Abstract

In 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and state and local health and regulatory partners investigated an outbreak of Salmonella enterica serovar Oranienburg infections linked to bulb onions from Mexico, resulting in 1040 illnesses and 260 hospitalizations across 39 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. The Kansas Department of Agriculture recovered the outbreak strain of Salmonella Oranienburg from a sample of condiment collected from an ill person’s home. The condiment was made with cilantro, lime, and onions, but, at the time of collection, there were no onions remaining in it. FDA conducted traceback investigations for white, yellow, and red bulb onions, cilantro, limes, tomatoes, and jalapeño peppers. Growers in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, were identified as supplying the implicated onions that could account for exposure to onions for all illnesses included in the traceback investigation, but investigators could not determine a single source or route of contamination. FDA collected product and environmental samples across the domestic supply chain but did not recover the outbreak strain of Salmonella. Binational collaboration and information sharing supported Mexican authorities in collecting environmental samples from two packing plants and onion, water, and environmental samples from 15 farms and firms in Chihuahua, Mexico identified through FDA’s traceback investigation, but did not recover the outbreak strain.. Distributors of the implicated onions issued voluntary recalls of red, yellow, and white whole, fresh onions imported from the state of Chihuahua, Mexico. This outbreak showcased how investigators overcame significant traceback and epidemiologic challenges, the need for strengthening the ongoing collaboration between U.S. and Mexican authorities and highlighted the need for identifying practices across the supply chain that can help improve the safety of onions.

Keywords: Salmonella oranienburg, Onions, Foodborne illness outbreaks

1. Introduction

Onions (Allium cepa L.) have long been consumed as a vegetable and included in a variety of food dishes worldwide (Zhao et al., 2021). In the United States, onions are available year-round through domestic production (National Onion Association, 2017). Mexico, Peru, and Canada are major onion producing countries exporting onions to the United States, and in 2019 imported onions totaled about 543,343 metric tons, valued at roughly $431 million (Federal Register, 2021). In 2019, the United States onion production was valued at roughly $1.0 billion (U.S. National Agricultural Statistic Service, 2023).

Non-typhoidal Salmonella spp. are estimated to cause roughly one million foodborne illnesses annually in the United States (Scallan et al., 2011). Approximately two-thirds of non-typhoidal Salmonella illnesses are attributed to food, with an increasing proportion of these infections linked to produce (Beshearse et al., 2021; Dyda et al., 2020). While foodborne illness outbreaks linked to bulb onions are not common, there have been outbreaks linked to the consumption of onions in the past. In 2009, uncooked diced onions used for hamburgers at a fast-food chain restaurant were linked to an outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections in Canada (North Bay Parry Sound District Health Unit, 2009); in 2016, a multistate outbreak of listeriosis was linked to frozen vegetables; frozen diced onions were recalled as part of the investigation (U. S. Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 2016); and in 2020, a Salmonella Newport outbreak was linked to consumption of whole onions in the United States and Canada (McCormic et al., 2022; U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2020a). In the past, Salmonella spp. and Listeria monocytogenes isolates have been recovered from product and environmental samples and have led to recalls of fresh-cut onions and onions in vegetable mixtures (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2012; 2018a; 2018b).

In 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and state and local health and regulatory partners investigated an outbreak of Salmonella enterica serovar Oranienburg infections linked to bulb onions from the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, resulting in 1040 illnesses and 260 hospitalizations across 39 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. Here, we report the details of this investigation with a focus on the traceback analysis that determined the source of the contaminated onions and the laboratory findings that helped support public health actions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Epidemiologic investigation

PulseNet, the national molecular subtyping network for foodborne disease surveillance, was used to identify outbreak-associated cases (U. S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). A case was defined as an infection with Salmonella Oranienburg yielding an isolate highly related to the outbreak strain, within 0–6 alleles, by core genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST) with dates of illness onset during May 31, 2021, to January 1, 2022. Local and state public health officials interviewed ill people using state-specific enteric disease questionnaires, the National Hypothesis Generating Questionnaire (NHGQ), and a focused questionnaire to identify foods commonly eaten in the week before illness and collect detailed information for foods of most interest.

2.2. Traceback investigations

Traceback investigations were conducted on food items of interest to identify whether foods eaten by ill people came from a common source (Council to Improve Foodborne Outbreak Response, 2020; Irvin et al., 2021). Traceback candidates were selected based on a review of their illness history, available purchase and meal history, and exposure to each suspected food at points of service (POS). Purchase and production records included, but were not limited to, handwritten receipts, recipes for multi-ingredient foods like salsa and guacamole, invoices, bills of lading, and electronic spreadsheets, which were collected by investigators from retailers and distributors along the supply chain. Information relevant to the traceback timeline construction collected from implicated firms along the supply chain included stock rotation, delivery frequency, and shelf-life of product.

2.3. Firm investigations

Three state investigators accompanied FDA, after the outbreak had concluded, for four investigations at three domestic firms (Importer D, Grower A, and Grower AA) and one distributor (Distributor A) identified through the traceback investigation. These investigations entailed record, product, and environmental sample collection. As a result of the traceback investigations, FDA identified three firms that imported onions from Mexico and inspected them under the Foreign Supplier Verification Program (FSVP) rule (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2020b).

In Mexico, the Federal Commission for the Protection from Sanitary Risks, called COFEPRIS (based on the Spanish acronym), in conjunction with state inspectors from Chihuahua, conducted two investigations at two onion packing houses identified by the FDA traceback investigation. During the two investigations, environmental and water samples, and process control records were collected; product samples were not collected at the time of the investigations since the onion-packing season in the region had already ended.

Investigators from the National Service of Agro-Alimentary Health, Safety and Quality, known as SENASICA (based on the Spanish acronym), conducted follow up inspections at four growers located in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, and one located in the state of Guanajuato, Mexico. These firms were identified early in the FDA traceback investigation but were not ultimately confirmed to be associated with the implicated onions that caused the illnesses and therefore not part of the traceback diagram.

2.4. Laboratory investigation

2.4.1. Clinical isolates

Salmonella isolates from ill people were sent to PulseNet-affiliated public health laboratories and further characterized by whole genome sequencing (WGS) using standard methods; results were submitted to the PulseNet national database (Besser et al., 2019; Tolar et al., 2019; U. S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016).

2.4.2. FDA, state, and Mexico samples

During the U.S. led outbreak response efforts that took place from September 2021 to February 2022, state and FDA laboratories used the FDA Bacteriological Analytical Manual (BAM) method to test for Salmonella spp. from food samples and environmental samples collected by investigators at various points in the supply chain, including POS, distribution centers, and farms (Andrews et al., 2021). Samples were collected depending on availability and the number of samples varied accordingly. Serotyping and phylogenetic analyses of WGS data (Davis et al., 2015) were conducted to characterize the isolates and compare them to clinical and historical product sample isolates (Andrews et al., 2021; Crowe et al., 2017).

Similarly, between October 2021 and January 2022, Mexican government authorities also used the FDA BAM method for Salmonella spp. testing of samples (Andrews et al., 2021); subsequently, Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR-rt) was performed in the BAX System equipment (Hygiena, 2021) to analyze water and environmental samples collected from onion production facilities located in Chihuahua, Mexico.

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiologic investigation

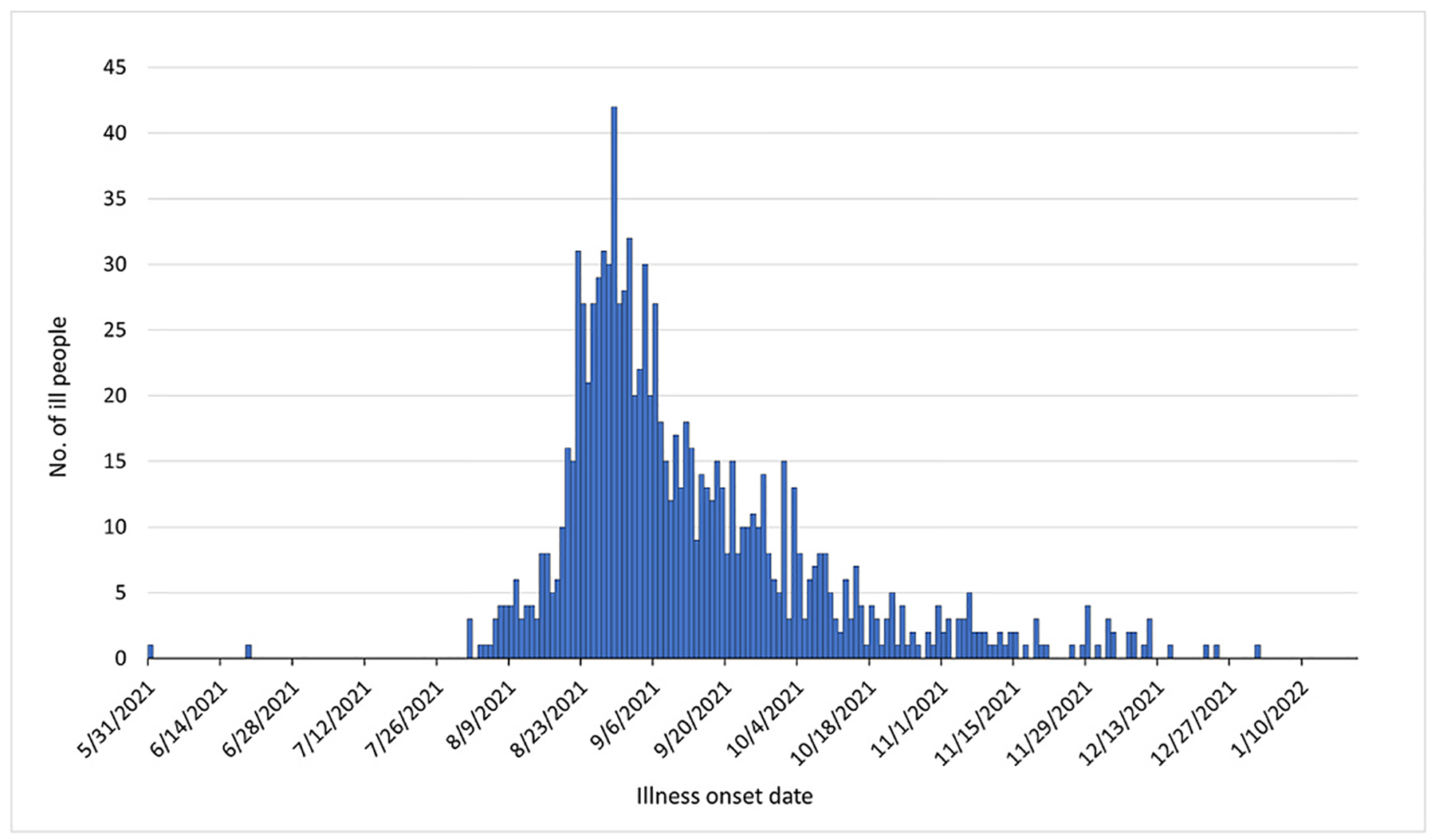

A total of 1040 ill people were reported in 39 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico (Fig. 1). Dates of illness onset ranged from May 31, 2021, to January 1, 2022 (Fig. 2). Ill people ranged in age from less than 1 year to 101 years, with a median age of 38 years; 58% were female. Of 778 people with information available, 260 (33%) were hospitalized, and no deaths were reported. Illness subclusters were identified at 25 restaurants where onions were supplied; 16 of these restaurants served Mexican-style cuisine. Overall, 294 of 407 (72%) ill people interviewed with a focused questionnaire reported consuming or maybe consuming raw onions or foods likely to contain them in the week before illness onset.

Fig. 1.

People infected with the outbreak strain of Salmonella Oranienburg, by date of illness onset, May 31, 2021, to January 1, 2022 (n = 1040).

Fig. 2.

People infected with the outbreak strain of Salmonella Oranienburg, 2021–2022 by state of residence (n = 1040).

3.2. Early state laboratory findings

The Kansas Department of Agriculture (KDA) Food Safety and Lodging investigators collected samples from an ill person’s leftover takeout meal which included rice, beans, steak, tortillas, pork, and a separate condiment container that consisted of lime and cilantro and reportedly previously had contained onions, but none were left to be sampled. The samples were negative for Salmonella spp., except for the condiment sample which yielded Salmonella Oranienburg and was highly related by cgMLST to the outbreak strain. The meal items included in this sample were obtained from an ill person who indicated the items were purchased at POS A.

3.3. Traceback investigation

Early in the investigation, investigators identified a signal for restaurants serving Mexican-style cuisine, including several restaurants linked to illness subclusters. One of these restaurant subclusters included POS A, the restaurant in Kansas linked to the Salmonella-contaminated condiment sample. Investigators reviewed available information on the meals ill people reported eating at subcluster restaurants, including menus and recipes when available, to identify the most common foods and ingredients eaten by ill people. This information was used in conjunction with information on the ingredients known to have been in the container with the Salmonella-positive condiment sample to identify commodities of interest for inclusion in the traceback investigation. Multiple produce ingredients were often served and consumed together in meals reported by ill people, and the collinearity among ingredients made it difficult to narrow the focus to a single commodity. As a result, traceback investigations for five produce commodities were conducted, including white, yellow, and red bulb onions, cilantro, limes, tomatoes, and jalapeño peppers. Of the 12 total POS included in the traceback investigations 11 POS were linked to illness subclusters, which strengthened the traceback investigation. Ill persons that consumed multiple component foods, such as guacamole or salsa, may not have reported eating cilantro or onions even though both of those items were usually included in those recipes. This fact led to the inclusion of the above ingredients in the traceback even if they were not reported by ill people. Therefore, stealth ingredients were a significant consideration in the traceback investigation, similar to past outbreaks (White et al., 2021).

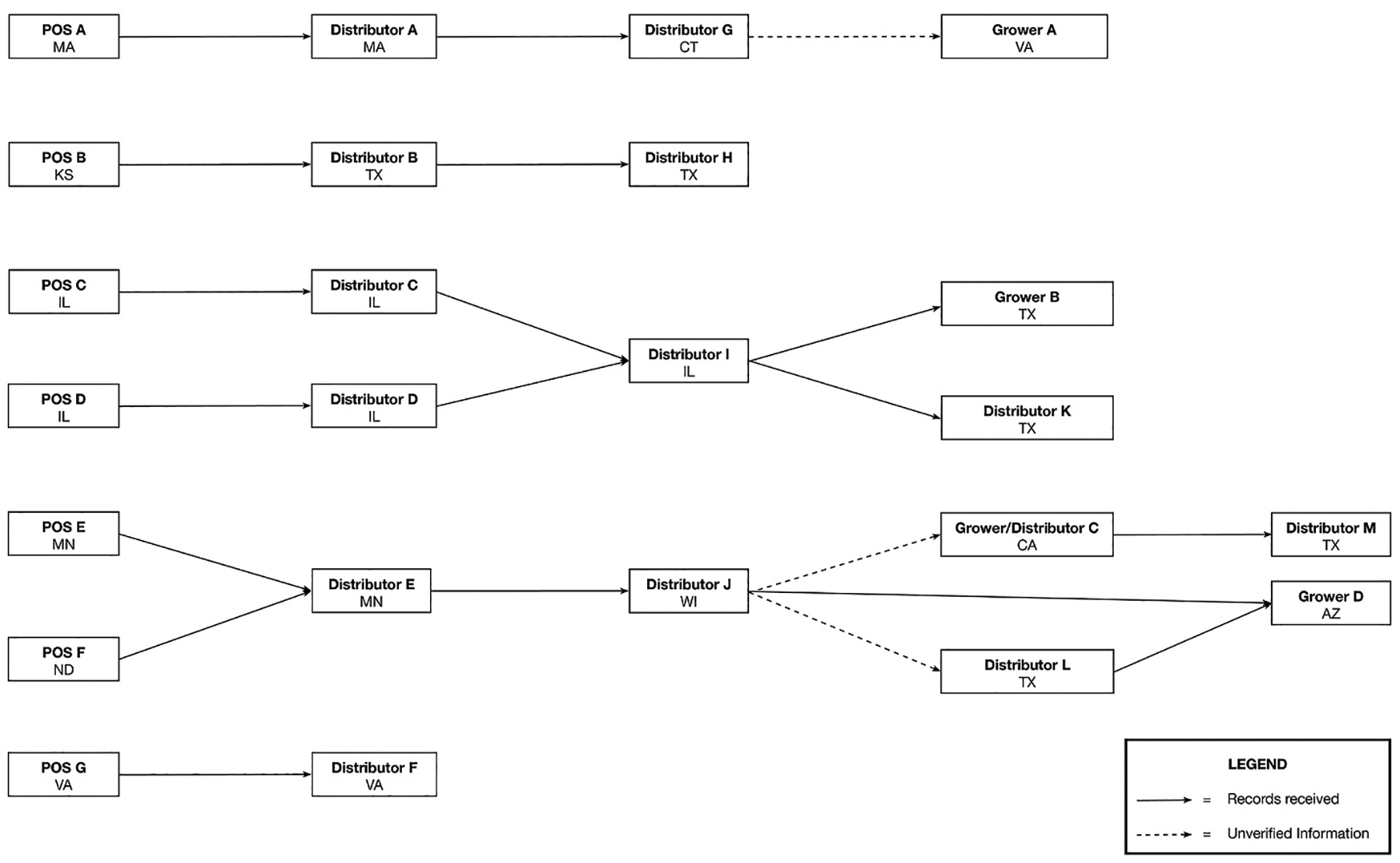

The traceback investigation for fresh and dried cilantro included 11 POS associated with 59 ill people across nine states (Fig. 3). Fresh or dried cilantro was not used at all POS and could not explain several of the illnesses in the traceback investigation.

Fig. 3.

Traceback diagram of cilantro for multistate outbreak of Salmonella Oranienburg infections in the United States, 2021–2022. Purchases of implicated products are traced from the point of service (POS), through the distribution chain, to distributors and importers. Product originates from growers that are denoted on the right side of the diagram.

The traceback investigation for limes included seven POS associated with 36 ill people across six states (Fig. 4). Limes were initially an exposure item of interest due to their presence in the leftover condiment sample from POS A that yielded the outbreak strain. However, limes were not supplied to all POS included in the traceback. Further, fresh limes were only used in cocktails at POS I, and none of the ill persons associated with that subcluster reported consuming cocktails. In addition, the characteristics of limes’ surface and their low pH made limes an unlikely vehicle for Salmonella spp. infections (Bennett et al., 2003; Danyluk, 2019; Ma et al., 2010).

Fig. 4.

Traceback diagram of limes for multistate outbreak of Salmonella Oranienburg infections in the United States, 2021–2022. Purchases of implicated products are traced from the point of service (POS), through the distribution chain, to distributors and importers. Product originates from growers that are denoted on the right side of the diagram.

The traceback investigation for tomatoes included seven POS associated with 28 outbreak-associated ill people across seven states (Fig. 5). Tomatoes were initially included in the traceback investigation because they were component ingredients in meals reported by ill people and because of historical outbreaks of Salmonella spp. infections linked to tomatoes (Behravesh et al., 2012; Bennett et al., 2015). However, there were a large variety of tomato types supplied to each POS and exposure to tomatoes could not account for all illnesses.

Fig. 5.

Traceback diagram of tomatoes for multistate outbreak of Salmonella Oranienburg infections in the United States, 2021–2022. Purchases of implicated products are traced from the point of service, through the distribution chain, to distributors and importers. Product originates from growers that are denoted on the right side of the diagram.

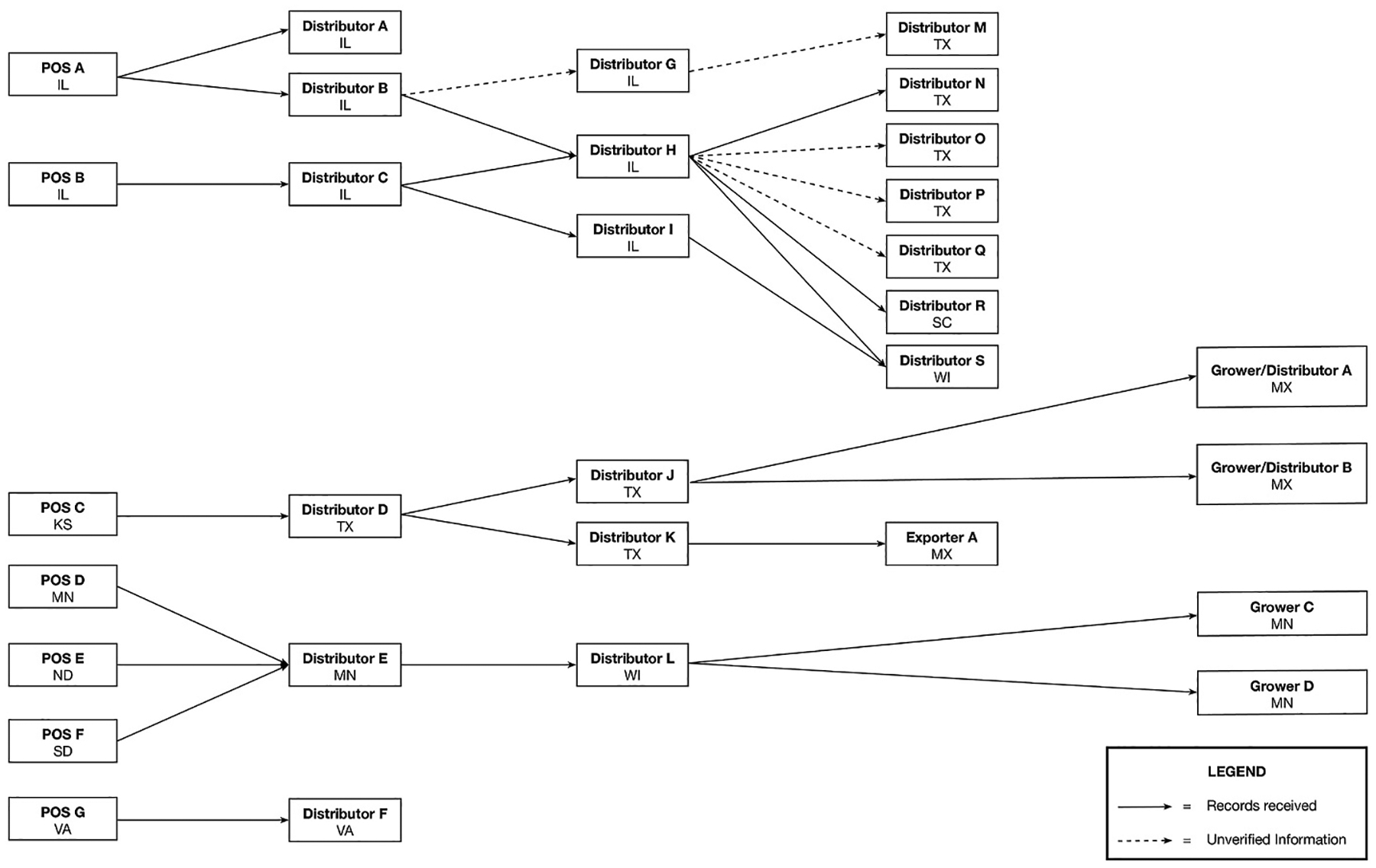

The traceback investigation for jalapeño peppers included seven POS associated with 35 outbreak-associated ill people across six states (Fig. 6). Jalapeños were a component ingredient in many food items reported by ill people. In general, the jalapeños provided to the seven POS included in traceback were imported from Mexico, but several POS may have also been supplied with domestic jalapeños (Fig. 6). However, jalapeños could not explain all illnesses and were not supplied to all POS included in the overall traceback investigation.

Fig. 6.

Traceback diagram of jalapeño peppers for multistate outbreak of Salmonella Oranienburg infections in the United States, 2021–2022. Purchases of implicated products are traced from the point of service (POS), through the distribution chain, to distributors and importers. Product originates from growers that are denoted on the right side of the diagram.

The traceback investigation conducted for white, yellow, and red onions included 12 POS associated with 62 ill people across ten states with exposure to onions (Fig. 7). Onions were supplied to the POS by 33 distributors, with five POS determined to be supplied by Importer D and seven by Distributor AA. Both Distributor AA and Importer D ultimately imported from farms located in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico. Based on GPS and address information provided by relevant firms, the farms were all within 110 miles of each other. While suppliers in the Chihuahua region of Mexico were identified as supplying the implicated onions that could account for all illnesses included in the traceback investigation, investigators were unable to determine a single point or source of contamination.

Fig. 7.

Traceback diagram for multistate outbreak of Salmonella Oranienburg infections in the United States linked to bulb onions imported from Mexico in 2021. Purchases of implicated products are traced from the point of service (POS), through the distribution chain, to distributors and importers. Product originates from growers that are denoted on the right side of the diagram.

3.4. Firm investigations

Records were collected from 31 firms as part of the traceback investigation. FDA investigators, in conjunction with state partners, investigated Distributor A, Importer D, Grower A, and Grower AA (Fig. 7), which were identified during the traceback investigation. Distributor A initially indicated it did not receive onions imported from Mexico, however, subsequent investigation indicated Distributor A received onions from Distributor AA, which imported onions from Chihuahua, Mexico. Approximately 70% of onions from Importer D were sourced from farms in Chihuahua, Mexico, but the remaining onions were sourced domestically, including farms operated by this importer. Importer D indicated that the domestically sourced onions and the imported onions were not co-mingled. In addition, Importer D indicated onions from farms in Mexico arrived in bulk bins that were cleaned and sanitized at the beginning of the season and when a visual inspection identified dirt, debris, or potential filth. Grower A was found to grow, harvest, pack and ship several other produce items along with onions. In addition to growing their own onions, Grower A sourced onions from domestic Grower AA, however, Grower A did not source any of their onions from Mexico.

3.5. FSVP inspections

FDA conducted FSVP inspections at Importers A and D and cited them for not having FSVPs for onions imported from their suppliers in Chihuahua, Mexico. Although Importer C had an incomplete FSVP, they were cited for lesser violations.

3.6. Mexico verification visits

During the last week of October 2021, COFEPRIS, in conjunction with state inspectors from Chihuahua, Mexico, carried out verification visits, which are used to verify compliance with legal and regulatory provisions, and are comparable but not necessarily equivalent to inspections in the United States, to two onion packing houses associated with the traceback. These visits mark a collaborative effort between the relevant authorities in the US and Mexico to determine potential routes of contamination and prevent future outbreaks.

Grower E (Fig. 7), which also functioned as a packing house, supplied onions from a single farm which is under the same ownership and all product that is marketed in the United States is under a single brand. The firm’s Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) plan and Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) were reviewed, and it was noted that both the packing house and farm are certified by PrimusGFS, and the firm’s traceability system was capable of tracking product from origin to destination. Noteworthy observations during the investigation include the following: lack of residual free chlorine in the water used for washing equipment and utensils, including those that come into contact with the product; a lack of deep cleaning was observed in the forced air-drying tunnels and in the grilles that protect the fans, and the wooden boxes used to transport the onion from the fields are stored in the open air. During the investigation, nine samples were collected, three of drinking water and six swabs of product contact surfaces; all results were negative for Salmonella spp.

Packing House B, which was not identified by FDA through the traceback investigation but was associated with Importer B and Growers F-J (Fig. 7), was supplied by 30 different production farms with three under the same ownership as the packing house and product was marketed in the United States under four brands. The firm’s HACCP plan and SOPs were reviewed, and the firm’s traceability system was capable of tracking product from the origin to destination. During the investigation, two samples of potable water, 28 onion samples, and seven swabs of product contact surfaces were collected; all results were negative for Salmonella spp.

Between October and November 2021, SENASICA investigators visited 20 firms and farms in the municipalities of Ascensión, Buena-ventura, Janos, Meoqui, Delicias, Camargo, Jiménez, and Rosales, located in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, and one in the state of Guanajuato, Mexico. A total of five of these firms were identified in the FDA traceback investigation and two are identified in the traceback diagram (Grower E and O in Fig. 7). Additionally, to reduce the risk of contamination in primary onion production, the governments of Mexico and Chihuahua, continued to promote voluntary food safety certification for onion suppliers of domestic and international markets to ensure quality and food safety. This included the development of a technical working group to support implementation of the voluntary Protocol of Contamination Risk Reduction Systems (SRRC), with the goals of maintaining, monitoring, and strengthening measures and procedures to reduce the risks of contamination for domestic and export consumption (Servicio Nacional de Sanidad I. y. C. A, 2021; U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2018c).

3.7. Laboratory investigation

3.7.1. FDA samples

FDA collected and analyzed 12 product samples from Distributor A, including jalapeños, yellow onions, roma tomatoes, cilantro, and Persian limes. All samples were negative for Salmonella spp. FDA collected three samples of onions and two environmental samples from Importer D. The onion samples were reportedly leftover onions from the season, from domestic and international farms, and were not intended for distribution. One environmental sample taken from a bagging machine that had reportedly been in storage and not used for two years yielded Salmonella Sandiego, while the rest were negative (Table 1). FDA collected four environmental samples from Grower AA, one of which, a sediment sample taken from the area of a well, yielded Salmonella Newport, Anatum, and Javiana, while the rest were negative. FDA increased surveillance sampling of onions from the state of Chihuahua, Mexico at the border, but since the harvest season was winding down, no samples were collected.

Table 1.

Summary of positive laboratory results from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Kansas Department of Agriculture (KDA) product and environmental samples collected in 2021 during the outbreak investigation of Salmonella Oranienburg infections.

| Sample Collected by | Date Collected | Sample Description | Sample Location | Salmonella serovar |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDA | 10/7/2021 | Swabs (Bagging machine that was in storage in the packing shed) | Importer D | Salmonella Sandiego |

| FDA | 10/15/2021 | Soil sediment | Grower AA | Salmonella Newport, Anatum, Javiana |

| KDA | 8/2021 | Condiment sample of lime and cilantro that reportedly previously contained onions, but none were left to be sampled. | POS A | Salmonella Oranienburg |

3.7.2. Other state samples

Investigators from the Illinois Department of Public Health, Tennessee Department of Health, New York State Department of Health, KDHE (from POS other than POS A), and the Maryland Department of Health collected samples of onions and other produce from various retail or restaurant locations, which did not yield Salmonella spp.

3.7.3. Mexico samples

In late October 2021, COFEPRIS investigators collected 18 samples of water and product contact surfaces from two packing houses located in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, as previously described. All samples were reported negative for Salmonella spp. Likewise, from November 2021 to January 2022, SENASICA investigators collected 73 samples including onions, water, and product contact surfaces from 15 farms and firms throughout the state of Chihuahua, Mexico. The samples did not yield Salmonella spp.

3.7.4. WGS results

Analysis by FDA indicated that the Salmonella Javiana isolate recovered from the sediment from Grower AA, was highly genetically related (1 SNP) to a 2018 clinical isolate; available information was reviewed, and raw onions were not reported by the ill person associated with this clinical isolate. Additionally, a 2021 clinical isolate was 25 SNPs from the isolate, but no exposure information for this ill person was available. Another 2021 clinical isolate was noted to be 8 SNPs different from the Salmonella Sandiego isolates recovered from the environmental swab sample collected from the bagging machine that was in storage in the packing shed of Importer D; however, no exposure information from the ill person was available. Mexican government counterparts indicated none of the sequences in their historical genomic database showed a clonal relationship with the sequences of this outbreak.

3.8. Public health actions and communications

On October 20, 2021, Distributor AA issued a voluntary recall of red, yellow, and white whole, fresh onions imported from the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, between July 1, 2021, and August 31, 2021. On October 22, 2021, Importer D recalled red, yellow, and white whole, fresh onions imported from the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, with shipping dates from July 1, 2021, through August 25, 2021. Although the illnesses ranged from May 31, 2021, to January 1, 2022, both October 2021 recalls focused on onions that were imported in the months of July and August because most of the implicated firms only imported during this peak period. Downstream recalls were initiated by companies that sold recalled onions or products containing the recalled onions and FDA published a list of establishments that received recalled product (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2021c). Products were distributed nationwide to wholesalers, foodservice customers, and retail under numerous brands. FDA, CDC, and state partners issued regular public communications to provide updates on the investigation and resulting recalls in an effort to protect public health (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021; U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2021c). FDA also shared recommendations for restaurants, retailers, consumers, suppliers, and distributors on how to handle recalled onions and how to proceed with cleaning and sanitizing after their removal.

4. Discussion

This 2021 Salmonella Oranienburg outbreak linked to onions from the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, was slightly smaller in scope than a previous 2020 domestic onion-associated outbreak, having caused 1040 reported illnesses. While The 2021 outbreak investigation did identify the farms where the implicated onions were grown, FDA was unable to conduct on-farm investigations in Mexico. Therefore, investigators’ ability to determine the contributing factors that led to the contamination of the onions, and thus caused the outbreak, was limited.

The traceback conducted for this outbreak investigation had several noteworthy challenges and limitations, similar to those encountered in past traceback investigations focused on produce (Irvin et al., 2021; Whitney et al., 2021). Specifically, inadequate, and inconsistent record keeping at several POS as well as comingling or supplementing supplies without proper documentation, were encountered by investigators, as also described by Whitney et al. (2021) and Irvin et al. (2021) (Irvin et al., 2021; Whitney et al., 2021). Additionally, there were some unique challenges to this traceback investigation. The epidemiologic investigation identified a signal for ill people exposed to dishes with a number of the same ingredients at restaurants, which necessitated investigators to include several commodities in the traceback before a likely vehicle could be determined. As a result, conducting traceback investigations for five different potential vehicles made coordination of activities more difficult which required significant resources. Several POS employed “jobbers” (a person transporting produce from a market to a POS, often without formal records associated with these deliveries), used local wholesale markets as suppliers, and supplemented product from other stores (retail or other POS) without documentation when supplies ran low. All of which increased the difficulty in determining exactly what items were purchased and served by each POS. To initiate traceback, FDA had to designate a specific timeframe of interest at each point of the supply chain for record collection, which typically broadens the number of records requested, increases the time it takes to analyze those records, or results in the inability to fully trace products of interest, instead of narrowing the focus to specific implicated shipments or lot codes of interest. Compounding these issues, there were several second- and third-line distributors that investigators had to contact for records before being able to identify importers and growers of interest for all five traced products. The added time required to identify these importers and growers, the winding down of the growing season for onions in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, and several domestic facilities used by importers having been cleaned and shut down for the growing season further exacerbated traceback challenges. Lack of current operations at these firms meant investigators were unable to observe receiving, handling, and other practices undertaken at all importers and farms. Furthermore, since the Chihuahua growing season was concluding, this rapidly decreased the window of opportunity for investigations and sample collection at packing houses and farms in Mexico.

Once importers were identified, it was determined that the farms of interest were in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, a region that sourced onions that were supplied to all subclusters of the traceback. However, many of the farms had similar names, some importers supplied partial farm names, and both growers and importers provided conflicting GPS information, which caused confusion about how many growers were separate entities and where exactly these growers were located. As a result, it was not possible to determine if some were separate growers, the same, or affiliated growers exporting under slightly different names.

Finally, due to the U.S. Department of State’s travel restrictions for government employees because of safety and security concerns, and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, FDA was unable to visit the growers and packing houses of interest in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico. However, Mexican government counterparts SENASICA and COFEPRIS, regularly collaborate with FDA through the FDA-SENASICA-COFEPRIS Food Safety Partnership (FSP). Those Mexican agencies shared information from their investigations which included visiting 20 firms, farms, or packing houses of interest, visiting five of the eight that were identified in the FDA traceback. By the time enhanced import screening was implemented for onions and cilantro (which was still a potential vehicle being investigated at the time) sourced from Mexico, the growing season for onions had already concluded, making the availability of imported product for sampling increasingly difficult. Ultimately, due to travel restrictions, inconsistent record keeping at several POS, and the large number of distributors involved in the traceback investigation, it was difficult to draw definitive conclusions on the source of contamination that led to the outbreak.

Possible contributing factors to potential contamination pathways include a series of 2021 adverse weather events. A few examples include extended drought, long lasting dust storms, or flood events (Carlowicz, 2021). In 2021, a long-term drought had affected two-thirds of Mexico with forecasts warning of continued high temperatures, crop damage and water supply shortages on the horizon (Garrison, 2021). Dry and windy conditions were probably a contributing factor to gusty springtime winds turning skies yellow in mid-March 2021 across northern Mexico. Sustained winds of 35–45 miles (55–70 km) per hour with gusts to 65 (100 km) lofted abundant streams of dust (Earth Observatory, 2021) for nearly 8 h from the Chihuahua Desert, while several identified dust source areas within Chihuahua, Mexico, including Laguna Los Moscos, the Nuevo Casas Grandes River, and the Laguna Palomas. The soil (and resultant dust) is home to many pathogens capable of causing disease in humans and surviving within the soil for extended periods of time. Some of the factors that may affect the incidence of such organisms include land management practices and climate change (Jeffery & Van der Putten, 2011). Movement of dusts and bio-aerosols containing microorganisms into adjacent plant crop-growing environments represent a possible transfer route; however, this mechanism of transfer is not well characterized (Glaize et al., 2020; Hutchison et al., 2008; Theofel et al., 2020). While it is unknown whether there were any animal operations alongside the produce industry in this region of Mexico, it has been suggested in the past that fugitive dust, formed during droughts, may contaminate produce fields through transfer by wind (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2021a). Also, during August 2021, a storm delivered significant rainfall in various areas of Chihuahua, Mexico, resulting in devastating flooding within the state (Davies, 2021b). Another period of intense rainfall occurred mid-August 2021 which also led to severe flooding, as well as landslides, in Chihuahua, Mexico (Davies, 2021a). Flooding events present a potentially hazardous public health risk. As an example, produce crops such as onions may become submerged in flood water which may have been exposed to sewage, chemicals, heavy metals, pathogenic microorganisms, or other contaminants. Even if the onion crop is not completely submerged and appears unaffected after flood waters recede, there may still be microbial contamination of the edible portion of the crop from contact with potentially contaminated flood waters or contaminated soils (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2011). It is unknown what the condition of the growing fields were during or after these adverse weather events.

During the investigation, on-farm inspections took place at domestic farms that both grew domestic onions, but also imported onions from the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, to supplement their own production. Several possible pathways of contamination were discovered, but none were determined to be the cause of contamination. At the domestic farms inspected, the imported onions may have been stored in bulk bins with visual inspection as the determining factor of whether a bin should be cleaned, and no objective method for determining whether the bin was contaminated with a pathogen. Trucks transporting onions were noted to be open air and bagging equipment may not be cleaned between different lots or types of onions, which could lend to contamination. At both the distribution and POS level, it was noted that distributors would not always sanitize processing equipment between different commodities, different shipments, or lots and POS would not always clean and sanitize surfaces and equipment between different produce items.

The on-farm investigation for the 2020 outbreak of Salmonella Newport linked to onions grown in Bakersfield, California, was not conducted during harvesting, storage, and packing activities (McCormic et al., 2022). However, visual observations of the implicated fields suggested there were several possibilities for contamination, including the sources of irrigation water, sheep grazing on adjacent land, and signs of animal intrusion, including scat and large flocks of birds, which have been shown to spread contamination (Topalcengiz et al., 2020).

Likewise, during investigations carried out by COFEPRIS at Grower E and Packing House B, some possible routes of contamination were observed but none of them could be considered the definitive cause of contamination. The packing house conditions and a review of procedures, indicated opportunities for spread of bacterial pathogens such as Salmonella spp., including signs of animal and pest intrusion and food contact surfaces which had been improperly cleaned or maintained. The use of water without residual free chlorine content that would guarantee its disinfection, storing wooden bins used for transporting onions from the fields to the packing plant in the open air, and the intermittent implementation of cleaning procedures, were factors that could have contributed to product contamination. Further follow up visits to the farms and firms of interest by Mexican authorities could provide a better understanding of potential sources and pathways of contamination.

The Binational Protocol was used including successful implementation of newer processes and Mexican governmental counterpart engagement (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2018c; 2021b). The FDA, COFEPRIS, and SENASICA exchanged regulatory information, conducted inspections, and determined the need for produce safety initiatives and outreach. Information was exchanged through use of the Binational Protocol and Confidentiality Commitments using the processes established under the FSP Outbreak workgroup. The FSP broadened and strengthened the scope of the agencies’ existing partnership to include the safety of all human food regulated by the FDA. Additionally, the FSP allowed the agencies to leverage food safety programs at SENASICA and COFEPRIS to work with local industry and further enhanced the collaborations of U.S. and Mexico with other key partners.

For the 2021 outbreak, while on-farm investigations by FDA investigators in Mexico were not possible, targeted investigations into similar situations when the opportunity arises are imperative to gain a better understanding of the microbial risks associated with the growing, harvesting, storage, and packing of bulb onions. FDA continues to collaborate with Mexican government counterparts on food safety strategies through the established FSP. SENASICA officials held a meeting with representatives from the government of Chihuahua and local onion producers, packagers, and exporters, where SENASICA, COFEPRIS, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Government of Chihuahua, and industry groups, agreed to the implementation of a jointly operated work program to minimize the impact of future outbreaks. The program included training and promoting the application of the voluntary program of SRRCs to certify the vegetable primary production and packaging units. As a result, SENASICA will maintain a list of companies certified in SRRCs that implement Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) that are eligible to export onions since they will follow the measures and procedures provided for in the Mexican regulations, which will be shared with FDA.

Educational and outreach activities to Mexico targeting onion growers are important to help promote compliance with the Produce Safety Rule (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2020c). It is also important to conduct similar activities with importers of onions to the United States to ensure compliance with FSVP. In the meantime, FDA could consider increased import sampling of all bulb onions from Chihuahua, Mexico, at United States ports of entry for the duration of time that onions are exported. Since the prevalence of onion contamination in the market is not well established, a surveillance sampling assignment could help better understand the scope of contamination in onions destined for the fresh market. Lastly, it is important to help promote research on contamination pathways for onion production to identify practices that can help support prevention efforts across the supply chain. For example, past research has suggested that conventional curing practices can be an effective mitigation strategy for dry bulb onions produced with water of poor microbiological quality (Emch & Waite-Cusic, 2016). However, the study results may not be applied across the spectrum of onion growing conditions given the significant differences in soil composition across different growing regions, and the different curing practices. Additional research is necessary to help determine the risks farm inputs pose to growing, harvest, storing, and packing onions.

5. Conclusions

Epidemiologic and traceback evidence identified bulb onions as the vehicle for this outbreak, which resulted in 1040 illnesses. Traceback confirmed a link between onions grown in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, and multiple POS where ill people purchased or were exposed to onions. While the outbreak strain was not identified in samples collected by FDA, a condiment sample that previously contained onions collected by state partners yielded the outbreak strain of Salmonella Oranienburg. This incident is of significant interest because it supports the need for ongoing international collaboration between the U.S. and Mexican authorities, as facilitated through the FSP. It is critical that the two countries collaborate whenever there is an opportunity for on-farm investigations to determine the source and extent of environmental contamination. Lastly, it is important to identify improved practices across the supply chain that could prevent environmental contamination of onions.

Acknowledgements

The response efforts for this outbreak included numerous public health officials at local and state health and regulatory departments and public health laboratories in the U.S., who serve as the backbone of any multi-state foodborne illness outbreak investigation. We also appreciate the assistance provided by FDA Emergency Response Coordinators who coordinated the response between FDA and state partners.

Declaration of competing interest

Reference to any commercial materials, equipment, or process does not, in any way, constitute approval, endorsement, or recommendation by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration. All views and opinions expressed throughout this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent views or official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Comisión Federal para la Protección contra Riesgos Sanitarios.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Public Health Service, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Marvin R. Mitchell: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Margaret Kirchner: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Ben Schneider: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation. Monica McClure: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Investigation. Karen P. Neil: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation. Asma Madad: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Temesgen Jemaneh: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Mary Tijerina: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Kurt Nolte: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Allison Wellman: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Daniel Neises: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Arthur Pightling: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Angela Swinford: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Alyssa Piontkowski: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Rosemary Sexton: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Crystal McKenna: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Jason Cornell: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Ana Lilia Sandoval: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Hua Wang: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Rebecca L. Bell: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Christan Stager: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Mayrén Cristina Zamora Nava: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. José Luis Lara de la Cruz: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Luis Ignacio Sánchez Córdova: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Pablo Regalado Gálvan: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Javier Arias Ortiz: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Sally Flowers: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Amber Grisamore: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Laura Gieraltowski: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Michael Bazaco: Writing – review & editing. Stelios Viazis: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Project administration, Conceptualization.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Andrews HW, Wang H, Jacobson A, Beilei G, Zhang G, & Hammack T (2021). Bacteriological analytical manual (BAM) chapter 5: Salmonella. Retrieved December 27 from https://www.fda.gov/food/laboratory-methods-food/bam-chapter-5-salmonella.

- Behravesh CB, Blaney D, Medus C, Bidol SA, Phan Q, Soliva S, Daly ER, Smith K, Miller B, Taylor T Jr., Nguyen T, Perry C, Hill TA, Fogg N, Kleiza A, Moorhead D, Al-Khaldi S, Braden C, & Lynch MF (2012). Multistate outbreak of Salmonella serotype typhimurium infections associated with consumption of restaurant tomatoes, USA, 2006: Hypothesis generation through case exposures in multiple restaurant clusters. Epidemiology and Infection, 140(11), 2053–2061. 10.1017/s0950268811002895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DD, Higgins SE, Moore RW, Beltran R, Caldwell DJ, Byrd JA, & Hargis BM (2003). Effects of lime on Salmonella enteritidis survival in vitro. The Journal of Applied Poultry Research, 12(1), 65–68. 10.1093/japr/12.1.65 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett SD, Littrell KW, Hill TA, Mahovic M, & Behravesh CB (2015). Multistate foodborne disease outbreaks associated with raw tomatoes, United States, 1990–2010: A recurring public health problem. Epidemiology and Infection, 143(7), 1352–1359. 10.1017/s0950268814002167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beshearse E, Bruce BB, Nane GF, Cooke RM, Aspinall W, Hald T, Crim SM, Griffin PM, Fullerton KE, & Collier SA (2021). Attribution of illnesses transmitted by food and water to comprehensive transmission pathways using structured expert judgment, United States. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 27(1), 182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besser JM, Carleton HA, Trees E, Stroika SG, Hise K, Wise M, & Gerner-Smidt P (2019). Interpretation of whole-genome sequencing for enteric disease surveillance and outbreak investigation. Foodbourne Pathogens & Disease, 16(7), 504–512. 10.1089/fpd.2019.2650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlowicz M (2021). Long-lasting dust storm from Chihuahua. Retrieved March 17 from https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/148057/long-lasting-dust-storm-from-chihuahua.

- Council to Improve Foodborne Outbreak Response. (2020). Guidelines for foodborne disease outbreak response. Retrieved July 29 from https://cifor.us/downloads/clearinghouse/CIFOR-Guidelines-Complete-third-Ed.-FINAL.pdf.

- Crowe SJ, Green A, Hernandez K, Peralta V, Bottichio L, Defibaugh-Chavez S, Douris A, Gieraltowski L, Hise K, La-Pham K, Neil KP, Simmons M, Tillman G, Tolar B, Wagner D, Wasilenko J, Holt K, Trees E, & Wise ME (2017). Utility of combining whole genome sequencing with traditional investigational methods to solve foodborne outbreaks of Salmonella infections associated with chicken: A New tool for tackling this challenging food vehicle. Journal of Food Protection, 80(4), 654–660. 10.4315/0362-028x.Jfp-16-364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danyluk MD (2019). Survival of Salmonella on lemon and lime slices and subsequent transfer to beverages. Food Protection Trends, 39(2), 154–161. [Google Scholar]

- Davies R (2021a). Mexico – deadly flash floods in Chihuahua after 60mm of rain in 3 hours. Retrieved March 17 from https://floodlist.com/america/mexico-floods-chihuahua-august-2021.

- Davies R (2021b). Mexico – homes destroyed by flash floods in coahuila and durango. Retrieved December 27 from https://floodlist.com/america/mexico-floods-coahuila-durango-august-2021.

- Davis S, Pettengill JB, Luo Y, Payne J, Shpuntoff A, Rand H, & Strain E (2015). CFSAN SNP pipeline: An automated method for constructing SNP matrices from next-generation sequence data. PeerJ Comput. Sci, 1. 10.7717/peerjcs.20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dyda A, Nguyen P-Y, Chughtai A, & MacIntyre CR (2020). Changing epidemiology of Salmonella outbreaks associated with cucumbers and other fruits and vegetables. Global Biosecurity, 2(1). [Google Scholar]

- Earth Observatory. (2021). Long-lasting dust storm from Chihuahua. Retrieved December 28 from https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/148057/long-lasting-dust-storm-from-chihuahua.

- Emch AW, & Waite-Cusic JG (2016). Conventional curing practices reduce generic Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. on dry bulb onions produced with contaminated irrigation water. Food Microbiology, 53(Pt B), 41–47. 10.1016/j.fm.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register. (2021). Onions grown in south Texas and imported onions; termination of marketing order 959 and change in import requirements. Retrieved December 15 from https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/08/05/2021-16495/onions-grown-in-south-texas-and-imported-onions-termination-of-marketing-order-959-and-change-in.

- Garrison C (2021). Mexico water supply buckles on worsening drought, putting crops at risk. Retrieved March 17 from https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/mexico-water-supply-buckles-worsening-drought-putting-crops-risk-2021-07-02/#:~:text=About%2070%25%20of%20Mexico%20is5%25%20each%20year%20since%202012.

- Glaize A, Gutierrez-Rodriguez E, Hanning I, Díaz-Sánchez S, Gunter C, van Vliet AHM, Watson W, & Thakur S (2020). Transmission of antimicrobial resistant non-O157 Escherichia coli at the interface of animal-fresh produce in sustainable farming environments. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 319, 108472. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2019.108472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison ML, Avery SM, & Monaghan JM (2008). The air-borne distribution of zoonotic agents from livestock waste spreading and microbiological risk to fresh produce from contaminated irrigation sources. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 105 (3), 848–857. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03811.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hygiena. (2021). BAX® system real-time PCR assay Salmonella. Retrieved February 27 from https://www.hygiena.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/BAX-Q7-Assay-Kit-Insert-Salmonella-RT-English.pdf.

- Irvin K, Viazis S, Fields A, Seelman S, Blickenstaff K, Gee E, Wise ME, Marshall KE, Gieraltowski L, & Harris S (2021). An overview of traceback investigations and three case studies of recent outbreaks of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections linked to romaine lettuce. Journal of Food Protection, 84(8), 1340–1356. 10.4315/jfp-21-112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery S, & Van der Putten WH (2011). Soil borne human diseases. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 49(10.2788), 37199. [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Zhang G, Gerner-Smidt P, Tauxe RV, & Doyle MP (2010). Survival and growth of Salmonella in salsa and related ingredients. Journal of Food Protection, 73 (3), 434–444. 10.4315/0362-028x-73.3.434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormic ZD, Patel K, Higa J, Bancroft J, Donovan D, Edwards L, Cheng J, Adcock B, Bond C, Pereira E, Doyle M, Wise ME, & Gieraltowski L (2022). Bi-national outbreak of Salmonella Newport infections linked to onions: The United States experience. Epidemiology and Infection, 150, e199. 10.1017/s0950268822001571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Onion Association. (2017). U.S. Production And Availability. Retrieved December 15 from https://www.onions-usa.org/all-about-onions/retail/us-production-and-availability/.

- North Bay Parry Sound District Health Unit. (2009). Investigative summary of the Escherichia coli outbreak associated with A restaurant in north Bay. Ontario: October to November 2008. https://www.myhealthunit.ca/en/community-data-reports/resources/Reports-Statistics-Geographic-Profiles/Environmental-health/InvestigativeSummaryoftheE.coliOutbreak-June-2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, Jones JL, & Griffin PM (2011). Foodborne illness acquired in the United States-major pathogens. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 17(1), 7–15. <Go to ISI>://000285904600002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servicio Nacional de Sanidad, I. y. C. A. (2021). Systems for contamination risk reduction. Retrieved November 2 from https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/718375/Systems_for_Contamination_Risk_Reduction.pdf.

- Theofel CG, Williams TR, Gutierrez E, Davidson GR, Jay-Russell M, & Harris LJ (2020). Microorganisms move a short distance into an almond orchard from an adjacent upwind poultry operation. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 86(15). 10.1128/aem.00573-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolar B, Joseph LA, Schroeder MN, Stroika S, Ribot EM, Hise KB, & Gerner-Smidt P (2019). An overview of PulseNet USA databases. Foodbourne Pathogens & Disease, 16(7), 457–462. 10.1089/fpd.2019.2637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topalcengiz Z, Spanninger PM, Jeamsripong S, Persad AK, Buchanan RL, Saha J, Le JJ, Jay-Russell MT, Kniel KE, & Danyluk MD (2020). Survival of Salmonella in various wild animal feces that may contaminate produce. Journal of Food Protection, 83(4), 651–660. 10.4315/0362-028x.Jfp-19-302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016a). Retrieved July 30, 2021 from PulseNet Methods and Protocols https://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/pathogens/protocols.html.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Salmonella outbreak linked to onions. Retrieved December 14 from https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/oranienburg-09-21/index.html.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control Prevention. (2016b). Multistate outbreak of listeriosis linked to frozen vegetables. Retrieved December 27 from https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/frozen-vegetables-05-16/index.html#:~:text=Whole%20genome%20sequencing%20showed%20thatisolate%20from%20an%20ill%20person.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2011). Guidance for industry: Evaluating the safety of flood-affected food crops for human consumption. Retrieved November 21 from https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-evaluating-safety-flood-affected-food-crops-human-consumption#ftn2.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2012). Gills onions expands voluntary recall of diced and slivered red and yellow onions, and diced onion and celery mix because of possible health risk. Retrieved December 14 from https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170406110507/https://www.fda.gov/Safety/Recalls/ArchiveRecalls/2012/ucm313399.htm.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2018a). Enforcement report: Event ID 81281, McCain foods USA. Retrieved December 14 from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/ires/index.cfm?Event=81281.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2018b). Twelve haggen stores voluntarily recall select deli products in cooperation with taylor farms’ onion recall due to possible Salmonella contamination. Retrieved December 14 from https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20180907140541/https://www.fda.gov/Safety/Recalls/ucm601753.htm.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2018c). U.S. FDA-Mexico produce safety partnership: A dynamic partnership in action. Retrieved May 6 from https://www.fda.gov/media/113925/download.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2020a). Factors potentially contributing to the contamination of red onions implicated in the summer 2020 outbreak of Salmonella Newport. Retrieved December 14 from https://www.fda.gov/food/foodborne-pathogens/factors-potentially-contributing-contamination-red-onions-implicated-summer-2020-outbreak-salmonella.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2020b). FSMA final rule on Foreign supplier verification programs (FSVP) for importers of food for humans and animals. Retrieved May 22 from https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-modernization-act-fsma/fsma-final-rule-foreign-supplier-verification-programs-fsvp-importers-food-humans-and-animals.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2020c). FSMA final rule on produce safety: Standards for the growing, harvesting, packing, and holding of produce for human consumption. Retrieved May 22 from https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-modernization-act-fsma/fsma-final-rule-produce-safety.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2021a). Factors potentially contributing to the contamination of peaches implicated in the summer 2020 outbreak of Salmonella enteritidis. Retrieved October 20 from https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/factors-potentially-contributing-contamination-peaches-implicated-summer-2020-outbreak-salmonella.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2021b). FDA-SENASICA-Cofepris food safety partnership. Retrieved February 1 from https://www.fda.gov/food/international-cooperation-food-safety/fda-senasica-cofepris-food-safety-partnership.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2021c). Outbreak investigation of Salmonella Oranienburg: Whole, fresh onions (october 2021). Retrieved December 14 from https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/outbreak-investigation-salmonella-oranienburg-whole-fresh-onions-october-2021.

- U.S. National Agricultural Statistic Service. (2023). National statistics for onions. Retrieved May 2 from https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_Subject/result.php?F68BE147-6498-37BC-A9A5-9D7EFB926592§or=CROPS&group=VEGETABLES&comm=ONIONS.

- White AE, Smith KE, Booth H, Medus C, Tauxe RV, Gieraltowski L, & Scallan Walter E (2021). Hypothesis generation during foodborne-illness outbreak investigations. American Journal of Epidemiology, 190(10), 2188–2197. 10.1093/aje/kwab118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney BM, Mc CM, Hassan R, Pomeroy M, Seelman SL, Singleton LN, Blessington T, Hardy C, Blankenship J, Pereira E, Davidson CN, Luo Y, Pettengill J, Curry P, Mc CT, Gieraltowski L, Schwensohn C, Basler C, Fritz K, & Viazis S (2021). A series of papaya-associated Salmonella illness outbreak investigations in 2017 and 2019: A focus on traceback, laboratory, and collaborative efforts. Journal of Food Protection, 84(11), 2002–2019. 10.4315/jfp-21-082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XX, Lin FJ, Li H, Li HB, Wu DT, Geng F, Ma W, Wang Y, Miao BH, & Gan RY (2021). Recent advances in bioactive compounds, health functions, and safety concerns of onion (Allium cepa L.). Frontiers in Nutrition, 8, 669805. 10.3389/fnut.2021.669805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.