Abstract

BACKGROUND

High complex anal fistulas are epithelialized tunnels, with the main fistula piercing above the deep external sphincter and the internal opening approaching the dentate line. Conventional surgical procedures for high complex anal fistulas remove most of the external sphincter and damage the anorectal ring. Postoperative loss of anal function can cause physical and mental damage. Transanal opening of the intersphincteric space (TROPIS) is an effective procedure that completely preserves the external anal sphincter. However, its clinical application is limited by challenges in the localization of the internal opening of a fistula and the high risk of complications. On the basis of our clinical experience, we modified the TROPIS procedure for the treatment of treating high complex anal fistulas.

CASE SUMMARY

A patient with a high complex anal fistula located above the anorectal ring underwent modified TROPIS, which involved sepsis drainage and identification of the internal opening in the intersphincteric space. The patient with the high complex anal fistula recovered well postoperatively, without any postoperative complications or anal dysfunction. Anal function returned to normal after 17 months of follow-up.

CONCLUSION

The modified TROPIS procedure is the most minimally invasive surgery for anal fistulas that minimally impairs anal function. It allows the complete removal of infected anal glands and reduces the risk of postoperative complications. Modified TROPIS via the intersphincteric approach is an alternative sphincter-preserving treatment for high complex anal fistulas.

Keywords: High complex anal fistula, Inter-sphincteric infection, Trans-anal opening of inter-sphincteric space, Perianal, Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging, Anal function protection, Case report

Core Tip: High complex anal fistulas are a type of perianal infectious diseases barely to spontaneously heal. Surgical procedures usually impair the anal function. Trans-anal opening of inter-sphincteric space (TROPIS) is an effective surgical procedure to treat high anal fistulas, although there exist demerits. We created a modified TROPIS via polishing up the surgical approach, identification of internal opening and management of fistulas, which greatly simplified the surgical procedures, and largely reduced postoperative complications. We believed that the modified TROPIS is suitable for treating high complex anal fistulas in Asian people with a narrower anal canal.

INTRODUCTION

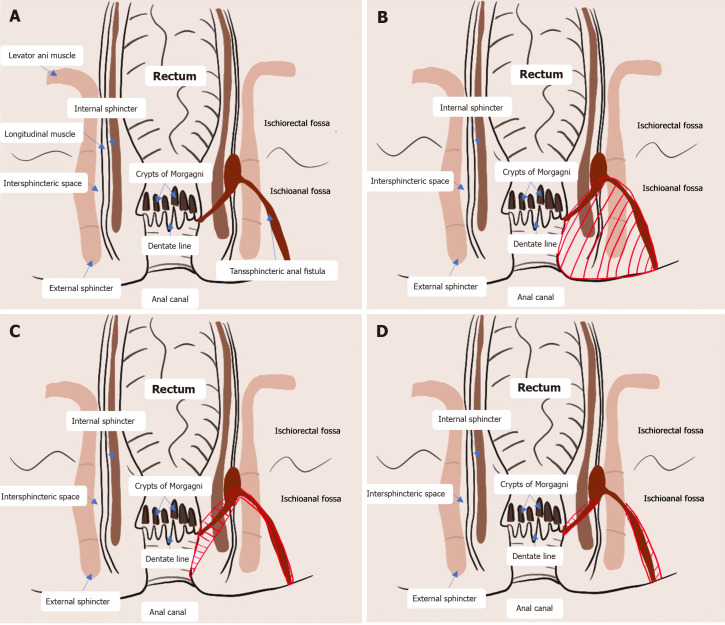

Anal fistulas are common manifestations of perianal infections that rarely heal on their own[1]. Surgical procedures are the only reliable treatment for anal fistulas[2]. High complex anal fistulas are typically complicated by their high anatomic location, the presence of branching fistulas with intricate fistula distributions and the risk of carcinogenesis[3]. Conventional surgical techniques are challenging, potentially leading to concerns of postoperative relapse and damage to anal function[4]. Fistulectomy is the conventional surgical option for anal fistulas[5] (Figure 1). Although it is recognized for its definite efficacy, fistulectomy results in large wounds, causes intense pain and is associated with long recovery times[6,7]. High anal fistulas are complicated in that the resection of a large amount of tissues and muscles is required, which increases the risks of postoperative anal dysfunction and incontinence[8]. Multiple sphincter-preserving methods, including fistula flap surgery, fibrin glue injection, bioprosthetic plug use, ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract and stem cell therapy, are available. Nevertheless, all these methods have drawbacks. The transanal opening of the intersphincteric space (TROPIS) was initially described by Garg[9] in 2017. It is an effective surgical procedure for the treatment of high anal fistulas, complex fistulas and horseshoe fistulas. There is increasing evidence advocating for TROPIS for anal fistulas owing to its satisfactory surgical outcomes, and the cure rate is particularly high, up to 90.4%[9]. Owing to the small wound area, patients with anal fistulas who undergo TROPIS can be discharged within 24 hours after surgery and return to their normal daily life and working shortly thereafter. Limitations of TROPIS, however, have been observed during clinical application. First, the indications for TROPIS for anal fistula are very strict. Second, the identification of the internal opening from the anus increases the difficulty of full exposure of the surgical field. Third, the relatively large incision in the rectum causes considerable bleeding. Limitations of TROPIS, however, have been observed during clinical application. We modified the TROPIS procedure by refining the surgical approach, identifying the internal opening and managing the fistulas. We performed an innovative sphincter-preserving surgical procedure involving the widening of the intersphincteric plane and therefore successfully eradicated a high complex anal fistula (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Representative images showing the surgical procedure for anal fistulas; the red shaded area indicates the surgical wound, and the green arrow denotes the surgical approach and operating path. A: Drainage from the intersphincteric infection contaminates the anal glands and perianal space through the glandular branches, creating an anal fistula and intersphincteric abscess; B: Fistulectomy involves the surgical removal of fistula tissues and surrounding muscles, fat and connective tissues, resulting in a large wound area; C: Transanal opening of the intersphincteric space (TROPIS) involves the identification of the internal opening by injecting methylene blue or using a probe, followed by opening the fistula tract in the intersphincteric plane through the transanal route, resecting the lower part of the internal sphincter and scraping out the remaining branching fistulas; D: Modified TROPIS involves the widening of the intersphincteric plane through the transanal route and the identification of the internal opening easily and precisely, followed by drainage of the fistulas passing through the intersphincteric plane and tunnel-like fistulectomy of fistulas located lateral to the external sphincter. Branching fistulas with larger curvatures located lateral to the external sphincter are scraped out.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 53-year-old middle-aged male was admitted in July 2022 for a 3-year history of intermittent swelling and pain of a buttock mass.

History of present illness

The patient presented with a swollen, painful lump on the right buttock (1 cm × 1 cm) that was found after a long ride 5 years ago. The pain subsided after 2 days of rest. However, the swelling and pain recurred and were sometimes relieved by self-medicating with cefixime. Owing to worsened swelling and pain after a long ride 3 years ago, the patient sought medical help at a local hospital and was subsequently diagnosed with a perianal abscess. The pain was relieved by topical drugs but recurred every 2 months. The abscess began to spread upwards. Six months after topical drug treatment, the symptoms of the perianal abscess began to recur more frequently, approximately 2-3 times per month, and were not relieved by conservative treatment.

History of past illness

The patient used to have good physical condition, and denied chronic diseases like hypertension, diabetes mellitus and coronary heart disease. Surgical history was deniable.

Personal and family history

The patient and his family denied any history of infectious and hereditary diseases, smoking, alcohol consumption, major trauma and blood transfusion, or food or drug allergy.

Physical examination

The patient was admitted for physical examination at the anus. The appearance of the anus was still flat. The sacrococcygeal region on the right side was 4 cm × 6 cm away from the anal truncus and a 3 cm × 3 cm hard mass was palpable, with weakly positive tenderness, normal skin temperature, and no obvious fluctuating sensation. Finger-pointing of the anus identified an anal verge at the 6 o’clock, 5 cm vertically away from the anus, located in the depression of the hard inner mouth. The right posterior rectal ring was hard without blood staining in the retracted finger.

Laboratory examinations

No directly relevant laboratory tests for reference.

Imaging examinations

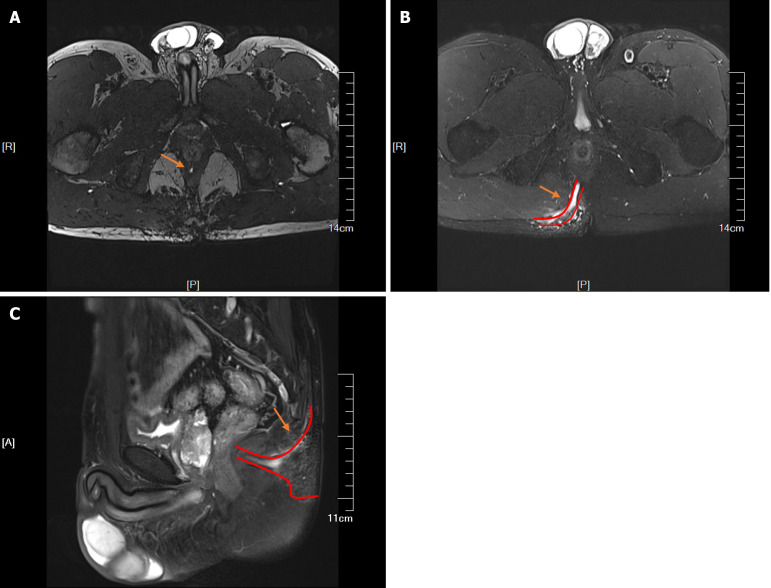

Ultrasonography of the perianal area using a high-frequency probe revealed a subcutaneous hypoechoic area on the right side of the sacrococcygeal area extending to the posterior anus, suggesting the presence of a high complex anal fistula. Hypoechogenicity was observed in the lateral sphincter at the six o'clock position of the anorectal ring, extending deep into the plane between the internal and external sphincter above the six o'clock position of the anorectal ring and spreading to the seven o'clock position on the right and five o'clock position on the left. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed the following: (1) Strip-like high-signal shadows on T2-weighted images at the five o'clock position of the perianal area in perianal lithotomy that inferoposteriorly extended into the right ischiorectal fossa, where two branching fistulas descended posteriorly on the right side; (2) An external opening situated subcutaneously in the right buttock; (3) Flocculent and nodular shadows near the right ischiorectal fossa and a small number of flocculent shadows in the right gluteus maximus on contrast-enhanced T2WI scans with fat suppression; (4) A poorly filled bladder with thick walls; (5) A slightly larger prostate with uneven signals in the central area and multiple nodular hyperplasia and flaky cystic changes; no obvious abnormalities in the bilateral seminal vesicles; and (6) Long shadows (11 mm × 16 mm) in the sacral canal at the level of the second and third sacral bones (S2-S3). MRI revealed a high complex anal fistula with local abscesses, slight oedema in the right gluteus maximus, benign prostatic hyperplasia and cystic lesions in the S2-S3 sacral canals (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging of a patient with a high complex anal fistula. A: Identification of the internal opening; B: Visualization of the main fistula with a broad range of perianal infection; C: Upwards spread of the infection responsible for the fistula.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Combined with the clinical symptoms, signs and imaging findings, the final diagnosis was high complex anal fistulae.

TREATMENT

Considering individual patient factors, location of the high complex anal fistula and extensive spread of local infections, conventional fistulectomy may cause massive damage to the anal sphincter and perianal tissue. Moreover, daily life and work would be greatly influenced by the large wound and long recovery time. We therefore preserved the sphincter by modifying the TROPIS procedure in the present case.

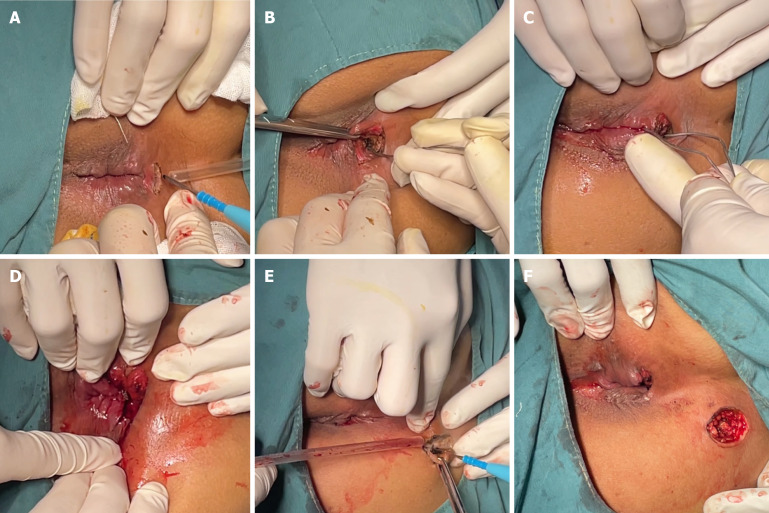

Intraspinal anesthesia was induced with the patient in the right recumbent position. An arc-shaped incision that was 1.5 cm long was made at the intersphincteric groove (Hilton white line), corresponding to the internal opening at the six o'clock position. After the sphincter space was opened superiorly, the fistula was explored superiorly until reaching the anorectal ring at the six o'clock position. With a 10-cm distance from the anal margin, the sphincter space was separated from the top of the fistula. The fistula probe was inserted through the space lying between the internal and external sphincters and the internal opening was identified 4 cm above the dentate line at the six o’clock position. The mucosa on both sides of the incision was ligated and trimmed to allow the drainage of pus. In addition, a circular incision was made on the lump (external opening) in the right-sided sacrococcygeal region, 7 cm away from the anal margin at the seven o'clock position. Fistula walls and necrotic tissues were exposed after the skin and subcutaneous tissues were cut open. Tunnel-like fistulectomy of the fistulas along the lateral wall of the external sphincter was performed and the necrotic tissues were removed. The edges of the incision were trimmed, and Vaseline gauze was used to fill the incision (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Procedure of the modified transanal opening of the intersphincteric space. A: An arc-shaped incision was made at the posterior median intersphincter groove of the perianal area, and the sphincter space was opened; B: The probe was inserted into the sphincter space to identify the internal opening; C: The probe was passed through the internal opening; D: A small part of the internal sphincter and connective tissues inferior to the internal opening were incised, and the edges of the incision were ligated and trimmed; E: A circular incision was made at the external incision, and then tunnel-like fistulectomy of the fistulas at the lateral side of the external sphincter was performed; F: Intact skin on and beneath the external sphincter was preserved.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

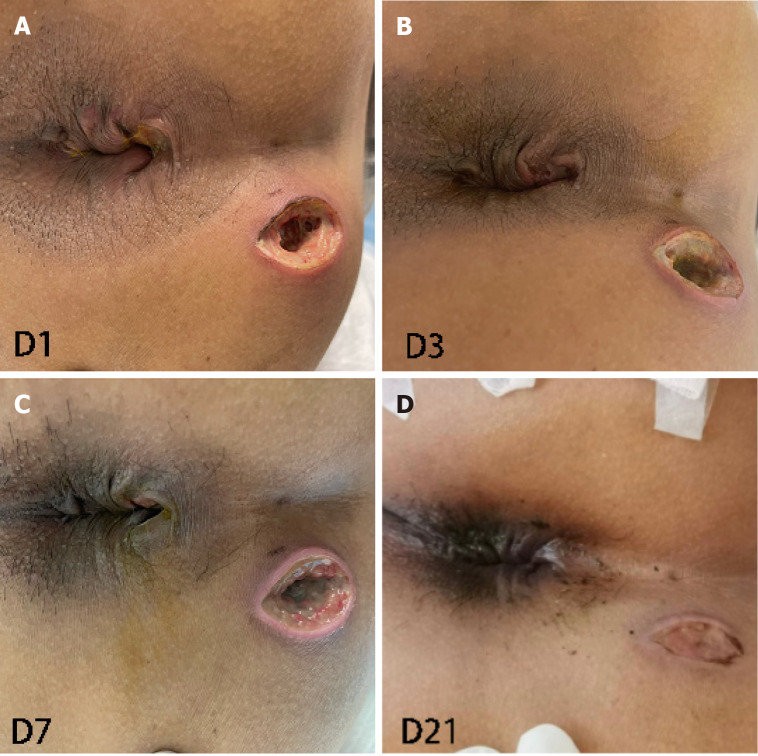

Postoperative vital signs were stable. Urinary retention was not observed. The patient could urinate at 6 hours postoperatively and perform off-bed activities 24 hours postoperatively (Figure 4). The postoperative visual analogue scale score was 2 points, indicating a minimal pain.

Figure 4.

Wound healing at 1, 3, 7 and 21 days after surgery. A: Day 1; B: Day 3; C: Day 7; D: Day 21.

The wound had completely healed at the 2-month postoperative examination (Figure 5). Anal discharge and fecal incontinence were not reported. The digital rectal exam was normal, and no blood was identified after withdrawing the finger used for examination. Anal stenosis, abnormal masses or cords or abnormalities in the lower rectum were not observed.

Figure 5.

Complete healing of the wound was observed at the 2-month follow-up.

Anal sphincter pressure was measured using water-perfused anorectal manometry at the 17-month postoperative examination. The resting pressure, squeeze pressure, functional anal canal length and other indices were all within the normal ranges (Table 1). Postoperative anal function returned to normal, indicating the safety of the modified TROPIS procedure in the treatment of high complex anal fistulas.

Table 1.

Anal sphincter pressure measurements by water-perfused anorectal manometry

|

Measurements

|

Values

|

References (in adults)

|

| Anal resting pressure (mmHg) | 51 | 50-70 |

| Anal squeeze pressure (mmHg) | 143 | 120-170 |

| Functional anal canal length (cm) | 3.2 | 3.2-3.5 |

| Delayed defecation reflex | Reversible and pressure curve decline | Reversible and pressure curve decline |

| Rectoanal contraction reflex | + | + |

| Rectoanal inhibitory reflex | 10 mL lead out | 5-10 mL lead out |

| Anal reflex diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 35 | > 30 |

| The first rectal sensation (mL) | 20 | 10-30 |

| Volume to get an urge to defecate (mL) | 100 | 50-80 |

| Maximal tolerated volume (mL) | 170 | 110-280 |

| Rectoanal pressure during defecation (mmHg) | 83 | > 45 |

DISCUSSION

Minimally invasive surgical treatment of anal fistulas has become the focus of research. Sphincter-preserving surgeries performed to date protect anal function to some extent but are infrequently performed due to their association with high recurrence rates, high medical expenses and challenging surgical procedure.

Garg[10] proposed that previous surgical procedures for anal fistulas aimed to mainly repair the primary internal opening and remove the fistula and did not focus on the eradication of the intersphincteric infection (Figure 1A). The TROPIS procedure proposed by Garg et al[11] is a simple surgical procedure that is especially suitable for patients with high complex anal fistulas. A large-scale retrospective study revealed that the overall cure rate of TROPIS for anal fistulas has increased to 86%. The infection in the sphincter muscles is caused by the collection of pus in a closed space. We consistently highlighted the importance of continuous drainage of pus from the perianal abscess to promote secondary healing of the anal fistula[12]. At present, infections in the anal glands are considered the main cause of anal fistulas. Originating in the anal glands, infected pus gradually spreads into the perianal space to form an intersphincteric abscess (Figure 1A). Approximately 20% of adult anal glands are tortuous, even extending outside the external sphincter[13]. Owing to their unique anatomic characteristics, anal gland infections easily result in abscesses[14]. High anal fistulas more frequently develop in the deep space posterior to the intersphincteric space than in the deep postanal space[15,16]. The intersphincteric space is a narrow airtight space enclosed by internal and external sphincters, which are tightly circular muscular tissues. Even a small amount of pus invading the intersphincteric space via the anal opening may cause high pressure, eventually leading to the infiltration of pus into the surrounding structures[17].

On the basis of our experience in the clinical management of anal fistulas via the TROPIS procedure, a series of limitations have surfaced. First, the transanal approach used in the TROPIS procedure (green arrow in Figure 1C) precluded complete exposure of the surgical field. The fistula tract in the intersphincteric space was widened, greatly influencing the efficacy of subsequent procedures. Second, the TROPIS procedure involves the widening of the intersphincteric space through the internal opening close to the dentate line; therefore, it was not recommended for anal fistula patients whose internal opening was not clearly identified. Third, a large wound made on the friable rectal mucosa with an enriched microvascular network increased the risk of bleeding. Moreover, the space for hemostasis was limited. Postoperative bleeding of the wound in anal fistula patients usually requires high-grade hemostatic techniques such as ultrasonic cutting with a hemostatic knife and Liga Sure tissue fusion. Fourth, only scraping out the fistulas was not sufficient to completely remove the necrotic and epithelialized tissues, resulting in a high risk of postoperative recurrence. Fifth, keeping the intersphincteric space open in Asian people with narrower anal canals was unfavorable[18].

The modified TROPIS procedure created by our research team has been key to circumventing the abovementioned disadvantages. We first modified the surgical approach by replacing the transanal approach with the intersphincteric approach (green arrow in Figure 1D)[9]. An arc-shaped incision was made at the intersphincteric groove below the internal opening preoperatively, as identified by pelvic MRI and/or perianal ultrasonography. The length of the incision, ranging from 1 cm to 2 cm, was determined on the basis of individual factors. Through this skin incision, the intersphincteric space was opened and separated superiorly. The resection of the internal opening was also modified. The infected anal glands and gland ducts at the internal opening were removed to form a fresh wound, thus accelerating second intention healing. The internal opening situated above the dentate line or even at the level of the anorectal ring was managed using an elastic seton to preserve anal function. Trimming the tissues surrounding the internal opening into the shape of an arc was conducive to drainage. Finally, tunnel-like fistulectomy of the fistulas at the lateral side of the external sphincter was performed, ensuring that the necrotic tissues were fully removed. Fistulas with larger curvatures piercing through the external sphincter were scraped out to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Overall, three modifications were made to the TROPIS procedure to markedly enhance its efficacy and safety for high complex anal fistulas. The intersphincteric approach allowed the widening of the infection foci lying in the intersphincteric space and the redirection of drainage. Identification of the internal opening directly through the intersphincteric approach significantly decreased the difficulty of surgery. The internal opening of the anal fistula is the source of infection. The openings of the anal glands are mostly located in the anal sinus, and the anal canal is the passage for defecation[19]. Bacteria within the anal canal allow abscesses to form and invade perianal tissues[20]. Thorough debridement of primary infection foci within the internal opening and fistulas extending out of the external sphincter without damaging the external sphincter preserved anal function and the perianal anatomical structure to the greatest extent.

CONCLUSION

The modified TROPIS procedure via the intersphincteric approach has unique merits in the surgical treatment of high complex anal fistulas. The intersphincteric approach allows the identification of the internal opening and drainage, thus simplifying the surgical procedure. Tunnel-like fistulectomy was performed from the external opening to the external sphincter, lowering the risk of postoperative anal dysfunction. A smaller wound results in less pain and faster recovery. We believe that the modified TROPIS procedure is especially suitable for the treatment of high complex anal fistulas in Asian people with narrower anal canals. On the basis of enhanced recovery after surgery and patient-centered care, the modified TROPIS procedure largely reduces the risk of postoperative complications, shortens the length of stay and enhances the utilization of health care resources. We strongly recommend the modified TROPIS procedure for the treatment of high complex anal fistulas and the preservation of the sphincter because of its low cost and focus on improved patient outcomes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Merits and demerits of fistulectomy vs transanal opening of the intersphincteric space vs modified transanal opening of the intersphincteric space

|

|

Fistulectomy

|

TROPIS

|

Modified TROPIS

|

| Surgical procedure | Remove the fistula, and surrounding muscles, fat and connective tissues | Identify the internal opening. Lay open the fistula tract in the intersphincteric plane through the transanal route. Resect the lower part of the internal sphincter. Scrap out the remaining branching fistulas | Widen the intersphincteric plane through the transanal route Identify the internal opening. A thorough drainage of fistulas passing through the intersphincteric plane. Tunnel-like fistulectomy of fistulas lateral to the external sphincter |

| Merits | Definite efficacy | High cure rate; small wound area; fast recovery | Easy to identify the internal opening and favor to the drainage and surgical procedure. Low risks of postoperative anal dysfunction and recurrence. Small wound area. Less pain. Fast recovery |

| Demerits | Large wound area; intensive pain; long recovery | Unable to clearly expose the surgical field. Not suitable for anal fistulas without a clearly identified internal opening. Not suitable for Asian people. High risks of bleeding and postoperative recurrence | Less popular. Lack of long-term follow-up data. Lack of a comparative group |

TROPIS: Transanal opening of intersphincteric space.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We appreciate the patient to voluntarily participate in this clinical study, and all the medical staff involved in the surgery and treatment of the patient.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Fayaz Y S-Editor: Liu H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Guo X

Contributor Information

Ya-Qun Wang, Anorectal Disease Center, Jiangsu Province traditional Chinese Medicine Innovation Center for Anorectal Disease, Nanjing 211000, Jiangsu Province, China; Department of Anorectal Surgery, Zhenjiang Hospital Affiliated to Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine (Zhenjiang Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine), Zhenjiang 212000, Jiangsu Province, China.

Yan Wang, Anorectal Disease Center, Jiangsu Province traditional Chinese Medicine Innovation Center for Anorectal Disease, Nanjing 211000, Jiangsu Province, China; Department of Anorectal Surgery, Yangzhou Jiangdu Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Yangzhou 225200, Jiangsu Province, China.

Xiao-Feng Jia, Department of Imaging, Nanjing Hospital of Chinese Medicine Affiliated to Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 211000, Jiangsu Province, China.

Qiao-Jing Yan, Anorectal Disease Center, Jiangsu Province traditional Chinese Medicine Innovation Center for Anorectal Disease, Nanjing 211000, Jiangsu Province, China; Colorectal Disease Center, Nanjing Hospital of Chinese Medicine affiliated to Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 210000, Jiangsu Province, China. njlf666@163.com.

Xue-Ping Zheng, Anorectal Disease Center, Jiangsu Province traditional Chinese Medicine Innovation Center for Anorectal Disease, Nanjing 211000, Jiangsu Province, China; Colorectal Disease Center, Nanjing Hospital of Chinese Medicine affiliated to Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 210000, Jiangsu Province, China.

References

- 1.Bakhtawar N, Usman M. Factors Increasing the Risk of Recurrence in Fistula-in-ano. Cureus. 2019;11:e4200. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall JF, Bordeianou L, Hyman N, Read T, Bartus C, Schoetz D, Marcello PW. Outcomes after operations for anal fistula: results of a prospective, multicenter, regional study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:1304–1308. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koizumi M, Matsuda A, Yamada T, Morimoto K, Kubota I, Kubota Y, Tamura S, Tominaga K, Sakatani T, Yoshida H. A case report of anal fistula-associated mucinous adenocarcinoma developing 3 years after treatment of perianal abscess. Surg Case Rep. 2023;9:159. doi: 10.1186/s40792-023-01743-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.García-Botello S, Garcés-Albir M, Espi-Macías A, Moro-Valdezate D, Pla-Martí V, Martín-Arevalo J, Ortega-Serrano J. Sphincter damage during fistulotomy for perianal fistulae and its relationship with faecal incontinence. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021;406:2497–2505. doi: 10.1007/s00423-021-02307-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ratto C, Grossi U, Litta F, Di Tanna GL, Parello A, De Simone V, Tozer P, DE Zimmerman D, Maeda Y. Contemporary surgical practice in the management of anal fistula: results from an international survey. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23:729–741. doi: 10.1007/s10151-019-02051-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Limura E, Giordano P. Modern management of anal fistula. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:12–20. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cadeddu F, Salis F, Lisi G, Ciangola I, Milito G. Complex anal fistula remains a challenge for colorectal surgeon. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:595–603. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-2104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garg P, Sodhi SS, Garg N. Management of Complex Cryptoglandular Anal Fistula: Challenges and Solutions. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2020;13:555–567. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S198796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garg P. Transanal opening of intersphincteric space (TROPIS) - A new procedure to treat high complex anal fistula. Int J Surg. 2017;40:130–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.02.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garg P. A new understanding of the principles in the management of complex anal fistula. Med Hypotheses. 2019;132:109329. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2019.109329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garg P, Kaur B, Goyal A, Yagnik VD, Dawka S, Menon GR. Lessons learned from an audit of 1250 anal fistula patients operated at a single center: A retrospective review. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;13:340–354. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i4.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugrue J, Nordenstam J, Abcarian H, Bartholomew A, Schwartz JL, Mellgren A, Tozer PJ. Pathogenesis and persistence of cryptoglandular anal fistula: a systematic review. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21:425–432. doi: 10.1007/s10151-017-1645-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seow-Choen F, Ho JM. Histoanatomy of anal glands. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:1215–1218. doi: 10.1007/BF02257784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srivastava KN, Agarwal A. A complex fistula-in-ano presenting as a soft tissue tumor. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:298–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurihara H, Kanai T, Ishikawa T, Ozawa K, Kanatake Y, Kanai S, Hashiguchi Y. A new concept for the surgical anatomy of posterior deep complex fistulas: the posterior deep space and the septum of the ischiorectal fossa. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:S37–S44. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0736-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H, Zhou ZY, Hu B, Liu DC, Peng H, Xie SK, Su D, Ren DL. Clinical Significance of 2 Deep Posterior Perianal Spaces to Complex Cryptoglandular Fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:766–774. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rojanasakul A, Pattanaarun J, Sahakitrungruang C, Tantiphlachiva K. Total anal sphincter saving technique for fistula-in-ano; the ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90:581–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson RL, Dollear T, Freels S, Persky V. The relation of age, race, and gender to the subsite location of colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;80:193–197. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970715)80:2<193::aid-cncr4>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, Regueiro MD, Gerson LB, Sands BE. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn's Disease in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:481–517. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2018.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamana T. Japanese Practice Guidelines for Anal Disorders II. Anal fistula. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2018;2:103–109. doi: 10.23922/jarc.2018-009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]