Abstract

Background

We aimed to develop risk tools for dementia, stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), and diabetes, for adults aged ≥ 65 years using shared risk factors.

Methods

Data were obtained from 10 population-based cohorts (N = 41,755) with median follow-up time (years) for dementia, stroke, MI, and diabetes of 6.2, 7.0, 6.8, and 7.4, respectively. Disease-free participants at baseline were included, and 22 risk factors (sociodemographic, medical, lifestyle, laboratory biomarkers) were evaluated. Two risk tools (DemNCD and DemNCD-LR based on Fine and Gray sub-distribution and logistic regression [LR], respectively) were developed and validated. Predictive accuracies of these risk tools were assessed using Harrel’s C-statistics and area under the curve (AUC) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Model calibration was conducted using Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit test along calibration plots.

Results

Both the DemNCD and DemNCD-LR resulted in similar predictive accuracy for each outcome. The overall AUC (95% CI) for dementia, stroke, MI, and diabetes risk tool were 0·68 (0·65, 0·70), 0·58 (0·54, 0·61), 0·65 (0·61, 0·68), and 0·68 (0·64, 0·72), respectively, for males. For females, these figures were 0·65 (0·63, 0·67), 0·55 (0·52, 0·57), 0·65 (0·62, 0·68), and 0·61 (0·57, 0·65).

Conclusions

The DemNCD is the first tool to predict both dementia and multiple cardio-metabolic diseases using comprehensive risk factors and provided similar predictive accuracy to existing risk tools. It has similar predictive accuracy as tools designed for single outcomes in this age-group. DemNCD has the potential to be used in community and clinical settings as it includes self-reported and routinely available clinical measures.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12916-024-03711-6.

Keywords: Risk factors, Risk tool, Primary prevention, Dementia, Stroke, Diabetes, Heart attack, Risk prediction

Background

Dementia is a global health problem, currently affecting over 55 million people worldwide, two thirds of whom reside in low- and middle-income countries and risk reduction is a key public health priority [1, 2]. Cardiometabolic disease, e.g., stroke, myocardial infarction, and diabetes, are strong independent risk factors for dementia [3–6]. A recent study has reported that dementia risk associated with high cardio-metabolic multimorbidity was three time greater than that associated with genetic risk [3]. Moreover, researchers have identified key modifiable risk factors for dementia [4, 7] including physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, excessive alcohol intake, smoking, hypertension, high cholesterol, obesity, sleep problems, and depression, which are also shared with these non communicable diseases (NCDs) among older adults in varying degree with each gender [8]. Therefore, dementia prevention strategies are now focused on prevention of these cardiometabolic disease to achieve maximum benefit [2, 4].

Validated risk factor assessment tools play a cruicial role in raising awareness of risk factors for chronic disease. They may allow for the early identification of high-risk individuals and population groups and guide health professionals’ recommendations for interventions to improve lifestyle habits. Although several independent risk tools for dementia [9–11], stroke [12–14], MI [15–17], and diabetes [18] have been developed, recent studies have explored the potential of cardiovarascular risk tools in predicting dementia [19, 20]. This is based on evidence that vascular risk factors consistently linked to cognitive decline [21]. However, such approach may not incorporate all the modifiable risk factors of dementia identified by the recent Lancet commission report [4].

Additionally, awareness of the shared risk factors between dementia and NCDs among general population remains low [22, 23]. Therefore, a unified risk assessment tool that incorporates modifiable risk factors for these NCDs would be efficient in increasing risk awareness and more cost effective than assessing risks for each individual NCD [24]. Such a tool could better support clinicians in their efforts at health promotion by showing the pleiotropic benefits of lifestyle changes on patients’ health. A recent report also indicated a positive views among general practionner in adopting such tool in their practices [25]. It may guide policy-makers in their development of population-based prevention strategies.

We aimed to develop a new risk prediction tool called “DemNCD” (Dementia and other NCDs) to predict the risks of dementia, stroke, diabetes, and MI in older adults (age ≥ 65 years) using a broad range of shared risk factors. DemNCD was derived from analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies (to provide sufficient sample size) that measured risk factors for the four outcomes of interest and incident disease during follow-up.

Methods

Data and participants

Data were obtained from prospective population-based cohorts identified through searches of consortia websites, databases, and consultation with experts. Details of the study methods and procedures are described elsewhere [26]. Briefly, 10 cohorts were selected based on the availability of a clinical diagnosis of dementia and other NCDs, risk factors, length of follow-up time, sample size, and availability of data from the study custodians. The cohorts included the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) [27], the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) [28], the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) [29], the MRC Cognitive function and Ageing Studies (both MRC CFAS-I and CFAS-II) [30, 31], the Sydney Memory and Aging Study (MAS) [32], the Maastricht Aging Study (MAAS) [33], the Health and Retirement Study-Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (HRS ADAMS) [34], the RUSH Memory and Aging project (MAP) [35], and the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study-I (SLAS-I) [36]. Additional file 1: Section S1 describes each study, including study recruitment and longitudinal timelines. Additional details on the selection of studies are also available in the DemNCD protocol paper [26]. The baseline age distribution varied across the studies with CHS, CFAS I, and CFAS II including data only for adults aged 65 and above. Therefore, we included participants who were aged ≥ 65 years at inception or time of first assessment for dementia and other NCDs. We therefore considered subsets of these cohorts with participants aged ≥ 65 years for analysis. Covariates from each dataset were harmonized to allow merging. In the pooled sample, 41,755 older participants were available from 10 cohorts for analysis.

Outcomes

The outcomes for the risk prediction model included diabetes, stroke, MI, and dementia. Dementia was diagnosed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria (DSM-III-R, IV) or other well-established criteria that included the Mental State − Automated Geriatric Examination for Computer Assisted Taxonomy (GMS-AGECAT), criteria of National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke, and the Alzheimer’s disease and Related Disorders Association. For diabetes, stroke, and MI, a clinical diagnosis was preferred but otherwise a self-reported diagnosis was used (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Predictors

We used a four-stage process to select predictors (see Additional file 1: Fig. S1). Stage I included selecting potential predictors from the latest comprehensive systematic reviews [7, 37–43], Lancet Commissions [1, 44], and WHO Guidelines [2]. Stage II comprised additional predictors identified from existing published risk tools for each outcome [12, 45–51]. At stage III, all predictors identified in the previous two stages were reviewed and ranked independently by subject matter experts into order of importance (see [26]). Finally, all the identified predictors were checked for availability in the datasets (Additional file 1: Table S2). Overall, 22 demographic (age, sex, and education), medical (self-reported high blood pressure, depression, obesity using measured body mass index (BMI), atrial fibrillation (AF), total cholesterol and both high- and low-density lipoprotein, traumatic brain injury (TBI), left ventricular hypertrophy, chronic kidney disease and hearing loss), and lifestyle (cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, weekly fruit and vegetable intake, fish intake, loneliness, low cognitive engagement, sleep problems and physical inactivity) predictors were selected based on their availability in the cohort datasets. Left ventricular hypertrophy and chronic kidney disease were excluded from the analysis due to their unavailability in most (≥ 7) of the datasets. Additional file 1: Table S3 reports definitions of the covariates used in the data harmonization. Selection of predictors was primarily based on routinely collected information, focusing on data readily available to clinicians and individuals, that provide ready targets for intervention. As a result, biomarkers that are rarely available (e.g., APOE e4) were not included.

Statistical analysis

The pooled dataset was randomly split into two parts using 65:35 ratios for development (model data) and validation data. Proportionate representation of age, sex, and study cohort was ensured in the development and validation samples. In the model dataset, a large amount of missing data was observed due to complete non-response (absence of variables) and partial missingness. Multivariate normal multiple imputation was used to impute missing values in the model dataset. Cohort-specific indicator variables along with all the outcomes and covariates in the analysis models were used as covariates in the imputation model. Twenty imputed datasets were considered in the model dataset based on von Hippel et al. guidelines [52]. Following imputation, the Fine and Gray sub-distribution model was used [53] to regress the sub-distribution hazards of respective outcomes to the model data according to the following models:

with death as competing event to the imputed datasets stratified by cohorts and sex, where X = (age, education, obesity, alcohol consumption, smoking, hypertension, cholesterol, high- and low-density lipoprotein, depression, fish serve, fruits and vegetable intake, TBI, loneliness, insufficient physical activity, AF, sleep problems, hearing loss). We also included cognitive engagement as a covariate for the dementia outcome. Only individuals with known incident outcome status were included in the model.

For each sex, the resultant cohort-specific regression coefficients were then combined using Rubin’s rule [54]. These sex and cohort specific regression coefficients for each of the risk factors were further aggregated across different cohorts through random-effects meta-analysis. In this step, regression coefficients of the covariates were only included in the meta-analysis if covariate information were available for a given cohort. This restriction was imposed to avoid an influence of large cohorts on the imputed values of non-response variables. The final regression coefficients were then converted to obtain point-based scoring algorithms for each sex and outcome [55]. The sex-specific point-based risk scores were then validated using the validation sample. The accuracy of the risk scores for identifying participants at risk of dementia and other outcomes were quantified by calculating the Harrel’C statistics [56] and associated 95% CIs. Cut-off values (quantile ranks) for the risk scores were compared relative to sub-distribution hazards ratios and for sensitivity and specificity.

We also calculated risk scores from the cohorts under consideration using logistic regression models as a sensitivity analysis in order to obtain the impact of missing event time where outcome status were available. In this case, we modeled binary outcomes with the same predictors and methodology as of the above survival analysis. The risk score was then calculated using the methodology described above. The resulting risk score was also validated using the validation sample. Model calibration was conducted using Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit test along calibration plots [57]. The performance of the risk scores for identifying participants at risk of dementia and other outcomes was quantified by calculating the area under the curves (AUCs) and associated 95% CIs. For a given cut-off (quantile ranks) of the risk scores, we also compared relative odds ratios, sensitivity, and specificity. We validated each of these risk scores to include results for a model including only age, to examine whether the addition of other variables improved prediction.

Results

Description of the study dataset

Additional file 1: Table S2 presents covariates and outcome distribution in the study datasets. There was heterogeneity in sample size, profile of conditions/covariates, and outcomes across the datasets. Table 1 shows the distributions of outcomes and covariates in the model development (n = 27,162) and validation (n = 14,613) samples. The distribution of covariates in the model development and validation samples are similar. The mean age of study participants was 75·3 (6·8) years and 42% were male. Nearly a third of the study sample had a tertiary level of education. Median follow-up times (in years) for dementia, stroke, MI, and diabetes were 6.2, 7.0, 6.8, and 7.4, repectively. The major medical risk factors across cohorts were hypertension (47%), obesity (29.5%), hearing loss (15%), sleep problems (10%), TBI (9%), depression (9%), high total cholesterol (9%), and AF (6%). In terms of behavioral risk factors, 12% reported being a current smoker, 8% as heavy drinkers, and approximately 12% were engaged in moderate to high cognitive activities. A large proportion of covariates had missing data due to complete non-response of covariates. Nearly, 11%, 8%, 6%, and 4% of the pooled sample was diagnosed with incident dementia, stroke, MI, and diabetes, respectively. Around two thirds of the study participants died during follow-up. Among the cohorts, HRS ADAMS had only a few cases of incident diabetes (n = 19), MI (n = 4), and stroke (n = 15), MAAS had lowest number of incident strokes recorded (n = 3), and the Sydney Memory and Ageing Study had lowest number of incident diabetes cases (n = 17). All the cohorts had ample number of dementia cases (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Table 1.

Study characteristics of the validation and development sample

| Combined sample | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Development sample n = 27,162 (%) |

Validation sample n = 14,613 (%) |

|

| Cohorts | ||

| Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study | 3854 (14·2) | 2076 (14·2) |

| Cognitive function and Ageing Study-I (CFAS-I) | 8453 (31·1) | 4551 (31·1) |

| Cognitive function and Ageing Study-II (CFAS-II) | 5047 (18·6) | 2715 (18·6) |

| The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) | 3830 (14·1) | 2058 (14·1) |

| The Framingham Heart Study (FHS) | 2138 (7·9) | 1150 (7·9) |

| Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) | 1375 (5·1) | 737 (5·0) |

| The Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Studies (SLAS-I) | 915 (3·4) | 492 (3·4) |

| Sydney Memory and Aging Study (MAS) | 676 (2·5) | 361 (2·5) |

| HRS- Aging, Demographics and Memory Study (HRS-ADAMS) | 557 (2·1) | 299 (2·1) |

| Maastricht Aging Study (MAAS) | 317 (1·2) | 174 (1·2) |

| Covariates | ||

| Age group (in years) | ||

| 65–69 | 6385 (23·5) | 3439 (23·5) |

| 70–74 | 7204 (26·5) | 3875 (26·5) |

| 75–79 | 6206 (22·8) | 3342 (22·9) |

| 80–84 | 4541 (16·7) | 2445 (16·7) |

| 85–89 | 2145 (7·9) | 1151 (7·9) |

| 90 + | 681 (2·5) | 361 (2·5) |

| Age (mean, SD) | M = 75·3, SD = 6·8 | M = 75·3, SD = 6·8 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 11,300 (41·6) | 6079 (41·6) |

| Education | ||

| Primary | 3672 (13·5) | 2038 (13·9) |

| Secondary | 13,916 (51·2) | 7485 (51·2) |

| Tertiary | 9164 (33·7) | 4865 (33·3) |

| Missing | 410 (1·5) | 225 (1·5) |

| Obesity | ||

| Under weight | 235 (0·9) | 146 (1·0) |

| Normal weight | 4389 (16·2) | 2373 (16·2) |

| Overweight | 5102 (18·8) | 2705 (18·5) |

| Obese | 2955 (10·9) | 1565 (10·7) |

| Missing | 14,481 (53·3) | 7824 (53·5) |

| Smoking history | ||

| Never | 11,193 (41·2) | 5964 (40·8) |

| Former | 11,960 (44·0) | 6466 (44·2) |

| Current | 3118 (11·5) | 1690 (11·6) |

| Missing | 891 (3·3) | 493 (3·4) |

| High blood pressure | ||

| Yes | 12,807 (47·2) | 6962 (47·6) |

| Missing | 540 (2·0) | 280 (1·9) |

| Physical activity | ||

| Less than sufficient | 3294 (12·1) | 1834 (12·6) |

| Sufficient | 6827 (25·1) | 3592 (24·6) |

| Missing | 17,041 (62·7) | 9187 (62·9) |

| High total cholesterol | ||

| Yes | 2357 (8·7) | 1273 (8·7) |

| Missing | 15,154 (55·8) | 8184 (56·0) |

| High-density lipoprotein | ||

| High | 6183 (22·8) | 3311 (22·7) |

| Missing | 17,886 (65·8) | 9634 (65·9) |

| Low-density lipoprotein | ||

| High | 1121 (4·1) | 615 (4·2) |

| Missing | 17,710 (65·2) | 9535 (65·3) |

| Traumatic brain injury | ||

| Yes | 2502 (9·2) | 1367 (9·4) |

| Missing | 7271 (26·8) | 3942 (27·0) |

| Depression | ||

| Yes | 2410 (8·9) | 1325 (9·1) |

| Missing | 2418 (8·9) | 1305 (8·9) |

| Alcohol consumption | ||

| Abstain | 7537 (27·7) | 3995 (27·3) |

| Moderate | 6769 (24·9) | 3667 (25·1) |

| Heavy | 2054 (7·6) | 1161 (7·9) |

| Missing | 10,802 (39·8) | 5790 (39·6) |

| Fruits and vegetable | ||

| ≥ 5 servings/week | 8830 (32·5) | 4707 (32·2) |

| Missing | 16,736 (61·6) | 9023 (61·7) |

| Fish intake | ||

| ≥ 2 servings/week | 5861 (21·6) | 3144 (21·5) |

| Missing | 14,380 (52·9) | 7813 (53·5) |

| Cognitive engagement | ||

| Low | 5138 (18·9) | 2809 (19·2) |

| Moderate | 1662 (6·1) | 878 (6) |

| High | 1508 (5·6) | 771 (5·3) |

| Missing | 18,854 (69·4) | 10,155 (69·5) |

| Loneliness | ||

| Yes | 875 (3·2) | 483 (3·3) |

| Missing | 14,075 (51·8) | 7573 (51·8) |

| Atrial fibrillation | ||

| Yes | 1662 (6·1) | 897 (6·1) |

| Missing | 16,467 (60·6) | 8856 (60·6) |

| Hearing loss | ||

| Yes | 4092 (15·1) | 2130 (14·6) |

| Missing | 4267 (15·7) | 2298 (15·7) |

| Sleep problem | ||

| Yes | 2795 (10·3) | 1504 (10·3) |

| Missing | 13,154 (48·4) | 7086 (48·5) |

| Outcomes | ||

| Diabetes | ||

| Incident | 1145 (4·2) | 591 (4·0) |

| Prevalent | 3737 (13·8) | 2029 (13·9) |

| Missing | 322 (1·2) | 172 (1·2) |

| Stroke | ||

| Incident | 2146 (7·9) | 1083 (7·4) |

| Prevalent | 1720 (6·3) | 955 (6·5) |

| Missing | 273 (1·0) | 161 (1·1) |

| MI | ||

| Incident | 1701 (6·3) | 928 (6·4) |

| Prevalent | 2509 (9·2) | 1389 (9·5) |

| Missing | 357 (1·3) | 191 (1·3) |

| Dementia | ||

| Incident | 2931 (10·8) | 1575 (10·8) |

| Prevalent | 928 (3·4) | 480 (3·3) |

| Missing | 2623 (9·7) | 1429 (9·8) |

| Death | 18,127 (66·7) | 9820 (67·2) |

Definition of covariates and outcome are provided in Additional file 1: Table S1 and Table S3, respectively

Development of DemNCD risk tools

Table 2 reports the combined regression coefficients estimated in meta-analysis of parameters from the Fine and Gray sub-distribution model for dementia, stroke, MI, and diabetes, for males and females. In the dementia model, higher age, lower than tertiary education, insufficient physical activity, hearing loss, and stroke were significantly associated with increased dementia risk. For females, higher age, depression, loneliness, and stroke were significantly associated with increased dementia risk, whereas high cognitive activity, late-life obesity/overweight, late-life moderate to high alcohol consumption, and sleep problems were significantly associated with a lower dementia risk.

Table 2.

Sub-distribution hazards regression coefficients for individual risk/protective factors (β, 95% CI) obtained through meta-analysis following Fine and Gray sub-distribution hazards model

| Covariates | Dementia | Stroke | MI | diabetes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Age | ||||||||

| 65–69 | − 0·38 (− 0·71, − 0·05) | − 0·47 (− 0·77, − 0·16) | − 0·12 (− 0·34, 0·11) | − 0·00 (− 0·22, 0·21) | 0·14 (− 0·09, 0·36) | 0·10 (− 0·13, 0·34) | 0·24 (− 0·12, 0·61) | 0·15 (− 0·08, 0·38) |

| 70–74 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 75–79 | 0·54 (0·33, 0·75) | 0·39 (0·14, 0·64) | 0·08 (− 0·15, 0·31) | 0·20 (0·02, 0·38) | 0·17 (− 0·07, 0·41) | 0·14 (− 0·08, 0·35) | 0·06 (− 0·24, 0·36) | − 0·27 (− 0·53, − 0·01) |

| 80–84 | 0·77 (0·44, 1·10) | 0·92 (0·49, 1·35) | 0·22 (− 0·03, 0·47) | 0·09 (− 0·31, 0·50) | 0·14(− 0·33, 0·61) | 0·07 (− 0·20, 0·34) | − 0·38 (− 0·93, 0·17) | − 0·47 (− 0·82, − 0·12) |

| 85–89 | 1·27 (0·94, 1·60) | 1·18 (0·52, 1·85) | − 0·25 (− 0·72, 0·23) | − 0·00(− 0·50, 0·49) | − 0·09 (− 0·98, 0·80) | − 0·02 (− 0·43, 0·39) | − 0·37 (− 1·15, 0·40) | − 1·03 (− 1·69, − 0·37) |

| 90 + | 2·45 (1·52, 3·39) | 1·60 (0·92, 2·28) | − 0·31 (− 1·63, 1·01) | − 0·74 (− 1·76, 0·29) | 0·43 (− 0·62, 1·49) | − 0·08 (− 1·20, 1·05) | * | * |

| Education | ||||||||

| Less than secondary | 0·35 (0·10, 0·60) | 0·14 (− 0·06, 0·33) | − 0·03 (− 0·29, 0·24) | 0·18 (− 0·02, 0·39) | 0·00 (− 0·26, 0·26) | 0·20 (− 0·17, 0·57) | 0·05 (− 0·32, 0·43 | 0·49 (0·18, 0·79) |

| Upper secondary | 0·22 (0·02, 0·42) | 0·10 (− 0·05, 0·25) | 0·05 (− 0·16, 0·27) | 0·08 (− 0·11, 0·27) | − 0·08 (− 0·45, 0·29) | 0·27 (0·06, 0·48) | 0·05 (− 0·25, 0·34) | 0·26 (0·00, 0·51) |

| Tertiary | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Obesity | ||||||||

| Underweight | 0·55 (− 0·36, 1·47) | 0·09 (− 0·39, 0·56) | − 0·03 (− 1·15, 1·09) | − 0·28 (− 0·84, 0·29) | 0·58 (− 0·53, 1·69) | − 0·07 (− 0·75, 0·61) | * | − 0·51 (− 1·68, 0·67) |

| Normal | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Overweight | − 0·01 (− 0·21, 0·20) | − 0·15 (− 0·29, − 0·00) | 0·11 (− 0·11, 0·32) | − 0·09 (− 0·25, 0·07) | 0·24 (0·03, 0·45) | 0·16 (− 0·05, 0·36) | 0·59 (0·19, 0·99) | 0·19 (− 0·06, 0·44) |

| Obese | 0·06 (− 0·22, 0·34) | − 0·32 (− 0·52, − 0·13) | 0·04 (− 0·26, 0·33) | − 0·20 (− 0·40, − 0·01) | 0·19 (− 0·24, 0·63) | 0·22 (− 0·18, 0·62) | 0·98 (0·59, 1·37) | 0·89 (0·55, 1·24) |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||

| Low | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Moderate | − 0·23 (− 0·45, − 0·00) | − 0·28 (− 0·46, − 0·10) | 0·12 (− 0·12, 0·35) | − 0·04 (− 0·21 0·13) | 0·09 (− 0·12, 0·30) | − 0·00 (− 0·27, 0·27) | − 0·19 (− 0·47, 0·08) | − 0·29 (− 0·56, − 0·03) |

| High | − 0·06 (− 0·38, 0·26) | − 0·47 (− 0·89, − 0·05) | 0·15 (− 0·18, 0·48) | − 0·15 (− 0·56, 0·26) | 0·02 (− 0·32, 0·37) | 0·46 (− 0·89, 1·80) | − 0·05 (− 0·49, 0·39) | − 0·66 (− 1·41, 0·09) |

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Non-smoker | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Current smoker | − 0·14 (− 0·31, 0·04) | − 0·12 (− 0·28, 0·03) | − 0·07 (− 0·31, 0·16) | − 0·12 (− 0·27, 0·02) | 0·14 (− 0·06, 0·33) | 0·07 (− 0·10, 0·24) | 0·05 (− 0·20, 0·31) | 0·13 (− 0·07, 0·34) |

| Former smoker | − 0·02 (− 0·32, 0·29) | 0·21 (− 0·04, 0·45) | − 0·13 (− 0·57, 0·31) | 0·14 (− 0·20, 0·48) | − 0·10 (− 0·69, 0·49) | − 0·10 (− 0·40, 0·20) | 0·14 (− 0·29, 0·57) | 0·38 (0·08, 0·69) |

| Hypertension (yes) | − 0·01 (− 0·18, 0·17) | − 0·05 (− 0·21, 0·11) | 0·19 (0·01, 0·36) | 0·26 (0·06, 0·46) | 0·07 (− 0·11, 0·25) | 0·19 (0·02, 0·36) | 0·19 (− 0·05, 0·42) | 0·28 (0·09, 0·48) |

| Cholesterol (high) | 0·19 (− 0·27, 0·66) | 0·24 (− 0·01, 0·48) | 0·28 (− 0·11, 0·66) | − 0·11 (− 0·36, 0·15) | − 0·14 (− 0·58, 0·30) | 0·04 (− 0·26, 0·34) | 0·32 (− 0·28, 0·92) | − 0·23 (− 0·60, 0·14) |

| High HDL | 0·13 (− 0·10, 0·36) | − 0·13 (− 0·30, 0·05) | − 0·18 (− 0·38, 0·02) | − 0·16 (− 0·31, − 0·00) | − 0·05 (− 0·25, 0·15) | − 0·12 (− 0·30, 0·06) | − 0·22 (− 0·50, 0·07) | − 0·29 (− 0·52, − 0·06) |

| High LDL | 0·08 (− 0·49, 0·65) | − 0·26 (− 0·62, 0·09) | 0·07 (− 0·64, 0·78) | 0·37 (− 0·22, 0·96) | 0·34 (− 0·11, 0·79) | 0·07 (− 0·29, 0·43) | − 0·39 (− 1·04, 0·25) | − 0·14 (− 0·58, 0·29) |

| Depression (yes) | − 0·09 (− 0·41, 0·23) | 0·21 (0·00, 0·42) | 0·33 (− 0·11, 0·77) | 0·00 (− 0·23, 0·23) | 0·23 (− 0·14, 0·60) | − 0·03 (− 0·27, 0·22) | − 0·07 (− 0·53, 0·39) | 0·17 (− 0·10, 0·44) |

| Fish serve | 0·09 (− 0·11, 0·30) | 0·00 (− 0·15, 0·15) | − 0·02 (− 0·21, 0·17) | 0·02 (− 0·13, 0·18) | − 0·03 (− 0·22, 0·16) | − 0·06 (− 0·24, 0·12) | 0·02 (− 0·25, 0·29) | 0·07 (− 0·16, 0·30) |

| Fruits and vegetable | − 0·02 (− 0·38, 0·34) | − 0·20 (− 0·55, 0·14) | − 0·30 (− 0·76, 0·17) | − 0·20 (− 0·65, 0·26) | 0·55 (− 0·08, 1·17) | 0·11 (− 0·45, 0·66) | 0·03 (− 0·58, 0·64) | 0·22 (− 0·51, 0·95) |

| TBI (yes) | 0·00 (− 0·22, 0·22) | − 0·03 (− 0·26, 0·19) | 0·09 (− 0·20, 0·38) | 0·32 (0·03, 0·61) | 0·04 (− 0·31, 0·40) | − 0·31 (− 0·77, 0·14) | − 0·02 (− 0·48, 0·43) | 0·21 (− 0·18, 0·61) |

| Loneliness (yes) | 0·22 (− 0·26, 0·70) | 0·44 (0·10, 0·44) | 0·26 (− 0·21, 0·73) | − 0·01 (− 0·31, 0·28) | 0·24 (− 0·23, 0·71) | 0·03(− 0·33, 0·38) | − 0·09 (− 0·86, 0·69) | 0·14 (− 0·27, 0·55) |

| Insufficient physical activity | 0·28 (0·06, 0·49) | 0·08 (− 0·09, 0·24) | − 0·02 (− 0·41, 0·37) | − 0·03 (− 0·26, 0·20) | 0·07 (− 0·44, 0·59) | 0·12 (− 0·06, 0·30) | − 0·11 (− 0·42, 0·19) | − 0·03 (− 0·31, 0·24) |

| Cognitive activity | ||||||||

| Low | Ref | Ref | Not included | Not included | Not included | |||

| Moderate | 0·06 (− 0·48, 0·59) | − 0·03 (− 0·33, 0·27) | ||||||

| High | − 0·63 (− 1·35, 0·09) | − 0·40 (− 0·80, − 0·01) | ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0·14 (− 0·10, 0·38) | 0·12 (− 0·08, 0·32) | 0·25 (− 0·01, 0·52) | 0·34 (0·09, 0·59) | 0·37 (− 0·31, 1·06) | 0·45 (0·10, 0·80) | − 0·02 (− 0·40, 0·36) | 0·01 (− 0·33, 0·36) |

| Sleep problem | 0·00 (− 0·47, 0·47) | − 0·23 (− 0·43, − 0·03) | 0·26 (− 0·14, 0·65) | − 0·10 (− 0·28, 0·09) | 0·50 (− 0·26, 1·25) | 0·13 (− 0·09, 0·34) | 0·14 (− 0·29, 0·57) | − 0·12 (− 0·40, 0·16) |

| Hearing loss | 0·22 (0·03, 0·41) | − 0·00 (− 0·17, 0·17) | 0·01 (− 0·23, 0·26) | 0·12 (− 0·09, 0·34) | − 0·12 (− 0·46, 0·22) | 0·17 (− 0·10, 0·44) | 0·04 (− 0·30, 0·38) | 0·21 (− 0·12, 0·53) |

| Diabetes | 0·02 (− 0·17, 0·20) | 0·04 (− 0·11, 0·19) | 0·15 (− 0·07, 0·36) | 0·14 (− 0·03, 0·31) | 0·23 (0·04, 0·43) | 0·32 (0·15, 0·50) | Not included | |

| Stroke | 0·65 (0·48, 0·83) | 0·41 (0·24, 0·59) | Not included | 0·13 (− 0·08, 0·34) | 0·35 (− 0·14, 0·83) | |||

| MI | − 0·21 (− 0·52, 0·09) | − 0·08 (− 0·26, 0·11) | 0·13 (− 0·05, 0·32) | 0·22 (− 0·03, 0·40) | Not included | |||

In the stroke model, only hypertension was associated with increased risk for males. For females, hypertension, obesity, and high HDL were associated with decreased risk of stroke, whereas having had TBI and AF both were significantly associated with increased stroke risk.

In the MI model, previous history of diabetes was significantly associated with MI for both sexes. Among other medical covariates, hypertension, and AF, both were significantly associated with increased MI risk for females.

In the diabetes model, overweight and obesity were associated with increased risk among males. For females, diabetes risk increased for less than tertiary education, obesity, being a former smoker, and having had hypertension. However, higher age, moderate drinking, and having had high HDL decreased the risk of diabetes for females.

Despite most factors not being significantly associated with outcomes in the current analysis, we included all the covariates in the tool because risk assessment in practice is a key objective for the development of DemNCD tool. The approach aimed to provide comprehensive information of all the practical risk/protective factors to support clinical advice on risk reduction or enhancing protection. The points allocated to individual risk factors for the DemNCD tool associated with the regression coefficients are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Points for DemNCD risk tools associated with dementia, stroke, MI, and diabetes following Fine and Gray sub distribution hazards model

| Covariates | Dementia | Stroke | MI | Diabetes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Age | ||||||||

| 65–69 | − 8 | − 9 | − 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 |

| 70–74 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 75–79 | 11 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | − 5 |

| 80–84 | 15 | 14 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | − 8 | − 9 |

| 85–89 | 25 | 24 | − 5 | 0 | − 2 | 0 | − 7 | − 21 |

| 90 + | 49 | 32 | − 6 | − 15 | 9 | − 2 | * | * |

| Education | ||||||||

| Less than secondary | 7 | 3 | − 1 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 10 |

| Upper secondary | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | − 2 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Tertiary | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Obesity | ||||||||

| Underweight | 11 | 2 | − 1 | − 6 | 12 | − 1 | * | − 10 |

| Normal weight | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Overweight | 0 | − 3 | 2 | − 2 | 5 | 3 | 12 | 4 |

| Obese | − 1 | − 6 | 1 | − 4 | 4 | 4 | 20 | 18 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Moderate | − 5 | − 6 | 2 | − 1 | 2 | 0 | − 4 | − 6 |

| High | − 1 | − 9 | 3 | − 3 | 0 | 9 | − 1 | − 13 |

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Non-smoker | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Current smoker | − 3 | − 2 | − 1 | − 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Former smoker | 0 | 4 | − 3 | 3 | − 2 | − 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Hypertension (yes) | 0 | − 1 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| Cholesterol (high) | 4 | 5 | 6 | − 2 | − 3 | 1 | 6 | − 5 |

| High HDL | 3 | − 3 | − 4 | − 3 | − 1 | − 2 | − 4 | − 6 |

| High LDL | 2 | − 5 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 1 | − 8 | − 3 |

| Depression (yes) | − 2 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 5 | − 1 | − 1 | 3 |

| Fish serve | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | − 1 | − 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Fruits and vegetable | 0 | − 4 | − 6 | − 4 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| TBI (yes) | 0 | − 1 | 2 | 6 | 1 | − 6 | 0 | 4 |

| Loneliness (yes) | 4 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | − 2 | 3 |

| Physical activity | 6 | 2 | 0 | − 1 | 1 | 2 | − 2 | − 1 |

| Cognitive activity | Not included | Not included | Not included | |||||

| Low | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Moderate | 1 | − 1 | ||||||

| High | − 13 | − 8 | ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Sleep problem | 0 | − 5 | 5 | − 2 | 10 | 3 | 3 | − 2 |

| Hearing loss | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | − 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Diabetes | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 6 | Not included | |

| Stroke | 13 | 8 | Not included | 3 | 7 | Not included | ||

| MI | − 4 | − 2 | 3 | 4 | Not included | Not included | ||

Validation of the DemNCD risk tools

Table 4 reports the Harrel C statistics of the DemNCD tool for predicting dementia, stroke, MI, and diabetes in the validation sample. The overall C-statistics (95% CI) for predicting dementia were 0·68 (0·65, 0·70) for males and 0·65 (0·63, 0·67) for females in the combined validation sample. On validating the model against each cohort separately, all the cohorts exhibited good prediction properties except for MAAS and FHS. This was because MAAS has only two female and four male dementia cases in the validation sample. In general, cohorts with longer exposure times, such as ARIC, CFAS I, CFAS II, and CHS, demonstrated better performance compared to other cohorts. The resulting wide confidence interval in the SLAS I dataset suggests significant population heterogeneity. Overall, prediction for dementia was better for females than males in all the validation cohorts except for FHS, MAAS, and MAS. CFAS II had the highest C-statistics for predicting dementia for females, where Harrel C (95% CI) was 0·75 (0·68, 0·82), whereas ARIC had the highest C-statistics for males (C-statistics, 0·72 95% CI 0·68, 0·76).

Table 4.

Predictive accuracy of the DemNCD tool following Fine and Gray model [Harrel’ C (95% CI)] associated with the diagnosis of dementia, stroke, MI, and diabetes

| Dementia | Stroke | MI | Diabetes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Validation data | n | Harrel’ C | 95% CI | n | Harrel’ C | 95% CI | n | Harrel’ C | 95% CI | n | Harrel’ C | 95% CI | |

| Combined data | Male | 4862 | 0·68 | (0·65, 0·70) | 5073 | 0·58 | (0·54,0·61) | 4631 | 0·65 | (0·61, 0·68) | 4607 | 0·68 | (0·64,0·72) |

| Female | 6924 | 0·65 | (0·63, 0·67) | 7323 | 0·55 | (0·52, 0·57) | 7205 | 0·65 | (0·62, 0·68) | 6807 | 0·61 | (0·57, 0·65) | |

| Data components | |||||||||||||

| ARIC | Male | 801 | 0·72 | (0·68, 0·76) | 761 | 0·63 | (0·55, 0·70) | 665 | 0·59 | (0·52, 0·67) | 536 | 0·61 | (0·54, 0·68 |

| Female | 1104 | 0·74 | (0·71, 0·78) | 1043 | 0·60 | (0·54, 0·66) | 990 | 0·68 | (0·62, 0·73) | 771 | 0·59 | (0·51, 0·67) | |

| CFAS I | Male | 1707 | 0·67 | (0·62, 0·72) | 1606 | 0·56 | (0·49, 0·63) | 1495 | 0·49 | (0·39, 0·59) | 1645 | 0·64 | (0·56, 0·72) |

| Female | 2550 | 0·68 | (0·64, 0·71) | 2473 | 0·60 | (0·53, 0·67) | 2447 | 0·63 | (0·52, 0·74) | 2489 | 0·55 | (0·47, 0·64) | |

| CFAS II | Male | 1048 | 0·64 | (0·53, 0·75) | 971 | 0·50 | (0·34, 0·67) | 887 | 0·53 | (0·12, 0·95) | 885 | 0·65 | (0·54, 0·76) |

| Female | 1175 | 0·75 | (0·68, 0·82) | 1129 | 0·75 | (0·61, 0·89) | 1156 | 0·59 | (0·45, 0·74) | 1077 | 0·53 | (0·40, 0·66) | |

| CHS | Male | 476 | 0·67 | (0·60, 0·74) | 828 | 0·58 | (0·53, 0·63) | 739 | 0·53 | (0·49, 0·58) | 669 | 0·65 | (0·57, 0·72) |

| Female | 704 | 0·70 | (0·65, 0·75) | 1156 | 0·58 | (0·54, 0·61) | 1106 | 0·56 | (0·52, 0·61) | 989 | 0·67 | (0·60, 0·73) | |

| FHS | Male | 190 | 0·60 | (0·52, 0·68) | 374 | 0·50 | (0·41, 0·59) | 269 | 0·54 | (0·44 0·64) | 318 | 0·56 | (0·40, 0·72) |

| Female | 290 | 0·43 | (0·37, 0·48) | 540 | 0·63 | (0·57, 0·68) | 435 | 0·48 | (0·39, 0.58) | 478 | 0·57 | (0·43, 0·71) | |

| ADAMS | Male | 77 | 0·65 | (0·52, 0·79) | 74 | 0·75 | (0·45, 1·00) | NA | 65 | 0·42 | (0·00, 0·87) | ||

| Female | 81 | 0·70 | (0·59, 0·82) | 78 | 0·59 | (0·26, 0·92) | 83 | 0·66 | (0·33, 0·99) | ||||

| MAAS | Male | 81 | 0·60 | (0·31, 0·89) | NA | 73 | 0·45 | (0·16, 0·73) | 76 | 0·54 | (0·26, 0·82) | ||

| Female | 79 | 0·45 | (0·32, 0·57) | N/A | 77 | 0·77 | (0·98, 0·96) | 67 | 0·77 | (0·64, 0·90) | |||

| MAP | Male | 170 | 0·69 | (0·60, 0·78) | 170 | 0·79 | (0·64, 0·94) | 155 | 0·64 | (0·47, 0·81) | 150 | 0·73 | (0·61, 0·86) |

| Female | 506 | 0·74 | (0·69, 0·79) | 480 | 0·58 | (0·47, 0·69) | 487 | 0·58 | (0·44, 0·72) | 476 | 0·64 | (0·55, 0·73) | |

| MAS | Male | 150 | 0·70 | (0·62, 0·79) | 142 | 0·59 | (0·41, 0·78) | 127 | 0·47 | (0·23, 0·72) | 128 | 0·39 | (0·26, 0·53) |

| Female | 184 | 0·63 | (0·55, 0·72) | 179 | 0·53 | (0·36, 0·69) | 169 | 0·49 | (0·24, 0·74) | 165 | 0·76 | (0·65, 0·87) | |

| SLAS I | Male | 162 | 0·72 | (0·59, 0·85) | 147 | 0·65 | (0·40, 0·91) | 151 | 0·49 | (0·30, 0·68) | 135 | 0·66 | (0·54, 0·78) |

| Female | 251 | 0·74 | (0·57, 0·91) | 245 | 0·59 | (0·30, 0·87) | 249 | 0·46 | (0·29, 0·63) | 212 | 0·48 | (0·24, 0·72) | |

Compared with dementia, the DemNCD resulted in similar C-statistics for MI and diabetes, however, was somewhat lower for stroke. The overall C-statistics (95% CI) for predicting stroke were similar for both males 0·58 (0·54, 0·61) and females 0·55 (0·52, 0·57) in the combined sample. All the cohort components of the validation sample provided similar C-statistics. For prediction of MI using the DemNCD tool, the overall C-statistics (95% CI) were also similar for males 0·65 (0·61, 0·68) and females 0·65 (0·62, 0·68) in the combined sample. For prediction of diabetes using the DemNCD tool, the overall C-statistics (95% CI) were 0·68 (0·64, 0.72) and 0·61 (0·57, 0·65) for males and females, respectively, in the combined sample. Among the individual cohorts in the validation sample, all the cohorts provided similar C-statistics, except for HRS-ADAMS and MAS for males’ sample. This was because low number of incident diabetes were available in the validation sample for these cohorts (two incident diabetes cases in males for both HRS-ADAMS and MAS).

Comparison of sensitivity, specificity, and cutoff points of DemNCD

Table 5 reports the quantile cut-offs, sub-distribution hazards ratios, sensitivity, and specificity for predicting dementia, stroke, MI, and diabetes. The final risk scores for predicting the four outcomes were similar for the model development and validation cohorts and sexes. The final score ranges from − 34 to 72 for dementia, − 24 to 32 for stroke, − 7 to 47 for MI, and − 42 to 45 for diabetes. Overall, the sub-distribution hazards (sHR) increased for higher quantile-cut-offs for DemNCD risk for all outcomes. The model and validation datasets provided similar sensitivity and specificity for a given cut-off.

Table 5.

Comparison of sensitivity and specificity for a given cut-off of DemNCD risk scores for predicting dementia

| Outcomes (DemNCD score range) | Percentile cutoff ( ≥) | Cut-off Score | Model data | Validation data | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sHR (95% CI) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | sHR | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |||

| For males | ||||||||

| Dementia (model data: −33, 72; validation data: −34, 44) | 16·6% | − 6 | 2·16 (1·45, 3·21) | 96·3 | 18·7 | 1·31 (0·82, 2·07) | 94·0 | 18·1 |

| 33·3% | 1 | 3·05 (2·08, 4·46) | 87·7 | 37·5 | 1·67 (1·09, 2·61) | 85·8 | 36·6 | |

| 50% | 8 | 4·59 (3·18, 6·63) | 75·6 | 55·1 | 2·97 (1·96, 4·48) | 74·0 | 55·0 | |

| 66·7% | 14 | 5·89 (4·11, 8·46) | 58·3 | 70·9 | 3·45 (2·32, 5·15) | 57·7 | 69·5 | |

| 83·3% | 21 | 10·43 (7·34, 14·81) | 36·1 | 86·2 | 5·74 (3·89, 8·47) | 33·5 | 86·1 | |

| Stroke (model data: −18, 32; validation: −16, 29) | 16·6% | − 1 | 0·99 (0·71, 1·37) | 86·0 | 21·8 | 1·12 (0·68, 1·84) | 88·7 | 21·7 |

| 33·3% | 1 | 1·09 (0·83, 1·44) | 77·0 | 35·0 | 1·74 (1·18, 2·57) | 80·3 | 34·0 | |

| 50% | 4 | 1·46 (1·09, 1·94) | 60·0 | 56·7 | 1·59 (1·03, 2·47) | 57·3 | 55·5 | |

| 66·7% | 6 | 2·06 (1·60, 1·52) | 46·6 | 69·6 | 1·57 (104, 2·37) | 44·7 | 67·8 | |

| 83·3% | 10 | 2·16 (1·66, 2·82) | 21·1 | 87·0 | 2·59 (1·76, 3·81) | 26·3 | 85·4 | |

| Myocardial infarction (model data: −7, 45; validation: −6, 47) | 16·6% | 4 | 1·83 (1·27, 2·64) | 93·3 | 20·3 | 1·84 (1·16, 2·90) | 92·7 | 20·8 |

| 33·3% | 7 | 3·39 (2·45, 4·67) | 84·0 | 35·2 | 3·19 (2·14, 4·77) | 82·4 | 35·1 | |

| 50% | 12 | 3·42 (2·46, 4·76) | 64·2 | 53·5 | 3·18 (2·11, 4·79) | 62·0 | 53·1 | |

| 66·7% | 16 | 3·89 (2·77, 5·48) | 46·9 | 71·1 | 2·28 (1·43, 3·63) | 42·9 | 70·9 | |

| 83·3% | 20 | 5·50 (3·99, 7·57) | 33·2 | 85·0 | 4·91 (3·38, 7·36) | 31·3 | 84·9 | |

| Diabetes (model data: −18, 37; validation: −20, 35) | 16·6% | − 2 | 1·84 (1·20, 2·83) | 91·9 | 18·4 | 1·01 (0·55, 1·84) | 90·8 | 18·6 |

| 33·3% | 3 | 1·52 (0·89, 2·60) | 75·9 | 41·8 | 1·73 (0·90, 3·33) | 79·7 | 42·0 | |

| 50% | 5 | 1·85 (1·19, 2·88) | 70·7 | 52·5 | 1·65 (0·94, 2·91) | 72·8 | 52·3 | |

| 66·7% | 8 | 3·41 (2·23, 5·21) | 57·9 | 71·4 | 2·80 (1·62, 4·82) | 59·0 | 71·7 | |

| 83·3% | 13 | 6·33 (4·28, 9·36) | 40·4 | 84·9 | 5·65 (3·45, 9·25) | 42·2 | 85·2 | |

| For females | ||||||||

| Dementia (model data: −36, 47; validation: −34, 44) | 16·6% | − 11 | 1·44 (1·13, 1·85) | 94·9 | 19·5 | 1·63 (1·16, 2·30) | 95·0 | 19·0 |

| 33·3% | − 4 | 1·80 (1·41, 2·29) | 85·6 | 38·6 | 2·13 (1·53, 2·98) | 84·5 | 38·4 | |

| 50% | 2 | 2·46 (1·95, 3·09) | 75·0 | 55·4 | 2·58 (1·87, 3·56) | 72·7 | 54·3 | |

| 66·7% | 9 | 3·56 (2·86, 4·44) | 59·2 | 71·1 | 3·71 (2·72, 5·07) | 55·7 | 70·6 | |

| 83·3% | 19 | 5·05 (4·05, 6·29) | 33·7 | 87·7 | 4·60 (3·37, 6·29) | 29·7 | 86·7 | |

| Stroke (model data: −24, 27; validation: −22, 29) | 16·6% | − 1 | 1·03 (0·83, 1·28) | 82·3 | 21·5 | 0·74 (0·54, 1·02) | 80·7 | 22·3 |

| 33·3% | 1 | 0·99 (0·81, 1·20) | 70·5 | 34·4 | 0·86 (0·66, 1·12) | 72·1 | 34·2 | |

| 50% | 4 | 0·87 (0·71, 1·10) | 52·8 | 54·6 | 0·77 (0·57, 1·03) | 53·5 | 54·8 | |

| 66·7% | 6 | 1·00 (0·82, 1·23) | 40·3 | 69·6 | 0·83 (0·63, 1·10) | 41·8 | 68·9 | |

| 83·3% | 9 | 1·56 (1·30, 1·88) | 24·2 | 85·8 | 1·41 (1·11, 1·81) | 26·8 | 85·0 | |

| Myocardial infarction (model data: −7, 43; validation: −7, 44) | 16·6% | 6 | 1·12 (0·84, 1·50) | 90·2 | 19·8 | 0·97 (0·67, 1·40) | 88·3 | 19·1 |

| 33·3% | 9 | 1·28 (0·93, 1·76) | 78·8 | 39·5 | 1·25 (0·85, 1·85) | 75·7 | 39·3 | |

| 50% | 11 | 1·67 (1·27, 2·20) | 71·1 | 52·1 | 1·12 (0·77, 1·64) | 65·7 | 52·4 | |

| 66·7% | 14 | 2·27 (1·75, 2·94) | 56·2 | 69·7 | 1·72 (1·22, 2·43) | 54·8 | 69·2 | |

| 83·3% | 19 | 4·77 (3·73, 6·10) | 36·1 | 87·5 | 3·14 (2·27, 4·33) | 34·3 | 86·4 | |

| Diabetes (model data: −42, 45; validation: −40, 45) | 16·6% | − 5 | 1·38 (0·95, 2·00) | 91·1 | 18·1 | 0·82 (0·50, 1·35) | 87·5 | 17·6 |

| 33·3% | 1 | 1·90 (1·31, 2·74) | 80·1 | 36·6 | 1·86 (1·20, 2·90) | 78·1 | 36·6 | |

| 50% | 5 | 1·79 (1·25, 2·57) | 68·1 | 51·2 | 1·11 (0·69, 1·77) | 62·6 | 50·7 | |

| 66·7% | 9 | 2·62 (1·87 3·66) | 55·1 | 68·2 | 1·37 (0·88, 2·14) | 51·4 | 67·7 | |

| 83·3% | 15 | 6·05 (4·41, 8·29) | 34·7 | 86·3 | 3·68 (2·47, 5·47) | 31·6 | 86·1 | |

sHR, sub distribution hazards

Sensitivity analysis: DemNCD risk tool development and validation using logistic regression (DemNCD-LR)

Additional file 1: Table S4 reports the combined regression coefficients estimated by meta-analysis of logistic regression model parameters for dementia, stroke, MI, and diabetes for both males and females. In general, the regression coefficients from logistic regression models were comparable to the regression coefficients of Fine and Gray sub-distribution models. The corresponding points for the DemNCD-LR tools are given in Additional file 1: Table S5.

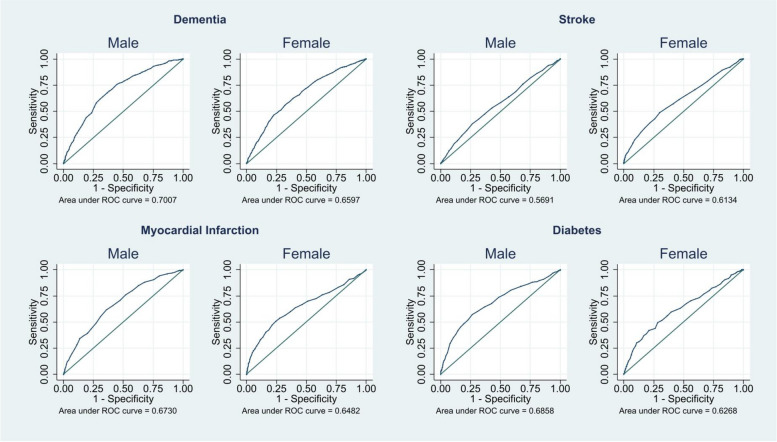

Figure 1 and Additional file 1: Table S6 show the predictive accuracy of the DemNCD-LR risk tools. We obtained very similar predictive accuracy in the DemNCD-LR for males and females for all four outcomes. The AUC (95% CI) for dementia were 0·70 (0·68, 0·72) and 0·66 (0·64, 0·68), for stroke 0·57 (0·54, 0·60) and 0.61 (0·59, 0·64), for MI 0·67 (0·65, 0·70) and 0·65 (0·62, 0·68), and for diabetes 0·69 (0·65, 0·72) and 0·63 (0·59, 0·66) for males and females, respectively. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit (Additional file 1: Table S7) and the calibration plots (Additional file 1: Figs. S2-S5) show that the DemNCD-LR provides systematic overestimation of risks in males, but relatively poor calibration for stroke, MI, and diabetes in females.

Fig. 1.

AUC of the DemNCD-LR tool following logistic regression associated with the diagnosis of dementia, MI, stroke, and diabetes

Finally, Additional file 1: Table S8 reports sensitivity, specificity, and OR corresponding to the quantiles cut-offs for DemNCD-LR risk scores for males and females. Similar to the DemNCD risk tools, the final risk scores for predicting the four outcomes were similar for the model development and validation cohorts.

Comparison of the full DemNCD/DemNCD-LR versus age only model

We also examined whether the DemNCD/DemNCD-LR models with all the risk/protective factors provided better predictive ability compared with the age only model, as previous dementia risk tools suggest that an age alone model for dementia provides similar predictive ability as a full model [9]. Similar to the previous tools, the age only model provided similar C-statistics as the full model (see Additional file 1: Table S9). However, for other outcomes, adding risk factors to age improved the predictive ability.

Discussion

To our knowledge, DemNCD is the first attempt to develop a risk tool based on a common set of predictors for dementia, stroke, MI, and diabetes that is suitable for use in routine clinical practice. The DemNCD focuses on relatively short term prediction and hence can be used as an educational and motivational tool as well as to target the interventions for those most at risk. Our results demonstrate that the proposed risk tools (DemNCD/DemNCD-LR) provide good prediction properties for dementia, MI, diabetes, and strokes especially for older adults aged 65 and above. For estimating dementia risk, comparable C-statistics were obtained using DemNCD and DemNCD-LR, as are found with existing risk tools for dementia (CogDrisk, ANU-ADRI, CAIDE, and LIBRA [9, 11]). For predicting stroke, we obtained lower C-statistics compared to dementia prediction, but comparable C-statistics estimate was obtained to those of existing risk scores such as the Framingham stroke risk score [12], the Stroke Riskometer [13], and the Qstroke for older adults [58]. In addition, similar C-statistics for predicting stroke and cardiovascular disease among older adults have been reported elsewhere [58–60].

For estimating risk of MI, our DemNCD/DemNCD-LR risk tools provide comparable AUC (95% CI) estimates to the TMTI (AUC ranges from 0·65 to 0·68) [15], the INHEART (AUC (95% CI) for men > 55 years and female > 65 years is 0·67 (0·65, 0·69)) [17], and the Essen risk score (AUC 0·64 95% CI (0·57–0·71) [16]. However, there are key differences in underlying population characteristics where the above risk tools were employed. The TMTI was developed and validated among patients who were using aspirin, and the Essen risk score was based on a population with cardiovascular risk. The INHEART risk score is the only risk score validated using data with non-laboratory-based risk factors similar to ours [17]. Note that while cardiovascular risk tools generally yield c-statistics closer to 0.7–0.8 [14, 61] when applied to samples of adults of all ages, analyses specifically focused on older adults typically result in c-statistics ranging from 0.58 to 0.65 [58, 60, 62, 63]. A recent report found that the relative risk associated with various cardiovascular risk factors including obesity, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, smoking, and physical inactivity decreases with increasing age, providing lower C-statistics for MI and stroke among older adults compared with all age groups [58, 60] including early life, midlife, and late-life. In general, while the literature has documented the weak performance of various risk assessment tools among older adults, these findings have not been widely recognized.

For diabetes, we observed somewhat lower C-statistics/AUC (95% CI) estimates compared to existing diabetes risk scores [18] where AUC for the risk models involving self-reported variables generally ranged between 0.7 and 0.8. This might be due to our use of late-life cohorts in developing and validating diabetes risk. Most prior diabetes risk tools were developed using mid-life to early late-life cohorts [18].

We observed a paradoxical association between risk factors including obesity, alcohol consumption, high HDL and hypertension with dementia, diabetes, and stroke especially for older women. Similar results are also reported eslewhere [64–68] for older adults. Older adults undergo substantial physical changes leading twowards disability and frailty. Thus, the relationship between these risk factors assessed in midlife may not be relevant to later life risk.

Although we aimed to show that our proposed DemNCD risk tools are comparable with the existing risk tools, we acknowledge that the proper comparison of the various risk tools would need to be conducted within a single dataset using same methodology, which is beyond the scope of present paper. While model selection can narrow the set of risk factors and may improve prediction, such analysis is beyond the scope of this paper because of heterogeneity of our cohorts. Such an approach can be tested in future research.

Our study had strengths and limitations. The large number of cohorts with standardized measures provides a large set of covariates, which may not be possible with a single cohort where some covariates are entirely missing. Multi-country cohort data in the development and validation of the risk tools enhances the generalisability of the DemNCD risk tool to a wide range of populations. However, the cohorts were heterogeneous in terms of sample size, length of follow-up and age of recruitment, and outcome measures. We opted to conduct meta-analyses of regression coefficients from individual cohorts to avoid the effect of cohorts with large sample sizes on the final estimated regression coefficients. We were unable to estimate the baseline risk of the outcomes or provide the 5- or 10-year risk score for each of the individual outcomes because of because we used meta analysis of regression coefficients from individual cohorts. Moreover, different diagnostic methods for dementia, stroke, MI, and diabetes across cohorts may cause potential biases. To assess the impact of this and other cohort specific biases, we studied the cohort-specific prediction in addition to aggregate predictions for all cohorts. Yet, the use of heterogeneous datasets for calculating risk scores is increasing in the literature (e.g., PREVENT [69], the American Heart Association’s new cardiovascular disease risk tool) due to the benefit of having large contemporary sample that may produce more accurate risk score for diverse groups of the population.

The performance of DemNCD risk tool is very similar to an age only model. This is because all modifiable dementia risk factors increases with age and accumulate over time. Older age often serves as an indicator of time and risk exposure, functioning as a proxy measure for underlying cumulative exposure of life time risk factors. As a result, age is the most significant predictor of dementia, the performance of an age only model in dementia risk assessment is very similar to various risk models that included age and other risk factors [9, 70]. However, age itself is merely a measure of time and lacks biological or causal attributes. So, it does not fundamentally explain risk or its modification. The recent Lancet commission suggests that 14 dementia risk factors account for 45.3% of the population attributable risk of dementia [4]. Early identification of high-risk individuals could improve risk perceptions and help health professionals to recommend interventions that mitigate such risks.

In this paper, we considered a large number of risk/protective factors across all four conditions irrespective of their statistical significance in our data analysis. This may potentially cause low C-statistics. However, all of these risk/protective factors were considered based on the literature and expert panel judgment, existing risk tools, and current recommendations. Therefore, consideration of all of these risk/protective factors in community settings and in intervention studies may provide great scope in risk identification and behavioral changes to enhance risk reduction for dementia and other NCDs.

Conclusions

The novel DemNCD-Risk tool provides risk information for dementia and three other cadiometabolic conditions (stroke, MI, and diabetes), on the basis of a single assessment. It has been shown to provide efficient and reasonable predictive properties for all of these outcomes. The tool has the potential to be used in community and clinical settings, primary care and for policy development in preventive health.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Section S1 a brief description of the study datasets, Table S1 definition of outcome. Fig. S1. Flowchart showing the process of selecting predictors for the four outcomes, Table S2 distribution of covariates and outcome in each of the dataset under investigation. Table S3 definition of covariates used in the process of harmonization of covariates from different cohort dataset. Table S4 Regression coefficients (95% CI) obtained through meta-analysis following logistic regression model. Table S5 points for DemNCD-LR risk prediction tool. Table S6 validation results of DemNCD-LR risk prediction tool. Table S7 Hosmer Lemeshow goodness of fit for the DemNCD-LR in the validation dataset. Fig. S2. Calibration plot of observed against expected probabilities for assessment of DemNCD-LR performance for predicting dementia. Fig. S3. Calibration plot of observed against expected probabilities for assessment of DemNCD-LR performance for predicting stroke. Fig. S4. Calibration plot of observed against expected probabilities for assessment of DemNCD-LR performance for predicting MI. Fig. S5. Calibration plot of observed against expected probabilities for assessment of DemNCD-LR performance for predicting diabetes. Table S8 Comparison of sensitivity, specificity for a given cutoff of DemNCD-LR risk scores for males and females. Table S9 validation of DemNCD and DemNCD-LR risk tools with age only model in the combined sample.

Acknowledgements

The CHS was funded by contracts HHSN268201200036C, HHSN268200800007C, HHSN268201800001C, N01HC55222, N01HC85079, N01HC85080, N01HC85081, N01HC85082, N01HC85083, N01HC85086, 75N92021D00006, and grants U01HL080295 and U01HL130114 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Additional support was provided by R01AG023629 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions can be found at CHS-NHLBI.org. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of HealthThe HRS is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan. We would also thank the study participants and staff of the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Centre for providing MAP data. The Sydney Memory and Ageing Study was funded by three National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Program Grants (ID No. ID350833, ID568969, and APP1093083). The Cognitive Function and Ageing studies have been supported UK Medical Research Council (MRC; research grant G0601022, G9901400), National Health Service (NHS) and Alzheimer’s Society (ALZS-294). We thank all the participants across the world who contributed to these population based studies. We thank Professor Tze Pin Ng and Professor Roger Ho Chun Man for the SLAC dataset.

Abbreviations

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- LR

Logistic regression

- AUC

Area under the curve

- CI

Confidence Interval

- NCD

Non-communicable disease

- DemNCD

Dementia and other NCD

- ARIC

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

- CHS

Cardiovascular Health Study

- FHS

Framingham Heart Study

- CFAS

Cognitive function and Ageing Studies

- MAS

Sydney Memory and Aging Study

- MAAS

Maastricht Aging Study

- HRS ADAMS

Health and Retirement Study-Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study

- MAP

RUSH Memory and Aging project

- SLAS-I

Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study-I

- WHO

World Health Organization

- BMI

Body mass index

- AF

Atrial fibrillation

- TBI

Traumatic brain injury

- sHR

Sub-distribution hazards

Authors’ contributions

KJA is the lead investigator of this study and oversaw the project development, co-developed the original project idea; contributed towards developing the analysis plan, study design including identifying various cohort studies, applied to various studies and got approval, and planned the harmonisation of outcomes and predictors. HH contributed towards study design including identifying various cohort studies, planning the harmonisation of outcomes and predictors, conducted the analysis and drafted the paper. RP co-developed the original project idea; contributed towards developing the analysis plan, study design including identifying various cohort studies and planned the harmonisation of outcomes and predictors. SK contributed towards study design including identifying various cohort studies, applied to various studies, got approval, and planned the harmonisation of outcomes and predictors. KK contributed towards developing the analysis plan, study design including identifying various cohort studies, and planning the harmonisation of outcomes and predictors. CSA, MB, HB, PSS, MC, ALF, RW, MK, LJ, SK, NL, OL, FM, JES, provided inputs to the analysis. All authors critically reviewed and contributed to the manuscript and approved the final draft.

Funding

This research was funded by NHMRC GNT1171279 which supported SK and part funded HH. KJA and HH are funded by the Australian Research Council Fellowship FL190100011. JES is supported by NHMRC Investigator Grant APP1173952. CSA holds research grants and a Senior Investigator Fellowship from the NHMRC.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participants

Ethics approval is provided by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (UNSW HREC; protocol numbers HC200515, HC3413). All data are de-identified and stored on a secure server at Neuroscience Research Australia. All the participants consented to the original data collection and individual studies each received ethical/IRB approval.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JES has received honoraria for scientific advisory, lectures, and clinical research from Pfizer; Roche; Zuellig Pharma; Astra Zeneca; Sanofi; Novo Nordisk; MSD; Eli Lilly; Abbott; Mylan; Boehringer Ingelheim. CSA has received grants from Takeda.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia: WHO guidelines. 2019. [PubMed]

- 3.Tai XY, Veldsman M, Lyall DM, Littlejohns TJ, Langa KM, Husain M, et al. Cardiometabolic multimorbidity, genetic risk, and dementia: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022;3(6):e428–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Livingston G, Huntley J, Liu KY, Costafreda SG, Selbæk G, Alladi S, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the lancet standing Commission. Lancet. 2024;404:572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitmer RA, Sidney S, Selby J, Johnston SC, Yaffe K. Midlife cardiovascular risk factors and risk of dementia in late life. Neurology. 2005;64(2):277–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottesman RF, Albert MS, Alonso A, Coker LH, Coresh J, Davis SM, et al. Associations between midlife vascular risk factors and 25-year incident dementia in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(10):1246–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anstey KJ, Ee N, Eramudugolla R, Jagger C, Peters R. A systematic review of meta-analyses that evaluate risk factors for dementia to evaluate the quantity, quality, and global representativeness of evidence. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019;70(s1):S165–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anstey KJ, Peters R, Mortby ME, Kiely KM, Eramudugolla R, Cherbuin N, et al. Association of sex differences in dementia risk factors with sex differences in memory decline in a population-based cohort spanning 20–76 years. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):7710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huque MH, Kootar S, Eramudugolla R, Han SD, Carlson MC, Lopez OL, et al. CogDrisk, ANU-ADRI, CAIDE, and LIBRA risk scores for estimating dementia risk. JAMA Network Open. 2023;6:e2331460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anstey KJ, Zheng L, Peters R, Kootar S, Barbera M, Stephen R, et al. Dementia risk scores and their role in the implementation of risk reduction guidelines. Front Neurol. 2022;12:2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anstey KJ, Kootar S, Huque MH, Eramudugolla R, Peters R. Development of the CogDrisk tool to assess risk factors for dementia. Alzheimer’s Dementia: Diagn Assess Dis Monit. 2022;14(1): e12336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Agostino RB, Wolf PA, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Stroke risk profile: adjustment for antihypertensive medication. Framingham Study Stroke. 1994;25(1):40–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parmar P, Krishnamurthi R, Ikram MA, Hofman A, Mirza SS, Varakin Y, et al. The Stroke Riskometer™ app: validation of a data collection tool and stroke risk predictor. Int J Stroke. 2015;10(2):231–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Brindle P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study. bmj. 2017;357:j2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, McCabe CH, Horacek T, Papuchis G, et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non–ST elevation MI: a method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA. 2000;284(7):835–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boulanger M, Li L, Lyons S, Lovett NG, Kubiak MM, Silver L, et al. Essen risk score in prediction of myocardial infarction after transient ischemic attack or ischemic stroke without prior coronary artery disease. Stroke. 2019;50(12):3393–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGorrian C, Yusuf S, Islam S, Jung H, Rangarajan S, Avezum A, et al. Estimating modifiable coronary heart disease risk in multiple regions of the world: the INTERHEART Modifiable Risk Score. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(5):581–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noble D, Mathur R, Dent T, Meads C, Greenhalgh T. Risk models and scores for type 2 diabetes: systematic review. Bmj. 2011;343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Farnsworth von Cederwald B, Josefsson M, Wåhlin A, Nyberg L, Karalija N. Association of cardiovascular risk trajectory with cognitive decline and incident dementia. Neurology. 2022;98(20):e2013–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jia R, Wang Q, Huang H, Yang Y, Chung YF, Liang T. Cardiovascular disease risk models and dementia or cognitive decline: a systematic review. Front Aging Neuroscience. 2023;15:1257367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iturria-Medina Y, Sotero RC, Toussaint PJ, Mateos-Pérez JM, Evans AC. Early role of vascular dysregulation on late-onset Alzheimer’s disease based on multifactorial data-driven analysis. Nat Commun. 2016;7(1): 11934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Low L, Anstey K. Dementia literacy: recognition and beliefs on dementia of the Australian public. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2009;5(1):43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heger I, Deckers K, van Boxtel M, de Vugt M, Hajema K, Verhey F, et al. Dementia awareness and risk perception in middle-aged and older individuals: baseline results of the MijnBreincoach survey on the association between lifestyle and brain health. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025. 2017.

- 25.Chong TW, Rego T, Lai R, Westphal A, Pond CD, Curran E, et al. Preferences and perspectives of Australian general practitioners towards a new “four-in-one” risk assessment tool for preventative health: the LEAD! GP Project J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023;94(2):801–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kootar S, Huque MH, Kiely KM, Anderson CS, Jorm L, Kivipelto M, et al. Study protocol for development and validation of a single tool to assess risks of stroke, diabetes mellitus, myocardial infarction and dementia: DemNCD-Risk. BMJ Open. 2023;13(9): e076860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Investigators ARIC. The atherosclerosis risk in communit (ARIC) study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(4):687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, Furberg CD, Gardin JM, Kronmal RA, et al. The cardiovascular health study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1(3):263–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dawber TR, Meadors GF, Moore FE Jr. Epidemiological approaches to heart disease: the Framingham Study. American Journal of Public Health and the Nations Health. 1951;41(3):279–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brayne C, McCracken C, Matthews FE. Cohort profile: the Medical Research Council cognitive function and ageing study (CFAS). Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(5):1140–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthews FE, Arthur A, Barnes LE, Bond J, Jagger C, Robinson L, et al. A two-decade comparison of prevalence of dementia in individuals aged 65 years and older from three geographical areas of England: results of the Cognitive Function and Ageing Study I and II. The Lancet. 2013;382(9902):1405–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sachdev PS, Brodaty H, Reppermund S, Kochan NA, Trollor JN, Draper B, et al. The Sydney Memory and Ageing Study (MAS): methodology and baseline medical and neuropsychiatric characteristics of an elderly epidemiological non-demented cohort of Australians aged 70–90 years. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(8):1248–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schievink SH, van Boxtel MP, Deckers K, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Verhey FR, Köhler S. Cognitive changes in prevalent and incident cardiovascular disease: a 12-year follow-up in the Maastricht Aging Study (MAAS). Eur Heart J. 2022;43(7):e2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langa KM, Plassman BL, Wallace RB, Herzog AR, Heeringa SG, Ofstedal MB, et al. The aging, demographics, and memory study: study design and methods. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(4):181–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Mendes de Leon C, Bienias JL, Wilson RS. The rush memory and aging project: study design and baseline characteristics of the study cohort. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(4):163–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ng TP, Jin A, Feng L, Nyunt MSZ, Chow KY, Feng L, et al. Mortality of older persons living alone: Singapore longitudinal ageing studies. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bellou V, Belbasis L, Tzoulaki I, Evangelou E. Risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus: an exposure-wide umbrella review of meta-analyses. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3): e0194127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peters R, Booth A, Rockwood K, Peters J, D’Este C, Anstey KJ. Combining modifiable risk factors and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e022846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu J-T, Xu W, Tan C-C, Andrieu S, Suckling J, Evangelou E, et al. Evidence-based prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of 243 observational prospective studies and 153 randomised controlled trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(11):1201–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Psaltopoulou T, Sergentanis TN, Panagiotakos DB, Sergentanis IN, Kosti R, Scarmeas N. Mediterranean diet, stroke, cognitive impairment, and depression: a meta-analysis. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(4):580–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wahid A, Manek N, Nichols M, Kelly P, Foster C, Webster P, et al. Quantifying the association between physical activity and cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(9): e002495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang Y, Cai X, Li Y, Su L, Mai W, Wang S, et al. Prehypertension and the risk of stroke: a meta-analysis. Neurology. 2014;82(13):1153–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu Y, Hajifathalian K, Ezzati M, Woodward M, Rimm EB, Danaei G. Metabolic mediators of the effects of body-mass index, overweight, and obesity on coronary heart disease and stroke: a pooled analysis of 97 prospective cohorts with 1· 8 million participants. Lancet (London, England). 2013;383(9921):970–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anstey KJ, Cherbuin N, Herath PM. Development of a new method for assessing global risk of Alzheimer’s disease for use in population health approaches to prevention. Prev Sci. 2013;14(4):411–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deckers K, van Boxtel MP, Schiepers OJ, de Vugt M, Muñoz Sánchez JL, Anstey KJ, et al. Target risk factors for dementia prevention: a systematic review and Delphi consensus study on the evidence from observational studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(3):234–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kivipelto M, Ngandu T, Laatikainen T, Winblad B, Soininen H, Tuomilehto J. Risk score for the prediction of dementia risk in 20 years among middle aged people: a longitudinal, population-based study. The Lancet Neurology. 2006;5(9):735–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr, Larson MG, Massaro JM, Vasan RS. Predicting the 30-year risk of cardiovascular disease: the framingham heart study. Circulation. 2009;119(24):3078–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.D’Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):743–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilson PW, Meigs JB, Sullivan L, Fox CS, Nathan DM, D’Agostino RB. Prediction of incident diabetes mellitus in middle-aged adults: the Framingham Offspring Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(10):1068–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen L, Magliano DJ, Balkau B, Colagiuri S, Zimmet PZ, Tonkin AM, et al. AUSDRISK: an Australian Type 2 Diabetes Risk Assessment Tool based on demographic, lifestyle and simple anthropometric measures. Med J Aust. 2010;192(4):197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.von Hippel PT. How many imputations do you need? A two-stage calculation using a quadratic rule. Sociological Methods & Research. 2020;49(3):699–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huque MH, Carlin JB, Simpson JA, Lee KJ. A comparison of multiple imputation methods for missing data in longitudinal studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Austin PC, Lee DS, D’Agostino RB, Fine JP. Developing points-based risk-scoring systems in the presence of competing risks. Stat Med. 2016;35(22):4056–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harrell FE, Califf RM, Pryor DB, Lee KL, Rosati RA. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. JAMA. 1982;247(18):2543–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hosmer DW Jr. Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Livingstone S, Morales DR, Donnan PT, Payne K, Thompson AJ, Youn J-H, et al. Effect of competing mortality risks on predictive performance of the QRISK3 cardiovascular risk prediction tool in older people and those with comorbidity: external validation population cohort study. The lancet Healthy longevity. 2021;2(6):e352–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Os HJ, Kanning JP, Ferrari MD, Bonten TN, Kist JM, Vos HMM, et al. Added predictive value of female-specific factors and psychosocial factors for the risk of stroke in women under 50. Neurology. 2023;101(8):e805–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaneko H, Yano Y, Okada A, Itoh H, Suzuki Y, Yokota I, et al. Age-dependent association between modifiable risk factors and incident cardiovascular disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(2): e027684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pylypchuk R, Wells S, Kerr A, Poppe K, Riddell T, Harwood M, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk prediction equations in 400 000 primary care patients in New Zealand: a derivation and validation study. The Lancet. 2018;391(10133):1897–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Verweij L, Peters RJ, op Reimer WJS, Boekholdt SM, Luben RM, Wareham NJ, et al. Validation of the Systematic COronary Risk Evaluation-Older Persons (SCORE-OP) in the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. Int J Cardiol. 2019;293:226–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mehta S, Jackson R, Poppe K, Kerr AJ, Pylypchuk R, Wells S. How do cardiovascular risk prediction equations developed among 30–74 year olds perform in older age groups? A validation study in 125 000 people aged 75–89 years. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;74(6):527–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mielke MM, Zandi P, Sjogren M, Gustafson D, Ostling S, Steen B, et al. High total cholesterol levels in late life associated with a reduced risk of dementia. Neurology. 2005;64(10):1689–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sabia S, Fayosse A, Dumurgier J, Dugravot A, Akbaraly T, Britton A, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of dementia: 23 year follow-up of Whitehall II cohort study. bmj. 2018;362:k2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fitzpatrick AL, Kuller LH, Lopez OL, Diehr P, O’Meara ES, Longstreth W, et al. Midlife and late-life obesity and the risk of dementia: cardiovascular health study. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(3):336–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Odden MC, Rawlings AM, Arnold AM, Cushman M, Biggs ML, Psaty BM, et al. Patterns of cardiovascular risk factors in old age and survival and health status at 90. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 2020;75(11):2207–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rodgers JL, Jones J, Bolleddu SI, Vanthenapalli S, Rodgers LE, Shah K, et al. Cardiovascular risks associated with gender and aging. Journal of cardiovascular development and disease. 2019;6(2): 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khan SS, Coresh J, Pencina MJ, Ndumele CE, Rangaswami J, Chow SL, et al. Novel prediction equations for absolute risk assessment of total cardiovascular disease incorporating cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;148(24):1982–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kivimäki M, Livingston G, Singh-Manoux A, Mars N, Lindbohm JV, Pentti J, et al. Estimating dementia risk using multifactorial prediction models. JAMA Network Open. 2023;6(6):e2318132-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Section S1 a brief description of the study datasets, Table S1 definition of outcome. Fig. S1. Flowchart showing the process of selecting predictors for the four outcomes, Table S2 distribution of covariates and outcome in each of the dataset under investigation. Table S3 definition of covariates used in the process of harmonization of covariates from different cohort dataset. Table S4 Regression coefficients (95% CI) obtained through meta-analysis following logistic regression model. Table S5 points for DemNCD-LR risk prediction tool. Table S6 validation results of DemNCD-LR risk prediction tool. Table S7 Hosmer Lemeshow goodness of fit for the DemNCD-LR in the validation dataset. Fig. S2. Calibration plot of observed against expected probabilities for assessment of DemNCD-LR performance for predicting dementia. Fig. S3. Calibration plot of observed against expected probabilities for assessment of DemNCD-LR performance for predicting stroke. Fig. S4. Calibration plot of observed against expected probabilities for assessment of DemNCD-LR performance for predicting MI. Fig. S5. Calibration plot of observed against expected probabilities for assessment of DemNCD-LR performance for predicting diabetes. Table S8 Comparison of sensitivity, specificity for a given cutoff of DemNCD-LR risk scores for males and females. Table S9 validation of DemNCD and DemNCD-LR risk tools with age only model in the combined sample.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.