for repeat sternotomy or interventions. While the use of mechanical valves began to decline before the advent of TAVR, in 2016, they were used in more than 30% of patients younger than 60 years in the STS Registry. Arguably, using any bioprosthetic valve in younger patients with a predicted longevity of 20 years or greater, as opposed to options including mechanical valves or the Ross procedure, is reason for scrutiny and assurance of appropriate shared decision-making.

Using administrative databases, recent research describes nearly equal distribution between TAVR and SAVR among younger patients treated for isolated aortic stenosis; however, included patients are a selected subset. Exclusions included mechanical valves, Ross procedures, other concomitant procedures, endocarditis, and prior AVR. In these reports, medical conditions that were associated with TAVR, such as prior coronary artery bypass surgery, chronic kidney disease, and congestive heart failure, tend to reduce longevity. Similarly, recent abstracts from the California State Discharge Administrative Database support the conclusion that young patients undergoing TAVR represent a small group of selected patients with multiple comorbidities (ie, 25.8% receiving dialysis and 73.8% with congestive heart failure). Efforts to propensity match between TAVR and SAVR in younger cohorts are unlikely to account for confounding variables that impact survival as early as 1 year postprocedure. To our knowledge, no randomized comparisons exist between TAVR and SAVR in any population that show better 1-year outcomes with SAVR; thus, the fact that survival curves in the propensity-matched registry comparisons separate early suggests that substantial baseline health differences remained.

In a French registry examining trends in treating severe aortic stenosis, fewer than 1 in 10 patients younger than 65 years received TAVR. The Charleston Comorbidity Index declined over time for the older cohorts but not for patients younger than 65 years, indicating high comorbidities. Less frequent use of TAVR in younger patients likely reflects the European Society of Cardiology guidelines, which establish a higher threshold for consideration of TAVR by age (<75 years vs US guidelines of <65 years). This difference may be explained by the longer life expectancy in Europe compared to the US.

The terms low risk and young are not straightforward predictors of patients’ longevity. Patients at low risk are defined as having a low risk of dying after surgery at 30 days, most commonly estimated by the STS predicted risk of mortality score. Factors not considered in risk calculators may include pulmonary hypertension, cirrhosis, wheelchair dependency or other markers of frailty, and overall rehabilitation potential. Due to the impact of these comorbidities on longevity, chronologic age is not necessarily a predictor for biologic age. The higher percentage of underrepresented groups among the younger cohort, including Black and Hispanic patients, may reflect health disparities leading to greater prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, limiting life expectancy.

While validated risk scores exist to predict 1-year health status and mortality, the focus of these scores is to identify when TAVR is futile rather than a tool to select between options for healthier patients. Likewise, the ACC TAVR risk calculator cannot be used for longevity estimates. It was intentionally limited to in-hospital mortality, rather than 30 days, to discourage direct comparisons. As noted in Arnold’s discussion of the utility of the ACC TAVR risk calculator, “In real-world practice, there is minimal overlap in the characteristics of patients who are treated with TAVR and SAVR…as such, these TAVR models should be used to estimate a patient’s risk for short-term mortality, but should not be used to contribute to the decision on TAVR versus SAVR.”

Life insurance actuarial tables are often referenced to predict longevity. However, patients who develop aortic stenosis often do not have a life expectancy that matches that of the general population because of comorbidities. While life tables estimate that people in their 50s can expect to live another 20 to 30 years, life expectancy with congestive heart failure is remarkably shorter: once diagnosed, those with high-risk features can expect to live an average of 6 years. Patients diagnosed with diabetes by age 50 years lose 6 years of life expectancy. After SAVR, younger patients see a loss of 4 years of life. A score for estimating an individual patient’s predicted life expectancy based on their comorbid conditions would be more useful for heart team discussions and shared decision-making with patients. This would provide necessary information on the probability the patient will live an additional 20 years following AVR, meeting the threshold described in the guidelines for SAVR.

Cardiovascular clinician skillsets in patient engagement and elicitation of informed patient preferences with validated decision aids are needed. Research demonstrates that patients arrive at clinics with uninformed preferences. Media coverage highlights a stated concern that patients are driving decision making toward TAVR: “patients know about it and they know they can get a quicker, easier procedure and be done, and that’s very appealing.” However, data exist from patient preference research that a goal of a minimally invasive procedure falls behind many other decisional attributes for patients. Thus, the focus for the heart team should remain on listening to informed preferences as a part of the decision-making process.

Limitations

This analysis is limited in several ways. We did not include patients receiving self-expanding valves in this analysis, and the STS/ACC TVT Registry does not include a SAVR subset for comparison. The registry has outcome data out to 1 year only. This analysis is also limited by site reporting, given that Medicare matching for mortality was not used. Some comorbid conditions that put a patient at high risk for surgery, such as pulmonary hypertension, were not included. Likewise, anatomic features that put patients at high risk for TAVR are not reported in the registry.

Prior observational studies compare rates of TAVR and SAVR for patients treated for isolated aortic stenosis. It cannot be determined whether patients undergoing TAVR in the current registry also underwent percutaneous coronary intervention, transcatheter mitral repair, or transcatheter left atrial appendage in a sequential fashion. That is, the data reported here may not reflect the treatment of isolated aortic stenosis but may include concomitant treatment.

Conclusions

In summary, patients younger than 65 years selected by heart teams for BEV TAVR in the low-risk era had worse baseline health and higher 1-year mortality and rehospitalization rates compared to older patients. Procedural complications were not different. After propensity matching, younger patients still had higher 1-year mortality and rehospitalization rates than their older counterparts, reflecting the competing risk of multiple comorbid conditions. Younger patients remain a small subset of all TAVRs, with minimal change in the low-risk era. These data from the TVT Registry support the premise that heart teams operate within US guideline recommendations. Further study will be necessary to understand the evolving risk profile of younger patients selected by heart teams for TAVR and describe longer-term outcomes.

eTable 1. Baseline, Echocardiographic, and Procedural Characteristics

eTable 2. Procedural Characteristics and In-hospital Outcomes for Matched Population

eTable 3. 30-day, and 1-year Clinical Outcomes for Matched Population

eTable 4. Baseline Characteristics – Subgroup analysis of low-risk patients only

eTable 5. Procedural Characteristics and In-hospital Outcomes – Subgroup analysis of low-risk patients only

eTable 6. 30-day, and 1-year Clinical Outcomes – Subgroup analysis of low-risk patients only

eTable 7. Baseline Characteristics – Subgroup analysis of Age<65 patients only

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al. ; PARTNER 3 Investigators . Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a balloon-expandable valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(18):1695-1705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, et al. ; Evolut Low Risk Trial Investigators . Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(18):1706-1715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thyregod HGH, Jørgensen TH, Ihlemann N, et al. Transcatheter or surgical aortic valve implantation: 10-year outcomes of the NOTION trial. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(13):1116-1124. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. ; Writing Committee Members . 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(4):450-500. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta T, DeVries JT, Gilani F, Hassan A, Ross CS, Dauerman HL. Temporal trends in transcatheter aortic valve replacement for isolated severe aortic stenosis. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2024;3(7):101861. doi: 10.1016/j.jscai.2024.101861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma T, Krishnan AM, Lahoud R, Polomsky M, Dauerman HL. National trends in TAVR and SAVR for patients with severe isolated aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(21):2054-2056. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.08.787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alabbadi S, Malas J, Chen Q, et al. Guidelines vs practice: surgical versus transcatheter aortic valve replacement in adults ≤60 years. Ann Thorac Surg. Published online August 22, 2024. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2024.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll JD, Mack MJ, Vemulapalli S, et al. STS-ACC TVT Registry of transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(21):2492-2516. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No . 15: Standards for Maintaining. Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 10.STS/ACC TVT Registry . Coder’s data dictionary 3.0. Accessed October 3, 2024. https://www.ncdr.com/WebNCDR/docs/default-source/tvt-public-page-documents/tvt_v3-0_datadictionarycoderspecifications.pdf?sfvrsn=9cc0d69f_4

- 11.Maxwell Y. TAVR use rising in young US patients, yet another analysis shows. Published May 6, 2024. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.tctmd.com/news/tavi-use-rising-young-us-patients-yet-another-analysis-shows

- 12.Services CfMaM . Decision memo for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). Updated June 21. Accessed June 21, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncacal-decision-memo.aspx?proposed=N&NCAId=293&type=Open&bc=ACAAAAAAQCAA&

- 13.Tam DY, Rocha RV, Wijeysundera HC, Austin PC, Dvir D, Fremes SE. Surgical valve selection in the era of transcatheter aortic valve replacement in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;159(2):416-427.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.05.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hage A, Hage F, Valdis M, Guo L, Chu MWA. The Ross procedure is the optimal solution for young adults with unrepairable aortic valve disease. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;10(4):454-462. doi: 10.21037/acs-2021-rp-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jahanyar J, Mastrobuoni S, Said SM, El Khoury G, de Kerchove L. Lack of clinical equipoise renders randomized-trial execution of Ross vs prosthetic valves an impossible task. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(1):e7-e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.04.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kowalówka AR, Kowalewski M, Wańha W, et al. Surgical and transcatheter aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis in low-risk elective patients: analysis of the Aortic Valve Replacement in Elective Patients From the Aortic Valve Multicenter Registry. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2024;167(5):1714-1723.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2022.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaefer A, Schofer N, Goßling A, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation versus surgical aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients: a propensity score-matched analysis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;56(6):1131-1139. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezz245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prosperi-Porta G, Nguyen V, Willner N, et al. Association of age and sex with use of transcatheter aortic valve replacement in France. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82(20):1889-1902. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. ; ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group . 2021 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(7):561-632. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuster V. Chronological vs biological aging: JACC Journals Family Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. Published online March 22, 2024. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tajeu GS, Safford MM, Howard G, et al. Black-White differences in cardiovascular disease mortality: a prospective US study, 2003-2017. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(5):696-703. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allana SS, Alkhouli M, Alli O, et al. Identifying opportunities to advance health equity in interventional cardiology: structural heart disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;99(4):1165-1171. doi: 10.1002/ccd.30021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldsweig AM, Coylewright M, Daggubati R, et al. ; SCAI 2022 Think Tank Structural Consortium . Disparities in utilization of advanced structural heart cardiovascular therapies. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2023;2(1):100535. doi: 10.1016/j.jscai.2022.100535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnold SV, Cohen DJ, Dai D, et al. Predicting quality of life at 1 year after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in a real-world population. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(10):e004693. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.004693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnold SV. Calculating risk for poor outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2019;26(3):125-129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Social Security Administration . Actuarial life table. Accessed October 3, 2024. https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6.html

- 27.Alter DA, Ko DT, Tu JV, et al. The average lifespan of patients discharged from hospital with heart failure. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(9):1171-1179. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2072-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glaser N, Persson M, Jackson V, Holzmann MJ, Franco-Cereceda A, Sartipy U. Loss in life expectancy after surgical aortic valve replacement: SWEDEHEART study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(1):26-33. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.04.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coylewright M, Otero D, Lindman BR, et al. An interactive, online decision aid assessing patient goals and preferences for treatment of aortic stenosis to support physician-led shared decision-making: early feasibility pilot study. PLoS One. 2024;19(5):e0302378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0302378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Col NF, Otero D, Lindman BR, et al. What matters most to patients with severe aortic stenosis when choosing treatment? framing the conversation for shared decision making. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0270209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0270209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Baseline, Echocardiographic, and Procedural Characteristics

eTable 2. Procedural Characteristics and In-hospital Outcomes for Matched Population

eTable 3. 30-day, and 1-year Clinical Outcomes for Matched Population

eTable 4. Baseline Characteristics – Subgroup analysis of low-risk patients only

eTable 5. Procedural Characteristics and In-hospital Outcomes – Subgroup analysis of low-risk patients only

eTable 6. 30-day, and 1-year Clinical Outcomes – Subgroup analysis of low-risk patients only

eTable 7. Baseline Characteristics – Subgroup analysis of Age<65 patients only

Data sharing statement