Abstract

Background

Accurate differentiation between malignant and benign pulmonary nodules, especially those measuring 5–10 mm in diameter, continues to pose a significant diagnostic challenge. This study introduces a novel, precise approach by integrating circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) methylation patterns, protein profiling, and computed tomography (CT) imaging features to enhance the classification of pulmonary nodules.

Methods

Blood samples were collected from 419 participants diagnosed with pulmonary nodules ranging from 5 to 30 mm in size, before any disease-altering procedures such as treatment or surgical intervention. High-throughput bisulfite sequencing was used to conduct DNA methylation profiling, while protein profiling was performed utilizing the Olink proximity extension assay. The dataset was divided into a training set and an independent test set. The training set included 162 matched cases of benign and malignant nodules, balanced for sex and age. In contrast, the test set consisted of 46 benign and 49 malignant nodules. By effectively integrating both molecular (DNA methylation and protein profiling) and CT imaging parameters, a sophisticated deep learning-based classifier was developed to accurately distinguish between benign and malignant pulmonary nodules.

Results

Our results demonstrate that the integrated model is both accurate and robust in distinguishing between benign and malignant pulmonary nodules. It achieved an AUC score 0.925 (sensitivity = 83.7%, specificity = 82.6%) in classifying test set. The performance of the integrated model was significantly higher than that of individual methylation (AUC = 0.799, P = 0.004), protein (AUC = 0.846, P = 0.009), and imaging models (AUC = 0.866, P = 0.01). Importantly, the integrated model achieved a higher AUC of 0.951 (sensitivity = 83.9%, specificity = 89.7%) in 5–10 mm small nodules. These results collectively confirm the accuracy and robustness of our model in detecting malignant nodules from benign ones.

Conclusions

Our study presents a promising noninvasive approach to distinguish the malignancy of pulmonary nodules using multiple molecular and imaging features, which has the potential to assist in clinical decision-making.

Trial registration: This study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov on 01/01/2020 (NCT05432128). https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05432128.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-024-05723-5.

Keywords: Pulmonary nodules classification, Cell-free DNA methylation, Protein profiling, Imaging, Integrated model

Introduction

Lung cancer (LC) is one of the most common types of cancer and a leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1]. While the early detection of lung cancer through low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) has proven effective [2], distinguishing malignant from benign nodules using LDCT alone remains challenging [3], The limited ability to accurately differentiate between benign and malignant pulmonary nodules can also result in overtreatment. Postsurgery false-positive rates for 5–10 mm nodules can exceed 50%, in contrast to nodules larger than 10 mm, which tend to have false-positive rates below 30% [4, 5]. This discrepancy suggests that small nodules are more susceptible to overtreatment. Therefore, accurately determining the benign or malignant nature of nodules, especially small ones, is of paramount importance, as it would enable early lung cancer diagnosis and minimize the risk of unnecessary treatments.

CT imaging features such as the size and morphology of nodules play a crucial role in this process, as they are closely associated with the risk of lung cancer [6]. Models with only a few radiological features can distinguish malignant nodules from benign nodules well [7]. Although these models show promising results, there is still a need to improve their diagnostic accuracy. Radiomics offers the capability to extract numerous features from nodules with high reproducibility [8], improving the accuracy of nodule characterization and providing a noninvasive and efficient approach for diagnosing lung nodules.

Liquid biopsy has been proposed as a potent noninvasive tool to enhance the diagnosis of benign and malignant lung nodules. Alterations in DNA methylation patterns within certain regions, particularly promoter CpG islands, might serve as early molecular indicators of tumor initiation [9]. The methylation of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in peripheral blood has also emerged as a promising liquid biopsy biomarker for noninvasive LC screening [10]. A recent study developed a PCR-based cfDNA methylation test for the early detection of lung cancer that well distinguishes between cancer, normal samples, and benign tumors [11]. Currently, studies utilize high-throughput sequencing technology, which has facilitated the identification of specific methylation sites on pulmonary nodules, aiding in a more accurate differentiation of lung nodules [12]. In addition to blood cfDNA methylation markers, protein biomarkers have become important biochemical indicators for early lung cancer screening. Traditional blood-based protein biomarkers, such as cancer antigen 125 (CA 125), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), are frequently employed to monitor lung cancer patients [13]. Nevertheless, these proteins are also present in the serum of individuals without cancer, limiting their effectiveness for diagnosing early-stage lung cancer [14]. The recent advent of blood proteomics high-throughput assay platforms, such as the proximity extension assay (PEA), allows the simultaneous analysis of thousands of target proteins using a few microliters of blood [15], which holds promise for differentiating between benign and malignant lung nodules.

Recent efforts have shown that combining features from various dimensions can more accurately distinguish between benign and malignant pulmonary nodules. The PulmoSeek Plus model, which integrates clinical, imaging, and cell-free DNA methylation biomarkers, has shown promise in aiding the early diagnosis of pulmonary nodules, and it has a better discriminative effect on small nodules [16]. In another study, a malignancy risk prediction model named PSR was developed: Incorporating nine imaging and protein biomarkers, it outperformed the clinical risk prediction model [17]. While the integration of various features may enhance model performance, no study has combined methylation, protein, and imaging features for accurate differentiation between benign and malignant pulmonary nodules. Furthermore, despite the extensive research in this field, there are no widely accepted molecular and imaging assays for the early detection of lung cancer.

In this study, we developed a machine-learning model for discriminating between benign and malignant pulmonary nodules by integrating blood cfDNA methylation, proteomic data, and CT radiomic features. This model enables the accurate determination of the risk of lung cancer associated with pulmonary nodules identified by CT scans.

Methods

Patients and sample collection

Participants with pulmonary nodules were recruited from three hospitals in China, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, West China Hospital, and Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital, between January 2020 and June 2022. Blood samples were collected before any disease-related treatment or resection. This study was approved by the ethics committees of all the participating centers. Adult patients aged 18 years or older were included in this study. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy or lactation and a prior history of cancer, pulmonary vasculitis, or pulmonary tuberculosis. In accordance with the eighth TNM classification of lung cancer, early-stage tumors, which include stages 0 and 1, typically have sizes of 30 mm or less. Clinical management is advised for nodules measuring 5 mm or larger. For these reasons, we collected lung nodules ranging in size from 5 to 30 mm. All malignant and a subset of benign nodules were confirmed through definitive pathological diagnostic results. For benign nodules lacking surgical confirmation, our expert team, comprising two clinical specialists and one senior imaging specialist, conducted evaluations. These benign cases underwent a follow-up period of at least 12 months after the initial diagnosis of pulmonary nodules. The study ultimately enrolled a total of 419 patients to develop and test models for assessing the malignancy risk of pulmonary nodules.

Blood sample collection and plasma isolation

Blood samples from patients with pulmonary nodules were collected from multiple centers. Ten milliliters of blood were drawn from each patient into a STRECK vacutainer and stored at 4 °C until the end of the business day. The samples were then processed by centrifugation, first at 1600 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The upper plasma layer was carefully aspirated, and a second centrifugation was performed at 1600 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The plasma was then aliquoted into barcoded cryovials for long-term storage at − 80 °C or lower for subsequent cfDNA methylation and PEA protein analyses.

The processing of plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA)

DNA methylation analysis was done with a standard mTitan® pipeline (Singlera Genomics Co., Ltd.). Briefly, the cfDNA was bisulfite-converted using the Methylcode Bisulfite Conversion Kit (ThermoFisher, MECOV50) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The bisulfite-converted DNA was dephosphorylated and ligated to a universal adapter with a unique molecular identifier (UMI). Following a second strand synthesis and purification, the DNA underwent a semitargeted amplification. Following purification, a second PCR added sample-specific barcodes and full-length sequencing adapters. The libraries were then quantified using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit for Illumina (KK4844) and were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 500 in paired-end 300 bp mode, with the requirement of a minimum of 4 million reads per sample.

Paired-end reads from the potential same fragment were merged by using software pear (Version 0.9.6) to select high-quality original cfDNA fragments. Adapters at the end of fragments were trimmed by using trim galore (Version 0.4.0), and then unique molecular identifiers (UMI) were extracted from each read. Then, the preprocessed reads were mapped against the CT and GA-converted hg19 reference sequences. After sequence alignment, the unique methylation haplotypes in 1656 regions were deduplicated using their UMI information.

A methylation malignancy score (MMS) was calculated for each region using a three-step process (see the pipeline in Supplementary Fig. 1). First, each read within the region was transformed into a vector with a length equal to the number of CpG sites. Methylated sites were scored as 2, nonmethylated sites as 1, and uncovered sites as 0. These encoded reads were then used as the input to train a transformer model, which was an attentive deep-learning model known for its ability to capture complex patterns. The model generated a continuous score ranging from 0 to 1, where a higher score indicated a greater likelihood that the read originated from a malignant nodule. Additionally, all reads within each region were categorized into certain score intervals. The number of reads and their proportions in each interval were then calculated as new features. Finally, a logistic regression model was trained to yield the MMS score, which assessed the malignancy risk of the region. These region scores were then used as methylation features for analysis.

Measurement of plasma protein levels

Oncology-related proteins were measured in 50 µL of plasma using the Proseek Oncology Proximity Extension Panel (available at 'https://olink.com/') based on PEA technology. In brief, antibodies are equipped with a set of probes, where each probe has complementary bases at their ends. When the target protein is captured by a pair of probes, the complementary bases come into close proximity and form a double-stranded template. This template is then subjected to quantitative detection using qPCR or NGS, allowing for the determination of protein abundance. All samples were randomly assigned to different plates, and the counts obtained were subjected to quality control and normalization using internal and external controls. Finally, the data were converted into an arbitrary Normalized Protein eXpression (NPX) unit on a log2 scale, where a higher NPX value means a higher protein level.

Image segmentation and feature extraction

After the CT images were acquired in digital imaging and communications in medicine (DICOM) format, two experienced radiologists specializing in thoracic tumor diagnosis completed lesion segmentation using MITK software (available at https://www.mitk.org/). To ensure accuracy, the region of interest (ROI) was manually delineated layer by layer on the lung window image until the entire nodule was included. In cases where multiple nodules were present, only the most typical nodule supporting the sample phenotype was retained for further analysis. To extract radiomic features, a Python package called ‘PyRadiomics’ (Version 3.0.1) [18] was used. This package allows for the extraction of many quantitative features from medical images, such as texture, shape, and intensity. These features were then used alone or in conjunction with the methylation and protein data to construct a predictive model for lung cancer risk.

Statistical analysis

For clinical and pathological features, continuous data are reported as the mean ± standard deviation. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to examine whether markers were differentially expressed between malignant and benign pulmonary nodules. A Benjamini‒Hochberg–adjusted p value less than 0.05 was defined as statistically significant. In the measurements of correlations of clinical features between different groups, Fisher’s exact test was performed on categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. McNemar’s test was utilized to compare the accuracy of the two models, and DeLong’s test was used to compare the AUCs of the two models. The classification of models as positive or negative was determined by the cutoff value, which corresponded to a specificity of 80% in the training set.

Model development

We utilized a two-level learning process similar to the stacking model [19]. First, three base neural network (NN) scoring models were trained on the methylation, protein and imaging features, respectively (Fig. 1). Each basic neural network model started with an input layer that matched the input feature dimensions, followed by three hidden layers with 32, 16, and 8 neurons. It ended with an output layer containing 2 neurons. A batch normalization layer was added after the input layer, and the output layer used a sigmoid activation function, while the other layers used ReLU activation. We applied the Adam optimizer [20] and cross-entropy loss function for model training and Keras (version 2.4.3) [21] for building these models. Each base NN model underwent training using a fivefold cross-validation method. In each fold, the model was trained on 4/5 of the training samples while validating on the remaining 1/5. The predictions from each base model using the cross-validation data served as inputs for the second-level model. When making predictions on samples in the test set, we averaged the scores assigned by the five cross-validated base models. A final logistic regression model was trained on the outputs of the base models. The accuracy and robustness of the model were then evaluated on the test set.

Fig. 1.

Workflow of this study

Results

Characteristics of participants and samples group

The 419 plasma samples were first split into a training set and an independent test set. The training set included 162 benign nodules (BNs) and 162 malignant nodules (MNs), matched for sex and age. Of these, 100 BNs and 143 MNs had complete radiomics features extracted for imaging-related analysis. The test set comprised 46 BNs and 49 MNs, contained complete radiomics features for all cases (Fig. 1, Table 1). The percentages of MNs were 50% and 51.6% in the overall training set and the test set, respectively, and 58.8% in the subset of the training set with radiomics data. These samples were all primarily early-stage cancer (stage 0–I) in both the training and test sets. In the training set, the size of the nodules in the benign group was 7.8 ± 3.0 mm, which was statistically smaller (P < 0.0001) than that of the malignant group (11.9 ± 6.2 mm). Most malignant nodules in both the training and test sets were in the 5–10 mm range, comprising 58% and 63.3%, respectively. Detailed demographic and clinical information and nodule characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants

| Training set | Test set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | Cancer | Benign | Cancer | ||

| #Total, n (with radiomics)* | 162(100) | 162(143) | 46(46) | 49(49) | |

| Sex, n (%) | Male | 52(32.1%) | 52(32.1%) | 16(34.8%) | 18(36.7%) |

| Female | 110(67.9%) | 110(67.9%) | 30(65.2%) | 31(63.3%) | |

| Age, Mean ± SD | – | 54.3 ± 11.8 | 54.7 ± 12.1 | 48.5 ± 12.5 | 59.5 ± 14.4 |

| Diameter, Mean ± SD | – | 7.8 ± 3.0 | 11.9 ± 6.2 | 8.5 ± 4.4 | 10.6 ± 4.1 |

| Diameter, n (%) | 5–10 mm | 138(85.2%) | 94(58.0%) | 39(84.8%) | 31(63.3%) |

| 10–20 mm | 22(13.6%) | 49(30.2%) | 5(10.9%) | 16(32.7%) | |

| 20–30 mm | 2(1.2%) | 19(11.7%) | 2(4.3%) | 2(4.1%) | |

| Stage, n (%) | Stage 0 | – | 39(24.1%) | – | 15(30.6%) |

| Stage I | – | 123(75.9%) | – | 34(69.4%) | |

| Smoke, n (%) | No | 83(51.2%) | 76(46.9%) | 25(54.3%) | 23(46.9%) |

| Yes | 17(10.5%) | 45(27.8%) | 8(17.4%) | 13(26.5%) | |

| Unknown | 62(38.3%) | 41(25.3%) | 13(28.3%) | 13(26.5%) | |

| Nodule type, n (%) | PS | 4(2.5%) | 32(19.8%) | 3(6.5%) | 7(14.3%) |

| GG | 62(38.3%) | 99(61.1%) | 32(69.6%) | 32(65.3%) | |

| SLD | 35(21.6%) | 15(9.3%) | 11(23.9%) | 10(20.4%) | |

| Unknown | 61(37.7%) | 16(9.9%) | – | – | |

| Cancer subtype, n (%) | Adenocarcinoma | – | 154(95.1%) | – | 48(98.0%) |

| Squamous cell | – | 8(4.9%) | – | – | |

| Others | – | – | – | 1(2.0%) | |

| Diagnosis method, n (%) | Clinical | 119(73.5%) | 0 | 32(69.6%) | 0 |

| Pathological | 43(26.5%) | 162(100%) | 14(30.4%) | 49(100%) | |

*Radiomics features were derived from 100 benign and 143 malignant cases within the training dataset, as well as from the entire cohort of the test dataset. All imaging/radiomics-related analyses were conducted within these samples

Performance of three base models and their pairwise combined model

As circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) concentrations in the blood are known biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and prognosis prediction [22–24], we first examined the total cfDNA levels in benign and malignant samples. In both the training and test sets, total cfDNA levels were significantly higher in malignant samples than in benign ones (P = 0.004 and 0.002, respectively; Supplemental Fig. 2). Despite this difference, the overall AUC for total cfDNA alone was 0.61, indicating that it had limited discriminatory power between benign and malignant nodules. Consequently, we proceeded with methylation sequencing to identify more specific molecular features for distinguishing lung nodule malignancy.

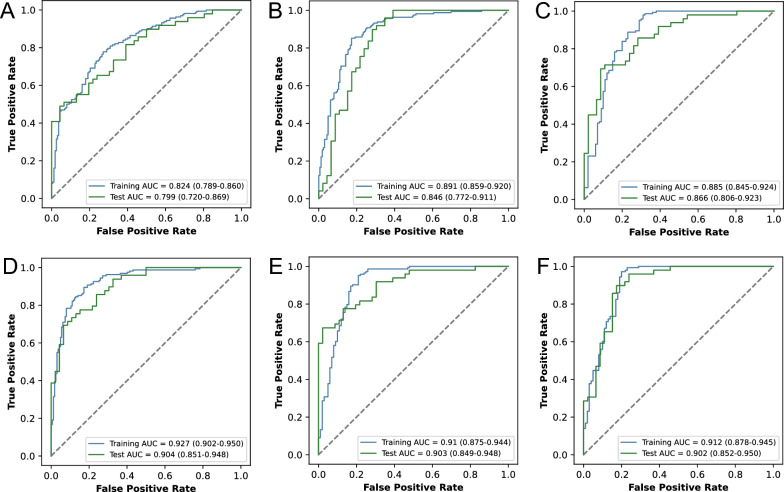

Methylated sequencing was performed on all samples using the ‘mTitan’ technology, which identified 1656 regions of methylation. Ten regions were excluded from further analysis because they had low methylation complexity with fewer than three CpG sites, which may introduce noise and skew the results. The remaining 1646 regions were used to generate MMS scores, which served as features for training the methylation base model. MMS aims to identify tumor-specific methylation haplotypes at the fragment level and assess the malignancy probability of a region based on the proportion of potentially malignant fragments. At the fragment level, a transformer model was utilized, leveraging a multihead attention mechanism to better utilize methylation sequence information and extract tumor-specific methylation signal features. On the training set, the methylation base model was trained using these MMS scores, achieving an AUC of 0.824 (95% CI 0.789–0.860) in distinguishing between MNs and BNs, with a sensitivity of 0.667 (0.59–0.736) and a specificity of 0.802 (0.732–0.859). The model on the test set achieved an AUC of 0.799 (0.72–0.869), with a sensitivity of 0.776 (0.634–0.874) and a specificity of 0.609 (0.456–0.741). (Fig. 2A, Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Performance of three base models and their pairwise combined models. ROC curves of models using methylation (A), protein (B), radiomics (C), methylation + protein (D), radiomics + methylation (E), and radiomics + protein (F) features on the training set and test cohorts

Table 2.

The performance of different models

| Model | Training set | Test set | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| Methylation | 0.667 (0.59–0.736) | 0.802 (0.732–0.859) | 0.776 (0.634–0.874) | 0.609 (0.456–0.741) |

| Protein | 0.858 (0.794–0.905) | 0.802 (0.732–0.859) | 0.837 (0.706–0.923) | 0.739 (0.588–0.851) |

| Methylation & protein | 0.907 (0.853–0.946) | 0.802 (0.732–0.859) | 0.878 (0.757–0.945) | 0.717 (0.566–0.83) |

| Radiomics | 0.832 (0.763–0.885) | 0.8 (0.711–0.871) | 0.714 (0.572–0.83) | 0.826 (0.686–0.919) |

| Methylation & radiomics | 0.902 (0.84–0.942) | 0.8 (0.711–0.871) | 0.776 (0.634–0.874) | 0.848 (0.717–0.927) |

| Protein & radiomics | 0.944 (0.893–0.974) | 0.8 (0.711–0.871) | 0.816 (0.685–0.903) | 0.848 (0.717–0.927) |

| Methylation & protein & radiomics | 0.958 (0.91–0.982) | 0.8 (0.711–0.871) | 0.837 (0.706–0.923) | 0.826 (0.686–0.919) |

Plasma samples were also collected and analyzed using PEA technology to measure blood protein levels. A total of 366 proteins were detected. By comparing the protein abundance of MNs and BNs, 15 proteins were found to be significantly different (FDR < 0.05, fold change ≥ 2, Supplementary Table 1). Some of these proteins have been linked to lung cancer progression in previous studies. For example, STAT5B, a transcription factor responding to cytokines and growth factors, was found to have lower expression in non-small cell lung cancer tissues compared to normal tissues, with higher STAT5B mRNA levels significantly associated with better overall survival [25]. APEX1 is involved in the recognition of damage and base repair at DNA damage sites. Significant downregulation of APEX1 has been found in lung epithelial cells and has been associated with cadmium-induced malignant transformation [26]. CDKN2D, a cell cycle inhibitor that prevents uncontrolled cell proliferation, was shown to inhibit the growth and migration of non-small cell lung cancer cells when its expression was increased [27]. CES3 is a member of the CES family, and it is significantly downregulated in early liver cancer [28]. PFKFB2 is an enzyme that plays a critical role in glucose metabolism, specifically in the regulation of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis. Recent findings have revealed that the expression of this protein is downregulated in colorectal cancer tissues and is associated with poorer survival [29]. These proteins or corresponding genes are mostly downregulated in blood or urine samples of lung cancers (see Supplementary Table 2) [30, 31]. When we performed unsupervised clustering based on these differentially expressed proteins (Supplementary Fig. 3), the results indicated that these proteins distinguished between MNs and BNs. Using the same fivefold cross-validation method based on these 366 protein features, a base protein model was trained. The model had AUCs of 0.891 (0.859–0.920) and 0.846 (0.772–0.911) on the training and test sets, respectively (Fig. 2B). The sensitivity and specificity in the training set were 0.858 (0.794–0.905) and 0.802 (0.732–0.859), respectively. In the test set, they were 0.837 (0.706–0.923) and 0.739 (0.588–0.851), respectively (Table 2). The protein model outperformed the methylation model but combining them may enhance predictive performance due to their complementary sensitivity and specificity.

An overview of our radiomics methodology is illustrated in Fig. 3. After manually segmenting the region of interest, we extracted a total of 1316 radiomic features from 338 samples, consisting of 100 BNs and 143 MNs in the training set, and 46 BNs and 49 MNs in the test set. By comparing malignant and benign nodules, 975 radiomic features showed significant differences (FDR < 0.05). The top 20 features were mainly related to characteristics derived from the gray level size zone matrix (GLSZM) and the neighborhood gray tone difference matrix (NGTDM) within the high-frequency components of the original image after wavelet transformation (Supplementary Table 3). Unsupervised clustering of the 338 samples based on these top 20 features showed that these radiomic features distinguished between malignant and benign nodules well (Supplementary Fig. 4). By utilizing the same fivefold cross-validation method on the 1316 radiomic features, the image base model achieved an AUC of 0.885 (0.845–0.924), with a sensitivity and specificity of 0.832 (0.763–0.885) and 0.8 (0.711–0.871), respectively, in the training set. Likewise, the AUC, sensitivity, and specificity obtained in the test set were 0.866 (0.806–0.923), 0.714 (0.572–0.83), and 0.826 (0.686–0.919), respectively (Fig. 2C, Table 2). These results demonstrate that radiomic features performed better than blood methylation and protein features. Notably, radiomic features had higher specificity than the other two base models in the test set.

Fig. 3.

Overview of the extraction of radiomic features

Using the scores from the base methylation and protein models as features, we trained a logistic regression model to discriminate between BNs and MNs. The model achieved AUCs of 0.927 (0.902–0.950) and 0.904 (0.851–0.948) on the training and test sets, respectively (Fig. 2D). The combined effect in the test set was significantly superior to that of either methylation (P = 0.01) or protein alone (P = 0.03, Supplementary Table 4). The sensitivity and specificity in the training set were 0.907 (0.853–0.946) and 0.802 (0.732–0.859), respectively, while in the test set they were 0.878 (0.757–0.945) and 0.717 (0.566–0.83) (Table 2).

Then, a logistic regression classifier was trained using the prediction scores from both the methylation and imaging models. In the training set, it achieved an AUC, sensitivity, and specificity of 0.91 (0.875–0.944), 0.902 (0.84–0.942), and 0.8 (0.711–0.871), respectively, while in the test set they were 0.903 (0.849–0.948), 0.776 (0.634–0.874), and 0.848 (0.717–0.927) (Fig. 2E). Incorporating methylation features into the imaging model significantly improved the AUC (P = 0.03, Supplementary Table 4) in the test set, slightly increased specificity, and raised sensitivity from 0.714 to 0.776 (Table 2).

Similarly, the combination of protein and imaging features achieved AUC, sensitivity, and specificity values in the training set of 0.912 (0.878–0.945), 0.944 (0.893–0.974), and 0.8 (0.711–0.871), respectively, while in the test set they were 0.902 (0.852–0.950), 0.816 (0.685–0.903), and 0.848 (0.717–0.927) (Fig. 2F). When protein features were added to the imaging model, the sensitivity improved from 0.714 to 0.816, and the specificity improved from 0.826 to 0.848.

Performance of the final integrative model

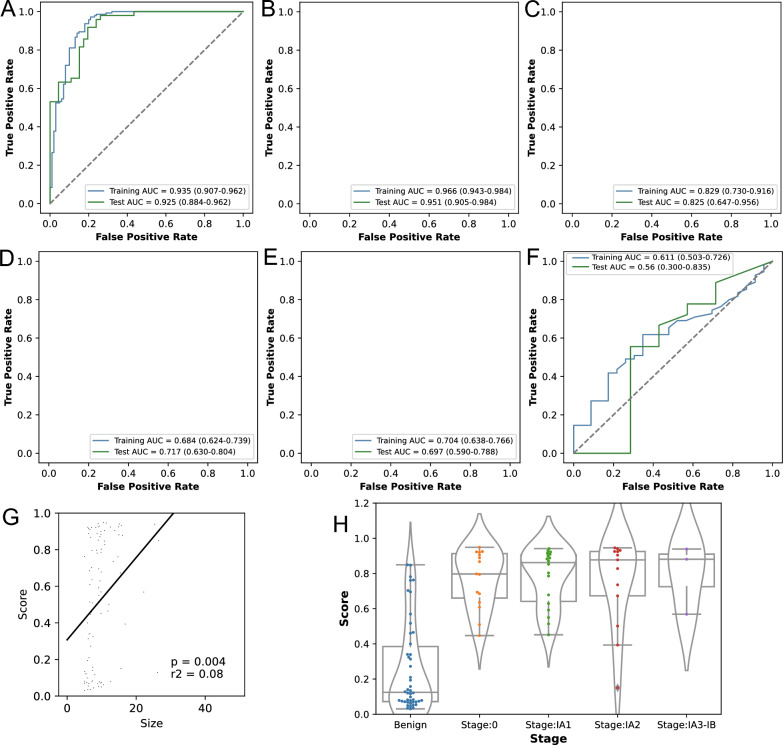

Finally, we combined the methylation, protein, and imaging scores to train a model for classifying BNs and MNs. In the training and test sets, this model achieved AUCs of 0.935 (0.907–0.962) and 0.925 (0.884–0.962), respectively (Fig. 4A). In the training set it achieved a sensitivity and specificity of 0.958 (0.91–0.982) and 0.8 (0.711–0.871), respectively, while in the test set these were 0.837 (0.706–0.923) and 0.826 (0.686–0.919) (Table 2). Overall, the composite model incorporating methylation, protein, and imaging features had a higher AUC and sustained the high specificity and sensitivity of the individual models, highlighting its superior performance in lung cancer screening compared to other individual or combined models.

Fig. 4.

Performance of the integrative model and its correlation with nodule size. A The AUC of the integrative model in all samples. B The AUC of the integrative model in nodules ≤ 10 mm. C The AUC of the integrative model in nodules > 10 mm. D The AUC of size in all samples. E The AUC of size in nodules ≤ 10 mm. F The AUC of size in nodules > 10 mm. G There was a moderate but significant correlation between nodule size and tumor score in the test cohort. H Cancer scores of the integrative model across different stages of the test set

The nodule size in this study significantly differed in both the training and test cohorts between MNs and BNs. As mentioned above, the size of the nodule is a crucial factor in determining whether a lung nodule is benign or malignant. Our imaging features include a large amount of information on nodule size, such as “Volume” and “AxisLength”, and the cancer score of the imaging model was also significantly correlated with nodule size, as shown in Fig. 4G. Furthermore, as there is substantial evidence that the level of circulating tumor DNA in the blood is positively associated with both the cancer stage and tumor volume [32], we compared the relationship between our integrated model's performance and nodule size in samples with CT images. The AUCs of nodule size in the training and test cohorts were significantly lower than our integrated model (both P < 0.001, Fig. 4D), suggesting that while nodule size can serve as a distinguishing factor between malignant and benign nodules within a cohort, it may not be sufficient for accurate predictions at the individual level.

By examining the performance of our integrated model in nodules of different sizes, we divided all nodules into those with a size of ≤ 10 mm and those with a size of > 10 mm, as distinguishing nodules around a size cutoff between 5 and 10 mm poses a challenge in clinical settings. The AUCs of the integrated model in the training and test ≤ 10 mm cohort were 0.966 (0.943–0.984) and 0.951 (0.905–0.984) (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Table 5), respectively, which were higher than the AUCs of nodule size (0.704, 0.697, Fig. 4E). In the test set of nodules with a size of ≤ 10 mm, the model demonstrated a high sensitivity and specificity of 0.839 (0.664–0.934) and 0.897 (0.759–0.964), respectively. In the test set, the individual methylation, protein, and imaging models achieved AUCs of 0.797 (0.701–0.879), 0.875 (0.804–0.943), and 0.88 (0.815–0.941), respectively, for 5–10 mm nodules (Supplementary Table 5). These AUCs were significantly lower than those of the integrated model (with p values from the DeLong test of 0.0044, 0.0085, and 0.0117, respectively). The AUCs for > 10 mm nodules were 0.829 and 0.825 in the training and test sets (Fig. 4C), respectively, which were still higher than those of nodule size (0.611, 0.56, Fig. 4F). Consistent with the above, the cancer scores of MNs also exhibited an upward trend from stage 0 to stage IA3-IB (Fig. 4H). Sensitivity at different stages can also be found in Supplementary Table 6. Radiomics analysis provides valuable insights beyond nodule size, capturing aspects of nodule morphology, texture, and other features. By integrating molecular features from circulating blood, such as methylation and protein levels, our model shows promise in improving the differentiation between BNs and MNs, particularly for nodules in the 5–10 mm range.

In the test set, most nodules are pure ground-glass (GG) nodules, accounting for 67.4% (64/95) of the total nodules. Among these GG nodules, 65.3% are malignant. When considering different densities of malignant tumors, the sensitivity of pure ground-glass nodules is 0.916(0.856–0.956), the sensitivity of part-solid (PS) nodules is 0.949(0.825–0.991), and the sensitivity of solid (SLD) nodules is 0.84(0.643–0.943). Subgroup analysis demonstrates that our model performs well across different density nodules, as there are no significant differences in scores for benign samples. Among the tumor samples, the model achieves the highest score in PS nodules and the lowest score in SLD nodules, with the score for GG falling in between (Supplementary Fig. 5).

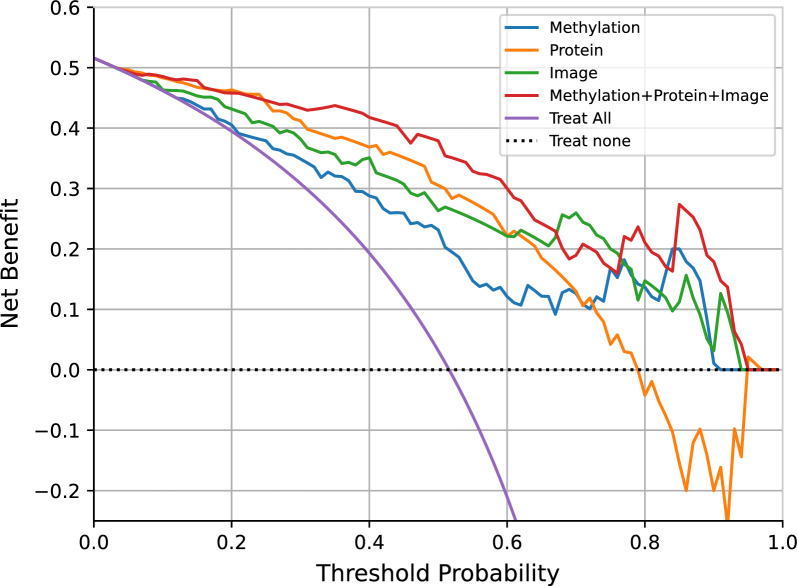

To assess the potential clinical utility of our models, we employed decision curve analysis (DCA) to help clinical decision-making by evaluating the corresponding net benefits. For different thresholds, samples with model scores surpassing the threshold are earmarked for intervention, while those falling below the threshold remain untreated. By weighting true positive benefits against false positive harms, the net benefit is calculated for each threshold. The net benefit is set at 0 for the curve representing no treatment. For the curve of treating all patients, the net benefit intersects with the y-axis and the curve of treating none at the malignant prevalence. When the net benefit of a model consistently surpasses those of the extreme curves within a wide range, it indicates a relatively safe selection of threshold ranges [33]. Compared to the strategy of treating all patients, the integrated model demonstrated higher net benefits in predicting malignant risk when the threshold probability exceeded 0.07 in the test set (Fig. 5). The threshold values between 0.07 and 0.6 yield a consistent net benefit of over 0.3. For instance, if an invasive intervention such as surgical resection or biopsy were deemed necessary at a risk threshold score higher than 0.5, the model would yield a net benefit of 37.9%. This implies that the model is equivalent to a strategy that led to invasive intervention in 379 out of 1000 individuals, with all biopsy results indicating cancer, while the actual positive rate in the test set is only 51.6%. We also analyzed the net benefit of the model for nodules ≤ 10 mm (Supplementary Fig. 6A) or pure ground-glass nodules (Supplementary Fig. 6B) in the test set. Compared to other models, the integrated model maintains a higher benefit over a larger threshold range. The curve demonstrates that across a range of probability thresholds, the integrated model offers a net benefit higher than the two extreme strategies and the three base models. These findings suggest that our model has potential clinical utility, potentially aiding in more informed decision-making for the management of pulmonary nodules.

Fig. 5.

Decision curve for the methylation, protein, imaging and final integrated model in the test set. The plot shows the net benefit (y-axis) across a range of thresholds (x-axis) of our four models compared with the treat-all approach and the treat-none approach in the test set

Discussion

The widespread implementation of LDCT has made it increasingly necessary but also challenging to accurately differentiate between MNs and BNs for effective lung cancer screening. In this study, we employed blood cfDNA methylation, proteomics, and radiomics imaging features to develop and validate an integrated model for diagnosing pulmonary nodules. Initially, we developed three separate base models using methylation, proteomics, and radiomic features. Each of these models performed well at distinguishing MNs from BNs. Remarkably, the imaging and protein-based models outperformed the methylation model. Finally, by combining all these features, an integrated model demonstrated superior performance to the individual base models. Collectively, our findings highlight the enhanced accuracy in distinguishing MNs from BNs through the application of multiomics analysis.

Previously, classifiers based on cfDNA methylation achieved AUCs ranging from 0.76 to 0.9 for distinguishing between benign and malignant pulmonary nodules [12, 34]. These findings demonstrate the potential of ctDNA methylation markers in the differential diagnosis of lung nodules. Therefore, we first employed targeted methylation sequencing technology to obtain the methylation data of patients with lung nodules for lung cancer screening [10]. To make robust and precise predictions from methylation sequencing data, we utilized a transformer model to identify specific methylation haplotypes in each region. This method has the potential to better discriminate between benign and malignant nodules. The methylation base model finally achieved an AUC of 0.799 in the test set, with a sensitivity of 0.776 and a specificity of 0.609.

Studies that utilize blood proteins to identify the malignancy of pulmonary nodules have mainly focused on a limited number of protein markers [35]. Here, we attempted to use high-throughput PEA technology to detect 366 tumor-related proteins in blood. By comparing the differences in their concentrations between MNs and BNs, we identified 15 significantly different proteins. In contrast to conventional blood protein markers used for identification, all these proteins were downregulated in malignant tumors. This suggests that the distinctions between benign and malignant lung nodules may not be the same as the distinctions observed between cancer and normal blood samples [36, 37]. The constructed protein base model also effectively distinguished between BNs and MNs and showed a better performance than the methylation model. With the addition of methylation features, the AUC of the test set significantly increased to 0.904. Hence, blood methylation and protein features exhibited a good complementary effect.

Apart from noninvasive blood-based detection methods, medical imaging represents an ideal means to capture tumoral heterogeneity in a noninvasive manner. Image-based diagnostic approaches for determining whether lung nodules are benign or malignant mainly rely on their size and their growth over time [38]. Other image features, such as radiomic textural features and morphological characteristics, can also effectively differentiate between benign and malignant nodules [39]. Using radiomic tools, we extracted 1316 engineered features from CT images. In addition to size-related features, we found several categories of features, such as gray level size zone matrix features, that showed significant differences between MNs and BNs. These features may be related to the malignancy potential of a nodule because texture heterogeneity can reflect changes in the tumor or adjacent region caused by the presence of neoplastic tissues within the nodule. These changes can include cell infiltration, abnormal angiogenesis, myxoid changes, and necrosis [40]. The base model made from these radiomic features achieved an AUC of 0.866, outperforming the methylation base model and performing as well as the protein base model. When we added the blood methylation and protein features, the model’s performance improved, with high AUC (0.925), sensitivity (0.837), and specificity (0.826). These results indicate that the three types of features complemented each other well.

In clinical practice, confirming the presence of lung cancer before an invasive procedure is challenging, especially when assessing small nodules in the early stages [41]. The sensitivity of the previously mentioned molecular models decreases as the size of the nodules decreases [34, 42]. While aggressive treatments benefit early-stage lung cancer patients, they may lead to overtreatment for a significant number of benign cases. Our integrated model also demonstrated excellent performance (AUC = 0.951) in identifying nodules smaller than 10 mm in the test set, with a sensitivity of 0.839 and a specificity of 0.897. While individual model AUCs for nodules ≤ 10 mm ranged from 0.80 to 0.88 in the test set, combining these models improved performance (Supplementary Table 5). The integrated model demonstrated superior accuracy in distinguishing small nodules, highlighting the advantage of combining features. DCA analysis also revealed that our integrated model maintained a higher net benefit for 5–10 mm nodules. Therefore, this combined multiomic approach shows promise as a non-invasive method for distinguishing between benign and malignant lung nodules, particularly in improving sensitivity for smaller nodules. It may help facilitate the more accurate identification of early-stage malignancies while potentially reducing overtreatment risks, thus holding potential value in early lung cancer screening. It should also be noted that, the model's enhanced performance for nodules ≤ 10 mm, compared to those > 10 mm, possibly due to the larger sample size of smaller nodules in our dataset. In the initial training set, small nodules constituted 71.6% (232 out of 324), and within the radiomics-featured subset, they made up 68% (165 out of 243). The test set also reflected this trend, with small nodules representing 73.7% (70 out of 95). In contrast, the model’s diminished performance with nodules larger than 10 mm may result from the limited sample size, leading to weaker generalization. To address this, we plan to gather additional samples for both training and validation. Our aim is to maintain strong performance with small nodules while improving the model’s accuracy for nodules larger than 10 mm. If sufficient data is available, we may also develop separate models tailored for nodules ≤ 10 mm and > 10 mm, to better meet the diverse needs of different clinical contexts.

Our study has some limitations. First, the process of extracting imaging features from manually segmented lung nodules by experts is time-consuming. Therefore, it may be crucial to explore automated or semiautomated nodule segmentation methods to speed up clinical workflows. Second, although our models were trained using cross-validation and their performance was validated on a single independent test set, an age imbalance existed between the benign and malignant samples in the test set (48.5 ± 12.5 vs. 59.5 ± 14.4 years). Although our model scores were not affected by patient sex (Supplementary Fig. 7A) or age (Supplementary Fig. 7B), further validation in larger datasets is necessary to account for the influence of various demographic and clinical factors. Third, although the model was developed using five-fold cross-validation and its performance was validated in the test set, its effectiveness may decrease in a real screening cohort. This is particularly concerning given that our benign samples were primarily determined by a multidisciplinary team based on discussions, imaging findings, and comprehensive follow-up evaluations. Factors such as variations in sample collection across centers and inconsistencies in the criteria for diagnosing benign lesions without pathological confirmation, as well as imaging annotation discrepancies, could reduce the model's generalizability compared to the test set. Additionally, we were the first to explore training methylation data using a transformer model. While deep learning typically requires large datasets, the limited availability of biological samples constrains this approach. Similar studies have trained models on datasets comprising over 200 in-house samples [43] or more than 1000 publicly available samples [44]. We are now enrolling a lung nodule follow-up cohort and implementing strict operating procedures for sample collection and management. This cohort aims to collect more samples, ensuring that benign samples are either confirmed by pathological evidence or have a follow-up period of at least 3 years, to validate the effectiveness of our integrated model.

Conclusions

This study presents a promising noninvasive approach to distinguish the malignancy or benignancy of pulmonary nodules using multiple molecular features and imaging features. The results indicate that using multiple modalities is effective in identifying malignant pulmonary nodules and has the potential to assist in clinical decision-making.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- cfDNA

Cell-free DNA

- CT

Computed tomography

- AUC

Area Under the Curve

- LC

Lung cancer

- LDCT

Low-dose computed tomography

- CA 125

Cancer antigen 125

- CEA

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- PEA

Proximity extension assay

- UMI

Unique molecular identifier

- MMS

Methylation malignancy score

- NPX

Normalized protein expression

- DICOM

Digital imaging and communications in medicine

- ROI

Region of interest

- NN

Neural network

- ReLU

Rectified linear unit

- BNs

Benign nodules

- MNs

Malignant nodules

- FDR

False discovery rate

- GLSZM

Gray level size zone matrix

- NGTDM

Neighborhood gray tone difference matrix

- DCA

Decision curve analysis

Author contributions

MY and PZ are the investigators. RL and ZS are the methodological lead. MY, ZS, RL led the study design. HY, HF, JD, KW, TB, YZ, WL, YW, CL, HS, DZ, BW, HC, CG. and QH collected and analyzed the data. MY, RL, ZS, WL, HY, HF, and JD wrote the manuscript. All authors had access to data reported in this study. All authors discussed the results, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Funding

This work was jointly supported by the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-NHLHCRF-LX-01), the National Key Research & Development Program of China (2019YFC1315800, 2019YFC1315803, 2023YFC2508605) and the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2021-I2M-1-012 ).

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the institutional independent ethics committee of China-Japan Friendship Hospital (ethics approval ID: B2020-92-K56). All patients signed informed consent prior to any study-related procedures. The study was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

RL reports stock ownership in Singlera Genomics and is an employee of Singlera Genomics. YZ, WL, CG, QH, ZS, RL. are employees of Singlera Genomics. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Meng Yang, Huansha Yu, Hongxiang Feng, Jianghui Duan, Kaige Wang, Bing Tong and Yunzhi Zhang have contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

Meng Yang, Email: yangm_zoe@163.com.

Zhixi Su, Email: zhixi.su@singleragenomics.com.

Rui Liu, Email: rliu@singleragenomics.com.

Peng Zhang, Email: zhangpeng1121@tongji.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bai C, Choi CM, Chu CM, Anantham D, Chung-Man Ho J, Khan AZ, Lee JM, Li SY, Saenghirunvattana S, Yim A. Evaluation of pulmonary nodules: clinical practice consensus guidelines for Asia. Chest. 2016;150:877–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, Scholten ET, Nackaerts K, Heuvelmans MA, Lammers JJ, Weenink C, Yousaf-Khan U, Horeweg N, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:503–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vachani A, Tanner NT, Aggarwal J, Mathews C, Kearney P, Fang KC, Silvestri G, Diette GB. Factors that influence physician decision making for indeterminate pulmonary nodules. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:1586–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi CZ, Zhao Q, Luo LP, He JX. Size of solitary pulmonary nodule was the risk factor of malignancy. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6:668–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu QX, Zhou D, Han TC, Lu X, Hou B, Li MY, Yang GX, Li QY, Pei ZH, Hong YY, et al. A noninvasive multianalytical approach for lung cancer diagnosis of patients with pulmonary nodules. Adv Sci. 2021;8:2100104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson DO, Ryan A, Fuhrman C, Schuchert M, Shapiro S, Siegfried JM, Weissfeld J. Doubling times and CT screen-detected lung cancers in the Pittsburgh lung screening study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:85–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beig N, Khorrami M, Alilou M, Prasanna P, Braman N, Orooji M, Rakshit S, Bera K, Rajiah P, Ginsberg J, et al. Perinodular and intranodular radiomic features on lung CT images distinguish adenocarcinomas from granulomas. Radiology. 2019;290:783–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen B, Yang L, Zhang R, Luo W, Li W. Radiomics: an overview in lung cancer management-a narrative review. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerr KM, Galler JS, Hagen JA, Laird PW, Laird-Offringa IA. The role of DNA methylation in the development and progression of lung adenocarcinoma. Dis Markers. 2007;23:5–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, Gole J, Gore A, He Q, Lu M, Min J, Yuan Z, Yang X, Jiang Y, Zhang T, et al. Non-invasive early detection of cancer four years before conventional diagnosis using a blood test. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Xie K, Zhu G, Ma C, Cheng C, Li Y, Xiao X, Li C, Tang J, Wang H, et al. Early detection and stratification of lung cancer aided by a cost-effective assay targeting circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) methylation. Respir Res. 2023;24:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang W, Chen Z, Li C, Liu J, Tao J, Liu X, Zhao D, Yin W, Chen H, Cheng C, et al. Accurate diagnosis of pulmonary nodules using a noninvasive DNA methylation test. J Clin Invest. 2021. 10.1172/JCI145973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostrin EJ, Bantis LE, Wilson DO, Patel N, Wang R, Kundnani D, Adams-Haduch J, Dennison JB, Fahrmann JF, Chiu HT, et al. Contribution of a blood-based protein biomarker panel to the classification of indeterminate pulmonary nodules. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16:228–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheung PK, Ma MH, Tse HF, Yeung KF, Tsang HF, Chu MKM, Kan CM, Cho WCS, Ng LBW, Chan LWC, Wong SCC. The applications of metabolomics in the molecular diagnostics of cancer. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2019;19:785–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong W, Edfors F, Gummesson A, Bergstrom G, Fagerberg L, Uhlen M. Next generation plasma proteome profiling to monitor health and disease. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He J, Wang B, Tao J, Liu Q, Peng M, Xiong S, Li J, Cheng B, Li C, Jiang S, et al. Accurate classification of pulmonary nodules by a combined model of clinical, imaging, and cell-free DNA methylation biomarkers: a model development and external validation study. Lancet Digit Health. 2023;5:e647–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lastwika KJ, Wu W, Zhang Y, Ma N, Zecevic M, Pipavath SNJ, Randolph TW, Houghton AM, Nair VS, Lampe PD, Kinahan PE. Multi-omic biomarkers improve indeterminate pulmonary nodule malignancy risk assessment. Cancers. 2023;15:3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Griethuysen JJM, Fedorov A, Parmar C, Hosny A, Aucoin N, Narayan V, Beets-Tan RGH, Fillion-Robin JC, Pieper S, Aerts H. Computational radiomics system to decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e104–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolpert DH. Stacked generalization. Neural Netw. 1992;5:241–59. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:14126980 2014.

- 21.Chollet F. Keras: The python deep learning library. Astrophysics source code library 2018:ascl: 1806.1022.

- 22.Diehl F, Schmidt K, Choti MA, Romans K, Goodman S, Li M, Thornton K, Agrawal N, Sokoll L, Szabo SA, et al. Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics. Nat Med. 2008;14:985–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, Kinde I, Wang Y, Agrawal N, Bartlett BR, Wang H, Luber B, Alani RM, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:224ra224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hao TB, Shi W, Shen XJ, Qi J, Wu XH, Wu Y, Tang YY, Ju SQ. Circulating cell-free DNA in serum as a biomarker for diagnosis and prognostic prediction of colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1482–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang M, Chen H, Zhou L, Chen K, Su F. Expression profile and prognostic values of STAT family members in non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11:4866–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li M, Chen W, Cui J, Lin Q, Liu Y, Zeng H, Hua Q, Ling Y, Qin X, Zhang Y, et al. circCIMT silencing promotes cadmium-induced malignant transformation of lung epithelial cells through the DNA base excision repair pathway. Adv Sci. 2023;10: e2206896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, Huang S. Fisetin inhibits the growth and migration in the A549 human lung cancer cell line via the ERK1/2 pathway. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15:2667–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quiroga AD, Ceballos MP, Parody JP, Comanzo CG, Lorenzetti F, Pisani GB, Ronco MT, Alvarez ML, Carrillo MC. Hepatic carboxylesterase 3 (Ces3/Tgh) is downregulated in the early stages of liver cancer development in the rat. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1862:2043–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu F, Wei X, Chen Z, Chen Y, Hu P, Jin Y. PFKFB2 is a favorable prognostic biomarker for colorectal cancer by suppressing metastasis and tumor glycolysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:10737–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kossenkov AV, Qureshi R, Dawany NB, Wickramasinghe J, Liu Q, Majumdar RS, Chang C, Widura S, Kumar T, Horng WH, et al. A gene expression classifier from whole blood distinguishes benign from malignant lung nodules detected by low-dose CT. Cancer Res. 2019;79:263–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang C, Leng W, Sun C, Lu T, Chen Z, Men X, Wang Y, Wang G, Zhen B, Qin J. Urine proteome profiling predicts lung cancer from control cases and other tumors. EBioMedicine. 2018;30:120–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newman AM, Bratman SV, To J, Wynne JF, Eclov NC, Modlin LA, Liu CL, Neal JW, Wakelee HA, Merritt RE, et al. An ultrasensitive method for quantitating circulating tumor DNA with broad patient coverage. Nat Med. 2014;20:548–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vickers AJ, van Calster B, Steyerberg EW. A simple, step-by-step guide to interpreting decision curve analysis. Diagn Progn Res. 2019;3:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li L, Fu K, Zhou W, Snyder M. Applying circulating tumor DNA methylation in the diagnosis of lung cancer. Precis Clin Med. 2019;2:45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silvestri GA, Tanner NT, Kearney P, Vachani A, Massion PP, Porter A, Springmeyer SC, Fang KC, Midthun D, Mazzone PJ, Team PT. Assessment of plasma proteomics biomarker’s ability to distinguish benign from malignant lung nodules: results of the PANOPTIC (pulmonary nodule plasma proteomic classifier) trial. Chest. 2018;154:491–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lung Cancer Cohort C. The blood proteome of imminent lung cancer diagnosis. Nat Commun. 2023;14:3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fahrmann JF, Marsh T, Irajizad E, Patel N, Murage E, Vykoukal J, Dennison JB, Do KA, Ostrin E, Spitz MR, et al. Blood-based biomarker panel for personalized lung cancer risk assessment. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:876–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Callister ME, Baldwin DR, Akram AR, Barnard S, Cane P, Draffan J, Franks K, Gleeson F, Graham R, Malhotra P, et al. British thoracic society guidelines for the investigation and management of pulmonary nodules. Thorax. 2015;70(Suppl 2):ii1–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawkins S, Wang H, Liu Y, Garcia A, Stringfield O, Krewer H, Li Q, Cherezov D, Gatenby RA, Balagurunathan Y, et al. Predicting malignant nodules from screening CT scans. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:2120–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bayanati H, Thornhill RE, Souza CA, Sethi-Virmani V, Gupta A, Maziak D, Amjadi K, Dennie C. Quantitative CT texture and shape analysis: can it differentiate benign and malignant mediastinal lymph nodes in patients with primary lung cancer? Eur Radiol. 2015;25:480–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balata H, Fong KM, Hendriks LE, Lam S, Ostroff JS, Peled N, Wu N, Aggarwal C. Prevention and early detection for NSCLC: advances in thoracic oncology 2018. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:1513–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang N, Li B, Jia Z, Wang C, Wu P, Zheng T, Wang Y, Qiu F, Wu Y, Su J, et al. Ultrasensitive detection of circulating tumour DNA via deep methylation sequencing aided by machine learning. Nat Biomed Eng. 2021;5:586–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim M, Park J, Seonghee O, Jeong BH, Byun Y, Shin SH, Im Y, Cho JH, Cho EH. Deep learning model integrating cfDNA methylation and fragment size profiles for lung cancer diagnosis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:14797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park MK, Lim JM, Jeong J, Jang Y, Lee JW, Lee JC, Kim H, Koh E, Hwang SJ, Kim HG, Kim KC. Deep-learning algorithm and concomitant biomarker identification for NSCLC prediction using multi-omics data integration. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.