Abstract

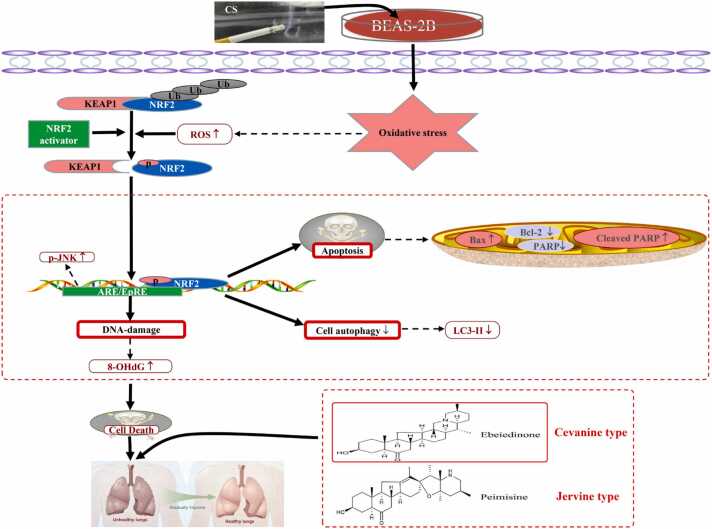

Ebeiedinone and peimisine are the major active ingredients of Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus. In this study, we looked at how these two forms of isosteroidal alkaloids protect human bronchial epithelial BEAS-2B cells from oxidative stress and apoptosis caused by cigarette smoke extract (CSE). First, the cytotoxicity was determined using the CCK8 assay, and an oxidative stress model was established. Then the antioxidative stress activity and mechanism were investigated by ELISA, flow cytometry, and Western blotting. By the CCK-8 assay, exposure to CSE (20%, 40%, and 100%) reduced the viability of BEAB-2S cells. The flow cytometry findings indicated that CSE-induced production of ROS (0.5% to maximum) and treatments with 10 μM ebeiedinone and 20 μM peimisine attenuated the production of ROS. The western blot assay results indicate that ebeiedinone and peimisine reduce CSE-induced oxidative stress, DNA damage, apoptosis, and autophagy dysregulation by inhibiting ROS, upregulating SOD and GSH/GSSG, and downregulating MDA, 4-HNE, and 8-OHdG through the NRF2/KEAP1 and JNK/MAPK-dependent pathways, thereby delaying the pathological progression of COPD caused by CS.Our data suggest that CSE causes oxidative stress, DNA damage, and apoptosis in BEAS-2B cells, as well as the progression of COPD. Ebeiedinone and peimisine fight CS-induced COPD by suppressing autophagy deregulation and apoptosis.

Keywords: Ebeiedinone, Peimisine, Oxidative stress, DNA damage, Cell apoptosis

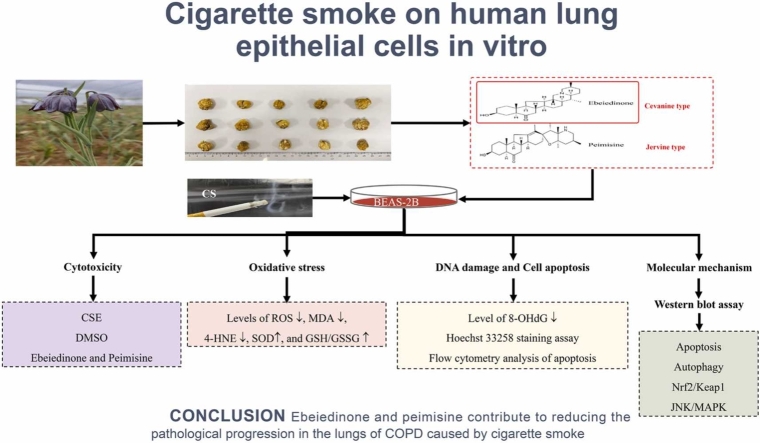

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is widely recognized as a global public health issue, having risen to the third leading cause of death worldwide due to its high morbidity and mortality.1 Smoking has long been known to be harmful to our health and is one of the leading causes of COPD.3, 2 Cigarette smoke (CS) is made up of complex chemical components with high levels of oxidants, including nicotine, tar, nicotine, acrolein, carbon monoxide, and so on.4, 5 Many efforts at understanding how CS causes the development of COPD have been made, yet the exact pathogenic mechanisms remain unclear. Numerous studies over the years have shown that oxidative stress,6 DNA damage,7 apoptosis,9, 10, 8 and autophagy-mediated cell death play important roles in the development of cigarette smoke-induced COPD.11

The current clinical treatment strategies for COPD include individualized therapy, triple therapy, and nebulized inhalation.12 However, these therapies have yet to demonstrate clinical benefit, indicating that more basic research is required to understand the underlying mechanisms that lead to COPD development. Due to a lack of specific drugs, COPD treatment outcomes have been poor, with mortality rates as high as 40%.13 Therefore, it is of great clinical value and significance to find effective and safe drugs to intervene in the development of slow-onset lung disease.14

According to the People's Republic of China Pharmacopoeia, Fritillaria Cirrhosa Bulbus (known as chuanbeimu in Chinese, FCB) is a perennial herb that belongs to the Liliaceae family.15 It is a well-known traditional Chinese herb that has been widely used for thousands of years for relieving cough and resolving phlegm and has a long history of medicinal use and medicinal value, with its main bioactive components being alkaloids.16 Modern pharmacological studies have shown that it has anti inflammatory,17 antioxidative stress,18 and can be used to treat pneumonia,19 COPD,20 asthma, and tuberculosis. It can also be used in the treatment of lung cancer,21 pulmonary fibrosis,22 acute respiratory distress syndrome and corona virus disease 2019,23 and other respiratory diseases,24 with the active ingredients having good drug-like properties. FCB is a precious Chinese herbal medicine that has been proven to have many applications in respiratory diseases and is an ideal therapeutic agent for the treatment of lung diseases. However, the potential mechanism of the active components is still not clear.

Ebeiedinone and peimisine, derived from the FCB, possess multiple biological activities.26, 27, 28, 25 However, no studies on the use of ebeiedinone and peimisine for the treatment of cigarette smoke-induced COPD have been reported. So, in this study, we explored at how ebeiedinone and peimisine protect against CSE-induced oxidative damage and cell apoptosis in human lung epithelial cells to know the mechanism by which cigarette smoke causes autophagy deregulation, ultimately leading to COPD.

Results

The cytotoxicity of BEAS-2B cells induced by CSE, dimethylsulfoxide, ebeiedinone, and peimisine

After 24 h of treatment, the cytotoxicity of different concentrations of soluble CSE, dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), ebeiedinone, and peimisine to BEAS-2B cells was assessed using the cell counting kit (CCK-8) assay. The cell viability of BEAS-2B cells was determined, as demonstrated in Supplementary Figure 1(a). CSE exposure (20%, 40%, and 100%) significantly reduced the cell viability of BEAS-2B cells (P < 0.0001). As shown in Supplementary Figure 1(b), the vehicle control group (DMSO) does not affect the cells, so in the subsequent experiments, the control (con) group is on vehicle control (0.1%, 0.25%, and 0.5%). In Supplementary Figure 1(c) and (d), ebeiedinone and peimisine (0, 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 100 μM) did not affect BEAS-2B cell viability (P > 0.05).

CSE stimulated the overproduction of intracellular reactive oxygen species

In CSE-stimulated BEAS-2B cells, we presumed a gradual accumulation of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). We first measured the contents of the ROS in BEAS-2B cells. BEAS-2B cells were exposed to various concentrations of CSE for 24 h and then incubated with 10 μM fluorescent probe, DCFDA, for 25 min. As shown in Supplementary Figure 2, ROS were measured after 24 h of exposure to the freshly prepared CSE solution in comparison to the control group, which stimulates the overproduction of intracellular ROS. Moreover, although not in a dose-dependent way, concerning the cytotoxicity evaluated above, we ultimately chose CSE (0.5%) as our stimulation content to create an in vitro oxidative stress model based on the maximal ROS content.

Cell morphology observation

BEAS-2B cells in different treatment groups were observed with a microscope; the cells in all the groups were in good condition and adhered firmly (Supplementary Figure 3). The result was consistent with the results of the CCK-8 assay that 0.5% CSE (Supplementary Figure 1(a)), ebeiedinone, and peimisine (10, 20, and 40 μM) (Supplementary Figure 1(c) and (d)) did not induce a decrease in BEAB-2B cell viability.

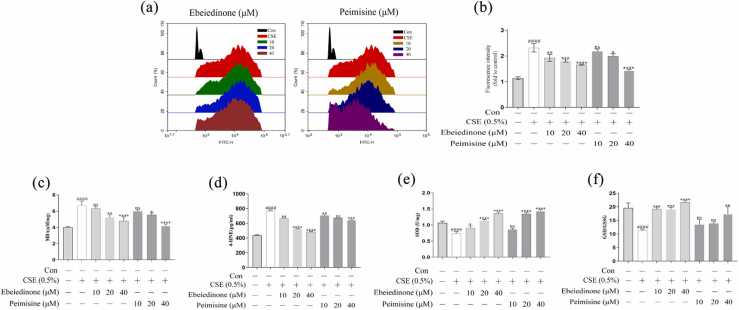

Effect of ebeiedinone and peimisine on CSE-induced oxidative stress in BEAS-2B cells

To observe the changes in oxidative stress in BEAS-2B cells and after drug interventions, BEAS-2B cells were cultured with CSE (0.5%), ebeiedinone, and peimisine (10, 20, and 40 μM) for 24 h. We measured the levels of ROS, the concentrations of malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), the activity of the total superoxide dismutase (SOD), and the ratio of glutathione (GSH)/oxidized glutathione (GSSG) by the kits according to the manufacturer's instructions. As shown in Figure 1, the content of ROS, MDA, and 4-HNE in the model group increased, while the SOD and GSH/GSSG levels decreased (P < 0.0001). Ebeiedinone and peimisine reduced the ROS, MDA, and 4-HNE content and restored the levels of SOD and GSH/GSSG. The effect of the high-dose group was better (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Effect of ebeiedinone and peimisine on BEAS-2B cells' resistance to CSE-induced oxidative damage. (a) The effect of CSE and ebeiedinone and peimisine (10, 20, and 40 μM) on ROS levels in BEAS-2B cells using 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescensin diacetate as a fluorescent probe. (b) It expresses the inhibition of ebeiedinone and peimisine on CSE-induced ROS production by relative fluorescence intensity. (c-f) The concentrations of MDA, 4-HNE, and SOD and GSH/GSSG ratio in BEAS-2B cells exposed to CSE for 24 h with ebeiedinone and peimisine (10, 20, and 40 μM) treated. The data are represented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. ####P < 0.0001 compared with the control group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 compared with the CSE group. Abbreviation used: ns, not significant.

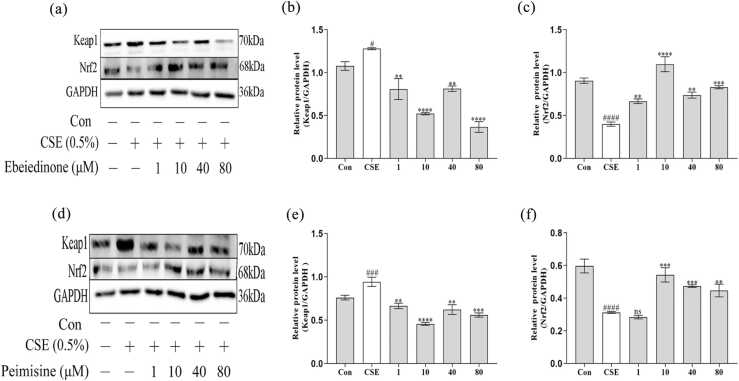

Effects of ebeiedinone and peimisine on the CSE-induced NRF2/KEAP1 and JNK/MAPK pathways in BEAS-2B cells

As demonstrated in Figure 2, compared with the control group in BEAS-2B cells, CSE stimulation caused the expression of Keap1 to increase (P < 0.05), but the expression of Nrf2 proteins showed an opposite trend (P < 0.0001). When different concentrations of ebeiedinone and peimisine (1, 10, 40, and 80 μM) were added that trend was reversed (P < 0.01). However, in Figure 2(f), there was no statistical difference when the peimisine was 1 μM (P > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

The expression of Keap1 and Nrf2 in BEAS-2B cells after being exposed to CSE for 24 h with ebeiedinone and peimisine (1, 10, 40, and 80 μM) treated. (a) and (d) Protein expressions of Keap1 and Nrf2 by western blot assay. (b) and (e) The quantified expression of Keap1/GAPDH. (c) and (f) The quantified expression of Nrf2/GAPDH. The data are represented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001, and ####P < 0.0001 compared with the control group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 compared with the CSE group. Abbreviation used: ns, not significant.

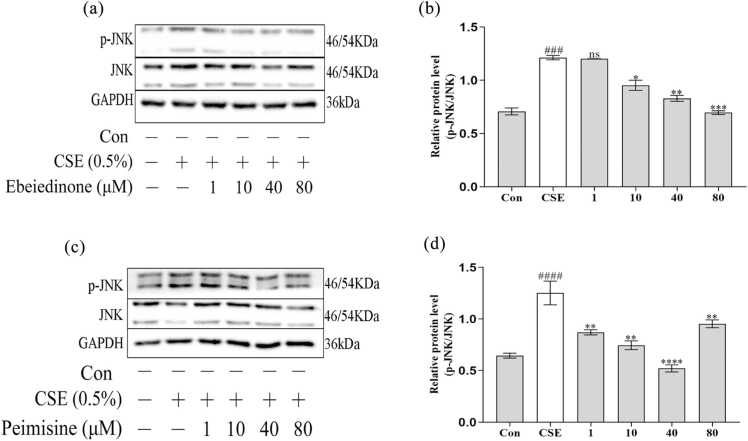

As demonstrated in Figure 3, compared with the control group in BEAS-2B cells, CSE stimulation caused the expression of p-JNK to increase (P < 0.001), but the expression of JNK proteins showed virtually no change. When different concentrations of ebeiedinone and peimisine (1, 10, 40, and 80 μM) were added that trend was reversed (P < 0.05). However, in Figure 3(b), there was no statistical difference when the ebeiedinone was 1 μM (P > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

The expression of JNK and p-JNK in BEAS-2B cells after being exposed to CSE for 24 h with ebeiedinone and peimisine (1,10, 40, and 80 μM) treated. (a) and (c) The relative protein expression of the JNK/MAPK pathway was detected by western blot assay. (b) and (d) The quantified expression of p-JNK/GAPDH. The data are represented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. ###P < 0.001 and ####P < 0.0001 compared with the control group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 compared with the CSE group. Abbreviation used: ns, not significant. (In Figures 2(d) and 3(c), protein molecular markers were used in three experiments conducted independently, and each time the same sample was in one gel. Therefore, for the immunoblotting of GAPDH in Figure 3(c), we used the one in Figure 2(d).)

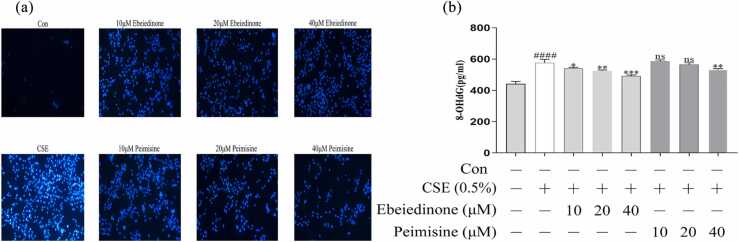

Ebeiedinone and peimisine inhibited the CSE-induced increase of the 8-hydroxy-2 deoxyguanosine level and the Hoechst 33258 assay in BEAS-2B cells

In the Hoechst 33258 assay, CSE-handled BEAS-2B cells display nuclear condensation, chromatin condensation, and apoptotic vesicles, while the intervention groups all attenuated nuclear morphological changes and even eliminated intracellular chromatin condensation (Figure 4(a)). 8-hydroxy-2 deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) is a widely used biomarker, and the levels correlate to oxidative DNA damage.29, 30 8-OHdG levels were measured to see if ebeiedinone and peimisine could repair oxidative DNA damage caused by CSE in BEAS-2B cells. As shown in Figure 4(b), CSE caused a significant increase in the 8-OHdG level compared with the control group (P < 0.0001). However, the co-treatment of ebeiedinone and peimisine reversed this trend in concentration-dependent manners. However, there was no statistical difference when the peimisine was under 40 μM (P > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Effects of ebeiedinone and peimisine on CSE-induced DNA damage in BEAS-2B cells. (a) Cells were stained with the Hoechst 33258 assay and observed under a fluorescence microscope (10× magnification) Scale bar = 10 µm. (b) The 8-OHdG levels in BEAS-2B cells induced by CSE with ebeiedinone and peimisine (10, 20, and 40 μM) treatments for 24 h. The data are represented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. ####P < 0.0001 compared with the control group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with the CSE group. Abbreviation used: ns, not significant.

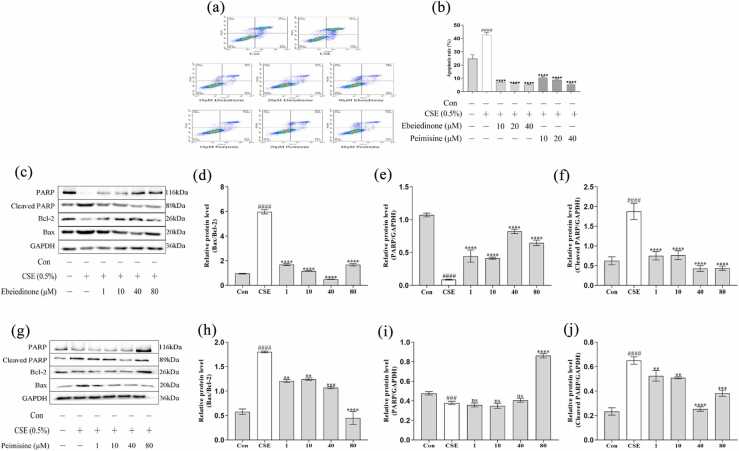

Ebeiedinone and peimisine inhibited CSE-induced apoptosis and autophagy deregulation in BEAS-2B cells

To further investigate the effect of CSE on cell apoptosis in different periods (early and terminal apoptotic cells) and the protective effects of ebeiedinone and peimisine, the apoptosis rate was detected by flow cytometry. As demonstrated in Figure 5(a) and (b), compared with the control group, CSE stimulation caused a significant increase in apoptosis in BEAS-2B cells (P < 0.0001). When different concentrations of ebeiedinone and peimisine (10, 20, and 40 μM) were added, the number of apoptotic cells and the cell apoptosis rate were significantly inhibited compared to the CSE model group (P < 0.0001). It can be seen from Figure 5(c) and (g) that the expression of Bax and Cleaved PARP proteins increased after CSE treatment for 24 h, while the expression of Bcl-2 and PARP proteins showed an opposite trend. When compared to the control, in the CSE model group, the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 significantly increased (P < 0.0001) (Figure 5(d) and (h)), the expression of PARP was reduced (P < 0.001) (Figure 5(e) and (i)), and the expression of Cleaved PARP increased (P < 0.0001) (Figure 5(f) and (j)), whereas that trend was reversed by different concentrations of ebeiedinone and peimisine (1, 10, 40, and 80 μM) compared to the CSE. However, in Figure 5(i), there was no statistical difference when the peimisine was under 80 μM (P > 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Effects of ebeiedinone and peimisine on CSE-induced cell apoptosis in BEAS-2B cells. BEAS-2B cells were co-incubated with ebeiedinone, peimisine (1, 10, 40, and 80 μM) and CSE for 24 h. (a) and (b) Cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI and flow cytometrically analyzed for cell apoptosis. (c) and (g) The levels of apoptotic proteins were detected by a western blot assay. (d) and (h) The quantified expression of Bax/Bcl-2. (e) and (i) The quantified expression of PARP/GAPDH. (f) and (j) The quantified expression of Cleaved PARP/GAPDH. The data are represented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. ###P < 0.001 and ####P < 0.0001 compared with the control group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 compared with the CSE group. Abbreviation used: ns, not significant.

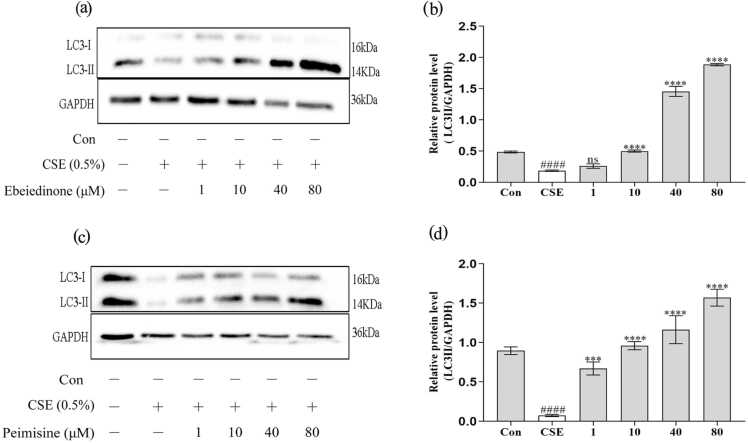

In addition, the autophagy marker protein LC3 was significantly regulated (Figure 6). CSE induction downregulated the expression of LC3-II (P < 0.0001), while the two types of isosteroidal alkaloids (ebeiedinone and peimisine) upregulated the expression of the above protein at different levels in BEAS-2B cells (P < 0.001). However, in Figure 6(b), there was no statistical difference when the ebeiedinone was 1 μM (P > 0.05).

Fig. 6.

Ebeiedinone and peimisine modulated autophagy in BEAS-2B cells after CSE damage. BEAS-2B cells were co-incubated with ebeiedinone, peimisine (1, 10, 40, and 80 μM) and CSE for 24 h. After treatment by them, the levels of autophagic proteins were determined by western blotting. (a) and (c) WB to evaluate the expression of LC3. (b) and (d) The quantified expression of LC3-II/PARP. The data are represented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. ####P < 0.0001 compared with the control group. ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001, compared with the CSE group. Abbreviation used: ns, not significant.

In summary, as presented in Figure 7, we identified that CSE can induce oxidative stress, DNA damage, and apoptosis in BEAS-2B cells. and the two types of isosteroidal alkaloids (ebeiedinone and peimisine) from FCB potentially exert pulmonary protective activity through mechanisms involved in affecting autophagy deregulation and apoptosis, which were modulated via the KEAP1/NRF2 and JNK/MAPK signaling pathways.

Fig. 7.

Mechanisms underlying the inhibitory effect of ebeiedinone and peimisine on oxidative stress, DNA damage, apoptosis, and autophagy deregulation induced by CSE.

Discussion

When the organism is stimulated by stress, it will generate excessive ROS, causing an imbalance in the oxidation and antioxidant systems, resulting in oxidative stress. The KEAP1-NRF2 system is a typical two-component system in which KEAP1 serves as the sensor for electrophiles, as the sensor for electrophiles acts as a cysteine-thiol-rich sensor of redox insults, whereas NRF2 is a transcription factor. Under nonstress conditions, NRF2 is synthesized but continuously degraded. Under electrophilic or ROS stress conditions, the active cysteine residue of KEAP1 is directly modified, which reduces the ubiquitin E3 ligase activity of the KEAP1-CUL3 complex, thereby stabilizing NRF2. De novo NRF2 can be directly translocated into the nucleus, form heterodimers with sMAF proteins, bind to antioxidant response elements or electrophilic response elements, and activate a set of phase II genes, thus functioning as a master regulatory transcription factor.31 When exposed to ROS, Keap1 releases the transcription factor NRF2, which translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus to trigger the transcription of its target genes. The levels of ROS, MDA, 4-HNE, and GSG in BEAS-2B cells were significantly increased (Figure 1). However, our results showed that ebeiedinone and peimisine treatment decreased ROS levels. In contrast, increased NRF2 levels (Figure 2). Ebeiedinone and peimisine may activate the main route for Nrf2 regulation via interactions with the Keap1 protein32; impede Nrf2 into the nucleus; reduce ROS, thus promoting NRF2 synthesis, too late to combine with NRF2 (under nonstress conditions, NRF2 will be synthesized but will continue to degrade). They may have a binding target on the cell membrane, and subsequent animal studies will provide further evidence.

The MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) pathway has three levels of signaling: the MAPK, the MAPK kinase (MEK or MKK), and the kinase of the MAPK kinase (MEKK or MKKK).33 These three kinases can be activated sequentially, and together they regulate a variety of important physiological and pathological effects such as cell growth, differentiation, stress, and inflammatory responses. There are four main branching routes of the MAPK pathway: ERK, JNK, p38/MAPK, and ERK5, of which JNK and p38 are functionally similar and are related to inflammation, apoptosis, and growth.34 CSEinduced cell death and caused consistent patterns of autophagy and JNK activation in BEAS-2B human bronchial epithelial cells.35, 36 Ebeiedinone and peimisine treatment protected bronchial epithelial cells from CSE-induced injury and inhibited activation of autophagy and upregulation of JNK phosphorylation (Figure 3).

Studies have shown that CSE induces a significant increase in the levels of 8-OHdG (Figure 4(b)) and the apoptosis rate (Figure 5(a) and (b)) in BEAS-2B cells. However, this situation was effectively reversed by different concentrations of ebeiedinone and peimisine, revealing the inhibitory effect of the two types of isosteroidal alkaloids on CSE-induced BEAS-2B cell apoptosis. The Bcl-2 family plays an important role in regulating cell apoptosis. Bax promotes apoptosis, and Bcl-2 inhibits apoptosis. Polyadenosine diphosphate ribose polymerase (PARP), a Zn2+-dependent eukaryotic DNA-binding protein that specifically recognizes and binds to DNA break ends, is a genome-monitoring and DNA-repair enzyme. Early in the onset of apoptosis, PARP is a substrate for the action of the caspase family, which can disable the DNA-repair function of PARP. In caspase-dependent pathway apoptosis, caspase3 activation generates Cleaved Caspase3, which shears PARP and promotes Cleaved PARP production. Autophagy is the process by which lysosomes phagocytose organelles and other contents to remove unwanted or dysfunctional components,37 and it is one of the most elaborative membrane remodeling systems in eukaryotic cells. Its major function is to recycle cytoplasmic material by delivering it to lysosomes for degradation. As a cellular protective survival mechanism in stressful environments, in response to environmental cues such as cytotoxicity or starvation, it maintains the homeostasis of the intracellular environment by recycling some of its own damaged organelles and proteinaceous material, which is essentially an intracellular membrane rearrangement.38 This includes autophagy initiation, autophagosome formation, autophagic lysosome formation and degradation, and reuse.39, 40, 41 As demonstrated in Figures 5(c)-(j) and 6, the two types of isosteroidal alkaloids (ebeiedinone and peimisine) significantly regulate the autophagy marker protein LC3 and apoptosis-related proteins Bax, Bcl-2, PARP, and Cleaved PARP, thereby regulating the dysregulation of autophagy and playing an anti-apoptotic role.

Our research shows that CSE-induced excessive ROS production, then upregulated the expression of Bax, Cleaved PARP, Keap1, and p-JNK proteins and downregulated the expression of Bcl-2, PARP, LC3-II, and Nrf2 proteins in BEAS-2B cells, which in turn increased the lipid oxidation products MDA and 4-HNE and decreased the values of antioxidant enzymes SOD and GSH/GSSG, thus causing an increase in cellular 8-OHdG protein expression and apoptosis rate. In summary, as presented in Figure 7, we identified that the two types of isosteroidal alkaloids (ebeiedinone and peimisine) from FCB potentially exert pulmonary protective activity through mechanisms involved in affecting autophagy deregulation and apoptosis, which were modulated by the KEAP1/NRF2 and JNK/MAPK signaling pathways.

Mechanisms underlying the inhibitory effect of ebeiedinone and peimisine on oxidative stress induced by cigarette smoke are to activate the KEAP1/NRF2 and JNK/MAPK signaling pathways in BEAS-2B cells. However, we only detected cell proliferation and toxicity (using the CCK-8 technique), not cell cycle or apoptosis. These two compounds’ chemicals could have diverse mechanistic effects on cell activity. Further studies are required to confirm that a similar protective effect of ebeiedinone and peimisine occurs in the lungs in vivo in response to CS exposure.

Conclusion

In summary, these results showed that the activated oxidative stress process was critical in CSE-induced BEAS-2B cell DNA damage and apoptosis, as well as the progression of COPD. However, ebeiedinone and peimisine can protect against CS-induced COPD by suppressing autophagy deregulation and apoptosis through regulation of the KEAP1/NRF2 and JNK/MAPK signaling pathways. More detailed information will be provided through animal experiments in the future.

Materials and methods

Materials and reagents

The standards of ebeiedinone (purity 99.63%) and peimisine (purity 99.60%) were purchased from Chengdu Must Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, Sichuan, China). The cell counting kit (CCK-8) was purchased from APExBIO (Houston, USA). Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and phosphatase inhibitors were purchased from Solaribo Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). A reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay kit, Radio Immunoprecipitation Assay buffer, bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein kit, malondialdehyde (MDA) detection kit, total superoxide dismutase (SOD) detection kit, glutathione (GSH) and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) assay kits, and Hoechst 33258 were obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and 8-hydroxy-2 deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) were purchased from Wuhan Colorful Gene Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). The Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptotic detection kit was purchased from Dojindo (Japan). The GAPDH was obtained from Affinity Bioreagents Technology (Colorado, USA). Antibodies (anti-Bax, anti-Bcl-2) were purchased from HuaBio Technology (Hangzhou, China), (anti-PARP, anti-Cleaved-PARP, anti-LC3A/B, and anti-JNK) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Boston, USA), and (anti-Nrf2 and anti-Keap1) were obtained from Affinity Biosciences (Nanjing, China). Anti-p-JNK was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). The goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody HRP conjugated was obtained from Signalway Antibody LLC (Maryland, USA). Immobilon Western HRP substrate peroxide solution was obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). All the other reagents used in this experiment were of analytical grade.

Preparation of CSE

CSE was prepared in accordance with the previously established protocol with minor modifications.42, 18, 43, 44 Using self-made vacuum equipment, one Jiaozi Filter cigarette (10 mg tar, 1.0 mg nicotine content, and 11 mg CO) from China Tobacco Sichuan Industrial Co., Ltd. (Sichuan, China) was continuously aspirated with a 50 mL syringe, and all the smoke extracted was dissolved in 5 mL of serum-free Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium. After thorough shaking and mixing, the pH of the CSE was corrected to 7.4. The medium was filtered via a 0.22 µm microporous membrane at 100% concentration. For each experiment, CSE was newly produced before use.

Cell culture and cytotoxicity assay

BEAS-2B cells were obtained from the China Cell Line Bank (Beijing, China). RPMI 1640 medium, fetal bovine serum, and penicillin-streptomycin solution were purchased from Gibco (Grand Island, USA). BEAS-2B cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2.

A cytotoxicity assay was performed on BEAS-2B cells. In brief, 5.0 × 103 BEAS-2B cells were plated in a 96-well plate overnight, and the cell viability was measured according to the CCK-8 instructions after 24 h of exposure to CSE (0%, 0.2%, 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 2.5%, 5%, 10%, 20%, 40%, and 100%), DMSO (0%, 0.1%, 0.25%, and 0.5%), ebeiedinone, and peimisine (0, 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 100 μM). The control groups were cultured with equal volumes of the medium, and no less than four replicate wells were set up for each group. A total of 10 μL CCK-8 was added to each well, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using the K3 TOUCH microplate reader (Thermo, American). The cell viability was calculated according to the following formula: cell viability (%) = (Abs 450 of treated cells/Abs 450 of control cells) × 100%.

Evaluation of ROS by flow cytometry

BEAS-2B cells were inoculated into 6-well plates at 3 × 105 cells/well and cultured to 70% confluence, then CSE was produced to create an in vitro oxidative stress model. BEAS-2B cells were stimulated with different doses of CSE (0%, 0.2%, 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 5%, and 10%) for 24 h. Cells were incubated with 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescensin diacetate (10 μM) for 25 min at 37 °C in the dark, and then cells were washed twice with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and collected. The Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptotic detection kit was purchased from Dojindo (Japan). The fluorescence intensity of each group was detected by flow cytometry (ACEA NovoCyte, Agilent, USA) at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm; the obtained results were analyzed with the NovoExpress software (Agilent, USA); and the content of ROS was compared to determine the optimal concentration of CSE-stimulated BEAS-2B cells.

Cell morphology observation

The BEAS-2B cells were seeded on a cell slide in a 6-well plate at 3 × 105 cells/well and cultured to 70% confluence. BEAS-2B cells were co-incubated with 0.5% CSE, ebeiedinone, and peimisine (10, 20, and 40 μM) for 24 h. Then, the cell morphology of groups was observed by an Ts2-FL microscope (10× magnification, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Measurement of ROS, MDA, SOD, and GSH/GSSG levels

The BEAS-2B cells were seeded on a cell slide in a 6-well plate at 3 × 105 cells/well and cultured to 70% confluence. BEAS-2B cells were co-incubated with 0.5% CSE, ebeiedinone, and peimisine (10, 20, and 40 μM) for 24 h before ROS, MDA, SOD, and GSH/GSSG levels were measured using the kits according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The BEAS-2B cells were seeded on a cell slide in a 6-well plate at 3 × 105 cells/well and cultured to 70% confluence. BEAS-2B cells were cultured with 0.5% CSE and various dosages of ebeiedinone and peimisine (10, 20, and 40 μM), then collected cell supernatant after 24 h. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the levels of 4-HNE and 8-OHdG were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Hoechst 33258 staining assay

After being treated with 0.5% CSE and different doses of ebeiedinone and peimisine (10, 20, and 40 μM) for 24 h, the cells were washed twice with PBS before being fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. Then, cells were washed with PBS and stained with a 500 μL Hoechst 33258 solution for 10 min. Ultimately, the images were obtained with a Ts2-FL fluorescence microscope at an excitation wavelength of 350 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm (10× magnification, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Apoptosis assay

Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis after treatment with 0.5% CSE, ebeiedinone, and peimisine (10, 20, and 40 μM) for 24 h, then cells were washed twice with PBS. Then, the cells were suspended with Annexin V-FITC and PI. According to the manufacturer’s instructions from the kit, collected cells were suspended in 5 μL of Annexin V binding buffer for 20 min in the dark. Then, the cells were stained with 2 μL of PI and evaluated by FACS. The apoptosis rate was detected by flow cytometry (ACEA NovoCyte, Agilent, USA).

Western blot analysis

Cell samples were lysed in Radio Immunoprecipitation Assay buffer with 1% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 1% phosphatase inhibitors for 30 min. The bicinchoninic acid method was used to determine the protein concentration according to the assay instructions. After quantification and separation, protein samples were electrophoresed on sodium dodecyl sulfate- polyacrylamide gel electrop horesis and transferred to the polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, USA), which were blocked with 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with the specific primary antibody overnight. The membranes were subsequently incubated with the following primary antibodies against Nrf2 and Keap1(1:1000, ImmunoWay, Affinity Biosciences, China), Bax and Bcl-2 (1:1000, Huaan Biotechnology, Hangzhou, China), PARP, Cleaved-PARP, LC3A/B, and JNK (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA), p-JNK (1:1000, ABclonal, Wuhan, China), and GAPDH (1:5000, Ibid.) at 4 °C overnight. Subsequently, the membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody solution at room temperature for 1.5 h. Finally, the proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescent (Millipore, USA) and detected by ChemiScope 6100 imaging system (Clinx, Shanghai, China). The band intensities were quantified using ImageJ gel analysis software.

Statistical analysis

Except for the analysis software used for annotation, all data were statistically analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism 8.0 and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of at least three independently performed experiments. Data analysis was performed by one-way analysis of variance. For the comparison of two groups, a student’s t-test was used. Differences with P values <0.05 were statistically significant.

Funding and support

This experiment was supported by the Major science and technology research project in 2021 from Tibet Science and Technology (No. XZ202101ZD0021G), the Science and Technology Major Project of Tibetan Autonomous Region of China (Nos. XZ202201ZD0001G01 and XZ202201ZD0001G06), the Funds for local scientific and technological development guided by the central government in 2023 from Tibet Science and Technology Department (No. XZ202301YD0014C), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81860567 and 82060588), the central government supports the talent development plan for local Everest scholars—the development plan for young doctors-the high-level talent cultivation project of Tibet University (No. zdbs202216), the special fund for strategic cooperation between Sichuan University and Da Zhou Municipal Government (No. 2021CDDZ-13), and the Major science and technology research project in 2023 from Tibet Science and Technology Department (No. XZ202301ZY0009G).

Author contributions

Kathy Wai Gaun Tse and Wai Ming Tse: Supervision. Erbu Aga: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Data curation. Xiaomu Zhu: Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Chuanlan Liu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Bengui Ye: Resources, Data curation. Yanyong Liu: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Investigation, Formal analysis.

Declarations of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jun He from the Cancer Center, the Collaborative Innovation Center for Biotherapy, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, and all our colleagues and friends for their encouragement, support, and assistance throughout the entire experiment and writing process. We also thank the West China School of Pharmacy at Sichuan University for providing technical support and the research platform for this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.cstres.2024.10.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary Data

Supplementary material

.

Data availability

No data were used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Lokke A., Lange P., Scharling H., Fabricius P., Vestbo J. Developing COPD: a 25 year follow up study of the general population. Thorax. 2006;61:935–939. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.062802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comstock G.W., Brownlow W.J., Stone R.W., Sartwell P.E. Cigarette smoking and changes in respiratory findings. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:802–809. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mariani T.J. Respiratory disorders: ironing out smoking-related airway disease. Nature. 2016;531:586–587. doi: 10.1038/nature17309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Margham J., McAdam K., Forster M., et al. Chemical composition of aerosol from an E-cigarette: a quantitative comparison with cigarette smoke. Chem Res Toxicol. 2016;29:1662–1678. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlagintweit H.E., Tyndale R.F., Hendershot C.S. Acute effects of a very low nicotine content cigarette on laboratory smoking lapse: Impacts of nicotine metabolism and nicotine dependence. Addict Biol. 2021;26 doi: 10.1111/adb.12930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magallon M., Navarro-Garcia M.M., Dasi F. Oxidative stress in COPD. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1953. doi: 10.3390/jcm8111953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adcock I.M., Mumby S., Caramori G. Breaking news: DNA damage and repair pathways in COPD and implications for pathogenesis and treatment. Eur Respir J. 2018;52 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01718-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Comer D.M., Kidney J.C., Ennis M., Elborn J.S. Airway epithelial cell apoptosis and inflammation in COPD, smokers and nonsmokers. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:1058–1067. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00063112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strulovici-Barel Y., Staudt M.R., Krause A., et al. Persistence of circulating endothelial microparticles in COPD despite smoking cessation. Thorax. 2016;71:1137–1144. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-208274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yasuda N., Gotoh K., Minatoguchi S., et al. An increase of soluble Fas, an inhibitor of apoptosis, associated with progression of COPD. Respir Med. 1998;92:993–999. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90343-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang Y., Cai Q.H., Wang Y.J., et al. Protective effect of autophagy on endoplasmic reticulum stress induced apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells in rat models of COPD. Biosci Rep. 2017;37 doi: 10.1042/BSR20170803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Christenson S.A., Smith B.M., Bafadhel M., Putcha N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2022;399:2227–2242. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00470-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stolz D., Mkorombindo T., Schumann D.M., et al. Towards the elimination of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2022;400:921–972. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01273-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brusselle G.G., Humbert M. Classification of COPD: fostering prevention and precision medicine in the Lancet Commission on COPD. Lancet. 2022;400:869–871. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01660-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang L., Zhang M., Yang T., Wai Ming T., Wai Gaun T.K., Ye B. LC-MS/MS coupled with chemometric analysis as an approach for the differentiation of bulbus Fritillaria unibracteata and Fritillaria ussuriensis. Phytochem Anal. 2021;32:957–969. doi: 10.1002/pca.3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu C., Liu S., Tse W.M., et al. A distinction between Fritillaria Cirrhosa Bulbus and Fritillaria Pallidiflora Bulbus via LC-MS/MS in conjunction with principal component analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis. Sci Rep. 2023;13:2735. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-29631-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu K., Mo C., Xiao H., Jiang Y., Ye B., Wang S. Imperialine and verticinone from bulbs of Fritillaria wabuensis inhibit pro-inflammatory mediators in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Planta Med. 2015;81:821–829. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1546170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S., Yang T., Ming T.W., et al. Isosteroid alkaloids from Fritillaria cirrhosa bulbus as inhibitors of cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress. Fitoterapia. 2020;140 doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2019.104434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou A., Li X., Zou J., Wu L., Cheng B., Wang J. Discovery of potential quality markers of Fritillariae thunbergii bulbus in pneumonia by combining UPLC-QTOF-MS, network pharmacology, and molecular docking. Mol Divers. 2024;28:787–804. doi: 10.1007/s11030-023-10620-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang D., Du Q., Li H., Wang S. The isosteroid alkaloid imperialine from bulbs of Fritillaria cirrhosa Mitigates pulmonary functional and structural impairment and suppresses inflammatory response in a COPD-like rat model. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/4192483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin Q., Qu M., Zhou B., et al. Exosome-like nanoplatform modified with targeting ligand improves anti-cancer and anti-inflammation effects of imperialine. J Control Release. 2019;311-312:104–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan S., Tse W.M., Gaun Tse K.W., et al. Ethanol extracts of bulbus of Fritillaria cirrhosa protects against pulmonary fibrosis in rats induced by bleomycin. J Funct Foods. 2022;97 doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2022.105239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quan Y., Li L., Yin Z., et al. Bulbus Fritillariae Cirrhosae as a respiratory medicine: is there a potential drug in the treatment of COVID-19? Front Pharmacol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.784335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen T., Zhong F., Yao C., et al. A systematic review on traditional uses, sources, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity of Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/1536534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin X., Gao X., Lan M., Li C.N., Sun J.M., Zhang H. Study the mechanism of peimisine derivatives on NF-kappaB inflammation pathway on mice with acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2022;99:717–726. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.14013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin B.Q., Ji H., Li P., Fang W., Jiang Y. Inhibitors of acetylcholine esterase in vitro--screening of steroidal alkaloids from Fritillaria species. Planta Med. 2006;72:814–818. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-947168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu F.J., Chen X.Y., Yang J., et al. Revealing active components and action mechanism of Fritillariae Bulbus against non-small cell lung cancer through spectrum-effect relationship and proteomics. Phytomedicine. 2023;110 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xian M., Xu J., Zheng Y., et al. Network pharmacology and experimental verification reveal the regulatory mechanism of ChuanbeiMu in treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2024;19:799–813. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S442191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prabhulkar S., Li C.Z. Assessment of oxidative DNA damage and repair at single cellular level via real-time monitoring of 8-OHdG biomarker. Biosens Bioelectron. 2010;26:1743–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu D., Liu B., Yin J., et al. Detection of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) as a biomarker of oxidative damage in peripheral leukocyte DNA by UHPLC-MS/MS. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2017;1064:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto M., Kensler T.W., Motohashi H. The KEAP1-NRF2 system: a thiol-based sensor-effector apparatus for maintaining redox homeostasis. Physiol Rev. 2018;98:1169–1203. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ulasov A.V., Rosenkranz A.A., Georgiev G.P., Sobolev A.S. Nrf2/Keap1/ARE signaling: towards specific regulation. Life Sci. 2022;291 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.120111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim H.J., Bar-Sagi D. Modulation of signalling by Sprouty: a developing story. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:441–450. doi: 10.1038/nrm1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson G.L., Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science. 2002;298:1911–1912. doi: 10.1126/science.1072682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen C.H., Li Y.R., Lin S.H., et al. Tiotropium/Olodaterol treatment reduces cigarette smoke extract-induced cell death in BEAS-2B bronchial epithelial cells. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2020;21:74. doi: 10.1186/s40360-020-00451-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grenier A., Morissette M.C., Rochette P.J., Pouliot R. The combination of cigarette smoke and solar rays causes effects similar to skin aging in a bilayer skin model. Sci Rep. 2023;13 doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-44868-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wollert T. Autophagy. Curr Biol. 2019;29:R671–R677. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moparthi S.B., Wollert T. Reconstruction of destruction - in vitro reconstitution methods in autophagy research. J Cell Sci. 2018;132 doi: 10.1242/jcs.223792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langlois C.R., Wollert T. Digesting cytotoxic stressors - an unconventional mechanism to induce autophagy. FEBS J. 2016;283:3886–3888. doi: 10.1111/febs.13919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matscheko N., Mayrhofer P., Rao Y., Beier V., Wollert T. Atg11 tethers Atg9 vesicles to initiate selective autophagy. PLoS Biol. 2019;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rao Y., Perna M.G., Hofmann B., Beier V., Wollert T. The Atg1-kinase complex tethers Atg9-vesicles to initiate autophagy. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kode A., Rajendrasozhan S., Caito S., Yang S.R., Megson I.L., Rahman I. Resveratrol induces glutathione synthesis by activation of Nrf2 and protects against cigarette smoke-mediated oxidative stress in human lung epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L478–L488. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00361.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu J., Xu H., Wong P.F., Xia S., Xu J., Dong J. Icaritin attenuates cigarette smoke-mediated oxidative stress in human lung epithelial cells via activation of PI3K-AKT and Nrf2 signaling. Food Chem Toxicol. 2014;64:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu W.T., Li C.H., Dai T.T., et al. Effect of allyl isothiocyanate on oxidative stress in COPD via the AhR/CYP1A1 and Nrf2/NQO1 pathways and the underlying mechanism. Phytomedicine. 2023;114 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2023.154774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

No data were used for the research described in the article.