Abstract

Background

One of the most prevalent unmet needs among cancer patients is the fear of disease progression (FoP). This cross-sectional study aimed to identify the relationships among uncertainty in illness (UI), intolerance of uncertainty (IU), and FoP among newly diagnosed cancer patients and to verify the mediating role of IU in the relationship between UI and FoP.

Methods

A total of 202 newly diagnosed cancer patients (male: 105, 51.98%; mean age: 47.45 ± 14.8 years; lung cancer: 49, 24.26%) were recruited by convenience sampling. The patients completed a homemade questionnaire that assessed demographic characteristics, the Fear of Progression Questionnaire-Short Form, the Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale, and the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale.

Results

The prevalence of FoP among newly diagnosed cancer patients was 87.62%, and the prevalences of high, medium, and low levels of UI were 15.84%, 73.27%, and 10.89%, respectively. The mean score on the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale was 41.19 ± 10.11. FoP among newly diagnosed cancer patients was positively correlated with UI (r = 0.656, P < 0.001) and IU (r = 0.711, P < 0.001). Moreover, IU was positively correlated with UI (r = 0.634, P < 0.001). IU partially mediated the effect of UI on FoP, accounting for 47.60% of the total effect.

Conclusions

Newly diagnosed cancer patients have a high prevalence of FoP. UI can directly or indirectly affect FoP through the mediating role of IU. Healthcare professionals can help newly diagnosed cancer patients mitigate their FoP by reducing IU in light of UI.

Keywords: Newly diagnosed Cancer, Fear of Disease Progression, Uncertainty in illness, Intolerance of uncertainty

Introduction

The latest statistics indicate approximately 19.29 million new cancer cases worldwide in 2020 [1]. Similarly, epidemiological data from China revealed that there are approximately 4.06 million new cancer cases annually [2]. The diagnosis and treatment of cancer is a critical transitional period associated with significant physical and emotional changes in patients. However, the distress symptoms they experience are often underestimated, and their psychological needs are underappreciated and underaddressed [3, 4]. Fear of disease progression (FoP) is a major stressor for patients with life-threatening diseases. It is defined as “the biopsychosocial consequences that come with disease progression or fear of relapse” [5]. Generally, a moderate level of FoP is a normal adaptive response that could promote health behaviors in patients [6]. However, excessive FoP can lead to emotional disorders such as anxiety and depression [7], worry [8], stress perception [9], and impaired quality of life [10, 11]. Additionally, it can trigger changes in health behavior, such as avoidance or excessive medical screening [12, 13], increased alcohol use [14], and reduced physical activity [14]. Nevertheless, research related to FoP among newly diagnosed cancer patients is scarce. Thus, understanding the current status of FoP and its influencing factors among newly diagnosed cancer patients is critical for developing tailored interventions for these patients.

Uncertainty in illness (UI) is often mentioned as a possible explanation for FoP; however, it has not been explored in depth as a potential mechanism underlying the development of FoP [15]. UI is “the inability to determine the meaning of illness-related events and accurately anticipate or predict health outcomes” [16]. According to the uncertainty in illness theory, uncertainty is generated when components of illness, treatment-related stimuli, and illness-related events possess characteristics such as inconsistency, randomness, complexity, unpredictability, and lack of information in situations important to the individual [17]. Some studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between UI and FoP [18, 19]. However, some researchers have raised the puzzling issue that although UI is common in cancer patients, not all patients have high levels of FoP [15]. Some studies have proposed that the perception of uncertainty and ambiguity is essential to an individual’s emotional response [20, 21]. Therefore, is the UI or the patient’s perception of and reaction to the UI influencing FoP? This question warrants further exploration.

Intolerance of uncertainty (IU) is often described as a cognitive bias where uncertainty and ambiguity are perceived as threats [22] and is defined as “an individual’s tendency to react negatively on an emotional, cognitive, and behavioral level to uncertain situations and events“ [23]. Individuals with high levels of IU experience uncertainty as stressful and have difficulty functioning in unpredictable situations. IU is a crucial vulnerability and transdiagnostic factor contributing to various forms of psychopathology [24–26]. It may also be an important factor in the relationship between UI and FoP. However, the literature on the relationship between IU and FoP in cancer patients is inconclusive. On the one hand, some studies have shown that IU is a psychological factor that contributes directly to clinical FoP [27]. On the other hand, some studies have shown that IU does not predict FoP [28, 29]. Therefore, we sought to determine the role of IU in the relationship between UI and FoP among newly diagnosed cancer patients.

This cross-sectional study aimed to identify the relationships between UI, IU, and FoP among newly diagnosed cancer patients and verify the mediating role of IU in this relationship. The IU may act as a mediating mechanism influencing the effect of UI, the predictor variable, on FoP, the outcome variable (Fig. 1) [30]. Therefore, this study provides foundational data for devising practical and helpful intervention strategies to mitigate FoP among newly diagnosed cancer patients.

Fig. 1.

The proposed mediation model

Methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study applied convenience sampling to recruit participants from the oncology departments of two tertiary general hospitals in Changsha, Hunan Province, China. The inclusion criteria for participants were as follows: [1] over 18 years [2], first diagnosed with cancer within 6 months, confirmed via pathology [3], able to speak Mandarin and read Chinese questionnaires, and [4] understood the purpose and process of the study and provided informed consent. The exclusion criteria were as follows: [1] experienced cancer recurrence [2], had a history of psychiatric disorders or severe psychological or cognitive disorders, or [3] were critically ill and unable to cooperate with the investigation. The sample size was calculated using the sample size formula for descriptive cross-sectional studies N=(uασ/δ)2. The sample size was estimated at a 95% confidence level, and the admissible error did not exceed 1. Based on the results from the preliminary investigation, the mean FoP score of newly diagnosed cancer patients was 40.12 ± 7.21, and the calculated sample size was 200. Considering an invalid rate of 10%, the final sample size was 220.

Procedures

The data were collected from March to May 2023. The investigators were trained systematically prior to the investigation. Participants were informed of the purpose and procedures of the study, provided the questionnaires, and were instructed to answer questions with explanations and clarifications after signing the informed consent form. For those who could not complete the questionnaires independently, the researcher asked the questions orally and completed the questionnaires for the patients according to their answers. Upon completion, the researchers collected the questionnaires and checked for completeness and quality. The participants were asked to address any missing or paradoxical information with careful reconsideration. Ultimately, 220 questionnaires were distributed in this study, of which 202 fully responded, for an effective response rate of 91.81%. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (2022-S382). All participants provided written informed consent.

Measures

Sociodemographic questionnaire

The research team developed this self-report questionnaire based on a literature review and the study objectives. It included sex, age, monthly income, marital status, mode of payment for medical expenses, education level, cancer type, cancer stage, and cancer-related treatments received (including chemotherapy, surgery, radiotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and other therapies).

Fear of Progression Questionnaire-Short Form (FoP-Q-SF)

The Fear of Progression Questionnaire-Short Form (FoP-Q-SF) was first developed by Mehnert et al. [26], and the Chinese version was adapted and revised by Wu et al. [31]. This scale includes 12 items across 2 dimensions (physiological health dimension and socio-family dimension). The physiological health dimension, which consists of 6 items, evaluates an individual’s fear related to disease and health. The socio-family dimension, which includes 6 items, evaluates an individual’s fear of socio-family functioning. Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1="never” to 5="very often”. Total scores ranged from 12 to 60, with higher scores indicating higher levels of FoP. A score of at least 34 indicated psychological dysfunction. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the total scale was 0.916, with the physical health and socio-family dimensions being 0.890 and 0.865, respectively.

Mishel’s uncertainty in illness scale (MUIS)

The Mishel Illness Uncertainty Scale (MUIS) [17] was translated into Chinese and revised by Professor Xu [32]. This scale includes 25 items across two dimensions: 15 items in the uncertainty subscale and 10 in the complexity subscale. The uncertainty dimension reflects a patient’s unclear understanding of their illness—its nature, progression, treatment, and prognosis—due to insufficient information or cognitive limitations. The complexity dimension, on the other hand, captures the intricacies of the illness and treatment, including the complexity of its etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations and the variety and unpredictability of treatment options and outcomes. A 5-point Likert scale was used for each item, with scores ranging from 1 to 5, representing “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. Total scores on this measure range from 25 to 125, with higher scores indicating higher levels of UI. The total scores were divided into three levels: low (25–58), moderate (59–91), and high (92–125). The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the total scale in this study was 0.820, with the uncertainty and complexity dimensions being 0.807 and 0.845, respectively.

Intolerance of uncertainty scale (IUS)

IU was measured using the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale, developed by Carleton et al. [33]; the Chinese version was developed by Wu et al. [34]. The Chinese version includes 12 items across three dimensions: anticipatory behavior (behavior caused by fear of future events), inhibitory behavior (experiential behavior caused by uncertainty), and anticipatory emotion (emotions caused by uncertainty about future events). Responses to each item were scored on a 5-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 1 to 5 representing “not match at all” to “completely match”. Total scores on this measure range from 12 to 60, with higher scores indicating a higher level of IU. The Cronbach α coefficient for the total scale in this study was 0.866, with the anticipatory behavior dimension, the inhibitory behavior dimension, and the anticipatory emotion dimension being 0.727, 0.849, and 0.844, respectively.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 24.0; Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables with a normal distribution are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), whereas categorical variables are summarized as absolute numbers and percentages. FoP scores among newly diagnosed cancer patients with different sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were compared using t- and χ2 tests. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to determine the correlation between quantitative variables. Multivariate stepwise linear regression analysis was subsequently conducted to explore factors influencing FoP among newly diagnosed cancer patients. Finally, to examine the hypothesized mediation model (Fig. 1), we used the PROCESS macro (Model 4) [35], with UI as the independent variable, FoP as the dependent variable, and IU as the mediating variable. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics identified as statistically significant in the univariate analysis of FoP were entered into the model as control variables. The mediation model was verified using the bootstrap method, and the mediating effect was considered significant if the 95% confidence interval did not include zero. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P < 0.05.

Results

Sample characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 202 participants included in the study are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 47.45 years (SD = 14.8 years). A total of 72.77% of the patients were married. Among these patients, lung cancer was the most prevalent (49, 24.36%), followed by colorectal cancer (28, 13.86%) and gastric cancer (28, 13.86%). The majority of respondents (91.09%) were covered by China’s National Basic Medical Insurance, a fundamental healthcare system designed to provide financial protection and access to essential medical services for residents. The results of the univariate analysis revealed a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) in the level of FoP among patients in different age groups, cancer stages, and different types of cancer treatment, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of fear of disease progression scores in participants with different characteristics (n = 202)

| item | Frequency | Ratio(%) | FoP | t/F value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 3.780a | 0.053 | |||

| Male | 105 | 51.98 | 40.76 ± 9.38 | ||

| Female | 97 | 48.02 | 43.14 ± 7.90 | ||

| Age group(year) | 16.500b | < 0.001** | |||

| < 40 | 66 | 32.67 | 41.58 ± 10.06 | ||

| 40∼59 | 94 | 46.53 | 44.74 ± 6.47 | ||

| ≥ 60 | 42 | 20.79 | 36.07 ± 8.22 | ||

| Average monthly income(CNY) | 1.185b | 0.317 | |||

| <3000 | 65 | 32.18 | 42.46 ± 10.02 | ||

| 3000∼4999 | 75 | 37.13 | 40.49 ± 9.61 | ||

| 5000∼10000 | 44 | 21.78 | 42.64 ± 6.34 | ||

| > 10,000 | 18 | 8.91 | 44.00 ± 3.14 | ||

| Marital status | 0.119a | 0.730 | |||

| Unmarried/divorced/widowed | 55 | 27.23 | 42.25 ± 10.89 | ||

| Married | 147 | 72.77 | 41.78 ± 7.86 | ||

| Type of medical insurance | 1.342 | 0.250 | |||

| National basic medical insurance | 184 | 91.09 | 41.62 ± 8.43 | ||

| National basic medical insurance combined with commercial health insurance | 6 | 2.97 | 48.33 ± 0.52 | ||

| Fully self-funded | 12 | 5.94 | 43.92 ± 9.13 | ||

| Education level | 0.696 | 0.555 | |||

| Primary school and below | 27 | 13.37 | 40.52 ± 10.49 | ||

| Junior high school or secondary school | 57 | 28.22 | 42.61 ± 8.58 | ||

| Senior high school or junior college | 75 | 37.13 | 42.51 ± 9.13 | ||

| University and above | 43 | 21.29 | 40.79 ± 7.10 | ||

| Type of Cancer | 1.315 | 0.219 | |||

| Breast cancer | 15 | 7.43 | 43.53 ± 8.42 | ||

| Prostate cancer | 6 | 2.97 | 36.33 ± 12.40 | ||

| Lymphoma | 7 | 3.47 | 38.57 ± 10.31 | ||

| Thyroid cancer | 9 | 4.46 | 44.22 ± 6.42 | ||

| Leukaemia | 7 | 3.47 | 37.00 ± 15.45 | ||

| Colorectal cancer | 28 | 13.86 | 43.54 ± 6.92 | ||

| Liver cancer | 6 | 2.97 | 35.67 ± 6.71 | ||

| Lung cancer | 49 | 24.26 | 42.20 ± 8.10 | ||

| Gastric cancer | 28 | 13.86 | 43.46 ± 6.96 | ||

| Esophageal cancer | 6 | 2.97 | 38.33 ± 11.69 | ||

| others | 41 | 20.3 | 42.39 ± 8.47 | ||

| Stage of cancer | 2.614 | 0.037* | |||

| I | 112 | 55.45 | 42.58 ± 8.13 | ||

| II | 31 | 15.35 | 43.13 ± 9.39 | ||

| III | 47 | 23.27 | 38.31 ± 8.94 | ||

| IV | 12 | 5.94 | 44.33 ± 7.27 | ||

| Types of cancer-related treatment received | 2.901 | 0.023* | |||

| 0 | 19 | 9.41 | 37.16 ± 6.16 | ||

| 1 | 110 | 54.46 | 42.98 ± 8.87 | ||

| 2 | 43 | 21.29 | 39.95 ± 10.08 | ||

| 3 | 23 | 11.39 | 43.17 ± 6.23 | ||

| ≥ 4 | 7 | 3.47 | 45.71 ± 5.68 |

Note: FoP = Fear of disease progression,a equals t value, b equals F value, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

FoP, UI, and IU among newly diagnosed Cancer patients

The total FoP scores for newly diagnosed cancer patients ranged from 12 to 60 (mean: 41.91 ± 8.76). The mean scores on the physical health dimension and the family dimension were 21.13 ± 4.46 and 20.77 ± 4.80, respectively. A total of 177 participants (87.62%) had a score of ≥ 34, indicating psychological dysfunction. In addition, the mean UI score was 78.61 ± 14.43; the mean scores for the uncertainty and complexity dimensions were 51.37 ± 12.38 and 27.24 ± 4.00, respectively. The prevalence rates of high, medium, and low levels of UI were 15.84%, 73.27%, and 10.89%, respectively. Moreover, the mean IU score was 41.19 ± 10.11, and the mean scores on the anticipatory behavior, anticipatory emotion, and inhibitory behavior dimensions were 20.36 ± 5.43, 10.63 ± 2.63, and 10.20 ± 2.64, respectively.

Correlation analysis of FoP, UI, and IU among newly diagnosed Cancer patients

FoP scores were positively correlated with both UI (r = 0.656, P < 0.001) and IU (r = 0.711, P < 0.001). Similarly, IU positively correlated with UI (r = 0.634, P < 0.001). Table 2 lists the main variables and the Pearson correlation coefficients between dimensions.

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients among variables and dimensions (n = 202)

| Variables (Dimensions) | FoP | Physical health | Socio-family | UI | Uncertainty | Complexity | IU | Anticipatory behavior | Anticipatory emotion | Inhibitory behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FoP | 1 | 0.943** | 0.951** | 0.656** | 0.711** | 0.168* | 0.711** | 0.685** | 0.711** | 0.609** |

| Physical health | 1 | 0.792** | 0.568** | 0.641** | 0.064 | 0.677** | 0.660** | 0.674** | 0.564** | |

| Socio-family | 1 | 0.671** | 0.702** | 0.247** | 0.671** | 0.638** | 0.672** | 0.588** | ||

| UI | 1 | 0.967** | 0.613** | 0.634** | 0.638** | 0.587** | 0.533** | |||

| Uncertainty | 1 | 0.392** | 0.679** | 0.677** | 0.646** | 0.564** | ||||

| Complexity | 1 | 0.185** | 0.203** | 0.116 | 0.175* | |||||

| IU | 1 | 0.971** | 0.934** | 0.905** | ||||||

| Anticipatory behavior | 1 | 0.860** | 0.805** | |||||||

| Anticipatory emotion | 1 | 0.813** | ||||||||

| Inhibitory behavior | 1 |

Note: FoP = Fear of disease progression, UI = Uncertainty in illness, IU = Intolerance of uncertainty, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

Multiple stepwise linear regression analysis of FoP among newly diagnosed cancer patients

Multiple linear stepwise regression analysis was performed with FoP as the dependent variable. The independent variables included UI, IU, and the variables identified as statistically significant in the univariate analysis of FoP (age group, cancer stage, and number of cancer-related treatments received). The independent variables were assigned the following values: age group, < 40 years = 1, 40–59 years = 2, ≥ 60 years = 3; stage of cancer, I = 1, II = 2, III = 3, IV = 4; and number of cancer-related treatments received, 0 = 1, 1 = 2, 2 = 3, 3 = 4, and ≥ 4 = 5. The multiple linear stepwise regression analysis revealed that UI and the IU were predictive factors for FoP among newly diagnosed cancer patients, explaining 57.2% of the total variance in FoP, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Multiple linear stepwise regression analysis of FoP in newly diagnosed patients (n = 202)

| Independent variables | Regression coefficient | Standard error | Standardized regression coefficient | t value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 7.888 | 2.262 | - | 3.487 | < 0.001 |

| UI | 0.208 | 0.036 | 0.343 | 5.756 | < 0.001 |

| IU | 0.428 | 0.052 | 0.494 | 8.281 | < 0.001 |

Note: FoP = Fear of disease progression, UI = Uncertainty in illness, IU = Intolerance of uncertainty, R2 = 0.577, adjusted R2 = 0.572, F = 135.531, P < 0.001

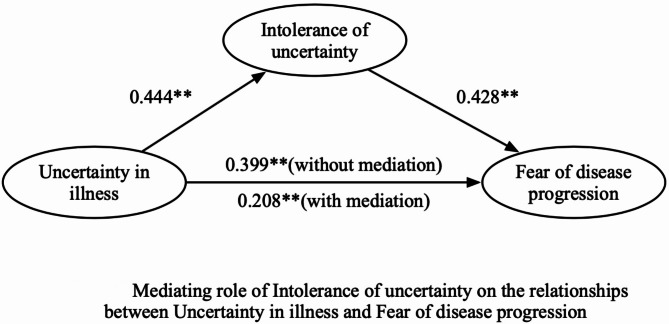

Mediating effect of IU on the relationship between UI and FoP

After controlling for sociodemographic and clinical variables (age group, cancer stage, and number of cancer-related treatments received), UI had a significant total effect on FoP (effect value = 0.399, P < 0.001) and IU (effect value = 0.444, P < 0.001). Furthermore, IU had a positive effect on FoP (effect value = 0.428, P < 0.001), whereas UI directly affected FoP after controlling for IU (effect value = 0.208, P < 0.001). The mediation effect value was calculated as 0.444*0.428, which is 0.190, and the ratio of the mediating effect to the total effect was 47.6% (0.190/0.399 = 0.476). In addition, the mediating effect test was conducted via the bootstrap method with 1000 samples. The results showed that the 95% confidence interval of the mediating effect value of IU did not include zero (95% CI: 0.175∼0.471, Z = 2.452, P = 0.014), indicating that IU had a significant mediating effect on the relationship between UI and FoP. The mediating effects of IU on the relationship between UI and FoP are outlined in Table 4, and the mediation model is shown in Fig. 2.

Table 4.

Mediating effect of IU on the relationship between UI and FoP (n = 202)

| Effect | Pathways | Effect | Standard error | 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | UI = > FoP | 0.399 | 0.032 | 0.335–0.462 | < 0.001 |

| Direct effect | UI = > FoP | 0.208 | 0.036 | 0.137–0.279 | < 0.001 |

| Indirect effect | UI = > IU = > FoP | 0.190 | 0.078 | 0.175–0.471 | < 0.001 |

| UI = > IU | 0.444 | 0.038 | 0.369–0.519 | < 0.001 | |

| IU = > FoP | 0.428 | 0.052 | 0.327–0.529 | < 0.001 |

Note: FoP = Fear of disease progression, UI = Uncertainty in illness, IU = Intolerance of uncertainty

Fig. 2.

Mediating role of Intolerance of uncertainty on the relationships between Uncertainty in illness and Fear of disease progression

Discussion

The current study aimed to investigate more thoroughly how UI and IU may contribute to the severity of FoP. Overall, this study highlights the important role of IU in the relationship between UI and FoP. In our study, 79.3% of newly diagnosed cancer patients reported clinical FoP. This prevalence rate is higher than rates reported in studies by Luo et al. [36] (64.6%) and Chen et al. [37] (56.4%). This discrepancy may derive from varying cancer types, sample sizes, or geographical regions across studies. In the context of Chinese society, which is characterized by collectivism and a strong family focus, patients frequently worry about increasing the financial and caregiving burden on their families, increasing their anxiety regarding disease progression [38]. Furthermore, Liu et al. [39] noted that the social stigma surrounding cancer may further exacerbate feelings of isolation and shame, amplifying these fears. Therefore, healthcare providers may enhance screening for FoP among newly diagnosed cancer patients to facilitate early identification, diagnosis, and intervention, thereby mitigating adverse outcomes associated with FoP [40].

The results of this study revealed that approximately 90% of newly diagnosed cancer patients had moderate to high levels of UI, which is higher than the results reported for long-term cancer survivors [41, 42]. We hypothesized that this difference may be attributed to the initial stage of a cancer diagnosis, which often lacks information and clarity, resulting in increased anxiety and uncertainty [16]. In contrast, long-term survivors usually navigate through various stages of treatment and have a better understanding of their condition, contributing to a sense of predictability regarding their health. In addition, our results showed that UI was positively correlated with FoP among newly diagnosed cancer patients. The regression analysis also verified that UI was a predictive factor for FoP, indicating that higher UI predicts higher levels of FoP. This finding is consistent with studies by Guo et al. [18] and Ye et al. [19]. UI for cancer patients may be caused by insufficient disease-related information, conflicting information provided by various sources, the complexity of the information that is difficult to understand, the unpredictability of disease outcomes, poor financial status, and inadequate social support [43]. However, some studies have shown that UI involves not only negative emotions but also hope for disease treatment and rehabilitation in the future [44]. This suggests that assessing the UI for newly diagnosed cancer patients is beneficial in identifying specific problems and causes of uncertainty.

Additionally, our findings demonstrate a positive correlation between IU and FoP, and the regression analysis results showed that IU can positively predict the level of FoP. This finding is in line with the study by Song et al. [24]. Notably, the results also revealed that IU partially mediates the relationship between UI and FoP, suggesting that UI has an indirect positive effect on FoP through increased IU. The core of IU is an inherent, dispositional fear of the unknown [45]. When newly diagnosed with cancer, patients with low uncertainty tolerance, compared with patients with high uncertainty tolerance, have more catastrophic expectations of the outcome of cancer development, tend to evaluate ambiguous information as a threat, and are therefore more afraid of further cancer development. In practice, due to the severity of cancer and individual differences, even experienced healthcare professionals cannot accurately predict the trajectory of the disease for newly diagnosed patients, making it challenging to reduce patients’ disease uncertainty. However, healthcare professionals can try to reduce the fear of not knowing how the disease will progress by increasing patients’ tolerance for uncertainty. As emphasized by Carleton [45], who developed the fear of the unknown theory, attempting to predict and control uncertainty may be less effective for reducing fear and anxiety than increasing one’s ability to tolerate uncertainty. A meta-analysis of 91 studies revealed that cognitive-emotional coping strategies are core influencing factors for IU [46]. Similarly, in an investigation conducted by our research team on patients who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, FoP was associated with maladaptive coping strategies such as rumination, contemplation, and catastrophizing [47]. These findings suggest that changing cognition and coping styles may effectively reduce IU in cancer patients. Furthermore, studies have shown that cognitive-behavioral therapy can moderate the IU level by regulating disease perception and cognitive-emotional coping styles. Mindfulness was also confirmed as a protective factor against the negative psychological effects of IU [48]. Therefore, interventions, including cognitive‒behavioral therapy and mindfulness, are promising strategies for establishing positive adaptive cognitive‒emotional coping strategies and avoiding negative maladaptive coping strategies to reduce IU and ultimately decrease the level of FoP.

Study limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the sample size was limited; we included only newly diagnosed cancer patients from two hospitals in Changsha, Hunan Province, China, representing only a small sample size. Second, the study design is cross-sectional, and although the research assumptions are based on theories in the literature, the results should be interpreted with caution. Future studies could address this limitation by obtaining longitudinal data to strengthen the causal relationships among UI, IU, and FoP. Finally, this study focused on IU, UI and FoP in newly diagnosed cancer patients and did not encompass other psychological factors that may play a significant role, such as personality traits and resilience. These two factors are recognized as critical mediators of cancer patients’ responses to stressors. Future research should integrate these factors to develop a more comprehensive understanding of how to address and cope with FoP in newly diagnosed cancer patients.

Conclusions

Newly diagnosed cancer patients have a high incidence of FoP. Both UI and IU are associated with FoP, and IU partially mediates the effect of UI on FoP. Medical personnel should prioritize addressing FoP among this population. Additionally, IU may serve as a potential therapeutic target to decrease FoP in newly diagnosed patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the participants in this study.

Abbreviations

- FoP

Fear of disease progression

- UI

Uncertainty in illness

- IU

Intolerance of uncertainty

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Zhiying Shen, Chengyuan Li and Chunhong Ruan; methodology, Zhiying Shen and Li Zhang; software, Zhiying Shen and Shuangjiao Shi; investigation, Li Zhang, Dan Li; writing-original draft preparation, Zhiying Shen and Shuangjiao Shi; writing-review and editing, Chengyuan Li and Li Zhang; supervision, Chengyuan Li, Li Zhang and Chunhong Ruan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2023JJ40884), the General Project of the Hunan Health Commission (B202314018897), and the China Scholarship Council Program ([2023]54).

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (2022-S382). The study followed the ethical guidelines and regulations outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All the patients who participated in the study signed the informed consent in person.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical trail number

Not applicable.

Dual publication

The results, data and figures in this manuscript have not been published elsewhere, nor are they under consideration by another publisher.

Third party material

All of the material is owned by the authors and no permissions are required.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng R, Zhang S, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K, Chen R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2016. J Natl Cancer Cent. 2022;2(1):1–9. 10.1016/j.jncc.2022.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghoshal S, Miriyala R, Elangovan A, Rai B. Why newly diagnosed Cancer patients require supportive care? An audit from a Regional Cancer Center in India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22(3):326–30. 10.4103/0973-1075.185049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyes AW, Girgis A, D’Este CA, Zucca AC, Lecathelinais C, Carey ML. Prevalence and predictors of the short-term trajectory of anxiety and depression in the first year after a cancer diagnosis: a population-based longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(21):2724–9. 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.7540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dankert A, Duran G, Engst-Hastreiter U, Keller M, Waadt S, Henrich G, et al. Fear of progression in patients with cancer, diabetes mellitus and chronic arthritis. Rehabilitation (Stuttg). 2003;42(3):155–63. 10.1055/s-2003-40094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ocalewski J, Michalska P, Izdebski P, Jankowski M, Zegarski W. Fear of Cancer Progression and Health Behaviors in patients with colorectal Cancer. Am J Health Behav. 2021;45(1):138–51. 10.5993/AJHB.45.1.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su CH, Liu Y, Hsu HT, Kao CC. Cancer fear, emotion regulation, and emotional distress in patients with newly diagnosed Lung Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2024;47(1):56–63. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000001150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinkel A, Marten-Mittag B, Kremsreiter K. Association between Daily Worry, pathological worry, and fear of progression in patients with Cancer. Front Psychol. 2021;12:648623. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall DL, Lennes IT, Pirl WF, Friedman ER, Park ER. Fear of recurrence or progression as a link between somatic symptoms and perceived stress among cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(5):1401–7. 10.1007/s00520-016-3533-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuang X, Long F, Chen H, Huang Y, He L, Chen L, et al. Correlation research between fear of disease progression and quality of life in patients with lung cancer. Ann Palliat Med. 2022;11(1):35–44. 10.21037/apm-21-2821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee I, Park C. The mediating effect of social support on uncertainty in illness and quality of life of female cancer survivors: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):143. 10.1186/s12955-020-01392-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vrinten C, Waller J, von Wagner C, Wardle J. Cancer fear: facilitator and deterrent to participation in colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(2):400–5. 10.1158/1055-9965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Y, Li W, Wen Y, Wang H, Sun H, Liang W, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2019;28(4):675–86. 10.1002/pon.5013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall DL, Jimenez RB, Perez GK, Rabin J, Quain K, Yeh GY, et al. Fear of Cancer recurrence: a model examination of physical symptoms, emotional distress, and Health Behavior Change. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(9):e787–97. 10.1200/JOP.18.00787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mishel MH. Reconceptualization of the uncertainty in illness theory. Image J Nurs Sch. 1990;22(4):256–62. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1990.tb00225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mishel MH. Uncertainty in illness. Image J Nurs Sch. 1988;20(4):225–32. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1988.tb00082.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mishel MH. The measurement of uncertainty in illness. Nurs Res. 1981;30(5):258–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo HT, Wang SS, Zhang CF, Zhang HJ, Wei MX, Wu Y, et al. Investigation of factors influencing the fear of Cancer recurrence in breast Cancer patients using structural equation modeling: a cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pract. 2022;2022:2794408. 10.1155/2022/2794408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye CL, Xie XL, Luo ML, Huang LH, Xu XP. Correlation among the fear of Cancer recurrence, uncertainty in illness and social support in postoperative patients with breast Cancer. Nurs J Chin PLA. 2019;36(11):23–6. 10.3969/j.issn.1008-9993.2019.11.006 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huntley C, Young B, Tudur Smith C, Jha V, Fisher P. Testing times: the association of intolerance of uncertainty and metacognitive beliefs to test anxiety in college students. BMC Psychol. 2022;10(1):6. 10.1186/s40359-021-00710-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dugas MJ, Gagnon F, Ladouceur R, Freeston MH. Generalized anxiety disorder: a preliminary test of a conceptual model. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36(2):215–26. 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00070-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hebert EA, Dugas MJ. Behavioral experiments for intolerance of uncertainty: challenging the unknown in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Pract. 2019;26(2):421–36. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.07.007 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buhr K, Dugas MJ. The role of fear of anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty in worry: an experimental manipulation. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47(3):215–23. 10.1016/j.brat.2008.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song J, Cho E, Cho IK, Lee D, Kim J, Kim H, et al. Mediating effect of intolerance of uncertainty and Cancer-related dysfunctional beliefs about sleep on psychological symptoms and fear of Progression among Cancer patients. Psychiatry Investig. 2023;20(10):912–20. 10.30773/pi.2023.0127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Y, Gorka SM, Pennell ML, Weinhold K, Orchard T. Intolerance of uncertainty and cognition in breast Cancer survivors: the mediating role of anxiety. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(12):3105. 10.3390/cancers [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehnert A, Herschbach P, Berg P, Henrich G, Koch U. Fear of progression in breast cancer patients–validation of the short form of the fear of Progression Questionnaire (FoP-Q-SF). Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2006;52(3):274–88. 10.13109/zptm.2006.52.3.274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waroquier P, Delevallez F, Razavi D, Merckaert I. Psychological factors associated with clinical fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer patients in the early survivorship period. Psychooncology. 2022;31(11):1877–85. 10.1002/pon.5976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lebel S, Maheu C, Tomei C, Bernstein LJ, Courbasson C, Ferguson S, et al. Towards the validation of a new, blended theoretical model of fear of cancer recurrence. Psychooncology. 2018;27(11):2594–601. 10.1002/pon.4880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomei C, Lebel S, Maheu C, Lefebvre M, Harris C. Examining the preliminary efficacy of an intervention for fear of cancer recurrence in female cancer survivors: a randomized controlled clinical trial pilot study. Supportive Care Cancer. 2018;26(8):2751–62. 10.1007/s00520-018-4097-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–82. 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu QY, Ye ZX, Li L, Liu PY. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of fear of Progression Questionnaire-Short Form for cancer patients. Chin J Nurs. 2015;50(12):1515–9. 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2015.12.021 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu SL, Huang XL. Test of Chinese Version of Mishel’s illness uncertainty scale. J Nurs Res. 1996;4(1A):59–69. http://ir.fy.edu.tw/ir/handle/987654321/3428 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carleton RN, Norton MA, Asmundson GJ. Fearing the unknown: a short version of the intolerance of uncertainty scale. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21(1):105–17. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu LJ, Wang JN, Qi XD. Validity and reliability of the intolerance of uncertainty Scale-12 in middle school students. Chin Mental Health J. 2016;30(9):700–5. 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2017.02.020 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayes AF, Rockwood NJ. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav Res Ther. 2017;98:39–57. 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luo X, Li W, Yang Y, Humphris G, Zeng L, Zhang Z, et al. High fear of Cancer recurrence in Chinese newly diagnosed Cancer patients. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1287. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen R, Yang H, Zhang H, Chen J, Liu S, Wei L. Fear of progression among postoperative patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer: a cross-sectional survey in China. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1):168. 10.1186/s40359-023-01211-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu QR, Liu QY, Fang S, Ma YJ, Zhang BX, Li HH, et al. Relationship between fear of progression and symptom burden, disease factors and social/family factors in patients with stage-IV breast cancer in Shandong, China. Cancer Med. 2024;13(4):e6749. 10.1002/cam4.6749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu X, Zhong J, Ren J, Zhang JE. The formation of Stigma and its Social consequences on Chinese people Living with Lung Cancer: a qualitative study. Oncol nurs Forum. 2023;50(5):589–98. 10.1188/23.ONF.589-598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pradhan P, Sharpe L, Menzies RE. Towards a stepped care model for managing fear of Cancer recurrence or progression in Cancer survivors. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:8953–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu Z, Sun D, Sun J. Social Support and Fear of Cancer recurrence among Chinese breast Cancer survivors: the mediation role of illness uncertainty. Front Psychol. 2022;13:864129. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.864129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hall DL, Mishel MH, Germino BB. Living with cancer-related uncertainty: associations with fatigue, insomnia, and affect in younger breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(9):2489–95. 10.1007/s00520-014-2243-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Langmuir T, Chu A, Sehabi G, Giguère L, Lamarche J, Boudjatat W, et al. A new landscape in illness uncertainty: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of the experience of uncertainty in patients with advanced cancer receiving immunotherapy or targeted therapy. Psychooncology. 2023;32(3):356–67. 10.1002/pon.6093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han PKJ, Gutheil C, Hutchinson RN, LaChance JA. Cause or Effect? The role of prognostic uncertainty in the fear of Cancer recurrence. Front Psychol. 2020;11:626038. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.626038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carleton RN. The intolerance of uncertainty construct in the context of anxiety disorders: theoretical and practical perspectives. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(8):937–47. 10.1586/ern.12.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sahib A, Chen J, Cárdenas D, Calear AL. Intolerance of uncertainty and emotion regulation: a meta-analytic and systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2023;101:102270. 10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen ZY, Li CY, Shi SJ, Ruan CH. The mediating effect of illness perception and cognitive emotion regulation on the relationship between social constraints and fear of cancer recurrence among hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patient. J Nurs Sci. 2023;38(22):10–4. 10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2016.06.105 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao NS, Yang Y, Shu S, Yin XC. Influence of intolerance of uncertainty on emotional disturbance: mediating Effect of Coping and moderating Effect of Mindfulness. Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Pekinensis. 2023;59(2):317–25. 10.13209/j.0479-8023.2023.005 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.