Abstract

Background

A review of key learnings from the response to the COVID-19 pandemic in nursing homes in Ireland can inform planning for future pandemics. This study describes barriers and facilitators contributing to COVID-19 outbreak management from the perspective of frontline teams.

Methods

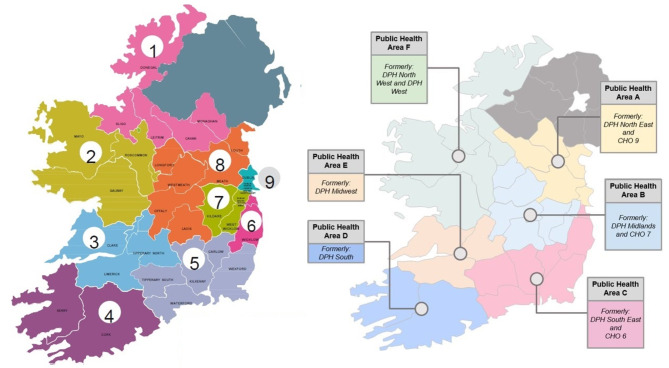

A qualitative study involving ten online focus group meetings was conducted. Data was collected between April and June 2023. The focus group discussions explored the views, perceptions and experiences of COVID-19 Response Team (CRT) members, clinical/public health experts who worked with them, and care professionals who worked in frontline managerial roles during the pandemic. All nine Community Healthcare Organisations and six Public Health Areas in Ireland were represented. Inductive reflexive thematic analysis was carried out using NVivo Pro 20.

Results

In total, 54 staff members participated in focus group meetings. Five themes were developed from a thematic analysis that covered topics related to (1) infection prevention and control challenges and response to the pandemic, (2) social model of care and the built environment of nursing homes, (3) nursing home staffing, (4) leadership and staff practices, and (5) support and guidance received during the pandemic.

Conclusions

The response to the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a steep learning curve, internationally and in Ireland. Preparing better for future pandemics not only requires changes to infection control and outbreak response but also to the organisation and operation of nursing homes. There is a great need to strengthen the long-term care sector’s regulations and support around staffing levels, nursing home facilities, governance, use of technology, infection prevention and control, contingency planning, and maintaining collaborative relationships and strategic leadership. Key findings and recommendations from the Irish example can be used to improve the quality of care and service delivery at local, national, and policy levels and improve preparedness for future pandemics, in Ireland and internationally.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-20451-7.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Coronavirus, Long-term residential care facilities, Nursing homes, Outbreak management, Pandemic preparedness, COVID-19 response team, Infection control, Ireland

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the profound impact of public health emergencies on healthcare infrastructures globally. The abrupt nature of such epidemics often challenges the capacities of healthcare systems to respond swiftly to the disease and reduce mortality rates [1, 2]. Like other settings, the pandemic challenged long-term residential care facilities (LTRCFs) to protect lives and support the health and well-being of residents in their care. It also highlighted the risk to staff from physical illness and also psychological burnout [3], itself a factor in maintaining high-quality care for residents. The course of the pandemic was punctuated by emergent new variants, often with different features including the capacity to cause serious illness and ease of transmission, which amplified the risk over time to care homes, with their vulnerable residents living in an outbreak-prone environment. This risk was particularly high in the pre-vaccine phase of the pandemic response. The virus often presented with unusual symptoms in older people [4], and many residents also had additional underlying health conditions [5]. Sadly, the COVID-19-related mortality rate in Ireland was high in frail older people, with 89.4% of those who died were aged over 65 and 76% had underlying illnesses [6] with a median age of death at 82 years old [7, 8].

The virus was first documented in Ireland in late February 2020, and cases were soon confirmed in many countries. The Health Information and Quality Authority [9] reports that the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in a nursing home in Ireland was reported on 13 March 2020. By the end of March, the virus had spread to many long-term residential care facilities (LTRCFs). There were 257 clusters (defined as five or more cases) in nursing homes and 184 clusters in other residential settings [9], with healthcare workers also disproportionately affected by COVID-19. Before the SARS-CoV-2 reached the country, Ireland’s Department of Health established the National Public Health Emergency Team for COVID-19 (NPHET) in January 2020. The NPHET oversaw and provided national direction, support, guidance, and expert advice on developing and implementing a strategy to control the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland [10]. Advice and support to LTRCFs were available from the Department of Health, local public health officials, crisis management teams in each Community Health Organisation (CHO) area of the Health Service Executive (HSE), and the Infection Prevention and Control Hub in the Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA). In addition, COVID-19 Response Teams (CRTs) were established to provide guidance and support for staff in managing risk from COVID-19 in LTRCFs to facilitate preparedness and implement any necessary emergency measures such as onsite staffing provision.

The Irish response to the COVID-19 pandemic was similar to other countries, which focused on COVID-19 preparedness and response strategies, and plans were developed to support national action and resource mobilisation. In many countries, including Ireland, the COVID-19 response plans were broadly aligned with global guidance and the associated thematic pillars for preparedness and response outlined by the World Health Organisation’s Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan, which included country-level coordination, planning and monitoring, risk communication, surveillance, and rapid response teams [11].

The NPHET in Ireland recommended the establishment of an Expert Panel on Nursing Homes to examine the complex issues surrounding the management of COVID-19 among this vulnerable cohort. This panel published the COVID-19 Nursing Homes Expert Panel Report [12] and the present study was commissioned by the HSE to address one of the recommendations listed in this report [13]. Therefore, the present study explored the experiences and perspectives of Ireland’s CRTs about the management of COVID-19 outbreaks in nursing homes. The findings of this study will directly contribute to future pandemic preparedness planning in Ireland and will set the Irish health system’s experience as an example on the international stage.

Methods

Aim

This study aimed to explore the barriers and facilitators in COVID-19 outbreak management in LTRCFs in Ireland from the perspective of the CRTs, and key learnings and priority areas for outbreak prevention and future pandemic preparedness.

Research questions

What were the barriers to effective outbreak management in nursing homes that could be addressed in either guidance, training, or regulatory/policy practice updates?

What were the key learnings from practice and experience that improved outbreak management in nursing homes over the multiple waves?

What are the priority areas for more effective infection prevention and control and future pandemic preparedness in nursing homes in Ireland?

Design

This descriptive study used a qualitative design with focus group interviews. Focus groups were used to generate discussion among participants and identify as many themes as possible. Evidence shows that sensitive topics are more likely to arise during a focus group than during individual interviews [14] as, collectively, the group acquires and affirms common experiences and perceptions [15], thus facilitating a deeper understanding of different perspectives about individual viewpoints regarding the topic of interest. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research 32-item checklist guided the reporting process [16].

Setting

In Ireland, six Public Health Areas and nine Community Healthcare Organisations (CHOs) deliver services outside the acute hospital system, including primary care, social care, mental health, and health and wellbeing services [17]. Health Services Executive (HSE) runs all of the public health services in Ireland and its funded agencies to people in local communities [17]. At the beginning of the pandemic, there were 576 registered nursing homes in Ireland, with approximately 32,000 residential places [9]. Nursing homes are operated by a mixture of HSE (public), private and voluntary bodies. By 2020, private and voluntary nursing homes were the largest service providers in this sector, operating eight out of 10 nursing home beds in the country (80%).9 While the average number of beds in nursing homes nationally is just over 56, they range in size from nine to 184 beds [9]. Therefore, there is significant variation in the nature of the built environment in nursing home accommodation available nationwide, ranging from modified former private homes or institutions, to purpose-built modern facilities.

In Ireland, 18 CRTs (which were renamed as COVID-19 Support Teams towards the end of the pandemic) were in place across the 9 CHO areas, generally consisting of: a service manager, public health department representatives, Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) Link Practitioners (who are trained persons at a community health and care facility with a dedicated role to support service providers in implementing effective IPC practices in their facility or service [18]), consultant geriatrician or other link consultant from local acute hospital to support provision of clinical care and be a point of contact with general practitioners and Directors of Nursing during management of COVID-19 outbreak in nursing homes, clinician working in mental health or disability services, and mental health service and disability service managers [19].

Participants and their recruitment

The inclusion criteria for the study were: (1) being a staff member who has been a member of a CRT or having worked with a CRT during the pandemic, and (2) agreeing to participate in the study and signing the consent form. Participants were recruited from each Community Healthcare Organisation (CHO) [20] and Public Health Area [21] in Ireland (Fig. 1). The CHO Chief Officers were informed about the study, and Heads of the Quality Safety and Service Improvement and Older People Services within each CHO were contacted about the focus groups by email. They informed the staff members in their area by distributing the flyers, participant information leaflets and consent forms by email. Area Directors of Public Health distributed the same materials to the staff members in their area. Interested staff members contacted the lead researcher (DS) directly by email with their further questions and sent their signed consent forms. The lead researcher confirmed the participants’ attendance at the focus group discussions by email and informed them about interview dates and times.

Fig. 1.

Community Health Organisations (CHOs) [20] and public health areas [21] of Ireland (as of March 2023)

Data collection

Online focus group interviews, mostly comprising 4–6 participants in each group, were conducted using an online video conferencing platform (Microsoft Teams) between April and June 2023. Online data collection was chosen to encourage participation, reduce travel time and costs, and prevent disruption of participants’ work schedules. After consent was obtained from all participants, sessions were audio recorded. There were two researchers in each focus group, one leading the discussions (DS) and the second researcher (SD) taking notes and asking further questions where needed. A semi-structured interview guide was used, which was developed by the researchers for this study (supplementary files 1 and 2 for the interview guide and focus group discussions guide). The questions of the interview guide were not previously published elsewhere. During the interviews, the participants were asked to clarify which wave of the pandemic they were referring to when describing their experiences to compare the differences between earlier and later waves. Each participant had equal chances to get involved in discussions. In total, 10 focus group discussions were conducted, each lasting 1.5–2 h. The recordings were transcribed verbatim, and the names of all participants were removed to ensure anonymity and confidentiality.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using inductive reflexive thematic analysis on NVivo Pro 20 software. An inductive analysis was chosen as the most appropriate since this allowed identifying unexpected themes [22]. Braun and Clarke’s [22, 23] step-by-step guide to conducting a reflexive thematic analysis was followed. The stages of the thematic analysis included:

Step 1. Data familiarisation and writing familiarisation notes - Transcripts were read through repeatedly to encourage data immersion.

Step 2. Systematic data coding - The information relevant to the research questions was highlighted and labelled with codes by two independent data coders (DS and SD), who were blinded to each other’s coding decisions.

Step 3. Generating initial themes from coded and collated data - The manual coding in NVivo was done through an inductive process for profound comprehension to generate categories and themes from the data.

Step 4. Developing and reviewing themes – The initial themes were reviewed by both researchers and a third, independent researcher (MD). Following that, the themes were revised to ensure that they reflected the data.

Step 5. Refining, defining and naming themes – The final themes were defined following the discussions between the researchers.

Step 6. Writing the report – a comprehensive report was prepared with supporting direct quotes.

Rigour and trustworthiness

To ensure trustworthiness, validity and methodological rigour, the study triangulated data by exploring insights of health professionals with different roles, levels of responsibility, and locations (data source triangulation) and using multiple researchers in the analysis phase—DS, SD, and MD (investigator triangulation) [24]. As the codes were drawn directly from the original data, the participants’ perspectives were accurately represented [25]. Two researchers (DS and SD) analysed the data separately. The backgrounds of the researchers were similar as both had academic degrees in public health and clinical experience in infection control in community care settings, similar to the study participants. The researchers met regularly to clarify the data analysis process, which involved discussing the codes, themes and sub-themes generated by each researcher. During the data analysis meetings, it was clear that the researchers’ interpretations of the transcripts were very similar, providing convincing evidence that the interpretation of the data was trustworthy. Any differences that occurred were resolved by discussion. Further data reviews were carried out by re-reading the transcripts after the initial themes were agreed upon to validate the findings further. A third researcher (MD), who did not participate in data collection, read over the transcripts, codes, categories and initial themes to consider the feasibility of the codes and initial themes and validate the findings.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Research ethics committee approvals were obtained from two independent ethics committees (University of Galway Research Ethics Committee, ref. no 2022.06.010, 19.08.2022 and HSE Galway Clinical Research Ethics Committee ref. no C.A. 2848, 15.09.2022). Participants’ confidentiality and anonymity were protected at all times. A distress protocol was in place if any participant became distressed about the sensitive and potentially upsetting discussions; however, it was not needed during the interviews. All participants signed an informed consent form before their participation, and their verbal consent was obtained before the recording was turned on during the interview.

Findings

Initially, 60 staff members from CHOs and Public Health teams agreed to take part in focus group interviews and signed consent forms. However, six participants did not attend the interviews due to personal or work-related reasons; as a result, 54 participated in the focus group interviews. Some participants had previous experience working as a Director of Nursing or Person-in-Charge in a nursing home before moving to CRTs or Public Health teams. Some of them were IPC team members who were part of a multidisciplinary team of a healthcare organisation and worked with all healthcare staff, nursing home residents and visitors. Table 1 presents a summary of the participant characteristics; however, their exact titles and work locations are not presented to maintain confidentiality.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the focus group interview participants

| Interview number | Role | Background | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interview 1 |

• COVID-19 Response Team Coordinator • Community Healthcare Network Manager • General Manager, Older Person’s Residential Services • Consultant in Public Health Medicine • Infection Prevention and Control Development Officer • Director of Nursing/Assistant Director of Nursing in Infection Prevention and Control • Director of Nursing/Assistant Director of Nursing in a Nursing Home • Clinical Nurse Manager in Health Protection • Staff Nurse in Infection Prevention and Control |

Nursing = 11 Medicine = 1 | Female = 12 |

| Interview 2 |

• Consultant in Public Health Medicine • Assistant Director of Nursing in Infection Prevention and Control • Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control • Clinical Nurse Manager in Health Protection • Staff Nurse in Health Protection |

Nursing = 5 Medicine = 1 |

Female = 6 |

| Interview 3 |

• Director of Nursing in a Community Hospital • Assistant Director of Nursing in Infection Prevention and Control • Clinical Nurse Manager in Older Person Services |

Nursing = 4 | Female = 4 |

| Interview 4 |

• Specialist Public Health Medicine • General Manager in Older Persons Services • Director of Nursing in a Nursing Home • Clinical Nurse Manager in Community Healthcare |

Nursing = 3 Medicine = 1 |

Female = 4 |

| Interview 5 |

• COVID-19 Response Team Clinical Lead • Senior Director • Consultant in Public Health Medicine • Assistant Director of Nursing in Infection Prevention and Control |

Medicine = 2 Nursing = 2 |

Female = 4 |

| Interview 6 |

• Director of Nursing/Assistant Director of Nursing in a Nursing Home • Assistant Director of Nursing in a Community Nursing Unit • Clinical Nurse Manager in Health Protection |

Nursing = 4 | Female = 4 |

| Interview 7 |

• Nursing Home Support Lead • Assistant Director of Nursing in Infection Prevention and Control • Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control • Clinical Nurse Manager in Health Protection • Staff Nurse in Infection Prevention and Control |

Nursing = 6 | Female = 6 |

| Interview 8 |

• Director of Nursing for Community Nursing Units within Older Persons Services • Assistant Director of Nursing in Infection Prevention and Control • Assistant Director of Nursing in a Nursing Home • Clinical Nurse Manager in a Nursing Home |

Nursing = 4 | Female = 4 |

| Interview 9 |

• Senior director • Specialist Registrar Public Health Medicine • Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control • Clinical Nurse Manager in Health Protection • Clinical Nurse Manager in Infection Prevention and Control • Director of Nursing in a Nursing Home |

Nursing = 4 Medicine = 2 |

Female = 5 Male = 1 |

| Interview 10 |

• Health Promotion and Improvement Officer • Director of Nursing in Older Person Services • Director of Nursing in a Nursing Home • Support officer |

Medicine = 1 Nursing = 2 Human resources = 1 |

Female = 2 Male = 2 |

Following the thematic analysis, five main themes were developed. Direct quotes from the focus group interviews are presented in Table 2 to support the findings presented under the themes and subthemes below.

Table 2.

Direct quotes from the focus group interviews to support the themes and subthemes

| Sub-theme | Direct quote |

|---|---|

| Theme 1. Infection prevention and control challenges and response to the pandemic | |

| Barriers to IPC due to PPE, outbreak recognition, knowledge, and service organisation |

1.1.1 “PPE was another thing in the beginning. A lot of the nursing homes were caught short with the PPE supply. We had to stand up, and the HSE had to stand up and supply emergency oxygen and emergency PPE to these nursing homes, work the weekends, work late into the evenings, making sure that the appropriate PPE were in for our staff…” (Interview 1) 1.1.2 “Typically, especially in the first wave, some of the residents would be off form… but they hadn’t considered that they were COVID-19. For example, they weren’t eating; they didn’t want to get up out of bed. So, they weren’t typical symptoms, but then they did deteriorate quite quickly…” (Interview 2) |

| Rapid training of all staff as a facilitator to maintain IPC | 1.2.1 “We have done a huge amount of webinars, and we invited everyone, including the private nursing homes, and that really helped.” (Interview 2) |

| New waves, different experiences: Improved IPC measures and PPE supply, and the vaccine era | 1.3.1 “I definitely think it’s worth mentioning symptom vigilance again… the nursing homes that were sort of very vigilant…and diagnosed and isolated cases earlier probably prevented… more spread earlier on.” (Interview 9) |

| The need for better outbreak preparedness and more resources |

1.4.1 “Because training them to respond in the middle of a catastrophe is not really ideal. …everybody should be able to just go into autopilot and just function at a safe level.” (Interview 5) 1.4.2 “Unless something is made a standard or written into legislation, it’s very difficult to attract funding in that direction.” (Interview 7) |

| Theme 2 - Social model of care and the built environment of nursing homes | |

| Homely environment: contradicting needs |

2.1.1 “While I might have been in saying, look, I would rather you had everything wipeable, they were saying, well, it is a person’s home and …we have to make it homely, whereas I would be saying if you can get nice wipeable looking furniture and doesn’t look non-homely.” (Interview 2) 2.1.2 “The newer buildings definitely coped better. In terms of facilities and just the fabric of the building in general, and ventilation being a big thing, and the size of the rooms and dayrooms and the spaces made a huge difference.” (Interview 2) 2.1.3 “I think the structures of some of the buildings actually made it very difficult to cohort. And so, when they had cases to isolate, people were in shared rooms and bathrooms, and then even across floors, even they couldn’t cohort the staff caring for those with COVID and those without. And that made it very challenging” (Interview 10) |

| Staff commitment to IPC and creativity to adapt to change |

2.2.1 “…we identified additional rooms that could be reconfigured into single rooms to meet that need. That was a short-term intervention… but, you know, people were very inventive with what, how they could create a single room to meet that need.” (Interview 5) 2.2.2 “So, it wasn’t always the fabric of the building, it was how the staff were working with it.” (Interview 4) |

| The balance between IPC and residents’ quality of life | 2.3.1 “I think we need more IPC structure, you know, but not hindering into the real social aspect of the nursing home.” (Interview 9) |

| Theme 3 – Nursing home staffing | |

| Inadequate staffing levels due to staff on sick leave and absenteeism |

3.1.1 “Because they were low on staff going into it before the outbreaks even started, and then when the outbreaks started, they were dropping like flies” (Interview 2). 3.1.2 “I think another barrier was location… and we found that many of the private nursing homes in more rural locations were already operating from a very, very skeletal staff. And they found it extremely difficult to get agency staff to travel there, so that was a huge barrier to their outbreak management.” (Interview 1) |

| Mutual learning among staff and pandemic preparedness |

3.2.1 “It didn’t matter what grade you were, once you were working in that facility, your role was to share and support that information and that skill with whoever was working and delivering care.” (Interview 5) 3.2.2 “It’s a useful programme …in terms of passing on information and being a …communicative tool between infection control and ground level work and maybe between public health and ground level work.” (Interview 9) |

| Theme 4 – Leadership and staff practices | |

| Stress and emotional burden of staff |

4.1.1 “People were very afraid of doing things wrong.” (Interview 1) 4.1.2 “But you were dealing with the unknown. So, you were taking the chance, and you had that on your conscience all the time, making the decision…” (Interview 6). |

| Good leadership and communication are essential |

4.2.1 “I saw the people [managers] who stayed in the trenches and hid. And those that came out to the frontline, and we stood shoulder to shoulder… we were here at ten, eleven o’clock at night… laughing and crying together, trying to manage, trying to get staff in.” (Interview 3) 4.2.2 “I think there should be a special purpose course for persons in charge for managing nursing homes, to highlight, you know, those particular governance elements that may be different to other services in healthcare.” (Interview 7) |

| Establishing and maintaining links between teams is key to effective outbreak management | 4.3.1 “Over the three years we have, we gained their trust, and we work well together, and I think that’s a very positive result from the pandemic you know, going forward. They work really well with us, and we work well with them.” (Interview 1) |

| Theme 5 - Support and guidance received during the pandemic | |

| Frequently changing guidelines caused information overload | 5.1.1 “Sometimes they were saying something at 9 o’clock and then saying something different at 10 o’clock. So that was extremely confusing.” (Interview 10) |

| Issues with governance | 5.2.1 “We in the HSE had no power to enforce changes” (Interview 7). |

| COVID-19 Response Teams and other expert support |

5.3.1 “There was a good relationship between all the PICs and all the CNUs and the infection control team, so we all worked together in that. Even now, if there is anything that we are unaware about, we are all a phone call away.” (Interview 7) 5.3.2 “Pre-pandemic, you could get access to certain services, but other services you couldn’t get access to. So, I had access to palliative care, I didn’t have access to dieticians, OT. Once your address became a private facility, you no longer had access to those services. You didn’t exist. Now it’s equal access to those things.” (Interview 7) |

| Access to information and use of technology |

5.4.1 “Making sure that the most current guideline was available to staff was a challenge because you were totally dependent on paper.” (Interview 5) 5.4.2 “Their nursing system was electronic; all their nurses were out sick but one. Their CNM2 was out sick, the DON was out sick. So, we were left with a system, an electronic system that we couldn’t access. So, we had very little information on residents. So, we had to just start compiling our own paper information.” (Interview 3) |

Theme 1 - infection prevention and control challenges and response to the pandemic

Sub-theme 1.1 barriers to IPC due to PPE, outbreak recognition, knowledge, and service organisation

The participants reported that during the early waves of the pandemic, a lack of sufficient amount of personal protective equipment (PPE) resulted in staff getting infected rapidly, which led to a drastic decline in staff levels in nursing homes. Despite significant efforts to procure PPE, there was a discrepancy between PPE supplies and national recommendations for their use (Quote 1.1.1). Furthermore, a lack of rapid on-site testing and staff trained to perform swabs extended waiting times for test results from external laboratories. Some stated that delayed recognition of COVID-19 outbreaks was due to over-reliance on checking the temperatures of residents and staff and atypical manifestation of COVID-19 in older people (Quote 1.1.2).

Different levels of IPC knowledge and competence in staff was another barrier highlighted by participants. Healthcare assistants undertook most care tasks due to significantly reduced nursing staff levels while receiving only basic care training. Unplanned resident hospital discharge and transfers from hospitals to nursing homes and the constant movement of residents within the nursing home building to isolate them brought additional challenges to outbreak management, particularly if the IPC measures were not implemented properly.

Sub-theme 1.2 Rapid training of all staff as a facilitator to maintain IPC

In a surge response to the COVID-19 pandemic, rapid and intensive training of all nursing home staff on topics related to outbreak prevention and management was carried out in all public, private and voluntary nursing homes. CRTs visited nursing homes regularly to identify gaps in knowledge or practices and provide additional training. Due to the urgent need to train staff, the IPC teams trained the link persons or persons in charge in nursing homes, and these link persons trained the nursing home staff (Quote 1.2.1).

Sub-theme 1.3 New waves, different experiences: improved IPC measures and PPE supply, and the vaccine era

As the pandemic progressed, everyone was learning to provide more effective IPC measures, became more aware of the signs and symptoms of COVID-19 and was able to take prompt and proper actions to contain the source, which significantly reduced the risk of major outbreaks (Quote 1.3.1). Participants highlighted improved access and supply of PPE in the second and third waves of the pandemic to both public and private nursing homes, and PPE provision was streamlined. The protective impact of the COVID-19 vaccination, which began in nursing homes in late December 2020, was described by participants as “a huge difference between pre-and post-vaccination” and that it “had an incredible impact” on the experience of the pandemic in nursing homes for both staff and residents.

Sub-theme 1.4 the need for better outbreak preparedness and more resources

Many participants pointed to an effective and workable contingency plan for outbreak preparedness at organisational and national levels and the need for support through three pillars: a national strategic preparedness plan, a resource base for its implementation, and staff training for the successful implementation of the contingency plan (Quote 1.4.1). Participants also pointed to challenges with developing outbreak contingency plans due to the lack of financial resources allocated to nursing homes. They highlighted that stronger action in the form of legislation was needed to be able to prioritise it. Participants discussed that the private nursing home model is largely a business model; however, finance should not be an issue in providing safe staffing and care (Quote 1.4.2).

Theme 2 - social model of care and the built environment of nursing homes

Sub-theme 2.1 homely environment: contradicting needs

Different views were expressed on homeliness in nursing homes as one of the main features of the social model of care, which addresses older people’s social and emotional needs and wellbeing and the need for stricter adherence to IPC measures during the pandemic. The practice of removing homely items both from communal areas and residents’ rooms for IPC purposes encountered challenges in nursing homes (Quote 2.1.1).

Participants highlighted that smaller facilities with single en-suite rooms had flexibility in responding to infection risk, while larger facilities with multiple room occupancy were considered less manageable for implementing IPC measures. On the other hand, the nursing homes with older buildings, some of which were large houses converted into residential facilities were reported to be at higher risk than newer purpose-built buildings (Quotes 2.1.2 and 2.1.3).

The building design did not allow safe family visits, while window visits were possible only on the ground floor and did not work for residents with dementia. Cohorting residents with dementia was a particular challenge due to their wandering; therefore, safeguarding policies were implemented based on the best interest of residents and the use of the least restrictive options while protecting other residents.

Sub-theme 2.2 staff commitment to IPC and creativity to adapt to change

Participants described how they had to be creative in adapting the guidelines to their daily work to overcome many challenges they faced in managing outbreaks (Quote 2.2.1). Many participants emphasised the role of staff commitment in implementing IPC measures, which was essential for effective outbreak prevention or management despite the limitations of their built environments. Participants were unanimous that the staff behaviours and practices were the most important factors in ensuring appropriate IPC measures are implemented regardless of nursing home conditions, available resources, and the built environment characteristics (Quote 2.2.2).

Sub-theme 2.3 the balance between IPC and residents’ quality of life

Participants viewed the built environment’s role in achieving a balance between infection prevention and control and quality of life of nursing home residents as a critical issue that needs more attention and reconsideration. Given that a lack of space prevented effective outbreak management, participants prioritised creating a built environment with many multipurpose spaces that could be repurposed for IPC measures without affecting residential areas. In addition, the importance of informing the design of future nursing homes and retrofitting the existing ones to be homely and IPC compliant was emphasised (Quote 2.3.1).

Theme 3 – nursing home staffing

Sub-theme 3.1 inadequate staffing levels due to staff on sick leave and absenteeism

Many staff were affected by the COVID-19 infection (Quote 3.1.1). The staff shortage led to “presenteeism”, or attending work despite being ill, as it was perceived as the only way to cope with low staffing levels. Furthermore, to mitigate the effects of high turnover in and crossover of staff members, temporary accommodation was arranged during outbreaks; however, it was reported by several participants as inadequate. Challenges with staffing in remote rural nursing homes and transferring staff to these areas exacerbated staffing shortages (Quote 3.1.2).

Media, at national and international levels, was seen as a contributing factor to some staff quitting or working under stress and fear. Confusing information broadcasted by media sometimes caused trust issues among staff who compared the national guidance with social media content. Often, media reports were viewed as blaming or shaming nursing home staff members, impacting the institutions’ and staff members’ reputations, affecting staff morale, and having financial implications for private nursing homes. Some staff quit due to concerns about their health, fear of bringing infection home, or challenges with finding childcare due to social stigma as they worked in healthcare, especially for international healthcare workers who did not have a family to help with childcare.

Sub-theme 3.2 mutual learning among staff and pandemic preparedness

Despite challenges with staffing levels, many participants highlighted the importance of mutual learning among staff and sharing any information that helped prevent or manage an outbreak among all staff. It also created more confidence in their abilities, relieved anxieties, and gave them a sense of being supported (Quote 3.2.1). Participants acknowledged that raising awareness and promoting open information resources such as HSELand (an online training and development platform for HSE staff), among staff in public, private, and voluntary nursing homes as well as other training initiatives that rolled out during the pandemic, such as Train the Trainer programmes and the IPC Link Practitioner programme, have been very helpful in rapidly upgrading the knowledge and skills of nursing home staff during the pandemic and should be continued in the future (Quote 3.2.2).

Concern was expressed about the lack of communication between emergency services and nursing homes because the work environment of nursing homes was unfamiliar to hospital staff. It was difficult for staff to adjust to new working conditions when they were assigned to work in nursing homes during outbreaks. Participants recommended greater integration between hospitals and residential care services, especially regarding staff mobility and readiness to work in different environments.

Theme 4 – Leadership and staff practices

Sub-theme 4.1 stress and emotional burden of staff

Given the nature of close relationships between caregivers and residents in LTRCFs, there was a significant level of stress and emotional burden among staff due to deaths that occurred in nursing homes during the outbreaks. Dealing with the unknown was a challenge and contributed to fear among staff. Even though they had contingency plans in writing, when there was a confirmed case, implementing the plan was a different experience (Quotes 4.1.1 and 4.1.2).

The senior staff worked under significant pressure and were on frequent conference calls which reduced leadership availability to guide and support staff. Furthermore, low staffing levels put more strain on the remaining staff. Conversely, the psychological effects of working through the challenges of the pandemic impacted the staffing levels. Nevertheless, despite their challenges, staff remained committed to their responsibilities and showed outstanding resilience.

Sub-theme 4.2 good leadership and communication are essential

Effective leadership was referred to as a factor that made a significant difference in staff management and support. Supporting and reassuring staff about their practice and maintaining good communication with them increased staff confidence and motivation, which in turn was perceived as positively affecting outbreak control. Nursing homes that were part of a group were perceived to be more advantageous than single ones in terms of having access to senior staff from other facilities (Quote 4.2.1).

Participants also stated that although nursing home providers strive to provide quality service despite limited resources and difficult circumstances, they need more training on effective leadership and governance specific to this service area (Quote 4.2.2). On the other hand, a suggestion was that all staff members should be reminded about their leadership and knowledge-informed decision-making capacity in the absence of managers due to sick leave. This included training to prepare them for circumstances when they may be required to lead.

Sub-theme 4.3 establishing and maintaining links between teams is key to effective outbreak management

Staff members in different teams worked hard on establishing and maintaining links with each other. Having these already established links was seen as a positive impact of the pandemic, as the teams will benefit from these links if a new pandemic arises (Quote 4.3.1). There was a significant amount of sharing between nursing homes in terms of knowledge and IPC supplies. The networking and communication between institutions were examples of a “we are in this together” approach.

Theme 5 - support and guidance received during the pandemic

Sub-theme 5.1 frequently changing guidelines caused information overload

Although the frequent change in guidelines was necessitated by learning more about the virus and the disease over the new waves and updating the prevention and management strategies accordingly, this “constant change” in guidelines was difficult to follow (Quote 5.1.1). It sometimes undermined trust between line managers and ground staff. Earlier in the pandemic, the changes in new documents were not highlighted; therefore, the persons-in-charge or nurse managers found it difficult to understand what had changed in the most recent guidelines. In addition, confusion was caused by inconsistencies in guidelines issued by different authorities.

Sub-theme 5.2 issues with governance

The role of CRTs to update nursing homes about changes in guidance placed them in the position of the “middleman”. However, their role was at a recommendation level since they did not have governance over the nursing homes (Quote 5.2.1). Nursing homes had multiple lines of reporting; however, lack of communication between these authorities was raised as an issue in multiple interviews. The need for improved regulations to enable monitoring access to IPC training for all nursing homes was highlighted. On the other hand, excessive paperwork required by HIQA was perceived as a challenge when nursing home staff was working under increased pressure to provide necessary care for residents.

Sub-theme 5.3 COVID-19 response teams and other expert support

CRTs maintained regular multidisciplinary team and outbreak control team meetings where every nursing home that required support, irrespective of their public, private or voluntary status, was discussed at length. There were strong links between nursing staff, IPC, and Public Health. The work of CRTs was on a 24/7 basis. In preventing acute hospital admissions, general practitioners, geriatricians, and other expert teams were very accessible, and senior leaders were very approachable. Regular communication and links with CRTs, having a designated person, a clear structure and an open line of communication helped them work together (Quote 5.3.1).

Differences between the supports available for public and private or voluntary nursing homes have been eliminated since the implementation of CRTs, and it is suggested that this remains (Quote 5.3.2). Another key facilitator was the repeated offers of psychological support to staff members, which was essential for staff members, especially for those working under pressure. In addition to the provision of open phone lines, peer support meetings for persons in charge were important factors in helping them cope with the challenges.

Sub-theme 5.4 Access to information and use of technology

Not having access to the most recent version of the guidelines was a barrier to receiving guidance since some nursing homes did not use electronic systems and relied on paper copies of the information (Quote 5.4.1). On the other hand, the use of technology sometimes brought challenges. For example, new staff relocated to nursing homes did not have access to the electronic health system or did not know how to use that system (Quote 5.4.2). As the pandemic progressed, the use of technology evolved, and it played a significant role in the health sector’s response to the pandemic, from diagnostic testing to communication for outbreak management. Participants mentioned several tools, such as video calls, a PPE management system, and the use of tablets by staff and residents.

Discussion

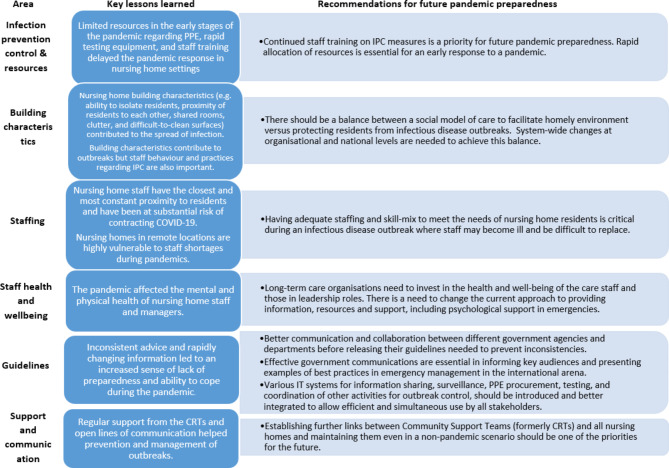

This qualitative study explored barriers and facilitators to managing the COVID-19 outbreaks and reported priority areas for outbreak preparedness in nursing homes in Ireland from the perspective of COVID-19 response teams. The findings presented the key learnings and recommendations under themes related to the IPC challenges, nursing home building characteristics and staffing, leadership and staff practices, as well as support and guidance received by nursing homes during the pandemic. Overall, our findings highlight that the COVID-19 pandemic has tested the preparedness of Irish nursing homes and the wider health and care system, to deal with a crisis that requires effective resource allocation, communication, and coordinated support across different organisations and professional groups. The lessons learnt from this experience and recommendations for future pandemic preparedness are presented below and summarised in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Summary of the key lessons and recommendations for outbreak prevention and management in nursing homes based on the Irish experience of the COVID-19 pandemic in nursing homes

At the onset of the pandemic, nursing homes faced increased challenges with limited resources essential for the care of the most vulnerable population. Irish nursing homes were not alone in these challenges as studies show that, in responding to COVID-19, LTRCFs in other countries faced common challenges that include securing access to PPE and other COVID-19-related medical equipment, early identification of COVID-19 cases and management of disease outbreaks [26–29]. COVID-19 infection manifested differently in older adults compared to the general population [4], which made easy access to testing a key requirement. However, our participants reported delayed recognition of COVID-19 outbreaks due to a lack of rapid on-site antigen tests, and this was also identified as a challenge in the international literature [30–35]. In addition to rapid allocation of resources, adequate and continuous training of nursing home staff for IPC is critical to preventing and controlling outbreaks [36, 37]. In Ireland, as a response to the pandemic, the Infection Prevention and Control Link Practitioner Programme was introduced and implemented [19]. As part of this programme, the link Practitioners act as local resources and role models for their service whilst also being supported by a wider network of IPC experts. The goal of this programme is to have at least one IPC Link Practitioner in every community health and care facility in Ireland [18].

The building characteristics of some nursing homes may act as a barrier to outbreak management. Some participants in our study highlighted that the proximity of residents to each other made it difficult to comply with physical distancing requirements and created difficulties for appropriate IPC practices. Other reports in the literature present similar issues related to staff movement between different sections of these facilities, having one large building instead of small unit facilities, availability of communal areas for residents, poor ventilation, inappropriate facilities for isolation, and overcrowding [38–42]. In pre-COVID-19 times in Ireland, the emphasis was placed on creating a homely environment for residents that made the nursing homes cosy and pleasant. However, with the pandemic requiring stricter adherence to IPC measures, it has become difficult to continue this practice. Existing research supports our finding that indoor characteristics such as clutter and difficult-to-clean surfaces were described as factors contributing to the spread of COVID-19 infection [39–41, 43]. The dilemma of safety versus residents’ quality of life experienced in nursing homes has been reported previously [44]. During the pandemic, direct care staff had to balance restrictive IPC measures and delivering person- or relationship-centred care to maintain residents’ social participation and well-being [45].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Irish nursing homes have been under pressure to maintain already strained staffing levels due to staff sickness and quarantine. The negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on staffing levels were even more pronounced in nursing homes located in remote and rural areas of Ireland, and similar challenges were also experienced in other countries [29, 46, 47]. Most of the barriers to outbreak management reported in the literature were similar to the Irish experience and included staff shortages, lack of paid home isolation periods for staff who tested positive, issues with temporary staff, high turnover rates, lack of policies to support staff, and limited availability of highly-skilled staff due to financial issues [31, 42, 48, 49] On the other hand, some of the solutions to staffing shortage were to allocate budget for additional staff and move additional staff from different service areas [50, 51]. Irish nursing homes were only able to partially offset the loss of staff through the use of overtime of remaining staff, the use of agency staff, and relocation of staff from hospitals and other facilities, which often resulted in staff crossover, thus increasing the risk of transmission of infection between the facilities. Internationally, some studies have reported a correlation between temporary staff and high infection rates [41, 52], and recommendations were made to minimise, where possible, the number of agency staff to control virus transmission [53]. Lack of training for redeployed staff and the failure to consider the skills of redeployed staff for new areas were identified as additional problems [54].

Considering the challenges brought by the pandemic, many staff and managers had little time to prepare for the pandemic. They had to work under significant stress and quickly adapt to changes in the way they worked. Many studies highlight the impact of the pandemic on the employment and the mental health of nursing home staff [55, 56]. Similar to our focus group discussions, international literature reports that staff have faced challenges such as media blame due to high mortality rates among vulnerable older people in LTRCFs [42, 57, 58]. White et al. [58] reported that nursing home workers described the media’s blaming attitude as demoralising. Despite that, the positive aspects of daily work reported by our participants, such as solidarity between colleagues, high commitment, and resilience, were also highlighted in the literature. Sun and colleagues [59] reported good teamwork in nursing teams and “growth under pressure” generated positive emotions during the pandemic.

In the recent global public health crisis, we learned that effective government communication becomes essential for successfully responding to pandemics and stabilising society [60]. As the pandemic rapidly evolved and national guidance required regular updates based on information and guidance from government and public health authorities, Irish nursing homes were expected to quickly accept and understand these updates and ensure all staff were aware of the changes. As in Ireland, information on COVID-19 has been updated frequently in other countries [26, 34, 61] and lack of and inconsistent government guidance was cited as a barrier to controlling and managing COVID-19 infection [62, 63]. To overcome this challenge, effective internal government communication within and between government agencies is essential to ensure messages are well-coordinated to provide the best available information and advice to help combat pandemics [63].

International literature on retrospective outbreak investigations of COVID-19 transmission in long-term care suggests that facility-level leadership, intersectoral and interprofessional collaboration, and policy responses facilitating access to critical resources are all significant enablers of success [64, 65]. Mutual understanding between nursing home leaders and government agencies of changes in nursing home operating conditions throughout the crisis, improving access to additional necessary resources for mitigating the effects of the crisis, and promoting shared responsibility for consistently achieving accepted quality standards in key areas of care are critical [66]. The British Geriatrics Society [67] recommended prioritising decision-making support and adequate resourcing facilities to provide good care in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, implementing international and governmental recommendations requires clear governance and leadership structures in nursing homes, which does not always happen in practice [68]. In Ireland, although there were many nursing homes engaged in comprehensive contingency planning in the event of a COVID-19 outbreak in their facility, the ‘Governance and Management’ regulation had the highest level of non-compliance in compliance assessments conducted by HIQA [9] in April-May 2020, a rate of 5% of facilities were unprepared for a COVID-19 outbreak due to inadequate governance and management. The reasons were a lack of contingency plans for outbreak management and insufficient communication and liaison with local public health officials in their area. Since then, CRTs were in place to support nursing homes; however, the CRTs’ role was at the recommendation level only, since they did not have governance over nursing homes and had no authority to enforce change. This is significant as examples were observed in other countries, such as Australia, where COVID-19 intrusion was more likely in privately owned large-chain nursing homes with a history of regulatory non‐compliance [43]. Meanwhile, in Canada, public LTRCFs were better able to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic than private service providers for several reasons, including the ability to cross-subsidise or attract external resources beyond the base level provided by service contracts [69]. However, there are other reports [70] concluding that, regardless of the nursing home ownership status and the type of governance, the effectiveness in response to the COVID-19 pandemic seems to be mediated by organisational (e.g., facility size and occupancy type), process (e.g., PPE and staff shortages, IPC practices) and contextual factors (e.g., location and community rates of COVID-19 transmission) and these characteristics were more important to consider.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study’s strength is that the focus group interviews were conducted with a diverse group of participants, allowing the breadth of possible responses and gathering rich and comprehensive data. Investigator triangulation was used to diminish bias and to affirm the consistency of findings by having a team of researchers conduct the analysis.

Despite the rigour of data collection and analysis, the descriptive nature of this study and potential recall bias limits the transferability of the study findings. Nonetheless, some findings have been consistent with studies conducted in this setting in other countries. Another limitation is not including frontline staff who provide direct care to residents in nursing homes. However, there was representation from nurse managers and IPC practitioners who had previous experience managing COVID-19 outbreaks in nursing homes at the frontline. Finally, the online data collection via video calls might be a limitation of this study as face-to-face discussions could have allowed more discussions and interactions. Despite that, very rich and comprehensive data was obtained from the lengthy discussions during the online focus group interviews.

Conclusions and implications for practice and policy

This study provides a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the experiences of Irish nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic through the views and experiences of CRT members and other professionals who worked with CRTs. Information from this study contributes to the international literature, which seeks to better understand the challenges encountered by nursing homes in fighting the pandemic, identify barriers and facilitators for effective outbreak management, share key learnings and priority areas for preparedness, and provide recommendations for more effective infection prevention and control processes in LTRCFs in the future.

The experiences of nursing homes in dealing with outbreaks during the COVID-19 pandemic have provided many valuable lessons that will help the sector better prepare for the future. Based on the lessons learned, new, more comprehensive pandemic preparedness plans for nursing homes can be developed, incorporating many changes needed in the long-term residential care sector. Overall, the pandemic has been reported to have caused rapid changes to the Irish healthcare system, many of which typically take a long time to implement. While some factors, such as facility and resident characteristics, cannot be changed in the short term, many factors, such as staff IPC practices and structural changes, were adjusted rapidly. There is great potential to strengthen the long-term care sector’s regulations around essential issues such as staffing levels, nursing home facilities, better support for staff, governance, better use of technology, and IPC and contingency planning, as well as maintaining collaborative relationships and strategic leadership. Furthermore, the regulations should emphasise a person-centred approach to care. Our findings highlight that changes to the system should be continued, and improvements should not be reversed. These changes can and should be made to ensure future pandemic preparedness and improve the quality of care and the overall situation of long-term residential care settings.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all our focus group participants for their valuable contributions to the discussions. We also acknowledge the support of the Heads of the Quality Safety and Service Improvement and Older People Services within each CHO and Public Health Area Directors during the recruitment of participants. We also thank Dr. Maura Dowling for her support in the data analysis process.

Abbreviations

- CHO

Community Health Organisation

- CRTs

Covid-19 Response Teams

- HIQA

Health Information and Quality Authority

- HSE

Health Service Executive

- IPC

Infection prevention and control

- LTRCFs

Long-term residential care facilities

- NPHET

National Public Health Emergency Team

- PPE

Personal Protective Equipment

Author contributions

SD contributed to data collection and analysis and wrote parts of the manuscript. EO contributed to the conceptualisation, design, and manuscript review. DS had the overall responsibility for the study and led the design, ethics approval, recruitment, data collection and analysis, wrote parts of the manuscript and reviewed the whole manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Funding

This work was funded by the Health Service Executive, Ireland. The funder had a role in the conceptualisation of this study since this work was one of the recommendations in the Nursing Homes Expert Panel Report (Recommendation 6.6). The funder did not have any influence in the publication content.

Data availability

Data generated during this study will be retained by the corresponding author for seven years; however, they cannot be shared with any third parties due to the highly sensitive nature of the content.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Research ethics committee approvals were obtained from two independent ethics committees (University of Galway Research Ethics Committee Ref. 2022.06.010, 22 June 2022 and Galway Clinical Research Ethics Committee Ref. C.A.2848, 15 September 2022).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

The participants gave informed consent for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Madhav N, Oppenheim B, Gallivan M, Mulembakani P, Rubin E, Wolfe N. Pandemics: risks, impacts, and mitigation. Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty. 3rd edition. 2017.

- 2.Noji EK. The public health consequences of disasters. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2000;15(4):21–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boamah SA, Weldrick R, Havaei F, Irshad A, Hutchinson A. Experiences of Healthcare Workers in Long-Term Care during COVID-19: a scoping review. J Appl Gerontol. 2023;42(5):1118–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gan JM, Kho J, Akhunbay-Fudge M, Choo HM, Wright M, Batt F, Mandal AK, Chauhan R, Missouris CG. Atypical presentation of COVID-19 in hospitalised older adults. Ir J Med Sci. 2021; 1971-;190:469–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Sanyaolu A, Okorie C, Marinkovic A, Patidar R, Younis K, Desai P, Hosein Z, Padda I, Mangat J, Altaf M. Comorbidity and its impact on patients with COVID-19. SN comprehensive clinical medicine. 2020;2:1069-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Health Protection Surveillance Centre. Monthly Report on COVID-19 Deaths reported in Ireland [Internet]. Ireland, 2022 [cited 2023 Oct 4]. Available from: https://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/respiratory/coronavirus/novelcoronavirus/surveillance/covid-19deathsreportedinireland/COVID-19_Death_Report_Website_v1.7_19-09-2022.pdf-1.4402354

- 7.Quann J. COVID-19: Median age of Irish patients who die reaches 82 [Internet]. Ireland: Newstalk; 2020 [cited 2023 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.newstalk.com/news/covid-19-median-age-irish-patients-82-993305

- 8.Cullen P. Nursing homes account for 50 per cent of coronavirus deaths in Ireland [Internet]. Ireland: The Irish Times, 2020 [cited 2023 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/health/nursing-homes-account-for-50-per-cent-of-coronavirus-deaths-in-ireland-1.4241723

- 9.HIQA. The impact of COVID-19 on nursing homes in Ireland. Health Information and Quality Authority Report; 2020. Available from: https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/files/2020-07/The-impact-of-COVID-19-on-nursing-homes-in-Ireland_0.pdf

- 10.Government of Ireland. National Public Health Emergency Team (NPHET) for COVID-19: Governance Structures [Internet]. Ireland: Newstalk; 2020 [cited 2023 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/78019/cb417ba9-e584-4c12-a164-259521ebf667.pdf#page=null

- 11.Mustafa S, Zhang Y, Zibwowa Z, Seifeldin R, Ako-Egbe L, McDarby G, Kelley E, Saikat S. COVID-19 preparedness and response plans from 106 countries: a review from a health systems resilience perspective. Health Policy Plann. 2022;37(2):255–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Health. COVID-19 Nursing Homes Expert Panel: Final Report [Internet]. Ireland: Government of Ireland; 2020 [cited 2024 Jan 31]. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/3af5a-covid-19-nursing-homes-expert-panel-final-report/

- 13.Government of Ireland. Fourth Progress Report: Implementation of the COVID-19 Nursing Homes Expert Panel Recommendations [Internet]. Ireland: Government of Ireland; 2022 [cited 2024 Jan 31]. https://assets.gov.ie/227614/f7a9d117-b199-4a55-9bce-7750ed230e68.pdf

- 14.Guest G, Namey E, Taylor J, Eley N, McKenna K. Comparing focus groups and individual interviews: findings from a randomized study. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2017;20(6):693–708. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan DL. Focus groups. Annu Rev Sociol. 1996;22:129–52.

- 16.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.HSE. HSE Organisational Structure [Internet], Ireland HSE. 2023 [cited 2023 Nov 24]. https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/

- 18.HSE. Infection prevention & control link practitioner programme framework. [Internet], Ireland HSE. 2020 [cited 2023 Oct 4]. Available from: https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/healthwellbeing/our-priority-programmes/hcai/resources/general/ipc-link-practitioner-programme-framework.pdf

- 19.HSE. COVID-19 Response Teams Operational Guidance [Internet], Ireland HSE. 2020 [cited 2023 Dec 12]. Available from: https://www.pna.ie/images/Covid%20Response%20Teams%20%20Operational%20Guidance%20080420%20(3).pdf

- 20.HSE. Community Healthcare Organisations Finance. [Internet], Ireland HSE. 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/finance/localfinance/communityhealthcareorganisationsfinance/

- 21.Henry, C. CCO HSE Ireland. This week sees the launch of 6 new public health areas. 2022 [cited 2024 Jan 31] [Tweet]. Available from: https://x.com/CcoHse/status/1521426086290198529

- 22.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Res Psychol. 2021;18(3):328–52. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denzin NK. The research act: a theoretical introduction to sociological methods. Transaction; 2017.

- 25.Noble H, Smith J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evidence-based nursing. 2015;18(2):34–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Cofais C, Veillard D, Farges C, Baldeyrou M, Jarno P, Somme D, Corvol A. COVID-19 epidemic: Regional organization centered on nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(10):2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colas A, Baudet A, Regad M, Conrath E, Colombo M, Florentin A. An unprecedented and large-scale support mission to assist residential care facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Prev Pract. 2022;4(3):100234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, et al. The experiences of health- care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e790–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK. Critical supply shortages—the need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGarry BE, Grabowski DC, Barnett ML. Severe staffing and personal protective equipment shortages faced by nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: study examines staffing and personal protective equipment shortages faced by nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff. 2020;39(10):1812–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brainard J, Rushton S, Winters T, Hunter PR. Introduction to and spread of COVID-19-like illness in care homes in Norfolk, UK. J Public Health. 2021;43(2):228–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braun RT, Yun H, Casalino LP, Myslinski Z, Kuwonza FM, Jung HY, Unruh MA. Comparative performance of private equity–owned US nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2026702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lynn J. Playing the cards we are dealt: covid-19 and nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(8):1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meershoek A, Broek L, Crea-Arsenio M. Perspectives from the Netherlands: responses from, strategies of and challenges for long-term care health personnel. Healthc Policy. 2022;17(SP):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Wachholz PA, Jacinto AF. Comment on: Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Geriatrics and Long-Term Care: the ABCDs of COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(6):1168–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aghili MS, Darvishpoor Kakhki A, Gachkar L, Davidson PM. Predictors of contracting COVID-19 in nursing homes: implications for clinical practice. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(9):2799–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al Hamad H, Malkawi MM, Al Ajmi JA, Al-Mutawa MN, Doiphode SH, Sathian B. Investigation of a COVID-19 outbreak and its successful Containment in a Long Term Care Facility in Qatar. Front Public Health. 2021;9:779410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abrams HR, Loomer L, Gandhi A, Grabowski DC. Characteristics of US nursing homes with COVID-19 cases. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(8):1653–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson DC, Grey T, Kennelly S, O’Neill D. Nursing home design and COVID-19: balancing infection control, quality of life, and resilience. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(11):1519–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilbert GL. COVID-19 in a Sydney nursing home: a case study and lessons learnt. Med J Australia. 2020;213(9):393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Longmore M. COVID-19 exposes weaknesses in aged care. Kai Tiaki: Nurs New Z. 2020;26(4):12–3. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frazer K, Mitchell L, Stokes D, Lacey E, Crowley E, Kelleher CC. A rapid systematic review of measures to protect older people in long-term care facilities from COVID-19. BMJ open. 2021;11(10):e047012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ibrahim JE, Li Y, McKee G, Eren H, Brown C, Aitken G, Pham T. Characteristics of nursing homes associated with COVID-19 outbreaks and mortality among residents in Victoria, Australia. Australas J Ageing. 2021;40(3):283–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Preshaw DH, Brazil K, McLaughlin D, Frolic A. Ethical issues experienced by healthcare workers in nursing homes: literature review. Nurs Ethics. 2016;23(5):490–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dichter MN, Sander M, Seismann-Petersen S, Köpke S. COVID-19: it is time to balance infection management and person-centered care to maintain mental health of people living in German nursing homes. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32(10):1157–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aïdoud A, Poupin P, Gana W, Nkodo JA, Debacq C, Dubnitskiy-Robin S, Fougère B. Helping nursing homes to manage the COVID‐19 crisis: an illustrative example from France. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(11):2475–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang BK, Carter MW, Nelson HW. Trends in COVID-19 cases, deaths, and staffing shortages in US nursing homes by rural and urban status. Geriatr Nurs. 2021;42(6):1356–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pillemer K, Subramanian L, Hupert N. The importance of long-term care populations in models of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(1):25–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gopal R, Han X, Yaraghi N. Compress the curve: a cross-sectional study of variations in COVID-19 infections across California nursing homes. BMJ open. 2021;11(1):e042804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boltz M. Long-term care and the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned. Nurs Clin. 2023;58(1):35–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eichner L, Schlegel C, Roller G, Fischer H, Gerdes R, Sauerbrey F, Schönleber S, Weinhart F, Eichner M. COVID-19 case findings and contact tracing in south German nursing homes. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Green R, Tulloch JS, Tunnah C, Coffey E, Lawrenson K, Fox A, Mason J, Barnett R, Constantine A, Shepherd W, Ashton M. COVID-19 testing in outbreak-free care homes: what are the public health benefits? J Hosp Infect. 2021;111:89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shallcross L, Burke D, Abbott O, Donaldson A, Hallatt G, Hayward A, Thorne S. Factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection and outbreaks in long-term care facilities in England: a national cross-sectional survey. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2(3):e129–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vindrola-Padros C, Andrews L, Dowrick A, Djellouli N, Fillmore H, Gonzalez EB, Javadi D, Lewis-Jackson S, Manby L, Mitchinson L, Symmons SM. Perceptions and experiences of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. BMJ open. 2020;10(11):e040503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Halcomb E, McInnes S, Williams A, Ashley C, James S, Fernandez R, Stephen C, Calma K. The experiences of primary healthcare nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52(5):553–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spoorthy MS, Pratapa SK, Mahant S. Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic–A review. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;51:102119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Powell T, Bellin E, Ehrlich AR. Older adults and Covid-19: the most vulnerable, the hardest hit. Hastings Cent Rep. 2020;50(3):61–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.White EM, Wetle TF, Reddy A, Baier RR. Front-line nursing home staff experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(1):199–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun N, Wei L, Shi S, et al. A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:592–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang PH. Pandemic emotions: The good, the bad, and the unconscious-implications for public health, financial economics, law, and leadership. Nw. JL & Soc. Pol’y. 2020;16:81.

- 61.Baughman AW, Renton M, Wehbi NK, Sheehan EJ, Gregorio TM, Yurkofsky M, Levine S, Jackson V, Pu CT, Lipsitz LA. Building community and resilience in Massachusetts nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(10):2716–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cowan H. Care home nursing during COVID-19. Br J Cardiac Nurs. 2020;15(8):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim DK, Kreps GL. An analysis of government communication in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations for effective government health risk communication. World Med Health Policy. 2020;12(4):398–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dykgraaf SH, Matenge S, Desborough J, Sturgiss E, Dut G, Roberts L, McMillan A, Kidd M. Protecting nursing homes and long-term care facilities from COVID-19: a rapid review of international evidence. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(10):1969–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schot E, Tummers L, Noordegraaf M. Working on working together. A systematic review on how healthcare professionals contribute to interprofessional collaboration. J Interprof Care. 2020;34(3):332–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Behrens LL, Naylor MD. We are alone in this battle: a framework for a coordinated response to COVID-19 in nursing homes. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020;32(4–5):316–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.British Geriatrics Society. Managing the COVID-19 pandemic in care homes [Internet]. London: British Geriatrics Society. 2020 [cited 2023 Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.bgs.org.uk/resources/covid-19-managing-the-covid-19pandemic-in-care-homes

- 68.Fallon A, Dukelow T, Kennelly SP, O’Neill D. COVID-19 in nursing homes. QJM: Int J Med. 2020;113(6):391–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pue K, Westlake D, Jansen A. Does the profit motive matter? COVID-19 prevention and management in Ontario long-term-care homes. Can Public Policy. 2021;47(3):421–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kruse FM, Mah JC, Metsemakers SJ, Andrew MK, Sinha SK, Jeurissen PP. Relationship between the ownership status of nursing homes and their outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid literature review. J Long-Term Care. 2021 Jul 8.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data generated during this study will be retained by the corresponding author for seven years; however, they cannot be shared with any third parties due to the highly sensitive nature of the content.